Abstract

Purpose

Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy is a significant cause of neonatal morbidity and mortality. Erythropoietin (EPO) is emerging as a therapeutic candidate for neuroprotection. Therefore, this study was designed to determine the neuroprotective role of recombinant human EPO (rHuEPO) and the possible mechanisms by which mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway including extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK1/2), JNK, and p38 MAPK is modulated in cultured cortical neuronal cells and astrocytes.

Methods

Primary neuronal cells and astrocytes were prepared from cortices of ICR mouse embryos and divided into the normoxic, hypoxia (H), and hypoxia-pretreated with EPO (H+EPO) groups. The phosphorylation of MAPK pathway was quantified using western blot, and the apoptosis was assessed by caspase-3 measurement and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling assay.

Results

All MAPK pathway signals were activated by hypoxia in the neuronal cells and astrocytes (P<0.05). In the neuronal cells, phosphorylation of ERK-1/-2 and apoptosis were significantly decreased in the H+EPO group at 15 hours after hypoxia (P<0.05). In the astrocytes, phosphorylation of ERK-1/-2, p38 MAPK, and apoptosis was reduced in the H+EPO group at 15 hours after hypoxia (P<0.05).

Conclusion

Pretreatment with rHuEPO exerts neuroprotective effects against hypoxic injury reducing apoptosis by caspase-dependent mechanisms. Pathologic, persistent ERK activation after hypoxic injury may be attenuateed by pretreatment with EPO supporting that EPO may regulate apoptosis by affecting ERK pathways.

Keywords: Erythropoietin, Apoptosis, Mitogen-activated protein kinases, Brain hypoxia-ischemia, Neuroprotection

Introduction

Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) is one of the most important causes of neonatal brain injury. Despite the introduction of hypothermia treatment, HIE still contributes to significant morbidity and mortality in newborn infants1,2). Recently, the progress in understanding the cellular cascades that mediate brain damage after HIE enables to identify the therapeutic target3,4). This advances led to active research for intervention to enhance neuroprotection2).

Among, erythropoietin (EPO) has attracted more attention as a neuroprotective agent because it is already used safely to treat anemia even in newborn infants5,6,7,8,9). EPO is originally a central regulator of erythropoiesis. However, EPO and its receptor (EPOR) also express in nonhematopoietic cells, such as cells of neural origin, and exerts neuroprotective effects5,10,11,12). EPOR is associated with Janus kinase 2 tyrosine kinases with cell-specific downstream transduction pathways including signal transducers and activators of transcription-5, phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase/protein kinase B, nuclear factor kappa B, and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)5,13,14). With EPO binding to EPOR, activation of these downstream pathways have been implicated in the regulation of gene expression leading to neuroprotection5,10,15). Among these pathways, the MAPK signaling pathways are less well characterized, and limited information on the involvement of MAPK in the mechanisms underlying the EPO-induced neuroprotection is available. MAPK pathways are also known to involve in neuronal cell injury including hypoxic-ischemia16,17,18,19,20,21). However, the effect of EPO on MAPK was little known.

Therefore, this study is designed to determine whether EPO has neuroprotective effects against hypoxic injury through cell apoptosis assays. Also, it examined how EPO regulates apoptosis in the MAPK signaling pathway including extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK1/2), p38 MAPK and stress-activated protein kinase/c-Jun N-terminal kinase (SAPK/JNK) in the cultured cortical neuronal cells and astrocytes.

Materials and methods

1. Materials

Recombinant human EPO (rHuEPO) was purchased from CJ Cheiljedang Corporation (Seoul, Korea). Poly-D-lysine was from Sigma (Saint Louis, MO, USA), and 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) was purchased from Duchefa Biochemie (Haarlem, the Netherlands). Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS), Neurobasal medium, B27 supplement, glutamax I, and 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid were obtained from GibcoBRL (Grand Island, NY, USA). Dulbecco's modified eagle's medium (DMEM, high glucose-4,500 mg/L, low glucose-1,000 mg/L), fetal bovine serum (FBS), phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), penicillin-streptomycin, and trypsin-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) were purchased from Hyclone Laboratories (Logan, UT, USA). Albumin bovine was obtained from Affymetrix (Santa Clara, CA, USA). Antibodies against phospho-p44/42MAPK (p-ERK1/2), p44/42MAPK (ERK1/2), phospho-p38 MAPK (p-p38 MAPK), p38 MAPK, phospho-SAPK/JNK (p-SAPK/JNK), SAPK/JNK were all purchased from Cell Signaling Technologies (Beverly, MA, USA). Secondary goat anti-rabbit IgG-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Clarity Western Enhanced Chemiluminescence (ECL) Substrate was purchased from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA, USA).

2. Primary culture of neuronal cells and astrocytes

This study was performed under the approved animal use guidelines of the Catholic University of Daegu, DCIAFCR-150910-6-Y. Primary neuronal cells from cerebral cortices were prepared as previously described22). Embryonic day 16 mice were harvested by cesarean section from anesthetized pregnant ICR mice. Cerebral cortices were isolated and dissociated by trypsin digestion at 37℃ for 1 minute. After washing with HBSS, the cells were triturated with a fire-polished Pasteur pipette. The cell suspension was centrifuged at 1,000 rpm at 25℃ for 5 minutes. The pellet was resuspended in Neurobasal medium supplemented with 2% B 27 and 0.5 mM glutamax, 100-U/mL penicillin, and 100-lg/mL streptomycin. The cell suspension was filtered through a 70-µm strainer. The cells were seeded at a density of 2×106 cells/mm2 in each dish precoated with 50-µg/mL poly-D-lysine. Cultures were maintained in a Neurobasal medium at 37℃ in 95% humidified air and 5% CO2. Three days after plating, the medium was changed. Fifty percent of the medium was changed twice per week.

Primary astrocytes were prepared from postnatal day 1 (P1) or 2 (P2) ICR mouse pups as previously described23). Cerebral cortices were isolated and dissociated by trypsin digestion at 37℃ for 5 minutes. After washing with HBSS, the cells were titrated with a fire-polished Pasteur pipette. The cell suspension was centrifuged at 1,000 rpm at 25℃ for 5 minutes. The pellet was resuspended astrocyte culture medium (DMEM, high glucose+10% FBS+1% penicillin/streptomycin). The cell suspension was filtered through a 70-µm strainer. Cells were seeded in T75 flasks precoated with 50 µg/mL poly-D-lysine. Cultures were maintained in culture medium at 37℃ in 95% humidified air and 5% CO2. After 7 to 8 days, the microglial cells were removed by shaking the T75 flask (at 180 rpm) for 30 minutes in a shaker water bath to obtain purified astrocytes. The supernatant was removed, and fresh culture medium was added to the T75 flask. Then the flask was shaken for 6 hours at 240 rpm to detach the oligodendrocytes from the astrocytes layer. The T75 flask was washed once with PBS and treated with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA. After the astrocytes detached from the T75 flask, they were plated in dishes and incubated at 37℃ in 95% humidified air and 5% CO2. The medium was changed twice per week.

3. MTT assay

In the first set of experiments, cell viabilities were measured by the MTT assay to determine the optimum concentration. Cells were plated in 96-well plates and treat with different concentrations of EPO for 48 hours before a hypoxic insult. The medium was removed and replaced with the 0.5-mg/mL MTT (final concentration). After incubation for 6 hours and 15 hours, at 37℃ in the dark, the MTT solution was removed, and the formazan dye was extracted with 100-µL dimethyl sulfoxide. Absorbance was measured with a microtiter plate enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay reader at 540 nm.

4. Hypoxia experiments

In the second set of experiments, cells were assigned into the normoxic (N, n=4) group, hypoxia (H, n=4) group, and hypoxia-pretreated with EPO (H+EPO, n=4) group. In the N group, the medium was replaced with DMEM with high glucose and then incubated under normoxic conditions (95% humidified air and 5% CO2) at 37℃ for 6 hours or 15 hours. This group was used as a negative control during the process. In the H group, the medium was replaced with DMEM containing low glucose. Afterward, the cells were placed in a hypoxia chamber (Billups-Rothenberg Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) and flushed with 1% O2 (premixed 1% O2, 5% CO2, 94% N2) at the rate of 30 L/min for 4 minutes. In the H+EPO, the medium was replaced with DMEM containing low glucose and then pretreated with 0.1 U/mL (neuronal cells) or 10 U/mL (astrocytes) for 48 hours. The chamber was sealed and incubated at 37℃ for 6 hours or 15 hours.

5. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling assay

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) analysis was performed to measure the degree of cellular apoptosis using an in situ ApoBrdU DNA fragmentation assay kit (BioVision, Mountain View, CA, USA), following the manufacturer's instructions. Cell pellets were harvested, washed twice with PBS, and fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes on ice. After washing with PBS, the cells were incubated with 70% ethanol for a minimum of 30 minutes on ice. The ethanol was carefully aspirated, and the cells were washed with Wash Buffer. Then, the cells were incubated with DNA Labeling Solution for 60 minutes at 37℃. After rinsing with Rinse Buffer, the cells were incubated with the Antibody Solution for 30 minutes at room temperature (RT) in the dark. Thirty minutes after the incubation was complete, Propidium Iodide/RNase A solution was added to the cells, and the cells were incubated for 30 minutes at RT in the dark. Cellular fluorescence was then measured using the Gallios Flow Cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). The 2 dyes in use were propidium iodide (for total cellular DNA) and fluorescein (for apoptotic cells).

6. Caspase-3 activation

The activity of caspase-3 was measured using a colorimetric assay kit (Biovision, San Francisco Bay Area, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cultured cells were concentrated at 300×g for 5 minutes. The pellet was resuspended in a cell lysis buffer and incubated on ice for 10 minutes. The cells were centrifuged for 1 minute in a microcentrifuge (10,000×g). 2X Reaction Buffer was added to the supernatant, and the supernatant proteins were incubated for 1–2 hours at 37℃ with 200 µM DEVD-p-nitroanilide (pNA). The color change was measured using a microtiter plate reader at 405 nm.

7. Western blot analysis

Cell extracts were prepared with radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer (ROCKLAND Immunochemicals, Pottstown, PA, USA) and protein concentrations were determined using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA). Samples were diluted in 5×sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) gel-loading buffer (60 mM Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 25% glycerol, 2% SDS, 14.4 mM 2-mercaptoehanol and 0.1% bromophenol blue) and boiled at 95℃ for 10 minutes. Protein lysates (30 µg) were separated by 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. After transferring to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore, Bed ford, MA, USA) at a constant voltage of 10 V for 27 minutes, membranes were incubated with 5% albumin bovine in Tris-buffered saline plus 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST) at RT for 1 hour. The blots were incubated overnight with primary antibodies against p-ERK1/2, ERK1/2, p-p38 MAPK, p38 MAPK, p-SAPK/JNK, SAPK/JNK. Next, the membranes were washed in TBST and incubated with secondary goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP at 1:2,000 dilution at RT for 1 hour. Detection of a signal was performed with the ECL plus kit. The intensities of the western blot bands were measured by densitometry using Multi Gauge Software (Fuji Photofilm, Tokyo, Japan).

8. Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 22.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA). Examined data were assessed using t tests and analysis of variance. In each test, the data were expressed as the mean±standard deviation with Excel 2007. Statistical significance was defined as when the P value was less than 0.05.

Results

1. Cell viabilities

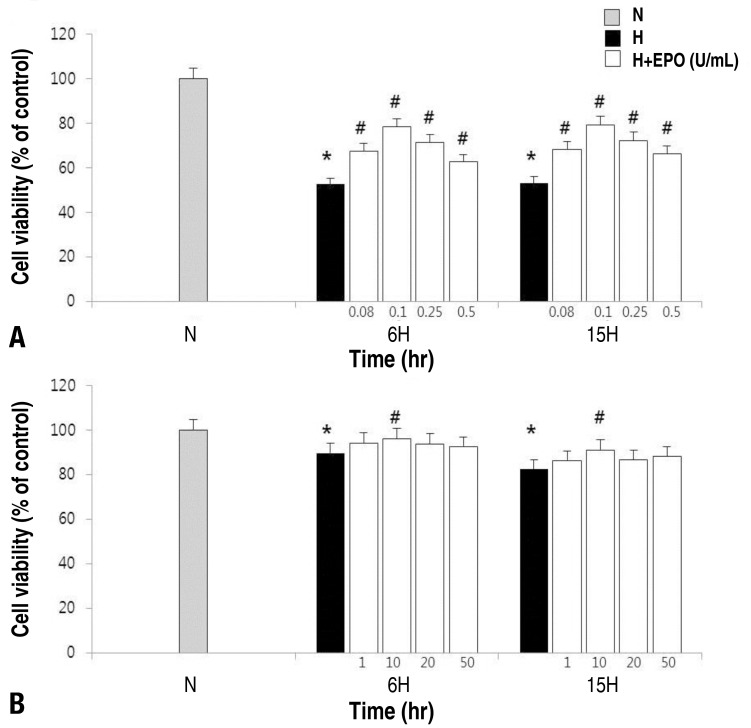

The MTT assay was performed and measure the relative cell viabilities after treatment with rHuEPO at different concentration to determine the most effective concentration of the drug for cell viability (Fig. 1). The results showed that the best cell viabilities were achieved at EPO 0.1 U/mL and 10 U/mL in the neuronal cells and the astrocytes respectively.

Fig. 1. Estimation of cell viability in neuronal cells and astrocytes. Cell viability was measured by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide assay. Dispersed neuronal cell (A) or astrocyte (B) cultures were prepared with different concentrations of erythropoietin (EPO) (0.08, 0.1, 0.25, and 0.5 U/mL in the neuronal cells; 1, 10, 20, and 50 U/mL in the astrocytes) for 48 hours before a hypoxic insult for 6 or 15 hours. The effective dose was 0.1 U/mL in the neuronal cells and 10 U/mL in the astrocytes. H, hypoxic group; H+EPO, hypoxic group pretreated with EPO; N, normoxic group. *P<0.05, statistically significant vs. N group. #P<0.05, statistically significant vs. H group.

2. Detection of apoptosis in the neuronal cells and astrocytes

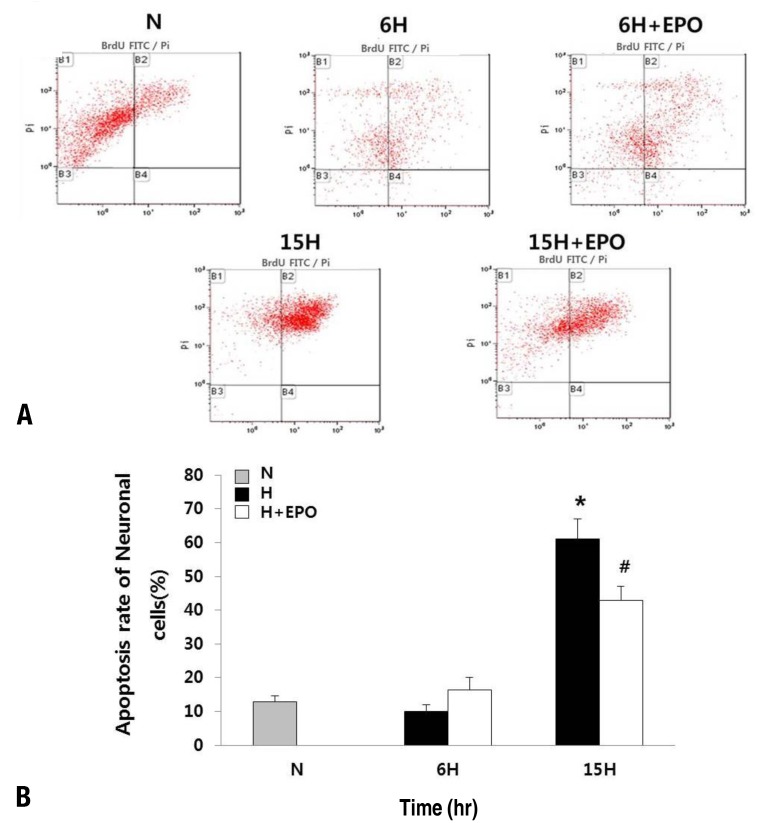

The TUNEL assay was performed by flow cytometry in neuronal cells (Fig. 2) and the astrocytes (Fig. 3) to determine whether EPO reduces apoptotic rates against a hypoxic injury. Hypoxia induces apoptosis in both neuronal cells and astrocytes. This results showed that the astrocytes were more resistant to hypoxic injury compared with the neuronal cells. While the apoptotic rates were 9.91% and 7.12% in the neuronal cells and astrocytes, respectively after 6-hour exposure to hypoxia, as time progresses till 15 hours, the neuronal cells undergo more profound apoptosis (61.07%) compared with the astrocytes (10.54%). After 6-hour exposure to hypoxia, the apoptotic rate was not reduced and rather increased with EPO pretreatment (9.91% in the H and 16.44% in the H+EPO) in the neuronal cells. However, after 15-hour exposure to hypoxia, the apoptotic rate was reduced by about two-third with EPO pretreatment (61.07% in the H and 42.93% in the H+EPO, P<0.05).

Fig. 2. Apoptosis in neuronal cells. (A) Apoptosis assessed by the quantification of BrdU-FITC-labeled DNA breaks using a flow cytometry-based terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling assay in the neuronal cells. Two dyes, propidium iodide (total cellular DNA) and fluorescein (apoptotic cells), were used. (A) Apoptotic cells can be seen in the B2 gate. (B) The percentage of total apoptotic cells is shown in the histogram. N, normoxic group; 6H, hypoxic group that was exposed to hypoxia for 6 hours; 6H+erythropoietin (EPO), hypoxic group pretreated with EPO that was exposed to hypoxia for 6 hours; 15H, hypoxic group that was exposed to hypoxia for 15 hours; 15H+EPO, hypoxic group pretreated with EPO that was exposed to hypoxia for 15 hours. *P<0.05, statistically significant vs. N group. #P<0.05, statistically significant vs. H group.

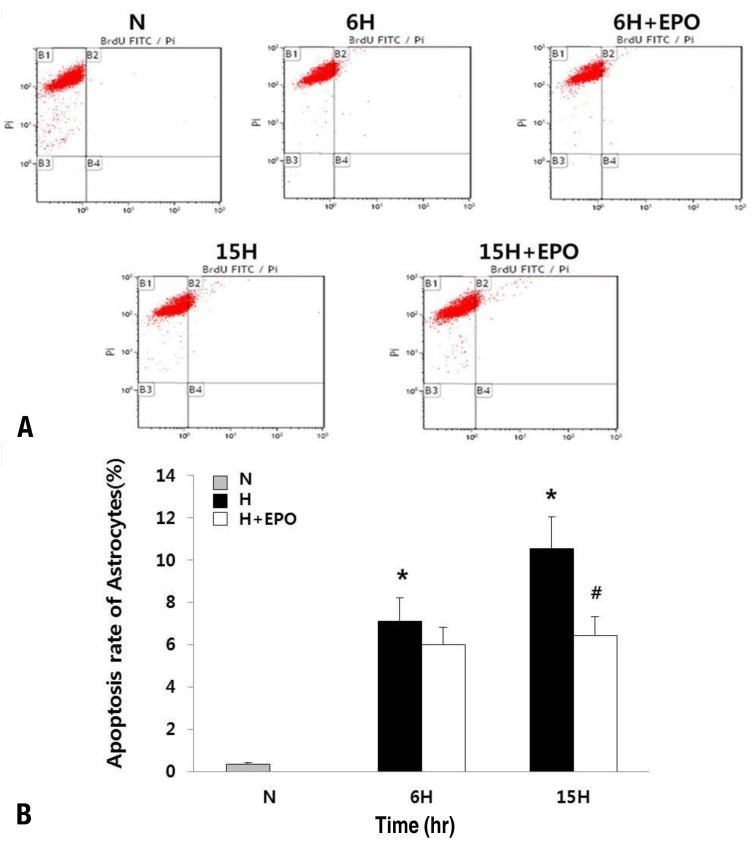

Fig. 3. Apoptosis in the astrocytes. Apoptosis was assessed by the quantification of BrdU-FITC-labeled DNA breaks using a flow cytometry-based terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling assay in the astrocytes. Two dyes, propidium iodide (total cellular DNA) and fluorescein (apoptotic cells), were used. (A) Apoptotic cells can be seen in the B2 gate. (B) The percentage of total apoptotic cells is shown in the histogram. N, normoxic group; 6H, hypoxic group that was exposed to hypoxia for 6 hours; 6H+erythropoietin (EPO), hypoxic group pretreated with EPO that was exposed to hypoxia for 6 hours; 15H, hypoxic group that was exposed to hypoxia for 15 hours; 15H+EPO, hypoxic group pretreated with EPO that was exposed to hypoxia for 15 hours. *P<0.05, statistically significant vs. N group. #P<0.05, statistically significant vs. H group.

In the astrocytes, apoptotic rates were similar with EPO pretreatment after 6 hours after hypoxia exposure (7.12% in the H and 6.01% in the H+EPO). After 15-hour exposure to hypoxia, the apoptotic rate was decreased with EPO pretreatment (10.54% in the H and 6.43% in the H+EPO, P<0.05).

3. Activation of DEVD-specific caspase-3

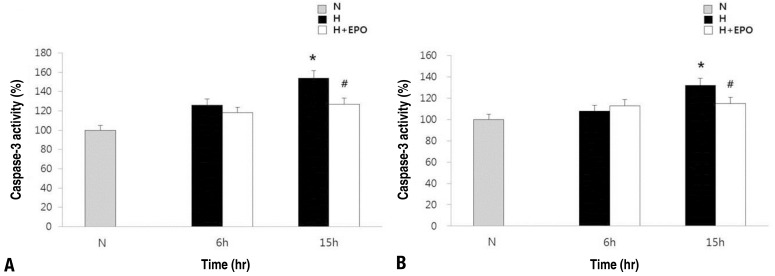

The effects of EPO on neuronal apoptosis induced by hypoxia were evaluated by measuring cleaved caspase-3 activity (Fig. 4). In both neuronal cells and astrocytes, the caspase-3 activity was significantly increased after 15 hours exposure to hypoxia (P<0.05). Pretreatment with EPO attenuates significantly this increase of caspase-3 activity induced by hypoxia in both cell groups (P<0.05).

Fig. 4. Activity of cleaved caspase-3 in the neuronal cells and astrocytes. Caspase-3 was assayed using a caspase-3/CPP32 colorimetric assay kit in the neuronal cells (A) and astrocytes (B). Neuronal cells and astrocytes were plated 24 hours before the induction of apoptosis. The cells were pretreated with EPO for 48 hours before a hypoxic insult at 0.1 U/mL in the neuronal cells, at 10 U/mL in the astrocytes. H, hypoxic group; H+erythropoietin (EPO), hypoxic group pretreated with EPO; N, normoxic group. *P<0.05, statistically significant vs. N group. #P<0.05, statistically significant vs. H group.

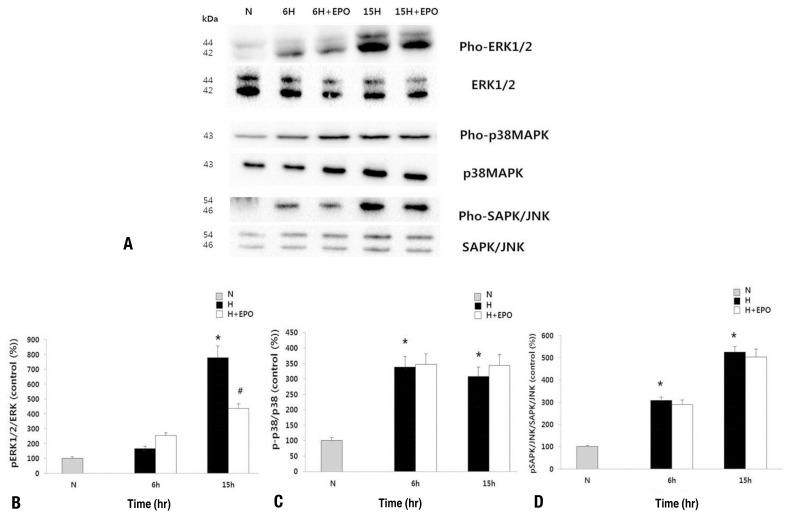

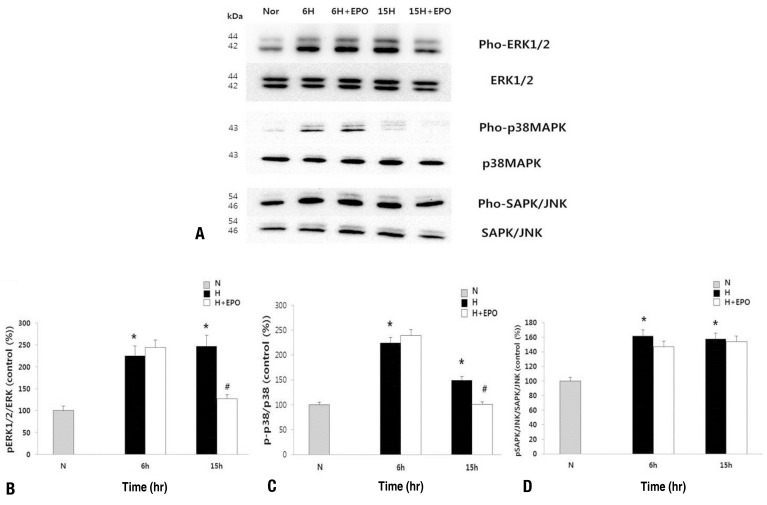

4. Activation of MAPK pathway in the neuronal cells and astrocytes

Western blot was performed at baseline, 6 hours, and 15 hours to examine the expressions of MAPKs and phosphorylated MAPKs to explore the relationship between the effects of EPO on survival and the MAPK pathways in the neuronal cells (Fig. 5) and the astrocytes (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5. (A) Western blot results of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway in the neuronal cells. Expression of antibodies against phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinase (pho-ERK1/2), p38MAPK (pho-p38MAPK), and stress-activated protein kinase/c-Jun N-terminal kinase (SAPK/JNK; pho-SAPK/JNK) was analyzed. (B-D) Expression of ERK1/2, p38 MAPK, SAPK/JNK was used as a loading control. Quantification of Western blot to determine the relative phosphorylation ratio of the MAPK pathway signals in the neuronal cells. The relative phosphorylation ratio of ERK-1/-2 was significantly decreased in H+erythropoietin (EPO) at 15 hours after hypoxia. H, hypoxic group; H+EPO, hypoxic group pretreated with EPO; N, normoxic group. *P<0.05, statistically significant vs. N group. #P<0.05, statistically significant vs. H group.

Fig. 6. (A) Western blot results of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway in the astrocytes. Expression of antibodies against phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinase (pho-ERK1/2), p38MAPK (pho-p38MAPK), and stress-activated protein kinase/c-Jun N-terminal kinase (SAPK/JNK; pho-SAPK/JNK) was analyzed. (B-D) Expression of ERK1/2, p38 MAPK, and SAPK/JNK was used as a loading control. Quantification of western blot results to determine the relative phosphorylation ratio of the MAPK pathway signals in astrocytes. The relative phosphorylation ratio of ERK-1/-2 and p38MAPK was significantly decreased in H+ erythropoietin (EPO) at 15 hours after hypoxia. H, hypoxic group; H+EPO, hypoxic group pretreated with EPO; N, normoxic group. *P<0.05, statistically significant vs. N group. #P<0.05, statistically significant vs. H group.

In the neuronal cells, the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and SAPK/JNK was gradually increased with a peak at 15 hours exposure to hypoxia. The phosphorylation of p38 MAPK has increased persistently both 6- and 15-hour exposure to hypoxia. Pretreatment with EPO did not affect the phosphorylation of p38 MAPK and SAPK/JNK whereas significantly attenuates a decreased of the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 after 15-hour exposure to hypoxia (P<0.05).

In the astrocytes, the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and SAPK/JNK was increased after both 6 hours and 15 hours exposure to hypoxia. The phosphorylation of p38 MAPK was increased after 6-hour exposure to hypoxia and then decreased after 15-hour exposure to hypoxia. Pretreatment with EPO did not affect the phosphorylation of JAPK/JNK whereas significantly attenuates a reduction in the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK after 15-hour exposure to hypoxia (P<0.05).

Discussion

In this study, the effects of EPO on hypoxia-induced neuronal apoptosis and the underlying mechanisms involving MAPK pathways are examined using cultured neuronal cells and astrocytes.

Hypoxia induced apoptosis in both the neuronal cells and astrocytes with caspase-3 activation. Since the caspase-dependent cell damage after neonatal hypoxic injury does not peak until 12–24 hours1), the degree of apoptosis was correlated with caspase-3 activation showing significant neuronal cell loss after 15-hour exposure to hypoxia. Although the astrocytes were more resistant to hypoxia-induced apoptosis, the concentration of rHuEPO for maximal cell viability was 10 fold higher than that of the neuronal cells. As the neuronal cells showed less viability at higher concentration, and the astrocytes did not show benefits at the lower concentration, the cytoprotective dose for the neuronal cells might not be protective for the astrocytes. However, astrocytes also have taken advantage from EPO treatment in oxygen-glucose deprivation model by AQP4 expression and by MAPK pathways24).

Pretreatment with rHuEPO decreased apoptotic rates in both neuronal cells and astrocytes after 15-hour exposure to hypoxia accompanying caspase-3 inactivation indicating that rHuEPO exerts neuroprotective effect via caspase-3 dependent mechanisms. Also, this study showed that rHuEPO attenuated ERK1/2 activation induced by 15-hour hypoxia suggesting the neuroprotective effect of EPO seems to be transduced via the ERK-mediated mechanism.

Since the activation of SAPK/JNK was not affected in both neuronal cells and astrocytes by rHuEPO pretreatment in this study, this result supports the SAPK/JNK pathways themselves may not be involved in the EPO-mediated neuroprotective mechanism. In agreement with this study, Kwon et al.25) also reported that pSAPK/JNK was not altered by EPO treatment in C6 cells.

In the case of p38 MAPK, rHuEPO decreased activation of p38 MAPK in only the astrocyte after exposure of 15-hour hypoxia. These results suggest that the response of each MAPK are cell-specific. The activation of p38 MAPK tended to decrease as time progressed regardless of rHuEPO pretreatment while the role of EPO in p38 MAPK pathway in astrocytes does not seem to be important pathways for EPO-neuroprotection.

ERK is one of the MAPK pathways, and activated by growth factors, mitogen stimuli, glutamate receptor activation and intracellular calcium increases26). The effect of ERK pathway on neuroprotection was diverse in different experimental models. Some reports showed neuroprotection with ERK activation1,25,27) and others showed neuroprotection with ERK inhibition28,29).

The role of ERK activation may be via multiple upstream signaling mechanisms depending on factors such as cell type, culture conditions, and the injurious mechanisms1). Neuronal apoptosis accompanied ERK activation in Perfluorohexane sulfonate induced injury with a persistent increase in intracellular calcium while intracellular calcium-mediated ERK inhibition reduced apoptosis28). Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) showed neuroprotective effect through ERK activation against neonatal HIE brain injury in vivo1,30). They showed BDNF influenced on ERK pathways in only neuronal cells and not in astrocytes and oligodendrocytes. This result supports the cell-type specific ERK activation. In this study, EPO interfered with ERK activation after hypoxic injury in both neuronal cells and astrocytes. Yuan et al.31) reported that the ERK phosphorylation was significantly higher in the HI rats and significantly much higher in the HI+EPO rats. However, they measured ERK activation shortly after HI injury (at 60 minutes and 90 minutes).

Short, transient activation by growth factors under a physiologic condition, ERK activation are associated with neuroprotection while prolonged, persistent activation could induce cell death27). In ischemic tolerance model, neuronal EPOR activated only Akt pathways, not ERK or p38 pathways32) while hypoxic preconditioning involves ERK activation27). These results support the stimulus or injury-dependent ERK activation. Taken together, trophic factors such as BDNF or EPO might initiate transient ERK activation associated with neuroprotective mechanisms. In contrast, prolonged, persistent ERK activation after HI injury might initiate mechanisms of cell death. Indeed, alteration in ERK signaling after brain injury may be distinct from trophic factor stimulation. Due to lack of measurement for the baseline ERK activation after EPO pretreatment, the initial increase in ERK phosphorylation was not determined. However, the study suggests that pretreatment of EPO attenuated the pathologic ERK activation induced by prolonged, persist activation after hypoxic injury and led to improving cell survival.

Since this study did not use the ERK inhibitor, it was not determined whether the ERK inhibition initiated by EPO was direct causative mechanisms for neuroprotection or resultant indirect phenomenon. Kwon et al.25) showed that the inhibitors of pp38 MAPK and pERK abolished the EPO on cytotoxicity of staurosproine. Therefore, the possibility of ERK pathways in regulating apoptosis is still present.

In conclusion, rHuEPO exerts neuroprotective effects against hypoxic injury reducing apoptosis by caspase-dependent mechanisms. Pathologic, persistent ERK activation after hypoxic injury may attenuate by pretreatment EPO supporting that EPO may regulate apoptosis by affecting ERK pathways. This study may contribute to determining the possible mechanisms of the role of each MAPK pathways in the cytoprotective effect of rHuEPO.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the grant of Research Institute of Medical Science, Catholic University of Daegu (2016)

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Han BH, Holtzman DM. BDNF protects the neonatal brain from hypoxic-ischemic injury in vivo via the ERK pathway. J Neurosci. 2000;20:5775–5781. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-15-05775.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnston MV, Fatemi A, Wilson MA, Northington F. Treatment advances in neonatal neuroprotection and neurointensive care. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:372–382. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70016-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Volpe JJ. Perinatal brain injury: from pathogenesis to neuroprotection. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2001;7:56–64. doi: 10.1002/1098-2779(200102)7:1<56::AID-MRDD1008>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnston MV. Excitotoxicity in perinatal brain injury. Brain Pathol. 2005;15:234–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2005.tb00526.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lombardero M, Kovacs K, Scheithauer BW. Erythropoietin: a hormone with multiple functions. Pathobiology. 2011;78:41–53. doi: 10.1159/000322975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rangarajan V, Juul SE. Erythropoietin: emerging role of erythropoietin in neonatal neuroprotection. Pediatr Neurol. 2014;51:481–488. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rabie T, Marti HH. Brain protection by erythropoietin: a manifold task. Physiology (Bethesda) 2008;23:263–274. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00016.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rafiee P, Shi Y, Su J, Pritchard KA, Jr, Tweddell JS, Baker JE. Erythropoietin protects the infant heart against ischemia-reperfusion injury by triggering multiple signaling pathways. Basic Res Cardiol. 2005;100:187–197. doi: 10.1007/s00395-004-0508-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Almaguer-Melian W, Mercerón-Martínez D, Pavón-Fuentes N, Alberti-Amador E, Leon-Martinez R, Ledón N, et al. Erythropoietin promotes neural plasticity and spatial memory recovery in fimbria-fornix-lesioned rats. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2015;29:979–988. doi: 10.1177/1545968315572389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buemi M, Cavallaro E, Floccari F, Sturiale A, Aloisi C, Trimarchi M, et al. Erythropoietin and the brain: from neurodevelopment to neuroprotection. Clin Sci (Lond) 2002;103:275–282. doi: 10.1042/cs1030275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chin K, Yu X, Beleslin-Cokic B, Liu C, Shen K, Mohrenweiser HW, et al. Production and processing of erythropoietin receptor transcripts in brain. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2000;81:29–42. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(00)00157-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernaudin M, Bellail A, Marti HH, Yvon A, Vivien D, Duchatelle I, et al. Neurons and astrocytes express EPO mRNA: oxygen-sensing mechanisms that involve the redox-state of the brain. Glia. 2000;30:271–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma C, Cheng F, Wang X, Zhai C, Yue W, Lian Y, et al. Erythropoietin pathway: a potential target for the treatment of depression. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(5) doi: 10.3390/ijms17050677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alnaeeli M, Wang L, Piknova B, Rogers H, Li X, Noguchi CT. Erythropoietin in brain development and beyond. Anat Res Int. 2012;2012:953264. doi: 10.1155/2012/953264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miljus N, Heibeck S, Jarrar M, Micke M, Ostrowski D, Ehrenreich H, et al. Erythropoietin-mediated protection of insect brain neurons involves JAK and STAT but not PI3K transduction pathways. Neuroscience. 2014;258:218–227. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walker CL, Liu NK, Xu XM. PTEN/PI3K and MAPK signaling in protection and pathology following CNS injuries. Front Biol (Beijing) 2013;8(4) doi: 10.1007/s11515-013-1255-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nito C, Kamada H, Endo H, Narasimhan P, Lee YS, Chan PH. Involvement of mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in expression of the water channel protein aquaporin-4 after ischemia in rat cortical astrocytes. J Neurotrauma. 2012;29:2404–2412. doi: 10.1089/neu.2012.2430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lan A, Liao X, Mo L, Yang C, Yang Z, Wang X, et al. Hydrogen sulfide protects against chemical hypoxia-induced injury by inhibiting ROS-activated ERK1/2 and p38MAPK signaling pathways in PC12 cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25921. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen L, Liu L, Yin J, Luo Y, Huang S. Hydrogen peroxide-induced neuronal apoptosis is associated with inhibition of protein phosphatase 2A and 5, leading to activation of MAPK pathway. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41:1284–1295. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferrer I, Friguls B, Dalfó E, Planas AM. Early modifications in the expression of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK/ERK), stress-activated kinases SAPK/JNK and p38, and their phosphorylated substrates following focal cerebral ischemia. Acta Neuropathol. 2003;105:425–437. doi: 10.1007/s00401-002-0661-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim BC, Kim MK, Cho KH, Kim YS, Lee KY. Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases in hypoxia-induced apoptosis of PC12 cell. J Korean Neurol Assoc. 2001;19:384–392. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lesuisse C, Martin LJ. Long-term culture of mouse cortical neurons as a model for neuronal development, aging, and death. J Neurobiol. 2002;51:9–23. doi: 10.1002/neu.10037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schildge S, Bohrer C, Beck K, Schachtrup C. Isolation and culture of mouse cortical astrocytes. J Vis Exp. 2013;(71):pii: 50079. doi: 10.3791/50079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang Z, Sun X, Huo G, Xie Y, Shi Q, Chen S, et al. Protective effects of erythropoietin on astrocytic swelling after oxygen-glucose deprivation and reoxygenation: mediation through AQP4 expression and MAPK pathway. Neuropharmacology. 2013;67:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kwon MS, Kim MH, Kim SH, Park KD, Yoo SH, Oh IU, et al. Erythropoietin exerts cell protective effect by activating PI3K/Akt and MAPK pathways in C6 Cells. Neurol Res. 2014;36:215–223. doi: 10.1179/1743132813Y.0000000284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomas GM, Huganir RL. MAPK cascade signalling and synaptic plasticity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:173–183. doi: 10.1038/nrn1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones NM, Bergeron M. Hypoxia-induced ischemic tolerance in neonatal rat brain involves enhanced ERK1/2 signaling. J Neurochem. 2004;89:157–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee E, Choi SY, Yang JH, Lee YJ. Preventive effects of imperatorin on perfluorohexanesulfonate-induced neuronal apoptosis via inhibition of intracellular calcium-mediated ERK pathway. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2016;20:399–406. doi: 10.4196/kjpp.2016.20.4.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Subramaniam S, Zirrgiebel U, von Bohlen Und Halbach O, Strelau J, Laliberté C, Kaplan DR, et al. ERK activation promotes neuronal degeneration predominantly through plasma membrane damage and independently of caspase-3. J Cell Biol. 2004;165:357–369. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200403028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kilic E, Kilic U, Soliz J, Bassetti CL, Gassmann M, Hermann DM. Brain-derived erythropoietin protects from focal cerebral ischemia by dual activation of ERK-1/-2 and Akt pathways. FASEB J. 2005;19:2026–2028. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-3941fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yuan QC, Jiang L, Zhu LH, Yu DF. Impacts of erythropoietin on vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 by the extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling pathway in a neonatal rat model of periventricular white matter damage. Zhongguo Yi Xue Ke Xue Yuan Xue Bao. 2016;38:217–221. doi: 10.3881/j.issn.1000-503X.2016.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ruscher K, Freyer D, Karsch M, Isaev N, Megow D, Sawitzki B, et al. Erythropoietin is a paracrine mediator of ischemic tolerance in the brain: evidence from an in vitro model. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10291–10301. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-23-10291.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]