Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Sickle cell disease (SCD)-associated priapism is characterized by endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) dysfunction in the penis. However, the mechanism of decreased eNOS function/activation in the penis in association with SCD is not known.

AIMS

Our hypothesis in the present study was that eNOS is functionally inactivated in the SCD penis in association with impairments in eNOS posttranslational phosphorylation and the enzyme’s interactions with its regulatory proteins.

METHODS

Sickle cell transgenic (sickle) mice were used as an animal model of SCD. Wild type (WT) mice served as controls. Penes were excised at baseline for molecular studies. eNOS phosphorylation on Ser-1177 (positive regulatory site) and Thr-495 (negative regulatory site), total eNOS, and phosphorylated AKT (upstream mediator of eNOS phosphorylation on Ser-1177) expressions, and eNOS interactions with heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) and caveolin-1 were measured by Western blot. Constitutive NOS catalytic activity was measured by conversion of L-[14C]arginine-to-L-[14C]citrulline in the presence of calcium.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES

Molecular mechanisms of eNOS dysfunction in the sickle mouse penis.

RESULTS

eNOS phosphorylated on Ser-1177, an active portion of eNOS, was decreased in the sickle mouse penis compared to WT penis. eNOS interaction with its positive protein regulator HSP90, but not with its negative protein regulator caveolin-1, and phosphorylated AKT expression, as well as constitutive NOS activity, were also decreased in the sickle mouse penis compared to WT penis. eNOS phosphorylated on Thr-495, total eNOS, HSP90, and caveolin-1 protein expressions in the penis were not affected by SCD.

CONCLUSION

These findings provide a molecular basis for chronically reduced eNOS function in the penis by SCD, which involves decreased eNOS phosphorylation on Ser-1177 and decreased eNOS-HSP90 interaction.

Keywords: Priapism, eNOS phosphorylation, HSP90, caveolin-1

INTRODUCTION

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a hemoglobinopathy resulting from the expression of abnormal sickle hemoglobin (HbS). HbS arises from a single point mutation that substitutes amino acid valine for glutamic acid in the β-globin subunit of hemoglobin, leading to aggregation of sickle hemoglobin and red blood cell rigidity; abnormal red blood cells are associated with poor blood flow resulting in tissue hypoxia and ischemia.1 In addition to hemoglobinopathy and red blood cell sickling, SCD features an independent spectrum of vascular dysfunction, involving such abnormalities as defects in nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability, enhanced responses to vasoconstrictors, and elevated oxidative stress.2 The most common vasculopathies of SCD are pulmonary hypertension, priapism, and stroke.

Priapism is an erection disorder consisting of non-willful, excessive, and often recurrent penile erection unrelated to sexual excitement. It afflicts about 40% of men with SCD.3 Ischemic priapism, the most common form of priapism in which blood flow in the corpora cavernosa is absent, is frequently associated with irreversible penile tissue necrosis, as well as permanent and irreversible erectile dysfunction.4 Priapism has been shown to be associated with the overproduction of adenosine in the penis and activation of A2B receptor.5, 6 Furthermore, recent scientific investigation in animals has demonstrated that priapism arises from chronically impaired NO bioavailability due to a defect in the NO/cGMP/phosphodiesterase (PDE)5 signaling pathway in the penis.7, 8 Calcium-dependent NO synthase (NOS) activity and cGMP production are basally downregulated in the penis of endothelial NOS (eNOS) knockout mice, combined eNOS and neuronal NOS knockout mice, and sickle cell transgenic (sickle) mice, which downregulates PDE5 in the penis of these mice.7 Upon neuronally stimulated penile erection, priapism occurs due to uncontrolled cGMP-dependent vasodilation of the corpora cavernosa resulting from downregulated PDE5.7, 9, 10 These findings point to the critical role of eNOS dysfunction in the penis as a major molecular disturbance associated with priapism. However, the mechanism of decreased eNOS function or activation in the penis in association with SCD is not known.

AIMS

Our hypothesis in the present study was that eNOS is functionally inactivated in the SCD penis in association with SCD. Correlatively, we hypothesized that eNOS activation mechanisms are impaired by posttranslational modifications of the enzyme, such as its phosphorylation and its interactions with regulatory proteins, heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) and caveolin-1. For this investigation, we used the sickle transgenic mouse as an animal model of SCD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mouse model of human sickle cell disease

Transgenic sickle mice with knockout of all mouse hemoglobin genes and expressing exclusively human sickle hemoglobin (HbS) were developed at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.11 An in-house breeding colony, which mated sickle male mice to hemizygous females, generated animals for this study. Genotyping was performed by Transnetyx, Inc. (Cordova, TN). These mice exhibit priapism, as demonstrated by the exaggerated erectile response both pre- and post- electrical stimulation of the cavernous nerve compared with wild type (WT) mice.12, 13 Aged-matched WT C57BL/6 males were used as controls because this represents the predominant background strain for the transgenic mice. Male mice were 7–9 months old. Mice were pathogen free and received routine NIH rodent chow and water. Flaccid penes were collected before WT (n=13) and sickle (n=13) mice were sacrificed. All animal procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Western blot analysis

Penile tissue was homogenized as described.14 NOS was partially purified by affinity binding to 2′,5′-ADP Sepharose, an NADP structural analog immobilized on Sepharose 4B, which binds and immobilizes enzymes requiring this cofactor.14 Partially purified NOS samples were resolved on 4–20% Tris gels and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Membranes with partially purified NOS were probed with anti-phospho (P)-eNOS (Ser-1177 and Thr-495) antibodies (polyclonal rabbit, Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA) at 1:450 dilution (for P-eNOS analyses), anti-caveolin-1 antibody (polyclonal rabbit, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) at 1:1,000 dilution (for caveolin-1 bound to eNOS analysis), or anti-HSP90 antibody (monoclonal mouse, BD Transduction Laboratories, San Diego, CA) at 1:6,000 dilution (for HSP90 bound to eNOS analysis).15–17 After probing for P-eNOS, caveolin-1, or HSP90, these membranes were stripped and probed with anti-eNOS antibody (monoclonal mouse, BD Transduction Laboratories) at 1:1,000 dilution. P-eNOS, caveolin-1, and HSP90 densities were normalized relative to those of eNOS in partially purified samples. For Western blot analysis of P-AKT (Ser-473, polyclonal rabbit antibody, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:1,000 dilution), total caveolin-1 (1:7,000 dilution), total eNOS (1:1,000 dilution), and total HSP90 (1:2,000 dilution), a separate set of homogenates (20–70 μg) was used without purification and standardized to AKT (polyclonal rabbit antibody, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:1,000 dilution), or β-actin (monoclonal mouse antibody, Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO, 1:7,000 dilution). The ratio was determined in terms of arbitrary units and expressed relative to the ratio for WT mice. To verify that β-actin expression was not affected by SCD, the density of a set of samples was standardized per total proteins (Ponceau S staining). Ratios did not differ from the ones obtained using β-actin for standardization (data not shown). Band densities were quantified using NIH Image 1.29.

Constitutive NOS Enzyme Assay

Penile constitutive NOS catalytic activity was assayed by L-[14C]arginine-to-L-[14C]citrulline conversion in the presence of calcium.18 Enzyme activity was expressed as L-citrulline production in counts/min.

Statistical evaluation

Statistical analysis was performed by using the t-test for testing hypotheses for significant differences in mean values between groups. The data were expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). A value of P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

P-eNOS (Ser-1177 and Thr-495) and eNOS expressions in the penis of sickle mice

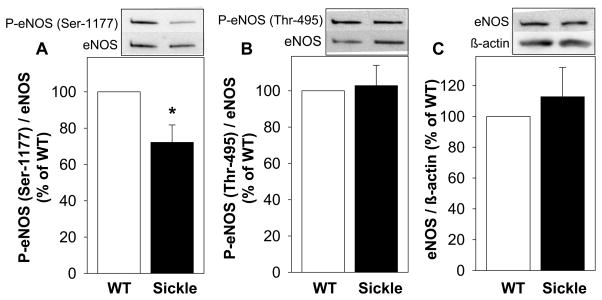

Because eNOS phosphorylated at Ser-1177 is the main activated form of the enzyme, we assessed the amount of P-eNOS (Ser-1177) in the penis of sickle mice. The sickle mouse penis exhibited significantly (P<0.05) reduced expression of P-eNOS (Ser-1177) compared to that of WT mice (Figure 1A). In contrast to eNOS phosphorylation on Ser-1177, phosphorylation of eNOS on Thr-495, which decreases the enzyme’s activity, was not affected by SCD (Figure 1B). Total eNOS protein expression in the penis of sickle mice did not differ from that of WT mice (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Effect of SCD on P-eNOS (Ser-1177) (A), P-eNOS (Thr-495) (B) and total eNOS (C) expressions in the penis of WT and sickle mice at baseline. Upper panels are representative Western immunoblots. Lower panels represent quantitative analyses of P-eNOS (Ser-1177), P-eNOS (Thr-495), and total eNOS in penes of WT and sickle mice. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM. *, P < 0.05. n= 6–8

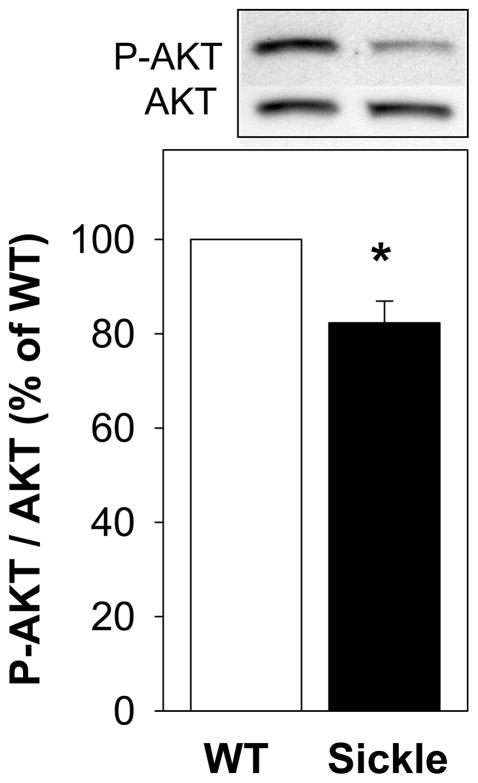

P-AKT in the penis of sickle mice

P-AKT, an upstream mediator of eNOS phosphorylation on Ser-1177, was significantly (P<0.05) reduced in the penis of sickle mice compared to the WT mouse penis (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Effect of SCD on P-AKT in the penis of WT and sickle mice at baseline. Upper panel is a representative Western immunoblot, and lower panel represents a quantitative analysis of P-AKT in penes of WT and sickle mice. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM. *, P < 0.05. n=8

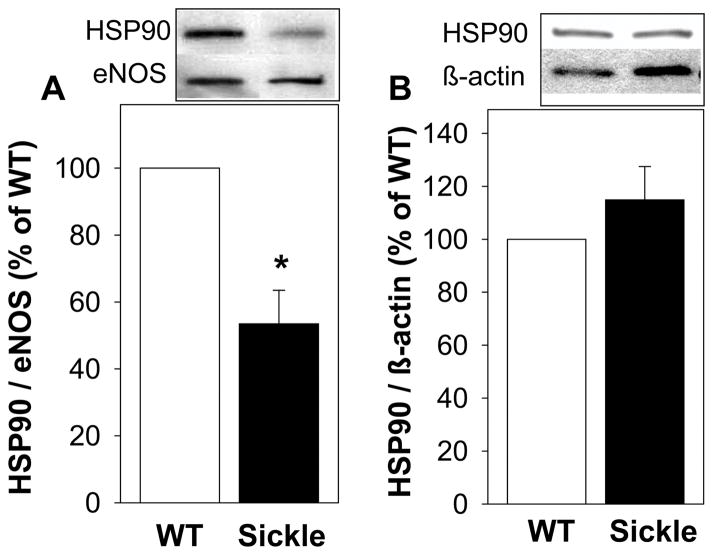

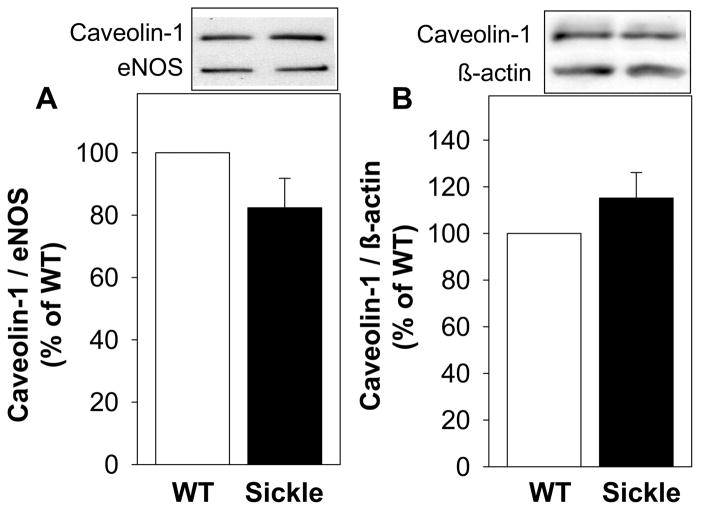

eNOS bindings to HSP90 and caveolin-1 in the penis of sickle mice

eNOS phosphorylation on Ser-1177 and eNOS activity are in large part determined by eNOS interaction with its main positive regulatory protein HSP90 and negative regulatory protein caveolin-1. Bindings of eNOS to HSP90 and caveolin-1 were evaluated in the penile samples partially purified for NOSs, thus allowing the detection of eNOS and proteins bound to eNOS using specific antibodies.15–17 While coimmunoprecipitation of eNOS and HSP90 would further support their interactions in the penis, these types of experiments in tissues are technically difficult, in contrast to using isolated endothelial cells. Figure 3A shows that the ratio of HSP90/eNOS was significantly (P<0.05) decreased in the penis of sickle mice compared to that of WT mice, implying decreased eNOS interaction with HSP90. These changes were unrelated to HSP90 expression, which was not different in the penis of sickle mice compared to that of WT mice (Figure 3B). eNOS binding to its negative regulator caveolin-1 (Figure 4A), as well as the protein expression of caveolin-1 (Figure 4B) in the penis of sickle mice, did not differ from values in WT mice.

Figure 3.

Effect of SCD on HSP90 binding to eNOS (A) and total HSP90 protein expression (B) in the penis of WT and sickle mice at baseline. Upper panels are representative Western blots, and lower panels represent quantitative analyses of HSP90/eNOS (indicative of HSP90 binding to eNOS) and HSP90 protein expression in penes of WT and sickle mice. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM. *, P < 0.05. n=5

Figure 4.

Effect of SCD on caveolin-1 binding to eNOS (A) and total caveolin-1 protein expression (B) in the penis of WT and sickle mice at baseline. Upper panels are representative Western blots, and lower panels represent quantitative analyses of caveolin-1/eNOS (indicative of caveolin-1 binding to eNOS) and caveolin-1 protein expression in penes of WT and sickle mice. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM. n=5–8

Constitutive NOS activity in the penis of sickle mice

Conversion of L-arginine to L-citrulline in the presence of calcium, a direct measure of constitutive (eNOS and neuronal NOS) catalytic activity, was decreased in penes from sickle mice (1463.8 ± 227.3 counts/min; n=5) compared to WT mouse penis (3885.2 ± 528.2 counts/min; n=5) at baseline.

DISCUSSION

The results of the present study demonstrate that altered eNOS regulatory mechanisms occur in the SCD penis, affirming that this condition features functionally inactivated eNOS. Here we show a decrease in eNOS phosphorylation on Ser-1177, an active portion of eNOS, in the SCD mouse penis. This effect was apparently due to decreased eNOS interaction with its positive protein regulator HSP90 (but not increased interaction with caveolin-1), which decreases AKT activation and AKT-mediated eNOS phosphorylation on Ser-1177, and reduces constitutive NOS activity. These findings provide a molecular basis for chronically reduced NO bioavailability in the penis by SCD, which conceivably results in priapism upon neuronally stimulated penile erection.8 These data also identify a new molecular target potentially for pharmacologic therapies for SCD, although more mechanistic studies will be required to demonstrate how eNOS/HSP90 interaction can be regulated or adjusted.

eNOS catalyzes the synthesis of NO, a potent vasodilator and a key mediator of penile erection and vascular homeostasis.19 The bioavailability of endothelial NO is largely regulated by posttranslational regulation of eNOS, such as binding of calcium-calmodulin, phosphorylation, protein interaction, dimer stabilization, and localization.20 While activation of eNOS with calcium/calmodulin is essential to the first step of the catalytic process of NO production, phosphorylation of eNOS at Ser-1177 is a key posttranslational modification that increases electron transfer at low intracellular calcium levels, which ensures the constitutive production of NO.20 Phosphorylation of eNOS at this site correlates directly with electron flow through the eNOS enzyme, increases in eNOS activity, and NO production.21 The decrease in eNOS phosphorylation on Ser-1177 in the penis of SCD mice, observed in this study, thus refers to a decrease in the active portion of the enzyme. This is evidenced by decreased calcium-dependent NOS activity in the SCD mouse penis, which conceivably reduces endothelial NO bioavailability and results in decreased basal blood flow and vascular dysfunction in the SCD mouse penis.

We conducted further studies to determine the mechanism of decreased eNOS phosphorylation on Ser-1177 in the penis of SCD mice. The transition from the early calcium-dependent to the phosphorylation-dependent activation of eNOS requires binding of eNOS to its main positive regulatory protein HSP90.22 HSP90 is associated with eNOS in the resting state, and upon stimulation of endothelial cells with agonists such as VEGF and shear stress, the association between the two proteins is increased, concomitant with enhanced NO production.23 The mechanism of eNOS activation upon HSP90 binding involves calmodulin-dependent disruption of eNOS binding with caveolin-1, recruitment of eNOS and AKT to adjacent regions on HSP90, reduced dephosphorylation of AKT, and increased ability of AKT to phosphorylate HSP90-bound eNOS.23–27 The direct protein interaction between eNOS and HSP90 also enhances eNOS coupled activity and prevents superoxide production by eNOS.28–30 Decreased eNOS-HSP90 interaction has been demonstrated in the lungs of sickle mice compared to WT mice.31 This effect has been attributed to increased oxidative stress generated by activated xanthine oxidase. We now show decreased binding of eNOS and HSP90 in the penis of SCD mice, which conceivably prevents AKT activation by phosphorylation and AKT-mediated eNOS phosphorylation on Ser-1177, and thus prevents eNOS activation. The decrease in HSP90 interaction with eNOS was not due to lower HSP90 or eNOS protein levels, which were not affected by SCD. Further studies are needed to determine the mechanism underlying the decreased interaction between HSP90 and eNOS in the SCD mouse penis. In addition to oxidative stress which may decrease eNOS-HSP90 interaction, the carboxyl terminus of HSP70-interacting protein (CHIP) has been shown to inactivate eNOS by uncoupling its interaction with HSP90 and by displacement of eNOS from the Golgi apparatus, which is otherwise required for trafficking of eNOS to the plasmalemma and subsequent activation.32 Furthermore, the function of HSP90 may be affected by its interaction with stimulatory and inhibitory proteins, phosphorylation, acetylation, and S-nitrosylation, the latter affecting the HSP90 conformation and binding to eNOS.33, 34

In contrast to eNOS phosphorylation on Ser-1177 which activates eNOS, eNOS phosphorylation on Thr-495 reduces eNOS catalytic activity by interfering with binding of calcium/calmodulin to eNOS.35–37 Agonist-induced dephosphorylation of Thr-495, associated with increased eNOS activity, is mediated by Ser/Thr protein phosphatase 1 (PP1), Ser/Thr protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A), and calcineurin (PP2B). 25, 36, 38 In vitro studies demonstrated that the activity of calcineurin is increased by HSP90.39 In human umbilical vein endothelial cells HSP90 overexpression promotes its association with eNOS, AKT, and calcineurin, and stimulates not only eNOS (Ser-1177) phosphorylation, but also eNOS (Thr-495) dephosphorylation, which both activate eNOS.25 We found that SCD did not affect eNOS phosphorylation on Thr-495 in the mouse penis, implying that decreased eNOS interaction with HSP90 in the sickle mouse penis specifically affects Ser-1177 phosphorylation and not dephosphorylation of eNOS on Thr-495.

While HSP90 facilitates eNOS activation, caveolin-1 operates as a main negative regulator of eNOS.40 The majority of functional eNOS in quiescent endothelial cells is targeted to caveolae by cotranslational N-myristoylation and posttranslational palmitoylation.20 Caveolin-1, the resident membrane protein of caveolae, can directly interact with eNOS and inhibit its activity by occupying its calmodulin-binding site.41–43 Stimuli such as shear stress and estrogen induce calcium increase, and the calcium/calmodulin complex displaces eNOS from caveolin-1 and away from its tonic inhibition. eNOS translocation is associated with interaction with other proteins, such as calmodulin and HSP90, and eNOS activation.44 We recently showed that increased interaction between eNOS and caveolin-1 occurs in the hypercholesterolemic pig penis,16 which apparently prevented eNOS activation and contributed to endothelial dysfunction. The interaction between eNOS and HSP90 was unaffected in the pig penis (unpublished data), implying specifically that the eNOS-caveolin-1 interaction in the penis is decreased in association with hypercholesterolemia. The present study demonstrates that eNOS interaction with caveolin-1 in the SCD mouse penis was unaffected. Our findings imply that dysregulated eNOS interaction with HSP90 associated with decreased phosphorylation of eNOS on Ser-1177 and decreased constitutive NOS activity may be a major mechanism underlying basally reduced eNOS function in the SCD mouse penis. Further studies are needed to examine whether other eNOS regulatory mechanisms, such as increased oxidative stress, changes in phosphorylation on other sites on eNOS, phosphorylation mediated by kinases other than AKT, phosphatase action, or interaction of eNOS with other regulatory proteins, are contributory.

At first it seems counterintuitive that decreased basal eNOS function leads to priapism. Recent studies demonstrated that the priapic behavior can be explained by chronically reduced endothelial NO bioavailability, resulting in PDE5 downregulation. As a result of PDE5 downregulation, cGMP accumulates in the penis after an episode of neurostimulation or nocturnal erection, producing unrestrained erectile tissue relaxation.7–10, 45

In addition to impaired endothelial NO signaling, as shown in this study, RhoA/ROCK-mediated vasoconstriction is decreased in penes of SCD mice, contributing to increased vasorelaxation.13

CONCLUSION

We observed altered eNOS phosphorylation on Ser-1177, a posttranslational modification of the enzyme which is a key regulator of its activity, in the SCD mouse penis. The underlying mechanism involves decreased eNOS interaction with its positive protein regulator HSP90, which decreases AKT activation and AKT-mediated eNOS phosphorylation on this site, decreasing constitutive NOS catalytic activity.

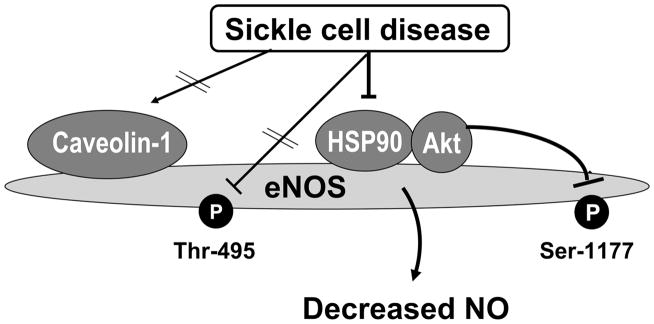

Figure 5.

Model for altered eNOS regulatory mechanisms in the SCD mouse penis. eNOS phosphorylation on Ser-1177, an active portion of eNOS, is decreased in the SCD mouse penis. This effect is due to decreased eNOS interaction with its positive protein regulator HSP90 (but not increased interaction with caveolin-1), which decreases AKT activation and AKT-mediated eNOS phosphorylation on Ser-1177, and reduces constitutive NOS activity. Decreased eNOS interaction with HSP90 in the sickle mouse penis does not affect dephosphorylation of eNOS on Thr-495.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: This work was supported by NIH/NIDDK grant RO1DK067223 to ALB

References

- 1.Kato GJ, Hebbel RP, Steinberg MH, Gladwin MT. Vasculopathy in sickle cell disease: Biology, pathophysiology, genetics, translational medicine, and new research directions. Am J Hematol. 2009;84:618–625. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wood KC, Granger DN. Sickle cell disease: role of reactive oxygen and nitrogen metabolites. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2007;34:926–932. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2007.04639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Montague DK, Jarow J, Broderick GA, Dmochowski RR, Heaton JP, Lue TF, Nehra A, Sharlip ID Members of the Erectile Dysfunction Guideline Update Panel, Americal Urological Association. American Urological Association Guideline on the management of priapism. J Urol. 2003;170:1318–1324. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000087608.07371.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Broderick GA, Kadioglu A, Bivalacqua TJ, Ghanem H, Nehra A, Shamloul R. Priapism: pathogenesis, epidemiology, and management. J Sex Med. 2010;7:476–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mi T, Abbasi S, Zhang H, Uray K, Chunn JL, Xia LW, Molina JG, Weisbrodt NW, Kellems RE, Blackburn MR, Xia Y. Excess adenosine in murine penile erectile tissues contributes to priapism via A2B adenosine receptor signaling. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1491–1501. doi: 10.1172/JCI33467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wen J, Jiang X, Dai Y, Zhang Y, Tang Y, Sun H, Mi T, Phatarpekar PV, Kellems RE, Blackburn MR, Xia Y. Increased adenosine contributes to penile fibrosis, a dangerous feature of priapism, via A2B adenosine receptor signaling. FASEB J. 2010;24:740–749. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-144147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Champion HC, Bivalacqua TJ, Takimoto E, Kass DA, Burnett AL. Phosphodiesterase-5A dysregulation in penile erectile tissue is a mechanism of priapism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:1661–1666. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407183102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burnett AL, Bivalacqua TJ. Priapism: current principles and practice. Urol Clin North Am. 2007;34:631–642. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burnett AL, Bivalacqua TJ, Champion HC, Musicki B. Feasibility of the use of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors in a pharmacologic prevention program for recurrent priapism. J Sex Med. 2006;3:1077–1084. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burnett AL, Bivalacqua TJ, Champion HC, Musicki B. Long-term oral phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitor therapy alleviates recurrent priapism. Urology. 2006;67:1043–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pászty C, Brion CM, Manci E, Witkowska HE, Stevens ME, Mohandas N, Rubin EM. Transgenic knockout mice with exclusively human sickle hemoglobin and sickle cell disease. Science. 1997;278:876–878. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5339.876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bivalacqua TJ, Musicki B, Hsu LL, Gladwin MT, Burnett AL, Champion HC. Establishment of a transgenic sickle-cell mouse model to study the pathophysiology of priapism. J Sex Med. 2009;6:2494–2504. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01359.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bivalacqua TJ, Ross AE, Strong TD, Gebska MA, Musicki B, Champion HC, Burnett AL. Attenuated RhoA/Rho-kinase signaling in the penis of transgenic sickle cell mice. Urology. 2010 Jun 8; doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.02.050. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hurt KJ, Musicki B, Palese MA, Crone JC, Becker RE, Moriaruty Jl, Snyder SH, Burnett AL. Akt-dependent phosphorylation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase mediated penile erection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:4061–4066. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052712499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris MB, Bartoli M, Sood SG, Matts RL, Venema RC. Direct interaction of the cell division cycle 37 homolog inhibits endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity. Circ Res. 2006;98:335–341. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000203564.54250.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Musicki B, Liu T, Strong T, Jin L, Laughlin MH, Turk JR, Burnett AL. Low-fat diet and exercise preserve eNOS regulation and endothelial function in the penis of early atherosclerotic pigs: a molecular analysis. J Sex Med. 2008;5:552–561. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00731.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Musicki B, Liu T, Strong TD, Lagoda GA, Bivalacqua TJ, Burnett AL. Post-translational regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) by estrogens in the rat vagina. J Sex Med. 2010;7:1768–1777. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01750.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bivalacqua TJ, Burnett AL, Hellstrom WJ, Champion HC. Overexpression of arginase in the aged mouse penis impairs erectile function and decreases eNOS activity: influence of in vivo gene therapy of anti-arginase. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H1340–H1351. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00121.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Musicki B, Ross AE, Champion HC, Burnett AL, Bivalacqua TJ. Post-translational modification of constitutive nitric oxide synthase in the penis. J Androl. 2009;30:352–362. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.108.006999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dudzinski DM, Michel T. Life history of eNOS: Partners and pathways. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;75:247–260. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCabe TJ, Fulton D, Roman LJ, Sessa WC. Enhanced electron flux and reduced calmodulin dissociation may explain ‘calcium-independent’ eNOS activation by phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:6123–6128. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.9.6123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brouet A, Sonveaux P, Dessy C, Balligand JL, Feron O. Hsp90 ensures the transition from the early Ca2+-dependent to the late phosphorylation-dependent activation of the endothelial nitric-oxide synthase in vascular endothelial growth factor-exposed endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:32663–32669. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101371200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garcia-Cardena G, Fan R, Shah V, Sorrentino R, Cirino G, Papapetropoulos A, Sessa WC. Dynamic activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by Hsp90. Nature. 1998;392:821–824. doi: 10.1038/33934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fontana J, Fulton D, Chen Y, Fairchild TA, McCabe TJ, Fujita N, Tsuruo T, Sessa WC. Domain mapping studies reveal that the M domain of hsp90 serves as a molecular scaffold to regulate Akt-dependent phosphorylation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase and NO release. Circ Res. 2002;90:866–873. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000016837.26733.be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kupatt C, Dessy C, Hinkel R, Raake P, Daneau G, Bouzin C, Boekstegers P, Feron O. Heat shock protein 90 transfection reduces ischemia-reperfusion-induced myocardial dysfunction via reciprocal endothelial NO synthase serine 1177 phosphorylation and threonine 495 dephosphorylation. Atherioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:1435–41. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000134300.87476.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sato S, Fujita N, Tsuruo T. Modulation of Akt kinase activity by binding to Hsp90. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:10832–10837. doi: 10.1073/pnas.170276797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takahashi S, Mendelsohn ME. Synergistic activation of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase (eNOS) by HSP90 and Akt: calcium-independent eNOS activation involves formation of an HSP90-Akt-CaM-bound eNOS complex. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:30821–30827. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304471200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pritchard KA, Jr, Ackerman AW, Gross ER, Stepp DW, Shi Y, Fontana YT, Baker JE, Sessa WC. Heat shock protein 90 mediates the balance of nitric oxide and superoxide anion from endothelial nitric-oxide synthase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:17621–17624. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100084200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ou Z, Ou J, Ackerman AW, Oldham KT, Pritchard KA., Jr L-4F, an apolipoprotein A-1 mimetic, restores nitric oxide and superoxide anion balance in low-density lipoprotein-treated endothelial cells. Circulation. 2003;107:1520–1524. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000061949.17174.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ou J, Fontana JT, Ou Z, Jones DW, Ackerman AW, Oldham KT, Yu J, Sessa WC, Pritchard KA., Jr Heat shock protein 90 and tyrosine kinase regulate eNOS·NO generation but not·NO bioactivity. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H561–H569. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00736.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pritchard KA, Jr, Ou J, Ou Z, Shi Y, Franciosi JP, Signorino P, Kaul S, Ackland-Berglund C, Witte K, Holzhauer S, Mohandas N, Guice KS, Oldham KT, Hillery CA. Hypoxia-induced acute lung injury in murine models of sickle cell disease. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;286:L705–L714. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00288.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jiang J, Cyr D, Babbitt RW, Sessa WC, Patterson C. Chaperone-dependent regulation of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase intracellular trafficking by the co-chaperone/ubiquitin ligase CHIP. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:49332–49341. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304738200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Retzlaff M, Stahl M, Eberl HC, Lagleder S, Beck J, Kessler H, Buchner J. Hsp90 is regulated by a switch point in the C-terminal domain. EMBO Rep. 2009;10:1147–1153. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martinez-Ruiz A, Villanueva L, Gonzalez O, Lopez-Ferrer D, Higueras MA, Tarin C, Rodriguez-Crespo I, Vazquez J, Lamas S. S-nitrosylation of Hsp90 promotes the inhibition of its ATPase and endothelial nitric oxide synthase regulatory activities. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:8525–8530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407294102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harris MB, Ju H, Venema VJ, Liang H, Zou R, Michell BJ, Chen ZP, Kemp BE, Venema RC. Reciprocal phosphorylation and regulation of endothelial nitric oxide-synthase in response to bradykinin stimulation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:16587–16591. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100229200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Michell BJ, Chen Z, Tiganis T, Stapleton D, Katsis F, Power DA, Sim AT, Kemp BE. Coordinated control of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase phosphorylation by protein kinase C and cAMP-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:17625–17628. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100122200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fleming I, Fisslthaler B, Dimmeler S, Kemp BE, Busse R. Phosphorylation of Thr(495) regulates Ca(2+)/calmodulin-dependent endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity. Circ Res. 2001;88:E68–E75. doi: 10.1161/hh1101.092677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Greif DM, Kou R, Michel T. Site-specific dephosphorylation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by protein phosphatase 2A: evidence for crosstalk between phosphorylation sites. Biochemistry. 2002;41:15845–15853. doi: 10.1021/bi026732g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Someren JS, Faber LE, Klein JD, Tumlin JA. Heat shock proteins 70 and 90 increase calcineurin activity in vitro through calmodulin-dependent and independent mechanisms. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;260:619–625. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dessy C, Feron O, Balligand JL. The regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by caveolin: a paradigm validated in vivo and shared by the ‘endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor’. Pflugers Arch. 2010;459:817–827. doi: 10.1007/s00424-010-0815-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ju H, Zou R, Venema VJ, Venema RC. Direct interaction of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase and caveolin-1 inhibits synthase activity. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:18522–18525. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.30.18522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Feron O, Belhassen L, Kobzik L, Smith TW, Kelly RA, Michel T. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase targeting to caveolae. Specific interactions with caveolin isoforms in cardiac myocytes and endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:22810–22814. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.37.22810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Garcia-Cardena G, Martasek P, Masters BS, Skidd PM, Couet J, Li S, Lisanti MP, Sessa WC. Dissecting the interaction between nitric oxide synthase (NOS) and caveolin. Functional significance of the NOS caveolin binding domain in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:25437–25440. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.25437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Feron O, Saldana F, Michel JB, Michel T. The endothelial nitric-oxide synthase-caveolin regulatory cycle. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:3125–3128. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.6.3125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bivalacqua TJ, Liu T, Musicki B, Champion HC, Burnett AL. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase keeps erection regulatory function balance in the penis. Eur Urol. 2007;51:1732–1740. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.10.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]