Abstract

Background and purpose

Hemiarthroplasty is the most common treatment in elderly patients with displaced femoral neck fracture. Prosthetic joint infection (PJI) is a feared complication. The infection rate varies in the literature, and there are limited descriptive data available. We investigated the characteristics and outcome of PJI following hemiarthroplasty over a 15-year period.

Patients and methods

Patients with PJI were identified among 519 patients treated with hemiarthroplasty for a femoral neck fracture at Oslo University Hospital between 1998 and 2012. We used prospectively registered data from previous studies, and recorded additional data from the patients’ charts when needed.

Results

Of the 519 patients, we identified 37 patients (6%) with early PJI. 20 of these 37 patients became free of infection. Soft tissue debridement and retention of implant was performed in 35 patients, 15 of whom became free of infection with an intact arthroplasty. The 1-year mortality rate was 15/37. We found an association between 1-year mortality and treatment failure (p = 0.001). Staphylococcus aureus and polymicrobial infection were the most common microbiological findings, each accounting for 14 of the 37 infections. Enterococcus spp. was found in 9 infections, 8 of which were polymicrobial. There was an association between polymicrobial infection and treatment failure, and between polymicrobial infection and 1-year mortality.

Interpretation

PJI following hemiarthroplasty due to femoral neck fracture is a devastating complication in the elderly. We found a high rate of polymicrobial PJIs frequently including Enterococcus spp, which is different from what is common in PJI after elective total hip arthroplasty.

Hemiarthroplasty is the most common treatment for elderly patients with displaced femoral neck fractures (Bhandari et al. 2005). The incidence of prosthetic joint infection (PJI) in hemiarthroplasty after femoral neck fracture varies from 2% to 17% (Ridgeway et al. 2005, Cumming and Parker 2007, Merrer et al. 2007, Garcia-Alvarez et al. 2010, Bucheit et al. 2015), and infection rates are consistently higher than after elective total hip arthroplasty (THA; reported to be around 1%) (Phillips et al. 2006, Kurtz et al. 2008). PJI can lead to serious deterioration in patients’ daily function and quality of life, yet the literature on this subject is limited. The optimal surgical and antimicrobial treatment for PJI after hemiarthroplasty because of fracture is not known, and it may be different from that for PJI following primary THA in elective patients (Lora-Tamayo et al. 2013).

In early PJI, soft tissue debridement with retention of the prosthesis is an attractive option; the success rate has been reported to be 65–75% (Tsukayama et al. 1996, Barberan et al. 2006, Westberg et al. 2012, del Toro et al. 2014). In PJI after hemiarthroplasty, however, a lower success rate has been reported (44%) (del Toro et al. 2014).

In this study, we examined the characteristics and outcome of PJI following hemiarthroplasty due to femoral neck fracture. We also tried to identify possible risk factors for treatment failure.

Patients and methods

Patients who developed PJI after operation with hemiarthroplasty due to femoral neck fracture were identified from 5 consecutive clinical studies on hip fractures conducted at Oslo University Hospital from 1998 through 2012 involving 519 patients (Frihagen et al. 2007a, 2007b, Figved et al. 2009, Westberg et al. 2013, Watne et al. 2014). 3 of the studies were randomized clinical trials using wide inclusion criteria—including patients with cognitive failure. The other studies included consecutive patients over a period of time. Demographic data were registered prospectively in all studies. For the present study, additional data regarding PJI were recorded retrospectively from the patient charts. Follow-up was until death, or it ended at the time of data collection (December 2015).

Data on patient-dependent variables known to be a potential risk for PJI were registered: age, sex, body mass index (BMI), diabetes mellitus, dementia, and ASA score. Preoperative waiting time, prophylactic antibiotic regimen, microbiology results, infection treatment strategy, outcome of PJI treatment, and mortality were also registered. Preoperative waiting time was defined as the time from admission to the emergency department until surgery. Treatment success was defined as being free of infection at the last control or at the time of death.

PJI was diagnosed according to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) definition of deep incisional surgical site infection (Mangram et al. 1999). Infections were categorized as early or late, depending on whether the symptoms appeared before or after 4 weeks following the primary surgery (Tsukayama et al. 1996).

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 23. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical variables and t-tests were used for continuous variables. Logistic regression analysis was used for adjusted analysis of risk. A significance level of 5% was chosen.

Ethics

All patients were included in studies approved by the regional ethics committee or by the hospital’s data protection official for research.

Potential conflicts of interests

No competing interests declared.

Results

Patient characteristics

519 patients operated with hemiarthroplasty for a femoral neck fracture were included in the 5 original studies. In these patients, we identified 37 PJIs (6%) (Table 1), 34 of which were classified as being early. 3 patients who showed signs of infection within 5 weeks after the index surgery were also included in the analyses.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of 37 patients with femoral neck fracture who developed acute PJI after hemiarthroplasty. Data are number of patients unless otherwise stated

| Age, median (range) | 81 (49–95) |

| ASA score III/IV | 24 |

| Body mass index, median (range)a | 24 (17–37) |

| Female sex | 28 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 5 |

| Dementia | 10 |

Data missing for 7 patients.

All patients had received a bipolar cemented hemiarthroplasty using cement with gentamicin. 33 patients received a Charnley stem (DePuy International Ltd., Leeds, UK). Other stems were used in 4 cases. Experienced residents performed all surgeries.

Antibiotic prophylaxis was given to all patients during surgery. Cephalotin (2 g) was given intravenously to 34 patients. 2 patients were given clindamycin (600 mg) due to penicillin allergy and 1 patient was given cefuroxime (1.5 g). Most patients received 4 doses of antibiotics, but 11 of the 37 patients received only 2 or 3 doses. The first dose was given during the recommended interval of 15–60 min before surgery in 11 cases. In 25 of 37 patients, the prophylaxis was not administered within the recommended time limits. 18 patients received the first dose 0–15 min before the start of surgery and 7 patients received the first dose after the surgery had started. Data on antibiotic prophylaxis were missing for 1 patient.

Treatment

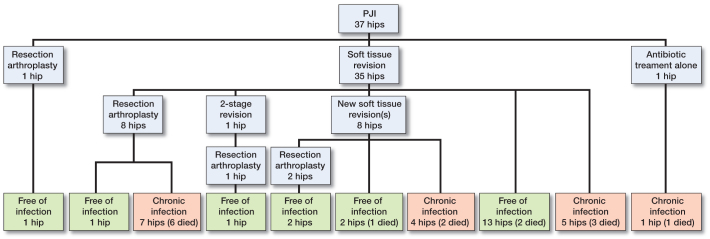

All but 2 infections (35 of 37) were treated with soft tissue debridement and retention of the implant (Figure 1). Median time between index surgery and first reoperation for infection was 18 days (range: 8–42), while the median time from first sign of infection until reoperation was 3 days (range: 0–12). The mean duration of symptoms was 3.6 days in the success group and 2.6 days in the failure group (p = 0.3). The soft tissue revisions were performed by excision of the wound margins, removal of necrotic tissue and debris, and then saline lavage. The modular components were changed, and either gentamicin chains or gentamicin-containing collagen sponges were placed in the joint before closing. In 2 cases, the modular components were not replaced in the primary soft tissue revision. An intravenous antibiotic regimen with cloxacillin—alone or in combination with vancomycin—was given until the microbiological findings were known.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of treatment and outcome in 37 hips with early PJI.

Antibiotic therapy was not standardized and was given according to the microbiological findings. In 3 patients with Staphylococcus aureus infections, a rifampicin combination regimen was given.

4 patients were given life-long suppression antibiotic therapy after 1 (n = 2) or 2 (n = 2) soft tissue revisions.

Outcome

20 of the 37 patients were free of infection at the last follow-up. Of the 35 patients who were treated with soft tissue debridement and retention of the implant, 15 became free of infection with the arthroplasty in place. This included 2 patients who needed a second debridement. 6 of 8 patients who were treated with resection arthroplasty after an unsuccessful soft tissue revision died during the period of antibiotic treatment. 12 resection arthroplasties were performed, and 5 of these patients became free of infection (Figure 1).

We found a 1-year mortality rate of 15/37. There was a statistically significant association between treatment failure and one-year mortality (12/17 in the failure group vs. 3/20 in the infection free group (RR =5, 95% CI: 2–14; p = 0.001)). In a bivariate analysis, increasing age, treatment failure, and polymicrobial infection were found to be statistically significant risk factors for 1-year mortality. In a logistic regression analysis, these factors remained statistically significant, but with wide confidence intervals (Table 2).

Table 2.

Bivariate and logistic regression analyses

| Bivariate analysis | Alive at 1 year | Dead by 1 year | Mean difference or relative risk (95% CI) | p-value | Multivariate analysis | OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Sex | 0.1 (0.0–1.9) | 0.1 | ||||

| Male | 4/9 | 1.1 (0.5–3.8) | 0.8 | ||||

| Female | 11/28 | ||||||

| Age | 79 | 85 | 6.1 (1.3–11) | 0.01 | Age | 1.5 (1.1–2.1) | 0.03 |

| Chronic infection | Chronic infection | 15 (1.6–135) | 0.02 | ||||

| Yes | 3/20 | ||||||

| No | 12/17 | 4.7 (1.6–14) | 0.001 | ||||

| Poly-microbial PJI | Poly-microbial PJI | 23 (1.4–372) | 0.03 | ||||

| No | 6/23 | ||||||

| Yes | 9/14 | 2.5 (1.1–5.4) | 0.02 |

We found similar rates of treatment success in the different time periods (1998–2002: 7/12; 2003–2007: 4/9; 2008–2012: 9/16; p = 0.8).

Microbiology

Polymicrobial infection and single-microbe infection with Staphylococcus aureus were the most common findings, each accounting for 38% (Table 3). Only 2 of the polymicrobial infections were identical regarding culture results. Enterococcus spp. was found in 8 of 14 polymicrobial PJIs (Table 4). Staphylococcus aureus was the most frequently isolated microorganism altogether, occurring in 23 hips, followed by Staphylococcus epidermidis in 16 hips. 10 of 16 of the S. epidermidis isolates were methicillin-resistant (MRSE). Gram-negative microorganisms were found in 5 hips. We did not find any cases with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

Table 3.

Microbiological findings in 37 prosthetic joint infections

| Infecting organism(s) | Number of cases |

|---|---|

| Staphylococcus aureus | 14 |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | 1 |

| MRSEa | 5 |

| Enterococcus spp. | 1 |

| Polymicrobial infection | 14 |

| Culture-negative infection | 2 |

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis.

Table 4.

Details of 14 polymicrobial PJIs

| Infecting organisms | |

|---|---|

| 1 | S. epidermidis + Enterococcus sp. |

| 2 | S. aureus + S. epidermidis + Enterococcus sp. |

| 3 | S. aureus + S. epidermidis + Enterococcus sp. |

| 4 | S. epidermidis + Enterococcus sp. |

| 5 | S. aureus + Enterococcus sp. + Corynebacterium sp. + |

| Acinetobacter sp. | |

| 6 | S. aureus + MRSE + Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

| 7 | MRSE + Enterococcus sp. |

| 8 | S. aureus + S. epidermidis + Enterococcus sp. + Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

| 9 | S. aureus + Enterococcus sp. + Corynebacterium sp. + Peptostreptococcus + Morganella morganii |

| 10 | S. aureus + Pneumococcus |

| 11 | MRSE + Propionibacterium acnes |

| 12 | Streptococcus mitis + MRSE + Corynebacterium sp. |

| 13 | S. aureus + MRSE |

| 14 | S. aureus + Streptococcus |

In 14 of the infections, 1 or more of the bacterial strains were gentamicin-resistant. All of the Staphylococcus aureus strains were sensitive to gentamicin, but a large proportion of the Staphylococcus epidermidis strains (3/6) and Enterococcus spp. strains (4/9), and almost all of the MRSE strains (8/10) were gentamicin-resistant. There was no association between gentamicin resistance and outcome of infection.

There were more failures in the polymicrobial infections than in single-microbe infections, but the difference was not statistically significant (9/14 vs. 8/23, p = 0.08). The polymicrobial group had a higher 1-year mortality rate than the patients with single-microbe PJIs: 9/14 vs. 6/23, respectively (RR =3, 95% CI: 1.1–5.4; p = 0.02). We did not find that the presence of 1 specific microbe was associated with treatment failure.

Late infections

In addition to the 37 early PJIs described, we identified 2 patients with late infection occurring after 0.3 and 2 years, respectively. Both were polymicrobial infections, 1 with S. epidermidis/streptococci and 1 with MRSE/Corynebacterium spp. The first patient was initially treated with antibiotics, and then successfully with a one-stage revision. The other patient had 2 soft tissue revisions, followed by a resection arthroplasty. This patient required life-long antibiotics and had persistent signs of infection until she died.

Discussion

In this study of 519 hip-fracture patients, 39 (6%) developed PJI. The 1-year mortality rate was 41%, and we found an association between 1-year mortality and treatment failure. The antimicrobial prophylaxis was inadequately administered in surprisingly many cases (25 of 37 patients).

The baseline characteristics regarding age, sex, BMI, dementia, and diabetes in the study group appear to be rather similar to those in the general population of patients with femoral neck fracture. But the numbers with ASA score III/IV (two-thirds) was slightly higher in this material than has been reported in uninfected patients in the original studies, ranging from 53% to 61% (Frihagen et al. 2007a, 2007b, Figved et al. 2009, Westberg et al. 2013, Watne et al. 2014). We did not find that a higher ASA score was a predictor of treatment failure, even though increasing comorbidity has been reported to be a risk factor for development of PJI (Ridgeway et al. 2005).

According to the literature, antibiotic prophylaxis should be given 15–60 min prior to incision to ensure high concentrations of antibiotics in the tissue during surgery (Stéfansdóttir et al. 2009a, Swierstra et al. 2011). It is not unlikely that delayed prophylaxis had an impact on the PJI rate in our material, but as we had no control group, we cannot verify this. Inadequate timing of prophylaxis has also been described by others. In a study from the Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register, only 57% of the patients had adequate timing of the prophylaxis (Stéfansdóttir et al. 2009a). A formal verbal surgical checklist (“safe surgery”) has now been implemented, and we believe that this will ensure a more correct antibiotic administration (Haynes et al. 2009).

The infection rate varied over the years, with a mean of 6% for the whole period. This is in line with other reports (Ridgeway et al. 2005, Cumming and Parker 2007, Merrer et al. 2007, Garcia-Alvarez et al. 2010, Buchheit et al. 2015). We found an increased number of PJIs in the period 2008–2009. The study performed in this time period included a consecutive series of patients, while in 3 of the other studies patients were included in randomized clinical trials and selected by stricter inclusion criteria. Patients with ongoing infectious diseases, known arthritis, or unable to walk, were excluded—as well as young patients. Patients with a higher risk of PJI could therefore have been excluded. However, even though the peak incidence of PJI may have been due to a wider inclusion of patients, we believe that the peak incidence represents a normal variation over time.

Treatment

The success rate of soft tissue debridement and retention of the implant was poor (15/35). Similar results have also been reported by others (44%) (del Toro et al. 2014). Studies conducted on patients with PJI following elective primary THA have shown better results (65–75%) (Tsukayama et al. 1996, Barberan et al. 2006, Westberg et al. 2012, del Toro et al. 2014). Lora-Tamayo et al. (2013) found that infected THA and infected hemiarthroplasties had different characteristics, but they reported a success rate of 63% in hemiarthroplasty PJIs. In that series, uncemented implants were extensively used, and the implant was changed in addition to the soft tissue debridement. This may explain the better results.

Several factors may have an influence on the difference between THA and hemiarthroplasty PJIs. The patients with hemiarthroplasty are older, often frail, and have more comorbidities. The hemiarthroplasty is performed acutely with no room for selection of patients or for optimizing underlying diseases. Frailty is a known risk factor for surgical complications, and reduces the capacity to handle the trauma that a fracture, an operation, or an infection represents (Saxton and Velanovich 2011, Partridge et al. 2012). Lastly, the microbiology in hemiarthroplasty PJIs appears to be different, with a higher rate of microbes associated with treatment failure.

While the literature describes an association between short duration of symptoms and success of treatment (Triantafyllopoulos et al. 2015), we found no such association.

Resection arthroplasty was performed in one-third of our patients. There is very little literature on resection arthroplasty in hemiarthroplasty PJI, but Blomfeldt et al. (2015) have reported 11 resection arthroplasties out of 22 PJIs in primary hemiarthroplasty following hip fracture. Resection arthroplasty has been associated with good infection control, yet in our material we found that only 5 of 12 became free of infection. This could be explained by the fact that 6 patients died during the treatment period, and therefore had an uncertain infection status. Furthermore, the characteristics of patients in our material—with elderly patients with several comorbidities—differ from those of patients who are electively operated for a degenerative hip disorder. But, even if a resection arthroplasty leads to successful infection control, it is a poor solution with pain, limited mobility, hip instability, and limb shortening.

Mortality

The overall 1-year mortality rate in patients treated with hemiarthroplasty after femoral neck fracture in the 5 original studies was 19–26%. The mortality rate in the current study was almost double that. A higher mortality rate in these patients is not unexpected, and the literature describes 1-year mortality rates of 50% in patients with PJI following hemiarthroplasty (Edwards et al. 2008). Possible explanations could be the frailty of the patients, systemic spread of infection, chronic low-grade infection, and longer in-hospital time with increased risk of nosocomial infections and complications due to immobility.

Microbiology

We found a higher rate of polymicrobial infections than has been reported in other studies (4–37%) (Marculescu and Cantey 2008). However, Wimmer et al. (2015) reported findings similar to ours in patients with PJI after THA. They also proposed that polymicrobial infections are under-reported in the literature, a suggestion that is supported by our results.

Polymicrobial infections are associated with varying treatment success. Wimmer et al. (2015) found an association between polymicrobial infections and treatment failure. Marculescu and Cantey (2008) found a lower, albeit not statistically significant, success rate in polymicrobial infections. This corresponds well with our findings. Furthermore, a high number of the polymicrobial infections were positive for Enterococcus spp. Enterococcal PJIs are associated with poorer treatment results (Rasouli et al. 2012).

Gram-negative bacteria are rarely reported to cause PJI in THA (Zimmerli et al. 2004). In Zimmerli’s material, Gram-negative strains were isolated in 5 of 37 infections. We did not find any cultures positive for MRSA, a finding that corresponds well with the low prevalence of MRSA in Norway (Elstrom et al. 2012).

Gentamicin resistance was found in a large proportion of the infections, especially among the MRSE strains. Lutro et al. (2014) reported 70% methicillin resistance among coagulase negative staphylococci, increasing with time in PJIs reported to the Norwegian Arthroplasty Registry between 1993 and 2007. This has also been reported in several previous studies on PJI (Moran et al. 2007, Sharma et al. 2008, Stéfansdóttir et al. 2009b, Malhas et al. 2014). Adding gentamicin to the bone cement has been shown to reduce the risk of revision of THA due to infection (Engesaeter et al. 2003), but this may also have contributed to selection of resistant bacteria. No strains of Staphylococcus aureus were gentamicin-resistant, which correlates with very low reported gentamicin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus strains from wound lesions and bacteremia reported to the Norwegian Surveillance System for Antimicrobial Drug Resistance (NORM, Annual report 2015). We did not find that this resistance pattern affected the treatment results, though.

Cephalotin is a commonly used prophylactic antibiotic in prosthetic surgery, and it is the recommended prophylaxis in Norway (Engesaeter et al. 2003). The high number of PJIs caused by MRSE, Gram-negatives, and Enterococus spp. in this 14-year cohort is worrisome, as they are not covered by the current prophylaxis. Different antibiotic regimens have been studied to prevent surgical site infections, especially in regions with a high prevalence of MRSA. Both dual prophylaxis containing cefuroxime and teicoplanin, and vancomycin-based regimens have been studied (Soriano et al. 2006, Meehan et al. 2009, Capdevila et al. 2016). There is still no consensus, though.

Strengths and weaknesses

First, this was a single-center study, which leads to the possibility of uncontrolled selection bias. The fact that all patients were included in earlier studies gives both strengths and limitations. The patients were followed closely over a longer period of time, and it is therefore likely that most complications were discovered. Most of the data were registered prospectively during the study period, but the additional data specific for PJI were collected retrospectively from the patient charts, possibly leading to uncertainty in the data. The material had a size that would limit statistical strength. Nevertheless, our study had a rather large patient material compared to other reports on hemiarthroplasty PJI.

In conclusion, PJI in elderly patients operated with hemiarthroplasty for a femoral neck fracture is a serious complication with a devastating outcome. The etiology and prognosis appear to be different from PJI after primary THA. Our findings suggest that different prophylaxis and treatment algorithms may be needed for patients who are to be treated with hemiarthroplasty for hip arthroplasty.

MW initiated the study. EG collected the data, performed the data analysis, and wrote the manuscript. All the authors critically reviewed it and contributed to the final version.

References

- Barberan J, Aguilar L, Carroquino G, Gimenez MJ, Sanchez B, Martinez D, Prieto J.. Conservative treatment of staphylococcal prosthetic joint infections in elderly patients. Am J Med 2006; 119(11): 993.e7–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari M, Devereaux PJ, Tornetta P 3rd, Swiontkowski MF, Berry DJ, Haidukewych G, et al. Operative management of displaced femoral neck fractures in elderly patients: an international survey. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2005; 87(9): 2122–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomfeldt R, Kasina P, Ottosson C, Enocson A, Lapidus LJ.. Prosthetic joint infection following hip fracture and degenerative hip disorder: a cohort study of three thousand, eight hundred and seven consecutive hip arthroplasties with a minimum follow-up of five years. Int Orthop 2015; 39(11): 2091–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchheit J, Uhring J, Sergent P, Puyraveau M, Leroy J, Garbuio P.. Can preoperative CRP levels predict infections of bipolar hemiarthroplasty performed for femoral neck fracture? A retrospective, multicenter study. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2015; 25(1): 117–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capdevila A, Navarro M, Bori G, Tornero E, Camacho P, Bosch J, Garcia S, Mensa J, Soriano A.. Incidence and risk factors for infection when Teicoplanin is included for prophylaxis in patients with hip fracture. Surg Infect 2016; 17(4): 381–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cumming D, Parker M J.. Urinary catheterisation and deep wound infection after hip fracture surgery. Int Orthop 2007; 31(4): 483–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Toro MD, Nieto I, Guerrero F, Corzo J, del Arco A, Palomino J, et al. Are hip hemiarthroplasty and total hip arthroplasty infections different entities? The importance of hip fractures. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2014; 33(8): 1439–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards C, Counsell A, Boulton C, Moran CG.. Early infection after hip fracture surgery: risk factors, costs and outcome. Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2008; 90(6): 770–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elstrom P, Kacelnik O, Bruun T, Iversen B, Hauge SH, Aavitsland P.. Meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Norway, a low-incidence country, 2006-2010. J Hosp Infect 2012; 80(1): 36–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engesaeter L B, Lie S A, Espehaug B, Furnes O, Vollset S E, Havellin L I.. Antibiotic prophylaxis in total hip arthroplasty: effects of antibiotic prophylaxis systemically and in bone cement on the revision rate of 22,170 primary hip replacements followed 0-14 years in the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop Scand 2003; 74(6): 644–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figved W, Opland V, Frihagen F, Jervidalo T, Madsen J E, Nordsletten L.. Cemented versus uncemented hemiarthroplasty for displaced femoral neck fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009; 467(9): 2426–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frihagen F, Madsen J E, Aksnes E, Bakken H N, Maehlum T, Walloe A, et al. Comparison of re-operation rates following primary and secondary hemiarthroplasty of the hip. Injury 2007a; 38(7): 815–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frihagen F, Nordsletten L, Madsen J E.. Hemiarthroplasty or internal fixation for intracapsular displaced femoral neck fractures: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2007b; 335(7632): 1251–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Alvarez F, Al-Ghanem R, Garcia-Alvarez I, Lopez-Baisson A, Benal M.. Risk factors for postoperative infections in patients with hip fracture treated by means of Thompson arthroplasty. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2010; 50(1): 51–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes A B, Weiser T G, Berry W R, Lipsitz S R, Breizat A H, Dellinger E P, et al. A surgical safety checklist to reduce morbidity and mortality in a global population. The N Eng J Med 2009; 360(5): 491–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz S M, Lau E, Schmier J, Ong KL, Zhao K, Parvizi J.. Infection burden for hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States. J Arthroplasty 2008; 23(7): 984–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lora-Tamayo J, Euba G, Ribera A, Murillo O, Pedrero S, Garcia-Somoza D, et al. Infected hip hemiarthroplasties and total hip arthroplasties: Differential findings and prognosis. J Infection 2013; 67(6): 536–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutro O, Langvatn H, Dale H, Schrama J C, Hallan G, Espehaug B, Sjursen H, Engesaeter L B.. Increasing resistance of Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci in total hip arthroplasty infections: 278 THA-revisions due to infection reported to the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register from 1993 to 2007. Adv Orthop 2014; 2014: 580359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhas A M, Lawton R, Reidy M, Nathwani D, Clift B A.. Causative organisms in revision total hip & knee arthroplasty for infection: increasing multi-antibiotic resistance in coagulase-negative Staphylococcus and the implications for antibiotic prophylaxis. Surgeon 2015; 13(5): 250–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangram A J, Horan T C, Pearson M L, Silver L C, Jarvis W R.. Guideline for prevention of surgical site infection, 1999. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Am J Infect Control 1999; 27(2): 97–132; quiz 3-4; discussion 96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marculescu C E, Cantey J R.. Polymicrobial prosthetic joint infections: risk factors and outcome. Clin Orthop Rel Res 2008; 466(6): 1397–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meehan J, Jamali A A, Nguyen H.. Prophylactic antibiotics in hip and knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2009; 91: 2480–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrer J, Girou E, Lortat-Jacob A, Montravers P, Lucet J C.. Surgical site infection after surgery to repair femoral neck fracture: a French multicenter retrospective study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2007; 28(10): 1169–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran E, Masters S, Berendt A R, McLardy-Smith P, Byren I, Atkins B L.. Guiding empirical antibiotic therapy in orthopaedics: The microbiology of prosthetic joint infection managed by debridement, irrigation and prosthesis retention. J Infection 2007; 55(1): 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partridge J S, Harari D, Dhesi J K.. Frailty in the older surgical patient: a review. Age and ageing 2012; 41(2): 142–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips J E, Crane T P, Noy M, Elliott T S, Grimer R J.. The incidence of deep prosthetic infections in a specialist orthopaedic hospital: a 15-year prospective survey. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2006; 88(7): 943–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasouli M R, Tripathi M S, Kenyon R, Wetters N, Della Valle C J, Parvizi J.. Low rate of infection control in enterococcal periprosthetic joint infections. Clin Orthop Rel Res 2012; 470(10): 2708–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridgeway S, Wilson J, Charlet A, Kafatos G, Pearson A, Coello R.. Infection of the surgical site after arthroplasty of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2005; 87(6): 844–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxton A, Velanovich V.. Preoperative frailty and quality of life as predictors of postoperative complications. Ann Surg 2011; 253(6): 1223–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma D, Douglas J, Coulter C, Weinrauch P, Crawford R.. Microbiology of infected arthroplasty: implications for empiric peri-operative antibiotics. J Orthop Surg 2008; 16(3): 339–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano A, Popescu D, Garcia S, Bori G, Martinez J A, Balasso V, Marco F, Almela M, Mensa J.. Usefulness of teicoplanin for preventing methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in orthopedic surgery. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2006; 25(1): 35–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stéfansdóttir A, Robertsson O, A WD, Kiernan S, Gustafson P, Lidgren L.. Inadequate timing of prophylactic antibiotics in orthopedic surgery. We can do better. Acta Orthop 2009a; 80(6): 633–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stéfansdóttir A, Johansson D, Knutson K, Lidgren L, Robertsson R.. Microbiology of the infected knee arthroplasty: report from the Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register on 426 surgically revised cases. Scan J Inf Dis 2009b; 41(11–12): 831–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swierstra B A, Vervest A M, Walenkamp G H, Schreurs B W, Spierings P T, Heyligers I C, et al. Dutch guideline on total hip prosthesis. Acta Orthop 2011; 82(5): 567–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Norwegian Surveillance System for Antimicrobial Drug Resistance (NORM) Annual Report 2015. www.antibiotikaresistens.no. [Google Scholar]

- Triantafyllopoulos G K, Poultsides L A, Sakellariou V I, Zhang W, Sculco P K, Ma Y, et al. Irrigation and debridement for periprosthetic infections of the hip and factors determining outcome. Int Orthop 2015; 39(6): 1203–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukayama D T, Estrada R, Gustilo R B.. Infection after total hip arthroplasty. A study of the treatment of one hundred and six infections. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1996; 78(4): 512–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watne L O, Torbergsen A C, Conroy S, Engedal K, Frihagen F, Hjorthaug G A, et al. The effect of a pre- and postoperative orthogeriatric service on cognitive function in patients with hip fracture: randomized controlled trial (Oslo Orthogeriatric Trial). BMC medicine 2014; 12: 63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westberg M, Grogaard B, Snorrason F.. Early prosthetic joint infections treated with debridement and implant retention: 38 primary hip arthroplasties prospectively recorded and followed for median 4 years. Acta Orthop 2012; 83(3):2 27–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westberg M, Snorrason F, Frihagen F.. Preoperative waiting time increased the risk of periprosthetic infection in patients with femoral neck fracture. Acta Orthop 2013; 84(2): 124–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimmer M D, Friedrich M J, Randau T M, Ploeger M M, Schmolders J, Strauss A A, Hischebeth G T, Pennekamp P H, Vavken P, Gravius S.. Polymicrobial infections reduce the cure rate in prosthetic joint infections: outcome analysis with two-stage exchange and follow-up ≥ two years. Int Orthop 2016; 40(7): 1367–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerli W, Trampuz A, Ochsner P E.. Prosthetic-joint infections. N Eng J Med 2004; 351(16): 1645–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]