Abstract

Tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) represents a potential strategy for the treatment of cardiac remodeling, fibrosis and/or diastolic dysfunction. The effects of oral treatment with BH4 (Sapropterin™ or Kuvan™) are however dose-limiting with high dose negating functional improvements. Cardiomyocyte-specific overexpression of GTP cyclohydrolase I (mGCH) increases BH4 several-fold in the heart. Using this model, we aimed to establish the cardiomyocyte-specific responses to high levels of BH4. Quantification of BH4 and BH2 in mGCH transgenic hearts showed age-based variations in BH4:BH2 ratios. Hearts of mice (<6 months) have lower BH4:BH2 ratios than hearts of older mice while both GTPCH activity and tissue ascorbate levels were higher in hearts of young than older mice. No evident changes in nitric oxide (NO) production assessed by nitrite and endogenous iron-nitrosyl complexes were detected in any of the age groups. Increased BH4 production in cardiomyocytes resulted in a significant loss of mitochondrial function. Diminished oxygen consumption and reserve capacity was verified in mitochondria isolated from hearts of 12-month old compared to 3-month old mice, even though at 12 months an improved BH4:BH2 ratio is established. Accumulation of 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) and decreased glutathione levels were found in the mGCH hearts and isolated mitochondria. Taken together, our results indicate that the ratio of BH4:BH2 does not predict changes in neither NO levels nor cellular redox state in the heart. The BH4 oxidation essentially limits the capacity of cardiomyocytes to reduce oxidant stress. Cardiomyocyte with chronically high levels of BH4 show a significant decline in redox state and mitochondrial function.

Keywords: 7,8-Dihydrobiopterin; Biopterin; Neopterin; Electron Paramagnetic Resonance; GTP cyclohydrolase I

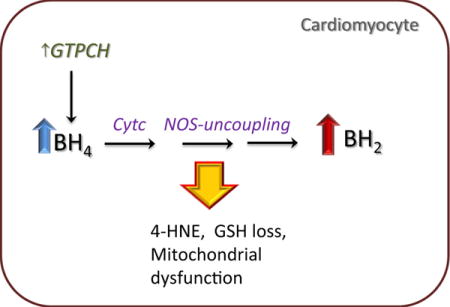

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) is an essential cofactor for the synthesis of nitric oxide (NO) by all three nitric oxide synthases (NOS) [1–3]. In the heart, basal NO levels produced by constitutively expressed NOS are attributed with the maintenance of essential cardiac functions such as calcium homeostasis [4,5], contractility [6], defense against stress conditions resulting from ischemia/reperfusion [7,8] and hypoxia [9]. Development of therapies to increase cardiac BH4 levels are based on the notion that increased BH4 levels will improve NO-dependent responses. Also increasing BH4 levels in the heart prevents oxidant injury from superoxide generated from NOS via an uncoupling mechanism [10–11].

Cellular levels of BH4 in cardiomyocytes and endothelial cells is effectively increased several fold by upregulating the expression of GTP cyclohydrolase I (GTPCH) [12]. In the de novo biosynthetic pathway GTP is used as a substrate and it is converted to BH4 by the concerted action of three enzymes: GTPCH, pyruvoyltetrahydropterin synthase (PTPS) and sepiapterin reductase (SR). The GTPCH catalyzes the first committed step of the pathway. Since increase in GTPCH expression and activity in several cell types is followed by an increase in intracellular BH4, this enzyme is considered rate-limiting in BH4 synthesis [13]. The salvage pathway uses as substrate 7,8-dihydrobiopterin (BH2), the two electron oxidation product of BH4, that is reduced to BH4 by dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) at the expense of NADPH. The efficiency of the salvage pathway is highly dependent on cell- and tissue-specific variations of DHFR and folate metabolism [14,15]. In adult cardiomyocytes DHFR protein expression is not detected [16].

Previously, it has been shown that neonatal cardiomyocytes upregulate GTPCH in response to increase release of cytokines such as IL-1, IFN, and TNF [17]. The concept has been developed that a co-upregulation of both GTPCH/BH4 and iNOS pathways in the heart may explain several of the damaging effects of cytokines [18]. Adult cardiomyocytes stimulated with cytokines, lipopolysaccharides or combination of both however demonstrated weakened responses in terms of upregulated GTPCH expression and BH4 production [16,19]. This observation raised the possibility that cardiomyocytes do not mediate NO-regulated responses to cytokines in the adult heart, and that increased GTPCH/NO are better explained by stimulation of other cell types in the heart and/or due to infiltrating inflammatory cells [20,21]. To clarify this idea, we generated a mouse model expressing GTPCH gene in a cardiomyocyte-specific manner (mGCH) [22]. Analysis of the transgenic mouse heart confirmed an increased expression of GTPCH protein together with high BH4 production. Notably, this model showed that increased BH4 production protected the heart against acute allograft rejection as shown by decreased histological rejection, cardiac injury and cell death. These responses however were not linked to NO surge but to changes in IL-2 and stromal derived factor-1 expression levels [22]. Another model for the cardioprotective activity of cardiomyocyte-targeted BH4 was indicated in a hyperglycemic model of ischemic preconditioning (IPC) [23]. In this experimental model, BH4 reverted the negative effects of hyperglycemia on myocardial and mitochondrial protection by IPC. These effects were in part linked to an improved mitochondrial calcium response that is otherwise altered in hyperglycemic conditions.

Previous studies by others addressing the potential use of BH4 in cardiac disease incorporated the use of exogenous BH4 [24,25]. Using a mouse model of pressure overload-induced cardiac hyperthrophy, it was shown that BH4 treatments reduced maladaptive cardiac remodeling [25]. BH4 effects however presented dose-dependent limitations, with high doses given orally showing no benefits. This effect was linked to the decreased ability of BH4 to inhibit superoxide generation. Since orally-administered BH4 targets different cell types in the heart, it is difficult to specifically attribute these responses to cardiomyocytes. Moreover, our understanding of the stability of BH4 and degree of NOS-activation elicited when present in high concentrations as seen in cardiomyocytes treatment is limited. This study tested the hypothesis that the predominant mechanism limiting BH4 activity in cardiomyocytes is not due to changes in NO production. Studies were conducted in mice with cardiomyocyte-specific overexpression of GTPCH in vivo and examining temporal variations in BH4 fluxes and BH4:BH2 ratios, cardiac NO production and its impact on mitochondrial bioenergetics.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All experiments conducted on animals in this study were performed in compliance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Pub No. 85–23). Protocols and procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Medical College of Wisconsin.

Biochemical Methods

Quantification of BH4, BH2 and ascorbate using HPLC with electrochemical detection

Left ventricular tissue was homogenized in cold 50 mM phosphate buffer pH 2.6 with 0.1 mM diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA) and 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTE), freshly added. Samples were spun down at 15700 × g for 20 min. The pellets were discarded and supernatant was transferred to Amicon 10K (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.) filters for deproteinization. An aliquot of the supernatant was also taken for protein quantification. The eluents from 45-min centrifugation 15000 × g were loaded onto a Synergi Polar RP column (250×4.6mm, Phenomenex, Torrance CA) and components were eluted using a flow of 0.7 ml/min of 25 mM phosphate buffer pH 2.6. Compounds were detected using a CoulArray™ detector (ESA Biosciences) equipped with a 4-sensor cell operating at 0,150, 280 and 365 mV, as described [26]. Standards were used for quantification and concentrations were normalized to protein content of the samples.

Enzymes activity

A. GTPCH. Enzyme activity was determined as previously described [27], with some modifications. Briefly, heart and liver tissue were homogenized in 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4 buffer, containing 1 mM MgCl2, 0.1 M KCl, 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetate (EDTA), 1 mM ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid (EGTA), freshly-added 0.2 mmol/L phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 1.0 μg/mL each of aprotinin, leupeptin, and pepstatin. Supernatants obtained by centrifugation of samples for 15 min at 4 °C, at 12,000 × g were transferred to a pre-chilled clean tube and centrifuged for additional 45 min at 15,000 × g. A 300 μL aliquot of the supernatant was added to 300 μL of reaction buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, containing 0.3 M KCl and 2.5 mM EDTA) containing 2.5 mM freshly added Guanosine-5′-triphosphate (GTP), 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 2.5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). The reaction was stopped by adding 3 μl 5N HCl at 0, 1h and 2h time points. The oxidation of the reaction product 7,8-dihydroneopterin triphosphate to neopterin triphosphate was performed at room temperature by adding 15 μL of oxidizing solution (0.04 g% iodine and 0.08 g% potassium iodide in 1 N HCl) and incubated for 60 min in the dark. The excess of unreacted I2/KI reagent was removed by the addition of 2 μl 20% ascorbic acid solution. To remove phosphate groups from neopterin triphosphate, samples pH were adjusted to 9–10 and incubated with 5U alkaline phosphatase solution (Sigma) at 37 °C for 60 min. Samples were cleaned by filtration through filters (10K m.w.c.o Millipore, Bedford, Mass.), and loaded onto a Kinetex C18 column (100mm×4.6 mm 2.6 um, Phenomenex) and eluted with 0.05% TFA 0.7ml/min. D-Neopterin was detected by fluorescence using an excitation of 350 nm and an emission of 440 nm. Standards were used for quantification and concentrations were normalized to protein content of the samples.

Aconitase

Freshly isolated hearts were washed in ice-cold DPBS and then homogenized in freshly prepared 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer containing 0.1 mM DTPA and 5 mM citrate. Samples were centrifuged 800 × g and the supernatant transferred to a fresh ice-water cold tube, which was subsequently centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min., all spins were performed at 4°C. The supernatants from 10,000 × g spin were collected (cytosolic fraction) and the pellet (mitochondrial fraction) was dissolved in 200 μl homogenization buffer containing 5mM citrate. Protein content of the fractions was determined by bicinchoninic acid assay. Proteins were diluted at a concentration of 5 mg/ml and assayed for activity using 50mM Tris-HCl buffer pH 8.0 containing 20mM DL-isocitrate and 0.1% triton x-100 at 240nm for 3 min at room temperature. Initial rates of enzyme activity were measured from kinetic curves and concentrations calculated using an extinction coefficient of 3.6mM−1cm−1 [28].

Reduced and oxidized glutathione analysis by HPLC using a boron-doped diamond electrode (BDD)

Left ventricle tissue samples were homogenized in cold 25 mM phosphate buffer pH 2.6 containing 0.1% triton X-100. Following centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 10 min to remove cell debris, an aliquot of supernatants were deproteinized by acid precipitation using 1:1 volume metaphosphoric acid 10% for 1 h on ice and another for protein measurement. Supernatants obtained from centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 45 min of acid precipitation were loaded onto a Synergi-Hydro column (25-×4.6 mm, Phenomenex, Torrance CA) equilibrated with 25 mM phosphate buffer containing 1.4 mM 1-octanesulfonic acid, 6% v/v acetonitrile, pH 2.6 and eluted at a flow of 0.5 ml/min. The system consisted of an ESA automated injection system, an ESA 582 pump, and amperometric cell (5040) with a BDD working electrode operating at an applied voltage of 1500 mV [29]. GSH and GSSG standards were used for quantification and concentrations were normalized to protein content.

Quantification of neurotransmitters using HPLC with electrochemical detection

Left ventricular tissue was homogenized in 0.1 N hydrochloric acid and centrifuged at 22382 × g for 10 min. An aliquot of the supernatant was removed for protein assay and the remaining was incubated with 0.1 M perchloric acid for 30 min on ice following centrifugation at 30113 × g for 15 min. Neurotransmitters in the clarified supernatant were measured by HPLC with electrochemical detection using an analytical column synergy Polar RP (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA, 4.6 × 250.0 mm) eluted with 0.075 M sodium dihydrogenphosphate, 0.75 mM triethylamine, 1.5 mM sodium octanesulfonate, 10% acetonitrile pH 3.0 at flow rate of 1.0 mL/min [30]. The system consisted of an ESA automated injection system, an ESA 582 pump, 4-sensor cell operating at an applied potential of 0, 220, 300 and 350 mV and controlled by CoulArray detector (ESA, Chelmsford, MA, USA). Dopamine, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid, homovanillic acid (HVA), serotonin (5-HT), norepinephrine, epinephrine (10–100 ng/mL) were used as standards. Contents of neurotransmitters were calculated as ng/mg protein.

Cardiac mitochondria isolation

Hearts from 12-week, and 12-month old mice were processed immediately after excision for mitochondrial isolation at 4°C. Mitochondria isolation was performed using standard differential centrifugation techniques. Briefly, heart tissue was collected and homogenized in mitochondria isolation buffer: 70 mM Sucrose, 210 mM mannitol, 5 mM HEPES, 1 mM EGTA and 0.5% fatty acid-free BSA, pH 7.2. Homogenates were centrifuged at 700 × g for 10 min at 4°C (Sorvall High speed, SA600 rotor). The supernatant was transferred to a cold, clean tube (Nalgene) and subjected to a high-speed centrifugation (10,000 × g, 10 min, 4°C). The final supernatant was discarded and the mitochondrial pellet washed twice with the isolation buffer. Finally, the pellets were resuspended in mitochondria assay buffer: 70 mM Sucrose, 220 mM mannitol, 10 mM KH2PO4, 5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM HEPES, 1 mM EGTA and 0.2% fatty acid-free BSA, pH 7.2 [31]. Mitochondrial preparation was used immediately for respiration measurements or stored at −80°C for immunoblot.

Mitochondrial respiration measurements using XF96 Analyzer

Respiration was carried out in isolated mitochondria using Extracellular Flux Analyzer (XF) 96 well format (Seahorse Bioscience, North Billerica, MA). Isolated mitochondria (3 μg in 140 μl of assay buffer) in the presence of substrates (5 mM glutamate and 5 mM malate) were loaded onto a 96 well polystyrene microplate and transferred to a centrifuge equipped with a swinging bucket microplate adaptor and spun at 2000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Following centrifugation, the plates were warmed at 37°C for 10 mins and transferred to the XF 96 analyzer [32]. Respiration was initially measured in basal conditions (State 2). State 3 respiration was initiated by injected ADP (1 mM); oligomycin- induced state 4 was carried out by injecting oligomycin (2.5 μg/ml); uncoupled state 3 respiration after the addition of FCCP (0.75 μM) and mitochondrial respiration was inhibited following the addition of antimycin (4 μM) respectively. Oxygen consumption rate (OCR) was measured using mix/measure/mix time cycle of 0.5 min/3 min/1 min, respectively.

Low-temperature electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) analysis of mitochondrial protein complexes and iron-nitrosyl content in cardiac tissue

Freshly-excised hearts were quickly loaded on a 4 mm quartz EPR tubes (Wilmad Glass, Buena, NJ, U.S.A.) and samples snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. Samples were analyzed using a X-band EPR spectrometer Bruker E500 ELEXYS with 100 kHz field modulation, equipped with an Oxford Instrument ESR-9 helium flow cryostat and a DM-0101 cavity. Spectrometer conditions were as follows: microwave frequency, 9.635 GHz; modulation frequency, 100 kHz; modulation amplitude, 10 G; receiver gain, 85 dB; time constant, 0.01 s; conversion time, 0.08 s; and sweep time, 83.9 s. EPR spectra were obtained over the temperature range 12–40°K using an incident microwave power of 0.25 mW and 5 mW, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Results are reported as mean ± S.E.M. Comparisons between two groups were performed with paired Student’s t tests. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Profiling of BH4 changes in mice hearts over-expressing GTPCH

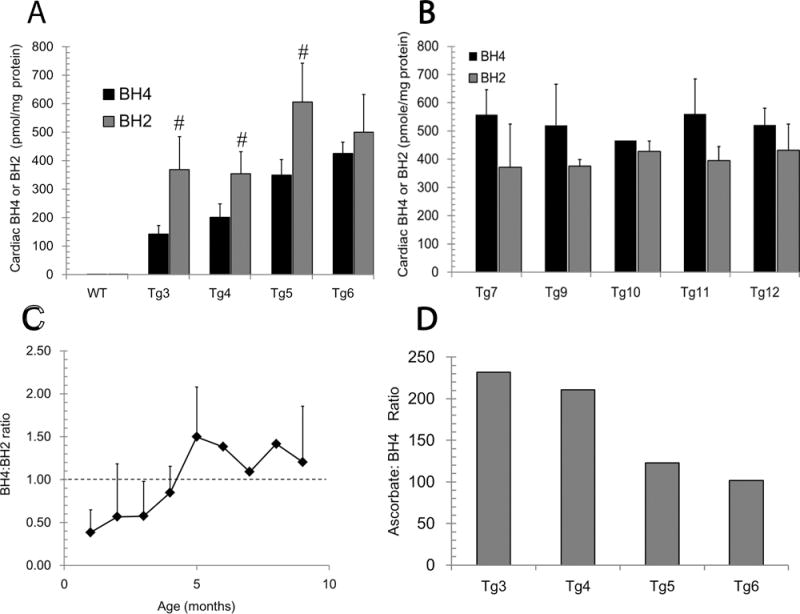

Enhanced GTPCH activity in transgenic hearts (mGCH) was previously shown by specific detection of high GTPCH protein expression and increased BH4 levels that were several-fold higher than those detected in hearts from wild type mice [22]. To assess the persistence of this increase, we analyzed BH4 in left ventricle (LV) in hearts from normal growing mGCH at different ages and compared these changes with those found in hearts from age-matched, wild type animals. In wild type C57Bl6 hearts, non-significant variations in BH4 were registered with age with an average concentration of 5.35±1.88 pmol/mg protein (n=15). In the transgenic hearts, a continuous normalized increase in BH4 concentration was detected between 2–6 months of age (Fig. 1A). This rise continued until about 6 months of age. After this period, BH4 concentrations reached a steady state as verified between 7–12 months old (Fig. 1B). Variable concentrations of the oxidized metabolite 7,8-dihydrobiopterin (BH2) levels were also found. A greater accumulation of BH2 than BH4 in hearts <6 month age than >6 months was demonstrated (Fig 1A–B). The calculated fluctuation of BH4:BH2 ratio with age indicated that effective accumulation of BH2 is more prominent in the young hearts (Fig 1C). Cardiac tissue is rich in reduced ascorbate (AH−), and it is concomitantly detected with BH4 and BH2 during HPLC analysis. The quantification of AH− levels in the heart from transgenic mice showed that AH− concentration declined with age (32.9±12 to 20.1±5.1 nmol/mg protein), yet it remained in an excess of ~100 fold with respect to BH4 (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1. Cardiac 6R-tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4), 7,8-dihydrobiopterin (BH2) and ascorbate HPLC-ECD analysis in cardiomyocyte-specific transgenic (Tg) hearts overexpressing GTPCH (mGCH).

(A and B) Quantification of BH4, 7,8-dihydropterin (BH2) in left ventricular tissue of increasing age. (C) Calculated ratio of BH4 to BH2 in left ventricular heart tissue from hearts at different ages. (D) Ratio of reduced ascorbate to BH4 in left ventricular tissue form mGCH animals. Assays of BH4, BH2 and ascorbate were performed by HPLC-ECD as described in methods. WT, indicate cardiac tissue from C57Bl6 mice hearts. All concentrations were normalized to protein content and results are presented as mean±S.D (n>5) samples per group. (#,**)p<0.05.

GTPH activity in transgenic hearts

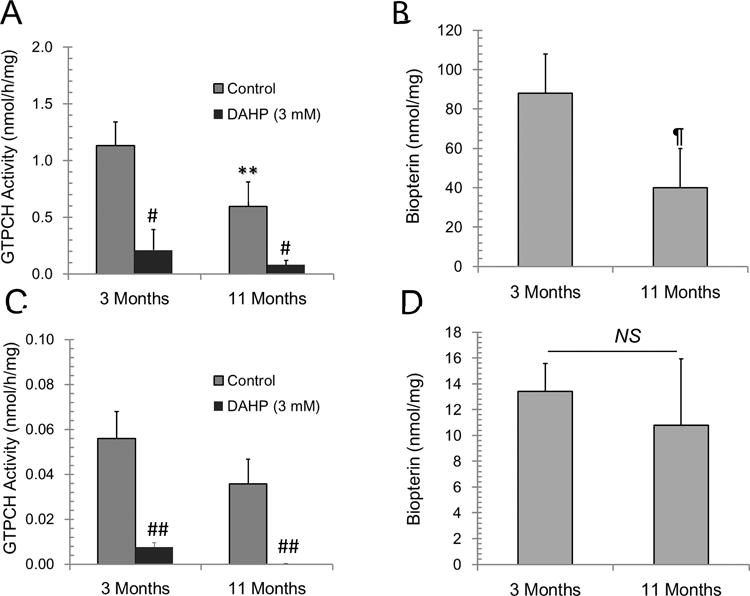

To better understand the relationship between changes in GTPCH enzyme activity and BH4 levels with age, direct activity assay measuring the GTP conversion to 7,8-dihydroneopterin was performed. It was shown that GTPCH activity in 3-month old mouse hearts was higher than enzyme activity detected in 11-month-old transgenic mouse hearts. GTPCH activity in 3- and 11-month old hearts was sensitive to inhibition by DAHP, a GTPCH inhibitor (Fig. 2A). Biopterin, the final degradation product of BH4 accumulated in cardiac tissue was also decreased in 11-month compared to 3-month heart tissue (Fig. 2B). This change in enzyme activity corresponds with a decrease in GTPCH protein expression levels in the heart (Suppl. Fig. 1). The age-dependent decrease in GTPCH activity was specific to heart tissue, as compared to the liver. The GTCPH activity in the liver (Fig. 2C) was ~20-fold lower than hearts. This difference was also mirrored by the low level of biopterin in liver relative to those found in the heart. (Fig. 2D). In the liver however, GTPCH enzyme activity in 3-month and 11-month old mice was not significantly different. Together these data indicated that early variations in cardiac BH4 levels are not explained by deficient GTPCH activity in transgenic heart and that a decreased GTPCH activity with age is not directly mirrored in in BH4:BH2 ratio changes.

Figure 2. GTP cyclohydrolase (GTPCH) activity in transgenic hearts and liver.

Enzyme activity was measured in tissue homogenates (A) heart (C) liver by analyzing the rate of hydrolysis of GTP to 7,8-dihydroneopterin phosphate as described in methods. The oxidation product neopterin was quantified by HPLC with fluorescence detection. Biopterin, the BH4 and BH2 metabolite in tissue homogenates (B) heart and (D) liver was directly measured by analyzing supernatant of tissue homogenates clarified by filtration. All values were normalized by protein content in tissue homogenates. Results are presented as mean±SD (n=4). (**, ¶) p<0.05, (#, ##)p<0.02.

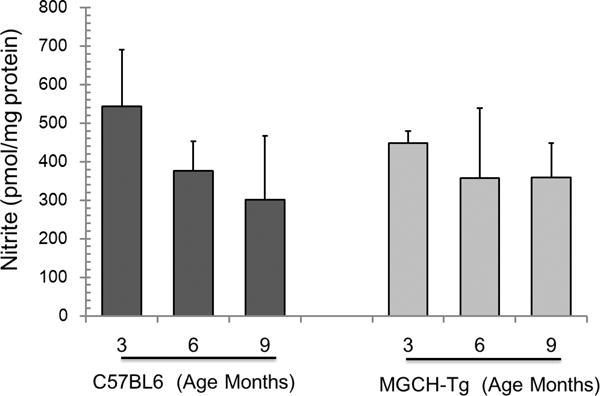

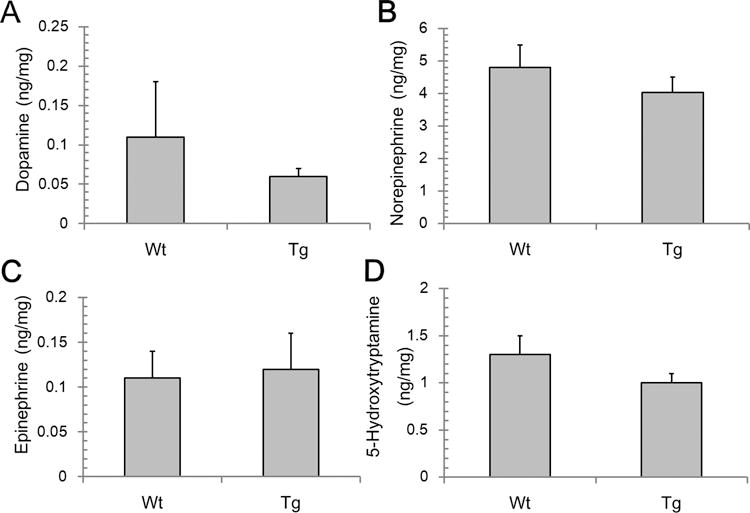

High cardiac BH4 does no increase cardiac NOx levels nor neurotransmitters production

To establish the functional significance of changes in BH4:BH2 content in GTPCH-overexpressing cardiomyocytes, we verified enzyme activity of enzymes requiring BH4 as cofactor. Specifically NO metabolites and neurotransmitters were analyzed as products of these enzyme pathways. It was found that neither wild type nor GTPCH transgenic hearts have significant changes in NO metabolites and that concentrations are very similar between these two groups (Fig. 3). Cardiac neurotransmitters were also unaltered by increased GTPCH expression and activity (Figure 4B–D). This indicated that changes in the BH4:BH2 ratio due to specific GTPCH overexpression in the cardiomyocytes does not alter neurochemical inputs in the heart.

Figure 3. Nitrite analysis in cardiac tissue from C57Bl6 hearts (wild type) and cardiomyocyte targeted GTPCH transgenic hearts (mGCH).

Samples from cardiac tissue were analyzed using nitric oxide analyzer (NOA) with chemiluminescence detection. Results represent the mean±SD (n=6). No differences were established.

Figure 4. Neurotransmitter levels in cardiac issue of C57Bl6 hearts (wild type) and cardiomyocyte targeted GTPCH transgenic hearts (mGCH).

HPLC-ECD analysis of dopamine, norepinephrine, epinephrine and 5-hydroxytryptamine in cardiac tissue were analyzed as described in materials and methods. Results are expressed as mean±S.D. (n=4). No differences were established.

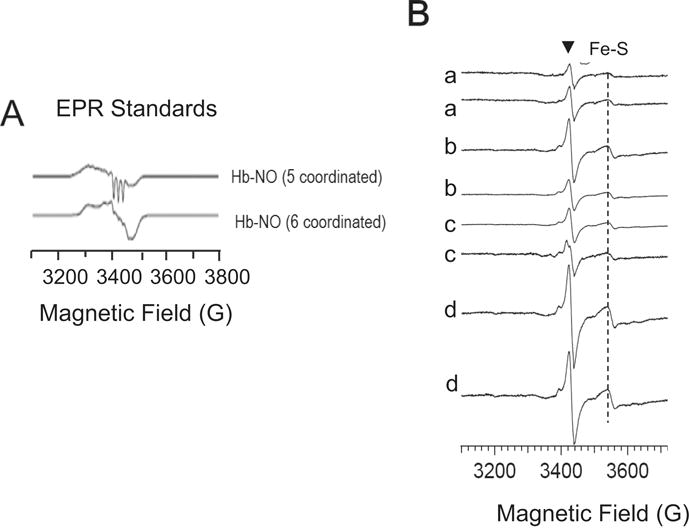

EPR analysis of NO-surrogate markers in GTPCH overexpressing hearts

As cardiac NOx content is susceptible to influence of dietary and other physiological factors that can mask changes in NO production as measured by NOx levels, wild type and GTPCH transgenic hearts were examined at low-temperature EPR for the presence of endogenous markers of increased production of NO. Specifically, changes in nitrosyl heme and mitochondrial aconitase (g~2.02) and dinitrosyl-iron-dithiol complex (g~2.04) were investigated [33–35]. Low-helium temperature (40°K) EPR analysis of standard samples of nitrosyl-heme hemoglobin-NO complexes shows two species due to Fe-NO complex of heme-iron in the 5 coordinated and 6 coordinated state respectively (Fig. 5A) [33, 34]. The 5-coordinated Hb-NO complex shows rhombic EPR signal with a characteristic triplet signal at g~2.014 due to porphyrin (Fe)-NO. The spectrum of the 6-coordinated form of porphyrin(Fe)-NO species is dominated by rhombic signal and it is one of the complexes detected in cardiac tissue with relatively low NO fluxes. We analyzed freshly excised tissue that was snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and found no evidences for porphyrin (Fe)-NO in any of the tissue analyzed (Fig. 5B). The samples analyzed were from transgenic mice of 2 (a), 4 (b) and 6 (c) months of age and tissue from 3 months of age wild type (d). The main signal in the recorded spectra at 40°K is consistent with the presence of ubisemiquinone radical at g~2 and iron-sulfur (Fe-S) complex g~1.94 which are characteristic EPR signal found in heart samples. No consistent differences in the region g~2.04 were detected.

Figure 5. Low-temperature EPR analysis (40°K) of cardiac tissue form C57Bl6 hearts (wild type) and cardiomyocyte targeted GTPCH transgenic hearts (mGCH).

(A) Standard samples of 5- and 6-coordinated complexes of hemoglobin(Fe-NO). (B) mGCH and wild type cardiac samples: a) mGCH- 4 months; b) mGCH-6 months; c) mGCH-2 months; d) C57Bl6-12 months. Single samples were inserted in quartz EPR tubes and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen as soon as isolated. Instrument setting are as described in methods. (▼) ubiquinone radical; (Fe-S) mitochondrial 2FeS2 centers.

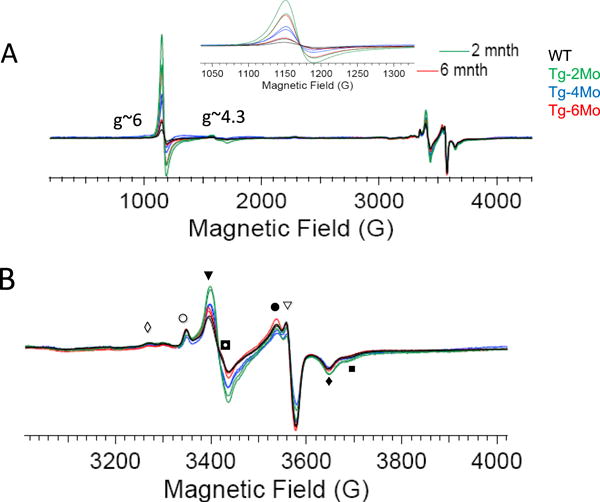

At temperatures of 12°K the EPR analysis of same tissue samples analyzed before showed a low-magnetic field signal at g~6.0 due to high spin (HS) (S=5/2) porphyrin-Fe(III) species (Fig. 6) [36]. The signal intensity of this species changed with age with a high intensity in hearts from 2-month old mice and decreased in samples from older mice. In wild type control samples, the ferric HS signal was also present but at a lower intensity. A low intensity signal in the region g~4.3 (ferric iron) [37] was common to all samples. Multicomponent EPR signals in the g~2 region were also discernible. The signals detected at g~2 are typical of iron-protein containing mitochondrial clusters for complex I, II and III showing equivalent contribution to the EPR spectra. The detected variations in porphyrin-(FeIII) (HS) content in the transgenic hearts however suggests that oxidation-reduction reactions occur in <6 month old tissue samples which may explain variations in the BH4/BH2 in this age-group.

Figure 6. Low-temperature EPR analysis (12°K) of cardiac tissue from C57Bl6 hearts (wild type) and GTPCH transgenic cardiomyocyt.

e. (A) Wide field EPR scanning of wild type and mGCH-samples (ages: 2,4, and 6 month) revealed a high spin Fe(III)-porphyrin signal g~6 that shows a higher intensity in young transgenic than wild type hearts (inset: zoom of g~6 signal) (B) EPR signal of cardiac mitochondrial complexes showing non-significant variations between transgenic than wild type tissue. EPR spectra display the sum of the various redox centers of protein complexes such as: (◊) cI-N4 4Fe4S, (○) cI-N2 4Fe4S, (▼) aconitase 3Fe4S, cI-N1b 2Fe2S, cII-S1 2Fe2S, cII-S3 3Fe4S, (◘) ubiquinone radical, (●) cI-N1b 2Fe2S, cII-S1 2Fe2S, (◘) cII-S1 2Fe2S, cI-N1b 2Fe2S, (◊)cI-N4 4Fe4S, Rieske 2Fe2S, (■) cI-N3 4Fe4S.

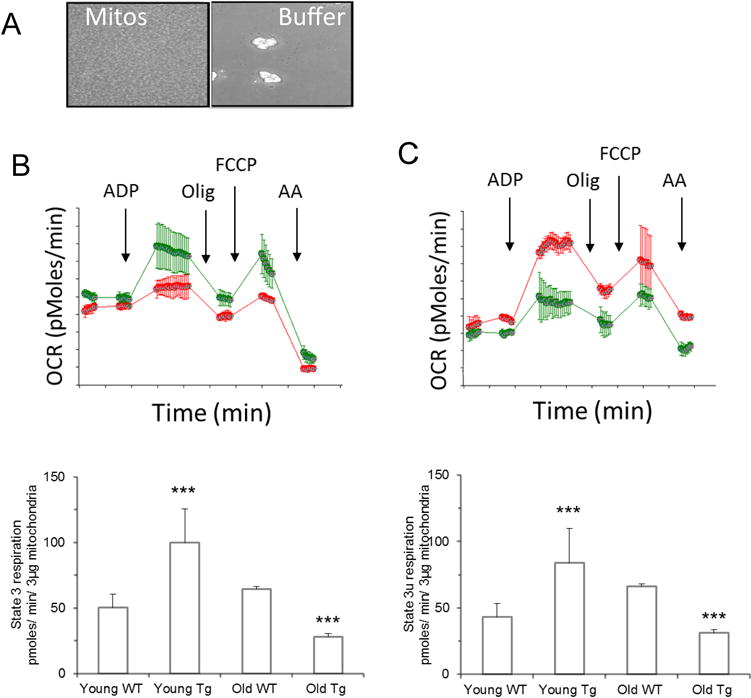

Effects of increased cardiomyocyte BH4 on mitochondrial levels and function

Altered BH4:BH2 content has been associated with changes in oxidant production in cardiac diseases such as heart failure, myocardial hypertrophy. Increased oxidant levels may contribute to changes in mitochondrial function. To investigate changes in mitochondrial functional states mGTPCH hearts, oxygen consumption rates (OCR) were measured in isolated mitochondria from 3- and 12month old GTPCH transgenic mice. The assays were performed simultaneously with freshly isolated mitochondria using a high-throughput XF-assay as described in Methods. The optimized mitochondrial protein loading on the experimental well (Fig 7A) was adjusted to reach State 2 OCR ~100 pmol/min per well. State 3 respiration was stimulated by addition of ADP, and maximal respiration rates were stimulated with mitochondrial uncoupler, FCCP. Mitochondrial preparations obtained from 3 month animals showed a higher ADP-stimulated respiration rate compared to mitochondria isolated from wild type animals (C57Bl6). In contrast, cardiac mitochondrial preparations from 12 month old GTPCH transgenic animals showed a significant slower State-2 respiration rate compared to C57Bl6 (Fig. 7B). The same relationships were determined for uncoupled mitochondrial OCR, mitochondrial from 3-month old mouse hearts showing a better performance than wild type but a lower performance at 12 months of age. The decreased rate of respiration in mitochondria of 12-month old mouse hearts is unlikely explained by variation in respiratory complexes content since the amount of mitochondrial complexes as shown in low-temperature EPR analysis remain at comparable levels. Also, EPR data and NOx data do not support the notion of increased NO as a mediator of the observed decline in respiration rates.

Figure 7. Bioenergetics characterization of isolated cardiac mitochondria from C57Bl6 (WT) and cardiomyocyte-targeted GTPCH transgenic hearts (Tg).

(A) Isolated mitochondria (3 μg) attached to the 96 well plate (Seahorse) used for analysis; (B) Mitochondrial oxygen consumption of 3-month old WT-mitochondria (red traces), MGCH-Tg (green traces) before (State 2) or after stimulation state-3 respiration with ADP (1 mM), and followed by inhibition of ATP-dependent oxygen consumption with complex V inhibitor oligomycin (2.5 μg/ml). Maximal oxygen consumption capacity was assessed by addition of mitochondrial uncoupler FCCP (0.75 μM) (state 3 uncoupled) and complete inhibition of oxygen consumption was tested with antimycin A (4 μM), (lower panel); (C) as B but mitochondria were isolated from 12-month old mice. (D) Quantification of State 3 respiration stimulated by ADP in mitochondria from wild type and Tg hearts 3-months and 12-moths old; (E) same as D except the state 3 uncoupled stimulated by FCCP. Results are represented as mean±S.D of triplicate experiments. (***) p<0.05.

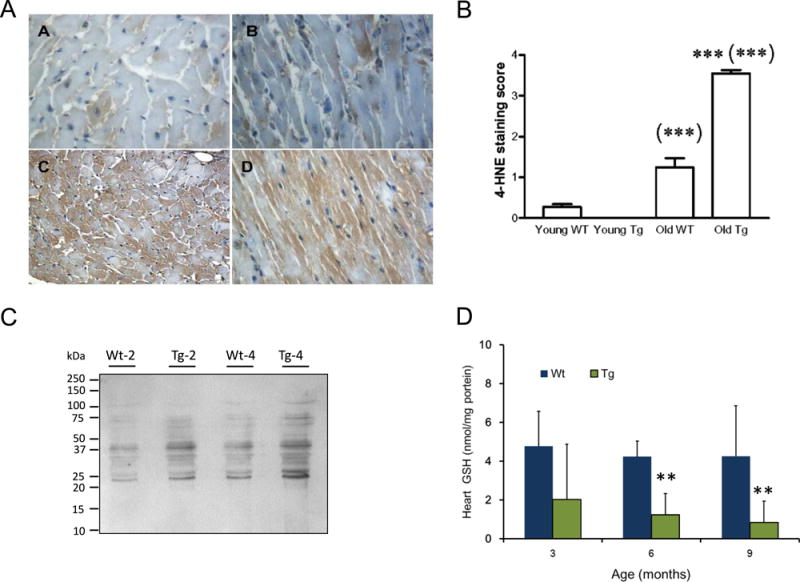

Mitochondrial respiration is sensitive to oxidant and electrophile molecules [38,39]. In cardiomyocytes, mitochondria appear to be a preferred target of lipid electrophiles. Whether cardiomyocytes with increased GTPCH activity exhibit high levels of 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) was examined by immunotechniques. As shown in the Fig 8 immunohistological analysis of left ventricular cardiac tissue demonstrated that 4-HNE-staining is low in both young (~2month) wild type and GTPCH transgenic mice while hearts from old (>10month) mGTPCH showed a significant higher staining score (Fig 8B). Also increased 4-HNE specifically associated with mitochondrial protein fraction was found in isolated mitochondria from mGCH hearts but not wild type (C57BL6) as young as 3 months of age. Collectively, these data indicated that increased GTPCH activity in cardiomyocytes increases 4-HNE which via post-translational modification of mitochondrial proteins could reduce mitochondrial function with age. Analysis of the left ventricular tissue by HPLC demonstrated that GTPCH transgenic hearts have a significant lower amount of reduced glutathione (Fig 8D) and a decreased cytosolic aconitase activity (Table I, Supplement) indicating that supra-physiological BH4 levels in the heart promote oxidant damage.

Figure 8. Accumulation of reactive lipid species and reduced glutathione depletion in GTPCH transgenic hearts.

(A) Low levels of positive staining for 4-HNE in cardiomyocytes of young wild type and GTPCH transgenic hearts (Top panels A–B); 4-HNE positive staining is higher in old GTPCH transgenic than wild type hearts (Bottom panels C–D); (B) Analysis of 4-HNE immunostaining score in wild type (WT) young (3 months) and old (12 months) and age-matched GTPCH transgenic (Tg) hearts; results are representative of at least 3 different samples. (***) p˂0.05 and (***(***) p<0.01. (C) western blotting of 4-HNE-modified proteins from isolated mitochondria from 2-month old and 4-month old hearts; (D) cardiac levels of reduced glutathione in C57Bl6 (wild type, WT) and GTPCH transgenic (Tg) hearts analyzed directly by HPLC-ECD. Results are the mean±S.D (n=3 each group age); (**) p<0.05.

Discussion

The major findings in this study are that targeted expression of GTPCH in cardiomyocytes results in a bi-phasic variation of BH4:BH2 ratios instigating an overall worsening of cardiac myocyte redox status and impaired mitochondrial respiratory capacity with age. In our previous studies, we found a significant increase in BH4 and its metabolites in the heart, reaching a total of about 100-fold higher levels than those found in wild type heart. This accumulation did not alter plasma biopterin levels [22] and, as shown in this study, it did not alter endogenous liver concentrations either indicating that increased GTPCH expression resulting in increased levels of BH4 has tissue-specific activity. Here we confirmed that increasing cardiomyocyte GTPCH results in an incremental accumulation in both BH4 and BH2 in the heart. Similar results have been recently described for a newly generated cardiac GTPCH transgenic mouse model that expresses a lower level of GTPCH activity [40]. Thus, increased BH2 conversion is likely regulated by endogenous factors rather than by only GTPCH activity levels.

We showed that the variation in cardiomyocyte BH4 concentrations with age is inversely related to GTPCH enzyme activity. Taking into account that both BH4 and BH2 accumulated in the tissue, it appears that an effective cardiac surge of the total level (BH4+BH2) occurs at about 4 month of age to reach steady state level thereafter. The accumulation of BH2 in the cardiomyocyte was understandable since adult cardiomyocytes, unlike neonatal or embryonic cardiomyocytes, are deficient in DHFR [16], the enzyme that catalyzes the reduction of BH2 to BH4 at the expenses of NADPH. The fact that a more prominent accumulation of BH2 with respect to BH4 is found in young (e.g. 3-months) hearts than older hearts (11-months), suggests that an effective BH2 distribution to other cells with DHFR activity occurs when high intracellular BH2 concentrations in the cardiomyocyte have been reached. The consequences of enhanced distribution of BH2 to other cells types is that BH2 is reduced back to BH4 in those non-cardiomyocyte cells. One possible cell recipient of BH2 is endothelial cell which can reduce BH2 back to BH4 when large intracellular BH2 gradients are established [40–42]. This cellular effect may explain the paradoxical increase in BH4 in older hearts compared to young hearts. In older (11 month) mice a decreased cardiac GTPCH activity was found but it is in this period that BH4 is elevated compared to hearts of younger (<6 months) mice.

While biopterin levels do not support the idea that BH4 or BH2 permeates to plasma, these measures cannot discriminate between cell to cell interactions. We have shown that BH2 uptake by endothelial cells is a slow process and that conversion of BH2 to BH4 is effective when threshold concentrations have been reached [15]. Thus while this process may occur in young hearts, the distribution of BH2 in other cells is more probable to be more noticeable in old hearts that have accumulated large amounts of BH2. As a consequence of this process an effective change in BH4-to-BH2 ratios are established. Others studies using newly generated cardiomyocyte-specific GTPCH transgenic hearts showed that significant increase (p<0.01) in non-myocyte fraction of cells from cardiomyocyte GTPCH transgenic mice was found, although the most prominent accumulation of BH4 is seen in LV myocytes (40). These transgenic hearts expressed a lower level of GTPCH, BH4 and BH2 which will attenuate this process.

An intriguing aspect of this study is the demonstration that increased BH4 production in normal and healthy hearts is followed by increased accumulation of BH2 even in very young hearts. The most accepted mechanisms for the conversion of BH4 to BH2 are associated with increased levels of reactive species that react with BH4 to generate BH2 and/or changes in redox environment that decrease GTPCH activity and BH4 production [43–45]. An oxidative mechanism however cannot fully explain the early changes in BH2 level as the chronic (genetic) increase in BH4 is expected to completely inhibit NOS-dependent superoxide production and therefore decreasing oxidant-mediated BH4 oxidation. Also the highest ascorbate to BH4 ratio was found in young hearts. Although at a later time, a low ratio BH4-to-BH2 will most likely enhance superoxide production from eNOS by an uncoupling mechanism (46) which will accelerate the oxidation of BH4, the early mechanism explaining an increased BH2 production is not totally clear.

One possible explanation for the increased oxidation of BH4 in young transgenic hearts could be linked to the facilitated oxidation of unbound protein-free BH4 that could increase superoxide concomitantly to eNOS-BH4 increasing NO production, and thereby producing peroxynitrite. Our studies trying to discern if NO production was increased in the transgenic hearts, however did not show directed evidence that this is the case. The EPR data suggests however the possibility that some increase in NO is initially reached, but rapidly inactivated through the reaction with oxymyoglobin (MbO2) to generate methemyoglobin and nitrate (k~5×107M−1s−1) (47). There is also the possibility that peroxynitrite itself increases methemoglobin and nitrate levels upon reaction with MbO2. EPR analysis showed an marked increase in high spin porphyrin-Fe(III) signal (g~6) in the young transgenic hearts which indicates formation of metmyoglobin; changes in nitrate levels are difficult to establish as nitrite background level is already very high in heart tissue. A role for peroxynitrite as the oxidant species increasing BH2, is unlikely since the g~6 signal decreases while BH2 continues to accumulate with age.

An NO-independent mechanism that may explain the accelerated oxidation of BH4 in cardiomyocytes is via autoxidation reaction of BH4 generating superoxide which in the dismutation reaction generates hydrogen peroxide and via reaction with Fe(III)-porphyrins. The reaction of BH4 as one-electron donors to Fe(III) porphyrins has been established on the basis of kinetic data analysis [48]. The rates of BH4 oxidation was shown to be a function of the redox potential of the protein with ferricytochrome c (Em=260mV) being more favorable than other haemoproteins like catalase or horseradish peroxidase, which have a very low redox potential [48]. From these studies and relevant to cardiac cells, the reaction of BH4 with metmyoglobin (Em~ 50mV) [49] is also predicted to be much less favorable than hemoglobin and ferricytochrome c. The reaction of BH4 with ferric-proteins like cytochrome c will form the one-electron oxidation product of BH4 (BH4-free radical) and the ferrous-protein. In solution i.e. protein-free BH4 radical at physiological pH levels will be found as deprotonated carbon-centered radical •BH4; pKa 5.2±0.1 [50]. The C4a electron rich carbon–centered BH4 radical rapidly reacts with oxygen to generate superoxide radical anion and/or BH4 peroxyl radical (BH4OO•), which could oxidize another BH4 in the propagation reaction [51], with the generation of BH4-hydroperoxide intermediate [52]. The decomposition of the BH4-hydroperoxide generates BH2 and hydrogen peroxide [52,53]. The consequences of this mechanism are very significant. It indicates that in cardiomyocytes cells that are rich in cytochrome c, BH4 itself can be a driver of increased H2O2 formation through an accelerated oxidation of the unbound cofactor.

The process considered above would explain the initial accelerated BH4 oxidation and BH2 formation in the heart of otherwise normal healthy animals. Following this event, it is possible to envision that the competition between BH4 and BH2 for the eNOS pterin-binding site will result in the uncoupling of L-arginine and NADPH oxidation catalyzed by eNOS, and increasing superoxide release from eNOS [46]. Through this mechanism the accumulation of BH2 will mediate oxidative injury and may explain the observed changes in oxidative markers lipid peroxidation resulting in the formation of 4-HNE, loss of cytosolic aconitase activity and the observed GSH depletion. Importantly, these changes are paralleled by an accelerated loss of mitochondrial function in older hearts indicating the significance of the accumulated oxidant damage.

Taken together our results indicate that paradoxically, increasing BH4 content in cardiomyocyte resulted in mitochondrial loss of function that is not associated with high NO fluxes but with changes in cardiomyocyte redox status. These redox-modifications are aggravated with age as NOS-uncoupling will be favored due to a greater accumulation of BH2 than BH4 in cardiomyocytes. Whether lack of benefits observed in short term oral treatment with high BH4 can be explained by similar mechanisms seems unlikely since BH4 levels reached in the heart are significantly lower than BH4 produced from GTPCH over-expression in cardiomyocytes, and more information would be necessary to better understand the mechanisms of cytotoxicity in supplementation. In conclusion, the present study indicates that a better understanding of the cellular factors affecting the stability of BH4 in different cellular milieu is essential to design better strategies to deliver BH4 and successfully adopt its use in the clinic

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Cardiomyocyte specific GTP-cyclohydrolase expression increase heart’s BH4 and BH2 levels.

GTP cyclohydrolase transgenic hearts fail to demonstrate sustained increase NO production.

Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidation markers follow high cardiomyocyte BH4 production.

Increasing BH4 in cardiomyocytes do not alleviate but actually promotes oxidant injury.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Redox Biology Program at the Medical College of Wisconsin.

References

- 1.Kwon NS, Nathan CF, Stuehr DJ. Reduced biopterin as a cofactor in the generation of nitrogen oxides by murine macrophages. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:20496–20501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mayer B, John M, Heinzel B, Werner ER, Wachter H, Schultz G, Böhme E. Brain nitric oxide synthase is a biopterin- and flavin-containing multi-functional oxido-reductase. FEBS Lett. 1991;288:187–191. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)81031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gross SS, Jaffe EA, Levi R, Kilbourn RG. Cytokine-activated endothelial cells express an isotype of nitric oxide synthase which is tetrahydrobiopterin-dependent, calmodulin-independent and inhibited by arginine analogs with a rank-order of potency characteristic of activated macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;178:823–829. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)90965-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carnicer R, Crabtree MJ, Sivakumaran V, Casadei B, Kass DA. Nitric oxide synthases in heart failure. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;18:1078–1099. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jeong EM, Liu M, Sturdy M, Gao G, Varghese ST, Sovari AA, Dudley SC., Jr Metabolic stress, reactive oxygen species, and arrhythmia. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012;52:454–463. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hammond J, Balligand JL. Nitric oxide synthase and cyclic GMP signaling in cardiac myocytes: from contractility to remodeling. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012;52:330–340. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elrod JW, Calvert JW, Gundewar S, Bryan NS, Lefer DJ. Nitric oxide promotes distant organ protection: evidence for an endocrine role of nitric oxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:11430–11435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800700105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prime TA, Blaikie FH, Evans C, Nadtochiy SM, James AM, Dahm CC, Vitturi DA, Patel RP, Hiley CR, Abakumova I, Requejo R, Chouchani ET, Hurd TR, Garvey JF, Taylor CT, Brookes PS, Smith RA, Murphy MP. A mitochondria-targeted S-nitrosothiol modulates respiration, nitrosates thiols, and protects against ischemia-reperfusion injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:10764–10769. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903250106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Totzeck M, Hendgen-Cotta UB, Luedike P, Berenbrink M, Klare JP, Steinhoff HJ, Semmler D, Shiva S, Williams D, Kipar A, Gladwin MT, Schrader J, Kelm M, Cossins AR, Rassaf T. Nitrite regulates hypoxic vasodilation via myoglobin-dependent nitric oxide generation. Circulation. 2012;126:325–334. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.087155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vásquez-Vivar J, Kalyanaraman B, Martásek P, Hogg N, Masters BS, Karoui H, Tordo P, Pritchard KA., Jr Superoxide generation by endothelial nitric oxide synthase: the influence of cofactors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9220–9225. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takimoto E, Champion HC, Li M, Ren S, Rodriguez ER, Tavazzi B, Lazzarino G, Paolocci N, Gabrielson KL, Wang Y, Kass DA. Oxidant stress from nitric oxide synthase-3 uncoupling stimulates cardiac pathologic remodeling from chronic pressure load. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1221–1231. doi: 10.1172/JCI21968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Werner-Felmayer G, Werner ER, Fuchs D, Hausen A, Reibnegger G, Schmidt K, Weiss G, Wachter H. Pteridine biosynthesis in human endothelial cells. Impact on nitric oxide-mediated formation of cyclic GMP. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:1842–1846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Werner ER, Blau N, Thöny B. Tetrahydrobiopterin: biochemistry and pathophysiology. Biochem J. 2011;438:397–414. doi: 10.1042/BJ20110293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu F, Sudo Y, Sanechika S, Yamashita J, Shimaguchi S, Honda S, Sumi-Ichinose C, Mori-Kojima M, Nakata R, Furuta T, Sakurai M, Sugimoto M, Soga T, Kondo K, Ichinose H. Disturbed biopterin and folate metabolism in the Qdpr-deficient mouse. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:3924–3931. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whitsett J, Rangel Filho A, Sethumadhavan S, Celinska J, Widlansky M, Vasquez-Vivar J. Human endothelial dihydrofolate reductase low activity limits vascular tetrahydrobiopterin recycling. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;63:143–150. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.04.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ionova IA, Vásquez-Vivar J, Whitsett J, Herrnreiter A, Medhora M, Cooley BC, Pieper GM. Deficient BH4 production via de novo and salvage pathways regulates NO responses to cytokines in adult cardiac myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H2178–H2187. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00748.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kasai K1, Hattori Y, Banba N, Hattori S, Motohashi S, Shimoda S, Nakanishi N, Gross SS. Induction of tetrahydrobiopterin synthesis in rat cardiac myocytes: impact on cytokine-induced NO generation. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:H665–H672. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.2.H665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hattori Y, Hattori S, Motohashi S, Kasai K, Shimoda SI, Nakanishi N. Co-induction of nitric oxide and tetrahydrobiopterin synthesis in the myocardium in vivo. Mol Cell Biochem. 1997;166:177–181. doi: 10.1023/a:1006875707028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vásquez-Vivar J, Whitsett J, Ionova I, Konorev E, Zielonka J, Kalyanaraman B, Shi Y, Pieper GM. Cytokines and lipopolysaccharides induce inducible nitric oxide synthase but not enzyme activity in adult rat cardiomyocytes. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45:994–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaczorowski DJ, Nakao A, McCurry KR, Billiar TR. Toll-like receptors and myocardial ischemia/reperfusion, inflammation, and injury. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2009;5:196–202. doi: 10.2174/157340309788970405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo Y, Sanganalmath SK, Wu W, Zhu X, Huang Y, Tan W, Ildstad ST, Li Q, Bolli R. Identification of inducible nitric oxide synthase in peripheral blood cells as a mediator of myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Basic Res Cardiol. 2012;107:253–261. doi: 10.1007/s00395-012-0253-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ionova IA, Vásquez-Vivar J, Cooley BC, Khanna AK, Whitsett J, Herrnreiter A, Migrino RQ, Ge ZD, Regner KR, Channon KM, Alp NJ, Pieper GM. Cardiac myocyte-specific overexpression of human GTP cyclohydrolase I protects against acute cardiac allograft rejection. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;299:H88–H96. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00203.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ge ZD, Ionova IA, Vladic N, Pravdic D, Hirata N, Vásquez-Vivar J, Pratt PF, Jr, Warltier DC, Pieper GM, Kersten JR. Cardiac-specific overexpression of GTP cyclohydrolase 1 restores ischaemic preconditioning during hyperglycaemia. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;91:340–349. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moens AL, Takimoto E, Tocchetti CG, Chakir K, Bedja D, Cormaci G, Ketner EA, Majmudar M, Gabrielson K, Halushka MK, Mitchell JB, Biswal S, Channon KM, Wolin MS, Alp NJ, Paolocci N, Champion HC, Kass DA. Reversal of cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis from pressure overload by tetrahydrobiopterin: efficacy of recoupling nitric oxide synthase as a therapeutic strategy. Circulation. 2008;117:2626–2636. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.737031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moens AL, Ketner EA, Takimoto E, Schmidt TS, O’Neill CA, Wolin MS, Alp NJ, Channon KM, Kass DA. Bi-modal dose-dependent cardiac response to tetrahydrobiopterin in pressure-overload induced hypertrophy and heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;51:564–569. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whitsett J, Picklo MJ, Sr, Vasquez-Vivar J. 4-Hydroxy-2-nonenal increases superoxide anion radical in endothelial cells via stimulated GTP cyclohydrolase proteasomal degradation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:2340–2347. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.153742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nar H, Huber R, Auerbach G, Fischer M, Hösl C, Ritz H, Bracher A, Meining W, Eberhardt S, Bacher A. Active site topology and reaction mechanism of GTP cyclohydrolase I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:12120–12125. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Konorev EA, Kennedy MC, Kalyanaraman B. Cell-permeable superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase mimetics afford superior protection against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity: the role of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1999;368:421–428. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bailey B, Waraska J, Acworth I. Direct determination of tissue aminothiol, disulfide, and thioether levels using HPLC-ECD with a novel stable boron-doped diamond working electrode. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;594:327–3239. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-411-1_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vásquez-Vivar J, Whitsett J, Derrick M, Ji X, Yu L, Tan S. Tetrahydrobiopterin in the prevention of hypertonia in hypoxic fetal brain. Ann Neurol. 2009;66:323–331. doi: 10.1002/ana.21738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sethumadhavan S, Vasquez-Vivar J, Migrino RQ, Harmann L, Jacob HJ, Lazar J. Mitochondrial DNA variant for complex I reveals a role in diabetic cardiac remodeling. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:22174–22182. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.327866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rogers GW, Brand MD, Petrosyan S, Ashok D, Elorza AA, Ferrick DA, Murphy AN. High throughput microplate respiratory measurements using minimal quantities of isolated mitochondria. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21746. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morse RH, Chan SI. Electron paramagnetic resonance studies of nitrosyl ferrous heme complexes. Determination of an equilibrium between two conformations. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:7876–7882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yonetani T, Tsuneshige A, Zhou Y, Chen X. Electron paramagnetic resonance and oxygen binding studies of alpha-Nitrosyl hemoglobin. A novel oxygen carrier having no-assisted allosteric functions. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:20323–20333. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.32.20323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kennedy MC, Antholine WE, Beinert H. An EPR investigation of the products of the reaction of cytosolic and mitochondrial aconitases with nitric oxide. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:20340–20347. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.33.20340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peisach J, Blumberg WE, Ogawa S, Rachmilewitz EA, Oltzik R. The effects of protein conformation on the heme symmetry in high spin ferric heme proteins as studied by electron paramagnetic resonance. J Biol Chem. 1971;246:3342–3355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dubach J, Gaffney BJ, More K, Eaton GR, Eaton SS. Effect of the synergistic anion on electron paramagnetic resonance spectra of iron-transferrin anion complexes is consistent with bidentate binding of the anion. Biophys J. 1991;59:1091–1100. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82324-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hill BG, Dranka BP, Zou L, Chatham JC, Darley-Usmar VM. Importance of the bioenergetic reserve capacity in response to cardiomyocyte stress induced by 4-hydroxynonenal. Biochem J. 2009;424:99–107. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun A, Zou Y, Wang P, Xu D, Gong H, Wang S, Qin Y, Zhang P, Chen Y, Harada M, Isse T, Kawamoto T, Fan H, Yang P, Akazawa H, Nagai T, Takano H, Ping P, Komuro I, Ge J. Mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 plays protective roles in heart failure after myocardial infarction via suppression of the cytosolic JNK/p53 pathway in mice. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e000779. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carnicer R, Hale AB, Suffredini S, Liu X, Reilly S, Zhang MH, Surdo NC, Bendall JK, Crabtree MJ, Lim GB, Alp NJ, Channon KM, Casadei B. Cardiomyocyte GTP cyclohydrolase 1 and tetrahydrobiopterin increase NOS1 activity and accelerate myocardial relaxation. Circ Res. 2012;111:718–727. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.274464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hasegawa H, Sawabe K, Nakanishi N, Wakasugi OK. Delivery of exogenous tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) to cells of target organs: role of salvage pathway and uptake of its precursor in effective elevation of tissue BH4. Mol Genet Metab. 2005;86(Suppl 1):S2–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schmidt K, Kolesnik B, Gorren AC, Werner ER, Mayer B. Cell type-specific recycling of tetrahydrobiopterin by dihydrofolate reductase explains differential effects of 7,8-dihydrobiopterin on endothelial nitric oxide synthase uncoupling. Biochem Pharmacol. 2014;90:246–253. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2014.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laursen JB, Somers M, Kurz S, McCann L, Warnholtz A, Freeman BA, Tarpey M, Fukai T, Harrison DG. Endothelial regulation of vasomotion in apoE-deficient mice: implications for interactions between peroxynitrite and tetrahydrobiopterin. Circulation. 2001;103:1282–1288. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.9.1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alp NJ, McAteer MA, Khoo J, Choudhury RP, Channon KM. Increased endothelial tetrahydrobiopterin synthesis by targeted transgenic GTP-cyclohydrolase I overexpression reduces endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis in ApoE-knockout mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:445–450. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000115637.48689.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao Y, Wu J, Zhu H, Song P, Zou MH. Peroxynitrite-dependent zinc release and inactivation of guanosine 5′-triphosphate cyclohydrolase 1 instigate its ubiquitination in diabetes. Diabetes. 2013;62:4247–4256. doi: 10.2337/db13-0751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 46.Vásquez-Vivar J, Martásek P, Whitsett J, Joseph J, Kalyanaraman B. The ratio between tetrahydrobiopterin and oxidized tetrahydrobiopterin analogues controls superoxide release from endothelial nitric oxide synthase: an EPR spin trapping study. Biochem J. 2002;362:733–739. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3620733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Herold S, Exner M, Nauser T. Kinetic and mechanistic studies of the NO*-mediated oxidation of oxymyoglobin and oxyhemoglobin. Biochemistry. 2001;40:3385–3395. doi: 10.1021/bi002407m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Capeillere-Blandin C, Mathieu D, Mansuy D. Reduction of ferric haemoproteins by tetrahydropterins: a kinetic study. Biochem J. 2005;392:583–587. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shiro Y, Iwata T, Makino R, Fujii M, Isogai Y, Iizuka T. Specific modification of structure and property of myoglobin by the formation of tetrazolylhistidine 64(E7). Reaction of the modified myoglobin with molecular oxygen. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:19983–19990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Patel KB, Stratford MRL, Wardman P, Everett SA. Oxidation of tetrahydrobiopterin by biological radicals and scavenging of the trihydrobiopterin radical by ascorbate. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;32:203–211. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00777-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kappock TJ, Caradonna JP. Pterin-Dependent Amino Acid Hydroxylases. Chem Rev. 1996;96:2659–2756. doi: 10.1021/cr9402034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bailey SW, Weintraub ST, Hamilton SM, Ayling JE. Incorporation of molecular oxygen into pyrimidine cofactors by phenylalanine hydroxylase. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:8253–8260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Davis MD, Kaufman S. Evidence for the formation of the 4a-carbinolamine during the tyrosine-dependent oxidation of tetrahydrobiopterin by rat liver phenylalanine hydroxylase. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:8585–8596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.