Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the association between dry eye (DE) and insomnia symptom severity.

Methods

Cross-sectional study of 187 individuals seen in the Miami Veterans Affairs eye clinic. An evaluation was performed consisting of questionnaires regarding insomnia (Insomnia Severity Index (ISI)) and DE symptoms, including ocular pain; followed by a comprehensive ocular surface examination. Using a two-step cluster analysis based on intensity ratings of ocular pain, the patient population was divided into two groups (High and Low Ocular Pain groups, HOP and LOP). A control group was ascertained at the same time from the same clinic as defined by no symptoms of DE (Dry Eye Questionnaire 5 (DEQ5) < 6). The main outcome measure was frequency of moderate or greater insomnia in the DE groups.

Results

The mean age of the study sample was 63 years and 93% were male. All insomnia complaints were rated higher in the HOP group compared to the LOP and control groups, p<0.0005. A majority of individuals in the HOP group (61%) had insomnia of at least moderate severity (ISI≥15) compared to the LOP (41%) and control groups (18%), p-value<0.0005. Black race (odds ratio (OR) 2.7, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.2–6.0, p=0.02), depression severity (OR=1.2, 95% CI 1.1–1.3, p<0.0005), and DE symptom severity (DEQ5, OR 1.1, 95% CI 1.01–1.2, p=0.03) were significantly associated with clinical insomnia (ISI≥15) after controlling for potential confounders.

Conclusions

After adjusting for demographics and medical comorbidities, we show that DE symptom severity is positively associated with insomnia severity.

Keywords: Insomnia, dry eye, ocular pain

Introduction

Dry eye (DE) is a common condition reported to affect 15% of the general population.1 It is a heterogeneous disorder that can manifest with symptoms (dysesthesias, pain, visual complaints) and/or ocular surface signs (abnormal tear production, evaporation, increased osmolarity, damage to the ocular surface).2 The morbidity of DE comes from its symptoms, which decrease quality of life by affecting physical function and mental health.3

DE has traditionally been sub-categorized based on the findings of aqueous and/or evaporative deficiency.2 Newer data suggest that somatosensory dysfunction may be another component of DE that underlies symptoms in some individuals.4,5 Data to support this statement consist of ocular complaints which mirror neuropathic pain elsewhere in the body including spontaneous pain, dissociation between symptoms and peripheral findings, characterizing ocular dysesthesias as “hot-burning”, and sensitivity to light and wind (which can be construed as allodynia and hyperalgesia, respectively).6 Furthermore, we and others have previously shown that DE symptoms are often found in the setting of systemic co-morbidities such as chronic widespread musculoskeletal pain, chronic pelvic pain, migraine, irritable bowel syndrome, and other chronic pain conditions7–10, and their co-existence has been termed “chronic overlapping pain conditions (COPC)”.11–13 COPC are also associated with other co-morbidities including mood disorders, insomnia symptoms (difficulty with falling asleep, staying asleep, or with premature awakenings), and decreased quality of life.14,15 Many studies have previously focused on the link between DE and mental health, demonstrating that DE symptoms correlated with anxiety and depression more strongly than they did with tear film findings.16–20 Less data, however, is available on associations between DE symptoms and insomnia, while adjusting for potential confounders.21–23 One population based Korean study found an increased risk of DE in those with mild and severe sleep disturbances, as compared to a control group with optimal sleep (6–8 h/day).23 Another hospital based Japanese study found a positive correlation between Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index scores and DE severity.21 In this study, we aimed to re-evaluate the latter association in a unique, predominately male, United States based-population with a balanced racial and ethnic profile. We hypothesized that DE symptom severity and specific ocular pain complaints would be associated with clinically significant insomnia, after adjusting for demographics, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and other medical comorbidities.

Methods

Study Population

Patients with otherwise healthy eyelid and corneal anatomy were prospectively recruited from the Miami Veterans Affairs (VA) Healthcare System eye clinic from October 2013 to February 2016. Patients with a history of contact lens use, any history of refractive, glaucoma, or retina surgery, cataract surgery within the preceding 6 months, any use of ocular medications other than artificial tears, medical history of human immunodeficiency virus, sarcoidosis, graft-versus host disease, or collagen vascular diseases were excluded. All patients signed an informed consent form prior to beginning study activities. The study was conducted in accordance to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, complied with the requirements of the United States Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, and was approved by the Miami VA Institutional Review Board.

Data Collected

For each individual, demographic information, past ocular and medical history and medication information was collected via self-report structured questionnaire and confirmed via the medical record. The Charlson comorbidity weighted index was calculated based on review of the medical record.24 Mental health status was assessed using the patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) for depression25, the PTSD questionnaire (PTSD Checklist – Military Version)26 for PTSD, and the symptom check list (SCL)-90 for anxiety.27 Diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) was determined by self-report and review of medical record.

Dry eye symptoms

Patients filled out standardized questionnaires regarding DE symptoms: the DE questionnaire 5 (DEQ5)28 and the ocular surface disease index (OSDI).29 A cut-off of 6 or greater on the DEQ5 was used to define a sample of patients with mild or greater DE symptoms and those with DEQ5 scores less than 6 were considered controls free of DE symptoms.28

Ocular pain complaints

An 11 point numerical rating scale (NRS) was used to assess ocular pain intensity (“How would you describe the overall intensity of your eye pain, on average during the last week?), anchored at 0 for no ocular pain and at 10 for the most intense ocular pain imaginable. Based on prior data, 3 additional ocular pain complaints were assessed30: (1) presence of spontaneous burning ocular pain; presence of evoked pain (ocular pain caused or increased by (2) wind and (3) light, all rated on a scale from 0–10). Using responses from these 3 questions, we divided our sample into two groups by cluster analysis. The clustering method used was two-step cluster analysis (IBM SPSS v22). Briefly, in step one, the procedure produces a Cluster Features tree, in which every case is added to an existing node of the tree or becomes a new node based on its log-likelihood distance from previously created nodes, given the variables used for clustering. In the second step, nodes of the tree are agglomeratively formed into clusters. In this step the program uses Schwarz’s Bayesian Information Criterion to select the best number of clusters (≤15). The two generated groups were significantly different from each other regarding both “traditional” DE symptoms (DEQ5, OSDI) and ocular pain complaints (burning pain, sensitivity to wind and light), Table 1. Since we wish to base our classification of these patients on just three variables, which have proved important in previous studies10,30,31, we did not perform dimensional reduction with factor analysis/principal components. Further, keeping these variables in their original units will aid our interpretation of the clusters. This division resulted in 3 groups of patients: (1) those with DE symptoms (DEQ5≥6) and high ocular pain complaints (HOP); (2) those with DE symptoms (DEQ5≥6) and low ocular pain (LOP) complaints; and (3) controls without DE symptoms (DEQ5<6). Of note, none of the control patients had ocular pain complaints. Subsequent analysis was performed based on these 3 patients groups.

Table 1.

Demographics, co-morbidities, and DE metrics in the study sample by clusters

| DE symptoms, High Ocular Pain* (N=49) |

DE symptoms, Low Ocular Pain* (N=104) |

No DE Symptoms (N=34) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Demograhics | |||

| Age, mean (SD) | 61 (10) | 63 (9) | 63 (11) |

| Gender, male, n (%) | 44 (90%) | 97 (93%) | 32 (94%) |

| Race, white, n (%) | 24 (49%) | 53 (51%) | 20 (59%) |

| Ethnicity, Hispanic, n (%) | 14 (29%) | 34 (33%) | 6 (18%) |

| Co-morbidities | |||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 38 (78%) | 76 (73%) | 28 (82%) |

| Hypercholesterolemia, n (%) | 29 (59%) | 63 (61%) | 23 (68%) |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 8 (16%)b | 38 (37%) | 6 (18%)b |

| Sleep apnea, n (%) | 13 (27%) | 24 (23%) | 4 (12%) |

| BPH, n (%) | 9 (18%) | 19 (18%) | 4 (12%) |

| Charlson comorbidity index, mean (SD) |

1.22 (1.36) | 1.43 (1.37) | 1.01 (1.29) |

| Mental health, mean (SD) | |||

| Depression (PHQ9),(range 0–27) | 12.8 (7.9)a,b | 8.8 (7.1)a | 4.3 (7.2) |

| PTSD, (range 17–85) | 51.0 (21.7)a,b | 38.1 (17.0)a | 27.1 (14.4) |

| Anxiety (SCL-90), (range 0–4) | 1.4 (1.3)a,b | 0.66 (0.92) | 0.38 (0.82) |

| Medications | |||

| Anxiolytic, n (%) | 28 (57%)a,b | 39 (38%)a | 6 (18%) |

| Antidepressant, n (%) | 27 (55%)a | 41 (39%)a | 5 (15%) |

| Anti-histamine, n (%) | 13 (27%) | 18 (17%) | 7 (21%) |

| Analgesics, n (%) | 40 (82%)a,b | 65 (63%)a | 12 (35%) |

| Ocular symptoms, mean (SD) | |||

| DEQ5 (range 0–22) | 15.2 (3.4)a,b | 11.6 (3.4)a | 2 (1.9) |

| OSDI (range 0–100) | 53.8 (23.4)a,b | 30.3 (21.2)a | 10.5 (13.6) |

| Ocular pain intensity, averaged over past week (NRS; range 0–10) |

6.0 (1.8)a,b | 2.7 (2.1)a | 0.44 (0.82) |

| Hot burning pain (range 0–10)† | 6.5 (2.4)a,b | 1.8 (2.2)a | 0.15 (0.56) |

| Sensitivity to wind (range 0–10)† | 7.0 (2.3)a,b | 0.97 (1.3)a | 0.15 (0.56) |

| Sensitivity to light (range 0–10)† | 6.7 (2.9)a,b | 1.8 (2.1)a | 0.27 (0.99) |

| Ocular Surface Exam, mean (SD)** | |||

| Tear osmolarity, mOsm/L | 311 (21) | 304 (14) | 307 (17) |

| Tear film breakup time, seconds | 9.5 (4.0) | 9.7 (4.1) | 10.3 (5.5) |

| Corneal staining, (0–15) | 1.2 (1.8) | 2.0 (2.4) | 1.6 (2.0) |

| Schirmer’s test, mm of moisture | 13.8 (7.0) | 12.4 (6.8) | 14.6 (8.8) |

| Eyelid vascularity, (0–3) | 0.63 (0.70) | 0.64 (0.77) | 0.59 (0.74) |

| Meibum quality, (0–4) | 1.9 (1.3) | 2.0 (1.3) | 1.6 (1.2) |

SD=standard deviation; n=number in each group; BPH=benign prostatic hypertrophy; NRS=numerical rating scale for eye pain

Symptoms of DE defined as DEQ5≥6; Ocular pain status defined by cluster analysis

Questions from neuropathic pain symptom inventory, modified for the eye7

Signs from more severely affected eye

Significantly different (p<0.05) from no DE symptom group

Significantly different (p<0.05) from Low Ocular Pain group

Ocular surface evaluation

All patients underwent tear film assessment, including measurement of (1) tear osmolarity (TearLAB, San Diego, CA) (once in each eye); (2) tear breakup time (TBUT) (5 µl fluorescein placed, 3 measurements taken in each eye and averaged); (3) corneal epithelial cell disruption measured via corneal staining (National Eye Institute (NEI) scale,32 5 areas of cornea assessed; score 0–3 in each, total 15); (4) tear production (10µl of anesthesia placed in the inferior fornix of each eye followed by Schirmer’s strips which were left in place for 5 minutes); and (5) meibomian gland assessment. Eyelid vascularity was graded on a scale of 0 to 3 (0 none; 1 mild engorgement; 2 moderate engorgement; 3 severe engorgement) and meibum quality on a scale of 0 to 4 (0 = clear; 1 = cloudy; 2 = granular; 3 = toothpaste; 4 = no meibum extracted).

Insomnia severity index (ISI)

Our primary outcome was the Insomnia severity index, a brief, 7 item instrument measuring the patient’s perception of his or her insomnia. The first 3 items assess the severity of sleep-onset and sleep maintenance difficulties and difficulties with premature early awakenings, respectively. The last 4 items evaluate satisfaction with current sleep pattern, interference with daily functioning, noticeability of impairment attributed to the sleep problem, and degree of distress or concern caused by the sleep problem. The total scores range from 0 to 28, with a cutoff score of 15 suggestive of clinically significant insomnia.33 Its internal consistency, concurrent validity and sensitivity to clinical improvements are well established.33

Statistical Analysis

Data were entered into a standardized database. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 22.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) statistical package. Analysis of Variance and Chi Square tests were used, as appropriate, to compare insomnia profiles between DE groups. Correlations of DE and insomnia symptoms were examined with Pearson r and Spearman rho analyses. We elected to give information on both correlations as the Pearson correlation coefficient has the intuitive interpretation as a percentage of variance explained while the Spearman correlation is sensitive to non-linear monotonic trends and resistant to undue influence by outliers. A multivariable analysis was performed to assess the relationship between DE symptoms and insomnia, while controlling for potential confounders. Covariates (age, gender, self-reported race, medical and psychiatric comorbidities) for insomnia were based on prior epidemiologic research.34 A P value of < 0.05 was deemed significant.

Results

Demographics and co-morbidities by DE sub-group

One hundred eighty-seven veterans participated in the study (mean age 63 years, 93% men). Full demographic characteristics of the study sample, grouped by no DE and DE with low and high ocular pain complaints, are presented in Table 1. All groups were predominantly male with comparable demographics. Individual and weighted medical co-morbidities were likewise similar between groups with the exception of diabetes mellitus which was more frequent in the LOP group (37%) compared to the HOP group (16%) and the no DE group (18%), p=0.02. Mental health indices and medication profiles, on the other hand, were different between the groups. Patients in the HOP group had higher depression, PTSD, and anxiety scores than the LOP and control groups. Similarly, individuals in the HOP group were more frequently prescribed anxiolytics (57%), antidepressants (55%), and analgesics (82%) compared to the LOP and the control groups, p<0.05 for all.

Insomnia symptoms by DE sub-group classification

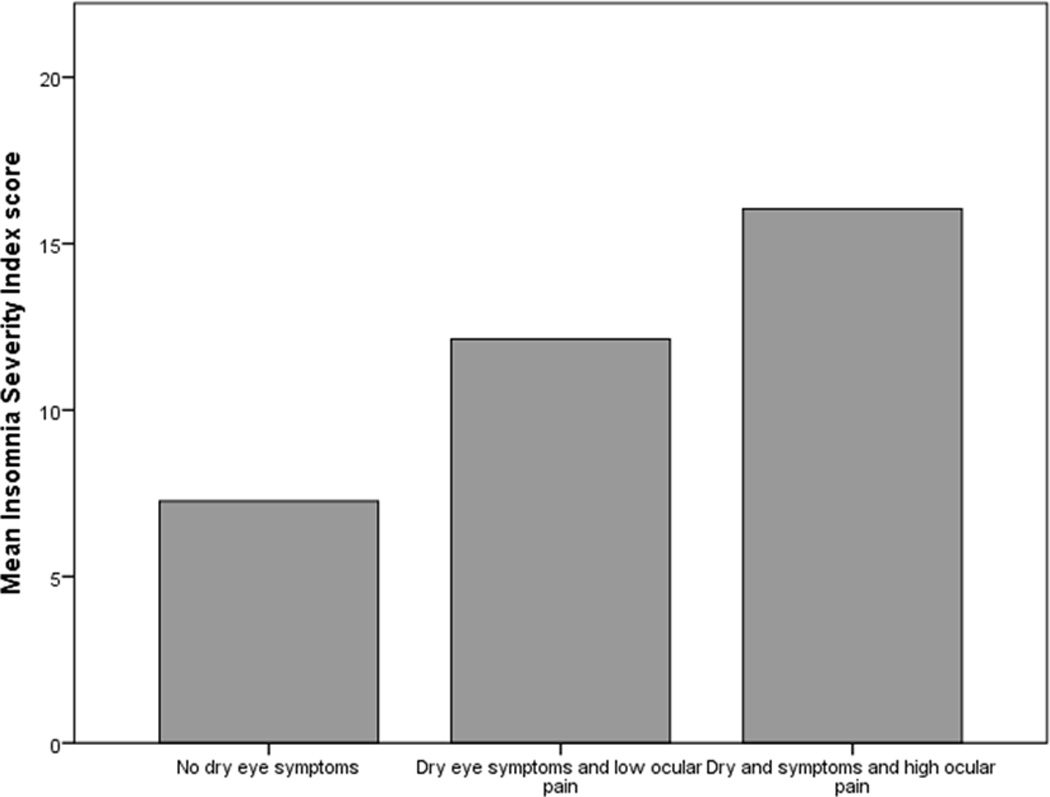

All individual ISI endpoints (mean) were higher in the HOP group compared to the LOP and control groups, with significant differences between the groups with regards to most insomnia metrics (Table 2). Of note, clinically significant insomnia (total score ≥ 15) was found in the majority of individuals in the HOP (61%) group but in lower frequencies in the LOP (41%) and control groups (18%), p-value<0.0005 (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Insomnia symptoms in study sample by clusters

| DE symptoms, High Ocular Pain* (N=49) |

DE symptoms, Low Ocular Pain* (N=104) |

No DE symptoms (N=34) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| ISI items, mean (SD) | |||

| Difficulty falling asleep | 2.0 (1.4)a | 1.7 (1.3)a | 1.0 (1.1) |

| Difficulty staying asleep | 2.3 (1.5)a,b | 1.9 (1.3)a | 1.3 (1.3) |

| Waking up too early | 2.1 (1.4)a,b | 1.5 (1.4) | 1.2 (1.5) |

| Sleep pattern satisfaction | 2.7 (1.3)a | 2.3 (1.3)a | 1.6 (1.2) |

| Interference with daily functioning | 2.5 (1.4)a,b | 1.8 (1.4)a | 0.8 (1.1) |

| Others notice sleeping problem | 2.2 (1.5)a,b | 1.4 (1.3)a | 0.7 (1.1) |

| Worried about sleep problem | 2.2 (1.5)a,b | 1.5 (1.4)a | 0.8 (1.2) |

| Total score (range 0–28) | 16.0 (8.4)a,b | 12.1 (8.0)a | 7.3 (7.3) |

| Insomnia (ISI≥ 15†, %) (n) | 30 (61%)a,b | 43 (41%)a | 6 (18%) |

ISI=Insomnia severity index; SD=standard deviation;

Symptoms of DE defined as DEQ5≥6; Ocular pain status defined by cluster analysis;

Significantly different (p<0.05) from no DE symptom group

Significantly different (p<0.05) from Low Ocular Pain group

Clinically significant insomnia symptoms

Figure 1.

Bar graph demonstrating higher mean insomnia scores in those with dry eye symptoms and High Ocular Pain as compared to those with dry eye symptoms and Low Ocular pain and those without dry eye symptoms (controls).

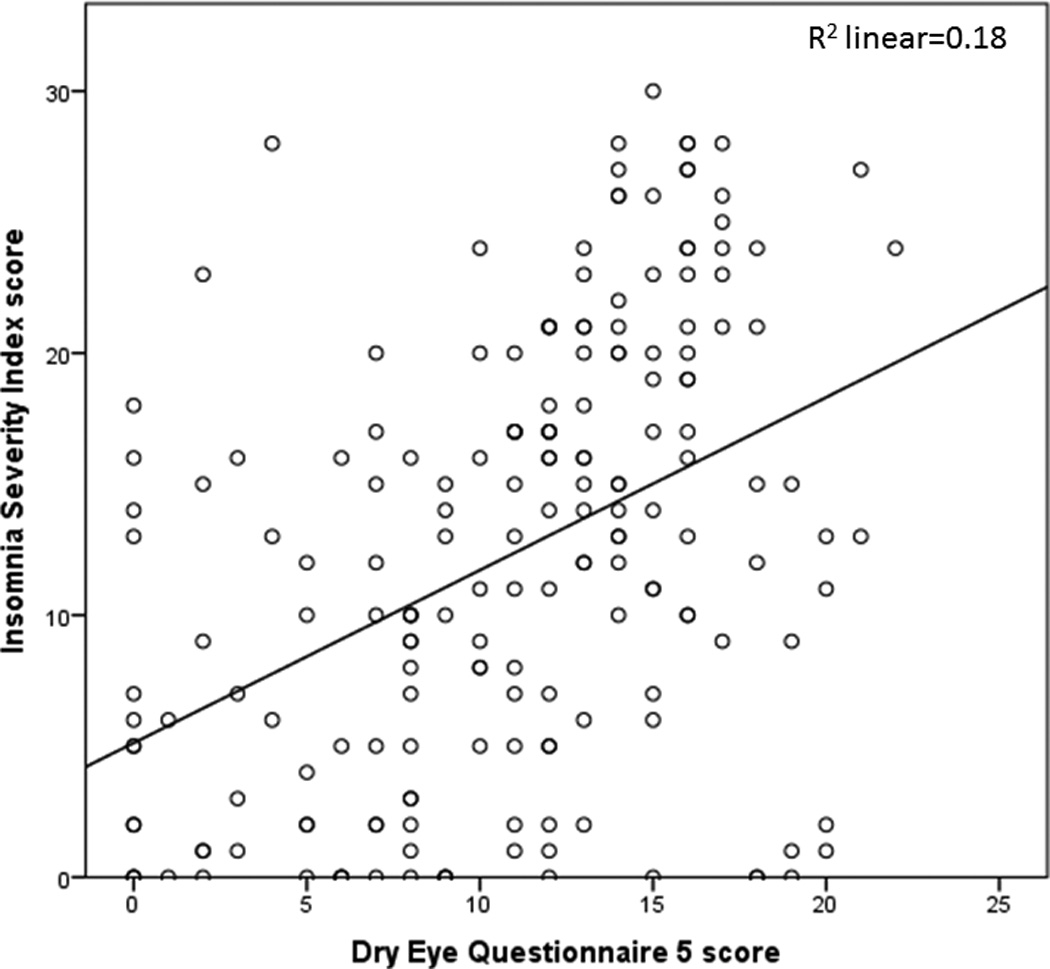

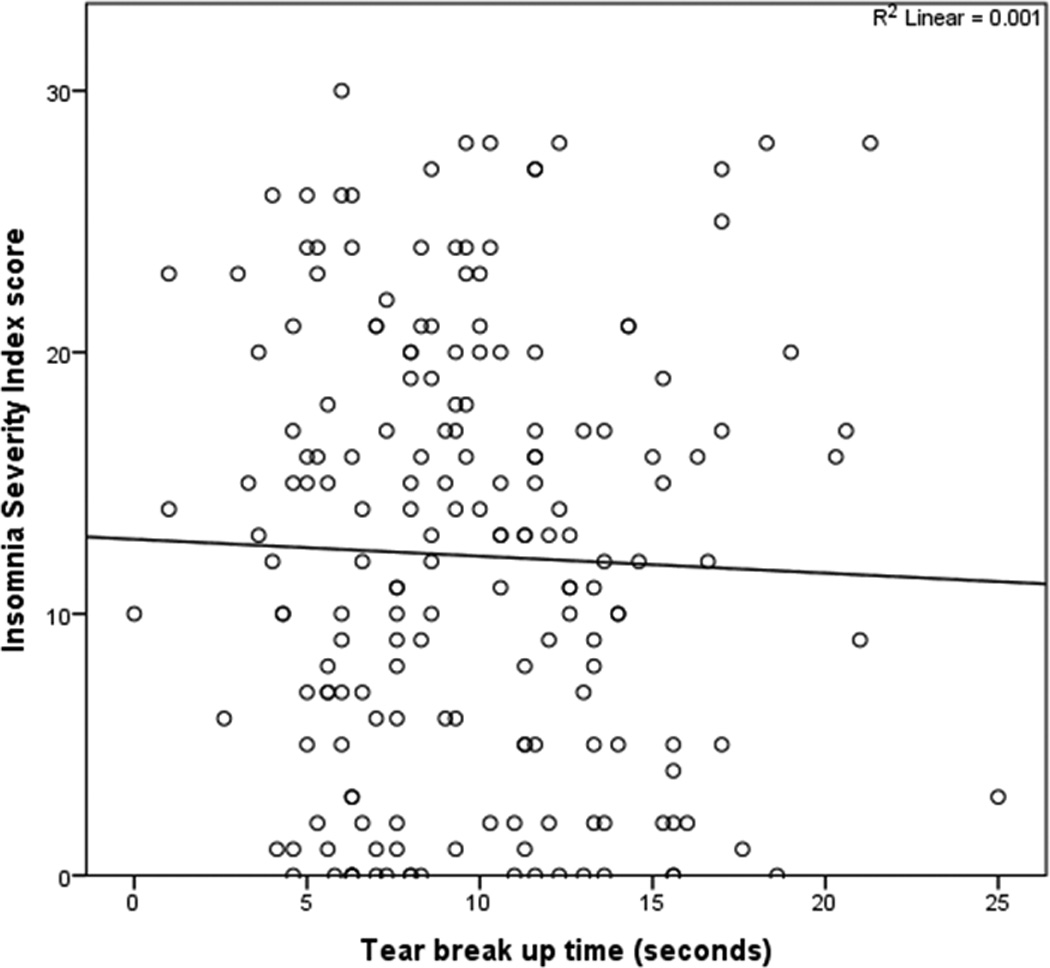

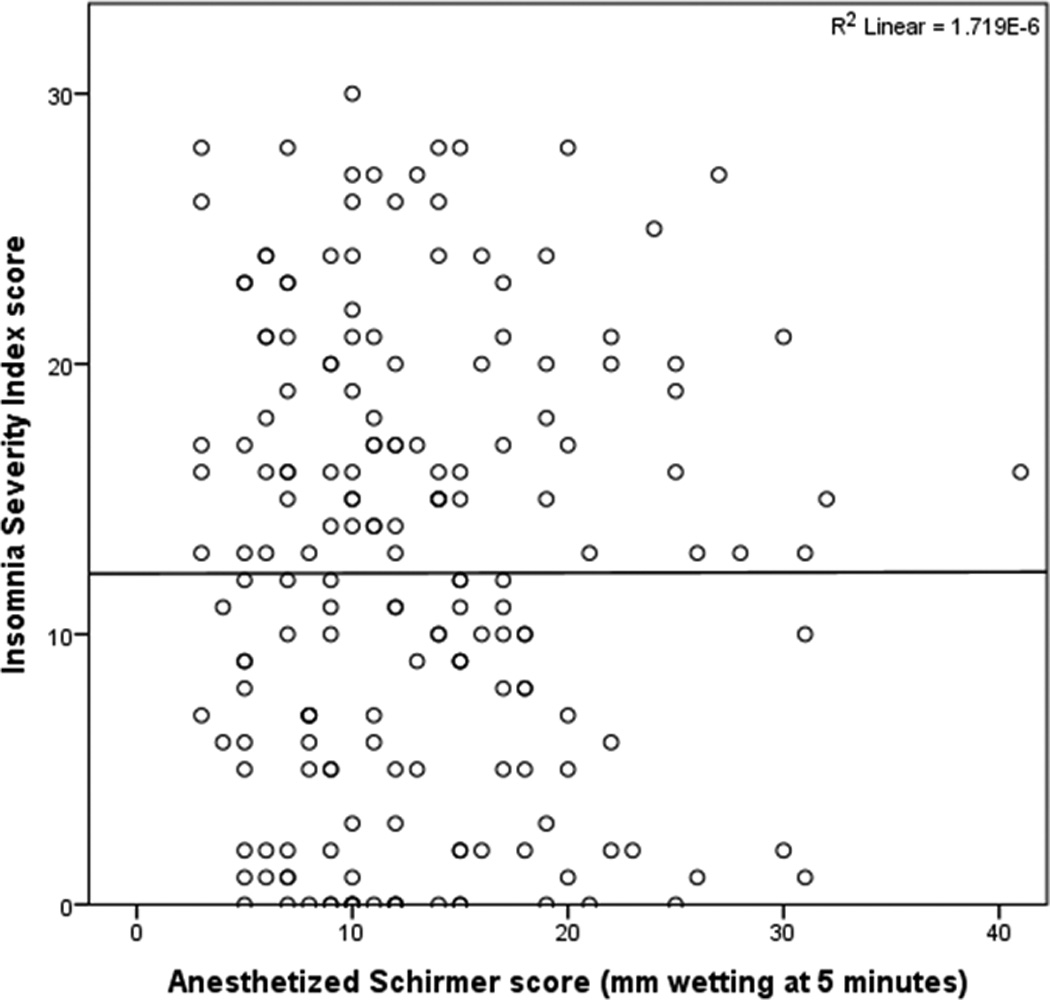

Correlations between insomnia and symptoms and signs of DE

All subjective metrics including “traditional” DE symptoms and ocular pain complaints were significantly and positively correlated with insomnia (ISI total score) (Figure 2). Most ocular surface findings, on the other hand, displayed no relationship to insomnia (Figures 3 and 4), with the exception of abnormal eyelid vascularity, which was found to associate with less insomnia (Table 3). To test the robustness of the relationship between DE symptoms and insomnia, we performed a forward stepwise logistic regression analysis that controlled for demographics (age, gender, race), medication use (anti-depressants, anxiolytics, analgesics), mental health (depression, PTSD, anxiety), medical co-morbidities (Charlson index, OSA), and ocular surface signs. When controlling for these co-morbidities, black race (odds ratio (OR) 2.7, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.2–6.0, p=0.02), depression severity (PHQ9, OR=1.2, 95% CI 1.1–1.3, p<0.0005), and DE severity (DEQ5, OR 1.1, 95% CI 1.01–1.2, p=0.03), remained significantly associated with clinical insomnia (ISI≥15).

Figure 2.

Scatter plot demonstrating the positive relationship between dry eye symptoms (dry eye questionnaire 5 score) and insomnia (Insomnia Severity Index score).

Figure 3.

Scatter plot demonstrating no relationship between tear break up time and insomnia (Insomnia Severity Index score).

Figure 4.

Scatter plot demonstrating no relationship between tear production (Schirmers score) and insomnia (Insomnia Severity Index score).

Table 3.

Correlations between insomnia (ISI) and dry eye symptoms and ocular surface findings in this study sample

| Pearson r | Spearman rho | |

|---|---|---|

| ISI and Ocular Symptoms | ||

| DEQ5 (range 0–22) | 0.43* | 0.45* |

| OSDI (range 0–100) | 0.46* | 0.48* |

| Ocular pain intensity, averaged over past week (range 0–10) |

0.39* | 0.41* |

| Hot burning pain (0–10) | 0.22* | 0.28* |

| Sensitivity to wind (0–10) | 0.31* | 0.32* |

| Sensitivity to light (0–10) | 0.36* | 0.40* |

| ISI and Ocular Surface Findings | ||

| Tear osmolarity, mOsm/L | 0.09 | 0.03 |

| Tear film breakup time, seconds | −0.03 | −0.03 |

| Corneal staining, (0–15) | −0.07 | −0.12 |

| Schirmer’s test, mm of moisture | 0.001 | −0.02 |

| Eyelid vascularity, (0–3) | −0.21* | −0.20* |

| Meibum quality, (0–4) | −0.13 | −0.12 |

DEQ5=Dry Eye Questionnaire; OSDI=Ocular Surface Disease Index questionnaire

All numbers represent the more severe value in either eye

p<0.01

Discussion

To conclude, we found that both DE symptoms and ocular pain complaints were positively correlated with insomnia. Our data are in accordance with those of Ayaki et al21 who reported that DE severity correlated with the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index35, an instrument which primarily measures insomnia. Similar to this study where more than half of their eye clinic sample reported poor sleep quality, more than 60% of our patients with DE and ocular pain fulfilled insomnia syndrome criteria. Our data extends prior findings by adjusting not only for demographic and ophthalmologic factors but also for important medical and mental health comorbidities in a novel sample of US military veterans.

We chose the ISI as our metric for insomnia to allow comparisons with other chronic pain populations. For example, our finding that 61% of individuals with HOP had clinically significant insomnia is similar in proportion to that found in other chronic pain groups, including a musculoskeletal pain population36 and a Veterans Affairs Medical Center Poly-trauma Clinic37 (~70% ISI scores ≥15). In a similar manner, our correlation coefficient of 0.39 between average ocular pain intensity and insomnia is similar to that reported between pain and insomnia in other populations including those with depression (0.24–0.30)38, chronic neck pain (0.35)39, and chronic back pain (0.26).40

Our noted association between DE and insomnia has many potential explanations. First, it is possible that DE symptoms and ocular pain may precipitate insomnia. As individuals predisposed to insomnia can have excessive preoccupation with events surrounding sleep and heightened cognitive responses to stressful situations41, nocturnal eye discomfort may be more distressful and prominent among these individuals than among healthy sleepers.21 Thus, as has been demonstrated in other pain conditions42, eye discomfort and its associated psychological distress43 may interfere with sleep initiation. After the acute onset of insomnia, patients may develop maladaptive behavioral strategies (i.e. daytime napping, spending excessive amounts of time in bed) and dysfunctional sleep beliefs in an attempt to cope with sleep difficulties.44 Over time, insomnia can become entrenched by these psychological and behavioral changes and becomes more challenging to reverse.45 In relation to DE, patients with newly diagnosed DE were found to have greater improvement in sleep after initiation of topical DE therapy compared to those with long standing DE22, the latter of which may have had more chronically entrenched insomnia.

Second, it is possible that insomnia leads to changes in tear physiology and DE symptoms. Studies have found that tear physiology differs during sleep (when the eye is closed) and waking (when the eye is blinking).46 During sleep, changes in lacrimation (slower, constitutive secretion), protein composition (mostly secretory Immunoglobulin A), and inflammation (build-up and activation of complement and proinflammatory soluble and cellular mediators) have been described. Insomnia likely has an effect on the tear physiology as sleep deprivation in healthy individuals has been associated with reduced tear secretion and tear hyperosmolarity.47 In animal models, parasympathetic tone decreases in sleep disruption, which could contribute to decreased nocturnal tear production via lower lacrimal gland activity.48 Thus, individuals with insomnia with recurrent nocturnal arousals and/or curtailed sleep may exhibit a change in their tear film physiology with resultant eye irritation and dryness.

Yet a third possibility is that the association between DE and insomnia may be indirect and driven by underlying factors, such as shared psychological profiles, genetic susceptibility, and/or somatosensory dysfunction. Regarding psychological profiles, insomnia and DE are both highly comorbid with depression and anxiety symptoms.17,41,45,49 Genetic polymorphisms, such as in pro-inflammatory genes, may underlie the associations between DE, insomnia, and depression.50,51 Interestingly, pro-inflammatory gene polymorphisms in IL1beta and IL6 receptor have been associated with DE symptoms in a Korean population.52 Such polymorphisms may underlie pathologic elevation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL6) and IL1b, that have been found in the tears of DE patients and blood of patients suffering with depression and insomnia.53–57 Pro-inflammatory cytokines can mediate pain syndromes and insomnia via numerous mechanisms including increased spontaneous firing of neurons58, enhanced excitatory neurotransmission through neural-glial interactions, and phenotypic alterations of primary afferents.59

Directionality between sleep and pain has been studied in other models. While this relationship was initially described as reciprocal and bidirectional, recent longitudinal studies suggest that sleeping disturbances are a stronger predictor of pain than pain of sleeping disturbances.60 For example, in a study of polyarticular arthritis, daily reports of poor sleep quality predicted daily pain, but the reverse association was not significant.61 Self-reported and experimental sleep continuity disturbances in fibromyalgia, rheumatoid arthritis, and temporomandibular disorder have all been associated with diminished conditioned pain modulation, a measure of endogenous opioid-mediated pain inhibition.62–64 Thus, this suggests that insomnia may promote pain entrenchment by impairment in the descending pain modulatory systems.

As with all studies, our study has limitations, which must be considered when interpreting the study results. First, our cross-sectional design precludes the determination of whether insomnia preceded or followed the onset of subjective DE symptoms. Second, the current study sample consisted of United States veterans, the majority of whom are older males. Although this provides contrast to several other studies examining female DE patients8,65 and the Asian studies examining DE and sleep21–23, its results may not be generalized to other populations. Third, all our measurements were obtained using specific scales and techniques. We chose the ISI because it is a well validated instrument used in community based and clinical samples.33,66,67 Fourth, many factors can underlie insomnia and it is impossible to control for all potential confounders, including co-morbidities (depression, PTSD)), medications, and the complex interaction between dry eye signs and symptoms. Finally, our diagnosis of OSA was self-reported and not verified with a sleep study. The presence of OSA may be a confounder for the noted association between DE symptoms and insomnia.68

Despite these limitations, this study is important as it highlights that patients with DE symptoms may have co-morbidities, such as insomnia, that need to be evaluated and addressed using a multidisciplinary approach. It is not yet known however whether improvement in DE symptoms will improve systemic parameters or, conversely, if treatment of non-ocular pain, depression, anxiety and disturbed sleep will in turn improve DE symptoms. This is an important avenue of future longitudinal studies.

Acknowledgments

We would like to note that the contents of this study do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Funding: Supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Clinical Sciences Research EPID-006-15S (Dr. Galor), NIH Center Core Grant P30EY014801, Research to Prevent Blindness Unrestricted Grant, NIH NIDCR RO1 DE022903 (Dr. Levitt), and the Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative Medicine, and Pain Management, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, FL.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None

References

- 1.The epidemiology of dry eye disease: report of the Epidemiology Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye WorkShop (2007) The ocular surface. 2007;5:93–107. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70082-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The definition and classification of dry eye disease: report of the Definition and Classification Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye WorkShop (2007) The ocular surface. 2007;5:75–92. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pouyeh B, Viteri E, Feuer W, et al. Impact of ocular surface symptoms on quality of life in a United States veterans affairs population. American journal of ophthalmology. 2012;153:1061–1066. e1063. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenthal P, Borsook D. Ocular neuropathic pain. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2016;100:128–134. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-306280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galor A, Levitt RC, Felix ER, et al. Neuropathic ocular pain: an important yet underevaluated feature of dry eye. Eye. 2015;29:301–312. doi: 10.1038/eye.2014.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalangara JP, Galor A, Levitt RC, et al. Characteristics of Ocular Pain Complaints in Patients With Idiopathic Dry Eye Symptoms. Eye & contact lens. 2016 doi: 10.1097/ICL.0000000000000249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vehof J, Zavos HM, Lachance G, et al. Shared genetic factors underlie chronic pain syndromes. Pain. 2014;155:1562–1568. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vehof J, Kozareva D, Hysi PG, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of dry eye disease in a British female cohort. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2014;98:1712–1717. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-305201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vehof J, Sillevis Smitt-Kamminga N, Kozareva D, et al. Clinical Characteristics of Dry Eye Patients With Chronic Pain Syndromes. American journal of ophthalmology. 2016;162:59–65. e52. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2015.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galor A, Covington D, Levitt AE, et al. Neuropathic Ocular Pain due to Dry Eye Is Associated With Multiple Comorbid Chronic Pain Syndromes. The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society. 2016;17:310–318. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yunus MB. Editorial review: an update on central sensitivity syndromes and the issues of nosology and psychobiology. Current rheumatology reviews. 2015;11:70–85. doi: 10.2174/157339711102150702112236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Munzenmaier DH, Wilentz J, Cowley AW., Jr Genetic, epigenetic, and mechanistic studies of temporomandibular disorders and overlapping pain conditions. Molecular pain. 2014;10:72. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-10-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aaron LA, Burke MM, Buchwald D. Overlapping conditions among patients with chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, and temporomandibular disorder. Archives of internal medicine. 2000;160:221–227. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finan PH, Smith MT. The comorbidity of insomnia, chronic pain, and depression: Dopamine as a putative mechanism. Sleep medicine reviews. 2013;17:173–183. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wasner G. Central pain syndromes. Current pain and headache reports. 2010;14:489–496. doi: 10.1007/s11916-010-0140-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galor A, Felix ER, Feuer W, et al. Dry eye symptoms align more closely to non-ocular conditions than to tear film parameters. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2015;99:1126–1129. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-306481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fernandez CA, Galor A, Arheart KL, et al. Dry eye syndrome, posttraumatic stress disorder, and depression in an older male veteran population. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2013;54:3666–3672. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-11635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Labbe A, Wang YX, Jie Y, et al. Dry eye disease, dry eye symptoms and depression: the Beijing Eye Study. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2013;97:1399–1403. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2013-303838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li M, Gong L, Sun X, et al. Anxiety and depression in patients with dry eye syndrome. Current eye research. 2011;36:1–7. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2010.519850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wen W, Wu Y, Chen Y, et al. Dry eye disease in patients with depressive and anxiety disorders in Shanghai. Cornea. 2012;31:686–692. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3182261590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ayaki M, Kawashima M, Negishi K, et al. Sleep and mood disorders in dry eye disease and allied irritating ocular diseases. Scientific reports. 2016;6:22480. doi: 10.1038/srep22480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ayaki M, Toda I, Tachi N, et al. Preliminary report of improved sleep quality in patients with dry eye disease after initiation of topical therapy. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment. 2016;12:329–337. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S94648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee W, Lim SS, Won JU, et al. The association between sleep duration and dry eye syndrome among Korean adults. Sleep medicine. 2015;16:1327–1331. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2015.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. Journal of chronic diseases. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gilbody S, Richards D, Brealey S, et al. Screening for depression in medical settings with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ): a diagnostic meta-analysis. Journal of general internal medicine. 2007;22:1596–1602. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0333-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilkins KC, Lang AJ, Norman SB. Synthesis of the psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist (PCL) military, civilian, and specific versions. Depression and anxiety. 2011;28:596–606. doi: 10.1002/da.20837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Derogatis LR, Rickels K, Rock AF. The SCL-90 and the MMPI: a step in the validation of a new self-report scale. The British journal of psychiatry : the journal of mental science. 1976;128:280–289. doi: 10.1192/bjp.128.3.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chalmers RL, Begley CG, Caffery B. Validation of the 5-Item Dry Eye Questionnaire (DEQ-5): Discrimination across self-assessed severity and aqueous tear deficient dry eye diagnoses. Contact lens & anterior eye : the journal of the British Contact Lens Association. 2010;33:55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2009.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schiffman RM, Christianson MD, Jacobsen G, et al. Reliability and validity of the Ocular Surface Disease Index. Archives of ophthalmology. 2000;118:615–621. doi: 10.1001/archopht.118.5.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Galor A, Zlotcavitch L, Walter SD, et al. Dry eye symptom severity and persistence are associated with symptoms of neuropathic pain. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2015;99:665–668. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-306057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spierer O, Felix ER, McClellan AL, et al. Corneal Mechanical Thresholds Negatively Associate With Dry Eye and Ocular Pain Symptoms. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2016;57:617–625. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-18133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Methodologies to diagnose and monitor dry eye disease: report of the Diagnostic Methodology Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye WorkShop (2007) The ocular surface. 2007;5:108–152. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70083-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bastien CH, Vallieres A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep medicine. 2001;2:297–307. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fernandez-Mendoza J, Vgontzas AN, Bixler EO, et al. Clinical and polysomnographic predictors of the natural history of poor sleep in the general population. Sleep. 2012;35:689–697. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Monk TH, et al. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry research. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Asih S, Neblett R, Mayer TG, et al. Insomnia in a chronic musculoskeletal pain with disability population is independent of pain and depression. The spine journal : official journal of the North American Spine Society. 2014;14:2000–2007. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2013.11.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lang KP, Veazey-Morris K, Andrasik F. Exploring the role of insomnia in the relation between PTSD and pain in veterans with polytrauma injuries. The Journal of head trauma rehabilitation. 2014;29:44–53. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0b013e31829c85d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chung KF, Tso KC. Relationship between insomnia and pain in major depressive disorder: A sleep diary and actigraphy study. Sleep medicine. 2010;11:752–758. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim SH, Lee DH, Yoon KB, et al. Factors Associated with Increased Risk for Clinical Insomnia in Patients with Chronic Neck Pain. Pain physician. 2015;18:593–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tang NK, Wright KJ, Salkovskis PM. Prevalence and correlates of clinical insomnia co-occurring with chronic back pain. Journal of sleep research. 2007;16:85–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2007.00571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Palagini L, Faraguna U, Mauri M, et al. Association between stress-related sleep reactivity and cognitive processes in insomnia disorder and insomnia subgroups: preliminary results. Sleep medicine. 2016;19:101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2015.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tang NK, Goodchild CE, Hester J, et al. Pain-related insomnia versus primary insomnia: a comparison study of sleep pattern, psychological characteristics, and cognitive-behavioral processes. The Clinical journal of pain. 2012;28:428–436. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31823711bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Galor A, Feuer W, Lee DJ, et al. Depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and dry eye syndrome: a study utilizing the national United States Veterans Affairs administrative database. American journal of ophthalmology. 2012;154:340–346. e342. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2012.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Levenson JC, Kay DB, Buysse DJ. The pathophysiology of insomnia. Chest. 2015;147:1179–1192. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Riemann D, Nissen C, Palagini L, et al. The neurobiology, investigation, and treatment of chronic insomnia. The Lancet. Neurology. 2015;14:547–558. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sack RA, Beaton A, Sathe S, et al. Towards a closed eye model of the pre-ocular tear layer. Progress in retinal and eye research. 2000;19:649–668. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(00)00006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee YB, Koh JW, Hyon JY, et al. Sleep deprivation reduces tear secretion and impairs the tear film. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2014;55:3525–3531. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-13881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.von Treuer K, Norman TR, Armstrong SM. Overnight human plasma melatonin, cortisol, prolactin, TSH, under conditions of normal sleep, sleep deprivation, and sleep recovery. Journal of pineal research. 1996;20:7–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079x.1996.tb00232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fernandez-Mendoza J, Vela-Bueno A, Vgontzas AN, et al. Cognitive-emotional hyperarousal as a premorbid characteristic of individuals vulnerable to insomnia. Psychosomatic medicine. 2010;72:397–403. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181d75319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Haddy N, Sass C, Maumus S, et al. Biological variations, genetic polymorphisms and familial resemblance of TNF-alpha and IL-6 concentrations: STANISLAS cohort. European journal of human genetics : EJHG. 2005;13:109–117. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gehrman PR, Keenan BT, Byrne EM, et al. Genetics of Sleep Disorders. The Psychiatric clinics of North America. 2015;38:667–681. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Na KS, Mok JW, Kim JY, et al. Proinflammatory gene polymorphisms are potentially associated with Korean non-Sjogren dry eye patients. Molecular vision. 2011;17:2818–2823. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McNally L, Bhagwagar Z, Hannestad J. Inflammation, glutamate, and glia in depression: a literature review. CNS Spectr. 2008;13:501–510. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900016734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Money KM, Olah Z, Korade Z, et al. An altered peripheral IL6 response in major depressive disorder. Neurobiology of disease. 2016;89:46–54. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2016.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Massingale ML, Li X, Vallabhajosyula M, et al. Analysis of inflammatory cytokines in the tears of dry eye patients. Cornea. 2009;28:1023–1027. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181a16578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Irwin MR, Olmstead R, Carroll JE. Sleep Disturbance, Sleep Duration, and Inflammation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies and Experimental Sleep Deprivation. Biological psychiatry. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hurtado-Alvarado G, Pavon L, Castillo-Garcia SA, et al. Sleep loss as a factor to induce cellular and molecular inflammatory variations. Clinical & developmental immunology. 2013;2013:801341. doi: 10.1155/2013/801341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Oh SB, Tran PB, Gillard SE, et al. Chemokines and glycoprotein120 produce pain hypersensitivity by directly exciting primary nociceptive neurons. J Neurosci. 2001;21:5027–5035. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-14-05027.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Eliav E, Herzberg U, Ruda MA, et al. Neuropathic pain from an experimental neuritis of the rat sciatic nerve. Pain. 1999;83:169–182. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00102-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Finan PH, Goodin BR, Smith MT. The association of sleep and pain: an update and a path forward. The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society. 2013;14:1539–1552. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bromberg MH, Gil KM, Schanberg LE. Daily sleep quality and mood as predictors of pain in children with juvenile polyarticular arthritis. Health psychology : official journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association. 2012;31:202–209. doi: 10.1037/a0025075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Edwards RR, Grace E, Peterson S, et al. Sleep continuity and architecture: associations with pain-inhibitory processes in patients with temporomandibular joint disorder. European journal of pain. 2009;13:1043–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lee YC, Nassikas NJ, Clauw DJ. The role of the central nervous system in the generation and maintenance of chronic pain in rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis and fibromyalgia. Arthritis research & therapy. 2011;13:211. doi: 10.1186/ar3306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Paul-Savoie E, Marchand S, Morin M, et al. Is the deficit in pain inhibition in fibromyalgia influenced by sleep impairments? The open rheumatology journal. 2012;6:296–302. doi: 10.2174/1874312901206010296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vehof J, Kozareva D, Hysi PG, et al. Relationship between dry eye symptoms and pain sensitivity. JAMA ophthalmology. 2013;131:1304–1308. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.4399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Morin CM, Belleville G, Belanger L, et al. The Insomnia Severity Index: psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep. 2011;34:601–608. doi: 10.1093/sleep/34.5.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wallace DM, Shafazand S, Aloia MS, et al. The association of age, insomnia, and self-efficacy with continuous positive airway pressure adherence in black, white, and Hispanic U.S. Veterans. Journal of clinical sleep medicine : JCSM : official publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. 2013;9:885–895. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.2988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ansari Z, Singh R, Alabiad C, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and morbidity of eye lid laxity in a veteran population. Cornea. 2015;34:32–36. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000000286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]