Abstract

Background

PD-L1 and CTLA-4 immune checkpoints inhibit antitumour T-cell activity. Combination treatment with the anti-PD-L1 antibody durvalumab and the anti-CTLA-4 antibody tremelimumab might provide greater antitumour activity than either drug alone. We aimed to assess durvalumab plus tremelimumab in patients with advanced squamous or non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Methods

We did a multicentre, non-randomised, open-label, phase 1b study at five cancer centres in the USA. We enrolled immunotherapy-naïve patients aged 18 years or older with confirmed locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC. We gave patients durvalumab in doses of 3 mg/kg, 10 mg/kg, 15 mg/kg, or 20 mg/kg every 4 weeks, or 10 mg/kg every 2 weeks, and tremelimumab in doses of 1 mg/kg, 3 mg/kg, or 10 mg/kg every 4 weeks for six doses then every 12 weeks for three doses. The primary endpoint of the dose-escalation phase was safety. Safety analyses were based on the as-treated population. The dose-expansion phase of the study is ongoing. This study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT02000947.

Findings

Between Oct 28, 2013, and April 1, 2015, 102 patients were enrolled into the dose-escalation phase and received treatment. At the time of this analysis (June 1, 2015), median follow-up was 18.8 weeks (IQR 11–33). The maximum tolerated dose was exceeded in the cohort receiving durvalumab 20 mg/kg every 4 weeks plus tremelimumab 3 mg/kg, with two (30%) of six patients having a dose-limiting toxicity (one grade 3 increased aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase and one grade 4 increased lipase). The most frequent treatment-related grade 3 and 4 adverse events were diarrhoea (11 [11%]), colitis (nine [9%]), and increased lipase (eight [8%]). Discontinuations attributable to treatment-related adverse events occurred in 29 (28%) of 102 patients. Treatment-related serious adverse events occurred in 37 (36%) of 102 patients. 22 patients died during the study, and three deaths were related to treatment. The treatment-related deaths were due to complications arising from myasthenia gravis (durvalumab 10 mg/kg every 4 weeks plus tremelimumab 1 mg/kg), pericardial effusion (durvalumab 20 mg/kg every 4 weeks plus tremelimumab 1 mg/kg), and neuromuscular disorder (durvalumab 20 mg/kg every 4 weeks plus tremelimumab 3 mg/kg). Evidence of clinical activity was noted both in patients with PD-L1-positive tumours and in those with PD-L1-negative tumours. Investigator-reported confirmed objective responses were achieved by six (23%, 95% CI 9–44) of 26 patients in the combined tremelimumab 1 mg/kg cohort, comprising two (22%, 95% CI 3–60) of nine patients with PD-L1-positive tumours and four (29%, 95% CI 8–58) of 14 patients with PD-L1-negative tumours, including those with no PD-L1 staining (four [40%, 95% CI 12–74] of ten patients).

Interpretation

Durvalumab 20 mg/kg every 4 weeks plus tremelimumab 1 mg/kg showed a manageable tolerability profile, with antitumour activity irrespective of PD-L1 status, and was selected as the dose for phase 3 studies, which are ongoing.

Funding

This study was sponsored by MedImmune.

Introduction

The combination of programmed cell death ligand-1/programmed cell death-1 (PD-L1/PD-1) pathway and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen-4 (CTLA-4) pathway blockade targets two compartments: anti-PD-L1/anti-PD-1 acts in the tumour microenvironment and blocks inhibition of T-cell function, whereas anti-CTLA-4 acts in the lymphoid compartment to expand the number and repertoire of tumour-reactive T cells.1,2 The benefit of single-agent PD-1/PD-L1 pathway blockade in a proportion of patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) has been clearly demonstrated. However, less than half of NSCLC patients express PD-L1,3 and the majority of patients (both PD-L1-positive [PD-L1+] and PD-L1-negative [PD-L1−]) do not respond to single agent PD-1 pathway blockade, representing an opportunity for combination therapies. In studies of nivolumab plus ipilimumab for melanoma4 and NSCLC,5 durable responses were observed in both PD-L1-positive (PD-L1+) and PD-L1-negative (PD-L1−) patients, while tolerability appeared dose- and schedule-dependent, highlighting the need for optimal dose selection to minimise the toxicity of combination regimens while maintaining clinical activity.

Durvalumab (MEDI4736; MedImmune, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) is a selective, high-affinity human IgG1 monoclonal antibody (mAb) that blocks PD-L1 binding to PD-1 and CD80 but does not bind to programmed-cell death ligand 2 (PD-L2),6 avoiding potential immune-related toxicity due to PD-L2 blockade that is observed in susceptible animal models.7,8 In an ongoing Phase 1/2 study, durvalumab monotherapy has produced durable responses in patients with advanced NSCLC, with a manageable tolerability profile; confirmed objective response rate (ORR) with durvalumab 10 mg/kg every 2 weeks (q2w) was 19/84 (23%) in PD-L1+ patients, and 5/92 (5%) in PD-L1− patients.9 In this study, a maximum tolerated dose (MTD) was not reached in the dose-escalation phase, and dose-expansion cohorts were initiated using a dose of 10 mg/kg q2w.9 Tremelimumab (CP-675,206, MedImmune, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) is a selective human IgG2 mAb inhibitor of CTLA-410; it promotes T-cell activity through CTLA-4 inhibition, but does not appear to directly deplete regulatory T cells.11 The combination of durvalumab and tremelimumab was based on strong preclinical data indicating that the two pathways are nonredundant, which suggests that targeting both may have additive or synergistic effects.12 The current report describes the results of the dose-escalation part of a Phase 1b study evaluating the tolerability and antitumour activity of this combination in patients with advanced NSCLC, regardless of PD-L1 expression status.

Methods

Study design and participants

Immunotherapy-naive patients with confirmed locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC were eligible for the study. Progression at inclusion was investigator-determined. See appendix p18 for details regarding inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Procedures

This is an ongoing, multicentre, non-randomised, open-label Phase 1b study. It is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT02000947.

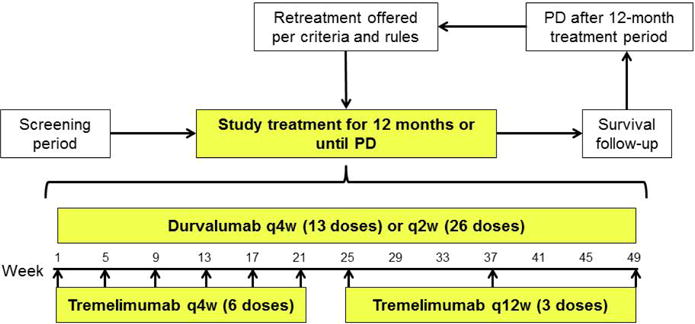

Study drugs were administered intravenously every four weeks (q4w) for 13 doses of durvalumab (D), and q4w for six doses followed by every 12 weeks (q12w) for three doses of tremelimumab (T). Patients were enrolled according to a standard 3+3 and modified zone-based design13 (appendix p10), with further expansion of escalation cohorts to allow for safety assessment. The modified zone-based design allows for the exploration of cohorts (comparisons of multiple combinations of doses) in lower zones or within a zone. Exploration of higher zones can occur if a lower zone is used as an intermediate. If no more than 1/6 patients experienced a dose-limiting toxicity (DLT) in a given dose cohort, then dose escalation continued until reaching the MTD or the highest protocol-defined dose for each agent. If the MTD is exceeded for two or more cohorts within a zone or for the starting dose cohort for two adjacent zones, then further exploration to higher zones cannot occur even if a lower intermediate zone is evaluated. Multiple combinations of durvalumab 3 mg/kg (D3) to 20 mg/kg (D20) and tremelimumab 1 mg/kg (T1) to 3 mg/kg (T3) as well, as a D15 q4w/T10 combination were explored (Table 1). During the escalation phase, D10 q2w was also tested in combination with T1 or T3. Study treatment was for 12 months (Figure 1). Treatment interruptions, but not dose reductions, were permitted.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and disease characteristics – all dose cohorts

| Characteristic | D3 q4w T1 n=3 |

D10 q4w T1 n=3 |

D15 q4w T1 n=18 |

D20 q4w T1 n=18 |

D10 q2wT1 n=17 |

D10 q4w T3 n=3 |

D15 q4w T3 n=14 |

D20 q4w T3 n=6 |

D10 q2w T3 n=11 |

D15 q4w T10 n=9 |

All Cohorts N=102 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age, years (range) | 720 (71, 78) | 670 (64, 71) | 665 (53, 78) | 660 (49, 78) | 700 (43, 77) | 540 (54, 83) | 690 (59, 76) | 700 (50, 78) | 630 (22, 86) | 650 (54, 77) | 670 (22, 86) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||||||||||

| Male | 1 (33) | 2 (67) | 9 (50) | 9 (50) | 8 (47) | 1 (33) | 10 (71) | 3 (50) | 8 (73) | 4 (44) | 55 (54) |

| Female | 2 (67) | 1 (33) | 9 (50) | 9 (50) | 9 (53) | 2 (67) | 4 (29) | 3 (50) | 3 (27) | 5 (56) | 47 (46) |

| ECOG PS, n (%) | |||||||||||

| 0 | 0 (0) | 2 (67) | 5 (28) | 5 (28) | 8 (47) | 2 (67) | 6 (43) | 1 (17) | 1 (9) | 1 (11) | 31 (30) |

| 1 | 3 (100) | 1 (33) | 13 (72) | 13 (72) | 9 (53) | 1 (33) | 8 (57) | 5 (83) | 10 (91) | 8 (89) | 71 (70) |

| Histology, n (%) | |||||||||||

| Squamous | 1 (33) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | 2 (11) | 4 (24) | 0 (0) | 1 (7) | 0 (0) | 1 (9) | 0 (0) | 10 (10) |

| Non-squamous | 2 (67) | 3 (100) | 17 (94) | 16 (89) | 13 (76) | 3 (100) | 13 (93) | 6 (100) | 10 (91) | 9 (100) | 92 (90) |

| Smoking status, n (%) | |||||||||||

| Never smoked | 1 (33) | 0 (0) | 3 (17) | 0 (0) | 4 (24) | 1 (33) | 2 (14) | 2 (33) | 3 (27) | 1 (13) | 17 (17) |

| Current | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (12) | 0 (0) | 2 (14) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (4) |

| Former | 2 (67) | 3 (100) | 15 (83) | 18 (100) | 11 (65) | 2 (67) | 10 (71) | 4 (67) | 8 (73) | 7 (88) | 80 (79) |

| Mutation status, n (%) | |||||||||||

| EGFR | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (11) | 2 (11) | 4 (24) | 0 (0) | 1 (7) | 1 (17) | 1 (9) | 2 (22) | 13 (13) |

| ALK | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (9) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| KRAS | 1 (33) | 1 (33) | 1 (6) | 1 (6) | 2 (12) | 0 (0) | 2 (14) | 2 (33) | 4 (36) | 3 (33) | 17 (17) |

| No mutation | 0 (0) | 2 (67) | 14 (78) | 14 (78) | 7 (41) | 3 (100) | 8 (57) | 3 (50) | 5 (45) | 3 (33) | 59 (58) |

| Other | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (11) | 3 (3) |

| Unknown | 2 (67) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | 4 (24) | 0 (0) | 2 (14) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 9 (9) |

| Lines of prior systemic therapy, n (%) | |||||||||||

| 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | 1 (6) | 1 (33) | 1 (7) | 0 (0) | 2 (18) | 0 (0) | 6 (6) |

| 1 | 1 (33) | 0 (0) | 8 (44) | 9 (50) | 6 (35) | 2 (67) | 5 (36) | 1 (17) | 6 (55) | 2 (22) | 40 (39) |

| 2 | 0 (0) | 1 (33) | 7 (39) | 4 (22) | 6 (35) | 0 (0) | 5 (36) | 1 (17) | 2 (18) | 4 (44) | 30 (29) |

| 3 | 2 (67) | 1 (33) | 1 (6) | 3 (17) | 2 (12) | 0 (0) | 1 (7) | 3 (50) | 1 (9) | 2 (22) | 16 (16) |

| ≥4 | 0 (0) | 1 (33) | 2 (11) | 1 (6) | 2 (12) | 0 (0) | 2 (14) | 1 (17) | 0 (0) | 1 (11) | 10 (10) |

ALK= anaplastic lymphoma kinase; D=durvalumab; ECOG PS=Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; EGFR= epidermal growth factor receptor; q=every; T=tremelimumab; w=weeks; doses are mg/kg.

Figure 1. Dosing schedule.

PD=progressive disease; q=every; w=weeks.

Outcomes

Primary

The primary endpoint of the dose-escalation phase was the safety of durvalumab in combination with tremelimumab (as determined by the MTD or the highest protocol-defined dose in the absence of exceeding the MTD) and the tolerability of the combination. Adverse events (AEs), serious AEs (SAEs), and laboratory abnormalities were classified and graded according to National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for AEs version 4 03 and monitored from the start of the study until 90 days after the last dose of study drugs. Laboratory assessments of hematology, serum chemistry and thyroid function were conducted on Days 1 and 2, weekly through Week 13, then every 4 weeks through Week 49. SAEs occurring ≥90 days post-last dose and considered related to study treatment according to the investigator were also reported.

Secondary

Secondary endpoints included antitumour activity, pharmacokinetic (PK) parameters (durvalumab and tremelimumab concentrations in serum), and immunogenicity (anti-drug antibodies [ADA]) measured with validated assays (appendix p19). Assessment of antitumour activity included investigator-reported response based on Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 11.14 Computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging studies were conducted every 8 weeks during treatment, at the end of treatment, 12 months after the last dose and then every 6 months thereafter.

Exploratory

Exploratory endpoints included pharmacodynamic parameters (free soluble PD-L1 [sPD-L1] suppression and biomarkers assessing the biological activity of durvalumab in combination with tremelimumab). Target engagement for durvalumab was assessed using suppression of free sPD-L1 in serum. The sPD-L1 that is not bound by durvalumab was quantified using a validated electrochemiluminescence method. Circulating quantities of T cells expressing the activation marker human leukocyte antigen-DR or the intracellular proliferation marker Ki67 were monitored using qualified flow cytometry-based assays.

Archival tumour or fresh tumour biopsies performed at baseline were assessed for PD-L1 expression. If two samples were tested from a patient and one was positive, the patient was considered PD-L1+. PD-L1 was analysed using the validated Ventana SP263 immunohistochemistry assay optimised for use on the automated BenchMark ULTRA® platform and samples were considered positive if ≥25% of tumour cells demonstrated membrane staining for PD-L1.15 This cutoff was clinically validated based on the durvalumab monotherapy study in patients with NSCLC or squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN).9 The only PD-L1 staining parameter that correlated with response was PD-L1 expression in the membrane of tumour cells, regardless of staining intensity. The selected cutoff for PD-L1 positivity was based on statistical analysis, distribution, prevalence, and other criteria.15 In order to explore the antitumour activity of durvalumab plus tremelimumab in more detail in patients with <25% PD-L1 staining, the findings of this study are presented separately for patients with 0% staining, who would be more likely to be considered PD-L1− regardless of assay or PD-L1 expression cutoff used. See appendix p19 for additional details.

Statistical analysis

The actual number of patients was dependent upon the toxicities observed as the study progressed. Up to approximately 118 evaluable patients (78 in q4w and 40 in q2w) could be enrolled.

MTD evaluation was based on the DLT-evaluable population. Tolerability was based on the as-treated population (all patients receiving any dose of either study drug). Antitumour activity was based on the response evaluable population, defined as patients who had initiated treatment ≥24 weeks prior to data cutoff (appendix p19). The median for duration of response was calculated based on the Kaplan-Meier method. Data analyses were conducted using SAS® System Version 93 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) on a UNIX platform.

For antitumour activity, objective response was defined as confirmed complete or partial response (CR or PR), and disease control at 24 weeks was defined as CR, PR, or stable disease (SD) duration of ≥24 weeks. The ORR and disease control rate (DCR) at 24 weeks were estimated and 95% confidence intervals (Cls) were calculated using the exact binomial distribution. ORR and DCR at 24 weeks including confirmed and unconfirmed CR or PR was also summarized in a similar fashion.

Safety and antitumour activity measures were evaluated by cohort and by combined cohorts for T1 and T3. In order to provide a clearer understanding of the safety profile, the T1 and T3 combined cohorts and the T10 cohort were selected for analysis because the safety profile of the combination appeared to be driven by the tremelimumab dose, based on the known safety profiles of the monotherapies. The combined T1 and T3 cohorts also yielded a more substantial cohort size compared with the individual cohorts. The combined T1 cohort included all T1 cohorts except the D3 q4w/T1 cohort (n=3), as this was associated with low durvalumab PK exposure and was considered to be a sub-therapeutic durvalumab dose.

Role of the funding source

The investigators and sponsor were responsible for study design and conduct including the collection, management, analysis and interpretation of data; as well as the preparation and approval of the publication. Study conduct was overseen by Institutional Review Boards or Independent Ethics Committees. All authors had full access to the data used to prepare this manuscript. The corresponding author had final responsibility for the decision to submit the report for publication.

Results

Patient disposition and baseline characteristics

102 patients were recruited into the dose-escalation phase of the study at five centres in the United States between 28 October, 2013 and 1 April, 2015. As of the 1 June, 2015 cutoff, all 102 patients had received study treatment in the dose-escalation phase and were included in the as-treated population.

Across all dose cohorts, median duration of follow-up was 188 weeks (range 2-68, IQR 22). Patients received a median of 3 doses of durvalumab (range 1–13), and 3 doses (range 1–9) of tremelimumab. At the time of data cutoff, four patients (three with progressive disease prior to treatment completion, one with ongoing PR) had completed 1 year of treatment and were in follow-up, and 26/102 patients (25%) were still on treatment. The most common reasons for discontinuation were AEs (27/102, 26%), progressive disease (21/102, 21%), and death (15/102, 15%).

Median age was 67 0 years (range 22–86), 55/102 (54%) of patients were male, 92/102 (90%) had non-squamous NSCLC, and 71/102 (70%) had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 1; 40/102 (39%) had received 1 prior line of systemic therapy and 56/102 (55%) had received ≥2 prior lines (Table 1).

Tolerability

The MTD was exceeded in the D20 q4w/T3 cohort with two of six patients experiencing a DLT (Grade 3 increased aspartate aminotransferase [AST]/alanine aminotransferase [ALT] and Grade 4 increased lipase). Across all cohorts, 82/102 (80%) of patients experienced ≥1 treatment-related AE (Table 2, appendix p1 and p3). The most common were diarrhea (33/102, 32%), fatigue (24/102, 24%), and pruritus (21/102, 21%). One patient had a treatment interruption due to an AE. Grade 3/4 treatment-related AEs occurred in 43/102 (42%) of patients; the most common Grade 3/4 treatment-related AEs of special interest were diarrhoea (11/102, 11%), colitis (9/102, 9%), and increased lipase (8/102, 8%). Grade 3/4 amylase elevations occurred in 3/102 (3%) of patients and were not associated with symptoms or clinical sequelae. A greater frequency of AEs was seen with increasing dose of tremelimumab. In the combined T1 cohort, 17/56 (30%) of patients had Grade 3/4 treatment-related AEs, compared with 19/34 (56%) in the combined T3 cohort and 7/9 (78%) in the T10 cohort.

Table 2.

Summary of AEs and selected treatment-related AEs of special interest occurring in ≥2% of patients (any Grade) or in any patients (Grade 3 or higher) − combined cohorts

| n (%) | D10–20 q4/2w T1* n=56 |

D10–20 q4/2w T3 n=34 |

D15 q4w T10 n=9 |

All cohorts N=102 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Summary of AEs

| ||||||||

| Any AE | 55 (98) | 34 (100) | 9 (100) | 101 (99) | ||||

| Any Grade 3/4 AE | 35 (63) | 29 (85) | 8 (89) | 72 (71) | ||||

| Any death | 15 (27) | 6 (18) | 1 (11) | 22 (22) | ||||

| SAE | 31 (55) | 26 (76) | 8 (89) | 66 (65) | ||||

| AE leading to discontinuation | 16 (29) | 18 (53) | 5 (56) | 40 (39) | ||||

| Related AE | 41 (73) | 32 (94) | 8 (89) | 82 (80) | ||||

| Related Grade 3/4 AE | 17 (30) | 19 (56) | 7 (78) | 43 (42) | ||||

| Related death | 2 (4) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 3 (3) | ||||

| Related SAE | 12 (21) | 18 (53) | 7 (78) | 37 (36) | ||||

| Related AE leading to discontinuation | 9 (16) | 15 (44) | 5 (56) | 29 (28) | ||||

|

Selected treatment-related AEs of interest | ||||||||

| Clinical conditions | All grades | Grade 3/4 | All grades | Grade 3/4 | All grades | Grade 3/4 | All grades | Grade 3/4 |

|

| ||||||||

| Diarrhoea | 13 (23) | 4 (7) | 16 (47) | 6 (18) | 4 (44) | 1 (11) | 33 (32) | 11 (11) |

| Colitis | 2 (4) | 1 (2) | 8 (24) | 6 (18) | 2 (22) | 2 (22) | 12 (12) | 9 (9) |

| Enteritis | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Pruritus | 11 (20) | 0 (0) | 7 (21) | 0 (0) | 3 (33) | 0 (0) | 21 (21) | 0 (0) |

| Rash | 6 (11) | 0 (0) | 7 (21) | 0 (0) | 2 (22) | 0 (0) | 15 (15) | 0 (0) |

| Hypothyroidism | 5 (9) | 1(2) | 4 (12) | 0 (0) | 1 (11) | 0 (0) | 10 (10) | 1 (1) |

| Pneumonitis | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (9) | 2 (6) | 2 (22) | 2 (22) | 5 (5) | 4 (4) |

| Rash maculopapular | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 2 (6) | 0 (0) | 1 (11) | 1 (11) | 4 (4) | 1 (1) |

|

| ||||||||

| Investigations | All grades | Grade 3/4 | All grades | Grade 3/4 | All grades | Grade 3/4 | All grades | Grade 3/4 |

|

| ||||||||

| Amylase increased† | 9 (16) | 1 (2) | 5 (15) | 2 (6) | 2 (22) | 0 (0) | 17 (17) | 3 (3) |

| Lipase increased† | 7 (13) | 5 (9) | 4 (12) | 2 (6) | 1 (11) | 1 (11) | 12 (12) | 8 (8) |

| ALT increased | 6 (11) | 2 (4) | 4 (12) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 10 (10) | 3 (3) |

| AST increased | 4 (7) | 3 (5) | 3 (9) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 7 (7) | 4 (4) |

| Blood TSH decreased | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | 2 (6) | 0 (0) | 2 (22) | 0 (0) | 6 (6) | 0 (0) |

| Blood creatinine increased | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 2 (6) | 0 (0) | 1 (11) | 0 (0) | 4 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Blood TSH increased | 3 (5) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (11) | 0 (0) | 5 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Thyroxine free decreased | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | 2 (6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (4) | 0 (0) |

Note: A patient may be counted in multiple preferred terms

Excludes D3 q4w T1 cohort (n=3)

Amylase/lipase increase was added to AEs of significant interest list because it matched the dose-limiting toxicity criteria.

AE=adverse event; ALT=alanine transaminase; AST=aspartate transaminase; D=durvalumab; GGT=gamma-glutamyl transferase; q=every; SAE=serious AE; T=tremelimumab; TSH=thyroid-stimulating hormone; w=weeks.

Generally, Grade 3/4 treatment-related AEs were manageable using standard guidelines; overall, 51/102 (50%) of patients received steroids (23/56 [41%] in the combined T1 cohort; 20/34 [59%] in the combined T3 cohort; and 7/9 [78%] in the T10 cohort); 5/102 (5%) received tumour necrosis factor inhibitor therapy (appendix p1). Fifteen of 43 patients (35%) received ≥1 additional dose of study treatment after the start of the first Grade 3/4 treatment-related AEs (AEs were increased lipase, n=5; increased amylase, n=3; anemia, n=2; and increased blood triglycerides, rash maculo-papular, lymphocytic hypophysitis, hypothyroidism, diarrhea, hypotension, and increased blood alkaline phosphatase, each n=1). Discontinuations due to treatment-related AEs occurred in 29/102 (28%) of patients (9/56 [16%] in the combined T1 cohort; 15/34 [44%] in the combined T3 cohort; and 5/9 [56%] in the T10 cohort); these AEs included colitis (9/102 [9%]), diarrhoea (5/102 [5%]), and pneumonitis (5/102 [5%]). Increasing doses of tremelimumab with a constant dose of durvalumab were associated with greater frequency of any cause Grade 3/4 AEs and any cause AEs leading to discontinuation.

Among the 18 patients who received D20 q4w/T1, 11 (61%) experienced treatment-related AEs and three (17%) had Grade 3/4 treatment-related AEs. The most frequent treatment-related any grade AEs in this cohort were pruritus (3/18, 17%), increased AST, diarrhoea, hypothyroidism, and rash (each 2/18, 11%). Six (33%) patients used systemic corticosteroids and none required additional immunomodulatory agents. Three (17%) patients discontinued due to treatment-related AEs (sepsis, pruritus, and pericardial effusion).

There were three treatment-related deaths, due to complications arising from treatment-related myasthenia gravis (D10 q4w/T1 cohort), pericardial effusion (D20 q4w/T1 cohort), and neuromuscular disorder (D20 q4w/T3 cohort).

Pharmacokinetics and Immunogenicity

An approximately dose-proportional increase in PK exposure (Cmax and AUCT) of both durvalumab and tremelimumab was observed across all doses (appendix p12). PK exposures of both durvalumab and tremelimumab in combination following all dosing regimens were in line with monotherapy data and as predicted by population PK modelling.16 Overall, low levels of ADA were observed following durvalumab (4/60 patients, 6–6%) and tremelimumab (1/53, 18%) in combination. There was no association between ADAs and tolerability or antitumour activity (appendix p20).

Based on population PK analyses and simulations, the serum concentrations for durvalumab overlapped between 10 mg/kg q2w and 20 mg/kg q4w. The overall AE profile of 20 mg/kg q4w was evaluated in a subset of patients in the monotherapy study and appears similar to that seen at 10 mg/kg q2w in this study. The monotherapy results will be reported in depth in a separate manuscript in preparation.

Pharmacodynamics

Complete free sPD-L1 suppression was observed in almost all patients across all doses (appendix p13). A monotonic increase in peak CD4+Ki67+ cells was observed with increasing tremelimumab dose (appendix p14). Peak CD8+Ki67+ and CD4+HLA-DR+ cells were highest with the T10 dose, with T1 and T3 doses eliciting equivalent elevations from baseline. At the lowest tremelimumab dose (1 mg/kg), a trend of durvalumab dose-dependence was observed on mean CD4+Ki67+ changes from baseline at day 8 and day 15.

Antitumour activity

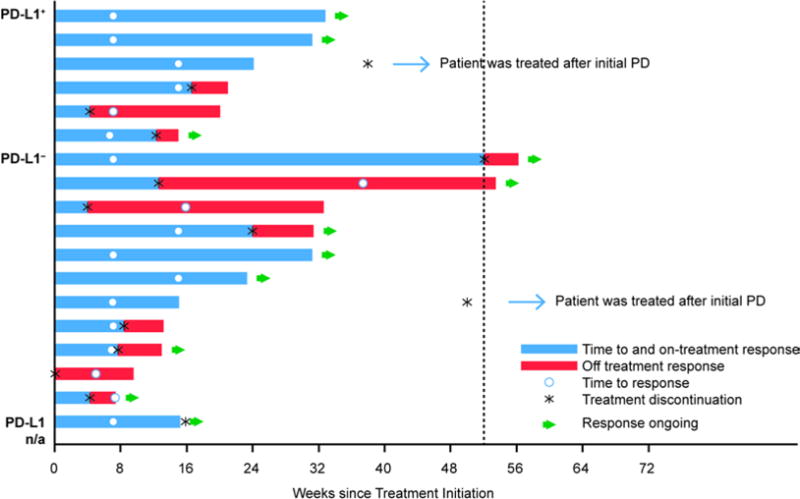

Across all cohorts, 63 patients were evaluable (≥24 weeks of follow-up). The ORR was 11/63 (17%, 95% CI, 9–29) and the DCR at 24 weeks was 18/63 (29%, 95% CI, 18–41) (Table 3, appendix p7). Among the 11 patients with confirmed objective response, median time to response was 7.1 weeks (range, 6.7–15.9) and median duration of response was not reached (range, 6.1+–49.1 + weeks) (Figure 2). Response was ongoing in nine of these patients at the time of data cutoff. Two additional patients with ongoing response were awaiting confirmatory scan. In the epidermal growth factor receptor/anaplastic lymphoma kinase wild-type population, the ORR was 11/58 (19%, 95% CI, 10–31).

Table 3.

Antitumour activity summary by dose level, in combined cohorts, and by PD-L1 status (confirmed responses)*

| Antitumour activity by dose level

| |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | D3 q4w T1 n=3 |

D10 q4w T1 n=3 |

D15 q4w T1 n=12 |

D20 q4w T1 n=8 |

D10 q2w T1 n=3 |

D10 q4w T3 n=3 |

D15 q4w T3 n=10 |

D20 q4w T3 n=6 |

D10 q2w T3 n=6 |

D15 q4w T10 n=9 |

All cohorts N=63 |

|

| |||||||||||

| All evaluable patients with ≥24 weeks follow-up | |||||||||||

| ORR | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (25) | 3 (38) | 0 (0) | 1 (33) | 2 (20) | 1 (17) | 1 (17) | 0 (0) | 11 (17) |

| DCR (CR, PR, SD ≥24 weeks) | 0 (0) | 1 (33) | 5 (42) | 3 (38) | 0 (0) | 2 (67) | 4 (40) | 1 (17) | 1 (17) | 1 (11) | 18 (29) |

| Antitumour activity − combined cohorts

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%; 95% CI) | D10−20 q4/2w T1† n=26 |

D10−20 q4/2w T3 n=25 |

D15 q4w T10 n=9 |

All cohorts N=63 |

|

| ||||

| All evaluable patients with ≥24 weeks follow-up | ||||

| ORR | 6 (23; 9−44) | 5 (20; 7−41) | 0 (0; 0−34) | 11 (17; 9−29) |

| DCR (CR, PR, SD ≥24 weeks) | 9 (35; 17−56) | 8 (32; 15−54) | 1 (11; 0−48) | 18 (29; 18−41) |

|

| ||||

| PD-L1+ (≥25%) | n=9 | n=5 | n=4 | n=18 |

| ORR | 2 (22; 3−60) | 2 (40; 5−85) | 0 (0; 0−60) | 4 (22; 6−48) |

| DCR (CR, PR, SD ≥24 weeks) | 3 (33; 8−70) | 2 (40; 5−85) | 1 (25; 1−81) | 6 (33; 13−59) |

|

| ||||

| PD-L1− | ||||

| PD-L1 <25% | n=14 | n=17 | n=4 | n=37 |

| ORR | 4 (29; 8−58) | 2 (12; 2−36) | 0 (0; 0−60) | 6 (16; 6−32) |

| DCR (CR, PR, SD ≥24 weeks) | 6 (43; 18−71) | 5 (29; 10−56) | 0 (0; 0−60) | 11 (30; 16−47) |

| PD-L1 0% | n=10 | n=10 | n=3 | n=24 |

| ORR | 4 (40; 12−74) | 1 (10; 0−45) | 0 (0; 0−71) | 5 (21; 7−42) |

| DCR (CR, PR, SD ≥24 weeks) | 5 (50; 19−81) | 3 (30; 7−65) | 0 (0; 0−71) | 8 (33; 16−55) |

|

| ||||

| PD-L1 unknown | n=3 | n=3 | n=1 | n=8 |

| ORR | 0 (0; 0−71) | 1 (33; 1−91) | 0 (0; 0−98) | 1 (13; 0−53) |

| DCR (CR, PR, SD ≥24 weeks) | 0 (0; 0−71) | 1 (33; 1−91) | 0 (0; 0−98) | 1 (13; 0−53) |

Includes confirmed CR or PR. In patients with measurable disease at baseline, ≥1 follow-up scan includes those that discontinued due to progressive disease or death without any follow-up scan. All patients were dosed ≥24 weeks prior to the cutoff date.

Excludes D3 q4w T1 cohort (n=3)

CR= complete response; D=durvalumab; DCR=disease control rate; ORR=objective response rate; PD-L1=programmed cell death ligand-1; PR=partial response; q=every; SD=stable disease; T=tremelimumab; w=weeks.

Figure 2. Time to RECIST response (confirmed and unconfirmed) and duration of response.

PD=progressive disease; PD-L1=programmed cell death ligand-1; RECIST=Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors.

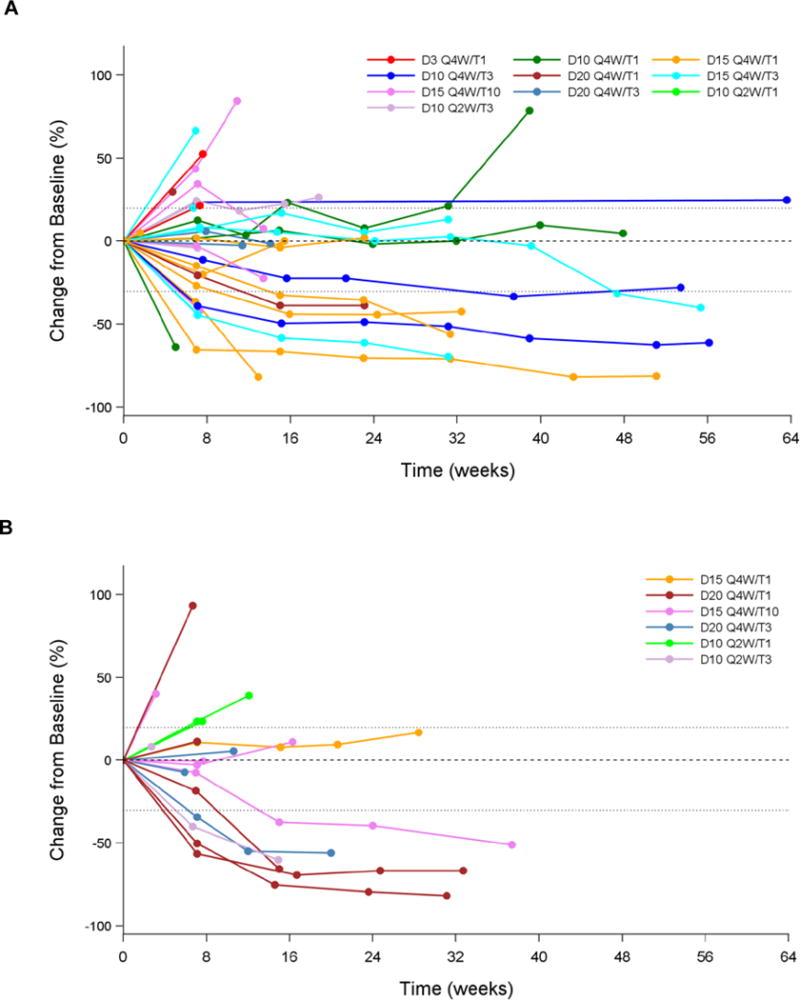

There were no responses in the lowest dose cohort (D3 q4w/T1, n=3), with progression on first scan among all patients. ORR was 6/26 (23%, 95% CI, 9–44) in the combined T1 cohort and 3/8 (38%, 95% CI, 9–76) in the D20 q4w/T1 cohort. Higher doses of tremelimumab were not associated with higher response rates. See appendix p16 for changes from baseline in tumour size in the combined T1 cohort, the combined T3 cohort, and the T10 cohort.

Antitumour activity by PD-L1 status

Antitumour activity was observed in patients with both PD-L1− and PD-L1+ tumours, and few differences were noted among dosing cohorts (Figure 3; Table 3; appendix p9). In the combined T1 cohort, ORR among patients with PD-L1− tumours was 4/14 (29%, 95% CI, 8–58); among those with 0% PD-L1 expression, ORR was 4/10 (40%, 95% CI, 12–74). Among patients in the combined T1 cohort with PD-L1+ tumours, ORR was 2/9 (22%, 95% CI, 3–60).

Figure 3. Antitumour activity according to PD-L1 status (response evaluable population with ≥24 weeks follow-up).

Change in tumour size from baseline in (A) PD-L1− patients (PD-L1 <25%), (B) PD-L1+ patients (PD-L1 ≥25%), (C) patients with unknown PD-L1 status; (D) Best change in tumour size by PD-L1 status. D=durvalumab; na=status unknown; PD- L1=programmed cell death ligand-1; Q=every; T=tremelimumab; W=weeks.

Discussion

In this study, the MTD was exceeded at D20 q4w/T3. At doses of T1, most AEs were manageable and did not require treatment discontinuation. Relative to the AE profile of the T1 combination doses, the T3 and T10 dose-based combinations were not as well tolerated based on a higher frequency of treatment-related any Grade AEs, Grade 3/4 AEs, and SAEs, without any increase in clinical efficacy. Rates of treatment-related any Grade and Grade 3/4 AEs were numerically greater with D10 q2w/T1 dosing than with D20 q4w/T1 dosing. The most frequent AEs were consistent with the known toxicity profiles of durvalumab and tremelimumab. The majority of AEs observed were manageable and generally reversible using standard treatment guidelines. Fifteen of 43 patients (35%) experiencing a Grade 3/4 treatment-related AE received additional study treatment after initial onset of the toxicity.

The results of this study are broadly comparable to those of the recent Phase 3 nivolumab/ipilimumab study in melanoma, in terms of the rates of any-grade treatment-related AEs, the proportion of patients receiving immunomodulatory agents (including topical steroids) and the proportion of patients receiving secondary immunosuppressives such as infliximab.4

Observed exposures to durvalumab and tremelimumab following concurrent administration were in line with respective monotherapy data,9,11,17,18 indicating no PK interaction between the two drugs. In addition, PK analyses demonstrated that q4w and q2w dosing appeared equivalent. No patient in the D20 q4w/T1 cohort developed ADAs.

Complete suppression of free sPD-L1, indicative of effective target engagement by durvalumab, was observed in almost all patients. Additionally, combination doses of durvalumab and tremelimumab demonstrated greater peripheral T-cell activation and proliferation than durvalumab monotherapy, even at the lowest tremelimumab dose (1 mg/kg).9 Based on the safety profile of the combination where there is evidence of greater toxicity versus established profiles of the respective monotherapies, and evidence of enhanced pharmacodynamic activity from exploratory endpoints (e.g. enhanced Ki67 indices with the combination versus durvalumab monotherapy, see appendix p14), our data suggest that combined CTLA-4 and PD-L1 blockade appears to be associated with higher biological activity compared with respective monotherapy.

Evidence of antitumour activity was seen with the combination of durvalumab and tremelimumab in patients with advanced NSCLC in the dose-escalation phase of this study, regardless of PD-L1 status. In comparison, ORR in NSCLC patients with PD-L1− tumours receiving 10 mg/kg q2w durvalumab monotherapy was 5/92 (5%).9 In this study, activity was observed among patients with PD-L1− tumours, including those with 0% PD-L1 expression. Although the number of evaluable patients in each subgroup was limited, these data suggest that PD-L1 status may not predict response to the durvalumab and tremelimumab combination to the same extent as has been seen with durvalumab monotherapy. This observation also suggests that additional factors beyond PD-L1 are involved in suppressing an active immune response. It is possible that CTLA-4 activity may prevail in such patients and that tremelimumab removes a suppressive effect to drive an antitumour response. The evidence that CTLA-4 drives the immune escape is suggestive, but needs to be confirmed in a larger dataset. The antitumour activity of the combination appears to be higher than that of monotherapy with either agent,9,17 most likely because they influence distinct targets involved in immunosuppression, acting on different aspects of the antitumour immune response. Previous studies in NSCLC and other tumour types have also indicated that combined blockade of PD-1 and CTLA-4 is associated with higher clinical activity than monotherapy.4,5,19–21 The present study is currently being expanded to further evaluate the clinical activity of the combination in patients with advanced NSCLC. If confirmed, the combination could be a potential novel therapeutic option for patients with PD-L1− tumours, a subset that is not expected to derive significant benefit from current anti-PD-1/PD-L1 monotherapies.

Although the number of patients in each cohort is small, the results of this study suggest that toxicity, but not antitumour activity, tends to increase with increasing doses of tremelimumab. However, there does not appear to be any difference in toxicity across durvalumab doses with a constant dose of tremelimumab. As there were no pharmacological limitations evident with the q4w schedule, and given the equivalent PK profiles seen with D20 q4w and D10 q2w, q4w was selected over the q2w schedule for patient convenience. Data from the monotherapy study show that durvalumab exhibits nonlinear PK at doses ≥3 mg/kg and approaches linearity at doses >3 mg/kg, indicating full target saturation.22 In addition, PK simulations suggest that following D10 q2w or D20 q4w doses of durvalumab, ≥90% of patients achieve target trough concentrations throughout the dosing interval.16 The D20 q4w/T1 regimen has therefore been selected for assessment in Phase 3 studies. This dose maximises free sPD-L1 inhibition, has a manageable safety profile, and incorporates a biologically active dose of tremelimumab that is associated with antitumour activity, including in patients with PD-L1− tumours. Doses above T1 did not result in greater antitumour activity but were generally associated with higher AE rates.

A limitation of this study was the heterogeneous population overall and within combined cohorts (e.g., number of previous lines of therapy, tumour mutation status and patient’s smoking history were not equal across cohorts). In addition, antitumour activity was assessed only in patients who had initiated treatment ≥24 weeks before data cutoff, and may have been underestimated due to the short follow-up time. However, in our experience, most patients demonstrate their response within this period. This is also consistent with published experience for PD-1/PD-L1-based therapies.23–25 A longer follow-up would be needed to establish impact on survival. Our current data suggest that although AEs may have been underestimated due to the limited follow-up time, the majority of patients who have related Grade ≥3 AEs tend to experience them within the first few months after treatment initiation. As the study did not include durvalumab or tremelimumab monotherapy arms, comparisons to monotherapy data are based on other studies.

In conclusion, the tolerability profile and antitumour activity of the combination observed both in PD-L1+ and PD-L1− patients in the dose-escalation phase of this study shows that 1 mg/kg tremelimumab is sufficient to augment the biological and antitumour activity of durvalumab. Enrolment has begun using the selected combination regimen in the expansion phase of the current study as well as in pivotal studies for NSCLC, bladder cancer, and SCCHN.

Supplementary Material

Research in Context.

Evidence before this study

We searched PubMed for reports of preclinical and clinical research on anti-programmed cell death-ligand 1 (PD-L1)/programmed cell death-1, and anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen-(CTLA-4) antibody treatments for cancer, published from 2005 to 2015. Most of the clinical studies were reported in the last two years. Patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) that progresses after first-line treatment have a significant unmet need, as current therapies have limited clinical utility. Early clinical data suggest that combination immune checkpoint blockade may have greater antitumour activity than monotherapy in melanoma and other tumour types including NSCLC, although the incidence of adverse events also appears to be greater than that of single agents. Monotherapy with the PD-L1 inhibitor durvalumab has produced durable responses in patients with advanced NSCLC, with a manageable tolerability profile; confirmed response rates were numerically higher in the PD-L1 positive population (19/84, 23%) compared with the PD-L1 negative population (5/92, 5%) as determined by a validated assay. To our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate the safety and antitumour activity of durvalumab in combination with the CTLA-4 inhibitor tremelimumab in patients with locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC.

Added value of this study

Employing a unique design to determine an optimal dose, the dose-escalation part of the study demonstrated that combinations of durvalumab with 1 mg/kg tremelimumab had a manageable tolerability profile, and a 1 mg/kg dose of tremelimumab was sufficient to augment the biological and clinical activity of durvalumab. Clinical activity was observed regardless of PD-L1 expression status, including in patients with no tumour cell membrane PD-L1 staining.

Implications of all the available evidence

The clinical activity in patients with PD-L1− tumours, including those with no tumour cell membrane PD-L1 staining, is a particularly important advance, as these patients are less responsive to single agents blocking the PD-1 checkpoint pathway. On the basis of these investigations, the dose of combination treatment with durvalumab and tremelimumab was selected for Phase 3 studies, which are currently ongoing.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients and their families participating in this study. This study was sponsored by MedImmune. Medical writing and editorial assistance were provided by Susanne Gilbert of CircleScience, an Ashfield company (funded by MedImmune). The following individuals contributed to the study: Amanda Garofalo, Kelly Henson, Xiaoping Jin, Meina Liang, Marlon Rebelatto, Paul Robbins, Nathan Standifer, and the entire Study 6 team.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

SA has served on Advisory Boards for MedImmune and AstraZeneca. SG has received research funding from AstraZeneca and Boehringer Ingelheim and has served on Advisory Boards for Clovis. AB has received financial support to run clinical trials from Genentech, Incyte, MedImmune, and Merck; and fees for Speaker Bureau participation from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Merck. JC has received financial clinical trial support from AstraZeneca/MedImmune and has received personal fees from Genentech. AG, KS, YG, JK, and RN are employees of MedImmune; JK, YG, AG, KS, and RN also own stock/stock options in AstraZeneca. YG was previously an employee of Boehringer Ingelheim. JK is also an employee of MedStar Montgomery Medical Center and Fauquier Hospital. KS has a provisional patent application related to this work. NR has received personal fees from AstraZeneca, BMS, Roche, Novartis, and Merck. SA has received an NIH grant. RS declares no competing interests.

Contributors

SA, JC, AG, JK, KS and NR were responsible for study design. SA and NR were responsible for enrolment and management of patients. SA, SG, AB, AG, JK, RN, KS and YG were responsible for data collection and interpretation. SA, SG, AB, AG, RN, YG and JK were responsible for writing the manuscript. SA and SG were responsible for review of the manuscript. AG and JK were responsible for the literature search. RN and YG were responsible for figure development.

Contributor Information

Scott Antonia, H Lee Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL, USA.

Sarah B. Goldberg, Yale University, Yale Cancer Center, New Haven, CT, USA.

Ani Balmanoukian, The Angeles Clinic and Research Institute, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Jamie E. Chaft, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY, USA.

Rachel E. Sanborn, Earle A. Chiles Research Institute, Providence Cancer Center, Portland, OR, USA.

Ashok Gupta, MedImmune, Gaithersburg, MD, USA.

Rajesh Narwal, MedImmune, Gaithersburg, MD, USA.

Keith Steele, MedImmune, Gaithersburg, MD, USA.

Yu Gu, MedImmune, Gaithersburg, MD, USA.

Joyson Joseph Karakunnel, MedImmune, Gaithersburg, MD, USA.

Naiyer A. Rizvi, Columbia University Medical Center, New York, NY, USA.

References

- 1.Gajewski TF, Schreiber H, Fu YX. Innate and adaptive immune cells in the tumor microenvironment. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:1014–22. doi: 10.1038/ni.2703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kvistborg P, Philips D, Kelderman S, et al. Anti-CTLA-4 therapy broadens the melanoma-reactive CD8+ T cell response. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:254ra128. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pan ZK, Ye F, Wu X, An HX, Wu JX. Clinicopathological and prognostic significance of programmed cell death ligand1 (PD-L1) expression in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. J Thorac Dis. 2015;7:462–70. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.02.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab or monotherapy in untreated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:23–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rizvi NA, Gettinger SN, Goldman JW, et al. Safety and efficacy of first-line nivolumab (NIVO; anti-programmed death-1 [PD-1]) and ipilimumab in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10(9_Suppl.2):S176. (Oral02.05) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stewart R, Morrow M, Hammond SA, et al. Identification and characterization of MEDI4736, an antagonistic anti-PD-L1 monoclonal antibody. Cancer Immunol Res. 2015;3:1052–62. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsumoto K, Fukuyama S, Eguchi-Tsuda M, et al. B7-DC induced by IL-13 works as a feedback regulator in the effector phase of allergic asthma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;365:170–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.10.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsumoto K, Inoue H, Nakano T, et al. B7-DC regulates asthmatic response by an IFN-gamma-dependent mechanism. J Immunol. 2004;172:2530–41. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.4.2530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rizvi N, Brahmer J, Ou S-HI. Safety and clinical activity of MEDI4736, an antiprogrammed cell death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) antibody, in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(15_Suppl) Abstract 8032. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ribas A, Camacho LH, Lopez-Berestein G, et al. Antitumor activity in melanoma and anti-self responses in a phase I trial with the anti-cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 monoclonal antibody CP-675,206. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8968–77. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tarhini AA. Tremelimumab: a review of development to date in solid tumors. Immunotherapy. 2013;5:215–29. doi: 10.2217/imt.13.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stewart R, Mullins S, Watkins A, et al. Preclinical modeling of immune checkpoint blockade (2012) J Immunol. 2013;190 (1_Meeting Abstracts):Abstract 214.7. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang X, Biswas S, Oki Y, Issa JP, Berry DA. A parallel phase I/II clinical trial design for combination therapies. Biometrics. 2007;63:429–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2006.00685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rebelatto M, Mistry A, Sabalos C, et al. Development of a PD-L1 companion diagnostic assay for treatment with MEDI4736 in NSCLC and SCCHN patients. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(15_Suppl) Abstract 8033. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Song X, Pak M, Chavez C, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of MEDI4736, a fully human anti-programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) monoclonal antibody, in patients with advanced solid tumors. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51(Suppl. 3):S28. (Abstract 203) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zatloukal P, Heo DS, Park K, et al. Randomized phase II clinical trial comparing tremelimumab (CP-675,206) with best supportive care (BSC) following first-line platinum-based therapy in patients (pts) with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(15_Suppl) Abstract 8071. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lutzky J, Antonia SJ, Blake-Haskins A, et al. A phase 1 study of MEDI4736, an anti-PD-L1 antibody, in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2014;35(15_Suppl) Abstract 3001. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Antonia SJ, Larkin J, Ascierto PA. Immuno-oncology combinations: a review of clinical experience and future prospects. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:6258–68. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swanson MS, Sinha UK. Rationale for combined blockade of PD-1 and CTLA-4 in advanced head and neck squamous cell cancer-review of current data. Oral Oncol. 2015;51:12–5. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolchok JD, Kluger H, Callahan MK, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:122–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1302369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song X, Pak M, Chavez C, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of MEDI4736, a fully human anti-programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) monoclonal antibody, in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(15_Suppl) Abstract e14009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:123–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rizvi NA, Mazières J, Planchard D, et al. Activity and safety of nivolumab, an anti-PD-1immune checkpoint inhibitor, for patients with advanced, refractory squamous non-smallcell lung cancer (CheckMate 063): a phase 2, single-arm trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:257–65. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70054-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ott PA, Elez Fernandez ME, Hiret S, et al. Pembrolizumab (MK-3475) in patients (pts) with extensive-stage small cell lung cancer (SCLC): Preliminary safety and efficacy results from KEYNOTE-028. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(15_Suppl) Abstract 7502. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.