Abstract

Background and study aims

Patients receiving antithrombotic drugs have a higher risk of postoperative bleeding and thromboembolic events related to endoscopic procedures. The aim of this study was to evaluate the relationship between various antithrombotic therapies and bleeding after gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) (post-ESD bleeding).

Patients and methods

Among 529 consecutive gastric ESD procedures (483 patients with 579 legions), 100 patients with 121 lesions who underwent 108 procedures were on antithrombotic therapy (group A) and 382 patients with 458 lesions who underwent 421 procedures were not on antithrombotic therapy (group B). The ratio of post-ESD bleeding between the two groups and the bleeding risk related to various antithrombotic therapies were investigated.

Results

Postoperative bleeding was more frequent in group A (11.1 %) than in group B (3.3 %). No thromboembolic events were reported in either group. Further investigation of antithrombotic therapies in group A demonstrated that various combinations of antithrombotic agents and heparin replacement were associated with a higher ratio of post-ESD bleeding. Multivariate analyses revealed that dual antiplatelet therapy (odds ratio [OR] 10.9, 95 % confidence interval [CI] 2.1 – 49.5; P = 0.005) and heparin replacement (OR 34.4, 95 %CI 9.4 – 133.2; P < 0.001) were associated with the increased risk of post-ESD bleeding. In patients on antiplatelet therapy, post-ESD bleeding tended to occur in the early postoperative period compared with patients on anticoagulant therapy.

Conclusions

It is necessary to be cautious regarding post-ESD bleeding in patients requiring antithrombotic therapy, especially patients receiving dual antiplatelet therapy and heparin replacement. A further prospective study with a large sample will be needed to confirm these findings.

Introduction

The incidence of ischemic heart disease and cerebrovascular disease has increased in Japan, with a higher proportion of patients requiring antithrombotic agents. Therefore, it has become more common to perform endoscopic procedures in patients on antithrombotic therapy. In this subset of patients, it is important to consider the potential for postoperative bleeding, and thromboembolic events that may be caused by discontinuation of antithrombotic agents 1 2 .

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is an extremely useful and effective treatment for early gastric cancer, primarily because it is a minimally invasive procedure for achieving curative resection 3 4 5 6 7 . In addition, although ESD has been established as an excellent method of treatment for superficial gastrointestinal neoplasms, the prevention and management of post-ESD adverse events are issues still to be resolved. Despite the convenience and noninvasiveness of ESD, postoperative bleeding is a frequent problem. Some studies indicate that proton-pump inhibitors can prevent postoperative bleeding, but postoperative bleeding remains a serious complication that occurs in a certain proportion of patients 8 9 10 11 .

In the 2005 version of the Japanese guidelines for endoscopic procedures (JGES2005), ESD is classified as a procedure with a high risk of hemorrhage but that discontinuation of antithrombotic therapy is recommended 12 . However, after reports suggesting that discontinuation of antithrombotic therapy causes serious thromboembolic events 13 , the 2012 version of the Japanese guidelines (JGES2012) states that antiplatelet agents should only be discontinued in patients at a low risk of thromboembolism. Patients with a high risk of thromboembolism should undergo ESD while receiving antiplatelet agents or a replacement anticoagulant such as heparin 14 . Similarly, the 2009 version of the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) guidelines on the management of antithrombotic agents for endoscopic procedures recommends that low-dose aspirin (LDA) be continued for gastrointestinal endoscopies, even for procedures with a high risk of hemorrhage 15 . Tentative guidelines concerning the continuation and cessation of antithrombotic agents during endoscopy have been published from several societies, including the Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society, ASGE, and the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 16 17 18 .

There are concerns that procedures with a high risk of postoperative bleeding will be associated with a higher incidence of bleeding events after the 2012 guideline revisions. However, whereas few reports have evaluated the safety of antithrombotic therapy in high-risk procedures such as ESD before the revision of the JGES2012 guideline 19 20 , several reports have evaluated the safety after the revision of the guideline 21 22 23 . For example, Igarashi et al. 21 reported that the delayed bleeding rate associated with gastric ESD was significantly higher in patients receiving antithrombotic therapy than in those not receiving such therapy; this included procedures under both cessation and continuation of antiplatelet agents. But there has not been a detailed investigation of a correlation between the risk of post-ESD bleeding and various antithrombotic therapies. In particular, there are few reports on ESD procedures performed under the cessation of antithrombotic agents in a group of patients at low risk for thromboembolism, which was recommended in the JGES2012. Additionally, the risks associated with heparin replacement compared with cessation of antithrombotic therapy has not been sufficiently evaluated. To safely manage and evaluate the bleeding risk of high-risk procedures under the revised guidelines, additional reports are needed. This study was conducted to investigate the correlations between various antithrombotic therapies, post-ESD bleeding, and thromboembolic events in patients who underwent gastric ESD with drug cessation based on the JGES2005 guideline. The results will be used as contributory material for the management of patients undergoing high-risk procedures after the 2012 guideline revisions.

Patients and methods

Patients

This study included 529 consecutive ESD procedures (483 patients) for 579 early gastric neoplasms at Okayama University Hospital (Okayama, Japan) between October 2009 and February 2014. Among the 529 procedures, 108 (20.0 %) were in patients receiving antithrombotic therapy.

Based on the expanded criteria proposed by Gotoda et al. 24 , ESD was considered as a treatment option for lesions with a preoperative diagnosis of gastric adenoma or possible node-negative early gastric cancer.

The study was approved by the Clinical Ethics Committee on Human Experiments of Okayama University School of Medicine in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to sample collection.

Study design

The relationship between post-ESD bleeding and various antithrombotic therapies was examined. Patients were divided into two groups according to antithrombotic therapy at baseline: the antithrombotic group comprising 108 procedures, 100 patients, and 121 lesions (group A); and the non-antithrombotic group comprising 421 procedures, 382 patients, and 458 lesions (group B). The ratio of post-ESD bleeding between the two groups and the bleeding risk of various antithrombotic therapies were investigated. All patient data were obtained from the electronic medical record.

Post-ESD bleeding was defined as hematemesis, melena, a decline in hemoglobin levels of ≥ 2 g/dL, or the requirement for hemostasis because of bleeding post-ESD ulcers on second-look (Day 1) or third-look (Day 7) endoscopy. Preventive hemostasis for visible vessels without the clinical criterion of bleeding on second-look and third-look endoscopy was not included in post-ESD bleeding.

Further data on patient characteristics and post-ESD bleeding were used as background factors. Age, sex, the location and size of tumors, and the presence of the following chronic concomitant disorders were recorded: cardiovascular disease, renal failure, neurological disease, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus.

Antithrombotic agents were classified into antiplatelet agents (aspirin, cilostazol, ticlopidine, clopidogrel, icosapentate, sarpogrelate hydrochloride, beraprost sodium, limaprost alfadex, and dipyridamole) and anticoagulants (warfarin and dabigatran). Both types of antithrombotic agent were classified as risk factors for bleeding. According to the JGES2012 criteria 14 , a high risk of thromboembolism was defined as any of the following: 1) coronary artery bare-metal stenting in the previous 2 months; 2) coronary artery drug-eluting stenting in the previous 12 months; 3) carotid artery revascularization in the previous 2 months; 4) a history of ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack with > 50 % stenosis of the major intracranial arteries; 5) recent ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack; 6) obstructive peripheral artery disease at least Fontaine grade 3; 7) ultrasonic examination of carotid arteries and magnetic resonance angiography of the head and neck region indicating that withdrawal of antithrombotic therapy is associated with a high risk of thromboembolism; 8) a history of cardiogenic brain embolism; 9) atrial fibrillation with valvular heart disease; 10) atrial fibrillation without valvular heart disease, but with a high risk of stroke; 11) previous mechanical mitral valve replacement; 12) history of thromboembolism following mechanical valve replacement; 13) antiphospholipid antibody syndrome; and, 14) deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary thromboembolism. All other factors present were defined as providing a low risk.

Protocol for ESD

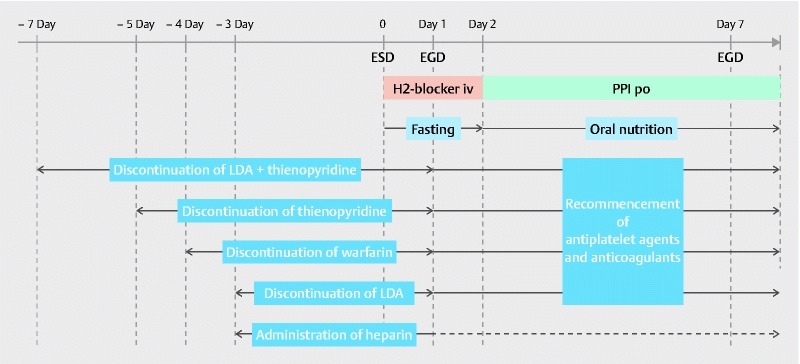

Supplementary Fig. 1 shows the protocol for the ESD procedure, including the management of various antithrombotic therapies.

Supplementary Fig. 1.

Protocol for endoscopic submucosal dissection. The protocol for ESD procedure including the management of various antithrombotic therapies is shown. ESD, endoscopic submucosal dissection; EGD, esophagogastroduodenoscopy; PPI, proton-pump inhibitor; LDA, low-dose aspirin.

For patients receiving antithrombotic therapy, the prescribing doctor was consulted before ESD. Drug cessation periods before the ESD procedure were based on the JGES2005 guideline: 3 days for LDA, 2 days for cilostazol, 5 days for thienopyridine derivatives, 7 days for the combination of aspirin with a thienopyridine derivative, and 1 day for other antiplatelet agents. Warfarin was discontinued 4 days before ESD, and dabigatran was discontinued 1 day before ESD. All patients considered by the prescribing doctor to be at a high risk of thromboembolism received heparin replacement. Unfractionated heparin was administered to maintain an activated partial thromboplastin time of approximately 60 seconds, and was discontinued 4 – 6 hours before ESD. The prothrombin time-international normalized ratio (PT-INR) was measured before ESD to confirm that the effects of antithrombotic drugs had disappeared. On Day 1 after ESD, heparin was re-administered following confirmation of the absence of symptomatic gastrointestinal bleeding or a decline in hemoglobin levels. All other antithrombotic agents were re-initiated on Day 1 after ESD in cases with no evidence of bleeding. PT-INR monitoring for warfarin was initiated after ESD, and heparin sodium was discontinued when the PT-INR was > 1.50. Heparin sodium was also discontinued when dabigatran was administered on Day 1 after ESD and no evidence of bleeding was observed.

Irrespective of antithrombotic therapy, all patients were required to fast from the day of the endoscopic procedure until post-ESD Day 1. Providing that complications such as post-ESD bleeding or perforation were not observed on second-look endoscopy, a liquid diet was started on Day 2. Intravenous H 2 blocker therapy was commenced immediately after ESD until Day 1. Oral proton pump inhibitors were administered from Day 2 to 8 weeks after ESD. Third-look endoscopy was performed on Day 7, and fourth-look endoscopy was performed at 8 weeks after ESD. All patients were systematically provided with second-look endoscopy and third-look endoscopy in the study. The hemoglobin levels were checked on Day 1 and Day 7 after ESD. If a clinical episode of hematemesis and/or melena, and/or a decline in hemoglobin levels of ≥ 2 g/dL occurred, emergency endoscopy was performed.

ESD procedure

ESD was performed using a conventional single-channel endoscope (GIF-H260Z or -Q260J; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) or a two-channel endoscope (2TQ260 M; Olympus). ESD for gastric neoplasms was performed using a dual knife (KD-650 L/Q; Olympus Optical Co., Tokyo, Japan) for marking and precutting, an insulated-tipped (IT) knife (Olympus) for circumferential mucosal incision, and an IT knife for submucosal resection. A mixture of glycerol (10 % glycerol and 5 % fructose; Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Tokyo, Japan) with small amounts of epinephrine and indigo carmine was injected into the submucosal layer to lift the mucosa. High-frequency generators (ICC200 or VIO 300D; ERBE Elektromedizin GmbH, Tübingen, Germany) were used during marking, incision of the gastric mucosa, and exfoliation of the gastric submucosa.

After lesion resection, all visible vessels on the ulcer floor were coagulated with hemostatic forceps (FD-411UR, Coagrasper; Olympus) and hot biopsy forceps (Hoya Co., Ltd., Pentax Life Care Div., Tokyo, Japan) and VIO 300 D (swift coagulation, effect 3, 45 W) or ICC 200 (forced coagulation, 65 W). All procedures were performed by board-certified endoscopists.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as the median and range or interquartile range (IQR). Continuous variables were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test, and dichotomous variables were compared using Fisher’s exact test and logistic regression. To extract significant factors for post-ESD bleeding events, these variables with P < 0.05 on univariate analysis were examined using multivariate logistic regression models. For additional variable selection, backward stepwise selection ( P = 0.15 as the level for including variables, and P = 0.10 for exclusion of variables) was used. P values of < 0.05 were considered to denote a statistically significant difference between groups. Data were evaluated using JMP software version 11 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

Table1 summarizes the baseline characteristics, gastric lesions, procedural time, and adverse events in all patients, group A patients (antithrombotic therapy), and group B patients (no antithrombotic therapy). Group A patients were older (median 77.0 years; IQR 71.0 – 80.0) than group B patients (median 71.0 years; IQR 64.0 – 78.0; P < 0.001), and had a higher incidence of chronic concomitant diseases (cardiovascular disease, renal failure, neurological disease, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus; P < 0.005 for each disease). In group A, the majority of procedures (81.5 %) had low thromboembolic risk. No thromboembolic events were reported in either group. However, the postoperative bleeding rate was higher in group A (11.1 %) than group B (3.3 %; P = 0.002).

Table 1. Characteristics of patients and gastric lesions, and procedural outcomes.

| Total | Group A | Group B | P value | |

| Procedures (patients), n | 529 (483) | 108 (100) | 421 (382) | |

| Age, median (IQR), years | 75.0 (68.8 – 81.0) | 77.0 (71.0 – 80.0) | 71.0 (64.0 – 78.0) | < 0.001 |

| Sex (male/female), n | 410/119 | 92/16 | 318/103 | 0.026 |

| Chronic concomitant diseases, n (%) | ||||

|

74 (13.9) | 48 (44.4) | 26 (6.2) | < 0.001 |

|

21 (3.9) | 10 (9.2) | 11 (2.6) | 0.004 |

|

44 (8.3) | 36 (33.3) | 8 (1.9) | < 0.001 |

|

187 (35.3) | 53 (49.1) | 134 (31.8) | 0.001 |

|

92 (17.4) | 35 (32.4) | 57 (13.5) | < 0.001 |

| Risk of thromboembolism, n (%) | ||||

|

20 (18.5) | 20 (18.5) | 0 | |

|

88 (81.5) | 88 (81.5) | 0 | < 0.001 |

| Adverse events after ESD, n (%) | ||||

|

26 (4.9) | 12 (11.1) | 14 (3.3) | 0.002 |

|

33 (6.2) | 7 (6.5) | 26 (6.2) | 0.83 |

|

0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ― |

| Procedure time, median (IQR), minutes | 65.0 (40.0 – 100.0) | 70.0 (50.0 – 112.5) | 60.0 (40.0 – 100.0) | 0.19 |

| Number of lesions, n | 579 | 121 | 458 | |

| Vertical location, n (%) | ||||

|

95 (16.4) | 21 (17.4) | 74 (16.2) | |

|

284 (49.1) | 59 (48.7) | 225 (49.1) | |

|

200 (34.5) | 41 (33.9) | 159 (34.7) | 0.95 |

| Lesion size, median (IQR), mm | 13.0 (8.0 – 22.0) | 13.0 (9.5 – 21.0) | 13.0 (7.0 – 22.0) | 0.45 |

IQR, interquartile range; ESD, endoscopic submucosal dissection

Table 2 shows the types of antithrombotic therapy and the postoperative bleeding incidence ratio for the 108 procedures in group A. Antiplatelet agents and anticoagulants were administered to 103 patients and 25 patients, respectively. Postoperative bleeding occurred in 12 of the 108 procedures (11.1 %). The only single-agent antithrombotic therapy that correlated with a high ratio of postoperative bleeding incidence was warfarin (21.4 %). With respect to dual-agent antithrombotic therapy, a high bleeding incidence ratio was observed for dual antiplatelet therapy (31.3 %), in particular, thienopyridine with aspirin (80.0 %), and for warfarin with aspirin (50.0 %).

Table 2. Incidence ratio of postoperative bleeding according to antithrombotic treatment in patients receiving antithrombotic therapy (group A).

| Number of procedures, n | Incidence of postoperative bleeding, n (% of incidence ratio) | |

| Antithrombotic agent | 108 | 12 (11.1) |

| Single antiplatelet agent | 72 | 3 (4.2) |

|

35 | 2 (5.7) |

|

10 | 0 (0.0) |

|

27 | 1 (3.7) |

| Single anticoagulant | 14 | 3 (21.4) |

|

14 | 3 (21.4) |

| Dual antiplatelet therapy | 16 | 5 (31.3) |

|

5 | 4 (80.0) |

|

9 | 1 (11.1) |

|

2 | 0 (0.0) |

| Antiplatelet agent and anticoagulant | 6 | 1 (16.6) |

|

2 | 1 (50.0) |

|

3 | 0 (0.0) |

|

1 | 0 (0.0) |

As to the incidence of postoperative bleeding in group A and group B patients, there were 15 patients with hematemesis or melena (group A 8/12, 66.7 %; group B 7/14, 50.0 %), 15 patients with decreases in hemoglobin levels of ≥ 2 g/dL (group A 8/12, 66.7 %; group B 7/14, 50.0 %), and 26 patients who required hemostasis because of bleeding post-ESD ulcers on second-look (Day 1) or third-look (Day 7) endoscopy (group A 12/12, 100 %; group B 14/14, 100 %). Table 3 displays the postoperative bleeding incidence ratio for lesions according to antithrombotic therapy at baseline and post-ESD classified by heparin replacement status in group A patients. The postoperative bleeding incidence was generally low (6.5 %) in cases without heparin replacement. However, a high postoperative bleeding incidence ratio was observed for dual antiplatelet therapy (43.8 %), primarily aspirin with thienopyridine (80.0 %). Heparin replacement was also associated with a high postoperative bleeding incidence (37.5 %). Although the statistical significance is limited because of the small sample size, both single antiplatelet therapy (100 %) and single warfarin therapy (33.3 %) had a high postoperative bleeding incidence ratio.

Table 3. Incidence ratio of postoperative bleeding according to antithrombotic treatment stratified by heparin replacement in patients receiving antithrombotic therapy (group A).

| Number of procedures, n | Incidence of postoperative bleeding, n (% of incidence ratio) | |

| Antithrombotic agent | 108 | 12 (11.1) |

| Without heparin replacement | 92 | 6 (6.5) |

| Single antiplatelet agent | 70 | 1 (1.4) |

|

33 | 0 (0.0) |

|

10 | 0 (0.0) |

|

27 | 1 (3.7) |

| Single anticoagulant | 5 | 0 (0.0) |

|

5 | 0 (0.0) |

| Dual antiplatelet therapy | 16 | 5 (43.8) |

|

5 | 4 (80.0) |

|

9 | 1 (11.1) |

|

2 | 0 (0.0) |

| Antiplatelet agents and anticoagulant | 1 | 0 (0.0) |

|

1 | 0 (0.0) |

| With heparin replacement | 16 | 6 (37.5) |

| Single antiplatelet agent | 2 | 2 (100.0) |

|

2 | 2 (100.0) |

| Single anticoagulant | 9 | 3 (33.3) |

|

9 | 3 (33.3) |

| Antiplatelet agent and anticoagulant | 5 | 1 (20.0) |

|

2 | 1 (50.0) |

|

2 | 0 (0.0) |

|

1 | 0 (0.0) |

In univariate analysis, an increased risk of post-ESD bleeding was associated with aspirin (odds ratio [OR] 4.8, 95 % confidence interval [CI] 1.9 – 11.3), thienopyridine (OR 6.9, 95 %CI 1.8 – 21.3), anticoagulants (OR 5.5, 95 %CI 1.5 – 16.6), dual antiplatelet therapy (OR 10.6, 95 %CI 3.1 – 32.3), heparin replacement (OR 14.8, 95 %CI 4.6 – 44.1), cardiovascular disease (OR 4.3, 95 %CI 1.8 – 9.7), and diabetes mellitus (OR 2.8, 95 %CI 1.1 – 6.3). Multivariate analyses revealed that dual antiplatelet therapy (OR 10.9, 95 %CI 2.1 – 49.5), and heparin replacement (OR 34.4, 95 %CI 9.4 – 133.2) correlated with an increased risk of post-ESD bleeding. Higher age (age > 75 years: OR 0.2, 95 %CI 0.06 – 0.6) decreased the risk ( Table 4 ).

Table 4. Univariate and multivariate regression analysis of risk factors for bleeding after endoscopic submucosal dissection.

| Factor | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

| OR (95 %CI) | P value | OR (95 %CI) | P value | |

| Age (> 75 years) | 0.4 (0.1 – 0.9) | 0.037 | 0.2 (0.06 – 0.6) | 0.001 |

| Sex (male) | 1.2 (0.5 – 3.8) | 0.68 | ||

| Location of maximum legion (L/U,M) | 1.9 (0.9 – 4.4) | 0.09 | ||

| Maximum lesion size (> 20 mm) | 2.1 (0.9 – 4.6) | 0.07 | ||

| More than 2 legions | 1.5 (0.3 – 4.6) | 0.53 | ||

| Aspirin | 4.8 (1.9 – 11.3) | 0.002 | ||

| Thienopyridine | 6.9 (1.8 – 21.3) | 0.007 | 4.4 (0.7 – 22.5) | 0.11 |

| Other antiplatelet agents | 1.0 (0.2 – 3.4) | 0.96 | ||

| Anticoagulants | 5.5 (1.5 – 16.6) | 0.014 | ||

| Dual antiplatelet therapy | 10.6 (3.1 – 32.3) | 0.001 | 10.9 (2.1 – 49.5) | 0.005 |

| Heparin replacement | 14.8 (4.6 – 44.1) | < 0.001 | 34.4 (9.4 – 133.2) | < 0.001 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 4.3(1.8 – 9.7) | 0.001 | ||

| Chronic renal disease | 3.3 (0.7 – 10.6) | 0.10 | ||

| Neurological disease | 1.5 (0.3 – 4.6) | 0.53 | ||

| Hypertension | 1.2 (0.5 – 2.6) | 0.70 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 2.8 (1.1 – 6.3) | 0.026 | ||

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; U, upper; M, middle; L, Lower.

The periods of postoperative bleeding are shown in Table 5 . In patients on antiplatelet therapy, post-ESD bleeding occurred in the early postoperative period (median 1 day; range 1 – 7 days), whereas patients on anticoagulant therapy bleeding occurred in the later postoperative period (median 7 days; range 1 – 10 days). There were statistically significant differences between antiplatelet therapy and anticoagulant therapy in the periods of post-ESD bleeding ( P = 0.022) ( Table 6 ).

Table 5. Periods of postoperative bleeding in patients receiving antithrombotic therapy (group A).

| Day | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Without heparin replacement, n | ||||||||||

|

1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| With heparin replacement, n | ||||||||||

|

2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

|

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Table 6. Comparison of periods of postoperative bleeding between antiplatelet therapy and anticoagulant therapy.

| Antiplatelet therapy | Anticoagulant therapy | P value | |

| Number of patients | 8 | 4 | |

| Periods of postoperative bleeding, median (range), days | 1 (1 – 7) | 7 (1 – 10) | 0.022 |

Discussion

In this study, patients who underwent ESD with antithrombotic therapy (group A) and were managed based on the JGES2005 guideline were compared with patients not receiving antithrombotic therapy (group B). The post-ESD bleeding rate was higher in group A than group B. Further investigation for antithrombotic therapies in group A demonstrated that various combinations of antithrombotic agents and heparin replacement were associated with a higher ratio of post-ESD bleeding. Multivariate analysis demonstrated that both dual antiplatelet therapy and heparin replacement significantly increased the risk of post-ESD bleeding. Post-ESD bleeding occurred at an earlier time among patients on antiplatelet therapy than in those on anticoagulant therapy. Previously, some studies have reported on the relationship between antithrombotic therapy and bleeding after gastric ESD 22 23 25 26 27 . However, detailed evaluations under unified guidelines, including multivariate analyses and the periods of events concerning the various type of antithrombotic therapy, are lacking.

In the present study, we evaluated the ratio of bleeding events with detailed stratification according to antithrombotic agents used and heparin replacement. This detailed stratification revealed that the ratio of bleeding events under cessation of antithrombotic agents were quite different according to the combination of antithrombotic agents or whether heparin replacement was provided. Some studies have indicated that the bleeding risk for patients receiving single antiplatelet therapy was not substantially altered by either discontinuation or continuous administration relative to patients without antithrombotic therapy 19 21 28 . But few studies have reported the results of a detailed stratification of bleeding events according to antithrombotic agents under certain protocols regarding cessation of antithrombotic agents 21 22 23 . The JGES2012 noted that in a low thromboembolism risk group, procedures that present a high risk of bleeding are recommended to be done under cessation of antithrombotic agents. Additionally, the guidelines suggest that patients receiving single antiplatelet therapy included a high ratio of those at low risk of thromboembolism. Therefore, a carefully stratified analysis of antithrombotic agents under cessation is important. In this study, Table 3 clearly shows that patients receiving single antithrombotic therapy (i. e. an antiplatelet or an anticoagulant) without heparin replacement had a low rate of post-ESD bleeding. In contrast, the bleeding risk after resuming treatment was very high among patients requiring two or more antiplatelet agents. These finding are in accordance with previous findings 19 . Additionally, post-ESD bleeding was frequent among patients who received heparin replacement with a single antiplatelet or single anticoagulant agent. In comparison with the low incidence ratio of bleeding events in patients under cessation of a single antiplatelet or anticoagulant agent, the effect of heparin replacement was shown clearly. Previous studies have indicated that heparin replacement does not reduce the incidence of thromboembolism under warfarin therapy despite the frequencies of post-ESD bleeding being significantly higher with heparin replacement than without heparin replacement 22 23 29 30 31 . These data lead to the suggestion that heparin replacement may not be appropriate for perioperative management. Multivariate analysis demonstrated that both dual antiplatelet therapy and heparin replacement significantly increased the risk of post-ESD bleeding, which supports the results of the stratified analysis shown in Table 3 and the results of previous reports that showed a higher odds ratio.

With respect to the periods of post-ESD bleeding, in a retrospective study of 454 gastric ESD cases under cessation of antithrombotic therapy, the median was 2 days post-ESD (range 0 – 14 days) 20 . However, the incidence and periods of bleeding by drug type were not examined. In addition, the periods of post-ESD bleeding in cases of gastric ESD with heparin replacement were not reported. In our study, post-ESD bleeding of patients on anticoagulant therapy tended to be observed in the later postoperative period compared with patients on antiplatelet therapy. Warfarin was resumed on postoperative Day 2; therefore, it is considered that post-ESD bleeding may be explained by the effects of warfarin reaching the therapeutic range under heparin replacement. There were no bleeding-related mortalities or cases that required emergency surgery for post-ESD bleeding in the present study. The effects of aspirin last for the duration of the life of the platelet (i. e. 10 days). In addition, platelet adenosine diphosphate receptor inhibitors such as ticlopidine and clopidogrel are more potent antiplatelet drugs than aspirin but have a half-life similar to aspirin, about 5 – 10 days. Therefore, most patients on antiplatelet therapy might have post-ESD bleeding a day after ESD regardless of cessation of the drugs. Six patients (six procedures) had post-ESD bleeding that required blood transfusion (group A 4/108, 3.7 %; group B 2/421, 0.5 %), but there were no bleeding-related mortalities or cases that required emergency surgery for post-ESD bleeding in the present study.

A few retrospective studies have reported that no cases of thromboembolism occurred after discontinuation of antithrombotic therapy for 1 week prior to gastric ESD 32 33 34 . Similarly, none of the patients in the present study developed thromboembolism during discontinuation of antithrombotic therapy. However, prolonged drug cessation will undoubtedly increase the risk of thromboembolism. It is thought that patients have a 3-fold higher risk of cardiovascular events and cerebral infarction during discontinuation of LDA, and there are reports describing the development of cerebral infarction within 10 days after LDA cessation, and that these accounted for 70 % of all cerebral infarctions 35 36 . Estimates suggest that one case of thromboembolism occurs per 100 cases of warfarin cessation, and these cases tend to be serious and have a poor prognosis 37 38 . Results of the ORBIT-AF study conducted in the United States demonstrated that the incidences of both thromboembolism and post-ESD bleeding were significantly higher in patients receiving warfarin and heparin replacement compared with those not receiving warfarin and heparin replacement 29 . Thus, it is necessary to be aware of the risk of thromboembolic events during the drug cessation period.

Therefore, as described in the JGES2012 guidelines, substitution of antiplatelet agents with cilostazol and a 1-day drug cessation period is thought to be sufficient to prevent severe thromboembolism as well as post-ESD bleeding. Data from this study suggest that substitution for the combination of aspirin with thienopyridine derivatives requires longer treatment periods, if possible, before and after the ESD procedure to prevent a bleeding event. Fukuda et al. 39 reported that the use of an absorbable polyglycolic acid suture (Neoveil; Gunze Ltd., Kyoto, Japan) may reduce post-ESD bleeding. Among patients receiving an anticoagulant agent, it is desirable to change to direct oral anticoagulants (e. g. apixaban, rivaroxaban, and edoxaban) plus heparin replacement therapy. A growing body of evidence suggests that switching to direct oral anticoagulants or LDA monotherapy is preferable, as recommended in the JGES2012 guidelines 14 .

This study has some limitations. First, it is a single-center and retrospective observational study. Selection bias in conducting ESD may exist between the two groups with or without antithrombotic therapy. However, bias was minimized by accumulating consecutive cases with the same protocol, and backgrounds between the two groups, including tumor characteristics, which might affect bleeding risk, were similar. Second, the sample size of patients requiring antithrombotic therapy was small, and trials with a larger sample size are warranted. Third, no thromboembolic events developed during discontinuation of antithrombotic therapy, probably because there was a very low number of high-risk thrombosis cases. Nevertheless, the results suggest that cessation of antithrombotic agents is appropriate in low-risk thromboembolism cases.

In conclusion, the findings of this study suggest that it is necessary to be aware of the possibility of post-ESD bleeding, even after discontinuation of antithrombotic agents. In particular, patients receiving dual antiplatelet agents and heparin replacement require increased attention for post-ESD bleeding. In order to confirm the procedures for strict management according to the level of bleeding risk in patients receiving different antithrombotic therapies, further prospective studies with large samples will be needed.

Footnotes

Competing interests None

References

- 1.Bhatt D L, Scheiman J, Abraham N S et al. ACCF/ACG/AHA 2008 expert consensus document on reducing the gastrointestinal risks of antiplatelet therapy and NSAID use: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents. Circulation. 2008;118:1894–1909. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.191087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Becker R C, Scheiman J, Dauerman H L et al. Management of platelet-directed pharmacotherapy in patients with atherosclerotic coronary artery disease undergoing elective endoscopic gastrointestinal procedures. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:2261–2276. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ono H, Kondo H, Gotoda T et al. Endoscopic mucosal resection for treatment of early gastric cancer. Gut. 2001;48:225–229. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.2.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abe N, Yamaguchi Y, Takeuchi H et al. Key factors for successful en bloc endoscopic submucosal dissection of early stage gastric cancer using an insulation-tipped diathermic knife. Hepatogastroenterology. 2006;53:639–642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oda I, Saito D, Tada M et al. A multicenter retrospective study of endoscopic resection for early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2006;9:262–270. doi: 10.1007/s10120-006-0389-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gotoda T. Endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2007;10:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10120-006-0408-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim B J, Chang T H, Kim J J et al. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer in patients with comorbid diseases. Gut Liver. 2010;4:186–191. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2010.4.2.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uedo N, Takeuchi Y, Yamada T et al. Effect of a proton pump inhibitor or an H2-receptor antagonist on prevention of bleeding from ulcer after endoscopic submucosal dissection of early gastric cancer: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1610–1616. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang Z, Wu Q, Liu Z et al. Proton pump inhibitors versus histamine-2-receptor antagonists for the management of iatrogenic gastric ulcer after endoscopic mucosal resection or endoscopic submucosal dissection: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Digestion. 2011;84:315–320. doi: 10.1159/000331138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ono H, Yao K, Fujishiro M et al. Guidelines for endoscopic submucosal dissection and endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer. Dig Endosc. 2016;28:3–15. doi: 10.1111/den.12518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kataoka Y, Tsuji Y, Sakaguchi Y et al. Bleeding after endoscopic submucosal dissection: Risk factors and preventive methods. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:5927–5935. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i26.5927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ogoshi K, Kaneko E, Tada M. The management of anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy for endoscopic procedures. Gastroenterological Endoscopy [in Japanese] 2005;47:2691–2695. [Google Scholar]

- 13.[Anonymous]Risk factors for stroke and efficacy of antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation. Analysis of pooled data from five randomized controlled trials Arch Intern Med 19941541449–1457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujimoto K, Fujishiro M, Katou M et al. The management of anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy for endoscopic procedures. Gastroenterological Endoscopy [in Japanese] 2012;54:2075–2102. [Google Scholar]

- 15.ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Anderson M A, Ben-Menachem T et al. Management of antithrombotic agents for endoscopic procedures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:1060–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fujimoto K, Fujishiro M, Kato M et al. Guidelines for gastroenterological endoscopy in patients undergoing antithrombotic treatment. Dig Endosc. 2014;26:1–14. doi: 10.1111/den.12183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Veitch A M, Vanbiervliet G, Gershlick A H et al. Endoscopy in patients on antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy, including direct oral anticoagulants: British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) and European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guidelines. Endoscopy. 2016;48:c1. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-122686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Acosta R D, Abraham N S et al. The management of antithrombotic agents for patients undergoing GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:3–16. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tounou S, Morita Y. Gastric and duodenal endoscopic submucosal dissection in patients on aspirin therapy has increased risk of hemorrhage but is feasible. Gastroenterological Endoscopy[in japanese] 2011;53:3326–3335. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goto O, Fujishiro M, Kodashima S et al. A second-look endoscopy after endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric epithelial neoplasm may be unnecessary: a retrospective analysis of postendoscopic submucosal dissection bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:241–248. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Igarashi K, Takizawa K, Kakushima N et al. Should antithrombotic therapy be stopped in patients undergoing gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection? Surg Endosc. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s00464-016-5167-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shindo Y, Matsumoto S, Miyatani H et al. Risk factors for postoperative bleeding after gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection in patients under antithrombotics. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;8:349–356. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v8.i7.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Furuhata T, Kaise M, Hoteya S et al. Postoperative bleeding after gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection in patients receiving antithrombotic therapy. Gastric Cancer. 2017;20:207–214. doi: 10.1007/s10120-015-0588-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gotoda T, Yanagisawa A, Sasako M et al. Incidence of lymph node metastasis from early gastric cancer: estimation with a large number of cases at two large centers. Gastric Cancer. 2000;3:219–225. doi: 10.1007/pl00011720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takeuchi T, Ota K, Harada S et al. The postoperative bleeding rate and its risk factors in patients on antithrombotic therapy who undergo gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13:136. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-13-136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsumura T, Arai M, Maruoka D et al. Risk factors for early and delayed post-operative bleeding after endoscopic submucosal dissection of gastric neoplasms, including patients with continued use of antithrombotic agents. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14:172. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-14-172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cho S J, Choi I J, Kim C G et al. Aspirin use and bleeding risk after endoscopic submucosal dissection in patients with gastric neoplasms. Endoscopy. 2012;44:114–121. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1291459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lim J H, Kim S G, Kim J W et al. Do antiplatelets increase the risk of bleeding after endoscopic submucosal dissection of gastric neoplasms? Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:719–727. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steinberg B A, Peterson E D, Kim S et al. Use and outcomes associated with bridging during anticoagulation interruptions in patients with atrial fibrillation: findings from the Outcomes Registry for Better Informed Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation (ORBIT-AF) Circulation. 2015;131:488–494. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.011777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Douketis J D, Spyropoulos A C, Kaatz S et al. Perioperative bridging anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:823–833. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1501035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoshio T, Nishida T, Hayashi Y et al. Clinical problems with antithrombotic therapy for endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric neoplasms. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;8:756–762. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v8.i20.756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mannen K, Tsunada S, Hara M et al. Risk factors for complications of endoscopic submucosal dissection in gastric tumors: analysis of 478 lesions. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:30–36. doi: 10.1007/s00535-009-0137-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okada K, Yamamoto Y, Kasuga A et al. Risk factors for delayed bleeding after endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric neoplasm. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:98–107. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1137-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ono S, Fujishiro M, Niimi K et al. Technical feasibility of endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer in patients taking anti-coagulants or anti-platelet agents. Dig Liver Dis. 2009;41:725–728. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sibon I, Orgogozo J M. Antiplatelet drug discontinuation is a risk factor for ischemic stroke. Neurology. 2004;62:1187–1189. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000118288.04483.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maulaz A B, Bezerra D C, Michel P et al. Effect of discontinuing aspirin therapy on the risk of brain ischemic stroke. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:1217–1220. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.8.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wahl M J. Dental surgery in anticoagulated patients. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1610–1616. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.15.1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blacker D J, Wijdicks E F, McClelland R L. Stroke risk in anticoagulated patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing endoscopy. Neurology. 2003;61:964–968. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000086817.54076.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fukuda H, Yamaguchi N, Isomoto H et al. Polyglycolic acid felt sealing method for prevention of bleeding related to endoscopic submucosal dissection in patients taking antithrombotic agents. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2016;2016:1.457357E6. doi: 10.1155/2016/1457357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]