Abstract

Background

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death. Little is known about whether prediagnostic nutritional factors may affect survival. We examined the associations of prediagnostic calcium intake from foods and/or supplements with lung cancer survival.

Methods

The present analysis included 23,882 incident, primary lung cancer patients from 12 prospective cohort studies. Dietary calcium intake was assessed using food-frequency questionnaires at baseline in each cohort and standardized to caloric intake of 2000 kcal/d for women and 2500 kcal/d for men. Stratified, multivariable-adjusted Cox regression was applied to compute hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results

The 5-year survival rates were 56%, 21%, and 5.7% for localized, regional, and distant stage lung cancer. Low prediagnostic dietary calcium intake (<500–600 mg/d, less than half of the recommendation), was associated with a small increase in risk of death compared with recommended calcium intakes (800–1200 mg/d); HR (95% CI) was 1.07 (1.01, 1.13) after adjusting for age, stage, histology, grade, smoking status, pack-years, and other potential prognostic factors. The association between low calcium intake and higher lung cancer mortality was evident primarily among localized/regional stage patients, with HR (95% CI) of 1.15 (1.04, 1.27). No association was found for supplemental calcium with survival in the multivariable-adjusted model.

Conclusions

This large pooled analysis is the first, to our knowledge, to indicate that low prediagnostic dietary calcium intake may be associated with poorer survival among early-stage lung cancer patients.

Impact

This multinational prospective study linked low calcium intake to lung cancer prognosis.

Keywords: Lung cancer survival, calcium intake, prediagnostic nutritional factors, prospective cohort study, pooled analyses

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death worldwide, accounting for 1.6 million deaths (20% of all cancer deaths) annually (1). Most lung cancer patients are diagnosed at advanced stages; 5-year survival rate is only ~18% in the United States (US) and is even lower in other countries (2–4). While its prognosis largely depends on stage, histologic type, treatment options, and patient demographics and comorbidity status (2,5,6), emerging evidence suggests that prediagnostic nutrition and lifestyle factors may also influence lung cancer survival (7–9).

Both experimental and epidemiological studies have suggested potential roles of calcium in cancer development and progression (10). Besides its well-known effects on bone health, calcium intake and calcium homeostasis can affect cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis, parathyroid hormone (PTH) and PTH-related peptide, vitamin D metabolism and signaling, angiogenesis, and immune response (11,12). Compromised bone health and impaired calcium homeostasis due to a long-term calcium insufficiency may promote tumor progression and metastasis. Cohort studies and meta-analyses have linked adequate calcium intake with decreased overall cancer risk and risks of colorectal, breast, and prostate cancers (13–19). Evidence, although limited, has also linked calcium intake with lung cancer risk (20–22). However, few cohort studies have examined the association of prediagnostic calcium intake with cancer survival, and none explicitly with lung cancer survival (23,24).

We investigated prediagnostic calcium intake from foods and supplements in relation to lung cancer survival using data from a large pooling project, the Calcium and Lung Cancer Pooling Project. Individual-level data of ~1.7 million participants from 12 prospective cohort studies in the US, Europe, and Asia were pooled, resulting in 23,882 incident, primary lung cancer cases. We examined the association among all cases combined and separately by major lung cancer prognostic factors, including age, stage, and histology. We focused our analyses more on the survival of localized and regional stage patients because it is unlikely that the prognosis of distant stage lung cancer would be significantly influenced by prediagnostic nutritional factors, given its high fatality rate and short survival time.

Materials and Methods

Study Populations

Participating studies included eight US cohorts: the National Institutes of Health-AARP study (NIH-AARP) (25), Health Professionals’ Follow-Up Study (HPFS) (26), Nurses’ Health Study I (NHS) (27), Iowa Women’s Health Study (IWHS) (28), Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial (PLCO) (29), Southern Community Cohort Study (SCCS) (30), Vitamins and Lifestyle Cohort Study (VITAL) (31), and Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study (WHI) (32); one European cohort: the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition Cohort (EPIC) (33); and three Asian cohorts: the Japan Public Health Center-based Prospective Study cohort I and II (JPHC) (34), Shanghai Men’s Health Study (SMHS) (35), and Shanghai Women’s Health Study (SWHS) (36). Each study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at local institutions; the pooling project was approved by the Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board.

Assessment of Dietary and Supplemental Calcium Intake

Usual dietary intakes were assessed at baseline in each cohort using a self- or interviewer-administered food-frequency questionnaire (FFQ) as described in previous publications (37–48). The FFQs usually inquired about habitual consumption of common food items over the past 12 months and were validated against 24-hour dietary recalls, 7-day food records, or dietary biomarkers. Daily food intakes were estimated based on the frequency and amount of consumption and were linked to country/region-specific food composition tables to calculate intakes of energy (kcal/d), calcium (mg/d), and other nutrients. In the current study, dietary intakes were adjusted for total energy intake using the nutrient density method (49) and standardized to intakes per 2000 kcal for women and per 2500 kcal for men. Intake of supplemental calcium was assessed in eight US cohorts. Participants were asked whether in the past year they generally took supplements (multivitamins and/or single calcium supplements); and if yes, how often (from less than once per week to every day) and how much they usually took (from <200 mg/d to >1000 mg/d for calcium). Most cohorts estimated supplemental calcium intakes from both calcium supplements and multivitamins, except that the SCCS asked only about the use of calcium supplements.

Assessment of Lung Cancer Incidence and Survival

Our primary outcome is overall survival time, calculated by counting from the date of lung cancer diagnosis to the date of death or end of follow-up, whichever came first. Incident cancer cases and the vital status of cancer patients were identified in each cohort through linkages with national/regional cancer registries and death registries, follow-up interviews, review of medical records and/or death certificates, or these methods combined. Cancers of the bronchus and lung were ascertained by the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes: 162 (ICD-9) or C34 (ICD-10). Year of diagnosis and whether lung cancer was the underlying cause of death was acquired from the cohorts. Clinical information was obtained when available, including stage, histologic type, and grade. We harmonized tumor information across studies as follows: stage—localized, regional, distant, and unknown; histologic type—adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, other non-small cell lung cancer, small cell lung cancer, and other; and grade—well-, moderately-, and poorly-differentiated, undifferentiated, and unknown.

Assessment of Non-dietary Covariates

Baseline information on sociodemographics, lifestyles, medical history, and anthropometrics was obtained from each cohort and harmonized for the current study, including age at baseline and at diagnosis (years, integer), sex (male or female), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, Black, Asian, or other), educational attainment (≤ high school, vocational school or some college, college or graduate school), smoking status (never, former, or current use of cigarettes, cigars, or pipe), pack-years of cigarette smoking (continuous), alcohol drinking status (none, moderate, or heavy [>14 g/d for women and >28 g/d for men]), physical activity level (low, middle, or high [cutoffs: zero leisure-time physical activity and median of non-zero leisure-time physical activity assessed by metabolic equivalents or hours, or tertile of total physical activity metabolic equivalents]), history of diabetes (yes or no), obesity status (body mass index [BMI] <18.5, 18.5–24.99, 25.0–29.99, or ≥30 kg/m2), and in women, postmenopausal status (yes or no) and use of hormone therapy (never or ever).

The proportion of missing values was generally <10% in each cohort for these covariates. If the proportion of missing values was <3%, we assigned the median non-missing value for continuous variables (e.g., BMI) and the most frequent category for categorical variables (e.g., education). If the proportion of missing variables was ≥3%, we used a multivariate imputation to estimate missing value based on other covariates, calcium intake, energy intake, and lung cancer and death outcomes (SAS PROC MI procedure). Missing data imputation was processed for each cohort separately. Of note, in the JPHC, Cohort I did not have data on physical activity metabolic equivalents and Cohort II did not collect information on education level; we imputed these two variables using the above described method in JPHC Cohort I and II data combined.

Analytic population

We excluded participants from the current study if they had 1) a history of any cancer except non-melanoma skin cancer prior to lung cancer, 2) missing diagnosis or survival time information, 3) missing calcium intakes or smoking status information, or 4) implausible total energy intake (beyond three standard deviations of the cohort- and sex-specific log-transformed mean energy intake or beyond the cohort pre-determined range). A total of 24,440 incident primary lung cancer cases among 1,679,842 participants of the pooling project were considered eligible. We further excluded 11 cases with cancer in situ and 547 cases with data missing on both stage and histology, leaving 23,882 incident lung cancer cases in our analyses.

Statistical Analysis

Usual dietary calcium intakes were compared among lung cancer patients with different baseline characteristics and tumor features using a general linear model (adjusted for age at baseline, sex, and total energy intake). Corresponding 5-year survival rates were estimated by the life-table method and P for differences was evaluated via the log-rank test with Bonferroni correction. The Cox proportional hazard model was used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), stratified by cohort, year of lung cancer diagnosis (5-year intervals from earlier than 1990 to later than 2010), and time interval between dietary assessment and lung cancer diagnosis (<4, 4–7, 7–10, and >10 years, according to the quartile distribution). Potential confounders associated with calcium intake and/or lung cancer survival were adjusted for, including age at diagnosis, sex, race/ethnicity, education, smoking status, pack-years of cigarette smoking, total energy intake, alcohol consumption, physical activity, history of diabetes, obesity status, use of hormone therapy in women, and the stage, histologic type, and grade of lung cancer. Considering the interplay of calcium, magnesium, vitamin D, and phosphorus, we further adjusted for, when data were available, dietary intakes of magnesium (in all cohorts), vitamin D (in 9 cohorts), and phosphorus (in all cohorts), individually or together, with or without interaction terms with calcium. However, the associations of dietary calcium with lung cancer survival were basically unchanged, so these nutrients were not included in the final model.

Calcium intakes were analyzed as categorical variables and as continuous variables. We used the Dietary Reference Intakes recommended by the US Institute of Medicine as project-wide cut-points for dietary and total calcium intakes (11). Briefly, for men age 19–70 years and women age 19–50 years, the estimated average requirement (EAR) of calcium is 800 mg/d and the recommended dietary allowance (RDA) is 1000 mg/d; for men >70 years and women >50 years, the EAR is 1000 mg/d and the RDA is 1200 mg/d. Participants were classified into five groups based on their calcium intakes: <0.5 RDA, 0.5 RDA to EAR, EAR to RDA, RDA to 1.5 RDA, or >1.5 RDA. The cut-points for supplemental calcium intake were 0, 200, 500, and 1000 mg/d. A joint analysis was conducted by dietary and supplemental calcium intakes to examine specifically the association for supplemental calcium among those with low dietary calcium intake and the association for dietary calcium among those with no or little supplemental calcium intake. Calcium intakes were modeled continuously in restricted cubic spline regression to examine dose-response associations. Patients in the sex-specific top and bottom 1% of calcium intakes were excluded. Three knots were chosen based on model fitness, at the 5th, 50th, and 95th percentiles (corresponding to 425, 910, and 1625 mg/d). The referent intake was 900 mg/d and all potential confounders were included in the spline regression.

Stratified analyses were performed by potential effect modifiers, including age at diagnosis, sex, race/ethnicity, education, smoking, other lifestyle factors, stage, histologic type, grade, and time interval between dietary assessment and cancer diagnosis. P for interaction was evaluated via likelihood ratio test comparing models with and without the interaction term (calcium intake category × stratification variable). Sensitivity analyses were conducted by excluding those diagnosed with lung cancer within two years after baseline, by excluding those who died or were lost to follow-up within three months after diagnoses, or by examining lung cancer-specific mortality. Meta-analysis was applied as an alternative approach to pooled analysis. Cohort-specific HRs and 95% CI were calculated and then combined using a fixed-effect model because no significant between-study heterogeneity was detected. Two-sided P <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc.).

Results

Among 1,679,842 men and women from 12 cohort studies, 23,882 incident primary lung cancer cases were identified during a median follow-up of 7 years (interquartile range: 4–10 years); 19,538 died (16,279 from lung cancer) with a median survival time of 11 months (interquartile range: 4–34 months). The overall 5-year survival rate was 21.3%. Higher survival rates were associated with younger age at diagnosis, female gender, never smoking, fewer pack-years if ever smoked, no history of diabetes, and higher level of physical activity (Table 1). Particularly low 5-year survival rates were found for small cell lung cancer (9.7%), distant stage cancer (5.7%), and undifferentiated tumor cells (10.4%). Dietary calcium intakes were higher in the US and European cohorts than in Asian cohorts (Supplementary Table S1), and were positively associated with past smoking, physical activity, moderate alcohol consumption, BMI, history of diabetes, and use of hormone therapy in women. Prediagnostic dietary calcium intakes did not vary by tumor characteristics.

Table 1.

Characteristics, dietary calcium intake, and 5-year survival rate of lung cancer cases (n=23,882)

| Characteristics | Cases, n | Deaths, n | Dietary calcium intake, mg/da | P for calcium intakeb | 5-year survival rate (95% CI), % | P for survival rateb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis: | ||||||

| < 65 years | 6439 | 5087 | 883 ± 413 | ref | 23.8 (22.8, 24.9) | ref |

| 65–75 years | 13,263 | 11,039 | 930 ± 412 | <0.0001 | 21.0 (20.3, 21.7) | <0.0001 |

| > 75 years | 4180 | 3412 | 947 ± 412 | <0.0001 | 18.0 (16.8, 19.2) | <0.0001 |

|

| ||||||

| Sex: | ||||||

| Female | 11,574 | 9021 | 897 ± 425 | ref | 25.3 (24.5, 26.2) | ref |

| Male | 12,308 | 10,517 | 944 ± 424 | <0.0001 | 17.5 (16.8, 18.2) | <0.0001 |

|

| ||||||

| Race: | ||||||

| White | 19,448 | 16,137 | 979 ± 389 | ref | 21.1 (20.6, 21.7) | ref |

| Black | 1037 | 780 | 789 ± 392 | <0.0001 | 22.5 (19.9, 25.2) | 0.99 |

| Asian | 3140 | 2408 | 593 ± 396 | <0.0001 | 21.8 (20.3, 23.3) | 0.76 |

| Other | 257 | 213 | 924 ± 388 | 0.14 | 20.0 (15.3, 25.2) | 0.99 |

|

| ||||||

| Education: | ||||||

| High school | 9947 | 8181 | 889 ± 409 | ref | 18.8 (18.0, 19.6) | ref |

| Vocational school/Some college | 8140 | 6668 | 963 ± 410 | <0.0001 | 22.2 (21.2, 23.1) | <0.0001 |

| College and graduate school | 5795 | 4689 | 912 ± 414 | 0.002 | 23.6 (22.5, 24.6) | <0.0001 |

|

| ||||||

| Tobacco smoking: | ||||||

| Never | 2948 | 2063 | 867 ± 415 | ref | 31.6 (29.8, 33.3) | ref |

| Former | 9589 | 7972 | 975 ± 420 | <0.0001 | 21.4 (20.6, 22.2) | <0.0001 |

| Current | 11,345 | 9503 | 889 ± 415 | 0.04 | 18.6 (17.8, 19.3) | <0.0001 |

|

| ||||||

| Smoking pack-years in cigarette smokers: | ||||||

| < 30 pack-years | 6187 | 4876 | 946 ± 412 | ref | 22.8 (21.7, 23.9) | ref |

| 30–50 pack-years | 7442 | 6275 | 917 ± 410 | <0.0001 | 19.4 (18.5, 20.3) | <0.0001 |

| > 50 pack-years | 7134 | 6173 | 923 ± 418 | 0.005 | 18.0 (17.1, 18.9) | <0.0001 |

|

| ||||||

| History of diabetes: | ||||||

| No | 22,028 | 17,918 | 913 ± 409 | ref | 21.8 (21.2, 22.3) | ref |

| Yes | 1854 | 1620 | 1007 ± 411 | <0.0001 | 15.5 (13.9, 17.2) | <0.0001 |

|

| ||||||

| Physical activity: | ||||||

| Low | 5674 | 4565 | 836 ± 407 | ref | 20.0 (18.9, 21.0) | ref |

| Middle | 9157 | 7631 | 924 ± 407 | <0.0001 | 20.7 (19.9, 21.6) | 0.22 |

| High | 9051 | 7342 | 969 ± 406 | <0.0001 | 22.6 (21.7, 23.5) | <0.0001 |

|

| ||||||

| Body mass index: | ||||||

| <18.5 kg/m2 | 525 | 423 | 796 ± 408 | 0.0002 | 21.7 (20.9, 22.5) | 0.35 |

| 18.5–25.0 kg/m2 | 10,758 | 8768 | 889 ± 410 | ref | 20.3 (16.9, 24.0) | ref |

| 25.0–30.0 kg/m2 | 8888 | 7294 | 948 ± 411 | <0.0001 | 21.0 (20.1, 21.9) | 0.86 |

| > 30.0 kg/m2 | 3711 | 3053 | 963 ± 408 | <0.0001 | 20.8 (19.5, 22.2) | 0.68 |

|

| ||||||

| Alcohol consumption: | ||||||

| None | 7265 | 5849 | 909 ± 404 | ref | 21.4 (20.5, 22.4) | ref |

| Moderate | 11,414 | 9341 | 989 ± 404 | <0.0001 | 21.9 (21.2, 22.7) | 0.98 |

| Heavy | 5203 | 4348 | 786 ± 411 | <0.0001 | 19.5 (18.5, 20.6) | 0.02 |

|

| ||||||

| Hormone therapy among women: | ||||||

| No | 6686 | 5263 | 867 ± 388 | ref | 24.1 (23.1, 25.2) | ref |

| Yes | 4888 | 3758 | 931 ± 388 | <0.0001 | 27.0 (25.7, 28.3) | <0.0001 |

|

| ||||||

| Histological type: | ||||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 9621 | 7324 | 922 ± 411 | ref | 27.7 (26.8, 28.7) | ref |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 4318 | 3468 | 913 ± 411 | 0.99 | 24.7 (23.4, 26.0) | <0.0001 |

| Other non-small cell carcinoma | 3414 | 2769 | 958 ± 409 | 0.001 | 21.6 (20.2, 23.0) | <0.0001 |

| Small cell carcinoma | 3210 | 2955 | 945 ± 409 | 0.05 | 9.7 (8.7, 10.8) | <0.0001 |

| All other | 3319 | 3022 | 861 ± 410 | <0.0001 | 9.6 (8.7, 10.7) | <0.0001 |

|

| ||||||

| Tumor stage: | ||||||

| Localized | 3489 | 1823 | 921 ± 410 | ref | 56.4 (54.6, 58.1) | ref |

| Regional | 4524 | 3713 | 905 ± 410 | 0.54 | 21.1 (20.0, 22.3) | <0.0001 |

| Distant | 6752 | 6327 | 904 ± 412 | 0.31 | 5.7 (5.2, 6.3) | <0.0001 |

| Unknown | 9117 | 7675 | 940 ± 416 | 0.12 | 20.4 (19.5, 21.2) | <0.0001 |

|

| ||||||

| Tumor grade: | ||||||

| Well differentiated | 1213 | 592 | 843 ± 409 | ref | 57.9 (54.9, 60.8) | ref |

| Moderately differentiated | 2791 | 1953 | 921 ± 409 | <0.0001 | 37.3 (35.5, 39.1) | 0.66 |

| Poorly differentiated | 4560 | 3742 | 925 ± 411 | <0.0001 | 22.2 (21.0, 23.4) | <0.0001 |

| Undifferentiated | 1838 | 1714 | 831 ± 409 | 0.99 | 10.4 (9.0, 11.8) | <0.0001 |

| Unknown | 13,480 | 11,537 | 938 ± 410 | <0.0001 | 16.2 (15.5, 16.8) | <0.0001 |

Mean ± SD, adjusted for age, sex, and total energy intake, per 2000 kcal for women and per 2500 kcal for men.

P-values were corrected for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni method.

A majority of lung cancer patients (78.1%) reported usual dietary calcium intakes from half to 1.5-fold of the RDA; 15.5% of patients consumed <0.5 RDA and 6.4% consumed >1.5 RDA. Low dietary calcium intake (<0.5 RDA) was associated with a small but significantly increased risk of death compared with the recommended calcium intake (800–1200 mg/d) (Table 2); the HRs (95% CIs) were 1.08 (1.03, 1.14) in the model adjusted for age, sex, smoking status, pack-years, and total energy intake; and 1.07 (1.01, 1.13) when further adjusted for known prognostic factors, including stage, histology, and grade. Supplemental calcium intake was not associated with lung cancer survival, although in the basic adjustment model, 200–500 mg/d supplemental calcium appeared to be associated with slightly reduced mortality (Table 2).

Table 2.

Pooled analyses of calcium intake and lung cancer survival (n=23,882)

| Calcium intakes | Deaths / Cases, n | Hazard ratio (95% CI)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1a | Model 2b | ||

| Dietary calcium intake, mg/dc | |||

| <500 or <600 | 3047 / 3705 | 1.08 (1.03, 1.14) | 1.07 (1.01, 1.13) |

| 500–800 or 600–1000 | 7463 / 9190 | 1.04 (1.00, 1.08) | 1.04 (1.00, 1.09) |

| 800–1000 or 1000–1200 | 3531 / 4362 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| 1000–1500 or 1200–1800 | 4205 / 5092 | 1.02 (0.97, 1.07) | 1.05 (1.01, 1.10) |

| >1500 or >1800 | 1292 / 1533 | 1.03 (0.96, 1.09) | 1.04 (0.97, 1.11) |

|

| |||

| Dietary and supplemental calcium intake, mg/dc,d | |||

| <500 or <600 | 1119 / 1352 | 1.04 (0.96, 1.11) | 1.02 (0.95, 1.10) |

| 500–800 or 600–1000 | 4333 / 5212 | 1.01 (0.96, 1.06) | 0.99 (0.94, 1.04) |

| 800–1000 or 1000–1200 | 2695 / 3216 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| 1000–1500 or 1200–1800 | 4364 / 5290 | 0.97 (0.93, 1.02) | 1.01 (0.96, 1.06) |

| >1500 or >1800 | 2507 / 3067 | 0.97 (0.91, 1.02) | 0.99 (0.94, 1.05) |

|

| |||

| Supplemental calcium intake, mg/dd | |||

| None | 7850 / 9387 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| 0–200 | 3524 / 4158 | 0.99 (0.95, 1.04) | 1.01 (0.97, 1.06) |

| 200–500 | 1557 / 1969 | 0.95 (0.90, 1.00) | 1.00 (0.94, 1.05) |

| 500–1000 | 1391 / 1743 | 0.96 (0.91, 1.02) | 1.00 (0.94, 1.06) |

| >1000 | 696 / 880 | 0.97 (0.89, 1.05) | 1.01 (0.93, 1.10) |

Cox model was stratified by cohort, year of lung cancer diagnosis, and time interval between dietary assessment and lung cancer diagnosis and adjusted for age at diagnosis, sex, smoking status, smoking pack-years, and total energy intake.

Additionally adjusted for race, education, alcohol consumption, history of diabetes, physical activity level, obesity status, hormone therapy in women, and the histological type, stage, and grade of lung cancer.

For men ≤70 y and women ≤50 y, the recommended dietary allowance (RDA) of calcium is 1000 mg/d and the estimated average requirement (EAR) is 800 mg/d. For men >70 y and women >50 y, RDA is 1200 mg/d and EAR is 1000 mg/d. Calcium intakes were categorized into five groups: <0.5 RDA, 0.5 RDA to EAR, EAR to RDA, RDA to 1.5 RDA, and >1.5 RDA.

Supplemental calcium intake data were only available in eight US cohorts, n=18,137.

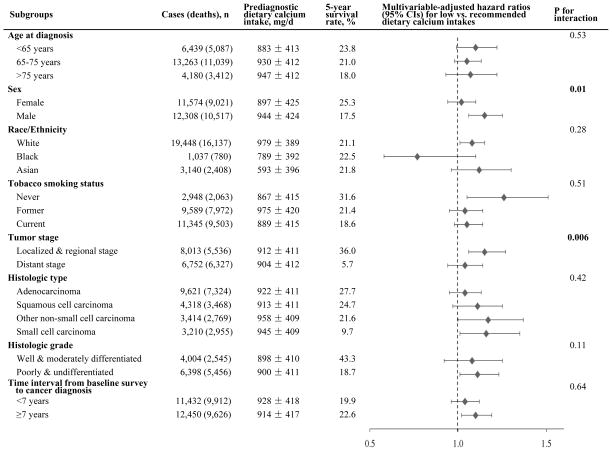

In stratified analysis, the association of low prediagnostic calcium intake with poor lung cancer survival was more evident in men than in women (Pinteraction=0.01), and in early-stage than in distant-stage cases (Pinteraction=0.006) (Figure 1). In particular, low calcium intake (<0.5 RDA vs. RDA) was associated with significantly increased mortality in male patients (HR [95% CI] =1.15 [1.06, 1.25]), and in localized/regional stage patients (HR [95% CI] =1.15 [1.04, 1.27]). We did not observe significant interactions by other potential effect modifiers (Figure 1). Kaplan-Meier survival curves by dietary calcium intakes, stratified by stage, histologic type, and grade, are shown in Supplementary Figure S1.

Figure 1.

Risk of death by prediagnostic dietary calcium intake (low vs. recommended intake) in subgroups of the Calcium and Lung Cancer Pooling Project. Low intake was defined as calcium intake less than half of the recommended dietary allowance (RDA), which is less than 500 mg/d for men ≤70 y and women ≤50 y, or less than 600 mg/d for men >70 y and women >50 y. Recommended intake was defined as calcium intake between the estimated average requirement (EAR) and RDA, which is 800–1000 mg/d for men ≤70 y and women ≤50 y, or 1000–1200 mg/d for men >70 y and women >50 y. The same stratified, multivariable-adjusted Cox model was used as shown in Table 2 footnote.

We thereafter focused our analyses among early-stage cases (Table 3, n=8013). Low dietary calcium intake (<0.5 RDA vs. RDA) was significantly associated with increased lung cancer mortality in early-stage patients, especially for men (HR [95% CI] =1.25 [1.08, 1.45]) and never smokers (HR [95% CI] =1.45 [1.01, 2.08]). Notably, we also observed that a very high calcium intake (>1.5 RDA vs. RDA) was associated with increased mortality in early-stage female patients (HR [95% CI] =1.33 [1.05, 1.70]), although there were only 89 deaths and 134 female patients with a calcium intake this high. Among early-stage patients with low dietary calcium intake, supplemental calcium intake showed a possible trend of inverse association with mortality; compared with no or little supplemental calcium (<200 mg/d), HRs (95% CIs) were 0.90 (0.71, 1.13) and 0.68 (0.44, 1.07) for supplemental calcium of 200–1000 and >1000 mg/d, respectively. Meanwhile, among patients with no or little supplemental calcium intake, the HR (95% CI) for a low dietary calcium intake (<0.5 RDA vs. RDA) was 1.17 (1.02, 1.35).

Table 3.

Dietary calcium intake and lung cancer survival in early stage cases (n=8013)a

| Dietary calcium intake, mg/d | Deaths / Cases, n | Hazard ratio (95% CI)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

| All early stage lung cancer cases: | |||

| <500 or <600 | 928 / 1342 | 1.12 (1.01, 1.24) | 1.15 (1.04, 1.27) |

| 500–800 or 600–1000 | 2083 / 3065 | 1.06 (0.98, 1.14) | 1.06 (0.98, 1.14) |

| 800–1000 or 1000–1200 | 990 / 1442 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| 1000–1500 or 1200–1800 | 1164 / 1660 | 1.00 (0.92, 1.09) | 1.04 (0.96, 1.14) |

| >1500 or >1800 | 371 / 504 | 0.99 (0.88, 1.12) | 1.07 (0.95, 1.21) |

|

| |||

| Female: | |||

| <500 or <600 | 542 / 837 | 1.10 (0.95, 1.28) | 1.08 (0.92, 1.25) |

| 500–800 or 600–1000 | 1076 / 1727 | 1.09 (0.96, 1.24) | 1.03 (0.90, 1.17) |

| 800–1000 or 1000–1200 | 311 / 547 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| 1000–1500 or 1200–1800 | 368 / 591 | 1.11 (0.95, 1.30) | 1.12 (0.96, 1.31) |

| >1500 or >1800 | 89 / 134 | 1.25 (0.98, 1.58) | 1.33 (1.05, 1.70) |

|

| |||

| Male: | |||

| <500 or <600 | 386 / 505 | 1.17 (1.01, 1.36) | 1.25 (1.08, 1.45) |

| 500–800 or 600–1000 | 1007 / 1338 | 1.04 (0.94, 1.15) | 1.07 (0.97, 1.18) |

| 800–1000 or 1000–1200 | 679 / 895 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| 1000–1500 or 1200–1800 | 796 / 1069 | 0.94 (0.85, 1.05) | 0.99 (0.90, 1.10) |

| >1500 or >1800 | 282 / 370 | 0.93 (0.80, 1.06) | 0.99 (0.86, 1.14) |

|

| |||

| Whites: | |||

| <500 or <600 | 507 / 691 | 1.12 (1.00, 1.26) | 1.16 (1.03, 1.31) |

| 500–800 or 600–1000 | 1673 / 2377 | 1.05 (0.97, 1.15) | 1.06 (0.97, 1.15) |

| 800–1000 or 1000–1200 | 873 / 1254 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| 1000–1500 or 1200–1800 | 1103 / 1539 | 1.02 (0.93, 1.11) | 1.05 (0.96, 1.15) |

| >1500 or >1800 | 358 / 480 | 1.01 (0.89, 1.15) | 1.09 (0.96, 1.23) |

|

| |||

| Asians: | |||

| <500 or <600 | 363 / 548 | 1.15 (0.97, 1.35) | 1.20 (1.01, 1.43) |

| 500–1000 or 600–1200 | 326 / 562 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| >1000 or >1200 | 33 / 76 | 0.73 (0.50, 1.05) | 0.76 (0.52, 1.12) |

|

| |||

| Blacks: | |||

| <500 or <600 | 53 / 93 | 0.78 (0.55, 1.09) | 0.79 (0.55, 1.14) |

| 500–1000 or 600–1200 | 171 / 269 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| >1000 or >1200 | 25 / 47 | 0.60 (0.38, 0.95) | 0.77 (0.46, 1.27) |

|

| |||

| Never smokers: | |||

| <500 or <600 | 143 / 260 | 1.32 (0.94, 1.85) | 1.45 (1.01, 2.08) |

| 500–800 or 600–1000 | 204 / 410 | 1.06 (0.73, 1.41) | 1.12 (0.82, 1.53) |

| 800–1000 or 1000–1200 | 71 / 146 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| 1000–1500 or 1200–1800 | 100 / 181 | 1.01 (0.73, 1.40) | 1.06 (0.76, 1.49) |

| >1500 or >1800 | 20 / 41 | 0.84 (0.50, 1.42) | 0.86 (0.50, 1.47) |

|

| |||

| Former / Current smokers: | |||

| <500 or <600 | 785 / 1082 | 1.09 (0.98, 1.21) | 1.12 (1.01, 1.25) |

| 500–800 or 600–1000 | 1879 / 2655 | 1.06 (0.91, 1.09) | 1.05 (0.97, 1.14) |

| 800–1000 or 1000–1200 | 919 / 1296 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| 1000–1500 or 1200–1800 | 1064 / 1479 | 1.00 (0.91, 1.09) | 1.04 (0.95, 1.14) |

| >1500 or >1800 | 351 / 463 | 1.01 (0.89, 1.15) | 1.09 (0.96, 1.23) |

|

| |||

| Localized stage cases: | |||

| <500 or <600 | 293 / 579 | 1.14 (0.96, 1.37) | 1.16 (0.97, 1.40) |

| 500–800 or 600–1000 | 696 / 1346 | 1.12 (0.97, 1.29) | 1.12 (0.97, 1.29) |

| 800–1000 or 1000–1200 | 304 / 604 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| 1000–1500 or 1200–1800 | 405 / 739 | 1.05 (0.91, 1.23) | 1.10 (0.95, 1.28) |

| >1500 or >1800 | 125 / 221 | 0.93 (0.75, 1.15) | 0.97 (0.78, 1.20) |

|

| |||

| Regional stage cases: | |||

| <500 or <600 | 635 / 763 | 1.07 (0.95, 1.21) | 1.10 (0.97, 1.25) |

| 500–800 or 600–1000 | 1387 / 1719 | 1.01 (0.91, 1.11) | 1.02 (0.93, 1.12) |

| 800–1000 or 1000–1200 | 686 / 838 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| 1000–1500 or 1200–1800 | 759 / 921 | 1.00 (0.90, 1.11) | 1.01 (0.90, 1.12) |

| >1500 or >1800 | 246 / 283 | 1.10 (0.95, 1.27) | 1.11 (0.96, 1.29) |

The same covariates and calcium cut-offs as shown in the footnote of Table 2. P for interaction was 0.02 for calcium intake levels with sex, 0.68 with race/ethnicity, 0.70 with smoking, and 0.47 with stage.

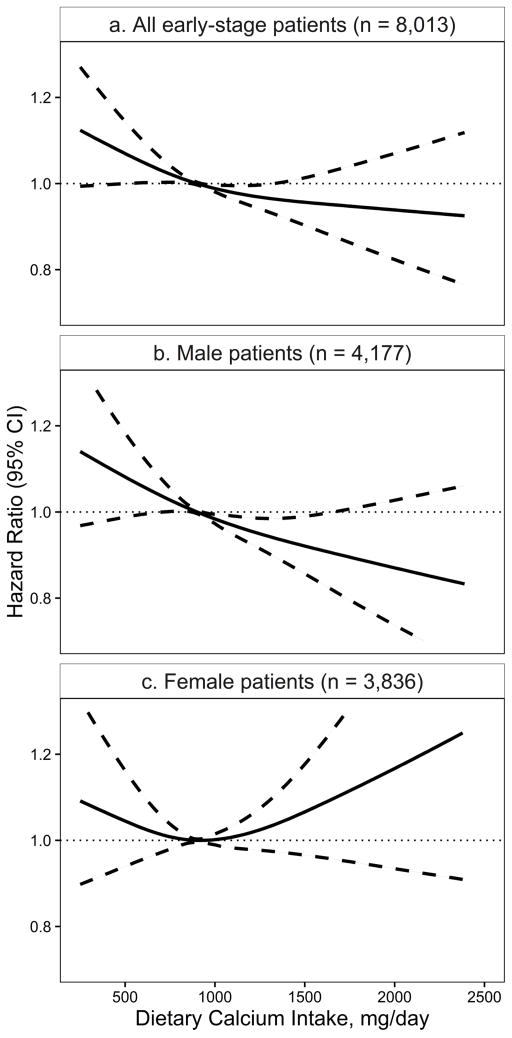

In cubic spline modeling, the lowest mortality among early-stage lung cancer patients was observed for dietary calcium intakes of 800–1200 mg/d (Figure 2a, P=0.03). Consistent with the above findings, low dietary calcium intake was associated with increased mortality, especially among early-stage male patients (Figure 2b). Meanwhile, very high calcium intake may also be associated with increased mortality among early-stage female patients (Figure 2c), although the confidence interval was very wide.

Figure 2.

Risk of death by prediagnostic dietary calcium intake in the Calcium and Lung Cancer Pooling Project (solid line: hazard ratio, dashed line: 95% confidence interval) among: a. early-stage lung cancer patients (P = 0.03); b. early-stage male patients (P = 0.02); and c. early-stage female patients (P = 0.39). The same stratified, multivariable-adjusted Cox model was used as shown in Table 2 footnote.

Results were robust in sensitivity analyses and in meta-analysis. The HRs (95% CI) in early-stage cases for low dietary calcium intake were 1.14 (1.02, 1.28) after excluding those diagnosed within two years after baseline (n=6362), 1.17 (1.05, 1.30) after excluding those who died within three months after diagnosis (n=7246), 1.15 (1.02, 1.28) for lung cancer-specific deaths (cases=4246), and 1.14 (1.02, 1.28) in a fixed-effect meta-analysis (Pheterogeneity=0.39) (Supplementary Figure S2).

Discussion

In this large pooled analysis of 12 cohort studies, we observed that low prediagnostic dietary calcium intake (<500–600 mg/d) was associated with a slightly increased risk of death among lung cancer patients, after taking other prognostic factors into account. The lowest mortality was observed for dietary calcium intakes of 800–1200 mg/d; further increase in calcium intake did not confer additional benefit. The association between low prediagnostic calcium intake and lung cancer survival was primarily confined to early-stage patients. No significant association was found for prediagnostic supplemental calcium intake with lung cancer survival.

Our study provides the first epidemiological evidence that long-term insufficient calcium intake may influence lung cancer prognosis, especially for early-stage patients, when cancer has not spread to other organs. Metastasis is the major reason for cancer-related deaths (50). For lung cancer, a frequent site of metastasis is the bone, occurring in nearly 40% of patients (51–53). Impaired bone metabolism and calcium homeostasis due to a long-term calcium insufficiency may facilitate bone metastasis and promote tumor growth in lung cancer. Calcium is an essential nutrient for bone remodeling (formation and resorption). A prolonged calcium deficiency leads to increased bone resorption and compromised bone health (11). When the circulating calcium level drops because of a low supply, multiple signaling pathways, hormones, and cytokines are affected. Directly, calcium is a second messenger and calcium signaling regulates cell differentiation, proliferation, and apoptosis (10,54). Indirectly, to maintain a proper extracellular calcium level, the body up-regulates secretions of PTH, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D, as well as several bone- or T cell-derived cytokines and growth factors, e.g. receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand (RANKL), macrophage colony-stimulating factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, and interleukin-6 (55). Activation of these pathways enhances tumor growth, promotes angiogenesis and accelerates metastasis (52,55). During tumor progression, bone remodeling and calcium homeostasis are further disturbed. Tumor cells secrete factors that increase RANKL expression and bone resorption; in turn, growth factors released from the bone stimulate tumor growth and metastasis. This vicious cycle of bone destruction and tumor progression is well documented as an unfavorable prognostic factor of lung cancer (53,56,57). A few clinic-based studies have suggested that low blood calcium level and high bone resorption markers are associated with increased bone metastasis and decreased survival time among newly diagnosed lung cancer patients, after controlling for other clinicopathological factors (58–60). Therefore, bone-targeted therapies have been used to reduce bone metastases and prolong lung cancer survival (61,62), and assessments of bone condition and bone metastasis have been recommended throughout lung cancer treatment (63,64). Although limited by a lack of clinical information on patients’ metastasis status or their blood calcium concentration or bone imaging data, our study is the first epidemiologic study to show that patients with habitually low calcium intakes were at a high risk of death. Our findings suggest that assessments of bone health and calcium homeostasis may benefit these patients, especially those diagnosed at early stages, by allowing for a proper intervention.

A U-shaped relationship was found in recent meta-analyses of calcium intake with mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer (65,66). Our results also suggest a possible U-shaped association between dietary calcium and lung cancer survival with an optimal intake around 1000 mg/d; intakes of <500 mg/d (especially among early-stage men) or >1800 mg/d (especially among early-stage women) were both associated with increased mortality. However, the number of patients with excessive dietary calcium intake was too small to draw conclusions from this observation. In addition, the increased risk among very high calcium consumers may indirectly reflect a history of calcium deficiency and poor bone health, leading to a subsequent increase in calcium consumption, particularly for women who are more likely to be affected by and diagnosed with osteoporosis. Although the sex-differential associations we observed could be due to chance, they warrant further investigation. Possible explanations include gender differences in calcium intake level, lung cancer histology, estrogen exposure, and lifestyle habits.

Our study did not find a significant association between supplemental calcium intake and lung cancer survival among the 18,137 incident cases from eight US cohorts that collected this information. The null association may be due to the fact that fewer individuals would have an insufficient calcium intake when taking calcium supplements. If only a long-term low calcium intake was associated with cancer prognosis, a null association for supplemental calcium would be expected. We did observe a possible trend of beneficial association for supplemental calcium among early-stage patients with low dietary calcium intakes (see results section). The null finding could also be due to a suboptimal measurement of usual supplement intake. Nevertheless, this finding is in line with results from randomized, controlled trials which found no significant effects of calcium supplements on cancer incidence or mortality (67–69). Taken together, our results support the hypothesis that an optimal calcium intake from foods may favorably impact cancer survival; however, evidence is lacking for a recommendation to use calcium supplements to increase intake, especially among those already consuming a sufficient amount of dietary calcium.

Our study has several limitations. First, dietary intakes were measured via FFQs and food composition tables, both of which have non-negligible measurement errors. Although FFQs used in participating cohorts have each been validated and shown reasonably good validities (37–45,47,48), measurement errors cannot be precluded. Non-differential misclassifications of calcium intakes may bias our risk ratio estimates towards the null. Second, information on post-diagnostic calcium intake, comorbidity status at the time of diagnosis, and cancer treatment were unavailable, and tumor stage and grade data were missing in a sizable fraction of patients. Cancer treatment and comorbidities may affect calcium homeostasis, which may exacerbate the hazardous effect of a pre-existing low calcium status. Lack of treatment and comorbidity information prevented us from investigating this hypothesis. Most of our study patients were diagnosed before 2010 when targeted treatments were less common and lung cancer treatments were largely based on stage, histology, and patient sociodemographics. We adjusted for all these factors, as well as baseline diabetes and obesity status, and stratified by cohort (region) and year of diagnosis. We also conducted a number of subgroup analyses and did not find significant effect modifications except by stage. Moreover, patient tumor characteristics (including the unknown category) were not associated with prediagnostic calcium intake, suggesting that these clinical factors were unlikely to substantially confound the association. Third, despite the large sample size, statistical power remained limited in certain subgroup analyses, such as the interaction analysis by race/ethnicity and the analysis among never smokers. For example, we found a seemingly opposite association in Blacks, but the small number of black patients and the insignificant interaction with race/ethnicity prevented us from drawing any conclusions. Finally, we cannot separate the effects of calcium from related nutrients, including vitamin D, magnesium, phosphorus, and other nutrients in calcium-rich foods, nor could we rule out residual confounding from unknown confounders and imperfectly measured covariates, which may be particularly challenging in pooling projects using harmonized data from multiple studies.

Strengths of our study include its prospective design, large sample size, and pooled data analysis. The prospective study design minimized reverse causality and biases of recall and selection. Pooled individual-level data from 12 cohort studies in three continents enabled us to evaluate the associations among populations with a broad range of exposures and by clinical characteristics, and to examine calcium intake via multiple approaches, i.e., using project-wide cut-points, as continuous variables, and in a series of sensitivity analyses. Results for low dietary calcium intake and poorer survival were largely consistent when using different approaches.

In summary, in this large pooled analysis, we found that low prediagnostic dietary calcium intake (<500–600 mg/d) was associated with a small increased risk of death among localized and regional stage lung cancer patients. Further studies with biomarker data and more detailed clinical data are needed to confirm or refute our findings. Meanwhile, studies are needed to explore biological mechanisms linking calcium nutrition, calcium homeostasis, and bone remodeling with lung cancer progression, as well as to investigate modifiable nutrition and lifestyle factors to improve survival for lung cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health to Drs. X-O Shu and Y Takata [R03 CA183021]. The National Cancer Institute had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

We thank the staff and investigators of all participating cohorts for their dedicated efforts. We thank Ms. Nancy Kennedy for her assistance in editing and preparing the manuscript.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Global Cancer Facts & Figures. 3. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howlader N, Noone A, Krapcho M, Garshell J, Miller D, Altekruse S, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2012. [Internet] Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2015. Available from: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2012/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brenner H, Francisci S, de Angelis R, Marcos-Gragera R, Verdecchia A, Gatta G, et al. Long-term survival expectations of cancer patients in Europe in 2000–2002. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:1028–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zeng H, Zheng R, Guo Y, Zhang S, Zou X, Wang N, et al. Cancer survival in China, 2003–2005: a population-based study. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:1921–30. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sculier J-P, Chansky K, Crowley JJ, Van Meerbeeck J, Goldstraw P International Staging Committee and Participating Institutions. The impact of additional prognostic factors on survival and their relationship with the anatomical extent of disease expressed by the 6th Edition of the TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors and the proposals for the 7th Edition. J Thorac Oncol Off Publ Int Assoc Study Lung Cancer. 2008;3:457–66. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31816de2b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zeng C, Wen W, Morgans AK, Pao W, Shu X-O, Zheng W. Disparities by Race, Age, and Sex in the Improvement of Survival for Major Cancers: Results From the National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program in the United States, 1990 to 2010. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:88–96. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2014.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang G, Shu X-O, Li H-L, Chow W-H, Wen W, Xiang Y-B, et al. Prediagnosis Soy Food Consumption and Lung Cancer Survival in Women. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1548–53. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.0942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu Q-J, Yang G, Zheng W, Li H-L, Gao J, Wang J, et al. Pre-diagnostic cruciferous vegetables intake and lung cancer survival among Chinese women. Sci Rep. 2015;5:10306. doi: 10.1038/srep10306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hasegawa Y, Ando M, Maemondo M, Yamamoto S, Isa S-I, Saka H, et al. The role of smoking status on the progression-free survival of non-small cell lung cancer patients harboring activating epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations receiving first-line EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor versus platinum doublet chemotherapy: a meta-analysis of prospective randomized trials. The Oncologist. 2015;20:307–15. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peterlik M, Grant WB, Cross HS. Calcium, vitamin D and cancer. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:3687–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ross AC, Taylor CL, Yaktine AL, Del Valle HB, editors. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee to Review Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin D and Calcium. Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D [Internet] Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2011. [cited 2015 Nov 24]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK56070/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peterlik M, Kállay E, Cross HS. Calcium nutrition and extracellular calcium sensing: relevance for the pathogenesis of osteoporosis, cancer and cardiovascular diseases. Nutrients. 2013;5:302–27. doi: 10.3390/nu5010302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park Y, Leitzmann MF, Subar AF, Hollenbeck A, Schatzkin A. Dairy food, calcium, and risk of cancer in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:391–401. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cho E, Smith-Warner SA, Spiegelman D, Beeson WL, van den Brandt PA, Colditz GA, et al. Dairy foods, calcium, and colorectal cancer: a pooled analysis of 10 cohort studies. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1015–22. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huncharek M, Muscat J, Kupelnick B. Colorectal cancer risk and dietary intake of calcium, vitamin D, and dairy products: a meta-analysis of 26,335 cases from 60 observational studies. Nutr Cancer. 2009;61:47–69. doi: 10.1080/01635580802395733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin J, Manson JE, Lee I-M, Cook NR, Buring JE, Zhang SM. Intakes of calcium and vitamin D and breast cancer risk in women. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1050–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.10.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen P, Hu P, Xie D, Qin Y, Wang F, Wang H. Meta-analysis of vitamin D, calcium and the prevention of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;121:469–77. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0593-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson KM, Shui IM, Mucci LA, Giovannucci E. Calcium and phosphorus intake and prostate cancer risk: a 24-y follow-up study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;101:173–83. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.088716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aune D, Navarro Rosenblatt DA, Chan DSM, Vieira AR, Vieira R, Greenwood DC, et al. Dairy products, calcium, and prostate cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;101:87–117. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.067157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mahabir S, Forman MR, Dong YQ, Park Y, Hollenbeck A, Schatzkin A. Mineral intake and lung cancer risk in the NIH-American Association of Retired Persons Diet and Health study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev Publ Am Assoc Cancer Res Cosponsored Am Soc Prev Oncol. 2010;19:1976–83. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li K, Kaaks R, Linseisen J, Rohrmann S. Dietary calcium and magnesium intake in relation to cancer incidence and mortality in a German prospective cohort (EPIC-Heidelberg) Cancer Causes Control CCC. 2011;22:1375–82. doi: 10.1007/s10552-011-9810-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takata Y, Shu X-O, Yang G, Li H, Dai Q, Gao J, et al. Calcium intake and lung cancer risk among female nonsmokers: a report from the Shanghai Women’s Health Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev Publ Am Assoc Cancer Res Cosponsored Am Soc Prev Oncol. 2013;22:50–7. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0915-T. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dik VK, Murphy N, Siersema PD, Fedirko V, Jenab M, Kong SY, et al. Prediagnostic intake of dairy products and dietary calcium and colorectal cancer survival--results from the EPIC cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev Publ Am Assoc Cancer Res Cosponsored Am Soc Prev Oncol. 2014;23:1813–23. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang B, McCullough ML, Gapstur SM, Jacobs EJ, Bostick RM, Fedirko V, et al. Calcium, vitamin D, dairy products, and mortality among colorectal cancer survivors: the Cancer Prevention Study-II Nutrition Cohort. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2335–43. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.3024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schatzkin A, Subar AF, Thompson FE, Harlan LC, Tangrea J, Hollenbeck AR, et al. Design and serendipity in establishing a large cohort with wide dietary intake distributions: the National Institutes of Health-American Association of Retired Persons Diet and Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154:1119–25. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.12.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Michaud DS, Liu Y, Meyer M, Giovannucci E, Joshipura K. Periodontal disease, tooth loss, and cancer risk in male health professionals: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:550–8. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70106-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baik CS, Strauss GM, Speizer FE, Feskanich D. Reproductive factors, hormone use, and risk for lung cancer in postmenopausal women, the Nurses’ Health Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev Publ Am Assoc Cancer Res Cosponsored Am Soc Prev Oncol. 2010;19:2525–33. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sinner P, Folsom AR, Harnack L, Eberly LE, Schmitz KH. The association of physical activity with lung cancer incidence in a cohort of older women: the Iowa Women’s Health Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev Publ Am Assoc Cancer Res Cosponsored Am Soc Prev Oncol. 2006;15:2359–63. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu CS, Pinsky PF, Kramer BS, Prorok PC, Purdue MP, Berg CD, et al. The prostate, lung, colorectal, and ovarian cancer screening trial and its associated research resource. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:1684–93. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Signorello LB, Hargreaves MK, Blot WJ. The Southern Community Cohort Study: Investigating Health Disparities. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21:26–37. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.White E, Patterson RE, Kristal AR, Thornquist M, King I, Shattuck AL, et al. VITamins And Lifestyle cohort study: study design and characteristics of supplement users. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:83–93. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Langer RD, White E, Lewis CE, Kotchen JM, Hendrix SL, Trevisan M. The women’s health initiative observational study: baseline characteristics of participants and reliability of baseline measures. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13:S107–21. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(03)00047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Riboli E, Hunt KJ, Slimani N, Ferrari P, Norat T, Fahey M, et al. European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC): study populations and data collection. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5:1113–24. doi: 10.1079/PHN2002394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsugane S, Sawada N. The JPHC study: design and some findings on the typical Japanese diet. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2014;44:777–82. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyu096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shu X-O, Li H, Yang G, Gao J, Cai H, Takata Y, et al. Cohort Profile: The Shanghai Men’s Health Study. Int J Epidemiol. 2015:dyv013. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zheng W, Chow W-H, Yang G, Jin F, Rothman N, Blair A, et al. The Shanghai Women’s Health Study: rationale, study design, and baseline characteristics. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162:1123–31. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thompson FE, Kipnis V, Midthune D, Freedman LS, Carroll RJ, Subar AF, et al. Performance of a food-frequency questionnaire in the US NIH-AARP (National Institutes of Health-American Association of Retired Persons) Diet and Health Study. Public Health Nutr. 2008;11:183–95. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007000419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Willett WC, Sampson L, Stampfer MJ, Rosner B, Bain C, Witschi J, et al. Reproducibility and validity of a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;122:51–65. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rimm EB, Giovannucci EL, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Litin LB, Willett WC. Reproducibility and validity of an expanded self-administered semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire among male health professionals. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;135:1114-1126-1136. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Munger RG, Folsom AR, Kushi LH, Kaye SA, Sellers TA. Dietary Assessment of Older Iowa Women with a Food Frequency Questionnaire: Nutrient Intake, Reproducibility, and Comparison with 24-Hour Dietary Recall Interviews. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;136:192–200. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Subar AF, Thompson FE, Kipnis V, Midthune D, Hurwitz P, McNutt S, et al. Comparative Validation of the Block, Willett, and National Cancer Institute Food Frequency Questionnaires The Eating at America’s Table Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154:1089–99. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.12.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Signorello LB, Munro HM, Buchowski MS, Schlundt DG, Cohen SS, Hargreaves MK, et al. Estimating nutrient intake from a food frequency questionnaire: incorporating the elements of race and geographic region. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170:104–11. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Patterson RE, Kristal AR, Tinker LF, Carter RA, Bolton MP, Agurs-Collins T. Measurement characteristics of the Women’s Health Initiative food frequency questionnaire. Ann Epidemiol. 1999;9:178–87. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(98)00055-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Slimani N, Ferrari P, Ocké M, Welch A, Boeing H, Liere M, et al. Standardization of the 24-hour diet recall calibration method used in the european prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition (EPIC): general concepts and preliminary results. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2000;54:900–17. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ishihara J, Sobue T, Yamamoto S, Yoshimi I, Sasaki S, Kobayashi M, et al. Validity and reproducibility of a self-administered food frequency questionnaire in the JPHC Study Cohort II: study design, participant profile and results in comparison with Cohort I. J Epidemiol Jpn Epidemiol Assoc. 2003;13:S134–147. doi: 10.2188/jea.13.1sup_134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tsubono Y, Kobayashi M, Sasaki S, Tsugane S, JPHC Validity and reproducibility of a self-administered food frequency questionnaire used in the baseline survey of the JPHC Study Cohort I. J Epidemiol Jpn Epidemiol Assoc. 2003;13:S125–133. doi: 10.2188/jea.13.1sup_125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Villegas R, Yang G, Liu D, Xiang Y-B, Cai H, Zheng W, et al. Validity and reproducibility of the food-frequency questionnaire used in the Shanghai men’s health study. Br J Nutr. 2007;97:993–1000. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507669189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shu XO, Yang G, Jin F, Liu D, Kushi L, Wen W, et al. Validity and reproducibility of the food frequency questionnaire used in the Shanghai Women’s Health Study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2004;58:17–23. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Willett WC, Howe GR, Kushi LH. Adjustment for total energy intake in epidemiologic studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;65:1220S–1228S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/65.4.1220S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mehlen P, Puisieux A. Metastasis: a question of life or death. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:449–58. doi: 10.1038/nrc1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Coleman RE. Clinical features of metastatic bone disease and risk of skeletal morbidity. Clin Cancer Res Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res. 2006;12:6243s–6249s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brodowicz T, O’Byrne K, Manegold C. Bone matters in lung cancer. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol ESMO. 2012;23:2215–22. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Riihimäki M, Hemminki A, Fallah M, Thomsen H, Sundquist K, Sundquist J, et al. Metastatic sites and survival in lung cancer. Lung Cancer Amst Neth. 2014;86:78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang H, Zhang Q, He J, Lu W. Regulation of calcium signaling in lung cancer. J Thorac Dis. 2010;2:52–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roodman GD. Mechanisms of bone metastasis. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1655–64. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra030831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cetin K, Christiansen CF, Jacobsen JB, Nørgaard M, Sørensen HT. Bone metastasis, skeletal-related events, and mortality in lung cancer patients: a Danish population-based cohort study. Lung Cancer Amst Neth. 2014;86:247–54. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mountzios G, Ramfidis V, Terpos E, Syrigos KN. Prognostic significance of bone markers in patients with lung cancer metastatic to the skeleton: a review of published data. Clin Lung Cancer. 2011;12:341–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2011.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shen H, Li Y, Liao Y, Zhang T, Liu Q, Du J. Lower blood calcium associates with unfavorable prognosis and predicts for bone metastasis in NSCLC. PloS One. 2012;7:e34264. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tamiya M, Kobayashi M, Morimura O, Yasue T, Nakasuji T, Satomu M, et al. Clinical significance of the serum crosslinked N-telopeptide of type I collagen as a prognostic marker for non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2013;14:50–4. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2012.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang Z, Lu Y, Qiao D, Wen X, Zhao H, Yao Y. Diagnostic and prognostic validity of serum bone turnover markers in bone metastatic non-small cell lung cancer patients. J Bone Oncol. 2015;4:85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jbo.2015.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lopez-Olivo MA, Shah NA, Pratt G, Risser JM, Symanski E, Suarez-Almazor ME. Bisphosphonates in the treatment of patients with lung cancer and metastatic bone disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer Off J Multinatl Assoc Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:2985–98. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1563-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.De Castro J, García R, Garrido P, Isla D, Massuti B, Blanca B, et al. Therapeutic Potential of Denosumab in Patients With Lung Cancer: Beyond Prevention of Skeletal Complications. Clin Lung Cancer. 2015;16:431–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.De Marinis F, Eberhardt W, Harper PG, Sureda BM, Nackaerts K, Soerensen JB, et al. Bisphosphonate use in patients with lung cancer and bone metastases: recommendations of a European expert panel. J Thorac Oncol Off Publ Int Assoc Study Lung Cancer. 2009;4:1280–8. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181b68e5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Langer C, Hirsh V. Skeletal morbidity in lung cancer patients with bone metastases: demonstrating the need for early diagnosis and treatment with bisphosphonates. Lung Cancer Amst Neth. 2010;67:4–11. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2009.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang X, Chen H, Ouyang Y, Liu J, Zhao G, Bao W, et al. Dietary calcium intake and mortality risk from cardiovascular disease and all causes: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMC Med. 2014;12:158. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0158-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Asemi Z, Saneei P, Sabihi S-S, Feizi A, Esmaillzadeh A. Total, dietary, and supplemental calcium intake and mortality from all-causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2015;25:623–34. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brunner RL, Wactawski-Wende J, Caan BJ, Cochrane BB, Chlebowski RT, Gass MLS, et al. The effect of calcium plus vitamin D on risk for invasive cancer: results of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) calcium plus vitamin D randomized clinical trial. Nutr Cancer. 2011;63:827–41. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2011.594208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Avenell A, MacLennan GS, Jenkinson DJ, McPherson GC, McDonald AM, Pant PR, et al. Long-term follow-up for mortality and cancer in a randomized placebo-controlled trial of vitamin D(3) and/or calcium (RECORD trial) J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:614–22. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bolland MJ, Grey A, Gamble GD, Reid IR. The effect of vitamin D supplementation on skeletal, vascular, or cancer outcomes: a trial sequential meta-analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2:307–20. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70212-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.