Impacts of infectious diseases on wildlife populations can be difficult to document when mortality is not observable. We present a technology that utilizes a highly conserved host response to viral disease to differentiate latent viral infections from active disease states and viral from bacterial diseases.

Keywords: viral disease, host transcriptome, disease biomarkers, wild populations, aquaculture, salmon

Abstract

Infectious diseases can impact the physiological performance of individuals, including their mobility, visual acuity, behavior and tolerance and ability to effectively respond to additional stressors. These physiological effects can influence competitiveness, social hierarchy, habitat usage, migratory behavior and risk to predation, and in some circumstances, viability of populations. While there are multiple means of detecting infectious agents (microscopy, culture, molecular assays), the detection of infectious diseases in wild populations in circumstances where mortality is not observable can be difficult. Moreover, if infection-related physiological compromise leaves individuals vulnerable to predation, it may be rare to observe wildlife in a late stage of disease. Diagnostic technologies designed to diagnose cause of death are not always sensitive enough to detect early stages of disease development in live-sampled organisms. Sensitive technologies that can differentiate agent carrier states from active disease states are required to demonstrate impacts of infectious diseases in wild populations. We present the discovery and validation of salmon host transcriptional biomarkers capable of distinguishing fish in an active viral disease state [viral disease development (VDD)] from those carrying a latent viral infection, and viral versus bacterial disease states. Biomarker discovery was conducted through meta-analysis of published and in-house microarray data, and validation performed on independent datasets including disease challenge studies and farmed salmon diagnosed with various viral, bacterial and parasitic diseases. We demonstrate that the VDD biomarker panel is predictive of disease development across RNA-viral species, salmon species and salmon tissues, and can recognize a viral disease state in wild-migrating salmon. Moreover, we show that there is considerable overlap in the biomarkers resolved in our study in salmon with those based on similar human viral influenza research, suggesting a highly conserved suite of host genes associated with viral disease that may be applicable across a broad range of vertebrate taxa.

Introduction

Aquatic fishes are naturally exposed to a wide array of infectious agents that can impact their performance and survival, yet mere exposure to a pathogen does not always result in disease development. Disease development is a manifestation that depends upon host susceptibility, pathogen virulence and environmental conditions (Scott, 1988; Hedrick, 1998; Harvell et al., 2009), and disease ensues when the host sustains sufficient damage to perturb homeostasis (Casadevall and Pirofski, 1999). Compromised immunity in individuals living under stressful environmental conditions or those already responding to pre-existing infections can enhance disease susceptibility (Wedemeyer, 1970, 1996; Harvell et al., 2009).

Highly virulent pathogens can cause acute diseases that affect both healthy and compromised individuals in a population. However, while we know that their impacts can be devastating under high density culture conditions where contact rates between infected and uninfected individuals is high (Anderson and May, 1986), there is some question whether acute diseases, often caused by viral infections, result in the same population-level impacts in wild populations due to reduced transmission potential at low densities. The exception would be fish species that school at high densities, such as herring, for which massive mortality events due to viral hemorrhagic septicemia virus (VHSv) have been observed (Skall et al., 2005). Alternately infectious agents that cause chronic infections, allowing for broader transmission potential in low density populations, and impacting physiological performance rather than directly causing mortality, may, in fact, be more impactful in lower density fish populations (Miller et al., 2014).

Traditional fish health investigations generally start with observed mortality, and utilize diagnostic methods to identify the cause of death of individuals in a late- or final-stages of disease. Histopathology visualizes damage to the tissue to identify the cause of death, to classify the disease, and if infectious, to identify directly or to propose the pathogen(s) that are likely causative. Parasitic and bacterial infections may be observable microscopically, but unless viruses form inclusion bodies, they are not generally visible. However, once a pathogen is suspected, targeted immunohistochemistry or in situ hybridization can be used to verify the presence of a specific agent, including viruses, and to localize the agent within the region of tissue damage. Pathogen culture can also be attempted for suspected viral or bacterial infections, but not all pathogenic species are amenable to culture. All of these approaches are most effective at resolving late-stage disease. Molecular technologies have improved diagnostics for viruses and other pathogens difficult to assay by traditional means (Hungnes et al., 2000; Lafferty et al., 2004), and can provide highly sensitive detections (Mackay et al., 2002). Recently, multi-pathogen monitoring systems for characterized agents have been developed using molecular [microfluidics qPCR (described below); Miller et al., 2016] and serological (VirScan; Lungat and Petrova, 2015) technologies, and metagenomics has been applied to identify novel agents (Mokili et al., 2012).

The challenges to our understanding of the role of infectious diseases in wild fish are numerous. In many environments, like the ocean, mortality events may not be readily observable, as dying fish may sink down the water column or be quickly taken by an array of marine, avian and terrestrial predators. Moreover, infectious diseases that impact physiological performance—e.g. swimming ability, visual acuity, schooling, feeding behavior, ability to maintain ion homeostasis—may considerably enhance risk of predation (Miller et al., 2014). In such cases, where predators are abundant, it may be rare for infectious disease to directly kill fish, and as such, it may be difficult to sample fish at a late stage of disease development. As a result, while laboratory challenge studies may resolve pathogens capable of causing disease and impacting performance of wild fish, actually documenting their impacts in a wild context may require a new generation of tools that are more sensitive to resolving earlier stages of disease development than those traditionally utilized in the fish health diagnostic community.

We recently developed a high throughput molecular microfluidics approach to quantitate dozens of infectious agents (viruses, bacteria, fungal and protozoan parasites) in salmon in 96 samples at once (Miller et al., 2016). This platform has been applied to resolve the spatial and temporal distributions of infectious agents in migratory salmon (Miller et al., 2014), and could be easily modified to conduct strain-typing within a species to identify virulence factors or to aid in the interpretation of specific disease outbreaks, as has been done for human Streptococcus strain variants (Dhoubhadel et al., 2014). With our multi-agent quantitative monitoring system, we find that in wild migratory salmon, mixed infections are common, and few fish are agent-free. However, most individuals do not carry multiple infectious agents at appreciable loads (i.e. abundances). While pathogen loads are not a direct indication of disease, for pathogens causing acute diseases, there is greater potential for disease manifestation (i.e. damage) at higher loads (Johnson et al., 2004). In fact, truncation in load distributions, whereby there are fewer individuals carrying high loads of an infective agent than expected under a normal distribution, has been one method used by parasitologists to identify potential linkages between parasites and mortality in field-based studies (Lester, 1984). However, documenting a physiological impact, be it at molecular, protein, cellular or whole organism level, would be a more direct and powerful means to demonstrate disease manifestation.

In the human health arena, molecular diagnostics of the host are increasingly being utilized to identify diseases and to characterize the molecular basis of cellular damage for the development of targeted therapeutants (Ross and Ginsburg, 2003). Because tissue damage is often caused by disruption of molecular pathways, molecular diagnostic tools can be highly sensitive to the detection of early stage disease even before cellular damage or outward symptoms are apparent (Woods et al., 2013; Andres-Terre et al., 2015). For infectious diseases, molecular tools can potentially distinguish between latent infections, where the agent may be detected but due to lack of pathogen activity there is minimal host response, from active, disease causing infections, where higher loads of infectious agents are present and strong differential activation of immunity and cellular processes that ultimately can lead to tissue damage (i.e. disease) occurs. What is less clear, however, is how well such methodologies would work in situations where multiple infectious agents may be present.

In a recent study on human viral influenza, researchers conducted an integrated, multi-cohort analysis over a broad range of microarray-based transcriptome studies to identify host biomarkers predictive of viral influenza as well as those predictive of general viral respiratory disease (Andres-Terre et al., 2015). Uniquely, instead of carefully controlling a myriad of technical variables by choosing only studies conducted on a single array platform, a single tissue and designed in a similar manner, to increase the robustness of the biomarkers resolved, they instead incorporated variation in molecular platforms, tissues profiled, and included a range of study designs—some contrasting viral influenza versus healthy controls, others viral versus bacterial respiratory infections, with separate studies explored in discovery and validation sets. The biomarkers discovered could discriminate, based on host gene activity alone, individuals developing general viral respiratory infections, viral influenza, bacterial respiratory infections and disease free individuals. Not only did the biomarker panel resolved identify the presence of infectious disease before outward symptoms were present, but the panel was effective across saliva and blood samples. This study provides the foundation of the work that we have undertaken to identify biomarkers predictive of viral disease development (VDD) in salmon that can be applied alongside our broad-based microfluidics pathogen monitoring system to differentiate latent viral infections from the presence of viral disease. We are ultimately interested in expanding this technology to identify bacterial disease development and diseases associated with different families of microparasites.

The study undertaken herein identifies a host VDD biomarker panel that can effectively characterize the development of a viral disease state across a range of hosts, tissues and virus species. We started with a published study by Krasnov et al. (2011) in which transcriptome analyses were performed on Atlantic salmon from viral challenge studies for infectious anemia virus (ISAv), infectious pancreatic necrosis virus (IPNv), piscine orthoreovirus (PRv) and piscine myocarditis virus (PMCv), and analyses were undertaken to identify early viral response genes (VRG) differentially regulated across multiple viral diseases. While the VRG were not identified using highly advanced statistical methods, they served as a starting point for our multi-cohort data meta-analyses, which incorporated both our own transcriptome challenge studies and published, publicly available studies. In our approach, we focused much of our refinement of this initial set of biomarkers on in house and published microarray challenge studies based on an RNA virus endemic to salmon in British Columbia that was not part of the Krasnov study (infectious hematopoietic necrosis virus; IHNv). Validation of the 45 biomarker VDD panel was performed by applying microfluidics qPCR on samples from three sets of in-house studies independent of the discovery samples and analyses: (i) IHNv challenge studies to assess the classification ability of the panel across multiple salmon species and tissues, (ii) diagnostic samples from a BC Chinook salmon farm outbreak of viral jaundice/anemia to assess classification ability of fish undergoing a novel viral disease across tissues and (iii) diagnostic samples from moribund/recently dead farmed salmon collected as part of a regulatory audit program to discern whether the panel could distinguish (RNA) viral disease from bacterial and parasite-induced diseases. Our final application of the VDD panel was on naturally migrating Sockeye salmon smolts, some of which carried high loads of IHNv, to determine if a viral disease state could be detected in live-sampled wild fish.

Materials and methods

VDD biomarker discovery—published multi-cohort microarray datasets

The research to define a suite of host biomarkers consistently associated with VDD in salmon across a range of RNA viral species began with multi-cohort data from publically available microarray datasets. Data from three published microarray studies were used in the initial identification of biomarkers associated with VDD across viral species. In Krasnov et al. (2011), the salmon SIQ array was applied to a series of challenge studies on Atlantic salmon based on four different salmon viruses, ISAv, IPNv, PMCv and PRv. This study aimed to resolve consistent VRG differentially regulated in early disease development for all RNA viruses in salmon, very similar to the objective of our research. Our study additionally aimed to determine if a viral disease state could be predicted both in the primary infective tissue and in non-destructive gill tissue, even for infections whereby gill tissue is not a primary target of the virus, and whether we could identify a panel that could additionally differentiate viral from bacterial disease states. The panel of 25 VRG identified by Krasnov and colleagues were utilized in virtually all evaluation and validation steps performed herein based on studies independent of the Krasnov study. However, as most of the published and in house studies explored herein were based on GRASP salmon arrays (16K and 32K; GRASP web.uvic.ca/cbr/grasp; B.F. Koop and W. Davidson), we first mapped the features defined in Krasnov across the SIQ and GRASP arrays for microarray exploration.

The second study considered was by Skjesol et al. (2011), which applied the SFA 2.0/immunochip (GPL6154; UKU_trout_1.8K_v1) on head kidney cDNA from Atlantic salmon challenged with two different field isolates of IPNv showing different levels of virulence [NFH-Ar (virulent) versus NFH-El (avirulent)], documenting host response elicited by each at 13 days post injection (five samples each plus four controls). The third study considered was by Purcell et al. (2011), which applied the GRASP16k array on anterior kidney cDNA from Rainbow trout challenged with virulent and avirulent strains of IHNv [4 controls, 4 IHNv M-type (virulent strain) and 4 IHNV U-type (avirulent strain)].

Significant gene lists from each of these published challenge studies were combined to form signature CS0301u, representing the union of 532 features which formed the basis of exploratory analyses and refinement of the biomarker panel based on analyses of independent in-house IHNv microarray datasets (described below).

A fourth published study by LeBlanc et al. (2010), whereby the cGRASP32K array was applied on head–kidney cDNA from Atlantic salmon at multiple time points post injection challenge with ISAv (81 samples including controls), was not used in the initial analyses, but the consistency in the directional activity of VDD biomarkers eventually identified was compared back to the findings of this study.

Molecular Genetics Laboratory (MGL) IHNv challenge datasets—refinement of viral disease biomarkers and qRT-PCR validation of VDD panel across species and tissues

In 2005, we conducted a series of IHNv challenges (ip-injection and waterborne) on four salmon species [Atlantic (Salmo salar), Sockeye (Onchorhynchus nerka), Chum (O. keta) and Chinook (O. tshawytscha)] carrying different susceptibilities to the IHN virus (listed most to least, respectively). Anterior kidney collected from a portion of the fish from the ip-challenges was used in microarray studies, as described in Miller et al. (2007). Herein, we explored the data from the microarray challenge studies to refine the CS0301u signature panel by identifying the features most consistently differentially regulated among salmon species as they developed IHN. We utilized the remaining fish and tissues from ip- and waterborne challenge studies as one of the four datasets applied to the qRT-PCR validation of the VDD panel.

Pacific salmon used in challenge studies were obtained from DFO hatcheries and moved to the fish holding facilities at the Pacific Biological Station. Atlantic salmon were obtained from a commercial freshwater production site. All experimental challenges were conducted with post-smolts, after gradually switching from fresh to salt water an acclimation period of several weeks was allowed prior to challenge. Experimental groups of fish were challenged with IHN virus (strain 93-057; genogroup U) by intraperitoneal injection [0.1 ml with IHN virus containing 1.4−2.8 × 104 plaque forming units [pfu] (slight variation among species)] and by waterborne exposure to the virus (8.0 × 103–1.2 × 104 pfu/ml) for 1 h. Control fish were injected with 0.1 ml of sterile Hanks balanced salt solution.

Within each challenge study, five salmon were sampled on alternate day's post-challenge, and anterior kidney, liver, spleen and gill tissues were removed and flash frozen at −80°C until extraction. For each species, five control samples were also collected from uninfected fish at time point zero. Fish handling and microarray protocols followed Miller et al. (2007), and herein we only present the variances from this study (based on an Atlantic salmon ip-challenge). All microarray studies were performed using the salmon GRASP16K microarray. A pooled reference design was utilized to calculate relative gene expression ratios across samples. For all but Atlantic salmon, the standard reference was constructed by pooling the total RNA extracted from four tissues (gill, spleen, head kidney and liver) collected from Sockeye salmon during the injection challenge. In Atlantic salmon, a pooled reference that combined total RNA from all kidneys collected in an Atlantic salmon waterborne challenge experiment was used.

Samples available from challenge studies are shown in Table 1A, which also depicts (in parentheses) the portion of samples analyzed for biomarker refinement from microarray studies. In each microarray study, a time-series of samples post-challenge (5 per collection date) was compared to mock-challenged fish collected on Day 0.

Table 1:

Experimental study designs for biomarker validation studies, by species and tissues sampled. (A) Total samples analyzed from IHNv challenges, with the subset analyzed in microarray analyses to facilitate biomarker discovery-refinement shown in parentheses. (B) Chinook salmon farm samples collected during a jaundice/anemia outbreak. Disease status was determined by a veterinarian at the farm site and confirmed via histopathology. Healthy controls were a combination of healthy fish from the same farm and fish from an adjacent farm with no jaundice. (C) Farm audit samples collected between 2011 and 2013 by quarter. Audit samples include moribund/recently dead samples from randomly selected farms throughout British Columbia. Mixed-tissue RNA samples for each individual were analyzed with the VDD biomarkers. (D) Gill samples from Sockeye salmon smolt outmigrants. Collections occurred over 3 years, 2007, 2011 and 2012 at the Fraser River Chilko Lake smolt fence. In 2012, smolts were acoustically tagged and tracked (Jeffries et al. 2014). 2007 was a year of very poor smolt survival

| A. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue | Challenge | Sockeye | Atlantic | Chum | Total |

| Head kidney | Injected | 45 (45) | 40 (25) | 45 (20) | |

| Waterborne | 50 | 116 | 45 | ||

| Gill | Injected | 45 | 5 | ||

| Waterborne | 45 | 115 | 43 | ||

| Liver | 45 | ||||

| Injected | 45 | ||||

| Spleen | 45 | ||||

| Injected | 45 | ||||

| Grand total | 275 | 276 | 133 | 684 | |

| B. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Tissue | Total | Jaundice/anemia |

| Gill | 36 | 16 |

| Head kidney | 35 | 16 |

| Liver | 36 | 16 |

| Spleen | 31 | 13 |

| Heart | 36 | 16 |

| Grand total | 174 | |

| C. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Quarter | Atlantic | Pacific | Total |

| 2011 | 116 | 32 | ||

| 1 | ||||

| 2 | 42 | 14 | ||

| 3 | 34 | 6 | ||

| 4 | 40 | 12 | ||

| 2012 | 46 | 10 | ||

| 1 | 45 | 9 | ||

| 2 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 3 | ||||

| 4 | ||||

| 2013 | 78 | 26 | ||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 2 | 1 | |||

| 3 | 39 | 16 | ||

| 4 | 38 | 8 | ||

| Grand total | 240 | 68 | 308 | |

| D. | |

|---|---|

| Year | N |

| 2007 | 14 |

| 2011 | 18 |

| 2012 | 181 |

Jaundice syndrome dataset—qRT-PCR validation of VDD panel across tissues on a natural viral disease outbreak

Jaundice syndrome is a disease impacting farmed Chinook salmon in BC that holds a striking resemblance to a disease in farmed Coho salmon in Chile (Godoy et al., 2016) and farmed Rainbow trout in Norway (Olsen et al., 2015). All are suspected to be viral-induced, with the PRv being the one virus common to outbreaks in all three species/countries; there has been no research to date to determine the nature of the relationship between PRv and these outbreaks. Anterior kidney, liver, heart, spleen and gill tissues were collected during a farm outbreak of jaundice syndrome, clinically characterized by jaundice and anemia, with collections including both sick and dying fish and healthy controls (Table 1B). Disease classification was determined through veterinary diagnostics comprised of clinical and histopathology data.

Farm audit samples—qRT-PCR validation of VDD panel across viral and bacterial diseases

Samples of dying farmed salmon were made available from the Fisheries and Ocean Canada regulatory farm audit program. These samples are collected to monitor background losses in production populations, to detect ongoing or recent health events within the industry, and to ensure reporting compliance with OIE (World Organization of Animal Health) listed diseases. Farm audit samples are collected on randomized BC farms, with one to six fresh silver (recently dead) fish sampled per farm audit in 2011–13. At the time of collection, clinical and environmental data are noted, and tissue samples are taken for histopathology, bacterial and viral culture and molecular analysis. Veterinary diagnostics were conducted on these samples prior to our application of the VDD, and were based largely on histopathology and clinical data. Our team had already conducted quantitative molecular analyses of 45 infectious agents known or suspected to cause disease in salmon on cDNA/DNA from combined tissues (heart, liver, head and anterior kidney, gill, pyloric caeca, spleen), so the backdrop of known infectious agents was determined for each sample. The VDD biomarkers were applied on this same cDNA from 240 farmed Atlantic salmon and 68 farmed Chinook salmon collected from 2011 to 2013 (Table 1C). We utilized these data to assess the ability of the VDD to discriminate fish experiencing viral- versus bacterial- or parasite-induced diseases based on tissue pools.

Application to wild salmon

The ultimate goal of the VDD biomarker development was to develop a tool that could not only identify the distribution of infectious agents in wild migratory salmon, but could also discriminate between latent viral carrier and disease states using a non-destructively sampled tissue. Throughout our larger research program we have utilized gill tissue (tips of 1–2 gill filaments) to biopsy fish with minimal impact on performance (reviewed in Cooke et al., 2005). Our final VDD validation study was based on Sockeye salmon smolts leaving their freshwater natal rearing lake (Chilko Lake in the Fraser River, BC). In 2012, we conducted an acoustic tracking study and assessed linkages between 18 infectious agents and 50 stress and immune-related genes and migratory fate. We showed that fish with high loads of IHNv and those containing a correlated antiviral type signature (including up-regulation of MX and STAT1, the two genes overlapping with the VDD biomarkers) generally disappeared within the first 80 km of downstream migration (Jeffries et al., 2014), likely due to enhanced risk of predation by resident Bull trout (Furey, 2016). We applied the validated VDD biomarkers on the 213 smolts from the Jeffries study collected at the Chilko smolt fence in 2007, 2011 and 2012 to determine if there was evidence of viral disease in these fish (Table 1D).

Statistical approach

Meta-analysis for VDD discovery

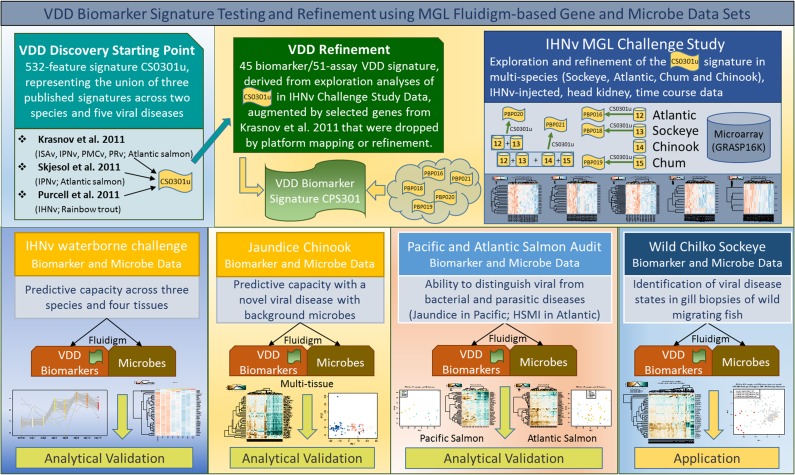

Analyses for the development of the VDD biomarkers was broken up into four segments (see schematic in Fig. 1). The first three analysis segments utilized microarray datasets. The first segment simply combined the significant gene lists from the three published studies (into signature CS0301u), after first mapping the genes for each onto the GRASP microarrays upon which our own studies were based. The second analysis segment involved refining the CS0301u signature set by meta-analysis of the multi-species microarray datasets from our own IHNv challenges. In addition to validating signature CS0301u on Atlantic, Sockeye and Chum salmon challenge data (resulting in feature panels PB0P16-PBP019), this signature was also validated in combined Atlantic and Sockeye (PBP020), and combined Atlantic, Sockeye, Chum and Chinook salmon challenge datasets (PBP021) (Table S1). This multi-species, multi-signature approach focused on identifying robust biomarkers across species and viral pathogens. In each exploration analysis, genes with strong discrimination capabilities were identified using unsupervised clustering approaches. Unsupervised methods are exploratory in nature, but they can be applied to a subset of validation data based on a specific signature to identify a smaller set of genes that consistently separate groups of interest. We utilized the gene shaving algorithm which provides an automatic feature selection by applying principle component analysis (PCA) iteratively to ‘shave off’ genes and create a sequence of clusters with different sizes (Hastie et al., 2000). Final cluster selection is based on a comparison of specific cluster-variance measures with similarly derived measures for randomized data. This method offers the most ‘coherent’ subset of genes across a sequence of cluster candidates.

Figure 1:

Schematic of viral disease development (VDD) discovery, refinement, validation and application datasets. The VDD discovery dataset was identified from published microarray viral challenge studies that included five RNA virus species. In house (MGL) IHNv challenge microarray studies across four salmon species were used to refine the VDD panel. Analytical validations of the qRT-PCR assays developed to 45 biomarkers within the VDD panel was performed using independent in-house studies that tested discrimination abilities of the proposed VDD between latent and disease-associated viral infections across tissues, salmon and viral species, as well as differentiation of fish undergoing viral, bacterial, and parasitic diseases. The VDD panel was then applied to wild migrating Sockeye salmon smolts to discern whether wild fish infected with IHNv could be identified in a VDD state.

The third analysis segment involved exploration of the overlap between feature panels resolved by gene shaving (described above) and the consistency of their directional response both within the in-house and published microarray studies. These analyses yielded a feature panel of 38 biomarkers, coined CPS301, that were up-regulated across a range of RNA-viral challenge studies and salmon species based on the primary infective tissues for each (Table S2). As there were a number of potentially important genes resolved by Krasnov et al. (2011) that either did not map to the GRASP16K array or were removed due to quality issues, we added 15 additional biomarkers to our proposed VDD panel. This panel included some paralogs to the same genes (from Krasnov).

Development of TaqMan assays for universal deployment across multiple salmon species

In order to develop TaqMan assays specific to the gene paralog of interest, all proposed VDD biomarkers were mapped onto the Atlantic salmon genome and gene paralogs identified. Where available, sequence alignments were generated to include gene paralogs from Atlantic and Pacific salmon species, and assays were designed to match only one paralog across all species. In general, we designed and tested 2–3 assays per targeted gene paralog. Assay efficiencies were determined on the Fluidigm BioMark HD platform using serial dilutions of mixed tissues derived from each species. Assays with efficiencies between 0.9 and 1.1 were considered optimal. Occasionally, assays did not work across all species, and alternate assays had to be used in some species. In some instances, none of the assays worked for certain species. Some of the proposed VDD genes did not have sufficient sequence data across species to design effective assays; these were dropped from our analysis. In total, 51 TaqMan assays to 45 biomarkers (some to paralogs of the same gene) were developed for validation across three independent datasets (Table 2).

Table 2:

TaqMan assays applied in validation studies, including host VDD biomarkers, 3 host housekeeping genes and 12 infectious agents, performed on host cDNA. For the full list of assays used in the Chinook salmon jaundice study and audit studies, see Miller et al. (2016)

| Description | Assay name | Gene ID | Biomarker origin | F Sequence | R sequence | Probe Sequence | EST | Assay efficiencies | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VDD biomarkers | Atlantic | Sockeye | Chum | Chinook | Coho | Pink | |||||||

| Barrier to autointegration factor | BAF_MGL_4 | BANF1 | Krasnov | CCAACTGAACCATGTCTGGAAA | GTCCCGGTGCTTTTGAGAAG | AAGGAAGGACCCCCC | BT049316 | 0.83 | |||||

| Unknown protein [Siniperca chuatsi] | CA038063_MGL_1 | CPS301 | TGTCCCTCTTCAAGACCTCGTT | AACATGTCTTCATTGTTGGTACAAAAG | CAGAAGTGATGAAAGCAG | CA038063 | 0.86 | 0.91 | 1.06 | 0.88 | |||

| Mitochondrial ribosomal protein (VAR1) | CA054694_MGL_1 | VAR1 | CPS301 | CCACCTGAGGTACTGAAGATAAGACA | TTAAGTCCTCCTTCCTCATCTGGTA | TCTACCAGGCCTTAAAG | CA054694 | 0.81 | 0.83 | 0.93 | 0.91 | 0.85 | |

| CD68 molecule | CD68_MGL_3 | CD68 | CPS301 | GATGATGAGGATAAGGAGGACAATC | GGGACTTCGGCACATCTGA | CCACAGCAATGGC | CA048910 | 0.75 | 0.89 | 0.87 | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.91 |

| CD9 protein | CD9_MGL_2 | CD9 | CPS301, Krasnov | CTTGATCTGTTTCATGAGGATGCT | ACCTCCTCCTGTTGCTCCTAGA | CAGCACACCAGGGC | CA064247 | 0.83 | 0.9 | 1.02 | 0.9 | 0.93 | 0.83 |

| Similar to interferon-inducible protein Gig2 (CD9) | GIG2-1_MGB1 | CD9 (GIG2-L) | CPS301, Krasnov | GAAAAGAGTACTAAAAATCAGGGTGGAT | GGGTGGTTCTGCCTGTCTATG | TCGGCAGGGTTAAGG | CA054168 | 1 | 0.89 | ||||

| GIG2-1_MGB2 | CD9 (GIG2-L) | CPS301, Krasnov | ATCAAAGTCATCGAGGTCATGAAG | GACTCCACTCTGAAGATGATCATACTG | TTACCGAAGAGAACTTATC | CA054168 | 0.86 | 0.89 | |||||

| GIG2-1_MGB3 | CD9 (GIG2-L) | CPS301, Krasnov | AACACTATGCAGTGGAACTGATGAA | GACCATGAGGTGATGCTGGAT | TCTGCATTCAGTGGGAG | CA054168 | 0.91 | ||||||

| ATP-dependent RNA helicase | DEXH_MGL_1 | DDX58 | Krasnov-not 16K | CCATAAGGAGGGTGTCTACAATAAGAT | CTCTCCCCCTTCAGCTTCTGT | TGGCGCGCTACGTG | FN396359 | 0.78 | 0.97 | 1.19 | 0.86 | 0.96 | 0.83 |

| DEXH_MGL_3 | DDX58 | Krasnov-not 16K | TGGAGAAGAAGGGTGTGACAGA | CGCAGGTGGAGAGCACACT | AGGAACAGACTGCTGGC | FN396359 | 0.9 | 0.88 | |||||

| RNA helicase—RIG-I | RIG1_MGLSYBR_1 | DDX58 (RIG1) | Krasnov | GACGGTCAGCAGGGTGTACT | CCCGTGTCCTAACGAACAGT | TGTCCAATTTAGGATTCTCCTTCTGCCC | DY714827 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.86 | 0.84 | 1.01 | 0.9 |

| Slime mold cyclic AMP receptor | DICTY-CAR_MGL_2 | DICTY | CPS301 | TCAACTTTGACAGTGGTCAGATAGC | TCCTTTTTTCCTCCTTATGATTGG | TGAGGTAGAAGTTGCCTTT | CB494001 | 0.91 | 0.97 | 0.92 | 1 | 1.12 | 0.95 |

| Galectin-3-binding protein precursor | GAL3_MGL_2 | LGALS3BP | CPS301 | TTGTAGCGCCTGTTGTAATCATATC | TACACTGCTGAGGCCATGGA | CTTGGCGTGGTGGC | CB515011 | 0.95 | 1 | 1.03 | 1.11 | 1.03 | 0.89 |

| Guanine nucleotide-binding protein-like 3 | GNL3_MGL_1 | GNL3 | CPS301 | GCCCAGTCTAACCCAAAAGCT | GGGTCCTGACGGCCTCTAG | CCATGGCGCTGAGG | CB499134 | 0.87 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.86 | 1.01 | 0.89 |

| Similar to KIAA1593 | KIAA_MGL_1 | HERC4 | Krasnov-not 16K | GATCGCTACCTTCATCTGAATCTTG | CTGTTCTTGACGGGCTGTGA | CATGCCCAGGATGG | EG841846 | 0.76 | 1.12 | 0.87 | 0.79 | 0.87 | |

| Probable E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase HERC6 | HERC6_1 | HERC6 | CPS301 | AGGGACAACTTGGTAGACAGAAGAA | TGACGCACACACAGCTACAGAGT | CAGTGGTCTCTGTGGCT | CA060884 | 0.87 | 0.86 | 1.07 | 0.85 | ||

| IFN-induced protein | IFI_MGB2 | Krasnov | GCTAGTGCTCTTGAGTATCTCCACAA | TCACCAGTAACTCTGTATCATCCTGTCT | AGCTGAAAGCACTTGAG | NM_001 124 333 | 1.01 | 0.93 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.91 | 0.85 | |

| Interferon induced with helicase C domain 1—IC | IFI-1C_MGL_2 | IFIH1 (MDA5) | Krasnov | TCCCCAGAGCAGACTGGTTT | AGAGCCCGTCCAAAGTGAAGT | TTGCAGCTTCTACAACTG | GE823089 | 0.79 | 0.88 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.99 | 0.89 |

| Interferon-induced 35 kDa protein homolog | IFI35_MGL_2 | IFI35 | CPS301 | CAACCAAGCCAGGGATGTAGA | GCTCTCTGGATCTCCCTCTTCA | AAAGGAAGAAGATAGCCGCC | CA064047 | 0.78 | 0.79 | 0.92 | 0.85 | ||

| IFN-induced protein 44-1 | IFI44A_MGL_2 | IFI44 | Krasnov-not 16K | CGGAGTCCAGAGCAGCCTACT | TCCAGTGGTCTCCCCATCTC | CGCTGGTCCTGTGTGA | GS365948 | 0.8 | 0.71 | 0.73 | 0.76 | 1.18 | |

| IFI44C_MGL_3 | IFI44 | Krasnov | GGCAAACCGCTGCCAAT | CCCTGTGGCCTCCTCCAT | TTTTGTGTGACACGATGGG | EV384577 | 0.85 | 0.81 | 0.84 | 0.88 | 0.87 | 0.8 | |

| Interferon-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 5 | IFIT5_MGL_2 | IFIT5 | CPS301, Krasnov | CCGTCAATGAGTCCCTACACATT | CACAGGCCAATTTGGTGATG | CTGTCTCCAAACTCCCA | CA051350 | 0.97 | 0.93 | 0.9 | 0.98 | 1.03 | 0.95 |

| Interferon regulatory factor 7 | IRF7_MGL_2 | IRF7 | CPS301 | ACACCCTGAACCCAGGAAGA | AAAGCACATGTGGATGGTATAGTCA | CAAAATGAAATGGTACAACTG | CN442559 | 0.89 | 0.96 | 1.07 | 0.97 | 1.05 | 0.86 |

| Interferon-induced GTP-binding protein Mx | MX | MX1 | In house | AGATGATGCTGCACCTCAAGTC | CTGCAGCTGGGAAGCAAAC | ATTCCCATGGTGATCCGCTACCTGG | CB516446 | 0.65 | 0.78 | 0.9 | 0.97 | N/A | N/A |

| Zinc finger NFX1-type | NFX_MGL_2 | NFX1type | Krasnov | CCACTTGCCAGAGCATGGT | CGTAACTGCCCAGAGTGCAAT | TGCTCCACCGATCG | FQ635861 | 0.83 | 0.87 | 0.73 | 0.84 | 0.81 | 0.84 |

| PLAC8-like protein 1 | PLAC8L1_MGL_1 | PLAC8L1 | CPS301 | GAGAACGCTACGGCATCCA | CCATCTGGCACCAGGTACAGA | CATTGGTGTGTTGCTGC | CA047116 | 0.89 | 0.87 | 0.84 | 0.88 | 0.98 | 0.85 |

| Urokinase plasminogen activator surface receptor precursor | PLAUR_MGL_3 | PLAUR | CPS301 | CAGTCTCCACTATCTACCTGTTGTGTGT | TGTGACGCCCCAAGGAA | AGCCCCTTTCACTGGA | CA057830 | 0.82 | 0.97 | 0.82 | 0.96 | 1.02 | 0.89 |

| Proteasome subunit beta type-8 precursor | PSMB8_1 | PSMB8 | CPS301 | CATGTCTGGTAGTGCTGCTGACT | TCTGCTTGTTCCTCAGTTTGTACAG | CAGTACTGGGAGAGACT | CA061622 | 0.81 | 0.84 | 0.85 | 0.86 | 0.93 | 0.86 |

| Proteasome subunit beta type-9 precursor | PSMB9A_MGL_2 | PSMB9 | CPS301 | GTTGCCCAGGATGCATTTCT | CCATGAGTCGAGATGGTTCGA | ATAGTGACAAGGTAGGCCAC | CA064302 | 0.87 | 0.85 | 0.91 | 0.99 | 0.93 | 0.91 |

| Retinoic acid-inducible gene-1 | RAD_MGL_2 | RAD1 | Krasnov | GGTGATGAGGAGGAGGGTGAA | CAAACTGCTCGGTGTACTGGAA | CCATGACGACTATCTC | FN178459 | 0.88 | |||||

| RING finger protein 213 | RNF213_MGL_5 | RNF213 | CPS301 | GTAATATGAGTGACGTGAAAGTG | TCGGTCGATCTCTGTGT | TTTGTGGACCTGGCCTCCATCTC | CA053171 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.89 | 0.93 | 1.05 | 1.01 |

| UNKNOWN | E3RNF213_2 | RNF213 | CPS301 | CTCCAGATTCTCCAGCAGACATT | GTACTCTTGATCCTTTGGGAAGCT | TTCTCAGACCACAACCAT | CA059288 | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.96 | 0.83 |

| Radical S-adenosyl methionine domain-containing protein 2 | RSAD_MGB2 | RSAD2 (viperin) | CPS301, Krasnov | GGGAAATTAGTCCAATACTGCAAAC | GCCATTGCTGACAATACTGACACT | CGACCTCCAGCTCC | CA038316 | 0.89 | 0.79 | 0.89 | 0.85 | 1.02 | 0.8 |

| Receptor-transporting protein 3 | RTP3_MGL_1 | RTP3 | Krasnov | TTCCATTAAGGCAGACAGTGTGA | TCCAAATGCCCCACTGATGT | ATCAGGCTGGCATCAG | EG825775 | 0.79 | |||||

| Sacsin | SAC_MGB1 | SACS | Krasnov | TCAGTCAGGCCCAGTGTGATC | GGCCCTGCCTCCTGTGT | AGCTGCTGCTCACAAC | EG906096 | 0.88 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.97 | ||

| SAC_MGB2 | SACS | Krasnov | GTACATCAGGCCGTGGAGAAG | GGAGATGGAGCTGTCTTTGTAATAATG | TGTCTTCTGTACTCTGCTGCCACC | EG906096 | 0.87 | ||||||

| Tyrosine-protein kinase FRK | SRK2_MGB3 | FRK | CPS301, Krasnov | CCAACGAGAAGTTCACCATCAA | TCATGATCTCATACAGCAAGATTCC | TGTGACGTGTGGTCCT | CB492720 | 0.92 | 0.82 | 0.96 | 1.17 | 0.95 | 1 |

| Signal transducer and activator of transcription 1-alpha/beta | STAT1 | STAT1 | CPS301 | TGTCACCGTCTCAGACAGATCTG | TGTTGGTCTCTGTAAGGCAACGT | AGTTGCTGAAAACCGG | CA050950 | N/A | 1.03 | 0.82 | 0.76 | N/A | N/A |

| Fish virus induced TRIM-1 | TRIM1_MGB1 | TRIM1 | Krasnov-not 16K | CATGATGTCTGGTGTTGATGTATATTG | GAGACAGAGAACCAACTGAGAAAACATA | TTGTCATTCAGAACCATTG | AM887808 | 0.99 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.96 |

| 52 kDa Ro protein-2 − 52Ro | 52RO_MGL_3 | TRIM21 | Krasnov | TGCACTATTGCCCAGTAACCAT | TGCAAGAGGAGATGCCAACA | AGTAGGATTCACAGAGAGTT | CX141267 | 0.85 | 1.04 | 0.99 | 1.11 | 0.91 | |

| MHC class I antigen (Salmo salar) | UBA_MGL_CA050178_1 | MHC1uba | CPS301 | GATCTACTCCGTTCCAGCCATT | TATGGATCTGTGTTTACAGTGTGTGTGT | TTATGATCTGTCCTCCCC | CA050178 | 0.91 | |||||

| UBA_MGL_CA050178_4 | MHC1uba | CPS301 | CAGTAAGATATGTTCTAAACAGCAAAGGA | CAGCATCTTTCATACAGATCATCAAA | TGTATATGGGTTTAAGAAGAAG | CA050178 | 0.88 | 0.95 | 0.82 | ||||

| Ubiqitin-like protein-1, Peroxisomal membrane protein 2 | UBL1_MGL_2 | PXMP2 | CPS301, Krasnov | GGCCTGCATTCAGGATCTAA | TACAGTCTCACCAGGCACCA | AGTGATGGTGCTGATTACGGAGCC | CB499972 | 0.61 | 0.95 | 0.91 | 0.94 | 0.63 | 0.89 |

| Ubl carboxyl-terminal hydrolase 18 | USP18_MGL_2 | USP18 | CPS301 | TTCCAGCTAACCTGCCGTACA | CAGTACAGTTTGTGTGCAGTCATAGTG | TATGCTGTGTAGTGTCCAAA | CA056962 | 0.96 | 0.88 | 0.82 | 0.95 | 0.74 | 0.93 |

| VHSV-inducible protein-1 | VHSVIP1_MGL_3 | VIG1 | Krasnov-not 16K | TGGCTTCCCACATTGCAA | CCTCCTCCCCCCTGCAT | AGATGGAGACAGGAATG | AF483546 | 0.63 | 0.83 | 0.85 | 0.87 | ||

| VHSV-inducible protein-4 | VHSVIP4_MGL_3 | VIG4 | Krasnov | GCTCTCGTAAAGCCCCACATC | GGGCGACTGCTCTCTGATCT | AAACTGCACGTCGCGC | GO053979 | 0.93 | 0.66 | 0.6 | 0.87 | ||

| VHSV-induced protein-10 mRNA | VHSV-P10_MGL_2 | VIG10 | CPS301 | GCAAACTGAGAAAACCATCAAGAA | CCGTCAGCTCCCTCTGCAT | TGTGGAGAAGTTGCAGGC | CA040505 | 0.79 | 0.87 | 0.83 | 0.93 | 0.87 | 0.91 |

| Very large inducible GTPase 1-1 | VLIG1-1_MGL_2 | GVINP1 | Krasnov | CAACAGAGGCCTCAGCAATG | TCTGGCCTCTCCCTGAACTG | ATCACTCCTGGACATGAA | EG841455 | 0.96 | 0.92 | 1.03 | 1.07 | ||

| XIAP-associated factor-1 | XAF1_MGL_1 | XAF1 | Krasnov-not 16K | CGTAGCTACTGGTTTTGGAATCAG | CAGGTTGTGTCCTCTTCCTTGTC | ATTGACAGGTTTCCGCG | BT049703 | 0.86 | |||||

| XAF1_MGL_2 | XAF1 | Krasnov-not 16K | TGCGGACGCTACATCACTCT | TTGAGGTCAGGGCAGATCTGA | ACCAGCCAGAGCAT | BT049703 | 0.9 | 0.89 | |||||

| PR domain zinc finger protein 9 | ZFP9_MGL_2 | ZFP9 | Krasnov | CGGCTATAAAAAGCCAACTCACA | ACAGTGGTTATAGAGGGTGCAACA | TTATCCCTGAGGTGCTGAC | DQ246664 | 0.86 | 1.08 | 1.07 | 0.93 | ||

| Description | Assay name | Gene ID | Biomarker origin | F sequence | R sequence | Probe sequence | EST |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Housekeeping genes | |||||||

| S100 calcium binding protein | 78d16.1 | 78d16.1 | Microarray studies | GTCAAGACTGGAGGCTCAGAG | GATCAAGCCCCAGAAGTGTTTG | AAGGTGATTCCCTCGCCGTCCGA | CA056739 |

| Coiled-coil domain-containing protein 84 | Coil-P84 | Coil-P84 | Microarray studies | GCTCATTTGAGGAGAAGGAGGATG | CTGGCGATGCTGTTCCTGAG | TTATCAAGCAGCAAGCC | CA053789 |

| 39S ribosomal protein L40, mitochondrial precursor | MrpL40 | MrpL40 | Microarray studies | CCCAGTATGAGGCACCTGAAGG | GTTAATGCTGCCACCCTCTCAC | ACAACAACATCACCA | CK991258 |

| Infectious agents | |||||||

| Candidatus Branchiomonas cysticola | Bacterium | c_b_cys | Infectious agent | AATACATCGGAACGTGTCTAGTG | GCCATCAGCCGCTCATGTG | CTCGGTCCCAGGCTTTCCTCTCCCA | JQ723599 |

| Flavobacterium psychrophilum | Bacterium | fl_psy | Infectious agent | GATCCTTATTCTCACAGTACCGTCAA | TGTAAACTGCTTTTGCACAGGAA | AAACACTCGGTCGTGACC | |

| Piscichlamydia salmonis | Bacterium | pch_sal | Infectious agent | TCACCCCCAGGCTGCTT | GAATTCCATTTCCCCCTCTTG | CAAAACTGCTAGACTAGAGT | EU326495 |

| Renibacterium salmoninarum | Bacterium | re_sal | Infectious agent | CAACAGGGTGGTTATTCTGCTTTC | CTATAAGAGCCACCAGCTGCAA | CTCCAGCGCCGCAGGAGGAC | AF123890 |

| Rickettsia-like organism | Bacterium | rlo | Infectious agent | GGCTCAACCCAAGAACTGCTT | GTGCAACAGCGTCAGTGACT | CCCAGATAACCGCCTTCGCCTCCG | EU555284 |

| Moritella viscosa | Bacterium | mo_visa | Infectious agent | CGTTGCGAATGCAGAGGT | AGGCATTGCTTGCTGGTTA | TGCAGGCAAGCCAACTTCGACA | EU332345 |

| Tenacibaculum maritimum | Bacterium | te_mara | Infectious agent | TGCCTTCTACAGAGGGATAGCC | CTATCGTTGCCATGGTAAGCCG | CACTTTGGAATGGCATCG | NBRC15946T |

| Yersinia ruckeri | Bacterium | ye_ruca | Infectious agent | TCCAGCACCAAATACGAAGG | ACATGGCAGAACGCAGAT | AAGGCGGTTACTTCCCGGTTCCC | AY333067 |

| Ceratomyxa shasta | Parasite | ce_sha | Infectious agent | CCAGCTTGAGATTAGCTCGGTAA | CCCCGGAACCCGAAAG | CGAGCCAAGTTGGTCTCTCCGTGAAAAC | AF001579 |

| Cryptobia salmositica | Parasite | cr_sal | Infectious agent | TCAGTGCCTTTCAGGACATC | GAGGCATCCACTCCAATAGAC | AGGAGGACATGGCAGCCTTTGTAT | |

| Dermocystidium salmonis | Parasite | de_sal | Infectious agent | CAGCCAATCCTTTCGCTTCT | GACGGACGCACACCACAGT | AAGCGGCGTGTGCC | U21337 |

| Ichthyophonus hoferi | Parasite | ic_hof | Infectious agent | GTCTGTACTGGTACGGCAGTTTC | TCCCGAACTCAGTAGACACTCAA | TAAGAGCACCCACTGCCTTCGAGAAGA | AF467793 |

| Ichthyophthirius multifiliis | Parasite | ic_mul | Infectious agent | AAATGGGCATACGTTTGCAAA | AACCTGCCTGAAACACTCTAATTTTT | ACTCGGCCTTCACTGGTTCGACTTGG | IMU17354 |

| Loma salmonae | Parasite | lo_sal | Infectious agent | GGAGTCGCAGCGAAGATAGC | CTTTTCCTCCCTTTACTCATATGCTT | TGCCTGAAATCACGAGAGTGAGACTACCC | HM626243 |

| Myxobolus arcticus | Parasite | my_arc | Infectious agent | TGGTAGATACTGAATATCCGGGTTT | AACTGCGCGGTCAAAGTTG | CGTTGATTGTGAGGTTGG | HQ113227 |

| Parvicapsula kabatai | Parasite | pa_kab | Infectious agent | CGACCATCTGCACGGTACTG | ACACCACAACTCTGCCTTCCA | CTTCGGGTAGGTCCGG | DQ515821 |

| Parvicapsula minibicornis | Parasite | pa_min | Infectious agent | AATAGTTGTTTGTCGTGCACTCTGT | CCGATAGGCTATCCAGTACCTAGTAAG | TGTCCACCTAGTAAGGC | AF201375 |

| Parvicapsula pseudobranchicola | Parasite | pa_pse | Infectious agent | CAGCTCCAGTAGTGTATTTCA | TTGAGCACTCTGCTTTATTCAA | CGTATTGCTGTCTTTGACATGCAGT | AY308481 |

| Sphaerothecum destructuens | Parasite | sp_des | Infectious agent | GGGTATCCTTCCTCTCGAAATTG | CCCAAACTCGACGCACACT | CGTGTGCGCTTAAT | AY267346 |

| Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae | Parasite | te_bry | Infectious agent | GCGAGATTTGTTGCATTTAAAAAG | GCACATGCAGTGTCCAATCG | CAAAATTGTGGAACCGTCCGACTACGA | AF190669 |

| Infectious hematopoietic necrosis virus | Virus | ihnv | Infectious agent | AGAGCCAAGGCACTGTGCG | TTCTTTGCGGCTTGGTTGA | TGAGACTGAGCGGGACA | NC_001 652 |

| Pacific salmon parvovirus | Virus | pspv | Infectious agent | CCCTCAGGCTCCGATTTTTAT | CGAAGACAACATGGAGGTGACA | CAATTGGAGGCAACTGTA | |

| Piscine orthoreovirus | Virus | prv | Infectious agent | TGCTAACACTCCAGGAGTCATTG | TGAATCCGCTGCAGATGAGTA | CGCCGGTAGCTCT | |

| Viral encephalopathy and retinopathy virus | Virus | ver | Infectious agent | TTCCAGCGATACGCTGTTGA | CACCGCCCGTGTTTGC | AAATTCAGCCAATGTGCCCC | AJ245641 |

| Erythrocytic necrosis virus | Virus | env | Infectious agent | CGTAGGGCCCCAATAGTTTCT | GGAGGAAATGCAGACAAGATTTG | TCTTGCCGTTATTTCCAGCACCCG | |

| Viral hemorrhagic septicemia virus | Virus | vhsv | Infectious agent | AAACTCGCAGGATGTGTGCGTCC | TCTGCGATCTCAGTCAGGATGAA | TAGAGGGCCTTGGTGATCTTCTG | Z93412 |

aFarm audits.

Application of VDD biomarker TaqMan assays to validate their predictive capacity

TaqMan assays to 45 VDD biomarkers (four with multiple assays required across species) were applied on the Fluidigm BioMarkTM HD microfluidics qPCR platform along with TaqMan assays to 23 infectious agents previously detected in a subset of the samples to be tested using the BioMark salmon infectious agent monitoring system outlined in Miller et al. (2016). Quantitative infectious agent monitoring for most studies included 5 bacteria, 6 viruses and 12 parasites known or suspected to cause disease in salmon (Table 2). For the audit samples, 50 assays to 49 infectious agents were applied, including all agents outlined in Miller et al. (2016) plus three additional pathogenic bacteria known to cause disease on salmon farms: Moritella viscosa, Tenacibaculum maritimum and Yersinia ruckeri (assays in Table 2). These panels were applied to the (i) multi-species IHNv challenge trials to assess performance across species and tissues; (ii) jaundice/anemia Chinook salmon farm outbreak, including multiple tissues to validate performance of the VDD panel on a novel disease hypothesized to be virally induced; (iii) farm audit samples to assess the ability of the VDD panel to differentiate viral versus bacterial or parasitic diseases; and (iv) wild migrating sockeye salmon smolts to discern whether the VDD panel could identify the presence of a viral disease state associated with IHNv infection from non-destructive gill biopsy samples of wild salmon (Jeffries et al., 2014) (experimental designs outlined in Table 1; schematic in Fig. 1).

Quantitative PCR on the Fluidigm BioMarkTM HD platform

Methods for application of TaqMan assays to both host genes and infectious agents have been previously described in Miller et al. (2014) and Jeffries et al. (2014). Briefly, nucleic acid extractions were performed on homogenizations using Tri-reagentTM using the Magmax™-96 for Microarrays RNA kit (Ambion Inc, Austin, TX, USA) with a Biomek NXPTM (Beckman-Coulter, Mississauga, ON, Canada) automated liquid-handling instrument. RNA was quantitated and normalized to 62.5 ng/μl with a Biomek NXP (Beckman-Coulter, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) automated liquid-handling instrument. RNA (1μg) was reverse transcribed into cDNA using the superscript VILO master mix kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The cDNA was then used as template for Specific Target Amplification (STA) to enrich for targeted sequences and increase the sensitivity of the microfluidics platform. The 5 μl STA reaction contained 1.3 μl of cDNA/DNA, 1x TaqMan PreAmp master mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and 0.2 μM of each of the primers (45 VDD host genes and 3 housekeeping genes run as singletons, 12 infectious agents run in duplicate; Table 2). The 14-cycle STA program followed manufacturer's instructions (Fluidigm Corporation, South San Francisco, CA, USA). Upon completion of the STA, excess primers were removed by treating with Exo-SAP-ITTM (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA) according to manufacturer's instructions and then diluted 1/5 in DNA re-suspension buffer (Teknova, Hollister, CA, USA).

The 96.96 gene expression dynamic array (Fluidigm Corporation, CA, USA) contained TaqMan assays to both host genes and select infectious agent assays (Table 2) and generally followed Miller et al (2016). A 5-μL reaction mix [2x TaqMan Mastermix (Life Technologies), 20x GE Sample Loading Reagent, nuclease-free water and 2.7 μL of amplified cDNA] was added to each assay inlet of the array following manufacturer's recommendations. After loading the assays and samples into the chip by an IFC controller HX (Fluidigm), PCR was performed under the following cycling conditions: 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. Gene expression data were preprocessed using GenEx (www.multid.se). Host biomarkers were normalized to the three reference genes, and relative gene expression was assessed using the 2−ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). A pooled sample was used as the relative control.

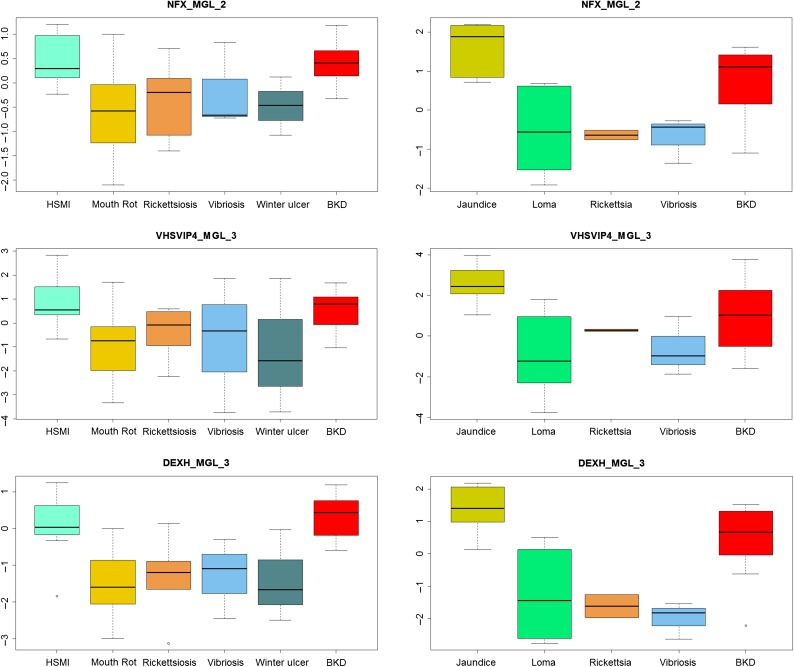

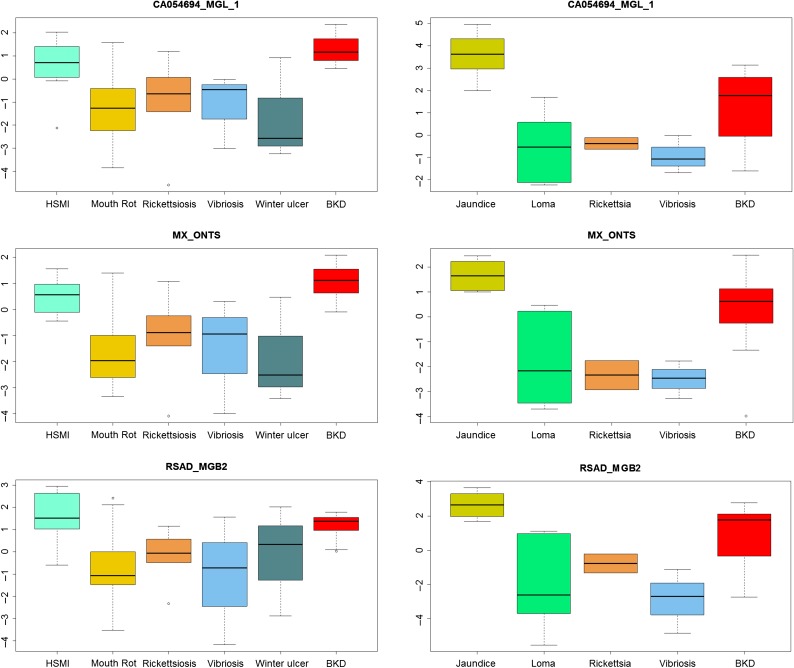

Validation of proposed VDD panels

The discrimination capabilities of the resultant proposed VDD 45 biomarker panel were validated in independent fish from the jaundice syndrome, farm audit and wild salmon studies, and in samples from the IHNv challenge study that represented a mix of those previously used discovery analysis (13%) and new samples from waterborne experiments and additional tissues. For each dataset, the discriminatory capabilities of the full VDD biomarker panel was assessed using unsupervised PCA analysis and hierarchical clustering (heatmaps) based on Euclidean distance metric and complete linkage, with gene shaving (described above) applied to identify whether a reduced set of biomarkers carried similar discriminatory capabilities. To assess the contribution of individual biomarkers to discriminatory capabilities, two-sample t-tests between ‘viral diseased’ and either ‘healthy controls’ or ‘bacterial/parasitic diseased’ samples were used as implemented in the t.test-function in R's stats package (R version 3.3.1). Unequal variances were assumed and a Welch approximation to the degrees of freedom was used in the t-test. No multiple test correction was applied but a more stringent P-value threshold of 0.01 was used instead when assigning significance. Boxplots were generated to visually assess the degree and direction of differential expression between viral, bacterial and parasitic disease sample groups, with rectangles (boxes) representing the interquartile range (IQR) from the first quartile (the 25th percentile) to the third quartile (the 75th percentile) of the data. Whiskers extend from the box to the minimum and maximum value unless the distance from the minimum value to the first quartile is more than 1.5 times the IQR. In that case, the whisker extends out to the smallest value within 1.5 times the IQR from the first quartile and values outside the whisker are drawn as open circles. A similar rule is used for values larger than 1.5 times IQR from the third quartile (Krywinski and Altman, 2014). A final set of heatmaps based on all biomarkers applied across studies was generated to illustrate that VDD biomarkers were consistently up-regulated in fish in a viral disease state across studies. For each heatmap, samples were manually grouped into ‘healthy controls’, ‘viral diseased’ or ‘bacterial/parasitic diseased.’ For the farmed audit study, within-group samples were ordered by mean value over all biomarkers while for the IHNv validation data, non-control samples were ordered by day post-challenge. Genes were re-ordered among studies to highlight at the top the genes with the most consistent contribution.

Statistical analysis was performed with R version 3.2.1 (discovery) and 3.3.1 (validation) (R Core Team, 2016).

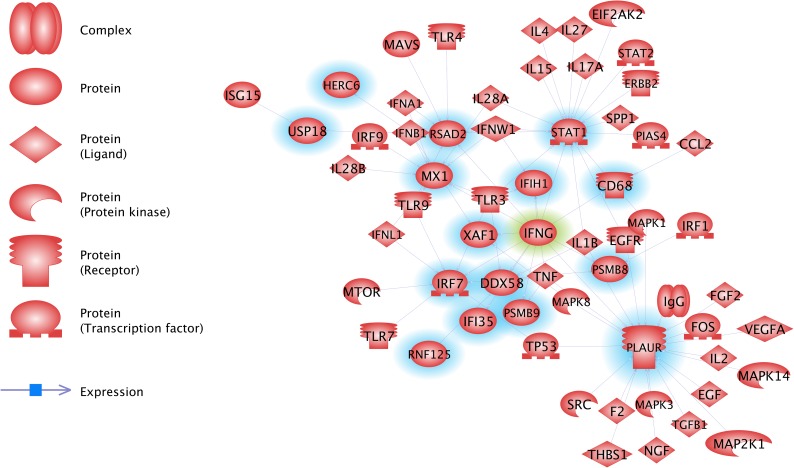

Functional analysis of the VDD

Pathway StudioTM (Elsevier, Amsterdam) was used to carry out functional analysis of the proposed VDD panel. VDD biomarker genes that could be annotated to mammalian genes were used in analyses to identify the most significant transcriptional regulator, over-represented biological and disease-related processes, and to develop a disease network, linking genes by their common regulators and closest neighbors.

Results

Microarray validation of discovery panels—candidate biomarker signatures

Of the 25 VRG SIQ features of Krasnov et al. (2011), 16 could be mapped to 71 unique GRASP16K features (using a gene name mapping approach based on a GRASP16 GPL annotation file). Fifteen of the remaining VRG features, not explored in our microarray analyses, were assessed via qRT-PCR.

Meta-analysis of signature CS0301u, a 532 feature panel derived from published microarray challenge studies for ISAv, IPNv, PMCv, PRv and IHNv, was conducted on in-house IHNv microarray studies across Atlantic, Sockeye and Chum salmon, yielding five signature panels (PBP016, PBP018, PBP19, PBP020 and PBP021) (Table S1). There are 54 features (some including gene paralogs) in the union of the five panels, including 15-feature panel PBP022 and 19-feature panel PBP024 which represent subsets of the Purcell et al. (2011) published signature, that were able to separate controls from exposed samples in MGL IHNv-challenged Sockeye and Atlantic salmon data. Visual inspection of boxplots for the 54 features in Atlantic, Sockeye, and Chum salmon, and Rainbow trout IHNv datasets, and selection of features that showed consistent behavior across species (maintained increase or decrease in expression after exposure), resulted in the selection of a subset of 38 features that define signature CPS301 (Table S2).

Signature CPS301 includes eight features and five genes from the VRG-signature in Krasnov et al. (2011): FRK (aka SRK2), IFIT5, RSAD2 (two features), CD9 (two features CD9 and two features Gig2-L), VIG10 (Table S1). In total, 6 of the 38 features in CPS301 were only found in the Rainbow trout and Chum data but they displayed strong differences in expression between controls and exposed samples in both species: Cox4nb, Zinc−binding protein A33, STAT1, unknown protein [Siniperca chuatsi] (CA038063), PRK12678 transcription termination factor Rho and RNF213.

All 38 features of CPS301 showed an increase of expression after exposure across species. Several of the features suggested transient increase of expression in Chum salmon, the species least susceptible to IHN, while increased expression was maintained in the other species for which there was data after pre-processing. IRF7 showed transient increase in expression in Atlantic salmon but a maintained increase in Chum salmon.

Two of the 38 features in CPS301 map to GIG2L (aka CD9), and in addition to being identified in Krasnov et al. (2011), they also show a clear change in expression in ISAv versus control samples in the LeBlanc et al. (2010) dataset, and in IHNv versus control samples in the Purcell et al. (2011) dataset (Table S1). Two additional features were found in the CPS301 signature and in the ISAv dataset: PLAUR and Slime mold cyclic AMP receptor, both being included in CPS301 as their expression suggested an involvement in a response to IHNv and ISAv-infection.

Additional features from Krasnov that could not be mapped to the GRASP arrays or that were often removed from testing due to data quality issues were added to the VDD validation panel, including DDX58 (two features; aka RIG1), BANF1, GVINP1, HERC4, IFI, IFIH1 (aka MDA5), IFI44 (two features), NFX1, RAD1, RTP3, SACS, VIG1, VIG4, XAF1 and ZFP9 (Table S2).

VDD biomarker validation studies

The Fluidigm BioMark platform was used to validate 51 assays across 45 candidate VDD biomarker genes (including gene homologs). Note that not all assays showed high efficiency across all species; hence, for each species, we report only the assays with efficiencies between 0.85 and 1.1.

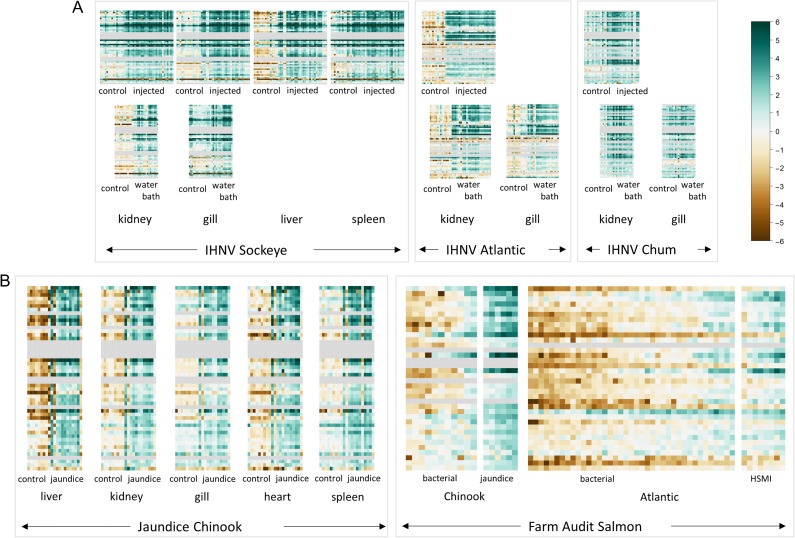

IHNv challenges

VDD biomarkers were applied to 604 samples from IHNv challenge studies that included three salmon species (Atlantic, Sockeye and Chum), two types of challenges (ip injection and cohabitation) and multiple tissues (head kidney, gill, liver, spleen) sampled (Table 1A). Although at the outset of these experimental challenges fish were considered disease free, assays to 23 infectious agents applied simultaneous to the VDD biomarkers revealed a range of infectious agents detected across species, albeit most at low levels. The presence of these additional (bacterial and microparasite) infectious agents enabled the assessment of their impact on the resolution of fish with IHN, which was found to be minimal.

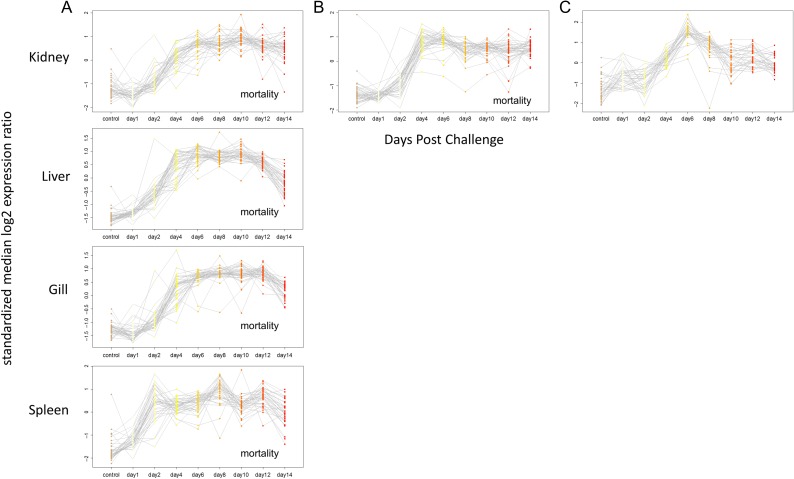

Sockeye salmon challenges included 275 samples assessed for VDD and infectious agents distributed across four tissues (head kidney, gill, liver and spleen) in the ip challenge and two tissues (head kidney and gill) in the waterborne challenge (Table 1A). Co-infections were extremely rare, affecting <7% of fish, none other than IHNv with loads exceeding 100 copies per μl. Microsporidian parasite Paranucleospora theridion was the only co-infecting agent affecting more than 5% of fish. Mortality reached 44% over the 30-day course of the ip challenge, starting on Day 9 and reaching 20% by Day 14, the last fish sample date. Transcriptional profiles of all IHNv positive fish against uninfected controls at Day 0 were averaged for each day post-infection. In every tissue across 38 of the 39 VDD biomarkers with good efficiencies in Sockeye salmon, a pattern of transcriptional up-regulation of ip challenged fish by Day 4 separated the IHN diseased fish with controls and early stage infections in all four tissues (kidney, liver, spleen, gill; Fig. 2A; Table 3). ZPF1 was the exception. Most biomarkers remained highly up-regulated through Day 12, many beginning to diminish by Day 14. A similar pattern was apparent in kidney and gill tissues from waterborne challenged fish that became infected with IHNv (Fig. 3A), although there was enhanced variability in gill tissue. While generally up-regulated, GNL3, VLIG, IFI35, CD68, CD9 (GIG2-1_MGB1 assay), PSMB8 and Trim21 showed enhanced variability over the time-course in some tissues (Table 3).

Figure 2:

Time-course of expression of VDD genes post IHNv ip challenge, by tissue. (A) Sockeye, (B) Atlantic and (C) Chum salmon. Only samples from IHNv infected fish are included in the displayed post controls time course data. For Sockeye this included all 45 samples, while one Day 1 sample was excluded in the Atlantic salmon time course, and 11 samples from different time points were excluded in the Chum salmon time course.

Table 3:

Differential regulation of individual biomarkers within the VDD panel in response to IHNv challenges, by species, jaundice/anemia in Chinook salmon, and diseases on salmon farms. In IHNv and jaundice studies, ‘Up’ refers to up-regulation of biomarkers in IHN diseased versus control or early infection salmon and ‘Variable’ refers to biomarkers that do not show continuous up-regulation post-challenge. GS-VDD refers to biomarkers that were identified via gene shaving. Differential regulation in the farm audit studies in Atlantic and Chinook salmon was determined by expression box plots (top 11 presented in Figure 7). Biomarkers were ranked by overall discrimination capabilities with those classified as ‘Top’ performing consistently across all studies, ‘Good’ showing strong classification ability in most studies, ‘Limited V-B’ showing limitations in classifications between viral and bacterial diseases (not including bacterial kidney disease), and ‘Viral-Healthy’ only showing classification between viral-mediated diseased and healthy individuals

| IHNv challenge studies | Jaundice | Audit | Audit | Overall | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene name | Assay name | Derived | Gene network | Gene ID | Sockeye | Atlantic | Chum | Chinook | Atlantic box | Chinook box | Atlantic | Chinook | |

| Ubiqitin-like protein-1, Peroxisomal membrane protein 2 | UBL1_MGL_2 | CPS301, Krasnov | PXMP2 | Up | Up | Up Days 6–8 | Up—GS-VDD_7 | Excellent | Excellent*bkd | GS-VDD_9 | GS-VDD_11 | Top Overall and V-BKDChinook | |

| Interferon-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 5 | IFIT5_MGL_2 | CPS301, Krasnov | Yes | IFIT5 | Up | Up | Up | Up | Excellent | Excellent | GS-VDD_15 | Top | |

| Galectin-3-binding protein precursor | GAL3_MGL_2 | CPS301 | LGALS3BP | Up | Up | Up | Up | Excellent | Excellent*bkd | GS-VDD_11 | Top | ||

| Zinc finger NFX1-type | NFX_MGL_2 | Krasnov | NFX1type | Up | Up | Variable | Up | Excellent | Excellent | Top | |||

| VHSV-inducible protein-4 | VHSVIP4_MGL_3 | Krasnov | VIG4 | Up | Up | Up Days 6–8 | Up | Excellent | Excellent | GS-VDD_9 | GS-VDD_9 | Top | |

| ATP-dependent RNA helicase | DEXH_MGL_3 | Krasnov-not 16K | Yes | DDX58 | Up | Excellent | Excellent*loma | Top | |||||

| Interferon-induced GTP-binding protein Mx | MX | in house | Yes | MX1 | Up | Up | Up | Up—GS-VDD_7 | Excellent | Excellent | GS-VDD_9 | GS-VDD_11 | Top |

| Radical S-adenosyl methionine domain-containing protein 2 | RSAD_MGB2 | CPS301, Krasnov | Yes | RSAD2 | Up | Up | Up | Up | Excellent | Excellent | GS-VDD_9 | GS-VDD_9 | Top |

| Mitochondrial ribosomal protein (VAR1) | CA054694_MGL_1 | CPS301 | VAR1 | Up | Up | Up | Good | Excellent | GS-VDD_9 | Top | |||

| IFN-induced protein 44-1 | IFI44A_MGL_2 | Krasnov-not 16K | IFI44 | Up | Up | Up | Good | Excellent*bkd | GS-VDD_15 | Top and BKDChinook | |||

| Probable E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase HERC6 | HERC6_1 | CPS301 | Yes | HERC6 | Up | Up | Up | Up—GS-VDD_7 | Good | Excellent*loma | GS-VDD_15 | Top | |

| 52 kDa Ro protein-2—52Ro | 52RO_MGL_3 | Krasnov | Yes | TRIM21 | Variable | Up | Up | NA | Excellent | GS-VDD_9 | Top Pacific | ||

| IFN-induced protein | IFI_MGB2 | Krasnov | Up | early, Variable | Up Days 4–8 | Up | NA | Excellent | GS-VDD_11 | Top Pacific | |||

| CD9 molecule | GIG2-1_MGB3 | CPS301, Krasnov | Yes | CD9 | Up | Excellent | NA | GS-VDD_9 | Top Atlantic | ||||

| Retinoic acid-inducible gene-1 | RAD_MGL_2 | Krasnov | RAD1 | Up | Excellent | NA | Top Atlantic | ||||||

| Sacsin | SAC_MGB2 | Krasnov | SACS | Up | Excellent | NA | GS-VDD_9 | Top Atlantic | |||||

| XIAP-associated factor-1 | XAF1_MGL_1 | Krasnov-not 16K | Yes | XAF1 | Up | Excellent | NA | Top Atlantic | |||||

| Receptor-transporting protein 3 | RTP3_MGL_1 | Krasnov | RTP3 | Up | Excellent | Good | GS-VDD_9 | Good | |||||

| Signal transducer and activator of transcription 1-alpha/beta | STAT1 | CPS301 | Yes | STAT1 | Up | Down early | Up Days 4–8 | Up | Good | Poor | GS-VDD_9 | Good | |

| Tyrosine-protein kinase FRK | SRK2_MGB3 | CPS301, Krasnov | FRK | Up | Up | Good | Good | GS-VDD_11 | Good | ||||

| Oncorhynchus mykiss VHSV-induced protein-10 | VHSV-P10_MGL_2 | CPS301 | VIG10 | Up | Up | Up Days 4–8 | Up—GS-VDD_7 | Good | Poor | GS-VDD_11 | Good | ||

| ATP-dependent RNA helicase | DEXH_MGL_1 | Krasnov-not 16K | Yes | DDX58 | Up | Up | Up | NA | NA | Good | |||

| RNA helicase—RIG-I | RIG1_MGLSYBR_1 | Krasnov | Yes | DDX58 | Up | Up | Up | Up—GS-VDD_7 | Excellent | Good*loma | Good | ||

| Very large inducible GTPase 1-1 | VLIG1-1_MGL_2 | Krasnov | GVINP1 | Variable | Up early | Variable | Up | Poor | Good*loma | Good | |||

| Similar to KIAA1593 | KIAA_MGL_1 | Krasnov-not 16K | HERC4 | Up | Up Days 1–14 | Up | NA | NA | Good | ||||

| MHC class I antigen [Salmo salar] | UBA_MGL_CA050178_1 | CPS301 | MHC1 | Up | NA | NA | Good | ||||||

| MHC class I antigen [Salmo salar] | UBA_MGL_CA050178_4 | CPS301 | MHC1 | Up | NA | NA | Good | ||||||

| Ring finger protein 213 | E3RNF213_2 | CPS301 | RNF213 | Up | Up | Up Days 4–10 | Poor | Excellent*loma | Good | ||||

| Ring finger protein 213 | RNF213_MGL_5 | CPS301 | Yes | RNF213 | Up | Up | Up | Up | Good | Poor | Good | ||

| Sacsin | SAC_MGB1 | Krasnov | SACS | Up | Up | Excellent | NA | Good | |||||

| Ubl carboxyl-terminal hydrolase 18 | USP18_MGL_2 | CPS301 | Yes | USP18 | Up | Up | Up Days 4–8 | Up—GS-VDD_7 | Excellent | Good | Good | ||

| VHSV-inducible protein-1 | VHSVIP1_MGL_3 | Krasnov-not 16K | VIG1 | Down early | Up Days 4–8 | Up—GS-VDD_7 | NA | NA | Good | ||||

| XIAP-associated factor 1 | XAF1_MGL_2 | Krasnov-not 16K | Yes | XAF1 | Up | NA | NA | Good | |||||

| Barrier to autointegration factor | BAF_MGL_4 | Krasnov | BANF1 | Up | Good | NA | GS-VDD_9 | Good Atlantic | |||||

| CD9 molecule | GIG2-1_MGB2 | CPS301, Krasnov | Yes | CD9 | Up | Up | NA | NA | Good Pacific | ||||

| IFN-induced protein 44—IFI44 | IFI44C_MGL_3 | Krasnov | IFI44 | Up | Up | Up | Not Rickettsiosis | Excellent*bkd | GS-VDD_15 | Good | |||

| Urokinase plasminogen activator surface receptor precursor | PLAUR_MGL_3 | CPS301 | Yes | PLAUR | Up | Up | Up | Up | No Discrimination | Excellent | GS-VDD_15 | GS-VDD_9 | Limited V-BAtlantic |

| PLAC8-like protein 1 | PLAC8L1_MGL_1 | CPS301 | PLAC8L1 | Up | Up | Up | Up | Good | Poor | GS-VDD_9 | Limited V-BChinook | ||

| unknown protein [Siniperca chuatsi] | CA038063_MGL_1 | CPS301 | Up | Up (not gill) | No Discrimination | BKD not Loma | Limited V-B but Viral-BKDChinook | ||||||

| CD68 molecule | CD68_MGL_3 | CPS301 | Yes | CD68 | Variable | Up | Up | Up | Only Mouth Rot | Poor | Limited V-B | ||

| CD9 molecule | CD9_MGL_2 | CPS301, Krasnov | Yes | CD9 | Up | Up | Up | Up | Not Rickettsiosis | Good*loma | GS-VDD_9 | Limited V-B | |

| Slime mold cyclic AMP receptor | DICTY.CAR_MGL_2 | CPS301 | DICTY | Up | Up | Up Days 1–14 | Up | Only Vibriosis | Poor | GS-VDD_11 | Limited V-B | ||

| Interferon-induced 35 kDa protein homolog | IFI35_MGL_2 | CPS301 | IFI35 | Variable | Up | Up | Only Rickettsiosis | Poor | GS-VDD_9 | Limited V-B | |||

| Interferon induced with helicase C domain 1—IC | IFI-1C_MGL_2 | Krasnov | Yes | IFIH1 | Up | Up | Variable | Up | Poor | Poor | Limited V-B | ||

| Interferon regulatory factor 7 | IRF7_MGL_2 | CPS301 | Yes | IRF7 | Up | Up | Up | Up | Not Winter Ulcer | Good*loma | GS-VDD_15 | Limited V-B | |

| Guanine nucleotide-binding protein-like 3 | GNL3_MGL_1 | CPS301 | GNL3 | Variable | Up early, Variable | Variable | Up | No Discrimination | No Discrimination | GS-VDD_9 | Limited V-B | ||

| Proteasome subunit beta type-9 precursor | PSMB9A_MGL_2 | CPS301 | Yes | PSMB9 | Up | Down early | Up | Up | No Discrimination | Good | Limited V-B | ||

| similar to interferon-inducible protein Gig2 | GIG2-1_MGB1 | CPS301, Krasnov | Yes | CD9 | Variable | Poor | |||||||

| Fish virus induced TRIM-1 | TRIM1_MGB1 | Krasnov-not 16K | TRIM1 | Up | Variable | Variable | Up | Poor | Poor | Poor | |||

| Proteasome subunit beta type-8 precursor | PSMB8_1 | CPS301 | Yes | PSMB8 | Variable | not sig | Up (not gill) | Poor | Excellent*bkd | Poor but V-BKDChinook | |||

| PR domain zinc finger protein 9 | ZFP9_MGL_2 | Krasnov | ZFP9 | None | Down | None | None | NA | NA | Poor | |||

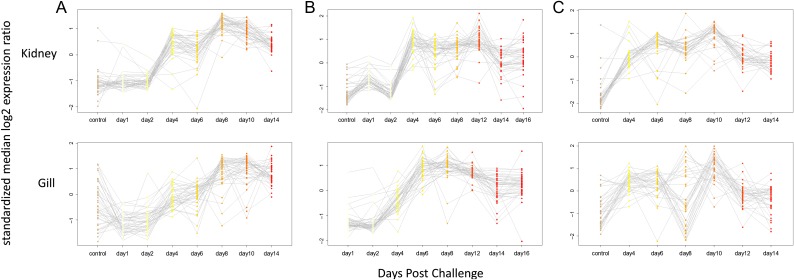

Figure 3:

Expression of VDD genes on a time-course post IHNv waterborne challenge, by tissue. (A) Sockeye salmon (B) Atlantic salmon (C) Chum salmon. Post controls time course samples represent IHNv infected fish only (26 for Sockeye, 37 for Atlantic and 18 for Chum salmon). Only time points with data for at least two samples are displayed.

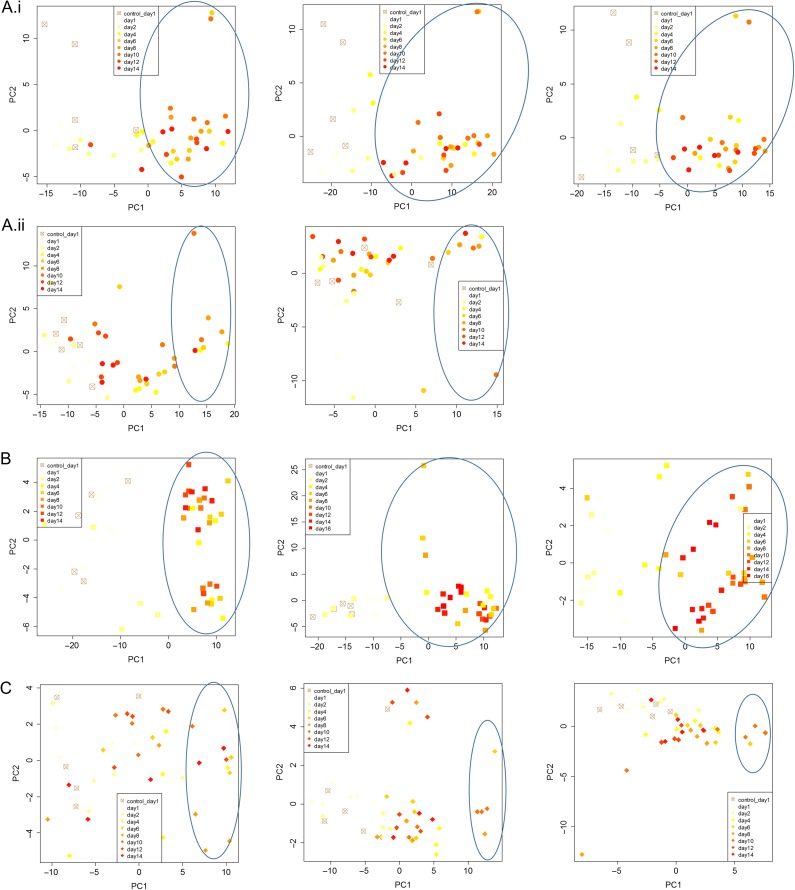

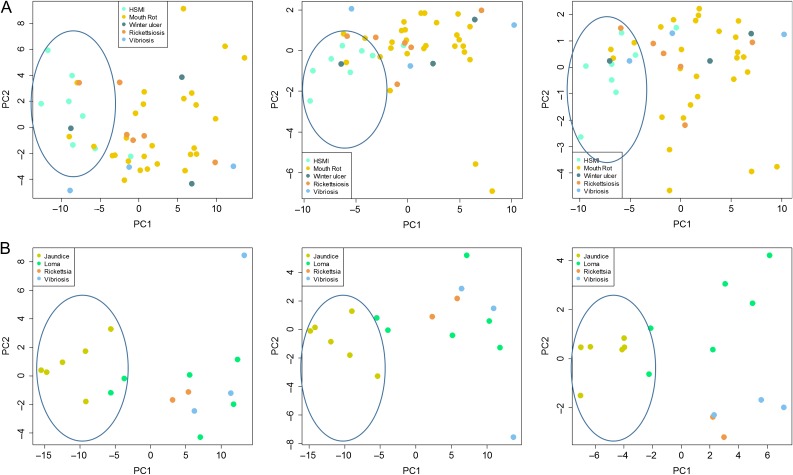

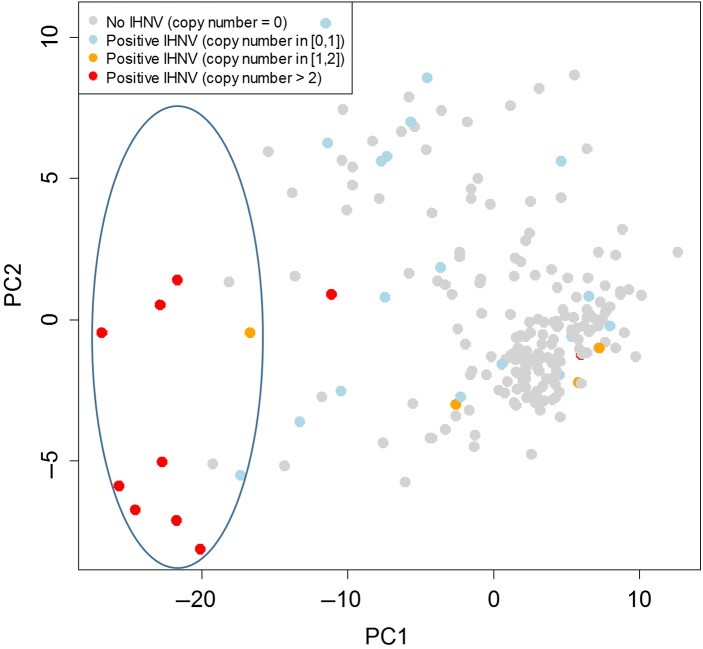

For the Sockeye salmon ip challenge, discrimination of fish with IHN was high from Day 4 onward (Fig. 4A(i)). IHNv abundance quickly elevated in the spleen, which also showed earlier development of the VDD, a few fish even on Days 1 and 2 post ip injection, however, the opposite pattern was observed later on. From Days 6 to 12, all but one fish was in a VDD state across tissues, the exception being a fish with very low IHNv detection on Day 12. IHNv loads and VDD strength diminished on Day 14, with head kidney the most impacted. In the waterborne challenge, only a small number of fish became infected in the head kidney, and stronger loads were generally detected in the gill. Only fish with detectable IHNv across gill and head kidney were in a VDD state across tissues; five fish with very low load detections across tissues did not classify as VDD, and one fish with moderate loads in gill and low loads in head kidney classified as VDD only in gill tissue (Fig. 4A(ii)). There were no measurable impacts of co-infective agents on discrimination of IHN fish in either challenge.

Figure 4:

PCA classification of salmon post IHNv challenge, by species, challenge-type and tissues, as visualized by principle component analysis. (A) Sockeye salmon: (i) ip-challenge by tissue (head kidney, liver, gill, respectively) and (ii) waterborne-challenge by tissue (head kidney, gill, respectively). (B) Atlantic salmon by challenge-type and tissue (ip: kidney, waterborne: head kidney, gill, respectively). (C) Chum salmon by challenge-type and tissue (ip: head kidney, waterborne: head kidney, gill, respectively).

Atlantic salmon challenges included 138 samples assessed using the VDD panel and infectious agents across two tissues (head kidney and gill) (Table 1A). Co-infecting agents affecting >5% of fish included P. theridion (25%) and Flavobacterium psychrophilum (6%). Mortality reached 100% over the 30-day course of the ip challenge, starting on Day 9 and reaching 75% by Day 14, the last fish sample date. Transcriptional up-regulation was synchronous among 40 of the 41 VDD biomarkers with good efficiencies in Atlantic salmon from Days 4 to 14, in both head kidney and gill tissues (Fig. 2B). VLIG1, GNL3 and IF1 were up-regulated earlier, starting on Day 2 (Table 3). ZPF9 was the only VDD biomarker that was down-regulated, also starting Day 4. TRIM1, although up-regulated, showed high variability post-challenge. These gene transcriptional patterns were highly consistent in the gills of waterborne challenged fish that became positive for IHNv, although most biomarkers peaked in transcription on Days 8–10 and then showed slight down-regulation on Days 14–16 (Fig. 3B), only a couple of which (PSMB9 and TRIM1) dropped to pre-exposure levels. In head kidney, GNL3 and IF1 showed higher variability, and three genes, PLAUR, PSMB9 and STAT1, were down-regulated on Days 14 and/or 16 (Table 3). ZFP9 was not consistently affected. Discrimination of fish with IHN was high from Day 4 onward (Fig. 4B).

Chum salmon challenges were conducted over 133 samples, including head kidney from an ip challenge and head kidney and gill from a waterborne challenge (Table 1A). In addition to the co-infective agents in Sockeye and Atlantic salmon, 63% of fish contained myxozoan parasite Parvicapsula pseudobranchicola, some at well over >100 copies per μl. Mortality of Chum salmon was <10% for each challenge study, and IHNv was detected in only 72% of ip-challenged fish and 38% of waterborne-challenged fish (across tissues), although only 18% in head kidney. Although IHNv copy number reached 105 in a few ip-challenged fish, individual levels varied dramatically from 101 to 104 on any given sample day, but were most consistent, with an average of 104, on Days 6–8. Transcriptional up-regulation in response to IHNv ip challenge of IHNv positive fish followed patterns of peak IHNv loads, generally occurring between Days 4–8 and involving fewer biomarkers than in Sockeye and Atlantic salmon (Fig. 2C). Of the 34 biomarkers assessed with good efficiencies in Chum salmon, 28 were consistently up-regulated in head kidney samples from the ip challenge, eight with limited duration (Table 3). HERC4 and DICTY were up-regulated earlier than other biomarkers, from Day 1 onward.

In the Chum salmon ip challenge, PCA analysis showed VDD clustering mostly contained to fish with IHNv loads >103 in head kidney, although a few fish on Days 2–4 with lower IHNv loads, and one with no IHNv detection in head kidney, were also within this cluster (Fig. 4C). In the waterborne challenge, IHNv was weakly detected in one fish on Day 1 in gill tissue, but was not detected until Day 6 in the head kidney, and even then, only in a single fish. Copy numbers of IHNv never reached more than 102 in gill, but reached 104 in the head kidney of one fish. IHNv was detected in head kidney in 40% of fish sampled on Days 6–10 and then dissipated. Transcriptional up-regulation of VDD biomarkers and VDD classification in gill and head kidney was restricted to fish with IHNv detections >103 in head kidney tissue (Fig. 4C); detections in gill alone did not elicit a substantive response. Similar genes as observed in the ip challenge were up-regulated.

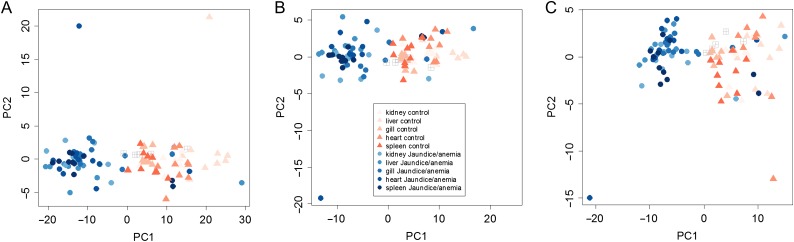

Jaundice syndrome

Jaundice syndrome (aka jaundice/anemia) is a disease causing low level mortality in farmed Pacific salmon with a suspected viral etiology, but that has not undergone extensive study. We explored the performance of the VDD biomarkers on fish undergoing natural farm outbreak of jaundice syndrome to further assess the likely viral etiology of the disease, and to quantitatively assess 45 salmon infectious agents for association with jaundice/anemia. Five tissues (liver and anterior kidney—the tissues showing most necrotic damage, heart, gill and spleen) were each assessed across 36 Chinook salmon, including diseased and healthy controls (Table 1B). Being a natural outbreak, there was a high rate of co-infection in these fish, with nine infectious agents detected, six at high loads in some individuals [up to 105 per μl—PRv (90% prevalence), Candidatus Branchiomonas cysticola (36%), P. theridion (64%), Loma salmonae (37%); 104 per μl—P. pseudobranchicola (20%), Renibacterium salmoninarum (32%)]. PRv was present at high load in virtually all jaundice fish, with control fish negative or containing only low loads. PRv was the only infectious agent statistically correlated, by presence and load, with the disease (R2: 0.76–0.84 among tissues).

There were 40 VDD biomarkers that amplified at high efficiency in Chinook salmon; all but ZFP9 and unknown CA068063 were up-regulated in jaundice fish relative to controls, regardless of co-infecting agents or tissue. PSMB9, IFI44 (assay IFI44A_MGL_2) and VSVP10 showed more variability in control fish (Table 3).

There was near perfect separation of jaundice from healthy fish based on the 40 VDD markers across liver, anterior kidney, heart and gill tissues (Fig. 5). The single outlier across all tissues was a fish with anemia (not jaundice) that had weak histopathological lesions consistent with jaundice syndrome but did not contain high loads of PRv; this fish clustered with the ‘healthy’ controls. A second sample with jaundice did not classify correctly in spleen tissue (Fig. 5B). Gene shaving applied to kidney and liver reducing the VDD panel down to 22 biomarkers, and then to seven, produced equivalent separation of groups (Fig. 5). The top seven features identified through gene shaving were PXMP2, HERC6, MX1, USP18, VIG1, DDX58 (RIG1) and VIG10.

Figure 5:

PCA classification of five tissues from farmed Chinook salmon undergoing an outbreak of jaundice/anemia. Analysis based on (A) a 40 biomarker VDD panel, (B) a 17 biomarker VDD panel identified through gene-shaving and (C) a 7 biomarker VDD panel derived from gene shaving. In each plot, samples with viral jaundice are shown in blue and healthy controls in peach, with shades and shapes within each depicting different tissues, as illustrated in the panel legend under (B). The single viral jaundice sample not properly classifying showed weak lesions and low viral loads, and is suspected to represent a fish in recovery.

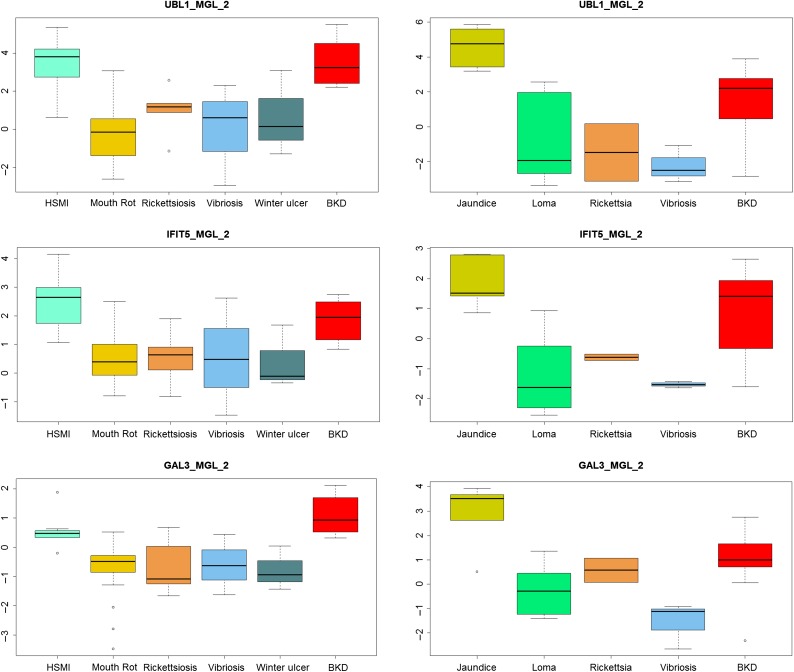

Farm audit samples

VDD biomarkers were tested on combined tissues of 240 moribund/recently dead farmed Atlantic salmon and 68 farmed Chinook salmon collected through a regulatory farm audit program (Table 1C). Because our previous two validations showed that the VDD panel had discriminatory capabilities across tissues, we reasoned that this panel may still work effectively in combined tissue samples. Histopathology and clinical data had been applied previously to diagnose known, well characterized diseases, and qRT-PCR data performed across 49 infectious agents were available to identify known pathogens and validate these diagnoses. The application of the VDD panel to the audit samples offered perhaps the most complex co-infection scenario imaginable as dying fish are likely the most vulnerable to opportunistic pathogens. Most samples contained mixed infections with 2–10 agents identified per individual. Only two viruses were commonly observed across samples, PRv (69%) and erythrocytic necrosis virus (ENv) (21%), a DNA virus that causes erythrocytic inclusion body syndrome (EIBS). Unfortunately we did not have the blood smears to diagnose EIBS, so this disease was left off of our differentials.