Research suggests that patients with melanoma may benefit from partner-assisted skin self-examinations (SSEs) to increase early detection of new melanoma.1 Despite the potential positive aspects of including partners in SSEs, it is plausible that some individuals may be embarrassed or feel uncomfortable having a nonprofessional or intimate partner routinely check their bodies.2–4 One way to mitigate these potential barriers is to increase patient and partner self-confidence in performing SSEs. The current study assessed patient- and partner-reported levels of embarrassment, comfort, and self-confidence in performing SSEs during a 2-year period as part of an SSE education training program.

Methods

Participants were recruited from outpatient clinics of Northwestern Medicine. Eligible patients were between 21 and 80 years old, had previously been diagnosed with stage 0 to IIB melanoma with surgical removal of the melanoma at least 6 weeks prior, and identified a partner to check their skin. Enrolled patients and their partners (n = 395) received an SSE education training program and completed surveys at 4-month intervals from June 6, 2011, to April 24, 2015. To assess the level of embarrassment and level of comfort in performing SSEs, participants were asked to indicate on a 5-point scale how much they agreed or disagreed with the following 2 statements: “It is very embarrassing to have my partner help examine my skin,” and “I am very comfortable having my partner help examine my skin.” To assess self-confidence in performing SSEs, the patients and their partners answered 11 questions (α range, 0.82–0.91) (Box). The Northwestern University Institutional Review Board approved the study. Written informed consent was provided by both the patients and their partners.

Box. Survey Items About Skin Self-examination Confidence for the Patient With Melanoma and Partnera.

I am very confident that I know the difference between a melanoma and other types of moles.

I am very confident that I know how to check my skin for signs of skin cancer.

I am very confident that I can have my partner help check the places that I cannot see myself (such as my back).

I am very confident that I can arrange to have a doctor check my skin once a year.

I am very confident that I know how to examine a mole for an irregular border.

I am very confident that I know how to examine a mole for a consistent (even) color.

I am very confident that I know how to measure the diameter of a mole.

I am very confident that I can keep track of the moles on my partner’s body.

I am very confident that my partner can keep track of his/her moles.

I am very confident that that I can use the ABCDE rule to evaluate my partner’s moles.

I am very confident that my partner can use the ABCDE rule to evaluate his/her moles.

Abbreviation: ABCDE, Assess border, color, diameter, and evolution of the mole.

Items were rated on a 5-point scale, where 1 indicates strongly disagree; 2, moderately disagree; 3, neutral; 4, moderately agree; and 5, strongly agree.

A series of mixed measures analysis of variance was performed for both patients and partners to test for change during the 2-year study period in embarrassment, comfort, and self-confidence in performing SSEs. Differences in change were assessed between men and women. These analyses provide an F statistic to evaluate the effect of time across the 7 waves (baseline and 4-, 8-, 12-, 16-, 20-, and 24-month follow-up), sex, and the interaction between time and sex. The magnitude of the F statistics is used to determine if there are differences across the waves, between men and women, and whether men and women differ across the waves. An F statistic less than 5 tends to indicate there are no significant differences (eg, baseline values are not different than those at 12 and 24 months). Furthermore, these analyses also provide a p value for each F statistic that reflects the probability of making an error in evaluating differences (eg, indicating there are significant differences between the waves when, in fact, there are not). Together, the combination of the F and p values provide statistical rigor in evaluating the results.

Results

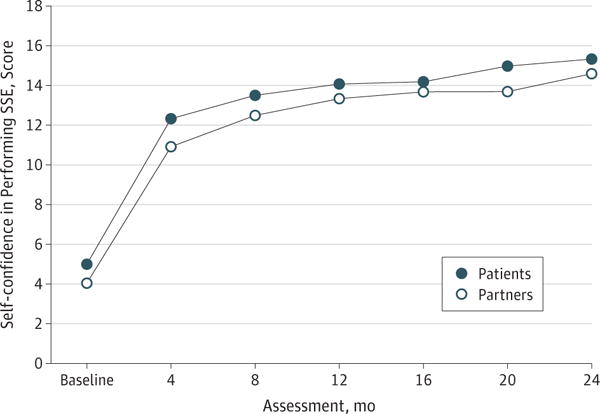

There was no significant change in the level of embarrassment or comfort in performing SSEs during the 2-year study across the 6 time points measured in the 1146 responses from the patients (F6,1146 = 0.93; P = .47; F6, 1134 = 0.22; P = .97, respectively) and partners (F6,1116 = 0.73; P = .63; F6,1116 = 0.49; P = .82, respectively). There was a significant increase from baseline (494 pairs of paitents and partners) to 24 months (291 pairs of patients and partners) in self-confidence in performing SSEs for both patients (F6,1098 = 138.72; P < .001) and partners (F6,1020 = 131.17; P < .001) (Figure). Post hoc paired t tests comparing patients and partners on self-confidence in performing SSEs revealed that patients reported significantly higher levels of self-confidence at all assessments (t values, >2.8; P < .01) except 16 months (t value, 1.69; P = .09) and 24 months (t value, 1.66; P = .10) (Figure). There were no differences between men and women in changes in embarrassment, comfort, or self-confidence.

Figure. Change in Self-confidence About Performing Skin Self-examination (SSE).

Patients and partners increased self-confidence scores from baseline to 24 months.

Discussion

Dyads who received an educational intervention on performing SSEs increased their levels of self-confidence in performing SSEs without increasing levels of embarrassment or decreasing levels of comfort. This finding provides substantive evidence that asking dyads to regularly perform SSEs does not increase emotional barriers (ie, feelings of discomfort or embarrassment). Although it is plausible that there may be a preexisting threshold of comfort in having a partner perform SSEs among patients who enrolled in a study aimed at increasing SSEs with partner assistance, our study participants were all above the threshold. However, our pilot work showed that, of 181 individuals who declined to participate in the study, only 9 indicated that they were uncomfortable having partners help with SSE. This finding indicates that potential embarrassment prevented a relatively small portion of patients (5.0%) from participating. Therefore, dyads indicating some level of embarrassment still will benefit from SSE training and physicians can suggest frequent partner-assisted SSEs.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was supported by grant R01 CA154908 from the National Cancer Institute (Dr Robinson).

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The funding source had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Drs Robinson and Turrisi had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Mallett, Turrisi.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Robinson, Hultgren, Turrisi. Drafting of the manuscript: Robinson, Hultgren, Turrisi.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Mallett, Turrisi.

Statistical analysis: Hultgren, Turrisi.

Obtained funding: Mallett, Turrisi.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Robinson.

Study supervision: Mallett, Turrisi.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

Disclaimer: Dr Robinson is the editor of JAMA Dermatology but was not involved in the editorial review or the decision to accept the manuscript for publication.

Contributor Information

June K. Robinson, Department of Dermatology, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois.

Brittney Hultgren, Biobehavioral Health and Prevention Research Center, Pennsylvania State University, University Park.

Kimberly Mallett, Biobehavioral Health and Prevention Research Center, Pennsylvania State University, University Park.

Rob Turrisi, Biobehavioral Health and Prevention Research Center, Pennsylvania State University, University Park.

References

- 1.Robinson JK, Wayne JD, Martini MC, Hultgren BA, Mallett KA, Turrisi R. Early detection of new melanomas by patients with melanoma and their partners using a structured skin self-examination skills training intervention: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152(9):979–985. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Federman DG, Kravetz JD, Tobin DG, Ma F, Kirsner RS. Full-body skin examinations: the patient’s perspective. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140(5):530–534. doi: 10.1001/archderm.140.5.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Risica PM, Weinstock MA, Rakowski W, Kirtania U, Martin RA, Smith KJ. Body satisfaction effect on thorough skin self-examination. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(1):68–72. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McAuley E, Bane SM, Rudolph DL, Lox CL. Physique anxiety and exercise in middle-aged adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1995;50(5):229–235. doi: 10.1093/geronb/50b.5.p229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]