Abstract

Selective delivery of anticancer drugs to rapidly growing cancer cells can be achieved by taking advantage of their high receptor-mediated uptake of low-density lipoproteins (LDLs). Indeed, we have recently discovered that nanoparticles made of the squalene derivative of the anticancer agent gemcitabine (SQGem) strongly interacted with the LDLs in the human blood. In the present study, we showed both in vitro and in vivo that such interaction led to the preferential accumulation of SQGem in cancer cells (MDA-MB-231) with high LDL receptor expression. As a result, an improved pharmacological activity has been observed in MDA-MB-231 tumor-bearing mice, an experimental model with a low sensitivity to gemcitabine. Accordingly, we proved that the use of squalene moieties not only induced the gemcitabine insertion into lipoproteins, but that it could also be exploited to indirectly target cancer cells in vivo.

Keywords: squalene-based nanoparticles, gemcitabine, low-density lipoproteins, indirect targeting, cancer

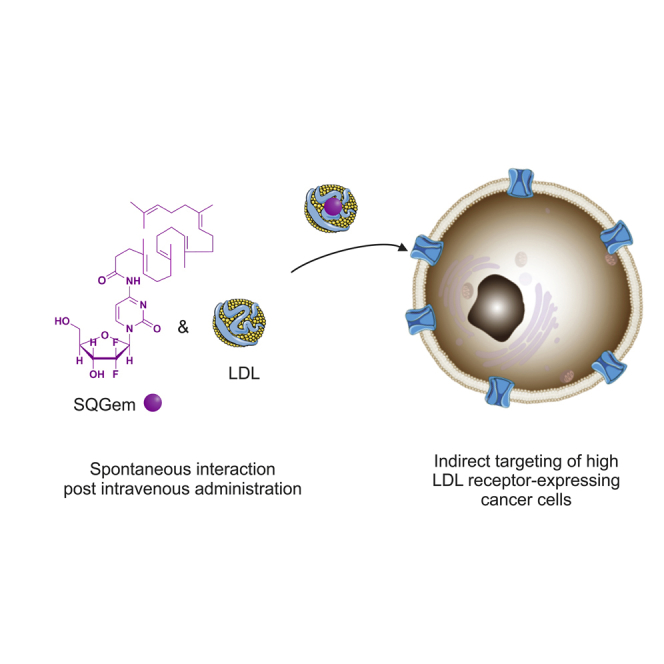

Graphical Abstract

We have demonstrated that the squalene derivative of the anticancer agent gemcitabine (SQGem) is capable of strongly interacting with the LDLs. This interaction enabled the preferential accumulation of the SQGem in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells with high LDL receptor expression and led to improved pharmacological activity in tumor-bearing mice.

Introduction

Selective delivery of anticancer compounds to tumor cells might be achieved by taking advantage of some unique features displayed by these cells, such as the increased metabolic requirements associated with their elevated proliferation rate.1 For instance, higher amounts of cholesterol are essential for cell proliferation, in order to build more cell membranes.2 This observation is supported by epidemiological studies that revealed a reduction in plasma cholesterol levels in patients suffering from certain types of cancer.3, 4, 5, 6 Later on, a high-fat diet-induced hypercholesterolemia was recognized as a factor of an enhanced aggressiveness in several animal tumor models.7, 8, 9 In addition, a large number of emerging reports continue to reveal the complex role of cholesterol in cancer development and progression.10, 11, 12 Intracellular cholesterol levels can be regulated by cancer cells through de novo synthesis or receptor-mediated uptake of low-density lipoproteins (LDLs), which are the main source of cholesterol for the peripheral tissues.13 Uptake of LDLs is often used by fast proliferating cancer cells to satisfy their cholesterol needs, as supported by the observation that various hematological14, 15 and solid tumors16, 17, 18 display an increased uptake of LDLs compared with healthy tissues.3

In this view, endogenous, long-circulating LDL particles have been proposed as delivery vehicles for lipophilic anticancer drugs.18, 19, 20 LDL, an approximately 22-nm particle, is composed of a hydrophobic core containing cholesterol esters and triglycerides surrounded by a phospholipid monolayer containing free cholesterol and a single copy of apolipoprotein B-100 (apoB-100), which is responsible for the interaction with LDL receptors (LDLRs).21, 22 Many examples of increased efficacy of anticancer agents after their incorporation into LDL particles isolated from human plasma have been reported.23, 24, 25, 26, 27 However, the main challenges of this approach rely on the complex isolation of LDLs from human plasma and their preservation in intact form, the potential pathogen contamination, the need for efficient drug loading techniques, as well as the limited stability of the resulting drug-LDL complexes.26, 28 In an attempt to overcome some of these drawbacks, synthetic LDL-like particles consisting of commercial lipids were developed.29, 30 Nevertheless, other difficulties (e.g., availability of apoB-100, batch reproducibility, and production costs) have thwarted this promising approach,31, 32 thus seriously hampering any further industrial development. In contrast to these somewhat complicated approaches, we have recently observed that it was possible to exploit the circulating lipoproteins as indirect natural carriers of intravenously administered drug molecules, if these drugs are equipped with a LDL affine moiety.33

The proof of concept of this approach has been achieved by the chemical linkage of the anticancer drug gemcitabine (Gem) to squalene (SQ; a natural lipid precursor of the cholesterol’s biosynthesis), which additionally triggers the self-assembly of the SQ-drug bioconjugates into nanoparticles (SQGem NPs).34 The conjugation to SQ has also allowed for reduction of Gem blood clearance and metabolization, and also achievement of improved anticancer efficacy on different experimental tumor models, compared with the free drug.35, 36 Moreover, we have recently discovered that by virtue of the bio-similarity between SQ and cholesterol (the natural load of lipoproteins), the SQGem bioconjugates were capable of spontaneously interacting and then being transported by plasma lipoproteins in the blood circulation, in particular via cholesterol-rich ones, both in vitro in human blood and in vivo in rodents, whereas the free drug did not interact with lipoproteins.33 In the present study, whether the spontaneous interaction between SQGem NPs and LDLs (i.e., cholesterol-rich particles in humans) could mediate the targeting toward cancer cells with high LDLR activity has been investigated. We showed that the level of LDLRs positively affected the uptake and cytotoxicity of SQGem NPs in vitro, and the same behavior was observed also in vivo in tumor-bearing mice. These results provided evidence that the insertion of Gem into lipoproteins, driven by the SQ moiety, can be applied for indirect cancer cell targeting and improvement of the drug therapeutic profile.

Results and Discussion

Preparation and Characterization of SQGem, 2H-SQGem, and 3H-SQGem NPs

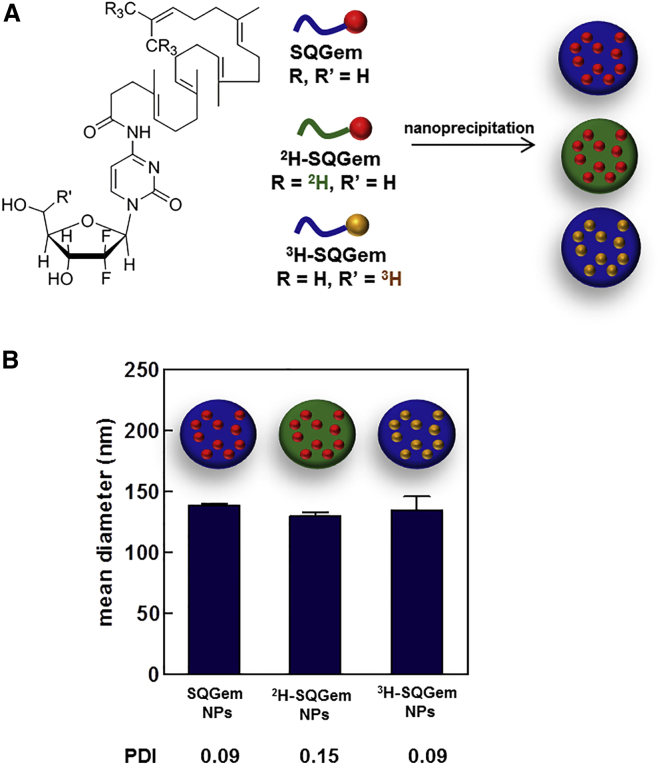

The SQGem bioconjugate has been synthesized as previously described by chemical linkage of the 1,1’,2-trisnorsqualenic acid onto the C-4 amino group of the Gem.34 2H-SQGem was similarly prepared using hexadeutero-trisnorsqualenic acid, whereas 3H-SQGem was obtained by coupling 5′-3H-Gem with 1,1’,2-trisnorsqualenic acid. NPs were prepared by nanoprecipitation of the organic solution of SQGem in water and subsequent solvent evaporation. Deuterated (2H-SQGem)37 and tritiated (3H-SQGem)38 bioconjugates were used to track NPs and quantify their uptake (Figure 1A). Neither nanoparticle size nor polydispersity index was affected by the labeling procedures: size of nanoparticles was around 130 nm, displaying narrow size distribution (polydispersity index < 0.2) (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Structures of the Bioconjugates and Physico-chemical Properties of the NPs Used in This Study

(A) Chemical structures of SQGem, 2H-SQGem, and 3H-SQGem bioconjugates, and schematic representation of the corresponding unlabeled, deuterated, and tritiated NPs prepared according to the nanoprecipitation technique. Color changes as compared with the unlabeled bioconjugate highlight chemical modification on the SQ (green) or the Gem (yellow) moiety. (B) Mean diameter and polydispersity index (PDI) of SQGem, 2H-SQGem, and 3H-SQGem NPs.

SQGem and Gem Cytotoxicity and LDLR Expression in Cancer Cell Lines

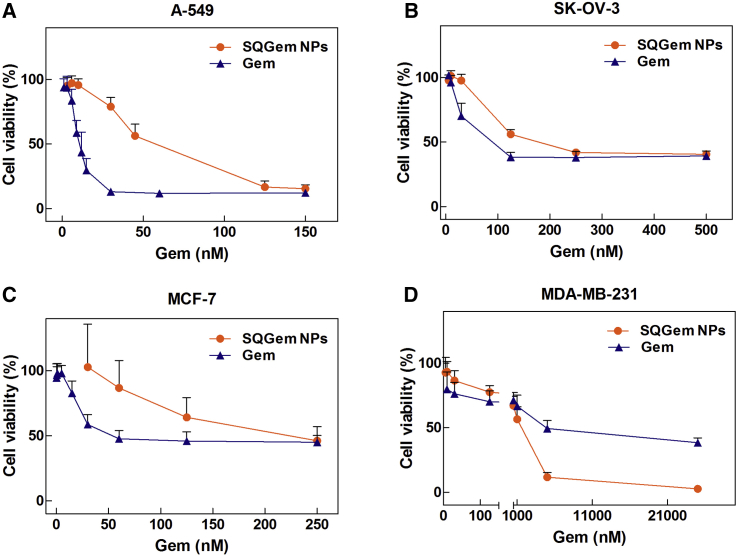

The in vitro cytotoxicity of SQGem NPs and free Gem was assessed on human cancer cell lines using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) viability assay. The choice of tested cell lines was based on: (1) the existing literature data concerning the correlation between the cholesterol uptake and the cancer progression, and/or (2) the clinical therapeutic indications for Gem.39 Hence four different human cancer cell lines were chosen: lung cancer (A-549),40, 41 ovarian cancer (SK-OV-3),42 and two breast cancer cell lines (MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231).7, 17 Cells were exposed to a range of different concentrations of SQGem NPs or free Gem for 72 hr; then the half maximal inhibitory concentration of cell proliferation (IC50) was calculated. The IC50 values measured for Gem on A-549, SK-OV-3, and MCF-7 cells were lower comparatively to SQGem NPs (Figures 2A–2C), in agreement with previous observations with other cell lines.35, 43 This is ascribed to the prodrug nature of SQGem, resulting in delayed cytotoxicity. An opposite behavior was instead observed with the MDA-MB-231 cells for which a 4-fold lower IC50 value was observed with the SQGem NPs compared with the free drug (1.5 μM versus 6.8 μM) (Figure 2D). Among the four different cell lines, we had previously showed that the MDA-MB-231 displayed the highest expression of LDLRs.33 Thus, the observed higher cytotoxicity of SQGem nanoparticles compared with the free drug, together with the overexpression of LDLRs, made this cell line an attractive tool to investigate the implication of LDLRs in SQGem uptake and pharmacological activity.

Figure 2.

SQGem NPs and Gem Cytotoxicity

(A–D) Cell viability of (A) A-549, (B) SK-OV-3, (C) MCF-7, and (D) MDA-MB-231 cells treated with increasing concentrations of Gem as free drug or in the form of SQGem NPs for 72 hr at 37°C. Values represent mean ± SD.

In Vitro and In Vivo SQGem Uptake in Breast Cancer Cells with Different LDLR Expression

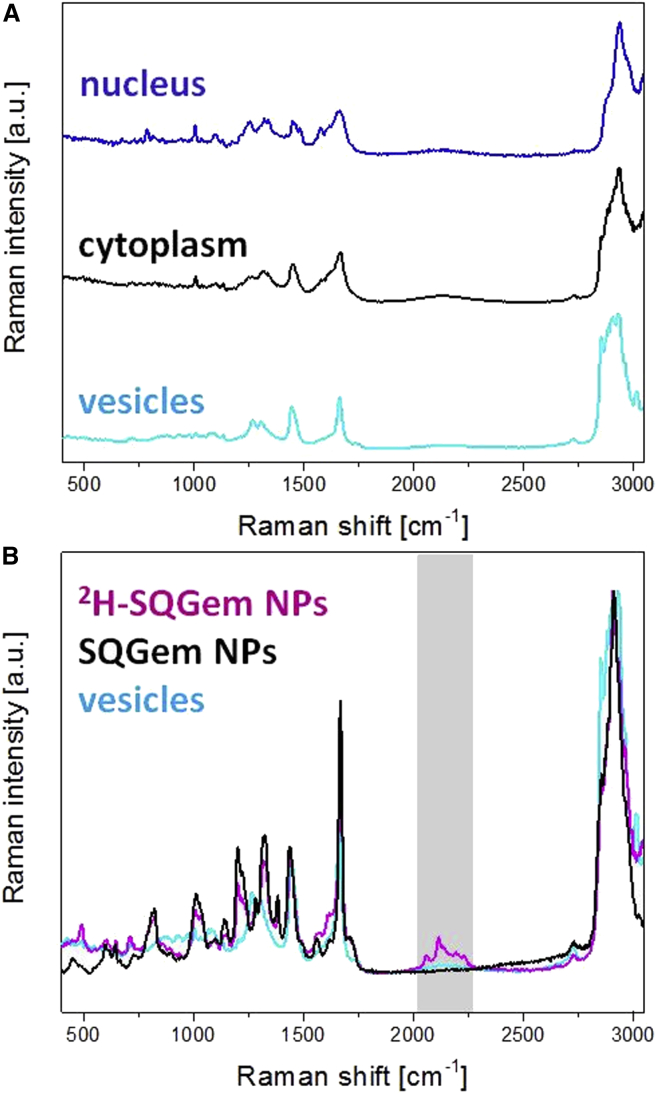

The contribution of the LDLR in the cell uptake of SQGem NPs was further investigated on MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 breast cancer cells, displaying respectively high and low levels of LDLR expression.33 NP cell uptake and intracellular localization were visualized by confocal Raman microscopy, an emerging method for the analysis of therapeutics and their interactions with biological tissues.44 Confocal Raman microscopy allows for chemically selective analysis, because different molecular structures scatter the laser light in different patterns. However, appropriate spectral assignment is frequently a challenge for cell imaging because each compartment (i.e., nucleus, cytoplasm, and intracellular lipid droplets) contributes to the overall Raman spectrum of the cell (Figure 3A), thus restraining differentiation of chemically similar compounds. The use of NPs resulting from the self-assembly of a deuterated SQGem bioconjugate (2H-SQGem)37 enabled differentiation of the endogenously similar Raman spectra of SQ-based NPs and intracellular lipid droplets (Figure 3B). Such deuterated SQGem NPs allowed for detection and visualization by confocal Raman microscopy even in the lipid-rich intracellular environment, based on the unique spectral bands of the deuterium isotope generated in the so-called silent region (around 2,200 cm−1), in which no significant spectral contributions of other biomacromolecules are observed (Figure 3B).45, 46, 47, 48, 49

Figure 3.

Raman Microscopy Spectra

(A) Single Raman spectra of nucleus, cytoplasm, and intracellular lipid droplets in MDA-MB-231 cells. (B) Raman spectra of lipid droplets, SQGem NPs, and 2H-SQGem NPs. The region of interest is highlighted.

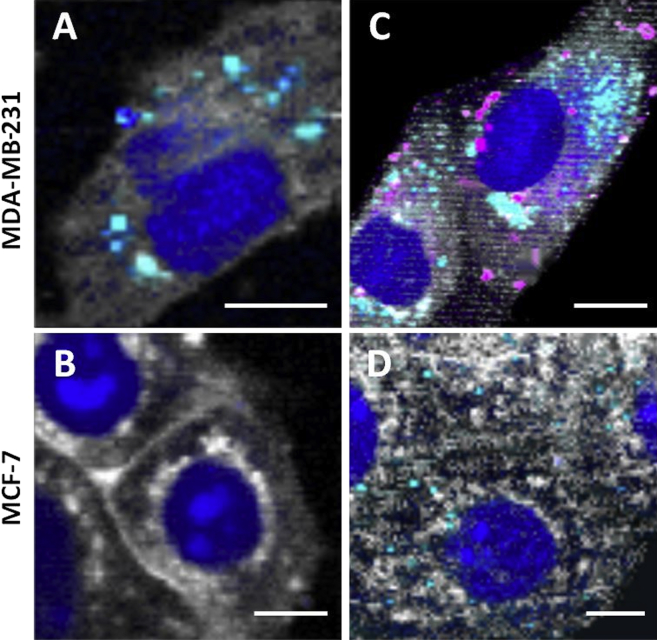

Confocal Raman microscopy images of both cell lines prior to NP incubation (control experiments) revealed that MDA-MB-231 cells were much more abundant in intracellular lipid droplets (cyan spots) than MCF-7 cells, thus indicating a difference in the lipid metabolism between the two cell lines (Figures 4A and 4B). Interestingly, these observations were in accordance with previous reports about the high lipid-accumulating character of MDA-MB-231 cells.50 After 2 hr incubation with 2H-SQGem NPs, a significant intracellular accumulation was observed in MDA-MB-231 cells (pink spots in Figure 4), whereas no NPs were detected in MCF-7 cells under the same conditions (Figures 4C and 4D), probably as a consequence of their lower LDLR expression.

Figure 4.

Confocal Raman Images of MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 Breast Cancer Cell Lines Showing a Comparison of 2H-SQGem NPs Uptake

(A and B) Representative images of non-treated MDA-MB-231 (A) and MCF-7 (B) cells (control). (C and D) MDA-MB-231 (C) and MCF-7 (D) cells incubated with NPs (77 μM) for 2 hr at 37°C. False-color Raman images were generated based on different scattering patterns of different cellular compartments. False colors visualize nucleus in dark blue, cytoplasm in white, lipid vesicles in cyan, and 2H-SQGem in pink. Scale bars, 10 μm.

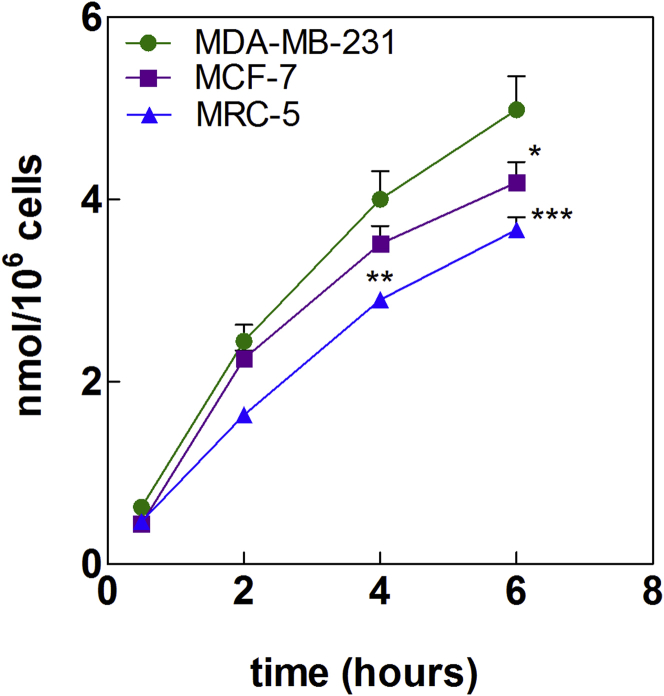

Confocal Raman microscopy observations were confirmed by quantifying the uptake of tritiated SQGem NPs in these two breast cancer cell lines, as well as in MRC-5 fibroblasts chosen as a model of healthy cells with an inferior requirement for LDLs compared with cancer cells. Notably, these fibroblasts, similar to MCF-7 cells, displayed lower expression of LDLRs as compared with the MDA-MB-231 cells.33 Incubation with 3H-SQGem NPs at 37°C resulted in a higher radioactivity signal in MDA-MB-231 cells compared with MCF-7 and MRC-5 cells (Figure 5), thus confirming that a higher LDLR expression induced greater SQGem NP uptake. Such observation was in agreement with the results previously obtained in vivo on MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 tumor-bearing mice fed a high-cholesterol diet in order to increase their level of circulating LDLs. Indeed, in xenografts originating from MDA-MB-231 cells (high LDLR expression), a 2-fold higher radioactivity signal was measured 6 hr post administration of a single dose of 3H-SQGem NPs, compared with MCF-7 (low LDLR expression)-derived tumors.33

Figure 5.

3H-SQGem NPs Uptake in MDA-MB-231, MCF-7, and MCR-5 Cells

Comparison of 3H-SQGem NPs uptake after 30 min, 2 hr, 4 hr, and 6 hr incubation at 37°C. SQGem concentration: 10 μM. Results are expressed as nanomoles of Gem per million of cells. Data represent mean ± SEM (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001).

It has to be noted that, unlike the MCF-7 cells, the MDA-MB-231 cells satisfy their cholesterol needs mainly via uptake of circulating LDL particles, rather than by de novo cholesterol synthesis.50, 51 Such dependence on the LDL uptake was also supported by previous observations that human LDLs significantly increased the proliferation of the MDA-MB 231 cells52 but not of the MCF-7 cells, in a dose-dependent manner.53 Altogether, these data suggest that the specific metabolism of MDA-MB-231 cells may account for their higher uptake of SQGem NPs.

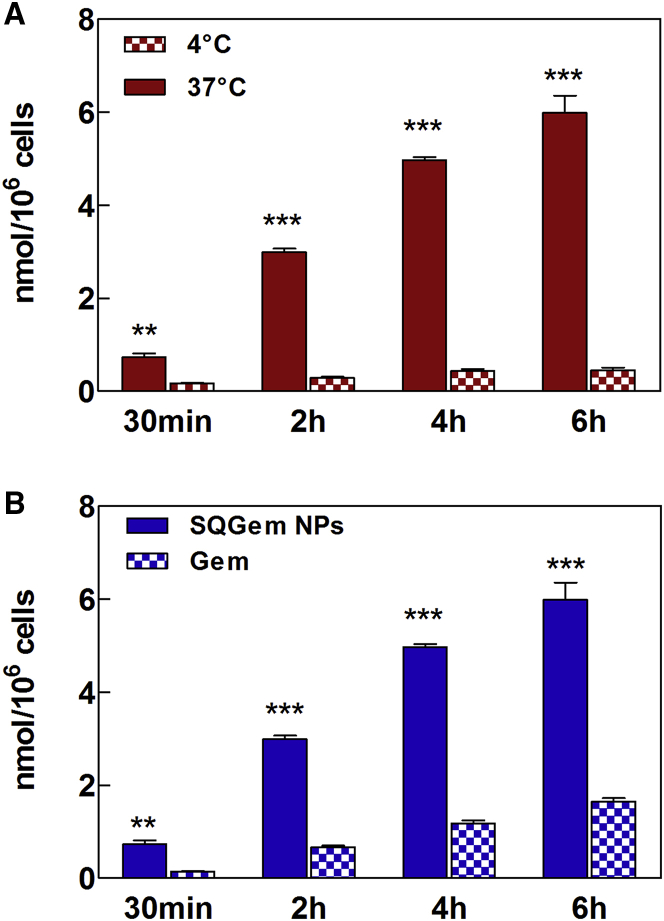

Additional studies have been performed on the MDA-MB-231 cell line by measuring the cell uptake of radiolabeled 3H-SQGem NPs versus 3H-Gem after 30 min, 2 hr, 4 hr, and 6 hr of incubation at 4°C and 37°C. The significantly higher uptake at 37°C, compared with 4°C (Figure 6A), clearly demonstrated that the cell capture of SQGem NPs was mainly obtained via an energy-dependent mechanism, which corroborated the hypothesis of a strong implication of LDLRs in nanoparticle uptake. Noteworthy is that the cell uptake of SQGem NPs was significantly higher compared with free Gem (Figure 6B), thus indicating that the cell internalization of this compound is rather mediated by transporters other than the LDLRs (e.g., nucleoside transporters).54

Figure 6.

Uptake of 3H-SQGem NPs and 3H-Gem in the MDA-MB-231 Cell Line

(A) Comparison of 3H-SQGem NPs (10 μM) uptake at 37°C and 4°C. (B) Comparison of 3H-SQGem NPs (10 μM) and 3H-Gem (10 μM) uptake at 37°C. Results are expressed as nanomoles of Gem per million cells. Bars represent mean ± SEM (**p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; n = 3).

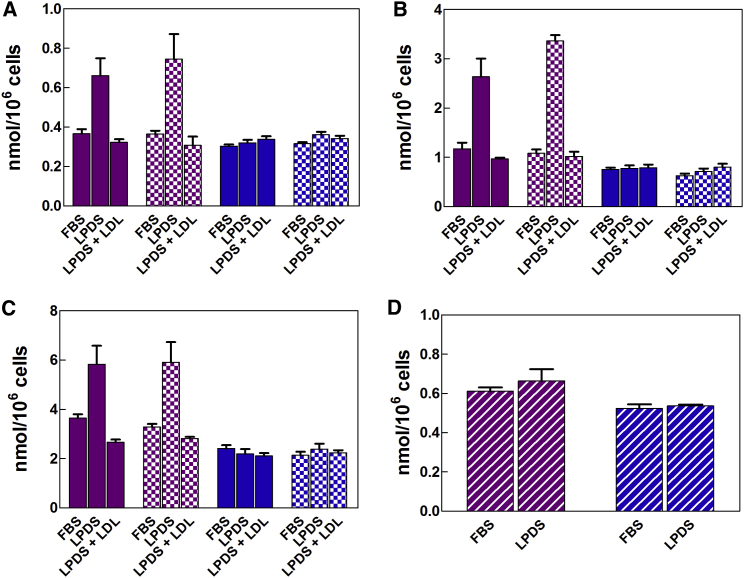

Influence of LDLR Activity and Expression on the Uptake in MDA-MB-231 Cells

Expression and availability of LDLRs on MDA-MB-231 cells have been tuned in order to further elucidate the involvement of LDLRs in the energy-dependent cell uptake of SQGem NPs. Because LDLs are the main source of exogenous cholesterol for the cell, the expression of LDLRs is normally regulated by the cellular demand of cholesterol.55 Hence cholesterol-deprived cells cultivated in medium supplemented with lipoprotein (LP)-deficient serum (LPDS) would have an increased activity of LDLRs, whereas pre-saturation with an excess of LDLs would block the number of available LDLRs. Thus, the higher expression of LDLRs of MDA-MB-231 cells cultivated in a medium deficient in lipoproteins (LPDS-supplemented medium) has been confirmed by western blotting (Figure S1).

LDLR modifications clearly affected the cell uptake of 3H-SQGem NPs. At any time point, the cell starvation with LPDS significantly increased 3H-SQGem NPs cell uptake, whereas a competition with an excess of LDLs resulted in 2- to 3-fold reduction in the measured intracellular radioactivity signal (Figures 7A–7C, solid purple bars). In this study, SQGem NPs were diluted to the desired concentration with fetal bovine serum (FBS)-supplemented culture medium and incubated (30 min, 37°C) before addition to the cells, in order to allow the interaction between the SQGem bioconjugates and LPs present in the serum. These data confirmed the ability of LDL particles to mediate the SQGem NPs cellular uptake via the LDLRs. On the contrary, the uptake of free Gem remained unchanged regardless of the modification of LDLRs (Figures 7A–7C, solid blue bars), which was in agreement with the lack of interactions between free Gem and lipoproteins.33 However, whether SQGem NPs could be cell-internalized via the LDLR without requiring the intervention of LDLs as intermediate carriers deserved to be further investigated. Thus, in order to investigate the capture of 3H-SQGem NPs by MDA-MB-231 cells in the absence of any interaction between nanoparticles and lipoproteins, we performed an additional set of experiments according to the already used experimental conditions, except that SQGem NPs were diluted and preincubated with LPDS-supplemented medium, instead of FBS. Surprisingly, the cell uptake of 3H-SQGem NPs (Figures 7A–7C, square pattern purple bars) was similar to that of nanoparticles preincubated with FBS-supplemented medium. On the other hand, the uptake of the free Gem was not affected by any of the experimental conditions (Figures 7A–7C, square pattern blue bars). Although these results suggested that the interaction of 3H-SQGem NPs with LDLs was not mandatory for nanoparticle uptake via the LDLRs, it must be considered that the commercial LPDS used in this study contained still up to 5% of residual lipoproteins (as stated by the provider). Thus, it could not be excluded that this residual amount of lipoproteins (although low) might still mediate the cell uptake of the 3H-SQGem NPs. Then, to completely ensure the absence of lipoproteins, a final experiment has been carried out by dilution and preincubation of SQGem NPs with the pure medium. In the total absence of LPs, there were clearly no differences concerning the uptake of 3H-SQGem NPs by cells cultured in FBS- or LPDS-supplemented medium, although the latter overexpressed the LDLRs (Figure 7D, striped purple bars). These results confirmed that the establishment of preliminary interactions between SQ bioconjugates and lipoproteins was necessary to target LDL-accumulating cells such as MDA-MB-231.

Figure 7.

Cell Uptake of 3H-SQGem NPs and 3H-Gem as a Function of LDLR Expression and Availability

(A–C) MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured for 24 hr in medium supplemented with FBS, LPDS, or an excess of LDLs in LPDS-supplemented medium (LPDS + LDL) and then incubated with 3H-SQGem NPs (10 μM) or 3H-Gem (10 μM) for (A) 30 min, (B) 2 hr, or (C) 8 hr. Before addition to cells, 3H-SQGem NPs and 3H-Gem were diluted with FBS-supplemented medium (solid purple or blue bars, respectively) or LPDS-supplemented medium (square pattern purple or blue bars, respectively) and pre-incubated in these media for 30 min at 37°C. (D) MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured for 24 hr in medium supplemented with FBS or LPDS and then incubated with 3H-SQGem NPs (10 μM) (striped purple bars) or 3H-Gem (10 μM) (striped blue bars) for 30 min. Before addition to cells, 3H-SQGem NPs and 3H-Gem were diluted with pure medium and pre-incubated for 30 min at 37°C. Results are expressed as nanomoles of Gem per million cells. Bars represent mean ± SEM.

Influence of the Diet on Circulating LDL Levels in Mice

Whether these results obtained in vitro could be transferred to in vivo animal tumor models deserved further investigation. However, the methodology to be used was not obvious, because important differences exist between the metabolism of lipids in humans and in rodents. In the former, the abundant LDL particle population carries about 75% of plasma cholesterol and represents the main source of cholesterol for peripheral tissues,13 whereas in the latter, because of the lack of cholesteryl ester transfer from HDLs to LDLs and very low-density lipoproteins (VLDLs),56 the amount of circulating plasma LDLs is almost negligible. To examine the role of the interaction of SQGem with LDLs and the LDLR-mediated uptake in vivo on xenografted tumor models, it was necessary to increase the amount of circulating LDLs in mice. Even though this increase could be achieved by simply using a diet with high cholesterol content, mice are known to be very resistant to elevated fat or cholesterol dietary intake and their response is highly strain dependent.57 Accordingly, we have investigated the effect of a diet with high cholesterol content (2%) on three different immunodeficient mouse strains (SCID/beige, SCID/BALB/c, and Athymic nude) and compared the level of circulating LDLs with that of mice fed a chow diet with standard cholesterol (SC) content (<0.3%). Of note, the immunodeficient character was necessary to make these strains suitable for the development of human experimental tumors. The C57BL/6 strain was used as positive control because of its known sensitivity to a high-cholesterol diet.58 Among the immunodeficient mice, only the athymic nude ones showed a clear increase (more than 2-fold) in LDL/VLDL circulating cholesterol level after 4 weeks on an high cholesterol diet (Figure S2). Accordingly, this strain was chosen for further studies.

In Vivo Anticancer Activity of SQGem NPs on MDA-MB-231 Tumor-Bearing Mice

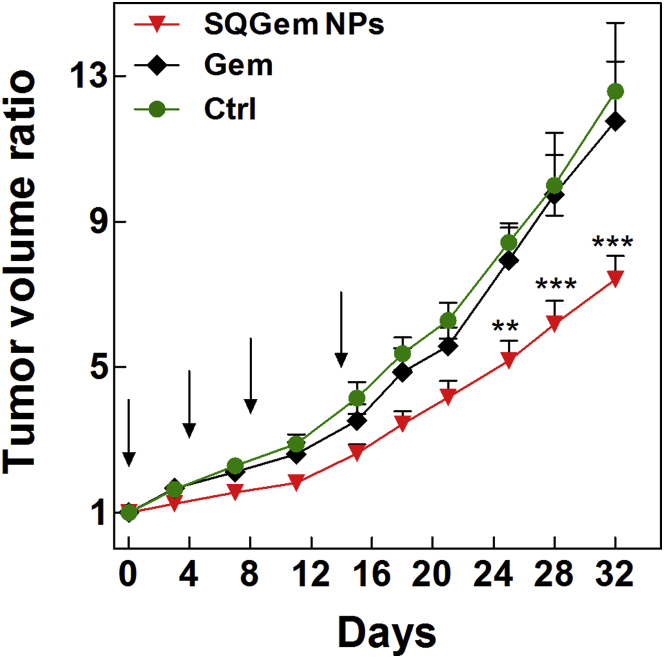

Finally, we have investigated whether the SQGem/LDL interaction and the LDLR-mediated uptake could translate into increased in vivo anticancer activity on MDA-MB-231 tumor-bearing athymic mice fed a high cholesterol diet. This dietary intake started 4 weeks before tumor induction. When tumors reached a volume of 100 mm3, mice were injected intravenously (days 0, 4, 8, and 14) with either SQGem NPs (10 mg/kg eq. Gem) or free Gem (10 mg/kg). Dextrose-treated mice were used as a control. Tumor growth was not affected by the treatment with the free Gem and overlapped the tumor progression in the control group. On the contrary, SQGem NPs induced a reduction in tumor volume ratio by 48% and 39% compared with dextrose and free Gem, respectively (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Tumor Growth Inhibition in MDA-MB-231 Tumor-Bearing Mice

All groups received four intravenous injections on days 0, 4, 8, and 14 in the lateral tail vein of: (1) SQGem NPs (10 mg/kg equivalent Gem), (2) Gem (10 mg/kg), or (3) dextrose 5% (control [Ctrl]). Tumor volume was regularly measured during the experimental period. The values represent mean ± SEM (n = 6). After 25 days, statistical analysis of tumor volume ratios showed superior antitumor efficacy of SQGem NPs compared with the other treatments (**p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001). Arrows point to treatment days.

The superior in vivo anticancer activity of SQGem NPs over the free Gem is in agreement with the in vitro cytotoxicity results that showed that SQGem NPs inhibited the MDA-MB-231 cell growth at concentrations lower than did the free drug (Figure 2D). In vitro, IC50 values also indicated a low sensitivity of this cell line to Gem, herein confirmed by the absence of any inhibitory effect of the free drug on the tumor progression. Nevertheless, in spite of this low inherent sensitivity to Gem, a significantly slower tumor growth was obtained when Gem was delivered in the form of SQ-based nanoparticles, probably as a consequence of the different mechanism of uptake and subsequent intracellular drug release. The obtained results clearly indicated the possibility that endogenous LDL particles can assist the targeting of the squalenoylated Gem toward the high LDLR-expressing MDA-MB-231 cells.

The high tendency of this tumor to accumulate LDL particles was confirmed by the dosage of the circulating LDL-cholesterol before and after the tumor induction. Indeed, even though the 4-week high cholesterol dietary intake resulted in a 2-fold increase in circulating LDL-cholesterol level, a significant reduction was measured 2 weeks after the grafting of the tumor cells (Figure S3), a trend that was not observed in healthy high cholesterol content diet-fed mice under the same experimental conditions, but without the tumor grafting. This observation is in accordance with numerous epidemiological studies that revealed a correlation between the reduction in circulating LDL level and cancer progression.

Conclusions

This study highlights that the strong affinity of SQ-Gem nanoparticles for circulating LDL confers an indirect targeting capability toward cancer cells with LDL-accumulating character, which results in significant anticancer efficacy, even in tumors with a low sensitivity to Gem. Although Gem is not the first-line treatment for breast cancer, the MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell line used in this study enabled us to provide proof of concept of the feasibility of this “indirect” drug-targeting approach. Notably, it simply relies on spontaneous intravascular events and thus allows for overcoming the industrial hurdles in terms of isolation of human LDLs or synthesis of LDL-like particles. Importantly, we have previously demonstrated that the interaction with lipoproteins is not exclusive of SQGem but represents a more general concept common to different SQ derivatives. Accordingly, it opens an entirely new perspective, which may significantly advance the application of LDLs in drug delivery. Obviously, any clinical application would require taking into account the individual lipoprotein profile of each patient.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Gem hydrochloride was obtained from Sequoia Research Products, and 4-(N)-trisnorsqualenoyl-Gem (SQGem) was synthesized as previously reported.34 3H-Gem hydrochloride was obtained from Moravek Biochemicals, whereas 3H-SQGem and 2H-SQGem were synthesized as described elsewhere.33, 37 Dexamethasone disodium phosphate was purchased from Fagron. Dextrose and cell culture media were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. LDLs from human plasma were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Bidistilled MilliQ water was produced using a water purification system (Millipore).

Preparation and Characterization of SQGem Nanoparticles

SQGem nanoparticles (NPs) were prepared according to the nanoprecipitation technique. In brief, SQGem was dissolved in ethanol (2, 4, or 8 mg/mL) and then added drop by drop under magnetic stirring into 1 mL of MilliQ water (ethanol/water 0.5/1 v/v). Formation of NPs occurred spontaneously without addition of any surfactant. After solvent evaporation under reduced pressure, an aqueous suspension of SQGem NPs was obtained (final SQGem concentration 1, 2, or 4 mg/mL). For in vivo experiments, dextrose (5% w/v) was added to the final formulation. Mean particle size and polydispersity index were systematically determined after preparation by quasi-elastic light scattering at 25°C using a Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern Instrument). For deuterated and radiolabeled NPs, the deuterated (2H-SQGem) or the tritiated bioconjugates (3H-SQGem) were added into the ethanolic SQGem solution, and nanoparticles were then prepared as described above. Volume activity of radiolabeled NPs was 15.48 μCi/mL.

Cell Lines and Culture Conditions

Healthy human lung fibroblasts (MRC-5) and four human cancer cell lines (breast basal epithelial cells [MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7], ovarian adenocarcinoma cells [SK-OV-3], and adenocarcinoma alveolar basal epithelial cells [A-549]) were obtained from ATCC and maintained as recommended. In brief, MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured in Leibovitz’s L15 medium supplemented with 15% (v/v) FBS, glutamine (2 mM), and sodium hydrogen carbonate (20 mM). MCF-7 cells were grown in DMEM/Nutrient Mixture F-12 (DMEM-F12) supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated (56°C, 30 min) FBS. SK-OV-3, A-549, and MRC-5 cells were cultured in McCoy’s 5A, RPMI 1640, and Eagle’s minimal essential medium (EMEM), respectively, supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS. Penicillin (50 U/mL) and streptomycin (50 U/mL) (Lonza) were added to all media. Cells were maintained in a humid atmosphere at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Cytotoxicity Assay

Cytotoxicity studies were performed using the MTT test. 100 μL of cell dispersion (3 × 104, 5 × 104, 5 × 104, and 1 × 105 cells/mL for A-549, SK-OV-3, MCF-7, and MDA-MB-231, respectively) was seeded in 96-well plates 24 hr before the treatment with serial dilutions of SQGem NPs or free Gem in culture media. After 72 hr incubation, 20 μL of a 5 mg/mL MTT (Sigma-Aldrich) solution in PBS was added to each well for 2 hr. Then, culture medium was removed and formazan crystals were dissolved in 200 μL of DMSO. Spectrophotometric measurements of the solubilized dye absorbance were performed on a microplate reader (LAB System Original Multiscan MS) at 570 nm. The cell viability for each treatment was calculated according to the ratio of the absorbance of the well containing treated cells versus the average absorbance of control wells (i.e., untreated cells). All experiments were repeated at least three times.

Role of Culture Medium on LDLR Expression

MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured for 24 hr in FBS or LPDS-supplemented medium. Then, cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with a phosphatases- and proteases-inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich), vortexed, and centrifuged (15 min, 11,000 × g, 4°C). The concentration of extracted proteins was then measured using a colorimetric assay (Pierce BCA Protein Assay kit; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Equal amounts (30 μg) of proteins were incubated for 5 min at 99°C with Laemmli sample buffer supplemented with 5% β-mercaptoethanol (Bio-Rad) and then separated on SDS-polyacrylamide gels (Mini-Protean-TGX 4−15%; Bio-Rad). Separated proteins were further transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane using a liquid transfer system (100 V, 45 min). After the blockage (5% dry milk suspension in 0.1% Tween 20 in Tris-buffered saline [TBS]), the membrane was first incubated for 2 hr at room temperature followed by an overnight incubation at 4°C with the primary antibody solution. The membrane was then washed 3 × 15 min in 0.1% Tween 20-TBS buffer and incubated for 1 hr with the secondary antibody solution. The following antibodies have been used in this study: rabbit monoclonal anti-LDLR antibody diluted 1/5,000 (ab52818; Abcam), mouse anti-β-actin antibody diluted 1/2,000 (AC-40; Sigma-Aldrich), goat anti-mouse secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase diluted 1/4,000 (sc-2005; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase diluted 1/10,000 (sc-2004; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Detection of chemiluminescence was performed using the Clarity Western ECL substrate (Bio-Rad Laboratories), and images were captured by the ChemiBIS system from DNR Bioimaging Systems.

Visualization of the Cellular Uptake and Intracellular Localization by Confocal Raman Microscopy

Cellular uptake of deuterated squalenoyl nanoparticles (2H-SQGem NPs) was performed using a confocal Raman microscope (WITec alpha 300R+; WITec). The excitation source was a 532 nm diode laser adjusted to a power of 30 mW and a 50 μm confocal pinhole rejecting signals from out-of-focus regions. A 63× immersion objective with an N.A. of 1.0 (Epiplan Neofluar; Zeiss) was applied for cellular uptake studies. A total of 50,000 cells/well (MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7) were seeded on calcium fluoride well plates 24 hr prior to the incubation with freshly prepared 2H-SQGem NPs, opportunely diluted in cell culture medium, for 2 hr (final Gem concentration: 77 μM/well) at 37°C. At the end of the incubation period, cells were washed with phosphate buffer and fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde solution (30 min, at room temperature) prior to imaging. All acquired Raman spectral datasets were preprocessed by removing cosmic rays and by background signal reduction. Then, false-color Raman images were generated according to the different scattering patterns (unique Raman peaks) of the different cellular compartments. Chemometric post-processing of raw spectra is based on hierarchical cluster and basis analysis (WITec Project Plus software).

Evaluation of the Cellular Uptake by Liquid Scintillation Counting

For cellular uptake studies, MDA-MB-231, MCF-7, and MRC-5 cells (250,000 cells/well) were seeded in 12-well plates 24 hr prior to the incubation with 3H-SQGem NPs or free 3H-Gem diluted in culture medium (final Gem concentration/well: 10 μM, 0.1 μCi/mL) for 30 min, 2 hr, 4 hr, and 6 hr at 37°C or 4°C. At the end of the incubation period, cells were washed with 1 mL of PBS and then treated with 0.3 mL of 0.25% trypsin for 5 min at 37°C. The action of trypsin was stopped by adding 1 mL of culture medium, and the cellular suspension was centrifuged (200 × g, 5 min, 4°C), the supernatant discarded, and the cells dispersed in 1 mL of PBS. 10 μL of each cellular suspension was mixed with 10 μL of trypan blue (Sigma-Aldrich) for cell counting. The amount of cell-internalized 3H-SQGem and 3H-Gem was determined using a β-scintillation counter (Beckman Coulter LS6500). In brief, cell suspensions were first solubilized with 1 mL of Soluene-350 (PerkinElmer) at 50°C overnight prior to the addition of 10 mL of Hionic-Fluor scintillation cocktail (PerkinElmer). Finally, samples were vigorously vortexed for 1 min and kept aside for 2 hr prior to the counting.

Modification of the LDLR Activity and Evaluation of Cellular Uptake by Liquid Scintillation Counting and Flow Cytometry

Another set of experiments was performed to assess the influence of LDLR activity and/or expression on NP uptake. In this case, MDA-MB-231 cells (150,000 cells/well) in culture medium supplemented with FBS (control) or in lipoprotein-deficient serum (LPDS) (for LDLR modifications) were seeded in 24-well plates for 24 hr. Then, 3H-SQGem NPs or free 3H-Gem (both previously diluted in FBS or LPDS-supplemented culture medium or pure medium and preincubated for 30 min at 37°C) were added to each well (final Gem concentration: 10 μM, 0.1 μCi/mL). Before the addition of 3H-SQGem NPs or free 3H-Gem preincubated 30 min in pure medium, cells were washed twice with PBS (1 mL) to ensure the complete removal of all serum components. Of note, the time point 30 min only was chosen in experiments in which pure medium has been used to limit the cell stress caused by non-physiological culture conditions.

For competition studies, cells cultured in LPDS-supplemented medium were preliminary incubated (30 min) with an excessive amount of LDLs (100 μg/mL). After 30 min, 2 hr, and 6 hr incubation, media were removed and cells were washed two times with 1% BSA-PBS (1 mL) and one time with PBS (1 mL) and then treated with 0.2 mL of 0.25% trypsin for 5 min at 37°C. The action of trypsin was stopped by adding 0.8 mL of culture medium, the cellular suspension was centrifuged (200 × g, 5 min, 4°C), supernatant was discarded, and cells were dispersed in 1 mL of PBS. 10 μL of the cellular suspension was then mixed with 10 μL of trypan blue (Sigma Aldrich) for cell counting. The amount of internalized 3H-SQGem and 3H-Gem was determined using a β-scintillation counter as previously described.

Animals

Four different strains of 4-week-old female mice (three immunodeficient [SCID BALB/c, SCID beige, and athymic nude] and one immunocompetent [C57BL/6]) were purchased from Envigo Laboratory. Animals were housed in an appropriate animal care facility during the experimental period. The experimental protocols were approved by the Animal Care Committee of the Université Paris-Sud in agreement with the principles of laboratory animal care and legislation in force in France.

Diet Influence

Four mice strains (at least nine mice each) over 4 weeks were fed either: (1) a chow diet containing a standard amount of cholesterol (<0.3%), or (2) a diet rich in cholesterol (2%) (TD.01383, Teklad diets; Envigo). At weeks 0, 2, and 4 after starting the diet intake, blood (0.2 mL) was collected by facial vein bleeding, and plasma was separated by centrifugation (1,300 × g, 15°C, 15 min). LDL/VLDL cholesterol levels in plasma were determined using the Abcam assay kit (ab65390) based on spectrophotometric cholesterol detection, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Mice were monitored regularly for body weight changes and health status.

In Vivo Anticancer Activity

The anticancer efficacy of SQGem NPs was evaluated on MDA-MB-231 tumor-bearing athymic nude mice fed a diet with high cholesterol content (TD.01383, Teklad diets; Envigo). Feeding started 4 weeks prior to tumor cells injection, and the diet was maintained for the entire duration of the experiment. 200 μL of MDA-MB-231 cell suspension in PBS (5 × 106 cells/mice) were injected subcutaneously into the upper portion of the right flank of mice. Tumors were allowed to grow until reaching a volume of ∼100 mm3 before initiating the treatment. Tumor length (a) and width (b) were measured with calipers, and the tumor volume was calculated using the following equation: tumor volume (V) = (a × b2)/2. Tumor-bearing mice were randomly divided into three groups of at least six mice each. On days 0, 4, 8, and 14, mice received in the lateral tail vein four intravenous injections of either: (1) SQGem NPs at Gem equivalent dose of 10 mg/kg, (2) free Gem at 10 mg/kg, or (3) dextrose 5%. A pre-treatment with 5 mg/kg of dexamethasone was performed by intramuscular injection 4 hr before the treatment. Mice were monitored regularly for changes in tumor size, body weight, and health status. Mice were humanely sacrificed on day 32.

In order to evaluate whether tumor development could induce a modification in circulating LDL level, blood (200 µL) was collected from tumor-bearing mice, fed a high cholesterol content diet, by facial vein bleeding at weeks 0 (beginning of the experiment), 4 (after 4 weeks of feeding a cholesterol-rich diet), and 6 (2 weeks after tumor cells injection). As control, two groups of mice (not bearing the tumor) fed either a standard chow diet or a high-cholesterol-content diet were used. Blood samples were centrifuged (1300 × g, 15°C, 15 min), and LDL cholesterol plasma levels were measured using enzymatic essay (Laboratoire CERBA).

Statistical Analysis

All in vitro experiments were performed at least two times in duplicate or triplicate. For the in vivo experiments, each group counted at least six animals. Statistical analysis was performed with the Prism GraphPad 5.0 software. The significance was calculated using a two-way analysis of variance, followed by Bonferroni post-test.

Author Contributions

P.C. and S.M. conceived and designed the research. D.S. designed and performed the nanoparticles preparation, the cellular studies, and the in vivo experiments. D.D. and E.B. developed and performed the SQGem and 2H-SQGem synthesis. G.P. and S.G.-A. developed and performed the radiolabeled compound synthesis. F.C. and M.R. helped with the cellular studies. M.W. and B.V. developed and performed the confocal Raman microscopy studies. P.C., S.M., D.S., D.D., M.W., and B.V. co-wrote the paper. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The research leading these results has received funding from the European Research Council under the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme FP7/2007-2013 Grant Agreement 249835. The CNRS and the French Ministry of Research are also warmly acknowledged for financial support. Dr. Bernard Rousseau is gratefully acknowledged for assistance in the preparation of 3H-SQGem. Hélène Chacun is warmly acknowledged for the technical assistance during all the experiences with radiolabeled materials. Dr. Juliette Vergnaud is warmly acknowledged for the technical assistance during western blot experiments and the fruitful discussion on the results interpretation. The ARC Foundation for the research on cancer is warmly acknowledged for the financial support.

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes Supplemental Materials and Methods and three figures and can be found with this article online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.05.016.

Supplemental Information

References

- 1.Hanahan D., Weinberg R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ho Y.K., Smith R.G., Brown M.S., Goldstein J.L. Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor activity in human acute myelogenous leukemia cells. Blood. 1978;52:1099–1114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Firestone R.A. Low-density lipoprotein as a vehicle for targeting antitumor compounds to cancer cells. Bioconjug. Chem. 1994;5:105–113. doi: 10.1021/bc00026a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vitols S., Gahrton G., Björkholm M., Peterson C. Hypocholesterolaemia in malignancy due to elevated low-density-lipoprotein-receptor activity in tumour cells: evidence from studies in patients with leukaemia. Lancet. 1985;2:1150–1154. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)92679-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Zoughbi W., Huang J., Paramasivan G.S., Till H., Pichler M., Guertl-Lackner B., Hoefler G. Tumor macroenvironment and metabolism. Semin. Oncol. 2014;41:281–295. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siemianowicz K., Gminski J., Stajszczyk M., Wojakowski W., Goss M., Machalski M., Telega A., Brulinski K., Magiera-Molendowska H. Serum total cholesterol and triglycerides levels in patients with lung cancer. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2000;5:201–205. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.5.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Llaverias G., Danilo C., Mercier I., Daumer K., Capozza F., Williams T.M., Sotgia F., Lisanti M.P., Frank P.G. Role of cholesterol in the development and progression of breast cancer. Am. J. Pathol. 2011;178:402–412. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alikhani N., Ferguson R.D., Novosyadlyy R., Gallagher E.J., Scheinman E.J., Yakar S., LeRoith D. Mammary tumor growth and pulmonary metastasis are enhanced in a hyperlipidemic mouse model. Oncogene. 2013;32:961–967. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhuang L., Kim J., Adam R.M., Solomon K.R., Freeman M.R. Cholesterol targeting alters lipid raft composition and cell survival in prostate cancer cells and xenografts. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:959–968. doi: 10.1172/JCI200519935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silvente-Poirot S., Poirot M. Cholesterol metabolism and cancer: the good, the bad and the ugly. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2012;12:673–676. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nelson E.R., Chang C.Y., McDonnell D.P. Cholesterol and breast cancer pathophysiology. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2014;25:649–655. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuzu O.F., Noory M.A., Robertson G.P. The role of cholesterol in cancer. Cancer Res. 2016;76:2063–2070. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown M.S., Goldstein J.L. A receptor-mediated pathway for cholesterol homeostasis. Science. 1986;232:34–47. doi: 10.1126/science.3513311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vitols S., Gahrton G., Ost A., Peterson C. Elevated low density lipoprotein receptor activity in leukemic cells with monocytic differentiation. Blood. 1984;63:1186–1193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vitols S., Angelin B., Ericsson S., Gahrton G., Juliusson G., Masquelier M., Paul C., Peterson C., Rudling M., Söderberg-Reid K. Uptake of low density lipoproteins by human leukemic cells in vivo: relation to plasma lipoprotein levels and possible relevance for selective chemotherapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1990;87:2598–2602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.7.2598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Versluis A.J., van Geel P.J., Oppelaar H., van Berkel T.J., Bijsterbosch M.K. Receptor-mediated uptake of low-density lipoprotein by B16 melanoma cells in vitro and in vivo in mice. Br. J. Cancer. 1996;74:525–532. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rudling M.J., Ståhle L., Peterson C.O., Skoog L. Content of low density lipoprotein receptors in breast cancer tissue related to survival of patients. Br. Med. J. (Clin. Res. Ed.) 1986;292:580–582. doi: 10.1136/bmj.292.6520.580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gal D., Ohashi M., MacDonald P.C., Buchsbaum H.J., Simpson E.R. Low-density lipoprotein as a potential vehicle for chemotherapeutic agents and radionucleotides in the management of gynecologic neoplasms. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1981;139:877–885. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(81)90952-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vitols S. Uptake of low-density lipoprotein by malignant cells—possible therapeutic applications. Cancer Cells. 1991;3:488–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glickson J.D., Lund-Katz S., Zhou R., Choi H., Chen I.-W., Li H., Corbin I., Popov A.V., Cao W., Song L. Lipoprotein nanoplatform for targeted delivery of diagnostic and therapeutic Aagents. In: Liss P., Hansell P., Bruley D.F., editors. Oxygen Transport to Tissue XXX. Springer US; 2009. pp. 227–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Antwerpen R., Gilkey J.C. Cryo-electron microscopy reveals human low density lipoprotein substructure. J. Lipid Res. 1994;35:2223–2231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schumaker V.N., Adams G.H. Circulating lipoproteins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1969;38:113–136. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.38.070169.000553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Samadi-Baboli M., Favre G., Bernadou J., Berg D., Soula G. Comparative study of the incorporation of ellipticine-esters into low density lipoprotein (LDL) and selective cell uptake of drug--LDL complex via the LDL receptor pathway in vitro. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1990;40:203–212. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(90)90679-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koller-Lucae S.K.M., Schott H., Schwendener R.A. Low density lipoprotein and liposome mediated uptake and cytotoxic effect of N4-octadecyl-1-beta-D-arabinofuranosylcytosine in Daudi lymphoma cells. Br. J. Cancer. 1999;80:1542–1549. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vitols S., Söderberg-Reid K., Masquelier M., Sjöström B., Peterson C. Low density lipoprotein for delivery of a water-insoluble alkylating agent to malignant cells. In vitro and in vivo studies of a drug-lipoprotein complex. Br. J. Cancer. 1990;62:724–729. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1990.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Smidt P.C., van Berkel T.J.C. Prolonged serum half-life of antineoplastic drugs by incorporation into the low density lipoprotein. Cancer Res. 1990;50:7476–7482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kader A., Pater A. Loading anticancer drugs into HDL as well as LDL has little affect on properties of complexes and enhances cytotoxicity to human carcinoma cells. J. Control. Release. 2002;80:29–44. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00536-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lacko A.G., Nair M., Prokai L., McConathy W.J. Prospects and challenges of the development of lipoprotein-based formulations for anti-cancer drugs. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2007;4:665–675. doi: 10.1517/17425247.4.6.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rensen P.C.N., de Vrueh R.L.A., Kuiper J., Bijsterbosch M.K., Biessen E.A.L., van Berkel T.J.C. Recombinant lipoproteins: lipoprotein-like lipid particles for drug targeting. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2001;47:251–276. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00109-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ng K.K., Lovell J.F., Zheng G. Lipoprotein-inspired nanoparticles for cancer theranostics. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011;44:1105–1113. doi: 10.1021/ar200017e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lackó A.G., Stewart D.R., McClain R., Prókai L., McConathy W.J. Recent developments and patenting of lipoprotein based formulations. Recent Pat. Drug Deliv. Formul. 2007;1:143–145. doi: 10.2174/187221107780831914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Corbin I.R., Zheng G. Mimicking nature’s nanocarrier: synthetic low-density lipoprotein-like nanoparticles for cancer-drug delivery. Nanomedicine (Lond.) 2007;2:375–380. doi: 10.2217/17435889.2.3.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sobot D., Mura S., Yesylevskyy S.O., Dalbin L., Cayre F., Bort G., Mougin J., Desmaële D., Lepetre-Mouelhi S., Pieters G. Conjugation of squalene to gemcitabine as unique approach exploiting endogenous lipoproteins for drug delivery. Nat. Commun. 2017 doi: 10.1038/ncomms15678. Published online May 30, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Couvreur P., Stella B., Reddy L.H., Hillaireau H., Dubernet C., Desmaële D., Lepêtre-Mouelhi S., Rocco F., Dereuddre-Bosquet N., Clayette P. Squalenoyl nanomedicines as potential therapeutics. Nano Lett. 2006;6:2544–2548. doi: 10.1021/nl061942q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reddy L.H., Dubernet C., Mouelhi S.L., Marque P.E., Desmaele D., Couvreur P. A new nanomedicine of gemcitabine displays enhanced anticancer activity in sensitive and resistant leukemia types. J. Control. Release. 2007;124:20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reddy L.H., Marque P.-E., Dubernet C., Mouelhi S.-L., Desmaële D., Couvreur P. Preclinical toxicology (subacute and acute) and efficacy of a new squalenoyl gemcitabine anticancer nanomedicine. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2008;325:484–490. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.133751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buchy E., Vukosavljevic B., Windbergs M., Sobot D., Dejean C., Mura S., Couvreur P., Desmaële D. Synthesis of a deuterated probe for the confocal Raman microscopy imaging of squalenoyl nanomedicines. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2016;12:1127–1135. doi: 10.3762/bjoc.12.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reddy L.H., Khoury H., Paci A., Deroussent A., Ferreira H., Dubernet C., Declèves X., Besnard M., Chacun H., Lepêtre-Mouelhi S. Squalenoylation favorably modifies the in vivo pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of gemcitabine in mice. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2008;36:1570–1577. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.020735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hui Y.F., Reitz J. Gemcitabine: a cytidine analogue active against solid tumors. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 1997;54:162–170. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/54.2.162. quiz 197–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vitols S., Peterson C., Larsson O., Holm P., Åberg B. Elevated uptake of low density lipoproteins by human lung cancer tissue in vivo. Cancer Res. 1992;52:6244–6247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gueddari N., Favre G., Hachem H., Marek E., Le Gaillard F., Soula G. Evidence for up-regulated low density lipoprotein receptor in human lung adenocarcinoma cell line A549. Biochimie. 1993;75:811–819. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(93)90132-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Filipowska D., Filipowski T., Morelowska B., Kazanowska W., Laudanski T., Lapinjoki S., Akerlund M., Breeze A. Treatment of cancer patients with a low-density-lipoprotein delivery vehicle containing a cytotoxic drug. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 1992;29:396–400. doi: 10.1007/BF00686010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bildstein L., Dubernet C., Marsaud V., Chacun H., Nicolas V., Gueutin C., Sarasin A., Bénech H., Lepêtre-Mouelhi S., Desmaële D., Couvreur P. Transmembrane diffusion of gemcitabine by a nanoparticulate squalenoyl prodrug: an original drug delivery pathway. J. Control. Release. 2010;147:163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.07.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kann B., Offerhaus H.L., Windbergs M., Otto C. Raman microscopy for cellular investigations—From single cell imaging to drug carrier uptake visualization. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2015;89:71–90. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stiebing C., Matthäus C., Krafft C., Keller A.-A., Weber K., Lorkowski S., Popp J. Complexity of fatty acid distribution inside human macrophages on single cell level using Raman micro-spectroscopy. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2014;406:7037–7046. doi: 10.1007/s00216-014-7927-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matthäus C., Krafft C., Dietzek B., Brehm B.R., Lorkowski S., Popp J. Noninvasive imaging of intracellular lipid metabolism in macrophages by Raman microscopy in combination with stable isotopic labeling. Anal. Chem. 2012;84:8549–8556. doi: 10.1021/ac3012347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chernenko T., Sawant R.R., Miljkovic M., Quintero L., Diem M., Torchilin V. Raman microscopy for noninvasive imaging of pharmaceutical nanocarriers: intracellular distribution of cationic liposomes of different composition. Mol. Pharm. 2012;9:930–936. doi: 10.1021/mp200519y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van Manen H.-J., Lenferink A., Otto C. Noninvasive imaging of protein metabolic labeling in single human cells using stable isotopes and Raman microscopy. Anal. Chem. 2008;80:9576–9582. doi: 10.1021/ac801841y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Matthäus C., Kale A., Chernenko T., Torchilin V., Diem M. New ways of imaging uptake and intracellular fate of liposomal drug carrier systems inside individual cells, based on Raman microscopy. Mol. Pharm. 2008;5:287–293. doi: 10.1021/mp7001158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Antalis C.J., Arnold T., Rasool T., Lee B., Buhman K.K., Siddiqui R.A. High ACAT1 expression in estrogen receptor negative basal-like breast cancer cells is associated with LDL-induced proliferation. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2010;122:661–670. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0594-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Antalis C.J., Uchida A., Buhman K.K., Siddiqui R.A. Migration of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells depends on the availability of exogenous lipids and cholesterol esterification. Clin. Exp. Metastasis. 2011;28:733–741. doi: 10.1007/s10585-011-9405-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rodrigues dos Santos C.R., Domingues G., Matias I., Matos J., Fonseca I., de Almeida J.M., Dias S. LDL-cholesterol signaling induces breast cancer proliferation and invasion. Lipids Health Dis. 2014;13:16. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-13-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rotheneder M., Kostner G.M. Effects of low- and high-density lipoproteins on the proliferation of human breast cancer cells in vitro: differences between hormone-dependent and hormone-independent cell lines. Int. J. Cancer. 1989;43:875–879. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910430523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Damaraju V.L., Damaraju S., Young J.D., Baldwin S.A., Mackey J., Sawyer M.B., Cass C.E. Nucleoside anticancer drugs: the role of nucleoside transporters in resistance to cancer chemotherapy. Oncogene. 2003;22:7524–7536. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ho Y.K., Brown S., Bilheimer D.W., Goldstein J.L. Regulation of low density lipoprotein receptor activity in freshly isolated human lymphocytes. J. Clin. Invest. 1976;58:1465–1474. doi: 10.1172/JCI108603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Camus M.C., Chapman M.J., Forgez P., Laplaud P.M. Distribution and characterization of the serum lipoproteins and apoproteins in the mouse, Mus musculus. J. Lipid Res. 1983;24:1210–1228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nishina P.M., Wang J., Toyofuku W., Kuypers F.A., Ishida B.Y., Paigen B. Atherosclerosis and plasma and liver lipids in nine inbred strains of mice. Lipids. 1993;28:599–605. doi: 10.1007/BF02536053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Paigen B., Morrow A., Brandon C., Mitchell D., Holmes P. Variation in susceptibility to atherosclerosis among inbred strains of mice. Atherosclerosis. 1985;57:65–73. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(85)90138-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.