Abstract

We investigated the degree of pain reduction following intra-articular (IA) pulsed radiofrequency (PRF) stimulation of the sacroiliac joint (SIJ) in patients with chronic SIJ pain that had not responded to IA corticosteroid injection. Twenty patients were recruited. Clinical outcomes after applying PRF stimulation of the SIJ were evaluated by a numeric rating scale (NRS) and a 7-point Likert scale. The NRS scores significantly changed over time. The NRS scores at 1, 2, and 3 months after PRF were significantly lower than those before PRF. However, 4 of the 20 patients (20%) reported successful pain relief (pain relief of ≥ 50%) and were satisfied with the PRF stimulation at 3 months after treatment. IA PRF stimulation of the SIJ was not successful in most patients (80% of all patients). Based on our results, we cannot recommend this procedure to patients with chronic SIJ pain that was unresponsive to IA SIJ corticosteroid injection. Further studies on the effective mode of PRF stimulation and appropriate patient group, and studies on pain conditions that are most responsive to PRF are needed in the future.

Keywords: chronic pain, feasibility, intra-articular stimulation, pulsed radiofrequency, refractory pain, sacroiliac joint pain

1. Introduction

Sacroiliac joint (SIJ) pain is one of the most common causes of chronic lower back pain, accounting for 10% to 27% of patients with chronic lower back pain.[1,2] It is known to be caused by abnormal motion in the SIJ, namely, too much motion or too little motion.[3] Patients with SIJ pain experience various degrees of pain in the low back, groin, buttock, or posterior thigh.[1,2] The treatment of SIJ pain is challenging. Intra-articular (IA) injection with corticosteroid has been most commonly used for the management of SIJ pain.[4–6] However, in clinical practice, the duration of its effect is limited and a therapeutic effect was not consistently seen in all patients.[7,8]

Pulsed radiofrequency (PRF), first introduced by Sluijter in 1997,[9] is widely used for the treatment of nerves that cause neuropathic pain.[10,11] Continuous radiofrequency (CRF) involves continuous stimulation and results in ablation of nerves and tissues by using frictional heat arising from a catheter needle.[12] However, PRF uses a brief stimulation followed by a long resting phase, which exposes the target nerves and tissues to an electric field without producing sufficient heat to cause structural damage.[13] The proposed mechanism of PRF is that the electrical field produced by PRF can alter pain signals.[14] To date, several reports have shown that PRF can successfully modulate several types of pain, including neuralgia, joint pain, and myofascial pain.[10,15,16] PRF on the lumbar medial branches and sacral lateral branches was reported to effectively control SIJ pain.[17] Recently, it has been reported that PRF can be used to control pain in various joints by the placement of the needle electrodes into the joint space and subsequent PRF simulation.[18,19] However, little is known about the effect of IA PRF stimulation for controlling SIJ pain.

In the current study, we treated chronic SIJ pain that had been unresponsive to IA corticosteroid injection by placing an electrode into the SIJ space and applying PRF. We aimed to evaluate the feasibility of PRF stimulation of the SIJ in patients with chronic SIJ pain that was unresponsive to IA SIJ corticosteroid injection.

2. Methods

2.1. Patients

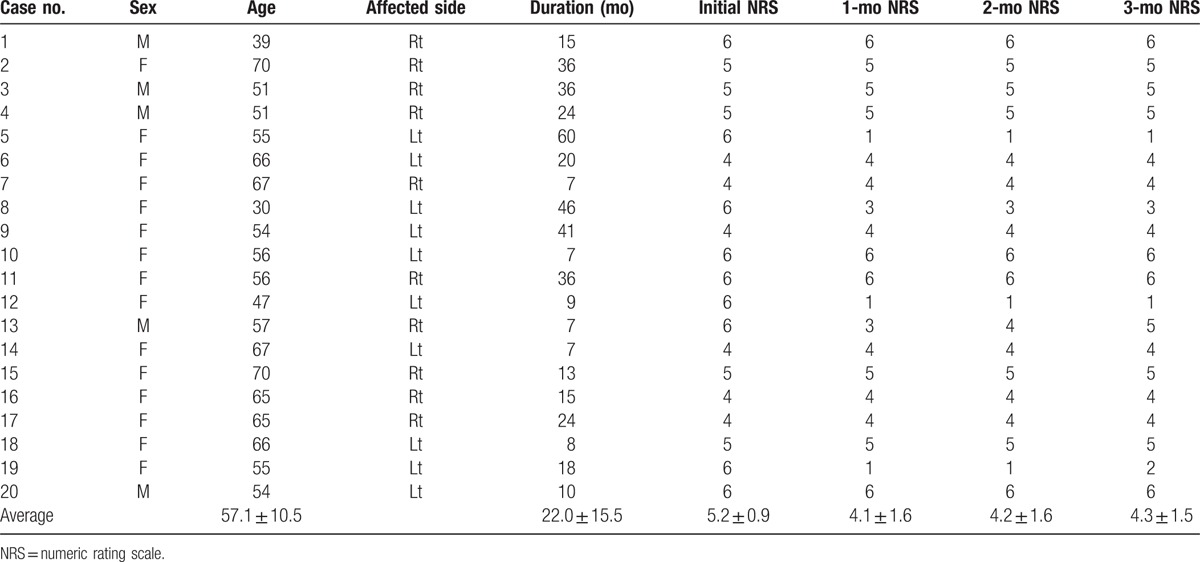

This study was conducted retrospectively. Consecutive patients who visited the rehabilitation department for chronic SIJ pain during the period from March 2014 to July 2016 were analyzed. SIJ pain was diagnosed when patients showed a positive result in at least one of the following tests[20]: pressure application to a sacroiliac ligament,[21] Gaenslen test,[22] or Patrick test.[23] Furthermore, for the diagnosis of SIJ pain, they were required to show a reduction of pain of at least 50% for at least 30 minutes after a diagnostic block using 0.5 mL of 2% lidocaine intra-articularly and 0.3 mL of 2% lidocaine periarticularly.[24] Out of patients who diagnosed as having SIJ pain, 203 patients who had SIJ pain of at least 4 on the numeric rating scale (NRS, 0 indicating no pain and 10 indicating the worst pain imaginable) despite pain medication (meloxicam 15 mg and acetaminophen/tramadol hydrochloride 325/37.5 mg) received therapeutic IA SIJ corticosteroid injection. For therapeutic injection, 0.5 mL of 2% lidocaine with 10 mg triamcinolone acetonide (total volume 1.5 mL) were administered. Each procedure was conducted by a physician who had experience of IA SIJ steroid injection over 10 years. IA PRF stimulation of the SIJ was performed when the patient's SIJ pain was scored at least 4 on the NRS despite at least 1 IA SIJ corticosteroid injection. We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of 203 patients, and 20 patients (mean age: 57.1 ± 10.5, range 30–70, M:F = 5:15, interval from pain onset to PRF [months]: 22.0 ± 15.5, range 7–46) were analyzed using the following inclusion criteria (Table 1): age between 20 and 70 years; IA PRF stimulation of the SIJ due to an unsatisfactory response to IA SIJ corticosteroid injections (pain of at least 4 on the NRS in the region of the SIJ despite more than 1 IA SIJ corticosteroid injection); no interval change in the NRS scores over 4 weeks after the last SIJ corticosteroid injection before PRF stimulation into SIJ; and unilateral SIJ pain. We excluded patients who had other possible sources of low back pain by means of a physical examination, medical history, magnetic resonance imaging/computed tomography/X-ray, and rheumatology screening. The Institutional Review Board of Yeungnam university hospital approved the study protocol.

Table 1.

Demographic data and clinical outcome for each patient (values ± standard deviations).

2.2. PRF procedure

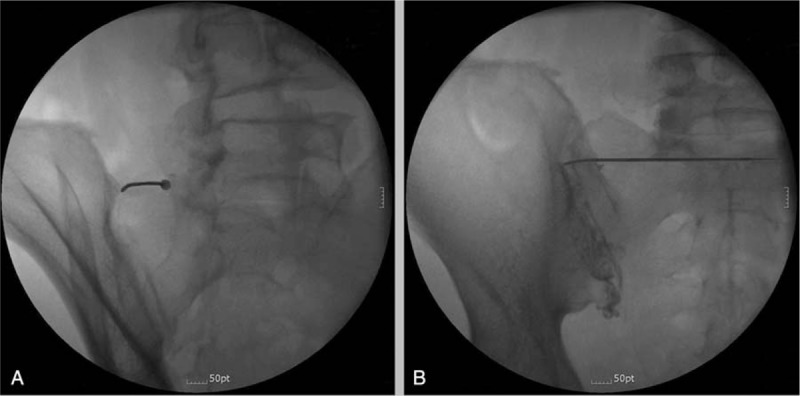

Aseptic techniques were adopted for the IA PRF stimulation into the SIJ. For the procedure, the patient was placed in a prone position for C-arm fluoroscopy (Siemens) and a 22-gauge curved-tip cannula (SMK Pole needle, 100 mm with a 10 mm active tip, Cotop International BV, Amsterdam, Netherland) was placed into the SIJ (Fig. 1). For the insertion of the cannula into the SIJ, the method by Do et al[25] was used. The success rate of this method was previously studied in our department, and we observed that the intra-SIJ injections using this method were successful in all 24 patients.[25] The wedge shape formed by the medial border of the ilium and the lateral border of the sacral ala was targeted under C-arm fluoroscopy guidance in a 40° to 50° contralateral oblique view. Using a superior approach, a cannula aiming at the target area was positioned. The cannula was inserted through the guide needle into the target area and was slightly advanced laterally and caudally. After obtaining an antero-posterior projection, the needle was further advanced laterally and caudally until its tip entered the joint. Finally, the needle tip was placed at the superior part of SIJ. To confirm intra-articular access, an arthrogram of the SIJ was obtained by injecting 0.5 to 1 mL of contrast. Intra-articular access was succeeded in all 20 patients. The PRF treatment was administered at 5 Hz and a 5-ms pulsed width for 6 minutes at 55 V with the constraint that the electrode tip temperature did not exceed 42 °C.

Figure 1.

Fluoroscopy-guided intra-articular pulsed radiofrequency of the left sacroiliac joint (SIJ). A, Contralateral oblique view. A 22-gauge curved-tip cannula was inserted into the wedge shape and advanced laterally and inferiorly into the SIJ. B, Antero-posterior view shows an arthrogram of the SIJ after injection of contrast material.

2.3. Outcome measurements

Pain intensities were assessed by an NRS before PRF treatment, and at 1, 2, and 3 months after treatment. Successful treatment was defined as more than 50% reduction in the NRS score compared with the pretreatment NRS score.

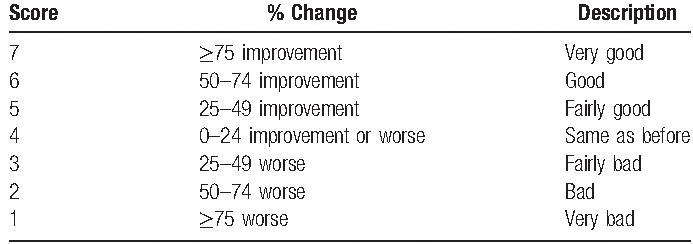

After 3 months, the patient global perceived effect (GPE) was assessed using a 7-point Likert scale (Table 2).[26,27] Patients reporting very good (score = 7) or good results (score = 6) were considered to be satisfied with the procedure. Outcome assessments were conducted by a third party who was unaware of the patient details. The patients were monitored during and after the PRF procedure for any adverse effects or complications.

Table 2.

Global perceived effect according to a Likert scale.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 23.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). The summary of characteristic variables was performed using descriptive analysis, with the mean ± standard deviation presented for quantitative variables and frequency (percent) for qualitative variables. The overall change in NRS scores over time was evaluated using a repeated measures one-factor analysis. Multiple comparison results were obtained with Bonferroni correction. A P value of less than .05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

3. Results

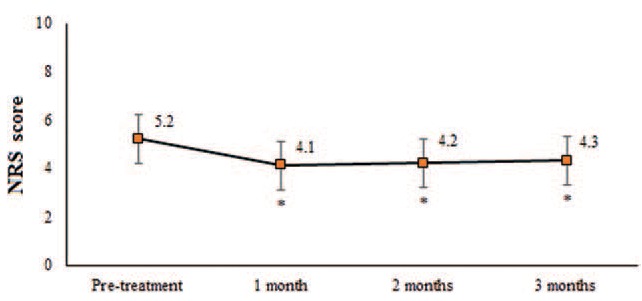

None of the patients had immediate or late adverse events after intra-SIJ PRF stimulation. Intra-SIJ access with a cannula was successful in all the patients. During and after the PRF procedure, there was no adverse effect or complication. The average NRS for the SIJ pain was 5.2 ± 0.9 at pretreatment, 4.1 ± 1.6 at 1 month, 4.2 ± 1.6 at 2 months, and 4.3 ± 1.5 at 3 months. The NRS scores significantly changed over time (P = .028) (Fig. 2). One, 2, and 3 months after PRF, the NRS scores were significantly reduced compared with the scores before PRF (pretreatment vs 1 month: P = .025, vs. 2 months: P = .029, vs. 3 months: P = .035). Four (20%) of the 20 patients reported successful pain relief (pain relief of ≥ 50%) at 3 months after PRF treatment.

Figure 2.

Changes in numeric rating scale (NRS) for sacroiliac joint pain during the assessment period. The NRS scores reduced from 5.2 prior to treatment to 4.1 at 1 month, 4.2 at 2 months, and 4.3 at 3 months after bipolar treatment. There were significant differences in the comparison between pretreatment and posttreatment values at 1, 2, and 3 months. ∗indicates significant results (P < .05).

On the 7-point Likert scale, very good results (score = 7) were seen in 2 patients (10%). Good (score = 6) and fairly good results (score = 5) were observed in 2 (10%) and 1 patients (5%), respectively. However, no change in results (score = 4) was observed in 15 patients (75%). Accordingly, 4 patients, accounting for 20% of all the included patients, were satisfied with the results at 3 months after the PRF procedure. Fairly bad (score = 3), bad (score = 2), and very bad (score = 1) results were not reported.

4. Discussion

We investigated the feasibility of IA PRF stimulation of the SIJ in 20 patients with chronic SIJ pain who were refractory to IA SIJ corticosteroid injection. The NRS scores were significantly changed over time after PRF. One, 2, and 3 months after PRF, the NRS scores were significantly reduced, compared with the pretreatment scores. However, of the 20 patients, only 4 patients (20%) showed good response (more than 50% pain reduction) and were satisfied with the treatment at 3 months after the procedure. The IA PRF of the SIJ was not effective in most patients (80%), and we could not find any changes in the NRS scores after PRF in 15 patients (75%). This result was contrary to our expectations.

The electrical field induced by the PRF electrode placed in the soft tissue is rapidly weakened at increasing distances from the electrode. However, because the bone has insulating properties, the current induced by IA PRF can be deflected by the bony surfaces and remain inside the joint space without weakening.[19] The residual current in the SIJ can inhibit excitability of pain-generating afferent nerves or free nerve endings that richly innervate the articular capsule. In addition, the electrical field from the low range of the spectrum is known to be able to influence the production of pro-inflammatory or inflammatory cytokines.[18] Several studies reported the reduction of serum C-reactive protein and cytokine levels after IA PRF.[18] On the basis of these theories, we supposed that IA PRF of the SIJ would inhibit the transfer of pain signals from nerves in the capsule of the SIJ and reduce the inflammatory process related to SIJ pain. However, 80% of our patients did not show a good response to this procedure. SIJ pain is usually caused by persisting abnormal joint movement and alignment, which make the SIJ hypermobile and loose.[3] If this condition persists, it can lead to continuous mechanical stimulation of the nociceptive nerves and repeated occurrence of inflammation in the SIJ. Thus, although previous studies reported that IA PRF stimulation is effective for controlling joint pain,[18,19] noncorrected abnormal joint movement and alignment in our patients are thought to have continuously produced SIJ pain.

Regarding IA PRF stimulation into SIJ, only 1 case study has been reported.[19] In 2008, Slujiter et al[19] reported successful treatment of SIJ pain with IA PRF stimulation (2 Hz and 10 ms pulsed width for 10 minutes at 65 V), they described a case of a patient whose pain did not respond to NSAIDs and physiotherapy or IA SIJ corticosteroid injection. Therefore, this is the first original study to investigate the effect of IA PRF in a large number of consecutive patients with chronic SIJ pain which was unresponsive to IA SIJ corticosteroid injection.

In addition, in some previous studies, PRF or CRF was conducted on the nerves supplying to the SIJ to manage refractory SIJ pain.[17,28] In 2006, Vallejo et al[17] performed PRF on the medial branch of L4, posterior primary rami of L5, and lateral branches S1 and S2 in 22 patients with refractory SIJ pain. Approximately 70% of these patients experienced good pain relief following PRF. The duration of the PRF effect varied, ranging from 6 weeks to 32 weeks. Moreover, in the same year, Hegarty[28] performed CRF on the L5 dorsal root and the lateral branches of S1–4 in 11 patients who had refractory chronic SIJ pain, and about 50% reduction of long-term pain (at least 1 year) was achieved after the procedure. We think that the PRF stimulations in the previous studies were applied to a wide range by stimulating more than 4 lumbosacral nerve branches. In opposite to the previous studies, the method we used might have influenced a relatively small area nearby the catheter tip. Therefore, until the appropriate inclusion criteria and stimulation mode of IA PRF stimulation are clearly established, RF on the nerves supplying to the SIJ might be more appropriate to control chronic refractory SIJ pain.

In conclusion, our results suggest that clinical improvements with application of IA PRF into the SIJ as reflected in the NRS score are only minimal to small in patients with chronic SIJ pain refractory to IA SIJ corticosteroid injection. Although the NRS scores were significantly reduced after PRF, only 20% of patients showed good pain reduction and were satisfied with our procedure. We think it would be an insufficient rate for its application in patients with refractory SIJ pain in clinical practice. To make a clear decision on its clinical applicability, further studies on the effective mode of PRF stimulation, appropriate patient selection, and pain conditions that are most responsive to PRF are warranted. In addition, some limitations of this study should be considered. First, this study was retrospectively conducted without a control group. Second, a small number of subjects were recruited. Third, we did not assess the pain intensity in the different situations or positions, such as resting, walking, or standing. Fourth, we did not evaluate the functional outcome or quality of life. Further studies addressing these limitations are recommended.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CRF = continuous radiofrequency, GPE = global perceived effect, IA = intra-articular, NRS = numeric rating scale, PRF = pulsed radiofrequency, SIJ = sacroiliac joint.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Manchikanti L, Singh V, Pampati V, et al. Evaluation of the relative contributions of various structures in chronic low back pain. Pain Phys 2001;4:308–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Schwarzer AC, Aprill CN, Bogduk N. The sacroiliac joint in chronic low back pain. Spine 1995;20:31–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Dreyfuss P, Dryer S, Griffin J, et al. Positive sacroiliac screening tests in asymptomatic adults. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1994;19:1138–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Borowsky CD, Fagen G. Sources of sacroiliac region pain: Insights gained from a study comparing standard intra-articular injection with a technique combining intra- and peri-articular injection. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2008;89:2048–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hansen H, Manchikanti L, Simopoulos TT, et al. A systematic evaluation of the therapeutic effectiveness of sacroiliac joint interventions. Pain Phys 2012;15:E247–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hawkins J, Schofferman J. Serial therapeutic sacroiliac joint injections: a practice audit. Pain Med 2009;10:850–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Hansen HC, McKenzie-Brown AM, Cohen SP, et al. Sacroiliac joint interventions: a systematic review. Pain Phys 2007;10:165–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].McKenzie-Brown AM, Shah RV, Sehgal N, et al. A systematic review of sacroiliac joint interventions. Pain Physician 2005;8:115–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Sluijter ME. Pain in Europe, Barcelona. 2nd Annual Congress of the European Federation of IASP Chapters; 1997. Non-thermal Radiofrequency procedures in the treatment spinal pain; p. 326. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Choi GS, Ahn SH, Cho YW, et al. Long-term effect of pulsed radiofrequency on chronic cervical radicular pain refractory to repeated transforaminal epidural steroid injections. Pain Med 2012;13:368–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lee DG, Ahn SH, Lee J. Comparative effectivenesses of pulsed radiofrequency and transforaminal steroid injection for radicular pain due to disc herniation: a prospective randomized trial. J Korean Med Sci 2016;31:1324–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Vatansever D, Tekin I, Tuglu I, et al. A comparison of the neuroablative effects of conventional and pulsed radiofrequency techniques. Clin J Pain 2008;24:717–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Sluijter ME, Cosman ER, Rittmann WB, et al. The effects of pulsed radiofrequency fields applied to the dorsal root ganglion—a preliminary report. Pain Clin 1998;11:109–17. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Van Zundert J, de Louw AJ, Joosten EA, et al. Pulsed and continuous radiofrequency current adjacent to the cervical dorsal root ganglion of the rat induces late cellular activity in the dorsal horn. Anesthesiology 2005;102:125–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Park CH, Lee YW, Kim YC, et al. Treatment experience of pulsed radiofrequency under ultrasound guided to the trapezius muscle at myofascial pain syndrome -a case report. Korean J Pain 2012;25:52–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Schianchi PM. A new technique to treat facet joint pain with pulsed radiofrequency. Anesth Pain Med 2015;5:e21061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Vallejo R, Benyamin RM, Kramer J, et al. Pulsed radiofrequency denervation for the treatment of sacroiliac joint syndrome. Pain Med 2006;7:429–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Schianchi PM, Sluijter ME, Balogh SE. The treatment of joint pain with intra-articular pulsed radiofrequency. Anesth Pain Med 2013;3:250–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Sluijter ME, Teixeira A, Serra V, et al. Intra-articular application of pulsed radiofrequency for arthrogenic pain—report of six cases. Pain Pract 2008;8:57–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Szadek KM, van der Wurff P, van Tulder MW, et al. Diagnostic validity of criteria for sacroiliac joint pain: a systematic review. J Pain 2009;10:354–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Murakami E, Watanabe K, Kokubun S. Lumbogluteal pain originating from the sacroiliac joint and the effect of sacroiliac joint block. Seikei-Saigaigeka (Orthop Surg Traumatol) 1996;39:761–6. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Gaenslen FJ. Sacro-iliac arthrodesis: indications, authors technic and end-results. JAMA 1927;89:2031–5. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Patrick HT. Brachial neuritis and sciatica. JAMA 1917;69:2176–9. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Laslett M. Evidence-based diagnosis and treatment of the painful sacroiliac joint. J Man Manip Ther 2008;16:142–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Do KH, Ahn SH, Jones R, et al. A new sacroiliac joint injection technique and its short-term effect on chronic sacroiliac region pain. Pain Med 2016;17:1809–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Farrar JT, Young JP, Jr, LaMoreaux L, et al. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. Pain 2001;94:149–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].van Alphen A, Halfens R, Hasman A, et al. Likert or Rasch? Nothing is more applicable than good theory. J Adv Nurs 1994;20:196–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Hegarty D. Clinical outcome following radiofrequency denervation for refractory sacroiliac joint dysfunction using the simplicity III probe: a 12-month retrospective evaluation. Pain Phys 2016;19:E129–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]