Abstract

Background and objectives

Despite the high burden of CKD, few specific therapies are available that can halt disease progression. In animal models, clopidogrel has emerged as a potential therapy to preserve kidney function. The effect of clopidogrel on kidney function in humans has not been established.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

The Secondary Prevention of Small Subcortical Strokes Study randomized participants with prior lacunar stroke to treatment with aspirin or aspirin plus clopidogrel. We compared annual eGFR decline and incidence of rapid eGFR decline (≥30% from baseline) using generalized estimating equations and interval-censored proportional hazards regression, respectively. We also stratified our analyses by baseline eGFR, systolic BP target, and time after randomization.

Results

At randomization, median age was 62 (interquartile range, 55–71) years old; 36% had a history of diabetes, 90% had hypertension, and the median eGFR was 81 (interquartile range, 65–94) ml/min per 1 m2. Persons receiving aspirin plus clopidogrel had an average annual change in kidney function of −1.39 (95% confidence interval, −1.15 to −1.62) ml/min per 1.73 m2 per year compared with −1.52 (95% confidence interval, −1.30 to −1.74) ml/min per 1.73 m2 per year among persons receiving aspirin only (P=0.42). Rapid kidney function decline occurred in 21% of participants receiving clopidogrel plus aspirin compared with 22% of participants receiving aspirin plus placebo (hazard ratio, 0.94; 95% confidence interval, 0.79 to 1.10; P=0.42). Findings did not vary by baseline eGFR, time after randomization, or systolic BP target (all P values for interaction were >0.3).

Conclusions

We found no effect of clopidogrel added to aspirin compared with aspirin alone on kidney function decline among persons with prior lacunar stroke.

Keywords: antiplatelet; decline; creatinine; eGFR; Animals; Aspirin; blood pressure; Confidence Intervals; diabetes mellitus; Disease Progression; glomerular filtration rate; Humans; hypertension; Incidence; Models, Animal; Random Allocation; Renal Insufficiency, Chronic; Secondary Prevention; Stroke; Stroke, Lacunar; Ticlopidine; clopidogrel

Introduction

CKD affects up to 20 million United States adults, and it has become increasingly prevalent worldwide (1,2). Persons with CKD have high risk for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality and progression to ESRD. Despite the significant burden of kidney disease, specific therapies to prevent incidence and progression of CKD remain limited. As such, novel therapies to prevent kidney function decline are needed.

Recently, clopidogrel has emerged as a promising potential therapy to attenuate chronic kidney injury. Clopidogrel is an irreversible thienopyridine inhibitor of the P2Y12 ADP receptor known for reducing the activation and aggregation of platelets (3). The P2Y12 receptor has also been identified in several extraplatelet tissues related to vascular physiology, including vascular smooth muscle (4,5), the collecting duct (6), leukocytes (7), and macrophages (8). Several lines of evidence support investigation of clopidogrel as a potential treatment to attenuate kidney function decline. Platelets have been shown to be mediators of kidney injury (9–11). In a mouse model of primary endothelial injury, both clopidogrel and platelet depletion similarly reduced glomerular injury and preserved peritubular microvascular endothelium (12). Clopidogrel has also shown anti-inflammatory properties in murine models of vascular disease as well as human subjects (13–15). For example, in rats that underwent five sixths nephrectomy, clopidogrel administration reduced inflammatory cell infiltration of kidney tissues, decreased expression of inflammatory markers, and attenuated decreases in kidney function and increases in proteinuria (16). Clopidogrel also reduced afferent arterial wall thickening and mesangial and tubular cell remodeling in rats with angiotensin II–induced hypertension (17). In both rats and humans, clopidogrel has also been shown to improve endothelial function (18,19) and reduce vasoconstriction (20,21). In rats with angiotensin II–induced hypertension, clopidogrel slowed the elevation of mean arterial pressure in response to angiotensin II, and it preserved blood flow autoregulation in the kidney compared with control rats (22).

On the basis of these experimental findings, we hypothesized that clopidogrel would have protective effects on kidney function in human subjects with known cardiovascular disease. Because the effects of clopidogrel on human kidney function have not been established, we designed this study to examine the effect of randomization to clopidogrel or placebo added to aspirin on kidney function decline among persons with recent lacunar stroke in the Secondary Prevention of Small Subcortical Strokes (SPS3) Study, a randomized trial of antiplatelet and BP control interventions in 3020 participants with recent lacunar stroke for prevention of recurrent stroke (ClinicalTrials.gov no. NCT00059306) (23).

Materials and Methods

Study Design

We performed a post hoc analysis of the SPS3 Study. The SPS3 Study was a randomized, multinational, multicenter, two by two factorial trial designed to evaluate the effectiveness of two double-blinded antiplatelet regimens and two systolic BP targets (open label) in preventing recurrent stroke among persons with recent lacunar stroke. In the antiplatelet trial, all participants received 325 mg aspirin daily and were randomized to receive an additional 75 mg clopidogrel daily or a matching placebo. Randomization was stratified by clinical center and baseline hypertensive status. A permuted block design with variable block size was used (23). Patients were simultaneously randomized to a systolic BP target of <130 or 130–149 mmHg. Further details regarding the SPS3 Study design were published previously (24). The antiplatelet trial was stopped 10 months before the planned end date because of futility with respect to the primary outcome and increased risk of major hemorrhage and all-cause mortality in the arm receiving aspirin plus clopidogrel on interim analysis; the BP trial continued until the planned study end date with participants maintained on aspirin only (23).

Participants

The SPS3 Study included 3020 participants 30 years of age or older with a symptomatic lacunar stroke in the preceding 180 days confirmed on magnetic resonance imaging. Inclusion and exclusion criteria have been previously published (24). Pertinent to these analyses, patients were excluded if they had an eGFR below 40 ml/min per 1.73 m2 at baseline. Participants were followed until a common end study date, with a mean follow-up duration of 3.4 years. Details regarding enrollment and follow-up of participants were published previously (23). For this study, 409 SPS3 Study participants without at least one follow-up measure of serum creatinine after baseline measurement were excluded for a total of 2611 participants included. Included and excluded participants are compared in Supplemental Table 1. There was no significant difference in antiplatelet treatment assignment between included and excluded participants (P=0.36). All participants signed informed consent, and the trial was approved by the appropriate institutional review board.

Outcomes

For these analyses, there were two primary outcomes: (1) annualized eGFR change and (2) rapid eGFR decline. We defined rapid eGFR decline as a reduction in creatinine-based eGFR ≥30% from baseline at any time during the study period. The outcome of eGFR decline ≥30% over the study period has been validated as a surrogate end point for risk of kidney disease progression (25). We calculated eGFR using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation (26). Serum creatinine measures were obtained from all SPS3 Study participants at annual follow-up visits until the study end date with the exception of the last study visit (24).

Intervention

All SPS3 Study participants took enteric-coated aspirin (325 mg daily) and were randomized (double blind) to take clopidogrel (75 mg daily) or a matching placebo. Antiplatelet medications were provided to patients at randomization and each quarterly follow-up visit, with adherence measured by pill counts. Patients were educated about contraindicated medications, including nonstudy aspirin, clopidogrel, and anticoagulants, while on SPS3 Study antiplatelet therapy.

Participant Characteristics

Demographic characteristics, including age, sex, and race, were self-reported by participants at a study visit before randomization. Medical history was collected before randomization, including smoking, medications, diabetes, ischemic heart disease (defined as a composite of unstable angina, myocardial infarction, and coronary revascularization), and hypertension (defined by previous diagnosis, an average systolic BP of at least 140 mmHg, or an average diastolic BP of at least 90 mmHg at prerandomization study visits). Trained clinical staff obtained anthropometric measures, including height and weight, and measured baseline BP per guidelines. The average of BP readings from a minimum of two study visits before randomization was used. The SPS3 Study trained staff to measure BP using a protocol that has been previously published (24).

Analyses

First, we summarized baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of our study population stratified by antiplatelet study arm. Second, we compared annualized eGFR change among persons randomized to aspirin plus placebo versus aspirin plus clopidogrel using generalized estimating equations (27). Generalized estimating equation models estimate rates of within-subject changes over time on the basis of a working correlation structure that models within-subject correlation of repeated measures. Our analysis used an exchangeable correlation structure, which offered a better model fit than others tested, to model within-subject correlation of creatinine-based GFR estimates. We included all recorded creatinine measures before truncation at 5 years after randomization due to very limited data beyond that point. We adjusted estimates using inverse probability of censoring weighted analysis to account for potential bias due to loss to follow-up (28). Specifically, we modeled each participant’s probability of being censored on the basis of age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, smoking, diabetes, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, congestive heart failure, hyperlipidemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, creatinine, BP, alcohol use, statin use, body mass index, and antihypertensive use. We then used the inverse of this probability as a weight applied to persons with known outcomes in the analyses of kidney decline. Because creatinine was measured annually and because the exact dates of rapid eGFR decline were unknown, we used interval-censored proportional hazards regression analysis, which specifies the interval of time between measures, to evaluate the effect of clopidogrel added to aspirin on rapid decline of eGFR (29). In a sensitivity analysis, we censored creatinine measurements made after the early termination of the antiplatelet trial and repeated the analysis as above.

Our group recently reported faster eGFR decline in the lower BP target group relative to the higher BP target group (30). Therefore, we also stratified analyses by BP target arm, and we tested for interaction of systolic BP target with antiplatelet arm on each outcome. We also stratified analyses by time after randomization (0–1 versus 1–5 years) to compare short- and long-term kidney function changes. Finally, outcomes were stratified by baseline eGFR (<60 or ≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2) to determine if the effects of clopidogrel added to aspirin were similar in those with lower and higher baseline eGFRs. All analyses followed intention to treat principles and were conducted using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Among 2611 participants included in this analysis, the median age was 62 years old, with an interquartile range (IQR) of 55–71; 63% were men, 32% were Hispanic, 16% were black, and 55% lived in the United States. A history of ischemic heart disease was reported by 281 (11%) participants; 949 (36%) had a history of diabetes, and 90% had hypertension (n=2339). Median systolic BP at randomization was 141 (IQR, 129–154) mmHg, and median diastolic BP was 79 (IQR, 72–85) mmHg. Median eGFR was 81 (IQR, 65–94) ml/min per 1.73 m2, and 15% of participants had an eGFR below 60 ml/min per m2 (Supplemental Table 1). There were no significant differences in baseline demographic or clinical characteristics between the two antiplatelet treatment arms (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of 2611 included Secondary Prevention of Small Subcortical Strokes Study participants

| Parameter | Clopidogrel Plus Aspirin, n=1303 | Placebo Plus Aspirin, n=1308 |

|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 62 (55–71) | 62 (55–71) |

| Men | 821 (63) | 834 (64) |

| Race | ||

| Black | 206 (16) | 207 (16) |

| Hispanic | 418 (32) | 417 (32) |

| Non-Hispanic white | 645 (50) | 655 (50) |

| Other/multiple | 34 (3) | 29 (2) |

| Diabetes | 457 (35) | 492 (38) |

| Fasting blood glucose | 105 (92–133) | 106 (93–141) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 28 (25–32) | 28 (25–32) |

| Current smoker | 253 (19) | 254 (19) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 135 (10) | 136 (10) |

| Hypertension | 1165 (89) | 1174 (90) |

| Systolic BP, mmHg | 141 (129–154) | 141 (130–154) |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg | 79 (72–85) | 78 (72–86) |

| Antihypertensive use | ||

| Total | 1110 (85) | 1103 (84) |

| Diuretics | 496 (39) | 517 (41) |

| Potassium supplements | 48 (4) | 49 (4) |

| β-Blockers | 342 (27) | 343 (27) |

| Calcium channel blockers | 355 (28) | 356 (28) |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors | 712 (56) | 724 (57) |

| Angiotensin receptor blockers | 225 (18) | 225 (18) |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers | 880 (68) | 890 (68) |

| Miscellaneous BP medications | 94 (7) | 106 (8) |

| No. of antihypertensive meds | ||

| 0 | 92 (7) | 105 (8) |

| 1 | 493 (39) | 461 (36) |

| 2 | 393 (31) | 402 (32) |

| 3+ | 288 (23) | 304 (24) |

| eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 81 (66–94) | 81 (67–94) |

| eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 210 (16) | 191 (15) |

| Randomized to systolic BP target <130 mmHg | 650 (50) | 652 (50) |

Data presented as median (interquartile range) or number (%).

Annualized eGFR Decline

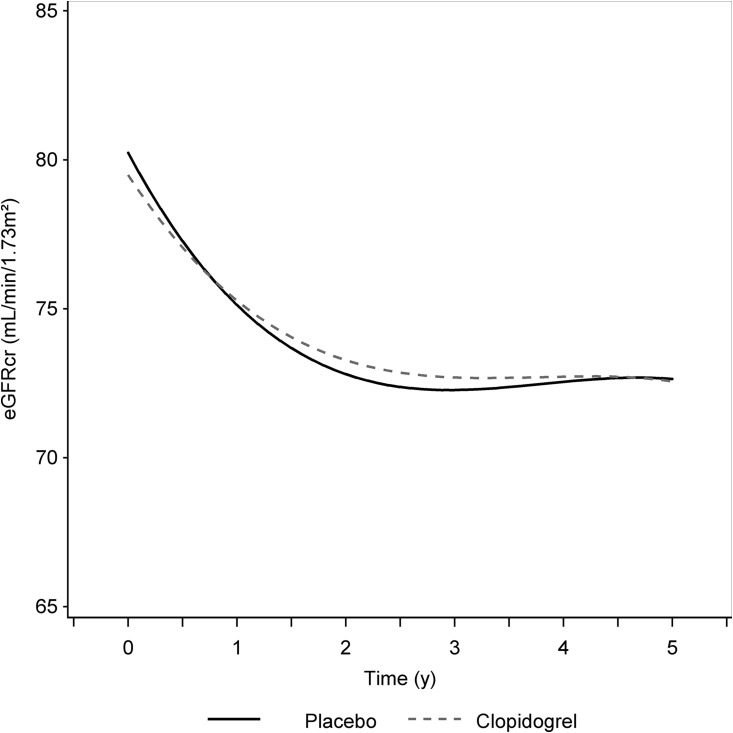

Overall, SPS3 Study participants had an estimated annual eGFR change of −1.43 (95% confidence interval [95% CI], −1.58 to −1.28) ml/min per 1 m2 over 5 years of follow-up. Median follow-up time was 3.1 (IQR, 2.0–5.0) years. In persons receiving aspirin plus clopidogrel, eGFR changed, on average, by −1.39 (95% CI, −1.62 to −1.15) ml/min per 1.73 m2 per year compared with −1.52 (95% CI, −1.74 to −1.30) ml/min per 1.73 m2 per year in persons receiving aspirin only (P=0.42) (Table 2). The rate of eGFR decline was fastest in both arms in the first year after randomization and appeared to plateau after 2 years (Figure 1). Although the first year decline appeared to be somewhat faster in the placebo arm compared with the dual arm (−5.1 versus −4.2 ml/min per 1 m2), the difference did not reach statistical significance (P=0.07) (Table 2). Moreover, we found no statistically significant differences in annualized eGFR decline between antiplatelet treatment arms when we stratified by baseline eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 or systolic BP target, and tests for interaction were not statistically significant (P value >0.9 for both). A sensitivity analysis only of measurements made before the early termination of the antiplatelet trial had similar results (Supplemental Figure 1, Supplemental Table 2). There were no differences in eGFR decline by antiplatelet arm when considering patients with diabetes and nonpatients with diabetes separately (P=0.57 and P=0.89, respectively).

Table 2.

Estimated annual eGFR change by antiplatelet treatment arms with stratification by time after randomization, systolic BP target, and baseline eGFR

| Group | Annualized Change in eGFR, ml/min per m2 (95% Confidence Interval) | Difference (95% Confidence Interval) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clopidogrel Plus Aspirin | Placebo Plus Aspirin | |||

| Overall, 0–5 yr | −1.39 (−1.62 to −1.15) | −1.52 (−1.74 to −1.30) | 0.13 (−0.19 to 0.45) | 0.42 |

| Stratified by time after randomization, yr | ||||

| 0–1 | −4.2 (−4.9 to −3.5) | −5.1 (−5.8 to −4.4) | 0.89 (−0.06 to 1.84) | 0.07 |

| 1–5 | −0.68 (−0.96 to −0.40) | −0.62 (−0.89 to −0.35) | −0.06 (−0.45 to 0.33) | 0.77 |

| Stratified by systolic BP target, mmHg | ||||

| <130 | −1.63 (−1.95 to −1.32) | −1.72 (−2.0 to −1.42) | 0.09 (−0.35 to 0.53) | 0.69 |

| 130–150 | −1.32 (−1.62 to −1.02) | −1.19 (−4.7 to 2.3) | −0.12 (−3.6 to 3.4) | 0.94 |

| Stratified by baseline eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | ||||

| <60 | −0.71 (−1.20 to −0.23) | −0.82 (−1.35 to −0.28) | 0.10 (−0.62 to 0.83) | 0.78 |

| >60 | −1.52 (−1.77 to −1.27) | −1.61 (−1.84 to −1.38) | 0.08 (−0.26 to 0.42) | 0.63 |

Estimated within-group changes, between-group differences, and P values from generalized estimating equation models included inverse probability weighting to account for loss to follow-up.

Figure 1.

Similar trajectories of eGFR during first five years of follow-up in each antiplatelet arm of Secondary Prevention of Small Subcortical Strokes study. Estimates from the generalized estimating equation model with inverse probability of censoring weighting were used to account for study dropout. Median follow-up was 3.1 years.

Rapid eGFR Decline

A total of 561 (21%) SPS3 Study participants had rapid kidney function decline. Of 1303 participants receiving clopidogrel plus aspirin, 269 (21%) had rapid eGFR decline compared with 292 (22%) of 1308 participants receiving aspirin plus placebo (P=0.42) (Table 3). Consistent with the analysis of annual change in eGFR as a continuous outcome, we found that differences between antiplatelet arms in rapid decline were small and did not reach statistical significance during the first year of follow-up or the subsequent 4 years (P>0.2 for both comparisons). There were no significant differences in rapid decline by study arm when we stratified by systolic BP target or baseline eGFR, and tests for interaction with antiplatelet arm were not statistically significant (P values for interactions were 0.79 and 0.36, respectively). Our sensitivity analysis showed similar rapid eGFR decline with or without censoring of creatinine measurements after early termination of the antiplatelet trial (Supplemental Table 3).

Table 3.

Incidence of rapid decline in eGFR by antiplatelet arm with stratification by time after randomization, systolic BP target, and baseline eGFR

| Group | Event Rate, n (%) | Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspirin Plus Clopidogrel | Aspirin Plus Placebo | |||

| Overall, 0–5 yr | 269/1303 (21) | 292/1308 (22) | 0.94 (0.79 to 1.10) | 0.42 |

| Stratified by time after randomization, yr | ||||

| 0–1 | 109/1303 (8.4) | 126/1308 (9.6) | 0.85 (0.66 to 1.10) | 0.22 |

| 1–5 | 160/1303 (12) | 166/1308 (13) | 1.02 (0.81 to 1.27) | 0.90 |

| Stratified by systolic BP target, mmHg | ||||

| <130 | 150/650 (23) | 164/652 (25) | 0.92 (0.74 to 1.14) | 0.44 |

| 130–150 | 119/653 (18) | 128/656 (20) | 0.96 (0.75 to 1.23) | 0.72 |

| Stratified by baseline eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | ||||

| <60 | 50/210 (24) | 46/191 (24) | 1.11 (0.74 to 1.65) | 0.62 |

| >60 | 219/1093 (20) | 246/1117 (22) | 0.90 (0.75 to 1.08) | 0.26 |

Hazard ratios and P values from interval-censored proportional hazards models included inverse probability weighting to account for loss to follow-up.

Discussion

In this post hoc analysis of the SPS3 Study randomized trial, we found that administration of clopidogrel compared with placebo did not significantly affect eGFR decline when added to aspirin. Furthermore, findings did not differ within prespecified subgroups by study period, baseline eGFR, or systolic BP target.

Our study contrasts with prior data from animal studies, in which clopidogrel showed promise as a therapeutic agent to attenuate kidney function decline via several putative mechanisms. Tu et al. (16) showed attenuated kidney injury as measured by serum creatinine and urine protein excretion with a corresponding reduction in inflammation in rats with five sixths nephrectomy after clopidogrel administration. Graciano et al. (17) showed reduced afferent arterial wall thickening and decreased mesangial and tubular cell remodeling in rats with angiotensin II–induced hypertension after clopidogrel administration. More recently, clopidogrel was shown to preserve kidney vascular autoregulation in rats with angiotensin II–induced hypertension by Osmond et al. (22), and Schwarzenberger et al. (12) showed reduction of platelet-mediated kidney injury in a mouse model of primary endothelial injury. Contrary to the evidence from animal models, our study suggests that clopidogrel does not have significant effects on kidney function in humans, at least in the setting of concomitant aspirin use.

There are several possible explanations for the discrepancy between our study and those performed in experimental models with regard to clopidogrel’s effect on kidney function. For one, human doses of clopidogrel are significantly lower than those used in the experimental studies, which ranged from 10 to 75 mg/kg per day (12,16,17,22). In contrast, participants in this study were given 75 mg/d clopidogrel. The studied dose may have been inadequate due to P2Y12 inhibitor resistance in participants with lower eGFR. Prior reports suggest that clopidogrel has reduced antiplatelet activity and decreased efficacy for prevention of cardiovascular events in subjects with limited kidney function (31). However, a large majority of SPS3 Study participants had preserved eGFR, and we found no differences by baseline eGFR. The observed reduction of eGFR during the first years of follow-up, likely due to the hemodynamic effects of initiating or intensifying antihypertensive therapy after stroke (32), could have masked smaller effects by clopidogrel. Additionally, the majority of participants received angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers, which are known to preserve kidney function in the long term and could have masked an effect by clopidogrel. However, this would be contrary to the additive kidney-protective effect of clopidogrel observed by Tu et al. (16) in rats administered clopidogrel and irbesartan. Adverse effects of clopidogrel, such as increased bleeding, may also have obscured any benefit that it had with respect to kidney function.

The administration of aspirin to all participants could have also masked the effects of clopidogrel. Although both aspirin and clopidogrel have antiplatelet activity, aspirin has a very different mechanism and profile of pleiotropic activity. Studies of aspirin and eGFR are inconclusive (33–37), although they generally show no association between the two. Nevertheless, there is reason to suspect that prostaglandin inhibition by aspirin could change how the kidney microvasculature responds to clopidogrel (38). It is also possible that aspirin’s antiplatelet activity lowered the potential for clopidogrel to reduce platelet-mediated damage in the kidney. Still, administering aspirin to both groups offered the advantages of a randomized placebo control to the interpretation of any effect by clopidogrel that could have been observed without sacrificing clinical equipoise.

Further research could be directed toward other more potent P2Y12 inhibitors, such as ticagrelor or prasugrel. In contrast to higher doses of clopidogrel, these newer P2Y12 antagonists have been shown to be more effective than clopidogrel in preventing cardiovascular events in prospective trials and within subgroups having lower kidney function (39,40). There is also growing evidence suggesting other similar receptors, such as the P2X7 receptor, as potential targets for new kidney injury therapies (41,42). These targets have yet to be investigated in depth with human subjects, and their effects on kidney function are less well established.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate the effect of clopidogrel on eGFR decline in a human study population with known cardiovascular disease and high BP. The SPS3 Study’s randomized, placebo-controlled design was especially well suited for investigating the effect of clopidogrel added to aspirin on eGFR decline. Additionally, the study population showed significant vascular disease burden at enrollment, reflecting the vascular pathology of the animal models that showed kidney benefits from clopidogrel. Our studied outcome of rapid eGFR decline was observed in a sizable proportion of the study population, and annual eGFR decline was in excess of what is usually observed in the general population (43). Included participants were evenly distributed between antiplatelet arms with regard to baseline characteristics. Therefore, our results are unlikely to be significantly affected by confounding clinical or demographic variables. Additionally, we accounted for differences in follow-up and survival with inverse probability of censoring weighted analysis.

This study had a few notable limitations. For one, the SPS3 Study was not specifically designed to examine kidney function decline as a primary outcome; therefore, the results of our post hoc analysis must be interpreted cautiously. However, our data suggest that clinically significant differences between dual therapy and aspirin alone are unlikely. Whether the results can be generalized to persons without prior strokes or those with more severely reduced eGFR (<40 ml/min per 1.73 m2) is unclear. Nonetheless, our findings did not differ when we compared persons with eGFR above or below 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Although we excluded persons without follow-up creatinine measures, baseline characteristics were similar between antiplatelet treatment arms, making selection bias due to this constraint unlikely. An additional limitation was the measurement of kidney function solely by serum creatinine. Consequently, we cannot exclude an effect that clopidogrel may have had on proteinuria or eGFR measured by other tests, such as cystatin C. We believe that this underscores the need for more randomized trials in nephrology.

In summary, this study did not show a significant effect of clopidogrel added to aspirin on eGFR decline. There remains a need for new therapies to address the burden of kidney disease in the United States and around the world. Given the very promising animal data on the kidney-protective effects of P2Y12 inhibition, further research to address kidney disease might be directed toward other potential therapies of the same or related classes.

Disclosures

R.S. received an honorarium from Merck for participating in a Renal Expert Input Forum; this honorarium was donated to the Northern California Institute for Research and Education to support kidney research. C.A.P. has served as a consultant for Cricket Health Inc. and Vital Labs Inc. All other authors have declared no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R25MD006832 (to J.C.I.), the University of California, San Francisco Dean's Office Resource Allocation Program for Trainees (RAPtr), and NIH grant 1R01AG046206 (to C.A.P.).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.00100117/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) : National Chronic Kidney Disease Fact Sheet: General Information and National Estimates on Chronic Kidney Disease in the United States, 2014. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/pdf/kidney_factsheet.pdf. Accessed October 3, 2016

- 2.Jha V, Garcia-Garcia G, Iseki K, Li Z, Naicker S, Plattner B, Saran R, Wang AY, Yang CW: Chronic kidney disease: Global dimension and perspectives. Lancet 382: 260–272, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schrör K: Clinical pharmacology of the adenosine diphosphate (ADP) receptor antagonist, clopidogrel. Vasc Med 3: 247–251, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Högberg C, Svensson H, Gustafsson R, Eyjolfsson A, Erlinge D: The reversible oral P2Y12 antagonist AZD6140 inhibits ADP-induced contractions in murine and human vasculature. Int J Cardiol 142: 187–192, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wihlborg AK, Wang L, Braun OO, Eyjolfsson A, Gustafsson R, Gudbjartsson T, Erlinge D: ADP receptor P2Y12 is expressed in vascular smooth muscle cells and stimulates contraction in human blood vessels. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 24: 1810–1815, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Y, Peti-Peterdi J, Müller CE, Carlson NG, Baqi Y, Strasburg DL, Heiney KM, Villanueva K, Kohan DE, Kishore BK: P2Y12 receptor localizes in the renal collecting duct and its blockade augments arginine vasopressin action and alleviates nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. J Am Soc Nephrol 26: 2978–2987, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diehl P, Olivier C, Halscheid C, Helbing T, Bode C, Moser M: Clopidogrel affects leukocyte dependent platelet aggregation by P2Y12 expressing leukocytes. Basic Res Cardiol 105: 379–387, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kronlage M, Song J, Sorokin L, Isfort K, Schwerdtle T, Leipziger J, Robaye B, Conley PB, Kim HC, Sargin S, Schön P, Schwab A, Hanley PJ: Autocrine purinergic receptor signaling is essential for macrophage chemotaxis. Sci Signal 3: ra55, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson RJ, Alpers CE, Yoshimura A, Lombardi D, Pritzl P, Floege J, Schwartz SM: Renal injury from angiotensin II-mediated hypertension. Hypertension 19: 464–474, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson RJ: The glomerular response to injury: Progression or resolution? Kidney Int 45: 1769–1782, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barnes JL: Platelets in glomerular disease. Nephron 77: 378–393, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwarzenberger C, Sradnick J, Lerea KM, Goligorsky MS, Nieswandt B, Hugo CP, Hohenstein B: Platelets are relevant mediators of renal injury induced by primary endothelial lesions. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 308: F1238–F1246, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quinn MJ, Bhatt DL, Zidar F, Vivekananthan D, Chew DP, Ellis SG, Plow E, Topol EJ: Effect of clopidogrel pretreatment on inflammatory marker expression in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol 93: 679–684, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adamski P, Koziński M, Ostrowska M, Fabiszak T, Navarese EP, Paciorek P, Grześk G, Kubica J: Overview of pleiotropic effects of platelet P2Y12 receptor inhibitors. Thromb Haemost 112: 224–242, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Antonino MJ, Mahla E, Bliden KP, Tantry US, Gurbel PA: Effect of long-term clopidogrel treatment on platelet function and inflammation in patients undergoing coronary arterial stenting. Am J Cardiol 103: 1546–1550, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tu X, Chen X, Xie Y, Shi S, Wang J, Chen Y, Li J: Anti-inflammatory renoprotective effect of clopidogrel and irbesartan in chronic renal injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 77–83, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graciano ML, Nishiyama A, Jackson K, Seth DM, Ortiz RM, Prieto-Carrasquero MC, Kobori H, Navar LG: Purinergic receptors contribute to early mesangial cell transformation and renal vessel hypertrophy during angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 294: F161–F169, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Warnholtz A, Ostad MA, Velich N, Trautmann C, Schinzel R, Walter U, Munzel T: A single loading dose of clopidogrel causes dose-dependent improvement of endothelial dysfunction in patients with stable coronary artery disease: Results of a double-blind, randomized study. Atherosclerosis 196: 689–695, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giachini FR, Osmond DA, Zhang S, Carneiro FS, Lima VV, Inscho EW, Webb RC, Tostes RC: Clopidogrel, independent of the vascular P2Y12 receptor, improves arterial function in small mesenteric arteries from AngII-hypertensive rats. Clin Sci (Lond) 118: 463–471, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Froldi G, Bertin R, Dorigo P, Montopoli M, Caparrotta L: Endothelium-independent vasorelaxation by ticlopidine and clopidogrel in rat caudal artery. J Pharm Pharmacol 63: 1056–1062, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.André P, DeGuzman F, Haberstock-Debic H, Mills S, Pak Y, Inagaki M, Pandey A, Hollenbach S, Phillips DR, Conley PB: Thienopyridines, but not elinogrel, result in off-target effects at the vessel wall that contribute to bleeding. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 338: 22–30, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Osmond DA, Zhang S, Pollock JS, Yamamoto T, De Miguel C, Inscho EW: Clopidogrel preserves whole kidney autoregulatory behavior in ANG II-induced hypertension. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 306: F619–F628, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benavente OR, Hart RG, McClure LA, Szychowski JM, Coffey CS, Pearce LA; SPS3 Investigators : Effects of clopidogrel added to aspirin in patients with recent lacunar stroke. N Engl J Med 367: 817–825, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benavente OR, White CL, Pearce L, Pergola P, Roldan A, Benavente MF, Coffey C, McClure LA, Szychowski JM, Conwit R, Heberling PA, Howard G, Bazan C, Vidal-Pergola G, Talbert R, Hart RG; SPS3 Investigators: The secondary prevention of small subcortical strokes (SPS3) study. Int J Stroke 6: 164–175, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levey AS, Inker LA, Matsushita K, Greene T, Willis K, Lewis E, de Zeeuw D, Cheung AK, Coresh J: GFR decline as an end point for clinical trials in CKD: A scientific workshop sponsored by the National Kidney Foundation and the US Food and Drug Administration. Am J Kidney Dis 64: 821–835, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J; CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) : A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150: 604–612, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liang K-Y, Zeger SL: Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika 73: 13–22, 1986 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robins JM, Finkelstein DM: Correcting for noncompliance and dependent censoring in an AIDS Clinical Trial with inverse probability of censoring weighted (IPCW) log-rank tests. Biometrics 56: 779–788, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Finkelstein DM: A proportional hazards model for interval-censored failure time data. Biometrics 42: 845–854, 1986 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peralta CA, McClure LA, Scherzer R, Odden MC, White CL, Shlipak M, Benavente O, Pergola P: Effect of intensive versus usual blood pressure control on kidney function among individuals with prior lacunar stroke: A post hoc analysis of the secondary prevention of small subcortical strokes (SPS3) randomized trial. Circulation 133: 584–591, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morel O, Muller C, Jesel L, Moulin B, Hannedouche T: Impaired platelet P2Y12 inhibition by thienopyridines in chronic kidney disease: Mechanisms, clinical relevance and pharmacological options. Nephrol Dial Transplant 28: 1994–2002, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palmer BF: Renal dysfunction complicating the treatment of hypertension. N Engl J Med 347: 1256–1261, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fored CM, Ejerblad E, Lindblad P, Fryzek JP, Dickman PW, Signorello LB, Lipworth L, Elinder CG, Blot WJ, McLaughlin JK, Zack MM, Nyrén O: Acetaminophen, aspirin, and chronic renal failure. N Engl J Med 345: 1801–1808, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Evans M, Fored CM, Bellocco R, Fitzmaurice G, Fryzek JP, McLaughlin JK, Nyrén O, Elinder CG: Acetaminophen, aspirin and progression of advanced chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 24: 1908–1918, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kurth T, Glynn RJ, Walker AM, Rexrode KM, Buring JE, Stampfer MJ, Hennekens CH, Gaziano JM: Analgesic use and change in kidney function in apparently healthy men. Am J Kidney Dis 42: 234–244, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Curhan GC, Knight EL, Rosner B, Hankinson SE, Stampfer MJ: Lifetime nonnarcotic analgesic use and decline in renal function in women. Arch Intern Med 164: 1519–1524, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pastori D, Pignatelli P, Perticone F, Sciacqua A, Carnevale R, Farcomeni A, Basili S, Corazza GR, Davì G, Lip GY, Violi F; ARAPACIS (Atrial Fibrillation Registry for Ankle-Brachial Index Prevalence Assessment-Collaborative Italian Study) study group : Aspirin and renal insufficiency progression in patients with atrial fibrillation and chronic kidney disease. Int J Cardiol 223: 619–624, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kimberly RP, Plotz PH: Aspirin-induced depression of renal function. N Engl J Med 296: 418–424, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alexopoulos D, Panagiotou A, Xanthopoulou I, Komninakis D, Kassimis G, Davlouros P, Fourtounas C, Goumenos D: Antiplatelet effects of prasugrel vs. double clopidogrel in patients on hemodialysis and with high on-treatment platelet reactivity. J Thromb Haemost 9: 2379–2385, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tang XF, Fan JY, Meng J, Jin C, Yuan JQ, Yang YJ: Impact of new oral or intravenous P2Y12 inhibitors and clopidogrel on major ischemic and bleeding events in patients with coronary artery disease: A meta-analysis of randomized trials. Atherosclerosis 233: 568–578, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Solini A, Usuelli V, Fiorina P: The dark side of extracellular ATP in kidney diseases. J Am Soc Nephrol 26: 1007–1016, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Booth JW, Tam FW, Unwin RJ: P2 purinoceptors: Renal pathophysiology and therapeutic potential. Clin Nephrol 78: 154–163, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.National Kidney Foundation : K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: Evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis 39[Suppl 1]: S1–S266, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.