Abstract

Objectives

American Indian girls have higher teen pregnancy rates than the national rate. Intervention studies that utilize the Theory of Reasoned Action have found that changing attitudes and subjective norms often leads to subsequent change in a variety of health behaviors in young adults. The current study goal is to better understand sexual decision-making among American Indian youth using the Theory of Reasoned Action model and to introduce ways to utilize attitudes and subjective norms to modify risky behaviors.

Methods

The project collected qualitative data at a reservation site and an urban site through 16 focus groups with American Indian young people aged 16–24.

Results

Attitudes towards, perceived impact of, and perception of how others felt about teen pregnancy vary between American Indian parents and non-parents. Particularly, young American Indian parents felt more negatively about teen pregnancy. Participants also perceived a larger impact on female than male teen parents.

Conclusions

There are differences between American Indian parents and non-parents regarding attitudes towards, the perceived impact of, and how they perceived others felt about teen pregnancy. Teen pregnancy prevention programs for American Indian youth should include youth parents in curriculum creation and curriculum that addresses normative beliefs about teen pregnancy and provides education on the ramifications of teen pregnancy to change attitudes.

Keywords: teen pregnancy, American Indians, sexual health, Theory of Reasoned Action, youth

Introduction

The negative impact of teen pregnancy on the health and economic wellness of teen mothers and their children are vast (Coley & Aronson, 2013; Meade, Kershaw, & Ickovics, 2008; Perper, Peterson, & Manlove, 2010). Fortunately, teenage birth rates are at a historic low, and rates of teen pregnancy have generally been decreasing (Hamilton, Hoyert, Martin, Strobino, & Guyer, 2013; Martin et al., 2012), likely due to prevention efforts and more affordable and accessible contraception options. However, this is not the case for every subpopulation of teens. Specifically, American Indian and Alaska Native teens had the lowest decrease in pregnancy amongst females aged 15–19 in 2012 (Martin, Hamilton, Osterman, Curtin, & Mathews, 2013), and over one-fifth (21%) of American Indian/Alaska Native girls will become a mother compared to 16% nationally (The National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy, 2009).

American Indian/Alaska Native teen pregnancy occurs in an increasingly complex context. Evidence suggests that, when compared to other groups, American Indian/Alaska Native youth initiate sex at earlier ages (de Ravello, Everett Jones, Tulloch, Taylor, & Doshi, 2014). A study of Great Lakes American Indians found that almost 70% of 16 to 18 year olds reported engagement in sexual intercourse (Hellerstedt, Peterson-Hickey, Rhodes, & Garwick, 2006), compared to 30.0% of 15 to 17 year olds and 70.6% of 18 to 19 year olds nationally (Gavin et al., 2009). The literature also shows that American Indian/Alaska Native youth may participate in risky sexual behavior; one national survey found that 38% of American Indian/Alaska Natives ages 15–24 had unprotected sex at first intercourse (Rutman, Taualii, Ned, & Tetrick, 2012). Teen pregnancy and risky sexual behaviors among American Indian/Alaska Native youth have been linked to many risk factors including high rates of poverty (Misra, Matte, & Lewis, 2014) and substance use (de Ravello et al., 2014), physical or sexual abuse (Rutman et al., 2012), and restricted or no access to contraception (Richards & Mousseau, 2012). For many American Indian/Alaska Native female youth, having a child may provide an escape from limited opportunities in higher education and stressful home environments (Hanson, McMahon, Griese, & Kenyon, 2014; Sipsma, Ickovics, Lewis, Ethier, & Kershaw, 2011), and teen pregnancy is not always viewed as negative, as the interruption to the teens’ lives may be perceived as minimal (Kaufman et al., 2007). Confounding this is high incarceration rates and low high school completion rates for many American Indian communities (Greenfeld & Smith, 1999; White House, 2014). These attitudes and risk factors add to the complexity of preventing teen pregnancy in this population.

Theory of Reasoned Action

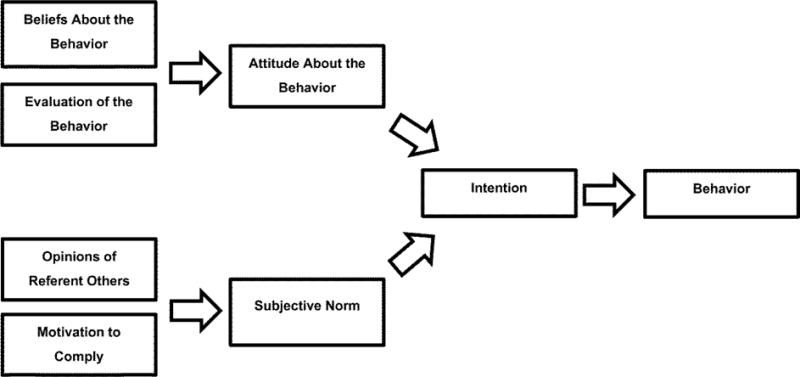

Different models have been utilized regarding teen sexual behavior and pregnancy; however, when compared to other theories, the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) was the only theory that accounted for a significant amount of variance in unprotected sex in teenage mothers (Koniak-Griffin, Lesser, Uman, & Nyamathi, 2003) and was a better predictor of teenage girls age at first intercourse and consistency of condom use (Koniak-Griffin et al., 2003; Tremblay & Frigon, 2004). The TRA, which assumes the best predictor of behavior is behavioral intention, is guided by two major constructs. Attitudes are the beliefs and feelings about certain behaviors and the values (positive or negative) attached to the outcome of that behavior (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975; Montano & Kasprzyk, 2008). Subjective norms are the perceptions of social norms, including a belief about whether referent individuals approve or disapprove of a behavior and the individual’s motivation to comply with these normative beliefs (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975; Montano & Kasprzyk, 2008). See Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Theory of Reasoned Action (Montano & Kasprzyk, 2008)

Intervention studies that utilize the TRA have found that changing attitudes and subjective norms often leads to subsequent change in a variety of health behaviors in young adults, including use of contraception (Albarracin, Johnson, Fishbein, & Muellerleile, 2001; Morrison, Baker, & Gillmore, 2000), making it an important tool in addressing behaviors related to teen pregnancy. Overall, both attitudes and subjective norms show consistent relationships to intentions to use birth control and sexual behavior in teens (Broaddus, Schmiege, & Bryan, 2011; Gillmore et al., 2002). For example, one study found that attitudes and subjective norms for condom use were significantly related to the intention to use condoms and, in turn, the intention to use condoms was predictive of eventual condom use (Morrison et al., 2000).

To our knowledge, there are no studies utilizing the TRA in research regarding sexual behavior and pregnancy with American Indian teens. There is a need for such research given the disproportionate rates of sexual activity and contraception use among AI adolescents. The current study, part of a larger project to develop a community-based teen pregnancy prevention program for Northern Plains American Indian youth, reveals the role that the TRA can play in understanding sexual decision-making and teen pregnancy among American Indian youth. These findings will further inform teen pregnancy prevention efforts and add to the knowledge base on teen pregnancy specific to Northern Plains American Indian youth.

Method

Qualitative research methods were chosen for this study to capture Northern Plains American Indian’s unique points of view (Patton, 2002). Data collection occurred at two sites: one was a reservation site where almost all participants indicated one tribal affiliation; and the other was a small, urban site with various tribal affiliations. Data were gathered from focus groups with American Indian young people aged 16 to 24 years old, with groups segmented by parental status (parents and non-parents) and sex (males and females). Prior to conducting this study, all study procedures were approved by institutional review boards and by the local tribe through a tribal resolution. Tribal anonymity is required; therefore the specific tribal community is not identified in this study.

The focus groups were facilitated by local community research associates who were trained in qualitative research methodology and conducting focus groups. The formulation of focus group questions were the result of collaborative efforts among study staff and community advisory boards consisting of local American Indian individuals. Focus group questions were identical for both sites. Measures focused on cultural influences, social norms, access to reproductive services, adolescent sexual risk behaviors, and contraceptive use. See Table 1 for a list of questions.

Table 1.

Examples of Qualitative Questions

| What do you think are some reasons your friends or people your age decide to have sex? |

| What do you think are some reasons your friends or people your age decide not to have sex? |

| How are the reasons regarding sex (deciding to or not to have sex) different? …. for girls and boys? Age differences? Family differences? Cultural differences? |

| What do you think are some reasons youth decide to use contraception (condoms, pill, etc) to prevent pregnancy? |

| What do you think are some reasons youth decide not to use contraception (condoms, pill, etc) to prevent pregnancy? |

| How are these reasons for both using and not using contraception different? …. for girls and boys? Age differences? Family differences? Cultural differences? |

| What reaction do youth your age have towards teen pregnancy? |

| ** (ONLY FOR PARENT GROUPS): Please describe how you think you have a unique perspective on any of the previous questions because you are a teen parent. What advice would you have for teens? |

Local community research associates recruited participants by means of flyers, community contacts, and word of mouth. Inclusion criteria included self-identification as AI and age (between 16 to 24 years old). The focus groups were conducted in private rooms at local community health buildings or libraries. Written consent or assent was obtained from all participants, and parental permission was obtained for participants younger than 18 years of age. Participants were offered a gift card for their participation in the focus group. The focus groups were tape-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Analysis

Transcripts were stored and analyzed using the NVivo 10 software program, and data were analyzed using a traditional content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). The codebook was developed by operationalizing coding definitions and coding decision rules through multiple coding manual revisions (MacQueen, McLellan, Kay, & Milstein, 1998). An important piece of the qualitative data analysis was the calculation of inter-rater reliability, where two coders separately coded a random selection of 300 lines from the transcripts using the final draft of the codebook (Lombard, Snyder-Duch, & Bracken, 2004). The Cohen’s kappa value was 0.62, “substantial” (0.61 to 0.80) when interpreted using the benchmarks set by Landis & Koch (1977). Additional validation techniques for the qualitative data were establishing through various means, including contingent validity through the use of diverse participant perspectives; descriptive validity through the use of verbatim responses; and interpretive validity through letting the themes of the study emerge directly from the data (McMahon, Hanson, Griese, & Kenyon, 2015).

For the purposes of this manuscript, the coder looked at quotes within four specific nodes: attitudes toward teen pregnancy, epidemiology of teen pregnancy, impact of teen pregnancy, and knowledge about teen pregnancy. The text under these four nodes was analyzed and subthemes were created to highlight specific statements on attitudes and subjective norms regarding teen pregnancy. Attitudes were defined as how American Indian youth felt about teen pregnancy (i.e., beliefs and overall evaluation of teen pregnancy). Subjective norms were defined as how American Indian youth felt that others viewed teen pregnancy (i.e., opinion of others and how those opinions impacted the teens). These activities were completed by a single coder (first author) with input from the project’s Co-Investigator (second author).

Results

There were 16 total focus groups with American Indian youth (n = 105), with 8 groups per site: at both sites, there were two focus groups with female parents, two with female non-parents, two with male parents, and two with male non-parents (n = 48 non-parents and n = 57 parents). See Table 2 for demographics. Note that two of our participants self-identified as White. It might have been they were of mixed ancestry but identified more as White. As race was self-identified, we did not check tribal enrollment and therefore our sample was not completely homogenous.

Table 2.

Demographic Characteristics of Study Sample

| Method | n | Age mean (range) | Gender b | Race c | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | AI/AN (alone) | AI/AN (multiple) | White (alone) | |||

| Focus Groups (16 total) | 105 | 20.3 (15–25) | 60 (57.1) | 44 (41.9) | 80 (76.2) | 22 (21.0) | 2 (0.2) |

| Non-parents | 48 | 18.7 (15–24) | 26 (54.2) | 22 (45.8) | 36 (75.0) | 9 (18.8) | 2 (4.2) |

| Parents a | 57 | 21.8 (17–25) | 34 (59.6) | 22 (38.6) | 44 (77.2) | 13 (22.8) | – |

Two female parents did not complete the survey.

One participant from the parent focus group identified as both male and female and gender is represented as missing.

One participant from the youth focus group did not report their race.

Attitudes toward Teen Pregnancy

Youth who were not parents were evenly split in their attitudes toward teen pregnancy. Some female youth who were not parents felt that having a baby was looked upon more favorably both personally, “a baby is always a blessing no matter what,” and to those around them, when a teen gets pregnant the reaction is, “excitement right away.” However, others felt that they, personally, would not want to become teen parents and would not see it in a positive light. One female youth (not a parent) stated, “I never want to go through that [teen pregnancy]” and a male youth who was not a parent explained, “[I] don’t want a kid, it’s too much work.” Youth who were parents were resoundingly more negative, with most agreeing that, “there are too many young kids having kids” causing parents “disappointment, because [the parents] know what [the teens] are in for.”

Overall, youth who were parents felt teen pregnancy was more undesirable when compared with responses from youth who were not parents. Teenage mothers, in particular, had negative attitudes about teen pregnancy, describing it as “sad,” “disappointing,” and “gross.” Upon learning of other teen pregnancies in their families, they recalled reacting with anger, disbelief, and unhappiness. As one teenage mother describes it, “My sister got pregnant. I was like, ‘What the heck were you thinking? Like, you should have at least waited a couple more years. It’s like you’re obviously not ready to be … a teen parent.’”

Additionally, youth who were not parents were more likely to put a condition on how they felt about teen pregnancy. Generally, they felt that a teen’s family, romantic, and monetary situation also played a role in their attitudes toward teen pregnancy. On the other hand, one teenage mother described, “if you have a supporting significant other and supporting family … it’s going to [be a] more positive [experience] …, but if you have a negative significant other and a negative family, it’s going to be [a] more negative [experience].”

Perceived Impact of Teenage Pregnancy

While youth who were not parents focused mainly on the fact that teenage pregnancy impedes higher education, “having a kid would stop a lot of people from going to college” and “having a child… as a teen… sets [you] off your goals.” Conversely, youth who were parents focused on the fun and school they missed out on. As one teenage mother explained, “I [had] a little party life, too, and I gave it all up because I knew I had to take care of them [children].” Another teenage mother reflected, “I wanted to travel, go to the beach on spring break, but I can’t do any of that now.” “I wish… I stayed in high school… That was my only chance, and I blew it,” was how another teenage mother parent felt and, “now I have to start late, I’m going to go to college, but I have to start late now” was something another experienced. Youth who were parents also concentrated on the overwhelming responsibility becoming a teenage parent brings. For example, one teenage mother explained,

“Whenever [sic] I had her, I was freaking out… Who is going to help me, like [my] mom [might] take her… but I couldn’t do that. She was mine, and I had to take care of her. I learned the hard way through everything with her.”

Not every youth who was a parent felt negatively toward their teen pregnancy. Youth who were parents often spoke of the positive personal impact it had on them, most often how it, “helped [them] become a better person.” One teenage mother explained that teen pregnancy “helped me grow up a little bit and … go back to school… It helped me grow up, helped me get my life started.” Another said, “My son saved my life.” A third teenage mother attributed her strength to her kids.

In both groups, but especially youth who were parents, females more often spoke of the impact on their futures, while males more often spoke of the teen father’s roles and responsibilities after the baby was born. Teenage fathers felt the hardships of pregnancy were unevenly balanced, with the bulk of the responsibility falling on females, but argued that the teen father’s role is also challenging. Teenage fathers said, “It is a lot easier for the guy,” because, “everybody’s always … focusing on the girl all the time” though “That's a lot for the guy to be with the girl through the nine months that she’s carrying it” and “then you have to do all this, be responsible.” Young men who were not parents agreed with this sentiment, explaining that if they, “have a kid [they’ll] have to compromise,” “get a job,” and “pay child support.” Yet, when young men who were not parents were asked if getting a girl pregnant would make achieving their goals more difficult, the answer was a resounding “no.” However, one said he would “cancel [his goals] and… go and [sic] be next to her.”

Subjective Norms and Knowledge

Less information on subjective norms was given by focus study participants, potentially because of gaps in knowledge about the true impact of having a child at a young age. Contrary to some general attitudes about teen pregnancy, young parents believed that teens felt positively about teen pregnancy. A teenage mother reported that, in general, the youth they see are, “pretty happy, like they [youth] don’t fully understand what it means to get pregnant at a young age.” However, the perceptions of youth who were not teenage parents of how people in their lives felt were split between both positive and negative views. One female youth who was not a parent felt that when a teen gets pregnant, people, “judge them differently or talk down about their choices.” Conversely, another non-parent, female youth with a classmate that's pregnant felt that, “more people were excited about it than negative.”

Youth who were not parents, particularly female non-parents, felt that those around them placed blame on the teen mom rather than the teen father. One female youth who was not a parent felt that “people look down on the girl more than the guy,” another stated that, “if a girl gets pregnant young, they look at her as like maybe a whore.” Often this perceived blame was attributed to personality traits of the pregnant female, such as, “she is so irresponsible,” “she's a bad person,” or she “just wants to be that dramatic person.” No information similar to this was provided for boys. It was felt that teen father’s do not have the knowledge of the full responsibilities of being a teenage parent because less focus is placed on them in terms of blame or overall impact.

On the other hand, youth who were parents had more first-hand experiential knowledge about teenage pregnancy, and more often spoke about others’ views on the difficulties in completing high school as a result of teen pregnancy. They recounted what others told them their futures would turn out to be after becoming pregnant as a teen. One teenage mother recalled that, “They always told me, ‘Oh look, you’re not going to be able to do it [finish high school] because you got pregnant young.’”

Both female parents and non-parents spoke about others’ perceptions of teenage fathers and followed a similar line of thought: that teenage fathers leave. A female who was not a parent believed that, “guys feel less responsible if the girl gets pregnant… Guys would be fine with just walking away.” Likewise, a teenage mother felt that teen fathers don’t feel a need to care for or have a relationship with their children, even if the relationship with the child’s mother ends. She related that, “Ninety percent of the time, it doesn’t work out. You have a baby, and there he goes.”

Discussion

Utilizing focus groups with young American Indian participants, the goal of this study was to analyze American Indian parents and non-parents’ opinions about teen pregnancy in the context of the TRA model, by focusing on qualitative data nodes specific to attitudes, impact, and knowledge. While focus group questions were not written with any predetermined theory, the responses gathered were specifically analyzed using TRA constructs, specifically attitudes and subjective norms. There were more responses regarding personal attitudes toward teen pregnancy compared to subjective norms, which may be due to the wording of the questions or participants being more comfortable discussing their own attitudes toward teen pregnancy rather than speculating on the beliefs of others.

No systematic differences were seen between urban and reservation communities in regards to attitudes or perceived subjective norms toward teen pregnancy. As it has been suggested that urban American Indian/Alaska Native youth tend to be more assimilated than reservation American Indian/Alaska Native youth to mainstream culture (McMahon, Hanson, Griese, & Kenyon, 2015), it may be the case that cultural/ethnic identity does not play a role in this particular sample with respect to attitudes towards and perceived impact of teen pregnancy. Few articles examine urban versus reservation American Indian/Alaska Natives and fewer still look at cultural identity and youth risky sexual behaviors. However, our finding agrees with and updates previous quantitative literature in an urban area (Marsiglia, Nieri, & Stiffman, 2006) and reservation (Chewning et al., 2001) that showed American Indian cultural-connectedness and family involvement in culture did not have any associations with youth risky sexual behaviors.

While there were no systematic differences seen between urban and reservation communities, there were a variety of differences seen between young parents and non-parents in regard to attitudes toward teen pregnancy and how they perceived others felt about teen pregnancy. While non-parents were evenly split in their attitudes toward teen pregnancy, some saying they could “start a little family” and others explaining that they “never want to go through” teen pregnancy, American Indian parents had more realistic views of teen pregnancy and cautioned against the romantic views that some teens express about having a baby. On the other hand, while many American Indian parents felt negatively about teen pregnancy in the abstract, when it came to their own experiences many felt becoming a parent ended up having a positive impact on their life, including “[becoming] a better person.” This is not unique to American Indian as other qualitative studies have found that mothers have reported having a child has motivated them to stay in school and work towards a career (Edin & Kefalas, 2005; Seamark & Lings, 2004), although studies find that teen pregnancy has negative effects on earnings and school completion for most women (Diaz & Fiel, 2016).

Differences in how teen pregnancy impacts female and male youth were also a central theme when participants discussed attitudes and perceived subjective norms of teenage pregnancy. American Indian females who were not parents perceived that young pregnant women were judged more harshly than the teen father. This is possibly because mothers have to physically carry the child, and also because society often judges women more harshly surrounding the topic of sexuality (Carpenter, 2005). This finding is significant as it is in contrast with findings in a majority white and black population which found that teen mothers were perceived more positively than teen fathers (Weed & Nicholson, 2015). The disparity in judgment emphasizes the need for additional support during pregnancy, especially for teen mothers, as negative stigmatization can interfere with both mother and child well-being (SmithBattle, 2013; Somerville, 2013).

In addition, while the young men in our sample focused on their role as a provider and indicated that it was a role they were fulfilling or would fulfill, American Indian females felt that most young fathers would leave after the birth of their child, if not during pregnancy. The negative judgments that follow teen mothers also follow teen fathers with previous research concurring with our findings and concluding that teen fathers are often portrayed as absent (Johansson & Hammarén, 2014). While it is true that only half of teenage fathers live with the mother and child compared to nearly ninety percent of adult fathers, researchers have found that higher proportions of teen fathers who live with the mothers of their children were American Indian (Mollborn & Lovegrove, 2011). Additionally, not only do both teenage and adult fathers report similar levels of involvement in playing with and caring for their children (Mollborn & Lovegrove, 2011), but teenage fathers often desire to be a better father or role model than their own (Trivedi, Brooks, Bunn, & Graham, 2009) and present themselves as caring fathers (Johansson & Hammarén, 2014). This widespread misconception of the deadbeat teenage father can be harmful not only to the teenage mother and child, but to the father as well as they navigate parenthood for the first time.

Limitations

Participants were not necessarily representative of all American Indian communities because the focus groups were with Northern Plains American Indians. Therefore, these findings may not be applicable to other populations of American Indians and are not generalizable to all Northern Plains American Indians.

Conclusion

The current study, part of a larger project to develop a community-based teen pregnancy prevention program for Northern Plains American Indian youth, reveals the role that the TRA can play in understanding sexual decision-making and teen pregnancy among American Indian youth residing in these communities. While young parents were well-versed in the multitude of impacts teen parenthood brings, non-parents were less so, suggesting current programming is not providing enough information. There is first and foremost a need to increase knowledge about the realities of teen pregnancies. A teen pregnancy prevention program for American Indian youth should include curriculum that provides education on the ramifications of teen pregnancy, as well as education on increasing contraception use for those who are sexually active. Beliefs about sexual activity and birth control and evaluation of behaviors surrounding these can change attitudes, which leads to intention and actual behavior modifications.

Also, as noted in the TRA model, the opinions of referents can affect subjective norms, and in combination with changes in attitude, behavior will ideally thus be impacted. Since these young American Indian parents held stronger attitudes against teen pregnancy, teen pregnancy prevention efforts may want to involve the youth parent population when planning programming. This population has a unique point of view and since they are the same or close in age they may be able to connect with teens in ways a traditional educator is not. Utilizing American Indian teen parents in a teen pregnancy prevention program can ultimately change both knowledge and subjective norms, which will ideally lead to actual behavior change.

Finally and perhaps most importantly, previous work from our team highlight the role that family, community, and cultural connectedness can play within teen pregnancy prevention (Griese, Kenyon, & McMahon, 2016). Therefore, American Indian teen pregnancy prevention programs must examine the overall context of the community — for example, historical experiences and cultural connectedness (Rink et al., 2012; Rushing & Stephens, 2012; Rutman et al., 2012) — and also be responsive to the specific priorities of tribal communities and the teens themselves (Harris & Allgood, 2009).

Significance.

The Theory of Reasoned Action has not been utilized with this population (American Indian youth) and topic (sexual behavior and teen pregnancy) before, making the findings distinctive from previous research. Ultimately these findings not only increase knowledge on teen pregnancy in Northern Plains American Indian youth, but can be used to further inform teen pregnancy prevention efforts through addressing youths’ relevant attitudes and subjective norms of teen pregnancy in their community.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Award Number P20MD001631 -06 from the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities or the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Special thanks to Dr. Renee Seiving, Melissa Huff, Char Green, Jen Prasek, Dr. Paul Thompson, Noelani Villa, Donna Keeler, Reggan LaBore, Kathy White, Cassandra Crazy Thunder, and Tonya Belile for their contributions to this project.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Elizabeth A. Dippel, Research Associate, Center for Health Outcomes and Prevention Research, Sanford Research.

Jessica D. Hanson, Associate Scientist, Center for Health Outcomes and Prevention Research, Sanford Research, 2301 E. 60th St North, Sioux Falls, SD 57104, Phone: 605-312-6209, Fax: 605-312-6301.

Tracey R. McMahon, Senior Research Associate, Center for Health Outcomes and Prevention Research, Sanford Research.

Emily R. Griese, Assistant Scientist, Center for Health Outcomes and Prevention Research, Sanford Research.

DenYelle B. Kenyon, Director and Scientist, Center for Health Outcomes and Prevention Research, Sanford Research.

References

- Albarracin D, Johnson BT, Fishbein M, Muellerleile PA. Theories of reasoned action and planned behavior as models of condom use: a meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127(1):142–161. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.1.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broaddus MR, Schmiege SJ, Bryan AD. An expanded model of the temporal stability of condom use intentions: gender-specific predictors among high-risk adolescents. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2011;42(1):99–110. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9266-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter LM. Virginity lost: An intimate portrait of first sexual experiences. New York: New York University; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Chewning B, Douglas J, Kokotailo PK, LaCourt J, Clair DS, Wilson D. Protective factors associated with American Indian adolescents’ safer sexual patterns. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2001;5(4):273–280. doi: 10.1023/a:1013037007288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coley SL, Aronson RE. Exploring birth outcome disparities and the impact of prenatal care utilization among North Carolina teen mothers. Women’s Health Issues. 2013;23(5):e287–294. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Ravello L, Everett Jones S, Tulloch S, Taylor M, Doshi S. Substance use and sexual risk behaviors among American Indian and Alaska Native high school students. Journal of School Health. 2014;84(1):25–32. doi: 10.1111/josh.12114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz CJ, Fiel JE. The effect(s) of teen pregnancy: reconciling theory, methods, and findings. Demography. 2016;53(1):85–116. doi: 10.1007/s13524-015-0446-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edin K, Kefalas M. Promises I can keep: Why poor women put motherhood before marriage. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Gavin L, MacKay AP, Brown K, Harrier S, Ventura SJ, Kann L, Ryan G. Sexual and reproductive health of persons aged 10–24 years - United States, 2002–2007. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report: Surveillance Summaries. 2009;58(6):1–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillmore M, Archibald ME, Morrison DM, Wilsdon A, Wells EA, Hoppe MJ, Murowchick E. Teen sexual behavior: applicability of the theory of reasoned action. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64(4):885–897. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfeld LA, Smith SK. American Indians and crime. 1999 Retrieved from https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/aic.pdf.

- Griese ER, Kenyon DB, McMahon TR. Identifying sexual health protective factors among Northern Plains American Indian youth: An ecological approach utilizing multiple perspectives. American Indian & Alaska Native Mental Health Research: The Journal of the National Center. 2016;23(4):16–43. doi: 10.5820/aian.2304.2016.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton BE, Hoyert DL, Martin JA, Strobino DM, Guyer B. Annual summary of vital statistics: 2010–2011. Pediatrics. 2013;131(3):548–558. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-3769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson JD, McMahon TR, Griese ER, Kenyon DB. Understanding gender roles in teen pregnancy prevention among American Indian youth. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2014;38(6):807–815. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.38.6.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris MB, Allgood JG. Adolescent pregnancy prevention: Choosing an effective program that fits. Children & Youth Services Review. 2009;31(12):1314–1320. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2009.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hellerstedt WL, Peterson-Hickey M, Rhodes KL, Garwick A. Environmental, social, and personal correlates of having ever had sexual intercourse among American Indian youths. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(12):2228–2234. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.053454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh H, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson T, Hammarén N. ‘Imagine, just 16 years old and already a dad!’ The construction of young fatherhood on the Internet. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth. 2014;19(3):366–381. doi: 10.1080/02673843.2012.747972. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman CE, Desserich J, Crow CKB, Rock BH, Keane E, Mitchell CM. Culture, context, and sexual risk among Northern Plains American Indian youth. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;64(10):2152–2164. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koniak-Griffin D, Lesser J, Uman G, Nyamathi A. Teen pregnancy, motherhood, and unprotected sexual activity. Research in Nursing & Health. 2003;26(1):4–19. doi: 10.1002/nur.10062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombard M, Snyder-Duch J, Bracken CC. Practical resources for assessing and reporting intercoder reliability in content analysis research projects. 2004 Retrieved from http://matthewlombard.com/reliability/

- MacQueen KM, McLellan E, Kay K, Milstein B. Codebook development for team-based qualitative analysis. Cultural Anthropology Methods. 1998;10(2):31–36. Retrieved from http://rds.epi-ucsf.org/ticr/syllabus/courses/47/2013/02/13/Lecture/readings/CDC%20Guidelines%20for%20Codebooks.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Nieri T, Stiffman AR. HIV/AIDS protective factors among urban American Indian youths. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2006;17(4):745–758. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2006.0128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK, Curtin SC, Mathews TJ. Births: preliminary data for 2012. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2013;62(3):1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ, Osterman MJK, Wilson EC, Mathews TJ. Births: final data for 2010. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2012;61(1):1–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon TR, Hanson JD, Griese ER, Kenyon DB. Teen pregnancy prevention program recommendations from urban and reservation Northern Plains American Indian community members. American Jouranl of Sexuality Education. 2015;10(3):218–241. doi: 10.1080/15546128.2015.1049314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meade CS, Kershaw TS, Ickovics JR. The intergenerational cycle of teenage motherhood: an ecological approach. Health Psychology. 2008;27(4):419–429. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.4.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misra K, Matte A, Lewis AE. Understanding teen mothers: A zip code analysis. American Economist. 2014;59(1):52–69. [Google Scholar]

- Mollborn S, Lovegrove PJ. How teenage fathers matter for children: evidence from the ECLS-B. Journal of Family Issues. 2011;32(1):3–30. doi: 10.1177/0192513x10370110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montano DE, Kasprzyk D. Theory of Reasoned Action, Theory of Planned Behavior, and the Integrated Behavioral Model. In: Glanz K, Reimer BK, Lewis FM, editors. Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice. 4th. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2008. pp. 67–96. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison DM, Baker SA, Gillmore M. Using the Theory of Reasoned Action to predict condom use among high-risk heterosexual teens. In: Norman P, Abraham C, Conner M, editors. Understanding and changing health behaviour: From health beliefs to self-regulation. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Harwood Academic Publishers; 2000. pp. 27–49. [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ. Two decades of developments in qualitative inquiry: a personal, experiential perspective. Qualitative Social Work. 2002;1(3):261–283. doi: 10.1177/1473325002001003636. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perper K, Peterson K, Manlove J. Diploma attainment among teen mothers. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.childtrends.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/01/child_trends-2010_01_22_FS_diplomaattainment.pdf.

- Richards J, Mousseau A. Community-based participatory research to improve preconception health among northern plains American Indian adolescent women. American Indian & Alaska Native Mental Health Research: The Journal of the National Center. 2012;19(1):154–185. doi: 10.5820/aian.1901.2012.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rink E, FourStar K, Medicine Elk J, Dick R, Jewett L, Gesink D. Pregnancy prevention among American Indian men ages 18 to 24: The role of mental health and intention to use birth control. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research: The Journal of the National Center. 2012;19(1):57–75. doi: 10.5820/aian.1901.2012.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushing SC, Stephens D. Tribal recommendations for designing culturally appropriate technology-based sexual health interventions targeting Native youth in the Pacific Northwest. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research: The Journal of the National Center. 2012;19(1):76–101. doi: 10.5820/aian.1901.2012.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutman S, Taualii M, Ned D, Tetrick C. Reproductive health and sexual violence among urban American Indian and Alaska Native young women: select findings from the National Survey of Family Growth (2002) Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2012;16(Suppl 2):347–352. doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-1100-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seamark CJ, Lings P. Positive experiences of teenage motherhood: a qualitative study. British Journal of General Practice. 2004;54(508):813–818. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sipsma HL, Ickovics JR, Lewis JB, Ethier KA, Kershaw TS. Adolescent pregnancy desire and pregnancy incidence. Women’s Health Issues. 2011;21(2):110–116. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SmithBattle LI. Reducing the stigmatization of teen mothers. MCN: The American Jouranl of Maternal/Child Nursing. 2013;38(4):235–241. doi: 10.1097/NMC.0b013e3182836bd4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somerville LH. Special issue on the teenage brain: Sensitivity to social evaluation. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2013;22(2):121–127. doi: 10.1177/0963721413476512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy. American Indian/Alaska Native youth and teen pregnancy prevention. 2009 Retrieved from http://www.thenationalcampaign.org/resources/pdf/SS/SS39_NativeAmericans.pdf.

- Tremblay L, Frigon JY. Biobehavioural and cognitive determinants of adolescent girls’ involvement in sexual risk behaviours: A test of three theoretical models. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality. 2004;13(1):29–44. [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi D, Brooks F, Bunn F, Graham M. Early fatherhood: a mapping of the evidence base relating to pregnancy prevention and parenting support. Health Education Research. 2009;24(6):999–1028. doi: 10.1093/her/cyp025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weed K, Nicholson JS. Differential social evaluation of pregnant teens, teen mothers and teen fathers by university students. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth. 2015;20(1):1–16. doi: 10.1080/02673843.2014.963630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White House, Executive Office of the President. 2014 Native youth report. 2014 Retrieved from https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/docs/20141129nativeyouthreport_final.pdf.