Abstract

PURPOSE

To evaluate the incidence and risk factors of pneumothoraces requiring prolonged maintenance of a chest tube following CT-guided percutaneous lung biopsy in a retrospective, single-center case series.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All patients undergoing CT-guided percutaneous lung biopsies between 06/2012 and 05/2014 who required chest tube insertion for symptomatic or enlarging pneumothoraces were identified. Based on chest tube dwell time, patients were divided into two groups: short-term (0–2 days) or prolonged (3 or more days). The following risk factors were stratified between groups: patient demographics, target lesion characteristics, and procedural/periprocedural technique and outcomes.

RESULTS

2337 patients underwent lung biopsy, 543 developed pneumothorax (23.2%), 187 required chest tube placement (8.0%), and 55 required a chest tube for three days or more (2.9% of all biopsies, 29.9% of all chest tubes). The median chest tube dwell time for short-term and prolonged groups was 1.0 days and 4.7 days, respectively. Transfissural needle path predicted prolonged chest tube requirement (OR: 2.5; p=0.023). Other factors were not significantly different between groups.

CONCLUSION

2.9% of patients undergoing CT guided lung biopsy required a chest tube for 3 or more days. Transfissural needle path during biopsy was a risk factor for prolonged chest tube requirement.

Keywords: Lung, Biopsy, Pneumothorax, Chest Tubes, Image-Guided Biopsy

Introduction

CT-guided percutaneous lung biopsy (CPLB) provides accurate diagnosis of lung lesions with a sensitivity of 67–94% and specificity of 100% [1–5]. Some studies indicate that core biopsies provide a more accurate diagnosis than fine needle aspiration (FNA) [3] while others suggest that a combination of FNA and core biopsy specimens maximize the likelihood of providing a diagnostic specimen in a given patient [6; 7]. In light of its high diagnostic value with either strategy, CPLB is a common procedure in the clinical workup of concerning lung lesions—especially those that are inaccessible by transbronchial methods.

The most common complication after percutaneous lung biopsy is pneumothorax (incidence: 24–60%)[5; 8–18], followed by pulmonary hemorrhage (incidence: 0–15%) [8; 9; 19]. In light of the frequency at which pneumothorax occurs following CPLB, optimizing its management is an important goal in quality improvement. All-cause iatrogenic pneumothorax is associated with an estimated additional $17,000 in cost of care and 4 days’ length of hospital stay [20]. The average cost of a lung biopsy with complications is approximately four times higher than a complication-free biopsy ($37,745 vs. $8,869)[21] based on a cost analysis performed in the United States, with the conclusion that complicated biopsies are more expensive likely being generalizable outside the United States as well. Among the patients whose course is complicated by pneumothorax following CPLB, 5–53% require placement of a chest tube to assist resolution [5; 12–18]. At most centers, the chest tube is a small caliber (8 to 14 French) all-purpose drainage catheter attached to water seal or continuous suction, requiring inpatient management.

Observations from clinical practice have taught us that the majority of chest tubes can be removed within the first two days after placement (by post-CPLB day 2). The focus of the present study is on cases requiring prolonged chest tube dwell time. Existing studies have shown that 24–47% of chest tubes require prolonged maintenance (arbitrarily defined as 3 or more days) [8; 10; 11], and that this subgroup of patients more frequently need secondary interventions (i.e. chest tube reinsertion or upsizing)[10].

The purpose of the present study was to define the incidence and risk factors for chest tube requirement of 3 days or longer following CPLB toward the goal of better predicting these more protracted and complicated courses.

Materials and Methods

Data Collection

Our Institutional Review Board granted exemption to this retrospective case review. All protected health information was kept in a secure database compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. A total of 2337 CT-guided percutaneous lung biopsies were performed at our center during the inclusion period of June 2012 through May 2014, and included in the analysis.

Biopsy Technique

Biopsies were performed by one of fifteen board-certified interventional radiologists experienced in CPLB. Midazolam and fentanyl or meperidine alone was used for moderate sedation. Conventional CT or CT fluoroscopy was used for guidance. In patients with underlying emphysema/COPD, a needle path that did not traverse any blebs or bullae was always selected. Either coaxial or bare needle biopsy techniques were used based on operator’s preference, although the vast majority of cases were performed with coaxial technique. When a case required FNA samples alone, bare needle technique was used in some instances. Coaxial biopsies were generally done with 17 or 19 gauge introducer needles. When required, core biopsy samples were always obtained with coaxial technique using an 18 or 20 gauge semiautomatic core needle. FNA biopsies employed 20 or 22 gauge Wescott needles. A cytotechnologist performed immediate cytological assessment of all acquired samples to determine preliminary sample adequacy for diagnosis. Repeat biopsy was performed within the same procedure session until a presumed adequate sample was obtained, until the operator determined that additional material was unlikely to aid diagnosis, or until the procedure was terminated due to hemorrhage or urgent need for chest tube placement. Two out of 15 operators employed blood-patching technique at their discretion.

Post-biopsy Management

The interventional radiology service at our institution takes over primary decision-making surrounding chest tube management in every patient at our institution. The decision to place was made by a consensus of at least two interventional radiologists, and the placement was done by the first available physician to expedite care. Rarely, immediate large or symptomatic pneumothorax necessitated urgent placement of the chest tube during the initial biopsy procedure. For the vast majority of cases in which urgent chest tube placement was not required, chest x-rays were performed immediately post biopsy and 2 hours later to evaluate for the presence of pneumothorax following the monitoring and imaging protocol described by Brown et al [22]. Patients with no pneumothorax or stable asymptomatic pneumothorax on chest x-ray were discharged home with no further intervention. Patients with symptomatic (chest pain or dyspnea), enlarging, or circumferential pneumothorax underwent chest tube placement (8.5–12 French all purpose drainage catheter). Fluoroscopy was used for imaging guidance and patients again received moderate sedation. Chest tubes were placed either on water seal or suction (in the case of large air leak, persistent pneumothorax on water seal, or per operator preference). Patients were observed (and admitted at the discretion of the operator) until resolution of pneumothorax on serial chest x-rays and successful removal of chest tube after a tube-clamping trial. The protocol for chest tube management at our institution is as follows: Once no air leak is evident and chest x-ray shows minimal or no pneumothorax we progress from suction (if used) to water seal, followed by a clamping trial, during which the catheter is closed via a 3-way stopcock for a minimum of one hour. If a chest x-ray at the end of the clamping trial is unchanged, the tube is removed. Decision for removal is achieved by consensus of at least two interventional radiologists at morning rounds. Patients with persistent air leak or malfunctioning/misplaced chest tubes underwent exchange or upsizing of the tube in a second procedure.

Data Collection

A registered, prospective institutional database of all CT-guided lung biopsies performed in a 2-year period from 06/2012 through 05/2014 includes the following data: Patient demographics, operator, needle gauge, number of specimens, and date of chest tube placement. We reviewed all cases within this database to identify the subset of patients who received a chest tube for management of iatrogenic pneumothorax as the study group of interest. Patient charts, intraprocedural CT images, and post-procedural chest x-rays were retrospectively reviewed for all study group patients. Data collection included patient variables (sex, age, documented clinical diagnosis of emphysema/COPD), target variables (maximum axial diameter, laterality, lobe, prior ipsilateral chest intervention (including biopsy, ablation, surgery, or radiation), distance from nearest pleural surface (zero indicating a pleural-based lesion), pathology reports); procedural variables (coaxial versus noncoaxial technique, FNA only vs. core +/− FNA, largest needle size used, patient position, length of procedure, path of needle, number of pleural interface punctures); and clinical course of pneumothorax and its management (pneumothorax size, chest tube size, presence of air leak, chest tube dwell time). In counting pleural interface punctures, one puncture was counted for each passage of a needle either a) percutaneously through parietal and into visceral pleura to enter the lung parenchyma, or b) through two layers of visceral pleura to cross a fissure. One of three designations was assigned to describe the needle path: An intraparenchymal needle path passed through no lung fissures, a transfissural needle path passed through at least one major or minor fissure, and a superficial needle path had a shallow trajectory, passing just below (within 2 cm of) the pleural surface for its entirety. Chest tube dwell time was assigned on the basis of the interval between procedure note timestamps from chest tube insertion and removal. Although a total of 190 chest tubes were recorded in the database, 3 cases were excluded. Two cases were excluded from analysis due to a thermal ablation procedure done during the same session, and one case was excluded because a chest tube was placed for pre-existing empyema rather than for post-CTLB pneumothorax.

Statistical Analysis

Univariate statistical analyses were performed using Prism version 6.00 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla California, USA). Descriptive statistics are represented as mean +/− SD. Categorical variables were compared using Fisher exact or chi-square tests. Continuous variables were analyzed using Mann-Whitney or Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance. For variables that reached significance, odd ratios and confidence intervals were computed using two-way contingency tables. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Incidence Analysis

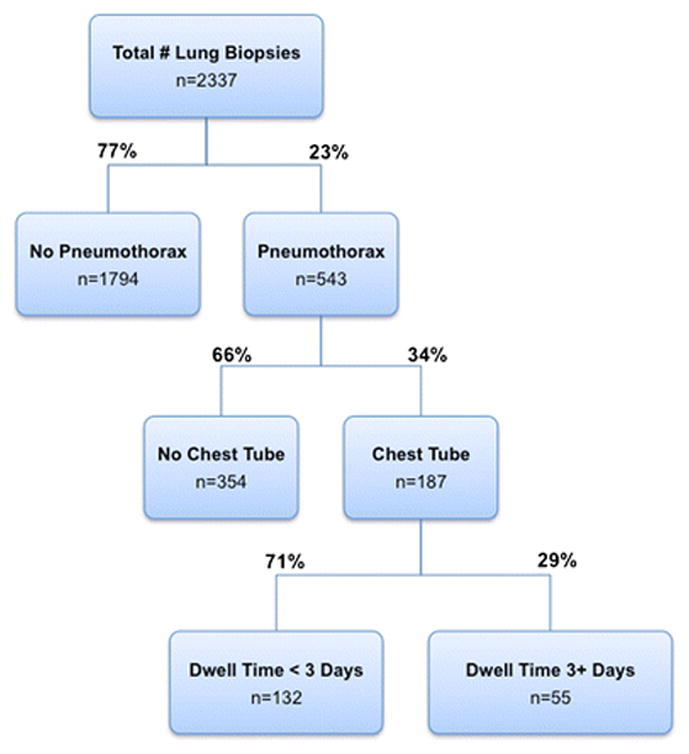

Among the 2337 patients on whom CT-guided percutaneous lung biopsy was performed during the study period, 543 developed post-procedural pneumothorax visible on chest x-ray (23.2%). A total of 187 patients required chest tube placement (8.0% of all biopsies and 34.4% of all pneumothoraces), and 55 required a chest tube for three days or more (2.9% of all biopsies, 10.1% of all pneumothoraces, and 29.4% of all chest tubes) (Figure 1). The median dwell times of chest tubes for short-term and prolonged groups were 1.0 days (range: 0.2–2.0) and 4.7 days (range: 3.0–13.8), respectively.

Figure 1.

Incidence of pneumothorax, chest tube placement, and prolonged chest tube requirement post percutaneous lung biopsy.

Demographic Risk Factors for Prolonged Chest Tube Requirement

A demographic comparison of patients requiring short term versus prolonged chest tube dwell times is summarized in Table 1. Age, sex, history of prior ipsilateral lung interventions, history of smoking, and underlying clinical diagnoses of emphysema/COPD were not significantly different between the two groups.

Table 1. Patient demographic risk factors for prolonged chest tube requirement post percutaneous lung biopsy.

P-values represent result of Mann-Whitney test for age, Fisher exact test for all other factors.

| Chest tube dwell time < 3 days post biopsy | Chest tube dwell time ≥ 3 days post-biopsy | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Total (n) | 132 | 55 | |

|

| |||

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 70 ±11 | 67±12 | p= 0.25 |

| Range | 31–92 | 25–92 | |

|

| |||

| Sex | |||

| % Male (n) | 53% (70) | 51% (28) | P= 0.87 |

|

| |||

| Prior ipsilateral lung intervention % | |||

| %Total (n) | 27% (36) | 20% (11) | p =0.28 |

| % Biopsy only (n) | 12% (16) | 7% (4) | p=0.44 |

| % Ablation (n) | 0.7% (1) | 2% (1) | p=0.50 |

| % Surgery (n) | 12% (16) | 18% (5) | p=0.62 |

| % Radiation (n) | 1.5% (2) | 2% (1) | p = 1.00 |

|

| |||

| History of smoking | 66% (37) | 56% (30) | p= 0.18 |

| % Yes (n) | |||

|

| |||

| Underlying emphysema/COPD | |||

| %Yes(n) | 27% (34) | 33% (18) | p=0.48 |

Target-Related Risk Factors for Prolonged Chest Tube Requirement

A comparison of target lesion features between patients requiring short term versus prolonged chest tube dwell time is summarized in Table 2. Lesion diameter, laterality, lobe, and distance from pleura were similar between both groups. The rates of nondiagnostic versus benign versus malignant findings on pathologic assessment were not significantly different between the two groups. Considering malignant lesions only, there was no significant difference in the rate at which pathologic features suggestive of metastatic origin were present between the two groups. Among presumed primary lung malignancies, there was no difference in the rate of tumor subtypes between short term and prolonged chest tube groups.

Table 2. Target lesion features as risk factors for prolonged chest tube requirement post percutaneous lung biopsy.

P- values represent result of Mann-Whitney test for diameter and distances, Fisher exact test for laterality, and chi-square for lobe and pathologic categories.

| Chest tube dwell time <3 days post- biopsy | Chest tube dwell time ≥3 days post-biopsy | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Total (n) | 132 | 55 | |

|

| |||

| Lesion Diameter (mm) | |||

| Median | 17.0 | 17.5 | p = 0.59 |

| Range | 8.0–63.0 | 5.0–61.0 | |

|

| |||

| Lesion distance from pleura along needle path (mm) | |||

| Median | 32.0 | 29.0 | p = 0.64 |

| Range | 0.0–113.0 | 0.0–83.0 | |

|

| |||

| Lesion distance from pleura along needle path (mm) | |||

| Median | 78.5 | 73.0 | p = 0.72 |

| Range | 0.0–155.0 | 0.0–146.0 | |

|

| |||

| Right vs. left lung | |||

| % R (n) | 60% (80) | 46% (25) | p = 0.10 |

|

| |||

| Lobe | |||

| % Left Upper (n) | 33.8% (26) | 43.5% (10) | p = 0.20 |

| % Left Lower (n) | 5.2% (4) | 17.4% (4) | |

| % Right Upper (n) | 42.9% (33) | 26.1% (6) | |

| % Right Middle (n) | 6.4% (5) | 8.7% (2) | |

| % Right Lower (n) | 11.7% (9) | 4.3% (1) | |

|

| |||

| Tissue diagnosis | |||

| % Non-diagnostic | 3.0% (4) | 3.6% (2) | p = 0.77 |

| % Benign | 21.1% (28) | 25.5% (14) | |

| % Malignant | 75.9% (100) | 70.9% (39) | |

|

| |||

| Primary vs. metastatic | |||

| % Pathologic diagnosis suggestive of metastasis (n) | 21% (19) | 24% (8) | p = 0.80 |

|

| |||

| Lung Primary Subtypes | p = 0.30 | ||

| % Adenocarcinoma (n) | 84.5% (59) | 79.2% (19) | |

| % Squamous (n) | 14.1% (10) | 12.5% (3) | |

| % Small Cell (n) | 0% (0) | 4.2% (1) | |

| % Mesothelioma (n) | 1.4% (1) | 4.2% (1) | |

Procedural/Periprocedural Risk Factors for Prolonged Chest Tube Requirement

Table 3 compares technical approach and immediate-post procedure outcomes between patients requiring short term and prolonged chest tubes.

Table 3. Procedural/periprocedural risk factors for prolonged chest tube requirement post percutaneous lung biopsy.

P- values represent result of Mann-Whitney test for needle gauge, number of pleural interface punctures, and sedation time; Fisher exact test for coaxial/non-coaxial technique, biopsy type, patient positioning, pneumothorax size, and presence of air leak; and chi-square for needle path and chest tube size.

| Chest tube dwell time <3 days post- biopsy | Chest tube dwell time ≥3 days post- biopsy | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Total (n) | 132 | 55 | |

|

| |||

| Coaxial vs. non-coaxial technique | |||

| % Coaxial (n) | 84.1% (111) | 81.8% (45) | p = 0.67 |

|

| |||

| Core biopsy + FNA vs. FNA only | |||

| % Core biopsy + FNA (n) | 81.3% (104) | 80.8% (42) | p = 1.00 |

|

| |||

| Largest needle gauge used | |||

| Mean ± SD | 19.5 | 19.5 | p = 0.77 |

| Range | 17–22 | 17–22 | |

|

| |||

| Needle path | |||

| % Intraparenchymal | 73% (97) | 55% (30)16% (9) | p = 0.039* |

| % Superficial | 11% (14) | 29% (16) | |

| % Transfissural | 17% (21) | ||

|

| |||

| Number of pleural interface punctures (n) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 1.0 ± 0.7 | 1.0 ± 0.6 | p = 0.10 |

| Range | 1–6 | 1–3 | |

|

| |||

| Prone vs. supine patient positioning | |||

| % Prone (n) | 42% (54) | 35% (19) | p = 0.41 |

|

| |||

| Sedation time (minutes) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 38 ± 13 | 46 ± 22 | p = 0.051 |

| Range | 20–80 | 25–120 | |

|

| |||

| Large vs. small/intermediate pneumothorax | |||

| % Large pneumothorax (n) | 20% (26) | 27% (15) | p = 0.33 |

|

| |||

| Presence vs. absence of air leak | |||

| % Documented air leak (n) | 16% (21) | 18% (10) | p = 0.67 |

|

| |||

| Chest tube size (French) | |||

| % 8.5 (n) | 3.8% (5) | 0.0% (0) | p = 0.21 |

| % 10.2 (n) | 72.3% (94) | 72.3% (45) | |

| % 12 (n) | 23.8% (31) | 23.8% (10) | |

When biopsy results in chest tube placement, the odds of having a chest tube placed for greater than 3 days is 2.5 times higher for Transfissural vs Intraparenchymal biopsy OR 2.5; 95% CI = 1.14 – 5.31; p=0.023, Fisher exact test.

There was no significant difference between groups for the following aspects of the procedure: coaxial versus non-coaxial technique, core biopsy +/− FNA vs. FNA alone, largest needle gauge used, number of punctures through a pleural interface, or patient positioning. Procedure duration was longer on average among cases resulting in prolonged chest tube dwell time, but this trend did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.051). Needle path, however, did prove to be a significant risk factor for prolonged chest tube requirement (p = 0.039 for contingency analysis comparing all 3 needle path types), with a transfissural needle approach conferring higher risk than an intraparenchymal approach (Figures 2 and 3, p=0.038 for head-to-head contingency analysis between these two needle path types). No significant difference was found for superficial approach versus intraparenchymal or transfissural approach. When biopsy results in chest tube placement, the odds of having a chest tube placed for greater than 3 days is 2.5 times higher for transfissural biopsies than for intraparenchymal biopsies (95% CI = 1.14 – 5.31; p=0.023, Fisher exact test).

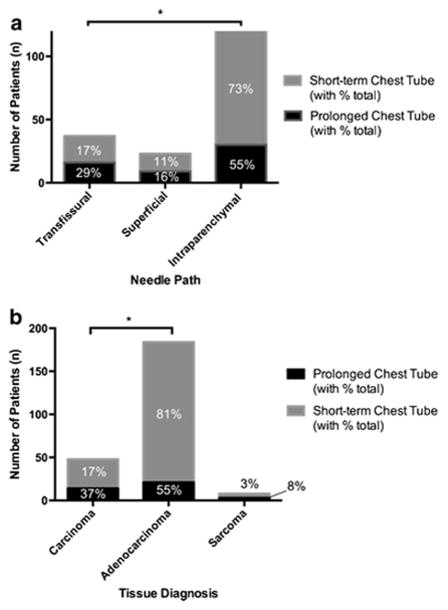

Figure 2. Needle path as a risk factor for prolonged chest tube dwell time post percutaneous lung biopsy.

Percentage of cases in each needle path category out of the total for the chest tube duration group (short term vs. prolonged) is represented numerically on column. Fisher exact text indicates that transfissural needle path is more often associated with prolonged chest tube dwell time than intraparenchymal needle path (p=0.038).

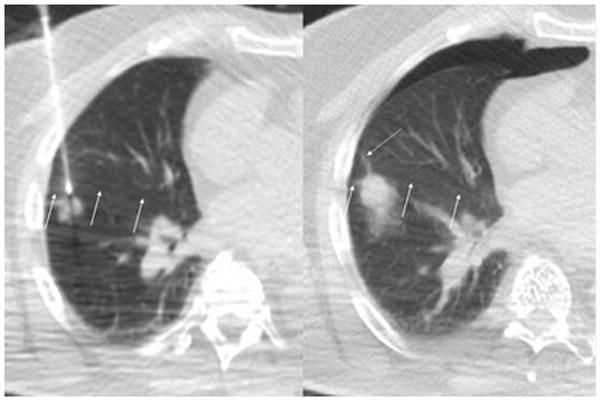

Figure 3. Example CPLB case with transfissural needle path.

Patient with history of colon cancer underwent CPLB of a new right lower lobe lesion with an anterior approach through the right middle lobe. Intraprocedural CT fluoroscopy image (left) with arrows indicating a non-vascular line hyperdense to the lung parenchyma corresponding to the right major fissure. Immediate post biopsy CT fluoroscopic image demonstrates a small anterior pneumothorax. The needle tract is indicated with a dotted arrow. This patient ultimately required a chest tube for just over 3 days.

Among post-biopsy monitoring parameters, initial size of pneumothorax, size of chest tube placed, and documented air leak did not prove to be predictive of short versus prolonged requirement for chest tube.

Discussion

In the era of personalized medicine, it is increasingly critical to have accurate information regarding the cell type and genetic/molecular composition of a given tumor. For example, while all non-small cell lung cancers were once treated in a similar fashion, this is no longer the case. Several studies have shown that tumor subtype and gene mutations can influence the response to different treatments [23–29].

CPLB is commonly used to provide safe and accurate diagnosis of lung lesions. Though CPLB is generally well-tolerated, complications of CPLB include pneumothorax, pulmonary hemorrhage (hemoptysis and hemothorax), air embolism, tumor seeding, and infection [19; 30]. Pneumothorax and pulmonary hemorrhage occur most commonly, while other complications are rare [19]. The reported frequency of pneumothorax after CPLB ranges from 24% to 60% [5; 8–18]. In the current study, the rate of pneumothorax was 23%--consistent with previous reports.

A body of literature has sought to identify risk factors for developing pneumothorax after CPLB, as well as risk factors for pneumothorax necessitating chest tube placement after CPLB. The key, large studies on this subject and the risk factors identified are outlined in Table 4. While the natural history of CPLB-associated pneumothorax is such that most resolve rapidly after chest tube placement, a subset are refractory, requiring prolonged chest tube dwell time [8; 10; 11]. Cases requiring prolonged chest tube maintenance can cause extended discomfort for patients and consume more resources within health care systems.

Table 4.

Key studies on risk factors for post-CPLB pneumothorax, chest tube placement, and prolonged chest tube maintenance

| Author, year (Study size*) | Risk factors for pneumothorax | Risk factors for chest tube placement | Risk factors for prolonged chest tube maintenance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ayyappan et al, 2008 (n = 107) | Emphysema in the needle path | Emphysema in the needle path | _ |

| Covey et al, 2004 (n = 453) | Increased patient age, smaller lesion size, history of smoking, no prior history of thoracic surgery, greater lesion depth from skin, CT guidance | Increased patient age, history of smoking, no history of thoracic surgery, supine patient position † | _ |

| Geraghty et al, 2003 (n = 846) | Increased patient age, larger needle gauge | _ | _ |

| Gupta et al, 2008 (n = 191) | _ | _ | Emphysema in the needle path |

| Hiraki et al, 2010 (n = 1,098) | No prior thoracic surgery, smaller lesion size, lesions in the lower lobe, greater lesion distance from the pleura, greater lesion depth, needle trajectory angle < 45° | Male sex, emphysema, lesions in upper or middle lobe, greater lesion depth, supine patient positioning | _ |

| Lim et al, 2014 (n = 381) | Small lesion size, increased lesion-pleural angle (if no aerated lung traversed); transfissural needle path (if aerated lung traversed) | _ | _ |

| Nakamura et al, 2011 (n = 156) | _ | Supine patient positioning | _ |

| Rizzo et al, 2011 (n = 157) | Small lesion size, longer needle path, transfissural needle path, core biopsy | _ | _ |

| Saji et al, 2002 (n = 289) | Male sex, FVC and FEV1 percent predicted, small lesion size, increased lesion distance from pleura, increased lesion-pleura angle | Lesion in lower lobe of lung, greater depth of lesion, increased lesion- pleura angle | _ |

| Swischuk et al, 1998 (n = 651) | None identified | None identified | _ |

| Vatrella et al, 2014 (n = 188) | Increased patient age | _ | _ |

Total number of CT-guided percutaneous lung biopsies reviewed

Risk factors for any pneumothorax treatment other than discharge to home, including observation (n=2) and manual aspiration (n=1)

The present study represents the largest published series to date (n=56) focusing on patients requiring prolonged chest tube dwell time after CPLB. The incidence of prolonged chest tube requirement (≥3 days) after CPLB has been estimated at 24–47% of patients who had chest tubes placed [8; 10; 11]. The current study reports a similar incidence of 29%.

In terms of non-modifiable patient and target-related predictors for prolonged chest tube dwell time, emphysematous parenchyma along the needle tract is the only previously published risk factor [10]. The mechanism proposed to explain this phenomenon is that obstructive pulmonary disease is associated with increased airway pressures, which may prevent tissue along needle tracts from re-apposing—thereby holding open a passage for persistent air leak. Emphysema was evaluated as a risk factor in the present study based on imaging findings of emphysema, plus emphysema/COPD as a documented patient diagnosis. Per institutional protocol, in no case did the needle tract pass through a bulla or bleb, and this was verified on imaging review of the needle path in each case. Although our data do not corroborate the findings of Gupta et al supporting emphysema as a risk factor for prolonged chest tube dwell time, this may be in part due to a relative underrepresentation of emphysema/COPD patients in our patient population (coming from an academic cancer center as opposed to the general population). While underlying emphysema/COPD does not represent a modifiable risk factor for prolonged chest tube dwell time, considering emphysema/COPD diagnosis in risk-stratifying patients before electing to pursue CPLB may aid both patients and operators in the informed consent process.

Transfissural (as opposed to intraparenchymal or superficial) needle path represents a potentially modifiable risk factor for developing prolonged chest tube requirement identified in this study. Gupta et al did evaluate the number of punctures of visceral pleura as a predictor of prolonged chest tube dwell time, but did not find it to be significant [10]. There is a reasonable corollary in the literature on post CPLB pneumothorax in general [13; 14], however, to suggest that transfissural needle path may predispose a patient to air leak following lung biopsy—with the hypothesis behind this phenomenon being that multiple pleural punctures leave multiple opportunities for air leak. The mechanism may also be in part from shearing at the punctures along a fissure as each lobe slides somewhat independently from the other with breathing and the needle is fixed within each of them. At a pleural puncture along the chest wall, the needle can move freely with the lung if it's in just one lobe, fixed with the chest wall as its pivot point--this might allow for less pleural tearing than occurs at the interface between two lobes for a transfissural puncture. These unique mechanical forces along transfissural punctures may explain in part why a non-stratified analysis of the number of all-type (including non-transfissural) pleural punctures was not significantly different between short term and prolonged chest tube duration groups in this series. Based on our findings in this series, it seems that if a reasonable alternative is available, an operator might try to avoid a transfissural needle trajectory during CPLB.

One negative result from this study is especially notable: the presence or absence of documented air leak was not found to be an indicator of requirement for prolonged chest tube in this series. The bedside method for assessing air leak (as signified by bubbles through the water chamber) used in clinical practice today is evidently not sensitive enough to capture all cases of clinically significant air leak.

This study was subject to several limitations, including its retrospective design, as well as its case load and practice patterns specific to an academic cancer center. Of note, whether blood patching technique was employed usually was not documented and therefore could not be accurately analyzed retrospectively. Only 2 out of 15 operators used blood patch technique for approximately half of their patients. While operator-specific pneumothorax rate was not calculated for this study, pneumothorax rate has not been found to be significantly different amongst the 15 operators based on internal quality assurance data. The two operators who employ blood-patching technique have individual chest tube rates as documented for institutional quality improvement data that are not significantly different than other operators in the group. For this reason we do not believe that the blood patch technique was likely to have predicted outcomes in this study. Additionally, as previously mentioned, this study did not evaluate patient CT scans for the presence and grade of emphysematous changes along needle tracts.

In conclusion, pneumothorax is known to be the most common complication of CPLB. About 30% of cases resulting in chest tube placement (2.9% of total CPLB cases) require chest tube maintenance of 3 or more days. The present study shows that biopsy needle paths that cross the lung fissures may also increase this risk. Cases should be risk-stratified accordingly, and transfissural biopsy needle paths should be avoided if possible.

KEY POINTS.

CT-guided percutaneous lung biopsy (CPLB) is an important method for diagnosing lung lesions 2.9% of patients require a chest tube for ≥3 days following CPLB Transfissural needle path is a risk factor for prolonged chest tube time

Acknowledgments

The scientific guarantor of this publication is Dr. Majid Maybody, M.D. The authors of this manuscript declare relationships with the following companies: Anna J. Moreland: Consultant, NeuWave Medical, Inc

Stephen B. Solomon: Grants, GE Healthcare. The authors of this manuscript declare no relationships with any companies whose products or services may be related to the subject matter of the article. The authors state that this work has not received any funding. No complex statistical methods were necessary for this paper. Institutional Review Board approval was not required because the study was exempt. Written informed consent was waived by the Institutional Review Board. Methodology: retrospective, observational, performed at one institution.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CPLB

CT-guided percutaneous lung biopsy

- FNA

Fine needle aspiration

- COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

References

- 1.Hirose T, Mori K, Machida S, Tominaga K, Yokoi K, Adachi M. Computed tomographic fluoroscopy-guided transthoracic needle biopsy for diagnosis of pulmonary nodules. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2000;30:259–262. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyd070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hur J, Lee HJ, Nam JE, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of CT fluoroscopy-guided needle aspiration biopsy of ground-glass opacity pulmonary lesions. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:629–634. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tuna T, Ozkaya S, Dirican A, Findik S, Atici AG, Erkan L. Diagnostic efficacy of computed tomography-guided transthoracic needle aspiration and biopsy in patients with pulmonary disease. Onco Targets Ther. 2013;6:1553–1557. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S45013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birchard KR. Transthoracic needle biopsy. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2011;28:87–97. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1273943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ayyappan AP, Souza CA, Seely J, Peterson R, Dennie C, Matzinger F. Ultrathin fine-needle aspiration biopsy of the lung with transfissural approach: does it increase the risk of pneumothorax? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191:1725–1729. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sigel CS, Moreira AL, Travis WD, et al. Subtyping of non-small cell lung carcinoma: a comparison of small biopsy and cytology specimens. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:1849–1856. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318227142d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stewart CJ, Coldewey J, Stewart IS. Comparison of fine needle aspiration cytology and needle core biopsy in the diagnosis of radiologically detected abdominal lesions. J Clin Pathol. 2002;55:93–97. doi: 10.1136/jcp.55.2.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hiraki T, Mimura H, Gobara H, et al. Incidence of and risk factors for pneumothorax and chest tube placement after CT fluoroscopy-guided percutaneous lung biopsy: retrospective analysis of the procedures conducted over a 9-year period. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194:809–814. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.3224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Covey AM, Gandhi R, Brody LA, Getrajdman G, Thaler HT, Brown KT. Factors associated with pneumothorax and pneumothorax requiring treatment after percutaneous lung biopsy in 443 consecutive patients. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2004;15:479–483. doi: 10.1097/01.rvi.0000124951.24134.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gupta S, Hicks ME, Wallace MJ, Ahrar K, Madoff DC, Murthy R. Outpatient management of postbiopsy pneumothorax with small-caliber chest tubes: factors affecting the need for prolonged drainage and additional interventions. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2008;31:342–348. doi: 10.1007/s00270-007-9250-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perlmutt LM, Braun SD, Newman GE, et al. Transthoracic needle aspiration: use of a small chest tube to treat pneumothorax. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1987;148:849–851. doi: 10.2214/ajr.148.5.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakamura M, Yoshizako T, Koyama S, Kitagaki H. Risk factors influencing chest tube placement among patients with pneumothorax because of CT-guided needle biopsy of the lung. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2011;55:474–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-9485.2011.02283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lim CS, Tan LE, Wang JY, et al. Risk factors of pneumothorax after CT-guided coaxial cutting needle lung biopsy through aerated versus nonaerated lung. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2014;25:1209–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2014.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rizzo S, Preda L, Raimondi S, et al. Risk factors for complications of CT-guided lung biopsies. Radiol Med. 2011;116:548–563. doi: 10.1007/s11547-011-0619-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saji H, Nakamura H, Tsuchida T, et al. The incidence and the risk of pneumothorax and chest tube placement after percutaneous CT-guided lung biopsy: the angle of the needle trajectory is a novel predictor. Chest. 2002;121:1521–1526. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.5.1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geraghty PR, Kee ST, McFarlane G, Razavi MK, Sze DY, Dake MD. CT-guided transthoracic needle aspiration biopsy of pulmonary nodules: needle size and pneumothorax rate. Radiology. 2003;229:475–481. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2291020499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Swischuk JL, Castaneda F, Patel JC, et al. Percutaneous transthoracic needle biopsy of the lung: review of 612 lesions. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1998;9:347–352. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(98)70279-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kazerooni EA, Lim FT, Mikhail A, Martinez FJ. Risk of pneumothorax in CT-guided transthoracic needle aspiration biopsy of the lung. Radiology. 1996;198:371–375. doi: 10.1148/radiology.198.2.8596834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu CC, Maher MM, Shepard JA. Complications of CT-guided percutaneous needle biopsy of the chest: prevention and management. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196:W678–682. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.4659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loiselle A, Parish JM, Wilkens JA, Jaroszewski DE. Managing iatrogenic pneumothorax and chest tubes. J Hosp Med. 2013;8:402–408. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lokhandwala TDR, Johnson M, D'Souza AO. Costs of the Diagnostic Workup for Lung Cancer - A Medicare Claims Analysis. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.08.142. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown KT, Brody LA, Getrajdman GI, Napp TE. Outpatient treatment of iatrogenic pneumothorax after needle biopsy. Radiology. 1997;205:249–252. doi: 10.1148/radiology.205.1.9314993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moreira AL, Thornton RH. Personalized medicine for non-small-cell lung cancer: implications of recent advances in tissue acquisition for molecular and histologic testing. Clin Lung Cancer. 2012;13:334–339. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2012.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson DH, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny WF, et al. Randomized phase II trial comparing bevacizumab plus carboplatin and paclitaxel with carboplatin and paclitaxel alone in previously untreated locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2184–2191. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scagliotti GV, Parikh P, von Pawel J, et al. Phase III study comparing cisplatin plus gemcitabine with cisplatin plus pemetrexed in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3543–3551. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.0375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:947–957. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang ZJ, An TT, Mok T, et al. Immediate Versus Delayed Treatment with EGFR Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors after First-line Therapy in Advanced Non-small-cell Lung CANCER. Chin J Cancer Res. 2011;23:112–117. doi: 10.1007/s11670-011-0112-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eberhard DA, Johnson BE, Amler LC, et al. Mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor and in KRAS are predictive and prognostic indicators in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer treated with chemotherapy alone and in combination with erlotinib. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5900–5909. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kwak EL, Bang YJ, Camidge DR, et al. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibition in non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1693–1703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1006448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vatrella A, Galderisi A, Nicoletta C, et al. Age as a risk factor in the occurrence of pneumothorax after transthoracic fine needle biopsy: our experience. Int J Surg. 2014;12(Suppl 2):S29–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.08.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]