Abstract

Background and purpose

Pediatric fracture incidence may not be stable. We describe recent pediatric fracture epidemiology and etiology and compare this to earlier data.

Patients and methods

The city of Malmö (population 271,271 in 2005) in Sweden is served by 1 hospital. Using the hospital diagnosis registry, medical charts, and the radiographic archive, we identified fractures in individuals <16 years that had occurred during 2005 and 2006. We also retrieved previously collected fracture data from between 1950 and 1994, from the hospital’s pediatric fracture database. We used official population data to estimate period-specific fracture incidence (the number of fractures per 105 person-years) and also age- and sex-adjusted incidence. Differences are reported as rate ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals.

Results

The pediatric fracture incidence during the period 2005–2006 was 1,832 per 105 person-years (2,359 in boys and 1,276 in girls), with an age-adjusted boy-to-girl ratio of 1.8 (1.6–2.1). Compared to the period 1993–1994, age-adjusted rates were unchanged (RR =0.9, 95% CI: 0.8–1.03) in 2005–2006, with lower rates in girls (RR =0.8, 95% CI: 0.7–0.99) but not in boys (RR =1.0, 95% CI: 0.9–1.1). We also found that the previously reported decrease in unadjusted incidence in Malmö from 1976–1979 to 1993–1994 was based on changes in demography, as the age-adjusted incidences were similar in the 2 periods (RR =1.0, 95% CI: 0.9–1.1).

Interpretation

In Malmö, pediatric fracture incidence decreased from 1993–1994 to 2005–2006 in girls but not in boys. Changes in demography, and also other factors, influence the recent time trends.

Each year, 1 child in every 4 sustains traumatic injury that require medical attention, and almost 20% of pediatric trauma cases in an emergency department are treated for fractures (Hedström et al. 2012).

We have reported an increase in pediatric fracture incidence from 1950 to 1979 in the city of Malmö, Sweden (Landin 1983), but a decline during the following 15 years (Tiderius et al. 1999). No age adjustment was used in these studies, however, and the results may therefore entirely, partly, or not at all reflect changes in demography.

The information that is available regarding time trends in pediatric fracture incidence is limited and conflicting. While a Swedish study found an increase in pediatric fracture incidence from 1998 to 2007 (Hedström et al. 2010), a Finnish study found a decrease from 1983 to 2005 (Mayranpaa et al. 2010). However, different fracture ascertainment methods in the 2 studies make direct comparisons difficult.

In order to allocate future healthcare resources, it is essential to use the same fracture ascertainment system to facilitate identification of changes in fracture occurrence and to take changes in demography during the period of examination into account.

With this in mind, we aimed to (1) describe recent pediatric fracture epidemiology including etiology in Malmö and compare this to data from as far back as 1950; (2) describe changes in age- and sex-adjusted pediatric fracture incidences, to identify time trends independent of changes in demographics.

Patients and methods

Background information

Malmö is the third largest city in Sweden, with a population of 271,271 inhabitants (45,910 < 16 years of age) in the year 2005 and 276,244 inhabitants in 2006 (46,429 < 16 years of age) (Statistics Sweden 2007). Virtually all trauma care in the city is provided by the emergency department of the only hospital, and all referrals, radiographs, and reports have been saved for the past 100 years (Herbertsson et al. 2009).

Earlier data from 1950 to 1994

Until year 2001, all radiographs were sorted according to diagnosis, anatomical region, and year of injury. This archive has previously been used to identify fractures and to set up a pediatric fracture database including fractures sustained in city residents in the years 1950, 1955, 1960, 1965, 1970, 1975–1979 (Landin 1983) and 1993–1994 (Tiderius et al.1999). These previous reports have not included age- and gender adjustments, and it is therefore not known whether the time trends described earlier depended entirely, partly, or not at all on changes in demography. From the existing database, we included all fractures in children aged <16 years except those of the skull and sternum.

New data from 2005–2006

In 2001, the hospital switched from physical to digital radiographic films and set up a new archive. This archive includes all radiographs taken within the general healthcare system of the region. However, the radiographs are no longer classified according to diagnosis but according to the unique 10-digit national personal identity number of the patient. To identify pediatric fracture cases in 2005–2006 we performed searches in the digital in- and outpatient diagnosis records at the Emergency Department and the Departments of Orthopedics, Hand Surgery, and Otorhinolaryngology of the hospital. Records included met the following criteria: (1) ICD-10 fracture diagnoses S02.3–S02.4, S02.6–S02.9, S12.0–S12.2, S12.7, S22.0, S32.0–S32.8, S42.0–S42.9, S52.0–S52.9, S62.0–S62.8, S72.0–S72.9, S82.0–S82.9, and S92.0–S92.9; (2) patient age <16 years; and (3) city residency at the fracture event. We identified 4,459 visits. All visits for each individual patient (identified by the personal identity number) were reviewed (medical charts, referrals, and reports from each radiograph) to verify any fracture. If the fracture diagnosis was unclear, the original radiographs were re-reviewed before any fracture was registered. That is, as in the previous publications (Landin 1983, Tiderius et al. 1999), we only included objectively verified fractures. The ascertainment method with chart reviews allowed us—as in historical reports—to preclude double counting of fractures (due to multiple visits or multiple sequential radiographs).

For each verified fracture, we registered the age and sex of the patient, the date of fracture, fractured region, fracture side, injury mechanism, and injury-related activity. We used the same registration protocol as in the previous studies (that evaluated the period 1950–1994) (Landin 1983, Tiderius et al. 1999), and thus registered multiple fractures as independent fractures and re-fractures as new fractures. Multiple fractures of the fingers, toes, and metacarpals were, however, registered as a single fracture—as in previous studies.

Validation

To validate the 2005–2006 ascertainment method, 1 author (VL) reviewed all digital skeletal radiographs (irrespective of referral unit or reason for referral) performed on city residents <17 years of age, during the period January 1, 2005 to February 28, 2005. The review identified 103 fractures. A search for childhood fracture diagnoses in the digital hospital inpatient and outpatient records during the same 2 months also identified 103 fractures. When comparing the 2 methods, 100 fractures were identified by both methods while 3 fractures were only identified by 1 of the methods. This represents a misclassification rate of 3%.

Statistics

We used Microsoft Excel 2010 for data management and statistical calculations. Data are presented as numbers, mean incidences per 105 person-years, or as proportions (%) of all fractures. From the complete dataset, which was comprised of data from 2005–2006 and previously examined years (Landin 1983, Tiderius et al. 1999), we estimated the total and sex-specific incidence rates per 105 person-years during each period. Population at risk (city residents <16 years) during each period were derived from official records. To estimate age- and gender-adjusted rates, we used direct standardization with the average population of the city of Malmö during the examined period (in 1-year classes) as reference. To evaluate time trends, we grouped fracture data from the previously examined years into 5 periods: 1950–1955, 1960–1965, 1970–1975, 1976–1979, and 1993–1994. Relative risk was estimated by rate ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals by the chi-square distribution. We considered p < 0.05 to represent a statistically significant difference.

Ethics, funding, and potential conflicts of interest

The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Review Board in Lund (reference number 2010/191) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Financial support for the study was provided by ALF, the Herman Järnhardt Foundation, the Greta and Johan Kock Foundation, and Region Skåne FoU. The sources of funding were not involved in the design, conduction, or interpretation of the study, or in the writing of the manuscript. None of the authors have any competing interests.

Results

During 2005–2006, we found 1,692 fractures (1,119 in boys and 573 in girls) in 1,615 children during 92,339 patient-years, corresponding to a fracture incidence of 1,832 per 105 person-years (2,359 per 105 in boys and 1,276 per 105 in girls), with an age-adjusted boy-to-girl ratio of 1.8 (95% CI: 1.6–2.1). Detailed data are presented in Figures 1 and 2 (see also Table 1, Supplementary data). Only 1.7% of fractures occurred in the axial skeleton, while 78.8% were in the upper extremities and 19.5% were in the lower extremities. In the upper extremity, the incidence of fractures on the left side was 13% higher than on the right side (RR =1.1, 95% CI: 1.01–1.3), while we found no such difference for the lower extremity (RR =1.0, 95% CI: 0.8–1.3).

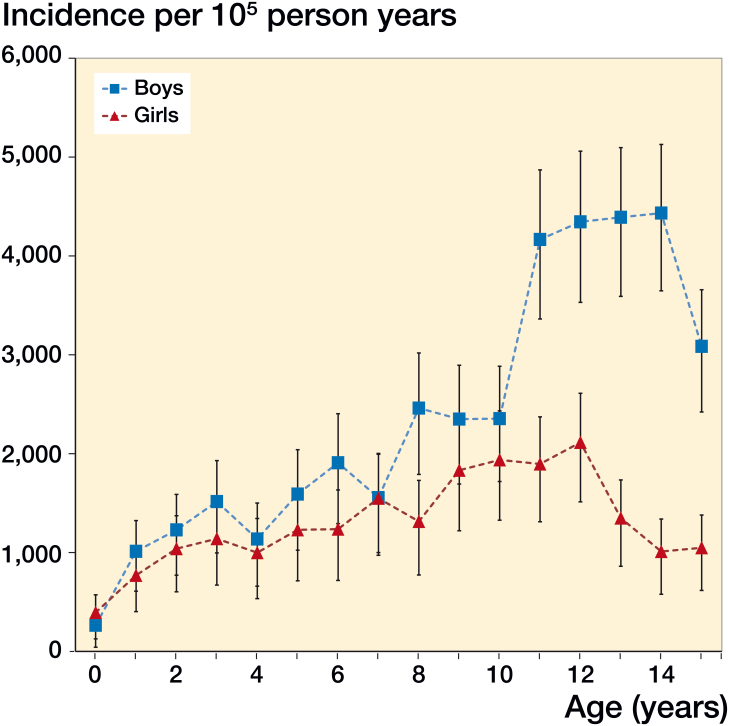

Figure 1.

Sex- and age-specifi c fracture incidence in 1-year classes during the period 2005–2006. Data are expressed as number of fractures per 105 person-years, with 95% CI.

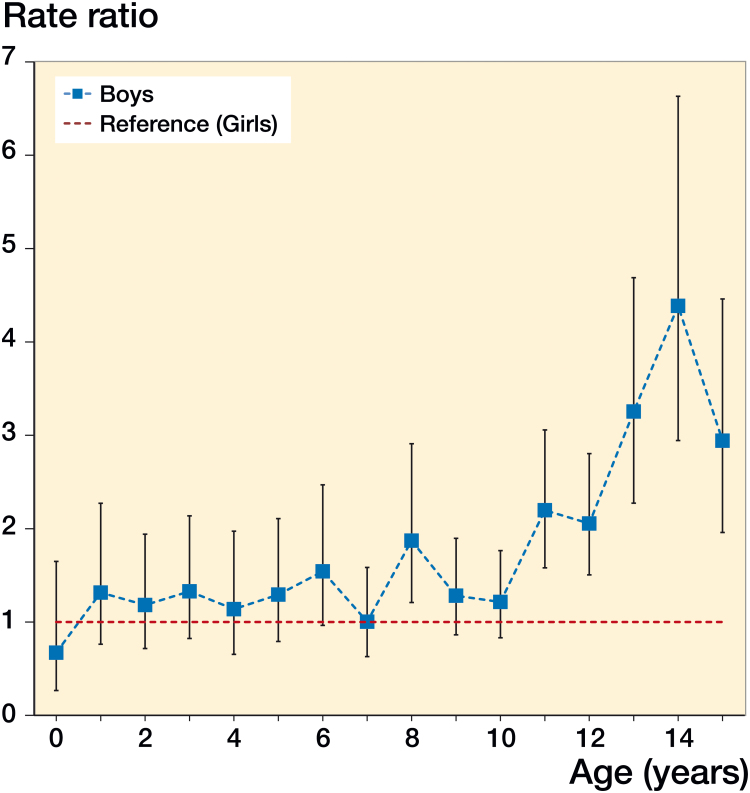

Figure 2.

Age-specifi c boy-to-girl rate ratio (RR) with 95% CI per 1-year age class during the period 2005–2006.

63 children had more than 1 fracture. These children had 140 fractures in total, corresponding to 2.2 fractures per child. Of these fractures, 106 occurred in 49 boys and 34 in 14 girls. 57 children (44 boys and 13 girls) had 2 fractures, 4 children (all boys) had 3 fractures, and 2 children (1 boy and 1 girl) had 6 fractures. Of the 140 fractures, 96 occurred at the first injury event, a further 41 at the second, 1 at the third, 1 at the fourth, and 1 at the fifth. 136 of 140 fractures involved the extremities and 4 the axial skeleton. Of 136 extremity fractures, 106 occurred in the upper and 30 in the lower extremity. The 5 most common locations for these fractures were the distal forearm (39 fractures, 29%), the metacarpals (12 fractures, 9%), the fingers (10 fractures, 7%), the clavicle (9 fractures, 7%), and the distal humerus (8 fractures, 6%).

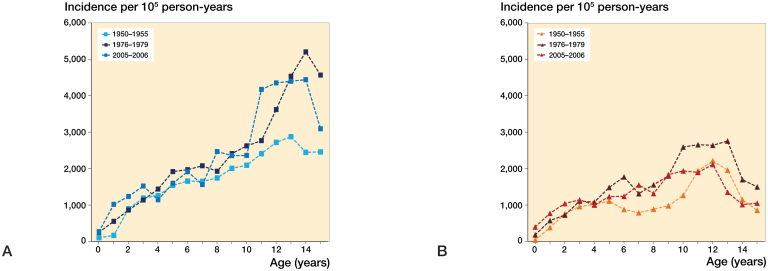

During 2005–2006, the age-specific fracture incidence increased by age in both sexes and reached a peak around the age of 14 years in boys and 12 years in girls (Figure 1). Boys and girls had similar fracture incidences until the age of 10 years, after which boys had higher incidences—by as much as 4 times (RR =4.4, 95% CI: 2.9–6.6) at the age of 14 (Figure 2).

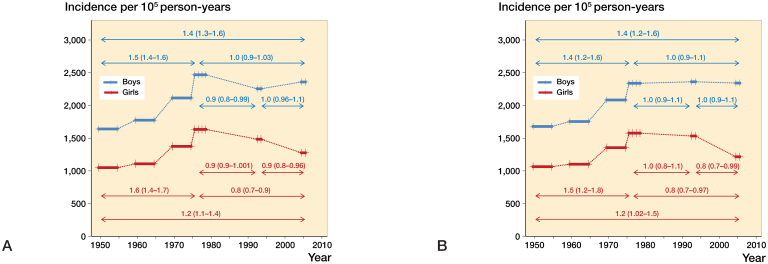

Compared to 1993–1994, age-adjusted overall rates were unchanged (RR =0.9, 95% CI: 0.8–1.03) in 2005–2006, with lower rates in girls (RR =0.8, 95% CI: 0.7–0.99) but not in boys (RR =1.0, 95% CI: 0.9–1.1). During the overall study period (1950–2006), the highest fracture incidence was found during the period 1976–1979. Between 1950–1955 and 1976–1979, the unadjusted fracture rate increased by about 50% (RR =1.5, 95% CI: 1.4–1.6) followed by a decrease by 11% until 2005–2006 (RR =0.9, 95% CI: 0.8–0.9). Details of absolute and age-adjusted changes are presented in Table 2, and sex-specific data are given in Figure 3. We also found that the previously reported decrease in unadjusted incidence from 1976–1979 to 1993–1994 was based on changes in demography, as the age-adjusted incidence was similar in the 2 periods (RR =1.0, 95% CI: 0.9–1.1)(Table 2).

Table 2.

Differences in unadjusted and age-adjusted fracture incidence in children between periods of interest in Malmö, Sweden, presented as rate ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs)

| Differences in fracture incidence between periods, RR (95% CI) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Denominator | 1950–1955 |

1976–1979 |

1993–1994 | ||

| Nominator | 2005–2006 | 1976–1979 | 2005–2006 | 1993–1994 | 2005–2006 |

| Unadjusted | 1.4 (1.3–1.5)a | 1.5 (1.4–1.6)a | 0.9 (0.8–0.9)a | 0.9 (0.9–0.97)a | 1.0 (0.9–1.04) |

| Age-adjusted | 1.3 (1.2–1.4)a | 1.4 (1.3–1.6)a | 0.9 (0.8–1.03) | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 0.9 (0.8–1.03) |

Statistically significant changes

Figure 3.

Sex-specifi c unadjusted (A) and age-adjusted (B) fracture incidence during different periods, from 1950 to 2006. Data are expressed as number of fractures per 105 person-years per period of examination, with thick line markers representing the number of years measured in the period. Rate ratios (RRs) between periods of interest are presented with 95% CI on arrows with pointer between the time periods compared.

Figure 4.

Age-specifi c fracture incidence in boys (A) and girls (B) during the periods 1950–1955, 1976–1979, and 2005–2006 in Malmö, Sweden. These 3 periods were selected as to show incidences at study start, during the period with highest incidence, and at study end. Data are incidences in 1-year age classes.

The most common injury mechanism in children during every period evaluated was a fall on the same plane, and—except in 1960–1965—the most common trauma-related activity was sports (Table 3, see Supplementary data). The fracture-related activity could not be determined in 683 cases (54%) in 1950–1955, 721 cases (48%) in 1960–1965, 651 cases (39%) in 1970–1975, 1,327 cases (40%) in 1976–1979, 518 cases (34%) in 1993–1994, and 499 cases (30%) in 2005–2006. The trauma mechanism could not be determined in 203 cases (16%) in 1950–1955, 139 cases (9%) in 1960–1965, 89 cases (5%) in 1970–1975, 155 cases (5%) in 1976–1979, 64 cases (4%) in 1993–1994, and 0 cases (0%) in 2005–2006.

Discussion

The previously reported decrease in overall pediatric fracture rate from 1975–1979 to 1993–1994 (Tiderius et al. 1999) has not continued from 1993–1994 to 2005–2006, where we found a decrease in girls, but not in boys. In the most recent period evaluated, the peak in fracture risk occurred 1–2 years earlier in girls than in boys, fractures in the upper extremities were 4 times more common than in the lower extremities, and more fractures occurred on the left side. We also found that the decrease in unadjusted fracture incidence from 1976–1979 to 1993–1994 was the result of changes in demography. In contrast, the decrease from 1993–1994 to 2005–2006 in girls depended on factors others than changes in demography.

Comparisons of rates for 2005–2006 with other studies

In the present study, the unadjusted pediatric fracture rate (< 16 years) was 1,832 per 105 person-years. A study in Northern Sweden found an age- and sex-adjusted incidence of 2,240 per 105 person-years in 2005 (Hedström et al. 2010) in individuals younger than 21 years. The difference may be due to the different age spans and the colder climate, with snow and ice in the north, but also other factors—some of which are discussed below. Differences in pediatric fracture rates in a single country have also been found in the UK, with rate ratios ranging from 1.0 to 1.7 between London and other regions (Cooper et al. 2004). In Helsinki, Finland, the unadjusted incidence of fractures in children (< 16 years) was 1,630 per 105 person-years in the year 2005 (Mayranpaa et al. 2010), which was lower than in our city (1,832 per 105 person-years). The notion that fracture rates differ between countries is further supported by the boy-to-girl unadjusted fracture ratio of 1.6 in Finland (Mayranpaa et al. 2010), 1.5 in Scotland (Rennie et al. 2007), and 1.9 in our study.

Comparisons of time trends

Previous studies from Malmö examining the period 1950–1955 to 1975–1979 have reported on trends in the unadjusted pediatric fracture incidence: mainly an increase until 1975–1979 (Landin 1983) and a decrease from 1975–1979 to 1993–1994 (Tiderius et al. 1999). When we re-examined these data, we found that the decrease from 1976–1979 to 1993–1994 occurred due to changes in demography. We also found that the decrease in girls from 1993–1994 to 2005–2006 was dependent of factors beyond changes in demography (since the age-adjusted incidence also decreased). A recent Finnish study found an 18% decrease in fracture rate in children under the age of 15 from 1983 to 2005 (Mayranpaa et al. 2010). This contrasts with a study in Northern Sweden, which found an increase in individuals younger than 20 years from 1993 to 2007 (Hedström et al. 2010). The reasons for the differences are unknown.

The decline in female pediatric fracture incidence in Malmö during the last period evaluated highlights the importance of continuously monitoring pediatric fracture epidemiology in order to predict and accurately allocate future healthcare resources. Changes in fracture occurrence during the last period were found in girls but not in boys, highlighting the necessity for sex-specific evaluation of fracture epidemiology.

Potential explanations for time trends and differences between regions

We speculate that differences in prevalence of overweight, exposure to trauma, social environment, and risk taking behavior may explain the different fracture incidences. There has also been a marked improvement in traffic safety during the period evaluated, reflected in a reduction in pediatric deaths from motor vehicle accidents (The National Board of Health and Welfare – Socialstyrelsen), which is also supported by our data regarding fracture etiology. Structured pediatric injury prevention in the home environment during the last 60 years may also have contributed, which is also supported by our data regarding fracture etiology. The generally lower level of physical activity in society today than earlier (Public Health Agency of Sweden 2008, 2011) may also have contributed. Children of today walk to school to a lesser extent, and screen time and media consumption have increased since the early 1990s (Public Health Agency of Sweden 2008, 2011). However, how this affects fracture risk is debatable, since both low and high levels of physical activity are associated with high fracture risk (Clark et al. 2008, Fritz et al. 2016).

The distribution of ethnicity in a population may also be of importance, since fracture risks may differ between ethnic groups (Moon et al. 2016). In the year 2005, 42% of Malmö children were of foreign background (i.e. were immigrants or had at least one parent who was immigrant), as compared to 9% in Northern Sweden (Statistics Sweden 2005). Time trends in immigration could also be important, since the proportion of immigrants in our region increased from 18% in 1993 to 26% in 2005 whereas the corresponding increase in the northern part of our country was only from 7% to 8% (Statistics Sweden 2006). More immigrants in Malmö originate from far-away countries, while the largest proportion in Northern Sweden come from Finland (Statistics Sweden 2006).

The proportion of children of foreign background in our city is higher than in some major Scandinavian cities, such as Copenhagen (26% in 2008) (Statistics Denmark 2016), Stockholm (24% in 2005) (Statistics Sweden 2006), and Oslo (one-third of all residents were of foreign background in January 2016) (Statistics Norway 2016) but is comparable to that in other OECD countries (Widmaier and Dumont 2011). Immigrants constitute up to 39% of the population in many major cities (for example, New York (US Census Bureau), Los Angeles (US Census Bureau), and London (Migrant Observatory)). We consider that our results are relevant to areas with a significant proportion of immigrants but that they are not directly generalizable to areas with an exclusively white native population.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of the study include the long study period in a defined region with detailed official annual population data and an ascertainment method allowing objective verification of all fractures without double counting. The main weakness was the transition in ascertainment method in 2005–2006 compared to earlier. Still, our validation against a gold standard indicated that only 3% of fractures were misclassified, which is similar to that with the previous method (Jonsson 1993). As in our previous studies, children who did not get any medical treatment for their fracture or children living in Malmö but only treated elsewhere for a fracture (both the primary treatment and all follow-up treatments) would not be registered. Most children in Sweden with fractures have been—and still are—referred to their home hospital for any follow-up. Thus, the same risk of misclassification has existed for all the years previously evaluated. It would also have been advantageous to adjust for changes in ethnicity in the population at risk, but these data were not available. Concerning fracture etiology, there was a high proportion of missing data that also differed between the different periods. The data presented in Table 3 should therefore be viewed with caution, and they are more suitable for comparisons of different categories within the same year rather than for comparisons over time.

Conclusion

Female pediatric fracture incidence has decreased in the new millennium, with factors other than changes in demography influencing the recent time trends. Future studies should examine even more recent time trends, preferably with information on patient-specific risk factors to reveal information on causal factors.

Supplementary data

Tables 1 and 3 are available as supplementary data in the online version of this article, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17453674.2017.1334284

VL, LL, BR, and MK designed the study. VL collected the 2005–2006 data. Historic data had previously been collected by LL and CJT. VL performed all calculations. VL wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and VL, BR, and MK finalized the manuscript. JÅN provided assistance with statistical calculations.

We thank Hans Eric Rosberg, Department of Hand Surgery, Skåne University Hospital, for his help with data collection concerning hand fractures.

Acta thanks Johannes Mayr and Ole Brink for help with peer-review of this study.

Supplementary Material

References

- Clark E M, Ness A R, Tobias J H.. Vigorous physical activity increases fracture risk in children irrespective of bone mass: a prospective study of the independent risk factors for fractures in healthy children. J Bone Miner Res 2008; 23 (7): 1012–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper C, Dennison E M, Leufkens H G, Bishop N, van Staa T P.. Epidemiology of childhood fractures in Britain: a study using the general practice research database. J Bone Miner Res 2004; 19 (12): 1976–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz J, Coster M E, Nilsson J A, Rosengren B E, Dencker M, Karlsson M K.. The associations of physical activity with fracture risk-a 7-year prospective controlled intervention study in 3534 children. Osteoporos Int 2016; 27(3): 915–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedström E M, Svensson O, Bergström U, Michno P.. Epidemiology of fractures in children and adolescents. Acta Orthop 2010; 81 (1): 148–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedström E M, Bergström U, Michno P.. Injuries in children and adolescents–analysis of 41,330 injury related visits to an emergency department in northern Sweden. Injury 2012; 43 (9): 1403–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbertsson P, Hasserius R, Josefsson P O, Besjakov J, Nyquist F, Nordqvist A, et al. . Mason type IV fractures of the elbow: a 14- to 46-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2009; 91 (11): 1499–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson B. Life style and fracture risk. Thesis. University of Lund; 1993: p. 67. [Google Scholar]

- Landin L A. Fracture patterns in children. Analysis of 8,682 fractures with special reference to incidence, etiology and secular changes in a Swedish urban population 1950-1979. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl 1983; 202: 1–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayranpaa M K, Makitie O, Kallio P E.. Decreasing incidence and changing pattern of childhood fractures: A population-based study. J Bone Miner Res 2010; 25 (12): 2752–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon R J, Harvey N C, Curtis E M, de Vries F, van Staa T, Cooper C.. Ethnic and geographic variations in the epidemiology of childhood fractures in the United Kingdom. Bone 2016; 85: 9–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Agency of Sweden The childs environment for physical activity, page 17.; 2008; Cited July 2016; Available from: https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/pagefiles/12226/R200833_barns_miljoer_for_fysisk_aktivitet_webb.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Agency of Sweden School age children related to physical activity; 2011; Cited July 2016; Available from: https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/pagefiles/12635/A2011-06-Skolbarns-halsovanor-fysakt-tv-dator-Ett-friskare-Sverige.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Rennie L, Court-Brown C M, Mok J Y, Beattie T F.. The epidemiology of fractures in children. Injury 2007; 38 (8): 913–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migrant Observatory Migrants in the UK: An Overview; Available from: http://www.migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Briefing-Migrants_UK_Overview.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Denmark Population at the first day of the quarter by sex, region, time, age and ancestry. 2016; Cited July 2016; Available from: http://www.statbank.dk/statbank5a/SelectVarVal/Define.asp?Maintable=FOLK1E&PLanguage =1 [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Norway Immigrants and Norwegian-born to immigrant parents, 1 January 2016; 2016; Cited July 2016; Available from: http://www.ssb.no/en/innvbef. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Sweden Population statistics 1993 part 3, Pages 166-167, 172-173; 1993; Cited July 2016; Available from: http://www.scb.se/H/SOS%201911-/Befolkningsstatistik/Befolkningsstatistik%20Del%203%20Folkm%C3%A4ngden%20efter%20k%C3%B6n%20%C3%A5lder%20medborgarskap%20%28SOS%29%201991-2001/Befolkningsstatistik-1993-3-Folkmangden-kon-alder-medborgarskap.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Sweden Children of Foreign background in Malmö and Umeå 2005; Cited July 2016; Available from: http://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/sq/25063. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Sweden Tables of Sweden’s population 2005, Pages 158-159, 164-165; 2006; Cited July 2016; Available from: http://www.scb.se/statistik/_publikationer/be0101_2005a01_br_be0106tab.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Sweden Child population in the city of Malmö in one year classes, December 31st 2005/2006; 2007; Cited July 2016; Available from: http://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/sq/1052. [Google Scholar]

- The National Board of Health and Welfare – Socialstyrelsen Causes of death, free search; Cited July 2016; Available from: http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/statistics/statisticaldatabase/causeofdeath. [Google Scholar]

- Tiderius C J, Landin L, Duppe H.. Decreasing incidence of fractures in children: an epidemiological analysis of 1,673 fractures in Malmö, Sweden, 1993–1994. Acta Orthop Scand 1999; 70 (6): 622–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Census Bureau Selected Characteristics of the Native and Foreign-Born Populations - Los Angeles City 2014; 2015; Cited July 2016; Available from: http://factfinder.census.gov/bkmk/table/1.0/en/ACS/14_5YR/S0501/ 1600000US0644000. [Google Scholar]

- US Census Bureau Selected Characteristics of the Native and Foreign-Born Populations - New York City 2014; 2015; Cited July 2016; Available from: http://factfinder.census.gov/bkmk/table/1.0/en/ACS/14_5YR/S0501/1600000US3651000. [Google Scholar]

- Widmaier S, Dumont J. Are Recent Immigrants Different? A New Profile of Immigrants in the OECD based on DIOC 2005/06; 2011; OECD Publishing. Available from: http://www.oecd.org/migration/49205584.pdf. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.