Abstract

Background and purpose

The accuracy of using clinical measurement from the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) to the center of the knee to determine an anatomic axis of the femur has rarely been studied. A radiographic technique with a full-length standing scanogram (FLSS) was used to assess the adequacy of the clinical measurement.

Patients and methods

100 consecutive young adult patients (mean age 34 (20–40) years) with chronic unilateral lower extremity injuries were studied. The pelvis and intact contralateral lower extremity images in the FLSS were selected for study. The angles between the tibial axis and the femoral shaft anatomic axis (S-AA), the piriformis anatomic axis (P-AA), the clinical anatomic axis (C-AA), and the mechanical axis (MA) were compared between sexes.

Results

Only the S-AA and C-AA angles were statistically significantly different in the 100 patients (3.6° vs. 2.8°; p = 0.03). There was a strong correlation between S-AA, P-AA, and C-AA angles (r > 0.9). The average intersecting angle between MA and S-AA in the femur in the 100 patients was 5.5°, and it was 4.8° between MA and C-AA.

Interpretation

Clinical measurement of an anatomic axis from the ASIS to the center of the knee may be an adequate and acceptable method to determine lower extremity alignment. The optimal inlet for antegrade femoral intramedullary nailing may be the lateral edge of the piriformis fossa.

The anatomic axis of the femur can be clinically defined from the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) to the center of the knee (Sharma et al. 2001, Waller et al. 2011). However, the adequacy of this clinical measurement has seldom been studied. If it is acceptable, the clinical follow-up of patients will be simple and the cost-effectiveness is maximized. With a full-length standing scanogram (FLSS), the ASIS, femur, knee, tibia, and ankle can be clearly defined. The purpose of this retrospective study was to use FLSS to verify the adequacy of clinical measurement of an anatomic axis.

Patients and methods

FLSSs from 100 consecutive adult patients from May 2008 through July 2013, obtained for treatment of unilateral femoral or tibial nonunions or malunions, were used for this study. Rotation of the lower extremity was not checked by fluoroscopy during taking of the FLSS. The mean age of the 100 patients was 34 (20–40) years and there were 50 women. The mean length of time from the injury to taking of a FLSS was 1.3 (0.6–2.2) years.

The inclusion criteria were young adult patients (20–40 years old), healthy before injury, unilateral lower extremity injury, and an intact pelvis. Exclusion criteria were pelvic or bilateral lower extremity injuries, or having associated congenital or developmental anomalies. There were no severe angular malunions in the femur.

FLSS images from all 100 patients were stored in picture achieving and communication systems (PACS) software (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) at the author’s institution (Johnson et al. 2008). Data from the pelvis and intact contralateral lower extremities were selected for analysis.

Data analysis

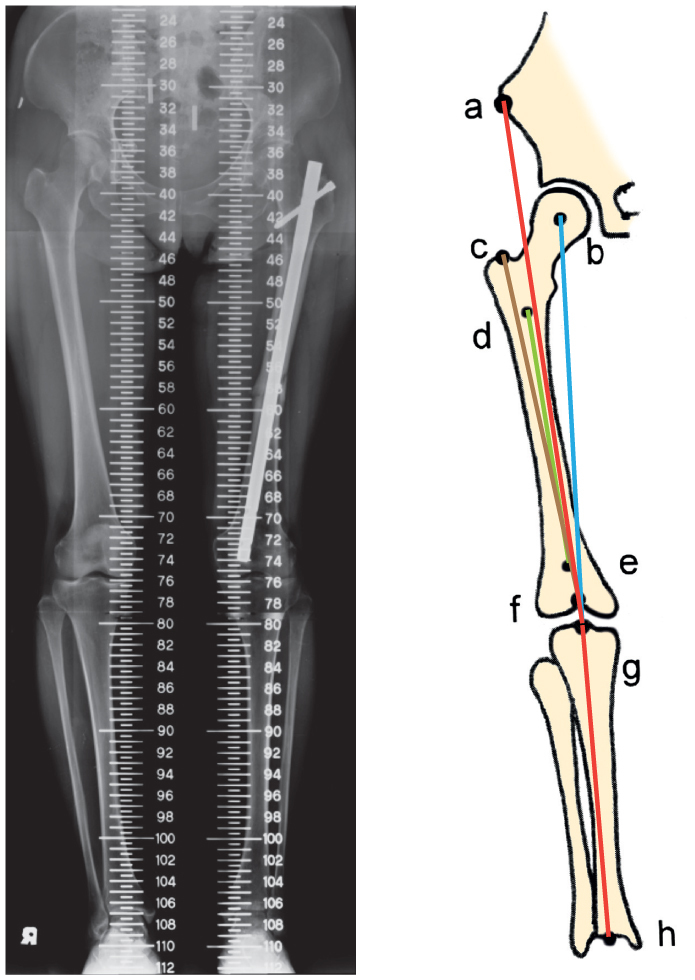

Various parameters were defined as follows (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Depiction of various anatomic points: (a) anterior superior iliac spine, (b) center of the femoral head, (c) lateral edge of the piriformis fossa, (d) center of marrow cavity at the lower level of the lesser trochanter, (e) center of marrow cavity at the upper level of the femoral condyle, (f) intercondylar notch, (g) center of knee articular surface, and (h) center of the talus.

In the femur, (1) S-AA (shaft anatomic axis) was a line connecting centers of the marrow cavity at the lower level of the lesser trochanter and the upper level of the femoral condyle; (2) P-AA (piriformis anatomic axis) was a line connecting the lateral edge of the piriformis fossa and the intercondylar notch; (3) C-AA (clinical anatomic axis) was a line connecting the ASIS and the center of the tibial articular surface. It is the most commonly used technique clinically in determining a femoral anatomic axis. Clinically, it is performed with a ruler connecting the ASIS and the center of the knee joint; (4) MA (mechanical axis) was a line connecting the centers of the femoral head [author: unclear] and the tibial articular surface.

In the tibia, a line connecting the center of the tibial articular surface in the knee and the center of the talus was used to indicate both the tibial mechanical and anatomic axes (the tibial axis). (1) S-AA angle was the angle formed by the S-AA and the tibial axis; (2) P-AA angle was the angle formed by the P-AA and the tibial axis; (3) C-AA angle was the angle formed by the C-AA and the tibial axis; (4) MA angle was the angle formed by the femoral mechanical axis and tibial axis. The value was positive for valgus alignment and negative for varus alignment.

Statistics

Data were analyzed using Microsoft Office Excel 2010 software. For statistical comparisons, an unpaired Student t-test was used and p-values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. Data are presented as mean with 95% confidence interval (CI). Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient was used to evaluate the degree of relationship between two parameters.

Ethics

This study was approved by the institutional review board of the author’s institution (IRB no. 201600956B0).

Results

The average S-AA angle was 3.6° (3.1–4.1). For men it was 3.3° (2.6–4.0) and for women it was 3.9° (3.1–4.7) (p = 0.2) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Radiographic measurement of the anatomic axis of the femur. Values are mean and (95% confidence interval)

| Parameters | Total (n = 100) | Men (n = 50) | Women (n = 50) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-AA angle (°) | 3.6 (3.1–4.1) | 3.3 (2.6–4.0) | 3.9 (3.1–4.7) | 0.2 |

| P-AA angle (°) | 3.4 (2.9–3.9) | 3.1 (2.3–3.9) | 3.6 (2.9–4.3) | 0.4 |

| C-AA angle (°) | 2.8 (2.3–3.3) | 2.5 (1.9–3.1) | 3.1 (2.3–3.9) | 0.2 |

| MA angle (°) | −2.1 (−2.6 to −1.6) | −2.6 (−3.4 to −1.8) | −1.7 (−1.0 to −2.4) | 0.08 |

| MA vs. S-AA (°) | 5.5 (5.2–5.8) | 5.5 (4.9–6.1) | 5.6 (5.3–5.9) | 0.7 |

| MA vs. C-AA (°) | 4.8 (4.6–5.0) | 5.0 (4.6–5.4) | 4.7 (4.4–5.0) | 0.4 |

C-AA: clinical anatomic axis; MA: mechanical axis; P-AA: piriformis anatomic axis;

S-AA: shaft anatomic axis.

The average P-AA angle was 3.4° (2.9–3.9). For men it was 3.1° (2.3–3.9) and for women it was 3.6° (2.9–4.3) (p = 0.4).

The average C-AA angle was 2.8° (2.3–3.3). For men it was 2.5° (1.9–3.1) and for women it was 3.1° (2.3–3.9) (p = 0.2).

The average MA angle was −2.1° (−2.6 to −1.6). For men it was −2.6° (−3.4 to −1.8) and for women it was −1.7° (−1.0 to −2.4) (p = 0.08).

The average intersecting angle between MA and S-AA in the femur was 5.5° (5.2–5.8). It was 5.5° (4.9–6.1) for men and 5.6° (5.3–5.9) for women (p = 0.7).

The average intersecting angle between MA and C-AA in the femur was 4.8° (4.6–5.0). It was 5.0° (4.6–5.4) for men and 4.7° (4.4–5.0) for women (p = 0.4) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Angles of the MA (mechanical axis) plotted against the C-AA (clinical anatomic axis). There was no significant difference between the sexes (p = 0.4).

MA anglewomen = (0.79 × C-AA angle) − 4.09;

MA anglemen = (1.05 × C-AA angle) − 5.18.

Average S-AA angle and average C-AA angle were statistically significantly different in all 100 patients (3.6° vs. 2.8°; p = 0.03). However, there was no statistically significant difference between men and women (p = 0.1).

The Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient for S-AA angle and P-AA angle was 0.97 in all 100 patients; 0.97 in men and 0.96 in women (Table 2).

Table 2.

Correlations between various radiographic measurements

| Parameters | Total (n = 100) | Men (n = 50) | Women (n = 50) |

|---|---|---|---|

| S-AA/P-AA angles | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.96 |

| S-AA/C-AA angles | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.92 |

| P-AA/C-AA angles | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.93 |

C-AA: clinical anatomic axis; P-AA: piriformis anatomic axis;

S-AA: shaft anatomic axis

The Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient for S-AA angle and C-AA angle was 0.90 in all 100 patients; 0.91 in men and 0.92 in women.

The Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient for P-AA angle and C-AA angle was 0.91 in all 100 patients; 0.91 in men and 0.93 in women.

Discussion

Clinical measurement of body alignment without using radiographs is a common and practical method. Measurement with an FLSS requires much more work and radiation exposure (Colebatch et al. 2009). If clinical measurement could reasonably replace radiographs, follow-up of patients would be more convenient. In the current study, measurement of the anatomic axis with the clinical technique was found to have an acceptable precision. Holme et al. (2015) compared computed tomography scanogram and FLSS for determining axial knee alignment, and found that the former was not superior. They strongly recommended FLSS.

Because of the large muscles in the thigh, the femoral shaft cannot normally be palpated. An anatomic axis cannot be directly measured and a classic clinical technique (from the ASIS to the center of the knee) is recommended. In the literature and in the present study, the femur from the lower level of the lesser trochanter to the upper level of the femoral condyle is defined as the femoral shaft (Wu and Shih 1991, Wu and Lee 2004). In the current study, clinical measurement of an anatomic axis (i.e. C-AA) was highly correlated with the S-AA (correlation coefficient ≥0.9). Thus, clinical measurement may be adequate. Although the comparison between S-AA and C-AA angles was statistically significant in 100 patients (p = 0.03), the difference was only 0.8° (3.6° vs. 2.8°). In other words, using clinical measurement for an anatomic axis is acceptable.

In the present study, S-AA and P-AA angles were similar (3.6° and 3.4°). If a femoral shaft fracture is treated with an antegrade intramedullary nail, the optimal nail inlet may be at the lateral edge of the piriformis fossa (Browner 1986, Gugenheim et al. 2004, Charopoulos and Giannoudis 2009) to obtain an anatomic alignment. Although using the inlet from the greater trochanter tip is technically easier for closed intramedullary nailing, it normally introduces a varus deformity of the femoral shaft (Gardener et al. 2008, Farhang et al. 2014).

In the literature, the angle formed by the S-AA and MA in the femur is 5–7° (Paley and Tetsworth 1992, Luo 2004, Collinge and Wiss 2015). Harvey et al. (2008) reported that the Chinese population had a more valgus alignment of the distal femur than the Caucasian population, which might explain a higher prevalence of lateral tibiofemoral osteoarthritis. However, the anatomic angle (AA) in both populations (4.3° and 2.6°) is still within the varus range (< 5–7°). Further studies may therefore be necessary to confirm this conclusion.

MA of the lower extremity (from the center of the femoral head to the center of the talus) normally passes through the medial knee compartment, a little bit from the knee center (Ogata et al. 1991, Kuroyanagi et al. 2012, Robinson and Vanrenterghem 2012). Thus, a varus angle forms between the femoral and tibial MA. In the present study, a mean varus angle of 2.1° was found in the 100 patients. That the MA of the lower extremity did not pass through the center of the knee may be due to fact that the 100 patients had mild varus knees at that time. Moreland et al. (1987) reported varus 1.1°–1.5° of the MA of the lower extremity in 25 male volunteers (average age 30 years) as measured by FLSS. The angle of 5.5° (4.9–6.1) formed by the S-AA and MA in the femur is generally unchanged; it does not involve the medial knee compartment.

The limitations of my study included the following. (1) The FLSS was taken from patients with unilateral lower extremity injuries, and not healthy individuals. However, the patients were young with small risk of degenerative disease of the hip, knee, and ankle joints. Consequently, measurement of lower extremity alignment may have been acceptable. (2) Some authors have doubted the accuracy of an FLSS (Ogata et al. 1991). However, FLSS has been widely used to determine the lower extremity alignment. It may be superior to any other tools available, to expose the entire lower extremity.

In conclusion, clinical measurement of an anatomic axis from the ASIS to the center of the knee may be an adequate and acceptable technique for determination of lower extremity alignment. Clinical measurement has very little error as compared to a radiographic study. The optimal inlet for antegrade femoral intramedullary nailing may be the lateral edge of the piriformis fossa.

There was no funding, and the author declares that there were no competing interests.

References

- Browner B D. Pitfalls, errors, and complications in the use of locking Kuntscher nails. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1986; (212): 192–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charopoulos I, Giannoudis P V.. Ideal entry point in antegrade femoral nailing: controversies and innovations. Injury 2009; 40(8): 791–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colebatch A N, Hart D J, Zhai G, Williams F M, Spector T D, Arden N K.. Effective measurement of knee alignment using AP knee radiographs. Knee 2009; 16(1): 42–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collinge C A, Wiss D A.. Distal femur fractures. In: Rockwood and Green’s fractures in adults (Eds. Court-Brown C M, Heckman J D, McQueen M M, Ricci W M, Tornetta P III). Wolters Klumer Co. Philadelphia 2015; 2: 2229–68. [Google Scholar]

- Farhang K, Desai R, Wilber J H, Cooperman D R, Liu R W.. An anatomical study of the entry point in the greater trochanter for intramedullary nailing. Bone Joint J 2014; 96-B(9): 1274–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardener M J, Robertson W J, Boraiah S, Barker J U, Lorich D G.. Anatomy of the greater trochanteric ‘bald spot’: a potential portal for abductor sparing femoral nailing? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2008; 466(9): 2196–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gugenheim J J, Probe R A, Brinker M R.. The effects of femoral shaft malrotation on lower extremity anatomy. J Orthop Trauma 2004; 18(10): 658–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey W F, Niu J, Zhang Y, McCree P I, Felson D T, Nevitt M, Xu L, Aliabadi P, Hunter D J.. Knee alignment differences between Chinese and Caucasian subjects without osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2008; 67(11): 1524–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holme T J, Henckel J, Hartshorn K, Cobb J P, Hart A J.. Computed tomography scanogram compared to long leg radiograph for determining axial knee alignment. Acta Orthop 2015; 86(4): 440–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson L J, Cope M R, Shahrokhi S, Tamblyn P.. Measuring tip-apex distance using a picture archiving and communicating system (PACS). Injury 2008; 39(7): 786–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroyanagi Y, Nagura T, Kiriyama Y, Matsumoto H, Otani T, Toyama Y, Suda Y.. A quantitative assessment of varus thrust in patients with medial knee osteoarthritis. Knee 2012; 19(2): 130–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo C F. Reference axis for reconstruction of the knee. Knee 2004; 11(4): 251–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreland J R, Bassett L W, Hanker G J.. Radiographic analysis of the axial alignment of the lower extremity. J Bone Joiunt Surg (Am) 1987; 69(5): 745–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogata K, Yoshii I, Kawamura H, Miura H, Arizono T, Sugioka Y.. Standing radiographs cannot determine the correction in high tibial osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1991; 73(6): 927–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paley D, Tetsworth K.. Mechanical axis deviation of the lower limbs: preoperative planning of uniapical angular deformities of the tibia or femur. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1992; (280): 48–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson M A, Vanrenterghem J.. An evaluation of anatomical and functional knee axis definition in the context of side-cutting. J Biomech 2012; 45(11): 1941–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma L, Song J, Felson DT, Cahue S, Shamiyeh E, Dunlop D D.. The role of knee alignment in disease progression and functional decline in knee osteoarthritis. J Am Med Assoc 2001; 286(2): 188–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller C, Hayes D, Block J E, London N J.. Unload it: the key to the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2011; 19(11): 1823–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C C, Lee Z L.. One-stage lengthening using a locked nailing technique for distal femoral shaft nonunions associated with shortening. J Orthop Trauma 2004; 18(2): 75–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C C, Shih C H.. Distal femoral nonunion treated with interlocking nailing. J Trauma 1991; 31(12): 1659–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]