ABSTRACT

Histone H3.Y is conserved among primates. We previously reported that exogenously produced H3.Y accumulates around transcription start sites, suggesting that it may play a role in transcription regulation. The H3.Y nucleosome forms a relaxed chromatin conformation with flexible DNA ends. The H3.Y-specific Lys42 residue is partly responsible for enhancing the flexibility of the nucleosomal DNA. To our surprise, we found that H3.Y stably associates with chromatin and nucleosomes in vivo and in vitro. However, the H3.Y residues responsible for its stable nucleosome incorporation have not been identified yet. In the present study, we performed comprehensive mutational analyses of H3.Y, and determined that the H3.Y C-terminal region including amino acid residues 124–135 is responsible for its stable association with DNA. Among the H3.Y C-terminal residues, the H3.Y Met124 residue significantly contributed to the stable DNA association with the H3.Y-H4 tetramer. The H3.Y M124I mutation substantially reduced the H3.Y-H4 association in the nucleosome. In contrast, the H3.Y K42R mutation affected the nucleosome stability less, although it contributes to the flexible DNA ends of the nucleosome. Therefore, these H3.Y-specific residues, Lys42 and Met124, play different and specific roles in nucleosomal DNA relaxation and stable nucleosome formation, respectively, in chromatin.

KEYWORDS: chromatin, epigenetics, H3.Y, histone variant, nucleosome, thermal stability

Introduction

Nucleosomes are the basic repeating unit of eukaryotic chromatin, and are composed of histones H2A, H2B, H3, H4, and about 150 base pairs of DNA.1 The crystal structures of nucleosomes revealed that the DNA (145–147 base pairs) is left-handedly wound 1.65 turns around the surface of the histone octamer, containing 2 molcules each of H2A, H2B, H3, and H4.1 The structural versatility and stability of nucleosomes substantially affect the higher order chromatin configuration, and regulate genomic DNA function by changing the DNA accessibility within chromatin.2

The canonical histones are expressed during the S-phase of the cell cycle, and are incorporated into chromatin during the DNA replication process.3-5 In addition, histone variants, which are encoded on non-allelic loci of the canonical histone genes, have been identified for histones H2A, H2B, and H3.6 These histone variants are usually produced in cell-cycle independent, tissue-specific, and/or developmental stage-specific manners.7-11 These facts suggest that histone variants contribute to genomic DNA regulation for proper cell division and differentiation.12,13 Intriguingly, some of these histone variants have distinct biochemical, physical, and structural characteristics,14-38 which could affect the higher order chromatin conformation and regulate the functions of genomic DNA in the nucleus.

In humans, H3.3, H3T (H3.4), H3.5, H3.X, H3.Y, and CENP-A (CenH3) have been identified as non-allelic H3 variants6,39-44. H3.1 and H3.2 are canonical H3s expressed in S-phase cells.3-5 H3.3 and CENP-A are highly conserved H3 variants, present in yeasts to humans.4,11 H3T is a testis-specific histone variant and may be conserved in mammals, but not in amphibians and birds.11,41 In contrast, H3.5, H3.X, and H3.Y are only found in primates.43,44 H3.5 is another testis-specific histone variant, and the protein has been confirmed to exist in the human testis, but not in mature sperm.36,43 Interestingly, the nucleosomes containing H3T or H3.5 are quite unstable, as compared with those containing H3.1 or H3.3.24,36 Therefore, these unstable nucleosomes may play important roles during spermatogenesis in mammals. In contrast, we previously found that the H3.Y-H4 complex is incorporated into the nucleosome more tightly than the H3.3-H4 complex.38

We previously reported that exogenously produced H3.Y accumulates around transcription start sites, suggesting that it may play a role in transcription regulation.38 The H3.Y nucleosome forms a relaxed chromatin conformation by its flexible DNA ends.38 These characteristics of H3.Y may be important for its function, and the H3.Y-specific residues should be responsible for its unique properties. However, the H3.Y residue responsible for the nucleosome stability has not been identified yet, although the H3.Y Lys42 residue is partly involved in the DNA end flexibility of the nucleosome.38

In this Extra View article, we performed a comprehensive mutational analysis of the H3.Y nucleosome, and found that a mutation of the Met124 residue of H3.Y reduced the nucleosome stability, but the H3.Y Lys42 mutation did not affect it. Therefore, the Lys42 and Met124 residues have distinct functions in the formation and regulation of chromatin.

Results and discussion

The human histone H3.Y mutants

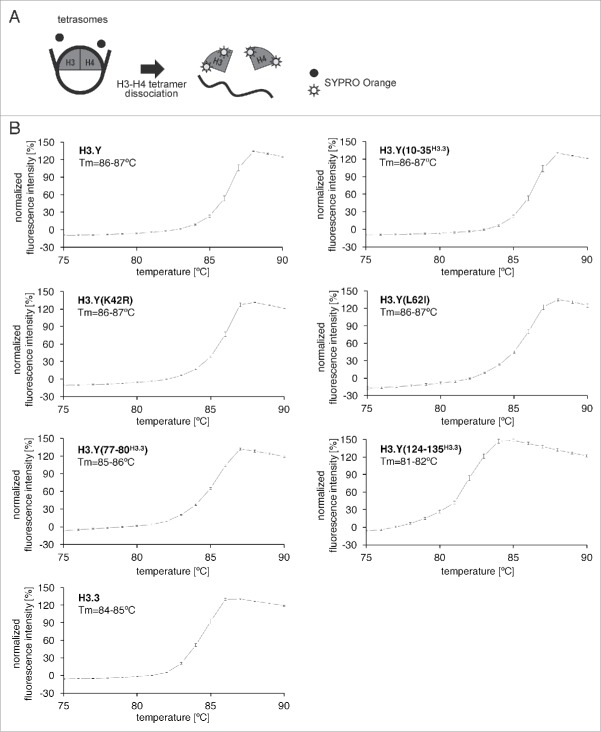

H3.Y is evolutionally derived from H3.3, and 26 amino acid differences exist between them (Fig. 1A). To study the roles of these H3.Y-specific amino acid residues, we purified 5 H3.Y mutants, H3.Y(10–35H3.3), H3.Y(K42R), H3.Y(L62I), H3.Y(77–80H3.3), and H3.Y(124–135H3.3). In the H3.Y(10–35H3.3), H3.Y(77–80H3.3), and H3.Y(124–135H3.3) mutants, the H3.Y residues 10–35, 77–80, and 124–135 were replaced by the corresponding H3.3 residues, respectively. In the H3.Y(K42R) and H3.Y(L62I) mutants, the H3.Y Lys42 and Leu62 residues were replaced by the corresponding H3.3 Arg and Ile residues, respectively. These H3.Y mutants were purified as bacterially produced recombinant proteins (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Preparation of tetrasomes containing H3.Y mutants. (A) Sequence alignment of human H3.Y and H3.3. The H3.Y- and H3.3-specific residues are marked by rectangles. (B) Purification of the H3.Y(10–35H3.3), H3.Y(K42R), H3.Y(L62I), H3.Y(77–80H3.3), and H3.Y(124–135H3.3) mutants. Purified H3.Y mutants were analyzed by 16% SDS-PAGE with Coomassie brilliant blue staining. (C) The reconstituted tetrasomes containing the H3.Y(10–35H3.3), H3.Y(K42R), H3.Y(L62I), H3.Y(77–80H3.3), and H3.Y(124–135H3.3) mutants were purified by non-denaturing PAGE, and were analyzed by 16% SDS-PAGE with Coomassie brilliant blue staining.

Tetrasome formation by the human histone H3.Y mutants

The tetrasome is the H3-H4-DNA complex, in which the DNA is wrapped around the H3-H4 tetramer without the H2A-H2B dimers.45 The mature nucleosome is assembled by the incorporation of H2A-H2B into the tetrasome.46,47 Therefore, the tetrasome is more favorable than the nucleosome to test the DNA association with the H3-H4 tetramer. We reconstituted tetrasomes with the H3.Y mutants by the salt dialysis method. The reconstituted tetrasomes were then purified by non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, using a Prep Cell apparatus (Bio-Rad), and the incorporation of the H3.Y mutants was tested. We found that all of the H3.Y mutants, as well as wild-type H3.Y and H3.3, were efficiently incorporated into tetrasomes with H4 (Fig. 1C).

Thermal stability of tetrasomes containing the H3.Y mutants

Our previous study revealed that the H3.Y-H4 tetramer forms a more stable tetrasome than the H3.3-H4 tetramer.38 We performed a thermal stability assay with the tetrasomes containing H3.Y mutants. In this assay, the H3.Y and H4 proteins that thermally dissociated from the tetrasomes were detected by SYPRO Orange, which emits fluorescence when it hydrophobically binds to thermally denatured H3.Y and H4 (Fig. 2A). As previously reported, the wild-type H3.Y tetrasome (Tm = 86–87°C) was thermally more stable than the wild-type H3.3 tetrasome (Tm = 84–85°C) (Fig. 2B). As shown in Fig. 2B, the denaturation profiles of the tetrasomes containing H3.Y(10–35H3.3), H3.Y(K42R), and H3.Y(L62I) are similar to that of the wild-type H3.Y-H4 tetrasome, and the Tm values of their dissociation curves, 86–87°C, are the same as that of the wild-type H3.Y tetrasome (Fig. 2B). The Tm value of the H3.Y(77–80H3.3) tetrasome (85–86°C) is slightly lower than that of the wild-type H3.Y tetrasome (Fig. 2B). In contrast, the Tm value of the H3.Y(124–135H3.3) tetrasome (81–82°C) was significantly lower than that of the wild-type H3.Y tetrasome (Fig. 2B). These results indicate that the H3.Y region of amino acids 124–135 is important for the stable association of the H3.Y-H4 tetramer with DNA.

Figure 2.

Thermal stability assay of tetrasomes containing H3.Y mutants. (A) Schematic illustration of the thermal stability assay. (B) The thermal denaturation profiles of the tetrasomes containing H3.Y mutants. Experiments with the tetrasomes containing the H3.Y(10–35H3.3), H3.Y(K42R), H3.Y(L62I), H3.Y(77–80H3.3), and H3.Y(124–135H3.3) mutants are presented with the Tm values. Control experiments with the H3.Y and H3.3 tetrasomes are also presented. Averages of 3 independent experiments are plotted with standard deviation values.

Identification of the H3.Y residues responsible for the higher stability of the H3.Y-H4 tetrasome

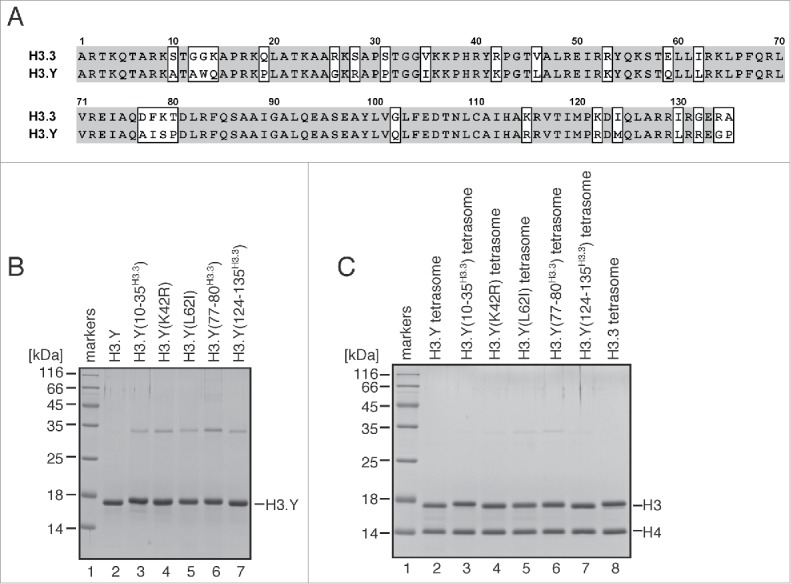

We purified the H3.Y(M124I), H3.Y(L130I), H3.Y(R132G), and H3.Y(G134R) mutants, in which the H3.Y-specific Met124, Leu130, Arg132, and Gly134 residues are replaced by the corresponding H3.3 Ile124, Ile130, Gly132, and Arg134 residues, respectively (Fig. 3A). These H3.Y mutants efficiently formed tetrasomes (Fig. 3B). We found that the tetrasomes containing H3.Y(L130I) and H3.Y(R132G) exhibited the same Tm values (86–87°C) as the wild-type H3.Y tetrasome (Fig. 3C). In contrast, the stabilities of the tetrasomes containing H3.Y(M124I) and H3.Y(G134R) were clearly decreased, with Tm values of 84–85°C and 85–86°C, respectively (Fig. 3C). These results suggested that the H3.Y Met124 and Gly134 residues, but not H3.Y Leu130 and Arg132, may be involved in the stable association of the H3.Y-H4 tetramer with DNA. The H3.Y(M124I) and H3.Y(G134R) mutations actually reduced the stability of the H3.Y tetrasome; however, their effects were much milder than that of the H3.Y(124–135H3.3) mutation. The combinations of amino acid substitutions may enhance the instability of the H3.Y tetrasome.

Figure 3.

Thermal stability assay of tetrasomes containing the H3.Y C-terminal mutants. (A) Purification of the H3.Y(M124I), H3.Y(L130I), H3.Y(R132G), and H3.Y(G134R) mutants. Purified H3.Y mutants were analyzed by 16% SDS-PAGE with Coomassie brilliant blue staining. (B) The reconstituted tetrasomes containing the H3.Y(M124I), H3.Y(L130I), H3.Y(R132G), and H3.Y(G134R) mutants were purified by non-denaturing PAGE, and were analyzed by 16% SDS-PAGE with Coomassie brilliant blue staining. (C) The thermal denaturation profiles of the tetrasomes containing H3.Y mutants. Experiments with the tetrasomes containing the H3.Y(M124I), H3.Y(L130I), H3.Y(R132G), and H3.Y(G134R) mutants are presented with their Tm values. Control experiments with the H3.Y and H3.3 tetrasomes are also presented. Averages of 3 independent experiments are plotted with standard deviation values.

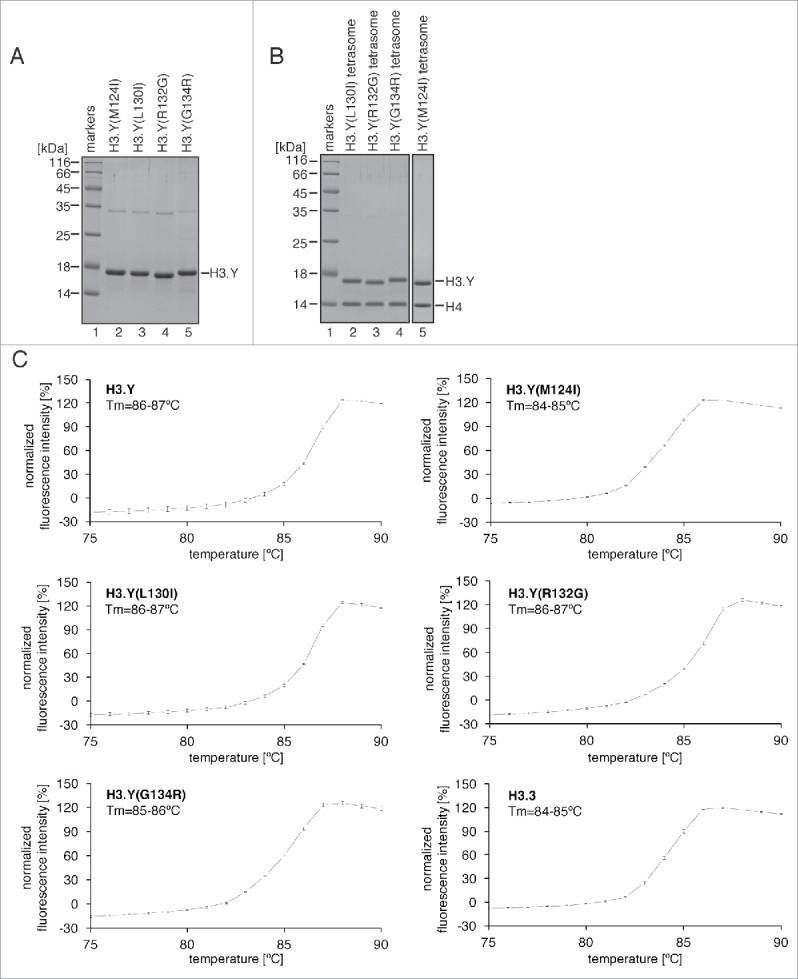

Stability of nucleosomes containing the H3.Y(M124I), H3.3(I124M), H3.Y(K42R), and H3.3(R42K) mutants

We finally reconstituted the nucleosome containing H3.Y(M124I) (Fig. 4A), and tested its thermal stability. The nucleosome thermal stability assay produces a biphasic denaturation curve, in which the first and second peaks correspond to the H2A-H2B dissociation and the H3-H4 dissociation, respectively. As previously reported, in the H3.Y nucleosome, the H2A-H2B dimers dissociated at a slightly lower temperature, as compared with the H3.3 nucleosome (Fig. 4B and C, upper panel). As shown in Fig. 4B, the H3.Y(M124I) mutation decreased the temperature of the second peak, without affecting that of the first peak. This is consistent with the observation that the H3.Y(M124I) mutation decreased the association between H3.Y-H4 and DNA (Fig. 4B, lower panel). Complementarily, the H3.3(I124M) mutant, in which the H3.3 Ile124 residue was replaced by the corresponding H3.Y Met residue, increased the temperature of the second peak (Fig. 4C, lower panel). These results confirmed that the H3.Y Met124 residue plays a role in the H3.Y-H4 stabilization in the nucleosome, as well as in the tetrasome.

Figure 4.

Thermal stability assay of the nucleosomes containing the H3.Y(M124I), H3.Y(K42R), H3.3(I124M), and H3.3(R42K) mutants. (A) The reconstituted nucleosomes containing the H3.Y(M124I) and H3.3(I124M) mutants were purified by non-denaturing PAGE, and were analyzed by 18% SDS-PAGE with Coomassie brilliant blue staining. (B) The thermal denaturation profiles of the nucleosomes containing the H3.Y(M124I) mutant (lower panel). A control experiment with the H3.Y nucleosome is also presented (upper panel). Averages of 3 independent experiments are plotted with standard deviation values. (C) The thermal denaturation profiles of the nucleosomes containing the H3.3(I124M) mutant (lower panel). A control experiment with the H3.3 nucleosome is also presented (upper panel). Averages of 3 independent experiments are plotted with standard deviation values. (D) The reconstituted nucleosomes containing the H3.Y(K42R) and H3.3(R42K) mutants were purified by non-denaturing PAGE, and were analyzed by 18% SDS-PAGE with Coomassie brilliant blue staining. (E) The thermal denaturation profiles of the nucleosomes containing the H3.Y(K42R) mutant (lower panel). A control experiment with the H3.Y nucleosome is also presented (upper panel). Averages of 3 independent experiments are plotted with standard deviation values. (F) The thermal denaturation profiles of the nucleosomes containing the H3.3(R42K) mutant (lower panel). A control experiment with the H3.3 nucleosome is also presented (upper panel). Averages of 3 independent experiments are plotted with standard deviation values.

Finally, we performed thermal stability assays with the nucleosomes containing the H3.Y(K42R) and H3.3(R42K) mutants (Fig. 4D). The H3.Y Lys42 residue is reportedly important for the DNA end flexibility of the H3.Y nucleosome.38 Interestingly, the H3.Y(K42R) and H3.3(R42K) mutants did not change the thermal stabilities of the H3.Y nucleosome and the H3.3 nucleosome, respectively (Fig. 4E and F). Therefore, we conclude that the H3.Y Lys42 residue is not involved in the stable nucleosome formation, although this residue plays a role in conferring flexibility to the nucleosomal DNA ends.

Concluding remarks

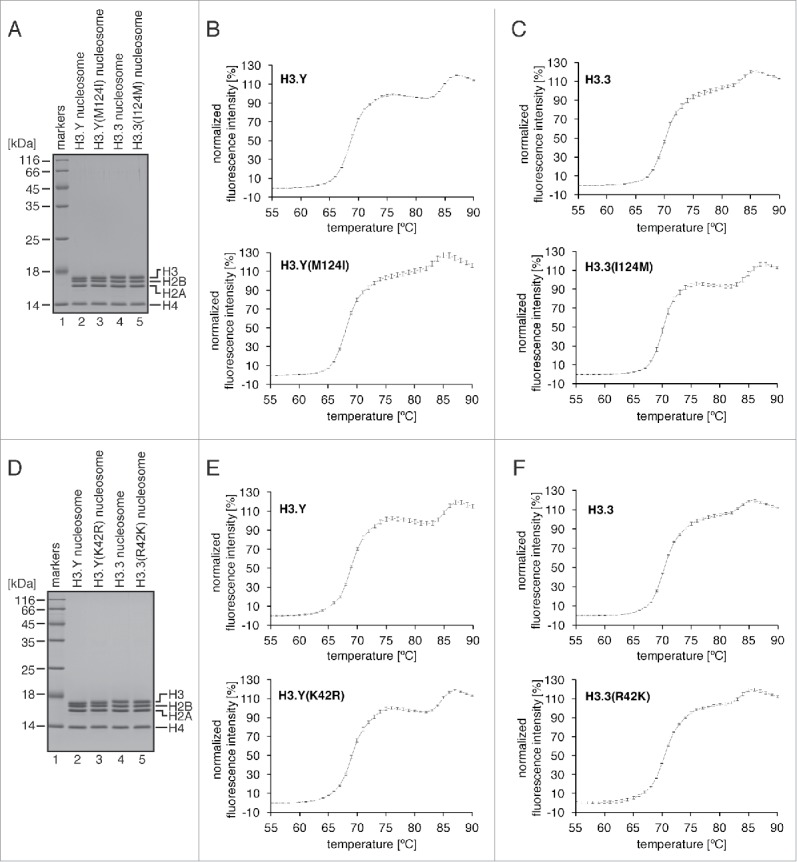

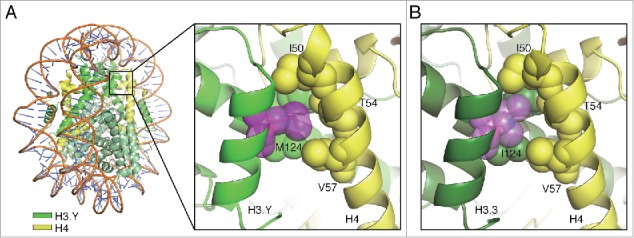

In this Extra View article, we identified the H3.Y Met124 residue as being responsible for the stable H3.Y association in the nucleosome. We previously reported the crystal structures of human nucleosomes containing H3.Y and H3.3.25,38 We then compared the H3.Y and H3.3 nucleosome structures around residue 124. In the H3.Y nucleosome, the side chain moiety of the H3.Y Met124 residue is located near the H4 Ile50, Thr54, and Val57 residues, and probably forms a hydrophobic core (Fig. 5A). The hydrophobic interactions around the H3.3 Ile124 residue are also observed in the H3.3 nucleosome structure (Fig. 5B). The structural differences between the H3.Y-H4 and H3.3-H4 hydrophobic cores may be an important determinant for the nucleosome stability.

Figure 5.

Structures of the H3.Y-H4 and H3.3-H4 interfaces around position 124 in the nucleosomes. (A) A close-up view of the H3.Y-H4 interface around the H3.Y Met124 residue (PDB ID: 5AY8). (B) A close-up view of the H3.3-H4 interface around the H3.3 Ile124 residue (PDB ID: 3AV2). The H3.Y and H3.3 molcules are colored light green and dark green, respectively, and the H4 molecules are colored yellow. The atoms of the amino acid residues involved in the hydrophobic clusters are represented as spheres.

It is intriguing that the H3.Y Lys42 residue does not seem to affect the nucleosome stability, although it is partially involved in the DNA end flexibility of the H3.Y nucleosome.38 Therefore, the H3.Y Lys42 and Met124 residues may have distinct roles in the regulation of DNA dynamics and nucleosome stability, respectively. The Lys42 and Met124 residues are not present in the other human histone H3 variants, except for the closely-related H3 variant, H3.X.44 It is intriguing to understand the biological relevance of these amino acid residues that specifically emerged in histones H3.Y and H3.X.

Materials and methods

Purification of H3.Y mutant proteins and DNA for tetrasome reconstitution

The DNA fragments encoding H3.Y mutants (10–35H3.3, K42R, L62I, 77–80H3.3, 124–135H3.3, M124I, L130I, R132G, and G134R) were prepared by site-directed mutagenesis, and inserted into the pET15b vector. The histones were purified by the method described previously.24 The palindromic 146 base-pair satellite DNA1 was prepared as described previously.48

Reconstitution and purification of tetrasomes and nucleosomes

Purified H3 and H4 were mixed and dissolved in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) buffer, containing 7 M guanidine hydrochloride, 1 mM EDTA, and 20 mM 2-mercaptoethanol. After an incubation at 4°C for 1.5 hr with rotation, the samples were dialyzed against 2 M NaCl refolding buffer, containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 2 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, and the NaCl concentration was reduced to 1 M, 0.5 M, and 0.1 M, in a stepwise manner. The resulting H3-H4 complexes were subjected to HiLoad 16/60 Superdex200 gel-filtration column chromatography (GE Healthcare). The tetrasomes were assembled with the H3-H4 complexes and the 146 base-pair DNA by the salt dialysis method.24 The resulting tetrasomes were heated at 55°C for 2 hr, and were purified by non-denaturing PAGE with a Prep Cell apparatus (Bio-Rad). The purified tetrasomes were stored at 4°C. The nucleosomes were prepared by the method described previously.38

Thermal stability assay

The thermal stability assays of the tetrasomes (2.25 μg of DNA for H3.Y(10–35H3.3), H3.Y(K42R), H3.Y(L62I), H3.Y(77–80H3.3), and H3.Y(124–135H3.3); 4.5 μg of DNA for H3.Y(M124I), H3.Y(L130I), H3.Y(R132G), and H3.Y(G134R)) and the nucleosomes (4.5 μg of DNA) were performed as described previously.49 Briefly, during the thermal denaturation experiments of tetrasomes or nucleosomes, the SYPRO Orange fluorescence signals were measured in real time by the StepOnePlus™ real-time PCR instrument in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) buffer, containing 1 mM dithiothreitol, 100 mM NaCl, and 5x SYPRO Orange. The SYPRO Orange fluorescence signal intensity was normalized as described previously.32

Structural figures

All structure figures were generated with PyMOL (Schrödinger).

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We thank the beamline scientists for their assistance with data collection at the BL41XU beamline of SPring-8 and the BL-17A beamline of the Photon Factory. The synchrotron radiation experiments were performed with the approval of the Japan Synchrotron Radiation Research Institute (JASRI) [proposal nos. 2012A1125, 2012B1048, 2013A1036 and 2013B1060] and the Photon Factory Program Advisory Committee [proposal no. 2012G569].

Funding

This work was supported in part by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers JP25116002 and JP25250023, and also partially supported by the Platform Project for Supporting in Drug Discovery and Life Science Research (Platform for Drug Discovery, Informatics, and Structural Life Science) from Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED). H.K. and N.H were supported by the Waseda Research Institute for Science and Engineering and research programs of Waseda University. T.K. and H.T. were supported by Research Fellowships for Young Scientists from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

References

- [1].Luger K, Mäder AW, Richmond RK, Sargent DF, Richmond TJ. Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 Å resolution. Nature 1997; 389(6648):251-60; PMID:9305837; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/38444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Luger K, Dechassa ML, Tremethick DJ. New insights into nucleosome and chromatin structure: an ordered state or a disordered affair? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2012; 13(7):436-47; PMID:22722606; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nrm3382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hake SB, Allis CD. Histone H3 variants and their potential role in indexing mammalian genomes: the “H3 barcode hypothesis.” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006; 103(17):6428-35; PMID:16571659; https://doi.org/ 10.1073/.pnas0600803103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Loyola A, Almouzni G. Marking histone H3 variants: how, when and why? Trends Biochem Sci 2007; 32(9):425-33; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kaufman PD, Kobayashi R, Kessler N, Stillman B. The p150 and p60 subunits of chromatin assembly factor I: a molecular link between newly synthesized histones and DNA replication. Cell 1995; 81(7):1105-14; PMID:7600578; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/S0092-8674(05)80015-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Franklin SG, Zweidler A. Non-allelic variants of histones 2a, 2b and 3 in mammals. Nature 1977; 266(5599):273-5; PMID:846573; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/266273a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ray-Gallet D, Quivy JP, Scamps C, Martini EM, Lipinski M, Almouzni G. HIRA is critical for a nucleosome assembly pathway independent of DNA synthesis. Mol Cell 2002; 9(5):1091-100; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00526-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Elsaesser SJ, Goldberg AD, Allis CD. New functions for an old variant: no substitute for histone H3.3. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2010; 20(2):110-7; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.gde.2010.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].P Drané, Ouararhni K, Depaux A, Shuaib M, Hamiche A. The death-associated protein DAXX is a novel histone chaperone involved in the replication-independent deposition of H3.3. Genes Dev 2010; 24(12):1253-65; PMID:20504901; https://doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.566910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Goldberg AD, Banaszynski LA, Noh KM, Lewis PW, Elsaesser SJ, Stadler S, Dewell S, Law M, Guo X, Li X, et al.. Distinct factors control histone variant H3.3 localization at specific genomic regions. Cell 2010; 140(5):678-91; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Szenker E, Ray-Gallet D, Almouzni G. The double face of the histone variant H3.3. Cell Res 2011; 21(3):421-34; PMID:21263457; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/cr.2011.14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Maze I, Noh KM, Soshnev AA, Allis CD. Every amino acid matters: essential contributions of histone variants to mammalian development and disease. Nat Rev Genet 2014; 15(4):259-271; PMID:24614311; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nrg3673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Skene PJ, Henikoff S. Histone variants in pluripotency and disease. Development 2013; 140(12):2513-24; PMID:23715545; https://doi.org/ 10.1242/dev.091439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Suto RK, Clarkson MJ, Tremethick DJ, Luger K. Crystal structure of a nucleosome core particle containing the variant histone H2A.Z. Nat Struct Biol 2000; 7(12):1121-4; PMID:11101893; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/81971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Fan JY, Gordon F, Luger K, Hansen JC, Tremethick DJ. The essential histone variant H2A.Z regulates the equilibrium between different chromatin conformational states. Nat Struct Biol 2002; 9(3):172-6; PMID:11850638; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nsb767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Park YJ, Dyer PN, Tremethick DJ, Luger K. A new fluorescence resonance energy transfer approach demonstrates that the histone variant H2AZ stabilizes the histone octamer within the nucleosome. J Biol Chem 2004; 279(23):24274-82; PMID:15020582; https://doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M313152200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Chakravarthy S, Bao Y, Roberts VA, Tremethick D, Luger K. Structural characterization of histone H2A variants. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 2004; 69:227-34; https://doi.org/ 10.1101/sqb.2004.69.227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Bao Y, Konesky K, Park YJ, Rosu S, Dyer PN, Rangasamy D, Tremethick DJ, Laybourn PJ, Luger K. Nucleosomes containing the histone variant H2A.Bbd organize only 118 base pairs of DNA. EMBO J 2004; 23(16):3314-24; PMID:15257289; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Gautier T, Abbott DW, Molla A, Verdel A, Ausio J, Dimitrov S. Histone variant H2ABbd confers lower stability to the nucleosome. EMBO Rep 2004; 5(7):715-20; PMID:15192699; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.embor.7400182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Angelov D, Verdel A, An W, Bondarenko V, Hans F, Doyen CM, Studitsky VM, Hamiche A, Roeder RG, Bouvet P, et al.. SWI/SNF remodeling and p300-dependent transcription of histone variant H2ABbd nucleosomal arrays. EMBO J 2004; 23(19):3815-24; PMID:15372075; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Chakravarthy S, Gundimella SK, Caron C, Perche PY, Pehrson JR, Khochbin S, Luger K. Structural characterization of the histone variant macroH2A. Mol Cell Biol 2005; 25(17):7616-24; https://doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.25.17.7616-7624.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Chakravarthy S, Luger K. The histone variant macro-H2A preferentially forms “hybrid nucleosomes.” J Biol Chem 2006; 281(35):25522-31; PMID:16803903; https://doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M602258200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Tachiwana H, Osakabe A, Kimura H, Kurumizaka H. Nucleosome formation with the testis-specific histone H3 variant, H3t, by human nucleosome assembly proteins in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res 2008; 36(7):2208-18; PMID:18281699; https://doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gkn060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Tachiwana H, Kagawa W, Osakabe A, Kawaguchi K, Shiga T, Hayashi-Takanaka Y, Kimura H, Kurumizaka H. Structural basis of instability of the nucleosome containing a testis-specific histone variant, human H3T. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010; 107(23):10454-9; PMID:20498094; https://doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1003064107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Tachiwana H, Osakabe A, Shiga T, Miya Y, Kimura H, Kagawa W, Kurumizaka H. Structures of human nucleosomes containing major histone H3 variants. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 2011; 67(Pt 6):578-83; PMID:21636898; https://doi.org/ 10.1107/S0907444911014818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Tachiwana H, Kagawa W, Shiga T, Osakabe A, Miya Y, Saito K, Hayashi-Takanaka Y, Oda T, Sato M, Park SY, et al.. Crystal structure of the human centromeric nucleosome containing CENP-A. Nature 2011; 476(7359):232-5; PMID:21743476; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nature10258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Kurumizaka H, Horikoshi N, Tachiwana H, Kagawa W. Current progress on structural studies of nucleosomes containing histone H3 variants. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2013; 23(1):109-15; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.sbi.2012.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Horikoshi N, Sato K, Shimada K, Arimura Y, Osakabe A, Tachiwana H, Hayashi-Takanaka Y, Iwasaki W, Kagawa W, Harata M, et al.. Structural polymorphism in the L1 loop regions of human H2A.Z.1 and H2A.Z.2. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 2013; 69(Pt 12):2431-9; PMID:24311584; https://doi.org/ 10.1107/S090744491302252X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Arimura Y, Kimura H, Oda T, Sato K, Osakabe A, Tachiwana H, Sato Y, Kinugasa Y, Ikura T, Sugiyama M, et al.. Structural basis of a nucleosome containing histone H2A.B/H2A.Bbd that transiently associates with reorganized chromatin. Sci Rep. 2013; 3:3510; PMID:24336483; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/srep03510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Urahama T, Horikoshi N, Osakabe A, Tachiwana H, Kurumizaka H. Structure of human nucleosome containing the testis-specific histone variant TSH2B. Acta Crystallogr F Struct Biol Commun 2014; 70(Pt. 4):444-9; PMID:24699735; https://doi.org/ 10.1107/S2053230X14004695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Sugiyama M, Arimura Y, Shirayama K, Fujita R, Oba Y, Sato N, Inoue R, Oda T, Sato M, Heenan RK, et al.. Distinct features of the histone core structure in nucleosomes containing the histone H2A.B variant. Biophys J 2014; 106(10):2206-13; PMID:24853749; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Arimura Y, Shirayama K, Horikoshi N, Fujita R, Taguchi H, Kagawa W, Fukagawa T, Almouzni G, Kurumizaka H. Crystal structure and stable property of the cancer-associated heterotypic nucleosome containing CENP-A and H3.3. Sci Rep 2014; 4:7115; PMID:25408271; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/srep07115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Kato D, Osakabe A, Tachiwana H, Tanaka H, Kurumizaka H. Human tNASP promotes in vitro nucleosome assembly with histone H3.3. Biochemistry 2015; 54(5):1171-9; PMID:25615412; https://doi.org/ 10.1021/bi501307g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Sugiyama M, Horikoshi N, Suzuki Y, Taguchi H, Kujirai T, Inoue R, Oba Y, Sato N, Marteld A, Porcard L, et al.. Solution structure of variant H2A.Z.1 nucleosome investigated by small-angle X-ray and neutron scatterings. Biochem Biophys Rep 2015; 4:28-32; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bbrep.2015.08.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Padavattan S, Shinagawa T, Hasegawa K, Kumasaka T, Ishii S, Kumarevel T. Structural and functional analyses of nucleosome complexes with mouse histone variants TH2a and TH2b, involved in reprogramming. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2015; 464(3):929-35; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.07.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Urahama T, Harada A, Maehara K, Horikoshi N, Sato K, Sato Y, Shiraishi K, Sugino N, Osakabe A, Tachiwana H, et al.. Histone H3.5 forms an unstable nucleosome and accumulates around transcription start sites in human testis. Epigenetics Chromatin 2016; 9:2; PMID:26779285; https://doi.org/ 10.1186/s13072-016-0051-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Horikoshi N, Arimura Y, Taguchi H, Kurumizaka H. Crystal structures of heterotypic nucleosomes containing histones H2A.Z and H2A. Open Biol 2016; 6(6):pii: 160127; https://doi.org/ 10.1098/rsob.160127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Kujirai T, Horikoshi N, Sato K, Maehara K, Machida S, Osakabe A, Kimura H, Ohkawa Y, Kurumizaka H. Structure and function of human histone H3.Y nucleosome. Nucleic Acids Res 2016; 44(13):6127-41; PMID:27016736; https://doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gkw202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Palmer DK, O'Day K, Wener MH, Andrews BS, Margolis RL. A 17-kD centromere protein (CENP-A) copurifies with nucleosome core particles and with histones. J Cell Biol 1987; 104(4):805-15; https://doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.104.4.805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Albig W, Ebentheuer J, Klobeck G, Kunz J, Doenecke D. A solitary human H3 histone gene on chromosome 1. Hum Genet 1996; 97(4):486-91; PMID:8834248; https://doi.org/ 10.1007/BF02267072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Witt O, Albig W, Doenecke D. Testis-specific expression of a novel human H3 histone gene. Exp Cell Res. 1996; 229(2):301-6; PMID:8986613; https://doi.org/ 10.1006/excr.1996.0375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Brush D, Dodgson JB, Choi OR, Stevens PW, Engel JD. Replacement variant histone genes contain intervening sequences. Mol Cell Biol 1985; 5(6):1307-17; https://doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.5.6.1307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Schenk R, Jenke A, Zilbauer M, Wirth S, Postberg J. H3.5 is a novel hominid-specific histone H3 variant that is specifically expressed in the seminiferous tubules of human testes. Chromosoma 2011; 120(3):275-85; PMID:21274551; https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s00412-011-0310-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Wiedemann SM, Mildner SN, Bönisch C, Israel L, Maiser A, Matheisl S, Straub T, Merkl R, Leonhardt H, et al.. Identification and characterization of two novel primate-specific histone H3 variants, H3.X and H3.Y. J Cell Biol 2010; 190(5):777-91; PMID:20819935; https://doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.201002043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Alilat M, Sivolob A, Révet B, Prunell A. Nucleosome dynamics. Protein and DNA contributions in the chiral transition of the tetrasome, the histone (H3-H4)2 tetramer-DNA particle. J Mol Biol 1999; 291(4):815-41; PMID:10452891; https://doi.org/ 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Jorcano JL, Ruiz-Carrillo A. H3.H4 tetramer directs DNA and core histone octamer assembly in the nucleosome core particle. Biochemistry 1979; 18(5):768-74; PMID:217424; https://doi.org/ 10.1021/bi00572a005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Wolffe A. Chromatin: Structure and Function. 3rd edn. San Diego: :Academic Press; 1998 [Google Scholar]

- [48].Dyer PN, Edayathumangalam RS, White CL, Bao Y, Chakravarthy S, Muthurajan UM, Luger K. Reconstitution of nucleosome core particles from recombinant histones and DNA. Methods Enzymol 2004; 375:23-44; PMID:14870657; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/S0076-6879(03)75002-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Taguchi H, Horikoshi N, Arimura Y, Kurumizaka H. A method for evaluating nucleosome stability with a protein-binding fluorescent dye. Methods 2014; 70(2-3):119-26; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ymeth.2014.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]