Abstract

Prior research suggests that under some conditions, interventions that aggregate high-risk youth may be less effective, or at worse, iatrogenic. However, group formats have considerable practical utility for delivery of preventive interventions, and thus it is crucial to understand child and therapist factors that predict which aggressive children can profit from group intervention and which do not. To address these questions we video-recorded group Coping Power intervention sessions (938 sessions), coded both leader and participant behavior, and analyzed both leader and children’s behaviors in the sessions that predicted changes in teacher and parent, reports of problem behavior at 1-year follow up. The sample included 180 high-risk children (69% male) who received intervention in 30 separate Coping Power intervention groups (six children assigned per group). The evidence-based Coping Power prevention program consists of 32 sessions delivered during the 4th and 5th grade years; only the child component was used in this study. The behavioral coding system used in the analyses included two clusters of behaviors for children (positive; negative) and two for the primary group leaders (group management; clinical skills). Growth spline models suggest that high levels of children’s negative behaviors predicted increases in teacher and parent rated aggressive and conduct problem behaviors during the follow-up period in the three of the four models. Therapist use of clinical skills (e.g., warmth, nonreactive) predicted less increase in children’s teacher-rated conduct problems. These findings suggest the importance of clinical training in the effective delivery of evidence-based practices, particularly when working with high-risk youth in groups.

Keywords: aggressive behavior, group process, clinical skills, preventive intervention

The developmental and intervention science literature presents a dilemma to the clinician focused on reducing or preventing disruptive behavior in children and adolescents by working with groups. On the one hand, several evidence-based interventions emphasize the importance of working with such youth in groups, to provide opportunities to practice social and coping skills critical to the reduction of problem behavior (e.g., Lochman et al., 2014; Lochman, Wells, Qu, & Chen, 2013). On the other hand, developmental research suggests that friendship with children with antisocial behavior is one of the most powerful predictors of growth of covert antisocial behavior in childhood, as well as drug use and violence in adolescence (Dishion & Patterson, 2016). Moreover, there is evidence to suggest that aggregating youth into group interventions, under some circumstances, has iatrogenic effects (Dishion, McCord, & Poulin, 1999; Dodge, Dishion, & Lansford, 2006). In the present study, we study the conditions under which group interventions lead to decreases in problem behavior in pre-adolescent youth, by carefully analyzing 938 videotaped intervention sessions to better understand the client and therapist dynamics that predict variation in response to a targeted prevention program.

There are several benefits to using a group format to interventions for youth with problem behavior. First, group intervention formats are important for widespread delivery of preventive interventions in school-based and community settings because of “economy of scale,” as group interventions can be delivered to large populations of individuals (McLean et al., 2001). Second, the group format permits children to model competent behaviors displayed by leaders and peers and to practice new social skills with peers (Lochman et al., 2015). Because of the advantages of group formats, many of the most effective interventions for children with antisocial behavior (e.g., Weiss et al., 2005) involve group delivery formats. One example is the Coping Power intervention, which was designed to both treat aggressive behavior and prevent future problem behavior, and its child and parent components have been typically delivered in group formats. Efficacy and effectiveness studies have indicated that Coping Power has been found to produce preventive effects by maintaining youths’ rates of substance use and delinquency at a 1-year follow-up, in comparison to the increases evident among randomly-assigned controls (Lochman & Wells, 2003, 2004). Long-term follow-up effects, 3 to 4 years after the intervention, have been found on youths’ externalizing behavior and callous-unemotional traits in school settings in two separate studies (Lochman et al., 2014; Lochman et al., 2013) and on substance use, externalizing behaviors, and callous-unemotional traits when children with psychiatric diagnoses were seen in treatment (Muratori et al., in press; Zonnevylle-Bender, Matthys, & Lochman, 2007). The 1-year follow-up effects on substance use and delinquency have been mediated by program-induced changes in children’s attributional biases, outcome expectations for aggression, internal locus of control, and consistent parental discipline (Lochman & Wells, 2002).

Despite these advantages, findings that emerged in the 1990’s had suggested group interventions, under some conditions, might have iatrogenic effects on youth problem behavior. As a result of deviant peer effects, group interventions may inadvertently escalate or maintain, rather than reduce, youth behavior problems. Developmental research has indicated that children with problem behavior are likely to affiliate with each other, and that involvement with deviant peers leads to increased risk for adolescent problem behaviors (Dishion & Patterson, 2016). In one notable example of deviant peer influence in intervention research, the follow-up of the Adolescent Transitions Program found that randomization to a cognitive-behavioral early adolescent group focusing on self-regulation resulted in improvements in observed family interaction, but unfortunately, also resulted in increases in youth reports of smoking and teacher reports of problem behavior at school at 1-year follow-up (Dishion & Andrews, 1995) and at a three-year follow-up (Poulin, Dishion, & Burraston, 2001).

In an effort to understand which youth were most likely to increase smoking and delinquent behavior following the Adolescent Transitions Group intervention, videotapes of the sessions were coded for the youth’s deviancy training and group leader characteristics. Observations of youth revealed that those youth who engaged in deviancy training during unstructured sessions were more likely to increase their smoking and delinquent behavior at school (Dishion, Poulin, & Burraston, 2001). Incidentally, youth with positive relationships with older peer counselors in the group had less growth in problem behavior in the three years afterwards. Although interesting, these analyses were limited due to the small sample size, poor quality videotapes of group sessions, and a relatively small number of group sessions to analyze.

In general, it has been difficult to disentangle the issue of potential iatrogenic effects associated with group interventions because all of the prior studies with these effects were not intending to investigate this problem. To address this important issue, we experimentally compared the effects of a group-versus individually-delivered format controlling for the number of sessions and session content. The findings were mixed, varying by source of data. Format differences did emerge on follow-up teacher-rated outcomes, and the difference favored an individual delivery format (Lochman et al., 2015). Although there was evidence that children in the group format had significant reductions in growth rates of problem behaviors through the 1-year follow-up, children who had received the individual format had significantly greater reductions in teacher-rated problems in the school setting than did children seen in groups. This effect was evident across teacher reports of children’s externalizing behaviors, internalizing problems, and their involvement with deviant peers. However, the two intervention formats did not differentially influence outcomes from parent reports, as both formats produced comparable significant declines in problem behaviors. Moderator analyses indicated that children in the group condition with relatively higher baseline levels of inhibitory control had greater reductions in teacher-rated externalizing behavior in comparison to children with relatively lower inhibitory control.

These findings of differential response to the group intervention suggests that it would be important to explore process-oriented variables during the delivery of the group intervention, involving children’s and group leaders’ behaviors within sessions, which might predict children’s outcomes. If such predictors are identified, these could have significant implications for future training relevant to dissemination of the group version of Coping Power, as well as other group based interventions.

Group Leader Behavior

Organized training in group therapy has not been prevalent in training programs for mental health professionals (Brabender, 2002), partly due to limited rigorous research on processes in group interventions. Similar to intervention research in general (Henry, Strupp, Butler, Schacht, & Binder, 1993), one of the most neglected areas in group intervention research has been that of therapist effects on groups (Chapman, Baker, Porter, Thayer, & Burlingame, 2010). With adult clients, there is some evidence that clients report the best effects with groups which have therapists (a) who provide appropriate structure and (b) who have warm, non-hostile interpersonal clinical skills (Chapman et al., 2010). The latter domain of group therapist behavior influences the emotional climate they provide in groups (Hurley, 1997). Therapists’ ability to regulate their emotional reactivity, triggered by clients, provides an effective model to the clients for their own emotional regulation (Pavio, 2013), and it has been proposed that group leaders’ management of their emotional presence in groups is an important element of therapy in general (Henry et al., 1993), and of group treatment in particular (Chapman et al., 2010).

There are very few studies that directly measure adult leadership skills in intervention groups with children. However, in reviewing the literature, it was clear that many group intervention studies did not produce iatrogenic effects. From these studies, it was surmised that carefully managed and supervised groups reduce the risk for iatrogenic effects. It was hypothesized that group management skills such as successfully handling deviant behavior in groups by redirecting attention, reestablishing appropriate norms, and respectfully controlling children’s behavior can dissipate deviant peer contagion (Dishion & Dodge, 2006). The one study that did observe group processes linked to growth in problem behavior found that youth engaged in ‘deviancy training’ during unstructured situations. In this study, unstructured situations comprised the transition before and after the group, and the break time within a 2 hour session (Dishion et al., 2001). These findings suggest that, as a minimum, structure and supervision of youth behavior in the groups with respect to deviancy training would reduce risk for iatrogenic effects. Adult behavior management strategies (rules, use of rewards and punishments) and specific teaching strategies (praise for cooperative behaviors; introduction, directions and review of activity; discussion of skills) are key dimensions of effective adult leadership in groups (Letendre & Davis, 2004).

Another key dimension of adult leadership is clinical skill, which can be defined as adult regulation of their own emotions during groups to create a safe and secure setting for youth engagement (Stewart et al., 2007). In a related way, Lochman and colleagues (2009) have found that counselors who are higher in the agreeableness personality dimension, and hence more flexible and able to self-regulate, are able to conduct real-world intervention groups with aggressive children with better implementation quality. However, we know remarkably little, from an empirical standpoint, about group therapists’ behavior management skills and clinical skills. It is unclear how therapists can optimally manage and run group sessions for aggressive children to promote children’s effective emotional regulation and to best counter the deviancy-promoting and deviancy-training effects that may be occurring during sessions. Research is required to explore the conditions under which variations in the delivery of groups might influence preadolescent aggressive children’s behavior (Weiss et al., 2005).

The Current Study

In the current study, we videotaped 938 group sessions of Coping Power involving at-risk 5th grade students in public elementary schools. In these sessions, we were able to carefully observe and reliably code each child’s behavior, as well as the behavior of the adult leaders. We used the group-delivered Coping Power child component reported by the Lochman et al. (2015) study. We examined how leaders’ group management skills and clinical skills, as well as problem behavior and deviancy training of the youth in sessions, predicted variation in adjustment outcomes over the ensuing year following the intervention. We hypothesized that children’s negative behavior in session would be prognostic of less improvement in their real-world aggressive behaviors and conduct problems in school and home settings after intervention. Relatedly, we also hypothesized that both the group leaders’ behavior management skills and clinical skills would be prognostic of steeper reductions in aggressive behavior and conduct problems through the next year.

Method

Participants

As part of a larger study evaluating the relative effectiveness of group (GCP) and individual (ICP) administrations of the Coping Power Program (Lochman et al., 2015), 360 4th grade students were recruited at their elementary schools. Using a teacher screening system, 4th grade students eligible for this study received scores in the top 25 percent of teacher ratings of aggressive behavior, indicating moderately to highly teacher-rated aggressive behavior among children in the study sample. To insure that children who were nonaggressive in the home setting were not included, children also had to score in the average range or above on a parent measure of aggression. The study encompassed three annual cohorts, with six children recruited from each of 20 schools each year.

At the 10 GCP schools which are the focus of the current study, each cohort of six children participated together in a small group, for a total of 30 separate intervention groups across the three cohorts. GCP students participated in an average of 28.54 group sessions (range = 0 to 34). The 938 group sessions were video recorded, and the recordings were later reviewed and coded.

At the time of recruitment, the 180 GCP children ranged in age from 9.3 to 11.8 years (Mean = 10.2). Boys (68.9%) and girls (31.1%) were included, who identified as African American (77.8%), Caucasian (17.8%), Hispanic (1.7%), and “Other” (2.8%). In terms of family income, 3.9% reported no income, 27.8% less than $15,000, 32.2% between $15,000 and $29,999, 16.7% between $30,000 and $49,999 and 19.4% greater than $50,000.

Most of the sample moved from elementary schools (Kindergarten through 5th grade) to middle schools (6th grade and above) during the follow-up year. With regard to whether children were in schools with at least some of their peers from their intervention group during the follow-up year, 76% of the students available for follow-up were in a school with at least one intervention group peer, and 24% were in schools where none of their intervention group peers were located.

Procedures

Data collection

Baseline (Time 1) measures were completed with children and parents during the spring semester of the children’s 4th grade year. Children participated in the Coping Power program during the last 2 months of 4th grade and throughout 5th grade. Post-intervention assessments (Time 2) occurred in the summer after 5th grade, and 1-year follow up assessments (Time 3) took place during the summer after students completed 6th grade. Assessments conducted with parents were typically in their homes, but occasionally in another location of the family’s choice (e.g., public library, restaurant). Parents received $50 for each assessment completed.

Fourth grade teachers provided baseline data (Time 1) during the spring semester of 4th grade, 5th grade teachers provided post-intervention data (Time 2) in the spring of the following year, and 1-year follow-up data (Time 3) were collected from 6th grade teachers 1 year later. Teachers received $10 for each student assessed. All study procedures were approved by the University of Alabama Institutional Review Board. In elementary school (grades 4 and 5), children’s classroom teachers completed the ratings. In middle school, the ratings were usually provided by the language arts teacher, but if that was not possible, then by the math or other available teacher. Neither teachers nor parents were informed about children’s specific behaviors in the group sessions.

Coping Power intervention

Coping Power is an evidenced-based manualized intervention that targets key social-cognitive deficits in children with aggressive behavior. The full Coping Power program includes a parenting component, but for this intervention study, only the child component was implemented (Lochman, Wells, & Lenhart, 2008). The GCP intervention included 32 group meetings, approximately 50–60 minutes in length, which were scheduled during the school day. The meetings were led by a grant-funded leader and a co-leader (e.g., school counselor, graduate student, research assistant).

Training and supervision of group leaders

Coping Power group leaders attended a 2-day training before the intervention. The training covered the background of the Coping Power program, results of prior outcome research, and a session-by-session overview of the curriculum. Leaders received guidance on behavior management strategies, but did not receive explicit instruction about deviancy training in groups. While the intervention was being implemented, weekly supervision meetings were held during which leaders provided updates on students’ progress, material to be delivered in upcoming sessions was reviewed, and issues that arose during Coping Power group meetings were discussed.

Measures

Cognitive-Behavioral Group Coding System (CBGCS)

A behavioral coding system was developed to rate child and leader behavior during Coping Power group sessions. The system was based on several existing coding systems for youth behavioral interventions (e.g., Dishion et al., 2001; McLeod & Weisz, 2010). A detailed codebook with examples of each behavioral code and its various rating levels was developed to facilitate the coder training process and to ensure high inter-rater reliability. None of the 17 trained coders coded sessions that they themselves had led.

Format of the Cognitive Behavioral Group Coding System

The CBGCS (Boxmeyer et al., 2015) utilizes a macro rating scale in which the interactions between each participant and all other participants are recorded in a matrix. Separate ratings were made for the behavior of each child participant and each group leader during the first ten minutes, middle ten minutes, and last ten minutes of each session, and the ratings were aggregated for analyses. This approach was selected based on previous research indicating that the periods of transition in and out of group are often the richest with respect to providing exemplars of interactions hypothesized to lead to negative effects of group intervention, whereas the middle segment is most likely to be a structured time in which participants are engaged in the planned intervention content. Children and leaders are coded on each item individually for each time segment. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale.

Child-rated behaviors include Positive child behaviors (e.g., showing involvement and interest in group discussion and activities; initiating positive and friendly interactions with other group members; other children initiating reciprocal positive and friendly interactions toward this child), and Negative child behaviors (e.g., deviant talk, exhibiting off-task, inattentive behavior; engaging in silly or disruptive behavior; demonstrating a negative, hostile attitude; exhibiting verbal or physical aggression; and appearing to trigger these negative behaviors in other group members). These two child codes are used in the current analyses.

Leader-rated behaviors include Behavior Management strategies (e.g., leader sets clear expectations and rules for group behavior; enforces rules for group behavior effectively; provides strategic reinforcement for desired behaviors, provides consequences for rule violations, adheres to an agenda/manages group time effectively; quiets the children and elicits their attention effectively) leader’s use of Teaching strategies (e.g., provides clear rationale for new topics and activities; provides clear instructions; reviews key teaching points; actively assesses children’s comprehension, creates “teaching moments,” leader elaborates the content beyond the manualized material), and Clinical Skill (e.g., leader’s tone is warm and positive; leader demonstrates professionalism in dress, behavior, and level of self-disclosure; leader is overly rigid-reverse scored; leader appears frustrated, angry or irritable-reverse scored). The scales for behavior management strategies and teaching strategies were highly intercorrelated in this sample (.85) and were thus aggregated into one code for analyses: Group Management Skills. The leader constructs thus used in analyses are: Group Management Skills and Clinical Skill.

Establishing and maintaining inter-rater reliability

Training involved nine video segments with a range of positive, negative, and neutral exemplars of child and leader behaviors. Each coder was required to establish 80% agreement (agreement was defined as ratings falling within one point of the comparison rating) during training. Coders then coded videos from specific Coping Power intervention groups, so that they could become familiar with the participants’ names and faces, to allow them to easily record interactions among participants and group leaders. Assignments were made such that each observer coded either the odd or even sessions for a particular intervention group, to maximize efficiency while also minimizing coder bias (as each intervention group was thus coded by at least two different observers). Seven percent of the Coping Power child group sessions were double-coded. This was done on an ongoing basis, to ensure that agreement remained at 80% or higher. All of the coders met periodically to discuss and document decision-making, to prevent coder drift. If a specific coder’s scores fell below 80% agreement, that coder had to re-establish reliability on additional training video segments before he or she could continue coding intervention sessions. Interrater reliability was adequate during the study (post-training), with agreement rates of 87.1% for Child behaviors (across 146 10-minute observation segments) and 85.1% for Group Leader behaviors (across 160 10-minute observation segments).

Internal consistency of child and leader summary behavior codes

Among the three summary codes for child behaviors, there was acceptable-to-excellent internal consistency for the 5-item Positive Behaviors variable (alpha: .90) and for the 9-item Negative Behaviors variable (.77). Excellent internal consistency was evident for the 15-item Leaders’ Group Management variable (.92). Good internal consistency was found for the 4-item Clinical Skills variable (.84). Although the “overly rigid” item was least related to the total Clinical Skills score (r=.16), the internal consistency for Clinical Skills was not substantially increased by deleting that item.

Outcome measures

Outcome measures for this study were parent- and teacher-rated Aggression and Conduct Problem behaviors. The Behavior Assessment System for Children (BASC; Reynolds & Kamphaus, 1992) is a behavior problem checklist that was completed for this project by children’s teachers and parents, and which has demonstrated strong reliability (Cronbach’s alpha of .80–.89) and construct validity (Doyle, Ostrander, Skare, Crosby, & August, 1997; Reynolds & Kamphaus, 1992). In elementary schools, the classroom teachers completed the BASC. In middle schools, the language arts teacher completed the BASC when possible; in the minority of cases where that could not be arranged, the math or other available teacher was asked to complete the ratings. For this study, the Aggression and Conduct Problem subscales were used. The alpha coefficients for the Parent BASC Aggression (.80) and Conduct Problems (.75) scales and the Teacher BASC Aggression (.91) and Conduct Problems (.73) scales at baseline for this sample of children receiving group interventions indicated adequate internal consistency.

Analytic Strategy

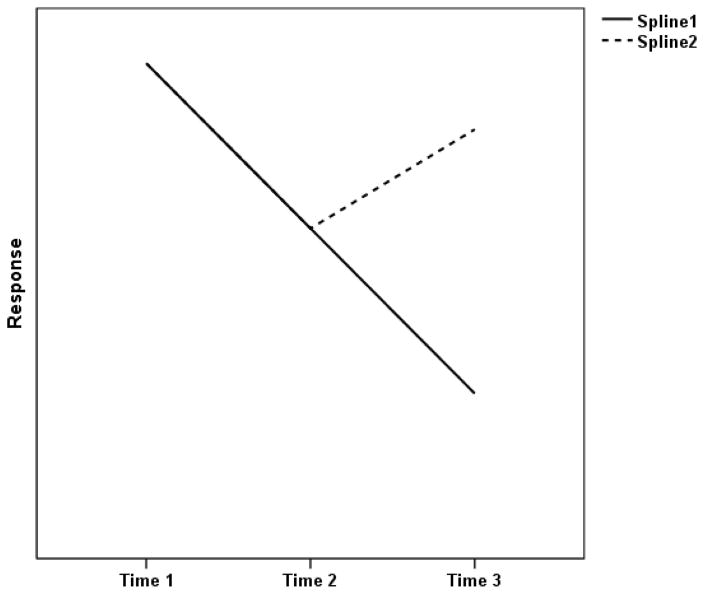

The growth spline model included three levels: (a) times of measurement, (b) nested within children, and (c) nested within the intervention units (six children per cohort per school). Growth spline models are a hybrid of spline modeling and growth modeling and examine how the effect of variables predicting outcome changes through time while simultaneously controlling for past effects (Schuelke, Terry, & Day, 2013). In spline modeling, the initial base trend begins with the first observation (spline 1 begins with pre-intervention assessment at Time 1 in the current model, and represents the overall growth in the outcome variable across the three time points), and spline 2 begins with the next observation (post-intervention assessment at Time 2, and represents the change in the outcome from Time 2 to Time 3). Thus, when Time was coded across the three time points (T1, T2, T3), Spline 1 had Time coded as 0, 1, 2, and Spline 2 had Time coded as 0, 0, 1. See Figure 1 for an illustration of the two splines.

Figure 1.

Illustration of Hypothetical Growth Spline Model

HLM 7.01 software was used to perform the data analyses with full maximum likelihood (FML) estimation method (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). The unconditional curvilinear growth models were tested by adding a time’s quadratic term to the level-1 model, and the Deviance Tests indicated that outcomes changed over time with a significant curvature pattern, thus requiring a three-level curvilinear growth model. For the teacher-rated outcome, time was coded as 0 as baseline, 1 as post-intervention, and 2 as 1-year follow-up, while for the parent-rated and child-report outcomes (where data collection took several months for each wave), we used the actual time interval from baseline as the time variable, with baseline set to zero. Each of the growth parameters in the level-1 model has a substantive meaning. The intercept π_0ij (initial status at baseline), time slope π_1ij (the linear change rate over time), and quadratic term π2ij (curvilinear change across time, capturing the curvature or acceleration in each growth trajectory) were estimated in the level-1 model equation for the curvilinear growth curve model, where Y_tij is the outcome score at time t for child i in intervention unit j. At level-2, the person level, we examined the child characteristics (children’s behavior within group sessions) that predicted growth rate of change; these were group mean centered. The intercept and time slope were treated as random effects at level-2. The quadratic term in the growth curvilinear model was treated as a fixed effect for the teacher- and parent-rated outcome with three times of measurements. The intercept and time slope were random effects at level-3, and all the cross-level interactions were fixed effects. The group leaders’ in-session behaviors were included on level-3 to detect effects of the growth rate of change, and all the cross-level interaction terms explored whether child in-session behavior significantly interacted with the group leaders’ in-session behaviors. In the level-3 model equations, u_00j, and 〖u〗_10j were the variance of population intercept and growth rate associated with intervention units. In this model, the variation in the growth parameters was partitioned as follows: (a) the variation among children within intervention unit was captured in the level-2 model, and (b) the variation among intervention units is represented in the level-3 model. To address missing outcome data (retention rates for parent ratings was 87% through the 1-year follow-up, and for teacher ratings was 82%), the HLM analyses used Full Maximum Likelihood to estimate model parameters.

Results

Means and standard deviations for the child and leader in-session behavior codes were: 1.82 (SD: 0.41) for child Positive behaviors, 0.31 (0.19) for child Negative behaviors, 0.00 (0.92) for the leaders’ standardized Group Management behaviors, and 0.00 (0.97) for the leaders’ standardized Clinical Skills. Children’s Positive behaviors were weakly related, in an inverse manner, to the Negative behavior code, r(180) = −.19, p<.01. The two Leader behaviors were moderately correlated, r(30) = .62, p<.01. The means and standard deviations for the four outcome variables (teacher- and parent-rated aggression and conduct problems) across time points are in Table 1.

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations of Child Outcome Variables

| Measure | Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| M | SD | N | M | SD | N | M | SD | N | |

| Teacher-rated BASC | |||||||||

| Aggression | 16.67 | 8.23 | 177 | 12.63 | 7.88 | 168 | 12.80 | 10.44 | 148 |

| Conduct Problems | 4.93 | 3.21 | 177 | 4.40 | 8.67 | 168 | 5.68 | 5.30 | 148 |

|

| |||||||||

| Parent-rated BASC | |||||||||

| Aggression | 11.33 | 5.55 | 180 | 9.85 | 5.11 | 165 | 9.67 | 5.28 | 157 |

| Conduct Problems | 6.36 | 3.99 | 180 | 5.81 | 3.61 | 165 | 6.49 | 4.22 | 157 |

Notes: BASC: Behavior Assessment System for Children. M: Mean, SD: Standard Deviation, N: is number of participants

Correlations were also computed between the leaders’ behaviors and the aggregated children’s behaviors within each group, and between the leaders’ and aggregated children’s behaviors in-session with children’s aggregated (by group) baseline Aggression and Conduct Problems scores (thus the N for these correlations are the 30 groups). The small N for these correlations limit the power for these tests, but it is apparent that at least moderate levels of correlation exist between child and leader behaviors within sessions. Group Management and Clinical Skills in leaders were related to child Positive (r(30) = .58, p<.01, and r(30) = .32, p=.08) and Negative (r(30) = −.44, p<.05, and r(30) = −.29, ns) behaviors, respectively. Nonsignificant associations were found between in-session behaviors and aggregated baseline scores of Aggression (range of .06 to .29 with children’s in-session behaviors, and of −.09 to .05 with leaders’ behaviors) and Conduct Problems (range of .02 to .26 with children’s in-session behaviors, and of −.18 to −.01 with leaders’ behaviors).

Correlations were computed between children’s behaviors within sessions and their behavioral outcomes across the four longitudinal assessment points (Table 2). Children’s teacher-rated baseline Time 1 behaviors are not associated with children’s subsequent behavior in the groups, but the in-session behaviors become associated with the teacher ratings that are made following the group. Low rates of children’s in-session positive behaviors are associated with teacher-rated aggression at post-intervention, and children’s negative behaviors are associated with their subsequent aggressive behavior and their conduct problems, especially by the 1-year follow-up. Parent-rated baseline Time 1 behaviors, especially their baseline ratings on Conduct Problems, are somewhat more associated with the children’s in-session behaviors, and children’s in-session behaviors were associated with parent-rated aggressive behavior and conduct problems following the intervention in a pattern similar to the teacher-rated outcomes. Correlations between the leaders behaviors’ and the children’s baseline and outcome behaviors, aggregated within their intervention group, were nonsignificant, in part because the low sample size (N=30 intervention groups) limited statistical power.

Table 2.

Correlations Between Child Behaviors Within Sessions and With Child Behavior Outcomes Through 1 year follow up

| Teacher-rated BASC | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Aggressive Behavior | Conduct Problems | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Child In-Session Behavior | Time 1 N=177 |

Time 2 N=168 |

Time 3 N=148 |

Time 1 N=177 |

Time 2 N=168 |

Time 3 N=148 |

| Positive | −.04 | −.21** | −.01 | −.12 | −.13 | −.10 |

| Negative | .10 | .13* | .31*** | .08 | .14 | .26*** |

|

| ||||||

| Parent-rated BASC | ||||||

|

| ||||||

|

Time 1 N=180 |

Time 2 N=165 |

Time 3 N=157 |

Time 1 N=180 |

Time 2 N=165 |

Time 3 N=157 |

|

|

| ||||||

| Positive | −.10 | −.21** | −.13 | −.18* | −.23** | −.18* |

| Negative | .11 | .16* | .20** | .17** | .21** | .22** |

Notes: BASC: Behavior Assessment System for Children.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Child outcomes predicted by child and leader in-session behaviors

Teacher-rated outcomes

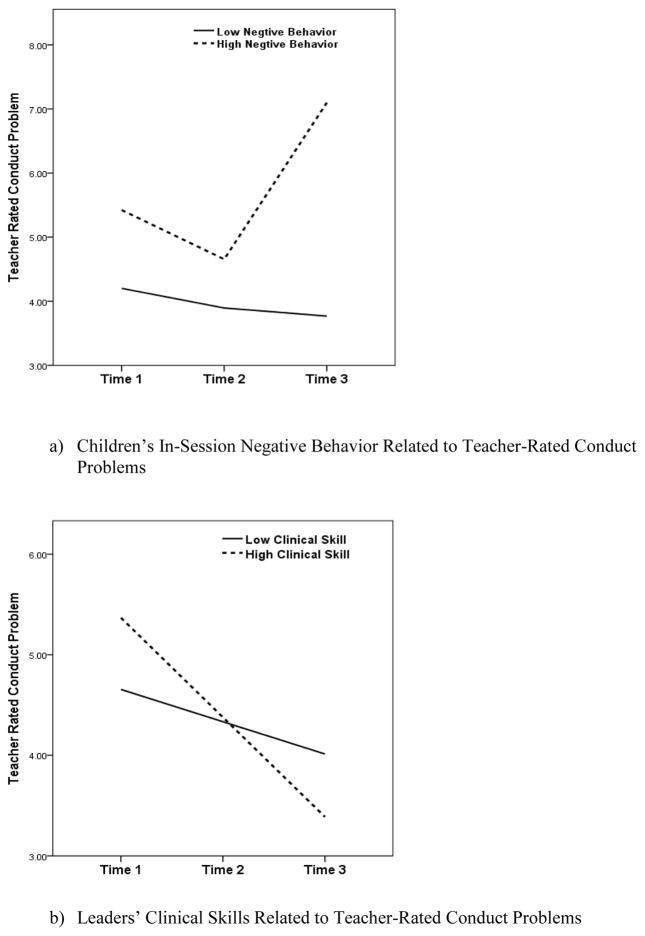

Table 3 provides summary statistics for the two growth spline models which predicted separately teacher-rated Aggression problems and Conduct Problems across time through the 1-year follow-up. Results for Unconditional Models are presented first, and then the significant predictors for the Time Slopes in the Conditional Models are included, separated into Spine 1 and Spline 2. Higher levels of children’s in-session Negative behaviors significantly predicted higher levels of Conduct Problem behavior slopes in Spline 2. Lower levels of Leaders’ Clinical Skills significantly predicted higher slopes for Conduct Problems in Spline 1. Teacher-rated Aggression was not predicted by these variables, and Children’s Positive Behaviors and Leaders’ Group Management skills did not significantly predict teacher ratings of either form of children’s problem behaviors across time1. The patterns for changes in children’s behavior when there were high versus low levels of the leader and child in-session behaviors are depicted in Figures 2a–2b. There were no significant interactions between leader and child in-session behaviors in predicting teacher-rated outcomes.

Table 3.

Summary of HLM Growth Curve Analyses

| Teacher-Rated Behaviors | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aggression | Conduct Problems | ||||||

|

|

|||||||

| Coef. | SE | P-Value | Coef. | SE | P-Value | ||

| Unconditional Model for Time Slope | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Overall Slope | −3.96 | 0.79 | 0.000 | −0.56 | 0.32 | 0.094 | |

| Spline 2 | 4.07 | 1.16 | 0.001 | 1.96 | 0.48 | 0.000 | |

|

| |||||||

| Model for Time Slope | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Overall Slope | −4.02 | 0.79 | 0.000 | −0.58 | 0.31 | 0.068 | |

|

| |||||||

| Predicted by Leader’s Behavior | Group Management | ||||||

| Clinical Skill | −0.49 | 0.22 | 0.035 | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Predicted by Children’s Behavior | Positive | ||||||

| Negative | −0.11 | 1.22 | 0.928 | −0.38 | 0.53 | 0.474 | |

|

| |||||||

| Spline 2 | 4.08 | 1.15 | .001 | 1.99 | 0.47 | 0.000 | |

|

| |||||||

| Predicted by Leader’s Behavior | Group Management | ||||||

| Clinical Skill | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Predicted by Children’s Behavior | Positive | ||||||

| Negative | 3.53 | 2.11 | 0.099 | 2.47 | 0.87 | 0.006 | |

|

| |||||||

| Parent-Rated Behaviors | |||||||

| Aggression | Conduct Problems | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| Coef. | SE | P-Value | Coef. | SE | P-Value | ||

|

| |||||||

| Unconditional Model for Time Slope | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Overall Slope | −1.35 | 0.32 | 0.000 | −0.47 | 0.24 | 0.063 | |

| Spline 2 | 1.25 | 0.54 | 0.023 | 1.30 | 0.36 | 0.001 | |

|

| |||||||

| Model for Time Slope | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Overall Slope | −1.34 | 0.32 | 0.000 | −0.46 | 0.24 | 0.065 | |

|

| |||||||

| Predicted by Leaders’ Behavior | Group Management | ||||||

| Clinical Skill | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Predicted by Children’s Behavior | Positive | ||||||

| Negative | −0.77 | 0.55 | 0.160 | −0.36 | 0.36 | 0.351 | |

|

| |||||||

| Spline 2 | 1.22 | 0.53 | 0.024 | 1.28 | 0.36 | 0.001 | |

|

| |||||||

| Predicted by Leaders’ Behavior | Group Management | ||||||

| Clinical Skill | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Predicted by Children’s Behavior | Positive | ||||||

| Negative | 2.50 | 0.94 | 0.009 | 1.40 | 0.63 | 0.029 | |

Notes: Nonsignificant terms were dropped from the analysis. Coef.: Coefficient, SE: Standard Error.

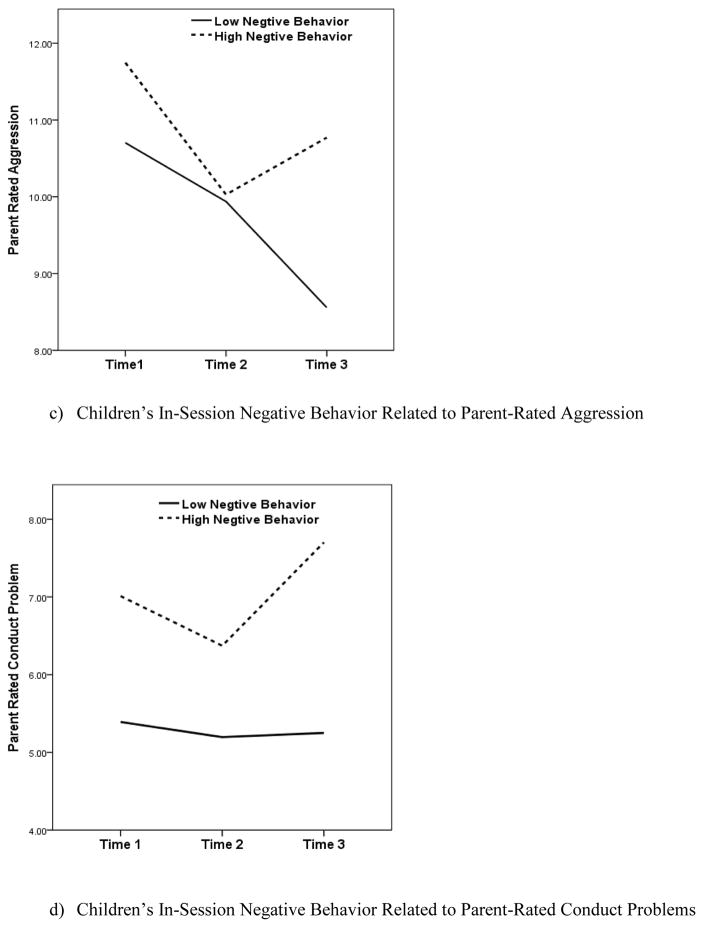

Figure 2.

Illustration of High (upper 25%) and Low (lowest 25%) levels of Children’s and Leaders’ Behaviors in Predicting Teacher- and Parent-Rated Aggression and Conduct Problems

Parent-rated outcomes

Table 3 provides summary statistics for the two growth spline models which predicted parent-rated Aggression and Conduct Problem behavior problems across time through the 1-year follow-up. Higher levels of children’s in-session Negative behaviors significantly predicted higher levels of parent-rated Aggression and Conduct Problem behavior slopes in Spline 2. Leaders’ in-session behaviors and the other child in-session behavioral categories for Positive Behavior did not predict parent-rated behavioral outcomes. The patterns for changes in children’s behavior when there were high versus low levels of the child in-session behaviors are depicted in Figures 2c–2d. There were no significant interactions between leader and child in-session behaviors in predicting parent-rated outcomes.

Discussion

The current results indicate that children’s and leaders’ behaviors during group intervention sessions for preadolescent aggressive youth may serve as important predictors of children’s behavioral functioning from pre-intervention through a 1-year follow-up after the intervention was completed. We were particularly interested in determining whether there were in-session behavioral predictors of children’s functioning in the school setting. The prior study (Lochman et al., 2015), which was the basis for the sample used in the current study, found that a group format for the Coping Power child component significantly reduced children’s externalizing behavior problems, as rated both by teachers and parents, but that the reduction in teacher-rated externalizing behavior problems was significantly greater for children seen in individual sessions than in group sessions. The current analyses indicate that children’s in-session negative behaviors predict children’s externalizing behaviors in the home and school settings during the follow-up year (the second spline of the growth models) in three of the four models, Although leaders’ group management skills did not emerge as a predictor of outcomes, and their clinical skills served as a predictor of overall slopes (spline 1 in the model for teacher-rated Conduct Problems) in only one of the four models tested, prior results had found less positive effects for the group format on this particular outcome (Teacher-rated conduct problems) (Lochman et al., 2015). Thus, the results raise questions for future research and training of group intervention leaders.

Children’s In-Session Behaviors

The two types of children’s in-session behaviors in this study were aggregate codes for negative behaviors and positive behaviors. Children’s positive behavior in the group sessions was largely unrelated to intervention outcome, and was not a useful predictor of children’s future behaviors. However, children’s negative behaviors during group sessions (ranging from deviant talk and aggressive behavior to inattentive, off-task behaviors) proved to be a valid and useful indicator of children’s behavioral functioning across time, predicting several aspects of parent and teacher ratings of problem behavior in the second spline of the growth model. Children’s negative in-session behaviors predicted slopes for teacher-rated Conduct Problems and parent-rated Aggression and Conduct Problems in the period of time between the end of intervention and 1-year follow-up assessment. As is illustrated in Figures 1a, 1c and 1d, children who displayed high levels of negative behaviors in sessions had sharply increasing levels of teacher and parent rated conduct problems and parent-rated aggression in the year after the intervention (after displaying some reduction in these teacher and parent rated problems during the intervention year itself), in contrast to children who had displayed less negative behavior during sessions. Effective behavioral management had been a major focus of the training and supervision of group leaders for this project; in the absence of this training, children’s rates of negative behaviors could have been higher and could have produced widespread deterioration in behavior.

The “pay-off” for lower levels of children’s negative behavior in the sessions was really in the year after intervention. At-risk children who displayed relatively lower levels of negative behavior during sessions may have become successfully engaged in the group procedures and developed productive alliances with group leaders, and since they were less off-task and inattentive they may have attended closer to intervention content. As a result they may have more deeply learned intervention skills and begun “spirals” of behavioral improvement that were maintained during the follow-up year when they were no longer in the intervention.

In contrast, children who displayed higher levels of negative behavior may have elicited more efforts by group leaders to manage their difficult behavior through the use of the external contingencies in the program, and this may have limited how these children’s negative behavior in the sessions may have translated into problems behaviors in their home and school settings during the intervention period. However, once the intervention was completed, and there were no longer external contingencies being provided by the program for children’s home and school behaviors, the stability between children’s in-session negative behaviors and their externalizing behaviors in their natural contexts appeared to have become more apparent. The Coping Power parent component was not used in this study, and if parents had been trained to provide consistent consequences they may have been able to provide stable contextual support for the children’s behavior changes initiated during the group intervention period. The current findings of decayed intervention effects during the follow-up period for some children suggests that future research could use sequential multiple assignment randomized trials (Almirall, Nahum-Shani, Sherwood, & Murphy, 2014) to re-randomize children who had displayed above average levels of negative behaviors in group sessions to their parents then receiving behavioral parent training (as with the Coping Power parent component) or not, in order to directly test this assumption.

Children’s negative behaviors during group sessions (off-task; inattentive; hostile) may be similar in form to the type of misbehavior these at-risk children display in the peer context and teaching structure evident in children’s daily experience in the school setting, and thus their negative group behaviors may be especially linked to future teacher ratings of conduct problems in the school environment. Similarly, children’s in-session negative behaviors predicted unregulated aggression and conduct problems in the home and community settings in the year after intervention.

Thus, children’s behaviors within sessions appear to be a rich source of information that can help to predict children’s future trajectories. It is important for therapists to attend closely to children’s in-session behaviors, especially noting high levels of negative behaviors and deviant talk in early sessions. Group therapist training can emphasize the importance of behavioral monitoring of these specific patterns of behaviors. This predictive pattern also suggests that group leaders can adjust their therapeutic behaviors, based on these monitoring efforts.

Group Leaders’ In-Session Behaviors

Interestingly, children’s baseline levels of aggression in the home and school settings prior to the group sessions did not predict children’s rates of negative behaviors in the group sessions, but children’s in-session rates of problematic behaviors did predict their subsequent behavioral outcomes. Thus, group interventions create an opportunity for new learning, which can be either positive or negative. Although group leader behaviors were significant predictors in only one of the four models tested, the group leaders’ behaviors may help to determine the direction of the children’s conduct problems across the intervention period and through the follow-up year in the school setting.

We see this opportunity for change within group interventions as being likely dependent on the clinical skills of the group leader. Although we did not randomly assign youth to skillful and unskillful group leaders, the effects of clinical skill in the multilevel model for teacher-rated conduct problems suggest its relevance. To illustrate this point, we graphically represent the growth in teacher ratings of conduct problems in youth in groups with low versus high levels of observed clinical skill. As seen in the illustration of the Spline 1 effect in Figure 1b, children who had worked with least clinically-skilled leaders, in comparison to other children who had most clinically-skilled group leaders, began with somewhat lower rates of conduct problems at pre-intervention, and had smaller decreases in conduct problems through the intervention and year after, while the leaders with higher clinical skills had children with the greater overall declines in teacher-rated conduct problems across the project.. Given the correlation between youth behavior in session and clinical skill, we suggest that a dynamic emerges involving youth in-session problem behavior and attenuated leadership skills. This deviant dynamic presents a liability to the youth.

Role of clinical skills

The clinical skills construct included ratings for not appearing frustrated angry or irritable, having a warm and positive tone of voice with students, acting in a mature and professional way (dress, type of humor, and level of self-disclosure that are appropriate for adult intervention staff), and not being overly rigid with the implementation of the manualized intervention activities. The ratings indicating the leaders’ emotional tone in the session loaded most strongly on this construct. Leaders with high levels of clinical skills had children who had reduced slopes of teacher-rated conduct problems over time, relative to children who had worked with group leaders who had lower levels of these skills.

There are at least three interrelated ways in which group leaders’ clinical skills may have been associated with children’s teacher-rated conduct problems over time, although the direction of causal effects are only suggested by the correlational design of this study. The following are suggestive implications, and can guide more definitive research. First, group therapists who handle difficult interpersonal provocations from their child clients by exerting inhibitory control over their expression of their own frustration and by effectively regulating their arousal are modeling key processes which can be instrumental for children learning to improve their own emotional regulation over time (Chapman et al., 2010; Stewart et al., 2007). Some therapists, including those who have more agreeable personality traits, may find it easier to respond in relatively automatic, flexible, self-regulated ways, and to thus implement group cognitive-behavioral intervention in qualitatively better ways (Lochman et al., 2009). Other group leaders likely have to use more deliberate strategies themselves to monitor their arousal in sessions and to purposefully use cognitive and physiological regulation strategies. As children’s frustration tolerance and self-regulation abilities develop due to their modeling of the group leader, they may be less prone to act out in overt and covert ways. Second, group leaders who respond more frequently in warm ways to the children in their groups are likely providing more social reinforcement for positive child behaviors within the group and sustained improvement in reducing covert and overt problem behaviors outside of the group sessions. The group leader’s social reinforcement value can be enhanced if children perceive the warm group leader in progressively more positive ways. Children who display high levels of covert antisocial behaviors have been found to have less positive and cohesive family interactions (Kazdin, 1992), and they may be especially sensitive to warm, reinforcing group leaders. Third, in a related way, group leaders who respond to children with more warmth are likely to develop stronger therapeutic alliances with the children, and children who are thus more engaged in the intervention can learn the social-emotional skills more deeply and can display fewer problematic behaviors within the group sessions from the outset (Ellis, Lindsey, Barker, Boxmeyer, & Lochman, 2013).

Group leaders’ clinical skills were related to the course of teacher-rated Conduct Problems but not to teacher-rated Aggression or to parent-rated behavioral outcomes. Loeber (1982) developed and tested a model of the development of youth antisocial behavior which differentiated overt antisocial behavior (e.g., aggression, quarrelling, fighting, disobedience) from covert antisocial behavior (e.g., lying, stealing, truancy, vandalism). This distinction largely parallels the difference between the BASC scales used in the present study for Aggression (threatening others; hitting others; argumentative; defiant) and for the rule-breaking behaviors labelled as Conduct Problems (stealing; lies; destruction of property; hurts others on purpose). The growth in covert antisocial behaviors during elementary school years has been found to be a significant predictor of serious overall antisocial behavior (including both aggressive behaviors and conduct problems) by the end of elementary school (Snyder, Schrepferman, Bullard, McEachern, & Patterson, 2012), indicating the concerning developmental importance of this form of problem behavior. Involvement with deviant peers has been found to be an important contributor to the development of covert antisocial behaviors (Snyder et al., 2012). Thus, group leaders’ clinical skills may interfere in particular with deviant peer processes in their groups which could otherwise contribute to evolving covert conduct problems in the school setting.

Limitations

Despite the intriguing descriptive findings about the predictive roles for group leaders’ behaviors and children’s in-session behaviors in predicting children’s levels of behavioral problems across time, several limitations exist. First, the analyses were correlational in nature, and do not confirm causal effects. Second, the leaders’ and children’s behaviors within the group sessions are likely to meaningfully influence each other, with some group leaders’ behaviors being evoked by the children’s behavior. Powerful eliciting effects of one person’s behavior on another person’s behavior have long been noted in social interactions (Lochman & Allen, 1979), and it has been repeatedly noted that children’s behavior can elicit specific parental behaviors (e.g., Huh, Tristan, Wade, & Stice, 2006; Lansford et al., 2011). It is likely that children and counselors have similar eliciting effects on each other, creating complex reciprocal effects. As a result, although children’s baseline behavior did not significantly predict subsequent group leader behavior, we cannot conclude in this study that group leaders’ behaviors clearly led to children’s behaviors in the group or to their subsequent behavior. Third, although significant effects were found, group leaders’ clinical skills emerged as a significant correlate of children’s outcomes in only one of the four models, and thus the result must be interpreted cautiously.

Fourth, although a strength of this study is that two sources (teacher, parent) were used to measure children’s outcomes across time, the effects of children’s and leaders’ in-session behaviors were apparent for only one or two of the sources. This may reflect some contextual variation in the findings (e.g., differences between how children behave at home versus at school), or may be the result of measurement error in the sources. Fifth, the findings can be generalized best to fairly similar group interventions. The intervention investigated was a structured and manualized evidence-based program for preadolescents, and was delivered after intensive training, which included workshops for the group leaders, weekly supervision, and monthly performance feedback during the intervention. The findings from this study may have less relevance for more unstructured interventions, for interventions delivered with less extensive training and supervision, and for interventions delivered at other developmental periods. Thus, leaders’ group management skills may be more predictive of outcomes when there is a wider range of these skills in real-world clinicians, in contrast to the potentially narrower range of behavioral management skills in our relatively well-trained group leaders. Sixth, although the results indicate predictive relations between the group behavior of children and leaders on children’s behavior through later assessment periods, the design of the study is not experimental and does not confirm causal connections between group behaviors and later child behaviors. While it is possible to randomly assign therapists to training and oversight, we are beginning to see a potential ethical issue emerging in this next logical phase of research. In many ways, this study clarifies that, indeed, unstructured or unskilled group leaders working with high-risk youth could potentially exacerbate the very adjustment problems that they wish to ameliorate (Dishion & Dodge, 2006). As found in previous research on a group intervention for high school youth, an evidence-based prevention program produced several negative effects when implemented by school staff with less clinical training and oversight (see Cho, Hallfors, & Sánchez, 2005).

Summary

An overall conclusion from this large set of observations of 938 group intervention sessions is that a warm, non-irritable therapeutic style, in the context of a structured program that heavily emphasizes consequences for children’s behavior, may be a key therapeutic stance for leaders of group interventions for preadolescent aggressive children. This “authoritative” therapeutic stance, much like authoritative parenting (Baumrind, 1971) which balances reasonable demands and expectations with high warmth and responsiveness to the child’s needs, has particular value in reducing children’s conduct problem behaviors. Leaders’ clinical skills appear to enhance children’s engagement in intervention and reductions in their rates of conduct problems in the school setting outcomes. Leaders who can regulate their own emotions well are likely to handle frustrating issues with children in their groups without displaying their own irritability and anger, and thus model effective emotional regulation. It is also important to provide warm, non-irritable limit-setting for children in sessions, helping to inoculate them from negative peer influences in the group and during the follow-up year which otherwise could cause behavioral deterioration. Future research can explore these relations, and can examine the complex eliciting effects between children’s and leaders’ behaviors within and across sessions.

Within the limitations of this study and the finding of leader behavior effects in only one of the four tested models, these findings can have important implications for training of staff who are delivering group interventions for children. It appears that therapists should be trained to carefully monitor children’s rates of negative and deviant behaviors at various points in group sessions, as these behaviors provide reliable indicators of children’s subsequent functioning. Training should also provide experiential training and performance feedback in consistent behavioral management, crisp and flexible introduction of concepts and activities, all while being delivered in a warm, non-irritable manner. This suggests that training of group leaders should emphasize not only skill-training in a traditional sense, but also focus on how group leaders can practice emotional regulation themselves while engaged in group work that can be inherently stressful and frustrating at times. In the absence of focused training on group leaders’ behavioral management and emotional regulation abilities, group interventions can at the least depress positive effects of intervention (Lochman et al., 2015) or at the worst lead to iatrogenic effects if children engage in higher rates of deviant behavior than before the intervention (Dishion & Andrews, 1995). Thus, there are clinical and ethical bases for professionals delivering group interventions to obtain rigorous, evidence-based training and performance feedback.

Acknowledgments

This paper has been supported by grants from the National Institute of Drug Abuse (R01 DA023156) and the National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (R01 HD079273). John Lochman is the co-developer of the Coping Power program, and he receives royalties from Oxford University Press for the implementation guides for this program.

Footnotes

In follow-up exploratory analyses of the two predictors of teacher-rated Conduct Problems, conducted because of potential colinearity due to significant correlations among predictors, three HLM analyses using on predictor were conducted. When only child negative behavior was used as a predictor, negative behavior significantly predicted the slope for Conduct Problems, T (118) = 2.68, p = .008. When only leaders’ Clinical Skills was as a predictor, Clinical Skills significantly predicted the slope for Conduct Problems, T (28) = −2.28, p = .03. When only leaders’ Group Management behaviors was a predictor, Group Management did not significantly predict the slope for Conduct Problems, T (28) = −0.54, p = .59. Thus, the pattern of predictors in single-predictor models for teacher-rated Conduct Problems exactly paralleled the results for the full model tested.

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- Almirall D, Nahum-Shani I, Sherwood NE, Murphy SA. Introduction to SMART designs for the development of adaptive interventions: With applications to weight loss research. Translational Behavioral Medicine. 2014;4:260–274. doi: 10.1007/s13142-014-0265-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. Current patterns of parental authority. Developmental Psychology Monograph. 1971;4:1–103. [Google Scholar]

- Boxmeyer C, Powell NP, Lochman JE, Dishion TJ, Wojnaroski M, Winter C. Cognitive-Behavioral Group Coding System. University of Alabama; Tuscaloosa, AL: 2015. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Brabender V. Introduction to Group Therapy. New York: Wiley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman CL, Baker EL, Porter G, Thayer SD, Burlingame GM. Rating group therapist interventions: The validation of the Group Psychotherapy Intervention Rating Scale. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice. 2010;14:15–31. [Google Scholar]

- Cho H, Hallfors DD, Sánchez V. Evaluation of a high school peer group intervention for at-risk youth. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33:363–374. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-3574-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Andrews DW. Preventing escalation in problem behaviors with high-risk young adolescents: Immediate and 1-year outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63:538–548. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.4.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Dodge KA. Deviant peer contagion in interventions and programs: An ecological framework for understanding influence mechanisms. In: Dodge KA, Dishion TJ, Lansford JE, editors. Deviant peer influences in programs for youth: Problems and solutions. New York, NY: Guilford; 2006. pp. 14–43. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, McCord J, Poulin F. When interventions harm: Peer groups and problem behavior. American Psychologist. 1999;54:755–764. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.9.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Patterson GR. The development and ecology of antisocial behavior: Linking etiology, prevention, and treatment. In: Cicchetti D, editor. Developmental psychopathology, volume 3, maladaptation and psychopathology. 3. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley; 2016. pp. 647–678. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Poulin F, Burraston B. Peer group dynamics associated with iatrogenic effect in group interventions with high-risk young adolescents. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 2001;91:79–92. doi: 10.1002/cd.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Dishion TJ, Lansford JE. Deviant peer influences in intervention and public policy for youth. Social Policy Report. 2006;20:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle A, Ostrander R, Skare S, Crosby RD, August GJ. Convergent and criterion-related validity of the behavior assessment system for children-parent rating scale. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1997;26:276–284. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2603_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis ML, Lindsey M, Barker ED, Boxmeyer CL, Lochman JE. Predictors of engagement in a school-based family preventive intervention for youth experiencing behavioral difficulties. Prevention Science. 2013;14:457–467. doi: 10.1007/s11121-012-0319-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry WP, Strupp HH, Butler SF, Schacht TE, Binder JL. Effects of training in time-limited dynamic psychotherapy: Changes in therapist behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61:434–440. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.3.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh D, Tristan J, Wade E, Stice E. Does problem behavior elicit poor parenting? A prospective study of adolescent girls. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2006;21:185–204. doi: 10.1177/0743558405285462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley JR. Interpersonal theory and measures of outcome and emotional climate in 111 personal development groups. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research and Practice. 1997;1:86–97. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE. Overt and covert antisocial behavior: Child and family characteristics among psychiatric inpatient children. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 1992;1:3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Criss MM, Laird RD, Shaw DS, Pettit GS, Bates JE, Dodge KA. Reciprocal relations between parents’ physical discipline and children’s externalizing behavior during middle childhood and adolescence. Development and Psychopathology. 2011;23:225–238. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letendre J, Davis K. What really happens in violence prevention groups? A content analysis of leader behaviors and child responses in a school-based violence prevention project. Small Group Research. 2004;35:367–387. [Google Scholar]

- Lochman JE, Allen G. Elicited effects of approval and disapproval: An examination of parameters having implication for counseling couples in conflict. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1979;47:636–638. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.47.3.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochman JE, Baden RE, Boxmeyer CL, Powell NP, Qu L, Salekin KL, Windle M. Does a booster intervention augment the preventive effects of an abbreviated version of the Coping Power Program for aggressive children? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2014;42:367–381. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9727-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochman JE, Dishion TJ, Powell NP, Boxmeyer CL, Qu L, Sallee M. Evidence-based child preventive intervention for antisocial behavior: A randomized study of the effects of group versus individual delivery. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2015;83:728–735. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochman JE, Powell N, Boxmeyer C, Qu L, Wells K, Windle M. Implementation of a school-based prevention program: Effects of counselor and school characteristics. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2009;40:476–497. [Google Scholar]

- Lochman JE, Wells KC. Contextual social–cognitive mediators and child outcome: A test of the theoretical model in the Coping Power program. Development and Psychopathology. 2002;14:945–967. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402004157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochman JE, Wells KC. Effectiveness of the Coping Power Program and of classroom intervention with aggressive children: Outcomes at a 1-year follow-up. Behavior Therapy. 2003;34:493–515. [Google Scholar]

- Lochman JE, Wells KC. The Coping Power Program for preadolescent aggressive boys and their parents: outcome effects at the 1-year follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:571–578. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.4.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochman JE, Wells K, Lenhart L. Coping Power: Child group facilitator’s guide. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lochman JE, Wells KC, Qu L, Chen L. Three-year follow-up of Coping Power intervention effects: Evidence of neighborhood moderation? Prevention Science. 2013;14:364–376. doi: 10.1007/s11121-012-0295-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R. The stability of antisocial and delinquent behavior: A review. Child Development. 1982;53:1431–1446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean PD, Whittal ML, Thordarson DS, Taylor S, Sochting I, … Anderson KW. Cognitive versus Behavior Therapy in the group treatment of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:205–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod BD, Weisz JR. The Therapy Process Observational Coding System for Child Psychotherapy Strategies scale. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2010;39:436–443. doi: 10.1080/15374411003691750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muratori P, Milone A, Manfredi A, Polidori L, Ruglioni L, Lambruschi F, Masi G, Lochman JE. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services. Evaluation of improvement in externalizing behaviors and callous-unemotional traits in children with Disruptive Behavior Disorder: A 1-year follow up clinic-based study. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavio SC. Essential processes in emotion-focused therapy. Psychotherapy. 2013;50:341–345. doi: 10.1037/a0032810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulin F, Dishion TJ, Burraston B. 3-year iatrogenic effects associated with aggregating high-risk adolescents in cognitive-behavioral preventive interventions. Applied Developmental Science. 2001;5:214–224. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CR, Kamphaus RW. Behavior Assessment System for Children: Manual. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Schuelke M, Terry R, Day E. Growth spline modeling. Cary, NC: SAS; 2013. http://support.sas.com/resources/papers/proceedings13/285-2013. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder JJ, Schrepferman LP, Bullard L, McEachern AD, Patterson GR. Covert antisocial behavior, peer deviancy training, parenting processes, and sex differences in the development of antisocial behavior during childhood. Development and Psychopathology. 2012;24:1117–1138. doi: 10.1017/S0954579412000570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart JL, Christner RW, Freeman A. An introduction to cognitive-behavior group therapy with youth. In: Christner RW, Stewart JL, Freeman A, editors. Cognitive-behavior group therapy with children and adolescents. New York: Routledge; 2007. pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss B, Caron A, Ball S, Tapp J, Johnson M, Weisz JR. Iatrogenic effects of group treatment for antisocial youths. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:1036–1044. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.6.1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zonnevylle-Bender MJ, Matthys W, Lochman JE. Preventive effects of treatment of disruptive behavior disorder in middle childhood on substance use and delinquent behavior. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46:33–39. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000246051.53297.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]