Abstract

We examined whether the responsiveness to an increase in cigarettes price differed by adolescents’ cigarette acquisition source. We analyzed data on 6134 youth smokers (grades 7–12) from a cross-sectional survey in Korea with national representativeness. The respondents were classified into one of the following according to their source of cigarette acquisition: commercial-source group, social-source group, and others. Multiple logistic regressions were performed to estimate the effects of an increase in cigarette price on the intention to quit smoking on the basis of the cigarette acquisition source. Of the 6134 youth smokers, 36.0% acquired cigarettes from social sources, compared to the 49.6% who purchased cigarettes directly from commercial sources. In response to a future cigarette price increase, regardless of an individual's smoking level, there was no statistically significant difference in the odds ratio for the intention to stop smoking in association with cigarette acquisition sources. The social-source group had nonsignificant, but consistently positive, odds ratios (1.07–1.30) as compared to that of the commercial-source group. Our findings indicate that the cigarette acquisition source does not affect the responsiveness to an increase in cigarette price. Therefore, a cigarette price policy is a comprehensive strategy to reduce smoking among youth smokers, regardless of their source.

Keywords: differential responsiveness, price policy, smoking cessation, source of cigarette access, youth smokers

1. Introduction

One of the most efficient smoking cessation policies widely implemented across the world is the cigarette price policy. Adolescents, in particular, are reported to be more responsive to cigarette price policy owing to their addiction levels and low disposable income.[1] The WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) emphasizes in Article 6 that price and tax measures are an efficient means of reducing tobacco consumption by young person.[2]

However, given that the youth often do not buy cigarettes directly, they are likely to show varying degrees of responsiveness to an increase in cigarette prices. According to the 1995 Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) data, 52.9% of current smokers <18 years of age accessed cigarettes through various social sources, such as borrowing (32.9%), third-party purchasing (15.8%), or stealing (4.2%), and 40.9% gained access through commercial sources, such as stores (38.7%) or vending machines (2.2%).[3] According to the 2013 YRBS data, only 18.1% youths (9–12 graders) directly purchased cigarettes from retailers, which is about half the number reported in 1995, and this rate was consistently maintained at below 20% since 2001.[4]

Increasing dependency of US youth smokers on social sources after 1995 can be attributed to an increase in cigarette tax.[5] With increasingly stringent measures by smoking cessation policies, such as raising cigarette prices and banning cigarette sales to minors, social sources are expected to play an increasingly important role as the primary means for youth smokers to acquire cigarettes. However, cigarette price policies tend to increase the economic burden, and thus, the impact of an increase in cigarette price on youth smoking cessation is expected to vary by source. To counteract the tendency of youth smokers obtaining cigarettes from social sources, and consequently, reduce youth smoking rates, separate nonprice measures should be implemented for the social-source group. To develop a youth smoking cessation policy on the basis of this rationale, the effectiveness of a price policy contingent on the sources of cigarette access should first be evaluated. Although many studies have been conducted on the differential responsiveness to cigarette price increase on the basis of personal and social factors—such as purchase limit, cigarette advertising ban, allowance, and smoking intensity[6–10]—the varying responsiveness of youth smokers to price according to their sources of cigarette access has been largely overlooked by researchers, even though the sources are closely associated with price policy, which is said to be the most efficacious control measure for youth tobacco consumption.

Through a literature review, we identified 2 studies on the relationship between cigarette price and the source of cigarette access using YRBS data; however, both presented inconsistent results. Katzman et al[11] examined data from 4 consecutive national YRBS (1995, 1997, 1999, 2001) and revealed that the commercial-source group was more sensitive to price policies than the social-source group. Hansen et al[5] also adopted YRBS data (1995–2011)—particularly data for the 2000s, when cigarette taxes increased by a greater extent—and showed that increase in cigarette tax affected acquisition through social sources by minors (<18 years) who could not legally purchase cigarettes.

Although in 2013 only about 20% youth smokers in the Unites States bought their own cigarettes, the direct purchase rate in 2014 for those in Korea was about 50%.[4,12] This suggests that youth smokers’ source of cigarettes differ by country, and particularly, sociocultural background, which in turn may have varying effects on cigarette price policies. To the best of our knowledge, no study has been conducted in Asia on the impact of price increase on the sources of cigarette acquisition. Furthermore, the effects of price policy need to be evaluated from a macro- and microeconomic perspective. Although a macroeconomic approach is appropriate to identify the overall smoking rates in complex environments, including various sociocultural contexts and smoking cessation policies, it poses limitations in directly evaluating individual responsiveness to an increase in cigarette prices. Behavioral changes can be evaluated by investigating an individual's responsiveness to a microeconomic approach. Both aforementioned studies empirically evaluated their results from a macroeconomic perspective using self-reported YRBS data.[5,11] A YRBS questionnaire, however, does not include items on individual behavior changes related to cigarette price increase, and thus cannot be used to derive individual differences in price responsiveness. However, the 2013 Korean Youth Risk Behavior Survey (KYRBS) contains such items and allows for the evaluation of price responsiveness at the individual level. Moreover, the fact that initial or low-intensity youth smokers are more likely to obtain cigarettes from social sources[13] can also affect price responsiveness through an addiction or economic burden. Finally, the mentioned studies failed to account for smoking intensity when evaluating price responsiveness.[5,11]

Against this background, this study adopts a microeconomic approach to identify whether youth smokers that access cigarettes through commercial sources are more responsive to price changes than the social-source group for economic reasons. To do so, it uses relevant data from a survey on youth smoking in Korea that has nationwide representativeness, thereby including smoking intensity, which has been overlooked in previous studies, as a confounding factor.

2. Methods

2.1. Study population

This study examined data from the ninth Korea Youth Risk Behavior Web-based Survey (KYRBS-IX) conducted in 2013 by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The KYRBS is a cross-sectional survey with national representativeness that is used monitor adolescents’ health behavior in Korea. It uses a stratified multistage probability sample comprising middle- and high-school students from grades 7 to 12. A self-reporting anonymous online survey was used to protect participants’ privacy. A total of 72,435 students from 800 schools (400 middle- and 400 high-schools) completed the KYRBS-IX (response rate = 96.4%).[14] Of these, the study population was limited to 7094 current smokers and an additional 960 students who did not provide price-responsiveness information or intend to stop smoking, irrespective of an increase in cigarette prices, leaving a total of 6134 current smokers (4629 boys and 1505 girls) in the final analysis. Here, current smokers are defined as adolescents who reported any smoking in the past month. This secondary data analysis was approved as exempt from review by the Institutional Review Board of the Daegu Catholic University Medical Center (CR-15-051).

2.2. Measures

The outcome variable “responsiveness to an increase in cigarette price” was assessed in response to a hypothetical situation: “At what cigarette price would you intend to quit smoking?” The respondents were asked to select one of the following options: continue smoking despite the price increase, 2500 won, 3000 won, 3500 won, 4000 won, 5000 won, 6000 won, 7000 won, 8000 won, 9000 won, and over 10,000 won. Since the retail cigarette price under investigation at the time was 2500 won (1113 won = US$1) per pack, respondents who reported 2500 won were classified into “stop smoking regardless of cigarette price increase” and excluded from the study's population, assuming they were smokers unaffected by price policies. The responsiveness to a hypothetical increase in cigarette price was measured using the responses coded from 3 to 11 (responsiveness to price) and 1 (nonresponsiveness to price).

The cigarette acquisition sources were assessed using the responses to the following question: “In the past 30 days, what was your usual method of acquiring cigarettes? (Select only one principal category).” Participant were provided with 5 possible answers: (1) I took them from my house or friend's house; (2) I directly purchased them from a store; (3) I borrowed them from friends or seniors; (4) I borrowed them from adults; and (5) I picked them up off the ground. The responses were then classified into the following 3 categories: commercial source (2), social source (3 or 4), and others (1 or 5).

The other covariates comprise 3 domains: sociodemographic, lifestyles and psychosocial factors, and smoking-related factors. Sociodemographic variables included age, school type (middle school, general high school, or vocational high school), region of residence (metropolitan city, city, or province), perceived academic performances (high, middle, or low), weekly allowance in Korean won (<10,000, 10,000–29,999, 30,000–49,999, or ≥50,000). Lifestyles and psychosocial factors included frequency of alcohol drinking per month (never, <6 times, or ≥6 times), experience of drug use (yes or no), and perceived stress level (low, middle, or high). Smoking-related factors comprised the number of cigarettes smoked per day in the past 30 days (<1, 1–5, about half a pack, or one-half pack or more), second-hand smoke at home in the past 1 week (yes or no), current use of electronic cigarettes (yes or no), and attempt to quit in the past 1 year (yes or no).

2.3. Statistical analysis

Logistic regression was conducted to estimate the relationship between the intention to quit smoking caused by a hypothetical increase in cigarette price and related factors including cigarette sources. Since smoking amount is the most powerful factor of price responsiveness, the smoking amount-stratified adjusted odds ratios (OR) for the intention to quit smoking were presented on the basis of their cigarette acquisition source. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 19.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY), and a P <.05 was considered significant. All results are presented using complex sampling procedures in SPSS to represent the adolescent population in Korea.

3. Results

3.1. Main characteristics of the study population

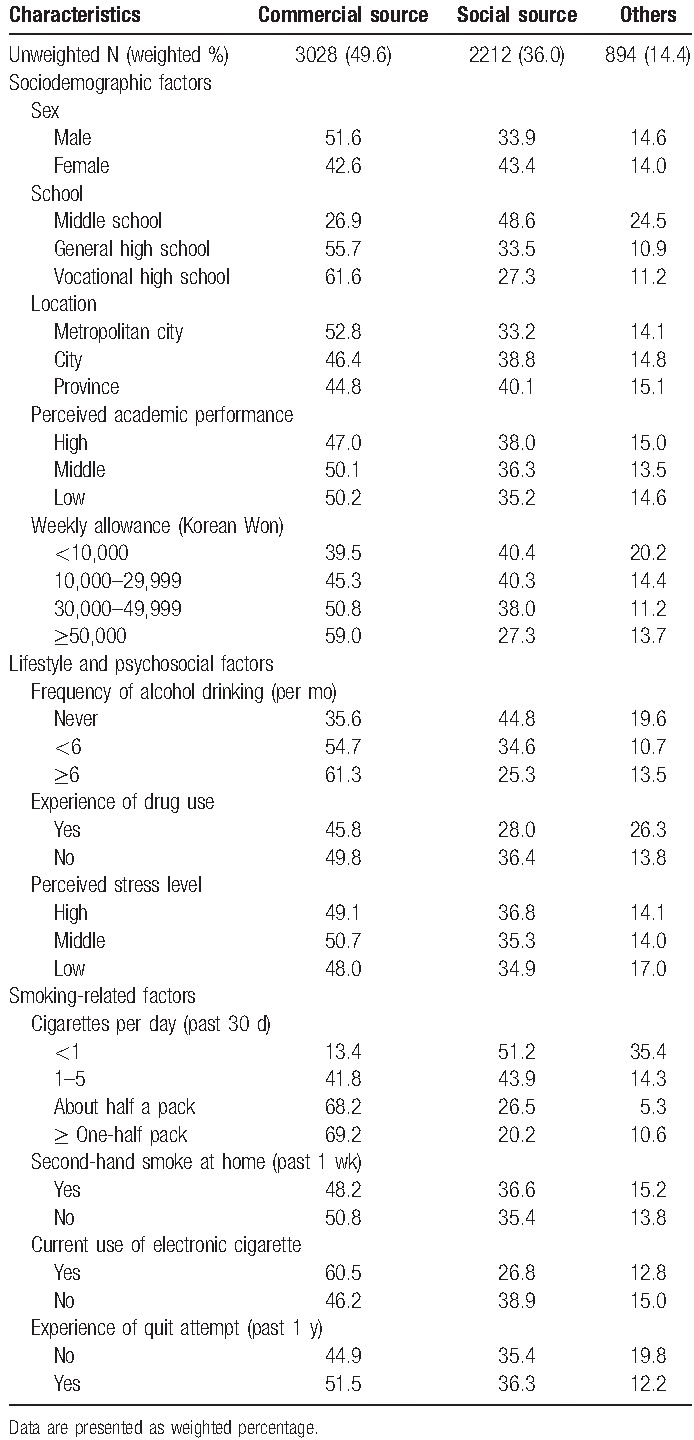

Nearly half (49.6%) of the current youth smokers directly purchased cigarettes from stores; 36.0% of them acquired them from a social source, such as friends, seniors, or adults; and the remaining 14.4% got them through other sources. The proportion of cigarettes acquisition from commercial sources was higher among students who received a higher allowance or frequently consumed alcohol. The more a youth smoked, the higher the cigarette acquisition proportion from commercial sources (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary statistics of variables by sources of cigarette.

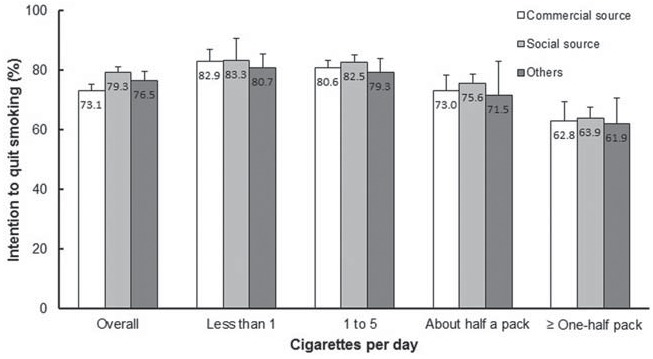

Figure 1 shows that the rates of intention to quit smoking caused by a hypothetical increase in price were 73.1% for commercial sources, 79.3% for social sources, and 76.5% for others. The intention to quit smoking steadily decreased with an in increase smoking amount; however, price responsiveness affected the social-source group more than the commercial-source group, regardless of smoking amount (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Intention-to-quit smoking caused by hypothetical price increase, by sources of cigarettes. Data are presented as the weighted percentage ±95% confidence interval.

3.2. Intention to quit smoking and cigarette acquisition sources

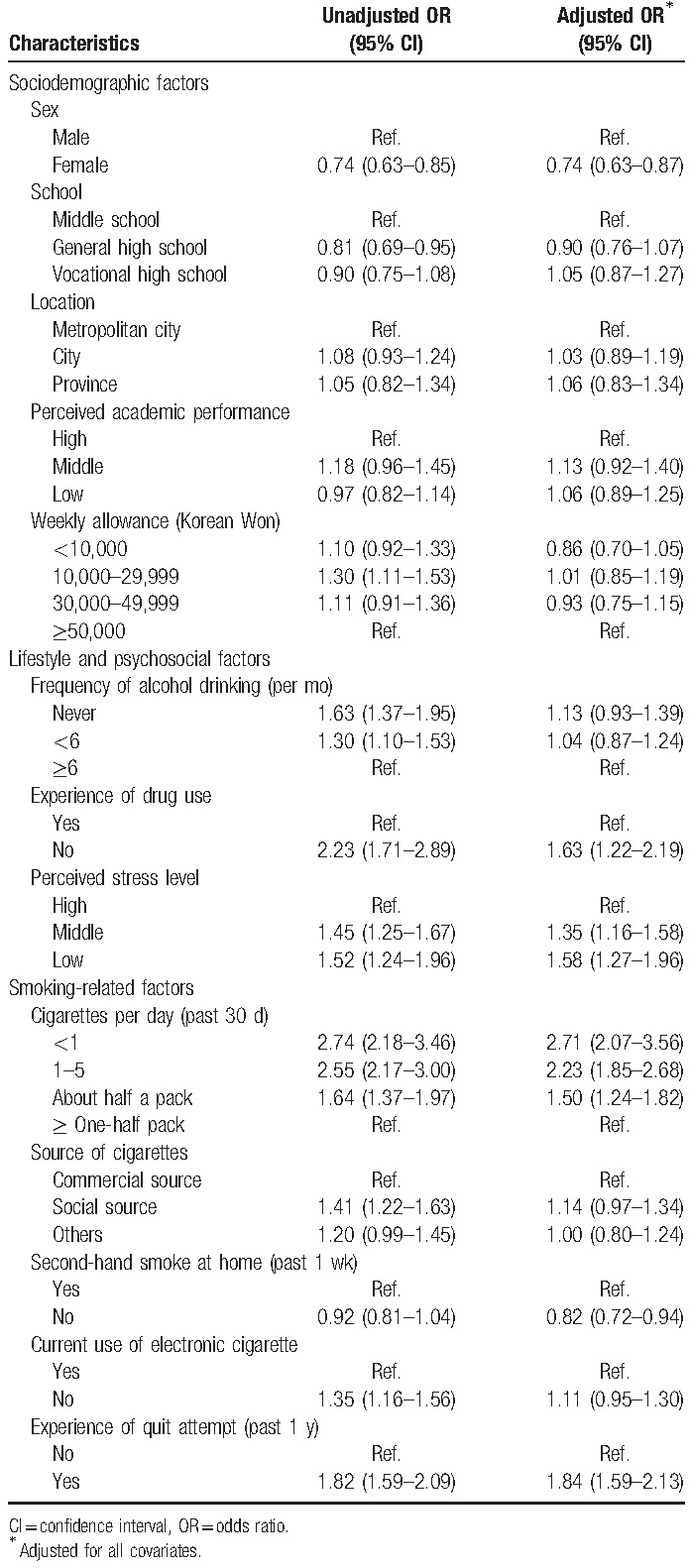

The unadjusted and adjusted ORs for intention to quit smoking are shown in Table 2. Among the sociodemographic factors, sex, school type, and weekly allowance were significantly associated with the intention to quit smoking according to a hypothetical increase in cigarette price. Unadjusted ORs for the intention to quit smoking were significantly higher for those who were nondrug users, nonelectronic cigarette users, had a lower alcohol drinking and stress level, and attempted to quit in the past year. Unadjusted ORs increased from 1.64 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.37–1.97) to 2.74 (95% CI, 2.18–3.46) for those who smoked from one-half pack or more to <1 cigarette per day. Youth smokers who acquired cigarettes from social sources had a significant OR of 1.41 (95% CI, 1.22–1.63) compared with those who used commercial sources (Table 2)

Table 2.

Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (95% confidence interval) for intention to quit smoking according to a hypothetical cigarettes price increase.

After adjusting for all the covariates, the number of cigarettes per day still had a strong and statistically significant association with the intention to quit smoking. However, a significant association between school type, weekly allowance, alcohol drinking, and electronic cigarette use and the intention to quit smoking disappeared. Cigarette sources, a key interest in this study, also had a nonsignificant OR of 1.14 (95% CI, 0.97–1.34) in the social-source group; however, the direction of association between commercial- and social-source groups did not change in the opposite direction.

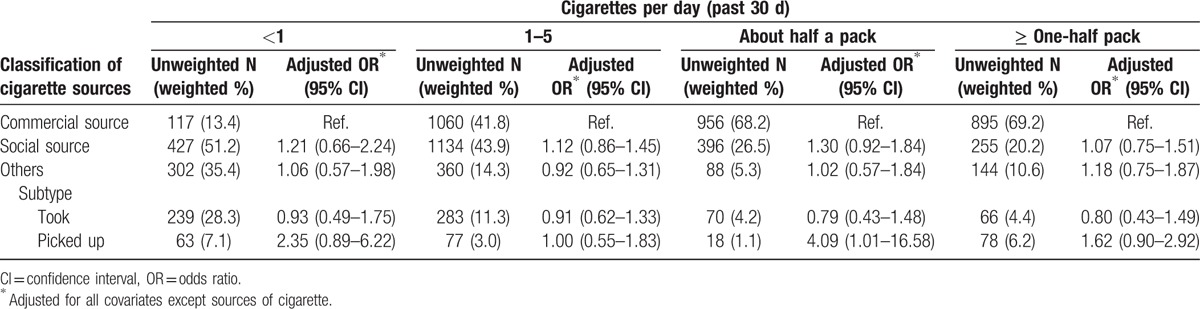

3.3. Intention to quit smoking and cigarette acquisition sources: smoking level-stratified analysis

To exclude the effect of smoking amount on the intention to quit smoking, we used the smoking level-stratified adjusted ORs (Table 3). The social-source group had nonsignificant, but consistently positive, ORs (1.07–1.30) as compared to the commercial-source group. The others group did not have as consistent a direction as the commercial-source group. However, after classifying the 2 groups of “took from house” and “picked up off the ground,” the former group had nonsignificant, but consistently negative, ORs (0.79–0.93) as compared to the commercial-source group.

Table 3.

The smoking level-stratified adjusted odds ratios (95% confidence interval) for intention to quit smoking according to a hypothetical cigarettes price increase.

4. Discussion

The authors hypothesized that, for economic reasons, increase in cigarette prices affect smokers who access cigarettes through commercial sources than those using social sources. However, no statistically significant intergroup difference was confirmed, with the social-source group showing a higher odds ratio for a price-related intention to quit smoking. That no statistically significant difference between the commercial- and social-source groups was found can be attributed to statistical power. Nevertheless, this limitation in statistical power can be outweighed by the following strengths in the data used. First, the KYRBS is a stable youth health behavior survey with nationwide representativeness that has been annually administered since 2005. The number of respondents for the KYRBS-IX (2013) was 72,435 (1.9% youth population), including 6100 current smokers. Second, the ORs were computed using a design-based analysis, which yields more accurate ORs and confidence intervals than a design-ignored analysis and accounts for the sample characteristics of complex samples extracted using stratified cluster sampling methods.[15] Errors likely to occur in the sample survey, such as sampling and parameter measurement errors, were thus minimized.

Although the statistical significance level was not reached, the stratified estimates for smoking levels were generally higher in the social-source group than the commercial-source group, irrespective of smoking intensity. In addition, when the group accessing cigarettes through neither commercial nor social sources (other source group) was divided into subgroups of “took from house” and “picked up off the ground,” the odds ratio of the former subgroup, which was expected to be less sensitive to price changes, was consistently lower than that for the commercial-source group, although without statistical significance. As for the latter subgroup, the reliability of its odds ratio was considered to be limited owing to its low proportion (3.8%; 236/6134) and rather broad confidence interval.

This study's finding that the social-source group was equally or more sensitive to an increase in cigarette prices than the commercial-source group was not entirely consistent with that of previous studies. Although concordance was verified that not only direct purchasers but also borrowers were influenced by increased cigarette prices, statistical significance and the strength of association with the results varied across studies. Althouugh Katzman et al[11] reported that direct purchasers were influenced more by a price increase, a finding contrary to that in this study, Hansen et al[5] yielded the same result when cigarette acquisition was divided into social and commercial sources. However, when the social-source group was divided into borrower and proxy-purchaser subgroups, the latter was influenced with statistical significance, followed by direct purchaser and borrower groups, but without statistical significance.

The nondiscriminatory impact of increased cigarette prices on youth smokers who access cigarettes through various sources can be explained with the following 3 reasons. First, when the social-source group is subdivided into proxy purchasers and borrowers, the YRBS data indicate that more than one-third of the social-source group accessed cigarettes through proxy purchasers, such as friends or older acquaintances.[16] They are, thus, assumed to incur an economic burden as a result of the price increase. This is consistent with our finding that proxy purchasers are more sensitive to price increase than direct purchasers.[5] Second, borrowers are not unidirectional recipients but providers because friends and classmates generally share a cigarette.[17] Croghan et al[18] explained that cigarette exchanges can be considered mutual generosity or future reciprocation among youth smokers. Extending this finding, DiFranza et al[19] reported that the switch from borrower to buyer can be attributed to increasing dependency on cigarette providers through higher smoking intensity and the ensuing imbalance in mutual generosity and its limitations. Likewise, such mutual generosity becomes more difficult to maintain in the case of increasing cigarette prices. In particular, borrowers are more likely to be forced to stop smoking because they face more difficulties than buyers in directly purchasing cigarettes from stores. Third, although borrowers’ primary cigarette acquisition is through social sources, commercial sources are always an alternative, which implies that borrowers are inevitably influenced by the price policy. Thus, the social-source group is expected to have equal or even higher price responsiveness than the commercial-source group.

There is a growing global demand for an increase in cigarette prices. The most recent price increase in Korea was in January 2015, when the cigarette price almost doubled from 2500 to 4500 won per pack,[20] an 80% increase from the previous hike in 2005 of 500 won (25%). The extent to which the 2015 price increase reduced smoking has not yet been evaluated. However, those opposing the price policy use this lack of research to their advantage to continuously raise doubts regarding the efficacy of the price policy. For example, they may insist that, from an economic perspective, the policy is effective in only two-third youth smokers (commercial-source group), given that over one-third youth smokers access cigarettes through social sources. Therefore, by verifying the effects of the price policy on youth smokers, irrespective of cigarette acquisition source, this study provides a scientific basis that supports the efficacy of the price policy. Furthermore, the increasingly stringent prohibition of cigarette sales to minors, along with the expansion of control measures for tobacco consumption, highlights the importance of social sources in cigarette acquisition. Thus, research into cigarette acquisition sources can play a crucial role in future control policies aimed at curbing youth smoking. To this effect, this study contributes to the literature its evaluation of the effects of price policies.

Nevertheless, this study has a few limitations, which should be kept in mind when understanding its results. First, tobacco cessation, the dependent variable in this study, is a response to an uncertain increase in cigarette prices and thus, is likely to deviate from an actual price increase. Second, the KYRBS questionnaire has the following structural problems: the social-source group does not differentiate between proxy purchasers and borrowers; as the question concerns the primary acquisition source, the answer is not mutually exclusive to the remaining examples. Therefore, no explanation was found to shed light on the mechanism underlying the nondiscriminatory price responsiveness among the sources of cigarette acquisition—as opposed to a previous study which reported that the proxy-purchaser group was most affected.[5] Thus, a follow-up study is needed to address this. Third, the statistical power of this study (0.563) did not reach the optimal level (0.80), and the possibility of the odds ratio being false negative cannot be ruled out. However, this study was conducted on 6100 current youth smokers using the stable and reliable KYRBS data with nationwide representativeness for over 70,000 Korean adolescents. Although the difference in OR between the commercial- and social-source groups is too small (OR = 1.13) to yield sufficient statistical power, considering that the statistical power relates to confidence intervals and not estimates, it should not be taken for granted that the commercial-source group is more price responsive than the social-source group. In fact, once an adequate statistical power is secured, we may conclude that the social-source group is more responsive to a price increase than the commercial-source group. It is necessary to carry out further studies with sufficient statistical power.

Despite the abovementioned limitations, the present study differs from those in the extant literature in that youth smokers’ responsiveness to an increase in cigarette price was assessed at an individual level and the analysis was performed using estimates stratified by smoking level, which is directly associated with cigarette acquisition sources. This study reaffirms the efficacy of cigarette price policy as a comprehensive approach to tobacco control measures for the youth, regardless of cigarette acquisition source. The findings of this study are expected to serve as a scientific basis to establish tobacco control measures for the youth that are mediated price policies.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval, FCTC = Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, KYRBS = Korean Youth Risk Behavior Survey, OR = odds ratio, YRBS = Youth Risk Behavior Survey.

This work was supported by research grants from the Catholic University of Daegu in 2015 (20155001).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Lantz PM, Jacobson PD, Warner KE, et al. Investing in youth tobacco control: a review of smoking prevention and control strategies. Tob Control 2000;9:47–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Guidelines for implementation of Article 6 of the WHO FCTC (Price and tax measures to reduce the demand for tobacco) 2014. Available at: http://apps.who.int/gb/fctc/PDF/cop6/FCTC_COP6(5)-en.pdf (accessed 17.11.2014). [Google Scholar]

- [3].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tobacco use and usual source of cigarettes among high school students—United States, 1995. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1996;45:413–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin SL, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2013. MMWR Suppl 2014;63(Suppl. 4):1–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hansen B, Rees DI, Sabia J. Cigarette taxes and how youth obtain cigarettes. Natl Tax J 2012;66:371–94. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Do YK, Farooqui MA. Differential subjective responsiveness to a future cigarette price increase among South Korean youth smokers. Nicotine Tob Res 2012;14:209–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Liang L, Chaloupka FJ. Differential effects of cigarette price on youth smoking intensity. Nicotine Tob Res 2002;4:109–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Nikaj S, Chaloupka FJ. The effect of prices on cigarette use among youths in the global youth tobacco survey. Nicotine Tob Res 2014;16(Suppl. 1):S16–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Scollo M, Hayes L, Wakefield M. What price quitting? The price of cigarettes at which smokers say they would seriously consider trying to quit. BMC Public Health 2013;13:650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Stead LF, Lancaster T. Interventions for preventing tobacco sales to minors. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005. Cd001497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Katzman B, Markowitz S, McGeary KA. An empirical investigation of the social market for cigarettes. Health Econ 2007;16:1025–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ministry of Education, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The 10th Korea Youth Risk Behavior Web-Based Survey. Chungwon: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Castrucci BC, Gerlach KK, Kaufman NJ, et al. Adolescents’ acquisition of cigarettes through noncommercial sources. J Adolesc Health 2002;31:322–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Statistics of the Nineth Korea Youth Risk Behavior Web-Based Survey. Osong, Korea: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Chantala K, Tabor J. National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health: Strategies to Perform a Design-Based Analysis Using the Add Health Data. Chapel Hill, NC: Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Centers for Disease Control Prevention. 2013 YRBS Data User's Guide. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/yrbs/pdf/YRBS_2013_National_User_Guide.pdf (accessed 20.04.2015). [Google Scholar]

- [17].Forster J, Chen V, Blaine T, et al. Social exchange of cigarettes by youth. Tob Control 2003;12:148–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Croghan E, Aveyard P, Griffin C, et al. The importance of social sources of cigarettes to school students. Tob Control 2003;12:67–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].DiFranza JR, Eddy JJ, Brown LF, et al. Tobacco acquisition and cigarette brand selection among youth. Tob Control 1994;3:334. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Song SH, Lee HJ. Tax hike will push price of cigarette packs up 80%. Korea Joongang Daily, September 12; 2014. Available at: http://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/news/article/Article.aspx?aid=2994741 (accessed 11.11.2014). [Google Scholar]