Abstract

Background

Working the night shift interferes with the circadian chronobiological rhythm, causing sleep disturbances, fatigue, and diminished well-being, and increases the risk of serious disease. The question whether night work increases the risk of depression has not been adequately studied to date.

Methods

We carried out a systematic, broadly conceived literature search in the PubMed, Scopus, PsycINFO, and PSYNDEX databases and the Medpilot search portal on the topic of nighttime shift work and mental illness.

Results

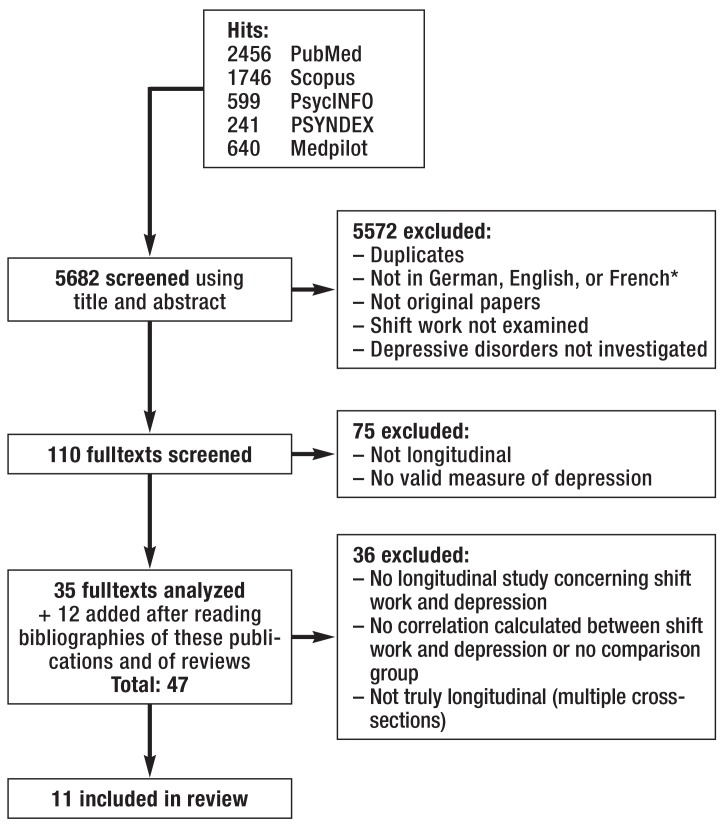

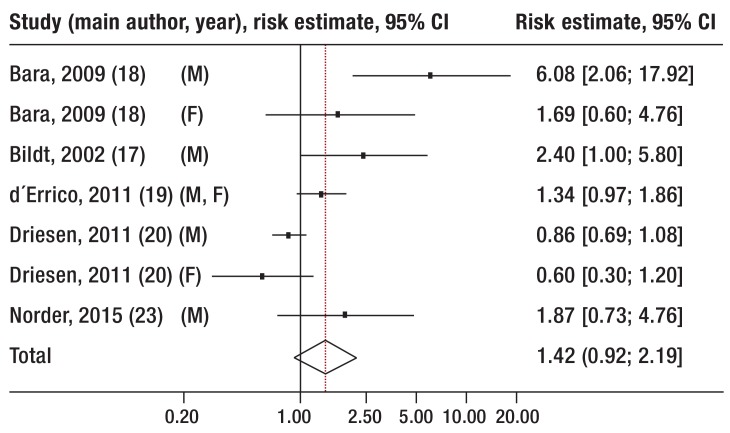

The search yielded 5682 hits, which were narrowed down by predefined selection criteria to 11 high-quality longitudinal studies on the relationship between nighttime shift work and depressive illness. Only these 11 studies were subjected to further analysis. 3 of 4 studies on nighttime shift work in the health professions (almost exclusively nursing) revealed no association with depression over an observation period of two years. On the other hand, 5 studies on nighttime shift work in occupations outside the health sector, with observation periods of two or more years, yielded evidence of an elevated risk of depression after several years of nighttime shift work, but not in any uniform pattern. A supplementary meta-analysis of 5 of the studies revealed a 42% increase of the risk of depression among persons working the night shift (95% confidence interval [0.92; 2.19]). Psychosocial working conditions that have a negative influence on health partially account for these associations.

Conclusion

Although there is evidence that nighttime shift work (at least, in occupations outside the health sector) does increase the risk of depression, this evidence is not strong enough to sustain a general medical recommendation against shift work for employees with depressive conditions. It would seem appropriate to address this question on an individual basis, with strong support from physicians and close attention to the deleterious psychosocial factors associated with shift work.

Approximately 14% of the German workforce work at night—defined as between 11 p.m. and 6 a.m.—at least occasionally, and 15% work alternating shifts, e.g. early shift and late shift or early shift, late shift, and night shift (1). Shift work is associated with increased physical and psychological strain in the short term, and in the long term it increases the risk of serious illness. Although scientific debate has not yet reached a clear conclusion, particularly regarding cancers, recent meta-analyses show an increased risk of coronary heart disease (relative risk: 1.23; 95% confidence interval: [1.15; 1.31]) (2), diabetes mellitus (odds ratio: 1.09; [1.05; 1.12]) (3), metabolic syndrome (relative risk: 1.57; [1.24; 1.98]) (4), and cancer (relative risk: 1.19; [1.05; 1.35]) (5), particularly breast cancer (relative risk: 1.089; [1.016; 1.166]) (6, 7).

Those who work shifts do not work and sleep in line with their endogenous circadian rhythm, so biological and social time are misaligned. This is essentially what happens after a swift journey through multiple time zones and is therefore also known as „social jetlag“ (e1). The endogenous circadian rhythm determines the need for sleep and wakefulness, body temperature, heart rate, blood pressure, and hormone levels, particularly levels of cortisol and melatonin (e2). Exogenous influences known as zeitgebers, such as light in the light-dark cycle of a 24-hour day, synchronize the endogenous circadian rhythm with the astronomical solar day (e3). Although any change to the phases of waking and sleeping caused by shift work does affect the endogenous chronobiological rhythm, external zeitgebers are dominant. Chronobiological adaptation of the sleep-wake cycle in those who work night shifts is therefore usually inadequate (e4, e5). Total melatonin production over the 24-hour day is reduced by nocturnal light exposure; this also plays a role in the risk of breast cancer (5) (e6). Disrupted cortisol regulation is thought to play an important role in arteriosclerotic diseases such as coronary heart disease (e7). As an additional consequence of disrupted circadian rhythm, a reduction in mean length of sleep by one hour or more—particularly in those who work night shifts, but to a lesser extent also in those who work early shifts (e8)—can increase the activity of the sympathetic nervous system and systemic inflammatory precursors (e9). Independently of its biological effects, shift work is often associated with psychosocial strain (e10) or less healthy behavior (e11, e12).

The most recent review on the effects of shift work on mental health and affective symptoms is a scoping review performed by Germany‘s Federal Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (Bundesanstalt für Arbeitsschutz und Arbeitsmedizin) (8), which is based on reviews and original articles, especially cross-sectional studies. The authors of the scoping review conclude that findings vary, particularly regarding alternating shifts. According to the review, there seems to be a tendency for night work to be associated with adverse consequences for mental health, most commonly manifesting as acute or chronic exhaustion (8). Although there are clear correlations between disrupted chronobiology and mental illness (9), as yet the effect of shift work that includes night shifts on the onset or exacerbation of specific mental illnesses, particularly depression, remains unclear.

This systematic review therefore focuses on how shift work affects the onset and progression of depression. It is based on prospective studies, as only these allow conclusions to be drawn on potential causes and effects.

Method

Literature search and selection

In order to include both medical and psychological literature, the literature search in October 2015 involved the databases PubMed, Scopus, PsycINFO, and PSYNDEX, as well as the search platform Medpilot. No limit was placed on year of publication. Terms such as „burnout,“ „common mental disorders,“ and „mental illness“ in connection with shift work were included. There were 5682 hits in total (etable 1). These were selected according to the following criteria, on the basis of their titles and, where appropriate, abstracts:

eTable 1. Search strategy to identify relevant articles*.

| Population | Working individuals |

| Intervention/exposure | Shift work that includes work between 11 a.m. and 6 p.m. |

| Control/comparison group | - No shift work - Varying frequency of night shifts |

| Outcome | Depression, measured using: - A valid questionnaire, e.g. BDI, HADS, GHQ, CES-D, HAM-21, POMS, etc. or - Tool/questions sufficiently described and clinically appropriate or - Another valid indicator of depressive illness, e.g. self-reported diagnosis by physician, health insurance information, etc. |

| Study type | Longitudinal studies: cohort study, case-control study, quasi-experimental study |

| Languages | German, English, French |

| Study period | Start of database to October 2015 |

| Search terms | (shift work* OR shiftwork* OR evening shift* OR night shift* OR extended shift* OR irregular shift* OR fixed shift* OR roster shift*) OR „extended work shifts“ OR „extended work shift“ OR ((circadian OR „biological clock“ OR morningness OR eveningness OR chronobiology OR „circadian rhythm“ OR chronotype OR „sleep-wake cycle“ OR „sleep-wake schedule“) AND disrupt*) OR „work time“ OR „work* schedule*“ OR „shift duration*“ OR „night work“ OR „weekend work“ OR „irregular work“ OR „rotating night shift*“ OR „shift systems“ OR „Work schedule“ OR „Working time“ OR „Work Scheduling“ OR „Workday Shifts“ AND „Depression“ OR „Depressive Disorder“ OR „Depressive Disorder, Major“ OR „Bipolar Disorder“ OR „Adjustment Disorders“ OR „Anxiety“ OR „Anxiety disorder“ OR „Somatoform Disorder“ OR „somatic symptom disorder“ OR „Conversion Disorder“ OR „illness anxiety disorder“ OR „pain disorder“ OR „undifferentiated somatic symptom disorder“ OR „Mental Disorder“ OR „burnout“ OR „mental illness“ OR „emotional disorder“ OR „emotional instability“ |

| Limitations | - Shift work inseparable from other working conditions that potentially foster depression (e.g. nighttime work in combination with excessively long working hours for doctors) - Outcome mental illness, depression could not be separated from others - Correlation between exposure and target parameter not statistically quantified |

| Databases and search technique | - PubMed, PsycINFO: „all fields“ - Scopus, PSYNDEX: „title and abstract“ - Medpilot (5 searches): „shiftwork“ AND „depression,“ „anxiety,“ „burnout,“ „somatoform“ AND „bipolar“ |

| Total hits | 5682 |

| Other selection procedures | Figure |

*According to PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome); BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; GHQ: General Health Questionnaire;

CES-D: Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale; HAM-21: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, 21 items; POMS: Profile of Mood States

Population: working individuals

Exposure: shift work that included night work between 11 p.m. and 6 a.m.

Comparison group: individuals working during the day or with a varying frequency of night shifts

Outcome: depression measured using a valid method or another valid indicator of a depressive disorder (etable 1)

In addition, studies in which shift work could not be separated from other working conditions that were harmful to health, those in which multiple mental illnesses were target parameters, those in which depressive disorders could not be clearly defined, and those with no statistical analysis on the correlation between shift work and depression were not included. Selection was always performed by 2 of the authors.

The bibliographies of the 35 original papers, the scoping review (8), and the 3 earlier relevant reviews on shift work and mood disorders (10– 12) that remained after several stages of selection were examined to see if any other studies could be identified from them. Of the 47 suitable fulltexts, 11 original papers were included (figure). Data was extracted by 2 authors independently of each other and according to a pre-established evaluation plan (Table 1, extended version in eTable 2) and presented in Table 1. No subgroup analysis was initially planned. Multiple evaluations or publications based on the same cohort but examining different aspects were selected (Table 1, extended version in eTable 2) but were included in the evaluation only once. The studies were rated for risk of bias according to the criteria stated in the Quality in Prognosis Studies (QUIPS) checklist and in line with published measures (13, 14) that had already been used in reviews on shift work that examined other target parameters (15). As recommended (14), scoring was not used (table 2).

Figure.

Flow diagram for study selection

*312 publications were initially excluded for reasons of language.

Table 1. Longitudinal studies on the correlation between shiftwork that includes night shifts and depressive disorders.

| Main author, year | n | Sample | Country | Measure of depression | When measured | Included in meta-analysis | Correlation between shift work and depression |

| Bara, 2009 (18) |

9765 | Representative sample drawn from private households in the British Household Panel Survey, 1995 to 2005 Women: 53.3% Men: 46.7% |

UK | GHQ-12 | Measured 11 times (annually, 1995 to 2005) | Yes | Increased depression in: Men after >4 years on night shifts OR: 6.08; 95% CI: [2.06; 17.92] Women after >4 years on various shifts OR: 2.58; 95% CI: [1.53; 4.35] |

| Berthelsen, 2015* (25) |

t1: 2059 t2: 1582 |

Nurses (list of members of the Norwegian Nurses‘ Organization) Women: 90.9% Men: 9.1% |

Norway | HADS | Measured twice (baseline: 2008/2009; follow-up: 12 months later) | No | No correlation |

| Bildt, 2002 (17) |

420 | General Swedish population Women: 53% Men: 47% |

Sweden | Interview conducted by psychologists, assessment according to DSM-III-R criteria GHQ-12 | Measured twice (1993 and 1997) | Yes | Increased depression in: Women (bivariate and multivariate analyses): RR: 2.4; 95% CI: [1.0; 5.8] Men (univariate analyses only): RR: 2.2; 95% CI: [1.0; 5.2], multivariate not significant |

| Bohle, 1989 (16) |

60 | Nurses Women: 100% |

Australia | GHQ-12 | Measured 3 times (immediately after being hired, i.e. before start of shift work, and after 6 and 15 months) | No | Increased depression after switching to system with night shifts |

| d’Errico, 2011 (19) |

2105 | Members of an Italian labor union Women: 23% Men: 77% |

Italy | Indirectly via prescription of antidepressants | Measured twice (baseline: 1999 to 2000; follow-up: 2005) | Yes | Increased depression in subgroup of white-collar workers onlyRR: 2.58; 95% CI: [1.30; 5.11] |

| Driesen, 2011 (20) |

8178 | Employees of 45 different companies and organizations, drawn from the Maastricht Cohort Study Women: 18/10% Men: 82/90% (daytime work/shift work) |

The Netherlands | Psychiatric interview (screening question concerning depression)HPQ | Measured 3 times (1-, 2– and 10-year follow-up; baseline: 1998; last follow-up: 2008) | Yes | Increased depression in: Men: HR: 1.22; 95% CI: [1.02; 1.46] Men ≥ 45: HR: 1.37; 95% CI: [1.01; 1.86] (unadjusted) Difference disappears after adjustment for demographic and psychosocial working conditions |

| Flo, 2014* (24) |

1224 | Nurses (list of members of the Norwegian Nurses‘ Organization) Women: 90.3% Men: 9.7% |

Norway | HADS | Measured twice (baseline; follow-up at 1 year) | No | No correlation between no. of quick returns and anxiety or depression |

| Lin, 2012 (22) |

407 | Nurses Women: 100% |

Taiwan | GHQ-12 | Measured twice (nurses working shifts only; baseline: July 2005 to October 2005; follow-up: 6 to 10 months later) | No | No correlation (no change in frequency of depression with change in no. of night shifts) |

| Nabe-Nielsen, 2011 (26) |

2148 | Assistants and auxiliaries training in social and health services Women: 96.6/94.9% Men: 4.4/5.1% (daytime work/shift work) |

Denmark | Copsoq Mental Health (depression, questions on anxiety, melancholy, good mood) | Measured 3 times (baseline: 2004; follow-up: 2005 and 2006) | No | No correlation overall No difference between shift workers and night shift workers with no control over work schedule planning Lower risk of depression with shift work plus control over work schedule planning |

| Norder, 2015 (23) |

5826 | Industrial manufacturing employees (steel working) Men: 100% |

The Netherlands | Time off work due to mental illness (emotional disorders ICD-10 R45 or psychological and behavioral disorders ICD-10 F00 to F99) | All time off work recorded over 10 years, mean follow-up 7.7 years (SD: 3.0 years) (register of workplace medical service) | Yes | No correlation overall No difference between shift workers and daytime workers in new-onset time off work due to mental illness in general, insignificant increase in new-onset time off work due to mood disorders HR: 1.87; 95% CI: [0.73; 4.76] |

| Thun, 2014* (21) |

633 | Nurses (list of members of the Norwegian Nurses‘ Organization)Women: 100% | Norway | HADS | Measured 3 times (winter 2009, 2010, 2011)º | No | No correlation (correlation between switch from night shift to day shift and reduced depression) |

*3Publications based on the same cohort: evaluation includes only the paper by Thun et al. (21), to represent all of them.

Copsoq: Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire; DSM-III-R: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; GHQ-12: General Health Questionnaire; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HPQ: World Health Organization‘s Health and Work Performance Questionnaire; HR: Hazard ratio; ICD: International Classification of Diseases; CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; RR: Relative risk; SD: Standard deviation

eTable 2. Extended version: longitudinal studies on the correlation between shiftwork that includes night shifts and depressive disorders.

| Main author, year | n | Sample | Country | Response rate | Compared groups/shift systems | Measure of depression | When measured | Statistical analysis | Adjustment | Included in meta-analysis | Correlation between shift work and depression |

| Bara, 2009 (18) |

9765 | Representative sample drawn from private households in the British Household Panel Survey, 1995 to 2005 Women: 53.3% Age, years: 21 to 25: 8.5% 26 to 34: 21.8% 35 to 44: 26.8% 45 to 54: 21.8% 55 to 64: 16.6% 65 to 73: 4.4% Men: 46.7% Age, years: 21 to 25: 9.4% 26 to 34: 21.3% 35 to 44: 26.3% 45 to 54: 21.3% 55 to 64: 16.1% 65 to 73: 5.7% (No information on age or sex, distributed in line with comparison groups) |

UK | 2003: 64.9% 1995: 77.3% |

Night shift or alternating shifts versus daytime work, stratified by sex | GHQ-12 | Measured 11 times (annually, 1995 to 2005) | Logistic regression | Age, relationship status, training, years‘ work in 6 occupational categories, professional experience, baseline GHQ score | Yes | Increased depression in: Men after >4 years on night shifts OR: 6.08; 95% CI: [2.06; 17.92] Women after >4 years on various shifts OR: 2.58; 95% CI: [1.53; 4,35] |

| Berthelsen, 2015* (25) |

t1: 2059 t2: 1582 |

Nurses (list of members of the Norwegian Nurses‘ Organization) Women: 90.9% Men: 9.1% Mean age: 33.1 years (21 to 63, SD = 8.2 (data from Thun et al. [21]) Age: <30: 38.1% 30 to 39: 42.7% 40 to 49: 13.7% 50 to 59: 5.1% 59: 0.4% (No information on age or sex, distributed in line with comparison groups) |

Norway | Baseline: 38.1% Wave 2: 76.8% |

Night shift only versus 3-shift system (day shift, evening shift, night shift) versus 2-shift system (day shift, evening shift) versus daytime work only | HADS | Measured twice (baseline: 2008/2009; follow-up: 12 months later) |

Bivariate binary logistic regression, ANOVA | Age, sex, relationship status, children living at home, anxiety and depression at baseline | No | No correlation |

| Bildt, 2002 (17) |

420 | General Swedish population Women: 53% Men: 47% Age: 42 to 58 years (No information on age or sex, distributed in line with comparison groups) |

Sweden | 1993: 62% 1997: 87% |

Shift work (6 different shift types, including night shift at that time) versus daytime work | Interview conducted by psychologists, assessment according to DSM-III-R criteria GHQ-12 |

Measured twice (1993 and 1997) | Bivariate and multivariate analyses | Psychosocial working conditions, subclinical depression, reduced psychological wellbeing, high alcohol consumption, little social contact, crises, physical inactivity, great physical strain outside work, inadequate coping strategies | Yes | Increased depression in: Women (bivariate and multivariate analyses): RR: 2.4; 95% CI: [1.0; 5.8] Men (univariate analyses only): RR: 2.2; 95% CI: [1.0, 5.2], multivariate not significant |

| Bohle, 1989 (16) |

60 | Nurses Women: 100% Mean age: 18.9 (17 to 30) years (No information on age, distributed in line with comparison groups) |

Australia | Not stated | 2-shift system (months 1 to 6: day and afternoon shift), then 3-shift system (months 7 to 15; day, afternoon, and night shift) versus 2-shift system (month 15; day and afternoon shift) | GHQ-12 | Measured 3 times (immediately after being hired, i.e. before start of shift work, and after 6 and 15 months) | ANOVA with repeated measurement, multiple regression | Extraversion, neuroticism, chronotype, vitality, rigidity, conflict between work and private life, social support | No | Increased depression after switching to system with night shifts |

| d’Errico, 2011 (19) |

2105 | Members of an Italian labor union Women: 23% Men: 77% Age, years: 15 to 24: 2.1% 25 to 44: 61.6% 45: 36.3% (No information on age or sex, distributed in line with comparison groups) |

Italy | Baseline: 60% Follow-up: 51% |

2-shift system or 3– to 4-shift system or irregular shift work versus daytime work | Indirectly via prescription of antidepressants | Measured twice (baseline: 1999 to 2000; follow-up: 2005) | Poisson regression | Age, sex, occupational group | Yes | Increased depression in subgroup of white-collar workers onlyRR: 2.58; 95% CI: [1.30; 5.11] |

| Driesen, 2011 (20) |

8178 | Employees of 45 different companies and organizations Women: 18/10% Men: 82/90% (daytime work/shift work) Age, years: 42.7 ± 8.7 (daytime work) 37.5 ± 8.6 (shift work) from the Maastricht Cohort Study |

The Netherlands | Baseline: not stated Follow-up: 74.3% (of baseline figure) |

2-, 3-, 4-, or 5-shift system or irregular shift plans (all with night shifts) versus daytime work | Psychiatric interview (screening question concerning depression) HPQ | Measured 3 times (1-, 2– and 10-year follow-up; baseline: 1998; last follow-up: 2008) | ANOVA, chi-square test, hazard ratio, logistic regression, Cox regression, OR, RR | Training, living alone, freedom to make decisions, support by colleagues and superiors, physical, mental, and emotional demands of work | Yes | Increased depression in: Men: HR: 1.22; 95% CI: [1.02; 1.46] Men ≥ 45: HR: 1.37; 95% CI: [1.01; 1.86] (unadjusted) Difference disappears after adjustment for demographic and psychosocial working conditions |

| Flo, 2014* (24) |

1224 | Nurses Women: 90.3% Men: 9.7% Mean age: 33.6 ± 8.3 years List of members of the Norwegian Nurses‘ Organization |

Norway | Wave 1: 38.1% Wave 2: 80.9% |

Daytime work only or night shift only or 2-shift system (day and evening shift) or 3-shift system (day, evening, and night shift) Correlation between no. of breaks between shifts of less than 11 hours (quick returns) when first measured or change in no. between measurement times and mental illness when measured for second time |

HADS | Measured twice (baseline; follow-up at 1 year) | Logistic regression | Age, sex, depression at wave 1, no. of quick returns, no. of night shifts at wave 1, increase or decrease in no. of quick returns between wave 1 and wave 2, increase or decrease in no. of night shifts | No | No correlation between no. of quick returns and anxiety or depression |

| Lin, 2012 (22) |

407 | Nurses Women: 100% Age, years (cohorts working in a 3-shift system only) 20 to 24: 34.2% 25 to 29 : 26.0% 30 to 34 : 16.5% 35 to 39: 8.2% 40 to 45: 1.7% (No information on age, distributed in line with comparison groups) |

Taiwan | Baseline: 14.4% Follow-up: 65.5% (of baseline figure) |

Only nurses working a 3-shift system (day, evening, and night shift) Comparison of: more night shifts versus fewer night shifts versus the same no. of night shifts at follow-up |

GHQ-12 | Measured twice (nurses working shifts only; baseline: July 2005 to October 2005; follow-up: 6 to 10 months later) | Chi-square test, ANOVA, ANCOVA, linear and logistic regression, t-test | No. of night shifts at baseline Age, professional experience, relationship status, no. of children, work in a medical center versus in a hospital |

No | No correlation (specifically: no change in frequency of depression with change in no. of night shifts) |

| Nabe-Nielsen, 2011 (26) |

2148 | Assistants and auxiliaries training in social and health services Women: 96.6/94.9% Men: 4.4/5.1% (daytime work/shift work) Mean age, years: 35.8 ± 10.1 35.9 ± 11.0 |

Denmark | 2004: 90% 2005: 65% 2006: 56% |

Shift work that includes late shifts (17%), night shifts only (4%), and alternating shifts that include night shifts (26%) versus day shifts (53%) | Copsoq Mental Health (depression, questions on anxiety, melancholy, good mood) | Measured 3 times (baseline: 2004; follow-up: 2005 and 2006) | General linear model: difference between groups in mean scores for target outcome (mental health) | Sex, age, education, mental health at baseline, emotional demands and requirement to conceal one‘s feelings, control over working conditions in general, social support by superiors and colleagues, and hours worked per week | No | No correlation overall No difference between shift workers and night shift workers with no control over work schedule planning Lower risk of depression with shift work plus control over work schedule planning |

| Norder, 2015 (23) |

5826 | Industrial manufacturing employees (steel working) Men: 100% Mean age, years: 47.2 ± 7.0 45.3 ± 8.0 (daytime work/shift work) |

The Netherlands | Secondary data (527 of a total of 6678 excluded due to incomplete information, i.e. dataset 92% complete) | Alternating shifts that include night shifts versus daytime work | Time off work due to mental illness (emotional disorders ICD-10 R45 or psychological and behavioral disorders ICD-10 F00 to F99) | All time off work recorded over 10 years, mean follow-up 7.7 years (SD: 3.0 years) (register of workplace medical service) | Cox regression, HR, 95% CI | Age and post held | Yes | No correlation overall No difference between shift workers and daytime workers in new-onset time off work due to mental illness in general Insignificant increase in new-onset time off work due to mood disorders HR: 1.87; 95% CI: [0.73; 4.76] |

| Thun, 2014* (21) |

633 | Nurses List of members of the Norwegian Nurses‘ Organization Women: 100% Mean age: 34.7 ± 9.1 years (No information on age, distributed in line withcomparison groups) |

Norway | Wave 1: 38% Wave 2: 81% Wave 3: 79% |

Shift work with night shift only versus daytime work only or shift work including early and late shifts versus night shift when first measured and no night shift when measured for third time versus no night shift when first measured and night shift when measured for third time | HADS | Measured 3 times (winter 2009, 2010, 2011) | Latent growth curve model, dropout analyses | Age, hardiness, chronotype, lethargy, flexibility | No | No correlation (correlation between switch from night shift to day shift and reduced depression) |

*3Publications based on the same cohort: evaluation includes only the paper by Thun et al. (21), to represent all of them.

ANOVA: Variance analysis; ANCOVA: Covariance analysis; Copsoq: Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire; DSM-III-R: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; GHQ-12: General Health Questionnaire; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HPQ: World Health Organization‘s Health and Work Performance Questionnaire; HR: Hazard ratio; ICD: International Classification of Diseases; CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; RR: Relative risk; SD: Standard deviation

Table 2. Risk of bias.

| Potential cause of bias | Optimal characteristics of an unbiased study | Risk of bias | ||||||||

|

Bara 2009 (18) |

Berthelsen 2015 (25) Flo 2014 (24) Thun 2014 (21) |

Bildt 2002 (17) |

Bohle 1989 (16) |

d‘Errico 2010 (19) |

Driesen 2001 (20) |

Lin 2012 (22) |

Nabe-Nielsen 2011 (26) |

Norder 2015 (23) |

||

| 1. Study participants | Study participants are representative of the study population on which the conclusion is to be drawn. | Low | Medium | Low | Medium | Medium | Low | Medium | Low | Low |

| 2. Loss of study participants | The available study data, i.e. data on the study participants not lost to follow-up, is representative of all the original study participants. | Medium | Medium | Medium | Not stated | High | Medium | Medium | Medium | Low |

| 3. Measurement of cause variable | Shift work was recorded in a valid way, and equally for all participants. | Low | Low | Low | Low | Medium | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| 4. Measurement of target parameter | Depression was recorded in a valid way, and equally for all participants. | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| 5. Adjustment for confounding factors | Major confounding variables were appropriately adjusted for. | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Medium |

| 6. Statistical analysis and reporting of findings | Statistical analysis is appropriate, and all primary target parameters are reported. | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Medium | Low |

Cause 1: Risk was classified as low if the participation rate was at least 80% or nonparticipation was not selective.

Cause 2: Risk was classified as low if the number of participants at short-term (<1 year) follow-up was at least 80% of the number at baseline, or if the number at long-term (= 1 year) follow-up was 70% of the number at baseline, or if there was information to the effect that there were no differences between participants and those lost to follow-up that might lead to selection.

In addition, 5 of the studies for which the necessary information was available (Table 1, extended version in eTable 2) were summarized in a meta-analysis (eBox, eFigure).

eBOX. Meta-analysis.

-

Methods

Meta-analysis included all studies that compared individuals working shifts that included night shifts and those working during the day, a binary target parameter (depression: yes/no), and an adjusted risk estimate (relative risk or odds ratio) (table 1). Where multiple comparisons were described—for example 2, 4, or more shifts per month versus daytime work—the comparison with the highest case number was included (19). Where there were various observation periods, the longest was chosen (18).

Meta-analysis involved random effects modeling (e13). The Q-test and I2 were used to test the heterogeneity of study findings (e14). A funnel plot was used to estimate publication bias, and Begg‘s method was used to determine the extent of asymmetry (e15). All analyses were performed using the statistics program Stat 11 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA) (e16).

-

Findings

The Q-test indicates heterogeneity between the studies selected for meta-analysis (p = 0.001), as does the value of I2 (74.4%). Neither the funnel plot nor Begg‘s method showed any evidence of publication bias (p = 0.230) (efigure).

eFigure.

Relationship between shift work that includes night shifts and risk of depression: points indicate point estimates. Horizontal lines indicate 95% CIs in comparison to the risk entailed in daytime work. The vertical line indicates risk = 1.

CI: Confidence interval; M: Male; F: Female

Results

A total of 11 publications, based on 9 prospective studies, met the inclusion criteria for this review.

Because the studies included in the analysis varied in terms of country, occupational group, case number, length of follow-up, and adjustment for potential confounding factors (Table 1, extended version in eTable 2), their findings also differed.

Five publications find a correlation between shift work and an increase in depressive symptoms or onset of depression during the observation period, at least in some subgroups (16– 20). Three (21– 23) found no evidence of a correlation. Out of 3 publications based on the same cohort of Norwegian nurses, only the publication with the longest follow-up period was included in this analysis, representing all 3 (21). The findings of the other 2 (24, 25) are in line with those of the included publication. Another study reports a correlation between shift work and reduced depressive symptoms in a subgroup of workers who stated that they had more autonomy in their schedule planning (26).

To summarize by investigated population and length of follow-up, studies that investigated nurses or those in related professions for a maximum of 2 years mostly find that there is either no correlation or a favorable association between shift work and depression (21, 22, 26). An exception to this is the oldest study—also the one with the smallest case number—which is quasi-experimental in design and does find evidence of an increase in depressive symptoms (16). In contrast, studies investigating large samples of a more or less unselected population with a follow-up lasting between 4 and 10 years do find evidence of an increased risk of depression in a subgroup of shift workers: in one case, there was a correlation between shift work and risk of depression in women only. In men, the correlation disappeared after adjustment for psychosocial working conditions (17). In another case, the association between shift work and depression is found only for men working night shifts and women working alternating shifts (18), for white-collar but not blue-collar workers (19), or not at all after adjustment for psychosocial working conditions (20). However, a supplementary meta-analysis also indicates an increased risk (risk estimate: 1.42; [0.92, 2.42]) (efigure).

The shift workers and daytime workers included in these studies differed from each other in terms of a number of characteristics, only some of which are shown explicitly: in particular, there are statistically significant differences regarding age (20, 22, 23), sex (20, 26), school and occupational education (23, 27), weekly working hours (23, 26), family situation (22, 26), baseline psychological wellbeing (20, 26), psychosocial working conditions (20, 25, 26), and professional position (23). However, differences in these characteristics that themselves affect mental health and might therefore lead to bias were adjusted for in all the studies (Table 1, extended version in eTable 2).

Several studies investigated the effect of differences in a wide range of psychosocial working conditions on the correlation between shift work and depressive disorders. In 3 studies, the findings regarding the effect of shift work on depression did not change after adjustment for psychosocial working conditions (16, 19, 25). In contrast, in 3 other studies the correlation did change when the following working conditions were adjusted for (17, 20, 26): decision latitude, social support by superiors and colleagues, demands of work, pride in work, and control over working hours.

None of the studies investigated whether selection caused by excluding sensitive or sick employees from shift work may have led to a healthy worker effect resulting in no differences being found between shift workers and daytime workers. Thun et al. (21) did find evidence of selection: depressive mood improved in individuals who switched from night shifts to day shifts during the observation period. Driesen et al. (20) show that depressive mood increases the probability of switching from night shifts to day shifts. In a sensitivity analysis, Norder et al. (23) conclude that their findings do not change when only individuals who did not switch their shift plans during the observation period are included.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, we have put together the first systematic review on the correlation between shift work that includes night shifts and depression, which is the group of mental illnesses that plays a dominant role in the workplace (28). The studies evaluated in this review, all of which are prospective, yield evidence both for and against an increased risk of depression in those who work shifts. These correlations show patterns.

The finding that there is no such association among nurses is essentially based on 2 studies conducted in Norway (21, 24, 25) and Denmark (26). It can be speculated that favorable working conditions in these countries, such as opportunities to determine one‘s own shift plan (26), reduce the damaging effects of shift work. Other psychosocial factors may also play a dominant role among nurses, mask the effects of shift work, and explain why depression is a greater burden in this occupation than in the general population (29). Finally, it is possible that shift work only increases the risk of depression after several years.

In contrast, studies that drew their samples from the general population and thus from a wide variety of occupations did find an increased risk of depressive disorders in some subgroups over a long observation period (more than 4 years) (17– 20). These studies examined workers who differed from each other in terms of country and culture, training and profession, psychosocial working conditions, socioeconomic status, and other characteristics that have a wide range of effects on the risk of depressive disorders. As they nevertheless concurred in finding that shift work affected depression, although in different subgroups and with differing definitions of exposure, it seems more likely that there truly is a correlation. The findings of the supplementary meta-analysis essentially confirm the conclusion of the systematic review: prospective, high-quality studies indicate that in all occupational groups shift work that includes night work can increase the risk of depression. However, this evidence cannot be statistically confirmed at this time. The statistical power of the meta-analysis is limited by the fact that so few studies could be included, and by the great variation between them in terms of case number, length of observation period, occupation, country, and measurement of target parameters.

The lack of a correlation between shift work and depression may be due to sick individuals switching from shift work to daytime work (a healthy worker effect). Exhaustion, need for rest, sleep disorders, poorer overall health, or conflict between work-related and private responsibilities increase the probability of switching to day shifts (30). Workers react to the first symptoms of worsening mental health by switching from shift work (31).

The observation that in 2 of the 4 studies (17, 20) correlations disappeared after adjustment for psychosocial working conditions according to the job demand-control-support model (work stress) suggests that the correlation between shift work and depression is caused at least in part by differences in work-related stress between night and other shifts, and thus only partly by chronobiological strain due to work being misaligned with the body clock. Differences in psychosocial working conditions between shift workers and daytime workers can also be found where there was no correlation with depression (23). That fact that psychosocial working conditions partly determine the risk of depressive disorders has been definitively confirmed (32, 33). That would shift the practical focus of prevention from night shift work or shift planning to psychosocial working conditions that are typically less favorable for night shift work than for daytime work. This includes, for example, reduced social support by superiors (20, 26, 34), less freedom to make decisions and less control over one‘s work (34, 35), increased conflicts at work (35), and more experience of violence (34).

There is little doubt that shift work can have short-term affective consequences, such as worsened mood, which are similar to depressive symptoms. However, there is no evidence that these acute complaints increase the risk of developing a clinical depressive disorder in the longer term (10). In order to provide an at least plausible explanation of how shift work might cause depression, the direct consequences of disruption to the chronobiological rhythm must be considered: reduced sleep time (36, 37, e8), reduced sensitivity of peripheral cortisol receptors and functional hypercortisolism (38, 39), and reduced melatonin production (40).

In addition to the scoping review mentioned above (8), all earlier reviews of which we are aware included mostly cross-sectional studies, with only a few of the 11 truly longitudinal studies evaluated here. Most of these publications did find an association between working night shifts and exhaustion, sleep disorders, and reduced wellbeing (11, 12). Regarding an association between working night shifts and mental illness, particularly depression, Tucker and Knowles conclude that the hypothesis of a correlation is at least supported (10). Vogel et al. rate the evidence provided by studies as lacking solid proof of a correlation (12) but also indicate the role of psychosocial factors (12).

Interpretation of our findings is limited by the fact that although we performed a comprehensive search of the literature we were able to find only a very small number of studies that could be included in the analysis. Because correlations were found only in varying, non-comparable subgroups, the power of the meta-analysis was limited. Similarly, it was not worthwhile to use a scoring system to provide a quantitative evaluation of the evidence (15); moreover, the QUIPS criteria do not recommend this (14). Our findings cannot be extrapolated to other psychiatric illnesses. If the findings were extrapolated to other shift systems that did not include night work, the effects found would probably tend to be weaker.

Summary

Even after decades of research into the impact of shift work on health, it remains unclear whether shift work—in its chronobiologically most marked form, shift work that includes night work—can increase the risk of developing or exacerbating depression. While studies in nurses do not confirm such a correlation, there are multiple findings from high-quality studies conducted in the working population in general that do suggest correlations. However, no definitive conclusion can be drawn because the findings differ concerning specific groups and circumstances in which the risk is increased. It seems that, in addition to the direct effects of disrupted chronobiological rhythm on sleep, hormone regulation, and many other biological functions, psychosocial working conditions with adverse effects on health, which are qualitatively and quantitatively different for shift workers and those who work during the day, play a role in mediating certain effects. There do not seem to be grounds for medical professionals to advise all individuals who are at increased risk of depression or have suffered depression to avoid shift work. Instead, it may be beneficial to adopt a highly personalized approach, closely observing work-related complaints and noting psychosocial working conditions that entail psychological stress. The best way to achieve further advances in knowledge is by conducting large cohort studies in which shift systems, working conditions, individual characteristics, and illness are differentiated and documented using a valid procedure.

Key Messages.

Longitudinal studies across all sections of the working population yield evidence of an increased risk of depressive disorders after many years‘ shift work that includes night shifts. However, this conclusion remains weak because findings are heterogeneous.

Stressful psychosocial working conditions (occupational stress), which differ qualitatively and quantitatively between shift work and daytime work, seem to explain part of the risk associated with shift work.

The studies evaluated in this review do not justify advising all individuals with depressive illnesses to avoid nighttime work.

Employees with depressive illnesses should be closely monitored by physicians if they work night shifts. In particular, the psychosocial stress involved in this type of work should be considered.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Prof. Dr. Bernd Richter of the Cochrane Metabolic and Endocrine Disorders Group at the Institute of General Practice and Family Medicine (Institut für Allgemeinmedizin), Centre for Health and Society at the University of Düsseldorf, for his critical examination of the manuscript of this article.

Translated from the original German by Caroline Shimakawa-Devitt, M.A.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Destatis Microzensus 2013. Wiesbaden Statistisches Bundesamt: 2014. Bevölkerung und Erwerbstätigkeit: Beruf, Ausbildung und Arbeitsbedingungen der Erwerbstätigen in Deutschland. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vyas MV, Garg AX, Iansavichus AV, et al. Shift work and vascular events: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012;345 doi: 10.1136/bmj.e4800. e4800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gan Y, Yang C, Tong X, et al. Shift work and diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Occup Environ Med. 2015;72:72–78. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2014-102150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang F, Zhang L, Zhang Y, et al. Meta-analysis on night shift work and risk of metabolic syndrome. Obes Rev. 2014;15:709–720. doi: 10.1111/obr.12194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Straif K, Baan R, Grosse Y, et al. Carcinogenicity of shift-work, painting, and fire-fighting. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:1065–1066. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70373-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang F, Yeung KL, Chan WC, et al. A meta-analysis on dose-response relationship between night shift work and the risk of breast cancer. ESMO. 2013;24:2724–2732. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin X, Chen W, Wei F, Ying M, Wei W, Xie X. Night-shift work increases morbidity of breast cancer and all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis of 16 prospective cohort studies. Sleep Med Res. 2015;16:1381–1387. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2015.02.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amlinger-Chatterjee M. Bundesanstalt für Arbeitsschutz und Arbeitsmedizin. Dortmund: 2016. Psychische Gesundheit in der Arbeitswelt Atypische Arbeitszeiten. 1. Auflage. [Google Scholar]

- 9.McClung CA. How might circadian rhythms control mood? Let me count the ways. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;74:242–249. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tucker P, Knowles SR. Review of studies that have used the Standard Shiftwork Index: evidence for the underlying model of shiftwork and health. Appl Ergon. 2008;39:550–564. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Cordova PB, Phibbs CS, Bartel AP, Stone PW. Twenty-four/seven: a mixed-method systematic review of the off-shift literature. J Adv Nurs. 2012;68:1454–1468. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.05976.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vogel M, Braungardt T, Meyer W, Schneider W. J Neural Transm. Vol. 119. (Vienna): 2012. The effects of shift work on physical and mental health; pp. 1121–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayden JA, Cote P, Bombardier C. Evaluation of the quality of prognosis studies in systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:427–437. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-6-200603210-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayden JA, van der Windt DA, Cartwright JL, Cote P, Bombardier C. Assessing bias in studies of prognostic factors. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:280–286. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-4-201302190-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Proper KI, van de Langenberg D, Rodenburg W, et al. The relationship between shift work and metabolic risk factors: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50:e147–e157. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bohle P, Tilley AJ. The impact of night work on psychological well-being. Ergonomics. 1989;32:1089–1099. doi: 10.1080/00140138908966876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bildt C, Michelsen H. Gender differences in the effects from working conditions on mental health: a 4-year follow-up. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2002;75:252–258. doi: 10.1007/s00420-001-0299-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bara AC, Arber S. Working shifts and mental health—findings from the British Household Panel Survey (1995-2005) Scand J Work Environ Health. 2009;35:361–367. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.d‘Errico A, Cardano M, Landriscina T, et al. Workplace stress and prescription of antidepressant medications: a prospective study on a sample of Italian workers. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2011;84:413–424. doi: 10.1007/s00420-010-0586-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Driesen K, Jansen NW, van Amelsvoort LG, Kant I. The mutual relationship between shift work and depressive complaints—a prospective cohort study. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2011;37:402–410. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thun E, Bjorvatn B, Torsheim T, Moen BE, Mageroy N, Pallesen S. Night work and symptoms of anxiety and depression among nurses: a longitudinal study. Work & Stress. 2014;28:376–386. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin PC, Chen CH, Pan SM, et al. Atypical work schedules are associated with poor sleep quality and mental health in Taiwan female nurses. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2012;85:877–884. doi: 10.1007/s00420-011-0730-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Norder G, Roelen CA, Bultmann U, van der Klink JJ. Shift work and mental health sickness absence: a 10-year observational cohort study among male production workers. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2015;41:413–416. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Flo E, Pallesen S, Moen BE, Waage S, Bjorvatn B. Short rest periods between work shifts predict sleep and health problems in nurses at 1-year follow-up. Occup Environ Med. 2014;71:555–561. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2013-102007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berthelsen M, Pallesen S, Mageroy N, et al. Effects of psychological and social factors in shiftwork on symptoms of anxiety and depression in nurses: a 1-year follow-up. J Occup Env Med. 2015;57:1127–1137. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nabe-Nielsen K, Garde AH, Albertsen K, Diderichsen F. The moderating effect of work-time influence on the effect of shift work: a prospective cohort study. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2011;84:551–559. doi: 10.1007/s00420-010-0592-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ozdemir PG, Selvi Y, Ozkol H, et al. The influence of shift work on cognitive functions and oxidative stress. Psychiatry Res. 2013;210:1219–1225. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Joyce S, Modini M, Christensen H, et al. Workplace interventions for common mental disorders: a systematic meta-review. Psychol Med. 2016;46:683–697. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715002408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wieclaw J, Agerbo E, Mortensen PB, Bonde JP. Risk of affective and stress related disorders among employees in human service professions. J Occup Env Med. 2006;63:314–319. doi: 10.1136/oem.2004.019398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Amelsvoort LG, Jansen NW, Swaen GM, van den Brandt PA, Kant I. Direction of shift rotation among three-shift workers in relation to psychological health and work-family conflict. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2004;30:149–156. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Raeve L, Kant I, Jansen NW, Vasse RM, van den Brandt PA. Changes in mental health as a predictor of changes in working time arrangements and occupational mobility: results from a prospective cohort study. J Psychosom Res. 2009;66:137–145. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stansfeld S, Candy B. Psychosocial work environment and mental health—a meta-analytic review. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2006;32:443–462. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Theorell T, Hammarstrom A, Aronsson G, et al. A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and depressive symptoms. BMC Public Health. 2015;15 doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1954-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nabe-Nielsen K, Tuchsen F, Christensen KB, Garde AH, Diderichsen F. Differences between day and nonday workers in exposure to physical and psychosocial work factors in the Danish eldercare sector. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2009;35:48–55. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boggild H, Burr H, Tuchsen F, Jeppesen HJ. Work environment of Danish shift and day workers. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2001;27:97–105. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harma M. Workhours in relation to work stress, recovery and health. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2006;32:502–514. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sallinen M, Kecklund G. Shift work, sleep, and sleepiness—differences between shift schedules and systems. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2010;36:121–133. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.2900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kino T, Chrousos GP. Acetylation-mediated epigenetic regulation of glucocorticoid receptor activity: circadian rhythm-associated alterations of glucocorticoid actions in target tissues. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;336:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pariante CM. Risk factors for development of depression and psychosis Glucocorticoid receptors and pituitary implications for treatment with antidepressant and glucocorticoids. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1179:144–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04978.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rahman SA, Marcu S, Kayumov L, Shapiro CM. Altered sleep architecture and higher incidence of subsyndromal depression in low endogenous melatonin secretors. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010;260:327–335. doi: 10.1007/s00406-009-0080-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E1.Roenneberg T, Kantermann T, Juda M, Vetter C, Allebrandt KV. Light and the human circadian clock Handbook of experimental pharmacology. In: Pertwee R, editor. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York Springer-Verlag: 2013. pp. 311–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E2.Boivin DB, Boudreau P. Impacts of shift work on sleep and circadian rhythms. Pathol Biol. 2014;62:292–301. doi: 10.1016/j.patbio.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E3.Richardson GS. The human circadian system in normal and disordered sleep. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:3–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E4.Knauth P. Schichtarbeit Handbuch der Arbeitsmedizin. In: Letzel S, Nowak D, editors. Ecomed. München: 2007. B IV-2. [Google Scholar]

- E5.Tucker P, Brown M, Dahlgren A, et al. The impact of junior doctors‘ worktime arrangements on their fatigue and well-being. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2010;36:458–465. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.2985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E6.Hill SM, Belancio VP, Dauchy RT, et al. Melatonin: an inhibitor of breast cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2015;22:R183–R204. doi: 10.1530/ERC-15-0030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E7.Nijm J, Jonasson L. Inflammation and cortisol response in coronary artery disease. Ann Med. 2009;41:224–233. doi: 10.1080/07853890802508934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E8.Pilcher JJ, Lambert BJ, Huffcutt AI. Differential effects of permanent and rotating shifts on self-report sleep length: a meta-analytic review. Sleep. 2000;23:155–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E9.Wolk R, Gami AS, Garcia-Touchard A, Somers VK. Sleep and cardiovascular disease. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2005;30:625–662. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E10.Peter R, Alfredsson L, Knutsson A, Siegrist J, Westerholm P. Does a stressful psychosocial work environment mediate the effects of shift work on cardiovascular risk factors? Scand J Work Environ Health. 1999;25:376–381. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E11.Ramin C, Devore EE, Wang W, Pierre-Paul J, Wegrzyn LR, Schernhammer ES. Night shift work at specific age ranges and chronic disease risk factors. Occup Environ Med. 2015;72:100–107. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2014-102292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E12.Nea FM, Kearney J, Livingstone MB, Pourshahidi LK, Corish CA. Dietary and lifestyle habits and the associated health risks in shift workers. Nutr Res Rev. 2015;28:143–166. doi: 10.1017/S095442241500013X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E13.Hedges LV, Vevea JL. Fixed- and random-effects models in meta-analysis. Psychol Methods. 1998;3:486–504. [Google Scholar]

- E14.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E15.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E16.Sterne J. Meta-analysis in STATA: an updated collection from the Stata Journal. USA: Stata Press. 2009:1–259. [Google Scholar]