Abstract

Introduction

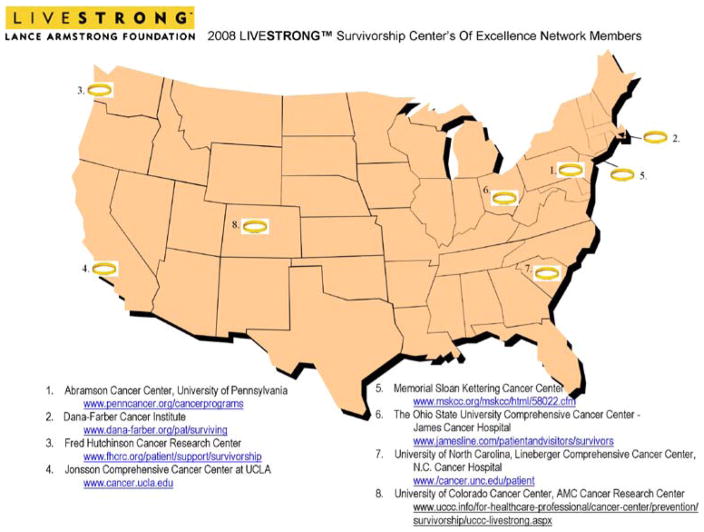

The LIVESTRONG™ Survivorship Center of Excellence Network consists of eight National Cancer Institute-designated Comprehensive Cancer Centers funded by the LAF between 2004 and 2008. The Network was created to accelerate the pace of progress in addressing the needs of the growing survivor community.

Methods

This paper will briefly describe some of the salient issues surrounding the care of cancer survivors, and examine models of survivorship care that are being developed in individual Centers of Excellence (COE) as well as in the overall Network.

Results and Conclusions

As the recommendations and policies for optimal survivorship care have to be feasible and relevant in the community setting, each COE is partnered with up to three community affiliates. Through these partnerships, the community affiliates develop survivorship initiatives at their institutions with support and guidance from their primary COE.

Keywords: Lance armstrong foundation

Introduction

Cancer survivor and champion cyclist Lance Armstrong founded the Lance Armstrong Foundation (LAF) in 1997 as a means to unite, inspire and empower individuals affected by cancer. Among the many accomplishments of the LAF during the past 11 years, is the creation of the LIVESTRONG™ Survivorship Center of Excellence Network.[1] This Network consists of eight National Cancer Institute-designated Comprehensive Cancer Centers (CCC) funded by the LAF between 2004 and 2008 (Fig. 1). It was created to accelerate the pace of progress in addressing the needs of the growing survivor community. The goals of the Network are to 1) increase the quality of life for individuals living with, through, and beyond cancer; 2) transform how survivors are treated and served; 3) contribute to the collective body of knowledge on survivorship; 4) increase the accessibility and quality of services for survivors and their seamless integration into primary cancer treatment; and 5) explore reimbursement issues and develop financial strategies to cover the cost of survivor care.

FIGURE 1.

LIVESTRONG Survivorship Center of Excellence Network.

This review will briefly describe some of the salient issues surrounding the care of cancer survivors, and examine models of survivorship care that are being developed in individual Centers of Excellence (COE) as well as in the overall Network. An overriding goal of the Network is the development of best practices regarding survivorship care that can be disseminated beyond the confines of COE to the general community. The majority of cancer survivors will receive treatment and be followed in community settings; hence it is essential that models of care respond to these community-based needs as well as defining models that utilize the full resources of COE. As the recommendations and policies for optimal survivorship care have to be feasible and relevant in the community setting, each COE is charged with partnering with up to three community affiliate partners that in the majority of cases serve the economically disadvantaged and/or racial and ethnic minorities. Through these partnerships, the community affiliates are provided with limited funding to develop survivorship initiatives at their institutions with support and guidance from their primary COE.

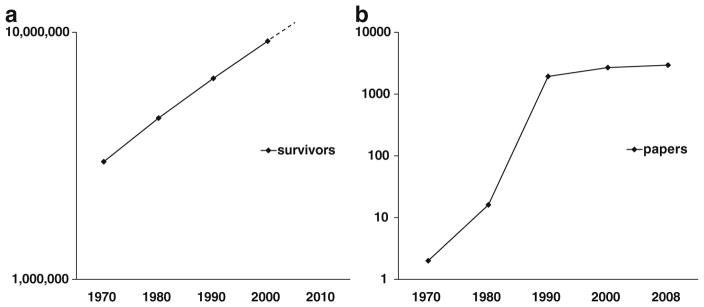

Survivorship care: a new academic discipline

As a result of the increased utilization of screening and earlier detection of common cancers (i.e., breast, colorectal, and prostate) coupled with incremental improvements in cancer treatment and supportive care, the number of cancer survivors in the United States has increased from about 3 million in 1970 to almost 11 million in 2004 (Fig. 2a; www.seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2004/). A Med-line search was performed using the key words “Cancer Survivorship” starting with 1970. There was exponential growth in the number of papers related to cancer survivorship that were published over the past 40 years (Fig. 2b). Thus, survivor-ship and its varied dimensions have become a separate, but related, discipline of oncology that requires expertise and the infrastructure to provide optimal care for cancer survivors. In addition, several journals have dedicated recent issues to survivorship, [2–4] and a new Journal of Cancer Survivorship was initiated in 2007. This proliferation of publications documents the value of research dedicated to maintaining optimal health (both physical and emotional) and for improving overall quality-of-life for cancer survivors.

FIGURE 2.

a Exponential increase in number of cancer survivors since 1970. b Exponential rise in academic publications with key words “cancer survivorship” starting in 1970.

What is the definition of a cancer survivor?

It is instructive to review the definitions of cancer survivor since this term has been defined differently by professional groups as well as patient advocacy groups, depending upon the populations they serve. Pediatric cancer survivors mainly include individuals without evidence of disease recurrence from the original primary cancer. About 80% of children with cancer are cured but are subject to a myriad of treatment-related late effects. [5, 6] Evidence-based and Expert Panel Consensus-based guidelines have been formulated to provide guidance for the follow-up care of pediatric cancer survivors. [7, 8] (See also version 2.0 “Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines for Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancers” March 2006 at www.childrensoncologygroup.org)

When it comes to adult cancer survivors the definitions of survivorship are varied (Table 1). For example, the National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship (NCCS), the NCI Office of Survivorship, along with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the LAF, in their joint publication A National Action Plan for Cancer Survivorship: Advancing Public Health Strategies (www.cdc.gov/cancer), described individuals living with cancer, their families as well as their care givers, “From the day of diagnosis through the remainder of their lives”. This definition is important for several reasons: 1) it expands the scope to include the family and care givers; and 2) it expands the window of time to include the cancer diagnosis, active treatment, cancer-free interval, after a recurrence or second cancer, and issues that accompany the end of life. In this context, cancer survivorship is a continuum with different phases as opposed to being focused only on the cancer-free interval. [9–11] The expanded definition of cancer survivorship and the recognition of the survivorship continuum present challenges to institutions relative to the resources and infrastructure required to provide optimal survivorship care. To focus on the unmet needs of survivors beyond traditional oncology and primary care, most of the Network members have elected to focus their efforts on those who have completed active cancer treatment.

Table 1.

Definitions of adult cancer survivor

| National Cancer Institute: www.cancer.gov | Cancer survivor is one who remains alive and continues to function after overcoming difficulties or life-threatening diseases like cancer |

| National coalition for cancer survivorship www.canceradvocacy.org and office of cancer survivorship www.dccps.nci.nih.gov/ocs | Cancer survivor is from the time of diagnosis and for the balance of life. This has been expanded to include family, friends and caregivers |

| Centers for disease control (CDC) and prevention, cancer survivorship www.cdc.gov/cancer/survivorship/ and LAF | Cancer survivors are people who have been diagnosed with cancer and those in their lives who are affected by the diagnosis, including family members, friends, and caregivers |

LAF lance armstrong foundation

National efforts in cancer survivorship

During the past 15 years a number of National organizations have made substantial contributions to raising awareness and influencing policy at the National level regarding cancer survivorship issues (Table 2). Perhaps the most influential of these is the Institute of Medicine report entitled “From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor. Lost in Transition” issued in 2006. [12] This report contained ten recommendations (Table 3) that set the agenda and serves as a blueprint for the ways in which the various dimensions of survivorship care following active treatment can be integrated into a comprehensive care plan supported by policies enacted at the Federal, State, and Local levels. As will be noted below, the LIVESTRONG™ Network is strategically addressing many of these key recommendations.

Table 2.

Selected national organizations and reports in survivorship

| Cancer leadership council (CLC) www.cancerleadership.org | A patient-centered forum of national advocacy organization addressing public policy issues in cancer. Founded in 1993 by 8 cancer patient organizations that wished to voice concerns of cancer survivors during the debate on reform of the health care system. Over the past 8 years it has grown to include additional cancer patient organizations, professional societies, and research organizations |

| Cancer Quality Alliance (CQA) www.cancerqualityalliance.org | The american society of clinical oncology (ASCO) and the national coalition for cancer survivorship (NCCS) formed CQA in 2005. Membership includes cancer care providers, patient advocacy groups, certifying and accrediting organizations, public and private payers, federal agencies, foundations and other national organizations involved in improving the quality of cancer care |

| The national action plan www.cdc.gov/cancer/survivorship | Created by the LAF and centers for disease control (CDC), the goal of the national action plan is to identify and prioritize cancer survivorship needs and strategies within public health that will lead to improved quality of life for the millions of Americans who are living with, through, and beyond cancer |

| National coalition for cancer survivorship (NCCS) www.canceradvocacy.org | The NCCS defines three types of advocacy: self-advocacy; advocacy for others; and public interest advocacy. In 2006, NCCS drafted the comprehensive cancer care improvement Act (CCCIA) that was introduced to congress. The legislation aims to ensure individuals with cancer access to care that combines curative therapy with symptom management; integration of care; improved communication between patients and physicians; and options for follow-up care are a focus of this legislation. The legislation has been reintroduced in early 2007 as H.R. 1078 |

| Institute of medicine (IOM) and national cancer policy forum www.iom.edu | The IOM established the national cancer policy forum in 2005 as the successor to the national cancer policy board (1997–2005). IOM and the national research council issued the report in 2005 entitled “from cancer patient to cancer survivor. Lost in transition [2] |

| President’s cancer panel www.deainfo.nci.nih.gov/advisory/pcp/pcp. | The president’s cancer panel is a three-person panel that reports to the president on the national cancer program. In May 2004 the annual report was entitled “Living beyond cancer: finding a new balance” |

Table 3.

Ten recommendations of the IOM report

| 1 | Health care providers, advocates and other stakeholders should raise awareness of the needs of cancer survivors, establish cancer survivorship as a distinct phase of cancer care, and act to ensure the delivery of appropriate survivorship care. |

| 2 | Patients completing primary cancer treatment should be provided with a comprehensive care summary and follow-up plan written by the health care provider(s) who provided cancer |

| 3 | Systematically developed evidence-based clinical practice guidelines, assessment tools, and screening instruments should be developed to manage late effects of cancer and its treatment |

| 4 | Quality of survivorship care measures should be developed through public/private partnerships and quality assurance programs implemented by health systems to monitor and improve the care that all survivors receive |

| 5 | The centers for medicare and medicaid services, national cancer institution, agency for healthcare research and quality, the department of veterans affairs, and other quality organizations should support demonstration programs to test models of coordinated, interdisciplinary survivorship care in diverse communities and across systems of care |

| 6 | Congress should support the CDC, the States and other collaborating institutions in developing comprehensive cancer control plans that include survivorship care. Community-based services and plans generated by public health agencies or public health practitioners are the key to establishing successful disease prevention activities of relevance to cancer survivors |

| 7 | The NCI, professional associations and voluntary organizations should expand and coordinate efforts to provide educational opportunities to health care providers to equip them to address the health care and quality of life issues facing cancer survivors |

| 8 | Employers, legal advocates, health care providers, sponsors of support services and government agencies should act to eliminate discrimination and minimize adverse effects of cancer on employment, while supporting cancer survivors with short-term and long-term limitations in ability to work |

| 9 | Federal and state policy makers should act to ensure that all cancer survivors have access to adequate and affordable health insurance; insurers and payors of health care should recognize survivorship care as an essential part of cancer care and design benefits, payment policies and reimbursement mechanisms to facilitate coverage for evidence-based aspects of care |

| 10 | The NCI and funding agencies as well as private health insurers should increase their support of survivorship research and expand mechanisms for its conduct. New research initiatives focused on caner patient follow-up are urgently needed to guide effective survivorship care |

Purpose of the network

The COE within each Network is described briefly in Table 4 and as stated, one purpose of the Network is to accelerate progress in addressing the needs of the growing survivor community as well as to improve the quality of life of individuals living with, through, and beyond cancer. Another goal of the Network is to examine and transform how survivors are treated and served in a variety of settings (i.e., urban versus rural; higher versus lower socioeconomic status; non-minority versus racial and ethnic minorities); stimulating survivorship research; and improving the quality and integration of care among health care providers caring for cancer survivors.

Table 4.

Descriptions of each Center of Excellence

| Institution/Director | Year began | Survivorship clinic models | Community affiliates | Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UCLA, Jonsson CCC www.cancer.ucla.edu | 2006 | Consultative (A) LTFU (P) | 3 | Behavioral interventions; health care outcomes, nutritional interventions; and symptom control |

| Dana-Farber cancer institute www.danafarber.org/pat/surviving | 2004 | Consultative (A, The LAF adult survivorship clinic) LTFU (P) | 3 | Descriptive and analytic studies of morbidity in survivors and health services research. |

| Fred Hutchinson Can Res Center www.fhcrc.org/patient/support/survivorship | 2006 | Consultative (A) LTFU (P and A) | 3 | Quality of life, health care outcomes longitudinal studies, web-based interventions, physical activity interventions, and biobehavioral mechanisms |

| Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center www.mskcc.org/mskcc/html/58022.cfm | 2005 | In Clinic (A) LTFU (P and A) Adult Survivors of Pediatric Cancer | 3 | Interventions to address treatment-related effects; physical activity interventions; sexual functioning, sleep disturbances; and speech rehabilitation. Health care outcomes |

| Univ Colorado Cancer Center www.uccc.info/for-healthcare-professional/cancercenter/prevention/Survivorship/uccc-livestrong.aspx | 2006 | Consultative (A, P) | 3 | Telephone counseling interventions |

| OSUCCC–James Cancer Hospital www.jamesline.com/patientsandvisitors/survivorship | 2007 | Consultative (A) Pediatric Transition LTFU (P) | 2 | Interventions to address treatment-related effects; fatigue, lymphedema, nutritional interventions, bone health and patient- reported outcomes |

| Univ Penn, Abramson Cancer Center www.penncancer.org/cancerprograms | 2007 | Integrative (A) Adult Survivors of Childhood Cancer Transition LTFU (A) | 3 | Interventions to address treatment-related effects (i.e. acupuncture); cardiovascular risk in testicular cancer patients; a population-based study of the genetics of testicular cancer; BMD issues in breast cancer survivors; and needs assessment in testicular cancer survivors. |

| Univ North Carolina CCC http://cancer.unc.edu/patient/ | 2008 | In development |

CCC comprehensive cancer center; A adult, LTFU long-term follow-up, P pediatric, BMD bone mineral density

The second recommendation of the IOM called for a “… comprehensive care summary and follow-up plans…” that is provided to individuals completing their primary cancer treatment. This comprehensive summary called a “Survivorship Care Plan”, [13–16] includes specific details about the type cancer and summary of the treatment; recommended cancer and treatment-specific screening recommendations; lifestyle changes to maintain optimal health of cancer survivors;[17, 18] and providing psychosocial, [19] employment, [20, 21] financial and insurance information, resources and referrals.

The Network is currently collaborating with the Onco-Link (www.oncolink.org) staff at University of Pennsylvania to expand the web-based survivorship care plan and treatment summary, OncoLife™. This collaboration will further define and expand OncoLife™, created in 2007, and include patient as well as provider versions. Currently, OncoLife is a web-based application designed for cancer survivors to input their own treatment information. It creates an individualized survivorship care plan. The new program for professionals or patients will be easy to use making it feasible for widespread distribution to the community affiliates and other survivorship programs that do not wish or do not have resources to develop their own care plans.

Delivering optimal care for survivors

How are we going to deliver optimal survivorship care? There are three models for survivorship care being evaluated by the COE’s. [22, 23] The first is the “consult” model where survivors are seen one time in a comprehensive visit either by a physician and/or a mid-level practitioner(s) with special expertise in survivorship care. Survivors usually complete a set of questionnaires such as a validated depression survey or a distress tool (i.e. see www.nccn.org version 3 January 2008 Distress Tool) have the treatment summary reviewed or generated, and receive a tailored survivorship care plan. [13, 14] When particular concerns are identified by the survivor or through the practitioner exam, resources are provided and referrals are generated. Importantly, the survivorship care plan and other pertinent information are transmitted to the primary care physician, the health care team that delivered the cancer treatment, and a version of the plan is also given to the cancer survivor to facilitate their self-advocacy.

The second model is an ongoing care model in which the care of the survivor is transferred to a physician and/or nurse practitioner with expertise in survivorship care at a predetermined time post-treatment. In this model, screening for anxiety and depression as well as other quality of life issues occurs and the survivor also receives a tailored patient care summary. Communication is maintained with both the primary oncologist and the primary care physician in the community. Of note, some programs are combining these models of care, providing the consultation model to most adult survivors and the ongoing care model to pediatric survivors and some adults as well. As both models are being implemented, the programs are evaluating them for feasibility and measurable outcomes. [22]

The third model integrates survivorship care into the continuum of cancer care provided by the primary oncology team. With this model of care, an end of treatment summary and survivorship care plan are developed at a survivorship visit after completion of treatment and then on a yearly basis by the nurse practitioner on the oncology team. The nurse practitioner reviews this information with the patient, provides them with a copy of the treatment summary and care plan, and copies are sent to other providers. The patient continues to be followed by the oncology team and is transitioned to primary care at some point when deemed appropriate.

Interactions with community partners

Community affiliates are critical members of the Network in that they represent diverse community practice settings that often provide care to underserved populations. There are potentially important differences among minority and low income cancer survivors in a number of areas: the biology of disease and consequently, the overall cancer-specific survival, [24, 25] utilization of cancer support groups, [26] depression and distress, [27] and perceptions of cancer-related information among these group. [28] These are also potentially important considerations in the development of survivorship care programs for underserved populations. Preliminary data from the OSUCCC and James Cancer Hospital LIVESTRONG Survivorship Center and its’ Community Partner, the Holzer Cancer Center, located in the Appalachian region of Ohio serves to illustrate this point.

Relative to the average income in the state of Ohio, the Holzer Cancer Center serves several counties that have lower per capita incomes and higher poverty rates. The population and physician density is also lower in these counties. A cancer survivor survey that reflected available resources and assessment of needs was conducted at both institutions. Although survivors in both institutions ranked “fatigue” and “worried about cancer recurrence” highest, the frequencies of other concerns differed with “paying medical bills” and “support for family members” ranking higher and “healthy diet” and “exercise” ranking lower in the Appalachian cancer survivor group. [29] This information will help to identify priorities and guide the distribution of resources at the OSUCCC and James Cancer Hospital LIVESTRONG Survivorship Center and Holzer Cancer Center. Based on this survey increasing psychosocial support, referrals to a social worker to discuss financial concerns, and providing more educational programs that highlight the importance of diet and exercise to promote overall health for survivors seen at this Center will be developed.

Another example comes from the University of Colorado, where program staff helped the three community affiliate partners (Denver Health Medical Center, Denver, Colorado; St. Mary-Corwin Medical Center, Pueblo, Colorado; and St. Mary’s Hospital and Regional Medical Center, Grand Junction, Colorado) implement resource centers and on-site programs for cancer survivors and their families. The resource centers include over 200 print materials, videos and CDs, book-lending libraries, and computers with Internet access. In addition, a wide range of on-site programs have been implemented as part of this initiative (e.g., cancer-specific support groups, educational programs on diet, nutrition, physical activity, complimentary and alternative medicine), with many of these programs offered on a weekly or bi-weekly basis. During the most recent 12 month period spanning 2007–2008, the three Community Partners reported over 3,500 visits to the resource centers and more than 1,200 participants in the on-site educational and support programs.

Conclusions

The increasing population of cancer survivors necessitates efforts dedicated to defining and providing optimal care for this population. The recommendations from the President’s Cancer Panel, the IOM report, and other National organizations (Tables 2, 3) provide a set of “blueprints” that serve as a call to action for cancer survivors, the health care system, advocacy groups, the local, state and federal government and ultimately society at large. The challenge now is implementing these recommendations and this is the main purpose of the Network and their community affiliate partners. The Network is building the infrastructure to develop feasible interventions and explore the best models of survivorship care and uniquely positioned to identify the critical elements necessary for optimal survivorship follow-up care and to disseminate this information to the largest number of cancer professionals, survivors and their care-givers in diverse settings across the country.

Integrating survivorship into overall cancer care is a major challenge and will require a “paradigm shift.” [30] Are there recent examples of a where this has successfully occurred? The recognition of the breast cancer susceptibility genes BRCA1 and 2 and the development of high-risk breast cancer clinics and genetic counseling services is one such example. About 20 years ago Dr. Mary-Claire King first identified the linkage between early-onset familial breast cancer and chromosome 17q21. [31] About 15 years ago, a few vanguard researchers and cancer centers began to study how best to counsel individuals and their families about hereditary susceptibility to breast cancer. [32, 33] After the genes for BRCA 1 and 2 were cloned, and the testing commercialized by Myriad Laboratories, only a handful of cancer centers around the country were able to provide counseling and genetic testing for BRCA1 and 2, and this was usually done through a research protocol, with certificates of confidentiality that protected the results from getting into the medical record. Over the past decade, with more research and educational efforts by the American Society of Clinical Oncology [34] and others, [35, 36] some oncologists who focus on the treatment of breast cancer are now including genetic counseling and testing within routine practice. [37] Now most health insurers regularly cover the costs of counseling and testing, as well as preventive surgery that may be necessary. The dissemination and acceptance of the importance and value of genetic information of this type has taken time to become integrated into the routine care of breast cancer patients and their families, and only recently did the Senate and House of Representatives pass HR 493 the Genetic Nondiscrimination in Health Insurance Act. This law prohibits group and individual health insurance carriers from using information obtained through genetic testing for underwriting or pricing purposes, and prohibits employers from making hiring and firing decisions based on genetic testing.

As the above example suggests, it may take some time for survivorship care to become integrated into “standard practice” of cancer care. Furthermore, time and research are necessary to accumulate sufficient information to support evidence-based guidelines for follow-up care for adult survivors by linking the adverse long-term effects of cancer treatment to specific exposures and to develop cost-effective interventions that promote healthy lifestyles. Thus, the Network can be viewed as a vanguard in this effort, providing both the infrastructure and well characterized demonstration projects that could, in turn, provide examples for addressing these fundamental challenges and improving survivorship care nationwide.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the Network Steering Committee including Larry Shulman, Barbara Jones, Shelia Santacroce, Majorie Kagawa-Singer, Susan Leigh and Sheldon Greenfield. In addition, the Lance Armstrong Foundation staff, including Suzanne Kho, Director of Programs and Grants, and Caroline Huffman, Senior Program Officer, Survivorship Center Initiative.

Contributor Information

Charles L. Shapiro, Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, Starling-Loving Hall, Rm B405, 320 West 10th Street, Columbus, OH 43210, USA

Mary S. McCabe, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA

Karen L. Syrjala, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA, USA

Debra Friedman, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA, USA.

Linda A. Jacobs, Abramson Cancer Center, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA

Patricia A. Ganz, Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center at UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Lisa Diller, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA, USA.

Marci Campell, Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

Kathryn Orcena, Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, Starling-Loving Hall, Rm B405, 320 West 10th Street, Columbus, OH 43210, USA.

Alfred C. Marcus, AMC Cancer Research Center, University of Colorado Cancer Center, Denver, CO, USA

References

- 1.Carlson RW, Anderson BO, Bensinger W, Cox CE, Davidson NE, Edge SB, et al. NCCN practice guidelines for breast cancer. Oncology (Huntington) 2000;14:33–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rowland J, Hewitt M, Ganz P, editors. Cancer Survivorship. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24:5101–69. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rowland J, Stefanik M. Cancer survivorship: embracing the future. Cancer. 2008;112(S1):2523–26. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Travis LBYJ. Cancer Survivorship. Hematol Oncol Clinics. 2008;22:181–371. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2008.01.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geenen MM, Cardous-Ubbink MC, Kremer LCM, van den Bos C, van der Pal HJH, Heinen RC, et al. Medical assessment of adverse health outcomes in long-term survivors of childhood cancer. JAMA. 2007;297:2705–15. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.24.2705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, Kawashima T, Hudson MM, Meadows AT, et al. Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1572–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa060185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Landier W, Bhatia S, Eshelman DA, Forte KJ, Sweeney T, Hester AL, et al. Development of risk-based guidelines for pediatric cancer survivors: the children’s oncology group long-term follow-up guidelines from the children’s oncology group late effects committee and nursing discipline. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4979–90. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Landier W, Wallace WH, Hudson MM. Long-term follow-up of pediatric cancer survivors: education, surveillance, and screening. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 2006;46:149–58. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mullan F. Seasons of survival: reflections of a physician with cancer. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:270–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198507253130421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hudson MM. A model for care across the cancer continuum. Cancer. 2005;104:2638–42. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rowland JH, Bellizzi KM. Cancer survivors and survivorship research: a reflection on today’s successes and tomorrow’s challenges. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2008;22:181–200. v. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E, editors. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Translation. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Earle CC. Failing to plan is planning to fail: improving the quality of care with survivorship care plans. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5112–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.5284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ganz PA, Hahn EE. Implementing a survivorship care plan for patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:759–67. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.2851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horning SJ. Follow-up of adult cancer survivors: new paradigms for survivorship care planning. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2008;22:201–10. v. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ganz PA, Casillas J, Hahn EE. Ensuring quality care for cancer survivors: implementing the survivorship care plan. Sem Oncol Nurs. 2008;24:208–17. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Demark-Wahnefried W, Clipp EC, Morey MC, Pieper CF, Sloane R, Snyder DC, et al. Lifestyle intervention development study to improve physical function in older adults with cancer: outcomes from project LEAD. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3465–73. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.05.7224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Demark-Wahnefried W, Jones LW. Promoting a healthy lifestyle among cancer survivors. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2008;22:319–42. viii. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stein KD, Syrjala KL, Andrykowski MA. Physical and psychological long-term and late effects of cancer. Cancer. 2008;112:2577–92. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Short PF, Vargo MM. Responding to employment concerns of cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5138–41. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.6316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Short PF, Vasey JJ, Belue R. Work disability associated with cancer survivorship and other chronic conditions. Psycho-Oncol. 2008;17:91–7. doi: 10.1002/pon.1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oeffinger KC, McCabe MS. Models for delivering survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5117–24. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.0474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCabe MS, Jacobs L. Survivorship care: models and programs. Sem Oncol Nurs. 2008;24:202–7. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carey LA, Perou CM, Livasy CA, Dressler LG, Cowan D, Conway K, et al. Race, breast cancer subtypes, and survival in the carolina breast cancer study. JAMA. 2006;295:2492–502. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.21.2492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chlebowski RT, Chen Z, Anderson GL, Rohan T, Aragaki A, Lane D, et al. Ethnicity and breast cancer: factors influencing differences in incidence and outcome. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:439–48. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Owen JE, Goldstein MS, Lee JH, Breen N, Rowland JH. Use of health-related and cancer-specific support groups among adult cancer survivors. Cancer. 2007;109:2580–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ell K, Sanchez K, Vourlekis B, Lee P-J, Dwight-Johnson M, Lagomasino I, et al. Depression, correlates of depression, and receipt of depression care among low-income women with breast or gynecologic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3052–60. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McInnes DK, Cleary PD, Stein KD, Ding L, Mehta CC, Ayanian JZ, et al. Perceptions of cancer-related information among cancer survivors: a report from the american cancer society’s studies of cancer survivors. Cancer. 2008;113:1471–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shapiro C. Comparing cancer survivors of higher and lower socioeconomic status, Ohio Sate University Medical Center. 2008 unpublished data. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuhn TS. The structure of scientific revolutions. 3. 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hall JM, Lee MK, Newman B, Morrow JE, Anderson LA, Huey B, et al. Linkage of early-onset familial breast cancer to chromosome 17q21. Science. 1990;250:1684–9. doi: 10.1126/science.2270482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lerman C, Croyle RT. Genetic testing for cancer predisposition: behavioral science issues. J Natl Cancer Inst Monographs. 1995;17:63–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lerman C, Narod S, Schulman K, Hughes C, Gomez-Caminero A, Bonney G, et al. BRCA1 testing in families with hereditary breast-ovarian cancer. A prospective study of patient decision making and outcomes. JAMA. 1996;275:1885–92. doi: 10.1001/jama.275.24.1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.American Society of Clinical Oncology Policy Statement Update. Genetic testing for cancer susceptibility. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2397–406. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.03.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nelson HD, Huffman LH, Fu R, Harris EL. Genetic risk assessment and brca mutation testing for breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility: systematic evidence review for the U.S. preventive services task force. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:362–79. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-5-200509060-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brunsvold AN, Wung SF, Merkle CJ. BRCA1 genetic mutation and its link to ovarian cancer: implications for advanced practice nurses. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2005;17:518–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2005.00091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bosserman L, Gruber S, Muto L, Jeter J. Integrating genetic risk assessment into practice. J Oncol Pract. 2008;4:214–9. doi: 10.1200/JOP.0853501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]