Abstract

Episode-based payment models are increasing in popularity for surgery. We evaluated how much variation in post-acute care (PAC) spending after surgery is explained by: PAC choice (i.e., choice of home health, outpatient rehabilitation, skilled nursing, or inpatient rehabilitation) versus PAC intensity (amount of spending in a chosen setting). PAC spending varied widely between hospitals in low versus high PAC spending quintiles (total hip replacement (THR): $5,112 to $11,708, or 129% difference; coronary bypass grafting (CABG): $4,143 to $8,403, or 103% difference; colectomy: $3,345 to $6,104, or 82% difference). This variation persisted after adjusting for PAC intensity, but diminished considerably after adjusting for choice of PAC setting (THR 109% vs. 16% difference; CABG 108% vs. 4% difference; colectomy 62% vs. 21% difference). Health systems aiming to improve surgical episode efficiency should focus on working with patients to choose the highest value PAC setting.

Introduction

Post-acute care (PAC) is one of the fastest growing areas of US healthcare spending (1, 2). About 40% of older Americans discharged from a hospital utilize PAC (i.e., home health, skilled nursing facility, inpatient and outpatient rehabilitation), and the National Academy of Medicine identified PAC as the component of care most responsible for wide variation in total per capita Medicare spending (3–5). In this context, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) are holding hospitals accountable for care that occurs after discharge. In the Hospital Value-based Purchasing Program (HVBP), CMS is penalizing hospitals that spend more than their peers on episodes of care that start 3 days prior to hospital admission and end 30 days after discharge (6). CMS is also evaluating or proposing bundled payments around acute care hospitalization for several programs – Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement (CCJR),the Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) initiative, and recently proposed cardiac and orthopedic bundled payment models (7–10). In each of these programs, participating hospitals can accept payments for longitudinal, condition-specific episodes of care that include PAC.

While hospitals have been charged with identifying ways to decrease PAC spending, factors responsible for current variation in PAC spending are incompletely understood. After major inpatient surgery in older adults, hospitals have a range of choices regarding post-discharge care. Patients may be discharged without services; with home health care with or without outpatient physical therapy; or with inpatient skilled nursing or rehabilitation. Despite vastly different costs attributable to these services, there are little clinical outcomes data to guide decision-making around choice of post-acute care setting or intensity of services in a given setting. Furthermore, how discharge decisions impact post-acute care spending for surgical conditions has not yet been fully defined.

In this context, we sought to identify factors that explain variation in total PAC spending after three common, costly surgical procedures: coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), colectomy, and total hip replacement (THR). What patient and hospital characteristics are associated with variation in total PAC spending? To what degree are price and case mix responsible? Finally, are differences in PAC spending due primarily to the choice to use any PAC, the choice to use certain types of PAC, or utilization once at a PAC facility?

Methods

Data source and study population

To create cohorts of fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries, age 65 years or older undergoing total hip replacement, CABG, or colectomy from January 2009 to June 2012 at a US acute care hospital, we used Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MedPAR), Part B, Outpatient, and Home Health Agency files. To describe hospital characteristics, we used data from the American Hospital Association Annual Survey.

University of Michigan determined that Institutional Review Board approval was not required for this study.

THR, CABG, and colectomy cohorts

We started with 353,434 patients (in 3,383 hospitals) who underwent total hip replacement (ICD-9 81.51) between January 1, 2009 and June 30, 2012. We then excluded patients who had been in hospice care, a long term hospital, an inpatient rehabilitation facility, or a skilled nursing facility within 90 days prior to the index hospitalization. After excluding patients who were not Parts A&B eligible, hospitals that performed fewer than 10 THR cases per year, and patients with select clinical conditions (see Appendix Exhibit A),(11) we had 231,744 patients (1,831 hospitals) in our final sample.

For CABG, we started with 397,732 patients (1,218 hospitals) who underwent cardiac artery bypass grafting (ICD-9 3610, 3611, 3612, 3613, 3614, 3615, 3616, 3617, 3619, 362) between January 1, 2009 and June 30, 2012. After applying exclusions, we had a final sample of 218,940 patients in 1,056 hospitals.

For colectomy, we started with 283,194 patients in 3,926 hospitals who underwent colectomy (ICD-9 1731, 1732, 1733, 1734, 1735, 1736, 1739, 4571, 4572, 4573, 4574, 4575, 4576, 4579, 4581, 4582, 4583). After applying exclusions, we had 189,229 patients (1,876 hospitals) in our final sample.

Post-acute care

We defined use of post-acute care as the presence of claims for any of four types of services within 90 days of discharge: home health, outpatient rehabilitation, skilled nursing facility (SNF), and inpatient rehabilitation facility (IRF). We chose to examine PAC during a 90-day episode, because many of CMS’ current initiatives around bundled payments use 90-day episodes of care (12). We chose these four types of care because they may partially substitute for each other (13, 14).

Each PAC setting requires a different set of patient social supports and has different implications for payment. Patients discharged home with outpatient rehabilitation must be able to attend regular therapy sessions outside the home. Outpatient therapy is reimbursed on a per-service basis tied to relative value units (RVUs)(15). In contrast, patients discharged with home health have limited ability to leave their home, yet require services such as intermittent skilled nursing, or physical or occupational therapy. Home health agencies are reimbursed for a 60-day episode of care if at least 5 visits are provided. (16). Both SNFs and IRFs have on-site nursing, and therapy sessions take place in the facility. SNFs are reimbursed on a per diem basis, and payments account for a patient’s clinical and functional status and the therapy provided (17). IRFs are reimbursed per stay, and payments account a patient’s clinical, functional, and cognitive status (18). Patients who are discharged to IRFs must be able to receive three hours of therapy per day, while patients discharged to SNF do not need to meet this therapy threshold.

We identified each of the four types of PAC in claims data using information about the claims data source and/or specific codes. Of note, for most beneficiaries who used SNF or IRF during a 90-day episode, the first claim for these services occurred within a day of hospital discharge (sensitivity analyses; results not displayed).

Statistical analyses

Our overall goal is to determine the causes for differences across PAC spending quintiles, defined by the average PAC spending per patient at a given hospital. To address whether observable patient and hospital characteristics explain differences in PAC spending, we first described differences in patient and hospital characteristics across those PAC spending quintiles (See the Methods Appendix).(11) We used the Cochran Armitage test for trend and F-tests to test the hypothesis that the mean of each characteristic is the same between the first, second through fourth, and fifth quintiles.

We next assessed how variation in PAC spending was affected by a series of factors. We started with “actual cost,” which represents actual Medicare payments for post-acute care. We next adjusted for prices; this accounts for any differences in payments due to regional differences in prices (e.g., due to wages being different in different parts of the country)(19). We next additionally adjusted price-standardized payments for case mix. This quantifies how much PAC spending would differ across hospitals if all hospitals treated patients with the same severity of illness. To estimate price- and case-mix adjusted spending, we ran patient-level regressions to predict price-standardized PAC spending,(19) controlling for patient-level variables, including 28 Elixhauser co-morbidities (20), sex, race, age, admission type, prior 6-month spending, and post-operative complications.

We next described whether the remaining variation in PAC spending could be explained by differences in PAC intensity vs. choice of PAC setting. We defined PAC intensity as amount of spending in a chosen setting, or average risk-adjusted, price-standardized spending for a given PAC setting. For example, since SNFs are paid on a per diem basis, a SNF stay that is 30 days long would have a higher intensity than a SNF stay that is 20 days long, all other things being equal. To evaluate the relative effects of intensity vs. choice, we alternately assigned the same spending to all patients in a given PAC setting (to evaluate the relative contribution of PAC intensity), or held choice of PAC setting constant across hospitals (to evaluate the relative contribution of PAC choice). The remaining source of variation then was either the choice of PAC setting (if intensity was held constant), or spending once in a PAC setting (if choice of PAC setting was held constant).

To further quantify the amount of variation in PAC spending attributable to intensity versus choice of setting, we used the Oaxaca-Blinder decomposition (21, 22) and estimated the proportion of overall PAC spending differences attributable to the choice of each PAC setting, and the proportion attributable to the intensity of use in each PAC setting.

Finally, to assess whether hospital-level, price-standardized, risk-adjusted PAC spending is similar across the three studied conditions, we evaluated within-hospital correlations. P-values<0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. All analyses were conducted in Stata Version 12.1 and SAS version 9.4.

Our study had several potential limitations. First, we examined use of PAC among fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries. Thus, our findings may not be generalizable to other populations. Second, we examined PAC use after three common procedures, so our findings may not apply to patients hospitalized for medical conditions. Third, with our price-standardization,(19) we were not able to disentangle how much variation in SNF intensity was due to differences in length of stay vs. Resource Utilization Group (RUG). Fourth, we did not have information about functional status on hospital discharge, as these data do not yet exist with national Medicare claims data. Fifth, it is important to note that we did not include readmissions in our definition of PAC, nor did we adjust our PAC intensity measure for any potential differences in readmissions across PAC spending quintiles. Finally, it is well-known that IRFs are unequally distributed across the country (23). Differential distance to PAC settings likely impacts the joint patient and hospital decision about discharge, but with our data we could not quantify how much any variability due to choice of PAC setting was due to differences in PAC availability.

Results

Utilization of and Spending on Post-Acute Care

Approximately 93% of fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries who underwent THR utilized some type of PAC in the 90 days after surgery, with modest variation across total PAC spending quintiles (Exhibit 1). Although at least half of patients utilized PAC after all three procedures, total PAC spending varied widely among hospitals (Exhibit 1).

EXHIBIT 1.

Patient and hospital characteristics by 90-day post-acute care episode spending quintile, 2009 to 2012

| Total 90-day post-acute care episode payment quintile | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | THR | CABG | Colectomy | |||

| Q1 (Low) | Q5 (High) | Q1 (Low) | Q5 (High) | Q1 (Low) | Q5 (High) | |

| General Characteristics | ||||||

| Hospitals, n | 366 | 366 | 211 | 211 | 375 | 375 |

| Patients, n | 51,548 | 35,706 | 47,967 | 38,115 | 33,049 | 34,024 |

| PAC Use, % | 82 | 99 | 73 | 89 | 40 | 61 |

| PAC spending in $s, mean | 4,576 | 12,855 | 3,633 | 10,177 | 2,694 | 7,491 |

| Case volume/year, mean | 141 | 98 | 227 | 181 | 88 | 91 |

| Patient Characteristics | ||||||

| Male, % | 38 | 35 | 68 | 66 | 42 | 40 |

| Age group, % | ||||||

| 65–69, y | 18 | 16 | 21 | 18 | 15 | 13 |

| 70–74, y | 30 | 27 | 31 | 28 | 26 | 21 |

| 75–79, y | 26 | 26 | 27 | 26 | 24 | 22 |

| ≥80, y | 26 | 32 | 20 | 28 | 34 | 43 |

| Race, % | ||||||

| White | 96 | 93 | 91 | 87 | 91 | 86 |

| Black | 2 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 8 |

| Other | 2 | 2 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 6 |

| Elixhauser score | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 6 |

| Hospital Characteristics | ||||||

| Beds, % | ||||||

| <200 | 57 | 34 | 20 | 17 | 54 | 31 |

| 200–349 | 23 | 35 | 34 | 38 | 26 | 39 |

| 350–499 | 12 | 15 | 27 | 18 | 13 | 15 |

| ≥500 | 7 | 14 | 17 | 24 | 7 | 14 |

| Teaching, % | 40 | 53 | 55 | 63 | 38 | 54 |

| Nurse ratio | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Medicaid days, % | 18 | 19 | 17 | 19 | 19 | 19 |

| Urban, % | 93 | 98 | 96 | 97 | 97 | 98 |

| Profit status, % | ||||||

| For profit | 14 | 20 | 17 | 23 | 15 | 19 |

| Non-profit | 75 | 72 | 72 | 67 | 70 | 73 |

| Other | 9 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 15 | 6 |

SOURCE/NOTES: SOURCE – Author’s analysis of Medicare data. NOTES - Non-risk-adjusted, non-price-standardized quintiles. Abbreviations: PAC is post-acute care; THR is total hip replacement; CABG is coronary artery bypass grafting.

Patient and Hospital Characteristics and Post-Acute Care Spending

Patient and hospital characteristics differed across PAC spending quintiles (Exhibit 1 and Appendix Exhibit B).(11) Compared to patients undergoing THR at hospitals in the lowest PAC spending quintile, patients undergoing THR at hospitals in the highest PAC spending quintile were more likely to be older and more likely to have a post-operative complication (Appendix Exhibit B).(11) Hospitals in the highest cost quintile for THR were more likely to be teaching hospitals, for-profit hospitals, and to be located in the Northeast (Exhibit 1). Results were similar for CABG and colectomy. All differences between the highest and lowest cost quintiles were statistically significant at the p<0.05 level.

Type and Intensity of Post-Acute Care Utilization

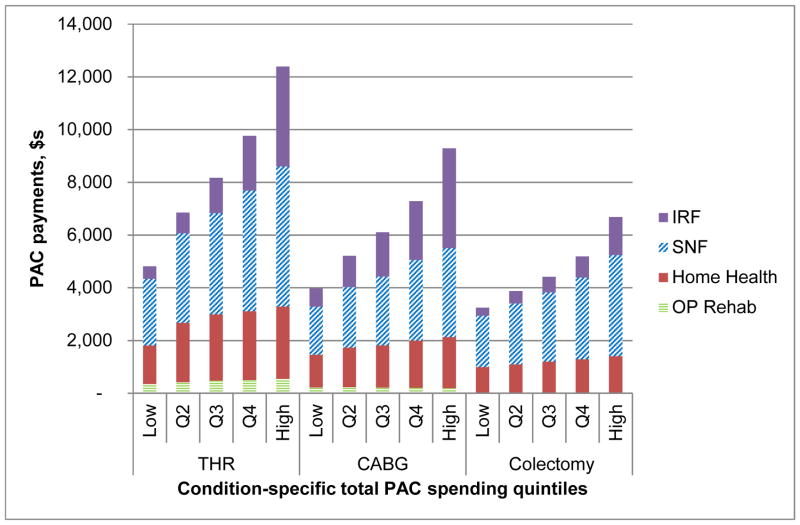

When we examined components of variation in price-standardized total PAC payments (i.e., averaged across all patients at a hospital, whether or not they used any PAC), IRF payments showed the largest increase across cost quintiles (Exhibit 2 and Appendix Exhibits C-H).(11) Spending on home health and outpatient rehabilitation made up a relatively small proportion of average total PAC spending, with little increase across cost quintiles.

EXHIBIT 2.

Components of average total PAC payment, by hospital-level, risk-adjusted, total 90-day PAC quintiles for THR, CABG, and colectomy

SOURCE/NOTES: SOURCE – Author’s analysis of Medicare data. NOTES - Hospitals are placed into quintiles based on their condition-specific, price-standardized total PAC spending. This spending is then displayed as a total of four components: outpatient rehabilitation (OP Rehab), home health (HH), skilled nursing facility (SNF) and inpatient rehabilitation facility (IRF).

Exhibit 2 Data.

| OP Rehab | Home Health | SNF | IRF | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| THR | Low | 346 | 1,466 | 2,524 | 475 |

| Q2 | 412 | 2,250 | 3,396 | 788 | |

| Q3 | 476 | 2,511 | 3,839 | 1,341 | |

| Q4 | 492 | 2,620 | 4,572 | 2,078 | |

| High | 541 | 2,744 | 5,313 | 3,789 | |

| CABG | Low | 217.654 | 1241.42 | 1823.52 | 688.03 |

| Q2 | 227.314 | 1502.83 | 2297.03 | 1182.27 | |

| Q3 | 206.934 | 1602.24 | 2610.45 | 1688.99 | |

| Q4 | 201.421 | 1798.77 | 3050.98 | 2230.35 | |

| High | 188.841 | 1935.75 | 3373.54 | 3794.1 | |

| Colectomy | Low | 20.3311 | 971.22 | 1944.45 | 311.73 |

| Q2 | 22.2614 | 1064.32 | 2313.84 | 477.01 | |

| Q3 | 22.3548 | 1174.28 | 2627.76 | 592.15 | |

| Q4 | 22.8609 | 1261.27 | 3104 | 803.69 | |

| High | 23.611 | 1383.47 | 3832.88 | 1443.72 |

Variation in price-standardized, risk-adjusted PAC payments was largely due to choice of PAC setting, rather than PAC intensity (Exhibit 3). For THR, actual Medicare payments averaged $4,608 in Q1 to $12,765 in Q5, for a difference of $8,157. When payments were price-standardized, the difference shrunk to $7,345 or 153% of Q1. This was because hospitals in Q1 were more likely to be in regions where prices for a given service were lower than hospitals in Q5. Thus, holding prices across regions constant, payments in Q1 increased and payments in Q5 decreased, and the difference between Q5 and Q1 narrowed. Similarly, when additionally holding case mix constant, the difference between PAC payments in Q1 and Q5 shrunk further to $6,596 or 129% of Q1. This was because hospitals in Q1 were more likely to care for patients that were not as sick as patients in Q5. Additionally adjusting for intensity once discharged to a PAC setting marginally decreased the difference across PAC spending quintiles ($5,856, or 109% of Q1). In contrast, adjusting for choice of PAC setting substantially reduced hospital variation in PAC spending ($1,162 or 16% of Q1). Similarly, for CABG and colectomy, adjusting for PAC intensity reduced variation considerably less than adjusting for choice of PAC setting (CABG: 108% vs. 4%; colectomy: 62% vs. 21%).

EXHIBIT 3.

Average total PAC payments for episodes of three common inpatient procedures, 2009 to 2012

| Procedure | Total payments, by hospital quintile, $s

|

Q5 minus Q1

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (low cost) | 5 (high cost) | $s | % of Q1 | |

| Hip replacement | ||||

|

| ||||

| Actual cost | 4,608 | 12,765 | 8,157 | 177 |

|

| ||||

| Plus price adjustment | 4,789 | 12,134 | 7,345 | 153 |

|

| ||||

| Plus case-mix adjustment | 5,112 | 11,708 | 6,596 | 129 |

|

| ||||

| Plus intensity or setting adjustment | ||||

|

| ||||

| Intensity adjustment | 5,379 | 11,235 | 5,856 | 109 |

|

| ||||

| Setting adjustment | 7,053 | 8,215 | 1,162 | 16 |

|

| ||||

| Coronary artery bypass grafting | ||||

|

| ||||

| Actual cost | 3,635 | 10,141 | 6,506 | 179 |

|

| ||||

| Plus price adjustment | 3,825 | 9,314 | 5,489 | 143 |

|

| ||||

| Plus case-mix adjustment | 4,143 | 8,403 | 4,260 | 103 |

|

| ||||

| Plus intensity or setting adjustment | ||||

|

| ||||

| Intensity adjustment | 4,198 | 8,716 | 4,518 | 108 |

|

| ||||

| Setting adjustment | 5,756 | 5,976 | 220 | 4 |

|

| ||||

| Colectomy | ||||

|

| ||||

| Actual cost | 2,780 | 7,368 | 4,588 | 165 |

|

| ||||

| Plus price adjustment | 2,917 | 6,937 | 4,020 | 138 |

|

| ||||

| Plus case-mix adjustment | 3,345 | 6,104 | 2,758 | 82 |

|

| ||||

| Plus intensity or setting adjustment | ||||

|

| ||||

| Intensity adjustment | 3,683 | 5,980 | 2,297 | 62 |

|

| ||||

| Setting adjustment | 3,871 | 4,669 | 798 | 21 |

SOURCE/NOTES: SOURCE – Author’s analysis of Medicare data. NOTES - Price-standardized payments, by hospital quintiles based price-standardized but NOT risk-adjusted payments. Abbreviations: PAC is post-acute care.

We further examined how choice vs. intensity affected overall PAC spending for each PAC setting (Exhibit 4). The proportion of patients utilizing an IRF explained one-quarter to one-half of the variation in total PAC spending (THR: $2,513 or 32% of the total variation in PAC spending between the highest and lowest cost quintiles; CABG: $2,809 (52%); and colectomy: $979 (26%)). Together, the choice to use an IRF or SNF explained one-half to three-quarters of all variation in total PAC spending. In contrast, differences in payment once at a given PAC setting were small.

EXHIBIT 4.

Proportion of total hospital-level variation in PAC payment explained by PAC setting among Medicare beneficiaries who underwent THR, CABG, or colectomy, from 2009 to 2012

| Type of Post-acute Care | THR

|

CABG

|

Colectomy

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| $s | % of Total Variation | $s | % of Total Variation | $s | % of Total Variation | |

| IRF | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Present/absent | 2,513 | 32 | 2,809 | 52 | 979 | 26 |

|

| ||||||

| Payment if present | 25 | 0 | 27 | 0 | 129 | 3 |

|

| ||||||

| SNF | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Present/absent | 1,228 | 16 | 1,006 | 18 | 937 | 25 |

|

| ||||||

| Payment if present | 531 | 7 | 327 | 6 | 733 | 20 |

|

| ||||||

| HH | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Present/absent | 625 | 8 | 700 | 13 | 411 | 11 |

|

| ||||||

| Payment if present | 262 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 71 | 2 |

|

| ||||||

| OP Rehab | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Present/absent | 16 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

|

| ||||||

| Payment if present | 62 | 1 | 44 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

|

| ||||||

| Explained Variation | 5,262 | 67 | 4,824 | 88 | 3,253 | 88 |

|

| ||||||

| Unexplained Variation | 2,548 | 33 | 630 | 12 | 441 | 12 |

|

| ||||||

| Total Variation in PAC Spending between High vs. Low Total PAC Spending Quintiles | 7,810 | 100 | 5,454 | 100 | 3,694 | 100 |

SOURCE/NOTES: SOURCE – Author’s analysis of Medicare data. NOTES - Abbreviations: PAC is post-acute care, THR is total hip replacement, CABG is coronary artery bypass grafting, HH is home health, SNF is skilled nursing facility, IRF is inpatient rehabilitation facility, OP Rehab is outpatient rehabilitation.

The correlation of PAC spending was moderate for all procedure pairings (Appendix Exhibit I).(11) That is, hospitals that had high PAC spending for colectomy also tended to have high PAC spending for THR and CABG.

Discussion

Utilization of PAC after major inpatient surgery is common, but there is wide variation between hospitals in what types of care are provided, and how much is spent. While we found that the majority of patients undergoing THR, CABG, or colectomy utilized some type of PAC in the 90 days following hospital discharge, spending on PAC varied threefold between the highest and lowest spending quintiles of hospitals. Choice of PAC setting explained the majority of total variation in risk-adjusted, price-standardized PAC spending. High-cost hospitals and their patients preferentially chose skilled nursing and inpatient rehabilitation settings. Subsequent to the decision to use a particular PAC setting, the intensity of utilization did not explain meaningful differences in spending.

We found that hospitals that send more of their patients to IRFs, and to a lesser extent SNFs, have higher PAC spending. Our findings make sense in the context of the current PAC payment system. With traditional fee-for-service Medicare, hospitals have not been responsible for payments that occur after hospital discharge. Moreover, for patients discharged to a PAC setting, spending is relatively fixed at IRFs, the most expensive type of PAC. IRFs are paid prospectively per discharge, with adjustments for age, functional and cognitive status, diagnoses, and area prices (24). Although SNFs are paid on a per diem basis,(25) the cost to Medicare of an extra SNF day is small relative to the cost of an extra patient being sent to a SNF. Thus, even though the number of days at a SNF affects total PAC spending via per diem payments (or “intensity”), SNF length of stay still matters less than the choice to send a patient to a SNF in the first place.

These findings – that PAC spending depends more on the type, rather than the intensity of care chosen – provide insight into the causes of PAC spending variation after three common surgical procedures. Prior research has described how PAC spending and variation in PAC spending contributes to condition-specific total episode payments, growth in these payments, and overall national Medicare spending (1, 2, 23, 26–28). Others have examined the value of different PAC settings,(13) and described factors that might lead to higher-value PAC (29–31). Most recently, Huckfeldt et al. examined PAC spending for eight medical conditions and two orthopedic procedures (32) performed in 2007 and 2008. They assessed how much of PAC spending was due to choice of IRF vs. SNF, as opposed to intensity. We build on this work by using more recent data (2009 to 2012) to compare results for total hip replacement (included in their sample) and two other common surgical conditions not included in their sample (i.e., colectomy and CABG)

Finally, our work is also new in that we quantify how much setting vs. intensity contributes to variation in PAC spending, and we include home health and outpatient rehabilitation, two types of care that may partially substitute for SNF or IRF care.

For providers, our findings have at least three implications. First, it is known that SNF length of stay varies, and some health systems have begun efforts to reduce SNF length of stay. Our findings suggest that efforts to reduce SNF length of stay (or “intensity”) will generally have a more modest impact on total PAC spending than efforts to identify which patients will benefit (vs. not benefit) from a SNF or IRF stay in the first place. As noted above, others have found similar patterns in PAC spending with earlier data, albeit for different conditions and a different group of PAC settings. However, providers may now have more incentive to reduce variation in discharges to PAC, given strong interest in ACOs and more widespread adoption of bundled payments. Second, choice of IRF is much more important than choice of SNF in explaining variation in total PAC spending for THR and CABG. This is primarily due to the fact that choice of IRF varies more widely than choice of SNF. The higher reimbursement of IRFs vs. SNFs plays a secondary role. Third, while choice of setting is important, there are differences across conditions. For example, for colectomy, variation in PAC spending is equally explained by choice of IRF, choice of SNF, and intensity of SNF. Thus efforts to reduce SNF LOS may be more effective for certain conditions than other conditions.

For payers and policymakers, our findings regarding the importance of choice of PAC setting, suggest that episodes of care aimed at reducing PAC spending should include the transition from hospital to PAC setting. Episodes of care that include both the index hospital stay and PAC have the best potential to reduce wide variation in PAC spending; episodes of care that include only PAC settings may be less effective. In addition, uniform measures of functional status on hospital discharge and PAC discharge will become increasingly important as patients and providers seek to make high-value PAC choices. CMS has taken the first step in this work by testing the Continuity Assessment Record and Evaluation (CARE) Item Set, a uniform measure set(33). Given differences in length of stay across PAC providers and settings, fixed time points for measurement would be useful. Finally, patients play an important role in the choice of PAC setting and claims data do not capture the myriad factors that may influence patient preference (e.g., social support, availability of high-quality PAC settings). Thus, policymakers should monitor the effects of efforts to reduce PAC utilization, in order to prevent unintended consequences for vulnerable populations, whose need for PAC may not be fully accounted for in existing risk-adjusted measures of PAC utilization.

Use of PAC after major surgery is common for older Americans, but average PAC spending varies widely among hospitals. Understanding when use of IRF or SNF care has value will be critical to reducing any unnecessary variation in PAC spending.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute of Aging (Grant No. P01AG019783).

References

- 1.Chandra A, Dalton MA, Holmes J. Large increases in spending on postacute care in Medicare point to the potential for cost savings in these settings. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32(5):864–72. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mechanic R. Post-acute care--the next frontier for controlling Medicare spending. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(8):692–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1315607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Newhouse JP, Garber AM. Geographic variation in Medicare services. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(16):1465–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1302981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mor V, Intrator O, Feng Z, Grabowski DC. The revolving door of rehospitalization from skilled nursing facilities. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29(1):57–64. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MaCurdy T, Bhattacharya J, Perlroth D, Shafrin J, Au-Yeung A, Bashour H, et al. Geographic variation in spending, utilization and quality: Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries. 2013 [cited 2014 May 29]. Available from: http://iom.edu/Reports/2013/Variation-in-Health-Care-Spending-Target-Decision-Making-Not-Geography/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2013/Geographic-Variation2/Subcontractor-Reports/Updated%20Acumen%20Report.pdf.

- 6.Das A, Norton EC, Miller DC, Ryan AM, Birkmeyer JD, Chen LM. Adding A Spending Metric To Medicare’s Value-Based Purchasing Program Rewarded Low-Quality Hospitals. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35(5):898–906. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Program; comprehensive care for joint replacement payment model for acute care hospitals furnishing lower extremity joint replacement services. Fed Regist. 2015:41197–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Bundled payments for care improvement (BPCI) initiative: general information. [cited 2015 April 5]. Available from: http://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/bundled-payments/

- 9.Tsai TC, Joynt KE, Wild RC, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Medicare’s Bundled Payment initiative: most hospitals are focused on a few high-volume conditions. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015;34(3):371–80. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Notice of proposed rulemaking for bundled payment models for high-quality, coordinated cardiac and hip fracture care. [cited 2016 August 5]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2016-Fact-sheets-items/2016-07-25.html.

- 11.To access the Appendix, click on the Appendix link in the box to the right of the article online.

- 12.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Bundled payments for care improvement initiative fact sheet. 2014 [cited 2014 May 26]. Available from: http://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-Sheets/2014-Fact-sheets-items/2014-01-30-2.html.

- 13.Buntin MB, Colla CH, Deb P, Sood N, Escarce JJ. Medicare spending and outcomes after postacute care for stroke and hip fracture. Med Care. 2010;48(9):776–84. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e359df. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Medicare Payment Advisory Comission. Report to the Congress: Medicare payment policy. [updated March 2014; cited 2015 April 5]. Available from: http://www.medpac.gov/documents/reports/mar14_entirereport.pdf?sfvrsn=0.

- 15.Medicare Payment Advisory Comission. Outpatient therapy services payment system. 2015 [cited 2016 July 24]. Available from: http://www.medpac.gov/documents/payment-basics/outpatient-therapy-services-payment-system-15.pdf?sfvrsn=0.

- 16.Medicare Payment Advisory Comission. Home health care services payment system. 2015 [cited 2016 July 24]. Available from: http://www.medpac.gov/documents/payment-basics/home-health-care-services-payment-system-15.pdf?sfvrsn=0.

- 17.Medicare Payment Advisory Comission. Skilled nursing facility services payment system. 2015 [cited 2016 July 24]. Available from: http://www.medpac.gov/documents/payment-basics/skilled-nursing-facility-services-payment-system-15.pdf?sfvrsn=0.

- 18.Medicare Payment Advisory Comission. Inpatient rehabilitation facilities payment system. 2015 [cited 2016 July 24]. Available from: http://www.medpac.gov/documents/payment-basics/inpatient-rehabilitation-facilities-payment-system-15.pdf?sfvrsn=0.

- 19.Gottlieb DJ, Zhou W, Song Y, Andrews KG, Skinner JS, Sutherland JM. Prices don’t drive regional Medicare spending variations. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29(3):537–43. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oaxaca R. Male-female wage differentials in urban labor markets. Int Econ Rev. 1973;14:693–709. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blinder A. Wage discrimination: reduced form and structural estimates. J Hum Resour. 1973;8:436–45. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gage B, Morley M, Spain P, Ingber M. Examining post acute care relationships in an integrated hospital system. 2009 [cited 2014 May 26]. Available from: http://aspe.hhs.gov/health/reports/09/pacihs/report.shtml#3.9.

- 24.Medicare Payment Advisory Comission. Inpatient rehabilitation facilities payment system. 2015 [cited 2015 April 5]. Available from: http://www.medpac.gov/documents/payment-basics/inpatient-rehabilitation-facilities-payment-system-15.pdf?sfvrsn=0.

- 25.Medicare Payment Advisory Comission. Skilled nursing facility services payment system. 2013 [cited 2015 April 5]. Available from: http://www.medpac.gov/documents/MedPAC_Payment_Basics_13_SNF.pdf.

- 26.Miller DC, Gust C, Dimick JB, Birkmeyer N, Skinner J, Birkmeyer JD. Large variations in Medicare payments for surgery highlight savings potential from bundled payment programs. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30(11):2107–15. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hussey PS, Huckfeldt P, Hirshman S, Mehrotra A. Hospital and regional variation in Medicare payment for inpatient episodes of care. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(6):1056–7. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Birkmeyer JD, Gust C, Baser O, Dimick JB, Sutherland JM, Skinner JS. Medicare payments for common inpatient procedures: implications for episode-based payment bundling. Health Serv Res. 2010;45(6 Pt 1):1783–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01150.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grabowski DC, Feng Z, Hirth R, Rahman M, Mor V. Effect of nursing home ownership on the quality of post-acute care: an instrumental variables approach. J Health Econ. 2013;32(1):12–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Werner R, Stuart E, Polsky D. Public reporting drove quality gains at nursing homes. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29(9):1706–13. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rahman M, Foster AD, Grabowski DC, Zinn JS, Mor V. Effect of hospital-SNF referral linkages on rehospitalization. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(6 Pt 1):1898–919. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huckfeldt PJ, Mehrotra A, Hussey PS. The relative importance of post-acute care and readmissions for post-discharge spending. Health Serv Res. 2016 doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gage B, Constantine R, Aggarwal J, Morley M, Kurlantzick VG, Bernard S, et al. The development and testing of the Continuity Assessment Record and Evaluation (CARE) Item Set: final report on the development of the CARE Item Set. 2012 [cited 2016 July 24]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Post-Acute-Care-Quality-Initiatives/Downloads/The-Development-and-Testing-of-the-Continuity-Assessment-Record-and-Evaluation-CARE-Item-Set-Final-Report-on-the-Development-of-the-CARE-Item-Set-Volume-1-of-3.pdf.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.