Abstract

Background and objectives

Management strategies for localized renal masses suspicious for renal cell carcinoma include radical nephrectomy, partial nephrectomy, thermal ablation, and active surveillance. Given favorable survival outcomes across strategies, renal preservation is often of paramount concern. To inform clinical decision making, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies comparing renal functional outcomes for radical nephrectomy, partial nephrectomy, thermal ablation, and active surveillance.

Design, settings, participants, & measurements

We searched MEDLINE, Embase, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials from January 1, 1997 to May 1, 2015 to identify comparative studies reporting renal functional outcomes. Meta-analyses were performed for change in eGFR, incidence of CKD, and AKI.

Results

We found 58 articles reporting on relevant renal functional outcomes. Meta-analyses showed that final eGFR fell 10.5 ml/min per 1.73 m2 lower for radical nephrectomy compared with partial nephrectomy and indicated higher risk of CKD stage 3 or worse (relative risk, 2.56; 95% confidence interval, 1.97 to 3.32) and ESRD for radical nephrectomy compared with partial nephrectomy. Overall risk of AKI was similar for radical nephrectomy and partial nephrectomy, but studies suggested higher risk for radical nephrectomy among T1a tumors (relative risk, 1.37; 95% confidence interval, 1.13 to 1.66). In general, similar findings of worse renal function for radical nephrectomy compared with thermal ablation and active surveillance were observed. No differences in renal functional outcomes were observed for partial nephrectomy versus thermal ablation. The overall rate of ESRD was low among all management strategies (0.4%–2.8%).

Conclusions

Renal functional implications varied across management strategies for localized renal masses, with worse postoperative renal function for patients undergoing radical nephrectomy compared with other strategies and similar outcomes for partial nephrectomy and thermal ablation. Further attention is needed to quantify the changes in renal function associated with active surveillance and nephron-sparing approaches for patients with preexisting CKD.

Keywords: chronic kidney disease; kidney neoplasms; acute kidney injury; outcome studies; Acute Kidney Injury; Attention; Carcinoma, Renal Cell; Clinical Decision-Making; Confidence Intervals; glomerular filtration rate; Humans; Incidence; kidney; Kidney Failure, Chronic; MEDLINE; Nephrectomy; Nephrons; Renal Insufficiency, Chronic; Risk

Introduction

The incidence of renal masses suspicious for localized kidney cancer has been increasing for several decades, possibly due to incidental diagnoses from increased use of cross-sectional imaging (1). Although kidney cancer can be aggressive, with over 14,000 deaths expected in the United States in 2016, the majority of the 60,000 newly diagnosed patients will have localized disease with favorable survival after treatment (2).

A number of management options are available for clinically localized renal masses, including surgery with partial nephrectomy (PN) or radical nephrectomy (RN), thermal ablation (TA), and active surveillance (AS). Guidelines from the American Urological Association (AUA) recommend surgery (either PN or RN) as standard of care for small renal masses (≤4 cm; clinical stage T1a) but also recommend TA and AS as acceptable approaches depending on patient comorbidities and preferences (3). For larger tumors, TA and AS are generally considered options, whereas surgery is currently the mainstay of treatment. PN is less preferred for clinical T2 tumors (>7 cm), although the current guidelines do not specifically cover this category.

Given the favorable overall and cancer-specific survival outcomes across management strategies, renal preservation is often of paramount concern (4). Except in patients with a solitary kidney, the comparative implications of each management strategy remain uncertain. The AUA, the European Association of Urology, and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network do not strictly define preference for management strategy on the basis of implications for renal function, but there has been a growing preference for PN for T1a tumors (5). The focus on absolute creatinine values, lack of studies on eGFR, and absence of any randomized trials were major limitations of the literature at the time of the last AUA guidelines in 2009 (3).

Since then, a number of comparative cohort studies have been reported, and a single randomized trial evaluated renal functional outcomes of PN and RN with median follow-up of 6.7 years. The randomized trial showed decreased incidence of moderate CKD but similar rates of ESRD for PN compared with RN (6). To summarize the robust but heterogeneous literature and inform clinical decision making, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies comparing renal functional outcomes for the four major management strategies for localized renal masses suspicious for renal cell carcinoma.

Materials and Methods

Data Search Strategy

As part of efforts by the Agency for Health Research and Quality (AHRQ) to inform health care decisions through comparative effectiveness research and reviews, key informants provided input as we refined questions, established eligibility criteria, and developed a protocol (PROSPERO registration CRD42015015878) for the systematic review. We report here renal function–specific results from a broader systematic review (7). MEDLINE, Embase, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials were searched from January 1, 1997 (the year that the tumor, node, and metastasis Classification of Malignant Tumor staging system for renal cell carcinoma was modified and distinctions of T1a/T1b and T2a/T2b were created) to May 1, 2015. Clinical stage definitions were defined by the American Joint Committee on Cancer: T1a, ≤4 cm; T1b, >4 to ≤7 cm; T2a, >7 to ≤10 cm; T2b, >10 cm; node negative; and no evidence of distant metastases. Clinicaltrials.gov was searched for relevant studies, and information was requested from device manufacturers.

Study Selection, Data Extraction, and Quality Assessment

DistillerSR (Evidence Partners, 2010) was used to manage the screening process. Paired investigators independently screened articles to assess eligibility on the basis of predefined criteria in a Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Time framework (Supplemental Appendix) to identify comparative studies of the management options or single cohort studies of AS (given the expectation that comparative studies of AS would be sparse). The key questions included determining the comparative renal functional outcomes of different interventions for the management of a renal mass suspicious for localized renal cell carcinoma and whether these relationships differed on the basis of patient demographics, clinical characteristics, or disease severity.

Data were abstracted from studies sequentially, and paired investigators independently assessed risk of bias for individual studies. To assess risk of bias for randomized trials, the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool was used, whereas the Cochrane Risk of Bias Assessment Tool for Non-Randomized Studies of Interventions was used for nonrandomized studies (8,9). Differences between reviewers were resolved through consensus. The draft AHRQ evidence report was peer reviewed and posted for public comments, which were compiled and addressed.

Data Synthesis and Analyses

All studies were summarized qualitatively. Renal functional outcomes were categorized broadly into continuous (changes in serum creatinine or eGFR largely on the basis of the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study equation when specified) and categorical (incidence of CKD stages ≥3, ≥3b, and ≥4 and ESRD) outcomes. Time points for outcomes vary across studies, but when possible, we used outcomes assessed via tabulated data or Kaplan–Meier curves closest to 1 year to avoid including competing causes of CKD other than the management strategy. eGFR at last follow-up was also routinely recorded. AKI was categorized as a harm rather than a primary renal functional outcome, but it is included in this report. Definitions for AKI varied across studies. Meta-analyses were conducted to reflect the authors’ definition of AKI from each study.

We conducted meta-analyses using a random effects model with the DerSimonian and Laird method when there were at least two sufficiently homogeneous studies. We identified substantial statistical heterogeneity (I2 statistic >50%). Funnel plots assessed potential publication bias for categorical outcomes. All meta-analyses were conducted using STATA 12.1 (College Station, TX). Strength of evidence was graded for each category of outcomes using the scheme recommended by the AHRQ’s Methods Guide for Conducting Comparative Effectiveness Reviews, which includes evaluating reporting bias, directness of the outcome, consistency of findings, and precision of the effect estimates (10).

Results

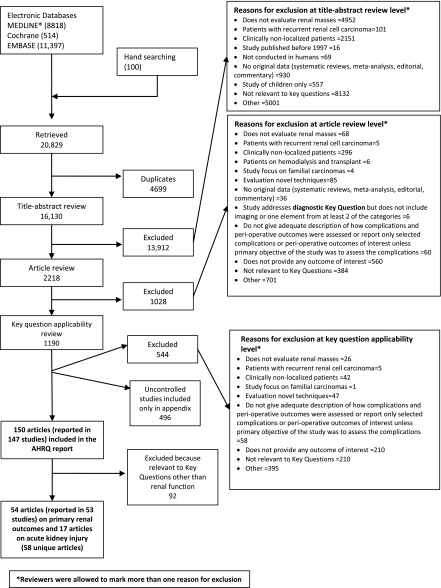

A total of 20,829 unique citations were identified, with 13,912 excluded during abstract screening, 1028 excluded during full-text screening, and 1190 excluded during key question applicability screening (Figure 1). Overall, 147 studies reported in 150 articles were included in the broader review, with a total of 53 studies reported in 54 articles (17,784 patients) related to primary renal functional outcomes and 17 related to AKI ultimately included in this systematic review (58 total unique articles) (6,11–67). Full details of the studies can be found in the full AHRQ report (7). Only one study, reported in two articles, was a randomized trial, and the remainder were comparative cohort studies (6,11).

Figure 1.

Summary of literature search showing the included 58 unique articles. AHRQ, Agency for Health Research and Quality.

RN versus PN

Continuous Outcomes.

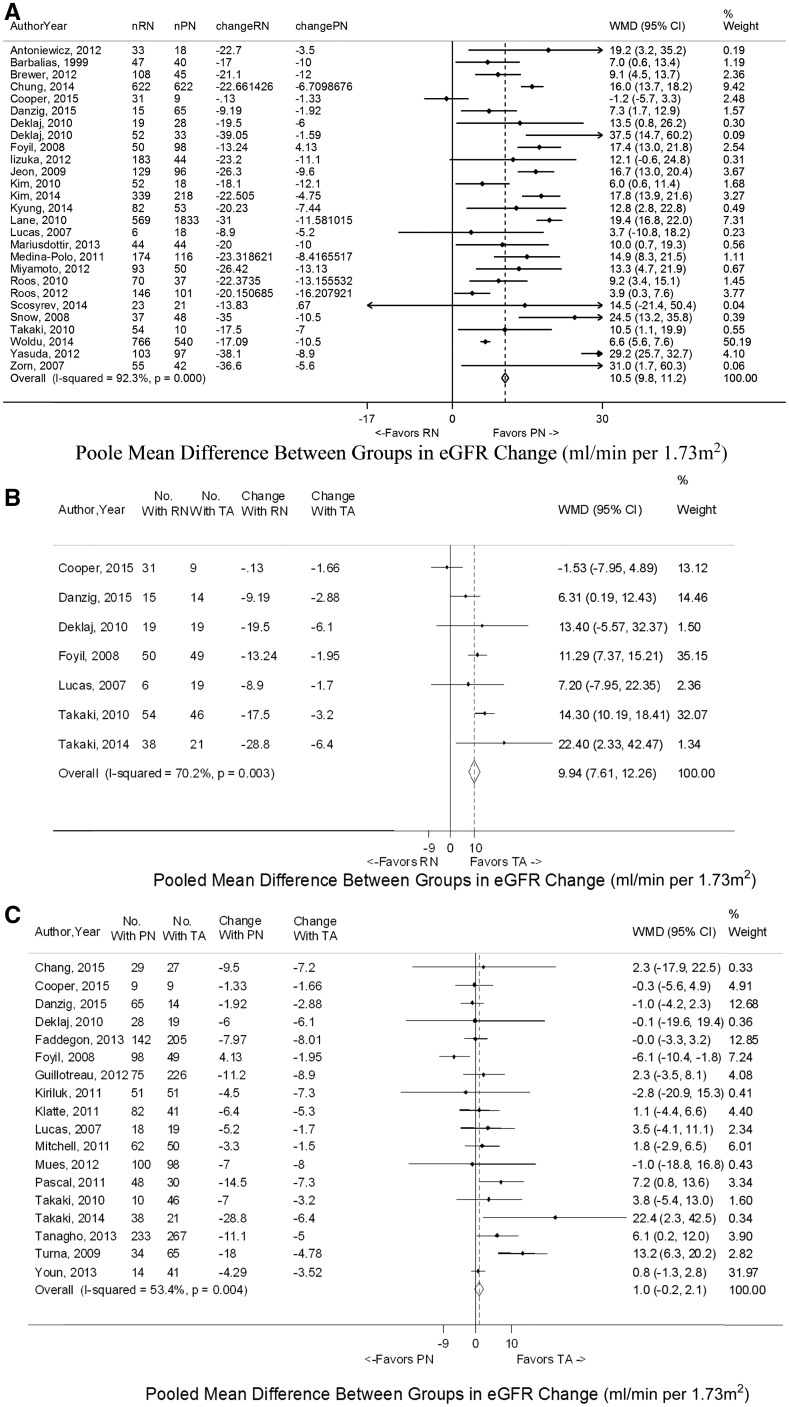

A total of 34 studies assessed continuous renal functional outcomes for RN versus PN (6,11–43). In general, final compiled continuous changes in creatinine and eGFR revealed more evidence of kidney dysfunction for RN compared with PN (Table 1). The final eGFR fell a median of 15 ml/min per 1.73 m2 lower with RN than with PN (−22.4 versus −7.4 ml/min per 1.73 m2). Meta-analyses showed that the mean increase in creatinine was 0.35 mg/dl (95% confidence interval [95% CI], 0.29 to 0.41) higher and that mean decrease in eGFR was 10.5 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (95% CI, 9.9 to 11.2) lower for RN compared with PN around the 1-year mark (Figure 2, Supplemental Figure 1). One randomized trial noted a mean difference in absolute eGFR of 14.1 ml/min per 1.73 m2 in favor of PN at 1 year (6). Significant heterogeneity for mean change in eGFR was observed.

Table 1.

Continuous renal functional outcomes for radical nephrectomy versus partial nephrectomy, radical nephrectomy versus thermal ablation, and partial nephrectomy versus thermal ablation

| Comparisons and Outcomes | Studies, N | Radical Nephrectomy or Partial Nephrectomy | Partial Nephrectomy or Thermal Ablation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, N | Study Median | Study Range | Patients, N | Study Median | Study Range | ||

| Radical nephrectomy versus partial nephrectomy | |||||||

| Follow-up creatinine, mg/dl | 12 | 966 | 1.46 | 1.24–1.70 | 708 | 1.03 | 0.96–1.70 |

| Change in creatinine | 12 | 966 | 0.47 | 0.30–0.51 | 708 | 0.12 | −0.05 to 0.40 |

| Follow-up eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 26 | 3713 | 54.6 | 42.9–90 | 4080 | 71.1 | 55.3–98.0 |

| eGFR change, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 27 | 3719 | −22.4 | −39.1 to −0.1 | 4098 | −7.4 | −16.2 to 4.1 |

| Radical nephrectomy versus thermal ablation | |||||||

| Follow-up creatinine, mg/dl | 1 | 31 | 1.63 | NA | 9 | 1.37 | NA |

| Change in creatinine | 1 | 31 | 0.53 | NA | 9 | 0.23 | NA |

| Follow-up eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 6 | 207 | 50.8 | 42.9–59.6 | 158 | 55.5 | 49.8–85.7 |

| eGFR change, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 7 | 213 | −13.2 | −28.8 to −0.1 | 177 | −2.9 | −6.4 to −1.7 |

| Partial nephrectomy versus thermal ablation | |||||||

| Follow-up creatinine, mg/dl | 9 | 683 | 1.31 | 0.89–1.70 | 673 | 1.4 | 0.88–1.70 |

| Change in creatinine | 9 | 683 | 0.23 | 0.06–0.40 | 673 | 0.13 | −0.10 to 0.22 |

| Follow-up eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 16 | 1080 | 66.1 | 47.5–87.8 | 1238 | 58.8 | 47.5–85.7 |

| eGFR change, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 18 | 1136 | −6.2 | −18 to 4.1 | 1278 | −4.9 | −8.0 to −1.5 |

NA, not applicable.

Figure 2.

Mean change in eGFR shown to favor partial nephrectomy (PN) and thermal ablation (TA) over radical nephrectomy (RN) on meta-analysis. The comparisons shown are (A) RN versus PN, (B) RN versus TA, and (C) PN versus TA. The widths of the horizontal lines represent the 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for each study. The diamonds at the bottoms of the graphs indicate the 95% CIs. WMD, weighted mean difference.

Subgroup analyses showed similar overall findings in studies including T1a, T1b, and T2 tumors, with two studies reporting nonsignificant trends toward poorer renal outcomes for RN in tumors 4–7 or >7 cm (24,29). Elderly and young patients both experienced similar 8- to 15-ml/min per 1.73 m2 lower eGFR decreases with RN compared with PN. The interaction of prior CKD with eGFR change was less clear. One study showed the observed benefit in eGFR for PN over RN similar for patients with preoperative eGFR >60 or <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, but two studies suggested that there was an attenuated difference for patients with preexisting CKD stage 3 (15,22,35). The absolute final eGFR values in all cases were, as expected, worse for patients with preoperative CKD. Another study suggested greater decreases in absolute eGFR for patients with higher preoperative eGFR (21). Taken together, the immediate clinical effect of management strategy to patients with preexisting CKD is likely greater, with categorical CKD outcomes potentially being more important than absolute changes. There is also the suggestion of greater preservation of eGFR with PN compared with RN than previously recognized for patients with eGFR>60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, although the long-term effect is not yet known.

Eleven studies reported long-term trends in creatinine and/or eGFR, showing an initial drop in the immediate postoperative period followed by improvement until approximately 3–6 months (6,12,14,17,19,25,28,32,37,39,42). At this point, levels stabilized for as long as 10–15 years (6). Three studies suggested that the lower final eGFR for RN occurred, because an equivalent improvement in eGFR in the 3- to 6-month time window was not present (17,25,32).

Categorical Outcomes.

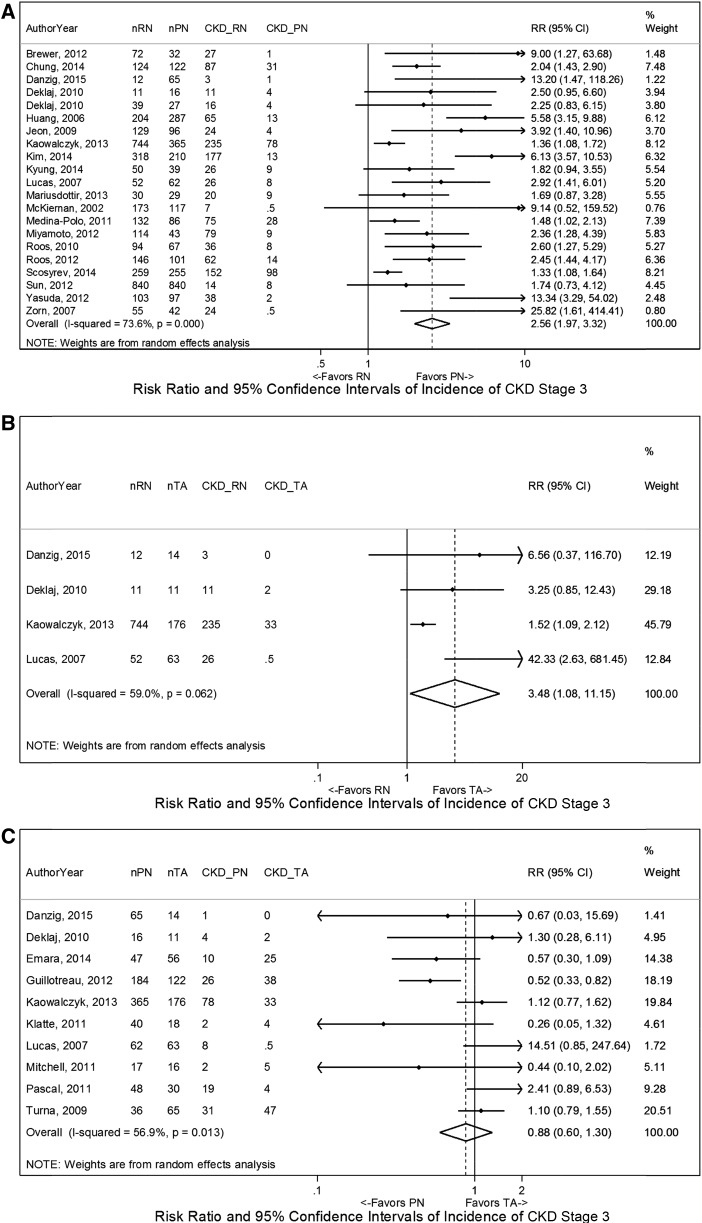

A total of 24 studies assessed categorical renal functional outcomes for RN versus PN, including one randomized trial and two population-based studies (Table 2) (6,14,15,18,19,21–25,27,28,31,34–38,40,41,44–47). The majority addressed incidence of CKD stage ≥3 (21 studies), and ten studies reported incidence of ESRD. Meta-analyses showed higher risk of CKD stage ≥3 (Figure 3) for RN compared with PN (relative risk [RR], 2.56; 95% CI, 1.97 to 3.32). Parallel findings were noted for ESRD (Supplemental Figure 2). Similar results were observed on meta-analyses using cutoffs for CKD stages ≥3b and ≥4, but the latter had only five included studies and was not statistically significant. One randomized trial reported >20% higher rate of CKD stage 3 for patients undergoing RN compared with PN on the basis of both the lowest eGFR or the last eGFR during follow-up (6). Similar findings were also observed across tumor sizes and age groups, although the absolute risk in elderly patients was two to four times higher than in younger patients, despite similar baseline eGFR (23).

Table 2.

Categorical renal functional outcomes for radical nephrectomy versus partial nephrectomy, radical nephrectomy versus thermal ablation, and partial nephrectomy versus thermal ablation

| Incidence of New Onset | Studies, N | Radical Nephrectomy or Partial Nephrectomy | Partial Nephrectomy or Thermal Ablation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, N | Outcomes, N | Outcomes, % | Patients, N | Outcomes, N | Outcomes, % | ||

| Radical nephrectomy versus partial nephrectomy | |||||||

| CKD stage ≥3 | 21 | 3598 | 1168 | 32 | 2901 | 341 | 12 |

| CKD stage ≥3b | 8 | 2068 | 451 | 22 | 3232 | 319 | 10 |

| CKD stage ≥4 | 5 | 1613 | 86 | 5 | 1385 | 50 | 4 |

| ESRD | 10 | 2807 | 23 | 1 | 3954 | 16 | 0.4 |

| Radical nephrectomy versus thermal ablation | |||||||

| CKD stage ≥3 | 4 | 819 | 275 | 34 | 264 | 35 | 13 |

| CKD stage ≥3b | 2 | 82 | 17 | 21 | 92 | 2 | 2 |

| CKD stage ≥4 | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| ESRD | 1 | 71 | 2 | 3 | 86 | 1 | 1 |

| Partial nephrectomy versus thermal ablation | |||||||

| CKD stage ≥3 | 10 | 880 | 181 | 20 | 571 | 158 | 28 |

| CKD stage ≥3b | 2 | 137 | 3 | 2 | 92 | 2 | 2 |

| CKD stage ≥4 | 2 | 106 | 6 | 6 | 78 | 1 | 1 |

| ESRD | 5 | 477 | 6 | 1 | 502 | 9 | 2 |

NA, not applicable.

Figure 3.

Incidence of stage 3 CKD shown to favor partial nephrectomy (PN) and thermal ablation (TA) over radical nephrectomy (RN) on meta-analysis. The comparisons shown are (A) RN versus PN, (B) RN versus TA, and (C) PN versus TA. The widths of the horizontal lines represent the 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for each study. The diamonds at the bottoms of the graphs indicate the 95% CIs. RR, risk ratio.

Again, the effect of prior CKD on categorical outcomes was uncertain given the sparsity of studies and sample sizes. One study suggested that patients with CKD stage 3 had a statistically significant worsening of CKD stage after RN compared with PN, but another study found the association to be nonsignificant on multivariable analysis (odd ratio, 1.59; 95% CI, 0.83 to 3.04) (35,44). Samples sizes for patients with CKD stage 3b or 4 undergoing surgery were even smaller and did not provide sufficient evidence for interpretation.

RN versus TA

Continuous Outcomes.

A total of seven studies assessed continuous renal functional outcomes, showing generally worse outcomes for RN compared with TA (15,30–35). The median decrease was 10.3 ml/min per 1.73 m2 lower with RN than with TA, and meta-analysis showed similar difference in mean eGFR of 9.94 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (95% CI, 7.61 to 12.26) (Figure 2, Table 1). The majority of studies (five of seven) reported statistically significant associations.

Categorical Outcomes.

Four studies compared categorical outcomes for RN versus TA, showing greater incidence of CKD stage 3 for RN (RR, 3.48; 95% CI, 1.08 to 11.15) on meta-analysis (15,31,34,45) (Figure 3). The incidence rates of higher stages of kidney dysfunction were not consistently compared (Table 2).

PN versus TA

Continuous Outcomes.

A total of 20 studies assessed continuous renal functional outcomes, showing similar changes for PN compared with TA (15,30–34,49–62) (Table 1). Meta-analyses showed a larger mean increase in creatinine of 0.07 mg/dl (95% CI, 0.00 to 0.15) and a larger mean decrease in eGFR of 1.0 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (95% CI, −0.2 to 2.1) for PN compared with TA, but neither was statistically significant (Figure 2, Supplemental Figure 1). Studies specifically evaluating T1a tumors had similar findings, and demographic factors were not associated with change in eGFR. Two studies showed similar outcomes among patients with solitary kidneys, whereas another study found larger decrease in eGFR for patients with preoperative CKD stage 3 who received TA (51,58,60). Interestingly, one study reported that higher baseline eGFR was associated with greater postoperative decrease in a series of solitary kidneys (58). For long-term trends, most studies reported that the decrease in eGFR for PN and TA postoperatively remained relatively stable, whereas two noted that PN may have had a greater decrease 1 day after surgery but then recovered to similar levels as TA by 1–6 months (30,32,49,53,61,62).

Categorical Outcomes.

A total of 11 studies assessed categorical outcomes and showed similar incidence of kidney dysfunction for PN versus TA (Table 2) (15,31,34,45,49,51,53,55,57,58,60). Meta-analyses showed similar rates of CKD stage 3 (RR, 1.14; 95% CI, 0.77 to 1.67) and ESRD (RR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.19 to 4.39) (Figure 3, Supplemental Figure 2).

AS versus Other Management Strategies

Continuous Outcomes.

Only two studies compared continuous renal functional outcomes of AS with other management strategies (34,63). One included patients ages 75 years old and older and showed a statistically significant decrease of 10 ml/min per 1.73 m2 for RN compared with 3 ml/min per 1.73 m2 for AS (63). The second study compared all four management strategies and showed greater decrease in mean eGFR for RN compared with AS, PN, and TA (34). No uncontrolled AS study reported renal functional outcomes.

Categorical Outcomes.

The same two studies assessed categorical outcomes, which were generally more favorable for AS than RN. One study showed the incidence of new CKD stage 3 to be about 5.8% for AS versus 76% for RN, whereas the other study reported 3% for AS, 2% for PN, 0% for TA, and 40% for RN at the end of follow-up (34,63).

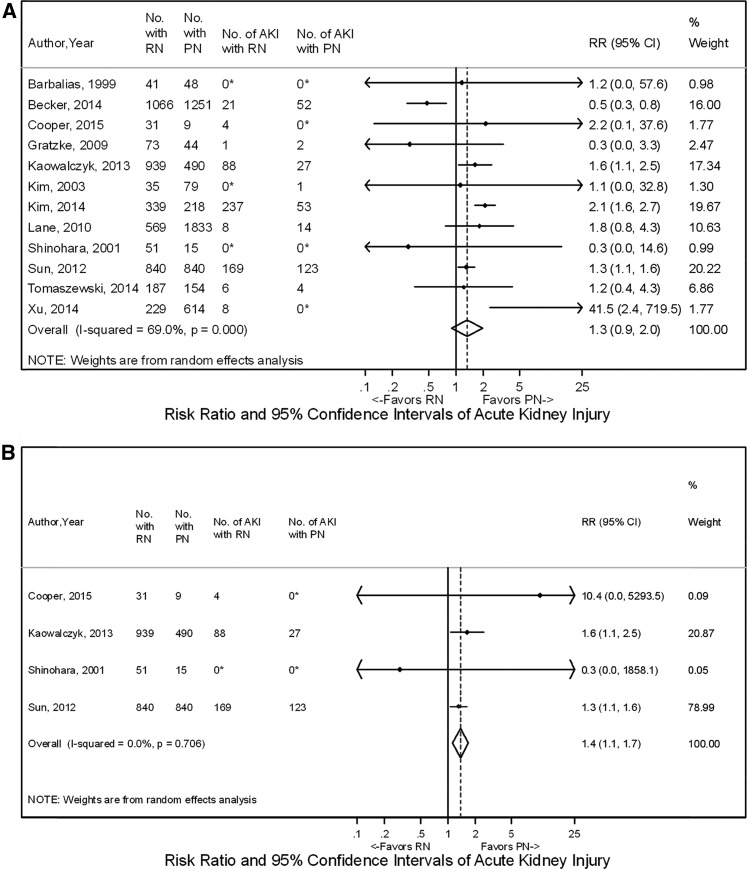

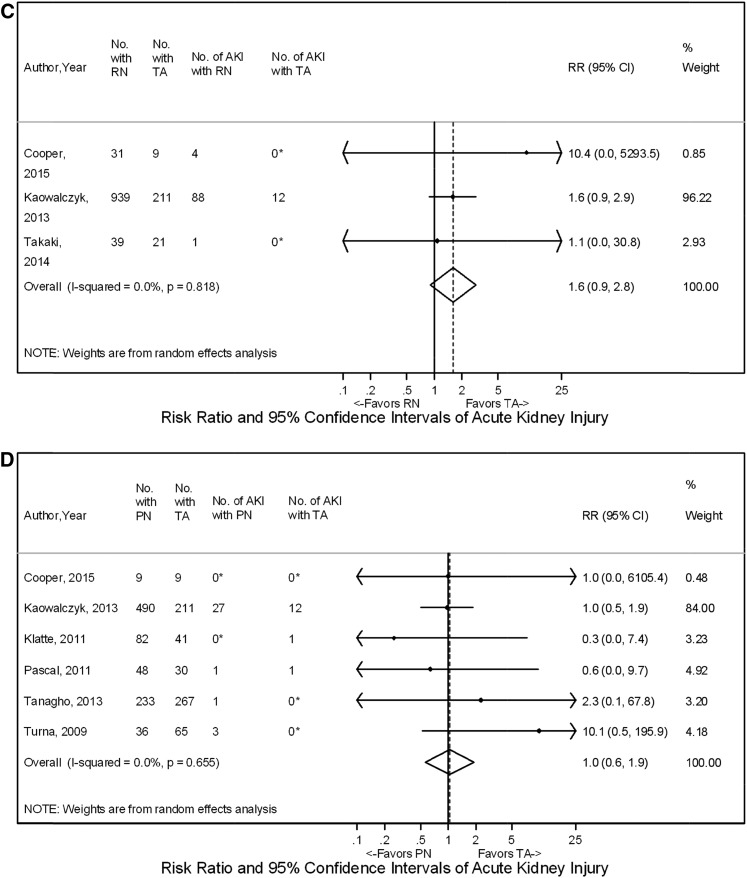

AKI

Meta-analyses showed no overall difference in the rate of AKI for RN versus PN with RR, 1.3 (95% CI, 0.9 to 2.0) (12,14,16,19,26,33,45,46,64–67) (Figure 4). However, a subset of four studies evaluating T1a tumors found that rates of AKI were higher for RN compared with PN (RR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.13 to 1.66) (33,45,46,64) (Figure 4). Similarly, three studies compared RN with TA, showing that RN was generally associated with a higher rate of AKI, but results on meta-analysis were not statistically significant (RR, 1.6; 95% CI, 0.9 to 2.8) (33,45,48) (Figure 4). Rates of AKI for PN versus TA were comparable among six studies with RR, 1.0 (95% CI, 0.6 to 1.9) (Figure 4) (33,45,49,50,57,58).

Figure 4.

Acute kidney injury shown to favor partial nephrectomy (PN) over radical nephrectomy (RN) for T1a tumors on meta-analysis but with no difference for PN, RN, and thermal ablation (TA) when comparing all included tumors. The comparisons shown are (A) RN versus PN overall, (B) RN versus PN for T1a tumors, (C) RN versus TA, and (D) PN versus TA. The widths of the horizontal lines represent the 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for each study. The diamonds at the bottoms of the graphs indicate the 95% CIs. RR, risk ratio. *Correction factors were applied.

Strength of Evidence and Risk of Bias

Strength of evidence is given with each comparison, and it was, at best, moderate or low for many outcomes and often insufficient for comparisons involving AS (Supplemental Table 1). Overall risk of bias was moderate for 30 of the 52 cohort studies (Supplemental Figure 3). Funnel plots suggested potential publication bias for the outcome of CKD stage 3 for RN versus PN but none of the other comparisons (Supplemental Figure 4).

Discussion

The evidence regarding management strategies of renal masses suspicious for localized renal cell carcinoma is almost entirely on the basis of retrospective studies and susceptible to the inherent limitations of the study design. However, a number of comparative studies included renal functional outcomes evaluating RN, PN, TA, and AS along with a randomized trial comparing RN with PN. Strength of evidence was low to moderate for most comparisons and outcomes, with notable findings of generally worse decrease in eGFR and incidence of CKD for RN compared with other management strategies and similar postoperative renal function for PN compared with TA. A few small studies compared management strategies among patients with preexisting CKD, with some suggestion that RN led to a greater incidence of progressive CKD compared with PN. AS was associated with better renal functional outcomes compared with RN, but evidence was insufficient for comparisons with PN or TA.

Current guidelines do not strictly define preference for management strategy on the basis of renal functional outcomes, and the last update to the AUA guidelines focused largely on absolute creatinine values (3,7). However, all available management strategies have shown generally favorable survival outcomes, leading to a greater focus on morbidity due to postoperative changes in renal function (4). The one randomized trial comparing RN with PN noted greater preservation of renal function with PN but counterintuitively, suggested worse overall survival for PN, despite similar cancer-specific survival (6). Critics note that the trial was underpowered for survival outcomes and experienced significant crossover. In patients with a solitary kidney, nephron-sparing approaches are preferred when possible, because RN leads to ESRD and an immediate need for hemodialysis.

By extrapolation, a dose-response rationale would argue in favor of nephron-sparing surgery for patients with preexisting CKD, where RN may be expected to have a worse effect on postoperative renal function. Surprisingly, very few studies compared RN with other modalities among patients with CKD, with some showing worse outcomes for RN compared with PN, whereas others could not show a statistically significant difference (15,22,35,44). The most clearly shown benefit was for patients with preserved kidney function (stages 1 and 2), but there were limited data on higher levels of kidney dysfunction (35). Larger studies with longer follow-up are needed to better quantify the magnitude of benefit for PN compared with RN in these patients.

In recent years, the concept of surgically induced CKD has been introduced, where a given stage of surgical CKD may have a different long-term prognosis compared with a similar degree of medical CKD. The thought is that the destruction or removal of nephrons results in a measurable decline in eGFR, whereas any progressive decline in medical CKD is a function of preexisting comorbidities. Indeed, one study showed that progressive decline in renal function was worse for an independent cohort of patients with CKD who did not have surgery compared with patients who had CKD after surgery for a renal mass (68). For patients undergoing surgery, we found an initial drop in creatinine and eGFR in the immediate postoperative period, with some recovery at up to 3–6 months followed by stabilization for up to 10–15 years (6,12,14,17,19,25,28,32,37,39,42).

Therefore, the relative long-term renal functional benefit of nephron-sparing options over RN may depend on the degree of preexisting medical comorbidities that could act as lifelong insults on renal function. For patients with CKD and poorly controlled comorbidities, the benefit of PN over RN will likely be augmented. In fact, noncancer-related mortality may be lower for surgical CKD than medical CKD (68). Evidence has suggested that renal function and cardiovascular health are intimately related, and it is known that the presence of CKD is associated with worse outcomes among patients with cardiovascular disease (69). However, the rate of cardiac events and cardiovascular-specific survival has been actively studied among patients undergoing PN and RN without definitive results (70–72).

Among nephron-sparing interventions, the comparison of PN and TA has driven notable attention of the primary options for management. TA is considered a less invasive option and generally reserved for older patients or patients with comorbidities, making surgery a less attractive option (3). TA is associated with a greater rate of persistent or recurrent local disease after a single treatment session, but the current evidence does not support significant differences in survival compared with PN (4). Notably, our meta-analyses showed similar change in eGFR, incidence of CKD, and rates of AKI for PN versus TA. Therefore, the decision to pursue PN or TA should largely be on the basis of a balance between oncologic outcomes and complication rates.

Limitations of the systematic review deserve mention. Risk of bias assessment showed moderate selection bias for most of the comparative cohort studies. Additionally, some studies were excluded due to imprecise or lack of reporting of clinical stage, making comparisons between management strategies difficult to interpret. Other potentially relevant outcomes, including proteinuria and cardiovascular disease, were generally not reported. Lastly, studies were inconsistent in the timeframe for which renal functional outcomes were reported. It has been recommended that, at a minimum, preoperative, 1 month, and 12 months values for eGFR be reported to allow comparable timeframes between studies (73).

Renal functional implications vary for different approaches to management of renal masses suspicious for localized renal cell carcinoma. Comparative studies indicate worse postoperative renal function for patients undergoing RN compared with other strategies. Renal functional outcomes are generally comparable for PN and TA, shifting the focus to a balance of oncologic outcomes and complications. Research on AS is limited and deserves further attention to identify appropriate patients who can safely maximize renal preservation without sacrificing oncologic outcomes. Long-term follow-up is needed for patients with preexisting CKD to quantify the full benefits of nephron-sparing approaches in avoiding progressive CKD and ESRD compared with RN.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Allen Zhang and Emily Little for their assistance in data abstraction. We also thank the Key Informants, Technical Expert Panel, Peer Reviewers, Dr. Steven Campbell, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Task Order Officer Dr. Aysegul Gozu for their feedback and input on the evidence report from which this article was derived.

This project was funded under contract HHSA290201200007I from the AHRQ, US Department of Health and Human Services.

The authors of this report are responsible for its content. Statements in the report should not be construed as endorsement by the AHRQ or the US Department of Health and Human Services.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.11941116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Nguyen MM, Gill IS, Ellison LM: The evolving presentation of renal carcinoma in the United States: Trends from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program. J Urol 176: 2397–2400, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Cancer Society : Cancer Facts & Figures 2016, Atlanta, GA, American Cancer Society, 2016

- 3.Campbell SC, Novick AC, Belldegrun A, Blute ML, Chow GK, Derweesh IH, Faraday MM, Kaouk JH, Leveillee RJ, Matin SF, Russo P, Uzzo RG; Practice Guidelines Committee of the American Urological Association : Guideline for management of the clinical T1 renal mass. J Urol 182: 1271–1279, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pierorazio PM, Johnson MH, Patel HD, Sozio SM, Sharma R, Iyoha E, Bass EB, Allaf ME: Management of renal masses and localized renal cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Urol 196: 989–999, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel HD, Mullins JK, Pierorazio PM, Jayram G, Cohen JE, Matlaga BR, Allaf ME: Trends in renal surgery: Robotic technology is associated with increased use of partial nephrectomy. J Urol 189: 1229–1235, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scosyrev E, Messing EM, Sylvester R, Campbell S, Van Poppel H: Renal function after nephron-sparing surgery versus radical nephrectomy: Results from EORTC randomized trial 30904. Eur Urol 65: 372–377, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pierorazio PM, Johnson MH, Patel HD, Sozio SM, Sharma R, Iyoha E, Bass EB, Allaf ME: Management of Renal Masses and Localized Renal Cancer (Prepared by the JHU Evidence-Based Practice Center under Contract No. HHSA290201200007I), Rockville, MD, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2016 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Higgins JPT, Green S: Cochrane Handbook for Systemic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0, Oxford, England, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sterne JAC, Higgins JPT, Reeves BC; The development group for ACROBAT-NRSI: A Cochrane Risk of Bias Assessment Tool: For Non-Randomized Studies of Interventions (ACROBATNRSI), Version 1.0.0, September 24, 2014. Available at: http://www.riskofbias.info. Accessed November 1, 2015

- 10.AHRQ : Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews, Rockville, MD, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2014 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Poppel H, Da Pozzo L, Albrecht W, Matveev V, Bono A, Borkowski A, Colombel M, Klotz L, Skinner E, Keane T, Marreaud S, Collette S, Sylvester R: A prospective, randomised EORTC intergroup phase 3 study comparing the oncologic outcome of elective nephron-sparing surgery and radical nephrectomy for low-stage renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol 59: 543–552, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gratzke C, Seitz M, Bayrle F, Schlenker B, Bastian PJ, Haseke N, Bader M, Tilki D, Roosen A, Karl A, Reich O, Khoder WY, Wyler S, Stief CG, Staehler M, Bachmann A: Quality of life and perioperative outcomes after retroperitoneoscopic radical nephrectomy (RN), open RN and nephron-sparing surgery in patients with renal cell carcinoma. BJU Int 104: 470–475, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Snow DC, Bhayani SB: Rapid communication: Chronic renal insufficiency after laparoscopic partial nephrectomy and radical nephrectomy for pathologic t1a lesions. J Endourol 22: 337–341, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim CS, Bae EH, Ma SK, Kweon SS, Kim SW: Impact of partial nephrectomy on kidney function in patients with renal cell carcinoma. BMC Nephrol 15: 181, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lucas SM, Stern JM, Adibi M, Zeltser IS, Cadeddu JA, Raj GV: Renal function outcomes in patients treated for renal masses smaller than 4 cm by ablative and extirpative techniques. J Urol 179: 75–79, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barbalias GA, Liatsikos EN, Tsintavis A, Nikiforidis G: Adenocarcinoma of the kidney: Nephron-sparing surgical approach vs. radical nephrectomy. J Surg Oncol 72: 156–161, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iizuka J, Kondo T, Hashimoto Y, Kobayashi H, Ikezawa E, Takagi T, Omae K, Tanabe K: Similar functional outcomes after partial nephrectomy for clinical T1b and T1a renal cell carcinoma. Int J Urol 19: 980–986, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kyung YS, You D, Kwon T, Song SH, Jeong IG, Song C, Hong B, Hong JH, Ahn H, Kim CS: The type of nephrectomy has little effect on overall survival or cardiac events in patients of 70 years and older with localized clinical t1 stage renal masses. Korean J Urol 55: 446–452, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lane BR, Fergany AF, Weight CJ, Campbell SC: Renal functional outcomes after partial nephrectomy with extended ischemic intervals are better than after radical nephrectomy. J Urol 184: 1286–1290, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li JR, Yang CR, Cheng CL, Ho HC, Chiu KY, Su CK, Chen WM, Ou YC: Partial nephrectomy in the treatment of localized renal cell carcinoma: Experience of Taichung Veterans General Hospital. J Chin Med Assoc 70: 281–285, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mariusdottir E, Jonsson E, Marteinsson VT, Sigurdsson MI, Gudbjartsson T: Kidney function following partial or radical nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma: A population-based study. Scand J Urol 47: 476–482, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Medina-Polo J, Romero-Otero J, Rodríguez-Antolín A, Domínguez-Esteban M, Passas-Martínez J, Villacampa-Aubá F, Lora-Pablos D, Gómez De La Cámara A, Díaz-González R: Can partial nephrectomy preserve renal function and modify survival in comparison with radical nephrectomy? Scand J Urol Nephrol 45: 143–150, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roos FC, Brenner W, Jäger W, Albert C, Müller M, Thüroff JW, Hampel C: Perioperative morbidity and renal function in young and elderly patients undergoing elective nephron-sparing surgery or radical nephrectomy for renal tumours larger than 4 cm. BJU Int 107: 554–561, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roos FC, Brenner W, Thomas C, Jäger W, Thüroff JW, Hampel C, Jones J: Functional analysis of elective nephron-sparing surgery vs radical nephrectomy for renal tumors larger than 4 cm. Urology 79: 607–613, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deklaj T, Lifshitz DA, Shikanov SA, Katz MH, Zorn KC, Shalhav AL: Laparoscopic radical versus laparoscopic partial nephrectomy for clinical T1bN0M0 renal tumors: Comparison of perioperative, pathological, and functional outcomes. J Endourol 24: 1603–1607, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim FJ, Rha KH, Hernandez F, Jarrett TW, Pinto PA, Kavoussi LR: Laparoscopic radical versus partial nephrectomy: Assessment of complications. J Urol 170: 408–411, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McKiernan J, Simmons R, Katz J, Russo P: Natural history of chronic renal insufficiency after partial and radical nephrectomy. Urology 59: 816–820, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chung JS, Son NH, Lee SE, Hong SK, Lee SC, Kwak C, Hong SH, Kim YJ, Kang SH, Byun SS: Overall survival and renal function after partial and radical nephrectomy among older patients with localised renal cell carcinoma: A propensity-matched multicentre study. Eur J Cancer 51: 489–497, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim JM, Song PH, Kim HT, Park TC: Comparison of partial and radical nephrectomy for pT1b renal cell carcinoma. Korean J Urol 51: 596–600, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takaki H, Yamakado K, Soga N, Arima K, Nakatsuka A, Kashima M, Uraki J, Yamada T, Takeda K, Sugimura Y: Midterm results of radiofrequency ablation versus nephrectomy for T1a renal cell carcinoma. Jpn J Radiol 28: 460–468, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deklaj T, Lifshitz DA, Shikanov SA, Kiriluk K, Katz MH, Shalhav AL, Zorn KC: Localized T1a renal lesions in the elderly: Outcomes of laparoscopic renal surgery. J Endourol 24: 397–401, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Foyil KV, Ames CD, Ferguson GG, Weld KJ, Figenshau RS, Venkatesh R, Yan Y, Clayman RV, Landman J: Longterm changes in creatinine clearance after laparoscopic renal surgery. J Am Coll Surg 206: 511–515, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cooper CJ, Teleb M, Dwivedi A, Rangel G, Sanchez LA, Laks S, Akle N, Nahleh Z: Comparative outcome of computed tomography-guided percutaneous radiofrequency ablation, partial nephrectomy or radical nephrectomy in the treatment of stage T1 renal cell carcinoma. Rare Tumors 7: 5583, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Danzig MR, Ghandour RA, Chang P, Wagner AA, Pierorazio PM, Allaf ME, McKiernan JM: Active surveillance is superior to radical nephrectomy and equivalent to partial nephrectomy for preserving renal function in patients with small renal masses: Results from the DISSRM registry. J Urol 194: 903–909, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Woldu SL, Weinberg AC, Korets R, Ghandour R, Danzig MR, RoyChoudhury A, Kalloo SD, Benson MC, DeCastro GJ, McKiernan JM: Who really benefits from nephron-sparing surgery? Urology 84: 860–867, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yasuda Y, Yuasa T, Yamamoto S, Urakami S, Ito M, Sukegawa G, Kitsukawa S, Yonese J, Fukui I: Evaluation of the RENAL nephrometry scoring system in adopting nephron-sparing surgery for cT1 renal cancer. Urol Int 90: 179–183, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miyamoto K, Inoue S, Kajiwara M, Teishima J, Matsubara A: Comparison of renal function after partial nephrectomy and radical nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma. Urol Int 89: 227–232, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brewer K, O’Malley RL, Hayn M, Safwat MW, Kim H, Underwood W 3rd , Schwaab T: Perioperative and renal function outcomes of minimally invasive partial nephrectomy for T1b and T2a kidney tumors. J Endourol 26: 244–248, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Antoniewicz AA, Poletajew S, Borówka A, Pasierski T, Rostek M, Pikto-Pietkiewicz W: Renal function and adaptive changes in patients after radical or partial nephrectomy. Int Urol Nephrol 44: 745–751, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jeon HG, Jeong IG, Lee JW, Lee SE, Lee E: Prognostic factors for chronic kidney disease after curative surgery in patients with small renal tumors. Urology 74: 1064–1068, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zorn KC, Gong EM, Orvieto MA, Gofrit ON, Mikhail AA, Msezane LP, Shalhav AL: Comparison of laparoscopic radical and partial nephrectomy: Effects on long-term serum creatinine. Urology 69: 1035–1040, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dash A, Vickers AJ, Schachter LR, Bach AM, Snyder ME, Russo P: Comparison of outcomes in elective partial vs radical nephrectomy for clear cell renal cell carcinoma of 4-7 cm. BJU Int 97: 939–945, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matin SF, Gill IS, Worley S, Novick AC: Outcome of laparoscopic radical and open partial nephrectomy for the sporadic 4 cm. or less renal tumor with a normal contralateral kidney. J Urol 168: 1356–1359, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takagi T, Kondo T, Iizuka J, Kobayashi H, Hashimoto Y, Nakazawa H, Ito F, Tanabe K: Postoperative renal function after partial nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma in patients with pre-existing chronic kidney disease: A comparison with radical nephrectomy. Int J Urol 18: 472–476, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kowalczyk KJ, Choueiri TK, Hevelone ND, Trinh QD, Lipsitz SR, Nguyen PL, Lynch JH, Hu JC: Comparative effectiveness, costs and trends in treatment of small renal masses from 2005 to 2007. BJU Int 112: E273–E280, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sun M, Bianchi M, Hansen J, Trinh QD, Abdollah F, Tian Z, Sammon J, Shariat SF, Graefen M, Montorsi F, Perrotte P, Karakiewicz PI: Chronic kidney disease after nephrectomy in patients with small renal masses: A retrospective observational analysis. Eur Urol 62: 696–703, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huang WC, Levey AS, Serio AM, Snyder M, Vickers AJ, Raj GV, Scardino PT, Russo P: Chronic kidney disease after nephrectomy in patients with renal cortical tumours: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol 7: 735–740, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takaki H, Soga N, Kanda H, Nakatsuka A, Uraki J, Fujimori M, Yamanaka T, Hasegawa T, Arima K, Sugimura Y, Sakuma H, Yamakado K: Radiofrequency ablation versus radical nephrectomy: Clinical outcomes for stage T1b renal cell carcinoma. Radiology 270: 292–299, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Klatte T, Mauermann J, Heinz-Peer G, Waldert M, Weibl P, Klingler HC, Remzi M: Perioperative, oncologic, and functional outcomes of laparoscopic renal cryoablation and open partial nephrectomy: A matched pair analysis. J Endourol 25: 991–997, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tanagho YS, Bhayani SB, Kim EH, Figenshau RS: Renal cryoablation versus robot-assisted partial nephrectomy: Washington University long-term experience. J Endourol 27: 1477–1486, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mues AC, Korets R, Graversen JA, Badani KK, Bird VG, Best SL, Cadeddu JA, Clayman RV, McDougall E, Barwari K, Laguna P, de la Rosette J, Kavoussi L, Okhunov Z, Munver R, Patel SR, Nakada S, Tsivian M, Polascik TJ, Shalhav A, Shingleton WB, Johnson EK, Wolf JS Jr., Landman J: Clinical, pathologic, and functional outcomes after nephron-sparing surgery in patients with a solitary kidney: A multicenter experience. J Endourol 26: 1361–1366, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Youn CS, Park JM, Lee JY, Song KH, Na YG, Sul CK, Lim JS: Comparison of laparoscopic radiofrequency ablation and open partial nephrectomy in patients with a small renal mass. Korean J Urol 54: 603–608, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guillotreau J, Haber GP, Autorino R, Miocinovic R, Hillyer S, Hernandez A, Laydner H, Yakoubi R, Isac W, Long JA, Stein RJ, Kaouk JH: Robotic partial nephrectomy versus laparoscopic cryoablation for the small renal mass. Eur Urol 61: 899–904, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Desai MM, Aron M, Gill IS: Laparoscopic partial nephrectomy versus laparoscopic cryoablation for the small renal tumor. Urology 66[5 Suppl]: 23–28, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Emara AM, Kommu SS, Hindley RG, Barber NJ: Robot-assisted partial nephrectomy vs laparoscopic cryoablation for the small renal mass: Redefining the minimally invasive ‘gold standard’. BJU Int 113: 92–99, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Haramis G, Graversen JA, Mues AC, Korets R, Rosales JC, Okhunov Z, Badani KK, Gupta M, Landman J: Retrospective comparison of laparoscopic partial nephrectomy versus laparoscopic renal cryoablation for small (<3.5 cm) cortical renal masses. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 22: 152–157, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Haber GP, Lee MC, Crouzet S, Kamoi K, Gill IS: Tumour in solitary kidney: Laparoscopic partial nephrectomy vs laparoscopic cryoablation. BJU Int 109: 118–124, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Turna B, Kaouk JH, Frota R, Stein RJ, Kamoi K, Gill IS, Novick AC: Minimally invasive nephron sparing management for renal tumors in solitary kidneys. J Urol 182: 2150–2157, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Faddegon S, Ju T, Olweny EO, Liu Z, Han WK, Yin G, Tan YK, Gahan J, Bedir S, Ma YB, Park SK, Raj GV, Cadeddu JA: A comparison of long term renal functional outcomes following partial nephrectomy and radiofrequency ablation. Can J Urol 20: 6785–6789, 2013 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mitchell CR, Atwell TD, Weisbrod AJ, Lohse CM, Boorjian SA, Leibovich BC, Thompson RH: Renal function outcomes in patients treated with partial nephrectomy versus percutaneous ablation for renal tumors in a solitary kidney. J Urol 186: 1786–1790, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kiriluk KJ, Shikanov SA, Steinberg GD, Shalhav AL, Lifshitz DA: Laparoscopic partial nephrectomy versus laparoscopic ablative therapy: A comparison of surgical and functional outcomes in a matched control study. J Endourol 25: 1867–1872, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chang X, Zhang F, Liu T, Ji C, Zhao X, Yang R, Yan X, Wang W, Guo H: Radio frequency ablation versus partial nephrectomy for clinical T1b renal cell carcinoma: Long-term clinical and oncologic outcomes. J Urol 193: 430–435, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lane BR, Abouassaly R, Gao T, Weight CJ, Hernandez AV, Larson BT, Kaouk JH, Gill IS, Campbell SC: Active treatment of localized renal tumors may not impact overall survival in patients aged 75 years or older. Cancer 116: 3119–3126, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shinohara N, Harabayashi T, Sato S, Hioka T, Tsuchiya K, Koyanagi T: Impact of nephron-sparing surgery on quality of life in patients with localized renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol 39: 114–119, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xu H, Ding Q, Jiang H-W: Fewer complications after laparoscopic nephrectomy as compared to the open procedure with the modified Clavien classification system--A retrospective analysis from southern China. World J Surg Oncol 12: 242, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Becker A, Ravi P, Roghmann F, Trinh QD, Tian Z, Larouche A, Kim S, Shariat SF, Kluth L, Dahlem R, Fisch M, Graefen M, Eichelberg C, Karakiewicz PI, Sun M: Laparoscopic radical nephrectomy vs laparoscopic or open partial nephrectomy for T1 renal cell carcinoma: Comparison of complication rates in elderly patients during the initial phase of adoption. Urology 83: 1285–1291, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tomaszewski JJ, Uzzo RG, Kutikov A, Hrebinko K, Mehrazin R, Corcoran A, Ginzburg S, Viterbo R, Chen DY, Greenberg RE, Smaldone MC: Assessing the burden of complications after surgery for clinically localized kidney cancer by age and comorbidity status. Urology 83: 843–849, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Demirjian S, Lane BR, Derweesh IH, Takagi T, Fergany A, Campbell SC: Chronic kidney disease due to surgical removal of nephrons: Relative rates of progression and survival. J Urol 192: 1057–1062, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Herzog CA, Asinger RW, Berger AK, Charytan DM, Díez J, Hart RG, Eckardt KU, Kasiske BL, McCullough PA, Passman RS, DeLoach SS, Pun PH, Ritz E: Cardiovascular disease in chronic kidney disease. A clinical update from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int 80: 572–586, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Patel HD, Kates M, Pierorazio PM, Allaf ME: Balancing cardiovascular (CV) and cancer death among patients with small renal masses: Modification by CV risk. BJU Int 115: 58–64, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chung SD, Huang CY, Wu ST, Lin HC, Huang CC, Kao LT: Nephrectomy type was not associated with a subsequent risk of coronary heart disease: A population-based study. PLoS One 11: e0163253, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Huang WC, Elkin EB, Levey AS, Jang TL, Russo P: Partial nephrectomy versus radical nephrectomy in patients with small renal tumors--Is there a difference in mortality and cardiovascular outcomes? J Urol 181: 55–61, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Patel HD, Iyoha E, Pierorazio PM, Sozio SM, Johnson MH, Sharma R, Bass EB, Allaf ME: A systematic review of research gaps in the evaluation and management of localized renal masses. Urology 98: 14–20, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.