Abstract

The study investigated the effects of two stabilization exercise positions (prone and supine) on pain intensity (PI) and functional disability (FD) of patients with nonspecific chronic low back pain (NSCLBP). The 56 subjects that completed the study were randomly assigned into stabilization in prone (SIP) (n=19), stabilization in supine (SIS) (n=20), and prone and supine (SIPS) position (n=17) groups. Subjects in all the groups received infrared radiation for 15 min and kneading massage at the low back region. Subjects in SIP, SIS, and SIPS groups received stabilization exercise in prone lying, supine lying and combination of both positions respectively. Treatment was applied twice weekly for eight weeks. PI and FD level of each subject were measured at baseline, 4th and 8th week of the treatment sessions. Data were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics. The alpha level was set at P<0.05. Within-group comparison indicated that PI and FD at the 4th and 8th week were significantly reduced (P<0.001) when compared with baseline in all the three groups. However, the result showed that there was no significant difference in the PI and FD at the 8th week (P>0.05) of the treatment sessions across the three groups when compared. It can be concluded that stabilization exercises carried out in prone, supine and combination of the two positions were equally effective in managing pain and disability of patients with NSCLBP. However, no position was superior to the other.

Keywords: Stabilization exercises, Prone lying, Supine lying, Pain intensity, Functional disability

INTRODUCTION

Low back pain (LBP) had been a major public health problem all over the world in which most people had suffered series of incapacity at one time or the other (Koley and Sandhu, 2009). It is a prevalent musculoskeletal condition, and a common cause of disability especially in its chronic/recurrent state (Esther, 2012). LBP has a point prevalence of about 7% to 33% and lifetime prevalence of nearly 85% (Walker, 2000). The report of Louw et al. (2007) on LBP in Africa revealed a prevalence of 12% among adolescence and 32% among adult. Omokhodion (2002), conducted a survey in the South-Western part of Nigeria and found that 40% of the sample population had LBP in the past 12 months, whereas 33% had LBP at the time of study, indicating that LBP is a common condition among Africans that is rising and should be of global concern (Omokhodion, 2002).

Nonspecific chronic low back pain (NSCLBP) is a widespread problem which limits activities in middle aged individuals with major social and economic consequences, the commonest reason for physician consultation (Manchikanti et al., 2009). NSCLBP accounts for serious job absenteeism in industrialized societies, a case that would have been similar in most parts of Africa except that there is hardly any financial compensation for sick leave, hence less report of LBP in clinics (Krismer and van Tudler, 2007). LBP is regarded as a symptom from impairments in the structures in the low back which originates from muscles, ligaments and intervertebral disc (Mense and Gerwin, 2014). Implicated muscles in LBP are the lumbar multifidi and abdominals especially the transversus abdominis (Esther, 2012). Evidences by Hides et al. (1992) supported the positive role of the lumbar multifidus muscle in segmental stabilization of the lumbar spine. Among the lumbar muscles which play substantial role of which their strengthening and coordination are necessary for proper function of low back are deep stabilizer muscles; the multifidus muscle, transversus abdominis muscle, and internal oblique abdominal muscle (McGill et al., 2003). Other muscles which serve as superficial stabilizer includes, the erector spinae muscle, rectus abdominis muscle, and external oblique abdominal muscle-play a role in lumbar segmental stability and as a basic support, and for lumbar segmental stabilization (McGill et al., 2003).

Exercise therapy appears to be the most often-used physical therapy intervention in treating people with back pain (Hayden et al., 2012). The aims of exercise therapy are to abolish pain, restoring and maintaining full range of motion, improving the strength and endurance of lumbar and abdominal muscles, thereby contributing to early restoration of normal function (Saunder, 2007). Clinical application of exercise has been shown to improve strength of the muscles of the gluteus resulted in decrease LBP, disability index and increase in lumbar muscle strength and balance ability (Jeong, 2015). Exercises are commonly prescribed for LBP but only seem to be supported as an intervention by evidence for patients with chronic LBP (Esther, 2012). Liddle et al. (2004) and Lewis et al. (2008) in their systematic reviews affirmed that exercises were effective in reducing pain in people with chronic LBP. Most studies concluded that active exercises were a valuable therapeutic approach in managing LBP, despite the lack of consensus on the optimal exercise techniques, intensity or active intervention (Esther, 2012). In a study by França et al. (2010) segmental stabilization and strengthening exercises effectively reduced pain and functional disability in individuals with chronic LBP.

Among the various exercises, stabilization exercises were majorly used to treat pain and dysfunctions in LBP which were reported to enhance control over the lumbar spine and the pelvis (Hodges et al., 2003) and can be performed in diverse body positions using cocontraction of abdominal and multifidus muscles (Andrusaitis et al., 2011). In practice, emphasis had been on exercises in prone and supine lying in order to strengthen different groups of the spinal muscles (Kisner and Colby, 2007). Most clinical protocols combine different exercises, techniques and position, making it difficult to isolate the efficacy of specific strategies and positions (Hayden et al., 2005). This is of great clinical importance and needs to be further clarified through research. Therefore, this study aimed at comparing the effectiveness of two stabilization exercise positions (prone and supine) on the pain intensity and functional disability of patients with NSCLBP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Quasi pre- and postexperimental design was used in this study.

Subjects

Sixty-two subjects attending the Outpatient Physiotherapy Department of the State Specialist Hospital, Asubiaro, Osogbo, Osun state, Nigeria were invited for this study but 56 participated.

Inclusion criteria

The following categories of patients were recruited into the study:

Subjects referred by physician with diagnoses of mechanical LBP of not less than 3 months, with pain being provoked by activity. Subjects whose age ranges from 25 to 65 years and those without defects in the trunk, upper and lower extremities.

Exclusion criteria

Subjects with specific pathology, such as systemic inflammatory diseases (such as systemic lupus erythematous, rheumatoid arthritis, nephritis etc.), prolapsed disc, pregnancy related, fractures (spine or extremities), tumors, infection.

Sampling technique

A purposive sampling technique was used to recruit subject for this study.

Research design

It was a randomized control trial.

Instruments

The following instruments were used in this study:

Infra-Red lamp: Floor model SM-10H. Infrared lamp microfield instrument. Made in England.

Verbal Rating Scale (VRS): The patients place a check mark next to the phrase that best describes the current intensity of their pain. A response of “No Pain” is given a value of zero, 1=mild pain, 2=moderate, 3=severe, 4=very severe, 5=Worst possible pain. The VRS was validated with the visual analogue scale by Williamson and Hoggart (2005), who concluded that VRS provides a useful alternative to the visual analog scores in the assessment of chronic pain.

Rolland Morris Disability Questionnaire: This 24-item questionnaire was derived from the sickness index profile by Bergner et al. (1981). It entails totaling the sum of circled items (maximum, 24), thus representing the final score.

Weighing scale: A Bathroom Weighing Scale manufactured by the Hanson Company of Ireland in the year 2000 (0–120 kg) was used to measure the body weight of subjects in kilogram to the nearest 1.0 kg.

Stadiometer: Made by Prestige Company in China. Calibrated from 20 to 205 cm. It was used to measure the height of the subject to the nearest 0.1 cm.

Tape rule: A Standard Inextensible rule (0.7 cm wide and 150 cm long) made in China was used to measure the waist and hip circumference of the subjects.

Stop watch: A quartz stop watch, made in china, was used to determine the period of exercise activity in seconds.

Sample size calculation

where N is the total sample size, σ is the assumed standard deviation (SD) of each group (assumed to be equal for the three groups) and this is assumed to be 6 (Rosner, 2000).

Zcrit is the standard normal deviate corresponding to the selected significance criterion (i.e., 0.05; 95%=1,960). Zpwr is the standard normal deviate corresponding to the selected statistical power (i.e., 0.80; 95%=0.842). D is the minimum expected difference among the three means and D=5. Therefore:

However, 63 subjects were examined for this study in order to give room for attrition, but 56 completed the study

Procedure

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for this study, with protocol number IPH/OAU/12/492 was obtained from the Health Research and Ethics Committee of the Institute of Public Health Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile Ife before the commencement of the study. The nature and purpose of the study was explained to each subjects and informed consent was obtained.

Assessment

Each subject was screened for eligibility with the following tests according to Konin et al. (2006). They were as follow: Ely’s test, Laseague test, forward flexion, backward extension, side rotation, digital pressure along the spine. If at least two of the tests provoke pain at low back, such patient is qualified for the study. X-ray of such patient was then examined to rule out any red flag signs.

Randomization

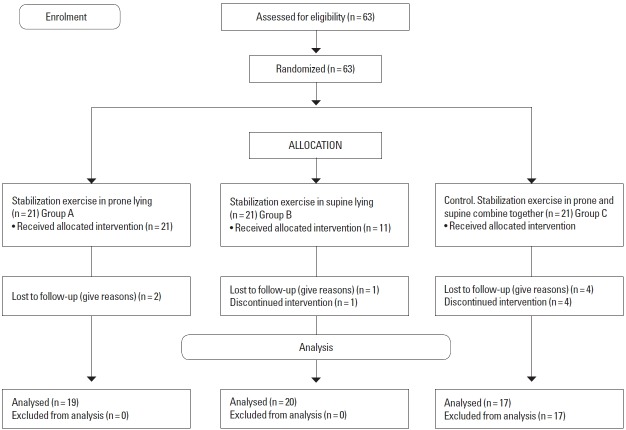

Subjects were randomly allocated into three groups using the fish bowl technique of simple random sampling. Participants were allocated into any of the three treatment groups according to the group a participant picked from the pool of groups stabilization in prone (SIP), stabilization in supine (SIS), prone and supine (SIPS) position in the bowl (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Consort diagram of random allocation of subjects into the three groups.

Measurements

Before the treatment the weight, height, waist and hip circumference of each subject were measured according to Lean et al. (2013). Initial pain intensity was assessed using VRS and disability was examined with Rolland Morris Disability Questionnaire.

Outcome measures

Verbal Rating Scale

This was used to measure subject’s present pain intensity verbally (i.e. pain at the time of study), at the beginning, 4th and 8th weeks of the treatment sessions.

The Rolland Morris Disability Questionnaire

It is a commonly utilized instrument for measuring spinal disability as an outcome measure. Assessment of functional disability was done at baseline, 4th and 8th weeks of intervention using RMLDQ.

Intervention

After the assessment, all the subjects received infrared radiation therapy for 15 min, according. Kneading massage with Neurogesic greaseless ointment was also given as base line treatments.

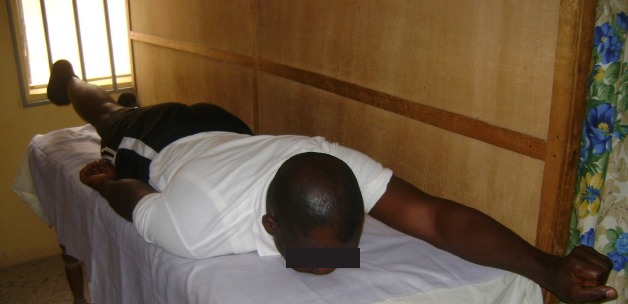

SIP position

Subjects in prone group received stabilization exercise in prone lying position. The following were the three exercises done in prone lying position. The exercises were done according to Sung (2013).

Exercise 1: Subject position the 2 arms by the side, lifting the head and chest off the plinth for 3 to 5 sec, two sets of 15 repetitions, performed as tolerated. Exercise 2 includes the alternate arm and leg lifted off the plinth from neutral position to extension simultaneously. The position was maintained for 3 to 5 sec and then returned, two sets of 15 repetitions performed as tolerated and in the third exercises one leg was lifted off the plinth with the hip hyper extended, knee extended and both arms stretched forward on the plinth. This position was maintained for 3 to 5 sec and then returned. Two sets of 15 repetitions performed as tolerated (Figs. 2–4).

Fig. 2.

Exercise 1: prone position lifting head and chest off the plinth from neutral position, with both arms by the side.

Fig. 3.

Exercise 2: prone lying position with alternate arm and leg lifted off the plinth from neutral to extension.

Fig. 4.

Exercise 3: prone lying with one leg lifted off the plinth with the hip hyper extended, knee extended and both arms stretched forward on the plinth.

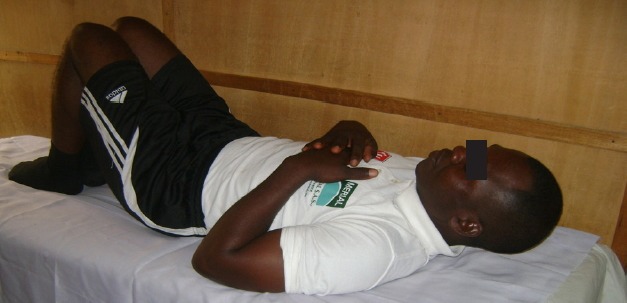

SIS position

Subjects in supine group received stabilization exercise in supine lying position. The following were the three exercises done according to Sung (2013). Alternate arm and leg lifted off the plinth from neutral position with the arm extended, knee and hip flexed. This position was maintained for 3 to 5 sec and then returned, two sets of 15 repetitions performed as tolerated. Exercise 2 includes knee drag to the chest from neutral position with both arms on the plinth. The knee was held off the plinth for 3 to 5 sec and then returned, two sets of 15 repetitions were performed as tolerated. And the third exercise involved the head and trunk slightly lifted off the plinth for 3 to 5 sec, two sets of 15 repetitions performed as tolerated (Figs. 5–7).

Fig. 5.

Exercise 4: supine lying alternate arm and leg lifted off the plinth from neutral position with the arm extended, knee and hip flexed.

Fig. 6.

Exercise 5: supine lying knee drag to chest from neutral position with both arms on the plinth.

Fig. 7.

Exercise 6: mini curl up: subject slightly lifted the head and neck off the plinth.

SIPS positions

Subjects in the combined group received SIPS lying positions combined (control group). Those in this group did any two exercise protocols each from both prone and supine positions. Exercise regimens were the same as in the other groups.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS ver. 17 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The analyses were summarized using descriptive and inferential statistics. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the mean values of the physical characteristics of all the subjects in the three groups. Repeated measure ANOVA was used to compare the mean values of the outcome measures within and among the groups. Post hoc least of significant difference comparison was carried out where appropriate. Alpha level of 0.05 was set as significant level.

RESULTS

Physical characteristics of the subjects

Presented in Table 1 were the physical characteristics of all the subjects in the three groups. It was observed that the mean age of subjects in the SIP group was 52.18±9.99 years, SIS group was 54.36±12.81 years while SIPS group was 48.63±11.90 years and the sum total was 51.72±11.51 years. There was no significant difference in the physical characteristics, among the three groups (P>0.05).

Table 1.

Comparison of the physical characteristics among the three groups

| Variable | SIP (n=19) | SIS (n=20) | SIPS (n=17) | F | P-value | All subjects (n=56) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 52.18±9.99 | 54.36 ±12.81 | 48.63±11.90 | 0.679 | 0.515 | 51.72±11.51 |

| Weight (kg) | 72.81±10.73 | 68.03 ±17.19 | 71.54±9.93 | 0.397 | 0.676 | 70.80±12.78 |

| Height (m) | 1.59±0.07 | 1.62±0.09 | 1.61±0.04 | 0.539 | 0.589 | 1.61±0.07 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.36±3.58 | 25.86±7.05 | 27.45±3.80 | 0.685 | 0.512 | 27.22±5.02 |

| WC (cm) | 86.77±16.32 | 88.63±19.12 | 89.45±5.71 | 0.094 | 0.911 | 88.28±14.46 |

| HC (cm) | 96.47±18.74 | 95.63±15.78 | 99.50±11.39 | 0.187 | 0.831 | 97.20±15.20 |

| WRC (cm) | 16.22±0.56 | 16.63±1.79 | 16.77±0.75 | 0.650 | 0.529 | 16.55±1.15 |

| WHR | 0.91±0.18 | 0.89±0.12 | 0.90±0.09 | 0.054 | 0.948 | 0.90±0.13 |

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation.

BMI, body mass index; WC, waist circumference; HC, hip circumference; WRC, wrist circumference; WHR, waist to hip ratio; SIP, stabilization in prone group; SIS, stabilization in supine group; SIPS, stabilization in prone and supine group.

Comparison of pain intensity and disability index among pretreatment, 4th and 8th week in SIP position group

Presented in Table 2 is the result of comparison of outcome measures of stabilization exercise in prone position group. The result revealed that there was a significant reduction between pretreatment, 4th week of PI (F=22.500, P<0.001) and DI (F= 15.582, P<0.001) and 8th week.

Table 2.

Comparison of pain intensity and disability index among pretreatment, 4th and 8th week of stabilization exercise in prone position group (n=19)

| Variable | Week | Mean±SD | F | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain Intensity | Pretreatment | 2.09±0.70 | ||

| 4th week | 1.27±0.83 | 22.500 | 0.000*** | |

| 8th week | 0.45±0.52 | |||

|

| ||||

| Disability Index | Pretreatment | 10.09±4.78 | ||

| 4th week | 4.27±3.22 | 15.582 | 0.000*** | |

| 8th week | 1.72±2.37 | |||

Significant at P<0.001.

Comparison of pain intensity and disability index among pretreatment, 4th and 8th week in SIS position group

Presented in Table 3 is the result of comparison of outcome measures of SIS position group. The result revealed that there was a significant reduction when pretreatment, 4th week of PI (F= 13.314, P<0.001) and DI (F=15.95 P<0.001) and 8th week were compared.

Table 3.

Comparison of pain intensity and disability index among pretreatment, 4th and 8th week of stabilization exercise in supine position group (n=20)

| Variable | Weeks | Mean±SD | F | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain intensity | Pretreatment | 2.00±0.70 | ||

| 4th week | 0.90±0.83 | 13.314 | 0.000** | |

| 8th week | 0.45±0.52 | |||

|

| ||||

| Disability index | Pretreatment | 7.82±3.97 | ||

| 4th week | 2.27±3.06 | 15.95 | 0.000** | |

| 8th week | 1.00±1..41 | |||

Significant at P<0.001.

Comparison of pain intensity and disability index among pretreatment, 4th and 8th week in SIPS position group

Presented in Table 4 is the result of comparison of outcome measures of stabilization exercise in both prone and supine position group. The result revealed that there was a significant reduction between pretreatment and 4th week PI (F=17.894, P< 0.001) and DI (F=17.200 P<0.000) and 8th week.

Table 4.

Comparison of pain intensity and disability index among pretreatment, 4th and 8th week of stabilization exercise in combine positions group (n=17)

| Variable | Weeks | Mean±SD | F | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain intensity | Pretreatment | 2.09±0.70 | ||

| 4th week | 1.90±0.70 | 17.894 | 0.000*** | |

| 8th week | 0.45±0.52 | |||

|

| ||||

| Disability index | Pretreatment | 11.18±5.51 | ||

| 4th week | 3.82±3.71 | 17.200 | 0.000*** | |

| 8th week | 1.64±1.96 | |||

Significant at P<0.001.

Comparison of PI and DI among the SIP, SIS, and SIPS were shown in Table 5. There was no significant difference when the pretreatment (F=0.57, P>0.05), 4th week (F=0.779, P>0.468) and 8 week (F=0.000, P>1.000) pain intensity and disability index were compared across the groups.

Table 5.

Comparison of pain intensity and disability index among pretreatment, 4th and 8th week of within the SIP, SIS, and SIPS position groups (n=57)

| Variable | Weeks | SIP | SIS | SIPS | F | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain intensity | Pretreatment | 2.09±0.70 | 2.00±0.70 | 2.09±0.70 | 0.57 | 0.944 |

| 4th week | 1.27±0.83 | 0.90±0.83 | 1.90±0.70 | 0.779 | 0.468 | |

| 8th week | 0.45±0.52 | 0.45±0.52 | 0.45±0.52 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |

|

| ||||||

| Disability index | Pretreatment | 10.09±4.78 | 7.82±3.97 | 11.18±5.51 | 1.408 | 0.260 |

| 4th week | 4.27±3.22 | 2.27±3.06 | 3.82±3.71 | 1.080 | 0.353 | |

| 8th week | 1.72±2.37 | 1.00±1..41 | 1.64±1.96 | 0.452 | 0.641 | |

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation.

SIP, stabilization in prone; SIS, stabilization in supine; SIPS, stabilization in prone and supine.

DISCUSSION

The specific objective of this study was to assess which position is more effective for administration of stabilization exercises for patients with NSCLBP. The evaluated positions are prone lying, supine lying and combination of both supine and prone lying.

It was observed from this study that the physical characteristics of the subjects in the three groups were not significantly different from each other. This is an indication that subjects in the three groups were comparable. The study observed a significant reduction at the 4th and 8th week of outcome measures when compared with the baseline of the subjects that underwent exercise in prone lying position. This inferred that stabilization exercises in prone position is indicated in the treatment of NSCLBP. Smith et al. (2014) reported that stabilization or (core stability exercise) have been suggested to reduce symptoms of pain and disability and form an effective treatment in patients with LBP. The determinant of spinal stability is the strength of the muscles and osteoligamentous structures of the trunk (Arokoski et al., 2004). In a case of excessive loading of the ostoeoligamentous structures of the spine that may occur in normal daily activities; which at times leading to damage of the spine, it is the responsibility of the lumbar and abdominal muscles to provide the essential stiffness needed for maximal loading in order to prevents such injury from overload (Gardner-Morse and Stokes, 1998). Stabilization exercises improves the strength of such ligaments and hence improves the activities of the back musculature.

This study also observed a significant reduction when the baselines outcome measures were compared with the 4th and 8th week measurements of subjects that underwent exercise in supine lying position. It can be inferred that stabilization exercise in supine lying is indicated in the management of NSCLBP. In patients with chronic LBP, there is impairment of stabilizers of the back especially extensors with respect to coordination and functions as a result of disuse and deconditioning associated with muscle atrophy (Mannion et al., 2000). It is hence imperative that a specific back exercise programme is purposefully directed to this group of muscles, in which stabilization exercise in supine lying is accounted for.

Again our study observed a significant reduction between the baselines, 4th and 8th weeks of pain intensity and disability of subjects that underwent exercise in prone and supine lying positions combined. This result is in line with the result of other authors which reported that specific lumbar stabilizing therapy can reduce the intensity of the pain and disability in LBP and pelvic girdle pain patients when used as a single therapy or combined with other treatments (Koumantakis et al., 2005). It was also in accordance with the work of Lee et al. (2012) which concluded that lumbar rehabilitation exercise program reduced pain and disability in patients with chronic mechanical LBP. Based on the stability of the trunk, there are local and global muscle stabilizers from which multifidus, transversus abdominis, and obliquus abdominis form the local; while longissimus thoracic, rectus abdominis, and obliquus externus abdominis muscles form the global stabilizers (Bergmark, 1989). Stabilization exercises especially in both prone and supine lying were directed to strengthen those muscles.

Increment of muscle strength and balance in lumbar spine and relief of pain could be achieved by stabilizing exercise, functional exercise and resistance exercise (Park and Kim, 2012). More importantly, all exercises carried out in our study were isometric in nature. Researches have documented that isometric exercises has hypoalgesic effect on the contracting body part, the contralateral and a distant body part to the contracting one (Kadetoff and Kosek, 2007). This implies that isometric exercises activate a central inhibitory pain mechanism by static muscle contraction (Kosek and Lundberg, 2003); the mechanism involves upsurge in secretion of beta-endorphins, attention mechanism, activation of diffuse inhibitory controls or interaction of systems that regulate the pain (Lannersten and Kosek, 2010). In addition, isometric exercises activates the secretion of endogenous opioid system which reduces pain perception (Stagg et al., 2011).

In conclusion, stabilization exercises carried out in prone, supine or the combination of both positions were effective on pain intensity and disability of patients with NSCLBP.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to acknowledge the effort of Mr Olufemi Olusegun, the Head, Physiotherapy Department, and all Physiotherapist at the State Specialist Hospital Asubiaro, Osogbo Osun State, Nigeria especially during the data collection of the study.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

REFERENCES

- Andrusaitis SF, Brech GC, Vitale GF, Greve JM. Trunk stabilization among women with chronic lower back pain: a randomized, controlled, and blinded pilot study. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2011;66:1645–1650. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322011000900024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arokoski JP, Valta T, Kankaanpää M, Airaksinen O. Activation of lumbar paraspinal and abdominal muscles during therapeutic exercises in chronic low back pain patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:823–832. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2003.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmark A. Stability of the lumbar spine. A study in mechanical engineering. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl. 1989;230:1–54. doi: 10.3109/17453678909154177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergner M, Bobbitt RA, Carter WB, Gilson BS. The sickness impact profile: development and final revision of a health status measure. Med Care. 1981;19:787–805. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198108000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esther JO. Therapeutic exercises in the management of non-specific low back pain. In: Norasteh AA, editor. Low back pain. Croatia (EU): InTech; 2012. pp. 225–246. [Google Scholar]

- França FR, Burke TN, Hanada ES, Marques AP. Segmental stabilization and muscular strengthening in chronic low back pain: a comparative study. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2010;65:1013–1017. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322010001000015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner-Morse MG, Stokes IA. The effects of abdominal muscle coactivation on lumbar spine stability. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1998;23:86–91. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199801010-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden JA, Cartwright JL, Riley RD, Vantulder MW Chronic Low Back Pain IPD Meta-Analysis Group. Exercise therapy for chronic low back pain: protocol for an individual participant data meta-analysis. Syst Rev. 2012;1:64. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-1-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden JA, van Tulder MW, Malmivaara AV, Koes BW. Meta-analysis: exercise therapy for nonspecific low back pain. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:765–775. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-9-200505030-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hides JA, Cooper DH, Stokes MJ. Diagnostic ultrasound imaging for measurement of the lumbar multifidus muscle in normal young adults. Physiother Ther Pract. 1992;8:19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hodges PW, Moseley GL, Gabrielsson A, Gandevia SC. Experimental muscle pain changes feedforward postural responses of the trunk muscles. Exp Brain Res. 2003;151:262–271. doi: 10.1007/s00221-003-1457-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong UC, Sim JH, Kim CY, Hwang-Bo G, Nam CW. The effects of gluteus muscle strengthening exercise and lumbar stabilization exercise on lumbar muscle strength and balance in chronic low back pain patients. J Phys Ther Sci. 2015;27:3813–3816. doi: 10.1589/jpts.27.3813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadetoff D, Kosek E. The effects of static muscular contraction on blood pressure, heart rate, pain ratings and pressure pain thresholds in healthy individuals and patients with fibromyalgia. Eur J Pain. 2007;11:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisner C, Colby LA. Therapeutic exercise foundation and techniques. 5th ed. Philadelphia (PA): F.A. Davis; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Koley S, Sandhu NK. An association of body composition components with the menopausal status of patients with low back pain in Tarn Taran, Punjab, India. J Life Sci. 2009;1:129–132. [Google Scholar]

- Konin JG, Denise LW, Jerome A, Holly B. Special tests for orthopaedic examination. 3rd ed. Minneapolis (MN): OPTP; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kosek E, Lundberg L. Segmental and plurisegmental modulation of pressure pain thresholds during static muscle contractions in healthy individuals. Eur J Pain. 2003;7:251–258. doi: 10.1016/S1090-3801(02)00124-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koumantakis GA, Watson PJ, Oldham JA. Trunk muscle stabilization training plus general exercise versus general exercise only: randomized controlled trial of patients with recurrent low back pain. Phys Ther. 2005;85:209–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krismer M, van Tulder M Low Back Pain Group of the Bone and Joint Health Strategies for Europe Project. Strategies for prevention and management of musculoskeletal conditions. Low back pain (non-specific) Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2007;21:77–91. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lannersten L, Kosek E. Dysfunction of endogenous pain inhibition during exercise with painful muscles in patients with shoulder myalgia and fibromyalgia. Pain. 2010;151:77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lean ME, Katsarou C, McLoone P, Morrison DS. Changes in BMI and waist circumference in Scottish adults: use of repeated cross-sectional surveys to explore multiple age groups and birth-cohorts. Int J Obes (Lond) 2013;37:800–808. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2012.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DJ, Lee HJ, Han SW. The Influence of a exercise program on muscle thickness, maximum muscular strength, and pain reduction in the trunk region of participants with low back pain. J Sport Leis Stud. 2012;49:811–819. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis A, Morris ME, Walsh C. Are physiotherapy exercises effective in reducing chronic low back pain? Phys Ther Rev. 2008;13:37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Liddle SD, Baxter GD, Gracey JH. Exercise and chronic low back pain: what works? Pain. 2004;107:176–190. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2003.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louw QA, Morris LD, Grimmer-Somers K. The prevalence of low back pain in Africa: a systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2007;8:105. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-8-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manchikanti L, Boswell MV, Singh V, Benyamin RM, Fellows B, Abdi S, Buenaventura RM, Conn A, Datta S, Derby R, Falco FJ, Erhart S, Diwan S, Hayek SM, Helm S, Parr AT, Schultz DM, Smith HS, Wolfer LR, Hirsch JA ASIPP-IPM. Comprehensive evidence-based guidelines for interventional techniques in the management of chronic spinal pain. Pain Physician. 2009;12:699–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannion AF, Käser L, Weber E, Rhyner A, Dvorak J, Müntener M. Influence of age and duration of symptoms on fibre type distribution and size of the back muscles in chronic low back pain patients. Eur Spine J. 2000;9:273–281. doi: 10.1007/s005860000189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGill SM, Grenier S, Kavcic N, Cholewicki J. Coordination of muscle activity to assure stability of the lumbar spine. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2003;13:353–359. doi: 10.1016/s1050-6411(03)00043-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mense S, Gerwin RD. Muscle pain: diagnosis and treatment. Heidelberg: Springer; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Omokhodion FO. Low back pain in a rural community in South West Nigeria. West Afr J Med. 2002;21:87–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JK, Kim KW. The analysis of stabilization exercise on lumbar extension strength, balance ability in adult female of chronic back pain patients. Korean J Sports Sci. 2012;21:1129–1138. [Google Scholar]

- Rosner B. Fundamental of biostatistics. 5th ed. Pacific Grove (CA): Duxbury; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders DG. Therapeutic exercise. Clin Tech Small Anim Pract. 2007;22:155–159. doi: 10.1053/j.ctsap.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith BE, Littlewood C, May S. An update of stabilisation exercises for low back pain: a systematic review with meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:416. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-15-416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stagg NJ, Mata HP, Ibrahim MM, Henriksen EJ, Porreca F, Vanderah TW, Philip Malan T., Jr Regular exercise reverses sensory hypersensitivity in a rat neuropathic pain model: role of endogenous opioids. Anesthesiology. 2011;114:940–948. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318210f880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung PS. Disability and back muscle fatigability changes following two therapeutic exercise interventions in participants with recurrent low back pain. Med Sci Monit. 2013;19:40–48. doi: 10.12659/MSM.883735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker BF. The prevalence of low back pain: a systematic review of the literature from 1966 to 1998. J Spinal Disord. 2000;13:205–217. doi: 10.1097/00002517-200006000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson A, Hoggart B. Pain: a review of three commonly used pain rating scales. J Clin Nurs. 2005;14:798–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2005.01121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]