Abstract

Background and objectives

Despite significant morbidity and mortality associated with ESRD, these patients receive palliative care services much less often than patients with other serious illnesses, perhaps because they are perceived as having less need for such services. We compared characteristics and outcomes of hospitalized patients in the United States who had a palliative care consultation for renal disease versus other serious illnesses.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

In this observational study, we used data collected by the Palliative Care Quality Network, a national palliative care quality improvement collaborative. The 23-item Palliative Care Quality Network core dataset includes demographics, processes of care, and clinical outcomes of all hospitalized patients who received a palliative care consultation between December of 2012 and March of 2016.

Results

The cohort included 33,183 patients, of whom 1057 (3.2%) had renal disease as the primary reason for palliative care consultation. Mean age was 71.9 (SD=16.8) or 72.8 (SD=15.2) years old for those with renal disease or other illnesses, respectively. At the time of consultation, patients with renal disease or other illnesses had similarly low mean Palliative Performance Scale scores (36.0% versus 34.9%, respectively; P=0.08) and reported similar moderate to severe anxiety (14.9% versus 15.3%, respectively; P=0.90) and nausea (5.9% versus 5.9%, respectively; P>0.99). Symptoms improved similarly after consultation regardless of diagnosis (P≥0.50), except anxiety, which improved more often among those with renal disease (92.0% versus 66.0%, respectively; P=0.002). Although change in code status was similar among patients with renal disease versus other illnesses, from over 60% full code initially to 30% full code after palliative care consultation, fewer patients with renal disease were referred to hospice than those with other illnesses (30.7% versus 37.6%, respectively; P<0.001).

Conclusions

Hospitalized patients with renal disease referred for palliative care consultation had similar palliative care needs, improved symptom management, and clarification of goals of care as those with other serious illnesses.

Keywords: palliative care; end-stage renal disease; advance care planning; Adolescent; Anxiety; Demography; Hospice Care; Hospices; Humans; Kidney Diseases; Kidney Failure, Chronic; Nausea; Palliative Care; Patient Care Planning; Quality Improvement; Quality of Health Care; Referral and Consultation; Retrospective Studies; United States

Introduction

ESRD is a devastating illness. The adjusted mortality rate of ESRD is nearly double that of adults with cancer, congestive heart failure, and stroke (1), and the physical and psychologic burdens of standard maintenance dialysis, including fatigue, dizziness, dialysis access–related procedures, and travel to and from dialysis, are highly prevalent (2–4). The burdens of dialysis are particularly demanding for older patients, although dialysis may not provide a survival benefit over conservative management (5,6).

Nevertheless, dialysis is often considered a routine and life-saving intervention regardless of age and prognosis (7) and often means that patients are subjected to patterns of intensive health care utilization (8). In a study of elderly Medicare beneficiaries, Wong et al. (9) found that, in the last month of life, patients on dialysis spent twice as many days in the hospital as patients with cancer (9.8 versus 5.1 days, respectively) and more than three times as often had undergone an intensive procedure, such as mechanical ventilation, feeding tube placement, and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (29.0% versus 9%, respectively).

With this pattern of aggressive and intensive care as the norm, patients with ESRD may be perceived as having less need for palliative care services, such as symptom management and advance care planning. This assertion is supported by a recent large national cohort study of nearly all patients dying within Veterans Administration facilities over a 3-year period, in which patients with ESRD were found to have had palliative care consultation or do not resuscitate orders much less often than patients with dementia or cancer (10). Using data collected by interdisciplinary palliative care teams that are members of the Palliative Care Quality Network (PCQN), a national palliative care quality improvement collaborative, we compared characteristics and outcomes of hospitalized patients in the United States who had a palliative care consultation for renal disease with those of patients with other conditions. Given existing data on the burdens of ESRD, we sought to compare rates of symptom severity and improvement and needs for advance care planning between patients referred for palliative care consultation because of renal disease and those with other serious illnesses.

Materials and Methods

Hospitals

The PCQN is a national consortium of interdisciplinary palliative care teams. As of March of 2016, there were 54 PCQN members from predominantly not-for-profit hospitals in 11 states. Thirty-eight hospitals reported patient-level data.

Dataset

The 23-item PCQN core dataset includes demographics, processes of care, and patient-level clinical outcomes. In the PCQN dataset, the palliative care clinician records the primary condition that prompted the palliative care consultation request. The possible conditions include renal disease, cancer, heart disease, pulmonary disease, hematologic disease, neurologic disease, and others. In this study, we compared those patients for whom renal disease was the primary condition that prompted the consultation with those with the most common other serious illnesses: cancer, heart disease, pulmonary disease, and neurologic disease.

PCQN members collect symptom severity scores for pain, anxiety, shortness of breath, and nausea daily from patients able to report on a four-point scale: none (0), mild (1), moderate (2), or severe (3). We defined improvement as the percentage of patients who rated their symptom as moderate or severe at the initial assessment and reported improvement of at least one point at the second assessment when the second assessment occurred within 72 hours. The PCQN dataset also includes information about code status, advance directive availability and completion, family meetings, and disposition. Twenty-six hospitals (68%) collected code status after consultation. The Palliative Performance Scale, a valid and reliable tool for assessing prognosis as well as identifying and tracking potential care needs of patients (11–13), was assessed for every patient. The scale is scored 100%–0% on the basis of five domains—ambulation, activity-level evidence of disease, self-care, intake, and level of consciousness. Patients with a score of 50% spend more than one half of their time sitting or lying and need considerable assistance with self-care. Those with a score of 30% are completely bed bound, have reduced intake, and require full assistance for self-care, whereas patients with a score of 10% may be in a coma and have intake reduced to mouth care.

The data for this study were extracted on March 16, 2016 and include the palliative care consultation records of 33,183 patients from 38 palliative care programs that received consultation requests between the dates of December 12, 2012 and March 15, 2016. The study was reviewed and approved by the University of California, San Francisco Institutional Review Board (16–18596).

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics, including frequencies, means, and SDs, were used to examine the distribution of measures. We used chi-squared analysis to examine bivariate associations between categorical variables and ANOVA to examine associations between categorical and continuous variables. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 22 for Mac (14) was used to conduct all analyses.

Results

The cohort included 33,183 patients, of whom 1057 (3.2%) had renal disease as the primary reason for consultation. Patients with renal disease were more often men (54.5% versus 48.5%, respectively) and in step-down or intensive care units (59.2% versus 48.7%, respectively) than patients with other serious illnesses but were of similar age (mean of 72.8 versus 71.9 years old, respectively) (Table 1). Patients had similar code status and prevalence of documented advance care planning at time of palliative care consult, regardless of whether renal disease or other serious illnesses prompted consultation.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics at time of referral to palliative care consultation by condition prompting palliative care consultation

| Characteristic | Condition Prompting Palliative Care Consultation | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Renal Disease | Other Serious Illnessesa | ||

| Mean age (SD), yr | 72.8 (15.2) | 71.9 (16.8) | 0.06 |

| Sex (men), % (n) | 54.5 (576) | 48.5 (15,074) | <0.001 |

| Referral location, % (n) | <0.001 | ||

| Medical/surgical | 36.4 (383) | 43.5 (13,439) | |

| Critical care | 22.2 (232) | 23.2 (7157) | |

| Telemetry/step down | 37.0 (390) | 25.5 (7869) | |

| Other | 4.4 (48) | 7.8 (2422) | |

| Reason for referral, % (n) | |||

| Goals of care/advanced care planning | 81.5 (859) | 74.2 (23,013) | <0.001 |

| Pain management | 14.6 (154) | 20.5 (6343) | <0.001 |

| Support for patient/family | 14.2 (150) | 18.5 (5729) | <0.001 |

| Hospice referral/discussion | 17.6 (186) | 17.7 (5498) | 0.95 |

| Other symptom management | 10.0 (105) | 15.5 (4822) | <0.001 |

| Comfort care | 6.5 (69) | 8.0 (2477) | 0.09 |

| Withdrawal of interventions | 3.3 (35) | 4.0 (1245) | 0.26 |

| Assess for transfer to comfort care | 2.0 (21) | 2.2 (691) | 0.60 |

| No reason given | 2.2 (23) | 1.4 (444) | 0.05 |

| POLST at time of consult (yes), % (n) | 11.5 (1117) | 10.1 (2996) | 0.20 |

| Advance directives at consult (yes), % (n) | 21.3 (217) | 20.4 (6066) | 0.50 |

| Mean time between admission and palliative care consultation request (95% CI), d | 5.1 (4.1 to 6.1) | 4.7 (4.6 to 4.9) | 0.40 |

| Patients receiving a request for palliative care referral within 24 h of admission, % (n) | 59.3 (619) | 56.4 (17,185) | 0.06 |

| Mean palliative performance scale score (95% CI), % | 36.0 (34.9 to 37.2) | 34.9 (34.7 to 35.1) | 0.08 |

| Symptoms at time of consult (moderate/severe), % (n) | |||

| Pain | 24.7 (118) | 30.9 (4737) | 0.004 |

| Anxiety | 14.9 (66) | 15.3 (2184) | 0.90 |

| Nausea | 5.9 (27) | 5.9 (871) | >0.99 |

| Dyspnea | 30.5 (39) | 41.6 (1862) | 0.01 |

POLST, physician’s orders for life-sustaining treatment; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Other serious illnesses include cancer, heart disease, pulmonary disease, and neurologic disease.

Mean Palliative Performance Scale scores suggested that patients were nearly completely bed bound, had reduced intake, and required full assistance for self-care, and they were similar among patients referred for renal disease versus other serious illnesses (36.0% versus 34.9%, respectively; P=0.08). Similar percentages of patients with renal disease versus other serious illnesses reported moderate to severe anxiety (14.9% versus 15.3%, respectively; P=0.90) and nausea (5.9% versus 5.9%, respectively; P>0.99) at the time of consultation. Those with renal disease were less likely to report having moderate to severe pain (24.7% versus 30.9%, respectively; P=0.004) and dyspnea (30.5% versus 41.6%, respectively; P=0.01) than those with other serious illnesses. Goals of care and advanced care planning were the reasons for palliative care consult more often for patients with renal disease than those with other serious illnesses (81.5% versus 74.2%, respectively; P<0.001). De-escalation of care (i.e., withdrawal of interventions or transition to comfort care or hospice) as the reason for consultation was reported equally for patients referred for renal disease or other serious illnesses.

Outcomes of palliative care consultation are shown in Table 2. Patients were equally likely to report improvement of pain, nausea, and dyspnea, regardless of whether renal disease or other serious illness prompted consultation. However, those with renal disease were significantly more likely to report an improvement in their anxiety than those with other serious illnesses (92.0% versus 66.0%, respectively; P<0.01). The vast majority of patients were discharged alive regardless of diagnosis, but fewer patients with renal disease were referred to hospice (30.7% versus 37.6%, respectively; P<0.001).

Table 2.

Patient characteristics after palliative care consultation by condition prompting palliative care consultation

| Characteristic | Condition Prompting Palliative Care Consultation, % (n) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Renal Disease | Other Serious Illnessesa | ||

| Symptom improvement from first to second assessmentb | |||

| Pain | 66.7 (38) | 76.6 (2056) | 0.90 |

| Anxiety | 92.0 (23) | 66.0 (819) | <0.01 |

| Nausea | 71.4 (10) | 78.4 (462) | 0.50 |

| Dyspnea | 69.2 (9) | 68.0 (650) | 0.90 |

| Family meetings | 0.66 | ||

| No meetings | 26.7 (249) | 25.1 (7025) | |

| One meeting | 45.3 (422) | 45.4 (12,678) | |

| Two or more meetings | 28.0 (261) | 29.5 (8251) | |

| Discharged alive | 78.7 (821) | 77.4 (23,642) | 0.34 |

| Referred to hospice | 30.7 (210) | 37.6 (7571) | <0.001 |

Other serious illnesses include cancer, heart disease, pulmonary disease, and neurologic disease.

Includes patients reporting moderate to severe symptoms at first assessment who report improvement by at least one category at the second assessment that occurred within 72 hours of the first assessment.

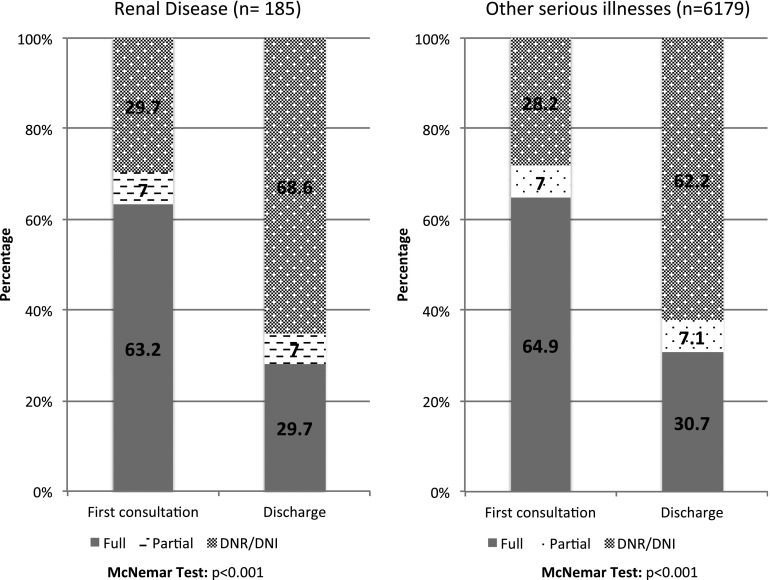

Among patients with code status available at initial consultation and discharge (n=6364), there were no significant differences in the code status of patients with renal disease versus other serious illnesses at the first consultation (P=0.70) or discharge (P=0.20) (Figure 1). At the time of referral to palliative care, nearly two thirds (63.2%) of patients with renal disease were full code, and less than one third were do not resuscitate/do not intubate (DNR/DNI) (29.7%). Similar percentages of patients with other serious illnesses had full code and DNR/DNI code status at initial consultation (64.9% and 30.7%, respectively). At discharge, a significant number of patients in both groups had changed code status, with less than one third of patients with renal disease still full code (29.7%) and over two thirds DNR/DNI (68.6%), similar to the percentages of patients with other serious illnesses (30.7% full code and 62.2% DNR/DNI).

Figure 1.

Change in code status from time of palliative care consultation to hospital discharge for patients with renal disease versus other serious illnesses among patients with available code status at both time points (n=6364). There were no significant differences in the code status of patients with renal disease versus other serious illnesses (which include cancer, heart disease, pulmonary disease, and neurologic disease) at the first consultation (P=0.70) or discharge (P=0.20; P value is chi-squared test). DNI, do not intubate; DNR, do not resuscitate.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study examining the characteristics of and outcomes for hospitalized patients with renal disease versus those with other serious illnesses who received palliative care consultation. The average Palliative Performance Scale score was low for patients with renal disease and those with other serious illnesses, reflecting that patients referred for palliative care consultation in the hospital are very sick. Despite this poor functional status, three quarters of patients in both groups were discharged alive, although patients with renal disease were less likely to be referred to hospice.

The fact that fewer patients with renal disease were referred to hospice may reflect that Medicare, which serves as the payer for 90% of patients on dialysis, will only pay for dialysis and the hospice benefit at the same time if the patient’s terminal condition is determined (by Medicare) to be due to a condition other than ESRD (15). Alternatively, this finding may reflect the widely held perception and hope among providers, patients, and families that dialysis treatment automatically confers a survival benefit for everyone, thus precluding the need for hospice. This perception is supported by a recent study that found that the majority of patients with advanced CKD received or were preparing to receive dialysis regardless of age or comorbidity (16), despite a growing body of observational studies from Europe showing that elderly patients with serious illness in addition to ESRD who receive conservative management without dialysis may live just as long as those who do have dialysis (6,17–22).

We also found significant symptom prevalence and severity among patients with renal disease and those with other serious illnesses. Similar proportions of those with renal disease and those with other serious illnesses had moderate to severe anxiety and nausea, but those with renal disease were less likely to be referred for palliative care consultation for symptom management. Although a smaller percentage of patients with renal disease had moderate to severe pain and dyspnea, they were equally likely to improve, and a higher percentage of patients with renal disease reported improvement in anxiety.

Patients with renal disease were also similar to patients with other serious illnesses in terms of advance care planning. In fact, patients with renal disease were more likely to have goals of care as a reason for consultation, and a significant proportion changed code status to DNR/DNI, mirroring findings in those with other serious illnesses. These findings suggest that consultation with a palliative care team may have helped patients express their true preferences for care and ultimately, avoid interventions that they did not want. This, in turn, may lead to greater family satisfaction in end of life care as suggested in the study by Wachterman et al. (10), which found that family-reported quality of end of life care was significantly better for patients with cancer and dementia than those with ESRD, largely due to lower rates of palliative care consultation and advance care planning for patients with ESRD.

Our study is not without limitations. By virtue of examining only patients who had palliative care consultation, the cohort may have selected for the sickest patients with ESRD and may not be reflective of the needs of the entire hospitalized ESRD population. This concern is minimized, because the proportion of patients with ESRD included in this study (3.5%) is similar to the proportion of patients with ESRD among all adult (18+ years old) non-neonatal, nonmaternal 2013 hospitalizations (3.8%) (23). Also, patients were defined as having renal disease if it was determined by the palliative care team to be the primary diagnosis for palliative care consultation. We presumed that this applied only to patients with ESRD or those with acute, irreversible kidney failure at the end of life. Although this diagnosis could theoretically include patients with earlier stages of CKD, these diagnoses as primary among patients needing a palliative care consult are highly unlikely.

Despite these limitations, our study shows that hospitalized patients with renal disease had similar palliative care needs and similarly improved symptom management and clarification of goals of care with palliative care consultation as those with other serious diagnoses. Utilization of inpatient palliative care services for patients with ESRD (for example, through routine screening at admission for identification of patients who would be appropriate for palliative care consultation) could potentially result in less unwanted aggressive and invasive care for this population.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Palliative Care Quality Network (PCQN) members who strive to improve the care of their patients.

V.G. was supported by grant 1K23DK093710-01A1 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease and the Harold Amos Medical Faculty Development Program of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. D.O., S.P., and the PCQN are supported by grants from the Archstone Foundation, the California HealthCare Foundation, the Kettering Family Foundation, the Stupski Foundation, and the UniHealth Foundation.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.US Renal Data System : USRDS 2015 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States, Bethesda, MD, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen LM, Moss AH, Weisbord SD, Germain MJ: Renal palliative care. J Palliat Med 9: 977–992, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feldman R, Berman N, Reid MC, Roberts J, Shengelia R, Christianer K, Eiss B, Adelman RD: Improving symptom management in hemodialysis patients: Identifying barriers and future directions. J Palliat Med 16: 1528–1533, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weisbord SD, Fried LF, Arnold RM, Fine MJ, Levenson DJ, Peterson RA, Switzer GE: Prevalence, severity, and importance of physical and emotional symptoms in chronic hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 2487–2494, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foote C, Kotwal S, Gallagher M, Cass A, Brown M, Jardine M: Survival outcomes of supportive care versus dialysis therapies for elderly patients with end-stage kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nephrology (Carlton) 21: 241–253, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verberne WR, Geers AB, Jellema WT, Vincent HH, van Delden JJ, Bos WJ: Comparative survival among older adults with advanced kidney disease managed conservatively versus with dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 633–640, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thorsteinsdottir B, Swetz KM, Albright RC: The ethics of chronic dialysis for the older patient: Time to reevaluate the norms. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 2094–2099, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong SP, Kreuter W, O’Hare AM: Healthcare intensity at initiation of chronic dialysis among older adults. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 143–149, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong SP, Kreuter W, O’Hare AM: Treatment intensity at the end of life in older adults receiving long-term dialysis. Arch Intern Med 172: 661–663, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wachterman MW, Pilver C, Smith D, Ersek M, Lipsitz SR, Keating NL: Quality of end-of-life care provided to patients with different serious illnesses. JAMA Intern Med 176: 1095–1102, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson F, Downing GM, Hill J, Casorso L, Lerch N: Palliative performance scale (PPS): A new tool. J Palliat Care 12: 5–11, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morita T, Tsunoda J, Inoue S, Chihara S: Validity of the palliative performance scale from a survival perspective. J Pain Symptom Manage 18: 2–3, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Virik K, Glare P: Validation of the palliative performance scale for inpatients admitted to a palliative care unit in Sydney, Australia. J Pain Symptom Manage 23: 455–457, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.IBM Corp.: IBM SPSS Statistics for Macintosh, Version 22.0, Armonk, NY, IBM Corp., 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Medicare: Medicare Benefit Policy Manual (CMS Publication 100-02), 2016. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/bp102c11.pdf. Accessed October 4, 2016

- 16.Wong SP, Hebert PL, Laundry RJ, Hammond KW, Liu CF, Burrows NR, O’Hare AM: Decisions about renal replacement therapy in patients with advanced kidney disease in the US department of veterans affairs, 2000-2011 [published online ahead of print September 22, 2016]. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol doi: 10.2215/CJN.03760416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carson RC, Juszczak M, Davenport A, Burns A: Is maximum conservative management an equivalent treatment option to dialysis for elderly patients with significant comorbid disease? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 1611–1619, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chandna SM, Da Silva-Gane M, Marshall C, Warwicker P, Greenwood RN, Farrington K: Survival of elderly patients with stage 5 CKD: Comparison of conservative management and renal replacement therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 26: 1608–1614, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hussain JA, Mooney A, Russon L: Comparison of survival analysis and palliative care involvement in patients aged over 70 years choosing conservative management or renal replacement therapy in advanced chronic kidney disease. Palliat Med 27: 829–839, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murtagh FE, Marsh JE, Donohoe P, Ekbal NJ, Sheerin NS, Harris FE: Dialysis or not? A comparative survival study of patients over 75 years with chronic kidney disease stage 5. Nephrol Dial Transplant 22: 1955–1962, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Connor NR, Kumar P: Conservative management of end-stage renal disease without dialysis: A systematic review. J Palliat Med 15: 228–235, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tam-Tham H, Thomas CM: Does the evidence support conservative management as an alternative to dialysis for older patients with advanced kidney disease? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 552–554, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: National Statistics, 2013. Available at: http://hcupnet.ahrq.gov/. Accessed July 31, 2016