Abstract

Sustaining collaborations between community-based organization leaders and academic researchers in community-engaged research (CEnR) in the service of decreasing health inequities necessitates understanding the collaborations from an inter-organizational perspective. We assessed the perspectives of community leaders and university-based researchers conducting community-engaged research in a medium-sized city with a history of community-university tension. Our research team, included experts in CEnR and organizational theory, used qualitative methods and purposeful, snowball sampling to recruit local participants and performed key informant interviews from July 2011–May 2012. A community-based researcher interviewed 11 community leaders, a university-based researcher interviewed 12 university-based researchers. We interviewed participants until we reached thematic saturation and performed analyses using the constant comparative method. Unifying themes characterizing community leaders and university-based researchers' relationships on the inter-organizational level include: 1) Both groups described that community-engaged university-based researchers are exceptions to typical university culture; 2) Both groups described that the interpersonal skills university-based researchers need for CEnR require a change in organizational culture and training; 3) Both groups described skepticism about the sustainability of a meaningful institutional commitment to community-engaged research 4) Both groups described the historical impact on research relationships of race, power, and privilege, but only community leaders described its persistent role and relevance in research relationships. Challenges to community-academic research partnerships include researcher interpersonal skills and different perceptions of the importance of organizational history. Solutions to improve research partnerships may include transforming university culture and community-university discussions on race, power, and privilege.

Abbreviations: CEnR, community-engaged research; CBPR, community-based participatory research

Keywords: Community-academic partnerships, Community-based participatory research, Community-engaged research, Inter-group relationships, Qualitative study

Highlights

-

•

Community leaders perceive community-engaged researchers as exceptions to the rule.

-

•

Community leaders and academics are unsure of institutional support for the research.

-

•

Community leaders discuss the persistence of race and power in research partnerships.

1. Introduction

Community-engaged research (CEnR), an approach to research designed to decrease health inequities, encompasses a spectrum of community participation from minimal to equal partnership in community-based participatory research (CBPR) (Hicks et al., 2012, Israel et al., 2005, Israel et al., 1998, Israel et al., 2001, Jones and Wells, 2007, Wallerstein, 1999, Minkler, 2005). Community-engagement, “the process of working collaboratively with and through groups of people affiliated by geographic proximity, special interest, or similar situations to address issues affecting the well-being of those people,” (Principles of Community Engagement, 2011) requires the development and maintenance of a working relationship between individual representatives of the community and of the researchers.

In recognition that the operationalization of the community-academic relationship is key to the success of CEnR, the literature describes challenges and best practices for forming CEnR partnerships (Hicks et al., 2012, Freudenberg, 2001, Goldberg-Freeman et al., 2007, Kennedy et al., 2009, Lantz et al., 2001, Metzler et al., 2003, Sullivan et al., 2001, Ndulue et al., 2012, Norris et al., 2007, Rosenthal et al., 2014, Santilli et al., 2011). Challenges include communication, sustaining projects, trust, and building and maintaining relationship in context of historical tensions (Freudenberg, 2001, Goldberg-Freeman et al., 2007, Kennedy et al., 2009, Lantz et al., 2001, Metzler et al., 2003, Sullivan et al., 2001, Tandon, 2007). A key influence on CEnR partnerships is inter-group, often called inter-organizational, dynamics, including the power differential between academic researchers and community members and tension between insiders and outsiders (Minkler, 2004, Eng et al., 2012). Prior systematic assessments of community-academic research relationships include both community and university representatives in their research (Freudenberg, 2001, Goldberg-Freeman et al., 2007, Kennedy et al., 2009, Lantz et al., 2001, Metzler et al., 2003, Sullivan et al., 2001, Tandon, 2007). Two have used qualitative methods which improves the ability to explore the relationships between the two groups (Goldberg-Freeman et al., 2007, Kennedy et al., 2009). However, since community and academic interviews were analyzed separately, the results are a reflection of one group's view of the other group or their own group, rather than an exploration of the inter-organizational dynamics (Goldberg-Freeman et al., 2007, Kennedy et al., 2009). Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, it seems that previous studies have not included community participants as full partners in the data collection and analytic process (Freudenberg, 2001, Goldberg-Freeman et al., 2007, Kennedy et al., 2009, Lantz et al., 2001, Metzler et al., 2003, Sullivan et al., 2001, Tandon, 2007, Cashman et al., 2008, Drahota et al., 2016, Kegler et al., 2016).

Accordingly, we systematically characterized community-academic research relationships by conducting in-depth interviews of community leaders and university-based researchers in New Haven, CT, a medium-sized city in the Northeast United States, using principles of CBPR with an emphasis on organizational diagnosis to recognize and examine the inter-organizational dynamics. We included a community leader as a full participant in all aspect of the research study, including data collection and analysis, collecting data from other community leaders without the presence of academic researchers, and analyzing the data from groups together with university-based researchers. In this manuscript, we describe the inter-organizational themes reflecting the perspective and experience of community leaders and university-based researchers in their research relationships.

2. Methods

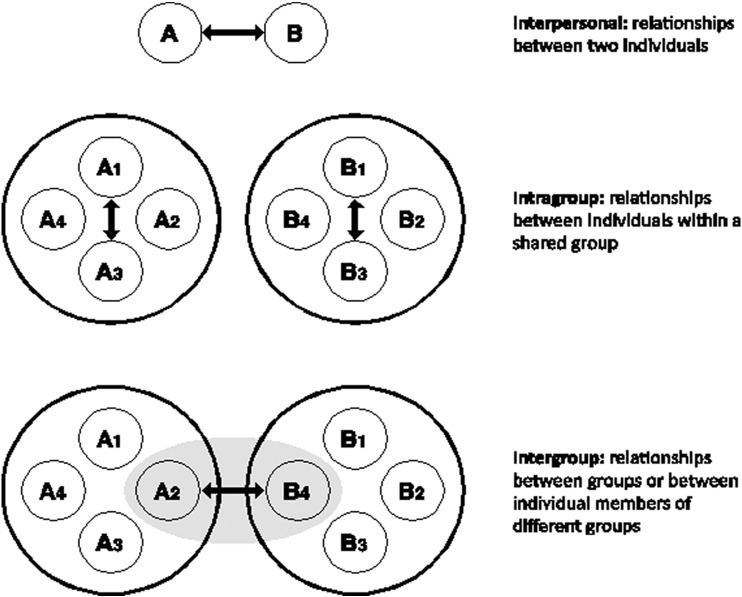

For the study approach and design, we used the principles of CBPR, organizational diagnosis, and qualitative methods (Israel et al., 1998, Wallerstein, 1999, Minkler, 2005, Minkler, 2004, Alderfer, 1987, Alderfer, 2011, Clayton and Smith, 1982, Wallerstein and Duran, 2010). We chose a CBPR approach to acknowledge the historical and contemporary examples of exploitation of marginalized communities by academic researchers (Corbie-Smith et al., 1999, Gamble, 1997, Jones, 1992, Pacheco et al., 2013, Rencher and Wolf, 2013, Skloot, 2011) and to recognize the influence of potential exploitation on the current relationship in our city (Bass, 2013, Disare, 2013). Applying the principles of CBPR, we recognized that the key groups in this study were university and community. We, therefore, treated community and university researchers within our study as equitably as possible. For example, the project was co-led by a community-based researcher, who is also a community leader, and one university-based researcher. We designed a research approach and structure to enable equitable representation of both community leaders and university-based researchers. We committed to a process to ensure co-learning and the development and dissemination of meaningful products for both groups. We utilized the strengths and knowledge of community leaders and university-based researchers in the design, conduct, analysis and dissemination of study findings. Lastly, recognizing the centrality of group dynamics, i.e. ‘insiders’ and ‘outsiders’, in the theory and practice of CBPR, (Eng et al., 2012) we were attentive to the theory and methods used in organizational diagnosis for an exploration of group dynamics (Alderfer, 2011). Organizational diagnosis uses an approach that considers group memberships in all phases of the research. For this study, this meant an awareness of group dynamics in the following interactions: the interpersonal (e.g., interviewer-interviewee), intra-group or intra-organizational (between individuals who share same group memberships (e.g., academic-academic)), or inter-group or inter-organizational (between individuals who belong to different group memberships (academics-community)) (Fig. 1) (Curry et al., 2012, Wells, 1980).

Fig. 1.

Levels of organizational process – based on figures as presented in Curry et al. (2012).

For the purposes of this study, our main identifier of group membership was self-reported academic or community affiliation. While we focused on group representation in the research structure and ensured that data analysis occurred as a discussion between representatives of both groups, we also ensured that potentially sensitive human interactions occurred as intra-group discussions without the presence of the other group (Israel et al., 1998). As a result of this approach and methodology, we interpreted the study findings as an inter-group discussion (between representatives of the community leadership and representatives of the academic institutions) rather than two separate conversations about the research relationship. We used qualitative methods to collect and analyze data as this method is ideal for exploring complex and potentially sensitive human interactions (Bradley et al., 2007, Britten, 1995, Patton, 2002).

2.1. The research team development and partnership

A dyad of a community leader and a university-based researcher co-led the study. The dyad received training in community-based participatory research, organizational theory, and qualitative methods from: 1) a university-based researcher/organizational psychologist who facilitated and provided feedback on the co-researchers' interactions and helped shaped the co-researchers' understanding of interactions between organizations and 2) a university-based researcher with expertise in CBPR and qualitative methods. The co-researchers created an advisory committee of both community leaders and university-based researchers to provide input in all aspects of the research study. The advisory committee consisted of two community leaders and two university-based researchers. The three coding members of the research team met with the advisory committee on a bimonthly basis to brainstorm and discuss issues related to the study. The co-researchers presented their study quarterly to the Yale Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars Program Steering Committee for Community Projects, a committee of community leaders and university-based researchers who oversee community-based participatory research projects in New Haven, CT and advise community- and university-based researchers about CBPR projects. The Steering Committee has existed for the 11 years that there has been a CBPR training program for post-doctoral physician trainees in the city (Rosenthal et al., 2014, Rosenthal et al., 2009).

2.2. Study design

The co-researchers employed purposeful, snowball sampling to recruit participants from their medium-sized city and performed key informant interviews. The advisory team and the Steering Committee created an initial list of key informants of both community leaders and university researchers who had been involved in community-engaged research that they believed represented more partnered research. This initial list contained twenty community leaders, identified as the main representatives of their organizations which provide health-related services. The list also included thirteen university-based researchers who are in the health sciences, including medicine, nursing, and public health, and had partnered with community organizations in a research project. The co-researchers expanded this list using snowball sampling by asking participants at the end of each interview for other potential community leaders and university-based researchers for recruitment. The co-researchers conducted recruitment and data collection until achieving thematic saturation (Patton, 2002). The co-researchers recruited community leaders and university-based researcher participants via telephone and email to invite them to participate in the study. The co-researchers contacted each participant twice and then scheduled interviews in a location convenient to the participant. The Human Investigation Committee at the Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, CT determined that the study was exempt from review.

2.3. Data collection

The co-researchers each conducted in-person, in-depth interviews from July 2011–May 2012. The community leader interviewed eleven community leaders, and the university-based researcher interviewed twelve university-based researchers (Alderfer, 2011, Alderfer and Tucker, 1996). One community leader did not want the interview to be recorded, and two university-based researchers withdrew from the study after the interviews. Analysis did not include these three interviews. Interview guides for both groups were identical in content, asking participants about their experiences and advice (see Table 1). The co-researchers used probes for clarification and elaboration on participants' statements. The use of probes was highly contextual for each interview (Patton, 2002). Interviews, lasting from 30 to 90 min, were audio-taped, professionally transcribed, and reviewed to ensure accuracy.

Table 1.

Interview guide for community leader/university researcher.

|

2.4. Analytic methods

Each coder on the research team independently coded each transcript and then met to negotiate consensus over differences in independent coding. The coders developed a code structure in accordance with principles of grounded theory, using systematic, inductive procedures to generate insights grounded in the views expressed by study participants.(Patton, 2002) The coders used the constant comparative method to ensure that emergent themes were consistently classified, to expand on existing codes, and to identify novel concepts and refine codes. The coders met biweekly to achieve consensus and finalized a comprehensive code structure capturing all data concepts. Two non-coding members of the research team (representing the community and academia) independently read all transcripts and then discussed major ideas and concepts with the coders. The university-based co-researcher then systematically applied the final code structure to all transcripts and used qualitative analysis software (ATLAS.ti 5.0, Scientific Software Development, Berlin, Germany) to facilitate data organization and retrieval. Finally, the co-researcher dyad conducted participant confirmation. The co-researchers distributed a summary of the results to all participants by email to confirm that the developing themes accurately reflected participants' experiences and asked for a reply within two weeks of receipt (Patton, 2002). Ten community leaders and eight university-based researchers affirmed our findings.

3. Results

We analyzed 20 transcripts, 10 from community leaders and 10 from community-engaged university-based researchers. Four recurrent themes characterized the inter-organizational dynamics affecting community leader and university-based researcher relationships (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Results.

| Theme | Quotes from community leaders | Quotes from university-based researchers |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3.1.1. Theme 1: both groups described the perception that community-engaged university researchers are exceptions to the typical culture of the university

Community leaders described that community-engaged researchers who were invested in the community, listened to and respected the community and that this behavior makes them different from their university affiliation. One community leader stated that this type of behavior engenders trust. The community-engaged university researchers described experiencing this distinction when community leaders describe them as different from the normal academic culture because their behaviors differ from those of other university researchers.

3.1.2. Theme 2: “Be humble”: both groups described that the interpersonal skills university-based researchers need for community-engaged research require a change in organizational culture and training

Both groups described that only people with specific interpersonal skills–such as humility, patience, affability and respect for others–should do community-engaged research. Both groups expressed that these skills were not dependent on individuals, only, but that intra-organizational change is necessary to improve these skills. Importantly, the perspective of why these skills were sub-optimal among university researchers differed by group. A university-based researcher implicated the academic culture and training, keeping the challenge at the level of the intra-organizational (university, only), whereas a community leader implicated the deeply-embedded power differential between the two groups, arguing that the challenge for improving these qualities is inter-organizational (community and university).

3.1.3. Theme 3: both groups described a skepticism about whether the university commitment to community-engaged research can be meaningfully sustained

Interviewees were concerned about the commitment of the university using community-engaged research to address health inequities. A community leader was unsure whether having an inter-organizational experience of conducting a community-engaged research project changes the university researchers for the long-term. A university researcher was concerned about how the intra-organizational priorities within the university affects the inter-organizational relationships–stating that the lack of senior community-engaged researchers is an indication of the university's lack of commitment to community-engaged research.

3.1.4. Theme 4: both groups described the historical impact of race, power, and privilege on research relationships, but only community leaders consistently described the importance of its persistent role in research relationships

Both groups described that their research relationships are embedded in the inter-group historical relationship. Only community leaders described the impact of race and power on the quality of the research relationship and the responsibility of a university researcher for the history of exploitation perpetrated by the institutions they represent. Community leaders also described the need to talk about race in CEnR relationships because of the role of race and power in creating health disparities. University researchers had a range of opinions from a theoretical understanding of why race and power play a role in the current relationship between community and university to the belief that it is not relevant in the current environment. One university-based researcher stated that race and power influence community-university relationships, though these topics are not at the forefront of their minds because it was not their lived experience. On the other hand, another university-based researcher stated that community leaders need to move beyond historical exploitation because regulations are in place to protect the community.

4. Discussion

Using a CBPR approach enriched by organizational diagnosis in a medium-size city, we characterized the perspectives of community leaders and university-based researchers on the inter-organizational dynamics in their research relationships. A key and novel finding, highlighting how interpersonal relationships are embedded within inter-group dynamics, is that community-engaged researchers who conducted partnered research are perceived as exceptions to the typical culture of the university. Participants perceive that changing this perception of exceptionalism requires a change in both intra-group university organizational culture and in the inter-group hierarchies between the university and the community. In addition, the concern from both groups about the sustainability of community-engaged research and the lack of agreement between the groups on the role of race, power, and privilege in current research relationships reflect that the interpersonal relationships between community leaders and university researchers are embedded in the inter-group relationship.

The finding describing the perception of exceptionalism is a novel finding within CEnR literature and may offer opportunities to improve CEnR relationships. The phenomenon of exceptionalism is well-described when groups of individuals have limited or culturally scripted relationships with each other but not in the literature describing CEnR relationships (Bonilla-Silva, 2010, Bonilla-Silva and Seamster, 2011, Fries-Britt and Griffin, 2007, Ward, 2013, West, 1990). Exceptionalism in CEnR relationships, the view that the people one is working with are not like the group to which they belong, i.e. they are exceptional in some way (smarter, more thoughtful, less arrogant, or less angry) can be a challenge and an opportunity. The challenge is that exceptionalism runs the risk of maintaining the status quo and the possibility of limiting the meaningful dissemination of community-engaged research to only those considered exceptional. For example, community leaders can maintain their view of the exploitative university and work only with the exceptional community-engaged researchers, i.e. those who conducted partnered research and/or those who have certain characteristics. This exceptional status of a few researchers may limit the exposure of other researchers to potential community partners and vice versa. Furthermore, universities may point to a small number of exceptional community-engaged researchers and feel that their commitment to high quality research relationships with their community has been fulfilled when broader changes regarding inclusivity or working through issues of race, power and privilege may be necessary. On the other hand, exceptionalism can be a mechanism by which to improve the relationship between two groups that have limited or non-existent relationships. In this scenario, the community-engaged researchers and community leaders help build a relationship between the two groups they represent. In this role, the community-engaged university-based researchers and their community partners could advocate to members of their own group about the possibility and success of the CEnR relationships with members from the other group.

Our emphasis on using organizational diagnosis deepens the understanding about community-engaged research relationships. This process allows us to explore similarities and differences between the groups and seek meaningful ways to intervene on an organizational level. For example, both groups recommend that university researchers behave in a certain way when conducting community-engaged research. Without the organizational lens, we interpret attitudes and behavior on an interpersonal level, that is specific people are more suited for community-engaged research because of their interpersonal skills or because they are exceptional. With an organizational lens, we can hypothesize that this type of behavior may be created and propagated by university culture; and university culture may thereby be a place of intervention.

Furthermore, the finding describing the different ways that the community leaders and university-based researchers respond to the influence of race, power and privilege in the research relationships has implications for possible solutions. This finding reflects literature that describes how the exploitation of communities by powerful institutions influences the way in which the community organizations perceive university researchers and why we need to recognize “insider-outsider” group dynamics in these relationships (Norris et al., 2007, Pacheco et al., 2013, Lale et al., 2010, White-Cooper et al., 2009). This analysis captured the perspectives of both groups working in the same community and, thereby, perspectives on the same environment and similar set of experiences. The differences in their perspectives can lead directly to opportunities to engage in pertinent discussions between both groups on race, power, and privilege in our community.

There are several limitations to this study. This study was conducted in one medium-sized city in the Northeast, US. It contained the perspectives of health sciences researchers from different disciplines in one university who conducted community-engaged research. It also contained community leaders who had participated in community-engaged research with health science researchers. We did not ask the participants to self-identity their research approach on the CEnR continuum. The perspectives of the study participants may not characterize the experiences of other community leaders and university researchers in another setting. Research is conducted in many different academic and non-academic settings and between different community-academic research partners. For example, perspectives may be different in community-academic settings with longer relationships or with academic training programs that have existed for longer (Bowie et al., 2009). However, as a part of the CBPR process, we shared the results with the study participants and the Steering Committee. We have also presented the findings to national audiences consisting of both community leaders and academic researchers in other settings who also have historic tensions where audience members affirmed the study findings (Ray et al., 2013, Ray and Wang, 2013, Wang et al., 2013). In these multiple settings, our findings were confirmed by others. Further research should use quantitative methods in different settings to confirm these findings. We also focused on group membership as belonging to “academia” or “community” rather than on other group memberships. The exploration of the effect of other group memberships is another avenue for analysis.

5. Conclusion

These findings suggest that intra-organizational changes within the university may improve inter-organizational relationships between university and community for the benefit of conducting community-engaged research. These changes might include transforming academic culture and training so that the characteristics pertinent for community-engaged researchers and the discussions about historical and contemporary influences of race, power, and privilege in the design and conduct of research in all research training are normative, rather than the exception. A focus on increasing capacity of academia and community organizations to build and sustain meaningful research relationships may facilitate greater understanding and may ultimately improve our ability to address persistent health disparities in marginalized communities.

Financial disclosures

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Conflict of interest

This study was possible with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars Program and the Center for Research Engagement at Yale. The study sponsors had no role in study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing the report; or the decision to submit the report for publication. At the time of this study, KHW, GL, DB, and MSR were funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars Program. ACS was funded by a grant from the Patrick and Catherine Weldon Donaghue Medical Research Foundation (R01 HD070740).

Transparency document

Transparency document.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the study participants for their participation and feedback and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars Program Steering Committee on Community Projects for their feedback during the study. The authors acknowledge Arian Schulze, MPhil, for the design of the figure, and Tara Rizzo, MPH, for editorial assistance.

Footnotes

The Transparency document associated with this article can be found, in online version.

References

- Alderfer C.P. 1987. An Intergroup Perspective on Group Dynamics: Handbook of Organizational Behavior. [Google Scholar]

- Alderfer C.P. Oxford University Press; New York: 2011. The Practice of Organizational Diagnosis: Theory and Methods. [Google Scholar]

- Alderfer C.P., Tucker R.C. A field experiment for studying race relations embedded in organizations. J. Organ. Behav. 1996;17(1):43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Bass P. February 21, 2013 ed. New Haven Independent; 2013. Yale Puts Controversial Military Project on Hold. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla-Silva E. 3rd ed. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers; Lanham: 2010. Racism Without Racists: Color-blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in the United States. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla-Silva E., Seamster L. Emerald Group Publishing Limited; United Kingdon: 2011. The Sweet Enchantment of Color Blindness in Black Face: Explaining the “Miracle,” Debating Politics and Suggesting a Way for Hope to be “For Real” in America. [Google Scholar]

- Bowie J., Eng E., Lichtenstein R. A decade of postdoctoral training in CBPR and dedication to Thomas A. Bruce. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. 2009;3(4):267–270. doi: 10.1353/cpr.0.0091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley E.H., Curry L.A., Devers K.J. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv. Res. 2007;42(4):1758–1772. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britten N. Qualitative interviews in medical research. Br. Med. J. 1995;311(6999):251–253. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6999.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cashman S.B., Adeky S., Allen A.J. The power and the promise: working with communities to analyze data, interpret findings, and get to outcomes. Am. J. Public Health. 2008;98(8):1407–1417. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.113571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton P.A., Smith K.K. Studying intergroup relations embedded in organizations. Adm. Sci. Q. 1982;27(1):35–65. [Google Scholar]

- Corbie-Smith G., Thomas S.B., Williams M.V., Moody-Ayers S. Attitudes and beliefs of African Americans toward participation in medical research. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 1999;14(9):537–546. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.07048.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry L.A., O'Cathain A., Clark V.L.P., Aroni R., Fetters M., Berg D. The role of group dynamics in mixed methods health sciences research teams. J. Mixed Methods Res. 2012;6(1):5–20. [Google Scholar]

- Disare M. Yale Daily News; 2013. With Election, Town-gown Relations at Key Juncture.http://yaledailynews.com/blog/2013/09/09/with-election-town-gown-at-jucture/ (Accessed Febuary 20, 2014) [Google Scholar]

- Drahota A., Meza R.D., Brikho B. Community-academic partnerships: a systematic review of the state of the literature and recommendations for future research. Milbank Q. 2016;94(1):163–214. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eng E., Strazza K., Rhodes S., Griffith D., Shirah K., Mebane E. Insiders and outsiders assess who is “the community”. In: Israel B.A., Eng Eugenia, Schulz Amy J., editors. Methods for Community-based Participatory Research for Health. Jossey-Bass; Somerset, US: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Freudenberg N. Case history of the Center for Urban Epidemiologic Studies in New York City. J Urban Health. 2001;78(3):508–518. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fries-Britt S., Griffin K. The black box: how high-achieving blacks resist stereotypes about Black Americans. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2007;48(5):509–524. [Google Scholar]

- Gamble V.N. Under the shadow of Tuskegee: African Americans and health care. Am. J. Public Health. 1997;87(11):1773–1778. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.11.1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg-Freeman C., Kass N.E., Tracey P. “You've got to understand community”: community perceptions on “breaking the disconnect” between researchers and communities. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. 2007;1(3):231–240. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2007.0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks S., Duran B., Wallerstein N. Evaluating community-based participatory research to improve community-partnered science and community health. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. 2012;6(3):289–299. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2012.0049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel B.A., Schulz A.J., Parker E.A., Becker A.B. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu. Rev. Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel B.A., Schulz A.J., Parker E.A., Becker A.B., Community-Campus Partnerships for H Community-based participatory research: policy recommendations for promoting a partnership approach in health research. Educ. Health (Abingdon) 2001;14(2):182–197. doi: 10.1080/13576280110051055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel B.A., Parker E.A., Rowe Z. Community-based participatory research: lessons learned from the Centers for Children's Environmental Health and Disease Prevention Research. Environ. Health Perspect. 2005;113(10):1463–1471. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones J.H. The Tuskegee legacy. AIDS and the black community. Hast. Cent. Rep. 1992;22(6):38–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones L., Wells K. Strategies for academic and clinician engagement in community-participatory partnered research. JAMA. 2007;297(4):407–410. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.4.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kegler M.C., Blumenthal D.S., Akintobi T.H. Lessons learned from three models that use small grants for building academic-community partnerships for research. J. Health Care Poor Underserved. 2016;27(2):527–548. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2016.0076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy C., Vogel A., Goldberg-Freeman C., Kass N., Farfel M. Faculty perspectives on community-based research: “i see this still as a journey”. J. Empir. Res. Hum. Res. Ethics. 2009;4(2):3–16. doi: 10.1525/jer.2009.4.2.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lale A., Moloney R., Alexander G.C. Academic medical centers and underserved communities: modern complexities of an enduring relationship. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2010;102(7):605–613. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30638-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lantz P.M., Viruell-Fuentes E., Israel B.A., Softley D., Guzman R. Can communities and academia work together on public health research? Evaluation results from a community-based participatory research partnership in Detroit. J Urban Health. 2001;78(3):495–507. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzler M.M., Higgins D.L., Beeker C.G. Addressing urban health in Detroit, New York City, and Seattle through community-based participatory research partnerships. Am. J. Public Health. 2003;93(5):803–811. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.5.803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M. Ethical challenges for the “outside” researcher in community-based participatory research. Health Educ. Behav. 2004;31(6):684–697. doi: 10.1177/1090198104269566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M. Community-based research partnerships: challenges and opportunities. J Urban Health. 2005;82(2 Suppl 2) doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ndulue U., Perea F.C., Kayou B., Martinez L.S. Team-building activities as strategies for improving community-university partnerships: lessons learned from Nuestro Futuro Saludable. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. 2012;6(2):213–218. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2012.0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris K.C., Brusuelas R., Jones L., Miranda J., Duru O.K., Mangione C.M. Partnering with community-based organizations: an academic institution's evolving perspective. Ethn. Dis. 2007;17(1 Suppl 1):S27–S32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco C.M., Daley S.M., Brown T., Filippi M., Greiner K.A., Daley C.M. Moving forward: breaking the cycle of mistrust between American Indians and researchers. Am. J. Public Health. 2013;103(12):2152–2159. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton M. 2002. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. [Google Scholar]

- Principles of Community Engagement . 2011. Clinical and Translational Science Awards Consortium Community Engagement Key Function Committee Task Force on the Principles of Community Engagement. [Google Scholar]

- Ray N., Wang K.H. Paper presented at: Yale Cancer Center: Towards Health Equity in Cancer. 2013. Bridging the gap between academia and the community. (New Haven, CT) [Google Scholar]

- Ray N., Wang K.H., Berg D. American Public Health Association; 2013. Race, Power, and Privilege in the Community-academic Research Relationship: Perspectives of Community Scholars Engaged in Academic Research Partnerships. (November 4, 2013 Boston, MA) [Google Scholar]

- Rencher W.C., Wolf L.E. Redressing past wrongs: changing the common rule to increase minority voices in research. Am. J. Public Health. 2013;103(12):2136–2140. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal M.S., Lucas G.I., Tinney B. Teaching community-based participatory research principles to physicians enrolled in a health services research fellowship. Acad. Med. 2009;84(4):478–484. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31819a89e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal M.S., Barash J., Blackstock O. Building community capacity: sustaining the effects of multiple, two-year community-based participatory research projects. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. 2014;8(3):365–374. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2014.0049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santilli A., Carroll-Scott A., Wong F., Ickovics J. Urban youths go 3000 miles: engaging and supporting young residents to conduct neighborhood asset mapping. Am. J. Public Health. 2011;101(12):2207–2210. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skloot R. 1st pbk. ed. Broadway Paperbacks; New York: 2011. The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan M., Kone A., Senturia K.D., Chrisman N.J., Ciske S.J., Krieger J.W. Researcher and researched—community perspectives: toward bridging the gap. Health Educ. Behav. 2001;28(2):130–149. doi: 10.1177/109019810102800202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tandon S.D. A vision for progress in community health partnerships. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. 2007;1(1):11–30. doi: 10.1353/cpr.0.0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N. Power between evaluator and community: research relationships within New Mexico's healthier communities. Soc. Sci. Med. 1999;49(1):39–53. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00073-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N., Duran B. Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: the intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. Am. J. Public Health. 2010;100(Suppl. 1):S40–S46. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K., Ray N.J., Berg D. American Public Health Association; 2013. Multi-level Challenges of Creating and Sustaining Community-engaged University Researchers in Community-university Relationships. (November 4, 2013, Boston, MA) [Google Scholar]

- Ward L.T. 2013. “Oh, You Are An Exception!” Academic Success and Black Male Students Resistance to Systemic Racism. [Google Scholar]

- Wells L. The group-as-a-whole: a systemic socio-analytic perspective of interpersonl and group relations. In: Cooper C.L., Alderfer C.P., editors. Advances in Experiential Social Processes. vol. 2. Wiley; Chichester; New York: 1980. pp. 165–199. [Google Scholar]

- West C. The new cultural politics of difference. October. 1990;53:93–109. [Google Scholar]

- White-Cooper S., Dawkins N.U., Kamin S.L., Anderson L.A. Community-institutional partnerships: understanding trust among partners. Health Educ. Behav. 2009;36(2):334–347. doi: 10.1177/1090198107305079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Transparency document.