Abstract

The histidine kinase Hik33 plays important roles in mediating cyanobacterial response to divergent types of abiotic stresses including cold, salt, high light (HL), and osmotic stresses. However, how these functions are regulated by Hik33 remains to be addressed. Using a hik33-deficient strain (Δhik33) of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (Synechocystis) and quantitative proteomics, we found that Hik33 depletion induces differential protein expression highly like that induced by divergent types of stresses. This typically includes downregulation of proteins in photosynthesis and carbon assimilation that are necessary for cell propagation, and upregulation of heat shock proteins, chaperons, and proteases that are important for cell survival. This observation indicates that depletion of Hik33 alone mimics divergent types of abiotic stresses, and that Hik33 could be important for preventing abnormal stress response in the normal condition. Moreover, we found most proteins of plasmid origin were significantly upregulated in Δhik33, though their biological significance remains to be addressed. Together, the systematically characterized Hik33-regulated cyanobacterial proteome, which is largely involved in stress responses, builds the molecular basis for Hik33 as a general regulator of stress responses.

Cyanobacteria are a group of photosynthetic Gram-negative bacteria that play an important role in shaping the current living condition of the biosphere by contributing a significant fraction of oxygen in the atmosphere (1–3). Cyanobacteria are widely distributed in almost every terrestrial and aquatic habitat, and thus have developed an efficient system to cope with versatile and ever-changing adverse environmental conditions during the long evolutional process. Understanding the mechanism how cyanobacteria adapt to such divergent environmental stresses is important for better utilizing these organisms with great potential in producing clean and renewable biofuels (4–7).

The most frequently occurring environment stresses cyanobacteria must cope with in their natural habitats include high light (HL)1 irradiation, high or low temperature, high salt, acid, and drought. In the past two decades, application of genomics and proteomics approaches have accelerated the investigations of the cyanobacterial stress responses at a system level. One of the most prominent findings of such investigations is that different types of stresses can induce a common response in terms of gene expression (8–11), though some stress-type specific responses were also observed. For example, expression of heat shock proteins, chaperons, and some proteases is usually dramatically upregulated in response to HL, salt, or cold stresses, whereas the expression of proteins in photosystem I (PS I) and phycobilisome (PBS) are usually significantly repressed in the same conditions. Though it is believed that such responses are important for protecting cyanobacteria from the stresses-induced damages, unfortunately, how different stresses induce the same response in protein expression is far from addressed.

Like the other prokaryotes, cyanobacteria perceive and transduce environmental signals through the two-component systems, which are usually composed of a histidine kinase (Hik) acting as the sensor and a cognate response regulator (Rre). Upon perceiving the environment signals, the Hik is activated through autophosphorylation of one of its histidine residues, and then transfer the phosphor-group to an aspartate residue of its cognate Rre. The phosphorylated Rre in turn regulates expression of genes, by acting as a transcription factor or some undefined mechanism, that are necessary for adapting to the environmental changes (12). Cyanobacterial genomes usually encode large families of Hiks and Rres to cope with versatile environmental stresses in their divergent natural habitats (12). Multiple Hik-Rre systems may be required to cope with a particular type of stress, but the degree of their involvement could be different. On the other hand, a single Hik may be involved in sensing and transducing multiple types of environmental stresses, such as Hik33.

Hik33 is highly conserved in cyanobacteria but not in other prokaryotes, suggesting that the functions of Hik33 are specialized to coordinate photosynthesis and stress response. Hik33 was originally named as the drug sensory protein A (DspA) because a knockout mutant of hik33 is more resistant to herbicides (13). Screening of cyanobacterial mutants defective in cold response revealed that hik33 mutation repressed the cold-induced upregulation of several cold-responsive genes (14), and for the first time, implicated Hik33 in stress response. Later, Hik33 was implicated in additional types of stress responses, such as HL irradiation, hyperosmotic stress, salt, and acid (15–18). Thus, it is conceivable to presume that Hik33 plays a general but critical role in regulating differential gene expression in response to divergent types of stresses. Unfortunately, despite the tremendous amount of attempts in elucidating the working mechanism of Hik33, how Hik33 perceives the divergent environmental signals and regulates the corresponding cellular response in cyanobacteria remain largely unknown. Characterization of Hik33-dependent differential gene expression can provide important information for the understanding how Hik33 operates in stress response. Nevertheless, such information is only available at transcription level and limited to only a single stress condition in each study (19). Because transcription levels are usually not well correlated with the protein levels (20), and because Hik33 operates in multiple types of stress responses, such transcription information without enough generality is still not sufficient for elucidating the working mechanism of Hik33 in regulating stress responses.

Herein, we tried to investigate the causal relationship of Hik33 and the common stress response in proteome expression using the unicellular model organism Synechocystis by taking its unique advantages. First, Synechocystis is the first cyanobacterium with the completely sequenced and best annotated genome (21), which contains 3672 protein-coding open reading frames (ORFs). The relatively small size of the genome can significantly reduce the complexity of large scale genomic or proteomic analyses. Second, Synechocystis is naturally transformable, which allows utilization of reverse genetics approaches to study the functional significance of stress-related proteins. Finally, Synechocystis highly resembles the chloroplast in higher plants, as such the protective mechanism for photosynthetic machineries in environment stress uncovered for Synechocystis could also be applied for higher plants.

Using a previously established hik33 mutant strain of Synechocystis and a quantitative proteomics approach (15), we compared the Hik33-regulated proteome with the previously described stress-responsive genes and/or proteins, and demonstrated that Hik33 plays a central role in regulating the expression of proteins that are common in divergent types of stress-responses.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Antibodies and Cell Culture

All primary antibodies were purchased from Agrisera (Vännäs, Sweden). The wild type (WT) strain of Synechocystis and the Δhik33 were cultured in liquid BG-11 medium in moderate light (50 μmol/m2s photons) in a shaker or bubbled with air as necessary. The cells were collected by centrifugation (4000 × g for 10 min) for biochemical and proteomic analyses when the culture reaches the optical density at 730 nm of about 1.0. The optical density measures the turbidity of the cell culture (22), which positively correlates with cell density and can be used to compare the concentrations of cells in different cultures if the average sizes of the cells being compared are equal. The harvested cells were stored at −80 °C until they were used for protein preparation.

Pigment Analysis

The Chl and total carotenoids in cells were extracted with N, N-dimethylformamide (DMF, Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO), and the concentrations were determined using a previously described approach (23). The equations used for the calculation of pigment concentration are:

Preparation of PS I Trimers

Thylakoid membranes were prepared through differential centrifugation as previously described (24, 25). The PS I trimers were prepared by sucrose-gradient centrifugation using a well-established protocol (26, 27). Briefly, the thylakoid membranes containing 2 mg/ml protein were added with n-dodecyl β-d-maltoside (DM, Sigma-Aldrich) to a final concentration 1.5%, and then allowed to solubilize at 4 °C for 30 min. The solubilized membranes were loaded on the top of a 10% to 30% (w/w) step sucrose gradient and centrifuged with 160,000 × g for 16 h at 4 °C. The fractions containing PS I trimers were collected and stored at −80 °C until use.

Protein Preparation

Cell pellets were lysed in a buffer containing 0.4 m sucrose, 50 mm 3-(N-morpholino) propanesulfonic acid, pH 7.0, 10 mm NaCl, 5 mm EDTA, and 0.5 mm phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF, Sigma-Aldrich) with a bead beater. The WCLs were centrifuged for 30 min at 5000 × g at 4 °C to remove insoluble debris. After precipitation with ice-cold 10% trichloroacetic acid in acetone at −20 °C, total proteins were washed with acetone and resolubilized with 4% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) in 0.1 m Tris-HCl, pH 7.6. A BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) was used to determine the protein concentration.

Protein Digestion and Tandem Mass Tag (TMT) Labeling

Proteins were digested using the filter-aided sample preparation (FASP) method according to a previously described method with slight modifications (28). Briefly, the lysates (100 μg protein for each sample) were reduced with 10 mm DTT at 37 °C for 1 h and alkylated with 55 mm iodoacetamide (IAA, Sigma-Aldrich) at room temperature for 1 h in the dark. The alkylated lysates were transferred into the Microcon YM-30 centrifugal filter units (EMD Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA), where the denaturing buffer was replaced by the 0.1 m triethylammonium bicarbonate (TEAB, Sigma-Aldrich), and then digested with sequencing grade trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI) at 37 °C overnight. The resulting tryptic peptides from three biological replicates of the WT and Δhik33 were collected and labeled with 6-plex TMT reagents (Thermo Scientific) by incubating peptides with ethanol-dissolved TMT reagents for 2 h at room temperature in dark. The labeling reaction was inactivated by addition of 5% hydroxylamine, and the labeled samples were mixed together with equal ratios before fractionated with reversed phase (RP)-high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).

RP-HPLC

Offline basic RP-HPLC was performed using a Waters e2695 separations HPLC system coupled with a phenomenex gemini-NX 5u C18 column (250 × 3.0 mm, 110 Å) (Torrance, CA). The sample was separated with a 97-min basic RP-LC gradient as previously described (29). A flow rate of 0.4 ml/min was used for the entire LC separation. The separated samples were collected into 15 fractions, and completely dried with a SpeedVac concentrator and stored at −20 °C for further analysis.

Mass Spectrometry

For MS analysis, the peptides were resuspended in 0.1% formic acid (FA) and analyzed by a LTQ Orbitrap Elite mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific) coupled online to an Easy-nLC 1000 in the data-dependent mode. Briefly, 2 μl of peptide sample (1 μg/μl) was injected into a 15-cm-long, 75-μm inner diameter capillary analytic column packed with C18 particles of 5-μm diameter. The mobile phases for the LC include buffer A (2% acetonitrile, 0.1% FA) and buffer B (98% acetonitrile, 0.1% FA). The peptides were separated using a 90-min nonlinear gradient consisting of 3–8% B for 10 min, 8–20% B for 60 min, 20–30% B for 8 min, 30–100% B for 2 min, and 100% B for 10 min at a flow rate of 300 nl/min. The source voltage and current were set at 2.5 KV and 100 μA, respectively. All MS measurements were performed in the positive ion mode and acquired across the mass range of 300–1800 m/z. The fifteen most intense ions from each MS scan were isolated and fragmented by high-energy collisional dissociation.

Data Analysis

Raw mass spectrometric files were analyzed using the software MaxQuant (version 1.5.3.28) (30). The database search was performed using the integrated searching engine Andromeda, and the proteome sequence database used was downloaded from CyanoBase that contains 3672 protein entries concatenated with 248 common contaminations (ftp://ftp.kazusa.or.jp/pub/CyanoBase/Synechocystis, released on 5/11/2009). The type of search was set to report ion MS2 and the 6-plex TMT was chosen for isobaric labels, and the minimum reporter parent ion interference (PIF) was set to 0.75. Trypsin was chosen as the protease for protein digestion, and the maximum of 2 was set as the allowable miscleavages. N-terminal acetylation and methionine oxidation were included as the variable modification. Cysteine carbamidomethylation was included as the fix modification. The mass tolerances were set to 4.5 ppm for the main search and 20 ppm for precursor and fragment ions. The minimum score for unmodified peptides and modified peptides were set to 15 and 40, respectively. Other parameters were set up using the default values. The false discovery rate (FDR) was set to 0.01 for both peptide and protein identifications.

Experimental Design and Statistical Rationale

For the quantitative proteomic analysis, tryptic peptides from three biological replicates of the WT (control) and Δhik33 were labeled with 6-plex TMT reagents in an alternating order as shown in Fig. 1C to reduce quantitative bias resulting from the TMT reagents. The labeled peptides were mixed together with an equal molar ratio and separated into 15 fractions by RP-HPLC before LC-MS/MS analysis.

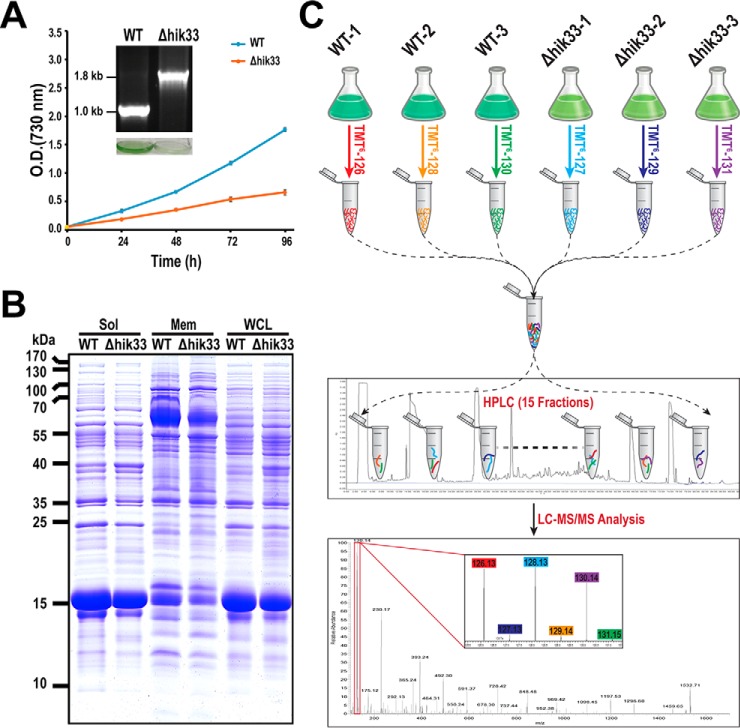

Fig. 1.

Rationale and experimental design. A, Confirmation of Δhik33 growth phenotype under photoautotrophic condition. The deletion of hik33 was confirmed by PCR as previously described and shown in the inset (106), which also contains the photo of the cell culture. B, The WCLs of the WT and Δhik33 strains of Synechocystis were separated into the membrane (Mem) and the soluble (Sol) fractions. Proteins extracted from either fraction and the WCL were subsequently separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized with Coomassie blue staining. C, Schematic representation of the workflow for the quantitative analysis of the Δhik33 proteome. Total proteins were extracted from the WCLs of three biological replicates of the WT and Δhik33 and digested with trypsin. The tryptic peptides were labeled with 6-plex TMT reagents in the order as indicated. The labeled peptides were mixed together with an equal molar ratio, and separated into 15 fractions with RP-HPLC. The peptides in each fraction were quantitatively analyzed by LC-MS/MS using a LTQ-Orbitrap-Elite mass spectrometer.

Bioinformatic and statistical analyses were mainly performed using the software Perseus (version 1.5.5.3) (31). Student's t test was used to determine the significance of differential expression of proteins between the WT and Δhik33, and Fisher's-exact test was used for the functional enrichment analysis. A p value<0.05 was used as the cut-off for all statistical analyses.

RESULTS

Depletion of Hik33 Resulted in Differential Protein Expression in Synechocystis

The Δhik33 mutant was firstly confirmed for the complete depletion of hik33 and the repressed photoautotrophic growth (15) (Fig. 1A). Proteins extracted from the whole cell lysate (WCL), the membrane fraction, and the soluble fraction from both the WT and the mutant strains of Synechocystis were separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized with Coomassie blue staining. The result indicates that the overall protein profiles of the three extractions are apparently different between the two strains (Fig. 1B), which warrants large scale quantitative proteomics analysis for the identification of the differentially expressed proteins.

The overall strategy for the quantitative comparison of the proteomes between the WT and the mutant is illustrated by the diagram (Fig. 1C). An isobaric-labeling approach using TMT reagents was used for the quantitative mass spectrometry as previously described (32). Total proteins extracted from the WCL of three biological replicates of both strains were included for the analysis. Note that we did not separate proteins into membrane and soluble fractions for the quantitative proteomic analysis for the reasons as outlined: Many proteins in Synechocystis, and probably in other cyanobacteria as well, localize both on membranes and in soluble compartments as we described before (33). A protein could be quantified as upregulated in the membrane fraction and downregulated in the soluble fraction or vice versa. This makes it difficult to determine whether the total level of the protein is upregulated, downregulated, or unchanged. Therefore, we prefer to quantitatively analyze the whole proteome instead of the subfractions for more conclusive results.

Quantitative Identification of Differentially Expressed Proteins

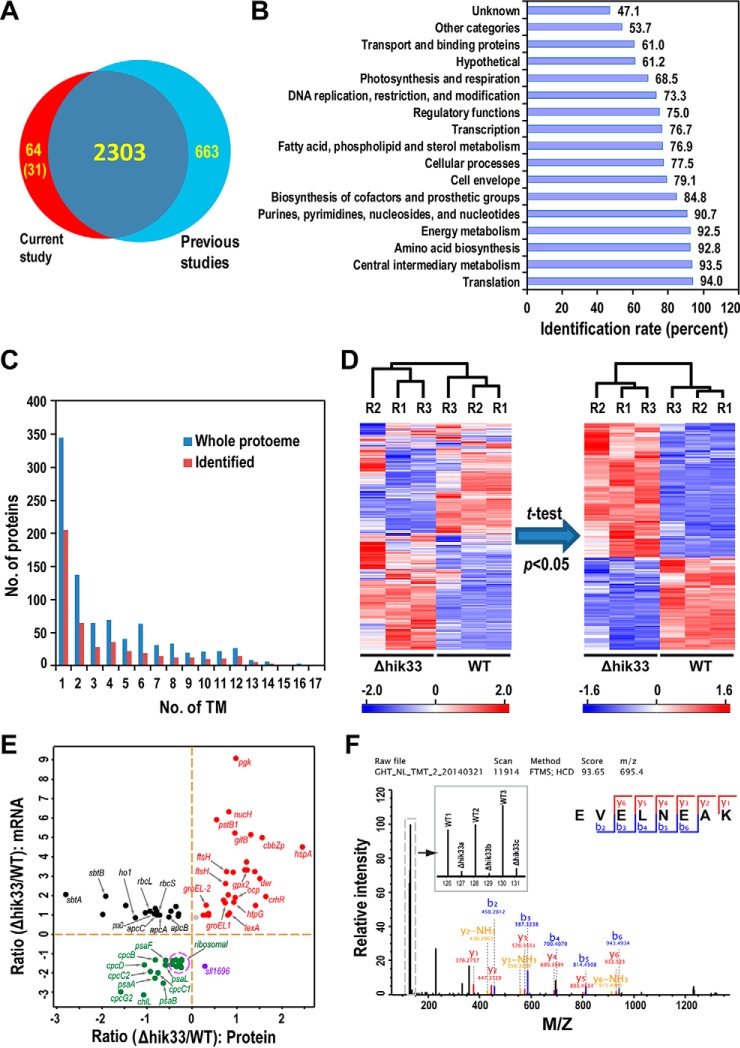

The TMT-labeled peptides were analyzed with a LTQ-Orbitrap-Elite mass spectrometer and 2367 proteins or protein groups, which constitute about 65% of the Synechocystis proteome, were identified with a FDR 1% (supplemental Table S1). Comparing these proteins with a combined list of proteins identified from more than 50 previous studies reveals that 2303 proteins are overlapping and 64 proteins are unique to the current study (Fig. 2A) (34). Identification of these new proteins is probably because of the Hik33 depletion-induced expression of low abundance proteins, which are otherwise undetectable by MS. We did not exclude proteins identified with a single peptide because many functionally important proteins in Synechocystis are small proteins with only one identifiable tryptic peptide (34). Annotated spectra of proteins with single-peptide identification are shown in supplemental Fig. S1.

Fig. 2.

Quantitative identification of Δhik33 proteome. A, Venn diagram showing the number of Synechocystis proteins identified in the current study and the combined number in all previous studies (34). B, Bar graph showing the coverage of protein identification for all functional categories annotated by the CyanoBase. The numbers to the right of the bars are the identification rates (percent). C, Bar graph showing the distribution of the number of identified proteins with increasing number of predicted TM (Identified), the distribution of all TM-containing proteins encoded by the whole Synechocystis genome is also shown (Whole proteome). D, Hierarchy clustering of the z-scored TMT report ion intensities were used to evaluate the reproducibility of the proteome quantitation. 2,058 proteins with valid TMT report ion intensity information in all six channels were included for the analysis (Left panel). Student's t test was used to filter proteins quantified with high confidence (p < 0.05) (Right panel). The extents of differential expression of proteins are color-coded and shown by the scale bars. E, Scatter plot showing the comparison of the differential gene expression in Δhik33 measured by the current proteomic study and a previous transcriptomic study (19). The x axis denotes the fold changes of proteins in the current study (Δhik33/WT), the y axis denotes the fold changes of mRNAs. F, A representative mass spectrum for a peptide from Hik33 shows the reproducibility and the high confidence of the quantitation. The region containing TMT report ions was horizontally zoomed-in and displayed in the inset. The weak TMT-signals in the Δhik33 channels were resulted from precursor ion interference.

Grouping the identified proteins according to the functional categories annotated by the CyanoBase revealed that the coverages of identification for all functional categories are higher than 50% except for the category unknown (Fig. 2B) (35), which presumably contains mainly undetectable low abundance proteins (33, 34). Moreover, 457 identified proteins contain one or more transmembrane domains (TM) predicted by the software TMHMM, which is more than 50% of TM-containing proteins encoded by the whole Synechocystis genome (Fig. 2C). Such a high coverage is critical for the identification of the differentially expressed membrane proteins displayed by the Coomassie-blue staining (Fig. 1B). Together, the high coverage identification ensures the comprehensiveness of the ensuing quantitative proteomics and bioinformatic analyses toward unraveling the mechanism of Hik33 in mediating divergent stress responses.

Quantitation was performed using normalized TMT report ion intensities for 2058 proteins containing quantitative TMT information in all replicates (supplemental Table S2) (32). Hierarchical clustering analysis using the z-scored report ion intensities reveals that the three biological replicates of the WT and the mutant are correctly clustered together (Fig. 2D), indicative of high reproducibility of the quantitation. Student's t test with a threshold p < 0.05 filters the protein list from 2058 to 994 to include only proteins quantified with high confidence (Fig. 2D). The fold changes of most the proteins are positively correlated with respective fold changes of mRNAs previously measured (Fig. 2E) (19). Negative correlations were also observed for a few proteins, which can be ascribed to the fact that, in addition to the well accepted concept that protein and mRNA levels are usually not well correlated (20), the experimental condition in the present study may not be the same as that in the previous study. The high confidence of quantitation is further demonstrated by an extracted mass spectrum of a peptide from Hik33 (Fig. 2F), in which the intensities of the TMT report ions are much higher in all channels for the WT compared with those for Δhik33. Note that the signals in the mutant channels are weak but not completely disappeared (Fig. 2F). This is because of the well-known precursor ion interference effect that usually causes compressed ratio of quantitation in isobaric labeling-based quantitative proteomics approach (36). Taking this in consideration, we chose a fold change 1.4 instead of a higher one to further filter for proteins expressed with significant difference between the two strains, which resulted in 369 and 208 proteins upregulated and downregulated in Δhik33, respectively (supplemental Table S2).

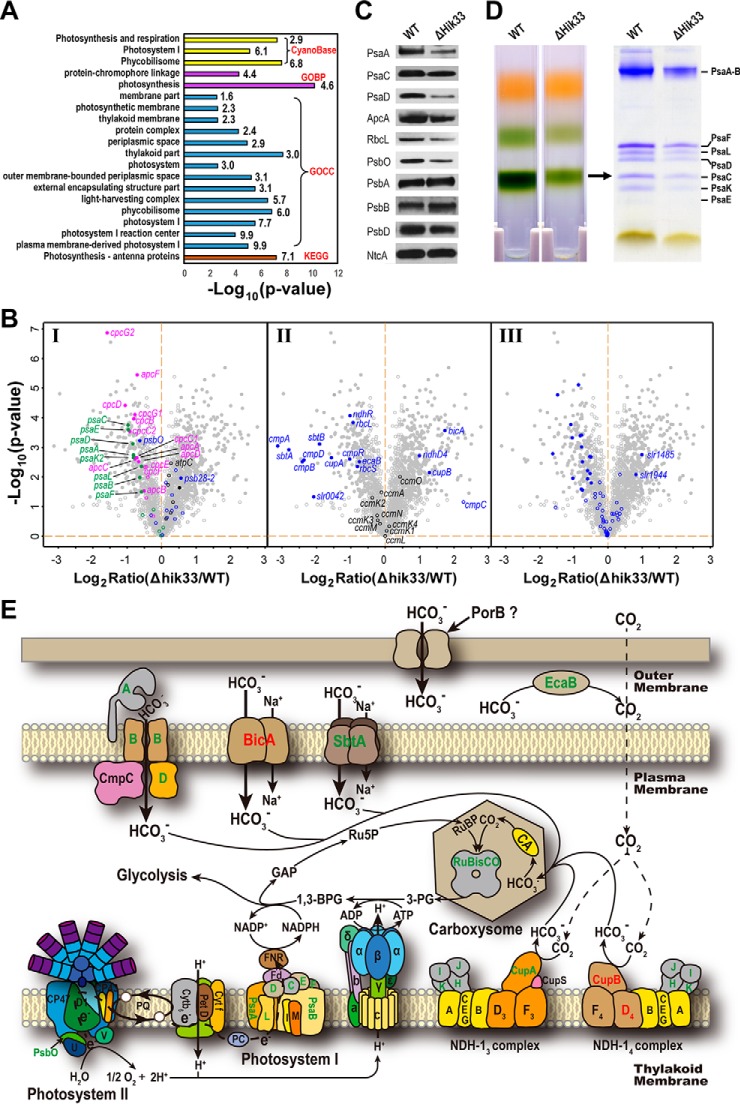

Depletion of Hik33 Significantly Downregulated Proteins in Photosynthetic Machineries and CO2 Assimilation

To uncover the repressed functions in Δhik33, Fisher's-exact test was employed to examine the enrichment of gene ontology (GO) terms, KEGG pathways, and the functional groups annotated by the CyanoBase in the downregulated proteins (35). Consistent with the previously observed repression of photosynthetic activity in Δhik33 (37), the majority of the enriched categories are related with photosynthesis (Fig. 3A). Specifically, most proteins in PS I and PBS were significantly downregulated in the mutant, whereas the proteins in photosystem II (PS II) except PsbO were largely unchanged, or even slightly upregulated, as also confirmed by western-blotting (Fig. 3B, panel I and Fig. 3C). Downregulation of PsbO, a subunit of the oxygen evolution complex, but not the other PS II subunits is consistent with previous reports that PsbO depletion represses oxygen evolution but not the accumulation of PS II reaction center (38–41). In addition, downregulation of PsbO may lead to increased sensitivity to photodamage, as previously shown by a psbO-deletion mutant with accelerated turnover of D1 protein (42). Consistently, the two FtsH proteases (Slr0228 and Slr1604) involved in the turnover of photodamaged D1 protein were upregulated in Δhik33 (43, 44), whereas the other two FtsH proteases (Sll1463 and Slr1390) not involved in the process were not changed (supplemental Table S2). Moreover, the chaperon-like protein Ycf39 (Slr0399), a putative PS II assembly factor, and HliD were also upregulated in ΔHik33 (supplemental Table S2). Ycf39 interacts with HliD during the assembly of light harvesting complex (45), upregulation of the two proteins is probably important to keep PS II at a desired level for the mutant.

Fig. 3.

Depletion of Hik33 significantly represses proteins in photosynthetic machineries and CO2 assimilation. A, Fisher's-exact test for the functional enrichment in the downregulated proteins in Δhik33. The gene ontology terms (GOCC and GOBP), KEGG pathways (KEGG), and functional categories annotated by the CyanoBase (CyanoBase) were included for the analysis. p < 0.05 and the enrichment factor > 1.5 were used as the cutoffs to include all enriched categories. The types of the categories and the enrichment factors are shown to the left of the bars. B, Volcano plots showing the differentially expressed proteins in Δhik33, which include proteins involved in photosynthesis (PS I, PS II, and PBS) (Left panel), proteins involved in CO2 uptake and assimilation (middle panel), and the periplasmic proteins (right panel). C, Western-blot validation of the differential expression for the indicated proteins between the WT and Δhik33. D, Confirmation of the reduced levels of PS I trimmer and its subunits in Δhik33. The PS I trimmer was prepared using sucrose gradient centrifugation as described in Methods, and separated by SDS-PAGE to show the individual subunits as indicated. E, The diagram shows the coordinated downregulation of proteins in the PET and CO2 assimilation. Proteins labeled in green and red are downregulated and upregulated, respectively, in Δhik33. Proteins labeled in black are not significantly different in expression between the WT and Δhik33.

Among all PBS subunits, downregulation of CpcG2 is the most significant (Fig. 3B, panel I). CpcG1 is the primary rod-core linker for normal PBS (46), whereas CpcG2 links the abnormal PBS without the allophycocyanin core directly to PS I, but not PS II (46–48). In this context, downregulation of CpcG2 is well coordinated with the downregulation of PS I. Accordingly, the two proteins CcaS (Sll1475) and CcaR (Slr1584) that regulate CpcG2 expression and accumulation of CpcG2-PBS as a chromatic acclimation system were also downregulated in the mutant (49) (supplemental Table S2).

Because PS I functions mainly through forming trimers (27), we also investigated whether the formation of PSI trimer was repressed in the mutant. As expected, the PS I trimers separated by sucrose gradient centrifugation was significantly decreased in Δhik33 compared with that of the WT (Fig. 3D, left panel). Consistently, all subunits from the purified PS I trimers were significantly decreased (Fig. 3D, right panel). As a control, the carotenoids-containing yellow fraction was largely unchanged between the two strains (Fig. 3D, left panel).

Downregulation of PBS, PS I, and PsbO strongly suggests that photosynthetic electron transport (PET) and the dependent NADPH production are significantly repressed. Therefore, the assimilation of CO2 could be repressed because NADPH is indispensable for this process. Indeed, proteins involved in all three characterized low CO2-inducible high affinity CO2/HCO3− uptake systems were significantly repressed. These include the HCO3− transporter encoded by the cmp operon (cmpA, cmpB, cmpD, and slr0042) and its activator CmpR (50, 51), the Na+/HCO3− symporter SbtA (52), and CupA of the CO2 uptake system NDH-13. (Fig. 3B, panel II, and Fig. 3E) (53–55). In contrast, the proteins involved in the constitutively expressed low affinity CO2/HCO3− uptake systems were upregulated in the mutant, including the HCO3− transporter BicA (56), and the CO2 transporter NDH-14 subunits CupB and NdhD4 (Fig. 3B, panel II, and Fig. 3E) (53, 54, 57). Because the high affinity systems take the major role in CO2 uptake in the ambient level of CO2 used in the current study (51), simultaneous downregulation of these systems could lead to severe CO2 starvation. Moreover, the carbonic anhydrase EcaB (Slr0051) converting CO2 to HCO3− in periplasm was also significantly downregulated (58) (Fig. 3B, panel II), further exaggerating the stress of CO2 starvation caused by impaired high affinity CO2/HCO3− transport systems. Accordingly, both Rubisco subunits were downregulated in response to the reduced availability of fixable CO2 (Fig. 3B, panel II) (59). The coordinated downregulation of photosynthesis and CO2 assimilation eventually impacts the central carbon metabolism, and affects the biomass production. This explains why Δhik33 survives but grows much slowly compared with WT under the photoautotrophic condition with medium light intensity (Fig. 1A) (15). Notably, NdhR, the negative regulator of the operon encoding NdhD3/NdhF3/CupA/CupS and SbtA (Fig. 3B, panel II) (60, 61), was also downregulated. Such an inconsistency could be a feed-back response of the mutant to raise the expression level of the downregulated CO2/HCO3− uptake systems.

In addition to these functions, periplasmic proteins were also significantly downregulated because of Hik33 depletion as indicated by the significant enrichment of the GO term periplasmic space in the downregulated proteins (Fig. 3A). Indeed, most the experimentally identified periplasmic proteins were downregulated or unchanged (58), and only two proteins (Slr1485 and Slr1944) were upregulated in Δhik33 (Fig. 3B, panel III). Though the detail is unknown, downregulation of periplasmic protein many significantly affect the adaptation of the cyanobacterium to changing environment, as periplasmic proteins are usually involved in transmission of environmental signals (58).

Depletion of Hik33 Differentially Impacted the Expression of Proteins in the Network of Carbon Metabolism and Nitrogen Assimilation

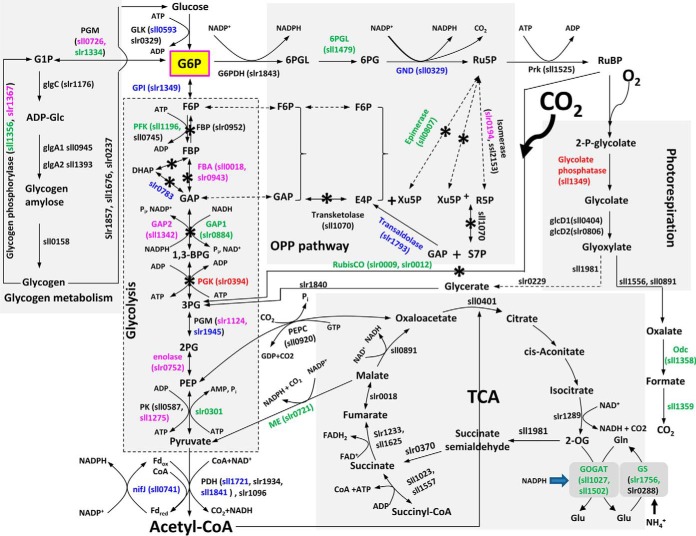

The downregulations of photosynthetic machineries and proteins in CO2 assimilation strongly suggest that the carbon metabolism is severely impacted in Δhik33. This is evident when mapping the differentially expressed proteins to the protein network of carbon metabolism (Fig. 4). Generally, the proteins involved in sugar catabolism such as critical enzymes in glycolysis, the oxidative pentose phosphorylation (OPP) pathway, and glycogen breakdown were downregulated, which include PFK, GAP1, 6PGL, and the glycogen phosphorylase Sll1356. Also in these pathways, a number of other proteins were slightly downregulated (fold change: 1>Δhik33/WT>0.49, p < 0.05) (Fig. 4). In contrast, many proteins involved in gluconeogenesis were slightly upregulated (1<Δhik33/WT<1.4, p < 0.05), which include FBA (Sll0018, Slr0943) and GAP2. No proteins in the TCA cycle was impacted by Hik33 depletion.

Fig. 4.

Mapping of the differentially expressed proteins in Δhik33 to a protein network for carbon metabolism. The direction and the extent of differential expression of a protein is indicated by a color. Red: upregulated in Δhik33 (fold change > 1.4, p < 0.05). Pink: slightly upregulated in Δhik33 (1 < fold change < 1.4, p < 0.05). Green: downregulated in Δhik33 (fold change < 0.49, p < 0.05). Blue: slightly downregulated in Δhik33 (0.49 < fold change < 1, p < 0.05). Black: no change.

The presumed CO2 deficiency (Fig. 3B, panel II), if true, may activate the oxygenase activity of Rubisco leading to increased photorespiration and production of phosphoglycolate (2PG), which is toxic and must be salvaged for the mutant to survive (62). The elevated expression Sll1349 (Fig. 4), the phosphoglycolate phosphatase responsible for the conversion of 2PG to glycolate, is critically important to eliminate the excess amount of toxic 2PG. Glyoxylate, the product converted from glycolate, can be further metabolized through three distinct routes, namely, the photorespiratory C2 cycles similar with that in plants, the bacterial glycerate pathway, and the complete decarboxylation to produce CO2 (62). No protein in the first two routes was significantly changed in the mutant, and the two proteins responsible for decarboxylation in the third route were significantly downregulated, suggesting that this route is significantly inhibited. The only upregulated protein involved in the metabolism of glyoxylate is phosphoglycerate kinase PGK, which is essential for recycling of phosphoglycerate through the Calvin cycle (Fig. 4). PGK is also involved in both glycolysis and gluconeogenesis but is the only protein in the two pathways that were significantly upregulated, suggesting that upregulation of PGK is probably mainly for the recycling of the photorespiration product. This notion is consistent with the upregulation of glycolate phosphatase, the only other significantly upregulated protein in the network of the mutant (Fig. 4). Remarkably, all proteins involved in the CO2-releasing reactions in the network were downregulated (Fig. 4), suggesting that the mutant cells are trying to recycle fixed carbon to deal with CO2 deficiency caused by downregulation of CO2/HCO3− uptake system.

The overall downregulation of carbon metabolism may require reduced nitrogen assimilation to maintain carbon/nitrogen (C/N) balance. Indeed, three proteins in the glutamine synthetase (GS) - glutamine oxoglutarate aminotransferase (GOGAT) system responsible for nitrogen assimilation were downregulated (Fig. 4). The only exception is the protein GlnN encoded by slr0288. The quantitation of GlnN was not confident (p > 0.05), though its fold change is smaller than 0.5. Nevertheless, GlnN is not the major glutamine synthetase in Synechocystis. Instead, GlnA (Slr1756) takes a major role in nitrogen assimilation through its glutamine synthetase activity, because GlnA is much more abundant than GlnN in Synechocystis (32). Concordantly, the two inhibitors of GlnA, namely, GifA and GifB were significantly upregulated in the mutant (63), further repressing the activity of GS.

In contrast to the downregulated GS-GOGAT system, many proteins involved in nitrogen assimilation were upregulated. These include subunits of nitrate/nitrite transport system NrtA, NrtC, and NrtD encoded by the nrt operon and the nitrate reductase NarB (supplemental Fig. S2). Accordingly, the positive regulators of the nrt operon CyAbrB2 and PamA were also upregulated (supplemental Fig. S2) (64, 65). The nitrate reductase NirA was also slightly upregulated, though its measured fold change and p value were below the thresholds of significant difference (supplemental Fig. S2). The contradiction between the downregulation of GS-GOGAT system and the upregulation of the other proteins in the upstream part of the nitrogen assimilation pathway indicates that the mutant is probably defective in coordinating the expression of the components of the nitrogen assimilation system.

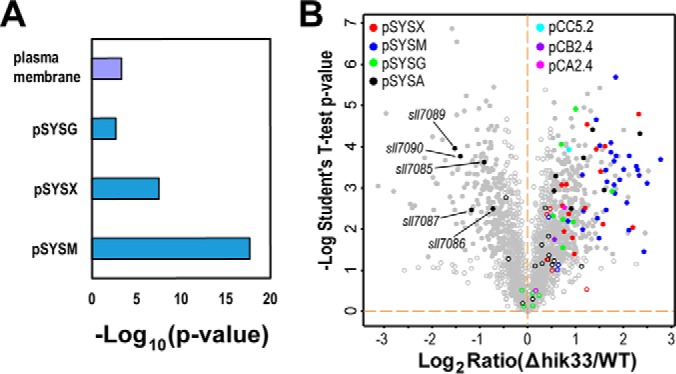

Depletion of Hik33 Significantly Impacted the Expression of Proteins of Plasmid Origin

The enriched functions in the upregulated proteins in Δhik33 was similarly examined by Fisher's-exact text, and no specific enrichment was found except the modest enrichment of the GO term plasma membrane (Fig. 5A). Interestingly, when plasmid-borne gene was included as a category for the enrichment analysis, we found proteins encoded by the three plasmids pSYSG, pSYSX, and pSYSM were highly enriched in the upregulated proteins (Fig. 5A). In fact, most the proteins of plasmid origin were upregulated, and only five proteins (Sll7085, Sll7086, Sll7087, Sll7089, and sll7090) encoded by an operon on the plasmid pSYSA were downregulated in the mutant (Fig. 5B). The operon locates closely to a Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindrome Repeats (CRISPR) and encodes four putative CRISPR-associated (Cas) proteins including Sll7085, Sll7087, Sll7089, and Sll7090. Deletion of sll7090 results in complete loss of the precursor and processed RNA molecules transcribed from the CRISPR (66). Thus, downregulation of the Cas proteins in the mutant may affect the adaptive immunity conferred by the Crisper-Cas system against certain genetic elements from the environment.

Fig. 5.

Depletion of Hik33 induces high expression of proteins encoded by plasmid-borne genes. A, Fisher's-exact test for the functional enrichment of proteins upregulated in Δhik33. In addition to all the categories included in Fig. 3A, all endosymbiotic plasmids of Synechocystis were also included for the analysis to determine whether the proteins encoded by the plasmid-borne gene are significantly enriched. The same cutoffs as in Fig. 3A were used for the analysis. B, Volcano plot showing the identification of proteins encoded by the plasmid-borne genes. The proteins encoded by the genes from the same plasmid were displayed with the same color as indicated. The gray spots represent all proteins encoded by genes on the chromosome.

Hik33 Regulates a Wide Spectrum of Stress-responsive Proteins

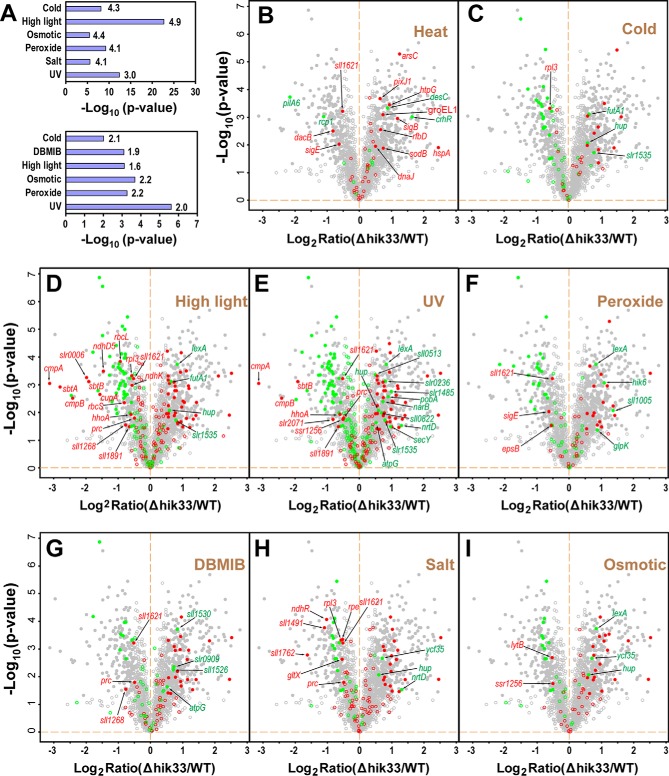

Large body of evidence has implicated Hik33 in stress responses (15–18, 67, 68). However, the identities and the directions of differential expression of the Hik33-regulated stress responsive proteins remain to be thoroughly characterized. Thus, we collected previously identified genes of Synechocystis responsive to up to eight different stress conditions, including heat, cold, HL, UV irradiation, peroxide treatment, DBMIB treatment, salt, and osmotic stress (8, 18, 69–75). The upregulated and downregulated genes in each stress condition, either in transcription or translation, were examined for their enrichment in the downregulated and the upregulated proteins in Δhik33, respectively, by Fisher's-exact test. In the downregulated proteins in Δhik33, genes downregulated in different types of stresses including cold, HL, osmotic, peroxide, salt, and UV irradiation were significantly enriched (Fig. 6A, upper panel, Fig. 6C–6I, and supplemental Table S2). In the upregulated proteins, genes upregulated in different types of stresses including cold, DBMIB, HL, osmotic stress, peroxide, and UV irradiation were significantly enriched (Fig. 6A, Lower panel, Fig. 6C–6I, and supplemental Table S2). Such a correlation strongly suggests that in general Hik33 positively regulates stress-repressive proteins while negatively regulates stress-inducible proteins. Note that the enrichments of heat-responsive genes in both upregulated and downregulated proteins in Δhik33 were not statistically significant (Fig. 6A and 6B), because only a limited number of heat-responsive proteins were identified in the original study (70).

Fig. 6.

Deletion of hik33 impacts the expression of proteins involved in divergent stress responses. A, Fisher's-exact test for enrichment analysis of stress-responsive proteins in the downregulated (upper panel) and upregulated (lower panel) proteins (p < 0.05). The genes responsive to the indicated types of stresses were collected from previous reports generated by transcriptomics and/or proteomics approaches. The enrichment factors are shown to the left of the bars. B–I, Volcano plots showing the mapping of genes responsive to different type of stresses as indicated to the differentially expressed proteins in Δhik33. In each panel the red and the green spots indicate genes whose expression is induced or repressed, respectively, by the indicated stress. The filled cycles indicate proteins with significant changes in expression in Δhik33. Note that all proteins that are downregulated in Δhik33 and upregulated in the stress responses or vice versa were labeled with gene symbols or accession numbers.

Though the positive correlation is apparent (Fig. 6), there are still considerable number of proteins that are negatively correlated in each stress condition (Fig. 6C–6I). For example, CrhR was upregulated in both Δhik33 and in response to cold stress, but downregulated in response to heat stress (Fig. 6B, 6C). In fact, CrhR is not directly regulated by Hik33 (76), and it is expectable that many other stress type-specifically responsive proteins may not be directly regulated by Hik33 either, as shown for CrhR. As such, Hik33 is more likely a general regulator responsible for a common response to divergent types of stresses.

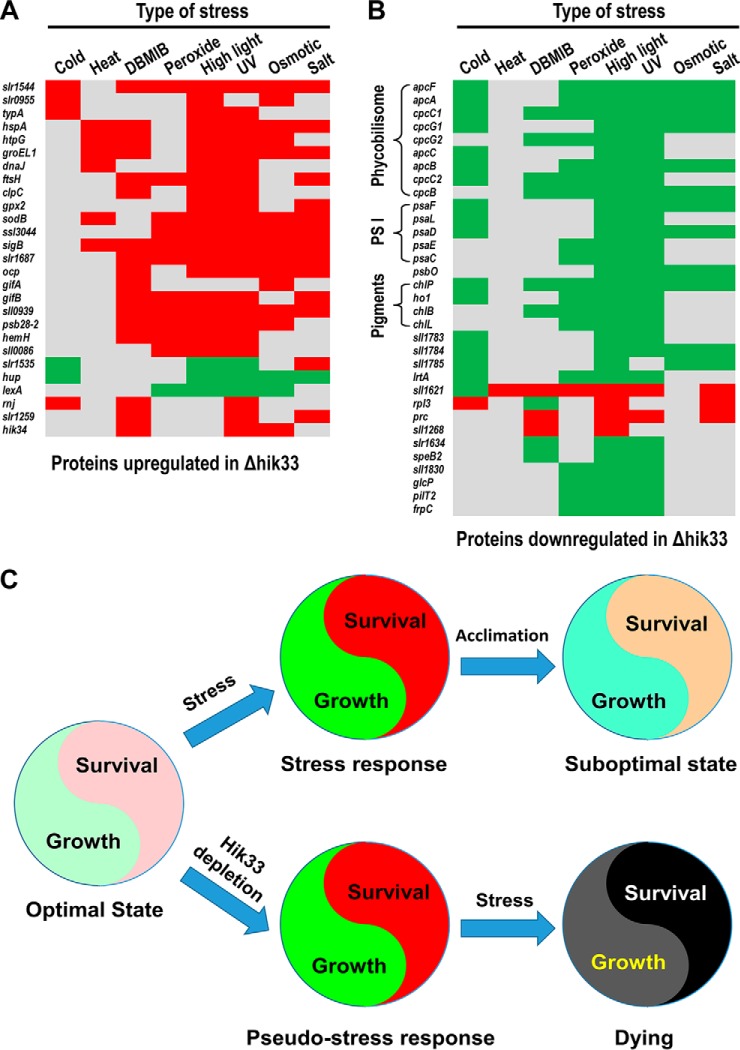

Determination of Hik33-regulated Common Stress-responsive (CSR) Proteins

To find proteins that are regulated by Hik33 and commonly involved in different types of stresses, we selected only differentially expressed proteins in Δhik33 whose coding genes are also concordantly upregulated or downregulated in at least three out of the eight stress conditions, either in transcription or translation (Fig. 6). Using this criterion, 27 and 33 proteins upregulated and downregulated in Δhik33, respectively, were defined as the CSR proteins (Fig. 7). Most CSR proteins upregulated in Δhik33 were also upregulated in at least three types of stresses, such as the heat shock proteins hspA and htpG, the chaperons GroEL1 and DnaJ, and the proteases FtsH and ClpC. Only three proteins, namely Slr1535, Hup, and LexA, are outliers which were upregulated in Δhik33 but downregulated in at least three stress conditions (Fig. 7A). Notably, LexA upregulation in Δhik33 relative to the WT was previously shown to occur also at the transcription level in the normal condition, but the repression of its transcription in the mutant responding to salt stress is much quicker compared with that of WT (16). Similarly, most CSR proteins downregulated in Δhik33 are downregulated in at least three different stress conditions (Fig. 7B). These proteins are presumably positively regulated by Hik33 and include several subunits of PS I, PBS, and proteins involved in chlorophyll (Chl) synthesis, suggesting that repression of photosynthetic activity is a general response to the majority types of stresses. Remarkably, PsbO is the only downregulated PS II subunit and its repression is sufficient to reduce PS II activity (15). Again, four outlier proteins in this group including Sll1621, Rpl3, Prc, and Sll1268 are upregulated in at least three stress responses (Fig. 7B). These proteins are presumably regulated positively by Hik33 in normal condition, but their expression can be induced through Hik33-independent mechanisms in stresses.

Fig. 7.

Hik33 regulates the CSR proteins. The heat maps show the upregulated (A) and the downregulated proteins (B) in Δhik33 whose gene expression are upregulated or downregulated in at least three different types of stress responses. Red and green indicate upregulation and downregulation, respectively, in each stress response. C, A diagramed model explaining why Δhik33 is more sensitive to abiotic stresses.

The consistency in the changes of the two sets of proteins in responses to stresses and to depletion of Hik33 and their causal relationship with the increased sensitivity of Δhik33 to divergent stresses can be better illustrated with a model (Fig. 7C). The proteins upregulated both in stress conditions and in Δhik33 constitute a module that is important for coping with abiotic stresses and is essential for survival of Synechocystis in such conditions. Similarly, the proteins downregulated in both constitute the other module that is important for photosynthesis and CO2 assimilation and is essential for cell growth. In normal conditions the WT Synechocystis maintain a relatively balanced level of the two modules for the optimal growth and survival. Abiotic stresses, if exerted, can induce concordant upregulation of the survival module and the downregulation of the growth module, a typical stress response (Fig. 7C). If the stress is long-lasting, the WT cells can acclimate to it partly through reducing the extent of differential expression of the two modules. Thus, the WT cells can survive and resume growth. In Δhik33 cultured in normal condition, the depletion of Hik33 induces a response mimicking true abiotic stress responses in both growth phenotype and protein expression. However, the irreversible deletion of hik33 permanently affects the expression of the two modules, and thus disables the mutant for acclimation to any true abiotic stresses. This model explains why Δhik33 was reported to be more sensitive to different types of stresses and was further confirmed by culturing the mutant in stress conditions including high light, salt, and cold (supplemental Fig. S3) (15–18, 68).

DISCUSSION

In the present study we intended to answer how Hik33 is involved in the divergent types of stress responses through quantitative proteomics and bioinformatics. We found that depletion of Hik33 significantly downregulated 208 and upregulated 369 proteins. In addition to the 60 CSR proteins (Fig. 7), many other proteins that are involved in one or two types of stress response were also differentially expressed in Δhik33 (Fig. 7 and supplemental Table S2). These findings underscore the significance of Hik33 as a general regulator of stress responses. We propose that the main targets regulated by Hik33 are stress-responsive proteins. In normal condition, Hik33 represses and activates the expression of stress-inducible and stress-repressive proteins in the WT, respectively (Figs. 5 and 6). However, in stress conditions, such repression and activation by Hik33 are eliminated resulting in activation and repression of stress-inducible and stress-repressive proteins, respectively. Depletion of Hik33 dysregulates the expression of these proteins and generates an intracellular response (pseudo-stress response: PSR) like the responses of the WT Synechocystis exposed to true abiotic stresses, at least in terms of protein expression. In contrast to the true responses that are usually short term with repairable damage, such a PSR is permanent. The long-lasting PSR and the consequent irreversible damage are presumably the major causes for the increased sensitivity of Δhik33 to true stresses such as HL (supplemental Fig. S3) (15).

Among the downregulated CSR-proteins the most prominently enriched function is photosynthesis, particularly PS I and PBS (Fig. 7), which are important for propagation of Synechocystis by providing material and energy necessary for cell growth. Downregulation of such a function indicates that Δhik33 and stressed WT cells need to cope with the deleterious intracellular conditions resulting from Hik33 depletion and stresses, respectively, through sacrificing propagation. Downregulation of PS I is essential for cyanobacteria to survive HL stress (77, 78). Our analysis indicates that downregulation of PS I, and probably of PBS and Chl synthesis as well, is important for Synechocystis to survive the other stresses such as cold, oxidation, osmotic, UV, and salt in addition to HL (Fig. 7B). PsbO is the only downregulated PS II subunits in Δhik33 and in response to stresses such as HL, UV, salt, and osmotic stress (Fig. 7B). Downregulation of PsbO is well coordinated with the reduced level of PS I by reducing the supply of electrons extracted from water to the PET. As such, overexcitation of PS I and the consequent production of toxic reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the condition of insufficient supply of electrons from PS II can be avoided (79). In addition, repression of PsbO might also contribute to the observed differential expression of proteins in C and N metabolism (supplemental Fig. S2), as previously demonstrated by a psbO-deletion mutant (80). Together, these findings suggest that downregulation of photosynthetic machinery is a general response to divergent type of stresses and is mediated, at least partially, through Hik33.

In contrast, many heat shock proteins, chaperons, proteases, and proteins involved in the regulation of intracellular redox states were upregulated in response to Hik33 depletion or abiotic stresses (Figs. 6, 7, and supplemental Table S2). Protein denaturation occurs in almost all abiotic stresses, resulting in accumulation of denatured proteins in the cytosol. This in turn evokes the stress response (81). Upregulation of heat shock proteins, chaperons, and proteases such as HspA, HtpG, GroEL1, DnaJ, and ClpC could be important to repair such a damage and is important for cell survival (Fig. 7). Moreover, abiotic stresses, and deletion of hik33 as well, could induce intracellular redox changes and production of ROS. Consequently, proteins involved in redox regulation and ROS scavenging, which include MrgA (Slr1894) (82), the peroxiredoxin Sll0755 and Slr0242 (83), Gpx1 (Slr1711) and Gpx2 (Slr1922) (84), SodB, KatF (Sll1987) (85), and Tpx (Sll0755) (85), were also upregulated (supplemental Table S2). Finally, damage to PS II is more likely to occur in stresses or in Δhik33, which requires more proteins such as FtsH and OCP for protection and repair (43, 44, 86, 87). Together, the functions of upregulated proteins, though divergent, are critical for protecting the cyanobacterium from damage caused by abiotic stresses or Hik33-depletion. The coordinated upregulation and downregulation of the functions critical for propagation and survival, respectively, could be an evolved strategy of the cyanobacterium to survive in stress conditions, and Hik33 is a general but not the sole regulator for the implementation of such a strategy.

Several differentially expressed proteins are directly regulated by Hik33 through the putative Hik33-RpaB system (12). RpaB, whose expression is not significantly changed in Δhik33 (supplemental Table S2), is a known Rre of Hik33 and can specifically regulate gene expression through binding to a specific AT-rich DNA sequence in the promoter region of the targeted genes, the so-called HL regulatory 1(HLR1) element (88–90). Several genes in Synechocystis are known to have HLR1 in the promoter region. These include HL-repressive genes such as psaAB, psaD, psaC, psaE, psaF, psaK1, and psaL (91); HL-inducible genes such as hilA, hliB, hliC, hliD, psbA2, and nblA1 (15, 89). RpaB was previously suggested to be phosphorylated by Hik33 in normal light (NL) and binds to HLR1 in the promoter region of the genes mentioned. In HL RpaB is dephosphorylated and released from HLR1 in a short time, but can be rephosphorylated and binds to HLR1 again (92, 93). Binding of RpaB to HLR1 of HL-repressive genes enhances their expression in NL, and release of RpaB in HL inhibits their expression. In contrast, binding of RpaB to and release of RpaB from HLR1 of HL-inducible genes have opposite effects from those observed for HL-repressive genes. Thus, RpaB binding could act as an enhancer or repressor depending on the type of targeted genes (88). In Δhik33, RpaB is not altered in expression but presumably dephosphorylated and released from HLR1 because of depletion of Hik33 kinase activity, and this can reasonably explain the coordinated downregulation of HL-repressive proteins such as PS I subunits and upregulation of HL-inducible proteins such as HliD (Fig. 3B and supplemental Table S2). It is worth noting that psaA2 is highly HL-inducible at the transcription level, and that in NL its mRNA level is significantly higher in Δhik33 than in WT (15), but in NL the D1 protein encoded by psbA2 is only slightly increased in Δhik33 compared with WT (supplemental Table S2). This is presumably because of the operation of D1 degradation and repairing system that maintains a relatively stable level for this important protein. We failed to identify NblA1, another HL-inducible protein (69, 94), probably because of its small size (34). We expected that NblA1 is upregulated in Δhik33 and involved in the downregulation of PBS subunits (Fig. 3B). However, downregulation of PBS in Δhik33 is not solely because of degradation, but also because of repression of transcription of PBS subunits (Fig. 2E) (19). Unfortunately, in Synechocystis we did not find a DNA sequence in the promoter region of genes encoding PBS subunits with significant homology to HLR1, although in Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942 cpcB was found to have a HLR1 in its promoter region (89). In addition to the genes known with HLR1, other genes encoding differentially expressed proteins in Δhik33 may also have the motif in their promoters and regulated by Hik33-RpaB directly. Searching the DNA sequence in the promoter region for potential HLR1 motif can easily identify such genes such as chlP, hemA, ho1, etc. However, confirming whether these potential HLR1 motifs are functional is beyond the scope of the current study.

RpaB is probably not the only Rre that mediates the direct regulation of gene expression by Hik33. The Synechocystis genome encodes 42 putative Rres (12), and some of these have already been identified previously as the cognate Rre of Hik33 such as RpaA (12). Expression of RpaA is not significantly changed in Δhik33 either (supplemental Table S2). However, its phosphorylation status, targeting genes, and regulatory mechanism are largely unknown.

In addition to the direct regulation through Hik33-Rre system, the differential expression of many other proteins could also be regulated by Hik33 indirectly through the differential expression of the other regulatory proteins, including Hik34, Sll1130, SigB, SigE, etc. Hik34 is a known regulator of stress responses and is upregulated in Δhik33 (Fig. 7A) (12). Hik34 negatively regulates stress-responsive proteins such as HspA, ClpB1, SodB, HtpG, DnaK2, GroES, GroEL1, GroEL2, and DnaJ and is involved in different types of stress responses (95, 96). Similarly, Sll1130, a novel transcription factor that negatively regulates the expression of heat-responsive genes such as HspA and HtpG (97), is also upregulated in Δhik33. Upregulation of Hik34 and Sll1130 might be a feed-back response of the mutant to repress the PSR resulted from Hik33 depletion. SigB and SigE are two group 2 sigma factors, which are nonessential for cyanobacteria in normal growth condition but are involved in acclimation to changing environments (98). SigB is upregulated in response to multiple types of stresses and in Δhik33, and is important for the acclimation of Synechocystis to high salt through upregulation of HspA, GgpS, and carotenoids synthesis (99). Consistently, HspA, GgpS, water-soluble carotenoid protein OCP, and a protein involved in carotenoids synthesis (CrtD) are all upregulated in Δhik33 (supplemental Table S2). SigB is also important for short-term heat-shock response through upregulation of heat shock proteins such as HspA (100), and again, this could also be indirectly regulated by Hik33. Distinct from SigB, SigE was downregulated in Δhik33 and positively regulates the proteins involved in sugar catabolic pathways such as PfkA1(Sll1196), Gap1, Zwf, OpcA, Gnd, Tal, and GlgP (Sll1356) (101). Remarkably, all these proteins were downregulated in Δhik33 (Fig. 4 and supplemental Table S2), which was most likely achieved through the downregulation of SigE.

It has been previously observed that in a hik33-deficient mutant the extent of differential expression of some CSR genes, which include stress-repressive genes such as those encoding PS I and PBS subunits and stress-inducible genes such as ycf39 and slr1544, are significantly reduced in response to stress such as cold (75), as indicated by the reduced fold changes of mRNA levels compared with those in WT. This can probably be explained by our current observation that depletion of Hik33 alone mimics the effect of true abiotic stresses on the cyanobacterium. Consequently, significant stress-repression or stress-induction of such genes can be observed for WT but not the hik33-deficient mutant, because in the normal condition the differential expression has already occurred because of Hik33-depletion and stresses will no longer significantly change the extent of the differential expression of such genes. Nevertheless, this explanation is only applicable for a limited number of genes whose expression is tightly regulated by Hik33.

One of the interesting findings in the current study is the coherent upregulation of most the identified proteins of plasmid origin in Δhik33 (Fig. 5). The functions and expression pattern of such proteins in Synechocystis have previously been overlooked, at least in large scale studies, because of historic and technique reasons. In microarray based analyses, the genes included for analysis are exclusively from chromosome (19, 75), which prevents the detection of the expression of plasmid-borne genes. In early gel-based proteomics studies, the relatively low resolution and low throughput nature of this technique limit the analyses to only high abundance proteins (34), which also prevents the identification of most proteins of plasmid origin because they are usually low abundant (33, 34). Though the functional significance of these upregulated proteins of plasmid origin is largely unknown, it is conceivable to presume they could complement the functions of some repressed proteins of chromosome origin, as previously observed for the hik31 operon on the plasmid pSYSX (102, 103). However, in WT Synechocystis whether these proteins are also stress-inducible and functional in stress acclimation remain to be investigated. Only a few proteins of plasmid origin, which are involved in a putative CRISPER-Cas system, were downregulated in the mutant (Fig. 5B), suggesting that Δhik33 is probably defective in immune system that confers resistance to foreign genetic elements.

The facts that Hik33 regulates photosynthetic proteins and the stress-inducible proteins in response to different stresses and that Hik33 is homologous to ethylene receptor in higher plants suggest that the Hik33-dependent stress response could be a specialized function for photosynthetic organism, through which photosynthetic activity and the maintenance of intracellular homeostasis can be well coordinated to adapt to changing environments. Unfortunately, the mechanism underlying stress-induced Hik33 activation is poorly understood. It is generally accepted that in response to stresses Hik33 is activated through autophosphorylation of one of its histidine residues (11, 93, 104). Recent evidence also demonstrated that membrane association of Hik33 is necessary for its activation because deletion of its transmembrane domains can completely abolish its stress-induced activation (104). However, little is known about the identities of the molecules that are perceived by and activating Hik33, which is the greatest challenge in elucidating the activation mechanism of HIk33. Nevertheless, our findings firmly establish Hik33 as a general and important regulator of multiple types of stresses for cyanobacteria.

Data Availability

The MS raw files have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the data set identifier PXD005085 (http://www.proteomexchange.org) (105).

Footnotes

Author Contributions: H.G., Q.H., and Y.W. designed the research, H.G., L.F., X.H., J.W., and Y.L. performed the experiments, H.G., L.F., X.H., J.W., W.C., and Y.W. did the data analysis. H.G., W.X., and Y.W. wrote the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the manuscript.

* This work was supported by a grant from National Natural Science Foundation of China (31670234 to YW).

This article contains supplemental material.

This article contains supplemental material.

1 The abbreviations used are:

- HL

- High light

- WT

- Wild type

- WCL

- Whole cell lysate

- NL

- Normal light

- Chl

- Chlorophyll

- PS I

- Photosystem I

- PS II

- Photosystem II

- PBS

- Phycobilisome

- PET

- Photosynthetic electron transport

- Synechocystis

- Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803

- TMT

- Tandem mass tag

- CSR

- common stress responsive

- PSR

- pseudo-stress response

- RP-HPLC

- reversed phase - high performance liquid chromatography

- OPP

- oxidative pentose phosphorylation

- CAN

- acetonitrile

- FDR

- False discovery rate

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- FASP

- filter-aided sample preparation.

REFERENCES

- 1. De Marais D. J. (2000) Evolution. When did photosynthesis emerge on Earth? Science 289, 1703–1705 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Johnson Z. I., Zinser E. R., Coe A., McNulty N. P., Woodward E. M., and Chisholm S. W. (2006) Niche partitioning among Prochlorococcus ecotypes along ocean-scale environmental gradients. Science 311, 1737–1740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kasting J. F., and Siefert J. L. (2002) Life and the evolution of Earth's atmosphere. Science 296, 1066–1068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lubner C. E., Applegate A. M., Knorzer P., Ganago A., Bryant D. A., Happe T., and Golbeck J. H. (2011) Solar hydrogen-producing bionanodevice outperforms natural photosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 20988–20991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lubner C. E., Knorzer P., Silva P. J., Vincent K. A., Happe T., Bryant D. A., and Golbeck J. H. (2010) Wiring an [FeFe]-hydrogenase with photosystem I for light-induced hydrogen production. Biochemistry 49, 10264–10266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Xue Y., Zhang Y., Cheng D., Daddy S., and He Q. (2014) Genetically engineering Synechocystis sp. Pasteur Culture Collection 6803 for the sustainable production of the plant secondary metabolite p-coumaric acid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 9449–9454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Varman A. M., Xiao Y., Pakrasi H. B., and Tang Y. J. (2013) Metabolic engineering of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 for isobutanol production. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 908–914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kanesaki Y., Suzuki I., Allakhverdiev S. I., Mikami K., and Murata N. (2002) Salt stress and hyperosmotic stress regulate the expression of different sets of genes in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 290, 339–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hernandez-Prieto M. A., Semeniuk T. A., Giner-Lamia J., and Futschik M. E. (2016) The transcriptional landscape of the photosynthetic model Cyanobacterium synechocystis sp. PCC6803. Sci. Rep. 6, 22168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Singh A. K., Elvitigala T., Cameron J. C., Ghosh B. K., Bhattacharyya-Pakrasi M., and Pakrasi H. B. (2010) Integrative analysis of large scale expression profiles reveals core transcriptional response and coordination between multiple cellular processes in a cyanobacterium. BMC Syst. Biol. 4, 105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sinetova M. A., and Los D. A. (2016) New insights in cyanobacterial cold stress responses: Genes, sensors, and molecular triggers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1860, 2391–2403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Los D. A., Zorina A., Sinetova M., Kryazhov S., Mironov K., and Zinchenko V. V. (2010) Stress sensors and signal transducers in cyanobacteria. Sensors 10, 2386–2415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bartsevich V. V., and Shestakov S. V. (1995) The dspA gene product of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 influences sensitivity to chemically different growth inhibitors and has amino acid similarity to histidine protein kinases. Microbiology 141, 2915–2920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Suzuki I., Los D. A., and Murata N. (2000) Perception and transduction of low-temperature signals to induce desaturation of fatty acids. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 28, 628–630 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hsiao H. Y., He Q., Van Waasbergen L. G., and Grossman A. R. (2004) Control of photosynthetic and high-light-responsive genes by the histidine kinase DspA: negative and positive regulation and interactions between signal transduction pathways. J. Bacteriol. 186, 3882–3888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Li T., Yang H. M., Cui S. X., Suzuki I., Zhang L. F., Li L., Bo T. T., Wang J., Murata N., and Huang F. (2012) Proteomic study of the impact of Hik33 mutation in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 under normal and salt stress conditions. J. Proteome Res. 11, 502–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Marin K., Suzuki I., Yamaguchi K., Ribbeck K., Yamamoto H., Kanesaki Y., Hagemann M., and Murata N. (2003) Identification of histidine kinases that act as sensors in the perception of salt stress in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 9061–9066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mikami K., Kanesaki Y., Suzuki I., and Murata N. (2002) The histidine kinase Hik33 perceives osmotic stress and cold stress in Synechocystis sp PCC 6803. Mol. Microbiol. 46, 905–915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tu C. J., Shrager J., Burnap R. L., Postier B. L., and Grossman A. R. (2004) Consequences of a deletion in dspA on transcript accumulation in Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803. J. Bacteriol. 186, 3889–3902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Griffin T. J., Gygi S. P., Ideker T., Rist B., Eng J., Hood L., and Aebersold R. (2002) Complementary profiling of gene expression at the transcriptome and proteome levels in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 1, 323–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kaneko T., Sato S., Kotani H., Tanaka A., Asamizu E., Nakamura Y., Miyajima N., Hirosawa M., Sugiura M., Sasamoto S., Kimura T., Hosouchi T., Matsuno A., Muraki A., Nakazaki N., Naruo K., Okumura S., Shimpo S., Takeuchi C., Wada T., Watanabe A., Yamada M., Yasuda M., and Tabata S. (1996) Sequence analysis of the genome of the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803. II. Sequence determination of the entire genome and assignment of potential protein-coding regions. DNA Res. 3, 109–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Toennies G., and Gallant D. L. (1949) The relation between photometric turbidity and bacterial concentration. Growth 13, 7–20 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Moran R. (1982) Formulae for determination of chlorophyllous pigments extracted with n,n-dimethylformamide. Plant Physiol. 69, 1376–1381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wang Y., Sun J., and Chitnis P. R. (2000) Proteomic study of the peripheral proteins from thylakoid membranes of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Electrophoresis 21, 1746–1754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang Y., Xu W., and Chitnis P. R. (2009) Identification and bioinformatic analysis of the membrane proteins of synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Proteome Sci. 7, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hou J. M., Boichenko V. A., Wang Y. C., Chitnis P. R., and Mauzerall D. (2001) Thermodynamics of electron transfer in oxygenic photosynthetic reaction centers: a pulsed photoacoustic study of electron transfer in photosystem I reveals a similarity to bacterial reaction centers in both volume change and entropy. Biochemistry 40, 7109–7116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chitnis V. P., and Chitnis P. R. (1993) PsaL subunit is required for the formation of photosystem I trimers in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. FEBS Lett. 336, 330–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wisniewski J. R., Zougman A., and Mann M. (2009) Combination of FASP and StageTip-based fractionation allows in-depth analysis of the hippocampal membrane proteome. J Proteome Res. 8, 5674–5678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Udeshi N. D., Svinkina T., Mertins P., Kuhn E., Mani D. R., Qiao J. W., and Carr S. A. (2013) Refined preparation and use of anti-diglycine remnant (K-epsilon-GG) antibody enables routine quantification of 10,000s of ubiquitination sites in single proteomics experiments. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 12, 825–831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cox J., and Mann M. (2008) MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 1367–1372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cox J., and Mann M. (2012) 1D and 2D annotation enrichment: a statistical method integrating quantitative proteomics with complementary high-throughput data. BMC Bioinformatics 13, S12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fang L., Ge H., Huang X., Liu Y., Lu M., Wang J., Chen W., Xu W., and Wang Y. (2017) Trophic mode-dependent proteomic analysis reveals functional significance of light-independent chlorophyll synthesis in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Mol. Plant 10, 73–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gao L., Ge H., Huang X., Liu K., Zhang Y., Xu W., and Wang Y. (2015) Systematically ranking the tightness of membrane association for peripheral membrane proteins (PMPs). Mol. Cell. Proteomics 14, 340–353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gao L., Wang J., Ge H., Fang L., Zhang Y., Huang X., and Wang Y. (2015) Toward the complete proteome of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Photosynthesis Res. 126, 203–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nakao M., Okamoto S., Kohara M., Fujishiro T., Fujisawa T., Sato S., Tabata S., Kaneko T., and Nakamura Y. (2010) CyanoBase: the cyanobacteria genome database update 2010. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, D379–D381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ting L., Rad R., Gygi S. P., and Haas W. (2011) MS3 eliminates ratio distortion in isobaric multiplexed quantitative proteomics. Nat. Methods 8, 937–940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. He Q., Dolganov N., Bjorkman O., and Grossman A. R. (2001) The high light-inducible polypeptides in Synechocystis PCC6803. Expression and function in high light. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 306–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Burnap R. L., Shen J. R., Jursinic P. A., Inoue Y., and Sherman L. A. (1992) Oxygen yield and thermoluminescence characteristics of a cyanobacterium lacking the manganese-stabilizing protein of photosystem II. Biochemistry 31, 7404–7410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Burnap R. L., and Sherman L. A. (1991) Deletion mutagenesis in Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 indicates that the Mn-stabilizing protein of photosystem II is not essential for O2 evolution. Biochemistry 30, 440–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Philbrick J. B., Diner B. A., and Zilinskas B. A. (1991) Construction and characterization of cyanobacterial mutants lacking the manganese-stabilizing polypeptide of photosystem II. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 13370–13376 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kimura A., Eaton-Rye J. J., Morita E. H., Nishiyama Y., and Hayashi H. (2002) Protection of the oxygen-evolving machinery by the extrinsic proteins of photosystem II is essential for development of cellular thermotolerance in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Plant Cell Physiol. 43, 932–938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Komenda J., and Barber J. (1995) Comparison of psbO and psbH deletion mutants of Synechocystis PCC 6803 indicates that degradation of D1 protein is regulated by the QB site and dependent on protein synthesis. Biochemistry 34, 9625–9631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Silva P., Thompson E., Bailey S., Kruse O., Mullineaux C. W., Robinson C., Mann N. H., and Nixon P. J. (2003) FtsH is involved in the early stages of repair of photosystem II in Synechocystis sp PCC 6803. Plant Cell 15, 2152–2164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Nixon P. J., Barker M., Boehm M., de Vries R., and Komenda J. (2005) FtsH-mediated repair of the photosystem II complex in response to light stress. J. Exp. Botany 56, 357–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chidgey J. W., Linhartova M., Komenda J., Jackson P. J., Dickman M. J., Canniffe D. P., Konik P., Pilny J., Hunter C. N., and Sobotka R. (2014) A cyanobacterial chlorophyll synthase-HliD complex associates with the Ycf39 protein and the YidC/Alb3 insertase. Plant Cell 26, 1267–1279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kondo K., Geng X. X., Katayama M., and Ikeuchi M. (2005) Distinct roles of CpcG1 and CpcG2 in phycobilisome assembly in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Photosynthesis Res. 84, 269–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kondo K., Mullineaux C. W., and Ikeuchi M. (2009) Distinct roles of CpcG1-phycobilisome and CpcG2-phycobilisome in state transitions in a cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Photosynthesis Res. 99, 217–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kondo K., Ochiai Y., Katayama M., and Ikeuchi M. (2007) The membrane-associated CpcG2-phycobilisome in Synechocystis: a new photosystem I antenna. Plant Physiol. 144, 1200–1210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hirose Y., Shimada T., Narikawa R., Katayama M., and Ikeuchi M. (2008) Cyanobacteriochrome CcaS is the green light receptor that induces the expression of phycobilisome linker protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 9528–9533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Omata T., Gohta S., Takahashi Y., Harano Y., and Maeda S. (2001) Involvement of a CbbR homolog in low CO2-induced activation of the bicarbonate transporter operon in cyanobacteria. J. Bacteriol. 183, 1891–1898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Omata T., Price G. D., Badger M. R., Okamura M., Gohta S., and Ogawa T. (1999) Identification of an ATP-binding cassette transporter involved in bicarbonate uptake in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7942. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 13571–13576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Shibata M., Katoh H., Sonoda M., Ohkawa H., Shimoyama M., Fukuzawa H., Kaplan A., and Ogawa T. (2002) Genes essential to sodium-dependent bicarbonate transport in cyanobacteria: function and phylogenetic analysis. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 18658–18664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Shibata M., Ohkawa H., Kaneko T., Fukuzawa H., Tabata S., Kaplan A., and Ogawa T. (2001) Distinct constitutive and low-CO2-induced CO2 uptake systems in cyanobacteria: genes involved and their phylogenetic relationship with homologous genes in other organisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 11789–11794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Maeda S., Badger M. R., and Price G. D. (2002) Novel gene products associated with NdhD3/D4-containing NDH-1 complexes are involved in photosynthetic CO2 hydration in the cyanobacterium, Synechococcus sp. PCC7942. Mol. Microbiol. 43, 425–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zhang P., Battchikova N., Jansen T., Appel J., Ogawa T., and Aro E. M. (2004) Expression and functional roles of the two distinct NDH-1 complexes and the carbon acquisition complex NdhD3/NdhF3/CupA/Sll1735 in Synechocystis sp PCC 6803. Plant Cell 16, 3326–3340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Price G. D., Woodger F. J., Badger M. R., Howitt S. M., and Tucker L. (2004) Identification of a SulP-type bicarbonate transporter in marine cyanobacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 18228–18233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Xu M., Ogawa T., Pakrasi H. B., and Mi H. (2008) Identification and localization of the CupB protein involved in constitutive CO2 uptake in the cyanobacterium, Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. Plant Cell Physiol. 49, 994–997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Fulda S., Huang F., Nilsson F., Hagemann M., and Norling B. (2000) Proteomics of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. Identification of periplasmic proteins in cells grown at low and high salt concentrations. Eur. J. Biochem. 267, 5900–5907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Eisenhut M., Aguirre von Wobeser E., Jonas L., Schubert H., Ibelings B. W., Bauwe H., Matthijs H. C., and Hagemann M. (2007) Long-term response toward inorganic carbon limitation in wild type and glycolate turnover mutants of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. Plant Physiol. 144, 1946–1959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Figge R. M., Cassier-Chauvat C., Chauvat F., and Cerff R. (2001) Characterization and analysis of an NAD(P)H dehydrogenase transcriptional regulator critical for the survival of cyanobacteria facing inorganic carbon starvation and osmotic stress. Mol. Microbiol. 39, 455–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wang H. L., Postier B. L., and Burnap R. L. (2004) Alterations in global patterns of gene expression in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 in response to inorganic carbon limitation and the inactivation of ndhR, a LysR family regulator. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 5739–5751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Eisenhut M., Ruth W., Haimovich M., Bauwe H., Kaplan A., and Hagemann M. (2008) The photorespiratory glycolate metabolism is essential for cyanobacteria and might have been conveyed endosymbiontically to plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 17199–17204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Garcia-Dominguez M., Reyes J. C., and Florencio F. J. (2000) NtcA represses transcription of gifA and gifB, genes that encode inhibitors of glutamine synthetase type I from Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Mol. Microbiol. 35, 1192–1201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Osanai T., Sato S., Tabata S., and Tanaka K. (2005) Identification of PamA as a PII-binding membrane protein important in nitrogen-related and sugar-catabolic gene expression in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 34684–34690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ishii A., and Hihara Y. (2008) An AbrB-like transcriptional regulator, Sll0822, is essential for the activation of nitrogen-regulated genes in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Plant Physiol. 148, 660–670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Scholz I., Lange S. J., Hein S., Hess W. R., and Backofen R. (2013) CRISPR-Cas systems in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 exhibit distinct processing pathways involving at least two Cas6 and a Cmr2 protein. PloS One 8, e56470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kanesaki Y., Yamamoto H., Paithoonrangsarid K., Shoumskaya M., Suzuki I., Hayashi H., and Murata N. (2007) Histidine kinases play important roles in the perception and signal transduction of hydrogen peroxide in the cyanobacterium, Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Plant J. 49, 313–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Murata N., and Los D. A. (2006) Histidine kinase Hik33 is an important participant in coldsignal transduction in cyanobacteria. Physiol. Plantarum 126, 17–27 [Google Scholar]

- 69. Hihara Y., Kamei A., Kanehisa M., Kaplan A., and Ikeuchi M. (2001) DNA microarray analysis of cyanobacterial gene expression during acclimation to high light. Plant Cell 13, 793–806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Singh A. K., Summerfield T. C., Li H., and Sherman L. A. (2006) The heat shock response in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. Strain PCC 6803 and regulation of gene expression by HrcA and SigB. Arch. Microbiol. 186, 273–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]