Abstract

Background

Sarcoidosis is a chronic, multisystem disease characterised by non-necrotising granulomatous inflammation of unknown aetiology. Most commonly, the lungs, lymph nodes, skin and eyes are affected in sarcoidosis; however, nervous system involvement occurs in approximately 5%–15% of cases. Any part of the nervous system can be affected by sarcoidosis.

Cases

Herein we describe three unusual patient presentations of neurosarcoidosis, one with optic neuritis, a second with hydrocephalus and a third with cervical myelopathy.

Conclusions

We include pertinent details about their presentations, imaging findings, pathology, management and clinical course.

INTRODUCTION

Sarcoidosis is characterised by granulomatous nodules, which primarily affect the lungs, lymph nodes and skin.1 However, sarcoidosis is also known to affect other organs including muscles, bone, liver, spleen, nervous system, eyes and the heart, which account for its myriad of symptoms and presentations. With regard to the nervous system, neurosarcoidosis may affect any part of the central and peripheral nervous system. Approximately 5%–15% of patients with sarcoidosis have central nervous system involvement and more than 50% of patients with central nervous system involvement initially present with neurological symptoms.2–5 It may present in many forms including optic neuropathy, facial paralysis, meningitis, hydrocephalus, hypothalamic dysfunction, myelopathy, myopathy, peripheral neuropathy and encephalitis. It is a diagnosis of exclusion and is primarily seen in genetically susceptible individuals.6 Very rarely does it present in the intraventricular space or cervical spine.7,8 When it does, it can cause serious adverse outcomes such as lateral gaze palsy,9 upward gaze palsy,10 hydrocephalus11 and potential herniation12 if not diagnosed and treated early.

Increased intracranial pressure in patients with leptomeningeal spread or intraventricular involvement is a rare complication of neurosarcoidosis. Both communicating and non-communicating hydrocephalus are potential sequalae of neurosarcoidosis; in the case of non-communicating hydrocephalus, this becomes a potentially lethal phenomenon and carries the worst long-term prognosis.13,14 Patients with neurosarcoidosis affecting the cervical spine can present with upper limb radiculopathy and lower limb myelopathy.15 It can often mimic spondylotic myelopathy, which is similar to age-related changes.16 Occasionally hypesthesia and paraesthesia are present17 with motor dysfunction in over 50% of cases.18 Patients with neurosarcoidosis affecting the intraventricular space present with memory problems, confusion, nausea and speech disturbances.19 Endoscopic biopsy has been shown to be the most effective in making a clear diagnosis.20

Presence of neurological findings in patients with known sarcoidosis should prompt a work-up for neurosarcoidosis. Dubbed as the ‘great mimicker’, sarcoid is known to exhibit many symptoms, mimicking neoplastic, infectious and other inflammatory conditions thus making its diagnosis very challenging. Diagnosis of neurosarcoidosis with CT and MRI imaging is especially challenging due to non-specific signs.21 MRI with gadolinium enhancement is the imaging of choice and may aid in making the diagnosis. Occasionally, biopsy of the brain, spinal cord or meninges is performed to confirm the diagnosis.22 Here, we present three cases of neurosarcoidosis and discuss important features in relation to early diagnosis and management. Furthermore, we provide a detailed review of the literature and highlight important clinical points for consideration.

CASES

Case 1

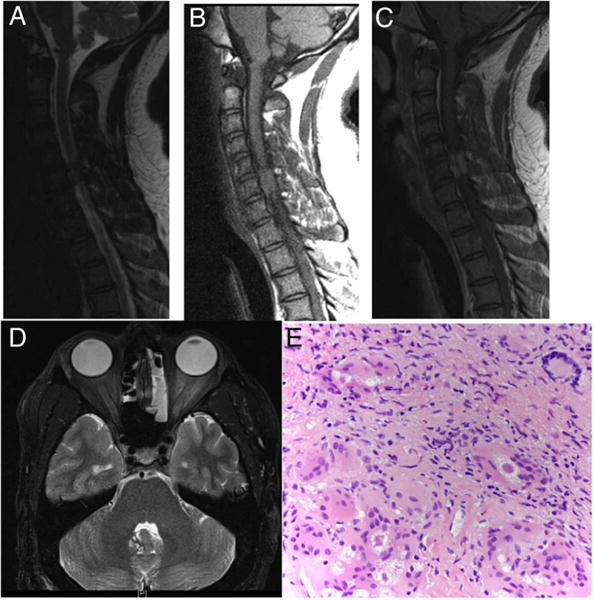

The patient is a 38-year-old African-American male who first presented for evaluation of visual deficits in autumn 2014, with sudden onset of visual loss in his left eye. He was diagnosed with optic neuritis that was temporarily relieved by steroids. In the spring of 2015, his visual deficit worsened again and was accompanied by pain. Neurology was consulted for evaluation of multiple sclerosis. At which time an MRI of his neuroaxis was done which revealed increased signal intensity on T2-weighted images in the left orbital nerve canalicular region, and in the left prechiasmatic region but no definite enhancement of the optic nerve. An enhancing mass at C5–C6 and four additional, smaller enhancing masses in the thoracic spinal canal were seen (figure 1). These appeared to be intradural, extramedullary lesions. The patient reported new onset left forearm paraesthesias. Patient underwent a unilateral C6 laminotomy with a partial C5 and C7 laminotomies for removal of the extramedullary mass. The mass was sent to pathology and found to be non-necrotising granulomatous inflammation consistent with sarcoidosis (figure 1). Patient was placed on prednisone 50 mg oral once per day for 4 weeks. He recovered well from surgery and repeat imaging 2 months following surgery showed resolution of the previously noted lesions. Of note, thoracic CT showed scattered nodular densities bilaterally but no mediastinal or hilar lymphadenopathy. Serum calcium was 9.3 (normal), serum ACE was 85 (elevated) and ACE was not detected in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

Figure 1.

Case 1: T2-weighted sagittal view demonstrated a slightly hyperintense intradural extramedullary mass at C5–C6 level (A). T1-weighted sagittal view demonstrated an isointense intradural extra-axial mass at the C5–C6 level (B). T1-weighted Gd-enhanced sagittal view demonstrated contrast enhancement of the mass (C). T2-weighted axial view of the brain shows a hyperintense mass involving the left orbital nerve canalicular region and left prechiasmatic region with sparing of the optic nerve and no enhancement of the optic nerve (D). Sections from the intradural-extramedullary mass, revealed non-necrotising granulomatous inflammation with prominent multinucleated giant cells, some of which contain asteroid bodies (original magnification ×200). Stains for acid-fast and fungal organisms (not shown) were negative (E).

Case 2

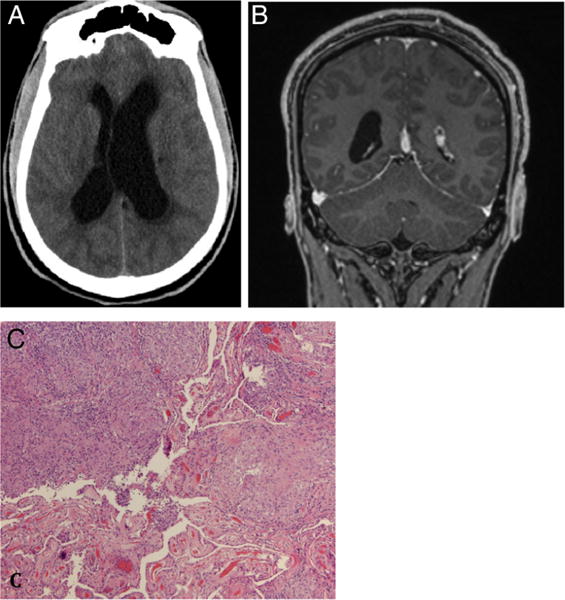

The patient is a 26-year-old African-American male who presented in spring 2015 following seizure-like activity and decreased level of consciousness associated with bowel and bladder incontinence and vomiting. A non-contrast CT of the brain in the Emergency Department (ED) revealed obstructive hydrocephalus. An MRI with and without contrast of the brain was subsequently ordered but the source of the hydrocephalus could not be determined at that time. An extraventricular drain (EVD) was placed with an opening pressure of 22 cm H2O. The patient’s intracranial pressure remained stable, the EVD was removed 1 week after placement and the patient was discharged. Notably, serum ACE was 35 (normal) and was not detected in the CSF. Serum calcium was 9.5. CT of the chest showed mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy. At his follow-up visit 1 month later, the patient reported light headedness and blurry vision with activity. A non-contrast CT of the brain revealed obstructive hydrocephalus; therefore, a ventriculoperitoneal shunt was planned along with fenestration of the septum pellucidum. Two days prior to his scheduled surgery, the patient presented to the ED confused and lethargic. Repeat CT of the brain was performed, which revealed hydrocephalus and an emergent EVD was placed (figure 2). After review of his previous MRI of the brain, it was noted that there was enhancement along the third ventricle and foramen of Monroe, though difficult to distinguish from the choroid plexus (figure 2). The patient underwent an endoscopic resection of this enhancing mass and pathology revealed non-necrotising granulomatous inflammation in the choroid plexus consistent with sarcoidosis (figure 2). Since the foramen of Monroe was widely opened, a ventriculoperitoneal shunt was not placed and the patient was started on prednisone 50 mg oral once per day for 4 weeks. Postoperative imaging revealed resolution of the hydrocephalus. One month following surgery, he reported improvement in his headaches and repeat imaging was stable with decreased size of his ventricles.

Figure 2.

Case 2: Non-contrast CT of brain axial view revealed hydrocephalus (A). T1-weighted Gd-enhanced coronal view demonstrated contrast enhancement along the third ventricle and foramen of Monroe, it was difficult to distinguish the mass from the choroid plexus (B). Sections from the intraventricular biopsy demonstrate non-necrotising granulomatous inflammation involving the choroid plexus (bottom left; original magnification ×40). As in case 1, stains for acid-fast and fungal organisms were negative (C).

Case 3

The patient is a 50-year-old Caucasian female who presented in spring of 2016 with a chief complaint of numbness in bilateral upper extremities and neck stiffness lasting 3–4 weeks. Patient also complained of clumsiness when ambulating and dropping objects from her hands. Patient initially presented to outside hospital and was transferred to our facility after a cervical intradural extramedullary spinal tumour was diagnosed. MRI of the cervical spine showed an enhancing mass extending from C1 to C3 with bilateral enhancement around the lower medulla and extensive T2 signal changes in the cord. Thoracic CT showed bilateral hilar masses, MRI of the brain was unremarkable besides redemonstrating the enhancement in and around the medulla, MRI of the thoracic spine and lumbar spine was unremarkable (figure 3). Serum ACE was 26 (normal). A lumbar puncture was performed with an opening pressure of 26 cm H2-O. Multiple sclerosis studies were performed on CSF and were found to be negative and ACE was not detected in the CSF. In addition, CSF cytology was negative for malignancy. Serum calcium was 9.2. A lymph node biopsy was performed from the hilar lymph nodes and revealed non-necrotising granuloma consistent with sarcoidosis. The patient was started on methylprednisolone and noted improvement in her symptoms after 2 days and continued to improve over her hospital course and was ambulating with minimal assistance on discharge. The patient was switched to prednisone 50 mg oral once per day for 4 weeks. Repeat MRI of the cervical spine on follow-up showed significant decrease in size of the enhanced intradural lesion.

Figure 3.

Case 3: T2-weighted sagittal view demonstrated a hyperintense intramedullary mass from C1 to C3 and around the lower medulla (A). T1-weighted sagittal view demonstrated an isointense mass from C1 to C3 (B). T1-weighted Gd-enhanced sagittal view demonstrated contrast enhancement of the intramedullary mass (C). Thoracic CT scan demonstrated bilateral pulmonary hilar mass (D). T1-weighted sagittal view 2 weeks following corticosteroid treatment showed near total resolution of the mass (E).

DISCUSSION

Neurosarcoidosis is a disease of unknown aetiology and is defined by granulomatous material with T lymphocytes and phagocytes that damage surrounding tissue.23 Neurosarcoidosis is diagnosed by the exclusion of other possible aetiologies making it difficult to detect and diagnostically challenging.24 It is commonly seen in individuals between the ages of 20 and 40, is more prevalent in African-Americans and affects women more than men.25 Importantly, in patients with no known systemic disease, a biopsy of the abnormal area may help establish the diagnosis of neurosarcoidosis. In the cases above, imaging alone was insufficient to make a diagnosis and these insufficiencies have been reported previously by Nowak and Widenka.26 For neurosarcoidosis presenting as an intradural extramedullary mass in the cervical spine, a laminectomy was performed with biopsy confirming the diagnosis and patient was subsequently treated with prednisone and his thoracic lesions resolved. Similarly, for neurosarcoidosis in the intraventricular space and diagnosis after biopsy, the patient was treated with prednisone and this mitigated the need for a ventriculoperitoneal shunt.

It is important to consider the variability in presenting symptoms. Zajicek and colleagues provided diagnostic criteria for neurosarcoidosis and categorised the findings into possible neurosarcoidosis, probable neurosarcoidosis and definitive neurosarcoidosis.27 An adaptation of the previously proposed criteria by Zajicek is described here. Possible neurosarcoidosis was defined as clinical presentation suggestive of neurosarcoidosis after alternative diagnoses have been excluded and the presence of positive nervous system histology. Probable neurosarcoidosis was defined as a clinical presentation suggestive of neurosarcoidosis with laboratory support for central nervous system inflammation, exclusion of alternative diagnoses and evidence for systemic sarcoidosis. Definite neurosarcoidosis was defined as clinical presentation suggestive of neurosarcoidosis with exclusion of other possible diagnoses and the presence of nervous system histological evidence of aroid.

In case 1, optic neuritis was the presenting symptom with subsequent paraesthesias and diffuse weakness. Optic neuritis can be the presenting symptom of sarcoidosis over 50% of the time.28 In case 2, the patient presented with symptoms associated with hydrocephalus and mass effect. When the symptoms are life threatening, such as obstructive hydrocephalus or presence of myelopathy, surgery is warranted.29

Immunosuppression has been the mainstay of treatment for neurosarcoidosis, and corticosteroids are considered first-line agents. However, not all patients will respond to corticosteroid therapy.30 In patients refractory to corticosteroids or with a contraindication to corticosteroids, alternative therapeutic agents may be considered. Methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, ciclosporin, cyclophosphamide, chlorambucil, pentoxifylline, hydroxychloroquine, thalidomide, infliximab and adalimumab have been previously used in the management of neurosarcoidosis.31 In cases of neurosarcoidosis-induced hydrocephalus, it is often necessary to use shunts or EVDs in conjunction with corticosteroid treatment.8 In cases of spinal involvement, if amenable, surgical decompression should be should be performed along with postoperative corticosteroid treatment.4 In refractory cases, radiation therapy has been used to some success in patients with pituitary and hypothalamic involvement; however, its role in the management of the many forms of neurosarcoidosis has yet to be fully explored.32,33

CONCLUSION

Neurosarcoidosis poses diagnostic challenges and potential for significant morbidity in the patients it affects. We present three cases of cervical and intraventricular neurosarcoidosis, respectively. The importance of clinical suspicion and biopsy is emphasised as well as consideration of other potentially affected organs.34 Sarcoidosis must be a diagnostic consideration in patients with unusual presentations and imaging findings. A definitive diagnosis requires a tissue biopsy and should be performed in suspected cases of sarcoidosis. Once neurosarcoidosis is diagnosed, it is important to initiate treatment and follow patients both clinically and radiographically to assess their response to therapy.

Main messages.

▸ Neurosarcoidosis can present in multiple ways and must be considered when other etiliologies have been ruled out.

▸ Definitive diagnosis must be made by biopsy.

▸ Corticosteroids are the mainstay of treatment.

Self assessment questions.

Please answer true or false to the below statements.

Sarcoidosis is a chronic, multisystem, infectious disease, characterised by non-necrotising granulomatous inflammation of unknown aetiology.

Communicating and non-communicating hydrocephalus are potential sequalae of neurosarcoidosis.

Neurosarcoidosis presenting as non-communicating hydrocephalus is usually self-limiting.

Neurosarcoidosis presenting as cervical myelopathy may require decompression to prevent further neurological deficit.

Radiological evidence and patient presentation is sufficient to confirm the diagnosis of neurosarcoidosis.

Answers.

False. Sarcoidosis is a non-infectious, inflammatory disease.

True.

False. Neurosarcoidosis presenting as non-communicating hydrocephalus is potentially life threatening and may require emergent treatment.

True.

False. Tissue diagnosis is required to confirm the diagnosis.

Acknowledgments

An American Association of Pharmaceutical Sciences Pre-doctoral Fellowship, Sigma Xi Grants in Aid of Research and American Foundation of Pharmaceutical Education Pre-doctoral Fellowship supported Brandon Lucke-Wold. Research reported in this publication was supported by the NIGMS of the National Institutes of Health under award number U54GM104942. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Contributors WR and BL has made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work or the acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data for the work; drafted the work or revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors included approve the final version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Competing interests None.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Eby SA, Buchner EJ, Bryant MG. Presumed intramedullary spinal cord sarcoidosis in a healthy young adult woman. Am Jf Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;91:810–13. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e31824121a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quenardelle V, Benmekhbi M, Aupy J, et al. An atypical form of neurosarcoidosis. Rev Med Interne. 2013;34:776–9. doi: 10.1016/j.revmed.2013.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Terushkin V, Stern BJ, Judson MA, et al. Neurosarcoidosis: presentations and management. Neurologist. 2010;16:2–15. doi: 10.1097/NRL.0b013e3181c92a72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoitsma E, Drent M, Sharma OP. A pragmatic approach to diagnosing and treating neurosarcoidosis in the 21st century. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2010;16:472–9. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e32833c86df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pawate S, Moses H, Sriram S. Presentations and outcomes of neurosarcoidosis: a study of 54 cases. QJM. 2009;102:449–60. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcp042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marnane M, Lynch T, Scott J, et al. Steroid-unresponsive neurosarcoidosis successfully treated with adalimumab. J Neurol. 2009;256:139–40. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-0077-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee JH, Takai K, Ota M, et al. Isolated neurosarcoidosis in the medulla oblongata involving the fourth ventricle: a case report. Br J Neurosurg. 2013;27:393–5. doi: 10.3109/02688697.2012.741736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim SH, Lee SW, Sung SK, et al. Treatment of hydrocephalus associated with neurosarcoidosis by multiple shunt placement. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2012;52:270–2. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2012.52.3.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walid MS, Ajjan M, Grigorian AA. Neurosarcoidosis–the great mimicker. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100:859–61. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31382-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamada H, Hayashi N, Kurimoto M, et al. Isolated third and fourth ventricles associated with neurosarcoidosis successfully treated by neuroendoscopy–case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2004;44:435–7. doi: 10.2176/nmc.44.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schlitt M, Duvall ER, Bonnin J, et al. Neurosarcoidosis causing ventricular loculation, hydrocephalus, and death. Surg Neurol. 1986;26:67–71. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(86)90066-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scott TF. Cerebral herniation after lumbar puncture in sarcoid meningitis. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2000;102:26–8. doi: 10.1016/s0303-8467(99)00066-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benzagmout M, Boujraf S, Gongora-Rivera F, et al. Neurosarcoidosis which manifested as acute hydrocephalus: diagnosis and treatment. Intern Med. 2007;46:1601–4. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.46.0126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zaarour M, Weerasinghe C, Moussaly E, et al. “The great mimicker”: an unusual etiology of cytopenia, diffuse lymphadenopathy, and massive splenomegaly. Case Rep Med. 2015;2015:637965. doi: 10.1155/2015/637965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tipper GA, Fareedi S, Harrison K, et al. Neurosarcoidosis mimicking acute cervical disc prolapse. Br J Neurosurg. 2011;25:759–60. doi: 10.3109/02688697.2010.544793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sakushima K, Yabe I, Nakano F, et al. Clinical features of spinal cord sarcoidosis: analysis of 17 neurosarcoidosis patients. J Neurol. 2011;258:2163–7. doi: 10.1007/s00415-011-6080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okamura M, Suzuki K, Kokubun N, et al. Neurosarcoidosis presenting with severe hyposmia and polyradiculopathy. Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 2013;53:821–6. doi: 10.5692/clinicalneurol.53.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Durel CA, Marignier R, Maucort-Boulch D, et al. Clinical features and prognostic factors of spinal cord sarcoidosis: a multicenter observational study of 20 BIOPSY-PROVEN patients. J Neurol. 2016;263:981–90. doi: 10.1007/s00415-016-8092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsuda R, Nishimura F, Motoyama Y, et al. A case of intraventricular isolated neurosarcoidosis diagnosed by neuroendoscopic biopsy. No Shinkei Geka. 2015;43:247–52. doi: 10.11477/mf.1436202995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoshitomi M, Uchikado H, Hattori G, et al. Endoscopic biopsy for the diagnosis of neurosarcoidosis at the fourth ventricle outlet with hydrocephalus. Surg Neurol Int. 2015;6:S633–636. doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.170466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Demir MK, Yapicier O, Onat E, et al. Rare and challenging extra-axial brain lesions: CT and MRI findings with clinico-radiological differential diagnosis and pathological correlation. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2014;20:448–52. doi: 10.5152/dir.2014.14031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kasliwal MK, Harbhajanka A, Nag S, et al. Isolated spinal neurosarcoidosis: an enigmatic intramedullary spinal cord pathology-case report and review of the literature. J Craniovertebr Junction Spine. 2013;4:76–81. doi: 10.4103/0974-8237.128536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jovicevic M, Zarkov M, Zikic TR, et al. A case of probable neurosarcoidosis presenting as unilateral ophthalmoplegia. Acta Clin Croat. 2015;54:359–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kapfhammer I, Armbruster C, Armbruster C. Neurosarcoidosis–a diagnostic pitfall with consequences. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2006;118:554–7. doi: 10.1007/s00508-006-0662-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gullapalli D, Phillips LH., II Neurosarcoidosis. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2004;4:441–7. doi: 10.1007/s11910-004-0066-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nowak DA, Widenka DC. Neurosarcoidosis: a review of its intracranial manifestation. J Neurol. 2001;248:363–72. doi: 10.1007/s004150170175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zajicek JP, Scolding NJ, Foster O, et al. Central nervous system sarcoidosis–diagnosis and management. QJM. 1999;92:103–17. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/92.2.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu X, Sun Y, Dai H, et al. Clinical analyses of sarcoidosis with ocular involvement. Zhonghua yi xue za zhi. 2014;94:3171–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nozaki K, Judson MA. Neurosarcoidosis. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2013;15:492–504. doi: 10.1007/s11940-013-0242-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stern BJ, Corbett J. Neuro-ophthalmologic manifestations of sarcoidosis. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2007;9:63–71. doi: 10.1007/s11940-007-0032-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stjepanovic MI, Vucinic VM, Jovanovic D, et al. Treatment of neurosarcoidosis–innovations and challenges. Med Pregl. 2014;67:161–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Menninger MD, Amdur RJ, Marcus RB., Jr Role of radiotherapy in the treatment of neurosarcoidosis. Am J Clin Oncol. 2003;26:e115–8. doi: 10.1097/01.COC.0000077933.69101.5D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sundaresan P, Jayamohan J. Stereotactic radiotherapy for the treatment of neurosarcoidosis involving the pituitary gland and hypothalamus. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2008;52:622–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1673.2008.02022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoitsma E, Faber CG, Drent M, et al. Neurosarcoidosis: a clinical dilemma. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:397–407. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00805-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]