Genetic variability in cerebellar alcohol/ethanol sensitivity (ethanol-induced ataxia) predicts ethanol consumption phenotype in rodents and humans, but the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying genetic differences are largely unknown. Here it is demonstrated that recreational concentrations of alcohol (10–30 mM) enhance glycinergic and GABAergic inhibition of unipolar brush cells through increases in glycine/GABA release and postsynaptic enhancement of glycine receptor-mediated responses. Ethanol effects varied across rodent genotypes parallel to ethanol consumption and motor sensitivity phenotype.

Keywords: cerebellum, alcohol, unipolar brush cell

Abstract

Variation in cerebellar sensitivity to alcohol/ethanol (EtOH) is a heritable trait associated with alcohol use disorder in humans and high EtOH consumption in rodents, but the underlying mechanisms are poorly understood. A recently identified cellular substrate of cerebellar sensitivity to EtOH, the GABAergic system of cerebellar granule cells (GCs), shows divergent responses to EtOH paralleling EtOH consumption and motor impairment phenotype. Although GCs are the dominant afferent integrator in the cerebellum, such integration is shared by unipolar brush cells (UBCs) in vestibulocerebellar lobes. UBCs receive both GABAergic and glycinergic inhibition, both of which may mediate diverse neurological effects of EtOH. Therefore, the impact of recreational concentrations of EtOH (~10–50 mM) on GABAA receptor (GABAAR)- and glycine receptor (GlyR)-mediated spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic currents (sIPSCs) of UBCs in cerebellar slices was characterized. Sprague-Dawley rat (SDR) UBCs exhibited sIPSCs mediated by GABAARs, GlyRs, or both, and EtOH dose-dependently (10, 26, 52 mM) increased their frequency and amplitude. EtOH increased the frequency of glycinergic and GABAergic sIPSCs and selectively enhanced the amplitude of glycinergic sIPSCs. This GlyR-specific enhancement of sIPSC amplitude resulted from EtOH actions at presynaptic Golgi cells and via protein kinase C-dependent direct actions on postsynaptic GlyRs. The magnitude of EtOH-induced increases in UBC sIPSC activity varied across SDRs and two lines of mice, in parallel with their respective alcohol consumption/motor impairment phenotypes. These data indicate that Golgi cell-to-UBC inhibitory synapses are targets of EtOH, which acts at pre- and postsynaptic sites, via Golgi cell excitation and direct GlyR enhancement.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Genetic variability in cerebellar alcohol/ethanol sensitivity (ethanol-induced ataxia) predicts ethanol consumption phenotype in rodents and humans, but the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying genetic differences are largely unknown. Here it is demonstrated that recreational concentrations of alcohol (10–30 mM) enhance glycinergic and GABAergic inhibition of unipolar brush cells through increases in glycine/GABA release and postsynaptic enhancement of glycine receptor-mediated responses. Ethanol effects varied across rodent genotypes parallel to ethanol consumption and motor sensitivity phenotype.

alcohol use disorder (AUD) is a leading cause of death and disability (SAMHSA 2013) predilection for which is 50–60% genetically determined (Agrawal and Lynskey 2008; Hill 2010; Morozova et al. 2014; Prescott and Kendler 1999). Although the details of such genetic predilection are complex, studies of humans consistently report a heritable association between reduced sensitivity to ethanol (EtOH)-induced cerebellum-dependent motor impairment, family history of AUD, and actual development of AUD (Lex et al. 1988; Newlin and Thomson 1990; Quinn and Fromme 2011; Schuckit 1985, 1994; Schuckit et al. 1996). Similarly, in preclinical models of AUD, many rodent genotypes that voluntarily consume high volumes of EtOH [e.g., C57BL/6 (B6) mice] also display reduced cerebellar sensitivity to EtOH relative to low-EtOH-consuming genotypes [e.g., DBA/2 (D2) mice] (Bell et al. 2001; Gallaher et al. 1996; Malila 1978; Yoneyama et al. 2008). Collectively, these studies indicate that low cerebellar sensitivity to EtOH is a heritable phenotype that is a risk factor for AUD, but little is known about the mechanisms that mediate this association.

Evidence suggests that the impact of recreational concentrations of EtOH (10–20 mM) on the cerebellar cortical circuit are largely limited to the Golgi cell-granule cell (GC) (Carta et al. 2004; Belmeguenai et al. 2008; Kaplan et al. 2013, 2016b) and inferior olivary neuron/climbing fiber-Purkinje cell (He et al. 2013; Welsh et al. 2011) synapses, which impact spatiotemporal integration and cerebellar learning, respectively. In recordings from GCs in cerebellar slices from low-EtOH-consuming rodents [e.g., Sprague-Dawley rats (SDRs) and D2 mice], EtOH increases both phasic and tonic GABAA receptor (GABAAR) currents (Botta et al. 2007a, 2007b; Carta et al. 2004; Kaplan et al. 2013, 2016b), which suppresses transmission through the cerebellar cortex (Kaplan et al. 2016b) and induces ataxia (Dar 2015; Hanchar et al. 2005). In contrast, in GCs from high-EtOH-consuming rodents (e.g., B6 mice and prairie voles) that tend to be resistant to EtOH-induced ataxia (Gallaher et al. 1996; Yoneyama et al. 2008), EtOH suppresses tonic GABAAR currents (Kaplan et al. 2013, 2016a). Importantly, counteracting this EtOH-induced suppression by injecting a GABAAR agonist into the cerebellum of B6 mice in vivo significantly reduces EtOH consumption, suggesting that divergent impacts of EtOH on cerebellar GABAergic transmission play a causative role in EtOH consumption phenotype (Kaplan et al. 2016b). Mechanistically, EtOH-induced enhancement of GC tonic GABAAR currents results from EtOH-induced increases in presynaptic GABAergic Golgi cell firing frequency, thereby increasing vesicular release of GABA, which generates increased phasic inhibitory postsynaptic current (IPSC) frequency, but also an accumulation of extrasynaptic GABA that increases tonic GABAAR current magnitude (Botta et al. 2010, 2012; Carta et al. 2004; Kaplan et al. 2013; Mohr et al. 2013). Accordingly, EtOH excites Golgi cells in low-EtOH-consuming genotypes but not in high-EtOH-consuming genotypes, thereby highlighting the Golgi cell-to-GC synapse as a crucial determinant of cerebellum-related EtOH phenotype (Kaplan et al. 2013).

However, GCs are not the only target of Golgi cell inhibition. In particular, within the GC layer of vestibulocerebellar lobes, unipolar brush cells (UBCs) also receive inhibition from Golgi cells (Dugué et al. 2005; Rousseau et al. 2012) and therefore may further contribute to the behavioral impact of EtOH actions on Golgi cells in the context of EtOH-induced ataxia and EtOH consumption. Furthermore, UBCs are unusual in that their phasic inhibitory synaptic currents are mediated by both GABAARs and glycine receptors (GlyRs) (Dugué et al. 2005; Rousseau et al. 2012), the latter being absent in GCs despite being innervated by the same Golgi cells (Ottersen et al. 1988). The presence of GlyR-mediated IPSCs in UBCs adds further interest to their response to EtOH, because the glycinergic system is sensitive to recreational concentrations of EtOH and is implicated in various EtOH-related phenotypes (Aguayo et al. 1996; Blednov et al. 2012; Borghese et al. 2012; Celentano et al. 1988; Mariqueo et al. 2014; Mascia et al. 1996; Mihic et al. 1997; Trudell et al. 2014). Thus both pre- and postsynaptic actions of EtOH on inhibition of UBCs may be important in mediating EtOH’s general psychological effects. Here we report that EtOH dose-dependently increases the frequency of UBC GABAergic and glycinergic synaptic currents and also selectively potentiates the magnitude of glycinergic synaptic currents, the latter being due to the impact of EtOH on Golgi cell vesicular release and postsynaptic protein kinase C (PKC) activity. Both effects are significantly larger in low-EtOH-consuming rodent genotypes compared with high-EtOH-consuming rodent genotypes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cerebellar brain slice preparation.

All procedures involving animals were in accordance with the regulations described in the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Washington State University. Male and female SDRs and D2 and B6 mice ranging from 21 to 30 days of age were group housed in a 12:12-h light-dark cycle with ad libitum access to food and water. At the beginning of each experiment each rodent was anesthetized with isoflurane and euthanized by decapitation. Brains were rapidly removed, the cerebellum was dissected away from the brain stem and mounted parallel to the sagittal plane, and parasagittal slices (225 µm thick) of the vermis were cut with a vibrating tissue slicer (Leica VT1200S). All dissections and slice preparation were performed with the tissue immersed in ice-cold (0–2°C) artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing (in mM) 124 NaCl, 26 NaHCO3, 1 NaH2PO4, 2.5 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, and 10 D-glucose and bubbled with 95% O2-5% CO2 (pH 7.4, 300–310 mosM), with the addition of 1 mM kynurenic acid. After slices were prepared, they were maintained at 35–37°C in ACSF with kynurenic acid (1 mM) for 1 h before being brought to room temperature, at which point they were transferred to the recording chamber individually as needed.

Electrophysiology.

All recordings were performed at 32–35°C, and slices were perfused at ~7 ml/min with ACSF (as above, but without added 1 mM kynurenic acid). All recordings were from cerebellar UBCs in lobules IXc and X, visualized with differential interference contrast imaging through an Olympus ×60 (0.9 NA) water-immersion objective. UBCs were identified on the basis of their larger soma size relative to GCs (Fig. 1A). Glass pipettes for whole cell recordings (3–6 MΩ) were filled with internal solution containing (in mM) 130 CsCl, 4 NaCl, 0.5 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, 5 EGTA, 4 MgATP, 0.5 Na2GTP, and 5 QX-314, with pH adjusted to 7.2–7.3 with CsOH [giving a chloride reversal potential (ECl) of ~0 mV]. A dye was also present in the intracellular solution for every recording (1% Lucifer yellow, 1% Dextran 488, or 40 µM Alexa 568), which was imaged at the end of each experiment to confirm characteristic UBC morphology (Fig. 1A). Recordings were rejected from analysis if the holding current was larger than −100 pA or if the access resistance was greater than 25 MΩ or changed by >30%. Voltage-clamp recordings [holding voltage (Vh) = −60 mV] were digitized at 20 kHz and filtered at 10 kHz. Signals were then additionally filtered at 2 kHz for analysis and presentation. In this configuration, all spontaneous phasic synaptic events were inward/downward and blocked by strychnine (1 µM) and/or gabazine (10 µM; Fig. 1B) and were clearly distinguishable from longer-duration glutamatergic events (Rossi et al. 1995), which were not observed to occur spontaneously in the present preparation. EtOH was applied for at least 4–6 min in all cases, and only a single exposure to EtOH was used in analysis. After exposure to EtOH, the slice was discarded and a new slice was used for subsequent experiments.

Fig. 1.

Cerebellar UBCs receive mixed GABAergic and/or glycinergic synaptic inhibition. A, left: DIC image of lobe X within a sagittal cerebellar slice with patch pipette at right recording from a UBC (white arrowhead), which stands out with its larger soma size relative to granule cells (white “>”). Right: 3-dimensional projection of confocally acquired fluorescent image planes (rotated slightly to improve visibility of brush) of the same patched cell from image on left after recording session with Alexa 568 dye present in the pipette. The observed round soma and short brushlike dendrite, typical of UBCs, is the morphological phenotype used to confirm a cell’s identity as a UBC after each recording. B: recordings from 3 different UBCs representing each class of sIPSC (inward/downward deflections) that are only GABAAR mediated [gabazine (GBZ) sensitive; top], only GlyR mediated [strychnine (Strych) sensitive; middle], or GABAAR and GlyR mediated displaying strychnine and GBZ-sensitive components (bottom). C: normalized sIPSC population amplitude histograms for all UBCs recorded in the presence of strychnine (gray, n = 2,209 events from 10 cells from 6 animals) or gabazine (black, n = 1,024 events from 10 cells from 6 animals) are both bimodal, presumably representing quantal and multiquantal events, with large GABAergic events occurring at higher probabilities than large glycinergic events. Raw amplitude distribution from all cells (dotted line) are overlaid with bimodal fit functions (solid lines). D: histogram of total % of glycinergic contribution to the cumulative inhibitory activity (sIPSC frequency × amplitude) for SDR UBCs (n = 49 cells from 18 animals; distribution mean ± SE shown).

For exogenous agonist-evoked GlyR- or GABAAR-mediated currents, all experiments were performed in the presence of TTX (500 nM) to block action potential-dependent increases in vesicle release, d-(−)-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (d-AP5; 50 µM) to block NMDA receptor-mediated currents that might be affected by cofactor glycine, and gabazine (10 µM; for glycinergic events) to block GABAAR responses or strychnine (1 µM, for GABAergic events). To evoke GlyR- or GABAAR-mediated currents, 100 µM glycine or gaboxadol or 4,5,6,7-tetrahydroisoxazolo[5,4-c]pyridin-3-ol hydrochloride (THIP; GABAAR agonist) was added to ACSF that also included TTX, d-AP5, and gabazine or strychnine. The glycine- or THIP-containing solution was backfilled into a pipette (~1-µm tip diameter), which was then placed 5–10 µm from the UBC soma or the brush. Pressure (6 psi, 10 ms) was applied to the back of the pipette via a triggered picospritzer (Pressure System IIe, Toohey) at 20-s intervals. Once the amplitude of the evoked response was stable for at least 3 min, 26 mM EtOH or vehicle (ACSF, 500 nM TTX, 50 µM d-AP5, and 10 µM gabazine or 1 µM strychnine) was bath applied. The average evoked current before, during, and after EtOH/vehicle application was taken as an average of three to six responses. All responses were confirmed to be mediated by GlyRs or GABAARs via their subsequent blockade by bath application of strychnine (2 µM) or gabazine (10 µM), respectively. UBCs recorded in this configuration were chosen based only on the postsynaptic phenotype (response to focally applied agonist) and not biased toward cells with higher miniature (m)IPSC rates to determine EtOH effects on amplitude as in Fig. 5, A–C. Therefore, we further analyzed the frequency and amplitude of these pharmacologically isolated mIPSCs (see Fig. 6) over a 5-min window to determine whether basal properties of glycinergic or GABAergic mIPSCs were comparable. Based on the typical duration of responses to the focally applied exogenous agonist, a period following the onset of either glycine (600 ms) or THIP (5 s) was omitted from analysis of mIPSCs.

Fig. 5.

Selective EtOH-induced postsynaptic increase in UBC GlyR-mediated current amplitude is dependent on postsynaptic protein kinase C activity. A: representative recordings of isolated mIPSCGly (10 µM gabazine, 500 nM TTX) before (black, top) and after (gray, bottom) 26 mM EtOH demonstrate an increase in mIPSCGly amplitude with no change in frequency in SDR cerebellar UBCs. B: cumulative probability histogram of mIPSCGly amplitudes corresponding to the UBC shown in A demonstrates the rightward shift from baseline (black) in the distribution toward larger-amplitude mIPSCGly in the presence of 26 mM EtOH (gray). C: mean ± SE % change in UBC mIPSCGly amplitudes (n = 8 cells from 4 animals) in 26 mM EtOH (EtOH, gray) and in washout (wash, white). D: brief (10 ms) focal application of 100 µM glycine (Gly) (black vertical bar) at 20-s intervals to UBCs evokes stable (left) GlyR-dependent transient inward currents that increase in amplitude in the presence of 26 mM EtOH (center), except when the PKC inhibitor calphostin C (100 nM) is present in the intracellular solution (right). E: focal application of the GABAAR agonist THIP (100 µM) results in stable transient inward currents that are unaltered by bath application of 26 mM EtOH. In D and E, traces are averages of 6 responses (2-min total duration) for each condition normalized to the average baseline peak amplitude. F: mean ± SE pharmacologically evoked GlyR-mediated current amplitudes (each point is an average of 2 responses) were stable near 100% of baseline throughout 5-min vehicle application (n = 5 cells from 3 animals, black circles) but increased gradually over the 5-min exposure to 26 mM EtOH (n = 9 cells from 5 animals, open squares), unless calphostin C was included in the recording pipette (n = 8 cells from 3 animals, gray triangles). GABAR-mediated currents (evoked by THIP) were not affected by application of 26 mM EtOH (n = 6 cells from 3 animals, open diamonds). G and H: plots showing that during EtOH perfusion (G) and after EtOH washout (H) only the magnitude of the evoked GlyR-mediated response was significantly increased by EtOH under control conditions but not when calphostin C was included in the recording pipette. All recordings for D–H were performed in the presence of 500 nM TTX and 50 µM d-AP5, with the addition of 10 µM gabazine to isolate glycinergic responses or 1 µM strychnine to isolate GABAergic responses, and all agonist-evoked responses were subsequently blocked by the addition of 2 µM strychnine or 10 µM gabazine, respectively (not shown). #P < 0.05, *P < 0.01 with 2-tailed paired t-test.

Fig. 6.

UBC mIPSCs are predominantly GABAergic. A and B: representative recordings of UBC mIPSCGlys (A) and mIPSCGABAs (B) in the presence of 500 nM TTX, 50 µM d-AP5, and 10 µM gabazine (0.19 Hz; A) or 1 µM strychnine (0.96 Hz; B), where downward deflections represent mIPSC events. C and D: average (mean ± SE) basal mIPSCGly (n = 14 cells from 5 animals) frequency (C) and amplitude (D) were significantly lower than for average basal mIPSCGABA (n = 7 cells from 3 animals). **P < 0.001 with 2-tailed t-test.

Electrophysiology data analysis and statistics.

All inward/downward GlyR- and GABAAR-mediated spontaneous (s)IPSCs or mIPSCs (strychnine and/or gabazine sensitive) were detected with Mini Analysis (Synaptosoft, Fort Lee, NJ) and were subsequently inspected individually for accuracy. All values for a given cell were determined from all events recorded over 2–4 min immediately before or at least 90 s after a new solution entered the bath. EtOH effects on sIPSC rate and amplitude were only included in analysis if the normalized sIPSC cumulative activity (rate × amplitude, 20-s bins) was stable for the first 2–3 min before EtOH application. Stability was determined by performing a linear fit to the cumulative activity during this time period, the slope of which had to be between 0.5 and −0.5. For consistency in group time course plots, data were normalized to the average value during the 2-min period before EtOH application and aligned on the initiation of EtOH and the initiation of the washout period. Thus values for any time points after 5 min of EtOH exposure are omitted from group time course plots. For clarity in time course analysis only, if values for a given bin (20 s) varied by >1,000% from adjacent bins because of a transient burst, that value was omitted from the time course plot (n = 1 point in 2 cells). To determine the effect of EtOH on total charge movement, the sums of all sIPSC areas (integral of each event) during each analysis period were compared with a paired t-test (Fig. 2G and Fig. 7E). Events that occurred within 50 ms of the previous event, lacked a clear fast rise time with a single peak, and/or lacked a classical exponential decay function were not included in analysis of sIPSC amplitudes and decay kinetics, although all events were included in frequency analyses (Figs. 2, 3, and 4). Decay kinetics of sIPSCs were determined by performing a 10–90% double-exponential fit, the components of which were used to calculated the weighted decay time constant (τw).

Fig. 2.

Recreational concentrations of EtOH dose-dependently enhance sIPSC frequency and amplitude in SDR UBCs. A: representative recording of mixed (not pharmacologically isolated) sIPSCs (downward deflections) in 3 different UBCs shows a dose-dependent increase from baseline in sIPSC frequency and amplitude in response to 10, 26, and 52 mM EtOH. B and C: time course plots (20-s bins) of mean ± SE sIPSC frequency (B) and amplitude (C) expressed as % of baseline before, during, and after bath application (gray shaded region) of 10 (n = 10 cells), 26 (n = 11 cells), and 52 (n = 13 cells) mM EtOH. Insets: expanded time course (40-s bins) and increased gain for 10 mM EtOH with error bars removed for clarity. D–G: mean ± SE % change (normalized to baseline) in sIPSC frequency (D), sIPSC amplitude (E), cumulative sIPSC activity (frequency × amplitude; F), and total charge movement (sum of area for all sIPSCs; G) in response to bath-applied 10 (n = 14 cells from 7 animals), 26 (n = 11 cells from 6 animals), and 52 (n = 13 cells from 7 animals) mM EtOH. H: scatterplot of individual UBC % change in average sIPSC amplitude (y-axis) plotted against % change in frequency (x-axis) in 26 mM EtOH for each cell (n = 10 cells from 6 animals). #P < 0.05, *P < 0.01, **P < 0.00, 2-tailed paired t-test (D–F) or Pearson correlation (H).

Fig. 7.

EtOH-induced enhancement of UBC synaptic inhibition varies across rodent genotypes according to EtOH consumption phenotype. A: representative recordings of mixed (not pharmacologically isolated) sIPSCs before (top) and during (bottom) application of 26 mM EtOH from cerebellar UBCs of a SDR (left), a DBA/2 mouse (D2, middle), and a C57BL/6 mouse (B6, right). B–E: EtOH-induced change in UBC sIPSC frequency (B), amplitude (C), cumulative activity (D), and total charge transfer (E) from SDRs (n = 11 cells from 6 animals) and D2 (n = 11 cells from 5 animals) and B6 (n = 11 cells from 5 animals) mice. #P < 0.05, *P < 0.01, **P < 0.001 with 2-tailed paired t-test for within cell comparisons; §P < 0.05 with SNK method for pairwise comparisons between groups with Kruskal-Wallis 1-way ANOVA on ranks.

Fig. 3.

EtOH-induced changes in SDR UBC sIPSC activity are action potential dependent (TTX sensitive). A: representative recordings of mixed (not pharmacologically isolated) sIPSCs from a cerebellar UBC in standard ACSF (baseline), after 500 nM TTX application to isolate mIPSCs, and after the subsequent addition of 26 mM EtOH followed by washout of EtOH into TTX only. B and C: normalized mean ± SE (bars, left axis) and raw values for individual UBC (gray circles, right axis) IPSC frequency (B) and amplitude (C) for each indicated condition (n = 8 cells from 2 animals). *P < 0.01, 1-way repeated-measures ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc comparing all treatments to the TTX condition. NS, not significant.

Fig. 4.

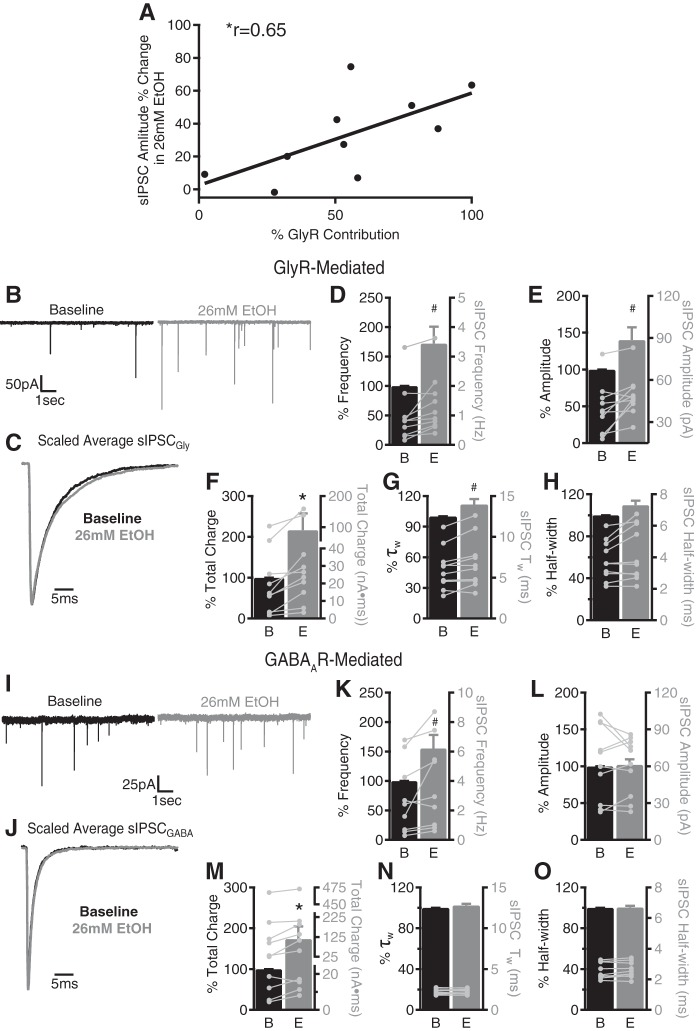

EtOH enhances glycinergic and GABAergic sIPSC frequency and selectively increases glycinergic sIPSC amplitude in SDR UBCs. A: scatterplot of individual UBC % change in average sIPSC amplitude in 26 mM EtOH (y-axis) plotted against % contribution of GlyRs (strychnine sensitive) to the cumulative sIPSC activity (x-axis) for each cell (n = 10 cells from 6 animals). The correlation coefficient (r) for the distribution is shown. B: representative recordings of UBC GlyR-mediated sIPSCs (sIPSCGly) in the presence of 10 µM gabazine before (black, baseline) and during (gray) 26 mM EtOH indicate a significant increase in sIPSCGly frequency (D), amplitude (E), and total charge transfer (F). C: superimposed scaled averages of sIPSCGly traces before (black) and during (gray) 26 mM EtOH indicate a modest increase in weighted decay time constant (τw; G) and half-width (H). I: representative recordings of GABAAR-mediated sIPSCs in the presence of 1 µM strychnine (sIPSCGABA) before (black) and during (gray) 26 mM EtOH indicate a significant increase in sIPSCGABA frequency (K) and total charge transfer (M) with no change in amplitude (L). J: superimposed scaled averages of sIPSCGABA traces before (black) and during (gray) 26 mM EtOH indicate that weighted τw (N) and half-width (O) are not affected. Note the slower decay kinetics of isolated sIPSCGly (C, G, H) relative to sIPSCGABA (J, N, O). For D and E, F–H, K and L, and M–O, bars are means ± SE (left axis) and circles are raw values (right axis), with values from the same UBC in different conditions being connected. For sIPSCGly, n = 10 cells from 6 animals and for sIPSCGABA, n = 10 cells from 6 animals. B, baseline; E, 26 mM EtOH. #P < 0.05, *P < 0.01 with 2-tailed paired t-test, Wilcoxon signed-rank test, or Pearson correlation (A).

For clarity, all values presented in figures are normalized to baseline (immediately before pharmacological manipulation) because of the large cell-to-cell variability in the frequency of baseline synaptic activity. To reduce bias toward larger normalized values (in response to a given drug), as would be the case if initial synaptic activity was low or absent, only cells with baseline sIPSC rates > 0.3 Hz were used for analysis. All amplitude distributions were fit with a double-peak function comprised of a lognormal and Gaussian distribution. All data are given as means ± SE. For all within-cell comparisons a paired two-tailed t-test was used. When more than one comparison was made, a one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test was performed. Nonparametric statistical tests were used when data violated assumptions of normality as signified by a failure of the Shapiro-Wilk test for normality (P ≤ 0.01). In these cases, a Wilcoxon signed-rank test or a Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA on ranks was performed with the Student-Newman-Keuls (SNK) method to evaluate pairwise comparisons (see Fig. 7). Significant correlations were identified with the Pearson correlation coefficient. The threshold for statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. All analysis was performed with Microsoft Excel, IGOR Pro 6, or SigmaPlot 11.

Microscopy.

Widefield fluorescent images of filled UBCs were acquired at the end of each experiment on an upright Olympus microscope coupled to a Lambda DG-4 illumination system (Sutter Instrument) passed through Lucifer yellow, Alexa 488, or Alexa 568 excitation/emission filter sets. Confocal z-stack images of UBCs filled with Alexa 568 dye were acquired on a Leica DM 6000FS microscope with a Yokogawa CSU-X confocal spinning disk and a ×63 (0.9 NA) objective and processed with MetaMorph software.

Reagents.

All reagents used were acquired from Sigma-Aldrich with the exception of gabazine (i.e., SR95531, Abcam), kynurenic acid (Abcam), d-AP5 (Ascent Scientific), TTX (Alamone Labs), strychnine (Abcam), and calphostin C (Tocris Bioscience). Dextran conjugated to Alexa 488 was purchased from Molecular Probes, and Alexa 568 hydrazide dye was from Thermo Fisher Scientific.

RESULTS

EtOH increases dual glycinergic and GABAergic inhibition of SDR UBCs.

In agreement with recent reports (Dugué et al. 2005; Rousseau et al. 2012), synaptic inhibition of SDR UBCs is mediated by both GlyRs and GABAARs (Fig. 1, B–D), as demonstrated by voltage-clamp recordings (Vh = −60 mV, ECl = ~0 mV) of sIPSCs (2.9 ± 0.3 Hz, 55.5 ± 4.1 pA, n = 80 cells from 20 animals) that were consistently blocked by gabazine or strychnine alone or in combination (Fig. 1B). In comparing the amplitude distributions of all pharmacologically isolated GABAergic (62.8 ± 9.6 pA, n = 10 cells) or glycinergic (39.0 ± 5.7 pA, n = 10 cells) sIPSCs, both types of sISPCs appeared to be composed of two discrete populations (Fig. 1C). However, both the difference in magnitude between amplitude populations and the relative proportion of large events were more pronounced for GABAergic than for glycinergic events (Fig. 1C). The proportion of individual UBCs receiving glycinergic, GABAergic, or both types of synaptic inhibition was evenly distributed (Fig. 1D), resulting in the average GlyR contribution to sIPSC activity across all cells being 52.1 ± 4% (n = 49 cells from 18 animals).

To determine the overall impact of EtOH on the frequency and amplitude of sIPSC activity, voltage-clamp recordings of UBC sIPSCs were performed when 10, 26, and 52 mM EtOH was bath applied (Fig. 2). EtOH did not affect (paired t-test, P > 0.05) the holding current or the input resistance of UBCs at 10 mM (basal: −27.5 ± 3.1 pA and 1.46 ± 0.12 GΩ; EtOH: −29.8 ± 3.3 pA and 1.32 ± 0.10 GΩ), 26 mM (basal: −25.6 ± 3.0 pA and 1.10 ± 0.09 GΩ; EtOH: −25.3 ± 3.3 pA and 1.23 ± 0.09 GΩ), or 52 mM (basal: −36.4 ± 6.5 pA and 1.12 ± 0.14 GΩ; EtOH: −37.7 ± 6.3 pA and 1.19 ± 0.16 GΩ) EtOH. Similar to EtOH-induced effects on SDR GC synaptic inhibition (Kaplan et al. 2013), all three concentrations significantly increased the frequency of sIPSCs in UBCs in a concentration-dependent manner [10 mM = 15.2 ± 5.3% (P = 0.009, n = 14 cells from 7 animals), 26 mM = 57.7 ± 14.9% (P = 0.002, n = 11 cells from 6 animals), 52 mM = 224.9 ± 63.0% (P = 0.0007, n = 13 cells from 7 animals); Fig. 2, A, B, and D], which recovered upon washout (Fig. 2B). At the higher EtOH concentrations (26 and 52 mM), the average amplitude of sIPSCs also significantly increased [10 mM = 4.7 ± 2.4% (P = 0.3), 26 mM = 31.6 ± 7.3% (P = 0.03), 52 mM = 42.5 ± 16.5% (P = 0.03); Fig. 2, A, C, and E]. The EtOH-induced enhancement of cumulative sIPSC activity (mean frequency × mean amplitude; Fig. 2F) and total charge movement (sum of areas for all sIPSCs; Fig. 2G) on SDR UBCs was significant at 10 mM [activity: 21.2 ± 7.2% (P = 0.03); charge movement: 25.9 ± 0.1% (P = 0.0007)], 26 mM [activity: 115.1 ± 30.4% (P = 0.007); charge movement: 135.5 ± 36.0% (P = 0.007)] and 52 mM [activity: 340.6 ± 85.2% (P = 0.001); charge movement: 444.1 ± 110.2% (P = 0.002)] EtOH. Notably, the degree of EtOH potentiation of sIPSC amplitude was significantly correlated with the degree of EtOH potentiation of sIPSC frequency (r = 0.85, n = 10 cells from 6 animals, P = 0.006; Fig. 2H), suggesting that at least part of the increase in amplitude may be due to EtOH increasing Golgi cell firing with a resultant shift from quantal to multiquantal vesicular release.

Golgi cell multivesicular release and EtOH-induced changes in UBC sIPSC frequency are action potential dependent.

Previous work determined that Golgi cells are the source of both glycinergic and GABAergic inhibition of UBCs (Dugué et al. 2005; Rousseau et al. 2012), and it has been shown that EtOH-induced enhancement of cerebellar GC tonic GABAAR current is due to an increase in Golgi cell firing rate (Botta et al. 2010; Kaplan et al. 2013). Thus we predicted that EtOH-induced enhancement of synaptic inhibition of UBCs would also be dependent on increased Golgi cell action potential firing. In SDR UBC recordings, blocking action potentials with TTX (500 nM) significantly reduced IPSC frequency and amplitude and prevented EtOH-induced changes [Fig. 3; main effect of TTX on sIPSC frequency (F3,7 = 5.48, P = 0.006) and amplitude (F3,7 = 11.16, P < 0.001)]. Basal IPSC frequency (4.1 ± 1.0 Hz) was significantly reduced by TTX (1.27 ± 0.3 Hz, an average reduction of 47.6 ± 14.1%; P = 0.007, n = 8 cells from 2 animals), as was the sIPSC amplitude (basal: 62.3 ± 12.8 pA, TTX: 24.3 ± 2.4 pA, an average reduction of 51.8 ± 8.1%; P < 0.001), which is compatible with Golgi cell action potential-dependent synaptic currents being multiquantal. In the presence of TTX, the subsequent application of 26 mM EtOH (Fig. 3A) did not significantly affect mIPSC frequency (P = 1.0) or amplitude (P = 1.0), confirming that the EtOH-induced increase in both IPSC frequency and amplitude is due to increased firing of Golgi cell action potentials. Importantly, the lack of EtOH enhancement of mIPSC amplitude suggests that at least some of the EtOH-induced increase in sIPSC amplitude (Fig. 2) is due to an increase in the ratio of action potential-evoked multiquantal IPSCs to spontaneous miniature quantal IPSCs, consequent to EtOH-induced increased Golgi cell firing (although see below for additional postsynaptic effects).

EtOH selectively increases glycinergic sIPSC amplitude in SDR UBCs.

In our initial studies of EtOH impacts on mixed GABAAR/GlyR synaptic currents (Fig. 2), we found that individual cells showing more pronounced EtOH enhancement of sIPSC amplitude tended to be cells with a greater proportion of GlyR IPSCs (as determined by subsequent pharmacological assessment, as in Fig. 1). Indeed, there was a significant positive correlation between the EtOH-induced change in sIPSC amplitude and the dependence of sIPSCs on GlyRs (r = 0.65, P = 0.04) (Fig. 4A). This correlation suggests that EtOH-induced enhancement of UBC sIPSC amplitude may be mediated by actions on GlyR sIPSCs selectively. Therefore, we next determined the impact of EtOH on pharmacologically isolated GABAergic (sIPSCGABA recorded in strychnine) and glycinergic (sIPSCGly recorded in gabazine) sIPSCs (Fig. 4). In the presence of gabazine, 26 mM EtOH increased the frequency (72.0 ± 28.4%, P = 0.01, n = 10 from 6 animals), amplitude (40.3 ± 17.2%, P = 0.02), and total charge transfer (116.7 ± 40.5%, P = 0.002) of sIPSCGly (Fig. 4, B, D, E, and F). EtOH (26 mM) also produced a modest but significant slowing of τw (11.7 ± 5.2%, P = 0.02; Fig. 4, C and G). In contrast to the effects of EtOH on sIPSCGly, only the frequency (55.3 ± 23.1%, P = 0.03, n = 10 from 6 animals) and total charge transfer (73.7 ± 31.0%, P = 0.004) of sIPSCGABA were increased by 26 mM EtOH (Fig. 4, I, K, and M). The amplitude (2.1 ± 7.6%; P = 0.6; Fig. 4, I and L) and decay kinetics (2.5 ± 1.6%, P = 0.1; Fig. 4, J and N) of sIPSCGABA were not affected by 26 mM EtOH. Together, these data indicate that actions of EtOH on sIPSCGABA are mediated exclusively by increased frequency of vesicular release from Golgi cells, whereas the increase in sIPSCGly amplitude suggests that EtOH also increases either postsynaptic responsivity or the number of synchronously released quanta sensed by glycinergic synapses or both.

EtOH increases GlyR-mediated current amplitude by a postsynaptic protein kinase C-dependent mechanism.

The lack of effect of EtOH on mixed mIPSC amplitude (Fig. 3) suggests that EtOH enhancement of sIPSCGly (Fig. 4E) is mediated by increased multiquantal release or activation of previously inactive Golgi cells with larger quantal size synapses. However, because previous studies have shown that EtOH can directly enhance GlyRs (Aguayo and Pancetti 1994; Mariqueo et al. 2014; Mascia et al. 1998; Ye et al. 2002), and EtOH selectively increases sIPSCGly amplitude (Fig. 4, B and E) but not sIPSCGABA amplitude (Fig. 4, I and L), we decided to examine pharmacologically isolated GlyRs to avoid potential obfuscation of EtOH actions on postsynaptic GlyRs by lack of EtOH action on GABAARs in our mixed recordings (Figs. 2 and 3). Furthermore, to isolate postsynaptic actions from enhancement mediated by increased occurrence of action potential-dependent release events (Fig. 3), we used TTX to prevent action potentials and investigated the effect of 26 mM EtOH on quantal mIPSCGly (Fig. 5, A–C). In the presence of TTX 26 mM EtOH did not affect the frequency of pharmacologically isolated mIPSCGly (24.5 ± 24.5%, P = 0.9), but it did significantly increase their amplitude (9.0 ± 3.9%, P = 0.04, n = 8 cells from 4 animals; Fig. 5, A–C), causing a rightward shift in the amplitude cumulative histogram (Fig. 5B). Such potentiation persisted for at least 2–3 min after washout of EtOH (Fig. 5C).

To confirm postsynaptic actions of EtOH, GlyR currents were elicited by focal application of subsaturating concentrations of exogenous glycine (100 µM, 10-ms duration) in order to remove any influence of EtOH-induced changes in presynaptic release. Repeated-measures ANOVA indicated that only EtOH (F8,2 = 10.65, P = 0.001), but not vehicle (F4,2 = 0.79, P = 0.49), had a significant effect on eIPSCGly amplitudes (Fig. 5, D, F, and G). Glycine-evoked IPSCGly (eIPSCGly) had stable amplitudes in vehicle (1.3 ± 1.9%, n = 5 cells from 3 animals; Fig. 5, D–G), but when 26 mM EtOH was applied in the bath the eIPSCGly amplitudes steadily increased over time (Fig. 5, D and F–H) and were significantly increased compared with pre-EtOH amplitudes (24.1 ± 7.3%, P = 0.043, n = 9 cells from 5 animals; Fig. 5G). Similar to the effects of EtOH on mIPSCGly amplitudes after washout (Fig. 5C), exogenous glycine-evoked IPSC amplitudes continued to increase during EtOH washout (41.4 ± 15.6%, P < 0.001, n = 8 cells from 3 animals; Fig. 5H). No such increase occurred in vehicle (6.9 ± 5.6%, n = 4 cells from 3 animals; Fig. 5H). Previous work suggests that EtOH modulation of GlyR currents is dependent on postsynaptic PKC activity (Mascia et al. 1998; Ye et al. 2002), so as a final test of postsynaptic actions of EtOH on UBC GlyRs, we determined whether EtOH potentiation of GlyR-mediated current amplitude was dependent on postsynaptic PKC activity. To specifically inhibit PKC activity only in the UBC being recorded, the PKC inhibitor calphostin C (100 nM) was included in the patch pipette for at least 5 min before and throughout the focal glycine application protocol. Such application of calphostin C in the recorded UBC blocked the ability of 26 mM EtOH to increase the eIPSCGly amplitude (F7,2 = 1.00, P = 0.39) either in EtOH (−3.3 ± 7.2%,, n = 8 cells from 3 animals; Fig. 5, D, F, and G) or after EtOH washout (−9.4 ± 5.6%, n = 7 cells from 3 animals; Fig. 5H).

In contrast to the GlyR response, when GABAergic responses were isolated (500 nM TTX, 50 µM d-AP5, and 1 µM strychnine), the response of UBCs to the GABAAR agonist THIP (100 µM) was not significantly altered by bath application of 26 mM EtOH (0.3 ± 4.5%, F5,2 = 0.92, P = 0.43, n = 6 cells from 3 animals; Fig. 5, E–G) or in washout of EtOH (3.4 ± 3.3%; Fig. 5H). Together, these data indicate that EtOH selectively enhances postsynaptic GlyR responsivity in a PKC-dependent manner, an effect that may persist long after EtOH is removed.

However, this selective postsynaptic sensitivity of GlyR responses to EtOH was not reflected in the recording of mixed-phenotype mIPSCs, which did not exhibit an EtOH-induced increase in amplitude (Fig. 3C). Therefore, we further analyzed the basal frequency and amplitude of pharmacologically isolated mIPSCs recorded during these experiments to determine whether there may be differences in quantal release characteristics of these two transmitter systems. The mean mIPSCGly frequency (0.16 ± 0.04 Hz, n = 14 cells from 5 animals) and amplitude (20.9 ± 1.2 pA) were significantly lower than for mIPSCGABA [0.89 ± 0.21 Hz, (P = 0.0002), 32.8 ± 1.6 pA (P = 0.00001), n = 7 cells from 3 animals; Fig. 6). Therefore, the quantal release properties of mIPSCGABA and mIPSCGly appear notably different, with the probability of vesicle release (Pr) being significantly lower for glycinergic than for GABAergic synapses. Accordingly, the inability of EtOH to alter mixed mIPSC current amplitude (Fig. 3), despite clear EtOH-induced enhancement of postsynaptic GlyR responses (Fig. 4 and Fig. 5), likely stems from a combination of the limited contribution of GlyRs to the mIPSC activity in UBCs (Fig. 6) and a lack of EtOH-induced enhancement of postsynaptic GABAergic responses (Fig. 4L and Fig. 5, E–G), which dominate UBC mIPSC activity (Fig. 6).

EtOH-induced change in UBC sIPSC activity varies across rodent genotype in relation to alcohol consumption phenotype.

Since the EtOH sensitivity of the Golgi cell-GC synapse has been shown to vary across rodent genotypes in parallel with EtOH consumption phenotype, and UBCs are also innervated by Golgi cells, we determined whether EtOH actions on Golgi cell-to-UBC transmission also varied across rodent genotypes with divergent EtOH consumption/sensitivity phenotypes (Fig. 7). Similar to SDR UBCs, D2 and B6 mouse UBCs exhibited sIPSCs [baseline sIPSCs: D2 mouse, 4.3 ± 1.4 Hz, 20.9 ± 1.3 pA (n = 12 cells from 5 animals) and B6 mouse, 3.5 ± 0.6 Hz, 29.4 ± 2.1 pA (n = 11 cells from 5 animals); Fig. 7A], but the EtOH sensitivity of UBC synaptic inhibition varied significantly between rodent genotypes in regard to frequency (H2 = 6.85, P = 0.03), amplitude (H2 = 12.515, P = 0.002), cumulative activity (H2 = 8.222, P = 0.02), and total charge transfer (H2 = 11.121, P = 0.004). In D2 mice, which have a EtOH consumption phenotype similar to SDRs (Duncan and Deitrich 1980; Yoneyama et al. 2008), EtOH (26 mM) increased the sIPSC frequency (37.0 ± 6.6%, P = 0.0001, n = 11 cells from 5 animals) similar to SDR UBCs (P > 0.05, SNK method; Fig. 7, A and B), but it did not enhance sIPSC amplitude (2.0 ± 1.3%, P = 0.3; Fig. 7, A and C) relative to SDR UBCs (P > 0.05, SNK). In contrast, 26 mM EtOH did not significantly increase the frequency (13.1 ± 4.6%, P = 0.06, n = 11 cells from 6 animals) or the amplitude (4.7 ± 2.1%, P = 0.1) of B6 mouse UBC sIPSCs, both significantly different from the enhancement induced by EtOH in SDR UBCs (frequency: P < 0.05, amplitude: P < 0.05, SNK; Fig. 7, A and B). Importantly, even the trend for an EtOH-induced increase in UBC sIPSC frequency in B6 mice was also significantly smaller than the impact on D2 mouse sIPSC frequency (P < 0.05, SNK), which offset the similarly negligible impact of EtOH on sIPSC amplitude between the two species (P > 0.05, SNK). This resulted in the net impact of EtOH on cumulative sIPSC activity (Fig. 7D) and total charge transfer (Fig. 7E) being smaller in high-EtOH-consuming, low-sensitivity B6 mice (activity: 18.8 ± 6.5%, P = 0.08; charge transfer: 12.7 ± 8.7%, P = 0.06) compared with low-EtOH-consuming, high-sensitivity SDRs (B6 vs. SDR: P < 0.05, SNK) and D2 mice (activity: 39.7 ± 7.1%, P = 0.00006; charge transfer: 50.9 ± 6.4%, P = 0.00003, B6 vs. D2: P < 0.05 for activity and charge transfer, SNK), resulting in significant differences between EtOH effects on cumulative sIPSC activity (P > 0.05, SNK) but not total charge transfer between D2 and SDR UBCs (P > 0.05, SNK). Together, these data demonstrate that, similar to EtOH actions on GCs (Kaplan et al. 2013), the net effect of EtOH on UBC sIPSCs is graded in magnitude, being highest in SDR UBCs and smallest in B6 mouse UBCs, with intermediate impact on D2 mouse UBCs.

DISCUSSION

These data demonstrate that recreational concentrations of EtOH (starting at 10 mM, equivalent to 1–2 standard units consumed by a typical adult human male in 1–2 h) significantly enhance synaptic inhibition of cerebellar UBCs (Fig. 2). The enhancement by EtOH is mediated by two factors: 1) increased action potential-dependent vesicular release of GABA and glycine from Golgi cells onto UBCs, manifesting as increased frequency of sIPSCGABA and sIPSCGly (Fig. 3 and Fig. 4), and 2) larger-amplitude GlyR-mediated responses due to increased number of multiquantal events (Fig. 3 and Fig. 4) and PKC-dependent enhancement of postsynaptic GlyRs (Fig. 5). Thus UBC synaptic inhibition is likely an additional mechanism mediating the cerebellum’s exquisite sensitivity to EtOH. Importantly, the magnitudes of both presynaptic and postsynaptic responses to EtOH vary across rodent genotypes with divergent EtOH-related phenotypes (Fig. 7), with both responses being larger in low-EtOH-consuming SDRs (Duncan and Deitrich 1980) than in high-EtOH-consuming B6 mice (Yoneyama et al. 2008). Similar to what we reported for EtOH impacts on GC inhibition (Kaplan et al. 2013), the response of UBCs from low-EtOH-consuming D2 mice had similarities to both SDRs (significant increase in sIPSC frequency) and B6 mice (minimal potentiation of sIPSC amplitude), but the net impact of EtOH on D2 UBC inhibition (i.e., cumulative activity and total charge transfer) is significantly larger than the net impact on B6 UBCs (Fig. 7, D and E). Thus UBCs from SDRs and D2 mice, which are both sensitive to EtOH-induced motor impairment and are low EtOH consumers (Duncan and Deitrich 1980; Gallaher et al. 1996; Hanchar et al. 2005; Yoneyama et al. 2008), were significantly more disrupted than UBCs from B6 mice, which are relatively insensitive to EtOH-induced motor impairment and are high EtOH consumers (Gallaher et al. 1996; Yoneyama et al. 2008). Accordingly, variation in UBC sensitivity to EtOH may contribute to the heritable relationship between low sensitivity to EtOH-induced motor impairment and risk for AUD in humans and excessive EtOH consumption in rodents (Gallaher et al. 1996; Schuckit 1985, 1994; Yoneyama et al. 2008).

EtOH actions on presynaptic Golgi cells.

EtOH increases SDR UBC sIPSC frequency via an action potential-dependent mechanism (Fig. 2 and Fig. 3). This result is compatible with previous studies of Golgi cell-to-GC synaptic transmission that determined that EtOH increases Golgi cell action potential firing, which in turn drives EtOH-induced increased GC sIPSC frequency and tonic GABAAR current magnitude, both largely blocked by TTX (Botta et al. 2007a; Carta et al. 2004; Hanchar et al. 2005; Kaplan et al. 2013). Given that UBCs and GCs are innervated by presynaptic Golgi cells (Dugué et al. 2005), the similar sensitivity to TTX of EtOH-induced increases in UBC sIPSCs implicates EtOH excitation of Golgi cells as the cause of increased UBC sIPSC frequency. Importantly, evidence suggests that Golgi cells may release both GABA and glycine but that other subsets of Golgi cells may only be glycinergic or GABAergic (Dugué et al. 2005, 2009; Rousseau et al. 2012; Simat et al. 2007). In support of the latter, the present data suggest that mechanisms of GABA and glycine release at UBC synapses may be functionally distinct from one another. First, the frequency of quantal GABAergic mIPSCs is nearly fivefold higher than that for glycinergic mIPSCs (Fig. 6), suggesting that the mechanisms regulating the Pr of each transmitter may be different, possibly because of being released from separate synapses and/or subtypes of Golgi cells. The possibility of functionally distinct synapses and/or subtypes of Golgi cells providing synaptic inhibition of UBCs is further supported by differences between the glycinergic and GABAergic distributions of small-amplitude and large-amplitude events (Fig. 1C), presumed to be single-quantal and multiquantal, respectively. Furthermore, EtOH increased the amplitude of glycinergic events, but not GABAergic events (Fig. 4). As a result, EtOH-induced enhancement of Golgi cell firing has a larger impact at glycinergic Golgi-UBC synapses (Fig. 4, F and M), which have been shown to be associated with mGluR2-expressing UBCs (Rousseau et al. 2012). Therefore, EtOH actions on UBCs may disproportionately disrupt transmission associated with mGluR2-expressing “off” rather than “on” responding UBCs (Borges-Merjane and Trussell 2015; Zampini et al. 2016).

We previously determined that EtOH excitation of Golgi cells is mediated by inhibition of neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) and that genetic variation of cerebellar nNOS expression resulted in genetic differences in EtOH-induced enhancement of GC GABAAR inhibition (Kaplan et al. 2013). Specifically, compared with EtOH actions on B6 mouse GCs, EtOH increases GC GABAAR inhibition to a greater degree in SDRs and D2 mice, which both have significantly greater nNOS expression levels than B6 mice (Kaplan et al. 2013). Thus elevated cerebellar nNOS expression, and resultant increased EtOH excitation of Golgi cells, likely also explains the larger EtOH-induced increase in UBC sIPSCs in SDR and D2 mice compared with B6 mice (Fig. 7, A and B). The mechanisms by which inhibition of nNOS excites Golgi cells are currently not known but could be mediated by actions of nitric oxide on Golgi cell Na+-K+-ATPase or K+ channels, both of which have also been implicated in EtOH excitation of Golgi cells (Botta et al. 2010, 2012).

EtOH enhancement of postsynaptic GlyRs.

In addition to the EtOH-induced change in sIPSC frequency (Fig. 2), EtOH selectively potentiated GlyR-mediated currents but not GABAAR-mediated currents in SDR UBCs (Fig. 4 and Fig. 5). Since this increase in sIPSC amplitude observed in mixed GlyR/GABAAR responses (Fig. 2, C and E) is correlated with increased sIPSC frequency and is blocked by TTX, the EtOH effect on sIPSC amplitude appears to be due, in part, to an increase in the recruitment of previously quiescent synapses with larger quantal response or an increase in the number of multiquantal sIPSCs (Fig. 3 and Fig. 4). However, EtOH-induced selective enhancement of postsynaptic GlyR receptors also contributes to the increase in sIPSCGly amplitude (Fig. 5). Relevant to this observation, mutations in GlyR subunits or GlyR-specific pharmacological modulation significantly alter behavioral responses and consumption preference for EtOH (Aguayo et al. 2014; Blednov et al. 2012, 2015; Findlay et al. 2002; McCracken et al. 2013; Quinlan et al. 2002; Ye et al. 2009;), but the role of GlyRs in AUDs has been difficult to determine because of the limited evidence for functional GlyRs in mature higher-order brain regions typically associated with reward and addiction (Aroeira et al. 2011; Avila et al. 2013; Chattipakorn and McMahon 2002; Maguire et al. 2014). Thus our finding of both pre- and postsynaptic enhancement of UBC GlyR by EtOH highlights UBCs as potential mediators of GlyR-related EtOH phenotypes (Howard et al. 2014; Trudell et al. 2014). It is important to note that these pre- and postsynaptic mechanisms for enhancing IPSCGly amplitudes may be synergistic in an intact system since modulatory effects of EtOH on ligand-gated receptors seem to be greater with increasing ligand concentrations (Aguayo and Pancetti 1994). In particular, although the significant EtOH enhancement of uniquantal mIPSCGly amplitudes (~10%, Fig. 5) is smaller than the enhancement of action potential-dependent, presumed multiquantal sIPSCGly amplitude (~60%, Fig. 3), since glycine concentrations are likely to be higher during multiquantal release events, postsynaptic enhancement of sIPSCGly may be greater than for mIPSCGly, as is seen with the ~25% increase in exogenous glycine-evoked eIPSCGly amplitude (Fig. 5G). Finally, our finding that blocking postsynaptic PKC activity prevents EtOH enhancement of postsynaptic GlyRs (Fig. 5) adds further support to previous studies showing the importance of PKC in gating actions of EtOH on both GABAARs and GlyRs (Choi et al. 2008; Hodge et al. 1999; Kaplan et al. 2013; Mascia et al. 1998; Trudell et al. 2014; Ye et al. 2002) and its potential as a genetic variant related to risk for AUD (Schuckit et al. 2004).

How might differences in cerebellar sensitivity to EtOH influence EtOH consumption?

The cerebellum was traditionally considered solely a locus for motor coordination, and it is clear that the cerebellum is a primary mediator of EtOH-induced disruption of motor coordination (Dar 2011, 2015; Hanchar et al. 2005). However, a growing body of research suggests a role for the cerebellum in AUD (Herting et al. 2011; Hill et al. 2007; Kaplan et al. 2013, 2016b; Miquel et al. 2009; Mohr et al. 2013; Olbrich et al. 2006; Schneider et al. 2001), and given the growing appreciation of cerebellar involvement in cognitive/emotional/reward processes (D’Angelo and Casali 2013; Kelly and Strick 2003; Levisohn et al. 2000; Schmahmann 2004; Tavano et al. 2007), the cerebellum would seem ideally situated to mediate the genetic relationship between insensitivity to EtOH-induced motor impairment and risk for AUD in humans and excessive EtOH consumption in preclinical animal models (Gallaher et al. 1996; Kaplan et al. 2013, 2016b; Schuckit 1985, 1994; Yoneyama et al. 2008). How then might genetic variation in GC and UBC responses to EtOH contribute to this relationship? Arguably, EtOH effects in the cerebellum may modulate EtOH consumption simply through its alteration of vestibulomotor performance (e.g., ataxia, nystagmus). In this context, the UBC-containing vestibulocerebellar lobes (IX and X) (Arenz et al. 2008; Barmack and Yakhnitsa 2008) and UBCs in particular (Barmack and Yakhnitsa 2008; Hensbroek et al. 2015) maintain balance and are finely tuned to head orientation. Thus forms of vestibulocerebellar dysfunction in humans often lead to intense and unpleasant ataxia, vertigo/dizziness, and nystagmus (Damji et al. 1996; Hotson 1984; Ragge et al. 2003). Therefore, EtOH disruption of vestibulomotor performance stemming from decreased transmission through cerebellar cortex and disruption of temporal firing properties of GCs and specifically UBCs may cause discomfort or dizziness, thus generating a deterrent for EtOH consumption in genotypes with high GC and UBC sensitivity to EtOH, such as SDRs and D2 mice. Under this scenario, genotypes with reduced GC and UBC sensitivity to EtOH (i.e., B6 mice) would not experience such deterrent, which would enable increased EtOH consumption driven by rewarding actions elsewhere in the brain (Koob et al. 1998; Koob and Volkow 2010; Tabakoff and Hoffman 2013).

However, the cerebellum also communicates with brain regions specifically associated with EtOH reward, including the ventral tegmental area (VTA) (Ikai et al. 1992, 1994; Mittleman et al. 2008; Rogers et al. 2011, 2013), amygdala (Tomasi and Volkow 2011), and nucleus accumbens (Dempsey and Richardson 1987). Connections to the VTA are particularly intriguing because electrical stimulation of Purkinje cells (the sole output of the cerebellar cortex) significantly increases dopamine release in the prefrontal cortex, with ~50% of the release being from the VTA (Mittleman et al. 2008; Rogers et al. 2011, 2013). Thus selective inhibition of excitatory inputs to Purkinje cells (i.e., GCs and UBCs) by low ethanol concentrations (10 mM), which is below threshold for directly affecting VTA neurons (Brodie and Appel 2000; Okamoto et al. 2006), could impact VTA dopamine release and contribute to a cerebellum-dependent, selective suppression of VTA dopamine release in genotypes with high GC and UBC sensitivity to EtOH. Since decreased VTA dopamine release is broadly associated with reduced ethanol consumption (El-Ghundi et al. 1998; Ikemoto et al. 1997; Morikawa and Morrisett 2010; Risinger et al. 2000), the proposed cerebellum-dependent selective suppression of VTA dopamine release could contribute to the low ethanol consumption phenotype in genotypes with high GC and UBC sensitivity to EtOH. In fact, we recently reported that pharmacologically inhibiting GCs reduces EtOH consumption in otherwise high-EtOH-consuming B6 mice (Kaplan et al. 2016b).

Finally, Purkinje cells of lobe X from the UBC-containing vestibulocerebellum provide polysynaptic input to Brodmann area 46 in macaque (Kelly and Strick 2003), part of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex—a cortical structure regulating self-control and delayed choice (Figner et al. 2010; Hare et al. 2009; Hayashi et al. 2013) and implicated in development of substance use disorders (Goldstein and Volkow 2011). This connection is potentially important for several reasons: 1) functional connectivity between the cerebellum and prefrontal cortex is reduced in humans with a family history of alcoholism (FH+), 2) FH+ youths show reduced fronto-cerebellar brain activation during a risk taking task, and 3) binge drinking in adolescents results in reduced cerebellar activation during a reward processing task (Herting et al. 2011; Cservenka and Nagel 2012; Cservenka 2016). Collectively, these results suggest that either genetic (FH+) or environmental (binge drinking) risk factors for developing AUD are associated with altered fronto-cerebellar processing and associated behaviors. Thus genetic differences in GC and UBC sensitivity to EtOH, which should result in differential disruption of communication between the cerebellum and VTA or prefrontal cortex during recreational and binge drinking, may be another factor that contributes to the development of AUD.

In summary, recreational/clinically relevant concentrations of EtOH (10–50 mM) powerfully enhance synaptic inhibition of cerebellar UBCs via increased vesicular release of GABA and glycine and a concomitant enhancement of postsynaptic GlyRs, the latter effect dependent on postsynaptic PKC activity. Such effects varied across rodent genotypes, with stronger net impact occurring in low-EtOH-consuming genotypes, SDR and D2 mice, compared with high-EtOH-consuming B6 mice. These data highlight cerebellar UBCs as targets of low concentrations of EtOH that may contribute to the genetic relationship between EtOH-induced motor impairment and EtOH consumption.

GRANTS

This study was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant R01 AA-012439 and Washington State University startup funds awarded to D. J. Rossi and a postdoctoral grant from the Washington State University Alcohol and Drug Abuse Research Program (ADARP) awarded to B. D. Richardson. This investigation was supported in part by funds provided for medical and biological research by State of Washington Initiative Measure No. 171. Experiments were performed at Washington State University.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

B.D.R. and D.J.R. conceived and designed research; B.D.R. performed experiments; B.D.R. and D.J.R. analyzed data; B.D.R. and D.J.R. interpreted results of experiments; B.D.R. and D.J.R. prepared figures; B.D.R. and D.J.R. drafted manuscript; B.D.R. and D.J.R. edited and revised manuscript; B.D.R. and D.J.R. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Agrawal A, Lynskey MT. Are there genetic influences on addiction: evidence from family, adoption and twin studies. Addiction 103: 1069–1081, 2008. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguayo LG, Castro P, Mariqueo T, Muñoz B, Xiong W, Zhang L, Lovinger DM, Homanics GE. Altered sedative effects of ethanol in mice with α1 glycine receptor subunits that are insensitive to Gβγ modulation. Neuropsychopharmacology 39: 2538–2548, 2014. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguayo LG, Pancetti FC. Ethanol modulation of the gamma-aminobutyric acidA- and glycine-activated Cl− current in cultured mouse neurons. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 270: 61–69, 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguayo LG, Tapia JC, Pancetti FC. Potentiation of the glycine-activated Cl− current by ethanol in cultured mouse spinal neurons. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 279: 1116–1122, 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arenz A, Silver RA, Schaefer AT, Margrie TW. The contribution of single synapses to sensory representation in vivo. Science 321: 977–980, 2008. doi: 10.1126/science.1158391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aroeira RI, Ribeiro JA, Sebastião AM, Valente CA. Age-related changes of glycine receptor at the rat hippocampus: from the embryo to the adult. J Neurochem 118: 339–353, 2011. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avila A, Nguyen L, Rigo JM. Glycine receptors and brain development. Front Cell Neurosci 7: 184, 2013. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barmack NH, Yakhnitsa V. Functions of interneurons in mouse cerebellum. J Neurosci 28: 1140–1152, 2008. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3942-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell RL, Stewart RB, Woods JE 2nd, Lumeng L, Li TK, Murphy JM, McBride WJ. Responsivity and development of tolerance to the motor impairing effects of moderate doses of ethanol in alcohol-preferring (P) and -nonpreferring (NP) rat lines. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 25: 644–650, 2001. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2001.tb02262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belmeguenai A, Botta P, Weber JT, Carta M, De Ruiter M, De Zeeuw CI, Valenzuela CF, Hansel C. Alcohol impairs long-term depression at the cerebellar parallel fiber-Purkinje cell synapse. J Neurophysiol 100: 3167–3174, 2008. doi: 10.1152/jn.90384.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blednov YA, Benavidez JM, Black M, Leiter CR, Osterndorff-Kahanek E, Harris RA. Glycine receptors containing α2 or α3 subunits regulate specific ethanol-mediated behaviors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 353: 181–191, 2015. doi: 10.1124/jpet.114.221895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blednov YA, Benavidez JM, Homanics GE, Harris RA. Behavioral characterization of knockin mice with mutations M287L and Q266I in the glycine receptor α1 subunit. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 340: 317–329, 2012. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.185124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges-Merjane C, Trussell LO. ON and OFF unipolar brush cells transform multisensory inputs to the auditory system. Neuron 85: 1029–1042, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borghese CM, Blednov YA, Quan Y, Iyer SV, Xiong W, Mihic SJ, Zhang L, Lovinger DM, Trudell JR, Homanics GE, Harris RA. Characterization of two mutations, M287L and Q266I, in the α1 glycine receptor subunit that modify sensitivity to alcohols. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 340: 304–316, 2012. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.185116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botta P, de Souza FM, Sangrey T, De Schutter E, Valenzuela CF. Alcohol excites cerebellar Golgi cells by inhibiting the Na+/K+ ATPase. Neuropsychopharmacology 35: 1984–1996, 2010. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botta P, Mameli M, Floyd KL, Radcliffe RA, Valenzuela CF. Ethanol sensitivity of GABAergic currents in cerebellar granule neurons is not increased by a single amino acid change (R100Q) in the alpha6 GABAA receptor subunit. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 323: 684–691, 2007a. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.127894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botta P, Radcliffe RA, Carta M, Mameli M, Daly E, Floyd KL, Deitrich RA, Valenzuela CF. Modulation of GABAA receptors in cerebellar granule neurons by ethanol: a review of genetic and electrophysiological studies. Alcohol 41: 187–199, 2007b. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botta P, Simões de Souza FM, Sangrey T, De Schutter E, Valenzuela CF. Excitation of rat cerebellar Golgi cells by ethanol: further characterization of the mechanism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 36: 616–624, 2012. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01658.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodie MS, Appel SB. Dopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area of C57BL/6J and DBA/2J mice differ in sensitivity to ethanol excitation. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 24: 1120–1124, 2000. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2000.tb04658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carta M, Mameli M, Valenzuela CF. Alcohol enhances GABAergic transmission to cerebellar granule cells via an increase in Golgi cell excitability. J Neurosci 24: 3746–3751, 2004. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0067-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celentano JJ, Gibbs TT, Farb DH. Ethanol potentiates GABA- and glycine-induced chloride currents in chick spinal cord neurons. Brain Res 455: 377–380, 1988. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattipakorn SC, McMahon LL. Pharmacological characterization of glycine-gated chloride currents recorded in rat hippocampal slices. J Neurophysiol 87: 1515–1525, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi DS, Wei W, Deitchman JK, Kharazia VN, Lesscher HM, McMahon T, Wang D, Qi ZH, Sieghart W, Zhang C, Shokat KM, Mody I, Messing RO. Protein kinase Cdelta regulates ethanol intoxication and enhancement of GABA-stimulated tonic current. J Neurosci 28: 11890–11899, 2008. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3156-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cservenka A. Neurobiological phenotypes associated with a family history of alcoholism. Drug Alcohol Depend 158: 8–21, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cservenka A, Nagel BJ. Risky decision-making: an FMRI study of youth at high risk for alcoholism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 36: 604–615, 2012. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01650.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Angelo E, Casali S. Seeking a unified framework for cerebellar function and dysfunction: from circuit operations to cognition. Front Neural Circuits 6: 116, 2013. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2012.00116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damji KF, Allingham RR, Pollock SC, Small K, Lewis KE, Stajich JM, Yamaoka LH, Vance JM, Pericak-Vance MA. Periodic vestibulocerebellar ataxia, an autosomal dominant ataxia with defective smooth pursuit, is genetically distinct from other autosomal dominant ataxias. Arch Neurol 53: 338–344, 1996. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1996.00550040074016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dar MS. Sustained antagonism of acute ethanol-induced ataxia following microinfusion of cyclic AMP and cpt-cAMP in the mouse cerebellum. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 98: 341–348, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2010.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dar MS. Ethanol-induced cerebellar ataxia: cellular and molecular mechanisms. Cerebellum 14: 447–465, 2015. doi: 10.1007/s12311-014-0638-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey CW, Richardson DE. Paleocerebellar stimulation induces in vivo release of endogenously synthesized [3H]dopamine and [3H]norepinephrine from rat caudal dorsomedial nucleus accumbens. Neuroscience 21: 565–571, 1987. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(87)90142-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugué GP, Brunel N, Hakim V, Schwartz E, Chat M, Lévesque M, Courtemanche R, Léna C, Dieudonné S. Electrical coupling mediates tunable low-frequency oscillations and resonance in the cerebellar Golgi cell network. Neuron 61: 126–139, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugué GP, Dumoulin A, Triller A, Dieudonné S. Target-dependent use of co-released inhibitory transmitters at central synapses. J Neurosci 25: 6490–6498, 2005. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1500-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan C, Deitrich RA. A critical evaluation of tetrahydroisoquinoline induced ethanol preference in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 13: 265–281, 1980. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(80)90083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Ghundi M, George SR, Drago J, Fletcher PJ, Fan T, Nguyen T, Liu C, Sibley DR, Westphal H, O’Dowd BF. Disruption of dopamine D1 receptor gene expression attenuates alcohol-seeking behavior. Eur J Pharmacol 353: 149–158, 1998. doi: 10.1016/S0014-2999(98)00414-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figner B, Knoch D, Johnson EJ, Krosch AR, Lisanby SH, Fehr E, Weber EU. Lateral prefrontal cortex and self-control in intertemporal choice. Nat Neurosci 13: 538–539, 2010. doi: 10.1038/nn.2516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findlay GS, Wick MJ, Mascia MP, Wallace D, Miller GW, Harris RA, Blednov YA. Transgenic expression of a mutant glycine receptor decreases alcohol sensitivity of mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 300: 526–534, 2002. doi: 10.1124/jpet.300.2.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallaher EJ, Jones GE, Belknap JK, Crabbe JC. Identification of genetic markers for initial sensitivity and rapid tolerance to ethanol-induced ataxia using quantitative trait locus analysis in BXD recombinant inbred mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 277: 604–612, 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein RZ, Volkow ND. Dysfunction of the prefrontal cortex in addiction: neuroimaging findings and clinical implications. Nat Rev Neurosci 12: 652–669, 2011. doi: 10.1038/nrn3119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanchar HJ, Dodson PD, Olsen RW, Otis TS, Wallner M. Alcohol-induced motor impairment caused by increased extrasynaptic GABAA receptor activity. Nat Neurosci 8: 339–345, 2005. doi: 10.1038/nn1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare TA, Camerer CF, Rangel A. Self-control in decision-making involves modulation of the vmPFC valuation system. Science 324: 646–648, 2009. doi: 10.1126/science.1168450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi T, Ko JH, Strafella AP, Dagher A. Dorsolateral prefrontal and orbitofrontal cortex interactions during self-control of cigarette craving. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 4422–4427, 2013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1212185110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Q, Titley H, Grasselli G, Piochon C, Hansel C. Ethanol affects NMDA receptor signaling at climbing fiber-Purkinje cell synapses in mice and impairs cerebellar LTD. J Neurophysiol 109: 1333–1342, 2013. doi: 10.1152/jn.00350.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensbroek RA, Ruigrok TJ, van Beugen BJ, Maruta J, Simpson JI. Visuo-vestibular information processing by unipolar brush cells in the rabbit flocculus. Cerebellum 14: 578–583, 2015. doi: 10.1007/s12311-015-0710-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herting MM, Fair D, Nagel BJ. Altered fronto-cerebellar connectivity in alcohol-naïve youth with a family history of alcoholism. Neuroimage 54: 2582–2589, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill SY. Neural plasticity, human genetics, and risk for alcohol dependence. Int Rev Neurobiol 91: 53–94, 2010. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(10)91003-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill SY, Muddasani S, Prasad K, Nutche J, Steinhauer SR, Scanlon J, McDermott M, Keshavan M. Cerebellar volume in offspring from multiplex alcohol dependence families. Biol Psychiatry 61: 41–47, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge CW, Mehmert KK, Kelley SP, McMahon T, Haywood A, Olive MF, Wang D, Sanchez-Perez AM, Messing RO. Supersensitivity to allosteric GABAA receptor modulators and alcohol in mice lacking PKCepsilon. Nat Neurosci 2: 997–1002, 1999. doi: 10.1038/14795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotson JR. Clinical detection of acute vestibulocerebellar disorders. West J Med 140: 910–913, 1984. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard RJ, Trudell JR, Harris RA. Seeking structural specificity: direct modulation of pentameric ligand-gated ion channels by alcohols and general anesthetics. Pharmacol Rev 66: 396–412, 2014. doi: 10.1124/pr.113.007468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikai Y, Takada M, Mizuno N. Single neurons in the ventral tegmental area that project to both the cerebral and cerebellar cortical areas by way of axon collaterals. Neuroscience 61: 925–934, 1994. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90413-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikai Y, Takada M, Shinonaga Y, Mizuno N. Dopaminergic and non-dopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area of the rat project, respectively, to the cerebellar cortex and deep cerebellar nuclei. Neuroscience 51: 719–728, 1992. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90310-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikemoto S, McBride WJ, Murphy JM, Lumeng L, Li TK. 6-OHDA-lesions of the nucleus accumbens disrupt the acquisition but not the maintenance of ethanol consumption in the alcohol-preferring P line of rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 21: 1042–1046, 1997. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1997.tb04251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan JS, Mohr C, Hostetler CM, Ryabinin AE, Finn DA, Rossi DJ. Alcohol suppresses tonic GABAA receptor currents in cerebellar granule cells in the prairie vole: a neural signature of high-alcohol-consuming genotypes. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 40: 1617–1626, 2016a. doi: 10.1111/acer.13136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan JS, Mohr C, Rossi DJ. Opposite actions of alcohol on tonic GABAA receptor currents mediated by nNOS and PKC activity. Nat Neurosci 16: 1783–1793, 2013. doi: 10.1038/nn.3559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan JS, Nipper MA, Richardson BD, Jensen J, Helms M, Finn DA, Rossi DJ. Pharmacologically counteracting a phenotypic difference in cerebellar GABAA receptor response to alcohol prevents excessive alcohol consumption in a high alcohol-consuming rodent genotype. J Neurosci 36: 9019–9025, 2016b. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0042-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly RM, Strick PL. Cerebellar loops with motor cortex and prefrontal cortex of a nonhuman primate. J Neurosci 23: 8432–8444, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Roberts AJ, Schulteis G, Parsons LH, Heyser CJ, Hyytiä P, Merlo-Pich E, Weiss F. Neurocircuitry targets in ethanol reward and dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 22: 3–9, 1998. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb03611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Volkow ND. Neurocircuitry of addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology 35: 217–238, 2010. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levisohn L, Cronin-Golomb A, Schmahmann JD. Neuropsychological consequences of cerebellar tumour resection in children: cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome in a paediatric population. Brain 123: 1041–1050, 2000. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.5.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lex BW, Lukas SE, Greenwald NE, Mendelson JH. Alcohol-induced changes in body sway in women at risk for alcoholism: a pilot study. J Stud Alcohol 49: 346–356, 1988. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1988.49.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire EP, Mitchell EA, Greig SJ, Corteen N, Balfour DJ, Swinny JD, Lambert JJ, Belelli D. Extrasynaptic glycine receptors of rodent dorsal raphe serotonergic neurons: a sensitive target for ethanol. Neuropsychopharmacology 39: 1232–1244, 2014. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malila A. Intoxicating effects of three aliphatic alcohols and barbital on two rat strains genetically selected for their ethanol intake. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 8: 197–201, 1978. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(78)90337-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariqueo TA, Agurto A, Muñoz B, San Martin L, Coronado C, Fernández-Pérez EJ, Murath P, Sánchez A, Homanics GE, Aguayo LG. Effects of ethanol on glycinergic synaptic currents in mouse spinal cord neurons. J Neurophysiol 111: 1940–1948, 2014. doi: 10.1152/jn.00789.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascia MP, Machu TK, Harris RA. Enhancement of homomeric glycine receptor function by long-chain alcohols and anaesthetics. Br J Pharmacol 119: 1331–1336, 1996. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb16042.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascia MP, Wick MJ, Martinez LD, Harris RA. Enhancement of glycine receptor function by ethanol: role of phosphorylation. Br J Pharmacol 125: 263–270, 1998. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCracken LM, Trudell JR, McCracken ML, Harris RA. Zinc-dependent modulation of α2- and α3-glycine receptor subunits by ethanol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 37: 2002–2010, 2013. doi: 10.1111/acer.12192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihic SJ, Ye Q, Wick MJ, Koltchine VV, Krasowski MD, Finn SE, Mascia MP, Valenzuela CF, Hanson KK, Greenblatt EP, Harris RA, Harrison NL. Sites of alcohol and volatile anaesthetic action on GABAA and glycine receptors. Nature 389: 385–389, 1997. doi: 10.1038/38738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miquel M, Toledo R, García LI, Coria-Avila GA, Manzo J. Why should we keep the cerebellum in mind when thinking about addiction? Curr Drug Abuse Rev 2: 26–40, 2009. doi: 10.2174/1874473710902010026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittleman G, Goldowitz D, Heck DH, Blaha CD. Cerebellar modulation of frontal cortex dopamine efflux in mice: relevance to autism and schizophrenia. Synapse 62: 544–550, 2008. doi: 10.1002/syn.20525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr C, Kolotushkina O, Kaplan JS, Welsh J, Daunais JB, Grant KA, Rossi DJ. Primate cerebellar granule cells exhibit a tonic GABAAR conductance that is not affected by alcohol: a possible cellular substrate of the low level of response phenotype. Front Neural Circuits 7: 189, 2013. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2013.00189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morikawa H, Morrisett RA. Ethanol action on dopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area: interaction with intrinsic ion channels and neurotransmitter inputs. Int Rev Neurobiol 91: 235–288, 2010. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(10)91008-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morozova TV, Mackay TF, Anholt RR. Genetics and genomics of alcohol sensitivity. Mol Genet Genomics 289: 253–269, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s00438-013-0808-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newlin DB, Thomson JB. Alcohol challenge with sons of alcoholics: a critical review and analysis. Psychol Bull 108: 383–402, 1990. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto T, Harnett MT, Morikawa H. Hyperpolarization-activated cation current (Ih) is an ethanol target in midbrain dopamine neurons of mice. J Neurophysiol 95: 619–626, 2006. doi: 10.1152/jn.00682.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olbrich HM, Valerius G, Paris C, Hagenbuch F, Ebert D, Juengling FD. Brain activation during craving for alcohol measured by positron emission tomography. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 40: 171–178, 2006. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottersen OP, Storm-Mathisen J, Somogyi P. Colocalization of glycine-like and GABA-like immunoreactivities in Golgi cell terminals in the rat cerebellum: a postembedding light and electron microscopic study. Brain Res 450: 342–353, 1988. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)91573-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prescott CA, Kendler KS. Genetic and environmental contributions to alcohol abuse and dependence in a population-based sample of male twins. Am J Psychiatry 156: 34–40, 1999. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan JJ, Ferguson C, Jester K, Firestone LL, Homanics GE. Mice with glycine receptor subunit mutations are both sensitive and resistant to volatile anesthetics. Anesth Analg 95: 578–582, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn PD, Fromme K. Subjective response to alcohol challenge: a quantitative review. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 35: 1759–1770, 2011. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01521.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragge NK, Hartley C, Dearlove AM, Walker J, Russell-Eggitt I, Harris CM. Familial vestibulocerebellar disorder maps to chromosome 13q31-q33: a new nystagmus locus. J Med Genet 40: 37–41, 2003. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risinger FO, Freeman PA, Rubinstein M, Low MJ, Grandy DK. Lack of operant ethanol self-administration in dopamine D2 receptor knockout mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 152: 343–350, 2000. doi: 10.1007/s002130000548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]