Abstract

BACKGROUND

Surgical site infections (SSIs) remain a major source of morbidity and cost after resection of intra-abdominal malignancies. Negative-pressure wound therapy (NPWT) has been reported to significantly reduce SSIs when applied to the closed laparotomy incision. This article reports the results of a randomized clinical trial examining the effect of NPWT on SSI rates in surgical oncology patients with increased risk for infectious complications.

STUDY DESIGN

From 2012 to 2016, two hundred and sixty-five patients who underwent open resection of intra-abdominal neoplasms were stratified into 3 groups: gastrointestinal (n = 57), pancreas (n = 73), or peritoneal surface (n = 135) malignancy. They were randomized to receive NPWT or standard surgical dressing (SSD) applied to the incision from postoperative days 1 through 4. Primary outcomes of combined incisional (superficial and deep) SSI rates were assessed up to 30 days after surgery.

RESULTS

There were no significant differences in superficial SSIs (12.8% vs 12.9%; p > 0.99) or deep SSI (3.0% vs 3.0%; p > 0.99) rates between the SSD and NPWT groups, respectively. When stratified by type of surgery, there were still no differences in combined incisional SSI rates for gastrointestinal (25% vs 24%; p > 0.99), pancreas (22% vs 22%; p > 0.99), and peritoneal surface malignancy (9% vs 9%; p > 0.99) patients. When performing univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis of demographic and operative factors for the development of combined incisional SSI, the only independent predictors were preoperative albumin (p = 0.0031) and type of operation (p = 0.018).

CONCLUSIONS

Use of NPWT did not significantly reduce incisional SSI rates in patients having open resection of gastrointestinal, pancreatic, or peritoneal surface malignancies. Based on these results, at this time NPWT cannot be recommended as a therapeutic intervention to decrease infectious complications in these patient populations.

Surgical site infections (SSIs) are the most common cause of nosocomial infection, accounting for 38% of all hospital-acquired infections. Although the overall incidence of SSI is low, developing in 2% to 5% of the more than 30 million patients undergoing surgical procedures each year,1–3 the highest rates occur after abdominal surgery. Patients undergoing gastrointestinal and hepatopancreatobiliary surgery are reported to have SSI rates ranging from 8% to 15%.4,5 In addition, patients with cancer who are undergoing surgical procedures have an increased risk of SSIs.6 The impact of SSIs on the health-care system is considerable, resulting in increased morbidity and mortality, prolonged hospital stay, and greater financial costs.7–9 Among patients who die in the postoperative period, death is related directly to SSIs in >75% of cases. Another study found that compared with patients who did not have a postoperative infection, those with SSIs were more than twice as likely to die, 60% more likely to spend time in an ICU, and more than 5 times as likely to be readmitted to the hospital.10

Several approaches to decreasing SSI in patients undergoing gastrointestinal surgery have been advocated in the recent literature. Laparoscopic surgery has been reported to reduce SSIs substantially compared with open surgery, based on an analysis of a large administrative database11 and a systemic review and meta-analysis.12 Also SSI bundles have been reported to decrease SSI rates in gastrointestinal surgery.4,13,14 By implementing a set of interventions across the entire surgical episode of care in a multidisciplinary fashion, the rate of superficial SSIs was reduced significantly. Some authors have advocated the inclusion of negative-pressure wound therapy (NPWT) to SSI bundles, based on preliminary evidence of its efficacy in the prevention of SSIs on closed laparotomy incisions.15

Negative-pressure wound therapy has traditionally been used for complex open wounds in both acute and chronic care settings.16 The device consists of an open-pore poly-urethane foam that is placed in the wound, covered by a semi-occlusive dressing, and connected by a tube to a vacuum source. Originally developed by Argenta and Morykwas in the 1990s,17,18 NPWT has revolutionized the treatment of complex wounds, and is currently used not only in the acute care hospital setting, but also increasingly in nursing facilities, home care settings, and internationally.16 There is a growing body of literature reporting the use of NPWT for closed primary incisions to decrease wound complications19–23 and specifically closed abdominal laparotomy incisions in general surgery patients,24–27 including a retrospective case-control series from our own institution.28 All of these reports suggest NPWT can substantially reduce wound complications and SSIs compared with standard surgical dressing (SSD).

Due to the results of published studies and our own preliminary experience with NPWT for closed laparotomy incisions in high-risk surgical oncology patients, we conducted a phase II randomized clinical trial comparing NPWT with SSD in patients undergoing open resection of gastrointestinal, pancreatic, and peritoneal surface malignancies. Our hypothesis was that NPWT would significantly decrease the incidence of superficial and deep SSIs compared with SSD in surgical oncology patients having abdominal surgery.

METHODS

This study was approved by the Protocol Review Committee of the Wake Forest Baptist Comprehensive Cancer Center and the Wake Forest University Health Sciences IRB. Additional details about the trial can be found at ClinicalTrials.gov (ID: NCT01656044).

Trial design

This was a prospective phase II randomized controlled intervention study assessing differences in SSI rates after using an incisional NPWT dressing compared with a standard postoperative surgical dressing. Patients were stratified by type of surgery (gastrointestinal, pancreatic, or cytoreductive surgery with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy [CRS/HIPEC]). Demographic, perioperative, and outcomes data were prospectively collected. Three hundred and seventy-five patients were consented to the study with 265 patients evaluable for analysis. Patients were enrolled on the study from June 2012 to June 2016.

Participants

Eligibility criteria were as follows: age 18 years or older; scheduled for open surgical procedure, which included laparoscopic-assisted cases (consisting of a hand port resulting in an incision of at least 7.5 cm); surgery for bowel resection (esophagus to rectum), pancreatectomy, or CRS/HIPEC for peritoneal surface malignancy; procedure performed via midline laparotomy; clean-contaminated (class II) case; and ability to understand and willingness to sign written informed consent. Exclusion criteria were emergency cases; pregnant patients; clean (class I), contaminated (class III), and dirty (class IV) procedures; pure laparoscopic cases; chronic immunosuppressive medications, including steroids, within the past 3 months; history of skin allergy to iodine or adhesive drapes; and planned procedure involving foreign material (such as mesh or drains) being left in the subcutaneous space at the time of surgery (eg a ventral hernia repair). Surgical drains that are placed to drain an intra-abdominal space and exit the abdominal wall remote from the incision are allowed in the study. Patients were also excluded from analysis if the planned surgical procedure was not performed, if they underwent reoperation through the original incision within 30 days of the original surgery for a non-wound-related complication, died within 30 days of surgery, or did not have 30-day follow-up for any other reason.

Treatment plan

Enrolled patients were randomized to receive either SSD or NPWT dressing over their closed laparotomy incision at the conclusion of their surgery. After randomization and before the surgery, the study coordinator informed the surgeon which dressing was selected for the patient. Patients’ incisions treated with SSD were closed in the standard fashion. The fascia was closed with a running stitch using looped polydioxanone suture. The subcutaneous tissue was reapproximated with simple, interrupted stitches using absorbable Vicryl suture (Ethicon). The skin was closed with staples spaced 1 to 1.5 cm apart. The incision was dressed with an adhesive Primapore (Smith and Nephew) dressing. If the dressing became soiled and required removal, it was replaced with a new adhesive sterile gauze dressing.

Patients who were randomized to receive NPWT dressing had their fascia closed in the same manner as the SSD patients. Specific details of this technique have been described previously.28 The subcutaneous tissue was closed with simple interrupted stitches spaced 3 to 4 cm apart using absorbable Vicryl suture. The skin was closed with staples spaced 1.5 to 2 cm apart. The subcutaneous tissue and skin were closed loosely in this manner to allow equal distribution of negative pressure and thereby facilitate drainage of subcutaneous edema and blood. A permeable, nonadhesive dressing, such as Adaptic (Johnson & Johnson) was cut to cover the incision. This dressing was used to protect the skin from the foam and facilitate dressing removal, but also allow fluid to drain from the wound. Sterile polyurethane foam was cut into a 2-cm × 2-cm strip of sufficient length to cover the incision. An adhesive drape was used to cover the foam and create an airtight seal. Using evacuation tubing, the dressing was attached to a negative pressure device that was set to deliver 125 mmHg of continuous negative pressure. If the dressing malfunctioned and the seal was lost, repair was attempted. If the dressing had to be redone, it was replaced using new materials. Both SSD and NPWT dressings were removed on postoperative day 4.

Outcomes

The primary end point of the study was to establish the rate of combined incisional SSI in each study arm at 30 days from surgery, which includes superficial and deep SSIs as defined by the CDC29 and is summarized in Table 1. The secondary end point was to determine the rates of organ/space SSI, seromas, hematomas, incisional cellulitis, wound dehiscence, and wound opening for any reason. Wound dehiscence was defined as any spontaneous separation of the skin or fascia not associated with an SSI, seroma, or hematoma. Major morbidity was defined as any grade 3 or 4 serious adverse event as defined by the NIH’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, v4.0.

Table 1.

Surgical Site Infections

| Superficial incisional SSI |

| Infection occurs within 30 days after the operation and infection involves only skin or subcutaneous tissue of the incision and at least 1 of the following: |

| Purulent drainage, with or without laboratory confirmation, from the superficial incision. |

| Organisms isolated from an aseptically obtained culture of fluid or tissue from the superficial incision. |

| At least 1 of the following signs or symptoms of infection: pain or tenderness, localized swelling, redness, or heat, and superficial incision is deliberately opened by surgeon unless incision is culture-negative. |

| Diagnosis of superficial incisional SSI by the surgeon or attending physician. |

| Deep incisional SSI |

| Infection occurs within 30 days after the operation if no implant is left in place or within 1 year if implant is in place and the infection appears to be related to the operation and infection involves deep soft tissues (eg fascial and muscle layers) of the incision and at least 1 of the following: |

| Purulent drainage from the deep incision but not from the organ/space component of the surgical site. |

| A deep incision spontaneously dehisces or is deliberately opened by a surgeon when the patient has at least one of the following signs or symptoms: fever (>38°C), localized pain, or tenderness, unless site is culture-negative. |

| An abscess or other evidence of infection involving the deep incision is found on direct examination, during reoperation, or by histopathologic or radiologic examination. |

| Diagnosis of a deep incisional SSI by a surgeon or attending physician. |

| Notes |

| Report infection that involves both superficial and deep incision sites as deep incisional SSI. |

| Report an organ/space SSI that drains through the incision as a deep incisional SSI. |

| Organ/space SSI |

| Infection occurs within 30 days after the operation if no implant is left in place or within 1 year if implant is in place and the infection appears to be related to the operation and infection involves any part of the anatomy (eg organs or spaces), other than the incision, which was opened or manipulated during an operation and at least 1 of the following: |

| Purulent drainage from a drain that is placed through a stab wound. If the area around a stab wound becomes infected, it is not an SSI. It is considered a skin or soft-tissue infection, depending on its depth into the organ/space. |

| Organisms isolated from an aseptically obtained culture of fluid or tissue in the organ/space. |

| An abscess or other evidence of infection involving the organ/space that is found on direct examination, during reoperation, or by histopathologic or radiologic examination. |

| Diagnosis of an organ/space SSI by a surgeon or attending physician. |

SSI, surgical site infection.

While the patient was in the hospital, the surgical dressing was assessed daily by a study team member. The integrity of the dressing was noted, as well as any soilage of the gauze. The quantity of drainage from the NPWT dressing was measured and recorded. Study team members continued daily assessments of the incision until discharge or up to 30 days after surgery. If the patient was readmitted within 30 days of surgery, daily incision assessments were resumed until the patient was again discharged or until 30 days is reached. These daily assessments were recorded on the daily incision assessment form. Any signs of infection, drainage, or wound breakdown were noted. If a surgical site complication was diagnosed or suspected by the primary surgical team, a study team member was called to assess the incision. If incisional cellulitis was diagnosed, appropriate antibiotics were started. If an incisional SSI was diagnosed, the incision was opened and the wound packed with a wet to dry dressing per discretion of the primary surgical team under the supervision of the attending surgeon. Antibiotics were prescribed as clinically indicated. Other surgical site complications, such as seroma, hematoma, dehiscence and organ/space SSI, were also recorded during the daily assessment. If the incision was opened to drain a seroma or hematoma, or if the incision dehisced spontaneously, the wound was packed with a wet to dry dressing and dressing changes continued as prescribed by the primary surgical team. A study team member assessed the surgical incision at all outpatient clinic visits until 30 days after surgery.

Patients were followed for approximately 30 (+5) days. Patients who were not seen in the clinic between postoperative days 30 and 35 were contacted by a study coordinator via telephone. The patient was asked if they had any problems with the surgical incision or received any incisional care at another facility. This short phone interview ensured that all patients have 30-day follow-up to capture any surgical site complications that occurred after surgery and might have been diagnosed and treated at another facility. The information obtained during this phone interview was recorded on a 30-day postoperative telephone interview form.

Sample size

It was estimated that 264 evaluable patients would be required to test the efficacy of NPWT in preventing incisional SSIs compared with SSD. This sample size estimate was determined using a 2-sided continuity-corrected chi-square test with 90% power and a significance level of 0.05. The proportions were estimated using our previous retrospective data28 in which an incisional SSI developed in 17% of patients undergoing a clean-contaminated surgical procedure treated with SSD compared with 11% in patients treated with NPWT.

Randomization

Patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 allocation scheme using a varying block sizes (of 4, 6, and 8) into 2 groups: those having an SSD after closure of their laparotomy incision and those undergoing NPWT. The research nurse for the clinical trial generated the random allocation sequence, enrolled the participants, and assigned participants to the study interventions. There was no blinding of the patients or care providers to the study intervention. An email was sent the day before surgery to the attending surgeon about to which treatment arm the patient had been assigned.

Statistical methods

Descriptive statistics, including medians and ranges for continuous variables and frequencies and proportions for categorical measures, were calculated for all independent and dependent variables. To compare the demographic, outcomes, and perioperative variables between study arms, independent t-tests were used for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact tests were used for categorical variables. In the case of small sample sizes, such as comparing the units transfused among only those who received transfusions, nonparametric tests (Wilcoxon rank-sum tests) were used. For modeling combined SSIs as an end point, logistic regression models were fit to test for association between independent measures and occurrence of a superficial or deep SSI. Initially, single-variable models were created, and then a multiple-variable model was fit in a stepwise fashion, with the beginning model composed of all variables with a p value <0.05, and variables in the full model removed in a singular fashion until only those variables with p < 0.05 remained.

RESULTS

Demographic and operative data

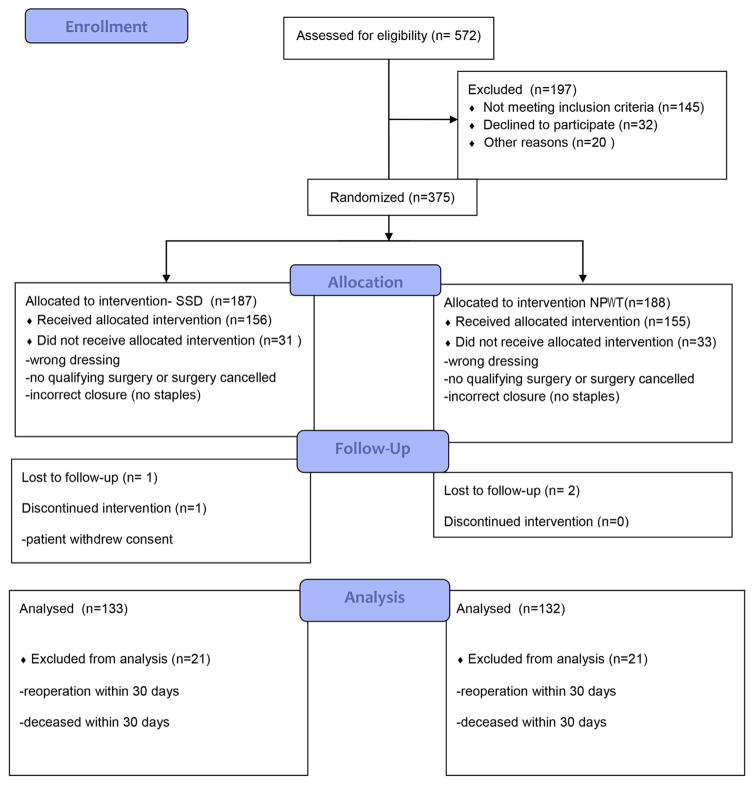

Figure 1 shows participant flow. There were 133 and 132 analyzable patients in the SSD and NPWT study arms, respectively. Overall demographic and factors were not significantly different between the 2 groups, except for the mean units of packed RBCs transfused (Table 2). The incidence of renal failure trended toward a higher rate in the NPWT group. However, this difference did not have any effect on wound outcomes.

Figure 1.

Cohort flow diagram. SSD, standard surgical dressing; NPWT, negative-pressure wound therapy.

Table 2.

Demographics and Operative Data

| Variable | Standard surgical dressing | Negative-pressure wound therapy | p Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||

| Median (range) | n | % | Median (range) | n | % | ||

| Total | 133 | 132 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Age, y | 62 (30–81) | 59.5 (25–85) | 0.27 | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Sex (female) | 64 | 48.1 | 55 | 41.7 | 0.32 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Race | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Black | 10 | 7.6 | 15 | 11.4 | 0.70 | ||

|

| |||||||

| White | 117 | 88.0 | 110 | 83.3 | |||

|

| |||||||

| Other | 4 | 3.0 | 4 | 3.0 | |||

|

| |||||||

| Unknown | 2 | 1.5 | 3 | 2.2 | |||

|

| |||||||

| Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| 0 | 74 | 60.2 | 70 | 57.4 | 0.32 | ||

|

| |||||||

| 1 | 42 | 34.2 | 49 | 40.2 | |||

|

| |||||||

| 2 | 7 | 5.7 | 3 | 2.5 | |||

|

| |||||||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.6 (15.2–49.3) | 28.1 (18.2–52.4) | 0.31 | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Diabetes | 26 | 19.5 | 35 | 26.5 | 0.24 | ||

|

| |||||||

| COPD | 7 | 5.3 | 11 | 8.3 | 0.46 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Renal failure | 2 | 1.5 | 8 | 6.2 | 0.059 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Hypertension | 71 | 53.4 | 72 | 54.6 | 0.90 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Cardiovascular disease | 18 | 13.6 | 22 | 16.7 | 0.61 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Smoking | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Current | 13 | 9.9 | 10 | 7.6 | 0.17 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Former | 46 | 34.8 | 61 | 46.6 | |||

|

| |||||||

| Never | 73 | 55.3 | 60 | 45.8 | |||

|

| |||||||

| Previous abdominal surgery, yes | 92 | 69.2 | 90 | 68.2 | 0.9 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Preoperative chemotherapy, yes | 29 | 22.3 | 36 | 27.5 | 0.39 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Preoperative radiation, yes | 8 | 6.0 | 13 | 9.9 | 0.27 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Preoperative albumin, yes | 4.0 (2.6–4.9) | 4.0 (2.7–5.2) | 0.84 | ||||

|

| |||||||

| American Society of Anesthesiologists class | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| I | 0 | 0 | 0.65 | ||||

|

| |||||||

| II | 15 | 11.3 | 10 | 7.6 | |||

|

| |||||||

| III | 110 | 82.7 | 114 | 86.4 | |||

|

| |||||||

| IV | 8 | 6.0 | 8 | 6.1 | |||

|

| |||||||

| Type of operation | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Gastrointestinal | 28 | 21.0 | 29 | 22.0 | 0.45 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Esophageal | 4 | 14 | 9 | 31 | |||

|

| |||||||

| Gastric | 7 | 25 | 8 | 28 | |||

|

| |||||||

| Small bowel | 8 | 29 | 6 | 21 | |||

|

| |||||||

| Colorectal | 9 | 32 | 6 | 21 | |||

|

| |||||||

| Pancreas | 37 | 27.8 | 36 | 27.3 | 0.92 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Whipple | 24 | 65 | 26 | 72 | |||

|

| |||||||

| Distal | 11 | 30 | 9 | 25 | |||

|

| |||||||

| Total | 2 | 5 | 1 | 3 | |||

|

| |||||||

| CRS/HIPEC | 68 | 51.1 | 67 | 50.8 | 0.85 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Colorectal resection | 49 | 47 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| No colorectal resection | 19 | 20 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Laparoscopic-assisted cases | 4 | 3.0 | 2 | 1.5 | 0.45 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Operative time, hours | 7.5 (1.5–14.3) | 8.0 (1.5–19.5) | 0.8 | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Estimated blood loss, mL | 500 (5–3,700) | 500 (9–2,750) | 0.81 | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Transfusions | 15/132 | 11.4 | 12/131 | 9.2 | 0.69 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Units transfused, n | 2 (1–6) | 3 (1–6) | 0.039 | ||||

CRS/HIPEC, cytoreductive surgery/hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy.

Wound and clinical outcomes

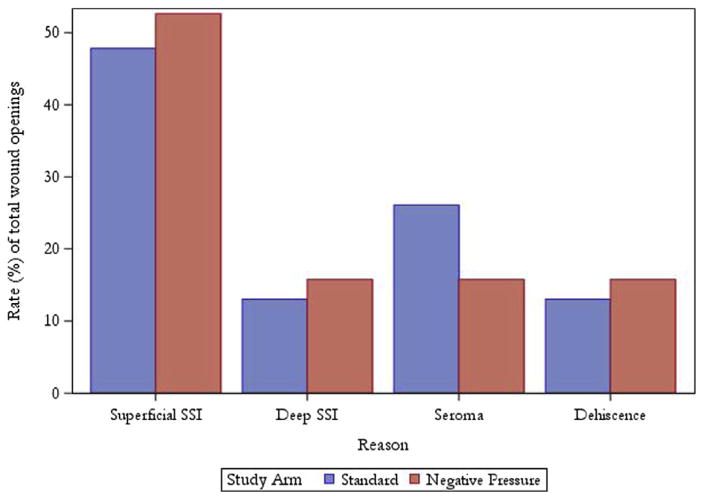

Table 3 shows SSI and wound complication rates between the 2 study arms stratified by operation type. The combined incisional SSI rates for the SSD and NPWT arms were 15.8% (n = 21) and 15.9% (n = 21), respectively (p > 0.99). There was also no difference in organ/space SSI rates or other wound complications between the 2 groups. Twenty-three patients (17.3%) in the SSD arm had their wound opened for any reason, and 19 patients (14.4%) had their wound opened in the NPWT arm (p = 0.61). When comparing the SSD to the NPWT groups in terms of causes of wound opening, the distribution is as follows: superficial SSI, 11 of 23 (48%) and 10 of 19 (53%); deep SSI, 3 of 23 (13%) and 3 of 19 (16%); seroma, 6 of 23 (26%) and 3 of 19 (16%); and dehiscence, 3 of 23 (13%) and 3 of 19 (16%) (Fig. 2). In the NPWT arm, drainage from the incision was collected in only 7 patients, with a median total drainage amount of 10 mL (range 1 to 800 mL) during the 4-day treatment period. Median postoperative day for occurrence of incisional SSI in the SSD and NPWT arms was 13 (range 4 to 26) and 12 (range 3 to 35), respectively (p = 0.54).

Table 3.

Wound and Surgical Site Infection Outcomes Stratified by Operation Type

| Outcome | Overall | Gastrointestinal | Pancreas | CRS/HIPEC | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Standard | NPWT | p Value | Standard | NPWT | p Value | Standard | NPWT | P Value | Standard | NPWT | p Value | |

| Total, N | 133 | 132 | 28 | 29 | 37 | 36 | 68 | 67 | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Combined incisional SSI, n (%) | 21 (15.8) | 21 (15.9) | >0.99 | 7 (25) | 7 (24) | >0.99 | 8 (22) | 8 (22) | >0.99 | 6 (9) | 6 (9) | >0.99 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Superficial | 17 (12.8) | 17 (12.9) | >0.99 | 7 (25) | 7 (24) | >0.99 | 6 (16) | 5 (14) | >0.99 | 4 (6) | 5 (7) | 0.74 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Deep | 4 (3.0) | 4 (3.0) | >0.99 | 0 | 0 | 2 (5) | 3 (8) | 0.67 | 2 (3) | 1 (1) | >0.99 | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Organ/space SSI, n (%) | 7 (5.3) | 5 (3.8) | 0.77 | 0 | 0 | 3 (8) | 3 (8) | >0.99 | 4 (6) | 2 (3) | 0.68 | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Seroma, n (%) | 8 (6.0) | 7 (5.3) | >0.99 | 0 | 2 (7) | 0.49 | 6 (16) | 4 (11) | 0.74 | 2 (3) | 1 (1) | >0.99 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Hematoma, n (%) | 0 | 1 (0.8) | 0.5 | 0 | 1 (3) | >0.99 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Incisional cellulitis, n (%) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.8) | >0.99 | 1 (4) | 1 (3) | >0.99 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Wound dehiscence, n (%) | 3 (2.3) | 3 (2.3) | >0.99 | 0 | 0 | 2 (5) | 1 (3) | >0.99 | 1 (1) | 2 (3) | 0.62 | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Skin | 3 (2.3) | 2 (1.5) | >0.99 | 0 | 0 | 2 (5) | 1 (3) | >0.99 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | >0.99 | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Fascia | 0 | 1 (0.8) | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0.5 | ||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Wound opening for any reason, n (%) | 23 (17.3) | 19 (14.4) | 0.61 | 5 (18) | 4 (14) | 0.73 | 13 (35) | 9 (25) | 0.45 | 5 (7) | 6 (9) | 0.76 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Readmission within 30 d due to wound complication, n (%) | 6/119 (5.0) | 3/118 (2.5) | 0.33 | 0 | 0 | 5/33 (1.5) | 2/30 (6.7) | 0.26 | 1/64 (1.6) | 1/60 (1.7) | >0.99 | |

CRS/HIPEC, cytoreductive surgery/hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy; NPWT, negative-pressure wound therapy; SSI, surgical site infection.

Figure 2.

Causes of wound openings stratified by study arm. SSI, surgical site infection.

Overall major morbidity was 14.5% (16 of 110) and 15.5% (17 of 110) in the SSD and NPWT groups, respectively (p > 0.99). Patients undergoing pancreatectomy experienced the highest rates of grade 3 and 4 adverse events, followed by CRS/HIPEC and gastrointestinal patients. Readmission rate within 30 days of surgery for the SSD arm was 21.9% (26 of 119), and it was 15.3% (18 of 118) for the NPWT arm (p = 0.24). From available data, 5% and 2.5% of patients in the SSD and NPWT groups had to be readmitted for wound complications, respectively (p = 0.33). These outcomes were consistent when stratified by operation type as well. Of 307 potentially analyzable patients, 2.3% (n = 7) died within 30 days of surgery and were not included in the outcomes analysis.

Predictors of wound complications

Univariate analysis of demographic and operative factors demonstrated a significant association of smoking (p = 0.017), preoperative albumin (p = 0.0006), and operation type (p = 0.0086) with combined incisional SSI (Table 4). The CRS/HIPEC operations had a lower odds ratio for SSI events compared with pancreatic (p = 0.011) or gastrointestinal (p = 0.0052) procedures. Both increasing age (p = 0.064) and presence of cardiovascular disease (p = 0.093) trended toward increased risk of incisional SSI. On multivariate analysis, both increased preoperative albumin (p = 0.0031) and operation type (CRS/HIPEC vs both gastrointestinal and pancreatic operations) (p = 0.018) were protective against combined incisional SSI. Preoperative albumin was analyzed as a continuous variable with a 10% decrease of SSI rate with each 0.1-unit increase of value.

Table 4.

Univariate and Multivariate Analysis of Predictors of Incisional Surgical Site Infection

| Variable | n | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate factors for superficial/deep SSI | ||||

| Dressing type (SSD vs NPWT) | 265 | 1.01 | 0.52–1.95 | >0.99 |

| Age | 265 | 1.15 | 0.99–1.34 | 0.064 |

| Sex, female | 265 | 0.81 | 0.41–1.58 | 0.53 |

| Race | 260 | 0.31 | 0.07–1.35 | 0.12 |

| Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group | 245 | 1.23 | 0.70–2.18 | 0.47 |

| BMI | 265 | 1.04 | 0.99–1.10 | 0.12 |

| Diabetes | 264 | 1.41 | 0.67–2.95 | 0.36 |

| COPD | 264 | 2.17 | 0.73–6.45 | 0.16 |

| Renal failure | 262 | 0.57 | 0.07–4.63 | 0.6 |

| Hypertension | 265 | 1.43 | 0.75–2.89 | 0.26 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 264 | 2.00 | 0.89–4.48 | 0.093 |

| Previous abdominal surgery | 265 | 1.62 | 0.82–3.19 | 0.17 |

| Smoking | 263 | 2.33 | 1.17–4.67 | 0.017 |

| Preoperative chemotherapy | 261 | 1.44 | 0.70–2.97 | 0.32 |

| Preoperative radiation | 265 | 2.31 | 0.84–6.37 | 0.1 |

| Preoperative albumin | 250 | 0.88 | 0.82–0.95 | 0.0006 |

| American Society of Anesthesiologists class* | 265 | |||

| 2 vs 4 | 1.37 | 0.29–6.48 | 0.69 | |

| 3 vs 4 | 0.75 | 0.20–2.77 | 0.66 | |

| 2 vs 3 | 1.83 | 0.68–4.92 | 0.23 | |

| Type of operation† | 265 | |||

| GI vs pancreatic | 1.16 | 0.51–2.63 | 0.72 | |

| CRS/HIPEC vs pancreatic | 0.35 | 0.15–0.78 | 0.011 | |

| CRS/HIPEC vs GI | 0.3 | 0.13–0.70 | 0.0052 | |

| Operative time, h | 265 | 1.02 | 0.91–1.15 | 0.74 |

| Estimated blood loss | 263 | 1.01 | 0.95–1.08 | 0.69 |

| Units of blood transferred | 265 | 0.98 | 0.66–1.44 | 0.91 |

| Laparoscopic-assisted | 265 | 1.06 | 0.12–9.03 | 0.96 |

| Best fit multivariate factors for superficial/deep incisional SSI | ||||

| Preoperative albumin | 250 | 0.89 | 0.83–0.96 | 0.0031 |

| Type of operation‡ | 250 | |||

| GI vs pancreatic | 1.56 | 0.65–3.73 | 0.32 | |

| HIPEC vs pancreatic | 0.44 | 0.18–1.06 | 0.067 | |

| HIPEC vs GI | 0.28 | 0.12–0.69 | 0.0052 | |

Overall p = 0.47.

Overall p = 0.0086.

Overall p = 0.018.

CRS, cytoreductive surgery; GI, gastrointestinal; HIPEC, hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy; NPWT, negative-pressure wound therapy; SSI, surgical site infection; SSD, standard surgical dressing.

Protocol deviations

Protocol deviations occurred in 3 main categories and are outlined in Table 5. Thirteen patients of the 265 in the study group (4.9%) did not have their dressing removed on postoperative day 4. Almost all of them were removed earlier on day 2, which is the usual day dressings are removed for nonstudy patients. One patient had a laparoscopic-assisted procedure and was discharged on postoperative day 3, requiring the NPWT dressing to be removed 1 day early. In 128 patients (48.3%), daily incision assessments were not performed at some point during their hospital stay or at one of their clinic visits. Study records do not indicate exactly what postoperative day this occurred. The third type of protocol deviation, follow-up outside of window (postoperative day 30 to 35) occurred in 104 (39.2%) patients. In 1 patient, final study follow-up occurred on postoperative day 29, but all of the rest of the follow-up deviations occurred after postoperative day 35.

Table 5.

Protocol Deviations

| Deviation | Total (N = 265) | |

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Dressing not removed on POD 4 | 13 | 4.9 |

| Daily incision assessment not performed | 128 | 48.3 |

| Follow-up outside of window (POD 30 to 35) | 104 | 39.2 |

POD, postoperative day.

DISCUSSION

There are several mechanisms proposed for how NPWT over a closed surgical incision can decrease wound complications and SSIs. The negative pressure has been shown to reduce the lateral stresses on surgical closures by nearly 50% at the level of the epidermis, dermis, and within the subcutaneous tissues.30 This stabilizing effect on the closed incision keeps superficial and deeper tissue layers in contact with one another without shearing. The direction of tissue stresses more closely resembles intact tissues31 by bolstering the surgical closure in both the horizontal axis and vertical axis. Sealing of the incision from outside contamination through maintenance of a closed and sterile environment is an obvious function of NPWT. In addition, there are potential theoretical benefits of fluid removal, stimulation of cell proliferation through macro- and microdeformation of tissue, reduction of inflammatory mediators, and increasing tissue oxygen tension.16,21

The earliest reports of NPWT for closed surgical incisions come from the orthopaedic and cardiac literature. Stannard and colleagues32 published a level 1 prospective randomized multicenter study in 2012 on the use of NPWT compared with standard postoperative dressings on 249 patients treated with open reduction and internal fixation of lower-extremity fractures. There was a significant reduction in both infection and wound dehiscence in those patients treated with NPWT postoperatively. A report by Atkins and colleagues33 in 2009 reviewed 57 adult cardiac surgery patients whose sternotomy incisions were treated with NPWT for 4 days. On the basis of a pooled data risk-assessment model,34 these patients were considered at high risk for sternal wound infections and a minimum of 3 events were predicted. However, no complications were observed in the cardiac patients treated with NPWT. A possible reason for these benefits was posited by Pachowsky and colleagues,35 who found a statistically significant reduction in seroma formation with NPWT after total hip arthoplasty.

In patients with abdominal incisions, the effect of NPWT on SSIs is mainly limited to retrospective case series. In 2013, our group published a study of 191 patients undergoing resection of colorectal, pancreatic, or peritoneal surface malignancies treated with SSD (n = 87) or NPWT (n = 104).28 In our analysis, NPWT was associated with fewer superficial SSIs (6% vs 27.4%; p = 0.001) and fewer wound openings for any reason (16% vs 35.5%; p = 0.011). Bonds and colleagues24 also reported on NPWT in colorectal surgery patients undergoing open resections. Thirty-two patients treated with NPWT experienced an SSI rate of 12.5% (n = 4) compared with 222 patients treated with SSD who had an SSI rate of 29.3% (n = 65) (p = 0.055). On multivariate analysis, NPWT was significantly associated with a decreased SSI rate (p = 0.041). In our study, NPWT was continued for 4 days postoperatively, and in the Bonds study it was left for 5 to 7 days after surgery. Standard dressings were removed on postoperative day 2 in our study and was not stated in the Bonds study. Two smaller studies from the Second University of Naples reported on NPWT in patients with Crohn’s disease26 (n = 13) and colorectal surgery patients27 (n = 25) compared with patients treated with SSD. Both reported significant reductions in wound complications and SSIs in the treatment group. The duration of NPWT in both studies was 7 days compared with 2 days for SSD.

Patients were chosen for this randomized phase II trial because they were all considered at high risk for SSI. Although mortality has improved for patients undergoing major abdominal surgery for gastrointestinal,36 pancreatic,37 and peritoneal surface38 malignancies, morbidity is still significant and can affect up to 50% of patients.39 Based on our retrospective experience with NPWT in surgical oncology patients,28 we embarked on a randomized phase II trial of NPWT compared with SSD to confirm our initial findings. However, when studied in a prospective fashion, the use of NPWT did not decrease SSIs or wound complications in patients undergoing laparotomy for gastrointestinal, pancreatic, and peritoneal surface malignancies. There was no difference in wound opening for any reason or readmissions due to wound complications between the 2 study arms. This lack of difference persisted even when stratified by operation type.

Of the 375 patients initially randomized, 110 (29%) were not analyzed for the study. Almost 60% of excluded patients did not receive the allocated intervention because the surgery was canceled, patient was unresectable, wrong dressing was applied, or incorrect skin closure was performed (no staples). If the randomization had occurred immediately after closure instead of after registration, this would have avoided some patient dropout and also potentially reduced surgeon bias from knowing which study arm the patient was in during the operation. The other 40% of patients removed from analysis were due to lack of 30-day follow-up, reoperation for non-wound-related complications, and death within 30 days of surgery. It these patients had been included in the analysis based on an intent-to-treat model, they would have been censored for inability to assess primary or secondary outcomes.

One of the purported benefits of NPWT was that it removed fluid from the wound and decreased seroma formation.35 Only 7 patients in the NPWT arm had any fluid drainage recorded during daily incision assessments in our study, with the rate of seroma formation at 6.0% (n = 8) and 5.3% (n = 7) for patients in the SSD and NPWT arms, respectively. One NPWT patient did have 800 mL of drainage noted from the incision on postoperative day 4, which was much higher than any other treated patient in the study. This patient had a BMI of 50 kg/m2 and review of the operative note mentioned an extremely large subcutaneous space during incision closure. During the course of the study, the lack of drainage from the vacuum-assisted closure was noted as unexpected because the expectation was that patients treated with NPWT would have excess fluid in the wound removed by the negative pressure. It is possible that the sealing of the incision prevented fluid accumulation from draining into the suction canister. In addition, the timing of incisional SSI occurrence was not affected by the application of NPWT.

In patients who experienced wound openings, the largest percentage was due to superficial SSIs (Fig. 2). Seromas accounted for 26% of the wounds opened in the SSD cohort, and only 16% of patients in the NPWT group had their wounds opened for this reason. However, many of these wound openings due to seroma were small separations of the skin, ranging in size from 1 to 3 cm, and very superficial in nature. Of the 33 wound complications (superficial SSI, deep SSI, seroma, hematoma, incisional cellulitis, and dehiscence) in the SSD group, 23 (69.7%) resulted in wound openings. In the NPWT group, 19 (57.6%) of 33 wound complications were opened. A substantial portion of wound complications were managed without being opened and undergoing dressing changes.

Univariate analysis demonstrated a history of or current smoking, preoperative albumin, and operation type as being associated with combined incisional SSI. The CRS/HIPEC procedures had a significantly lower odds ratio for incisional SSI compared with pancreatic and gastrointestinal operations. In fact, the wound infection rates for CRS/HIPEC operations were more than 50% less than those of the other 2 operation types. On multivariate analysis only, increasing preoperative albumin and CRS/HIPEC operations were independently predictive for decreased incisional SSI rates.

Several reasons why this was a negative study can be postulated. The same sealing of the incision that contributed to the lack of wound drainage in the NPWT arm could have allowed fluid accumulation in the wound at the same rate as the SSD group, leading to subsequent infectious complications. Other changes in the microenviroment of an open wound that promote wound healing—increased angiogenesis and removal of cytokines and other inhibitors of wound healing—might not be active in a closed wound subject to NPWT.40–43 On a more macroscopic level, the actual physical coverage of the incision can decrease SSI formation by preventing wound contamination. In our own retrospective study,28 and in the 2 studies from Pellino and colleagues,26,27 NPWT was applied for 2 to 5 days longer than the SSD in the historical comparison control arms; and in the current study, both interventions were left in place until postoperative day 4. These differences in wound coverage might have been a confounding factor in the development of SSIs and wound complications in these uncontrolled retrospective studies.

There are several limitations to this study. The optimal length of time for NPWT on a closed incision has not been determined. It is possible that applying NPWT to a closed laparotomy incision longer than 4 days postoperatively might have altered the outcomes. However, the SSD would also have to be applied for the same length of time. The 4-day application period was based on discussion with our plastic surgeons, who have extensive experience with NPWT. Another potential confounding factor is the inclusion of 3 different types of surgical procedures with different rates of morbidity and incisional SSI occurrence. Although the study was designed with upfront stratification, the actual numbers of patients in each strata are small, allowing for increased variability of events that might lead to a type II error. Lastly, in our initial report of NPWT for closed laparotomy incisions,28 12.5% of all SSIs occurred more than 30 days after surgery. It is likely that some SSIs occurring in this study were not documented because they occurred after the follow-up period, which also might have affected the outcomes.

This study highlights how the results of a proposed therapeutic intervention can appear beneficial in a retrospective case series analysis, but come up short in a randomized clinical trial. Admittedly, this is only one study and although the results appear definitive, additional investigation is warranted. Unlike many other areas in surgical therapy in which there is an unrealized hope for more randomized studies, there are at least 2 ongoing studies evaluating the use of NPWT in patients undergoing open elective gastrointestinal surgery.44,45 With greater numbers of patients being studied in prospective trials, a clearer picture on the role of NPWT for closed laparotomy incisions should emerge.

CONCLUSIONS

This application of NPWT in patients undergoing open gastrointestinal, pancreatic, or CRS/HIPEC operations did not decrease the rate of SSIs or wound complications compared with SSD. Therefore, it cannot currently be recommended as an intervention for the prevention of infectious complications after abdominal surgery.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Daphne Denise Witherspoon for her assistance with data collection.

Support: This work was supported by the Wake Forest Department of General Surgery and the Wake Forest University Biostatistics shared resource (NCI CCSG P30CA012197).

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- CRS/HIPEC

cytoreductive surgery/hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy

- NPWT

negative-pressure wound therapy

- SSD

standard surgical dressing

- SSI

surgical site infection

Footnotes

Disclosure Information: Nothing to disclose.

Presented at the Southern Surgical Association, 128th Annual Meeting, Palm Beach, FL, December 2016.

Author Contributions

Study conception and design: Shen, Blackham

Acquisition of data: Shen, Blackham, Lewis, Clark, Howerton, Mogal, Dodson, Levine

Analysis and interpretation of data: Shen, Blackham, Russell, Levine

Drafting of manuscript: Shen, Blackham, Russell

Critical revision: Shen, Blackham, Russell, Levine

References

- 1.Horan TC, Gaynes RP, Martone WJ, et al. CDC definitions of nosocomial surgical site infections, 1992: a modification of CDC definitions of surgical wound infections. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1992;13:606–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Consensus paper on the surveillance of surgical wound infections. The Society for Hospital Epidemiology of America; The Association for Practitioners in Infection Control; The Centers for Disease Control; The Surgical Infection Society. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1992;13:599–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewis SS, Moehring RW, Chen LF, et al. Assessing the relative burden of hospital-acquired infections in a network of community hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34:1229–1230. doi: 10.1086/673443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tanner J, Padley W, Assadian O, et al. Do surgical care bundles reduce the risk of surgical site infections in patients undergoing colorectal surgery? A systematic review and cohort meta-analysis of 8,515 patients. Surgery. 2015;158:66–77. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2015.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Venkat R, Edil BH, Schulick RD, et al. Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy is associated with significantly less overall morbidity compared to the open technique: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2012;255:1048–1059. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318251ee09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guinan JL, McGuckin M, Nowell PC. Management of health-care–associated infections in the oncology patient. Oncology (Williston Park, NY) 2003;17:415–420. discussion 423–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyce JM, Potter-Bynoe G, Dziobek L. Hospital reimbursement patterns among patients with surgical wound infections following open heart surgery. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1990;11:89–93. doi: 10.1086/646127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poulsen KB, Bremmelgaard A, Sørensen AI, et al. Estimated costs of postoperative wound infections. A case-control study of marginal hospital and social security costs. Epidemiol Infect. 1994;113:283–295. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800051712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vegas AA, Jodra VM, García ML. Nosocomial infection in surgery wards: a controlled study of increased duration of hospital stays and direct cost of hospitalization. Eur J Epidemiol. 1993;9:504–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirkland KB, Briggs JP, Trivette SL, et al. The impact of surgical-site infections in the 1990s: attributable mortality, excess length of hospitalization, and extra costs. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999;20:725–730. doi: 10.1086/501572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Varela JE, Wilson SE, Nguyen NT. Laparoscopic surgery significantly reduces surgical-site infections compared with open surgery. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:270–276. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0569-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shabanzadeh DM, Sørensen LT. Laparoscopic surgery compared with open surgery decreases surgical site infection in obese patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2012;256:934–945. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318269a46b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cima R, Dankbar E, Lovely J, et al. Colorectal surgery surgical site infection reduction program: a national surgical quality improvement program-driven multidisciplinary single-institution experience. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216:23–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keenan JE, Speicher PJ, Thacker JKM, et al. The preventive surgical site infection bundle in colorectal surgery: an effective approach to surgical site infection reduction and health care cost savings. JAMA Surg. 2014;149:1045–1052. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pellino G, Sciaudone G, Selvaggi F, Canonico S. Prophylactic negative pressure wound therapy in colorectal surgery. Effects on surgical site events: current status and call to action. Updates Surg. 2015;67:235–245. doi: 10.1007/s13304-015-0298-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Orgill DP, Bayer LR. Negative pressure wound therapy: past, present and future. Int Wound J. 2013;10(Suppl 1):15–19. doi: 10.1111/iwj.12170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Argenta LC, Morykwas MJ. Vacuum-assisted closure: a new method for wound control and treatment: clinical experience. Ann Plast Surg. 1997;38:563–576. discussion 577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morykwas MJ, Argenta LC, Shelton-Brown EI, McGuirt W. Vacuum-assisted closure: a new method for wound control and treatment: animal studies and basic foundation. Ann Plast Surg. 1997;38:553–562. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199706000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lynam S, Mark KS, Temkin SM. Primary placement of incisional negative pressure wound therapy at time of laparotomy for gynecologic malignancies. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2016;26:1525–1529. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mark KS, Alger L, Terplan M. Incisional negative pressure therapy to prevent wound complications following cesarean section in morbidly obese women: a pilot study. Surg Innov. 2014;21:345–349. doi: 10.1177/1553350613503736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scalise A, Calamita R, Tartaglione C, et al. Improving wound healing and preventing surgical site complications of closed surgical incisions: a possible role of Incisional Negative Pressure Wound Therapy. A systematic review of the literature. Int Wound J. 2016;13:1260–1281. doi: 10.1111/iwj.12492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stannard JP, Gabriel A, Lehner B. Use of negative pressure wound therapy over clean, closed surgical incisions. Int Wound J. 2012;9(Suppl 1):32–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-481X.2012.01017.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Willy C, Agarwal A, Andersen CA, et al. Closed incision negative pressure therapy: international multidisciplinary consensus recommendations. Int Wound J. 2016 May 12; doi: 10.1111/iwj.12612. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bonds AM, Novick TK, Dietert JB, et al. Incisional negative pressure wound therapy significantly reduces surgical site infection in open colorectal surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:1403–1408. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e3182a39959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kugler NW, Carver TW, Paul JS. Negative pressure therapy is effective in abdominal incision closure. J Surg Res. 2016;203:491–494. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2016.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pellino G, Sciaudone G, Candilio G, et al. Effects of a new pocket device for negative pressure wound therapy on surgical wounds of patients affected with Crohn’s disease: a pilot trial. Surg Innov. 2014;21:204–212. doi: 10.1177/1553350613496906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pellino G, Sciaudone G, Candilio G, et al. Preventive NPWT over closed incisions in general surgery: does age matter? Int J Surg. 2014;12(Suppl 2):S64–S68. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.08.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blackham AU, Farrah JP, McCoy TP, et al. Prevention of surgical site infections in high-risk patients with laparotomy incisions using negative-pressure therapy. Am J Surg. 2013;205:647–654. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mangram AJ, Horan TC, Pearson ML, et al. Guideline for prevention of surgical site infection, 1999. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999;20:247–280. doi: 10.1086/501620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilkes RP, Kilpad DV, Zhao Y, et al. Closed incision management with negative pressure wound therapy (CIM): biomechanics. Surg Innov. 2012;19:67–75. doi: 10.1177/1553350611414920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kubek EW, Badeau ABA, Materazzi S, et al. Negative-pressure wound therapy and the emerging role of incisional negative pressure wound therapy as prophylaxis against surgical site infections. In: Mendez-Vilas A, editor. Microbial Pathogens and Strategies for Combating Them: Science, Technology and Education. Badajoz, Spain: Formatex Research Center; 2013. pp. 1843–1846. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stannard JP, Volgas DA, McGwin G, et al. Incisional negative pressure wound therapy after high-risk lower extremity fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2012;26:37–42. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e318216b1e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Atkins BZ, Wooten MK, Kistler J, et al. Does negative pressure wound therapy have a role in preventing poststernotomy wound complications? Surg Innov. 2009;16:140–146. doi: 10.1177/1553350609334821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fowler VG, O’Brien SM, Muhlbaier LH, et al. Clinical predictors of major infections after cardiac surgery. Circulation. 2005;112(Suppl):I358–I365. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.525790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pachowsky M, Gusinde J, Klein A, et al. Negative pressure wound therapy to prevent seromas and treat surgical incisions after total hip arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2012;36:719–722. doi: 10.1007/s00264-011-1321-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Billeter AT, Polk HC, Hohmann SF, et al. Mortality after elective colon resection: the search for outcomes that define quality in surgical practice. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;214:436–443. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Finks JF, Osborne NH, Birkmeyer JD. Trends in hospital volume and operative mortality for high-risk surgery. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2128–2137. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1010705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Levine EA, Stewart JH, Shen P, et al. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy for peritoneal surface malignancy: experience with 1,000 patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218:573–585. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jakobson T, Karjagin J, Vipp L, et al. Postoperative complications and mortality after major gastrointestinal surgery. Medicina. 2014;50:111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.medici.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Erba P, Ogawa R, Ackermann M, et al. Angiogenesis in wounds treated by microdeformational wound therapy. Ann Surg. 2011;253:402–409. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31820563a8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Labler L, Rancan M, Mica L, et al. Vacuum-assisted closure therapy increases local interleukin-8 and vascular endothelial growth factor levels in traumatic wounds. J Trauma. 2009;66:749–757. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318171971a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Malmsjö M, Ingemansson R, Martin R, Huddleston E. Wound edge microvascular blood flow. Ann Plast Surg. 2009;63:676–681. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e31819ae01b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mous CM, van Toorenenbergen AW, Heule F, et al. The role of topical negative pressure in wound repair: expression of biochemical markers in wound fluid during wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2008;16:488–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2008.00395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chadi SA, Vogt KN, Knowles S, et al. Negative pressure wound therapy use to decrease surgical nosocomial events in colorectal resections (NEPTUNE): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2015;16:322. doi: 10.1186/s13063-015-0817-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mihaljevic AL, Schirren R, Müller TC, et al. Postoperative negative-pressure incision therapy following open colorectal surgery (Poniy): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2015;16:471. doi: 10.1186/s13063-015-0995-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]