Abstract

A sporulation-specific gene, spsM, is disrupted by an active prophage, SPβ, in the genome of Bacillus subtilis. SPβ excision is required for two critical steps: the onset of the phage lytic cycle and the reconstitution of the spsM-coding frame during sporulation. Our in vitro study demonstrated that SprA, a serine-type integrase, catalyzed integration and excision reactions between attP of SPβ and attB within spsM, while SprB, a recombination directionality factor, was necessary only for the excision between attL and attR in the SPβ lysogenic chromosome. DNA recombination occurred at the center of the short inverted repeat motif in the unique conserved 16 bp sequence among the att sites (5΄-ACAGATAA/AGCTGTAT-3΄; slash, breakpoint; underlines, inverted repeat), where SprA produced the 3΄-overhanging AA and TT dinucleotides for rejoining the DNA ends through base-pairing. Electrophoretic mobility shift assay showed that SprB promoted synapsis of SprA subunits bound to the two target sites during excision but impaired it during integration. In vivo data demonstrated that sprB expression that lasts until the late stage of sporulation is crucial for stable expression of reconstituted spsM without reintegration of the SPβ prophage. These results present a deeper understanding of the mechanism of the prophage-mediated bacterial gene regulatory system.

INTRODUCTION

Gene rearrangement is a phenomenon in which a programmed DNA recombination event occurs during cellular differentiation to reconstitute a functional gene from gene segments separated in the genome. The most studied cases of gene rearrangement are the antigen receptor (immunoglobulin and T-cell receptor) genes in vertebrate lymphocytes (1,2). The coding-sequences for the variable regions of the antigen receptor are split into V (variable), D (diversity), and J (joint) segments. In developing lymphocytes, the V(D)J segments are combined through DNA recombination reactions, depending on RAG1/RAG2 (recombination-activating genes) (3,4) and DNA repair proteins (2,5–10). This process generates antigen receptor diversity that allows adaptive immune defense against a large variety of pathogens. Gene rearrangement also plays crucial developmental roles in prokaryotes: nitrogen fixation in heterocysts of the cyanobacterium Anabaena spp. (11–13) and sporulation in spore-forming bacteria (14–22).

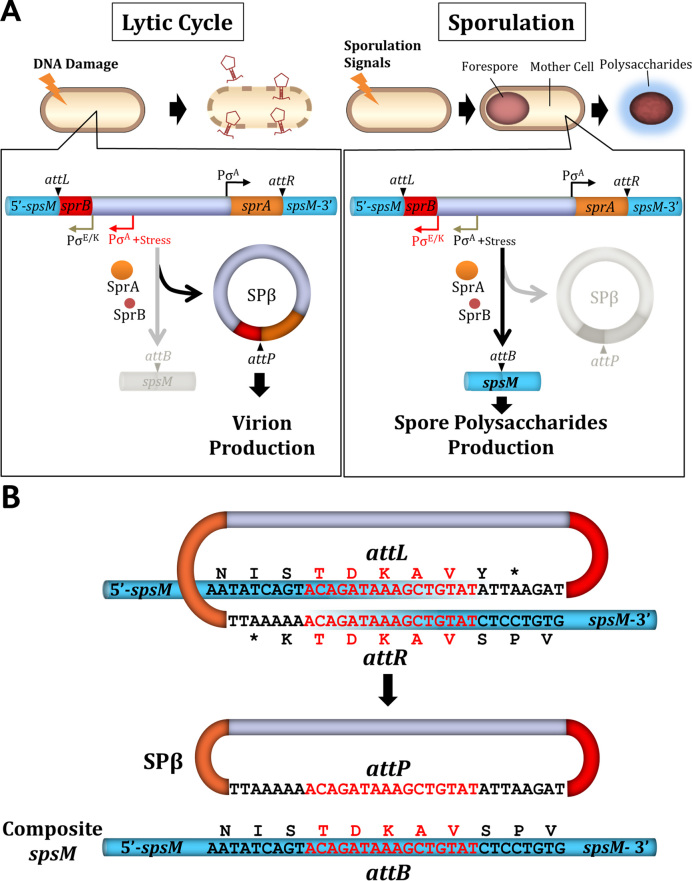

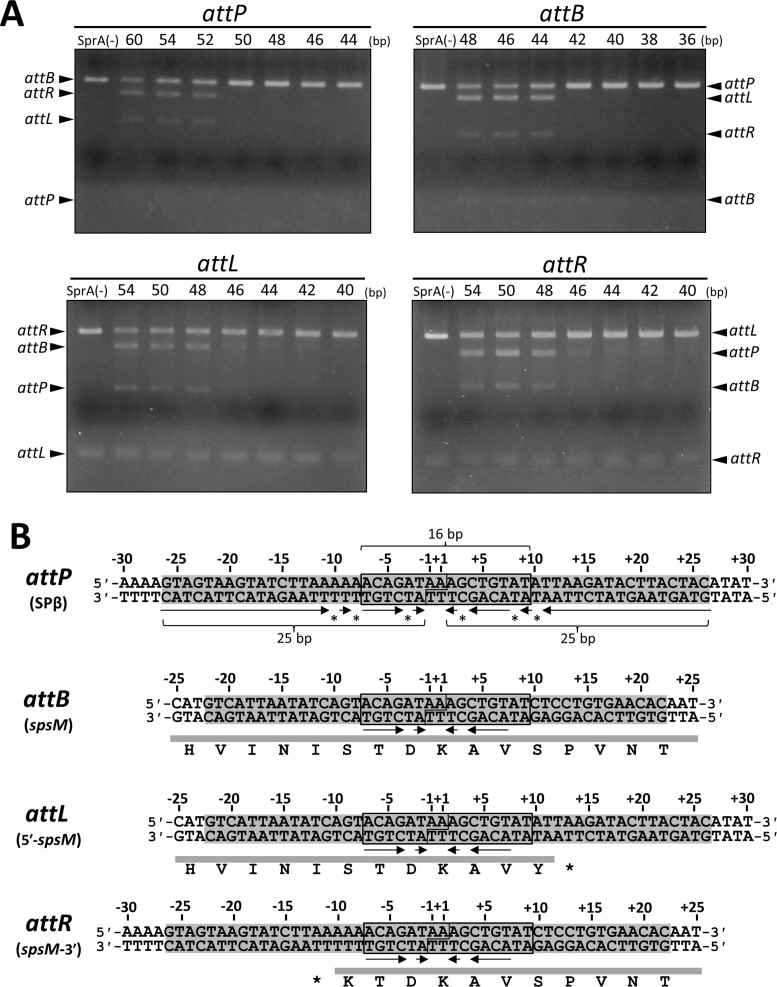

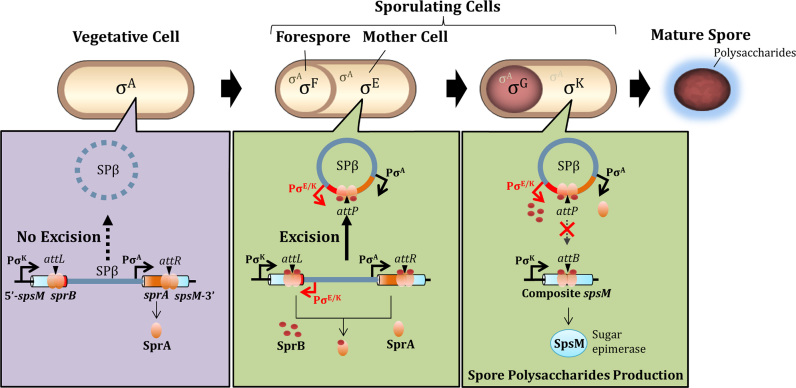

Sporulation-specific gene rearrangement was first reported in Bacillus subtilis sigK, which encodes a sporulation-specific sigma factor K (σK) (14). sigK is disrupted into two segments by the insertion of skin (sigK-intervening element), which is considered a remnant of the ancestral prophage (19). During sporulation, skin is excised from the chromosome to combine the ORFs in frame (14–16,18). Many other examples of sporulation-specific gene rearrangement, in addition to sigK, suggest that this phenomenon is wide-spread and common in spore-forming bacteria (20). In a previous study, we found that SPβ, an ‘active’ prophage, generates a gene rearrangement of spsM (spore polysaccharide synthesis M) in B. subtilis strain 168 (21). In addition to phage particle formation during the lytic cycle, the prophage is also excised from the genome to reconstitute spsM, which is essential for production of the spore surface polysaccharides (Figure 1A). The SPβ prophage divides spsM [encoding a 341 amino-acids (aa) protein] into two segments: 5΄-spsM (formerly yodU; 140 aa) and spsM-3΄ (formerly ypqP; 207 aa). The overlapping 16 bp nucleotide sequences ‘ACAGATAAAGCTGTAT’ (translated into ‘TDKAV’) are found in the 5΄-spsM and spsM-3΄ (Figure 1B). This implies that DNA recombination occurs within the sequences, although the precise position is unclear. The spsM rearrangement requires sprA and sprB in the prophage region (21). sprA is annotated to encode a putative phage integrase (Supplementary Figure S1A and B) (23), which is controlled by the housekeeping sigma factor (σA)-dependent promoter and is constitutionally expressed, regardless of cell status (21,24). sprB, encoding a protein of 58 aa in size (Supplementary Figure S1C), is under the control of the stress-responsible (σA) and sporulation-specific (σE/K) promoters, which are induced during the lytic cycle and sporulation, respectively.

Figure 1.

SPβ excision and spsM rearrangement. (A) Diagram of SPβ prophage excision in B. subtilis 168. In the lytic cycle, the excised SPβ DNA is incorporated into the phage capsids to produce the virion and the host cell undergoes lysis. During sporulation, the prophage excision generates functional spsM, which is necessary for production of the spore surface polysaccharides. (B) Nucleotide sequences of the junctions prior and posterior to DNA recombination (21). The 16 bp overlapping nucleotide sequence is indicated in red. Deduced amino-acids sequences are shown above or below the nucleotide sequences.

SprA is a 545 aa protein with a significant homology to the large serine recombinase (LSR) family proteins. LSRs are 450–700 aa proteins, containing a ∼130 aa catalytic domain (N-terminal domain, NTD) and a 300–500 aa DNA-binding domain (C-terminal domain, CTD) (25–29). The NTDs of the LSRs are very similar to that of a well-studied serine resolvase encoded by the transposable element γδ (25,30). The LSRs bind to their target DNA molecules as dimers, which are formed through NTD-NTD interactions (26,30–32). A serine residue within the NTD acts as a nucleophile to attack the phosphate group in the DNA backbone of the att core upon DNA cleavage (26,27,31–33). The CTD is responsible for DNA-binding properties (34–37) and can be subdivided into a recombinase domain (RD) and a zinc-ribbon domain (ZD) to recognize the nucleotides proximal and distal to the att core, respectively (38). Phage-encoded LSRs catalyze site-specific recombination between the phage and host DNA (26,27,29). An LSR dimer binds to the specific nucleotide sequences in the phage DNA (phage attachment site; attP) and host chromosome (bacterial attachment site; attB). The attP-LSR and attB-LSR subunits associate to form a tetrameric complex, called a synaptic complex. In the synaptic complex, cleavage and exchange of the DNA strands occur. Subsequently, attL and attR: the hybrids of attP and attB, are generated in the chromosome of the lysogen. Conversely, LSRs require a recombination directionality factor (RDF) for the excision reaction between the attL and attR sites (26,39–46). RDFs are typically small proteins, and they do not share any common motifs (41).

In the past, temperate phages that are integrated into the host genomes were considered to be in a dormant state. However, recent reports have described gene regulations mediated by prophages, such as the spsM rearrangement, in various bacterial species (47–51). This is called ‘active lysogeny’, and the bacteriophage research field regards this as a novel and significant interaction between phage and host (52). To date, the molecular basis and regulation of active lysogeny are poorly understood. In this study, we established an in vitro system for spsM rearrangement and revealed the structures of the att sites. We also characterized the DNA-recombinase complex formation by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) and atomic force microscopic (AFM) observations. Combined with in vivo data, our study deciphers the mechanism of active lysogeny at the molecular level for the first time.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table S1. Primers used in this study are shown in Supplementary Table S2. Escherichia coli DH 5α [New England BioLabs (NEB), MA, USA] and BL21 SHuffle T7 Expressing lysY (NEB) harboring plasmids were grown routinely in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium in the presence of 50 or 100 μg/ml ampicillin. Sporulation of B. subtilis was induced by cultivation at 37°C in Difco sporulation medium (DSM) with shaking.

Expression and purification of proteins tagged with six histidines at the C-termini

sprA and sprB genes were amplified by PCR with the primer sets, P1/P2 and P3/P4, respectively. PCR products were digested with NdeI and XhoI, and cloned into the NdeI–XhoI site of pET22b(+) vector (Merck Millipore, MW, USA) to obtain pET-sprAWT and pET-sprB. To generate pET-sprAS22A, mutations in pET-sprAWT were introduced by inverse PCR using the primer set P5/P6, and by self-ligation of the PCR product using the seamless ligation cloning extract (SLiCE) method (53). Escherichia coli cells harboring the expression vectors were grown to the exponential phase [optical density at 600 nm (OD600) = 0.5] at 30°C in LB medium containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin. Recombinant proteins were induced by addition of 0.5 mM IPTG at 22°C for 20 h (for SprA and SprAS22A) and at 30°C for 3 h (for SprB). Harvested cells were lysed in a solution containing 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 8.0), 0.3 M NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 1 × FastBreak reagent (Promega, WI, USA) and 0.1 mg/ml DNase I. Cell lysate was clarified by a brief centrifugation and loaded into HisTrap HP columns (GE Healthcare, NJ, USA). The recombinant proteins were eluted with a buffer containing 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 8.0) and 500 mM imidazole, and further purified using HiTrap Q and HiTrap SP columns (GE Healthcare). SprA was loaded into the HiTrap SP column and eluted with 200 mM NaCl. SprB was loaded into the HiTrap Q column and eluted with 100 mM NaCl. Concentrations of the protein samples were measured using a Bradford quantification kit (BioRad, CA, USA).

Preparation of DNA substrates for the in vitro recombination assay

The DNA substrates shown in Figures 2C, 2D, 3B, 7, and Supplementary Figure S9 were generated by PCR using the chromosomal DNA from the B. subtilis 168 vegetative and sporulating cells and the primer sets P7/P3 for attP (346 bp), P8/P9 for attB (828 bp), P8/P3 for attL (446 bp) and P7/P9 for attR (728 bp) substrates.

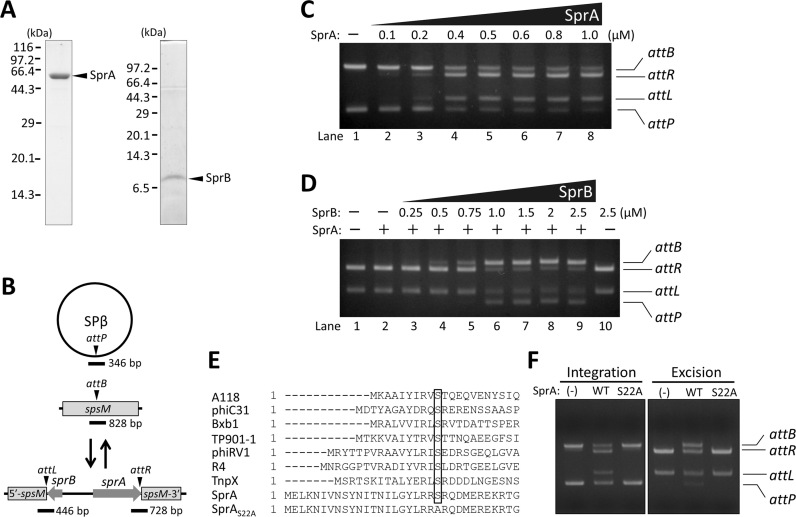

Figure 2.

In vitro recombination assays. (A) Preparation of recombinant SprA and SprB. Recombinant SprA and SprB tagged with the six histidines at their C-termini were purified by affinity chromatography. Purified SprA (2 μg) and SprB (1 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE (10% gel) and Tricine-SDS-PAGE (16.5% gel), respectively. (B) Schematic representation of the SPβ integration/excision reaction. Triangles point to the DNA cleavage sites during the recombination. Thick lines indicate regions corresponding to the DNA substrates for in vitro recombination. (C) Integration reaction. For attB and attP, 20 nM of each substrate were reacted with SprA (0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, 0.8 or 1.0 μM) at 37°C for 60 min. Reaction products were separated by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. (D) Excision reaction. For attL and attR, 20 nM of each substrate were reacted with SprA (0 or 0.5 μM) and SprB (0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0 or 2.5 μM) at 37°C for 60 min. The reaction products were loaded on a 2% agarose gel. +/–, presence or absence of SprA (0.5 μM) or SprB (2.5 μM). (E) Alignment of amino-acid sequences of the NTDs of the LSRs. The nucleophilic serine residue (S) is indicated by the box. (F) Impact of a substitution of the 22nd serine with alanine. In vitro integration/excision recombination assays were performed using wild-type and mutated SprA (0.5 μM) and SprB (1.0 μM). (-), absence of SprA; WT, wild-type SprA; S22A, SprAS22A.

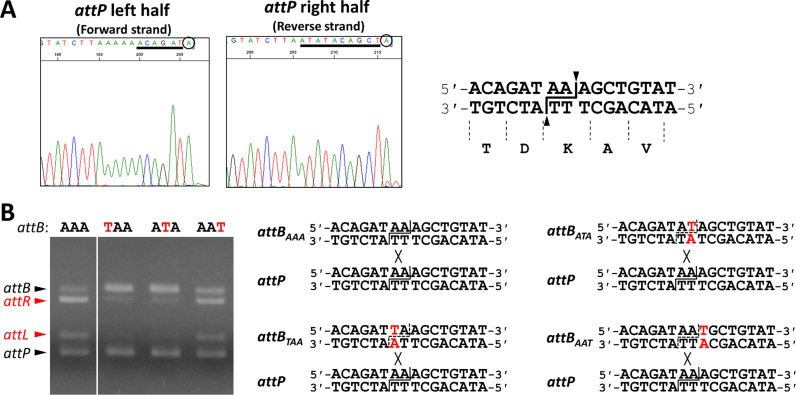

Figure 3.

DNA cleavage and strand exchange by SprA. (A) Direct sequencing of the intermediates of the SprA-mediated integration reaction. The intermediates: the left and right half-sites of attP, were directly sequenced using a BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit and an ABI 3500 DNA analyzer. The 16 bp overlapping sequence is underlined. The 3΄-end nucleotides indicated by the circles are adenines added by the terminal transferase activity of Taq polymerase used for the cycle sequencing reaction. The cleavage point of attP is shown to the left (indicated by the lines and triangles). (B) Effects of point mutations of the central dinucleotides on DNA recombination. Point mutations were introduced into the AAA nucleotides at the center of the attB site (A→T). In vitro integration recombination was performed using 0.5 μM SprA and 50 ng each of the wild-type attP and the mutated attB substrates.

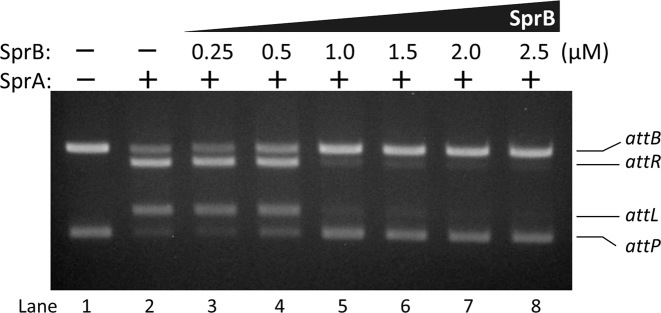

Figure 7.

Inhibition of integration by SprB. The attP and normal attB substrates (20 nM each) were reacted with 0.5 μM SprA in the presence of the various concentrations of SprB (0, 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0 or 2.5 μM) at 37°C for 60 min.

Introduction of mutations into the attB and attP substrates

The 828 bp attB and 346 bp attP DNA fragments were cloned into the pMD20 vector (pMD-B and pMD-P). The point mutations at the core dinucleotides shown in Figure 3B and Supplementary Figure S3 were introduced into pMD-B and pMD-P by inverse PCR using the primer sets P10/P11–P26 and P27/P28–P42, respectively. The PCR products were self-ligated using the SLiCE method. The mutated attP and attB substrates were amplified from the resulting plasmids with the primer sets P7/P3 and P8/P9, respectively. The attP and attB substrates of differing lengths, shown in Figure 4 and Supplementary Figure S5, were amplified from the 346 bp attP, 828 bp attB, 446 bp attL, and 728 bp attR substrates with the appropriate primer sets: P43–P50/P58–P65 (for attP), P74–P80/P88–P94 (for attB), P73–P80/P59–P65 (for attL), and P44–P50/P87–P94 (for attR). DNA fragments containing the attP (3,015 bp), attB (3,190 bp), attL (3,221 bp), and attR (2,984 bp) sites were amplified from B. subtilis vegetative and sporulating cells using the primer sets P100/P101 (for attP), P102/P103 (for attB), P101/P7102 (for attL), and P100/P103 (for attR). The attP, attB, attL and attR fragments containing deletions from either the right- or left-hand side were generated by PCR using the primers: P45–P49/P106 (for the attP left-hand side deletion), P107/P60–P64 (for attP right), P75–P79/P104 (for attB left), P105/P89–P93 (for attB right), P75–P86/P106 (for attL left), P105/P61–P72 (for attL right), P46–P57/P104 (for attR left) and P107/P87–99 (for attR right).

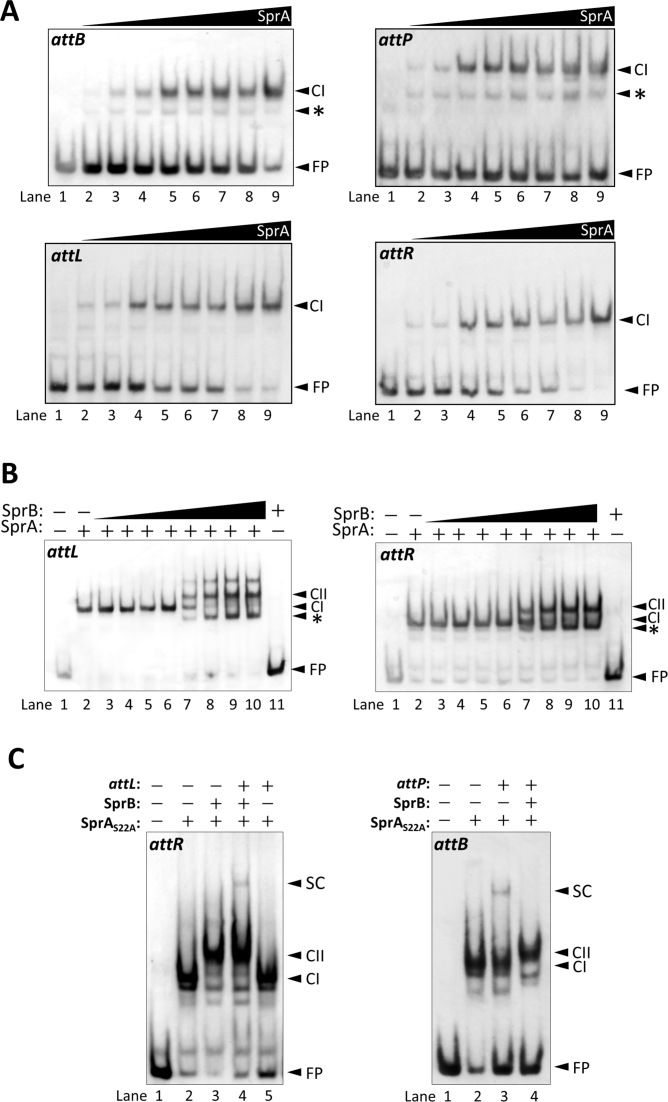

Figure 4.

Determination of the minimal att sites. (A) Evaluation of the recombination activities of the various-sized att substrates. Each ∼50 ng of 40–60 bp DNA fragments containing the att sites with progressive deletion from both ends were reacted with 0.5 μM SprA in the presence of 50 ng of the ∼3 kb DNA fragments containing the intact partner att sequences (attP, 3,015 bp; attB, 3,190 bp; attL, 3,221 bp; attR, 2,984 bp). Nucleotide sequences of the short att substrates are shown in (B). Schematic of the recombination reaction is illustrated in Supplementary Figure S4. Numbers above the panels indicate the sizes of the short att fragments. SprA (–) indicates the absence of SprA. (B) Nucleotide sequences of the minimal att sites. Nucleotide sequences of the four att sites are shown with their positions. The positions of −1 and +1 are assigned to the central nucleotides of the attP site. The minimal att sites are indicated by shading. The 16 bp consensus sequences are indicated by boxes. Arrows and asterisks denote the inverted repeat sequences and the mismatched nucleotides within the attP sites, respectively. The deletion series of the short att substrates were shown as below: attP60, from −30 to +30; attP54, −27 to +27; attP52, −26 to +26; attP50, −25 to +25; attP48, −24 to +24; attP46, −23 to +23; attP44, −22 to +22; attB48, −24 to +24; attB46, −23 to +23; attB44, −22 to +22; attB42, −21 to +21; attB40, −20 to +20; attB38, −19 to +19; attB36, −18 to +18; attL54, −25 to +29; attL50, −23 to +27; attL48, −22 to +26; attL46, −21 to +25; attL44, −20 to +24; attL42, −19 to +23; attL40, −18 to +22; attR54, −29 to +25; attR50, −27 to +23; attR48, −26 to +22; attR46, −25 to +21; attR44, −24 to +20; attR42, −23 to +19; attR40, −22 to +18.

In vitro recombination assays

Unless otherwise noted in the Figure legends, 20 nM of the DNA substrates, 0.5 μM SprA, and 1 μM SprB were reacted at 37°C for 60 min in 10 μl of the reaction solution containing 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 20 mM NaCl, and 0.1 mM DTT. The recombination reaction was stopped by the addition of 0.1% SDS and by heat treatment at 60°C for 3 min. Reaction products were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis. Signals were detected using EZ-Vision DNA Dye (AMRESCO, OH, USA).

Mapping of the attP cleavage site

PCR for a 2231 bp DNA fragment harboring the attP site was performed using the chromosomal DNA of the B. subtilis 168 sporulating cells and the P100/P108 primers. Two microgram of the PCR product were mixed with 0.3 μM SprA in 100 μl of the reaction solution containing 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 20 mM NaCl and 0.1 mM DTT. The reaction mixture was incubated at 37°C for 12 h in the presence of 30% ethylene glycol and 5% glycerol to accumulate the cleavage products (54). The cleavage products were treated by proteinase K, extracted by phenol, and precipitated using 100% ethanol. DNA pellets were dissolved in TE buffer, gel purified, and directly sequenced using the P107 (for the left half-site of attP) or P109 (for the right half-site) primers, a BigDye® Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, WI, USA) and an ABI 3500 DNA analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Electrophoresis mobility shift assays

DNA fragments containing the att sites were amplified with the primer sets P110/P61 (for attP; 89 bp), P111/P87 (for attB; 106 bp), P111/P58 (for attL; 111 bp), and P7/P87 (for attR; 132 bp). The second PCR was performed using a digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled primer P112 and a reverse primer: P61 (for attP), P87 (for attB and attR), or P58 (for attL). The second PCR products had additional five nucleotides (TCGTA) at 5΄-ends derived from the P112 primer. Non-labeled 232 bp attP and 237 bp attL fragments were amplified with the primer sets P7/P106 and P8/P58, respectively. Binding reaction mixtures containing 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 20 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM DTT, 0.1 mg/ml poly dIdC·dIdC (GE Healthcare), 10 nM probes, 0 or 20 nM non-labeled DNA, 0–0.4 μM SprA, and 0–12.8 μM SprB were incubated at 37°C for 30 min and separated by native-PAGE (4% polyacrylamide, 0.5 × TBE, 4°C, 5 W, 2 h). The gel after the electrophoresis was capillary-blotted onto a nylon membrane for 6 h using 10 × SSC. Signals were detected using anti-DIG antibody conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) and nitro-blue tetrazolium/5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-phosphate (NBT/BCIP; Roche).

Atomic force microscopy (AFM)

The attL and attR fragments amplified with the primers P113/P114 and P107/P115 were combined using an overextension PCR method. The resulting 1098 bp DNA (4.8 nM), SprA (0.5 μM) and SprB (1.6 μM) were reacted at 37°C for 15 min in 10 μl of the reaction solution containing 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH8.0), 20 mM NaCl and 0.1 mM DTT. AFM was performed in air with the tapping mode of a Multimode AFM (Veeco, CA, USA) and an Olympus silicon cantilever (OMCL-AC160TS-W2; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Imaging was carried out according to the method described previously (55) with a slight modification: the glutaraldehyde cross-linking step was omitted. Images were analyzed using the NANOSCOPE software.

Artificial induction of SPβ excision

BsINDB (21) was cultured at 37°C in 100 ml of LB medium. When the cells reached the mid-log phase (OD600 = 0.5), sprB expression was induced by the addition of 0.25 mM IPTG. Three hours after the addition of IPTG, cells were harvested and washed twice with 100 ml of fresh LB medium. Cell pellets were resuspended with 100 ml of fresh LB medium and divided into two parts: one part was further cultured at 37°C in the presence of 0.25 mM IPTG and the other part was in the absence of IPTG. One milliliter of the culture was harvested hourly after the addition of IPTG. Chromosomal DNA was isolated from the cells, digested with NdeI (NEB), and subjected to Southern hybridization with the spsM-specific probe as described previously (21).

Detection of SPβ reintegration during sporulation

To construct a B. subtilis BSIID strain carrying the PspoIID–sprB construct, pMUT-sprBind plasmid vector (21) was linearized by inverted PCR using the primer set P116/P117. A DNA fragment containing the spoIID promoter region was amplified from B. subtilis chromosomal DNA with the primer set P118/P119. The linearized vector and the insert DNA were ligated using the SLiCE method. The resulting plasmid harboring the PspoIID–sprB construct, pMUT-IID, was introduced into B. subtilis 168 via natural competence and integrated at the sprB locus through a single crossing-over event. The transformants carrying the PspoIID–sprB construct were selected on LB-agar plates containing 0.3 μg/ml erythromycin. The 168-AEB and BSIID-AEB strains carrying an ectopic attB site at the amyE locus were generated by transformation of B. subtilis 168 and BSIID with an amyE-integration vector harboring an intact spsM gene, pMFspsM (21). The 168-AEB and BSIID-AEB strains were induced to sporulation by cultivation at 37°C in 5 ml of liquid DSM. Chromosomal DNA was isolated from the sporulation cells at T0 and T8. To detect the reintegration, PCR was performed using 100 ng of chromosomal DNA with a combination of the sprB-specific primer P116 and the amyE-specific primer P120. Sporulating cells at T24 were negatively stained with Indian ink and observed by phase-contrast microscopy as described previously (21).

RT-PCR

B. subtilis 168 and BSIID cells were cultured at 37°C in 300 ml of liquid DSM. Every hour, 20 ml of the culture was harvested by centrifugation from T0 until T8. Total RNA was extracted according to the previously described method (56). A reverse transcription reaction was performed using 1 μg of total RNA, RevertAID reverse transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and the sprB-specific primer P121. The sprB cDNA was amplified by 20 cycles of PCR using Prime Taq (Genet Bio, Chungnam, Korea) and the primer set P116/P121. PCR products were analyzed using 2% agarose gel electrophoresis.

RESULTS

Site-specific DNA recombination catalyzed by SprA and SprB

In a previous study, we identified sprA and sprB to be essential factors for spsM rearrangement. SprA contains three distinct domains of the LSRs: NTD, RD and ZD (Supplementary Figure S1A), and thus is expected to play the central role in spsM rearrangement. SprB is likely to be the genetic switch for spsM rearrangement because sprB expression correlates with phage excision (21). To elucidate the site-specific recombination activity, sprA and sprB were cloned into the pET22b(+) expression vector. Recombinant SprA and SprB with six histidines fused to their C-termini were expressed in E. coli. Purified SprA and SprB migrated at approximately 62 kDa in SDS-PAGE (10% gel) and at 8.5 kDa in Tricine-SDS-PAGE (16.5% gel), respectively (Figure 2A). The 828 bp attB and 346 bp attP substrates (Figure 2B; 20 nM each) were reacted with the various concentrations of SprA at 37°C for 60 min and analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. Signals indicating the recombination products [attL (446 bp) and attR (728 bp)] were detected when more than 0.4 μM of SprA was added to the reactions (Figure 2C, lanes 4–8) while SprB was not required for the integration reaction. The conversion rate of the substrates to the recombinant products did not reach 100%. A similar case to this observation was reported in ϕC31 Int-mediated recombination (57).

We next examined the excision reaction. The 446 bp attL and 728 bp attR substrates (20 nM) were reacted with 0.5 μM SprA in the presence of various concentrations of SprB. Figure 2D shows that excision products appeared when the molar ratio of SprB to SprA was 1: 1 (Figure 2D, lane 4), and that the excision occurred efficiently when the ratio was more than 2:1 (lanes 6–9). Neither SprA nor SprB alone could catalyze the excision reaction (lanes 2 and 10). A single serine residue at the NTD of LSR is the nucleophile that cleaves the DNA strand (26). Alignments of the LSR amino-acids sequences disclosed that the 22nd residue of SprA was the nucleophile serine (Figure 2E, box). A serine-to-alanine substitution at the 22nd residue caused a loss of the integration/excision activities (Figure 2F, S22A). These results confirmed that SprA and SprB are an LSR and cognate RDF, respectively. The quantitative relationship between SprA and SprB for efficient excision (Figure 2D) implies that SprB may behave as a multimer, or at least a dimer, to promote the excision reaction. Consistent with this, Gp3, the RDF for Strepotomyces ϕBT1 phage integrase, is reported to form a dimer in solution (46). The requirement for a higher concentration of SprB than SprA for excision likely generates a threshold response of the spsM rearrangement. This would avoid unexpected excision in case of the leakage of sprB expression beyond the program of gene regulation during sporulation and the lytic cycle.

Mechanism of the spsM rearrangement and structure of SPβ att sites

The most significant issues regarding spsM rearrangement are how the precise rejoining of the spsM segments occurs and why spsM is targeted by the SPβ phage. Information on the catalytic features of SprA and the structures of the attP, attB, attL and attR sites for SPβ are necessary to answer these questions. One of the prominent features of SPβ att sites is the conserved sequence of up to 16 bp in the middle of the site (Figure 1B) which encodes the amino acids at positions 136–140 of SpsM. Such a long conserved sequence has never been reported in the att sites for other LSRs. Recombination was expected to take place within the conserved sequence. Because target DNA recognition and strand exchange are the central steps of the spsM rearrangement, we further studied the molecular basis of the precise spsM rearrangement and the structures of the att sites.

To determine the cleavage site of attP during recombination, a DNA fragment containing the attP site was reacted with SprA at 37°C overnight in the presence of 30% ethylene glycol and 5% glycerol to allow accumulation of the cleavage products (54). The sequencing data of the cleavage products suggested that SprA produced the 3΄-overhanging di-adenine nucleotides (AA) at the center of the attP site (Figure 3A and Supplementary Figure S2). From the conservation of the central 16 bp nucleotide sequence, the attB, attL, and attR sites will be cleaved by SprA at the same positions as attP. The overhanging dinucleotides originate from the first and second adenines of the lysine codon (AAA) within the 16 bp conserved sequence. To investigate the importance of three adenines for the DNA recombination, we carried out an in vitro recombination experiment using mutated attB substrates with single point mutations at each of the three adenines (Figure 3B). Integration reactions were performed using the mutated attB and the wild-type attP DNA. The mutated attB sites harboring either the TAA or ATA substitution (attBTAA and attBATA) exhibited ∼90% reductions in the recombination efficiencies. By contrast, the attBAAT site retained the recombination activity at a comparable level to the wild-type attB (attBAAA), indicating that SprA recognized the first and second adenines as the cleavage site but not the entire lysine codon. Efficient DNA recombination was accomplished when the central AA-dinucleotides were changed into T in both the attP and the attB sites (Supplementary Figure S3, AA, AT, TA and TT). This result suggests that the inability of the wild-type attP and either of attBTAA or attBATA to recombine resulted from non-complementary overhanging nucleotides, and not from a failure of the target DNA recognition by SprA due to the mutations. We conclude that the base-pairing of the 3΄-overhanging dinucleotides between the substrates is critical for re-joining. Production of 3΄-overhanging dinucleotides is a common catalytic feature of the LSR proteins, although the dinucleotides sequences vary from one recombinase to another (26,31,33,38). One plausible reason why all of the sporulation gene-intervening elements possess the LSR-encoding gene (e.g. spoIVCA in B. subtilis skin (15–18), ssrA in B. weihenstephanensis vfbin (20), Geoth_3268 in Geobacillus thermoglucosidasius (20)) may be to carry out precise gene rearrangements in a similar manner to SprA.

Next, we addressed the question of why SPβ targeted the spsM-coding region for lysogenization. To examine this, we analyzed the whole structure of the minimal SPβ att sites. To determine the minimal size requirements of the att sites, we created a series of att substrates with progressive deletions from both ends and evaluated their recombination efficiencies. The deletion series (36–60 bp) were reacted with SprA in the presence of ∼3 kb substrates containing the intact partner att sites (Figure 4A). The minimal att sites were defined as the shortest att substrates that showed >90% recombination efficiencies compared with the longest substrates of the deletion series used in this experiment (attP, 60 bp; attB, 48 bp; attL, 54 bp; attR, 54 bp). The deletion analysis revealed that the minimal attP, attB, attL and attR sites were 52, 44, 48 and 48 bp long, respectively. The overall sequences of the att sites are described in Figure 4B. We also confirmed the minimal size requirements using a series of att substrates with progressive deletions from either the left or right half-sites (Supplementary Figure S5). The sizes of the minimal att sites for SPβ were comparable to those for other serine recombinases (28). In general, attP sites for LSRs are ∼60 bp nucleotide sequences consisting of inverted repeat sequences that encompass the short conserved sequence, and their partner attB sites are ∼48 bp sequences that possess the conserved sequence but have no obvious similarity to attP (26). The minimal attP site for SPβ consists of the 16 bp perfect inverted repeat sequence (Figure 4B, attP, arrows), encompassing the 16 bp conserved sequence (Figure 4B, boxed nucleotides). Moreover, the inverted repeat can be extended into the conserved sequence and the attP site, and therefore create 25 bp symmetric sequences with respect to the central dinucleotides, which include only three mismatches (Figure 4B, attP, asterisks). These mismatches may serve as landmarks to distinguish the direction of the attP site. A sequence as highly symmetric as the SPβ attP site has never been found in other LSRs. Single point mutations to any nucleotides of the 16 bp conserved sequence of the SPβ attB site, except the nucleotide at position +9, reduced recombination efficiency (Supplementary Figure S7, 61%–89% efficiencies relative to that of the wild-type attB). In particular, the mutations at positions -6 (C→A) and +2 (A→C), which are located within the inverted sequence, caused 35% and 39% losses of efficiency, respectively, indicating the importance of these nucleotides for recombination. Nevertheless, the effects of the point mutations on recombination were moderate, compared with the replacement of the AA dinucleotides (Supplementary Figure S3). This suggests that the dinucleotides are critical for recognition by SprA as well as production of the overhanging ends for the precise rejoining reaction. In summary, the attP contains a perfect inverted repeat sequence surrounding the central 16 bp region that is identical to that of attB within spsM (406–421 nt). The central 16 bp region is also conserved in the two other recombination hybrids: attL and attR. Intriguingly, the conserved region has sequences of inverted symmetry flanking the central AA dinucleotides. As such, the short stretch of symmetric sequences around the AA dinucleotides in spsM appears to be favorable for recognition by SprA and would have been selected as the crossover site for the gene rearrangement system.

Analysis of protein-DNA complex formation by EMSA

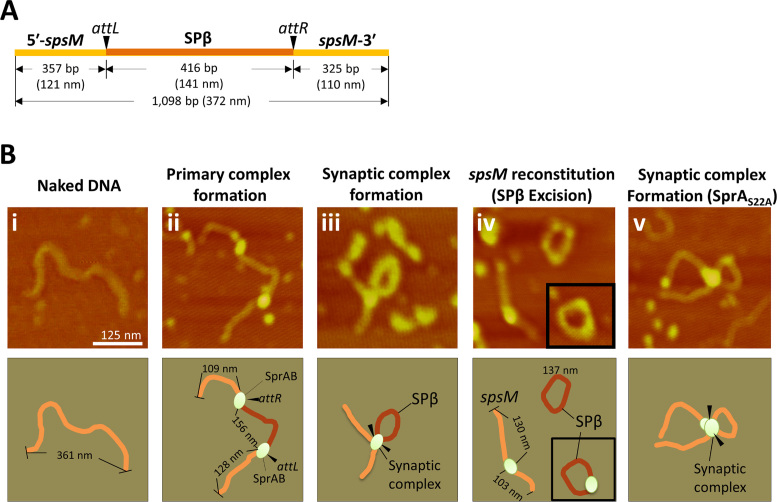

To investigate the complex formation of SprA, SprB, and the att sites, we carried out an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA). We examined the SprA-DNA complex formation using the 5΄-DIG-labeled att probes. After incubation at 37°C for 30 min, the reaction mixtures were separated by a 4% native acrylamide gel. SprA showed binding activity to all of the att probes [Figure 5A, complex I (CI)]. EMSA showed that SprA was able to bind to the attL and attR probes without SprB. The estimated dissociation constants (Kd) for the binding of the SprA dimer to the probes were 132 nM (for attB), 119 nM (for attP), 75 nM (for attL) and 70 nM (for attR). When the attP and attB probes were used, fast-migrating faint bands were detected, probably due to complexes of monomeric SprA and DNA (Figure 5A, top panels, asterisk). We next studied the formation of the SprA–SprB–DNA complex during excision. The addition of SprB generated super-shifted bands indicating the SprA–SprB-DNA complexes (Figure 5B, lanes 7–10, CII), while SprB alone did not exhibit DNA-binding activity (lane 11). SprB directly interacted with SprA (Supplementary Figure S8) and formation of the SprA–SprB complex is likely to be the rate-limiting step in the excision reaction because the complex could rapidly generate the excision products (Supplementary Figure S9, iii). Bands that migrated faster than the SprA-DNA complex were also observed when SprB was added (Figure 5B, lanes 7–10, asterisk). The fast migrating species were also reported in the ϕC31 Int and the RDF complex formation (45) but their nature is currently unknown. As was the case for the attL and attR sites, the SprA–SprB complex also exhibited binding activity to the attP and attB sites (Supplementary Figure S10).

Figure 5.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (A) SprA-DNA complex formation. For these assays, 10 nM of the DIG-labeled attP (94 bp), attB (111 bp), attL (116 bp), and attR (137 bp) probes were reacted with the various concentrations of SprA at 37°C for 30 min. SprA concentrations were as follows: 0, 25, 50, 100, 150, 200, 250, 300 and 350 nM. The reaction mixtures were separated by 4% native gels. FP, free probe; CI, SprA–DNA complex. Asterisks indicate SprA monomers bound to DNA. (B) SprA–SprB-DNA complex formation. The attL and attR probes (10 nM) were reacted with 0.4 μM SprA in the presence of 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.8, 1.6, 3.2, 6.4 or 12.8 μM SprB (lanes 3–10). FP, free probe; CI, SprA–DNA complex; CII, SprA–SprB–DNA complex; *, additional bands of unknown nature; +/−, presence or absence of 0.4 μM SprA and 12.8 μM SprB. (C) Synaptic complex formation. Here, 10 nM of each of the attR (left panel) and attB probes (right panel) were reacted with 0.4 μM SprAS22A in the presence or absence of 3.2 μM SprB and 20 nM non-labeled partner att DNA. FP, free probe; CI, SprA-DNA complexes; CII, SprA–SprB-DNA complexes; SC, synaptic complexes; +/−, presence or absence of 0.4 μM SprAS22A, 3.2 μM SprB, and 20 nM non-labeled att DNA.

Finally, we examined the synaptic complex formation during excision and integration using the attR and attB probes. In this experiment, SprAS22A was used instead of wild-type SprA to stabilize the synaptic complex. As shown in Figure 5C, the band retarded to a greater extent than the SprA–SprB-attR complex was indicative of the synaptic complex, and was detected in the presence of the non-labeled attL DNA [Figure 5C, left panel, lane 4, Synaptic Complex (SC)]. Depletion of SprB in the reaction resulted in the disappearance of the SC band (lane 5), indicating that during excision the synaptic complex depends on SprB. By contrast, synaptic complex formation during integration was accomplished under conditions without SprB (Figure 5C, right panel, lane 3, SC). Moreover, addition of SprB abolished the synaptic complex formation between the attB and attP sites (lane 4), although the SprA–SprB-attB complex was still observed (lane 4, CII).

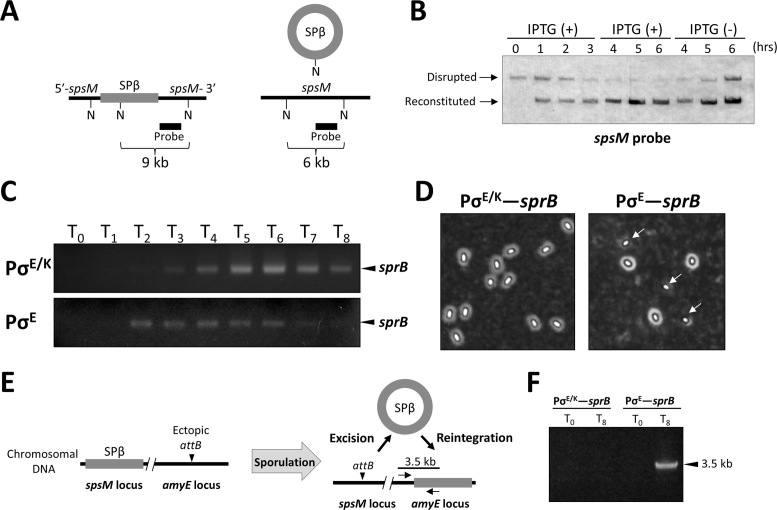

Visualization of the synaptic complex using atomic force microscopy (AFM)

We have demonstrated in vitro recombination and synaptic complex formation using two separate att substrates; however, in practice, the spsM rearrangement takes place on a single molecule of the chromosomal DNA in vivo. We verified the recombination reaction on a single DNA molecule by AFM imaging. We prepared a 1098 bp DNA substrate that contained the 5΄- and 3΄-portions of the disrupted spsM gene (Figure 6A). The size of the naked DNA measured from the AFM image was 361 nm in length (Figure 6B, i), consistent with the calculation (Figure 6A, 372 nm). The DNA substrate was reacted with SprA and SprB at 37°C for 15 min and observed in air by AFM. Panel ii shows the primary complexes without a synapsis of the subunits at the attL and attR sites. Bright points on the DNA indicate SprA and SprB bound to the att sites. The attL and attR sites were distinguishable by measuring the DNA length from the DNA ends to the SprA–SprB binding positions. Panel iii displays the synaptic complex. The internal region between the attL and attR sites (representing the SPβ prophage region) appeared to loop out from the complex. After the completion of the excision reaction, the circular DNA with or without SprA (Figure 6B, panel iv, top and bottom right) and the linear DNA were observed (Figure 6B, panel iv, left). The linear DNA was 233 nm in length, which was consistent with the calculated size of the reconstituted spsM (231 nm). When SprAS22A was used for AFM imaging instead of wild-type SprA, the complex containing SprAS22A stopped at the synaptic complex formation and could not proceed due to the defects in the DNA cleavage activity (Figure 6B, v). These AFM imaging data show each of the steps during the excision in vitro, establishing that the spsM rearrangement is accomplished by SprA and SprB without any other factors, such as host-encoded nucleoid proteins and DNA repair proteins. This is the first example of visualization of the synaptic complex formation during LSR-mediate DNA recombination.

Figure 6.

AFM imaging of the spsM rearrangement. (A) Schematic of a 1098-bp DNA substrate for AFM imaging. Size (nm) of the DNA molecule was calculated from one DNA base pair of 0.34 nm in length (68). (B) Representative images at each of the stages during the excision reaction. The DNA substrate (4.8 nM) was incubated with or without SprA (0.5 μM) and SprB (1.6 μM) at 37°C for 15 min and then observed using AFM. The top panels show the AFM images: i, naked DNA; ii, primary complex; iii, synaptic complex; iv, excised SPβ and reconstituted spsM; v, the synaptic complex containing SprAS22A. Scale bar indicates 125 nm. The bottom panels are illustrations of the AFM images. Actual sizes (nm) of the DNA molecules were measured from AFM images.

Inhibition of integration by SprB

EMSA data demonstrated that SprB inhibited synaptic complex formation of the attB and attP sites (Figure 5C, right panel). SprB, thus, was expected to block the integration reaction. To test this, various concentrations of SprB were added into the reactions containing the attB and attP substrates and SprA. We found that the integrative products disappeared in a SprB-dose-dependent manner (Figure 7, lanes 3–8). Signals of the integrative products began to decrease when the ratio of SprB to SprA in the reaction was 2:1 (lane 5), and completely disappeared at the ratio of 4.5:1 (lane 8), suggesting that SprB blocked the integration of SPβ DNA. Combined with the EMSA results (Figure 5C), we concluded that SprB inhibited the integration reaction by blocking the synaptic complex formation. Inconsistent with our result, only small amounts of the RDF (one-fourth of the Int concentration) were necessary to inhibit ϕBT1 Int integration activity (46). In another case, mv4Xis, the RDF for lactococcal phage mv4 tyrosine-type integrase, facilitated excision and integration at the same time (58). The control mechanism of the recombination directionality may vary from one Int/RDF system to another.

Repression of SPβ reintegration by SprB in vivo

Our in vitro study showed that SprB has a role in regulating the recombination directionality through promoting and repressing the synaptic complexes during the excision and integration, respectively (Figures 5C and 7). We therefore evaluated the regulatory effect of SprB on recombination in vivo. First, we investigated the control of recombination by SprB in vegetative cells using the BsINDB strain whose sprB is under the control of the IPTG-inducible promoter (21). BsINDB was cultivated in LB medium up to the mid-exponential growth phase, and SPβ excision was induced by the addition of IPTG into the medium. The disrupted or reconstituted spsM DNA was detected by Southern blotting using the spsM-specific probe (Figure 8A). A signal indicating the spsM rearrangement appeared 1 h and later after the addition of IPTG [Figure 8B, IPTG (+) 1–6 h, Reconstituted]. When IPTG was removed from the medium at 3 h, the SPβ DNA was steadily reintegrated into the chromosome [IPTG (−) 4–6 h]. This result confirmed that SprB acts as a genetic switch for spsM rearrangement.

Figure 8.

Repression of reintegration by SprB. (A) A schematic shows the B. subtilis spsM locus prior (left) and posterior (right) to the SPβ excision. Black and gray lines represent the spsM gene and the SPβ prophage region. N, NdeI-recognition sites; thick line, spsM-specific probe for Southern blotting. (B) Artificial control of SPβ excision and integration. The BsINDB strain harboring an IPTG-inducible sprB construct was cultured in the presence and absence of 0.25 mM IPTG, as described in the Materials and Methods section. Chromosomal DNA was extracted from the cells at indicated time points after the addition of IPTG (T = 0 h) and subjected to Southern hybridization. Disrupted, disrupted spsM (9 kb); Reconstituted, reconstituted spsM (6 kb). (C) Transcription of sprB during sporulation. Total RNA was isolated from the 168 and BSIID sporulating cells. The sprB cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA, amplified by 20 cycles of PCR, and analyzed using 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis. T0–8 denote the times after the onset of sporulation. Arrowheads indicate the RT-PCR products of sprB (D) Effect of a change in sprB expression pattern on spore morphology. Spores produced by the strain 168 (PσE/K–sprB) and BSIID (PσE–sprB) cells were negatively stained with Indian ink and observed using phase-contrast microscopy. Arrows indicate spores that lack the polysaccharide layer. (E) Schematic of the SPβ reintegration assay. B. subtilis strains, 168-AEB (PσE/K–sprB) and BSIID-AEB (PσE–sprB) possess an ectopic attB at the amyE locus. Reintegration of the excised SPβ into the amyE locus was detected by PCR using a combination of the sprB- and amyE-specific primers. (F) Detection of the reintegration. PCR was performed using chromosomal DNA from the 168-AEB and BSIID-AEB cells at T0 and T8 with the primers shown in the panel E. The arrowhead indicates the PCR product that corresponds to the 3.5 kb region within the amyE–sprB locus.

In B. subtilis 168, sprB is controlled by the stress-responsible and sporulation-specific promoters. Because the sporulation-specific sprB promoter (PσE/K) is recognized by σE-and σK-containing RNA polymerases, sprB is transcribed during the middle-to-late stages of sporulation (21). We constructed a mutant strain in which the sprB promoter was replaced with that of spoIID (designated as BSIID). The spoIID promoter (PσE) is recognized by the σE-containing RNA polymerase and is transcribed at the early stage of sporulation (59). RT-PCR detected the sprB transcripts at 4–8 h (T4–T8) after the onset of sporulation in the wild-type strain (Figure 8C, PσE/K) and at T2–T6 in BSIID (PσE). We found a morphological change between the wild-type and BSIID-B spores. All wild-type spores were surrounded by the polysaccharide layer, indicating that spsM rearrangement occurred in all the sporulating cells (Figure 8D, PσE/K–sprB), while 7.5% of total spores from BSIID-B were lacking the polysaccharide layer (PσE–sprB, arrows).

SPβ excision is essential for spsM activation and production of the spore polysaccharide layer in B. subtilis. This result implied failure of the excision or reintegration of the excised SPβ DNA in BSIID-B. To verify these possibilities, we introduced an ectopic attB site at the amyE locus of the wild-type and BSIID strains (designated as 168-AEB and BSIID-AEB, respectively) as shown in Figure 8E. Chromosomal DNA from the 168-AEB and BSIID-AEB sporulating cells at T0 and T8 were isolated to detect the reintegration by PCR with amyE- and sprB-specific primers. As the result, the amyE–sprB fragment was successfully amplified only at T8 in BSIID-AEB (Figure 8F), indicating that BSIID-AEB retained the SPβ excision activity and that the reintegration event occurred at the late sporulation phase. A quantitative PCR assay showed that reintegration was detected in 2.2% of the BSIID-AEB cells at T8 (Supplementary Figure S11). The reintegration rate was seemingly lower than the result from the microscopic observation (Figure 8D, right panel, 7.5%). This is because BSIID-AEB has two attB sites at the spsM and amyE loci, and BSIID was sampled at a later time point during the culture (T24) to obtain mature spores for observation. Sporulation-independent reintegration was also detected in both 168-AEB and BSIID-AEB, but at very low frequencies (∼0.06%), probably due to spontaneous excision during the overnight preculture and exponential growth in the DSM culture. Taken together, these results suggest that continuous expression of sprB throughout the sporulation phase is important for the maintenance of the reconstituted spsM gene and normal spore formation.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we have demonstrated that SprA and SprB are an LSR that acts as the SPβ phage integrase and the cognate RDF, respectively (Figure 2). In the spsM rearrangement, the 5΄-spsM and spsM-3΄ segments must be combined in frame. SprA precisely generates the 3΄-overhanging dinucleotides at the center of the att site during recombination (Figure 3). EMSA and the in vitro recombination assay demonstrated that SprB promoted excision while inhibiting integration by controlling synaptic complex formation (Figures 5C and 7). While typical prophages excised in the lytic cycle are packaged into the new phage particles, the SPβ prophage excised during sporulation is neither packaged into the virion nor reintegrated into the chromosome (21). Therefore, the control and maintenance of the recombination directionality has profound importance in the spsM rearrangement. We showed that depletion of SprB in the late sporulation phase led to failure of spore maturation due to the reintegration of SPβ DNA (Figure 8D and F). The in vivo data confirmed that SprB triggers phage excision and that the long-term expression of sprB is the key factor for maintaining the reconstituted spsM during sporulation.

On the basis of our in vitro and in vivo data, we propose a model for control of the spsM rearrangement (Figure 9): the SPβ phage integrase, SprA, is employed for the insertion of the phage DNA into the host chromosome upon infection. Even after prophage integration, sprA is constitutively expressed in the lysogen; however, it is insufficient for the prophage excision due to a deficit of SprB. When the host enters into the sporulation phase, the sprB promoter is induced in the mother cell compartment. Subsequently, the SprA–SprB complex is formed and catalyzes the excision to reconstitute spsM. Although the SprA–SprB complex has the ability to bind to the attP and attB sites, it cannot form the synaptic complex to generate reintegration. Thus, SprB exerts inhibitory effects on the reintegration to ensure the stable expression of functional spsM throughout the late stage of the sporulation phase. Transcription of spsM might also interfere with SprA binding to attB. The functional spsM gene is expressed at the late stage to produce the spore surface polysaccharides for the spore maturation. Our report is the first example to show the detailed mechanism of active lysogeny, mediated by RDF expression. The inhibitory effect of RDFs on integration is likely to be a general feature of phage-encoded RDFs for LSRs, as this phenomenon has been reported in the other RDFs such as ϕRv1 Xis (42) and ϕC31 Gp3 (45,57). SPβ employs this principle to achieve irreversible active lysogeny for B. subtilis spsM by embedding the late-mother-cell-specific promoter upstream of sprB. The developmentally-regulated spsM gene rearrangement is a good example case to use to explain the irreversible regulation of active lysogeny.

Figure 9.

A model for control of the irreversible regulatory switch for spsM. The schematic representation shows morphological changes during sporulation and the spsM rearrangement in B. subtilis 168. The housekeeping (σA) and sporulation-specific (mother cell, σE→σK; forespore, σF→σG) sigma factors are indicated in the schematic. In the SPβ lysogen, sprA is constitutively expressed in the vegetative phase; nevertheless, the excisional recombination does not occur due to the lack of SprB. During sporulation, SprB is expressed from the mid until the late stages and participates in the excision of SPβ prophage. The excised SPβ is prevented from reintegrating because the SprA–SprB complex cannot catalyze the integrative recombination. The inhibitory effect of SprB on reintegration allows the stable expression of functional spsM during sporulation. Stoichiometry of SprA and SprB in the complex is not considered in this cartoon.

Analysis of the structures of the SPβ att sites revealed that the 52 bp attP comprises an extremely symmetric nucleotide sequence (Figure 4B, attP). A single nucleotide deletion from the 5΄- or 3΄-end of the minimal attP site resulted in the almost complete loss of recombination activity (Figure 4A and Supplementary Figure S5), suggesting that conservation of the inverted repeat sequence is critical for SprA-medicated recombination. The attB site is 44 bp in size, which consists of left and right half-sites of equal length. Unlike attP, no obvious symmetry was found between each half-site of attB, except for the 16 bp conserved sequence (Figure 4B, attB). The 16 bp conserved sequence likely plays a crucial role in the catalytic activity of SprA. SprA can generate recombination products effectively only when the attP and attB sites carry the AA- or TT-central dinucleotides (Supplementary Figure S3). As indicated by the structure of attP (Figure 4B), the highly symmetric sequence is the key to the target recognition of SprA. The 16 bp conserved sequence within spsM is the symmetric sequence that contains the central AA-dinucleotides and, therefore, would be selected as the target for the ancestor of SPβ because of the unique sequence that met the requirements for SprA-catalyzed recombination. SprA might then have adapted to recognize the 44 bp stretch of DNA containing the conserved sequence within spsM in the history of evolution. The minimal attL and attR sites correspond to the hybrids of the minimal attP and attB sites (Figure 4B, attL and attR). Unexpectedly, when the substrates were 1 nt shorter than the minimal sites, excision occurred at ∼50% efficiency compared to that of the intact att sites (Supplementary Figure S5). A possible explanation for this is that the SprA bound to the longer att half-site serves to stabilize the DNA-binding of the other through protein-protein interactions. Alternatively, SprB may alter the nucleotide recognition properties of SprA. The attL and attR sites exhibited no symmetry because of the hybrids between attP and attB; nevertheless, the 16 bp conserved sequence provides them with a symmetric central region, which would support the binding of an SprA dimer. Such a long conserved sequence is also expected to be beneficial for the precise spsM rearrangement in the case of a change in the cleavage point, which may be caused by mutations in SprA.

The mechanism of SprA-mediated gene rearrangement seems to be very similar to mechanisms of recombination reported in other LSRs; however, two significant differences are found: target recognition by SprA and control of phage excision. The minimal size requirements of attP and attB for SprA are 4–10-bp longer than those for Bxb1 Int (attP, 48 bp; attB, 38 bp) and ϕC31 Int (attP, 39 bp; attB, 34 bp) (60). The central dinucleotides of the att sites for ϕBT1 and ϕC31 integrases can be changed between A, T, G and C, although all 16 combinations of the dinucleotides were not examined (61,62). Inconsistent with this, substitutions of the central dinucleotides of the SPβ attB and attP sites, especially with G and C, led to a critical loss of efficiency (Supplementary Figure S3). The requirement for the long att sites and the preference for the AA dinucleotides would be necessary for SprA to recognize recombination sites and achieve secure reconstitution at the 138th lysine codon (AAA) of spsM. Xu and colleagues reported that Bxb1 and ϕC31 integrases efficiently catalyzed site-specific DNA recombination in mouse and human cells, while SprA (referred to as SPBc) showed weaker activity and produced inaccurate recombination in the mammalian cells (63). SprA may be sensitive to the subcellular environment as well as to the target nucleotide sequence. Another significant difference is the control of phage excision. A requirement of RDF for phage excision is commonly found in phage-encoded LSRs (41), although they vary in size and amino acid sequence (e.g. Bxb1 RDF, 255 aa; ϕC31 RDF, 244 aa; SprB, 58 aa) (60). Interestingly, the Bxb1 prophage integrates into the groEL1 locus of the host genome (64), whose gene product is known to be necessary for biofilm formation in Mycobacterium; however, Bxb1 lysogens are defects in biofilm formation (65), suggesting that reconstitution of groEL1 does not occur. As described above, the developmentally-regulated excision of phage DNA and the maintenance by SprB in the host cell is a unique mechanism found in SPβ.

LSR-mediated site-specific DNA recombinations are being applied to genetic engineering in vitro (61,62) and in vivo (66,67), with the aim of genome engineering for living organisms and gene therapy. However, the currently-devised approaches are mostly based on LSR-mediated ‘integration’ reactions. Although RDF-mediated excision is a more complicated reaction than integration, it can become available for engineering as well, and will make LSRs into more powerful tools. As an example, the spsM rearrangement system, in which the target gene is controlled by the integration/excision of the prophage, is expected to be applied to protein expression systems. Further studies on the mechanism of LSR-mediated excision will be required for a better understanding of the fundamentals of the phage life cycle and future applications.

Supplementary Material

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

Grant-in-Aid for Scientific research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (KAKENHI) [15K18675 to K.A. and 15K07371 to T.S.]; MEXT-Supported Program for the Strategic Research Foundation at Private Universities from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan, and the Institute for Fermentation, Osaka (IFO). Funding for the open access charge: the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Sakano H., Rogers J.H., Huppi K., Brack C., Traunecker A., Maki R., Wall R., Tonegawa S.. Domains and the hinge region of an immunoglobulin heavy chain are encoded in separate DNA segments. Nature. 1979; 277:627–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schatz D.G., Ji Y.. Recombination centres and the orchestration of V(D)J recombination. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011; 11:251–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schatz D.G., Oettinger M.A., Baltimore D.. The V(D)J recombination activating gene, RAG-1. Cell. 1989; 59:1035–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Oettinger M.A., Schatz D.G., Gorka C., Baltimore D.. RAG-1 and RAG-2, adjacent genes that synergistically activate V(D)J recombination. Science. 1990; 248:1517–1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Alt F.W., Zhang Y., Meng F.L., Guo C., Schwer B.. Mechanisms of programmed DNA lesions and genomic instability in the immune system. Cell. 2013; 152:417–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ma Y., Pannicke U., Schwarz K., Lieber M.R.. Hairpin opening and overhang processing by an Artemis/DNA-dependent protein kinase complex in nonhomologous end joining and V(D)J recombination. Cell. 2002; 108:781–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Komori T., Okada A., Stewart V., Alt F.W.. Lack of N regions in antigen receptor variable region genes of TdT-deficient lymphocytes. Science. 1993; 261:1171–1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bertocci B., De Smet A., Weill J.C., Reynaud C.A.. Nonoverlapping functions of DNA polymerases mu, lambda, and terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase during immunoglobulin V(D)J recombination in vivo. Immunity. 2006; 25:31–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Li Z., Otevrel T., Gao Y., Cheng H.L., Seed B., Stamato T.D., Taccioli G.E., Alt F.W.. The XRCC4 gene encodes a novel protein involved in DNA double-strand break repair and V(D)J recombination. Cell. 1995; 83:1079–1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Grawunder U., Zimmer D., Fugmann S., Schwarz K., Lieber M.R.. DNA ligase IV is essential for V(D)J recombination and DNA double-strand break repair in human precursor lymphocytes. Mol. Cell. 1998; 2:477–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Golden J.W., Robinson S.J., Haselkorn R.. Rearrangement of nitrogen fixation genes during heterocyst differentiation in the cyanobacterium Anabaena. Nature. 1985; 314:419–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Golden J.W., Mulligan M.E., Haselkorn R.. Different recombination site specificity of two developmentally regulated genome rearrangements. Nature. 1987; 327:526–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Carrasco C.D., Buettner J.A., Golden J.W.. Programmed DNA rearrangement of a cyanobacterial hupL gene in heterocysts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1995; 92:791–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Stragier P., Kunkel B., Kroos L., Losick R.. Chromosomal rearrangement generating a composite gene for a developmental transcription factor. Science. 1989; 243:507–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sato T., Samori Y., Kobayashi Y.. The cisA cistron of Bacillus subtilis sporulation gene spoIVC encodes a protein homologous to a site-specific recombinase. J. Bacteriol. 1990; 172:1092–1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kunkel B., Losick R., Stragier P.. The Bacillus subtilis gene for the development transcription factor σK is generated by excision of a dispensable DNA element containing a sporulation recombinase gene. Genes Dev. 1990; 4:525–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Popham D.L., Stragier P.. Binding of the Bacillus subtilis spoIVCA product to the recombination sites of the element interrupting the σK-encoding gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1992; 89:5991–5995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sato T., Harada K., Ohta Y., Kobayashi Y.. Expression of the Bacillus subtilis spoIVCA gene, which encodes a site-specific recombinase, depends on the spoIIGB product. J. Bacteriol. 1994; 176:935–937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Takemaru K., Mizuno M., Sato T., Takeuchi M., Kobayashi Y.. Complete nucleotide sequence of a skin element excised by DNA rearrangement during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology. 1995; 141:323–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Abe K., Yoshinari A., Aoyagi T., Hirota Y., Iwamoto K., Sato T.. Regulated DNA rearrangement during sporulation in Bacillus weihenstephanensis KBAB4. Mol. Microbiol. 2013; 90:415–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Abe K., Kawano Y., Iwamoto K., Arai K., Maruyama Y., Eichenberger P., Sato T.. Developmentally-regulated excision of the SPβ prophage reconstitutes a gene required for spore envelope maturation in Bacillus subtilis. PLoS Genet. 2014; 10:e1004636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Serrano M., Kint N., Pereira F.C., Saujet L., Boudry P., Dupuy B., Henriques A.O., Martin-Verstraete I.. A recombination directionality factor controls the cell type-specific activation of σK and the fidelity of spore development in Clostridium difficile. PLoS Genet. 2016; 12:e1006312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lazarevic V., Dusterhoft A., Soldo B., Hilbert H., Mauel C., Karamata D.. Nucleotide sequence of the Bacillus subtilis temperate bacteriophage SPβc2. Microbiology. 1999; 145:1055–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nicolas P., Mader U., Dervyn E., Rochat T., Leduc A., Pigeonneau N., Bidnenko E., Marchadier E., Hoebeke M., Aymerich S. et al. Condition-dependent transcriptome reveals high-level regulatory architecture in Bacillus subtilis. Science. 2012; 335:1103–1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Smith M.C., Thorpe H.M.. Diversity in the serine recombinases. Mol. Microbiol. 2002; 44:299–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Grindley N.D., Whiteson K.L., Rice P.A.. Mechanisms of site-specific recombination. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2006; 75:567–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Smith M.C., Brown W.R., McEwan A.R., Rowley P.A.. Site-specific recombination by φC31 integrase and other large serine recombinases. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2010; 38:388–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Van Duyne G.D., Rutherford K.. Large serine recombinase domain structure and attachment site binding. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2013; 48:476–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Stark W.M. The Serine Recombinases. Microbiol. Spectr. 2014; 2, doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.MDNA3-0046-2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yuan P., Gupta K., Van Duyne G.D.. Tetrameric structure of a serine integrase catalytic domain. Structure. 2008; 16:1275–1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rowley P.A., Smith M.C.. Role of the N-terminal domain of φC31 integrase in attB-attP synapsis. J. Bacteriol. 2008; 190:6918–6921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Smith M.C., Till R., Brady K., Soultanas P., Thorpe H., Smith M.C.. Synapsis and DNA cleavage in φC31 integrase-mediated site-specific recombination. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004; 32:2607–2617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Keenholtz R.A., Rowland S.J., Boocock M.R., Stark W.M., Rice P.A.. Structural basis for catalytic activation of a serine recombinase. Structure. 2011; 19:799–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ghosh P., Pannunzio N.R., Hatfull G.F.. Synapsis in phage Bxb1 integration: selection mechanism for the correct pair of recombination sites. J. Mol. Biol. 2005; 349:331–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. McEwan A.R., Rowley P.A., Smith M.C.. DNA binding and synapsis by the large C-terminal domain of φC31 integrase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009; 37:4764–4773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Singh S., Ghosh P., Hatfull G.F.. Attachment site selection and identity in Bxb1 serine integrase-mediated site-specific recombination. PLoS Genet. 2013; 9:e1003490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mandali S., Dhar G., Avliyakulov N.K., Haykinson M.J., Johnson R.C.. The site-specific integration reaction of Listeria phage A118 integrase, a serine recombinase. Mobile DNA. 2013; 4:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rutherford K., Yuan P., Perry K., Sharp R., Van Duyne G.D.. Attachment site recognition and regulation of directionality by the serine integrases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013; 41:8341–8356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cole S.T., Brosch R., Parkhill J., Garnier T., Churcher C., Harris D., Gordon S.V., Eiglmeier K., Gas S., Barry C.E. 3rd. et al. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature. 1998; 393:537–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Breuner A., Brondsted L., Hammer K.. Novel organization of genes involved in prophage excision identified in the temperate lactococcal bacteriophage TP901-1. J Bacteriol. 1999; 181:7291–7297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lewis J.A., Hatfull G.F.. Control of directionality in integrase-mediated recombination: examination of recombination directionality factors (RDFs) including Xis and Cox proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001; 29:2205–2216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bibb L.A., Hancox M.I., Hatfull G.F.. Integration and excision by the large serine recombinase φRv1 integrase. Mol. Microbiol. 2005; 55:1896–1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ghosh P., Wasil L.R., Hatfull G.F.. Control of phage Bxb1 excision by a novel recombination directionality factor. PLoS Biol. 2006; 4:e186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ghosh P., Bibb L.A., Hatfull G.F.. Two-step site selection for serine-integrase-mediated excision: DNA-directed integrase conformation and central dinucleotide proofreading. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008; 105:3238–3243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Khaleel T., Younger E., McEwan A.R., Varghese A.S., Smith M.C.. A phage protein that binds φC31 integrase to switch its directionality. Mol. Microbiol. 2011; 80:1450–1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zhang L., Zhu B., Dai R., Zhao G., Ding X.. Control of directionality in Streptomyces phage φBT1 integrase-mediated site-specific recombination. PLoS One. 2013; 8:e80434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rabinovich L., Sigal N., Borovok I., Nir-Paz R., Herskovits A.A.. Prophage excision activates Listeria competence genes that promote phagosomal escape and virulence. Cell. 2012; 150:792–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Scott J., Nguyen S.V., King C.J., Hendrickson C., McShan W.M.. Phage-like Streptococcus pyogenes chromosomal islands (SpyCI) and mutator phenotypes: control by growth state and rescue by a SpyCI-encoded promoter. Front. Microbiol. 2012; 3:317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wang X., Kim Y., Wood T.K.. Control and benefits of CP4-57 prophage excision in Escherichia coli biofilms. ISME J. 2009; 3:1164–1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Luneberg E., Mayer B., Daryab N., Kooistra O., Zahringer U., Rohde M., Swanson J., Frosch M.. Chromosomal insertion and excision of a 30 kb unstable genetic element is responsible for phase variation of lipopolysaccharide and other virulence determinants in Legionella pneumophila. Mol. Microbiol. 2001; 39:1259–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bae T., Baba T., Hiramatsu K., Schneewind O.. Prophages of Staphylococcus aureus Newman and their contribution to virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 2006; 62:1035–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Feiner R., Argov T., Rabinovich L., Sigal N., Borovok I., Herskovits A.A.. A new perspective on lysogeny: prophages as active regulatory switches of bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015; 13:641–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Zhang Y., Werling U., Edelmann W.. SLiCE: a novel bacterial cell extract-based DNA cloning method. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012; 40:e55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Boocock M.R., Zhu X., Grindley N.D.. Catalytic residues of γδ resolvase act in cis. EMBO J. 1995; 14:5129–5140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Nakano M., Ogasawara H., Shimada T., Yamamoto K., Ishihama A.. Involvement of cAMP-CRP in transcription activation and repression of the pck gene encoding PEP carboxykinase, the key enzyme of gluconeogenesis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2014; 355:93–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Abe K., Obana N., Nakamura K.. Effects of depletion of RNA-binding protein Tex on the expression of toxin genes in Clostridium perfringens. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2010; 74:1564–1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Pokhilko A., Zhao J., Ebenhoh O., Smith M.C., Stark W.M., Colloms S.D.. The mechanism of φC31 integrase directionality: experimental analysis and computational modelling. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016; 44:7360–7372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Coddeville M., Ritzenthaler P.. Control of directionality in bacteriophage mv4 site-specific recombination: functional analysis of the Xis factor. J Bacteriol. 2010; 192:624–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Eichenberger P., Fujita M., Jensen S.T., Conlon E.M., Rudner D.Z., Wang S.T., Ferguson C., Haga K., Sato T., Liu J.S. et al. The program of gene transcription for a single differentiating cell type during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. PLoS Biol. 2004; 2:e328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Fogg P.C., Colloms S., Rosser S., Stark M., Smith M.C.. New applications for phage integrases. J. Mol. Biol. 2014; 426:2703–2716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Zhang L., Zhao G., Ding X.. Tandem assembly of the epothilone biosynthetic gene cluster by in vitro site-specific recombination. Sci. Rep. 2011; 1:141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Colloms S.D., Merrick C.A., Olorunniji F.J., Stark W.M., Smith M.C., Osbourn A., Keasling J.D., Rosser S.J.. Rapid metabolic pathway assembly and modification using serine integrase site-specific recombination. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014; 42:e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Xu Z., Thomas L., Davies B., Chalmers R., Smith M., Brown W.. Accuracy and efficiency define Bxb1 integrase as the best of fifteen candidate serine recombinases for the integration of DNA into the human genome. BMC Biotechnol. 2013; 13:87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kim A.I., Ghosh P., Aaron M.A., Bibb L.A., Jain S., Hatfull G.F.. Mycobacteriophage Bxb1 integrates into the Mycobacterium smegmatis groEL1 gene. Mol. Microbiol. 2003; 50:463–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ojha A., Anand M., Bhatt A., Kremer L., Jacobs W.R. Jr, Hatfull G.F.. GroEL1: a dedicated chaperone involved in mycolic acid biosynthesis during biofilm formation in mycobacteria. Cell. 2005; 123:861–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Xu Z., Brown W.R.. Comparison and optimization of ten phage encoded serine integrases for genome engineering in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. BMC Biotechnol. 2016; 16:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Farruggio A.P., Calos M.P.. Serine integrase chimeras with activity in E. coli and HeLa cells. Biol. Open. 2014; 3:895–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Watson J.D., Crick F.H.. Molecular structure of nucleic acids; a structure for deoxyribose nucleic acid. Nature. 1953; 171:737–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.