ABSTRACT

Ovarian metastasis is an exceptionally rare condition in lung adenocarcinoma patients and is often difficult to distinguish from primary ovarian carcinoma. ALK (anaplastic lymphoma kinase) tyrosine kinase inhibitors elicit a significant objective response rate and are well-tolerated in advanced ALK-positive lung cancer. Hence, we report a case of a 41-year-old woman with ovarian metastases from NSCLC. After receiving a 6 course first line chemotherapy and 8 course maintenance therapy, the patient suffered acute abdominal pain, so surgery was performed. ALK rearrangement was detected by next generation sequencing, with a 13% abundance of ALK fusion. Crizotinib was administered, and the disease remained stable after 10 months of crizotinib therapy. Further, we reviewed the literature related to characteristics of metastatic ovarian malignancies that form from lung tumors, the utility of ALK inhibition for treating ALK-positive NSCLC, the molecular diagnosis of ALK rearrangement and the role of next generation sequencing for ALK rearrangement detection.

KEYWORDS: Lung adenocarcinoma, ALK, ovarian metastasis, next generation sequencing

Introduction

Lung cancer is the most common malignant tumor and the leading cause of human cancer deaths worldwide. Non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for 80–85% of all lung cancers.1 The common metastatic sites of NSCLC includes brain, bone, liver and adrenal glands.2 Ovarian metastasis from lung cancer is extremely rare, accounting for only 0.3%−0.4% of metastatic ovarian tumors.3 Pelvic CT examination is not routinely performed in clinical practice for advanced NSCLC, so ovary metastasis may easily go unnoticed. Because treatment modalities, such as radical surgery or palliative chemotherapy, differ between primary and metastatic ovarian tumors, differential diagnosis is crucial.

The EML4-ALK (echinoderm microtubule associated protein-like 4-anaplastic lymphoma kinase) fusion gene has been identified as an important oncogenic driver in NSCLC, representing 3%∼7% of adenocarcinoma.4 It is encountered more frequently in patients with an adenocarcinoma subtype histology, younger age, and light or nonexistent smoking history. ALK activity can be efficiently targeted by ALK inhibitors, such as crizotinib.5 ALK tyrosine kinase inhibitors yield a spectacular objective response rate, and consequently, crizotinib is preferred as the initial therapy for advanced ALK-positive lung cancer.6

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) allows for the rapid generation of thousands to millions of DNA sequences of an individual patient. The rapid emergence and the great successes of this technology have contributed to a new era in genetic diagnostics. Therefore, NGS has already been applied in the clinic for cancer diagnosis and prognosis.7 NCCN panels recommend that NGS be used to detect panels of mutations and gene rearrangements of the ALK gene. Hence, we now describe a case of ovarian metastasis from NSCLC with ALK rearrangement detected by NGS.

Case report

A 41-year-old woman with no prior smoking history presented with cough and dyspnea. Computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest with contrast revealed a 3.0*2.1 cm sized left lower lobe mass with left hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathies, as well as pleural metastasis and pleural effusion (Fig. 1). Both brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and bone scintigraphy showed no positive signs. In addition, positive expression was also not found in abdominal and pelvic CT scans. Thus, the clinical stage of this patients was T1N2M1 (stage IV). Because of the dyspnea syndrome, a thorax puncture and drainage were performed, and the effusion samples were sent for laboratory analysis following surgery. Cytological examination revealed adenocarcinoma cells (Fig. 2). The staining for TTF-1 (thyroid transcription factor-1) and Napsin A (novel aspartic proteinase A) was positive, while the staining for p40 was negative. However, the amplification refractory mutation system (ARMS) to assess the mutation status of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) was negative. An anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) test was not used due to inadequate sample.

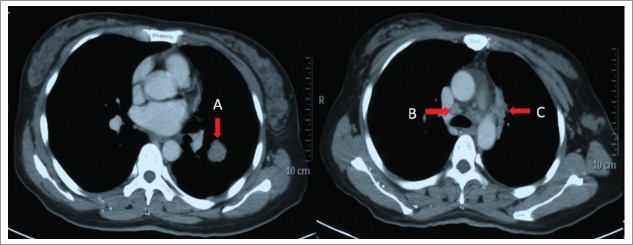

Figure 1.

Shows the initial assessment before treatment by means of computed tomography (CT) scan of chest with contrast. The arrows are that: (A) left lower lobe masses (B) mediastinal lymphadenopathies (C) pleural metastasis.

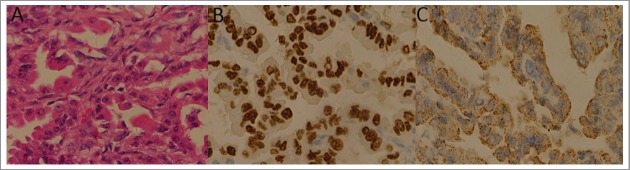

Figure 2.

The cytological examination revealed adenocarcinoma cells. Wright-Giemsa Stain (10 × 40) is used in both left and right panel.

Therefore, the patient received combination chemotherapy with bevacizumab, pemetrexed and cisplatin as the first line treatment. Pleural drainage and intrapleural perfusion were administered to relieve symptoms of dyspnea. Response evaluation was performed after every 2 cycles of chemotherapy per the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors criteria. The responses of the primary tumor after 2 courses, 4 courses, and 6 courses were partial response (PR), complete response (CR), and CR, respectively (Fig. 3A, 3B, 3C). Because of the ideal response to chemotherapy, 5 courses of maintenance chemotherapy with bevacizumab and pemetrexed were given. Subsequently, pemetrexed alone was used for another 3 courses of maintenance treatment due to financial reasons. During maintenance, response evaluations after every 2 cycles indicated stable disease (SD) (Fig. 3D).

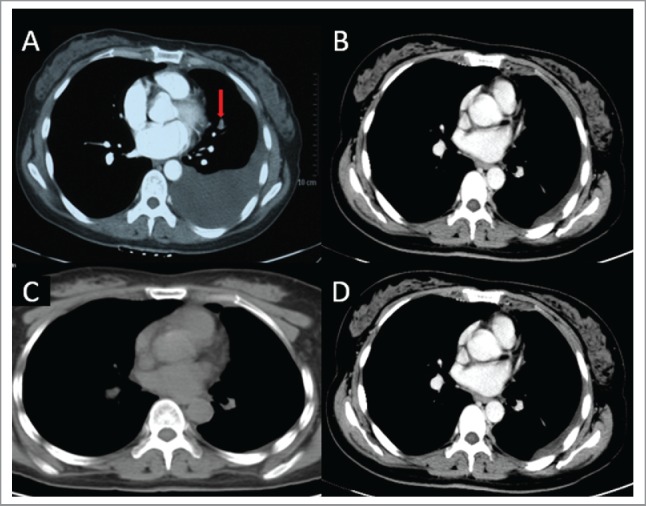

Figure 3.

Shows the response at the different evaluation time. The panels mean that: (A) The response evaluation of primary tumor after 2 courses chemotherapy is partial response (PR). The arrow in panel A shows the residual mass after 2 courses first-line chemotherapy. (B) The response of primary tumor after 4 courses chemotherapy is complete response (CR). (C) The response of primary tumor after 6 courses chemotherapy is CR. (D) Response before the last maintenance therapy was evaluated and stable disease persists.

Two months after the last maintenance therapy, this patient suffered acute abdominal pain after physical activity. A CT scan showed an ovarian mass (Fig. 4A). Therefore, emergency surgery was performed considering ovarian tumor pedicle torsion. The resected tissues were sent for pathological evaluation and immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis. The pathological diagnosis of the specimens was metastatic pulmonary adenocarcinoma (Fig. 5A). The results for IHC staining were TTF-1 + and Napsin A + (Fig. 5B, 5C). Next generation sequencing on blood and resected specimens of ovary revealed EGFR - and ALK +, and the abundance of ALK fusion was 13%. The NGS platform used in this patient was Illumina HiSeqX10, coving 416 gene exons (1,463,540 bases). In this sequence, EMLA4-ALK translocation was identified, while other rare translocation partners that form fusion proteins were not detected. Both ALK overexpression and activating ALK point mutations (such as 1151T, L1152R, and C1156Y) were detected. Unfortunately, these results were all negative.

Figure 4.

The panels means that: (A) CT scan showed left ovarian metastasis. The red arrow in panel A shows the ovarian metastatic mass, which diameter is about 10 cm. (B and C) There is no evidence of progression on regular follow-up examination.

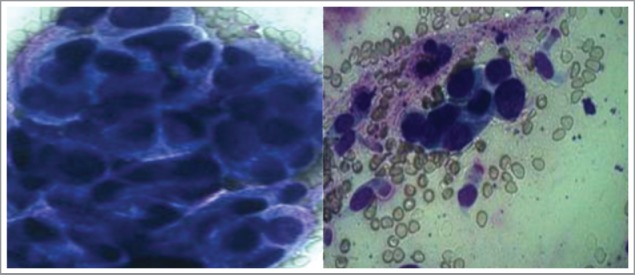

Figure 5.

The panels means that: (A) The pathological diagnosis of the specimens was metastatic pulmonary adenocarcinoma. (H-E staining 10 × 40) (B) TTF-1 is positive in IHC staining. (C) Napsin A is positive in IHC staining.

Accordingly, crizotinib was administered to this patient. The patient showed no evidence of progression upon regular follow-up examinations (Fig. 4B, 4C). The disease remained stable for 10 months after crizotinib administration. The patient consented to the publication of this case report.

Discussion

In this case, the patient suffered acute abdominal pain at the time of follow-up after maintenance therapy, and CT scan confirmed an ovarian mass, so this patient received emergency surgery. This case underscores that pelvic evaluation is useful for seeking out potential problems in advance, in case emergency situations, such as ovarian tumor pedicle torsion, necrosis, and acute pain, occur. Meanwhile, sufficient resected tissue could be submitted for pathological and immunohistochemistry diagnoses to confirm primary or metastatic lesion. Although routine surveillance CT scans for asymptomatic female patients with stage IV NSCLC are not required, clinicians should be cautious regarding the probability of ovarian metastasis and pay close attention to discomfort, such as abdominal pain, fever, and menstrual changes. Once symptoms arise, the corresponding appropriate examination is necessary. Alternatively, given its safety and convenience, regular ultrasonography (once per 3 months or longer) may be more likely to detect ovarian metastases in advance. Thus, pelvic exams is an appropriate choice for female patients with advanced lung adenocarcinoma when follow-up examination is performed.

Lung cancer is a heterogeneous tumor. Intra-tumor heterogeneity has been described and poses a significant challenge to personalized cancer treatment. For example, many studies have reported the discrepancy of EGFR mutation status between the primary tumor and metastatic lesions from the same patient.8 Unlike EGFR mutation, a high concordant rate of ALK rearrangement was observed between primary tumors and paired metastatic lymph nodes. The concordance rate between primary tumors and paired metastatic lymph nodes was 98%, and ALK rearrangement exhibited a 100% concordance between different metastatic lymph nodes in the same patient.9 Therefore, we conclude that specimens from metastatic lesions and primary tumors are equally suitable for use in detecting ALK rearrangement for therapeutic strategies in patients with advanced NSCLC. In our case, the ALK rearrangement was not detected in the primary tumor, and a positive indication for rearrangement was found in a metastatic ovarian lesion. Accordingly, crizotinib was administered due to the high concordance between primary and metastatic lesions for ALK rearrangement.

Lung cancer is a major cause of cancer-related deaths due to the biologically aggressive features. Lung cancer can be divided mainly into 2 subsets: non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and small-cell lung cancer (SCLC), accounting for approximately 85% and 15% of all lung cancer cases, respectively. Furthermore, NSCLC can be divided into 3 main histologic subtypes: squamous-cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, and large-cell lung cancer, of which adenocarcinoma is the most common type. Despite advancements in early detection and standard treatment strategies, most patients with NSCLC present with advanced stage disease, and the majority of advanced NSCLC patients will inevitably progress after first-line or maintenance treatment.10

Lung cancers can spread widely to distant organs via lymphatic circulation and blood vessels. The most commonly involved organs are the brain (45%), liver (45%), adrenals (34%), kidneys (24%), bones (20%), heart and pericardium (20%).11 Metastatic ovarian malignancies are not uncommon; these make up 10%−30% of all ovarian cancers. However, the ovary is an unusual location for metastasis stemming from lung cancer, which accounts for only 0.3%−0.4% of metastatic ovarian tumors.3 Differential diagnosis between primary and metastatic ovarian neoplasms is crucially warranted because the treatment regimen and prognosis are markedly different for each.

Irving et al. shared the common features of metastatic ovarian tumors from lung carcinoma.3 Patient with lung carcinoma metastatic to the ovary were typically younger, with a mean age of 47 y (range, 26–76 years). Ovarian tumors were detected at a mean interval of one year from the time of initial diagnosis of lung carcinoma. The most common histologic subtype of lung adenocarcinoma was acinar, usually with moderate to poor differentiation. The mean size of ovarian metastatic tumors was 9.7 cm, and one third of the ovarian metastases were bilateral. Morphologic features are also noted: multinodular growth, widespread necrosis, and extensive lymphovascular invasion. The involvement of the ovarian surface was rare, revealing that the mode of spread in these cases is hematogenous or lymphangitic, instead of peritoneal seeding. In a minority of these cases, immunohistochemical staining for TTF-1 and Napsin A was positive, which is a useful ancillary marker in the distinction from primary ovarian carcinoma. Furthermore, CK-7 and CK-20 staining has been widely used to differentiate between primary and secondary ovarian malignancies.12 In summary, attention to clinical history and histologic recognition that the tumor shows a morphology more typical of a primary lung carcinoma should enable the correct diagnosis in the majority of patients. The features of metastatic ovarian metastases mentioned above and immunohistochemical staining are useful in distinguishing primary and metastatic ovarian tumors.

Interestingly, we retrospectively observed that patients with ovarian metastasis are more likely to be positive for ALK rearrangement and negative for EGFR mutation and the metastatic locations are always in/close to the middle of the body.13-19 (Table 1) Thus, more attention should be paid to ALK translocation status in NSCLC patients with ovarian metastasis, especially for the subset group of patents with an absence of EGFR mutations. Further research is thus necessary to clarify the correlation between ALK rearrangement and metastatic behavior, in particular, metastasis to the ovary. This case also suggests that when performing follow-up examinations for female NSCLC patients with ALK-positive rearrangement, doctors should be conscious of the possibility of such metastases. Of note, Robert has discovered that oncogene status can predict patterns of metastatic spread in non-small cell lung cancer. Robert noted that ALK gene rearrangement was significantly associated with pleural disease (OR = 4.80, 95% CI 2.10, 10.97, p<0.001).20 When pleural effusion or pleural involvement is present in patients, the ALK rearrangement test is critical to help doctors choose the optimal treatment strategy.

Table 1.

Patients with metastasis in non-small cell lung cancer who harboring ALK rearrangement.

| Case no. | Authtor | Age | Sex | Smoking history | Histologic finding | EGFR status | ALK status | Metastatic site |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Wang et al.[11] | 33 | F | Never | Adenocacinoma | − | + | Left Ovarian |

| 2 | Lee et al.[12] | 54 | F | 2.5 pack-year | Adenocacinoma | − | + | Bilateral Ovarian |

| 3 | Fujiwara et al.[13] | 39 | F | 1 pack per-day | Adenocacinoma | − | + | Bilateral Ovarian |

| 4 | West et al.[14] | 50 | F | Not given | Adenocacinoma | − | + | Bilateral Ovarian |

| 5 | Choi et al.[15] | 35 | F | Never | Adenocacinoma | − | + | Uterine Cervix |

| 6 | Diem et al.[16] | 62 | F | Never | Adenocacinoma | − | + | Gastric |

| 7 | Qiao et al.[17] | 48 | F | Never | Adenocacinoma | − | + | Left Ovarian |

ALK translocation has been identified as a targetable oncogenic driver. ALK-rearranged NSCLCs have demonstrated exquisite sensitivity to therapy with the ALK kinase inhibitor crizotinib. Crizotinib is the first-in class ALK tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Its efficacy was demonstrated in a phase I study and subsequently confirmed in a phase II study for NSCLC patients who have an ALK rearrangement.21,22 Two pivotal phase III trials in previously treated6 and in newly diagnosed patients23 have confirmed the superiority and better tolerability of crizotinib compared with standard chemotherapy. These studies validate ALK as a therapeutic target and the current standard of care for patients with advanced ALK-positive NSCLC. A molecular diagnostic test is recommended for detecting ALK rearrangements and is a prerequisite before treatment with crizotinib for all advanced lung adenocarcinomas. Detection of ALK rearrangements is important for selecting the appropriate therapy, especially in light of the prominent response to crizotinib in particular.24 The fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) assay with a dual-labeled break-apart probe set is the current gold standard for ALK rearrangement testing. Many studies have demonstrated the utility of immunohistochemistry (IHC) in detecting ALK rearrangements in clinical samples, and IHC may prove useful as a cost-effective screening tool.25 However, limitations for FISH and IHC exist, such as false-negative results, atypical signal profiles, borderline rates of rearrangement-positive cells, and a lack of an internal positive control for immunostaining.26

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) refers to a variety of different platforms that allow for parallel sequencing of multiple analytes simultaneously and also allow for comprehensive genome-wide analysis at low cost.7 The use of NGS for detecting gene copy number alterations and rearrangements is feasible, and this broad discovery approach already has been used to identify several novel ALK rearrangements and other relevant fusion genes in NSCLC.27,28 The major advantage of using an NGS approach is that a well-designed panel may provide information on a significant number of known gene mutations, gene rearrangements, and copy number alterations across multiple different cancers within a single multiplexed assay, minimizing the decision-making required for clinicians or pathologists when considering which test to order for each patient.7,28 As the amount of tissue required and the cost of NGS decrease and clinical laboratories and regulatory bodies increasingly validate these platforms, the convenience and cost-effectiveness of screening for multiple different abnormalities in populations at the same time are likely to drive the wider adoption of this approach.29 The choice of NGS over traditional technologies both for research purposes and clinical diagnostics is justified due to its obvious advantages, and the value of NGS for routine diagnostics is bound to grow in the future.30

Conclusions

Ovarian metastasis originating from lung adenocarcinoma is extraordinarily scarce. Distinguishing both primary and metastatic ovarian malignancies and confirming the molecular subtype of advanced NSCLCs are very important. The utility of crizotinib offers an excellent therapeutic alternative for patients with ALK-positive NSCLC. Optimizing the appropriate use of crizotinib relies on the assay used to detect ALK positivity. With high-throughput and low cost, next generation sequencing may be useful for the detection of ALK rearrangement status in NSCLC patients to choose optimal treatment modalities.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Funding

This work is supported by the national natural science foundation of china (81472810), science and technology development plans of Shandong province (2014GSF118138).

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016; 66(1):7-30; PMID: 26742998; https://doi.org/ 10.3322/caac.21332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hess KR, Varadhachary GR, Taylor SH, Wei W, Raber MN, Lenzi R, Abbruzzese JL. Metastatic patterns in adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 2006; 106(7):1624-33; PMID: 16518827; https://doi.org/ 10.1002/cncr.21778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Irving JA, Young RH. Lung carcinoma metastatic to the ovary: a clinicopathologic study of 32 cases emphasizing their morphologic spectrum and problems in differential diagnosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005; 29(8):997-1006; PMID: 16006793 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kwak EL, Bang Y-J, Camidge DR, Shaw AT, Solomon B, Maki RG, Ou SH, Dezube BJ, Jänne PA, Costa DB, et al.. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibition in non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010; 363(18):1693-703; PMID:20979469; https://doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMoa1006448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaw AT, Yeap BY, Mino-Kenudson M, Digumarthy SR, Costa DB, Heist RS, Solomon B, Stubbs H, Admane S, McDermott U, et al.. Clinical features and outcome of patients with non–small-cell lung cancer who harbor EML4-ALK. J Clin Oncol. 2009; 27(26):4247-53; PMID:19667264; https://doi.org/ 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.6993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shaw AT, Kim D-W, Nakagawa K, Seto T, Crinó L, Ahn MJ, De Pas T, Besse B, Solomon BJ, Blackhall F, et al.. Crizotinib versus chemotherapy in advanced ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013; 368(25):2385-94; PMID:23724913; https://doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMoa1214886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goodwin S, McPherson JD, McCombie WR. Coming of age: Ten years of next-generation sequencing technologies. Nat Rev Genet. 2016; 17(6):333-51; PMID: 27184599; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nrg.2016.49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gow C-H, Chang Y-L, Hsu Y-C, Tsai MF, Wu CT, Yu CJ, Yang CH, Lee YC, Yang PC, Shih JY. Comparison of epidermal growth factor receptor mutations between primary and corresponding metastatic tumors in tyrosine kinase inhibitor-naive non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol; 2009 Apr; 20(4):696-702; PMID:19088172; https://doi.org/ 10.1093/annonc/mdn679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hou L, Ren S, Su B, Zhang L, Wu W, Zhang W, Dong Z, Huang Y, Wu C, Chen G. High concordance of ALK rearrangement between primary tumor and paired metastatic lymph node in patients with lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Dis. 2016; 8(6):1103; PMID: 27293826; https://doi.org/ 10.21037/jtd.2016.03.96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lung Cancer N Engl J Med. 2009; 360(1):87-8; PMID:19118313; https://doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMc082208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kini SR. Lung cancer Metastatic to other body sites Color Atlas of Pulmonary Cytopathology: Springer; 2002:141-4. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yeh K-Y, Chang JW-C, Hsueh S, Chang T-C, Lin M-C. Ovarian metastasis originating from bronchioloalveolar carcinoma: a rare presentation of lung cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2003; 33(8):404-7; PMID: 14523061; https://doi.org/ 10.1093/jjco/hyg078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang W, Wu W, Zhang Y. Response to crizotinib in a lung adenocarcinoma patient harboring EML4-ALK translocation with adnexal metastasis: A Case Report. Medicine. 2016; 95(30):e4221; PMID: 27472693; https://doi.org/ 10.1097/MD.0000000000004221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee KA, Lee JS, Min JK, Kim HJ, Kim WS, Lee KY. Bilateral ovarian metastases from ALK rearranged non-small cell lung cancer. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul). 2014; 77(6):258-61; PMID: 25580142; https://doi.org/ 10.4046/trd.2014.77.6.258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujiwara A, Higashiyama M, Kanou T, Tokunaga T, Okami J, Kodama K, Nishino K, Tomita Y, Okamoto I. Bilateral ovarian metastasis of non-small cell lung cancer with ALK rearrangement. Lung Cancer. 2014; 83(2):302-4; PMID: 24360322; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.lungcan.2013.11.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.West AH, Yamada SD, MacMahon H, Acharya SS, Ali SM, He J, Lukas RV, Miller VA, Salgia R. Unique metastases of ALK mutated lung cancer activated to the adnexa of the uterus. Case Rep Clin Pathol. 2014; 1(2):151; PMID: 25541622; https://doi.org/ 10.5430/crcp.v1n2p151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi S, Park CK, Kim SY, Yoon HK, Ro SM, Nam Y. Uterine cervix metastasis in lung adenocarcinoma with Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase rearrangement. Soonchunhyang Medical Science (SMS). 2015; 21(2):142-5; https://doi.org/ 10.15746/sms.15.033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diem S, Früh M, Rodriguez R, Liechti P, Rothermundt C. EML4-ALK-Positive pulmonary adenocarcinoma with an unusual metastatic pattern: A case report. Case Rep Oncol. 2013; 6(2):316-9; PMID: 23898275; https://doi.org/ 10.1159/000352086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qiao Y, Ma J-f, Zhang P, Li L. Ovarian metastasis from ALK-positive lung adenocarcinoma: One case report. TUMOR. 2015; 35(7):806-9; https://doi.org/10.3781/j.issn.1000-7431.2015.44.340 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doebele RC, Lu X, Sumey C, Maxson DA, Weickhardt AJ, Oton AB, Bunn PA, Barón AE, Franklin WA, Aisner DL, et al.. Oncogene status predicts patterns of metastatic spread in treatment‐naive nonsmall cell lung cancer. Cancer. 2012; 118(18):4502-11; PMID: 22282022; https://doi.org/ 10.1002/cncr.27409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Camidge DR, Bang Y-J, Kwak EL, Iafrate AJ, Varella-Garcia M, Fox SB, Riely GJ, Solomon B, Ou SH, Kim DW, et al.. Activity and safety of crizotinib in patients with ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer: updated results from a phase 1 study. Lancet Oncol. 2012; 13(10):1011-19; PMID: 22954507; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70344-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim D, Ahn M, Yang P, et al.. Updated results of a global phase II study with crizotinib in advanced ALK-positive non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Ann. Oncol. 2012; (23):402-402. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Solomon BJ, Mok T, Kim D-W, Wu YL, Nakagawa K, Mekhail T, Felip E, Cappuzzo F, Paolini J, Usari T, et al.. First-line crizotinib versus chemotherapy in ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014; 371(23):2167-77; PMID:25470694; https://doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMoa1408440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shaw AT, Engelman JA. ALK in lung cancer: past, present, and future. J Clin Oncol. 2013; 31(8):1105-11; PMID: 23401436; https://doi.org/ 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.5353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lindeman NI, Cagle PT, Beasley MB, Chitale DA, Dacic S, Giaccone G, Jenkins RB, Kwiatkowski DJ, Saldivar JS, Squire J, et al.. Molecular testing guideline for selection of lung cancer patients for EGFR and ALK tyrosine kinase inhibitors: guideline from the College of American Pathologists, International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, and Association for Molecular Pathology. J Thorac Oncol. 2013; 8(7):823-59; PMID:2355237; https://doi.org/ 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318290868f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsao M, Hirsch F, Yatabe Y. IASLC atlas of ALK testing in lung cancer. Aurora, CO: IASLC Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ross JS, Lipson D, Sheehan CE, et al.. Use of next-generation sequencing (NGS) to detect a novel ALK fusion and a high frequency of other actionable alterations in colorectal cancer (CRC). Paper presented at: ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weickhardt AJ, Aisner DL, Franklin WA, Varella‐Garcia M, Doebele RC, Camidge DR. Diagnostic assays for identification of anaplastic lymphoma kinase‐positive non–small cell lung cancer. Cancer. 2013; 119(8):1467-77; PMID: 23280244; https://doi.org/ 10.1002/cncr.27913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Atherly A, Camidge D. The cost-effectiveness of screening lung cancer patients for targeted drug sensitivity markers. Br J Cancer. 2012; 106(6):1100-06; PMID: 22374459; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/bjc.2012.60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luthra R, Chen H, Roy-Chowdhuri S, Singh RR. Next-generation sequencing in clinical molecular diagnostics of cancer: advantages and challenges. Cancers. 2015; 7(4):2023-36; PMID: 26473927; https://doi.org/ 10.3390/cancers7040874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]