Abstract

Background

Breastfeeding is the optimal method for infant feeding. In the United States, 81.1% of mothers initiate breastfeeding; however, only 44.4% and 22.3% of mothers are exclusively breastfeeding at 3 and 6 months, respectively.

Research aim

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provides guidance and funding to state health departments to support strategies to improve breastfeeding policies and practices in the hospital, community, and worksite settings. In 2010, the Hawaii State Department of Health received support from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to launch the Baby-Friendly Hawaii Project (BFHP) to increase the number of Hawaii hospitals that provide maternity care consistent with the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding and increase the rate of women who remain exclusively breastfeeding throughout their hospital stay.

Methods

For this article, we examined the BFHP’s final evaluation report and Hawaii breastfeeding and maternity care data to identify the role of the BFHP in facilitating improvements in maternity care practices and breastfeeding rates.

Results

Since 2010, 52 hospital site visits, 58 trainings, and ongoing technical assistance were administered, and more than 750 staff and health professionals from BFHP hospitals were trained. Hawaii’s overall quality composite Maternity Practices in Infant Nutrition and Care score increased from 65 (out of 100) in 2009 to 76 in 2011 and 80 in 2013, and Newborn Screening Data showed an increase in statewide exclusive breastfeeding from 59.7% in 2009 to 77.0% in 2014.

Conclusion

Implementation and findings from the BFHP can inform future planning at the state and federal levels on maternity care practices that can improve breastfeeding.

Keywords: Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative, breastfeeding, Hawaii, maternity care practices, Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding

Background

Breastfeeding is the optimal method for infant feeding and promotes positive health outcomes for both mothers and infants (American Academy of Family Physicians, 2014). Experts recommend exclusive breastfeeding for about 6 months (American Academy of Pediatrics, 1997). In the United States, 81.1% of mothers initiate breastfeeding; however, only 44.4% and 22.3% of mothers are exclusively breastfeeding at 3 and 6 months, respectively (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2016).

Hospital maternity care practices can affect initiation and duration of breastfeeding (Fairbank et al., 2000). The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Support Breastfeeding (CDC, 2011) identified the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding (Ten Steps) (World Health Organization [WHO], 1989) as the standard of care for maternity care practices in hospitals. Established by the WHO and UNICEF, the Ten Steps are a set of evidence-based practices that, when used concurrently, improve the maternity care provided to patients (WHO, 1998) and yield better breastfeeding outcomes (DiGirolamo, Grummer-Strawn, & Fein, 2008; Kramer et al., 2001).

The CDC provides guidance and funding to state health departments to support the implementation of strategies to improve breastfeeding policies and practices in hospital, community, and worksite settings (Grummer-Strawn et al., 2013). In 2010, the Hawaii State Department of Health’s Healthy Hawaii Initiative (DOH-HHI) received technical assistance and funds from the CDC under the national initiative Communities Putting Prevention to Work (CPPW). With CPPW funding, the DOH-HHI launched the Baby-Friendly Hawaii Project (BFHP) to focus statewide efforts on improvements in maternity care practices. The DOH-HHI has committed state resources and has continued the project since the end of the 2-year CPPW funding.

The objective of the BFHP is to increase the number of Hawaii hospitals that provide maternity care consistent with the Ten Steps and increase the rate of women who remain exclusively breastfeeding throughout their hospital stay. Since 2010, the BFHP has provided funds, training, and technical assistance to all 11 birthing hospitals in Hawaii. For this article, we analyzed the BFHP CPPW Final Evaluation Report, Hawaii Newborn Screening Data, and the CDC’s national survey of Maternity Practices in Infant Nutrition and Care (mPINC) to identify the role of the DOH-HHI in facilitating project implementation, activities applied by hospitals, and key findings from the project.

Methods

Project Design and Setting

The BFHP was developed and led by DOH-HHI staff, including a project coordinator and project consultant. The project coordinator provided project management, corresponded with the CDC, and worked closely with the project consultant to implement the BFHP. The project consultant, an expert in maternity care practices and policies, reviewed hospital policies and practices, conducted site visits, and provided guidance to hospitals through trainings and ongoing technical assistance. To improve project implementation, the BFHP contracted with the Healthy Children Project, Inc. The Healthy Children Project, Inc. facilitated Learn to Teach the 20 Hour Course (see Table 1). The project also developed relationships with the Hawaii Breastfeeding Coalition–Breastfeeding Hawaii, the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children, and Baby-Friendly USA. These agencies participated in some of the project activities, provided support and information, and were updated regularly on the progress of the BFHP.

Table 1.

Descriptions of Training and Technical Assistance for the Baby-Friendly Hawaii Project

| Event | Facilitator | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Learn to Teach the 20 Hour Course | Healthy Children Project, Inc. | The Healthy Children Project, Inc. is a provider of lactation management education for health care providers. Learn to Teach the 20 Hour Course is designed as a train-the-trainer class to teach the curriculum that meets the Baby-Friendly staff training requirement. All of the hospitals were invited to send staff to be trained. Hospital staff trained through this course were designated as hospital champions. |

| Nurturing in a Nutshell | Baby-Friendly Hawaii Project (project consultant) | The Nurturing in a Nutshell course provided information on the basic physiology of birth, attachment, and breastfeeding. The course provided opportunities to discuss, practice, and observe various breastfeeding skills, including best practices surrounding birth and the use of the SOFT approach. The SOFT approach consists of key messages for families: (S) skin-to-skin care, (O) open eye-to-eye (infant cues), (F) fingertip touch (the array of innate behaviors), (F) feeding patterns (exclusivity), and (T) time together (rooming-in). |

| Train-the-trainer | Baby-Friendly Hawaii Project (project coordinator and project consultant) | Train-the-trainer workshops reconvened the trainers group that had participated in the Learn to Teach the 20 Hour Course training. These sessions provided a venue for them to share successes and barriers and to learn and practice creative techniques for training staff resistant to change and provided tools to empower change and lead hospital teams through the implementation of the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding. |

| Mock Baby-Friendly visits | Baby-Friendly Hawaii Project (project coordinator and project consultant) | The mock visits were designed to assess how well the hospitals were doing in preparation for the designation visit from Baby-Friendly USA and to provide feedback to the hospitals on how to prepare staff for the official visits and recommendations for additional changes. Three Baby-Friendly Hawaii Project hospitals participated in the mock visits. |

| Train-the-trainer technical assistance conference calls | Baby-Friendly Hawaii Project (project coordinator and project consultant) | The Baby-Friendly Hawaii Project facilitated off-site technical assistance and networking conference calls to nurses or trainers who were interested in sharing lessons learned with other nurses/staff in the state. |

| General technical assistance | Baby-Friendly Hawaii Project (project consultant) | General technical assistance included informal communication through phone or email, on-site visits to participating hospitals, and one-on-one conference calls to follow up with hospital representatives interested in garnering further support in improving maternity care practices. |

For the project design, the BFHP employed six strategies based on a model developed by the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene: engage hospitals, enlist support, recruit champions, assess hospitals, conduct site visits and trainings, and monitor outcomes (Boyd, Hackett, & Magid, 2011). The project consultant also used the SOFT approach (see Table 1) and the 10 Steps, 10 Years, and 10 Hospitals: The San Bernardino County Baby-Friendly Story video as guides for technical assistance and trainings (Melcher, 2010).

On behalf of the BFHP, the director of health at the Hawaii State Department of Health sent letters to the chief executive officers of all birthing hospitals in Hawaii (n = 11) to recruit them for the BFHP. The BFHP also contacted nurse managers at the hospitals to assess interest and discuss project offerings, such as staff training and ongoing support if they chose to apply for Baby-Friendly designation.

Four Hawaii hospitals initially agreed to participate in the BFHP and pursue designation. The remaining Hawaii hospitals were willing to work on the Ten Steps but were reluctant to engage in the comprehensive and time-intensive Baby-Friendly designation process. The Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative is an evidence-based program that recognizes hospitals and birthing centers that offer an optimal level of care for infant feeding and mother–baby bonding (Baby-Friendly USA, 2016). Hospitals that are recognized as Baby-Friendly have met the required Ten Steps criteria, have completed the 4-D Pathway, and follow the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes. The 4-D Pathway provides facilities with structure, guidance, and tools to aid them in their journey to achieving Baby-Friendly designation. Recognizing that the BFHP could fill a major gap in improving maternity care practices, the BFHP reframed their approach to primarily focus on implementing the Ten Steps without having to work toward Baby-Friendly designation. With this adjustment, all 11 Hawaii maternity hospitals agreed to participate in the BFHP.

Project Sample

Populations targeted for the BFHP were registered nurses, lactation consultants, and other hospital staff, as well as expectant mothers at all 11 Hawaii maternity hospitals during the project period.

Data Collection and Analysis

For this article, the BFHP CPPW Final Evaluation Report was used to examine BFHP training and technical assistance. BFHP training and technical assistance (see Table 1) was primarily conducted by the project coordinator and project consultant. Trainings consisted of Learn to Teach the 20 Hour Course, Nurturing in a Nutshell, and train-the-trainer workshops. Training participants comprised registered nurses, lactation consultants, and other hospital staff. A database was developed to track the number of attendants for trainings. Technical assistance was often informal and ongoing and consisted of conference calls, one-on-one calls, site visits, and mock Baby-Friendly visits.

Each hospital identified staff to serve as “champions” during the BFHP. There were no specific criteria for being a champion; however, managers at each hospital were responsible for identifying members of their staff as champions. Selected champions were designated as trainers and participated in Learn to Teach the 20-Hour Course (WHO, 2009) and the train-the-trainer workshops. Champions went on to train staff at their respective hospitals and had the opportunity to influence and improve hospital practice and policy. Most BFHP hospitals had at least two champions.

The BFHP had ongoing conversations with hospitals to inform them of current hospital practices, training needs, and priorities. The project consultant developed an informal Ten Step assessment survey to monitor hospital progress over time. The survey served as a guide for the project consultant and hospitals to identify facilitators and barriers to meeting each of the Ten Steps. Technical assistance was administered by the project consultant when necessary.

Since all birthing hospitals in Hawaii participated in the BFHP, data from two statewide surveillance systems were used to monitor changes over time and capture changes in maternity care practices and breastfeeding outcomes. The BFHP used the CDC’s mPINC scoring system to monitor changes in Hawaii maternity care practices before and during the project period (mPINC scores from 2009mPINC scores from 2011, and 2013). Developed in 2007 by the CDC, mPINC is a hospital selfreported survey that monitors breastfeeding-associated maternity practices among all U.S. birthing facilities (CDC, 2015). A state’s mPINC score represents the mean overall score for each hospital that submits a survey (0 = practices unsupportive of breastfeeding; 100 = practices supportive of breastfeeding) (Li et al., 2014). Seven domains are assessed in the survey, including labor and delivery care, feeding of breastfed infants, breastfeeding assistance, contact between mother and infant, facility discharge care, staff training and education, and structural and organizational aspects of care delivery.

The BFHP worked with an epidemiologist to obtain Hawaii Newborn Screening breastfeeding data from 2009 to 2014 (Hayes, 2015). Newborn Screening is a mandatory Hawaii state health service that surveys all newborns’ health after birth. The screening form captures breastfeeding of infants, which is assessed by a health professional 24 hours postpartum to discharge. Health professionals are required to indicate how the newborn is being fed at the time (breastfeeding, lactose formula, soy formula, tube feeding, or preprocedural fasting). Feeding data are classified into three categories: exclusive breastfeeding, mixed fed with human milk and formula, or formula only (New STEPs, 2013).

Results

Several key findings were observed during and after project implementation.

Trainings, Site Visits, and Technical Assistance

The BFHP provided 58 trainings, 52 hospital site visits, and ongoing technical assistance during the project period. As a result, more than 750 staff and health professionals from BFHP hospitals were trained.

mPINC and Newborn Screening Data

Hawaii’s overall quality composite mPINC score increased from 65 (out of 100) in 2009 to 76 in 2011 and 80 in 2013. In 2009, 9 of the 11 hospitals participated in the mPINC survey; in 2011, 7 of the 11 hospitals participated in the mPINC survey; and in 2013, 11 of 11 hospitals participated in the mPINC survey (CDC, 2015).

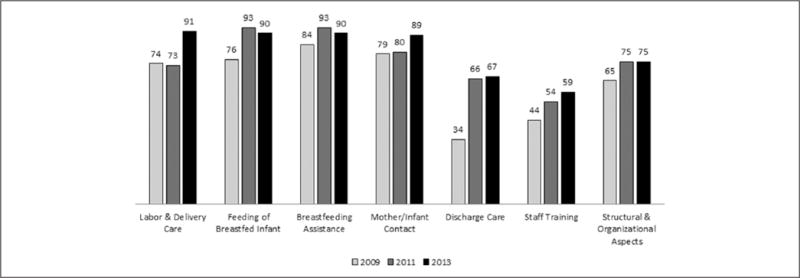

All seven domains experienced an increase in score (see Figure 1): labor and delivery care increased by 17, feeding of breastfed infant increased by 14, breastfeeding assistance increased by 6, mother–infant contact increased by 10, discharge care increased by 33, staff training increased by 15, and structural and organization aspects increased by 10.

Figure 1.

Hawaii mPINC Score by Domain and Year.

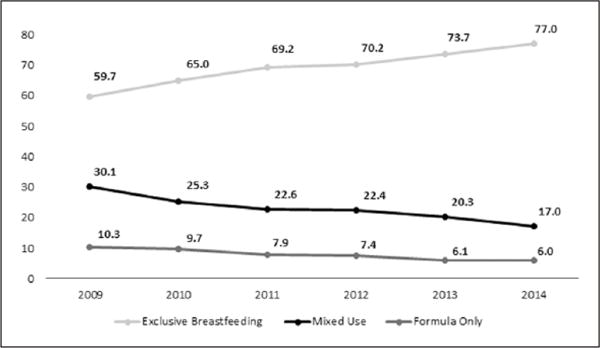

Newborn Screening Data (see Figure 2) showed an increase in statewide exclusive breastfeeding from 59.7% in 2009 to 77.0% in 2014, with a concurrent decrease in exclusive formula feeding from 10.3% in 2009 to 6.0% in 2014. Mixed use (breastfeeding and formula) saw a decrease from 30.1% in 2009 to 17.0% in 2014 (Hayes, 2015).

Figure 2.

Breastfeeding Rates From Newborn Screening Data, 2009–2014.

Baby-Friendly Designation

Although the BFHP did not require hospitals to become Baby-Friendly, several hospitals took steps toward designation. As of February 26, 2016, four hospitals had registered with Baby-Friendly USA’s 4-D Pathway to designation, and three of the four completed a mock Baby-Friendly visit with the project consultant. Of these four hospitals, three had their designation assessments and received Baby-Friendly designation.

Discussion

This article describes some activities and results from the BFHP in supporting maternity care practices in birthing facilities. Findings from this article may generate ideas for other state health departments working to improve maternity care practices in their state.

Our analysis shows that Hawaii experienced substantial improvement in hospital maternity care practices and breastfeeding rates. From 2009 to 2011, Hawaii’s mPINC score increase was the greatest among all states and U.S. territories reporting (CDC, 2015). Although both the mPINC and Newborn Screening Data cannot be linked to hospital practices at the individual level and may be attributed to multiple factors within varying settings, it is important to note that the improvements shown on these two statewide surveillance systems occurred parallel to BFHP implementation. Because all birthing facilities in Hawaii participated in the BFHP and implemented evidence-based maternity care practices, it is likely that these substantial changes in mPINC score and Newborn Screening are at least partially attributable to the statewide efforts to improve maternity care practices through the BFHP.

An important observation from this report is that the BFHP implemented a statewide evidence-based project that can be replicated. The project was developed using the Ten Steps and lessons learned from other states’ efforts. The BFHP did not create a first-of-its-kind project but instead implemented successful facets of other programs, such as the SOFT approach (see Table 1), and used an evidence-based foundation. Across the United States, several local and state health departments have implemented similar methods and programs to improve maternity care practices (Freney, Johnson, & Knox, 2016; Oklahoma State Department of Health, 2013). Accordingly, some key activities used within the BFHP can be duplicated, and similar program successes may be achieved by other states.

The BFHP has been supported through several mechanisms, such as the CDC’s Communities Putting Prevention to Work program, the Hawaii State Department of Health’s Healthy Hawaii Initiative Tobacco Settlement Special Fund, and state general funds. To promote program sustainability, the BFHP focused on the implementation of breastfeeding hospital policies. As staff change, having a written breastfeeding policy can help continue improvements made through programs such as the BFHP.

Like Hawaii, each state has a health department uniquely positioned to implement programs that support and improve maternity care practices and breastfeeding rates. As indicated by the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (Boyd et al., 2011), state health departments are not in competition with hospitals, allowing them to work across hospital systems to make improvements in maternity care practices. State health departments can serve as unbiased and independent entities, which can facilitate trust, promote communication, and improve the reach of statewide or local improvements in maternity care.

Over the past decade, state and local health departments and federal agencies have invested in improvements in maternity care practices through various mechanisms such as hospital collaboratives (Whalen, Kelly, & Holmes, 2015), breastfeeding-friendly recognition programs (Mannel & Bacon, 2014), or Baby-Friendly initiatives (Karol et al., 2016). A better understanding of activities developed by programs such as Hawaii’s BFHP can offer funding organizations and other states ideas for implementation of future work to support breastfeeding. Depending on a state’s context, they may want to focus on developing key partnerships that result in changes or actions affecting hospitals across the state, creating a synergized Baby-Friendly or breastfeeding-friendly program that offers financial assistance to hospitals, or providing technical assistance, training, and general education to improve maternity care practices.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, the BFHP is a program for improvements in maternity care practices that has been implemented only in Hawaii birthing facilities. Although findings from this study may generate ideas for similar programs, hospitals participating in the BFHP are not representative of all birthing facilities and thus some BFHP activities may not be generalizable. Second, the mPINC survey is a census of all hospitals in the United States with registered maternity beds. Since the mPINC is a hospital self-reported survey, responses may not accurately represent a hospital’s maternity care practices. However, the individual responsible for conducting the survey in a hospital is identified as the person most knowledgeable about the relevant practices. Last, our findings did not capture activities for improvements in Hawaii maternity care practices that are being conducted outside of BFHP funding and guidance. Therefore, findings may be attributed to multiple factors within varying settings throughout the state.

Conclusion

In summary, the DOH-HHI developed the BFHP to focus statewide efforts on improvements in maternity care practices and breastfeeding rates. The BFHP used the Ten Steps and a practice-based model to provide funds, trainings, and technical assistance to all birthing hospitals in Hawaii. Since 2010, Hawaii has experienced improvement in both mPINC scores and breastfeeding rates. Project implementation and findings can inform future planning at the state and federal levels on approaches that improve breastfeeding through maternity care practices.

Key Messages.

This article is the first to analyze a state health department-led maternity care practices program in all birthing hospitals.

Hawaii’s Maternity Practices in Infant Nutrition and Care score increased from 65 in 2009 to 80 in 2013. Hawaii Newborn Screening Data showed an increase in statewide exclusive breastfeeding from 59.7% in 2009 to 77.0% in 2014.

Findings can inform future planning at the state and federal levels on approaches that improve breastfeeding through maternity care practices.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the HDOH Newborn Metabolic Screening (NMS) program for collecting, analyzing, and providing the NMS data used in this article. Analysis of the NMS data was provided by Dr. Donald Hayes, the CDC-assigned epidemiologist at the HDOH, Family Health Services Division.

Funding

The Baby-Friendly Hawaii Project was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Communities Putting Prevention to Work program and the Hawaii Department of Health’s Healthy Hawaii Initiative Tobacco Settlement Special Fund. Award number: 3U58DP001962-01S2.

Footnotes

CDC Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- American Academy of Family Physicians. Breastfeeding, family physicians supporting (Position paper) 2014 Retrieved November 23, 2015, from http://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/breastfeeding-support.html.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 1997;100(6):1035–1039. doi: 10.1542/peds.100.6.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baby-Friendly USA. Baby-Friendly USA: The gold standard of care. 2016 Retrieved December 1, 2015, from http://www.babyfriendlyusa.org/

- Boyd L, Hackett M, Magid E. Health departments helping hospitals: A New York City breastfeeding case study. Breastfeeding Medicine. 2011;6(5):267–269. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2011.0078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The surgeon general’s call to action to support breastfeeding. 2011 Retrieved November 23, 2015, from http://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/promotion/calltoaction.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Maternity Practices in Infant Nutrition and Care (mPINC) survey. 2015 Retrieved October 5, 2015, from http://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/mpinc.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Immunization Survey. 2016 Retrieved August 3, 2016, from http://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/nis_data/index.htm.

- DiGirolamo A, Grummer-Strawn L, Fein S. Effect of maternity-care practices on breastfeeding. Pediatrics. 2008;122(Suppl. 2):S43–S49. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1315e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairbank L, O’Meara S, Renfrew MJ, Woolridge M, Sowden AJ, Lister-Sharp D. A systematic review to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions to promote the initiation of breastfeeding. Health Technology Assessment. 2000;4(25):1–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freney E, Johnson D, Knox I. Promoting breastfeeding-friendly hospital practices: A Washington state learning collaborative case study. Journal of Human Lactation. 2016;32(2):355–360. doi: 10.1177/0890334415594381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grummer-Strawn LM, Shealy KR, Perrine CG, MacGowan C, Grossniklaus DA, Scanlon KS, Murphy PE. Maternity care practices that support breastfeeding: CDC efforts to encourage quality improvement. Journal of Women’s Health. 2013;22:107–112. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2012.4158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes D. Newborn metabolic screening breastfeeding data request, 2009–2014. Honolulu, HI: Hawaii Department of Health, Newborn Metabolic Screening Program; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Karol S, Tah T, Kenon C, Meyer J, Yazzie J, Stephens C, Merewood A. Bringing Baby-Friendly to the Indian Health Service: A systemwide approach to implementation. Journal of Human Lactation. 2016;32(2):369–372. doi: 10.1177/0890334415617751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer MS, Chalmers B, Hodnett ED, Sevkovskaya Z, Dzikovich I, Shapiro S, Hesling E. Promotion of Breastfeeding Intervention Trial (PROBIT): A randomized trial in the Republic of Belarus. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;285(4):413–420. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.4.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CM, Li R, Ashley CG, Smiley JM, Cohen JH, Dee DL. Associations of hospital staff training and policies with early breastfeeding practices. Journal of Human Lactation. 2014;30(1):88–96. doi: 10.1177/0890334413484551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannel R, Bacon N. Hospital efforts to improve breastfeeding outcomes: Becoming Baby-Friendly in Oklahoma. Journal of the Oklahoma State Medical Association. 2014;107(9–10):485–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melcher C. Continuing the unique work of the Perinatal Services Network. 2010 Retrieved January 13, 2016, from http://carolmelcher.com/assets/soft_workbook.pdf.

- New STEPs. Hawaii state profile: Screening card image. 2013 Retrieved February 17, 2016, from https://data.newsteps.org/newsteps-web/stateProfile/input.action.

- Oklahoma State Department of Health. Oklahoma hospitals work to be designated as Baby-Friendly. 2013 Retrieved February 17, 2016, from the National Public Health Information Coalition website: http://www.nphic.org/Content/Awards/2013/OrgSubmissions/NPHIC_2013_Entry_-_OK_-_Baby-Friendly_Hospitals.pdf.

- Whalen BL, Kelly J, Holmes AV. The New Hampshire Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding collaborative: A statewide QI initiative. Hospital Pediatrics. 2015;5(6):315–323. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2014-0104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Protecting, promoting and supporting breast-feeding: The special role of maternity services. 1989 Retrieved December 1, 2015, from http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/infantfeeding/9241561300/en/

- World Health Organization. Evidence for the ten steps to successful breastfeeding. 1998 Retrieved January 1, 2016, from http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/9241591544/en/

- World Health Organization. Breastfeeding promotion and support in a Baby-Friendly hospital: A 20-hour course for maternity staff. 2009 Retrieved November 23, 2015, from http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/infantfeeding/bfhi_train-ingcourse_s3/en/