Highlights

-

•

Obturator hernia is a rare condition among abdominal hernias.

-

•

Clinical diagnosis is challenging and it usually appears as an intestinal obstruction.

-

•

Early diagnosis and surgical treatment reduce morbidity and mortality.

Keywords: Intestinal obstruction, Obturator hernia, Howship-Romberg sign, Incarcerated hernia

Abstract

Introduction

Obturator hernia is a rare condition accounting for less than 1% of all intra abdominal hernias. Clinical diagnosis is considered a challenge for most surgeons. It usually appears as an intestinal obstruction. Confirmation of diagnosis is carried out by means of imaging or during surgery.

Case report

An 85-year-old female patient, with symptoms of intestinal obstruction of 24 h duration was admitted to the emergency room of Unimed Hospital – Belo Horizonte. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) demonstrated a herniation of the small bowel through the right obturator canal with an intestinal distension proximally. At laparotomy, the presence of a right obturator hernia with an ileal strangulation was confirmed. Segmental enterectomy with primary anastomosis and herniorrhaphy for the closure of the obturator foramen were performed.

Discussion

Obturator hernias typically affect women, elderly, emaciated and multiparous. Symptoms are non-specific and associated with an intestinal obstruction. Howship-Romberg sign, considered pathognomonic, is generally absent. Abdominal CT scan can aid in pre-operative diagnosis and the treatment is surgical.

Conclusion

Early diagnosis and surgical treatment are imperative in obturator hernias due to the high morbidity and mortality that occur in cases where the intervention is delayed.

1. Introduction

Quite unusual in medical routine, the obturator hernia accounts for a small part of abdominal hernias. Although rare, it has the highest rate of mortality among them. The challenging clinical diagnosis is frequently missed due to the absence of specific symptoms and signs that usually appear in other inguino-abdominal hernias [1], [2]. The most common clinical presentation is intestinal obstruction of an unknown cause and the diagnosis is carried out with the aid of imaging methods such as CT or during exploratory surgery. The obturator hernia affects typically women, elderly, multiparous, emaciated and those with increased intra-abdominal pressure [2], [3]. Early diagnosis and surgical treatment are imperative and the delay is associated with a high mortality rate, increased complications rates and increased post-operative length of stay. The treatment can be made by the conventional laparotomy or by videolaparoscopy [4], [5]. The following accomplishes the SCARE criteria [6].

2. Case report

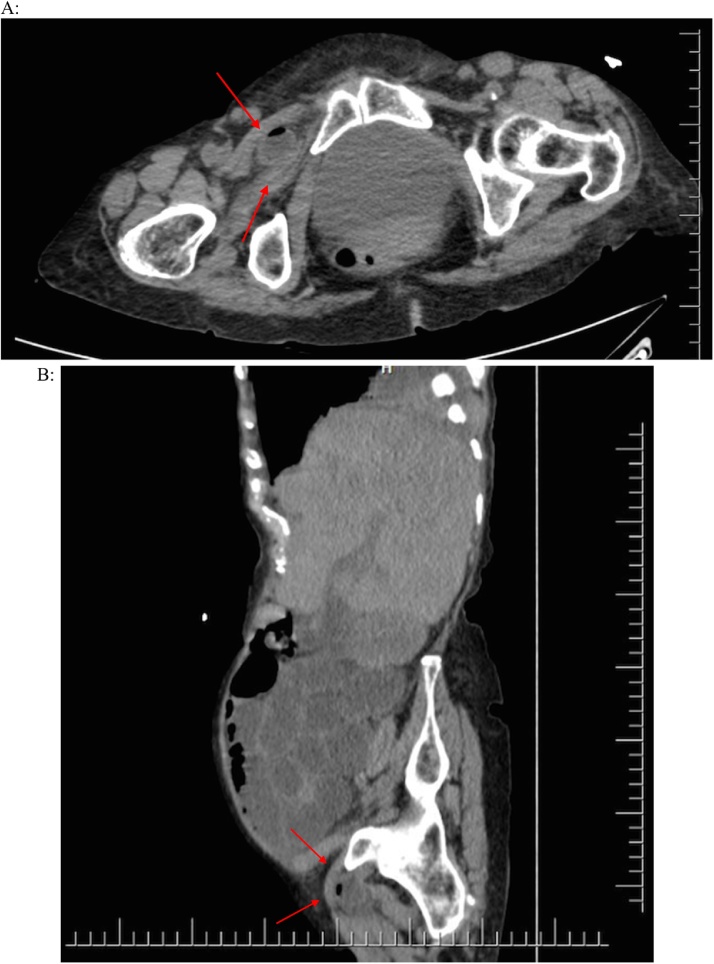

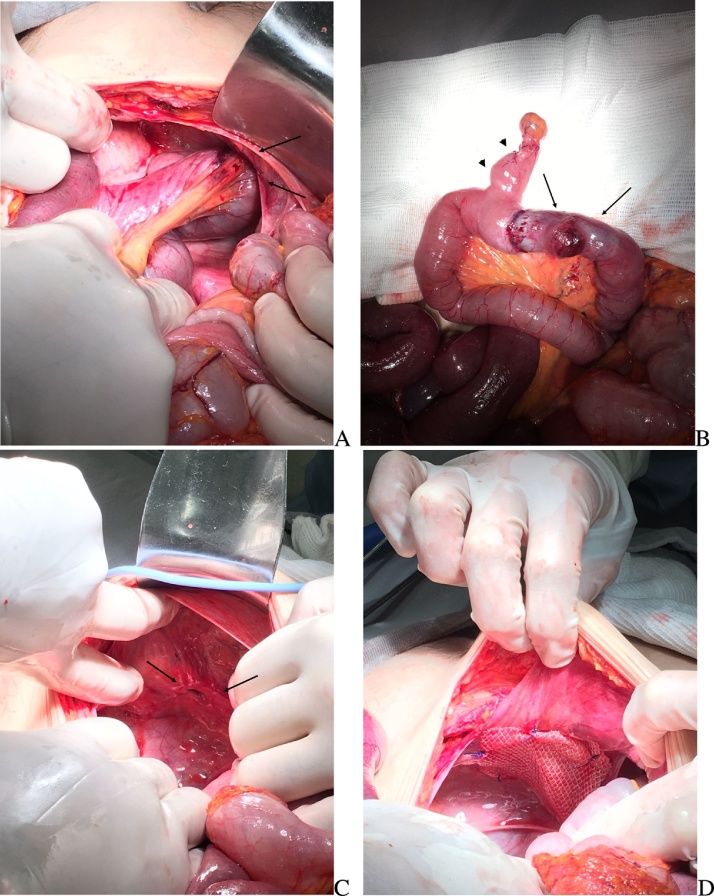

A 85-years-old female patient, was admitted into the emergency ward of the Unimed Hospital – Belo Horizonte-MG, with a 24 h evolution of diffuse abdominal pain and progressive abdominal distension, associated with persistent fecaloid vomit and irradiating pain to the right leg. She reported two similar and self-limited previous episodes. The first one was 4 years ago, and the most recent, 2 months ago. Patient had no previous history of any abdominal surgery. Physical examination revealed a prostrated and underweight female, with distended and tympanitic abdomen, diffuse pain to deep palpation and no signs of peritoneal irritation or inguino-abdominal hernias. Patient refused vaginal examination. She maintained haemodynamic and ventilatory stability. Nasogastric tube revealed fecaloid stasis. Laboratory exams showed leukopenia and an increased C-reactive protein level. Abdominal CT identified a herniation of the small bowel through the right obturator canal and an intestinal distension proximally (Fig. 1). Soon after, the patient was submitted to an infra-umbilical midline laparotomy that confirmed the diagnosis – right obturator hernia with ileal strangulation (Richter type). In addition, a Meckel diverticulum was detected (Fig. 2). Segmental enterectomy with primary end-to-end anastomosis and herniorrhaphy using a double-layer mesh for the closure of the obturator foramen were performed.

Fig. 1.

CT images: A) axial section and B) sagittal section – Showing a bowel segment with hydro-aerial levels through the right obturator canal (arrows).

Fig. 2.

Preoperative Images – A) herniation of ileal loops through the right obturator canal; B) Richter type hernia: impression in the ant mesenteric border of hernia content (arrows) associated with a Meckel diverticulum (arrow head); C) Obturator Foramen and D) Herniorrhaphia with double-layer mesh fixed with separate stitches.

3. Discussion

Obturator hernia is a rare condition accounting for less than 1% of all intra-abdominal hernias [7], [8]. It occurs when abdominal viscera traverses the obturator canal through which the nerve and the obturator vessels pass [9]. This type of hernia is 6–9 times more common in women because of their broader pelvis and greater transverse diameter [4], [10]. Other risk factors strongly related to obturator hernias are: elderly, emaciated, multiparous and patients with increased intra-abdominal pressure (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and intestinal constipation). Such factors can cause loosening of the pelvic floor that favors the onset of the hernia. It is less common on the left side because of the protection that sigmoid colon provides for the obturator canal [4] and can be bilateral in 20% of the cases. Obturator hernias are frequently associated with Richter hernia.

Accurate pre-operative diagnosis is difficult and occurs in less than 10% of the cases [11]. Specific signs and symptoms are not common. Vomiting, lower abdominal pain and symptoms of intestinal obstruction are clinical findings. The Howship-Romberg sign (described as pain exacerbated by extension, abduction and internal rotation of the hip due to compression of the obturator nerve) is considered pathognomonic, although it is reported to be present in only 15–50% of cases. In addition, the palpation of a mass by vaginal or rectal examination should alert the clinician to this diagnosis. Also, it may be discovered incidentally during laparoscopy for gynecological purposes [12]. CT scan is the most accurate imaging instrument for diagnosis in emergency room. It can help in pre-operative diagnosis, reducing the time between admission and treatment [4], [8]. Delayed diagnosis and treatment contribute to the need of enterectomy in 25%–50% of the cases [13].

Various techniques for the correction of the defect have been described in the literature. Lower midline laparotomy is the most common surgical management in emergency cases, although, recent studies indicate a high mortality rate, especially in elderly people with lung and heart conditions. Laparoscopic approach used in elective and emergency repairs, has lower post-operative complications rates and post-operative length of stay [10]. This approach, however, is restricted to stable patients with no previous laparotomies or significant abdominal distensions [4]. The majority of the repairs are done using meshes, but there are no studies, however, showing recurrence rates. It is not recommended for the repair of strangulated and perforated hernias. Ligature of the hernia sac is performed with continuous and nonabsorbable sutures and the closure of the foramen effected with biological or synthetic material [14].

4. Conclusion

The obturator hernia is a rare condition associated with a high rate of morbidity and mortality. Its diagnosis is considered a challenge because of its non-specific symptoms and signs and the low rate of occurrence compared to other abdominal hernias. CT is the most accurate imaging method for pre-operative diagnosis. Treatment is eminently surgical, either open or closed. Early diagnosis and surgical intervention are essential to lead to better outcomes for the patients.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of the article.

Sources of funding

None declared.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent

This patient was properly informed for her clinical information to be included in this publication.

Authors contribution

Sá NC: Study concept, drafting of the article, data collection, final publication decision.

Silva VCM: Study concept, drafting of the article, data collection, final publication decision.

Carreiro PRL: Study concept, analysis, final publication decision.

Matos Filho AS: Study concept, analysis, final publication decision.

Lombardi, IA: Study concept and translation.

Guarantors

Carreiro PRL and Matos Filho AS.

References

- 1.Peter R., Indiran V., Kannan K., Maduraimuthu P., Varadarajan C. Rare case of obturator hernia in a patient with Marfan’s syndrome. Hernia. 2014;18:439–442. doi: 10.1007/s10029-014-1216-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Killeen S., Buckley C., Smolerak S., Winter D. Small bowel obstruction secondary to right obturator hernia, Ireland. Surgery. 2013;157(January (1)):168. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2013.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan K.V., Chan C.K.O., Yau K.W., Cheung M.T. Surgical morbidity and mortality in obturator hernia: a 10-year retrospective risk factor evaluation. Hernia. 2013;18:387–392. doi: 10.1007/s10029-013-1169-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ng D.C.K., Tung K.L.M., Tang C.N., Li M.K.W. Fifteen-year experience in managing obturator hernia: from open to laparoscopic approach. Hernia. 2013;18:381–386. doi: 10.1007/s10029-013-1080-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sawayama H., Kanemitsu K., Okuma T., Inoue K., Yamamoto K., Baba H. Safety of polypropylene mesh for incarcerated groin and obturator hernias: a retrospective study of 110 patients. Hernia. 2013;18:399–406. doi: 10.1007/s10029-013-1058-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saetta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P., for the SCARE Group The SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;34:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pandey R., Maqbool A., Jayachandran N. Obturator hernia: a diagnostic challenge. Hernia. 2009;13:97–99. doi: 10.1007/s10029-008-0406-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hunt L., Morrison C., Lengyel J., Sagar P. Laparoscopic management of an obstructed obturator hernia: should laparoscopic assessment be the default option? Hernia. 2009;13:313–315. doi: 10.1007/s10029-008-0438-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Igari K., Ochiai T., Aihara A., Kumagai Y., Iida M., Yamazaki S. Clinical presentation of obturator hernia and review of the literature. Hernia. 2010;14:409–413. doi: 10.1007/s10029-010-0658-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodríguez-Hermosa J.I., Codina-Cazador A., Maroto-Genover A., Puig-Alcántara J., Sirvent-Calvera J.M., Garsot-Savall E., Roig-García J. Obturator hernia: clinical analysis of 16 cases and algorithm for its diagnosis and treatment. Hernia. 2008;12:289–297. doi: 10.1007/s10029-007-0328-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bergstein J.M., Condon R.E. Obturator hernia: current diagnosis and treatment. Surgery. 1996;119(February (2)):133–136. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(96)80159-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walid M.S., Heaton R.L. Pararectal and obturator hernias as incidental findings on gynecologic laparoscopy. Hernia. 2010;14(1):109–111. doi: 10.1007/s10029-009-0515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bur t.B.M, Cevasco M., Smink D.S. Classic presentation of a type II obturator hernia. Am. J. Surg. 2010;199(6 (June)):e75–e76. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shipkov C.D., Uchikov A.P., Grigoriadis E. The obturator hernia: difficult to diagnose, easy to repair. Hernia. 2004;8:155–157. doi: 10.1007/s10029-003-0177-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]