Abstract

Balanced chromosomal rearrangements (BCR) are associated with abnormal phenotypes in approximately 6% of balanced translocations and 9.4% of balanced inversions. Abnormal phenotypes can be caused by disruption of genes at the breakpoints, deletions, or positional effects. Conventional cytogenetic techniques have a limited resolution and do not enable a thorough genetic investigation. Molecular techniques applied to BCR carriers can contribute to the characterization of this type of chromosomal rearrangement and to the phenotype-genotype correlation. Fifteen individuals among 35 with abnormal phenotypes and BCR were selected for further investigation by molecular techniques. Chromosomal rearrangements involved 11 reciprocal translocations, 3 inversions, and 1 balanced insertion. Array genomic hybridization (AGH) was performed and genomic imbalances were detected in 20% of the cases, 1 at a rearrangement breakpoint and 2 further breakpoints in other chromosomes. Alterations were further confirmed by FISH and associated with the phenotype of the carriers. In the analyzed cases not showing genomic imbalances by AGH, next-generation sequencing (NGS), using whole genome libraries, prepared following the Illumina TruSeq DNA PCR-Free protocol (Illumina®) and then sequenced on an Illumina HiSEQ 2000 as 150-bp paired-end reads, was done. The NGS results suggested breakpoints in 7 cases that were similar or near those estimated by karyotyping. The genes overlapping 6 breakpoint regions were analyzed. Follow-up of BCR carriers would improve the knowledge about these chromosomal rearrangements and their consequences.

Keywords: Abnormal phenotypes, Balanced chromosomal rearrangements, Microarray, Next-generation sequencing

Human genomic architecture is complex and susceptible to chromosomal rearrangements since several mechanisms may occur particularly in regions of low-copy repeats and repetitive sequences [Höckner et al., 2012]. An Italian study with 88,965 amniocentesis samples detected 1,607 chromosomal abnormalities, including numeric and structural rearrangements. Among balanced chromosomal rearrangements (BCR), the frequency was estimated about 1/560 for reciprocal translocations and 1/1,100 for inversions [Forabosco et al., 2009].

Most of the BCR carriers do not present with an abnormal phenotype, although it may be present in approximately 6% of balanced translocations and 9.4% of balanced inversions [Warburton, 1991]. On the other hand, unbalanced chromosomal rearrangements are known to be the cause of syndromes, multiple congenital anomalies, and/or intellectual disability [Shinawi and Cheung, 2008].

Microarray based studies reported copy number variations (microdeletions or microduplications) at the breakpoint(s) of BCR and at other genomic regions far from the breakpoints [Gribble et al., 2005; De Gregori et al., 2007; Baptista et al., 2008; Schluth-Bolard et al., 2009; Fonseca et al., 2013]. These alterations elucidated the abnormal phenotype in 30–50% of the carriers.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) technology has also been applied to delineate BCR breakpoints, which allowed the observation of other mechanisms such as gene disruption, base pair insertions or deletions [Chen et al., 2008, 2010; Slade et al., 2010; Feldman et al., 2011; Sobreira et al., 2011; Talkowski et al., 2011]. As a result, gene expression may be disturbed either by gene inactivation [Kalscheuer et al., 2003; Schluth-Bolard et al., 2013] or a position effect such as dissociating genes from their regulatory elements [Fantes et al., 1995; Krebs et al., 1997; Kleinjan and van Heyningen, 1998, 2005].

In order to investigate genomic imbalances associated with abnormal phenotypes, high-resolution molecular technologies were applied to study a group of individuals with different types of BCR.

Patients

Fifteen individuals with abnormal phenotypes and BCR were selected for further investigation by molecular techniques. The chromosomal rearrangements comprised 11 reciprocal translocations, 3 inversions, and 1 balanced insertion (Table 1). The phenotypes were variable and characterized mainly by intellectual disabilities, facial dysmorphisms, developmental delay, and fertility problems.

Table 1.

Karyotype and phenotype of BCR carriers

| ID | Sex | Age | Karyotype | Origin | Main features | Anthropometrical measurements | Clinical findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 4 ys | 46,XX,ins(9;15)(q32;q12q21) | maternal | intellectual disability, developmental delay, speech delay, behavior problems | weight: 13.4 kg (3<P<10) height: 102.1 cm (50<P<75) OFC: 45 cm (–2 DP>P) | macrocephaly, upslanting palpebral fissures, bulbous nasal tip, flat foot |

| 2 | M | 20 mo | 46,XY,t(3;7)(p12;p15),t(15;18) (q26;q21) |

de novo | motor and mental delay | weight: 7,555 g (P25>P) height: 74 cm (P25>P) OFC: 47.5 cm (P50) |

hypotonia, relative macrocephaly, prominent occiput, high forehead, upslanting palpebral fissures, depressed nasal bridge, increased gap between halluces and 2nd toes |

| 3 | M | 7 ys | 46,XY,t(1;4)(q31;q35) | de novo | intellectual disability, developmental delay, behavior problems | weight: 27.4 kg (P90) height: 125 cm (P50) OFC: 54 cm (50<P<+2 DP) |

flat face, nose with low nasal bridge and root, clinodactyly |

| 4 | M | 26 ys | 46,XY,t(6;13)(p12;p13) | de novo | azoospermia | weight: 62.2 kg (25<P<50) height: 176 cm (P50) OFC: not recorded |

no dysmorphisms |

| 5 | F | 11 ys | 46,XX,inv(7)(p13q32) | maternal | learning disabilities | weight: 43 kg (P75) height: 138.8 cm (P50) OFC: 49 cm (P<–2 SD) |

flat occiput, low back hairline, mild facial and ocular asymmetry, mild synophyrs, high palate, enlargement of distal phalanges of the hands |

| 6 | F | 7 ys | 46,XX,t(2;4)(q21;q31) | maternal | motor and mental delay during early childhood and short stature | weight: 17.6 kg (P<3) height: 111 cm (P<P3, but according to familial growth potential) OFC: 49 cm (P<P3) |

high frontal and back hairlines, flat face, and flat foot |

| 7 | M | 36 ys | 46,XY,t(3;4)(p21;q27) | unknown | oligospermia | not recorded | multiple femoral osteonecrosis in childhood, psoriasis |

| 8 | M | 18 mo | 46,XX,t(5;7)(q11.2;p15.1) | paternal | intellectual disability, developmental delay, behavior problems | weight: 9,050 g (P<P3) height: 76.5 cm (P3) OFC: 46 cm (–2 DP<P<50) |

upslanting palpebral fissures, flat face, depressed nasal bridge, diastasis recti, umbilical hernia, increased gap between halluces and 2nd toes |

| 9 | F | 6 ys | 46,XX,t(8;13)(q22;q32) | paternal | hypotonia, microcephaly, and short stature | not recorded | short stature, microcephaly, low-set ears with prominent lobes, facial asymmetry, upslanting palpebral fissures, long nose, long and prominent philtrum, microstomia, dental malocclusion, micro- and retrognathia, short neck, wide-spaced nipples, zygodactyly, hypotonia |

| 10 | F | 5 ys | 46,XX,t(9;16)(q34;p11.2) | de novo | motor and mental delay | weight: 19.8 kg (P50) height: 110 cm (P25 – 50) OFC: 49.5 cm (P2–50) |

prominent forehead, rounded and mildly dysmorphic ears, synophyrs, straight eyebrows, epicanthus, upslanting palpebral fissures, convergent strabismus, broad nasal root, long canines, lumbar hyperlordosis, bilateral popliteal fossa, widely separated 1st and 2nd toes with increased plantar creases, clinodactyly of the 4th and 5th toes |

| 11 | M | 11 ys | 46,XY,inv(2)(p12;q11) | paternal | motor and mental delay, dental abnormalities, and functional constipation | weight: 29.9 kg (P25) height: 136 cm (P25) OFC: 52 cm (2<P<50) |

brachycephaly, flat occiput, high frontal hairline, flat face, midface hypoplasia, hypoplastic lobes, epicanthal folds, downslanting palpebral fissures, nose with low nasal bridge and root, wide columella, everted lower lip, macrodontia (upper incisors), micrognathia, pectus carinatum, hypoplasia of 5th fingernail, accessory creases in 3rd–5th fingers, dextroscoliosis |

| 12 | M | 15 ys | 46,XY,inv(7)(p13q32) | maternal | motor and mental delay | IUGR (newborn's weight 1,800 g), current anthropometrical data not recorded | high frontal hairline, long face, malar hypoplasia, synophyrs, upslanting palpebral fissures |

| 13 | M | 11 ys | 46,XX,t(3;16)(p10;p10) | unknown | cleft palate | weight: 29 kg (10<P<10) height: 76.5 cm (P3) OFC: 52.5 cm (P50) |

developmental delay, prominent nasal root, micrognathia, long fingers |

| 14 | M | 5 ys | 45,XY,rob(14;15)(q10;q10) | unknown | developmental delay, interatrial communication and facial dysmorphisms | weight: 58 kg (P>P97) height: 124.6 cm (P>P97) OFC: 53.8 cm (50<P<98) |

low back hairline, high frontal hairline, narrow bifrontal diameter, rounded face, almond-shaped palpebral fissures, strabismus, obesity, acanthosis nigricans |

| 15 | M | 8 ys | 46,XY,t(8;15)(q21.1;q26.1) | de novo | learning disabilities | weight: 49 kg (P>P97) height: 136.5 cm (75<P<90) OFC: 52 cm (P50) |

brachycephaly, low frontal hairline, hypoplastic ala nasi, flat philtrum, fusiform fingers, wide gap between halluces 2nd toes, speech delay, poor fine motor coordination |

BCR, balanced chromosomal rearrangements; F, female; M, male; mo, months; P, percentile; IUGR, intrauterine growth retardation; ys, years.

Methods

The molecular analysis included array genomic hybridization (AGH) and NGS. The AGH technique was performed using Affymetrix Genome-Wide Human SNP Array 6.0 and CytoScan 750K Array (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Data analysis was performed by Genotyping Console v. 3.0.2 (HMM) and Chromosome Analysis Suite (ChAS) software, respectively. The analysis pattern consisted of a minimum of 25 markers for deletion and 50 markers for duplications. Breakpoints of rearrangements were carefully verified to detect genomic imbalances. Comparisons were conducted by patients versus the HapMap control dataset.

NGS was performed by whole genome libraries prepared following the Illumina TruSeq DNA PCR-Free protocol (Illumina®). Final libraries were quantified by Qubit® 2.0 Fluorometer (Invitrogen®), and the fragment size was observed by Agilent Bioanalyzer DNA (Agilent Technologies®). Libraries were then sequenced on an Illumina HiSEQ 2000 as 150-bp paired-end reads. The bioinformatics analysis of sequencing data was based on alignments with the human genome reference sequence hg19/GRCh37. NGS analysis focused on chromosomes involved in the rearrangement. From the alignment, a list of reads (QC>60) not mapped with a nominal distance and orientation from each other was retained: pairs of reads with abnormal orientation for inversions and pairs of reads mapped on different chromosomes for translocations. Only abnormalities supported by at least 4 independent pairs of reads were checked using the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) software. All samples were also analyzed by Delly software [Rausch et al., 2012].

Primer pairs were selected on each side of the breakpoint region delimited by NGS (sequence available on request) for validation by Sanger sequencing. Junction fragments were amplified using the Titanium® Taq DNA Polymerase (Clontech®) following protocols previously established in our laboratory. DNA from an individual without chromosomal rearrangement (normal karyotype) was used as a negative control at amplification reaction. PCR products were verified on 2% agarose gel and were sequenced by the Sanger method. Sequences of junction fragments were aligned to the human genome reference sequence hg19/GRCh37 using BLAT from the UCSC Genome Browser. The UCSC browser also indicates the presence/absence of repetitive elements at the breakpoints [Deininger and Batzer, 1999; Kolomietz et al., 2002]. FISH using BAC clones was also used for validation.

Results

The first AGH screening detected genomic imbalances in 20% of the cases (3 individuals), 1 at the rearrangement breakpoint, and 2 further breakpoints in other chromosomes. In patient 2, with a 46,XY,t(3;7)(q12;p15)t(15;18)(q26;q21) karyotype, AGH analysis showed no evidence of a large-scale loss of genetic material in the 7p15, 15q26, and 18q21 regions. However, a deletion of approximately 5.9 Mb was identified in chromosome 3 involving the 3q11.2q12.1 region (breakpoints: 95,002,156–100,962,239 bp, NCBI Build 36.1/hg18) and a deletion of approximately 7.9 Mb on chromosome 21 involving the 21q11.2q21.1 region (breakpoints: 13,488,061–21,440,115 bp, NCBI Build 36.1/hg18) were detected.

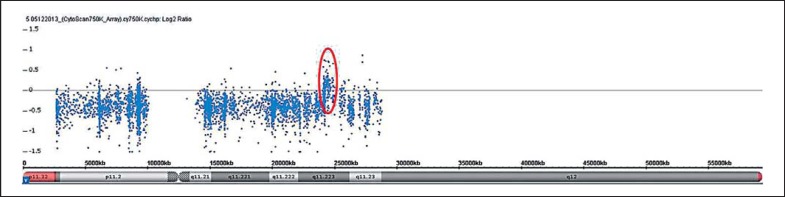

The karyotype of patient 3 was 46,XY,t(1;4)(q31;q35), but no alterations were identified by AGH at the breakpoints of rearrangement, although a deletion of 8 Mb at the 2q32q33.1 region (194,295,389–202,714,175 bp, NCBI Build 36.1/hg18; Fig. 1) was observed. This alteration was further confirmed by FISH (data not shown). Finally, patient 4 was a carrier of a translocation, 46,XY,t(6;13)(p12;p13), and a 968-kb duplication at Yq11.223 (24,017,591–24,985,599, hg19/GRCh37), inherited from his father (Fig. 2).

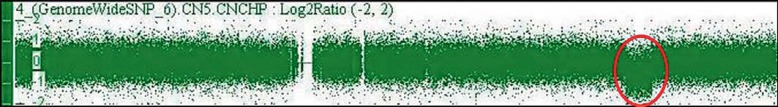

Fig. 1.

AGH profile of chromosome 2. The red circle indicates the deletion of 8 Mb at 2q32.3q33.1.

Fig. 2.

AGH profile of chromosome Y. Weighted log2 ratio plot. The red circle shows a 968-kb copy number gain at the Yq11.223 region.

NGS was viable for further chromosome breakpoint investigations in only 8 cases. Patient 2 and 3 were excluded from this analysis because the AGH technique detected a genomic imbalance with potential pathogenic relevance. The sizes and concentrations of all libraries enabled sequencing by paired-end module, 2 × 150 bp. The total income of the reads was approximately 90 Gb, and the Q30 quality index was above 85%, satisfactory for the type of flow-cell.

After alignment and mapping, analysis of NGS results suggested breakpoints in 7 cases that were similar or near to those estimated by karyotyping. Also, genes and repetitive elements overlapping some breakpoint regions were observed (Table 2). We were unable to find reads spanning breakpoints at 8;13, the junction of patient 9, probably because of a low coverage of these regions due to repetitive elements.

Table 2.

Comparison between breakpoints estimated by karyotyping and NGS: genes and repetitive element overlapping breakpoints of BCR

| ID | Karyotype and array | Readsa | NGS karyotype | Disrupted genes | Repetitive element |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 46,XX,ins(9;15)(q32;q12q21).arr[GRCh37](1–22,X)×2 | 57 | seq[GRCh37] ins(9;15)(q33;q21.1q22.31) g.[chr15:46485297_65811644inschr9:125833639] | RABGAP1 (9q33) | 9q33 and 15q21.1: LINE |

| 4 | 46,XY,t(6;13)(p12;p13).arr[GRCh37] Yq11.223(24017591_24985599)×3 pat | 4 | 46,XY,t(6;13)(p12;p13).seq[GRCh37] t(6;13)(p21.2;?) g.[chr6:pter_38257882::chr13:?cen_qter] | BTBD9 (6p21.2) | no repetitive element |

| 5 | 46,XX,inv(7)(p13;q32).arr[GRCh37](1–22,X)×2 | 7 | seq[GRCh37] inv(7)(pter→ p14.1::q32→ p14.1::q32→qter) g.[41761083_cen_128649294inv] | INHBA (7p14.1) TNPO3 (7q32) | no repetitive element |

| 6 | 46,XX,t(2;4)(q21;q31).arr[GRCh37](1–22,X)×2 | 6 | 46,XX,t(2;4)(q21;q31).seq[GRCh37] t(2;4)(q12;q31) g.[chr2:qter_103503414::chr4:139157500_qter] | SLC7A11 (4q31) | 2q12: LCR |

| 7 | 46,XY,t(3;4)(p21;q27).arr[GRCh37](1–22) ×2,(X,Y)×1 | 26 | 46,XY,t(3;4)(p21;q27).seq[GRCh37] t(3;4)(p23;q28) g.[chr3:pter_30234445::chr4:134843940_qter] | no genes | 4q28: LINE |

| 8 | 46,XX,t(5;7)(q11.2;p15.1).arr[GRCh37](1–22,X)×2 | 17 | 46,XX,t(5;7)(q11.2;p15.1).seq[GRCh37] t(5;7)(q11.2; p14.3) g.[chr5:qter_55777319::chr7:32849621_pter] | AVL9 (7p14.3) | 7p14.3: Tigger3c |

| 10 | 46,XX,t(9;16)(q34;p11.2).arr[GRCh37](1–22,X)×2 | 8 | 46,XX,t(9;16)(q34;p11.2).seq[GRCh37] t(9;16)(q34.3;p12.2) g.[chr9:qter_140545510::chr16:22412564_pter] | EHMT1 (9q34.3) | 9q34.3: SINE 16p12.2: LINE |

BCR, balanced chromosomal rearrangements; LINE, long interspersed nuclear element; LCR, low complexity repeats; NGS, next-generation sequencing; SINE, short interspersed nuclear elements.

Reads spanning breakpoints.

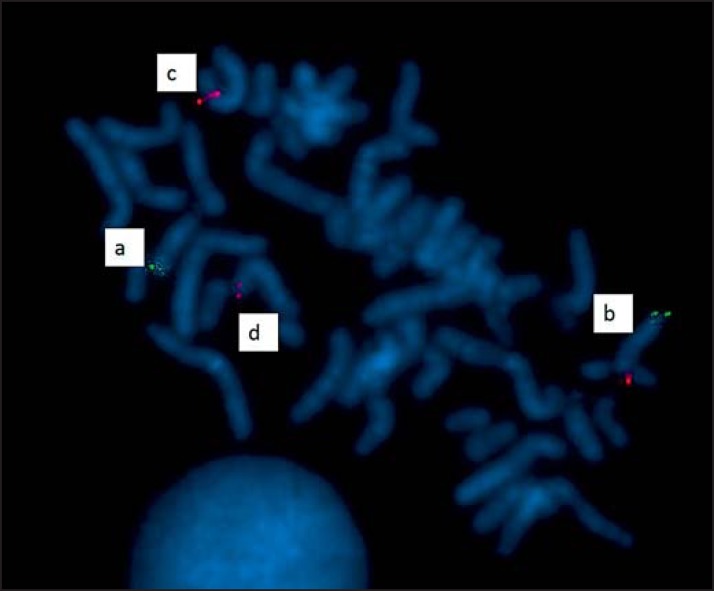

In patient 4, it was not possible to detect reads mapping to chromosome 6 and the corresponding pair mapping to chromosome 13. The short arm of chromosome 13 is heterochromatic and contains various families of repeated DNAs that are very difficult to sequence, as in that of the other acrocentric autosomes 14, 15, 21, and 22. However, at 6p21.2 (38,257,882 hg19) there are 4 reads that the corresponding read pair does not map elsewhere in the genome. It can be suggested that the read pair maps to the centromeric region of chromosome 13 as this region was indicated by karyotyping, and NGS cannot analyze a heterochromatic region. The breakpoint at 6p21.2 was confirmed by FISH (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

FISH analysis on metaphase spreads with BAC RP11–634N14 (6p21.2; 38,169,160–38,378,687 – hg19/GRCh37) labeling in red and a control probe for the 13q region labeling in green. a Normal chromosome 13. b Derivative chromosome 13. c Normal chromosome 6. d Derivative choromosome 6.

Amplification of junction fragments by PCR and further Sanger sequencing was successful only for BCR of patients 7 and 8. The exact breakpoint positions for patient 7 were finally mapped at chr4:134,843,944 and chr3:30,234,445, and for patient 8 at chr5:55,777,306 and chr7:32,849,462. Different methods (FISH and Southern blotting) were proposed to further examine the others cases, but no more samples were available.

Discussion

Compared to multifactorial diseases, a genotype-phenotype correlation is easier to interpret for monogenic conditions. Using cytogenetic techniques, unbalanced chromosome rearrangements usually explain an abnormal phenotype. However, balanced rearrangements are a challenge since there are no detectable chromosome gains or losses visible in the karyotype [Pujol et al., 2006].

A closer look with array techniques allows the elucidation of copy number changes in about 30–50% of the BCR cases [Gribble et al., 2005; De Gregori et al., 2007; Schluth-Bolard et al., 2009]. In our sample, 20% of the patients presented with copy number changes in addition to BCR. Patient 2 is an example of the complex genomic architecture because of the rare presence of 2 reciprocal translocations and 2 partial monosomies. It is rare to find more than 1 single translocation in a person and extremely rare to find more than 2 [Prieto et al., 1978]. This case was previously reported [Simioni et al., 2015].

Patient 3 illustrates the higher probability of BCR carriers having alterations in another region of the genome [Gribble et al., 2005; Higgins et al., 2008]. Beyond the translocation between chromosomes 1 and 4, a deletion of 8 Mb at 2q32.3q33.1 was observed by AGH. Deletions at 2q32.3q33.1 have been reported in patients with a cleft lip and/or palate, Pierre Robin sequence, facial dysmorphisms, ectodermal dysplasia, neurodevelopmental disorder, and mental retardation [Brewer et al., 1999; Houdayer et al., 2001; Loscalzo et al., 2004; Van Buggenhout et al., 2005; Urquhart et al., 2009; Rifai et al., 2010; Balasubramanian, 2011]. There are 35 genes in this region and, among those, the SATB2 (SATB homeobox 2) gene is extremely important. This gene encodes a DNA-binding protein that regulates gene expression through chromatin modification and interaction with other proteins and plays a role in mammalian development [Britanova et al., 2005; Alcamo et al., 2008]. Defects in this gene are associated with an isolated cleft palate, and it is a candidate gene for mental retardation because of its expression in brain structures [Rosenfeld et al., 2009; Balasubramanian et al., 2011]. Despite of the translocation, deletion size, and features related to this chromosomal region, our patient only had neurological abnormalities.

NGS proved to be an efficient method for breakpoint mapping with a high resolution [Chen et al., 2008, 2010; Talkowski et al., 2011]. However, it does not always permit a phenotype correlation in BCR carriers because the breakpoints do not disrupt genes as in patient 7. Breakpoint gene-free areas are likely to be coincidental for the patient's phenotype, or possible to exert a long range position effect [Kleinjan and van Heyningen, 1998]. Breakpoints of patients 1, 6, and 8 disrupted genes are as follows: RABGAP1 (RAB GTPase activating protein 1) is involved in intracellular transport and cellular cycle [Caratù et al., 2007], SLC7A11 (solute carrier family 7) is involved in amino acid transport, and AVL9 (AVL9 homolog – S. cerevisiae) functions at the Golgi complex.

Two genes were disrupted in patient 5: the 7p14.1 region allocates INHBA (inhibin, beta A) with negative cell regulation and the 7q32 region allocates TNPO3 (transportin 3) in which mutations have been reported to cause limb-girdle muscular dystrophy [Melià et al., 2013; Torella et al., 2013]. Generally, muscle weakness affects the pelvis and shoulders with wide intra- and interfamilial variation on progression and severity. The age of onset is also quite variable being between 1–58 years. At present, patient 5 is 23 years old and does not show signs of muscular dystrophy. The breakpoint at the 9q34.3 region disrupted the EHMT1 (euchromatic histone-lysine N-methyltransferase 1) gene in patient 10. The haploinsufficiency of this gene, which encodes chromatin histone methyltransferase-1, has been associated with Kleefstra syndrome [Kleefstra et al., 2005, Kleefstra et al., 2006, 2009]. Features of this syndrome were observed in patient 10 and further studies will be done to improve the genotype-phenotype correlation.

Patient 4 presented with azoospermia and a duplication at Yq11.223 involving part of the AZFb and AZFc regions and 12 genes, including RBMY1, PRY2, and PRY1. There are reports of Yq duplications and azoospermia but also reports of the duplications in fertile men [Giachini et al., 2008; Kuan et al., 2013]. Considering the Yq11.223 duplication was inherited from a normal father, it is not possible to determine the pathogenesis of this duplication and the azoospermic phenotype. Also, NGS detected that the breakpoint at 6p21.2 disrupted the BTBD9 (BTB-domain-containing 9) gene. Polymorphisms in this gene have been reported to be associated with susceptibility to restless legs and Tourette syndromes (OMIM 137580, 611185). Both are neurodevelopmental disorders and azoospermia is not a clinical feature. It could be suggested that meiotic impairment may be the cause of azoospermia in this patient.

This study focused on the investigation of breakpoints in BCR carriers with abnormal phenotypes and was conclusive in 9 cases. Overall, AGH was effective for diagnosis and seems to be an excellent method in breakpoint mapping. In the literature, there are few studies applying NGS to analyze BCR breakpoints. Different methods such as whole genome sequencing, chromosome microdissection together with paired-sequencing and targeted capture [Chen et al., 2008, 2010; Sobreira et al., 2011; Talkowski et al., 2011] have been executed with successful results about BCR breakpoints such as the cases described here. There were technical difficulties to confirm NGS results by Sanger sequencing, probably related to DNA repeat sequences, but different methods could not be performed. In addition, the phenotype of the individuals could not be attributed to the breakpoint exclusively. Even though this article could establish phenotype-genotype correlation in 6 cases, similar studies and follow-up of carriers would improve the knowledge about BCR and its consequences.

Statement of Ethics

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee Board of University of Campinas (# 714/2008 and CAAE 35316314.9.1001.5404). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient's parents or guardians.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patients for participating in this study. We also acknowledge Professor Spencer Luiz Marques Payão, who referred the samples for analysis. This study was supported by the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa (FAPESP) – 2011/23794-7 and 2012/10071-0. V.L.G.-d.-S.-L. is supported by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) – 304455/2012-1.

References

- Alcamo EA, Chirivella L, Dautzenberg M, Dobreva G, Fariñas I, et al. Satb2 regulates callosal projection neuron identity in the developing cerebral cortex. Neuron. 2008;57:364–377. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian M, Smith K, Basel-Vanagaite L, Feingold MF, Brock P, et al. Case series: 2q33.1 microdeletion syndrome-further delineation of the phenotype. J Med Genet. 2011;48:290–298. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2010.084491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baptista J, Mercer C, Prigmore E, Gribble SM, Carter NP, et al. Breakpoint mapping and array CGH in translocations: comparison of a phenotypically normal and an abnormal cohort. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:927–936. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer CM, Leek JP, Green AJ, Holloway S, Bonthron DT, et al. A locus for isolated cleft palate, located on human chromosome 2q32. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65:387–396. doi: 10.1086/302498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britanova O, Akopov S, Lukyanov S, Gruss P, Tarabykin V. Novel transcription factor Satb2 interacts with matrix attachment region DNA elements in a tissue-specific manner and demonstrates cell-type-dependent expression in the developing mouse CNS. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:658–668. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.03897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caratù G, Allegra D, Bimonte M, Schiattarella GG, D'Ambrosio C, et al. Identification of the ligands of protein interaction domains through a functional approach. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6:333–345. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600289-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Kalscheuer V, Tzschach A, Menzel C, Ullmann R, et al. Mapping translocation breakpoints by next-generation sequencing. Genome Res. 2008;18:1143–1149. doi: 10.1101/gr.076166.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Ullmann R, Langnick C, Menzel C, Wotschofsky Z, et al. Breakpoint analysis of balanced chromosome rearrangements by next-generation paired-end sequencing. Eur J Hum Genet. 2010;18:539–543. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2009.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Gregori M, Ciccone R, Magini P, Pramparo T, Gimelli S, et al. Cryptic deletions are a common finding in “balanced” reciprocal and complex chromosome rearrangements: a study of 59 patients. J Med Genet. 2007;44:750–762. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2007.052787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deininger PL, Batzer MA. Alu repeats and human disease. Mol Genet Metab. 1999;67:183–193. doi: 10.1006/mgme.1999.2864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantes J, Redeker B, Breen M, Boyle S, Brown J, et al. Aniridia-associated cytogenetic rearrangements suggest that a position effect may cause the mutant phenotype. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4:415–422. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.3.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman AL, Dogan A, Smith DI, Law ME, Ansell SM, et al. Discovery of recurrent t(6;7)(p25.3;q32.3) translocations in ALK-negative anaplastic large cell lymphomas by massively parallel genomic sequencing. Blood. 2011;117:915–919. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-303305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca AC, Bonaldi A, Costa SS, Freitas MR, Kok F, Vianna-Morgante AM. PLP1 duplication at the breakpoint regions of an apparently balanced t(X;22) translocation causes Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease in a girl. Clin Genet. 2013;83:169–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2012.01854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forabosco A, Percesepe A, Santucci S. Incidence of non-age-dependent chromosomal abnormalities: a population-based study on 88965 amniocenteses. Eu J Hum Genet. 2009;17:897–903. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giachini C, Laface I, Guarducci E, Balercia G, Forti G, Krausz C. Partial AZFc deletions and duplications: clinical correlates in the Italian population. Hum Genet. 2008;124:399–410. doi: 10.1007/s00439-008-0561-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribble SM, Prigmore E, Burford DC, Porter KM, Ng BL, et al. The complex nature of constitutional de novo apparently balanced translocations in patients presenting with abnormal phenotypes. J Med Genet. 2005;42:8–16. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.024141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins AW, Alkuraya FS, Bosco AF, Brown KK, Bruns GA, et al. Characterization of apparently balanced chromosomal rearrangements from the developmental genome anatomy project. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:712–722. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Höckner M, Spreiz A, Frühmesser A, Tzschach A, Dufke A, et al. Parental origin of de novo cytogenetically balanced reciprocal non-Robertsonian translocations. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2012;136:242–245. doi: 10.1159/000337923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houdayer C, Portnoï MF, Vialard F, Soupre V, Crumière C, et al. Pierre Robin sequence and interstitial deletion 2q32.3-q33.2. Am J Med Genet. 2001;102:219–226. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalscheuer VM, Tao J, Donnelly A, Hollway G, Schwinger E, et al. Disruption of the serine/threonine kinase 9 gene causes severe X-linked infantile spasms and mental retardation. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:1401–1411. doi: 10.1086/375538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleefstra T, Smidt M, Banning MJ, Oudakker AR, Van Esch H, et al. Disruption of the gene euchromatin histone methyl transferase1 (Eu-HMTase1) is associated with the 9q34 subtelomeric deletion syndrome. J Med Genet. 2005;42:299–306. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.028464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleefstra T, Brunner HG, Amiel J, Oudakker AR, Nillesen WM, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in euchromatin histone methyl transferase 1 (EHMT1) cause the 9q34 subtelomeric deletion syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79:370–377. doi: 10.1086/505693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleefstra T, van Zelst-Stams WA, Nillesen WM, Cormier-Daire V, Houge G, et al. Further clinical and molecular delineation of the 9q subtelomeric deletion syndrome supports a major contribution of EHMT1 haploinsufficiency to the core phenotype. J Med Genet. 2009;46:598–606. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.062950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinjan DA, van Heyningen V. Long-range control of gene expression: emerging mechanisms and disruption in disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:8–32. doi: 10.1086/426833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinjan DJ, van Heyningen V. Position effect in human genetic disease. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:1611–1618. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.10.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolomietz E, Meyn MS, Pandita A, Squire JA. The role of Alu repeat clusters as mediators of recurrent chromosomal aberrations in tumors. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2002;35:97–112. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs I, Weis I, Hudler M, Rommens JM, Roth H, et al. Translocation breakpoint maps 5 kb 3′ from TWIST in a patient affected with Saethre-Chotzen syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:1079–1086. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.7.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuan LC, Su MT, Kuo PL, Kuo TC. Direct duplication of the Y chromosome with normal phenotype – incidental finding in two cases. Andrologia. 2013;45:140–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.2012.01320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loscalzo ML, Galczynski RL, Hamosh A, Summar M, Chinsky JM, Thomas GH. Interstitial deletion of chromosome 2q32–34 associated with multiple congenital anomalies and a urea cycle defect (CPS I deficiency) Am J Med Genet A. 2004;128A:311–315. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melià MJ, Kubota A, Ortolano S, Vílchez JJ, Gámez J, et al. Limb-girdle muscular dystrophy 1F is caused by a microdeletion in the transportin 3 gene. Brain. 2013;136:1508–1517. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto F, Badia L, Moreno JA, Barbero P, Asensi F. 10p-syndrome associated with multiple chromosomal abnormalities. Hum Genet. 1978;45:229–235. doi: 10.1007/BF00286969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pujol A, Benet J, Staessen C, Van Assche E, Campillo M, et al. The importance of aneuploidy screening in reciprocal translocation carriers. Reproduction. 2006;131:1025–1035. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.01063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rausch T, Zichner T, Schlattl A, Stütz AM, Benes V, Korbel JO. DELLY: structural variant discovery by integrated paired-end and split-read analysis. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:i333–339. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rifai L, Port-Lis M, Tabet AC, Bailleul-Forestier I, Benzacken B, et al. Ectodermal dysplasia-like syndrome with mental retardation due to contiguous gene deletion: further clinical and molecular delineation of del(2q32) syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152A:111–117. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld JA, Ballif BC, Lucas A, Spence EJ, Powell C, et al. Small deletions of SATB2 cause some of the clinical features of the 2q33.1 microdeletion syndrome. PLoS One. 2009;4 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006568. e6568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schluth-Bolard C, Delobel B, Sanlaville D, Boute O, Cuisset JM, et al. Cryptic genomic imbalances in de novo and inherited apparently balanced chromosomal rearrangements: array CGH study of 47 unrelated cases. Eur J Med Genet. 2009;52:291–296. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schluth-Bolard C, Labalme A, Cordier MP, Till M, Nadeau G, et al. Breakpoint mapping by next generation sequencing reveals causative gene disruption in patients carrying apparently balanced chromosome rearrangements with intellectual deficiency and/or congenital malformations. J Med Genet. 2013;50:144–150. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-101351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinawi M, Cheung SW. The array CGH and its clinical applications. Drug Discov Today. 2008;13:760–770. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simioni M, Steiner CE, Gil-da-Silva-Lopes VL. De novo double reciprocal translocations in addition to partial monosomy at another chromosome: a very rare case. Gene. 2015;573:166–170. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2015.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade I, Stephens P, Douglas J, Barker K, Stebbings L, et al. Constitutional translocation breakpoint mapping by genome-wide paired-end sequencing identifies HACE1 as a putative Wilms tumour susceptibility gene. J Med Genet. 2010;47:342–347. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.072983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobreira NL, Gnanakkan V, Walsh M, Marosy B, Wohler E, et al. Characterization of complex chromosomal rearrangements by targeted capture and next-generation sequencing. Genome Res. 2011;21:1720–1727. doi: 10.1101/gr.122986.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talkowski ME, Ernst C, Heilbut A, Chiang C, Hanscom C, et al. Next-generation sequencing strategies enable routine detection of balanced chromosome rearrangements for clinical diagnostics and genetic research. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88:469–481. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torella A, Fanin M, Mutarelli M, Peterle E, Del Vecchio Blanco F, et al. Next-generation sequencing identifies transportin 3 as the causative gene for LGMD1F. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063536. e63536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urquhart J, Black GC, Clayton-Smith J. 4.5 Mb microdeletion in chromosome band 2q33.1 associated with learning disability and cleft palate. Eur J Med Genet. 2009;52:454–457. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Buggenhout G, Van Ravenswaaij-Arts C, Mc Maas N, Thoelen R, Vogels A, et al. The del(2)(q32.2q33) deletion syndrome defined by clinical and molecular characterization of four patients. Eur J Med Genet. 2005;48:276–289. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warburton D. De novo balanced chromosome rearrangements and extra marker chromosomes identified at prenatal diagnosis: clinical significance and distribution of breakpoints. Am J Hum Genet. 1991;49:995–1013. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]