Abstract

Lack of awareness, the stigma of carrying a genetic mutation, and economic factors are barriers to acceptance of BRCA genetic testing or appropriate risk management. We aimed to investigate the influence of Angelina Jolie's announcement of her medical experience and also health insurance reimbursement for BRCA gene testing on practice patterns for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC). A survey regarding changes in practice patterns for HBOC before and after the announcement was conducted online. The rate of BRCA gene testing was obtained from the National Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service database. From May to August 2016, 70 physicians responded to the survey. Genetic testing recommendations and prophylactic management were increased after the announcement. Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy and contralateral prophylactic mastectomy was significantly increased in BRCA carriers with breast cancer. The BRCA testing rate increased annually. Health insurance and a celebrity announcement were associated with increased genetic testing.

Keywords: Breast neoplasms, Genetic testing, Insurance coverage, Practice patterns, Prophylactic mastectomy

Genetic susceptibility is associated with an increased risk of breast cancer. The most common causative gene of hereditary breast cancer is BRCA1/2, accounting for almost one quarter of familial breast cancer. In a study of a Korean population, the prevalence of the BRCA mutation was reported to be 20% in breast cancer patients with a family history of breast cancer, consistent with Western populations. The estimated cumulative risk of breast and ovarian cancer with BRCA mutations have been calculated, respectively, as 72% and 25% for BRCA1 and 66% and 11% for BRCA2 [1]. BRCA gene testing is supported by National Health Insurance in Korea if the patient has a risk of hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC). If the patient has been proven to have a BRCA mutation, a risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy (RRSO) and genetic testing of family members are also supported. There have been several events that drew public attention to HBOC in Korea. First, the Korean Hereditary Breast Cancer Study (KOHBRA study) was started in 2007 [2], with support from the Ministry of Health, and Welfare of Korea and the Korean Breast Cancer Society. Second, the strategy of BRCA testing coverage by the National Health Insurance system was promoted in May 2012. Subsequently, Angelina Jolie, an actress from the United States, publicized her story of having a BRCA1 mutation and her experience of undergoing bilateral risk-reducing mastectomy in May 2013. After her announcement, public awareness of breast cancer susceptibility genes and familial cancer increased, the so-called “Angelina effect” [3,4]. We conducted a survey to investigate the influence of the “Angelina effect” on practice patterns for HBOC in Korea and also reviewed national data of BRCA gene test prescription. Ethical approval was obtained from institutional review board (number: 2016-04-007). Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, USA). A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The questionnaire consisted of 38 questions asking participants to recall medical services performed before and after the announcement. A total of 70 participants replied to the questionnaire, most of whom were surgical oncologists. Recommendations of genetic testing were significantly increased in circumstances that might be related to HBOC. Regarding carrier management, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or surveillance and tamoxifen for chemoprevention were more frequently recommended (p<0.001). Recommendations of risk-reducing surgeries were also significantly increased. Genetic testing of family members was more commonly recommended when a pathogenic mutation was found (81.4% before the announcement and 98.6% after the announcement, p<0.001). Most of the respondents did not prescribe genetic testing for other genes, but some of the respondents replied that they test for PTEN (2.9%) and TP53 (1.4%), and panel testing was added by 8.6% of physicians.

Another survey regarding institutional records of BRCA mutation carriers was available from 28 medical centers. In unaffected carriers, bilateral risk-reducing mastectomy (RRM) was performed in one individual in 2012 before the announcement and another one was performed during 2015 (Table 1). In affected carriers, contralateral prophylactic mastectomy increased from four cases per year in 2012 to 20 cases per year in 2015. A significant increase of RRSOs was also seen (16 in 2012 and 75 in 2015, p=0.002).

Table 1. Acceptance of risk-reducing surgery in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers.

| Before announcement (2012) |

After announcement (2015) |

p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bilateral risk-reducing mastectomy | 1 | 1 | 1.000 |

| Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy | 4 | 20 | 0.017 |

| Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy | |||

| Unaffected carrier | 1 | 2 | 0.317 |

| Affected carrier | 16 | 75 | 0.002 |

*p-value by Wilcoxon's signed rank test.

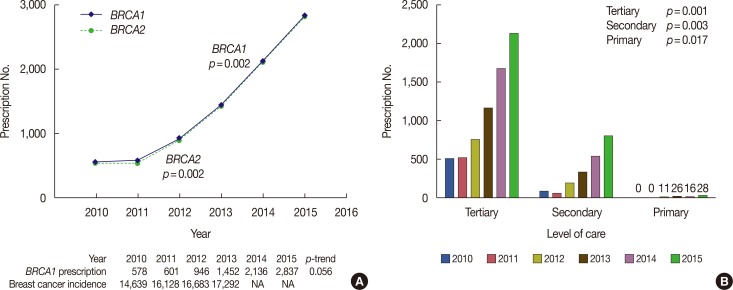

The number of patients who received BRCA gene testing from January 2010 to December 2015 was reviewed using the National Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service database (Figure 1A). The annual breast cancer incidence from the Cancer Registry was used as reference, available from 2010 to 2013 [5]. Monthly BRCA gene testing prescription was divided into three phases: phase 1 from January 2010 to May 2012 (insurance coverage), phase 2 from June 2012 to May 2013 (Angelina Jolie's announcement), and phase 3 from June 2013 to December 2015. The number of patients undergoing BRCA1 and BRCA2 testing significantly increased through time. Monthly aggregates of the number of genetic tests was increased in phase 2 (after health insurance coverage) and phase 3 (Angelina Jolie's announcement) compared with reference phase 1 (p<0.001 for both phase 2 and phase 3). Phase 3 also showed a significant change compared with phases 1 and 2 (βyear=33.6 [3.4], p<0.001 and βevent=34.9 [11.9], p=0.005).

Figure 1. Annual trend of BRCA gene testing prescription. (A) Annual patient numbers who received BRCA1 and BRCA2 genetic testing. (B) Annual BRCA1 testing numbers by level of care from 2010 to 2015. p-value represents for trend test.

NA=not available.

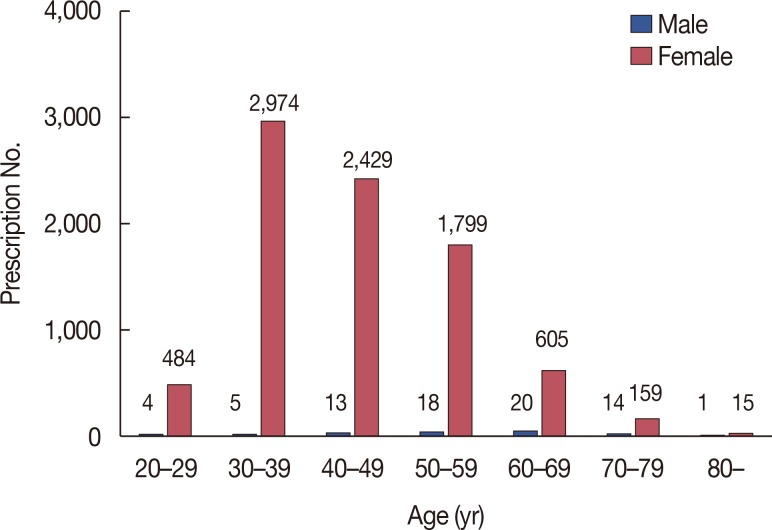

The increasing rate of BRCA1/2 testing is shown in Table 2, which also shows a higher rate in major cities than in provincial areas (p=0.002). The number of tests increased yearly regardless of the level of care (Figure 1B). In 2012, BRCA1 genetic testing started to be performed by primary physicians. The cumulative numbers of BRCA1/2 tests according to age group showed a higher incidence in age groups 30 to 39 and 40 to 49 (Figure 2).

Table 2. BRCA1 testing prescription rate following patient factors and annual breast cancer incidence rate (2010–2013).

| β | SE | p-value* | RR | 95% CI | p-value† | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Model 1‡ | |||||||

| BRCA1 testing | 468.743 | 63.327 | 0.002 | 1.341 | 1.163 | 1.546 | 0.056 |

| Model 2§ | |||||||

| BRCA1 testing | 117.321 | 37.11 | 0.005 | 1.342 | 1.247 | 1.444 | <0.001 |

| Sex | <0.001 | 0.019 | |||||

| Male | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Female | 701.083 | 126.753 | 0.361 | 0.172 | 0.757 | ||

| Patients | 0.024 | <0.001 | |||||

| Inpatient | Reference | 0.35 | 0.293 | 0.418 | |||

| Outpatient | –310.250 | 126.753 | Reference | ||||

| Model 3§ | |||||||

| BRCA1 testing | 234.657 | 51.137 | 0.001 | - | - | - | - |

| Area | 0.002 | ||||||

| Urban cities | Reference | - | - | - | - | ||

| Provincial area | –751.333 | 174.668 | - | - | - | - | |

SE=standard error; RR=relative risk; CI=confidence interval.

*p-value by Linear regression analysis without adjustment by annual breast cancer incidence; †p-value by Poisson regression analysis with adjustment by annual breast cancer incidence; ‡model observing serial change; §model observing serial change adjusted by multiple factors.

Figure 2. Number of BRCA1 prescription by age group from 2010 to 2015. Age of 30' in women showed the highest testing rate.

During the period of 2010 to 2013 when the annual breast cancer incidence was available for evaluation, prescription of BRCA1 testing increased annually, but the increase was statistically nonsignificant (relative risk, 1.341; 95% confidence interval, 1.163–1.546; p=0.056). After adjusting for the annual breast cancer incidence rate, male patients more frequently chose genetic testing than female patients, under the assumption that all patients receiving BRCA genetic testing were breast cancer patients (Table 2).

This study showed that there were positive changes in the practice patterns for HBOC, such as more genetic testing recommendations and more accepting attitudes toward cancer surveillance and chemoprevention, after Angelina Jolie's announcement. Although genetic testing for BRCA mutations increased annually, it was statistically nonsignificant after correction for an increasing incidence of breast cancer, with a hypothesis that limited information after 2013 might have affected the evaluation. The prevalence of BRCA2 mutation in Korean male breast cancer was 8.3% in the KOHBRA study [2] compared to other studies reporting prevalence ranging from 3% to 33% [6,7]. After adjusting for annual incidence, a higher proportion of male patients than female patients received genetic testing in this study, suggesting an increased risk perception in male patients.

A celebrity's medical history can be conveyed to the public and thus increase awareness of a disease [8]. After the New York Times announcement about Angelina Jolie's experience, the impact from the article brought global understanding of how a familial history of cancer can be related to personal cancer risk. The “Angelina effect” was seen in increased referrals to genetics services [9,10,11]. Risk-reducing surgeries were increased after her disclosure [12], and a report of a single institution revealed that 74% of the patients who underwent RRM in 2013 had received their test results more than 18 months previously, indicating that their decision to undergo surgery had been influenced by the announcement [13]. The results of the present study were consistent with those of the other studies, although there was a limitation that the number of risk-reducing surgeries was determined simply by comparing yearly records between 2012 and 2015.

We previously reported the effect of the KOHBRA study on HBOC management in 2009 [14]. Before the study (2007), 8% of physicians recommended MRI compared with 10% after the study (2009), whereas 60% of the physicians (2015) in the present study recommended MRI. There was no significant difference in the number of RRMs performed. On the other hand, RRSO was performed in 27 cases in 25 institutions in 2009 and in 75 cases in 27 institutions (the participating institutions were not the same) in 2015. Some physicians responding to our survey mentioned that patients are reluctant to undergo contralateral prophylactic mastectomy or RRM, and therefore the decision tends to be made based on the patient's wishes rather than their actual risks.

Genetic testing recommendations by physicians and the numbers of BRCA tests have been increasing not only because of Angelina Jolie's announcement changing the public's perception but also because of the insurance coverage. RRM in unaffected carriers has not yet been widely performed. Information from further investigation of cancer risk in unaffected mutation carriers in a Korean population would help future decision-making.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank all of the respondents who contributed to this study, Dongwon Kim, Hyunnam Baek, Hee Joon Kang, Dong-seok Lee, Young Jun Jeong, Myungchul Chang, Ki-Tae Hwnag, Ku Sang Kim, Jeeyeon Lee, Jung-Hyun Yang, Hyun-Ah Kim, Choi Sun Ho, Sung Soo Oh, Min Hee Hur, Tae Hyun Kim, Seokwon Lee, Young Jin Suh, Jae Il Kim, Hyun Jung Choi, Hyun Jo Youn, Im Ryung Kim, Namsun Paik, Dae Sung Yoon, Wonshik Han, Min Sun Young, Taewoo Kang, Lee Su Kim, Se Hyun Paek, Seung Pil Jung, Soon Young Tae, Min Kyoon Kim, Cholhee Yun, Jeong Eon Lee, Hye Yoon Lee, Joonwon Min, Jungsun Lee, SeungSang Ko, Min-Young Choi, Hyegyong Kim, Jung Yeon Lee, Byung Ho Son, Chan Seok Yoon, Eun-Jung Jung, Eun-Kyu Kim, Jeoungwon Bae, Sang Ah Han, Eun A Choi, Min Ho Park, Kim Jihyun, So-Youn Jung, Byung Ju Chae, Jee man You, Eun Sook Lee, Hae Sung Kim, Jae Hyuck Choi, Seock-Ah Im, Jung Eun Choi, Sung Yong Kim, Ji Young You, Geumhee Gwak, Hyung Seok Park, Woo Young Sun, Seeyoun Lee, and Young Ran Hong. The authors also wish to thank Eunhwa Park, Jinho Kwak, Eunjin Choi, Myung-chul Chang, Yong-bum Yoo, Cheol Wan Lim, Sung Mo Huh, Sumin Chae, Woo Chul Noh, Min-Ki Seong, Sung Hoo Jung, Sang Yull Kang, Jin Hyang Jung, Ho Yong Park, Yoon Jung Kang, Jaehag Jung, Min Sung Chung, Tae In Yoon, Jae Eun Lee, Ho Hur, Bu Yoen Jung, Eun-Shin Lee, Sung Gwe Ahn, Hak Woo Lee, Jong Won Lim, Tae-Kyung Yoo, Il-Yong Chung, Minhye Ahn, and Yoon Soon Mun for institutional statistics for BRCA mutation carriers.

Footnotes

This work was funded by the Soonchunhyang University Research Fund and from the National R&D Program for Cancer Control, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (number: 1020350).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Kang E, Kim SW. The Korean hereditary breast cancer study: review and future perspectives. J Breast Cancer. 2013;16:245–253. doi: 10.4048/jbc.2013.16.3.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Han SA, Park SK, Ahn SH, Lee MH, Noh DY, Kim LS, et al. The Korean Hereditary Breast Cancer (KOHBRA) study: protocols and interim report. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2011;23:434–441. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hawkes N. “Angelina effect” led to more appropriate breast cancer referrals, research shows. BMJ. 2014;349:g5755. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g5755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.James PA, Mitchell G, Bogwitz M, Lindeman GJ. The Angelina Jolie effect. Med J Aust. 2013;199:646. doi: 10.5694/mja13.11218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Cancer Information Center. Annual report of cancer statistics in Korea in 2013. [Accessed June 7th, 2017]. http://www.cancer.go.kr/

- 6.Couch FJ, Farid LM, DeShano ML, Tavtigian SV, Calzone K, Campeau L, et al. BRCA2 germline mutations in male breast cancer cases and breast cancer families. Nat Genet. 1996;13:123–125. doi: 10.1038/ng0596-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ottini L, Masala G, D'Amico C, Mancini B, Saieva C, Aceto G, et al. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation status and tumor characteristics in male breast cancer: a population-based study in Italy. Cancer Res. 2003;63:342–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kosenko KA, Binder AR, Hurley R. Celebrity influence and identification: a test of the Angelina effect. J Health Commun. 2016;21:318–326. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2015.1064498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freedman R, Mountain H, Karina D, Schofield L. A retrospective exploration of the impact of the ‘Angelina Jolie Effect’ on the single State-Wide Familial Cancer Program in Perth, Western Australia. J Genet Couns. 2017;26:52–62. doi: 10.1007/s10897-016-9982-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evans DG, Barwell J, Eccles DM, Collins A, Izatt L, Jacobs C, et al. The Angelina Jolie effect: how high celebrity profile can have a major impact on provision of cancer related services. Breast Cancer Res. 2014;16:442. doi: 10.1186/s13058-014-0442-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raphael J, Verma S, Hewitt P, Eisen A. The impact of Angelina Jolie (AJ)'s story on genetic referral and testing at an Academic Cancer Centre in Canada. J Genet Couns. 2016;25:1309–1316. doi: 10.1007/s10897-016-9973-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malcolm CM, Javed MU, Nguyen D. Has the Angelina Jolie effect led to an increase in risk reducing mastectomy and breast reconstruction in Wales: a retrospective, single centre cohort study. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2016;69:288–289. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2015.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evans DG, Wisely J, Clancy T, Lalloo F, Wilson M, Johnson R, et al. Longer term effects of the Angelina Jolie effect: increased risk-reducing mastectomy rates in BRCA carriers and other high-risk women. Breast Cancer Res. 2015;17:143. doi: 10.1186/s13058-015-0650-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kang E, Ahn SH, Noh WC, Noh DY, Jung Y, Kim LS, et al. The change of practice patterns of the hereditary breast cancer management in Korea after the Korean Hereditary Breast Cancer Study. J Breast Cancer. 2010;13:418–430. [Google Scholar]