Abstract

Osteoporosis is a major public health problem. Last decade has seen rise in osteoporotic vertebral fractures. Pragmatic management of osteoporotic VCF is challenging to the surgeons. In clinical settings, the situation becomes more complex when it comes to managing painful osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures (VCFs) due to various co-morbid factors that may limit aggressive interventions. Patients with Osteoporotic vertebral fractures are often characterized by general/relative immobility and physical frailty. Osteoporotic VCF not only affects the quality of life (e.g. pain) but also decreases the lifespan of the individual. The present review critically evaluates the currently prevailing non-surgical management modalities (conservative) offered in acute symptomatic osteoporotic VCFs that occur either within (0–5 days) of any incident event or present with the onset of symptoms such as pain.

Keywords: Osteoporosis, Vertebral, Surgical, Fracture

1. Introduction

Osteoporosis is becoming a major public health concern. With increasing life expectancy, the world demography is destined to change towards an elderly population, making senile osteoporosis a global challenge to tackle.

Osteoporosis is a systemic skeletal disorder in which the micro-architecture of the bone tissue gets deteriorated, leading to decreased bone mass, fragility, and thus increasing the risk of fractures. The magnitude of the problem is enormous as more than 10 million people (>50 years) were living with osteoporosis in USA alone as reported in 2004.1 Out of 1.5 million osteoporotic fractures, half of them accounts towards vertebral fractures. The most common form of osteoporotic fracture is a vertebral compression fracture (VCF). However, only one third of vertebral compression fractures are symptomatic and present with pain.2

According to the European Vertebral Osteoporosis study, women are more prone to develop vertebral deformity than men which increase exponentially with age i.e. from 5% at 50 years to 25% at 75 years in women and from 10% to 18% in men.3 By 2020, it is projected that one in two American (over age 50) is likely to have osteoporosis of the hip or osteoporosis at any other site in the skeleton.4

2. Clinical importance

A vertebral compression fracture (VCF) is characterized by decrease in height of at least 20% of anterior, posterior, or middle part of vertebra, or decrease of at least 4 mm of height as compared to baseline height (estimated based on vertebral body height of upper or lower vertebra).5

Unfortunately, the majority (two-third) of vertebral fractures are not diagnosed because they do not come to clinical attention. An osteoporotic vertebral fracture increases the possibility of future fracture risk irrespective of being symptomatic or asymptomatic in nature. There can be episodes of acute and chronic pain in these patients. Approximately, 1 in 5 men and women over 50 years of age have one or more vertebral fractures.5

3. Risk factors for osteoporotic vertebral fractures

-

•

Age (above 50 years)6

-

•

Sex (elderly women are at high risk than men)7

-

•

Race/Ethnicity (higher risk in black women than white women)8

-

•

Consumption of Alcohol (3 or More drinks/day)/current smoking

-

•

History of taking drugs i.e. glucocorticoids, anti-thyroid medication, anti-tubercular medication

-

•

Previous history of fracture (including morphometric fracture)

-

•

Decrease in Height

-

•

Decreased Body Mass Index (kg/m2)

-

•

Femoral neck BMD

-

•

Rheumatoid Arthritis

-

•

Secondary Osteoporosis

-

•

Vitamin D deficiency

-

•

Genetic history of vertebral fractures in first degree of relatives

The US National Osteoporosis Foundation in 2014 suggested that spine imaging should be considered into account for the following conditions (Table 1).

Table 1.

Criteria for spine Imaging.

| S.No. | Gender | Age (years) | BMD Region | T Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Women | ≥70 | LS Spine, femoral neck | ≤ −1.0 |

| 2. | Men | ≥80 | LS Spine, femoral neck | ≤ −1.0 |

| 3. | Women | 65–69 | LS Spine, femoral neck | ≤ −1.5 |

| 4. | Men | 70–79 | LS Spine, femoral neck | ≤ −1.5 |

(Adapted from National Osteoporosis Foundation)(2014).9

4. Clinical examination

-

•

Postural changes (focal kyphosis and loss of lumbar lordosis)

-

•

Decrease in height

5. Physical examination

-

•

Weakness secondary to nerve root compression due to retro-pulsed bony fragment or narrowing of neural foramina.

-

•

There will be positive straight leg raising test

6. Diagnosis

Imaging modalities for assessment of vertebral fractures

-

•

Radiography (Anteroposterior and Lateral)

-

•

Computerized tomography

-

•

Magnetic resonance imaging

-

•

Dual energy X-ray absorpitometry (DXA) for vertebral fracture assessment

Studies have shown that X-ray is the best diagnostic tool than CT for the recognition of vertebral fractures.10 While reporting the incidence of vertebral fracture, the clinical interpretation of spine imaging should be done in a clearly and decisive manner. Following points are useful in interpretation (identification and exclusion).

-

1.

Quality of radiograph

-

2.

Sign of malignancy, if any

-

3.

Severity of fracture using standard methodology (grades i.e. mild, moderate and severe)

-

4.

Location of fracture

-

5.

Number of fracture

-

6.

Identification of pathological fractures (e.g, those due to multiple myeloma, metastatic cancer or infection)

-

7.

Fracture due to with or without trauma

-

8.

History of congenital and developmental abnormalities.

-

9.

Identification of bone edema on MRI

7. Static radiograph

Static radiographs (Fig. 1a) are used to identify the type of fracture, the location, and documenting any vertebral loss of body height. When the collapse is not evident, MRI can be used to confirm the diagnosis.

Fig. 1.

a- Collapse Osteoporotic Vertebral fracture. b- Demonstrating instability in Flexion-Extension view.

8. Dynamic radiograph (Flexion-extension views)

For patients who have a VCF the dynamic radiographs are not possible as immobilization is a priority. Relative position of vertebra from hyper flexion to hyperextension can also be determined using these radiographs. Vacuum clefts (gas like area of radiolucency) and change of kyphotic angle can be ruled out using dynamic radiograph. Dynamic radiographs are useful in detection of unstable vertebral fracture in which there is retropulsion of bony fragment. (Fig. 1b)

9. Bone scan and MRI

Both bone scan and MRI are useful tools to determine the time since compression fracture, especially when trauma and fall history is negative. If the fracture history/presentation is of less than 10 days, MRI will show decreased signal on T1 sequences and marrow edema on T2 fat-saturation at the site of fracture (Fig. 2) whereas Bone scan will not show a fracture.

Fig. 2.

Showing Psuedoarthosis in D12 vertebral body.

Before labeling as VCF, pathological fracture must be ruled out. The presence of soft-tissue mass or pedicle involvement on MRI is usually suggestive of tumor. There will be multiple areas of increased radionuclide uptake due to metastatic lesions in vertebra which can be identified on a bone scan.

Additionally, a positron emission tomography scan with fluoride-18 deoxyglucose (FDG-PET) can differentiate between osteoporotic and pathological vertebral fracture due to a high FDG uptake.11

10. FRAX assessment

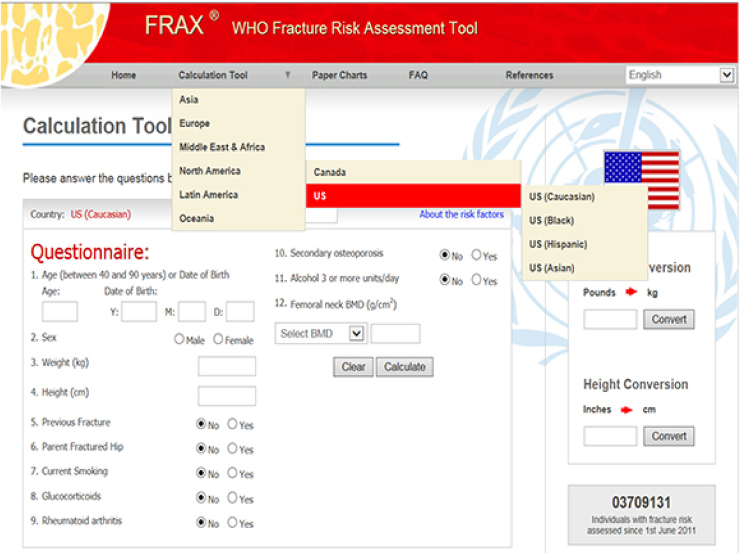

Fracture risk assessment is important and helpful in the prediction of future fracture risk (next 10 year risk). A FRAX model is helpful in reviewing fracture risk assessment with or without BMD. The patient can pick a country under the Calculation Tool before them and access the FRAX tool (Fig. 3). A recent study shows that a pre-BMD FRAX score helps to find the postmenopausal patients who are at risk and might require treatment and also decreases unnecessary DXA use.

Fig. 3.

WHO FRAX assessment tool.

(Adapted from FRAX®: Prediction of Major Osteoporotic Fractures in Women from the General Population.)12

11. Classification

Although several classification systems of vertebral fracture are given, but the most commonly used classification system for VCF in clinical practice was described by Sugita et al.13 In this classification system there are 5 types of fractures identified on lateral radiographic views that distinguishes fracture with different prognosis (Table 2) (Fig. 4).

Table 2.

Classification of osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures.

| S.No. | Types of vertebra | Shape | Characteristics | Prognosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Concave | Collapse of upper endplate without any fracture of the anterior wall | Short painful period & rapid healing | Good |

| 2. | Dented | Fracture line interrupt the anterior wall | Short painful period & rapid healing | Good |

| 3. | Swelled front | Anterior wall is convex anteriorly by more than 50% | Significant bone loss, painful, slow healing | Poor |

| 4. | Bow shaped | Collapse of upper end plate with anterior wall is pinched inwards | Significant bone loss, painful, slow healing | Poor |

| 5. | Projecting | Anterior wall is convex anteriorly by less than 50% | Significant bone loss, painful, slow healing | Poor |

Fig. 4.

Classification of Vertebral Fracture in Elderly.

(Adapted from: Sugita M. et al. J. Spinal Disord Tech 18, 4, 2005).13

12. Predictors of vertebral fracture

A simple and feasible strategy to report an incident of vertebral fracture is to monitor a patient’s height with a wall-mounted stadiometer. Siminoski et al. have shown that historical height loss >6 cm or measured height loss >2 cm followed over 1–3 years is highly predictive of an underlying vertebral fracture.14

13. Management

Conservative management of osteoporotic vertebral fractures patients comprises of Pain relief and Rehabilitation. Usually surgery is not required for all acute osteoporotic VCF unless, complicated by neurological deficit.

The goal of management should consider three aspects:

-

•

Improvement of quality of life

-

•

Assessment of risk-benefit ratio

-

•

Cost-effectiveness

The management of acute VCF usually includes:

-

•

Short-term bed rest

-

•

Pain relief with medications

-

•

Bracing

-

•

Physical Therapy

13.1. Pain relief

The acute pain due to new vertebral fracture generally resolves within 6–12 weeks with analgesics. Analgesia can be started with acetaminophen or salicylates and non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).15 Additionally; opioids can be used along with first line of medications in those patients who didn’t experience relief from pain adequately.16

The role of muscle relaxant may be helpful in the management of painful paravertebral muscle spasms and they are significantly beneficial in the initial 1 or 2 weeks of treatment. Muscle relaxants should not be given for long as they can produce potential side effect such as drowsiness, dizziness, dependence and abuse in long term period.17 If the above general measures don’t comply, calcitonin may be given as an analgesic, with discontinuation after 6–12 weeks.18

Bisphosphonates and teriparatide can also be used to relieve acute rapid and sustained pain relief.19, 20 Since the introduction of teriparatide for treating osteoporosis, there have been reports of improvements in back pain with teriparatide treatment which may be related to decrease incidence of new vertebral compression fractures.20

13.2. Bracing

The use of bracing can be an initial step in the management of patients with osteoporotic compression vertebral fracture. Bracing can be helpful in pain reduction from movement by stabilizing the spine. Bracing also reduced back fatigue which helps patients in an early mobilization. Therefore, bracing is mandatory during the initial 6–8 weeks for pain relief.21

There are several kinds of braces which are commonly used mostly in cases of acute VCF.

An ideal brace should be light weighted, easy wearing, and comfortable with compatible cushions. Thus, the choice to use a specific brace is based on patients need, clinical status and type & level of fracture. The different braces are used for different purposes (Table 3) (Fig. 5).

Table 3.

Different types of braces for the management of osteoporotic VCF.

| S.No. | Types of Braces | Design | Merits/benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Thoracolumbar Orthoses (TLO) | ||

| Jewett and Cruciform anterior spinal hyperextension (CASH brace) |

|

|

|

| Cheneau brace |

|

||

| Taylor brace |

|

||

| Knight-Taylor brace |

|

|

|

| 2. | Thoraco-lumbarsacral orthosis (TLSOs) | Custom-molded body jacket |

|

| 3. | Lumbosacral orthosis (LSO) |

|

|

| 4. | Chairback braces |

|

|

Fig. 5.

Most commonly used braces.

1. Thoracolumbar orthoses (TLO)

-

•

Jewett brace

-

•

ASHE brace

-

•

Cheneau brace

-

•

Taylor brace

-

•

Knight-Taylor brace

2. Thoraco-lumbarsacral orthosis (TLSOs)

3. Lumbosacral orthosis (LSO)

4. Chairback brace

Studies have shown that a custom-molded TLSO worn in hyperextension is used to manage a severe osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture.2

Acceptability of braces may be an issue with few patients who can’t tolerate it. Few patients don’t wish to wear braces due to social and other practical reasons such as thick skin overlying bony prominences or impaired respiratory functions (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Flow chart of Management of Acute osteoporotic vertebral compression Fracture.

13.3. Other physical modalities

Following modalities are used by various treating surgeons worldwide, however there is no convincing evidence either in favor or against. These may include:

-

•

Ultrasound

-

•

Hydrotherapy

-

•

Ice/heat application

-

•

TENS

-

•

Acupuncture

14. Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation of patients with a vertebral fracture is of utmost importance. The goal of rehabilitation includes

-

•

Exercise programme

-

•

Fall Prevention Program

-

•

Decrease in kyphosis

-

•

Improving axial muscle strength

-

•

Maintaining correct spine alignment

Additionally, a spinal extensor muscle strengthening program and dynamic proprioceptive program demonstrated by Sinaki et al. are extremely helpful in increasing bone density and reduction of VCFs.22 Back extension exercises are much helpful in reducing the incidence of new fracture than abdominal flexion exercises (16% vs 89% respectively). Our preference is to use early mobilization, Stretching exercises to decrease muscle spasm, gentle strengthening exercise program, gait training and flexibility exercises. Besides we also refer these patients to our fragility fracture program for fall prevention and balance training.

An increase in kyphosis usually occurs in patients with osteoporotic vertebral fracture and can cause pain and respiratory distress. For reducing kyphotic deformity, back extensor exercises provide better dynamic-static postural support. A randomized controlled trial performed by Papaioannou et al. showed better outcomes with home exercise program in patients with vertebral fracture. There was an improvement in the quality of life over 6 month.23 Studies by Malmros et al. and Bennel et al. given a 10 week exercise programme were also in concordance with the above studies.24, 25 Keeping in view of these above reports, physiotherapy and exercise has an important role in pain relief and improvement in quality of life.

Patients should also be advised to avoid such activities that may put them at risk for more vertebral fractures which include

-

•

Forward bending

-

•

Exercising with trunk in flexion

-

•

Twisting

-

•

Sudden abrupt movements

-

•

Jumping, and jarring movements

-

•

High-intensity exercise and heavy weight-lifting.

Moreover, the degree of activity restriction should be prescribed as per clinical judgment.

15. Prevention of subsequent vertebral fractures

Anti-osteoporotic regimens along with other pharmacologic therapies can significantly mitigate the chance of future vertebral fracture therefore patients diagnosed with vertebral fracture should be soon offered appropriate therapy at their earliest convenience. Identification of a vertebral fracture is an important part of a fracture liaison services. Effective fall prevention programmes (FPPs) applicability needs to be evaluated in specific health care settings before use in daily clinical practice. Multidisciplinary approach using home-based fall prevention method detects the risk of falling in seniors.26

-

•

Assessment of fracture risk; an important tool to estimate 10 year fracture risk assessment (FRAX).

-

•

BMD assessment (at Spine, hip and forearm)

-

•

Bone homeostasis (Vitamin D estimation, Calcium, Phosphorous, Alkaline phosphatase, and Parathyroid hormone)

-

•

Bone turnover markers assessment (BALP, BCTx, P1NP and NTx)

-

•

Fall prevention programmes26

-

•

Secondary fracture prevention programme

-

•

Gait and balance training

-

•

Bone health education

-

•

Pharmacotherapy

16. Approach to osteoporotic VCF

The main focus of non-surgical management should be based on providing optimum care to the patient. Randomised clinical trial study done by Buchbinder et al. and Kallmes et al. have found that there is no difference in disability and pain score between vertebroplasty and sham surgery method in patients with symptomatic osteoporotic VCF of less than 12 months duration.27, 28 Caution to be used in patients with multiple comorbidities, as prolonged bed rest/periods of inactivity with conservative treatment may lead to complications due to prolonged immobilization.29

Hazzard M.A et al. found that conservative group patients are less likely to undergo of reoperation as compared to patients who underwent operation for VCF during the initial stage and on long term authors found that irrespective of treatment modality (surgically or conservatively) patients with VCF are likely to be associated with long term complications.29

Osteoporosis most commonly presents as vertebral fracture in women with increasing prevalence with age is seen both in men and women. There is no increased risk of vertebral fracture seen among black and white women in South Africa.30

In osteoporotic VCFs the chance for trunk muscle complications are higher due to higher bone-muscle interaction. With the use of Dynamic orthosis, there is improvement in the quality of life and pain relief in patients with osteoporotic compression fracture.8 Among anti-osteoporotic treatment regimens for Osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures, teriparatide was found better than alendronate at improvement of BMD along with bone turn over parameter.31

Shah S. and colleagues used a multidisciplinary primary approach for conservative management of osteoporotic vertebral fractures and found it effective in alleviating pain, reducing morbidity, reducing disease progression clinically and radiologically.32

17. Summary

Osteoporotic vertebral fractures affect quality of life. Unfortunately to date, current understanding and knowledge for osteoporotic VCF are inconclusive. However, this review highlighted all the relevant non operative methods in the management of osteoporotic vertebral fractures. Treatment decisions should focus on improvement of quality of life of the patient, risk-benefit ratio and cost-effectiveness as well. Further, superior level of studies should be conducted to answer these vague conditions. Preventive and public health measures such as screening for osteoporosis in the community and fracture prevention strategies to include identification of risk factors are major methods to mitigate the rising burden of Osteoporotic vertebral fractures in the near future.

References

- 1.Sunyecz J.A. The use of calcium and vitamin D in the management of osteoporosis. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2008;4(August (4)):827–836. doi: 10.2147/tcrm.s3552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Longo U.G., Loppini M., Denaro L., Maffulli N., Denaro V. Osteoporotic vertebral fractures: current concepts of conservative care. Br Med Bull. 2011;102(1):171–189. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldr048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Neill T.W., Felsenberg D., Varlow J. The prevalence of vertebral deformity in European men and women: the European Vertebral Osteoporosis Study. J Bone Miner Res. 1996;11:1010–1018. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650110719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Osteoporosis Foundation . National Osteoporosis Foundation; Washington (DC): 2002. America’s Bone Health: The State of Osteoporosis and Low Bone Mass in Our Nation. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong C.C., McGirt M.J. Vertebral compression fractures: a review of current management and multimodal therapy. J Multidiscip Healthcare. 2013;6:205–214. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S31659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crandall C.J., Larson J.C., Watts N.B. Comparison of fracture risk prediction by the US Preventive Services Task Force strategy and two alternative strategies in women 50–64 years old in the Women's Health Initiative. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(12):4514–4522. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-2332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cawthon P.M. Gender differences in osteoporosis and fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(July (7)):1900–1905. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-1780-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conradie M., Conradie M.M., Scher A.T., Kidd M., Hough S. Vertebral fracture prevalence in black and white South African women. Arch Osteoporos. 2015;10:203. doi: 10.1007/s11657-015-0203-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Osteoporosis Foundation . National Osteoporosis Foundation; Washington, DC: 2014. Clinician’s Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Panda A., Das C.J., Baruah U. Imaging of vertebral fractures. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2014;18(May–June (3)):295–303. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.131140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmitz A., Risse J.H., Textor J. FDG-PET findings of vertebral compression fracture in osteoporosis: preliminary results. Osteoporosis Int. 2002;13:755–761. doi: 10.1007/s001980200103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Briot K., Paternotte S., Kolta S. FRAX®: prediction of major osteoporotic fractures in women from the general population: the OPUS study. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e83436. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sugita M., Watanabe N., Mikami Y., Hase H., Kubo T. Classification of vertebral compression fractures in the osteoporotic spine. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2005;18(4):376–381. doi: 10.1097/01.bsd.0000168716.23440.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siminoski K., Warshawski R.S., Jen H., Lee K. The accuracy of historical height loss for the detection of vertebral fractures in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17:290–296. doi: 10.1007/s00198-005-2017-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lyles K.W. Management of patients with vertebral compression fractures. Pharmacotherapy. 1999;19:21S–24S. doi: 10.1592/phco.19.2.21s.30908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cherasse A., Muller G., Ornetti P. Tolerability of opiods in patients with acute pain due to non-malignant musculoskeletal disease: a hospital based observational study. Joint Bone Spine. 2004;71:572–576. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2003.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Browning R., Jackson J.L., O’Malley P.G. Cyclobenzaprine and back pain: a meta analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1613–1620. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.13.1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knopp J.A., Diner B.M., Blitz M. Calcitonin for treating acute pain of osteoporosis vertebral compression fracture: a systematic review of randomized, controlled trials. Osteoporosis Int. 2005;16:1281–1290. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1798-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rovetta G., Maggiani G., Molfette L. One-month follow-up of patient treated by intra-venous clodronate for acute pain induced by osteoporotic vertebral fracture. Drugs Exp Clin Res. 2001;27(27):77–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nevitt M.C., Chen P., Keil P.D. Reduction in the risk of developing back pain persists at least 30 month after discontinuation of teriparatide treatment: a meta analysis. Osteoporosis Int. 2006;17:1630–1637. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0177-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim D.H., Vaccaro A.R. Osteoporotic compression fractures of the spine; current options and consideration of the treatment. Spine J. 2006;6:479–487. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2006.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sinaki M., Itoi E., Wahner H.W. Stronger back muscles reduce the incidence of vertebral fractures: a prospective 10 year follow-up of postmenopausal women. Bone. 2002;30:836–841. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(02)00739-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Papaioannou A., Adachi J.D., Parkinson W. Lengthy hospitalization associated with vertebral fractures despite control for comorbid conditions. Osteoporos Int. 2001;12:870–874. doi: 10.1007/s001980170039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malmros B., Mortensen L., Jensen M.B. Positive effects of physiotherapy on chronic pain and performance in osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 1998;8:215–221. doi: 10.1007/s001980050057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bennell K.L., Matthews B., Greig A. Effects of an exercise and manual therapy program on physical impairments, function and quality-of-life in people with osteoporotic vertebral fracture: a randomised, single-blind controlled pilot trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11:36. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-11-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amachesr A.E., Nast I., Zindel B., Schmid L., Krafft V., Niedermann K. Experiences of general practitioners, home care nurses, physiotherapists and seniors involved in a multidisciplinary home-based fall prevention programme: a mixed method study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(September (5)):469. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1719-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buchbinder R., Osborne R.H., Ebeling P.R. A randomized trial of vertebroplasty for painful osteoporotic vertebral fractures. N Engl J Med. 2009;6361(6):557–568. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kallmes D.F., Comstock B.A., Heagerty P.J. A randomized trial of vertebroplasty for osteoporotic spinal fractures. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(6):569–579. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900563. Aug 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hazzard M.A., Huang K.T., Toche U.N. Comparison of vertebroplasty, kyphoplasty, and nonsurgical managementof vertebral compression fractures and impact on US healthcare resource utilization. Asian Spine J. 2014;8(5):605–614. doi: 10.4184/asj.2014.8.5.605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Waterloo S., Ahmed L.A., Center J.R. Prevalence of vertebral fractures in women and men in the population-based Tromsø Study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;17(13):3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-13-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao Y., Xue R., Shi N. Aggarvation of spinal cord compromise following new osteoporotic vertebral fracture prevented by teriparatide in patients with surgical contraindications. Osteoporos Int. 2016;27(November (11)):3309–3317. doi: 10.1007/s00198-016-3651-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shah S., Goregaonkar A.B. Conservative management of osteoporotic vertebral fractures: a prospective study of thirty patients. Cureus. 2016;8(3):e542. doi: 10.7759/cureus.542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]