Abstract

Background and purpose

In 3 papers in Acta Orthopaedica 10 years ago, we described that platelet-rich plasma (PRP) improves tendon healing in a rat Achilles transection model. Later, we found that microtrauma has similar effects, probably acting via inflammation. This raised the suspicion that the effect ascribed to growth factors within PRP could instead be due to unspecific influences on inflammation. While testing this hypothesis, we noted that the effect seemed to be related to the microbiota.

Material and methods

We tried to reproduce our old findings with local injection of PRP 6 h after tendon transection, followed by mechanical testing after 11 days. This failed. After fruitless variations in PRP production protocols, leukocyte concentration, and physical activity, we finally tried rats carrying potentially pathogenic bacteria. In all, 242 rats were used.

Results

In 4 consecutive experiments on pathogen-free rats, no effect of PRP on healing was found. In contrast, apparently healthy rats carrying Staphylococcus aureus showed increased strength of the healing tendon after PRP treatment. These rats had higher levels of cytotoxic T-cells in their spleens.

Interpretation

The failure to reproduce older experiments in clean rats was striking, and the difference in response between these and Staphylococcus-carrying rats suggests that the PRP effect is dependent on the immune status. PRP functions may be more complex than just the release of growth factors. Extrapolation from our previous findings with PRP to the situation in humans therefore becomes even more uncertain.

We have previously shown that platelet concentrates (platelet-rich plasma (PRP)) can improve tendon healing in a rat Achilles tendon model. This effect was seen after local injection 6 h after tendon transection and also after implantation of a PRP coagulum during surgery (Aspenberg and Virchenko 2004, Virchenko and Aspenberg 2006, Virchenko et al. 2006). The stimulatory effect disappeared if the limb was mechanically unloaded and increased if the rats were stimulated to increase their physical activity (Virchenko and Aspenberg 2006). These studies were the first to show effects of platelets in tendon healing, and might in part be responsible for the unfortunate surge in clinical use of PRP, especially in sports medicine.

After these studies, we left the PRP field and focused on the role of mechanical stimulation of tendon healing, using the same rat model. A series of experiments showed that mechanical loading strongly increased tendon strength (Eliasson et al. 2012a, Eliasson et al. 2013, Hammerman et al. 2014). A single episode of mechanical loading, sufficient to improve mechanical strength, also activated genes primarily related to inflammation (Eliasson et al. 2012b). The stimulatory effect of loading was evident at an early time point, when the tendon callus largely consists of leukocytes (Blomgran et al. 2016). This suggested that the mechanical improvement after loading was mediated via these leukocytes, i.e. through inflammation. A further indication that inflammation plays a crucial role was the finding that micro-damage caused by needling could substitute for mechanical loading, leading to a similar increase in mechanical strength (Hammerman et al. 2014).

In an attempt to find a “unifying theory” for this model, we speculated that all positive effects on healing are due to inflammation, including the previous positive effects with PRP. In order to show this, we needed to repeat the old PRP experiments. However, it turned out that we were unable to reproduce our previous results. While desperately trying to find what was different between the old successful experiments and the new failing ones, we finally considered the observation that fracture healing in mice is dependent on the bacteriological environment of the breeding facilities (Reinke at al. 2013). Fracture healing is impaired if the immune system has matured as a consequence of bacterial challenges, raising the levels of CD8+ T-cells especially. By coincidence, routine screening of a batch of rats delivered to us showed growth of Staphylococcus aureus. These animals were denied access to the animal facility. This gave an unexpected opportunity to test the role of the bacteriological status. The rats were transferred to another facility, and then, for the first time, the old effects of PRP appeared again.

Methods

overview

242 rats were used in 6 experiments.In all experiments, PRP in some form (always 50 μL) was compared with saline (Table 1). All experiments were evaluated mechanically, using peak force as the primary effect variable. Flow cytometry and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) tests were performed in complementary experiments. All the surgery, PRP preparation, and injection was performed by FD.

Table 1.

Overview of the experimental groups

| Tendon | Pooled | Irradi- | Contami- | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exp. | Rats (SD or W) | Groups | n | resection | blood | ation | nated |

| 1 | 27 SD +6 W | 1. Saline | 14 | No | – | – | No |

| male donors | 2. PRP + thrombin | 13 | Yes | Yes | |||

| 2 | 24 SD +5 SD | 1. Saline | 12 | No | – | – | No |

| 2. PRP + CaCl2 | 12 | No | Yes | ||||

| 3 | 20 SD +5 SD | 1. Saline | 10 | No | No | ||

| 2. PRP | 10 | Yes | No | ||||

| 4 | 30 SD +10 SD | 1. Saline | 10 | 3 mm | – | – | No |

| 2. L-PRP | 10 | Yes | No | ||||

| 3. PRP low | 10 | Yes | Yes | ||||

| 5 | 30 SD +10 SD | 1. Saline | 10 | 2 mm | – | – | Yes |

| 2. L-PRP | 10 | Yes | No | ||||

| 3. PRP low | 10 | Yes | Yes | ||||

| 6 | 50 SD +13 SD | 1. Saline | 25 | No | – | – | Yes |

| 2. PRP | 25 | Yes | No |

Exp: experiment; SD: Sprague-Dawley; W: Wistar;

L-PRP: high-leukocyte PRP; PRP low: low leukocyte concentration.

Animals and housing

We used outbred female Sprague-Dawley rats (Janvier, Le Genest-Saint-Isle, France). They were derived from different breeding facilities, one of which had been contaminated with Staphylococcus aureus.

The animals were kept in acrylic cages (900 cm2) with not more than 3 animals in each cage, and placed on ventilated racks under controlled humidity (55%) and temperature (22 °C) with a 12-hour light-dark cycle. Water and pellets were provided ad libitum. All cages were provided with shredded paper, wooden pegs, and hiding places.

Standard treatment

The Achilles tendon was transected in 181 rats weighing on average 245 g (SD 25). The rats were anesthetized with isoflurane gas. Antibiotic was given preoperatively (25 mg/kg oxytetracycline). Analgesics were given subcutaneously pre- and postoperatively (0.045 mg/kg buprenorphine). Surgery was performed under aseptic conditions. The skin on the right lower leg was shaved and cleaned with chlorhexidine ethanol. The tendon complex was exposed through a transverse skin incision lateral to the Achilles tendon. The plantaris tendon was removed and the Achilles tendon was cut transversely in the middle part. The skin was closed with 2 stitches.

PRP (50 μL) or saline (50 μL) was injected percutaneously into the tendon defect using a 0.25-mm needle, 6 h after surgery.

Standard preparation of PRP

We used 49 donors. Whole blood was collected from anesthetized rats by cardiac puncture using a 10-mL syringe containing 1.1 mL of sodium citrate (0.13 mol/L) with a 1.2-mm needle. The rats were killed by exsanguination. The blood samples for each experiment were pooled and then centrifuged at 220× g for 20 min and then the supernatant at 480× g for 20 min. Platelets were counted using a clinical, automatic blood cell counter, and the concentration was adjusted for each experiment. Similarly to the old original experiments, the platelet concentrate was irradiated at 25 Gy to inactivate remaining white blood cells. The volume of PRP injected was always 50 μL. The PRP was used in less than 6 h and was not activated by added factors.

PRP with high leukocyte content (L-PRP) and standard PRP were prepared. To produce L-PRP, we took all the plasma and the buffy coat, including a small part of the erythrocyte layer for the second centrigugation. To produce standard PRP, we took the plasma and buffy coat, avoiding any part of the erythrocyte layer. After the second centrifugation, only the deepest tenth of the total volume was collected (200–300 μL). We used plasma to adjust the platelet concentration as necessary.

Variations in the standard procedure

Experiment 1 – All rats were delivered from Taconic (Denmark). Mechanical analysis was performed on day 14 instead of day 11. Blood was collected using citrate phosphonate dextrose anticoagulant (CPD) and the first centrifugation was performed for 40 min. Male Wistar rats were used as blood donors in order to provoke inflammation, by blood incompatibilities. PRP was stored for 24 h at 4 °C before use and thrombin (0.20 U; 1 μL) was used as activator.

Experiment 2 – Donor blood was not pooled, and thus different recipients had different donors. Calcium chloride (0.018 mol/L) was used as activator.

Experiment 3 – PRP was not irradiated, and the concentration of leukocytes was high (L-PRP).

Experiment 4 – We use cages designed for increased physical activity. These cages were larger (1,900 cm2) and were equipped with a second floor. 3 mm of the Achilles tendon was removed. We made 2 PRP groups: L-PRP without irradiation and standard PRP. These rats were checked for pathogen contamination, with negative findings.

Experiment 5 – On arrival, a routine check showed that both treated and donor animals carried Staphylococcus aureus. These animals turned out to have come from the same breeder, but from a different breeding house. Due to the positive cultures, the animals were transferred to a less clean animal facility and the cages were not cleaned from the day after surgery. A 2-mm tendon segment was removed. There were 2 PRP groups: L-PRP without irradiation and standard.

Experiment 6 – All rats (donors and treated) came from the breeding house where the animals carried Staphylococcus aureus (as confirmed by the breeder) and were taken directly to the less clean facility. The cages were not cleaned from the day after surgery. The PRP was not irradiated.

Evaluation—mechanical testing

11 days after surgery, the rats were anesthetized with isoflurane gas and killed with CO2. The right Achilles tendon with the calcaneal bone and muscles was harvested. The sagittal and transverse diameter of the midpart of the callus tissue was measured with a slide calliper, and the cross-sectional area was calculated by assuming an elliptical geometry. The distance between the old tendon stumps was measured, as seen through the partly transparent callus tissue. The muscles were scraped off from the tendon, and it was fixed in a metal clamp with sandpaper. The bone was fixed in a custom-made clamp at 30° dorsiflexion relative to the direction of traction in the materials-testing machine (100R; DDL, Eden Prairie, MN). The machine pulled at 0.1 mm/s until failure. Peak force at failure (N), stiffness (N/mm), and energy uptake (Nmm) were calculated by the software of the machine. The investigator marked a linear portion of the elastic phase of the curve for modulus calculation. Peak stress (MPa) and an estimate of Young’s modulus (MPa) were calculated assuming an elliptical cylindrical shape and homogenous mechanical properties. All measurements and calculations were carried out by investigators who were blinded (FD, MH, PB).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

In order to confirm that our platelets were not activated before use, we quantified the platelet derivate growth factor (PDGF-AB) in the platelet-poor supernatant after the second centrifugation. We similarly analyzed peripheral blood and different preparations of PRP.

We used a rat PDGF-AB ELISA kit (KBB-177; Nordic BioSite AB, Täby, Sweden). 100 μL from the test samples and 100 μL of assay diluent were placed in the wells in duplicate and incubated at 37 °C for 90 min. This solution was replaced with 100 μL of biotinylated anti-rat PDGF antibody working solution and incubated again at 37oC for 60 min. The wells were washed 3 times with 0.01 M Tris-buffered saline, incubated at 37 °C for 30 min with avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (ABC) and washed again 5 times with the diluents. Tetramethylbenzidine color-developing agent was added, with incubation at 37 °C in the dark for 25 min followed by addition of TMB stop solution. The absorbance at 450 nm was measured with a microplate reader.

Flow cytometry

The spleen from 12 female Janvier Sprague-Dawleys rats was removed under anesthesia as above. 6 rats were derived from the breeding facility that was contaminated with Staphylococcus aureus. The other 6 rats were specific opportunistic pathogen-free (SOPF), from the uncontaminated breeding house. The operator (FD) was blinded regarding sample identity during collection of the data and analysis.

Spleens were placed in support buffer (RPMI 1641, 4% fetal bovine serum, 5 mM EDTA, and 25 mM HEPES).

Flow cytometry was performed on a FACS Aria III (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) equipped with a 405-nm, 561-nm, and 633-nm laser. A nozzle of 100 μm was used. Cytometer Setup&Tracking Beads (BD Biosciences) were used to ensure stability of the cytometer. Compensation was performed with cellular controls from rat spleens with the same antibodies as in the experiment.

The spleens were digested with collagenase IV (300 U/mL) and DNAse I (300 U/mL) in support buffer containing 20 mM magnesium, for 20 min at 37 °C, and then washed (600× g for 6 min at 4 °C for all centrifuge steps) and filtered through a 30-μm nylon strainer. The suspension was then washed with staining buffer (Biolegend, San Diego, CA). Zombie Violet and anti-CD6/32 (Biolegend) were added for live/dead discrimination and Fc-blocking. The suspension was incubated in the dark on ice for 20 min. An aliquot of 1/10 (vol/vol) was taken from each suspension of the Staphylococcus-carrying rats’ spleens to form a pooled sample for “fluorescence minus one” (FMO) gating. This sample was used as FMO for both groups, but the operator did not know the group identity. The remaining 9/10 (vol/vol) of cells from each tissue suspension was divided equally to staining tubes for immunophenotyping.

The antibodies are listed in Table 2 (see Supplementary data). Primary staining was performed in the dark on ice for 30 min. The cells were then washed twice and secondary staining was performed under equivalent conditions. They were then fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature, followed by washing twice with staining buffer. Cells were stored at 8 °C for 1 day before flow cytometry.

Gating was set by FMO for CD25, as it was continuously expressed. Gatings of discrete antigens were set on population morphology. In all samples, initial gating was done on singlet cells, scatter parameters, live cells, and CD45+ cells to define single living leukocytes. Gating was performed in FlowJo vX.0.7 (Treestar, Ashland, OR).

Statistics

The peak force was the primary dependent variable. Each experiment was first regarded separately, and tested with 1-way ANOVA or Welch’s t-test using SPSS version 21. In the first experiments, the null hypotheses could not be refuted. We then tried to improve the experiments to mimic the old original experiments as much as possible, until we arrived at a final version (experiment 4) that we regarded as definite. Although the different experiments all had their own hypothesis, in retrospect we have regarded experiments 1–3 as being explorative and experiment 4 as being the definitive test for the effect on PRP in clean animals. This experiment was then repeated using Staphylococcus-carrying rats (experiment 5), and experiments 4 and 5 were compared using 2-way ANOVA with bacterial status and PRP treatment as fixed factors. We then had a new hypothesis, namely that bacterial status would influence the response to PRP (significant interaction). The PRP treatment comprised 2 subgroups, with high or low leukocyte content. As these subgroups did not show any statistically significant differences in any experiment, they were combined to one group in the final analysis.

Having seen a statistically significant interaction between bacterial status and response to PRP according to the pre-specified hypothesis, the study could be regarded as being complete. However, because we found the result to be so important, we repeated experiment 5, just to feel more confident. After this repeat (experiment 6), we entered all experiments (except experiment 1, which had a different healing time) into a 2-way ANOVA with presence of Staphylococcus and PRP treatment as fixed factors, specifically looking for an interaction between PRP and bacterial status. This analysis was regarded as the final hypothesis test.

Statistical analysis of flow cytometry was performed in the R programming environment. CD45+/CD3+/CD8a + in relation to CD45+ was chosen as the primary variable. Clean and Staphylococcus-carrying rats were compared using the Mann-Whitney U-test.

Ethics

All procedures were approved by the regional ethics committee (entry no. 15-15).

Results

16 rats were excluded due to technical problems at mechanical testing. 11 of these belonged to experiment 6 (5 PRP, 6 saline). Thus, 165 rats were tested successfully.

Platelet and leukocyte counts

The standard PRP had a platelet concentration at least 5 times higher than that of peripheral blood, and it was possible to have either a high or a low leukocyte count (Table 3, see Supplementary data).

PDGF-AB quantification

ELISA revealed PDGF-AB concentrations in the supernatant plasma samples (n = 4) below the level of detection (0.03 ng/mL). In inactivated PRP, the PDGF-AB concentration was 7.3 μg/mL (SD 6.0; n = 4). This confirms that the PRP production process did not cause activation and loss of growth factors into the supernatant.

Mechanical analysis

Experiments 1–4 failed to show any statistically significant effect of PRP on peak force. None of the experiments showed a significant difference between high and low leukocyte content of the PRP, and these groups were therefore combined to a single PRP group. A 2-way ANOVA of all experiments showed a significant variation in peak force between different experiments (p = 0.001), but there was no effect of PRP. The group mean difference between PRP and saline had a 95% confidence interval (CI) of −4.3 to 2.7 N, corresponding to −10% to 6% of control mean (p = 0.9), indicating that any meaningful effect could be excluded.

The first experiment on Staphylococcus-carrying rats showed increased peak force by 17% (p = 0.04), but also increased peak stress and energy uptake (Table 4).

Table 4.

Mechanical evaluation from experiment 5. Values are mean (SD)

| Difference, 95% CI expressed as % of saline |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saline | PRP | lower | mean | upper | |

| Peak force | 38 (5.8) | 44 (10) | 0.9 | 17 | 33 |

| Peak stress | 1.6 (0.4) | 2.1 (0.8) | 1.6 | 31 | 58 |

| Energy uptake | 87 (17) | 104 (23) | 2.3 | 20 | 38 |

| Stiffness | 5.5 (0.9) | 5.9 (1.4) | −7.1 | 7 | 24 |

| Cross-sectional area | 25 (5.9) | 23 (5.1) | −27 | −8 | 10 |

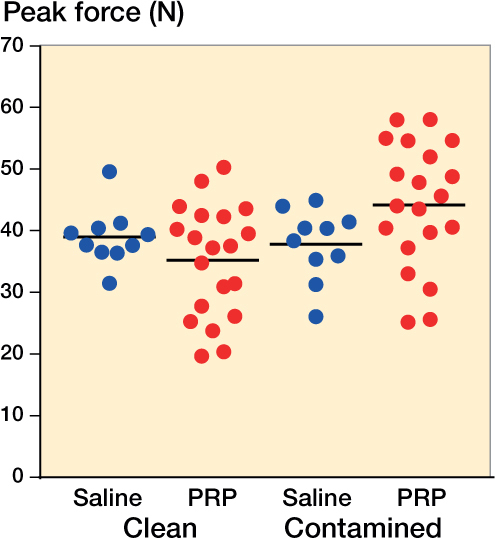

Comparing experiment 4 (the “final” clean experiment) and experiment 5 (Staphylococcus), there was an interaction between bacterial status and PRP treatment (p = 0.03) (Figure 1). There was also an interaction for peak stress (p = 0.003) and cross-sectional area (p = 0.03), but not for stiffness (p = 0.2).

Figure 1.

Peak force for contaminated and uncontaminated rats using PRP or saline as treatment (groups 4 and 5). Contaminated means carrying Staphylococcus aureus.

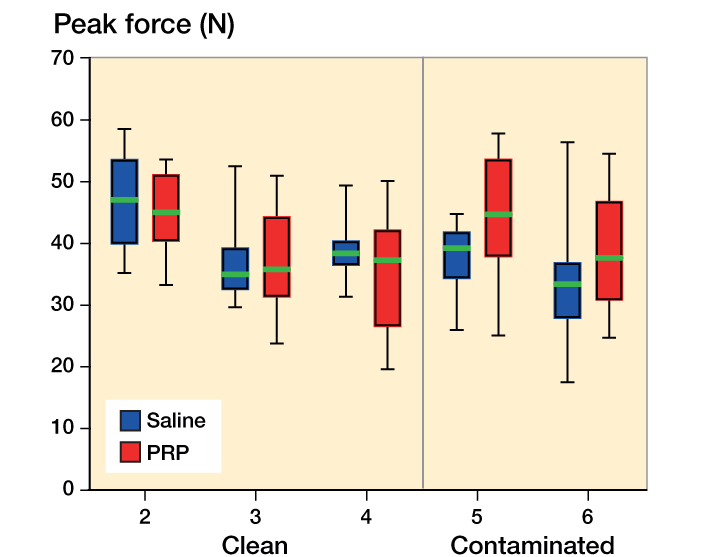

The sixth, confirmatory experiment on Staphylococcus carriers showed an increased peak force by 16%, but this time it was not statistically significant (p = 0.1).

The ANOVA on all experiments with an 11-day duration showed an interaction between the effects of bacterial status and PRP on peak force (p = 0.003). Post hoc, we also analyzed peak stress, stiffness, and cross-sectional area, which showed similar interactions (p < 0.001, p = 0.01, and p = 0.05) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Peak force for saline (blue) and PRP (red) groups in 11-day experiments. The graph shows median, interquartile range, and total range (whiskers). Contaminated means carrying Staphylococcus aureus.

Flow cytometry

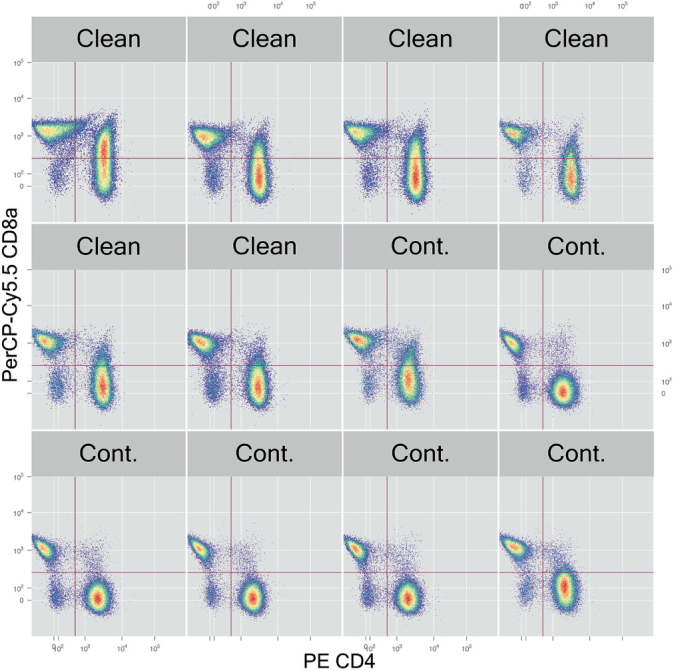

The CD45 labeling failed for unknown technical reasons, so we used live/CD3+/CD8a + in relation to live cells instead. The ratio of CD3+/CD8a + cells was higher in the pathogen-free rats (Mann-Whiney test, p = 0.03). The CD3+/CD4+/CD8a+ (double-positive T-cells) was severalfold higher in the pathogen-free rats (Mann-Whitney test, p = 0.009) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

T-cells in all samples. In some samples, the CD4+ cells can be seen to have a tail upwards, indicating double positivity for CD4 and CD8a. Cont. means carrying Staphylococcus aureus.

Discussion

The clinical experience with PRP is disappointing (Schepull et al. 2011, de Vos et al. 2014), and there is no convincing evidence for a positive effect on clinical tendon healing, tendinopathy, or enthesis problems—despite the fact that some papers have claimed so (Aspenberg and Ranstam 2014). We therefore set out to show that the stimulatory effects of PRP on tendon healing in our model were due to perturbation of the inflammatory reaction after trauma, making them less relevant to the human situation. Initially, we were unable to reproduce our old results. We prepared to report this failure, but then a new hypothesis emerged: we learned that bacteriological breeding conditions, reflected by presence of CD8 T-cells, had a strong influence on fracture healing in mice (Reinke et al. 2013). We could then show that the effect of PRP was indeed linked to inflammation: The effect was dependent on bacteriological breeding conditions, and appeared to be related to the prevalence of CD8a T-cells.

A recent overview has shown that microbiota or the combination of host and microbial genomes influences many organs in laboratory animals, and that this is dependent on factors such as bacterial environment, diet, temperature, and breeding conditions (Stappenbeck and Virgin 2016). Thus, it is not surprising that animal experiments with 10 years between them can yield different results.

Laboratory animals raised under pathogen-free conditions are thought to have an immune status that is rather irrelevant to adult humans, who have been exposed to a large number of infections (Beura et al. 2016). It has been claimed that important experimental results from modern animal facility conditions should be confirmed in animals with a more microbiologically experienced immune system, before any inferences regarding humans are drawn (Stappenbeck and Virgin 2016). It is therefore tempting to suggest that our results from Staphylococcus-carrying rats might be more relevant to humans.

On the other hand, the role of the immune status in the present study suggests that the mechanisms of action are more complex than previously thought. PRP has been described as a cocktail of growth factors that simply accelerate growth. This theory is refuted by our failure to produce an effect in clean animals, in which we can readily accelerate healing by loading or trauma (Aspenberg and Virchenko 2004, Virchenko and Aspenberg 2006, Virchenko et al. 2006, Hammerman et al. 2014). The facts that the early tendon callus consists mainly of leukocytes, and that other means of stimulating healing have strong effects on inflammation-related genes and leukocyte composition, also make a direct growth factor effect unlikely. A new model to explain the effect of PRP in tendon healing requires that inflammation is taken into account in ways that we do not know. This makes it difficult to translate results in our model to humans.

A weakness of this study is that the positive response to PRP in the Staphylococcus carriers was not confirmed, even though the interaction between bacterial status and PRP was highly significant. The rats were not randomized between bacterial contamination or not, as this was the result of different breeding conditions, but the breeder took measures to keep the different breeding houses genetically similar. The analysis of CD8a T-cells was less comprehensive than that of Reinke et al. (2013), and differences between mice and rats preclude direct comparisons. Still, the immune system in the contaminated and the pathogen-free rats was clearly different.

This is the first study to suggest a possible interaction between microbiota and tendon healing. The effect of PRP in human conditions remains dubious.

Supplementary data

Tables 2 and 3 are available as supplementary data in the online version of this article, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17453674.2017.1293447.

FD and PA planned the study with some contributions from JBS and VFB. FD, MH, and PB conducted the animal experiments. LT analyzed and interpreted the flow cytometry. PA and FD did the data analysis and wrote the manuscript.

We conducted this study during a scholarship supported by CAPES—the Brazilian Federal Agency for Support and Evaluation of Graduate Education within the Ministry of Education of Brazil, at Linköping University.

The study was funded by the Swedish Research Council (VR 02031-47-5), Centrum för idrottsforskning, Linköping University, and Östergötland County Council.

No competing interests declared.

Supplementary Material

References

- Aspenberg P, Ranstam J.. Platelet-rich plasma for chronic tennis elbow: letters to the editor. Am J Sports Med 2014; 42 (1): NP1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aspenberg P, Virchenko O.. Platelet concentrate injection improves Achilles tendon repair in rats. Acta Orthop 2004; 75 (1): 93–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beura L K, Hamilton S E, Bi K, Schenkel J M, Odumade O A, Casey K A, Thompson E A, Fraser K A, Rosato P C, Filali-Mouhim A, Sekaly R P, Jenkins M K, Vezys V, Haining W N, Jameson S C, Masopust D.. Normalizing the environment recapitulates adult human immune traits in laboratory mice. Nature 2016; 532 (7600): 512–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomgran P, Blomgran R, Ernerudh J, Aspenberg P.. A possible link between loading, inflammation and healing: Immune cell populations during tendon healing in the rat. Sci Rep 2016; 6: 29824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vos R J, Windt J, Weir A.. Strong evidence against platelet-rich plasma injections for chronic lateral epicondylar tendinopathy: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med 2014; 48 (12): 952–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliasson P, Andersson T, Aspenberg P.. Achilles tendon healing in rats is improved by intermittent mechanical loading during the inflammatory phase. J Orthop Res 2012a; 30 (2): 274–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliasson P, Andersson T, Aspenberg P.. Influence of a single loading episode on gene expression in healing rat Achilles tendons. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2012b; 112 (2): 279–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliasson P, Andersson T, Hammerman M, Aspenberg P.. Primary gene response to mechanical loading in healing rat Achilles tendons. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2013; 114 (11): 1519–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammerman M, Aspenberg P, Eliasson P.. Microtrauma stimulates rat Achilles tendon healing via an early gene expression pattern similar to mechanical loading. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2014; 116 (1): 54–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinke S, Geissler S, Taylor W R, Schmidt-Bleek K, Juelke K, Schwachmeyer V, Dahne M, Hartwig T, Akyuz L, Meisel C, Unterwalder N, Singh N B, Reinke P, Haas N P, Volk H D, Duda G N.. Terminally differentiated CD8(+) T cells negatively affect bone regeneration in humans. Sci Transl Med 2013; 5 (177): 177ra36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schepull T, Kvist J, Norrman H, Trinks M, Berlin G, Aspenberg P.. Autologous platelets have no effect on the healing of human achilles tendon ruptures: a randomized single-blind study. Am J Sports Med 2011; 39 (1): 38–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stappenbeck T S, Virgin H W.. Accounting for reciprocal host-microbiome interactions in experimental science. Nature 2016; 534 (7606): 191–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virchenko O, Aspenberg P.. How can one platelet injection after tendon injury lead to a stronger tendon after 4 weeks? Interplay between early regeneration and mechanical stimulation. Acta Orthop 2006; 77(5): 806–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virchenko O, Grenegard M, Aspenberg P.. Independent and additive stimulation of tendon repair by thrombin and platelets. Acta Orthop 2006; 77 (6): 960–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.