Abstract

Background:

Prior studies have shown that, compared to patients with a low level of interpersonal continuity of care, patients with a high level of continuity of care have a lower likelihood of hospital admission and emergency department visits, and a higher likelihood of patient satisfaction. We sought to determine whether higher levels of continuity of care are associated with medication persistence and compliance among new users of oral antidiabetic treatment.

Methods:

We conducted a medicoadministrative cohort study of new users of oral antidiabetics aged 18 years or more among people covered by the Quebec public drug plan. We excluded people with fewer than 730 days of treatment and those who had been in hospital for 275 days or more in the first or second year after initiation of antidiabetic treatment. We categorized continuity of care observed in the first year after treatment initiation as low, intermediate or high. The association between continuity of care and medication persistence and compliance was assessed using generalized linear models.

Results:

In this cohort of 60 924 new users of oral antidiabetic treatment, compared to patients with a high level of continuity of care, those with an intermediate and a low level of continuity of care were less likely to be persistent (adjusted prevalence ratio 0.97 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.96-0.98] and 0.96 [95% CI 0.95-0.97], respectively) and compliant (adjusted prevalence ratio 0.98 [95% CI 0.97-0.99] and 0.95 [0.94-0.97], respectively) with their antidiabetic treatment.

Interpretation:

A higher level of interpersonal continuity of care was associated with a higher likelihood of drug persistence and compliance. Since the strength of this association was weak, further research is required to determine whether continuity of care plays a role in medication adherence.

Interpersonal continuity of care refers to the ongoing relationship between a patient and an individual physician.1 There is good evidence from a systematic review that a high level of interpersonal continuity of care is associated with decreased hospital admissions and emergency department visits, and improved patient satisfaction.2 To what extent a high level of continuity of care is associated with a higher likelihood of medication adherence is less clear.2 Medication adherence consists of 2 main constructs: persistence (consistently refilling prescriptions for the prescribed length of time) and compliance (taking the drug in accordance with the prescribed dosage and schedule).3 To our knowledge, the relation between interpersonal continuity of care and medication adherence has been assessed in 6 studies.4-9 In 4 of these studies,4,7-9 a positive relation was observed. For example, a high level of continuity of care was associated with higher persistence with statins8 and higher compliance with treatment with orally administered antidiabetics,7 statins9 and drugs used in heart failure.4 However, 5 of these studies4,6-9 were limited by the fact that their design was cross-sectional. Therefore, the temporal relation between continuity of care and medication adherence could not be established.

Patient adherence to oral antidiabetic treatment is not optimal. For example, in a study conducted in Quebec, 79% of patients were persistent with oral antidiabetic treatment 1 year after initiation of therapy; of the 79%, only 78% were compliant (obtained drug supplies for at least 80% of days during the year).10

We conducted a study aiming to assess the association between continuity of care and each of the 2 main constructs of medication adherence (persistence with treatment and compliance with treatment among those persistent) among new users of orally administered antidiabetics.

Methods

Study design and data sources

We conducted a cohort study among patients insured by the Quebec public drug plan using medicoadministrative data from the Quebec Health Insurance Board and the Quebec registry of hospital admissions. The Quebec drug plan covers prescribed drugs for all permanent residents of the province aged 65 or more, social assistance recipients and those without a private drug insurance group plan. The databases contain information on individual characteristics (age, sex, guaranteed income supplement status and public drug plan eligibility), use of outpatient medical services (date, primary diagnosis and identification number of the physician consulted), drugs claimed (drug identification, date, quantity supplied, number of days' worth of drug supply and pharmacy identification number) and hospital admissions (dates and primary and secondary diagnoses).

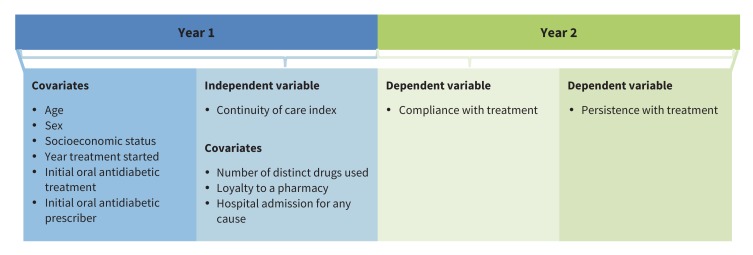

We measured continuity of care during the first year of treatment and assessed medication adherence in the second year of treatment (Figure 1). In this way, we were able to assess the temporal relation between the 2 variables.2

Figure 1.

Study design and timeline for measurement of variables.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included patients aged 18 years or more who were newly dispensed an orally administered antidiabetic (metformin, sulfonylurea or nonsulfonylurea insulin secretagogue, thiazolidinedione or α-glucosidase inhibitor) between Jan. 1, 2000 and Dec. 31, 2006. To identify new users, we excluded patients who had not been continuously eligible for the public drug plan and who had no antidiabetic drug claim throughout the entire year before the first antidiabetic drug claim registered on or after Jan. 1, 2000. We also excluded patients for whom we did not have a follow-up period of at least 730 days; this was done to allow the measurement of continuity of care in the first year of treatment and medication adherence in the second year of treatment. To obtain a measurement of outpatient drug compliance over a period of at least 90 days, we excluded patients who had been in hospital for 275 days or more in the first or second year after treatment was started. Finally, to ensure a valid measurement of continuity of care, we excluded patients who had fewer than 3 or more than 50 outpatient visits in the first year after initiation of treatment.11

Continuity of care measure

We measured continuity of care using an index that measures the extent to which ambulatory visits for a specific patient are dispersed among different physicians.11 The index takes into account the contribution of each physician, irrespective of specialty, in the continuity of the patient's care. The score ranges from 0 (lowest level of continuity of care) to 1 (highest level of continuity of care). The highest level means that the patient's visits are concentrated among only 1 physician.11 Since index scores have no validated thresholds, we categorized continuity of care into 3 categories: low (≤ 0.06), intermediate (0.07-0.24) and high (0.25-1.00).5,7,12

Outcome measures

Patients were considered persistent with their treatment if they had any orally administered antidiabetic or insulin available 730 days after treatment was started. We estimated this based on the number of days' worth of medication supplied at the most recent dispensing before the second anniversary date (derived directly from the Quebec drug plan database) plus, for oral antidiabetics, a permissible gap of 0.5 times the number of days' worth of supply. We defined the number of days' worth of supply beforehand as 90 for all insulin claims.10,13 Patients admitted to hospital on day 730 were considered persistent with treatment if they had filled any prescription for an oral antidiabetic or insulin during the period before their most recent hospital admission, along the same lines as described above.

We measured compliance with antidiabetic therapy among patients who persisted with their treatment as the proportion of days covered by the supply,14 calculated as the total number of days covered by either an orally administered antidiabetic or insulin divided by 365. For orally administered antidiabetics, we derived the number of days' worth of supply as described for persistence with treatment. Because information on drugs taken in hospital is not recorded, we subtracted the number of days spent in hospital from both the numerator and the denominator. It has been shown that a proportion of days covered of less than 80% predicts subsequent hospital admission among patients with diabetes.15 Therefore, we considered patients with a proportion of days covered of 80% or more as compliant.

Covariates

Covariates were variables previously shown to be associated with persistence or compliance with antidiabetic treatment.10,16 Covariates included sociodemographic characteristics, variables pertaining to use of health care services, and variables related to the initial claim for an orally administered antidiabetic. Sociodemographic characteristics at initiation of antidiabetic treatment included age, sex (male/female) and socioeconomic status (no/partial/maximum guaranteed income supplement). We assessed variables pertaining to use of health care services in the first year after treatment was started; these included loyalty to a pharmacy (1, > 1 different pharmacies visited) and number of hospital admissions for any cause. In addition, we considered the number of distinct drugs claimed as a comorbidity indicator.17 Characteristics related to the initial claim for an orally administered antidiabetic included treatment type (metformin monotherapy; sulfonylurea monotherapy; monotherapy with another antidiabetic; bi-therapy with other antidiabetics; tri-, quadri- or pentatherapy with other antidiabetics), specialty of prescribing physician (general practitioner, endocrinologist or internist, other) and year (2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005 or 2006).

Statistical analysis

We conducted 2 generalized linear models with a log link and a Poisson working model.18 The first model assessed the association between the continuity of care index and medication persistence, and the second, the association between continuity of care and medication compliance among those persistent with treatment. In both models, potential confounders included age, sex, socioeconomic status, number of distinct drugs claimed, loyalty to a pharmacy, hospital admission for any cause, initial oral antidiabetic treatment type, year of treatment initiation and specialty of the prescriber of the initial oral antidiabetic treatment. We computed adjusted prevalence ratios with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We evaluated the models' goodness-of-fit using the Akaike information criterion method. The model was well fitted to the number of parameters introduced. We assessed multicollinearity using the procedure described by Belsley and colleagues.19 We tested the sensitivity of our results to the compliance threshold of proportion of days covered of 80% by repeating the analysis using 70% and 90% as cut-off points. Analyses were performed with the use of SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

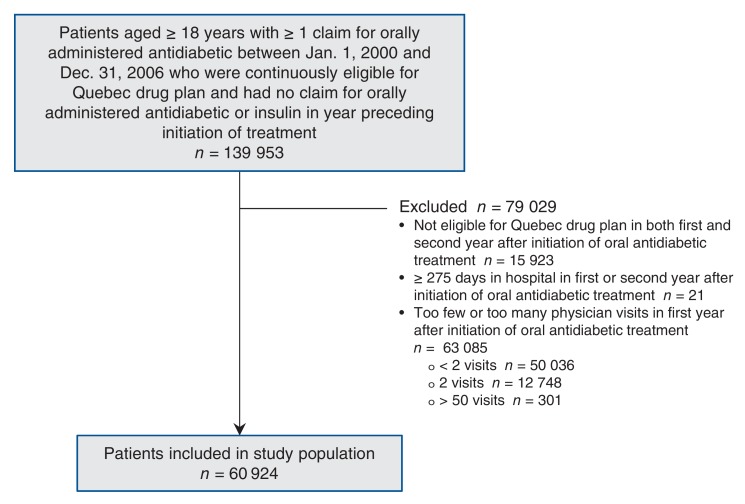

A total of 60 924 patients were included in the study population (Figure 2). Their characteristics are given in Table 1. The median score on the continuity of care index (first quartile to third quartile) was 0.14 (0.04-0.33).

Figure 2.

Selection of study population.

Table 1: Characteristics of patients at or in the year after initiation of oral antidiabetic treatment.

| Characteristic |

No. (%) of patients* (n = 60 924) |

|---|---|

| Sociodemographic | |

| Age, mean (median) (Q1-Q3), yr | 64.8 (67) (57-74) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 32 033 (52.6) |

| Male | 28 891 (47.4) |

| Socioeconomic status at initiation of treatment | |

| No guaranteed income supplement | 32 043 (52.6) |

| Partial guaranteed income supplement | 15 517 (25.5) |

| Maximum guaranteed income supplement or social assistance | 13 364 (21.9) |

| Use of health care services† | |

| Loyalty to a pharmacy | |

| Yes | 33 977 (55.8) |

| No | 26 947 (44.2) |

| Hospital admission for any cause | |

| Yes | 20 778 (34.1) |

| No | 40 146 (65.9) |

| No. of distinct drugs claimed, mean (median) (Q1-Q3) | 12.3 (11) (8-15) |

| Initial drug claim | |

| Initial drug treatment | |

| Metformin monotherapy | 47 002 (77.1) |

| Sulfonylurea monotherapy | 9685 (15.9) |

| Monotherapy with other orally administered antidiabetic | 774 (1.3) |

| Bi-therapy with other orally administered antidiabetics | 3435 (5.6) |

| Tri-, quadri- or pentatherapy with other orally administered antidiabetics | 28 (0.1) |

| Specialty of physician who prescribed initial therapy | |

| General practitioner | 49 814 (81.8) |

| Endocrinologist or internist | 7611 (12.5) |

| Other | 3405 (5.6) |

| Unknown | 94 (0.2) |

| Year treatment initiated | |

| 2000 | 7446 (12.2) |

| 2001 | 7337 (12.0) |

| 2002 | 7563 (12.4) |

| 2003 | 8177 (13.4) |

| 2004 | 9712 (15.9) |

| 2005 | 10 004 (16.4) |

| 2006 | 10 685 (17.5) |

Note: Q = quartile.

*Except where noted otherwise.

†Measured in the first year following initiation of treatment (including day of initiation and 365th day).

Of the 60 924 patients, 49 007 (80.4%) were persistent with their antidiabetic treatment 2 years after treatment initiation (Table 2). Compared to patients with a high level of continuity of care (n = 20 305), those with an intermediate (n = 19 898) and a low (n = 20 721) level of continuity of care were 3% and 4%, respectively, less likely to be persistent with their antidiabetic treatment (adjusted prevalence ratio 0.97 [95% CI 0.96-0.98] and 0.96 [95% CI 0.95-0.97], respectively) (Table 3). Of the 49 007 persistent patients, 39 246 (80.1%) complied with their antidiabetic treatment (Table 2). Compared to patients with a high level of continuity of care, those with an intermediate and a low level of continuity of care were 2% and 5%, respectively, less likely to be compliant (adjusted prevalence ratio 0.98 [95% CI 0.97-0.99] and 0.95 [95% CI 0.94-0.97], respectively) (Table 3). The association between continuity of care and compliance was not sensitive to change in the cut-off points for proportion of days covered (data not shown). When we analyzed the data including the 13 049 patients who were excluded because they had 2 or more than 50 physician visits, the results remained unchanged (data not shown).

Table 2: Persistence and compliance with oral antidiabetic treatment according to level of interpersonal continuity of care.

| Medication adherence construct* | Level of continuity of care; no. of patients (no. [%] with adherence construct) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| High | Intermediate | Low | |

| Persistence with antidiabetic treatment among the 60 924 study patients | 20 305 (16 820 [82.8]) |

19 898 (15 886 [79.8]) |

20 721 (16 301 [78.7]) |

| Compliance with antidiabetic treatment among the 49 007 patients who were persistent | 16 820 (13 592 [80.8]) |

15 886 (12 817 [80.7]) |

16 301 (12 837 [78.7]) |

*Measured in the second year after initiation of oral antidiabetic treatment.

Table 3: Adjusted prevalence ratios of persistence and compliance with antidiabetic treatment according to level of interpersonal continuity of care.

| Medication adherence | Level of continuity of care; adjusted prevalence ratio (95% CI)* | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| High | Intermediate | Low | |

| Persistence with antidiabetic treatment among the 60 924 study patients | 1.00 | 0.97 (0.96-0.98) | 0.96 (0.95-0.97) |

| Compliance with antidiabetic treatment among the 49 007 patients who were persistent | 1.00 | 0.98 (0.97-0.99) | 0.95 (0.94-0.97) |

Note: CI = confidence interval.

*Adjusted for age, sex and socioeconomic status at initiation of oral antidiabetic treatment, year of initiation of oral antidiabetic treatment, number of distinct drugs used, hospital admission for any cause and loyalty to a pharmacy in the year following initiation of oral antidiabetic treatment, initial oral antidiabetic treatment and specialty of the physician who prescribed the initial oral antidiabetic treatment.

Interpretation

One main result emerged from our study: as the level of interpersonal continuity of care decreased, patients were less likely to persist and comply with their antidiabetic drug treatment. However, given that the strength of the association was weak, the clinical value of this result may be limited.

Our finding is in line with results observed in 4 studies conducted among users of orally administered antidiabetics,7 statins8,9 and antihypertensive drugs.4 All of these studies but 14 were conducted with the use of health insurance data. For example, in the study conducted by Chen and colleagues7 based on health insurance data in Taiwan, compared to new users of oral antidiabetic treatment with a low index (≤ 0.22) of continuity of care, patients with a medium (0.23-0.43) and high (0.44-1.00) index were 1.8-fold and 3.4-fold, respectively, more likely to have a 1-year medication possession ratio of 80% or greater. In that study, associations were of a higher strength than those we observed, likely owing to the fact that Chen and colleagues used odds ratios as measures of association, whereas we used prevalence ratios. Odds ratios, as opposed to prevalence ratios, overestimate the risk ratio when the prevalence of the studied outcome in a study population is higher than 10%.18 This was the case in our study: the prevalence of persistence and compliance was around 80%.

In contrast, our results are different from those observed in 2 studies, 1 conducted among patients treated for hypertension5 and the other among patients treated for multiple chronic diseases.6 Kerse and colleagues6 did not observe an association between continuity of care and medication adherence. However, both of these outcomes were self-reported, as opposed to being measured based on physician visits and pharmacy dispensing data, as we did. Self-reported measures of adherence exhibit poor agreement with those based on pharmacy data.20 In addition, adherence was assessed with no attempt to distinguish persistence and compliance constructs from each other.6 Likewise, in a study based on Medicare data, Robles and Anderson5 found no association between continuity of care and compliance with antihypertensive treatment, as measured by the proportion of days covered during 1 year of 80% or more.5 However, when patients who had been admitted to hospital or had had a cardiovascular event were excluded, a positive association was observed between higher levels of continuity of care and compliance.5

In a study on patients' preferences, patients stated that they believed that continuity of care improved their trust in their physician as well as their physician's ability to communicate health issues to them.21 Although further research is needed to confirm the link between these attributes and continuity of care, in prior studies, better physician communication skills22 and patients' trust in the provider23,24 were associated with self-reported medication adherence.

Limitations

Our study has limitations. First, we assumed that drugs claimed were all taken, and we made no distinction between mono- and polytherapy. As a result, we may have overestimated persistence and compliance, thus leading to nondifferential misclassification with an effect estimate biased toward the null. Second, the databases lacked information on psychosocial variables (e.g., patient's perception of risk of disease and benefits of the treatment) that are likely to influence persistence and compliance,25 overall level of health or burden of illness, and duration and severity of diabetes. Therefore, we were not able to adjust effect estimates for these potentially confounding variables. Third, to get a valid continuity of care measure, we had to exclude patients who had fewer than 3 physicians visits in the 1-year period during which continuity of care was assessed. It is unknown to what extent the excluded patients were less sick or did not have as good access to a physician as those included in the study. Moreover, we assessed continuity of care in the first year of treatment and persistence and compliance in the second year of treatment. Therefore, we cannot assume that the association we have observed between continuity of care and persistence and compliance would remain the same if those outcomes were assessed in subsequent years. Fourth, since Canadian guidelines recommend an interprofessional team approach to care for patients with newly diagnosed diabetes,26 the continuity of care index may not be the best measure as it does not take into consideration the contribution of other health care professionals in the continuity of the patient's care. In addition, we measured continuity of care using all ambulatory visits. The results may have been different if we had been able to measure continuity of care using only visits relevant to the management of diabetes. Finally, since our study was observational, care should be taken before concluding that the association we observed is causal.

Conclusion

Prior studies have shown that, compared to patients with a low level of interpersonal continuity of care, patients with a high level of continuity of care have a lower likelihood of hospital admission and emergency department visits, and a higher likelihood of patient satisfaction. Our results suggest that a high level of continuity of care may also be associated with a higher likelihood of persistence and compliance with antidiabetic treatment among newly treated patients; however, a clinical trial is needed to confirm causality. In addition, given that the observed association was weak, the clinical relevance of this result is unclear. Further research is needed using continuity of care measures that capture the contribution of clinicians from different health care professions.

Supplemental information

For reviewer comments and the original submission of this manuscript, please see www.cmajopen.ca/content/5/2/E359/suppl/DC1

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgement: The authors thank Eric Demers for his assistance in accessing the data and statistical analyses.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was funded by the Chair on Adherence to Treatments. The Chair was supported by the Laval University Foundation and through unrestricted grants from AstraZeneca Canada, Merck Canada, Sanofi Canada, Pfizer Canada and the Prends soin de toi program. Line Guénette holds a Clinical Research Scholar award from the Fonds de recherche du Québec - Santé (FRQS) in partnership with the Société québécoise d'hypertension artérielle. Sophie Lauzier holds a Research Scholar award from the FRQS in partnership with the Institut national d'excellence en santé et en services sociaux.

References

- 1.Saultz JW. Defining and measuring interpersonal continuity of care. Ann Fam Med. 2003;1:134–43. doi: 10.1370/afm.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Walraven C, Oake N, Jennings A, et al. The association between continuity of care and outcomes: a systematic and critical review. J Eval Clin Pract. 2010;16:947–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2009.01235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wahl C, Grégoire JP, Teo K, et al. Concordance, compliance and adherence in healthcare: closing gaps and improving outcomes. Healthc Q. 2005;8:65–70. doi: 10.12927/hcq..16941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uijen AA, Bosch M, van den Bosch WJ, et al. Heart failure patients' experiences with continuity of care and its relation to medication adherence: a cross-sectional study. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13:86. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-13-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robles S, Anderson GF. Continuity of care and its effect on prescription drug use among Medicare beneficiaries with hypertension. Med Care. 2011;49:516–21. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31820fb10c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kerse N, Buetow S, Mainous AG, et al. Physician-patient relationship and medication compliance: a primary care investigation. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2:455–61. doi: 10.1370/afm.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen CC, Tseng CH, Cheng SH. Continuity of care, medication adherence, and health care outcomes among patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes: a longitudinal analysis. Med Care. 2013;51:231–7. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31827da5b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brookhart MA, Patrick AR, Schneeweiss S, et al. Physician follow-up and provider continuity are associated with long-term medication adherence: a study of the dynamics of statin use. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:847–52. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.8.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benner JS, Tierce JC, Ballantyne CM, et al. Follow-up lipid tests and physician visits are associated with improved adherence to statin therapy. Pharmacoeconomics. 2004;22:13–23. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200422003-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guénette L, Moisan J, Breton MC, et al. Difficulty adhering to antidiabetic treatment: factors associated with persistence and compliance. Diabetes Metab. 2013;39:250–7. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bice TW, Boxerman SB. A quantitative measure of continuity of care. Med Care. 1977;15:347–9. doi: 10.1097/00005650-197704000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chu HY, Chen CC, Cheng SH. Continuity of care, potentially inappropriate medication, and health care outcomes among the elderly: evidence from a longitudinal analysis in Taiwan. Med Care. 2012;50:1002–9. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31826c870f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bonafede MM, Kalsekar A, Pawaskar M, et al. A retrospective database analysis of insulin use patterns in insulin-naive patients with type 2 diabetes initiating basal insulin or mixtures. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2010;4:147–56. doi: 10.2147/ppa.s10467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choudhry NK, Shrank WH, Levin RL, et al. Measuring concurrent adherence to multiple related medications. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15:457–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karve S, Cleves MA, Helm M, et al. Good and poor adherence: optimal cut-point for adherence measures using administrative claims data. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25:2303–10. doi: 10.1185/03007990903126833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dossa AR, Grégoire JP, Lauzier S, et al. Association between loyalty to community pharmacy and medication persistence and compliance, and the use of guidelines-recommended drugs in type 2 diabetes: a cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e1082. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schneeweiss S, Seeger JD, Maclure M, et al. Performance of comorbidity scores to control for confounding in epidemiologic studies using claims data. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154:854–64. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.9.854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lumley T, Kronmal R, Ma S. Relative risks regression in medical research: models, contrasts, estimators and algorithms. UW Biostatistics Working Paper Series, University of Washington Paper 293. 2006. [accessed 2013 Sept. 15]. Available http://biostats.bepress.com/uwbiostat/paper293.

- 19.Belsley DA, Kuh E, Welsch RE. Regression diagnostics: identifying influential data and sources of collinearity. New York: John Wiley and Sons. 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guénette L, Moisan J, Préville M, et al. Measures of adherence based on self-report exhibited poor agreement with those based on pharmacy records. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:924–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pandhi N, Saultz JW. Patients' perceptions of interpersonal continuity of care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2006;19:390–7. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.19.4.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baumann M, Baumann C, Le Bihan E, et al. How patients perceive the therapeutic communications skills of their general practitioners, and how that perception affects adherence: use of the TCom-skill GP scale in a specific geographical area. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:244. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cuffee YL, Hargraves JL, Rosal M, et al. Reported racial discrimination, trust in physicians, and medication adherence among inner-city African Americans with hypertension. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:e55–62. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berry LL, Parish JT, Janakiraman R, et al. Patients' commitment to their primary physician and why it matters. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:6–13. doi: 10.1370/afm.757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zeber JE, Manias E, Williams AF, et al. ISPOR Medication Adherence Good Research Practices Working Group. A systematic literature review of psychosocial and behavioral factors associated with initial medication adherence: a report of the ISPOR Medication Adherence & Persistence Special Interest Group. Value Health. 2013;16:891–900. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2013.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Canadian Diabetes Association Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Committee. Canadian Diabetes Association 2013 Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Diabetes in Canada. Can J Diabetes. 2013;37:S1–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2013.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.