Summary

In familial pulmonary arterial hypertension (FPAH) the autosomal dominant disease-causing BMPR2 mutation is only 20% penetrant, suggesting that genetic variation provides modifiers that alleviate the disease. Here, we used comparison of induced pluripotent stem cell derived endothelial cells (iPSC-ECs) from three families with unaffected mutation carriers (UMCs), FPAH patients, and gender-matched controls to investigate this variation. Our analysis identified features of UMC iPSC-ECs related to modifiers of BMPR2 signaling or to differentially expressed genes. FPAH-iPSC-ECs showed reduced adhesion, survival, migration and angiogenesis compared to UMC-iPSC-ECs and control cells. The ‘rescued’ phenotype of UMC cells was related to an increase in specific BMPR2 activators and/or a reduction in inhibitors, and the improved cell adhesion could be attributed to preservation of related signaling. The improved survival was related to increased BIRC3 and independent of BMPR2. Our findings therefore highlight protective modifiers for FPAH that could help inform development of future treatment strategies.

Keywords: Pulmonary arterial hypertension, endothelial dysfunction, bone morphogenetic protein receptor 2, unaffected mutation carrier, penetrance, cell adhesion, cell survival, induced pluripotent stem cell derived endothelial cell

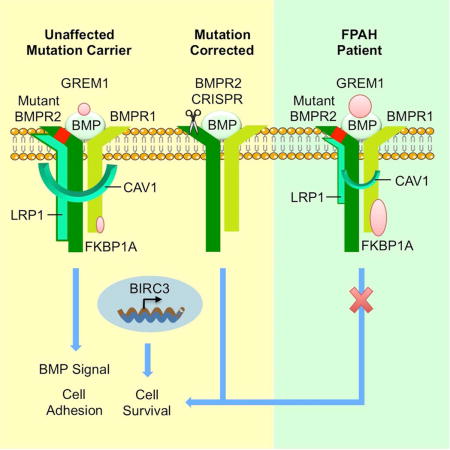

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a disease that causes progressive right heart failure and, in many patients, death or need for transplantation within five years of diagnosis (Rabinovitch, 2012). This is because PAH-specific therapies mainly amplify pulmonary arterial (PA) endothelial cell (EC)-derived vasodilatory mediators. These agents may result in temporary hemodynamic improvement but are limited in reversing pulmonary vascular remodeling characterized by EC dysfunction, loss of the most peripheral PA microvessels and proliferation of vascular cells in more proximal PAs, leading to occlusion of the lumen.

Fifteen percent of PAH patients have a familial form of the disease (FPAH) and among those, 70% carry an autosomal dominant mutation causing haploinsufficiency or loss of function of bone morphogenetic protein receptor 2 (BMPR2)(Lane et al., 2000). This mutation is also present in 20% of sporadic cases of idiopathic (I)PAH. Mutations in other receptors of the TGF-β superfamily, such as activin-like kinase-type 1 (Harrison et al., 2003) and endoglin (Chaouat et al., 2004), and mutations that affect BMP signaling such as SMAD9 (Drake et al., 2013), CAV1 (Austin et al., 2012), and potassium channel subfamily K member 3 (KCNK3) (Ma et al., 2013) have also been described.

Intriguingly, in FPAH families, only 20% of the BMPR2 mutation carriers develop clinical symptoms. Various factors have been linked to the low penetrance: a TGF-β1 polymorphism (Phillips et al., 2008), lower BMPR2 expression from the wild-type allele (Hamid et al., 2009), reduced expression of the estrogen metabolizing gene CYP1B1 (West et al., 2008), reactive oxygen species formation (Flynn et al., 2012), and higher levels of an alternatively spliced BMPR2 transcript (Cogan et al., 2012). However, how these potentially adverse patient-specific modifiers are related to the cellular dysfunction linked to FPAH remains speculative.

Dysfunction of PA ECs plays a central role in the initiation and progression of PAH. Previous studies have demonstrated that impaired BMP signaling in PA ECs is associated with decreased cell survival in response to injury (de Jesus Perez et al., 2009), impaired adhesion and migration (de Jesus Perez et al., 2012; Rhodes et al., 2015), and disordered angiogenesis (Tuder and Voelkel, 2002), as well as reduced production of vasodilators and increased production of vasoconstrictor agents (Budhiraja et al., 2004).

Due to the limited access to native PA ECs from FPAH patients, and no access from unaffected mutation carriers (UMCs), we reasoned that induced pluripotent stem cell derived-ECs (iPSC-ECs) could provide a unique platform to model the propensity to FPAH ‘in-a-dish’. Several groups have reported the feasibility of using patient-specific iPSCs to study human vascular diseases (Ge et al., 2012), and iPSC-ECs in particular were applied to study congenital valve abnormalities related to impaired Notch signaling (Theodoris et al., 2015).

In this study, we utilized human iPSC-ECs from three families to compare those from UMC, FPAH patients and gender-matched controls. Our objective was to find protective modifiers of the BMPR2 mutation in UMC that are responsible for normal cellular function and that might inform the development of prospective PAH treatment strategies. We found that in UMC iPSC-ECs, an increase in BMPR2 activators and a reduction in inhibitors explain preservation of many EC functions. Others, such as improved EC survival, appear to be BMPR2 independent and identified on RNA-Seq analyses as related to heightened expression of BIRC3 in UMC vs. FPAH iPSC-ECs. CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing of the BMPR2 mutation reversed the EC dysfunction, supporting the premise that, in the absence of protective modifiers, the BMPR2 mutation is sufficient for EC dysfunction associated with PAH.

Results

EC Morphology and BMPR2 Expression are Similar in UMC and FPAH iPSC-ECs

Eleven individuals were recruited from three FPAH families. Each family was characterized by a different BMPR2 mutation, and included one to three FPAH patients and one UMC. We used one gender-matched subject without cardiovascular disease as a control for each family. The controls were obtained from collaborating investigators in the PHBI Network (Table S1). Skin fibroblasts from each individual were reprogrammed to iPSCs by lentivirus (Families 1 & 2 and controls), or by Sendai virus (Family 3). iPSC clones stained positive for pluripotent markers OCT4, KLF4, NANOG, SOX2, TRA-1-81 and SSEA4 (Figure S1A).

Patient-specific iPSCs were then differentiated into ECs using a monolayer differentiation protocol previously published (Gu et al., 2015). On day 10 of the differentiation process, FACS analysis showed that ~75% of the cell population expressed the mature EC surface marker CD144, ~20% of the cells stained positive for the endothelial progenitor cell marker CD34, and none of cells expressed the early mesoderm marker KDR (Figure S1B). No differences were observed in the differentiation efficiency of iPSCs from control, UMC and FPAH individuals (Figure S1C), despite the BMP signaling pathway playing an important role in mesoderm differentiation. iPSC-ECs from all subjects showed similar EC cobblestone morphology, acetylated LDL uptake and VE Cadherin (CD144) immunostaining (Figure 1A). We found that venous gene expression levels were lower in all the iPSC-ECs compared to human umbilical venous endothelial cells (HUVECs), while arterial genes were higher in iPSC-ECs versus HUVECs, indicating that the iPSC-ECs were more arterial than venous. The two arterial markers, EFNB2 and ALK1 that were lower in UMC and FPAH iPSC-ECs relative to control iPSC-ECs, were still higher than in HUVECs (Figure S1D).

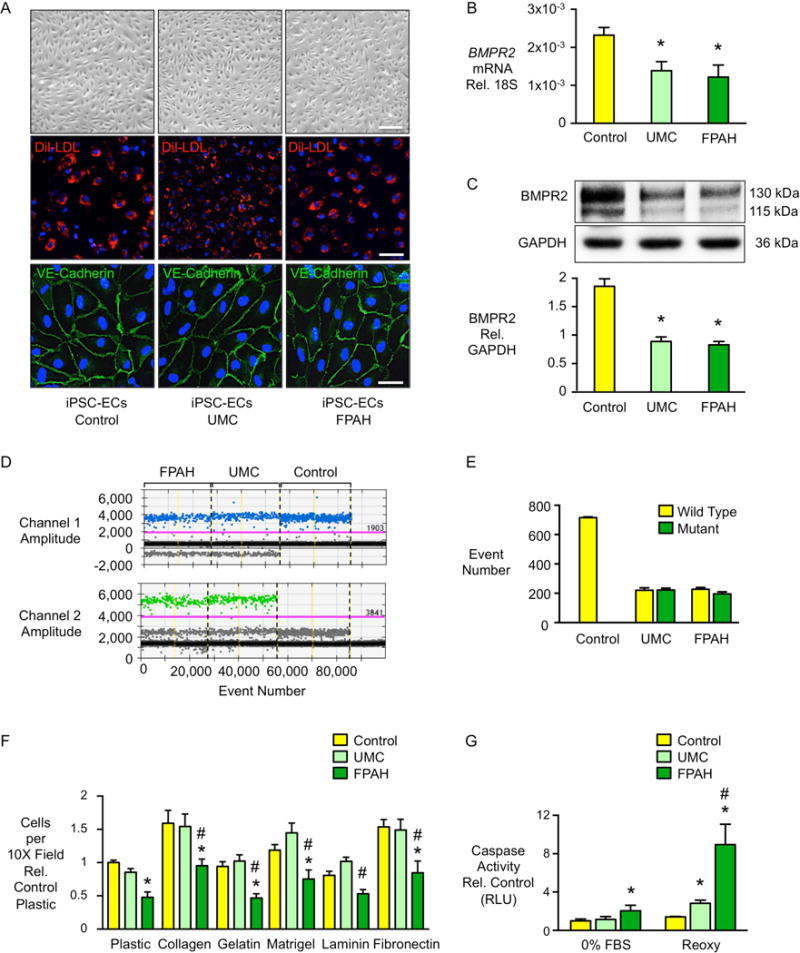

Figure 1. FPAH iPSC-ECs Show Similar Morphology and BMPR2 Expression but Impaired Adhesion and Survival, Compared with UMCs.

(A) Endothelial cells (ECs) differentiated from skin fibroblast derived iPSCs exhibit typical cobblestone morphology, incorporate 3,3′-dioctadecylindocarbocyanine labeled low-density lipoprotein (Dil-LDL, red) and are positive for the EC surface marker VE-Cadherin (green). Blue: DAPI. Scale bar=100μm (top), 50μm (middle) and 10μm (bottom). (B) BMPR2 gene expression quantified by real-time PCR and (C) western immunoblot and densitometric quantification of BMPR2 protein in iPSC-ECs from controls, UMCs and FPAH patients in three families. (D–E) Allele specific BMPR2 expression measured by droplet digital PCR. Probe for wild-type allele was labeled by FAM (blue dots), and for mutant allele by HEX (green dots). Data represented missense mutations from family 1 and 3 and deletion mutation from family 2. (F) iPSC-ECs (10,000/well) were seeded onto 24-well plates either uncoated (plastic) or coated with the indicated matrices and allowed to adhere for one hour. Non-adherent cells in suspension were removed, adherent cells were washed with PBS then stained with Hoechst and imaged. The average number of nuclei was calculated by counting the total number in six random fields per well (10× magnification). (G) iPSC-ECs were exposed to either serum withdrawal overnight (0% FBS) or reoxygenation [Reoxy, 48h in hypoxia, (0.5%O2) followed by 48h at room air]. Apoptosis was measured by Caspase-Glo® 3/7 Assay. Bars represent mean±SD from n=3 families, 3 biological replicates per family. *p<0.05 vs. control, #p<0.05 vs. UMC, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post test. See also Figure S1 and Figure S2.

Moreover, we found that iPSC-ECs from UMCs and FPAH patients had a similar reduction in BMPR2 mRNA (Figure 1B) and protein (Figure 1C) compared to the control iPSC-ECs. Using droplet digital PCR, we found that control iPSC-ECs only expressed BMPR2 transcripts from the wild-type allele, while both UMCs and FPAH patients expressed similar levels of wild-type and mutant copies (Figure 1D–E). These results indicate that BMPR2 allele specific gene expression does not distinguish the UMCs from the FPAH patients in these families.

Impaired Cell Adhesion and Survival Distinguish FPAH iPSC-ECs

We then investigated whether there were EC properties that could distinguish UMC from FPAH or control iPSC-ECs. Four functional assays were carried out based upon previous studies showing that these features were impaired in PAH PA ECs (Alastalo et al., 2011; de Jesus Perez et al., 2012; Diebold et al., 2015; Nickel et al., 2015). We observed that cell adhesion to a wide variety of extracellular matrix substrates (Figure 1F), and cell survival measured by reduced caspase activity either after serum withdrawal or following reoxygenation after hypoxia (Diebold et al., 2015) (Figure 1G), were preserved in UMC iPSC-ECs in that values were similar to those in control cells, whereas these functions were significantly impaired in FPAH iPSC-ECs. Cell migration and tube formation in matrigel, were similarly impaired in iPSC-ECs from both UMCs and FPAH patients compared with controls (Figure S2A–B). However, when iPSC-ECs were stimulated with BMPR2 ligand BMP4, cell migration and angiogenesis were significantly improved in UMC iPSC-ECs with values similar to those in control iPSC-ECs, whereas these features remained impaired in iPSC-ECs from FPAH patients (Figure S2C–D). This suggested that some potential for vulnerability existed in the UMC relative to control phenotype, but this could be overcome by stimulation of the BMPR2 pathway.

pSMAD1/5-ID1 and p-p38 Signaling Pathways Distinguish FPAH iPSC-ECs

We next determined whether compensatory BMPR2 signaling was responsible for preservation of normal UMC iPSC-EC functions. PAH PA ECs with reduced BMPR2 expression show impaired canonical BMPR2 signaling (pSMAD1/5-ID1) in response to BMP4 treatment (Spiekerkoetter et al., 2013), a feature reproduced in FPAH iPSC-ECs from all three families (Figure S3A–C). However, this pathway appeared hyperresponsive in the Family 1 UMC iPSC-ECs, as assessed in two different iPSC clones (Figure S3A, D). In family 2, pSMAD1/5-ID1 activation in the UMC was intermediate between control and FPAH iPSC-ECs (Figure S3B). In Family 3, however, iPSC-ECs from UMC were similar to those from the FPAH subject in their lack of pSMAD1/5-ID1 response to BMP4 (Figure S3C). As ECs respond to BMPs by activating multiple signaling pathways, we also investigated the pERK and pAkt in response to BMP4, but these iPSC-ECs did not show a consistent activation of these signaling molecules (data not shown).

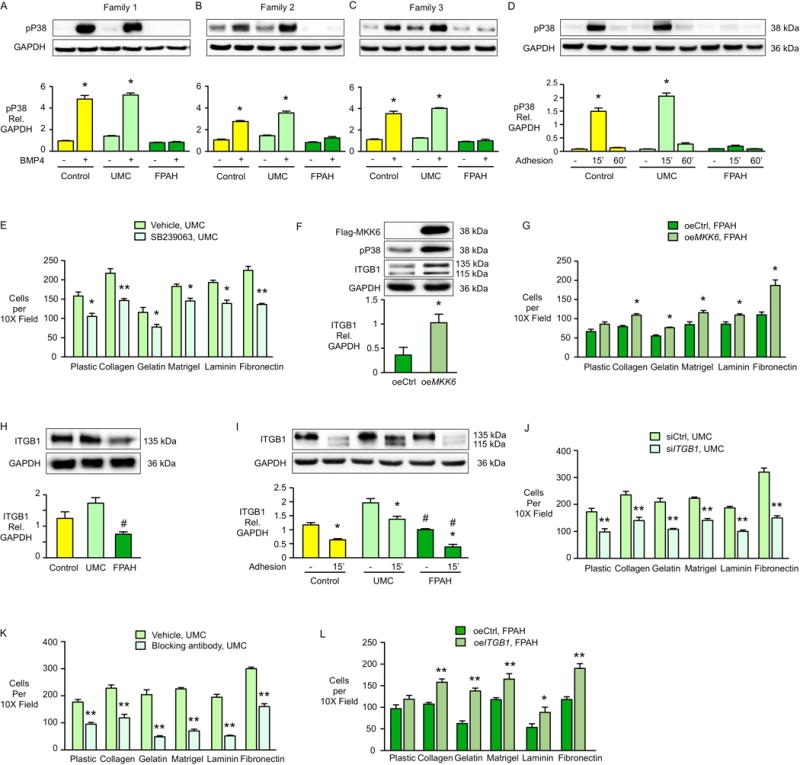

The non-canonical pP38 signaling pathway plays an important role in cell adhesion and survival (Gutierrez-Uzquiza et al., 2012; Harper et al., 2005). This pathway was consistently activated in response to BMP4 in iPSC-ECs from both controls and UMCs, but not in FPAH iPSC-ECs from the three families (Figure 2A–C), including all three patients in family 1 (Figure S3E). We also monitored pP38 activation under conditions of iPSC-EC adhesion (Figure 2D). In all three families, FPAH iPSC-ECs showed non-detectable pP38 when compared to the UMC and control iPSC-ECs, where a similar pronounced activation was observed. To confirm the role of pP38 signaling in cell adhesion, gain and loss of function of pP38 were performed in iPSC-ECs from family 1. When pP38 was blocked with the inhibitor SB239063, cell adhesion to six different matrices was significantly decreased in the UMC iPSC-ECs, but not to the patient level (Figure 2E). Conversely, when we induced constitutive activation of pP38 following transfection with MKK6, the kinase upstream of pP38 (Figure 2F), adhesion was increased in FPAH iPSC-ECs, albeit not to the control level (Figure 2G), thus demonstrating that compensatory pP38 signaling in UMCs can confer a protective phenotype.

Figure 2. UMC iPSC-ECs Show Preserved pP38 Signaling and Incresed ITGB1, Leading to Improved Cell Adhesion.

(A–C) Representative western immnoblots above and densitometric analyses for pP38 in iPSC-ECs from three families one hour after BMP4 (10ng/ml) stimulation. or PBS as vehicle. (D) Representative western immunoblots above and densitometric analyses of pP38 activation following iPSC-EC adhesion to a plastic surface for 15 and 60 min (n=3 families, 3 biological replicates per family). (E) iPSC-ECs from UMC (family 1) were pretreated with the pP38 inhibitor SB239063 for 30 min and adhesion of cells to the indicated substrates for one hour was measured as described in Figure 1F. Bars represent mean±SD from n=3 experiments. (F–G) iPSC-ECs from the FPAH patient were transfected with MKK6 construct (oeMKK6) for four days. oeCtrl: iPSC-ECs transfected with empty construct. (F) Representative western immunoblot and densitometry shows pP38 and β1-integrin (ITGB1) levels following cell adhesion assay (G) performed as in Figure 1F. Representative western immunoblot and densitometry shows integrin β1 (ITGB1) under baseline (H) or cell adhesion condition (I). Upper band is mature form of β1-integrin and lower band is the precursor (Salicioni et al., 2004). (J) UMC iPSC-ECs were treated with control siRNA (siCtrl) or ITGB1 siRNA (siITGB1). Cell adhesion was assessed four days later. (K) UMC iPSC-ECs were pretreated with ITGB1 blocking antibody (Anti-Human CD29, clone Mab13, 20μg/ml) for 60 min. at 37°C, and adhesion of cells to the substrates for one hour was measured as previously described. (L) ITGB1 was over-expressed in the FPAH iPSC-ECs and cell adhesion assessed four days later.

Bars represent Mean±SD from n=3 experiments. (A–D, I) *p<0.05 vs. vehicle, #p<0.05 vs. same condition in UMC, two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test. (E, G, J-L) *p<0.05, **p<0.01 vs. vehicle, oeCtrl or siCtrl, t test. (F) *p<0.05 vs. oeCtrl, unpaired t test. (H) #p<0.01 vs. UMC, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test. See also Figure S3.

To further elucidate how preserved pP38 signaling improves cell adhesion, we measured the level of the β1-integrin (ITGB1), a cell adhesion receptor that interacts with a variety of extracellular matrices such as fibronectin, laminin, and Type IV collagen (Languino et al., 1989; Leavesley et al., 1993). Interestingly, the expression of ITGB1 was significantly lower in the iPSC-ECs from FPAH patients compared with UMCs and controls in all three families (Figure 2H). Under cell adhesion condition, ITGB1 was recycled faster and stabilized in iPSC-ECs from UMC compared with FPAH patients, indicated by increased levels of both the mature and precursor form of the protein as previously described (Salicioni et al., 2004) (Figure 2I). To further understand the role of ITGB1 in adhesion of iPSC-ECs, we performed loss and gain of function experiments and found that with knockdown of ITGB1 (Figure S3F), adhesion of UMC iPSC-ECs was decreased (Figure 2J). Similar results were evident with ITGB1 blocking antibody (Figure 2K). Conversely, when we over-expressed ITGB1 in FPAH iPSC-ECs (Figure S3G), cell adhesion was significantly improved (Figure 2L). We also found that ITGB1 was significantly increased when the FPAH iPSC-ECs expressed constitutively active pP38 via MKK6 (Figure 2F), indicating that ITGB1 is the downstream effector of pP38 mediated cell adhesion.

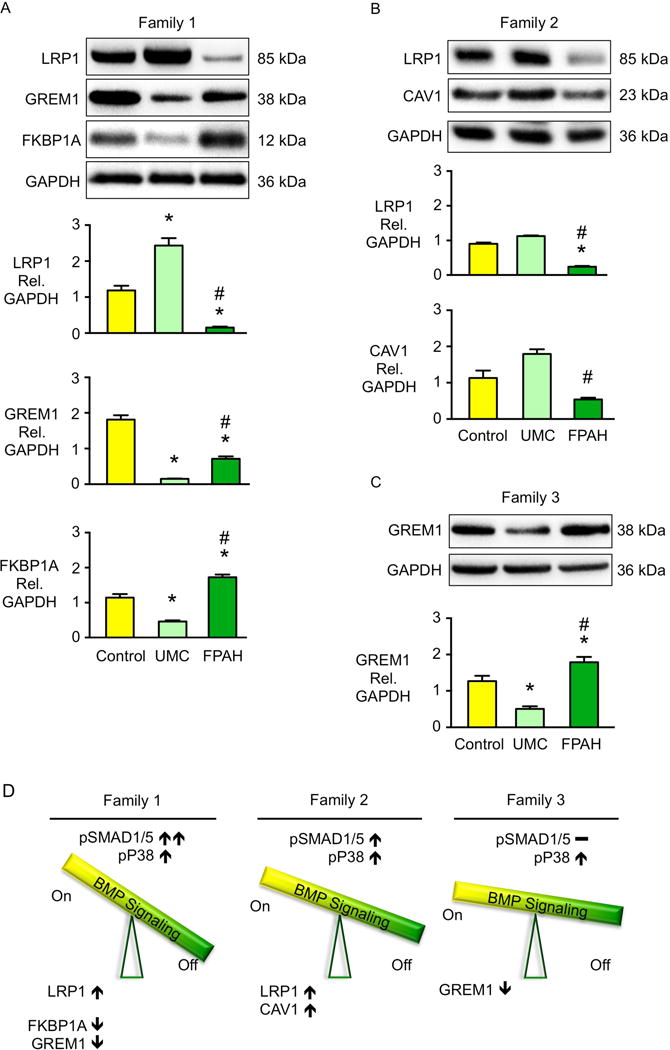

UMCs Express Elevated BMPR2 Activators and Reduced Inhibitors

Next, we took a candidate approach to screen for four regulators of BMPR2 that might account for improved downstream pP38 signaling in the UMCs: (i) BMPR2 activator low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1) recycles the BMP ligand-receptor complex back to the cell surface (Pi et al., 2012), and promotes ITGB1 maturation and transport to the cell membrane (Salicioni et al., 2004); (ii) BMPR2 activator caveolin1 (CAV1) stabilizes BMPR2, increasing downstream pSMAD1/5-ID1 signaling (Nickel et al., 2015); (iii) BMPR2 inhibitor FK506 Binding Protein 12 (FKBP1A), binds to type I receptors, blocking their phosphorylation by BMPR2 (Spiekerkoetter et al., 2013); (iv) BMPR2 inhibitor Gremlin1 (GREM1), interacts with BMP ligands BMP2, 4, 7 and blocks their activation of the BMPR2 receptor (Cahill et al., 2012).

In family 1, the BMPR2 activator LRP1 was markedly increased in UMC compared to FPAH iPSC-ECs, and two BMPR2 signaling repressors, GREM1 and FKBP1A, were reduced (Figure 3A). The other BMPR2 activator, CAV1, showed similar expression levels in UMC and FPAH iPSC-ECs (Figure S4A). The mRNA levels were consistent with protein for these agonists and antagonists of BMPR2 (Figure S4D–F). In family 2, two BMPR2 activators, LRP1 and CAV1 (Figure 3B) were increased in UMC vs. FPAH iPSC-ECs, while GREM1 and FKBP1A were similarly expressed (Figure S4B). In family 3, the BMP ligand inhibitor GREM1 was reduced in the UMC vs. FPAH iPSC-ECs (Figure 3C) but FKBP1A, CAV1 and LRP1 were not significantly changed (Figure S4C). Figure 3D summarizes differences in heightened levels of activators and reduced levels of inhibitors could account for the compensatory BMPR2 mediated pSMAD1/5 and pP38 activation in three families.

Figure 3. Elevated Expression of BMPR2 Activators and Reduced Expression of Inhibitors in BMPR2 UMCs.

(A–C) Representative western immunoblots on top and densitometric analyses below showing BMP regulators in iPSC-ECs from controls, UMCs and FPAH patients in the three different families. Bars represent mean±SD from n=3 biological replicates. *p<0.05 vs. control, #p<0.05 vs. UMC by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni multiple comparisons test. (D) Diagram shows the balance of the BMP regulators related to pSMAD1/5-ID1 signaling and pP38 signaling in the iPSC-ECs from UMC. See also Figure S4.

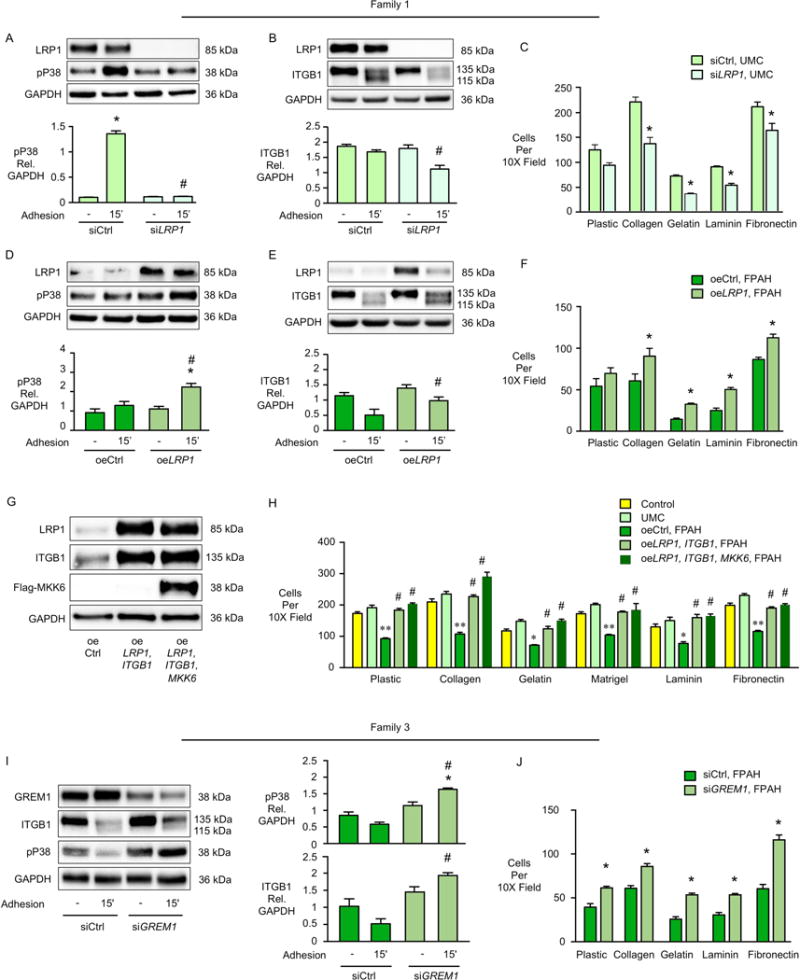

BMPR2 Regulators Explain Compensatory BMP Signaling and Cell Adhesion

To further demonstrate the protective role of LRP1, we transfected UMC iPSC-ECs from Family 1 with LRP1 vs. scrambled control siRNA. Activation of pP38 was reduced in UMC iPSC-ECs with loss of LRP1 either in response to BMP4 stimulation (Figure S5A) or following cell adhesion (Figure 4A). The canonical BMPR2 signaling pSMAD1/5-ID1 was also decreased when LRP1 levels were reduced in UMC iPSC-ECs (Figure S5A). In addition, when LRP1 was reduced in UMC iPSC-ECs, both ITGB1 recycling (Figure 4B) and cell adhesion (Figure 4C) were decreased. Conversely, when LRP1 was over-expressed in the FPAH iPSC-ECs, activation of pP38 in response to BMP4 (Figure S5B) and to cell adhesion, (Figure 4D), ITGB1 recycling (Figure 4E), and cell adhesion to different matrices (Figure 4F) were all significantly improved. However, cell adhesion of FPAH iPSC-ECs was not fully restored to the UMC or control levels with overexpression of LRP1 alone. In view of the low baseline levels of ITGB1 in FPAH cells from all three families (Figure 2H), we co-transfected the FPAH iPSC-ECs with either LRP1 and ITGB1, or LRP1, MKK6 and ITGB1, and found that under both conditions, cell adhesion of FPAH iPSC-ECs were normalized to the control level (Figure 4G, H), indicating that both the total amount and selective LRP1 or pP38 mediated activation and recycling of ITGB1 are necessary in regulating cell adhesion of FPAH iPSC-ECs.

Figure 4. Compensatory pP38 Signaling and Cell Adhesion in UMCs Are Related to BMP Regulators.

(A–C) UMC iPSC-ECs were treated with control siRNA (siCtrl) or LRP1 siRNA (siLRP1) and measurements were made four days later. Representative western immunoblots on top and densitometry below for (A) pP38 (B) ITGB1 15min after cell adhesion to plastic; (C) Cell adhesion was measured as described in Figure 1. (D–F) LRP1 was over-expressed in the FPAH iPSC-ECs. Four days later we assessed (D) pP38 (E) ITGB1 15min after adhesion to plastic; (F) Cell adhesion. oeCtrl: iPSC-ECs transfected with empty construct. oeLRP1: iPSC-ECs transfected with construct over-expressing LRP1. (G-H) Co-transfection of LRP1 and ITGB1 or LRP1, ITGB1 and MKK6 was performed in FPAH iPSC-ECs and measurements were made four days later. (G) Representative western immunoblots and densitometry for LRP1, ITGB1 and Flag-MKK6; (H) Cell adhesion was measured as in Figure 1. (I, J) FPAH iPSC-ECs from family 3 were treated with Control or GREM1 siRNA and measurements were made four days later. (I) Representative western immunoblots (left) and densitometry (right) for ITGB1 and pP38 15min after cell adhesion to plastic; (J) Cell adhesion was measured as described in Figure 1.

Bars represent mean±SD from n=3 experiments. (A–B, D–E, I) *p<0.05 vs. Vehicle, #p<0.05 vs. siCtrl or oeCtrl Adhesion 15′, two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test. (H) *p<0.05 **p<0.01 vs. Control, #p<0.05 vs. oeCtrl, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test. (C, F, J) *p<0.05 vs. siCtrl or oeCtrl, t-test. See also Figure S5.

In addition, since LRP1 was also decreased in FPAH vs. UMCs iPSC-ECs in family 2, we over-expressed LRP1 in the patient cells and found as in family 1- significantly improved pP38 signaling, ITGB1 recycling (Figure S5C), and cell adhesion to extracellular matrices (Figure S5D). In family 3, iPSC-ECs from UMC and FPAH showed similar LRP1 levels, but the BMP inhibitor GREM1 was reduced in the UMC iPSC-ECs. To test the role of reduced GREM1 in improving BMP signaling and EC function in the Family 3 UMC, we reduced GREM1 in the PAH iPSC-ECs using siRNA, and found that pP38 signaling, recycling of ITGB1 and cell adhesion were all improved compared with siControl (Figure 4 I, J). Taken together, although the combination of protective modifiers was different in each family, they all improved pP38 signaling and ITGB1 recycling, and together with higher ITGB1 expression, accounted for the preserved cell adhesion of UMC iPSC-ECs.

Preserved Survival of UMC iPSC-ECs is Not Regulated by BMPR2 Pathway

We could not however show that the same pathway that preserved adhesion in the UMC iPSC-ECs was also responsible for preserved cell survival following serum withdrawal or reoxygenation after hypoxia (Diebold et al., 2015) in the UMC vs. FPAH iPSC-ECs. There were no significant differences in pSMAD1/5, pP38, pERK, and pAKT in iPSC-ECs from controls, UMC and FPAH iPSC-ECs under serum withdrawal or reoxygenation after hypoxia (data not shown). Furthermore, when LRP1 or ID1 was reduced by siRNA in the UMC iPSC-ECs, caspase activity remained unchanged (Figure S5E–F).

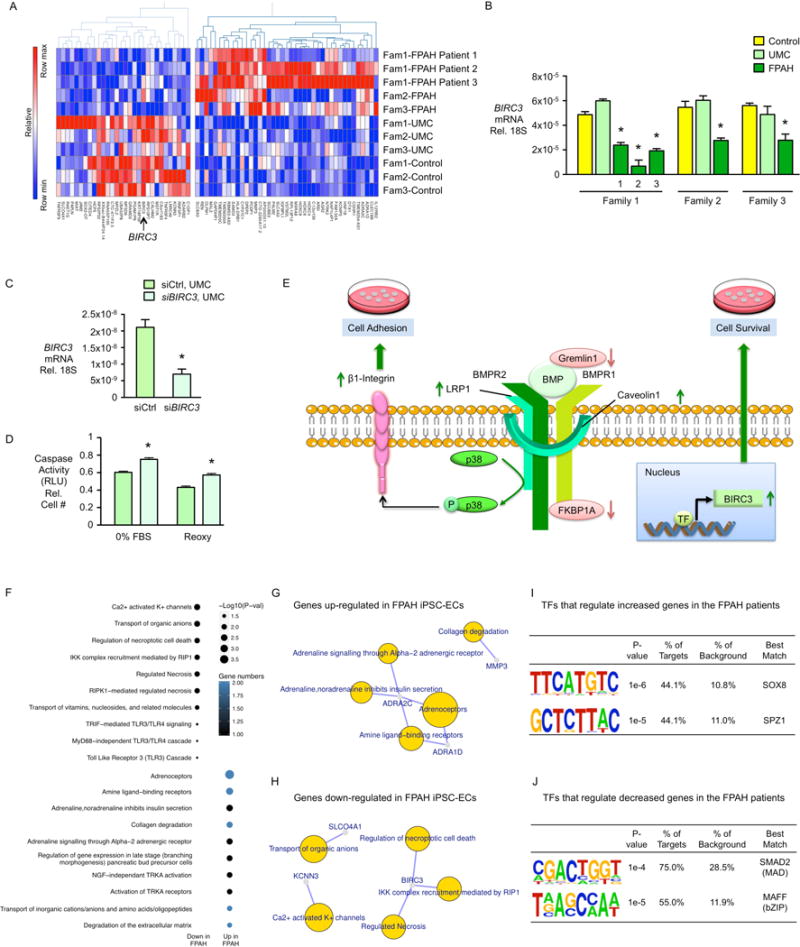

RNA-Seq Analysis Identifies Increased BIRC3 in UMC versus FPAH iPSC-ECs

To uncover a pathway leading to preserved cell survival in the UMC iPSC-ECs, RNA Sequencing (RNA-Seq) was carried out on all iPSC-EC lines (Table S1, n=11) as previously described (Lin et al., 2014). First we combined all the lines from three families to find common genes that might explain the preserved cell survival in all the UMCs. RNA-Seq analyses showed that 71 genes were differentially expressed, mostly by greater than two fold, in FPAH iPSC-ECs compared with those from UMCs and controls (Figure 5A). Among those were transcripts associated with endothelial function and pulmonary arterial hypertension.

Figure 5. Gene Expression Analysis by RNA-Seq.

(A) Heatmap displaying 71 DEGs between controls and UMCs vs. patients (n=11, p<0.01, fold change>2.0). Of these, 41 genes were up-regulated and 30 genes were down-regulated. (B) Quantitative real-time PCR of BIRC3 gene expression in FPAH patients. (C) BIRC3 gene expression reduced by siRNA. (D) Caspase activity of iPSC-ECs from UMCs treated by siBIRC3 in response to serum withdrawal (0%FBS) and reoxygenation after hypoxia (Reoxy). (E) Proposed Model: Compensatory Mechanisms in UMCs. Increased BMPR2 activators LRP1 and/or Caveolin1, and decreased BMPR2 repressors, Gremlin1 that blocks the BMP ligands and/or FKBP12 (FKBP1A) that blocks the BMPR2 type 1 co-receptor (BMPR1), enhance the downstream pP38 signaling pathway, improve β1- integrin recycling. Together with increased total amount of β1-integrin, these features lead to compensatory cell adhesion to a variety of extracellular matrices. Additionally, increased BIRC3 gene expression results in preserved cell survival in response to serum withdrawal and reoxygenation after hypoxia. These features protect the UMCs against the EC dysfunction associated with the development of PAH. (F) Functional enrichment analysis was performed with Reactome pathway database (FDR<0.1) using the 71 genes dysregulated in iPSC-ECs from the FPAH patients. (G–H) Gene-concept network displaying the gene names associated with the top signaling pathways identified in (F). (I, J) Transcription factor (TF) motif enrichment analysis of RNA-Seq: Distribution of the putative occupancy sites of TF was tested within 3kb ± transcription start site of the differentially expressed genes called by RNA-Seq. Analysis shows a unique overrepresentation of the SMAD2 and MAFF motifs in 75% and 55% of genes down-regulated in FPAH iPSC-ECs, and an overrepresentation of SOX8 and SPZ1 motifs in 44.1% of genes up-regulated in FPAH iPSC-ECs.

Bars represent mean±SD from n=3 experiments. (B) *p<0.05 vs. UMC, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test. (C, D) *p<0.05 vs. siCtrl, unpaired t test. See also Figure S6 and Figure S7.

BIRC3 (Baculoviral IAP Repeat Containing 3) encodes a protein that maintains EC survival, was significantly decreased in FPAH relative to both UMCs and control iPSC-ECs as confirmed by qRT-PCR (Figure 5A–B). To determine whether high BIRC3 could be responsible for the preserved cell survival in UMCs, we reduced BIRC3 using siRNA. This resulted in increased activation of caspase, reflecting vulnerability to apoptosis in response to either serum withdrawal or reoxygenation after hypoxia (Figure 5C–D). Figure 5E summarizes the compensatory mechanisms accounting for improved iPSC-EC function in UMC.

Functional enrichment analysis based on the 71 differentially expressed genes identified pathways that are most robustly dysregulated in FPAH iPSC-ECs (Figure 5F) and all were related to EC dysfunction. The pathways included “regulation of necroptotic cell death”, “degradation of extracellular matrix” and “collagen degradation”, “Ca2+ activated K+ channels”(Feletou, 2009), “TLR3/TLR4” cascade” (Bauer et al., 2013) and “adrenoceptors” (Couto et al., 2014). Gene names associated with the top reactome pathways are shown in Figure 5G–H based on gene-concept network analysis. qPCR analysis also verified the expression level of several genes that show the greatest difference between UMC and FPAH cells in all three families (Figure S6A–F).

To investigate whether protective target genes in UMC iPSC-ECs could be mediated by changes in genome occupancy of one or more key transcription factors (TFs), we tested the distribution of putative TF occupancy sites within 3kb of the transcription start site. Interestingly, we found overrepresentation of a SMAD2 motif that regulated 75% of targets that were down-regulated in FPAH iPSC-ECs (Figure 5I–J).

Because family-specific features such as discrepancy of pSMAD1/5-ID1 signaling in UMC and variations in different BMPR2 regulators were identified, we implemented differential expression testing to further determine disease-associated genes in a patient-specific manner. Interestingly, we uncovered several family-specific genes that could explain the common phenotype across the families. For example, in family 1, we found that TNFSF15 (Tumor necrosis factor superfamily 15), a factor that induces apoptosis and inhibits proliferation of ECs (Xu et al., 2014), was significantly increased in all three FPAH iPSC-ECs; In family 2, RTL1 (retrotransposon-like 1), which is essential for the maintenance of the fetal capillaries (Sekita et al., 2008), was decreased in the FPAH iPSC-ECs compared with three controls and one UMC; In family 3, elevated BIRC3 could be the main cause of apoptosis in FPAH iPSC-ECs (Figure S7A–C). These genes were also verified using qPCR (Figure S7D, E).

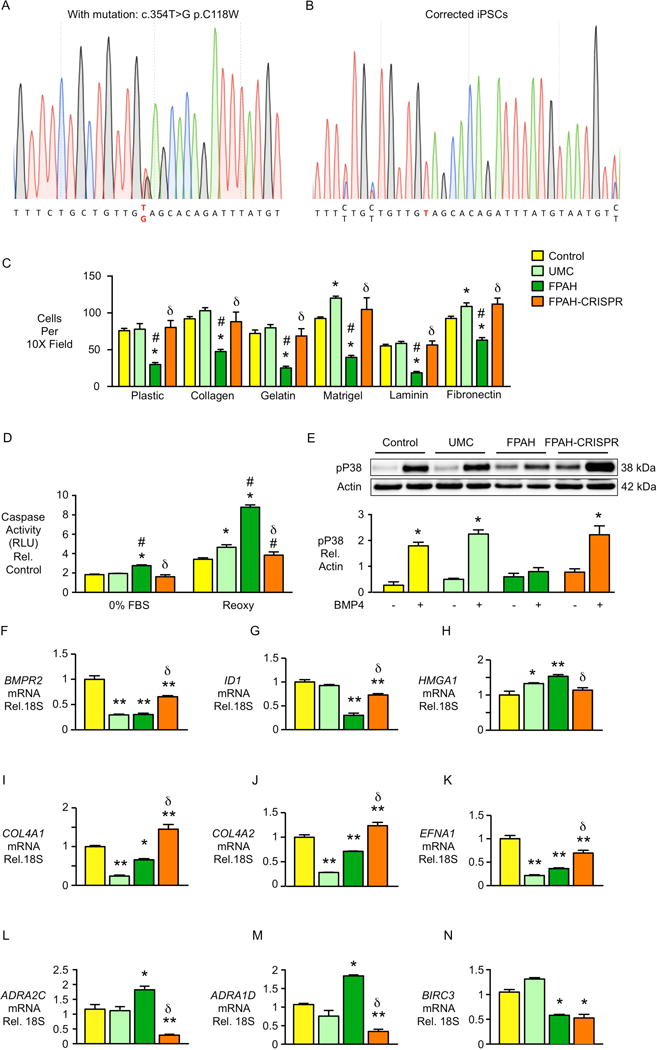

Genome Editing of the BMPR2 Mutation in FPAH iPSC-EC Reverses Dysfunction

To determine the extent to which the BMPR2 mutation account for the iPSC-EC dysfunction in FPAH, the mutation in FPAH iPSCs from family 1 was corrected using CRISPR/Cas9 mediated homology directed repair (Figure 6A–B). Upon differentiation, FPAH iPSC-ECs after BMPR2 correction show control levels of cell adhesion (Figure 6C) and survival in response to either serum withdrawal or after hypoxia and reoxygenation (Figure 6D). The pP38 signaling pathway was also rescued in the edited iPSC-ECs (Figure 6E).

Figure 6. EC Adhesion, Survival, pP38 Signaling and Gene Expression Levels Are Normalized After Gene Editing in iPSC-ECs from Family 1 FPAH Patient.

The BMPR2 mutation in iPSCs from the FPAH patient was corrected using CRISPR/Cas9 mediated homology directed repair. (A) Heterozygous point mutation 354T>G is shown as double peak on the diagram. (B) Following correction of the 354T>G mutation, only a single peak was detected. (C) Adhesion of iPSC-ECs in family 1 after gene editing. (D) Apoptosis of iPSC-ECs assessed by Caspase-Glo® 3/7 Assay. (E) Activation of pP38 signaling 1h after BMP4 treatment (10ng/ml) by western immunoblot with densitometry. (F–N) Expression of BMPR2 related genes as well as abnormally expressed genes identified by RNA-Seq were measured in iPSC-ECs. Bars represent mean±SD from n=3 experiments. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 vs. control or vehicle, #p<0.05 vs. UMC, δp<0.05 vs. FPAH, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparisons test (C–D, F–N), and two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test (E).

Previously, using RNA-Seq analysis, our group reported that several BMPR2 related genes were dysregulated in native PA ECs from the PAH patients, such as decreased COL4A1, COL4A2, EFNA1 and increased HMGA1 (Rhodes et al., 2015). Loss of EFNA1 and/or COL4 inhibits PA EC adhesion, migration (Rhodes et al., 2015), proliferation and tube formation(Ojima et al., 2006; Stewart et al., 2011). Abnormal elevation in HMGA1 contributes to PA endothelial to mesenchymal transition(Hopper et al., 2016).

FPAH iPSC-ECs in Family 1 recapitulate these gene expression changes and correction of the BMPR2 mutation not only increased expression of BMPR2 and its downstream target ID1, but also reversed aberrant expression of the BMPR2 target genes described above, HMGA1, COL4A1, COL4A2 and EFNA1 (Figure 6F–K). Additionally, two genes that were abnormally increased in FPAH iPSC-ECs identified as upregulated by RNA-Seq, ADRA2C and ADRA1D, were reduced upon gene editing (Figure 6L–M). Interestingly, the expression of the anti-apoptosis gene BIRC3 remained unchanged with correction of BMPR2 (Figure 6N), supporting expression of this gene in UMC iPSC-ECs as BMPR2 independent.

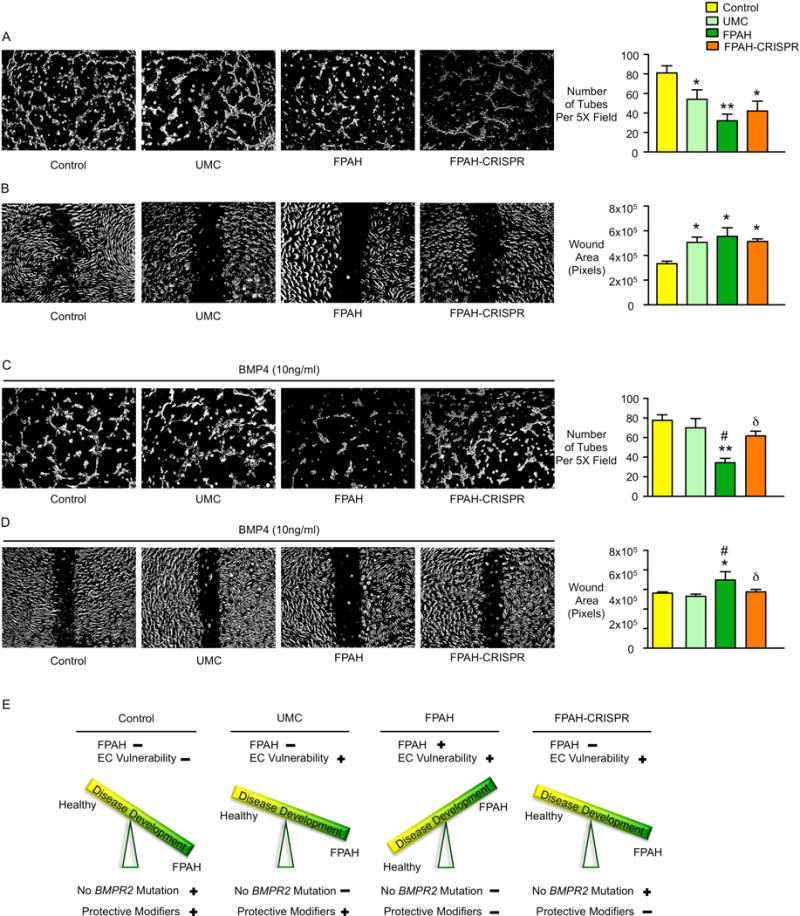

Tube formation and cell migration were still impaired under baseline following editing of the BMPR2 mutation in FPAH iPSC-ECs (Figure 7A–B), as was observed in the UMC. However, like the UMC iPSC-ECs, values for these EC functions in the corrected FPAH iPSC-ECs were improved to control levels with BMP4 stimulation (Figure 7C–D). This suggests that both protective modifiers and a corrected BMPR2 mutation are necessary to fully normalize EC function, as illustrated in Figure 7E.

Figure 7. Angiogenesis and Cell Migration Are Normalized with BMP4 Stimulation After Gene Editing in iPSC-ECs from Family 1 FPAH Patient.

(A) Representative images of tube formation of iPSC-ECs from control, UMC, FPAH and FPAH after gene editing (FPAH-CRISPR) with quantitative analysis, indicating the number of tubes formed six hours after seeding cells on growth factor reduced matrigel. (B) Representative images and quantitative data related to wound closure. A scra12tch was applied to 100% confluent iPSC-ECs and migration of the cells toward the wound was imaged at 0 and 12h. (C, D) BMP4 (10ng/ml) was applied when seeding iPSC-ECs. Angiogenesis analyses (C) and migration assay (D) were performed as described in (A and B). (E) Proposed Model for disease development: (i) Control has normal BMPR2 and protective modifiers thus no FPAH or EC vulnerability; (ii) UMC has BMPR2 mutation, the protective modifiers protect against developing FPAH but may still show vulnerability when the level of BMP ligand is low; (iii) FPAH patient has BMPR2 mutation and lacks protective modifiers, conditions that lead to EC dysfunction associated with FPAH; (iv) After correcting the BMPR2 mutation, EC dysfunction related to the development of FPAH is reversed. However, lack of the protective modifiers still result in EC vulnerability when the level of the BMP ligand is low.

Bars represent Mean±SD from n=3 experiments. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 vs. Control. #p<0.05 vs. UMC, δp<0.05 vs. FPAH, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparisons test.

Discussion

iPSC-based modeling of reduced penetrance of the BMPR2 mutation allowed us to interrogate underlying protective mechanisms that could be considered in developing future PAH therapies, and to elucidate patient-specific protective modifiers of the BMPR2 mutation in UMCs. By integrating a candidate gene approach and high throughput RNA-Seq, we identified a pP38 signaling pathway leading to normal cell adhesion, and an increase in BIRC3 that results in preserved cell survival in UMCs iPSC-ECs. In our study, we identified some patient-specific features in terms of pSMAD1/5-ID signaling, as well as gene expression profiles, indicating that similar preservation of EC function could involve different subsets of modifiers.

To understand the preserved pP38 signaling pathway in UMCs, we screened for several BMPR2 regulators, and found variations in each family, e.g., increased expression of two BMPR2 activators LRP1 (family 1 and 2) and CAV1 (family 2), and decreased expression of two inhibitors FKBP12 (family 1) and GREM1 (family 3). These gene expression changes could be due to gene variants, epigenetic modifiers, non-coding RNAs, upstream transcription factors, or factors affecting mRNA transcript stability. With respect to LRP1, no known polymorphism distinguished the UMC from the PAH patient in family 1, despite the marked increase in mRNA and protein level. Additionally, we measured gene expression and protein levels of BMPR2 co-receptors including ALK1, 2, 3, and 6, and type II receptors ACTRIIA and B, but no differences were observed between UMC and FPAH iPSC-ECs (data not shown). Our findings that there are patient-specific mechanisms that cause similar EC dysfunction related to the development of the disease, underscores the potential of using iPSCs to develop ‘precision’ therapy. It is possible with more families, additional variability will be found in both BMPR2 dependent and independent protective pathways in UMC iPSC-EC.

Given the small cohort size and the stringency of our analysis, it is perhaps not surprising that we identified only 71 genes differentially expressed in control and UMC vs. FPAH iPSC-ECs. While the functions of some of these genes are unknown, others could be directly related to the abnormal phenotypes observed. For example, ADRA1D and ADRA2C were up-regulated in FPAH iPSC-ECs. While they participate in the release of nitric oxide to regulate endothelial function (Couto et al., 2014; Guimaraes and Moura, 2001), alpha-adrenergic activation is a determinant of coronary microvascular resistance in pathophysiological situations associated with endothelial impairment (Jones et al., 1993).

KCNN3 (Potassium Channel, Calcium Activated Intermediate/Small Conductance Subfamily N Alpha, Member 3), that was downregulated in FPAH iPSC-ECs. Reduced KCNN3 in vascular endothelium may be involved in the development of systemic hypertension (Chinnathambi et al., 2013), and selective blockade of endothelial KCNN3 suppressed endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor mediated vasodilation (Eichler et al., 2003). Another potassium channel gene, KCNK3, that results in reduced potassium-channel current, is associated with both familial and idiopathic PAH (Ma et al., 2013).

Correcting the BMPR2 mutation by CRISPR/Cas9 system indicated that the BMPR2 mutation is causal of the abnormal phenotype in the absence of protective modifiers. Interestingly, in gene-edited FPAH iPSC-EC, migration and angiogenesis were only improved when cells were stimulated with exogenous ligand as was observed in UMC iPSC-ECs. Activation by ligand may be necessary to express BMPR2 target genes previously identified as important in migration and angiogenesis such as COL4A2 and EFNA1. It is possible that in the microenvironment of the vessel there is sufficient ligand available to normalize these functions.

Previously, our group carried out a high-throughput screen of known pharmaceuticals approved for other indications using a myoblastoma cell line transfected with a BMPR2 response element in the ID1 gene linked to a luciferase reporter (Spiekerkoetter et al., 2013). The access to blood or skin fibroblasts provides a unique opportunity to determine the efficacy of a personalized drug-screening platform using patient-specific iPSC derived vascular cells and disease-related functional end points. A bioinformatic approach can also be used to find drugs with a gene expression profile that is inverse to that of the FPAH iPSC-ECs, or that copies that of the UMC iPSC-ECs, and to determine whether these agents can activate protective signaling pathways and restore normal vascular cell function.

In conclusion, we identified novel modifiers in unaffected UMC iPSC-ECs that result in a protective pattern of gene expression that is related to preserved endothelial function. The compensatory mechanisms identified in this study, such as elevated levels of BIRC3 and LRP1, could be assessed prospectively to determine whether they are biomarkers that reduce the risk of FPAH in UMC. The results of our studies also suggest the potential of using of iPSC-derived vascular cells to model other vascular diseases where the phenotype may be variable, e.g., Marfan, Williams, or Alagille syndromes.

Experimental Procedures

The Supplemental Information provides extended versions of all experimental procedures.

In Vitro Monolayer Endothelial Differentiation of Human iPSC

We differentiated ECs from iPSCs according to a modification of a protocol previously published by our group (Gu et al., 2015). iPSC-ECs were cultured in EGM2 (iPSC-EC Media, Lonza, Basel, Switzerland). iPSC-ECs used for experiments were between passages 3–5.

Endothelial functional assays

Cell adhesion was assessed as previously described (de Jesus Perez et al., 2012), as was migration, (Liang et al., 2007), caspase activity and angiogenesis (Nickel et al., 2015).

Analysis of Gene Expression

RNA was extracted from 1×105 iPSC-ECs using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Libraries were prepared using the TruSeq Stranded Total RNA Library Prep Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA) and sequenced on 1–2 Illumina HiSeq 2000 lanes to obtain an average of approximately 100–150 million uniquely mapped reads for each sample (Stanford Personalized Medicine Sequencing Core).

The data discussed in this publication have been deposited in NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus (Edgar et al., 2002) and are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE79613 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE79613).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate the editorial and technical assistance of Dr. Michal Bental Roof in preparing both the figures and the text, and the administrative help of Ms. Michelle Fox. This work was supported NIH/NHLBI grant 5U01 HL10739302 (M Rabinovitch, MP Snyder and JC Wu). M Gu was supported by AHA Western States Affiliate postdoctoral fellowship (14POST20460111). M Rabinovitch is supported by the Dunlevie Chair in Pediatric Cardiology at Stanford University.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contributions

MG designed and performed experiments, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. N-YS carried out RNA-Seq analyses. SS helped with cell culture and EC differentiation. DL performed western blot analyses and helped with EC differentiation. VT, IK and MA made the CRISPR/Cas9 corrected cell line. FG prepared libraries for RNA Seq. JL performed ChIP-qPCR. AC helped with MKK and LRP1 over-expression. ST, with the adhesion assay. YM performed droplet digital PCR analysis and helped with reprogramming. ZZ and JC consulted on RNA-Seq data analyses. EA and RH provided fibroblasts from three PAH families. JDG offered substantial intellectual contribution to the project. JCW was responsible for studies related to the reprogramming of fibroblasts to iPSCs and MPS for sequencing studies. MR designed the studies, oversaw the EC functional assays, data acquisition and analysis, and manuscript preparation and editing.

The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

References

- Alastalo TP, Li M, Perez Vde J, Pham D, Sawada H, Wang JK, Koskenvuo M, Wang L, Freeman BA, Chang HY, et al. Disruption of PPARgamma/beta-catenin-mediated regulation of apelin impairs BMP-induced mouse and human pulmonary arterial EC survival. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:3735–3746. doi: 10.1172/JCI43382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin ED, Ma L, LeDuc C, Berman Rosenzweig E, Borczuk A, Phillips JA, 3rd, Palomero T, Sumazin P, Kim HR, Talati MH, et al. Whole exome sequencing to identify a novel gene (caveolin-1) associated with human pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2012;5:336–343. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.111.961888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer EM, Shapiro R, Billiar TR, Bauer PM. High mobility group Box 1 inhibits human pulmonary artery endothelial cell migration via a Toll-like receptor 4- and interferon response factor 3-dependent mechanism(s) J Biol Chem. 2013;288:1365–1373. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.434142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budhiraja R, Tuder RM, Hassoun PM. Endothelial dysfunction in pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 2004;109:159–165. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000102381.57477.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill E, Costello CM, Rowan SC, Harkin S, Howell K, Leonard MO, Southwood M, Cummins EP, Fitzpatrick SF, Taylor CT, et al. Gremlin plays a key role in the pathogenesis of pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 2012;125:920–930. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.038125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaouat A, Coulet F, Favre C, Simonneau G, Weitzenblum E, Soubrier F, Humbert M. Endoglin germline mutation in a patient with hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia and dexfenfluramine associated pulmonary arterial hypertension. Thorax. 2004;59:446–448. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.11890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinnathambi V, Yallampalli C, Sathishkumar K. Prenatal testosterone induces sex-specific dysfunction in endothelium-dependent relaxation pathways in adult male and female rats. Biol Reprod. 2013;89:97. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.113.111542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cogan J, Austin E, Hedges L, Womack B, West J, Loyd J, Hamid R. Role of BMPR2 alternative splicing in heritable pulmonary arterial hypertension penetrance. Circulation. 2012;126:1907–1916. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.106245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couto GK, Davel AP, Brum PC, Rossoni LV. Double disruption of alpha2A- and alpha2C-adrenoceptors induces endothelial dysfunction in mouse small arteries: role of nitric oxide synthase uncoupling. Exp Physiol. 2014;99:1427–1438. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2014.079236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jesus Perez VA, Alastalo TP, Wu JC, Axelrod JD, Cooke JP, Amieva M, Rabinovitch M. Bone morphogenetic protein 2 induces pulmonary angiogenesis via Wnt-beta-catenin and Wnt-RhoA-Rac1 pathways. J Cell Biol. 2009;184:83–99. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200806049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jesus Perez VA, Yuan K, Orcholski ME, Sawada H, Zhao M, Li CG, Tojais NF, Nickel N, Rajagopalan V, Spiekerkoetter E, et al. Loss of adenomatous poliposis coli-alpha3 integrin interaction promotes endothelial apoptosis in mice and humans. Circ Res. 2012;111:1551–1564. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.267849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diebold I, Hennigs JK, Miyagawa K, Li CG, Nickel NP, Kaschwich M, Cao A, Wang L, Reddy S, Chen PI, et al. BMPR2 preserves mitochondrial function and DNA during reoxygenation to promote endothelial cell survival and reverse pulmonary hypertension. Cell Metab. 2015;21:596–608. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake KM, Dunmore BJ, McNelly LN, Morrell NW, Aldred MA. Correction of nonsense BMPR2 and SMAD9 mutations by ataluren in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2013;49:403–409. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0100OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichler I, Wibawa J, Grgic I, Knorr A, Brakemeier S, Pries AR, Hoyer J, Kohler R. Selective blockade of endothelial Ca2+-activated small- and intermediate-conductance K+-channels suppresses EDHF-mediated vasodilation. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;138:594–601. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feletou M. Calcium-activated potassium channels and endothelial dysfunction: therapeutic options? Br J Pharmacol. 2009;156:545–562. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00052.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn C, Zheng S, Yan L, Hedges L, Womack B, Fessel J, Cogan J, Austin E, Loyd J, West J, et al. Connectivity map analysis of nonsense-mediated decay-positive BMPR2-related hereditary pulmonary arterial hypertension provides insights into disease penetrance. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2012;47:20–27. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2011-0251OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Ren Y, Bartulos O, Lee MY, Yue Z, Kim KY, Li W, Amos PJ, Bozkulak EC, Iyer A, et al. Modeling supravalvular aortic stenosis syndrome with human induced pluripotent stem cells. Circulation. 2012;126:1695–1704. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.116996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu M, Mordwinkin NM, Kooreman NG, Lee J, Wu H, Hu S, Churko JM, Diecke S, Burridge PW, He C, et al. Pravastatin reverses obesity-induced dysfunction of induced pluripotent stem cell-derived endothelial cells via a nitric oxide-dependent mechanism. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:806–816. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guimaraes S, Moura D. Vascular adrenoceptors: an update. Pharmacol Rev. 2001;53:319–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez-Uzquiza A, Arechederra M, Bragado P, Aguirre-Ghiso JA, Porras A. p38alpha mediates cell survival in response to oxidative stress via induction of antioxidant genes: effect on the p70S6K pathway. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:2632–2642. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.323709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamid R, Cogan JD, Hedges LK, Austin E, Phillips JA, 3rd, Newman JH, Loyd JE. Penetrance of pulmonary arterial hypertension is modulated by the expression of normal BMPR2 allele. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:649–654. doi: 10.1002/humu.20922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper EG, Alvares SM, Carter WG. Wounding activates p38 map kinase and activation transcription factor 3 in leading keratinocytes. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:3471–3485. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison RE, Flanagan JA, Sankelo M, Abdalla SA, Rowell J, Machado RD, Elliott CG, Robbins IM, Olschewski H, McLaughlin V, et al. Molecular and functional analysis identifies ALK-1 as the predominant cause of pulmonary hypertension related to hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia. J Med Genet. 2003;40:865–871. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.12.865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopper RK, Moonen JR, Diebold I, Cao A, Rhodes CJ, Tojais NF, Hennigs JK, Gu M, Wang L, Rabinovitch M. In Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension, Reduced BMPR2 Promotes Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition via HMGA1 and Its Target Slug. Circulation. 2016;133:1783–1794. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.020617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CJ, DeFily DV, Patterson JL, Chilian WM. Endothelium-dependent relaxation competes with alpha 1- and alpha 2-adrenergic constriction in the canine epicardial coronary microcirculation. Circulation. 1993;87:1264–1274. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.87.4.1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane KB, Machado RD, Pauciulo MW, Thomson JR, Phillips JA, Loyd JE, 3rd, Nichols WC, Trembath RC. Heterozygous germline mutations in BMPR2, encoding a TGF-beta receptor, cause familial primary pulmonary hypertension. Nat Genet. 2000;26:81–84. doi: 10.1038/79226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Languino LR, Gehlsen KR, Wayner E, Carter WG, Engvall E, Ruoslahti E. Endothelial cells use alpha 2 beta 1 integrin as a laminin receptor. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:2455–2462. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.5.2455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leavesley DI, Schwartz MA, Rosenfeld M, Cheresh DA. Integrin beta 1- and beta 3-mediated endothelial cell migration is triggered through distinct signaling mechanisms. J Cell Biol. 1993;121:163–170. doi: 10.1083/jcb.121.1.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang CC, Park AY, Guan JL. In vitro scratch assay: a convenient and inexpensive method for analysis of cell migration in vitro. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:329–333. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S, Lin Y, Nery JR, Urich MA, Breschi A, Davis CA, Dobin A, Zaleski C, Beer MA, Chapman WC, et al. Comparison of the transcriptional landscapes between human and mouse tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:17224–17229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1413624111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, Roman-Campos D, Austin ED, Eyries M, Sampson KS, Soubrier F, Germain M, Tregouet DA, Borczuk A, Rosenzweig EB, et al. A novel channelopathy in pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:351–361. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickel NP, Spiekerkoetter E, Gu M, Li CG, Li H, Kaschwich M, Diebold I, Hennigs JK, Kim KY, Miyagawa K, et al. Elafin Reverses Pulmonary Hypertension via Caveolin-1-Dependent Bone Morphogenetic Protein Signaling. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:1273–1286. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201412-2291OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojima T, Takagi H, Suzuma K, Oh H, Suzuma I, Ohashi H, Watanabe D, Suganami E, Murakami T, Kurimoto M, et al. EphrinA1 inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor-induced intracellular signaling and suppresses retinal neovascularization and blood-retinal barrier breakdown. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:331–339. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips JA, 3rd, Poling JS, Phillips CA, Stanton KC, Austin ED, Cogan JD, Wheeler L, Yu C, Newman JH, Dietz HC, et al. Synergistic heterozygosity for TGFbeta1 SNPs and BMPR2 mutations modulates the age at diagnosis and penetrance of familial pulmonary arterial hypertension. Genet Med. 2008;10:359–365. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e318172dcdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pi X, Schmitt CE, Xie L, Portbury AL, Wu Y, Lockyer P, Dyer LA, Moser M, Bu G, Flynn EJ, 3rd, et al. LRP1-dependent endocytic mechanism governs the signaling output of the bmp system in endothelial cells and in angiogenesis. Circ Res. 2012;111:564–574. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.274597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinovitch M. Molecular pathogenesis of pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:4306–4313. doi: 10.1172/JCI60658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes CJ, Im H, Cao A, Hennigs JK, Wang L, Sa S, Chen PI, Nickel NP, Miyagawa K, Hopper RK, et al. RNA Sequencing Analysis Detection of a Novel Pathway of Endothelial Dysfunction in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192:356–366. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201408-1528OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salicioni AM, Gaultier A, Brownlee C, Cheezum MK, Gonias SL. Low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1 promotes beta1 integrin maturation and transport to the cell surface. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:10005–10012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306625200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekita Y, Wagatsuma H, Nakamura K, Ono R, Kagami M, Wakisaka N, Hino T, Suzuki-Migishima R, Kohda T, Ogura A, et al. Role of retrotransposon-derived imprinted gene, Rtl1, in the feto-maternal interface of mouse placenta. Nat Genet. 2008;40:243–248. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiekerkoetter E, Tian X, Cai J, Hopper RK, Sudheendra D, Li CG, El-Bizri N, Sawada H, Haghighat R, Chan R, et al. FK506 activates BMPR2, rescues endothelial dysfunction, and reverses pulmonary hypertension. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:3600–3613. doi: 10.1172/JCI65592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart JA, Jr, West TA, Lucchesi PA. Nitric oxide-induced collagen IV expression and angiogenesis: FAK or fiction? Focus on “Collagen IV contributes to nitric oxide-induced angiogenesis of lung endothelial cells”. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2011;300:C968–969. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00059.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theodoris CV, Li M, White MP, Liu L, He D, Pollard KS, Bruneau BG, Srivastava D. Human disease modeling reveals integrated transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms of NOTCH1 haploinsufficiency. Cell. 2015;160:1072–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuder RM, Voelkel NF. Angiogenesis and pulmonary hypertension: a unique process in a unique disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2002;4:833–843. doi: 10.1089/152308602760598990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West J, Cogan J, Geraci M, Robinson L, Newman J, Phillips JA, Lane K, Meyrick B, Loyd J. Gene expression in BMPR2 mutation carriers with and without evidence of pulmonary arterial hypertension suggests pathways relevant to disease penetrance. BMC Med Genomics. 2008;1:45. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-1-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu LX, Grimaldo S, Qi JW, Yang GL, Qin TT, Xiao HY, Xiang R, Xiao Z, Li LY, Zhang ZS. Death receptor 3 mediates TNFSF15- and TNFalpha-induced endothelial cell apoptosis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2014;55:109–118. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2014.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.