Abstract

Gratitude is a central component of addiction recovery for many, yet it has received scant attention in addiction research. In a sample of 67 individuals entering abstinence-based alcohol-use-disorder treatment, this study employed gratitude and abstinence variables from sequential assessments (baseline, 6 months, 12 months) to model theorized causal relationships: gratitude would increase pre-post treatment and gratitude after treatment would predict greater percent days abstinent 6 months later. Neither hypothesis was supported. This unexpected result led to the theory that gratitude for sobriety was the construct of interest; therefore, the association between gratitude and future abstinence would be positive among those already abstinent. Thus, post treatment abstinence was tested as a moderator of the effect of gratitude on future abstinence: this effect was statistically significant. For those who were abstinent after treatment, the relationship between gratitude and future abstinence was positive; for those drinking most frequently after treatment, the relationship between gratitude and future abstinence was negative. In this preliminary study, dispositional tendency to affirm that there is much to be thankful for appeared to perpetuate the status quo—frequent drinkers with high gratitude were drinking frequently 6 months later; abstinent individuals with high gratitude were abstinent 6 months later. Gratitude exercises might be contraindicated for clients who are drinking frequently and have abstinence as their treatment goal.

Keywords: gratitude, alcohol use disorders, drinking, spirituality

1.0 Introduction

The study of gratitude and its relationship to addiction recovery has been sparse, despite anecdotal relevance in recovery circles. Gratitude is a consistent theme in Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) (AA World Services, 1953) and is central to the recovery experiences of many. Its relationship to successful recovery warrants further empirical exploration.

The fields of psychology, theology, sociology, and philosophy have made rich contributions to the knowledge base that describes and defines the complex construct of gratitude. Gratitude has been identified as central to the tenets of Judaism (Schimmel, 2004), Islam (Esposito, 2004), and Christianity (Shelton, 2004). Philosophers have pondered the elements, forms, and functions of gratitude (Kristjánsson, 2013; Manela, 2015). Gratitude has been understood as a mechanism which prompts reciprocity in gift exchange (Komter, 2004) and has been understood as essential to interpersonal bonding (Algoe, 2012; Algoe, Haidt, & Gable, 2008). Gratitude’s emotional dimensions have been noted as has its function as a moral virtue (R. A. Emmons & Shelton, 2002). Gratitude in the scholarly canon has been associated mostly with positive bio-psycho-social phenomena. Gratitude has correlated significantly with aspects of well-being such as positive affect, life satisfaction, vitality, optimism, and hope (McCullough, Emmons, & Tsang, 2002) and has been associated with constructs related to physical and mental health, such as better sleep (Mills et al., 2015), higher ratings of physical health (Hill, Allemand, & Roberts, 2013), and lower levels of depression (Lambert, Fincham, & Stillman, 2012; Mills et al., 2015).

1.1 Gratitude and its Potential to Change

Basic terms are defined here before discussing the relationship between gratitude and addiction recovery. State gratitude refers to shorter- or longer-term feelings of gratitude, thankfulness, or appreciation that arise in response to a specific event such as receiving help or assistance (McCullough et al., 2002; Solom, Watkins, McCurrach, & Scheibe, 2017; Wood, Froh, & Geraghty, 2010; Wood, Maltby, Stewart, Linley, & Joseph, 2008). Trait gratitude has been described as a stable personality characteristic, a “life orientation toward noticing and appreciating the positive” (Wood et al., 2010, p. 891). Gratitude practices are intentional activities related to “systematically paying attention to what is going right” (R. Emmons & Stern, 2013) such as making a daily list of things one is grateful for.

Could trait gratitude, by definition a stable characteristic, increase secondary to a gratitude intervention or a life-changing experience, such as getting sober? The research evidence is mixed on this question. Some studies have reported that gratitude exercises were associated with increases in trait gratitude (R. Emmons & McCullough, 2003; Froh, Sefick, & Emmons, 2008; Rao & Kemper, 2017; Redwine et al., 2016) while other studies have reported no change in trait gratitude as the result of gratitude practices (Harbaugh & Vasey, 2014; Killen & Macaskill, 2015; Krentzman et al., 2015; Toepfer, Cichy, & Peters, 2012). Could trait gratitude increase with the onset of addiction recovery, in the absence of gratitude exercises? Previous research suggests that mental illness, including addictive behavior, is associated with lower levels of gratitude and absence of mental illness with higher levels of gratitude. For example, negative relationships have been reported between gratitude and depression (Kendler et al., 2003; Van Dusen, Tiamiyu, Kashdan, & Elhai, 2015) and gratitude and post-traumatic stress disorder (Kashdan, Uswatte, & Julian, 2006; Van Dusen et al., 2015). In addition, Kendler and colleagues (2003) found that higher scores on a thankfulness variable were associated with significantly decreased odds of lifetime generalized anxiety disorder, phobia, bulimia nervosa, and most relevant to the current study, nicotine, alcohol, or drug dependence. A return to wellness such as that which attends addiction recovery therefore could be associated with more frequent state gratitude leading to increases in trait gratitude. Therefore, we might observe increases in trait gratitude pre-post substance-use disorder treatment. Thus far, only one other study has assessed the trait gratitude of individuals with alcohol use disorders pre-post treatment. The study was conducted in Poland and the time between pre and post measurement was five to seven weeks. The researcher employed the Polish version of the Gratitude Questionnaire (Kossakowska & Kwiatek, 2014); the original English version of this instrument is employed in the current study (McCullough et al., 2002). Pre-post treatment, women’s average trait gratitude increased significantly from 29.4 (SD = 6.7) to 31.6 (SD = 6.5). Men’s average trait gratitude before and after treatment was 30.2 (7.1) and 31.0 (6.4), respectively, but this difference was not statistically significant (Charzyńska, 2015). Gratitude exercises were not a component of treatment in this study yet we see increases in gratitude for women but not for men (E. Charzyńska, personal communication, December 15, 2016). Taken together, this body of work has been mixed. Trait gratitude has been observed to increase after gratitude exercises—in some but not all studies—and trait gratitude in one study has been observed to increase after addiction treatment without gratitude exercises--for women but not for men.

1.2. Gratitude and Recovery

Theoretical and empirical evidence support the supposition that gratitude positively reinforces addiction recovery once recovery is underway. Recovery might foster increasing feelings of gratitude and gratitude might in turn promote and reinforce recovery. Why might this be the case? Studies have found that quality of life improves with length of sobriety (Best et al., 2012; Laudet, Morgen, & White, 2006; McGaffin, Deane, Kelly, & Ciarrochi, 2015; Subbaraman & Witbrodt, 2014). Such improvements might naturally foster increases in frequency of state gratitude. Life improves with recovery, such improvement is recognized and appreciated, and gratitude is the natural consequence. Relief and thankfulness likely would attend the lifting of the substantial burden of addiction. Therefore, recovery itself might prompt gratitude.

Two theories provide frameworks for understanding the reverse association, that is, the ways in which gratitude might sustain a state of recovery. The first is a theory of the impact of gratitude on mood. Gratitude might shift affect from negative to positive, countering the negative mood which predominates in early recovery (Koob, 2008). Thus far, one pilot study supports this hypothesis. A randomized controlled pilot tested the effects of a 14-day gratitude exercise among individuals in treatment for alcohol use disorders and found that the practice was associated with a decrease in negative affect (e.g., feeling angry, irritated, upset) and an increase in unactivated positive affect (e.g., feeling calm, at ease, relaxed) (Krentzman et al., 2015). The second theory of gratitude’s support for recovery is a cognitive theory of the effect of gratitude on outlook. State gratitude might support and reinforce the cognitive viewpoint that life in recovery is better than life during active addiction. Kelly, Myers, and Brown (2000; 2002) argue that AA provides continual reminders of the downside of active addiction as well as the benefits of sobriety; the current study posits that gratitude might arise as a result of such reminders within or outside of AA. Thus, gratitude can arise because active addiction has ceased and gratitude can arise because good things are happening in recovery. In a pilot study, participants recovering from alcohol use disorders were asked to write about three good things that happened each day and why they happened (Krentzman et al., 2015). Participants repeatedly stated that good things happened in their lives because they were sober. Repeated assertion of the causal link between sobriety and good things should reinforce recovery.

The current study is built on the idea that gratitude and recovery mutually support, inspire, sustain, and give rise to each other. This study makes the assertion that this is a naturally occurring dynamic in addiction recovery activated with or without behaviors that would reinforce this mutual relationship, such as active gratitude practices or attending AA meetings where the frequent theme of gratitude might “teach” a grateful outlook. This study posits that increases in the frequency of experiences of state gratitude would lead over time to increases in trait gratitude and therefore a measure of trait gratitude should capture changes that attend recovery. The theories that undergird this study address the relationship between gratitude to active recovery. As such, these theories prompt investigation of how gratitude changes pre-post treatment, with treatment serving as the engine to initiate recovery, and how post-treatment gratitude supports future abstinence.

1.3 Aims of the Current Study

The current study is designed to obtain basic empirical evidence to support or refute this theory of the reciprocal relationship between gratitude and recovery by studying the relationship between gratitude and abstinence among individuals with alcohol use disorders who were newly enrolled in abstinence-based treatment at baseline. Specifically, the current study examines the correlation between gratitude and abstinence and hypothesizes that among individuals with alcohol use disorders, this relationship would be positive: abstinence would be attended by increases in wellness, and therefore gratitude would increase with abstinence. Further, the current study focuses on increases in gratitude pre-post treatment, hypothesizing that gratitude will increase as abstinence increases. Finally, gratitude six-months post-treatment is tested as a predictor of increased abstinence 12-months post-treatment. In summary, the current study seeks to gain preliminary empirical grounding of the relationship between gratitude and addiction recovery, and therefore was guided by the following a priori hypotheses: (1) the relationship between abstinence and gratitude will be positive, (2) abstinence will increase between baseline and 6-months; (3) gratitude will increase during this period; and (4) gratitude at 6 months will predict greater abstinence at 12-months.

2.0 Materials and Methods

2.1 Parent Study Characteristics

Data for the current study were drawn from a larger prospective longitudinal study of individuals diagnosed with alcohol dependence. The parent study followed 364 individuals measuring spirituality, drinking, and treatment engagement at baseline and every six months for 30 months. To be included participants had to (1) be at least 18 years of age, (2) be diagnosed with lifetime alcohol dependence, (3) have drunk alcohol within the 90 days that preceded the screening assessment, and (4) be literate in English. Participants were excluded if they were actively suicidal, homicidal and/or psychotic. Prospective participants were identified via clinical records; 77.6% of those approached subsequently enrolled. Participants provided written informed consent and were compensated at baseline and every 6 months. The study was approved by the appropriate institutional review boards.

2.2 Subset Employed for the Current Study

The current study involves 67 individuals recruited just after entry into abstinence-based outpatient substance-use-disorder treatment. Twelve-step facilitation was the primary treatment modality although motivational interviewing and cognitive-behavioral therapy were employed to a lesser degree. Gratitude practices were not prescribed by clinicians. The original protocol assessed gratitude every 6 months. However, the gratitude scale eventually was removed from the protocol to streamline the interview process. Before removal of the scale, 67 individuals were assessed for gratitude at baseline and 61 of those assessed at baseline were assessed for gratitude at 6 months.

Participants in the subset of the data employed in the current study (n=67) were 18–78 years of age (M=43.1, SD = 14.1), had 9–22 years of education (M=14.9, SD = 2.7). The majority were European-American (n=60, 89.6%). The minority (n=25, 37.3%) were female. Over one-third were married or cohabitating (n=25, 37.3%). The majority were employed (n=48, 71.6%). Respondents reported 0–15 previous treatment episodes (M=1.4, SD = 2.8) and most (n=58, 86.6%) desired abstinence as their treatment goal.

2.3 Measures

2.3.1. Gratitude

The Gratitude Questionnaire-Six Item Form (GQ-6) was employed to assess trait gratitude. A sample item is, “I have so much in life to be thankful for.” The response format ranged from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree (McCullough et al., 2002), α= .75.

2.3.2. Drinking

The TimeLine FollowBack Interview (Sobell, Brown, Leo, & Sobell, 1996; Sobell & Sobell, 1992) captured drinking data from which average percent days abstinent during the previous 90 days were calculated. Percent days abstinent was employed in this study as the measure of drinking because it assesses abstinence. The focus of the current study is the association between gratitude and recovery, and scholars have identified abstinence as a critical component of recovery (Betty Ford Institute Consensus Panel, 2007, 2009).

2.4 Research Design

This descriptive, naturalistic study employed variables from sequential assessments to model the theoretical causal structure of the association between changes in gratitude and in abstinence pre-post treatment, and the impact of post-treatment gratitude on subsequent abstinence. The study focused on three assessment waves: (1) baseline, from which demographic, abstinence, and gratitude measures were assessed; (2) the 6-month follow up, from which abstinence and gratitude assessments indicated any change after treatment; and (3) the 12-month follow up, to assess the relationship between 6-month gratitude and subsequent abstinence.

2.5 Missing Data

In this study, missing data ranged from 6.3% of cases for 6-month percent days abstinent to 13.6% of cases for 12-month percent days abstinent. Missing data for 6-month gratitude was 9.8% of cases. Those with any missing data (n=9) were compared with those without missing data (n=58) on a set of baseline demographic and clinical criteria including gratitude, percent days abstinent, age, years of education, and gender. The two groups were similar with two exceptions. Those with missing data were significantly younger (31.6 (SD = 10.0) years of age versus 44.9 (SD = 13.9), t(65) = 2.77, p < .01) and had significantly lower levels of baseline gratitude (26.7 (SD = 9.0) versus 33.8 (SD = 5.7), t(65) = 3.18, p < .01) than those who had no missing data. To adjust for differences between individuals with and without complete data, baseline gratitude and age were included as covariates in all regression analyses and will be heretofore referred to as the “study covariates.”

In the current study multiple imputation (Little & Rubin, 2002) was used to impute missing data (using the MULTIPLE IMPUTATION command in SPSS version 22). Ten imputations of all missing values were performed. Because the pattern of missing data was non-monotone, fully conditional specification was employed. In this procedure, imputed values are based on predictions from models which regress a given variable with missing data on all other analysis variables (see Little & Rubin, 2002). The diagnostic properties of the regression models underlying the multiple imputation analysis were rigorously tested as recommended by Su and colleagues (2011). This testing revealed that one case exerted undue influence on all of the underlying regression models. This case was an outlier because this person drank on 89 of the 90 days preceding the 12-month follow-up (1.11 percent days abstinent). The next closest value for percent days abstinent in the dataset at 12 months was 63.33. Therefore, this case was removed from all analyses leaving a sample size of 66 individuals.

2.6 Statistical Methods

All reported estimates and inferences employed the combining rules outlined by Little and Rubin (2002) for multiply imputed data sets. Pearson Correlations assessed the zero-order relationship between gratitude and percent days abstinent at all time points. Change in percent days abstinent and gratitude between baseline and 6 months was assessed using multiple regression as follows. A change score was calculated by subtracting the baseline value from the 6-month value. The change score was regressed on the mean-centered baseline value of the construct and mean-centered study covariates. The intercepts in these models thereby represented rate of change from baseline to 6-month follow-up for participants with average values for all covariates. Statistical significance of the intercepts would indicate that change occurred between baseline and 6-months while controlling for all of the other variables in the model.

The effect of 6-month gratitude on 12-month percent days abstinent was assessed using multiple regression as follows. Twelve-month percent days abstinent (arcsine transformed) was regressed on mean-centered 6-month gratitude and mean-centered 6-month percent days abstinent. Models controlled for age, baseline percent days abstinent, and gratitude to adjust for the levels of these constructs at baseline. All predictors were mean centered.

3.0 Results

Table 1 depicts ranges, means, standard errors, and correlations for gratitude and percent days abstinent at all time points. Baseline and 6-month gratitude correlated significantly at r = .72, p<.001, suggesting stability in the construct over time. The relationship between gratitude at baseline and 6-month percent days abstinent was positive (r = .33, p < .05). The relationship between gratitude at 6 months and 6-month percent days abstinent was also positive (r = .44, p < .01) providing partial support for the first hypothesis. There was no significant relationship between gratitude at any wave and percent days abstinent at 12 months.

Table 1.

Multiple Imputation Estimates of Descriptive Statistics and Correlations for Gratitude and Percent Days Abstinent

| Variables | Possible Range | MI-Mean | MI-Standard Error of the Mean | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Baseline Gratitude | 6–42 | 32.9 | .8 | -- | ||||

| 2. 6-Month Gratitude | 6–42 | 33.6 | .8 | .72*** | -- | |||

| 3. Baseline Percent Days Abstinent | 59.7 | 3.2 | .04 | .05 | -- | |||

| 4. 6-Month Percent Days Abstinent | 92.9 | 1.7 | .33* | .44** | .22‡ | -- | ||

| 5. 12-Month Percent Days Abstinent | 95.1 | 1.2 | .07 | .19 | .07 | .54*** | -- |

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Percent days abstinent significantly increased between baseline and the 6-month follow-up by an average of 33.2 percentage points when fixing all covariates to their means (p < .001) providing empirical support for the second hypothesis. Gratitude did not increase significantly between baseline and the 6-month follow up: fixing all covariates to their means, the coefficient for change in gratitude was .72 points but this was not statistically significant (p=.224) providing no empirical support for the third hypothesis.

Gratitude at six months had no significant association with 12-month percent days abstinent controlling for all of the covariates in the model (See Table 2, Model a) providing no empirical support for the fourth hypothesis.

Table 2.

Multiple Imputation Estimates of Main and Interaction Effects

| Main Effects - Model a

|

Interaction Effect - Model b

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MI-B | MI-SE B | 95% CI

|

MI-B | MI-SE B | 95% CI

|

|||

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||||

|

|

|

|||||||

| 6-Month Gratitude | .0022 | .0061 | −.0099 | .0142 | .0008 | .0057 | −.0107 | .0122 |

| 6-Month Percent Days Abstinent | .0062* | .0024 | .0014 | .0111 | .0103*** | .0025 | .0053 | .0154 |

| 6-Month Gratitude x 6-Month Percent Days Abstinent | .0007* | .0003 | .0001 | .0013 | ||||

Notes:

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

DV = 12-Month Percent Days Abstinent, arcsine transformed. All models included age, baseline gratitude and baseline percent days abstinent as control variables. CI = Confidence Interval. MI=multiple imputation.

3.1. Post Hoc Analyses

Because gratitude did not increase from baseline to 6 months and because 6 month gratitude did not predict 12 month drinking as hypothesized, further theorizing about the nature of the relationship between gratitude and recovery led to a post hoc analysis. In previous work, participants in recovery regularly expressed gratitude for sobriety (Krentzman et al., 2015). Perhaps gratitude for sobriety functions differently in its effects on drinking than more general trait gratitude, but the scale used to measure gratitude would not have differentiated between the two. Perhaps post-treatment gratitude has an association with future abstinence only among those who are already abstinent.

To explore this proposition, an additional model was estimated. Six-month percent days abstinent was tested as a moderator of the effect of 6-month gratitude on 12-month percent days abstinent. The interaction of these two variables was added to the original model to test the possibility of multiplicative effects of the two 6-month variables on the primary outcome above and beyond their main effects (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2002). The interaction term was found to be statistically significant (Table 2, Model b).

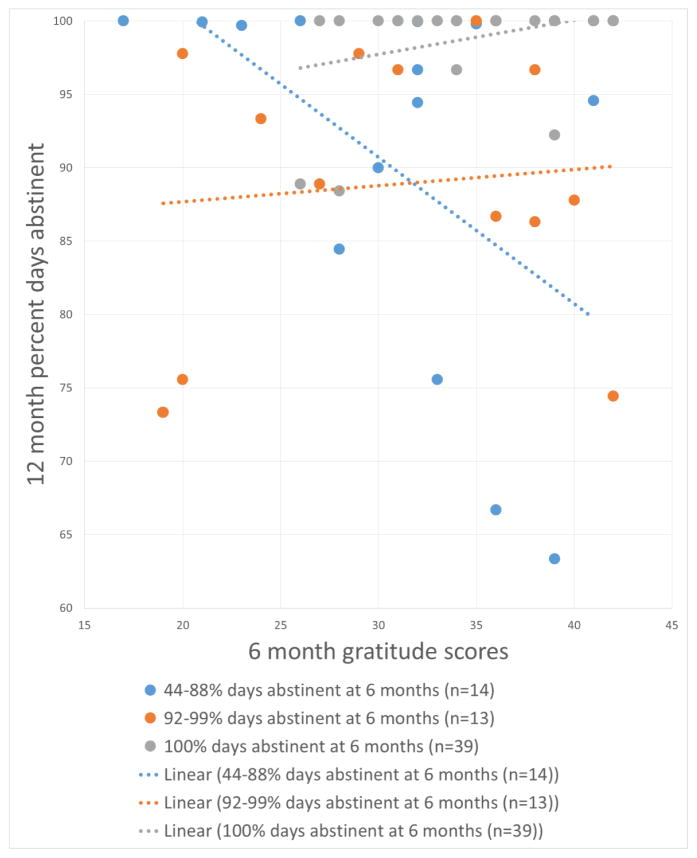

Figure 1 illustrates the significant interaction. For those who were 100% abstinent at 6 months (grey dots and trend line), higher gratitude at 6 months was associated with greater percent days abstinent at 12 months. This suggests that those with higher gratitude were more likely to remain abstinent 6 months later. For this group, the relationship between abstinence and gratitude was positive as hypothesized. However for those drinking most frequently (44–88 percent days abstinent at 6 months, blue dots and trend line) the relationship between 6 month gratitude and 12 month abstinence was negative. In this group of frequent drinkers, higher levels of gratitude at 6 months were associated with lower levels of percent days abstinent at 12 months, conversely, the lowest levels of gratitude at 6 months were associated with nearly 100% abstinence at 12 months.

Figure 1.

Decomposition of the interaction between 6-month gratitude and 6-month percent days abstinent on 12-month percent days abstinent. The relationship between 6-month gratitude and 12-month abstinence varies by abstinence status at 6 months, depicted here in three groups. For those who were 100% abstinent at 6 months, the relationship between gratitude and future abstinence is positive; for those who were drinking most frequently at 6 months, the relationship between gratitude and future abstinence is negative. Values depicted here were closest to those of the pooled imputation results.

4.0 Discussion

This study extends the current literature on gratitude and alcohol use disorders by providing partial support for the hypothesis that the relationship between gratitude and abstinence is positive. The relationship between post-treatment gratitude and abstinence 6 months later appeared positive only for those who were already abstinent. Among those who were drinking most frequently, the association between gratitude and future abstinence was negative. By highly endorsing such questionnaire items as “I have so much in life to be thankful for” and “If I had to list everything that I felt grateful for, it would be a very long list,” frequent drinkers with high gratitude seemed to be expressing not gratitude for sobriety but that life was good while drinking. Endorsement that life is good as is would offer low motivation for change. Conversely, frequent drinkers with low gratitude might have been motivated by their negative view of the status quo; for them, lower gratitude at 6 months was associated with abstinence at 12 months.

Psychological, sociological, and philosophical perspectives on gratitude have not been unilaterally positive. Emmons and Crumpler (2000) have posed the question, “Is there a negative side to gratitude?” (p. 66) suggesting that, for example, bestowing gifts and favors might further oppress those who do not have the means to reciprocate, an idea further developed by Komter (2004). Philosophers have discussed the underside of gratitude. Aristotle found gratitude faulty at the extremes: being obsequiously grateful or expressing ingratitude were both considered to be weaknesses of character (Kristjánsson, 2013). Charles M. Shelton (2004), a psychologist and Jesuit priest, wrote that gratitude’s “optimistic exuberance sometimes covers up or gives an overly optimistic interpretation of issues needing to be addressed, such as personal pathologies that are often crippling, relationships that are unhealthy, or naïve perceptions of a complex world that need reappraisal” (p. 264). Some individuals with alcohol use disorders might overlook the negative consequences of their drinking if they have the strong dispositional tendency to appreciate and notice the positive. Future research should investigate the clinical and demographic features of frequent drinkers with high trait gratitude to determine the ways in which they might differ from their peers with alcohol use disorders.

While the current study did not investigate the effects of gratitude practices, results suggest that efforts to increase gratitude among those with alcohol-use disorders who are abstinent might be beneficial but might be contraindicated among those who are drinking frequently. Previously, addictions interventionists have found that some therapeutic strategies are productive among those ready to change and counterproductive with clients who are not ready for change. For example, “decisional balance” (i.e., listing the pros and cons of change) has been shown to reduce commitment to change among those who are ambivalent. However, decisional balance reinforces the decision to change among those committed to change (Miller & Rose, 2015). The current study is the first to suggest that gratitude might function similarly. If the client does not want to change or is ambivalent about change, a gratitude practice might affirm what is good in life while currently drinking. However, if a client has made a decision to change and has thereby entered the “action” stage (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1984), then a gratitude practice should affirm changes already underway.

In this study increases in trait gratitude pre-post treatment were not observed and in Charzynska’s (2015)’s study, increases were observed among women only. Despite these results, there are theoretical and empirical grounds to suggest that gratitude should increase. Perhaps more time is needed for trait gratitude to shift with addiction recovery. Or, perhaps a measurement instrument that assesses gratitude for recovery would better access the underlying construct of interest. Also, assessing state as well as trait gratitude would be an asset in capturing the presence or absence of gratitude during addiction recovery. Trait gratitude has been assessed via established instruments (Adler & Fagley, 2005; McCullough et al., 2002; Watkins, Woodward, Stone, & Kolts, 2003); more recent work has measured state gratitude. For example, Wood and colleagues (2008) assessed state gratitude by presenting various scenarios to research participants and asking, “How much gratitude would you feel toward this person?” (p. 283). Solom and colleagues (2017) assessed state gratitude by measuring the extent to which an individual felt grateful, thankful, and appreciative in the past week.

4.1 Limitations

The administrative decision in the parent study to eliminate the gratitude questionnaire from the assessment protocol reduced the subsample and limited the selection of data analytic strategies. As one example, it was not possible to test effects of percent days abstinent at 6 months on gratitude at 12 months, as gratitude was not assessed at 12 months. Individuals in the current study were majority White and relatively highly educated. The current study examined levels of trait gratitude via a psychometric instrument. It did not assess the effects of active gratitude practices, so extrapolation about the impact of gratitude practices should be undertaken with caution. These issues underscore the current study as preliminary in nature limiting generalizability to more diverse drinkers. Further research is need to replicate these findings in larger, more diverse samples of individuals with alcohol use disorders.

Average percent days abstinent did not change significantly between 6 and 12 months. This might have suppressed the main effects of 6-month gratitude on 12-month abstinence, but the zero-order correlation between these constructs was also not statistically significant suggesting no relationship between them. The interaction of 6-month gratitude and 6-month abstinence on 12-month abstinence was statistically significant—the statistical significance of this effect was not suppressed by the lack of average change in percent days abstinent but the magnitude of the effect might have been. The positive and negative effects of gratitude on future abstinence found within the interaction between 6-month gratitude and 6-month abstinence essentially cancel each other out. This provides one explanation for why the main effect of gratitude had no relationship with 12-month abstinence.

4.2 Future Directions

There is still much we do not know about the forms and dimensions of gratitude that might change during addiction recovery. It is not clear for whom, when, or what kinds of gratitude practices are optimal for aiding recovery although research outside of the field of addiction has suggested that those with low trait gratitude at baseline have the most to gain from gratitude practices (Harbaugh & Vasey, 2014; Rash, Matsuba, & Prkachin, 2011). Qualitative studies of gratitude among individuals in recovery can be a fruitful step. The current study did not focus on the main effects of baseline trait gratitude in subsequent recovery although a positive association was found between baseline gratitude and 6-month percent days abstinent. Research on the role of baseline trait gratitude as an individual transitions from active drinking to recovery would make a useful contribution. This was a secondary data analysis and therefore time lags of 6 month’s duration were inherited. Future research should investigate changes in gratitude over both shorter and longer durations, both during and after treatment. In this study, counselors did not prescribe gratitude practices. It would be interesting to consider the impact of such practices and the impact of 12-step involvement on several forms of gratitude including state and trait gratitude as well as gratitude for sobriety.

4.3 Conclusions

For individuals with alcohol use disorders who are drinking frequently, the association between gratitude with future abstinence was negative. For individuals with alcohol use disorders who were abstinent, the association of gratitude with future abstinence was positive. Encouragement of gratitude practices for individuals with alcohol use disorders who are drinking frequently might be counterproductive. Results speak to the potential downside of certain forms of gratitude suggesting that high levels of gratitude might obscure life problems, such as risky or harmful levels or drinking, which might best be brought to light.

Highlights.

Abstinence increased pre-post treatment but gratitude did not increase

Gratitude at 6 months did not predict abstinence at 12 months

6 month abstinence moderated the effect of gratitude on future abstinence

Among the abstinent, gratitude was positively associated with future abstinence

Among frequent drinkers, gratitude was negatively associated with future abstinence

Acknowledgments

With thanks to my colleagues who provided valuable comments to drafts of this report, to Brady West for statistical consultation, and to Elizabeth A.R. Robinson for providing background about the parent study.

Role of Funding Sources

This research was supported by grants R01 AA014442 and R21 AA019723 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, National Institutes of Health, and partially by grant DA035882 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The author declares she has no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- AA World Services. Twelve Steps and Twelve Traditions. New York: AA World Services; 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Adler MG, Fagley NS. Appreciation: Individual Differences in Finding Value and Meaning as a Unique Predictor of Subjective Well-Being. Journal of Personality. 2005;73(1):79–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00305.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Algoe SB. Find, Remind, and Bind: The Functions of Gratitude in Everyday Relationships: Gratitude in Relationships. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2012;6(6):455–469. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2012.00439.x. [Google Scholar]

- Algoe SB, Haidt J, Gable SL. Beyond Reciprocity: Gratitude and Relationships in Everyday Life. Emotion (Washington, DC) 2008;8(3):425–429. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.8.3.425. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.8.3.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best D, Gow J, Knox T, Taylor A, Groshkova T, White W. Mapping the recovery stories of drinkers and drug users in Glasgow: Quality of life and its associations with measures of recovery capital: Mapping recovery journeys. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2012;31(3):334–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2011.00321.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-3362.2011.00321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betty Ford Institute Consensus Panel. What is recovery? A working definition from the Betty Ford Institute. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2007;33(3):221–228. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.06.001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betty Ford Institute Consensus Panel. What is recovery? Revisiting the Betty Ford Institute Consensus Panel Definition. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 2009;7(4):493–496. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-009-9227-z. [Google Scholar]

- Charzyńska E. Sex Differences in Spiritual Coping, Forgiveness, and Gratitude Before and After a Basic Alcohol Addiction Treatment Program. Journal of Religion and Health. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10943-015-0002-0. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-015-0002-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West S, Aiken L. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 3. Mahwah, N.J: Routledge; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Emmons RA, Crumpler CA. Gratitude as a Human Strength: Appraising the Evidence. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2000;19(1):56–69. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2000.19.1.56. [Google Scholar]

- Emmons RA, Shelton CM. Gratitude and the science of positive psychology. In: Snyder CR, Lopez SJ, editors. Handbook of Positive Psychology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Emmons R, McCullough ME. Counting blessings versus burdens: An experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84(2):377–389. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.84.2.377. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.2.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmons R, Stern R. Gratitude as a Psychotherapeutic Intervention. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2013;69(8):846–855. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22020. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito J. Islam: The Straight Path. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. 3 Rev Upd edition. [Google Scholar]

- Froh JJ, Sefick WJ, Emmons RA. Counting blessings in early adolescents: An experimental study of gratitude and subjective well-being. Journal of School Psychology. 2008;46(2):213–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2007.03.005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbaugh CN, Vasey MW. When do people benefit from gratitude practice? The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2014;9(6):535–546. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2014.927905. [Google Scholar]

- Hill PL, Allemand M, Roberts BW. Examining the Pathways between Gratitude and Self-Rated Physical Health across Adulthood. Personality and Individual Differences. 2013;54(1):92–96. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2012.08.011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB, Uswatte G, Julian T. Gratitude and hedonic and eudaimonic well-being in Vietnam war veterans. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44(2):177–199. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.01.005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Myers MG, Brown SA. A Multivariate Process Model of Adolescent 12-Step Attendance and Substance Use Outcome Following Inpatient Treatment. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors: Journal of the Society of Psychologists in Addictive Behaviors. 2000;14(4):376–389. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly J, Myers M, Brown S. Do Adolescents Affiliate with 12-Step Groups? A Multivariate Process Model of Effects. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63(3):293–304. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Liu XQ, Gardner CO, McCullough ME, Larson D, Prescott CA. Dimensions of religiosity and their relationship to lifetime psychiatric and substance use disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160(3):496–503. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.3.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killen A, Macaskill A. Using a gratitude intervention to enhance well-being in older adults. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2015;16(4):947–964. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9542-3. [Google Scholar]

- Komter A. Gratitude and Gift Exchange. In: Emmons R, McCullough M, editors. The Psychology of Gratitude. 1. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. pp. 195–212. [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF. Hedonic Homeostatic Dysregulation as a Driver of Drug-Seeking Behavior. Drug Discovery Today. Disease Models. 2008;5(4):207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.ddmod.2009.04.002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ddmod.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kossakowska M, Kwiatek P. Polska adaptacja kwestionariusza do badania wdzięczności GQ-6. = The Polish adaptation of the Gratitude Questionnaire (GQ-6) Przegląd Psychologiczny. 2014;57(4):501–512. [Google Scholar]

- Krentzman AR, Mannella KA, Hassett AL, Barnett NP, Cranford JA, Brower KJ, … Meyer PS. Feasibility, acceptability, and impact of a web-based gratitude exercise among individuals in outpatient treatment for alcohol use disorder. Journal of Positive Psychology. 2015 doi: 10.1080/17439760.2015.1015158. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2015.1015158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kristjánsson K. An Aristotelian Virtue of Gratitude. Topoi. 2013:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11245-013-9213-8.

- Lambert NM, Fincham FD, Stillman TF. Gratitude and depressive symptoms: the role of positive reframing and positive emotion. Cognition & Emotion. 2012;26(4):615–633. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2011.595393. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2011.595393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laudet AB, Morgen K, White WL. The Role of Social Supports, Spirituality, Religiousness, Life Meaning and Affiliation with 12-Step Fellowships in Quality of Life Satisfaction Among Individuals in Recovery from Alcohol and Drug Problems. Alcohol Treat Q. 2006;24(1–2):33–73. doi: 10.1300/J020v24n01_04. https://doi.org/10.1300/J020v24n01_04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. 2. Hoboken, N.J: Wiley-Interscience; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Manela T. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 2015. Gratitude. [Google Scholar]

- McCullough ME, Emmons R, Tsang JA. The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;82(1):112–127. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.82.1.112. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGaffin BJ, Deane FP, Kelly PJ, Ciarrochi J. Flourishing, languishing and moderate mental health: Prevalence and change in mental health during recovery from drug and alcohol problems. Addiction Research & Theory. 2015;23(5):351–360. https://doi.org/10.3109/16066359.2015.1019346. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rose GS. Motivational Interviewing and Decisional Balance: Contrasting Responses to Client Ambivalence. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2015;43(2):129–141. doi: 10.1017/S1352465813000878. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465813000878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills PJ, Redwine L, Wilson K, Pung MA, Chinh K, Greenberg BH, … Chopra D. The role of gratitude in spiritual well-being in asymptomatic heart failure patients. Spirituality in Clinical Practice. 2015;2(1):5–17. doi: 10.1037/scp0000050. https://doi.org/10.1037/scp0000050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente C. The transtheoretical approach: Crossing traditional boundaries of therapy. Homewood, Ill: Dow Jones-Irwin; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Rao N, Kemper KJ. Online Training in Specific Meditation Practices Improves Gratitude, Well-Being, Self-Compassion, and Confidence in Providing Compassionate Care Among Health Professionals. Journal of Evidence-Based Complementary & Alternative Medicine. 2017;22(2):237–241. doi: 10.1177/2156587216642102. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156587216642102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rash JA, Matsuba MK, Prkachin KM. Gratitude and Well-Being: Who Benefits the Most from a Gratitude Intervention?: GRATITUDE AND WELL-BEING. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being. 2011;3(3):350–369. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1758-0854.2011.01058.x. [Google Scholar]

- Redwine LS, Henry BL, Pung MA, Wilson K, Chinh K, Knight B, … Mills PJ. Pilot randomized study of a gratitude journaling intervention on heart rate variability and inflammatory biomarkers in patients with stage B heart failure. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2016;78(6):667–676. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000316. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schimmel S. The Psychology of Gratitude. 1. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. Gratitude in Judaism; pp. 37–57. [Google Scholar]

- Shelton C. The Psychology of Gratitude. 1. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. Gratitude: Considerations from a moral perspective; pp. 257–281. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell L, Brown J, Leo GI, Sobell MB. The reliability of the Alcohol Timeline Followback when administered by telephone and by computer. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1996;42(1):49–54. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(96)01263-x. https://doi.org/10.1016/0376-8716(96)01263-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell L, Sobell MB. Timeline Follow-Back. In: Litten RZ, Allen JP, editors. Measuring Alcohol Consumption. Humana Press; 1992. pp. 41–72. Retrieved from http://link.springer.com.ezp2.lib.umn.edu/chapter/10.1007/978-1-4612-0357-5_3. [Google Scholar]

- Solom R, Watkins PC, McCurrach D, Scheibe D. Thieves of thankfulness: Traits that inhibit gratitude. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2017;12(2):120–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1163408. [Google Scholar]

- Su YS, Yajima M, Gelman AE, Hill J. Multiple Imputation with Diagnostics (mi) in R: Opening Windows into the Black Box. Journal of Statistical Software. 2011;45(2):1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Subbaraman MS, Witbrodt J. Differences between abstinent and non-abstinent individuals in recovery from alcohol use disorders. Addictive Behaviors. 2014;39(12):1730–1735. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.07.010. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toepfer SM, Cichy K, Peters P. Letters of Gratitude: Further Evidence for Author Benefits. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2012;13(1):187–201. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-011-9257-7. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dusen JP, Tiamiyu MF, Kashdan TB, Elhai JD. Gratitude, depression and PTSD: Assessment of structural relationships. Psychiatry Research. 2015;230(3):867–870. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.11.036. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2015.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins PC, Woodward K, Stone T, Kolts RL. Gratitude and happiness: Development of a measure of gratitude, and relationships with subjective well-being. Social Behavior and Personality. 2003;31(5):431–452. [Google Scholar]

- Wood AM, Froh JJ, Geraghty AWA. Gratitude and well-being: A review and theoretical integration. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30(7):890–905. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood AM, Maltby J, Stewart N, Linley PA, Joseph S. A social-cognitive model of trait and state levels of gratitude. Emotion (Washington, DC) 2008;8(2):281–290. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.8.2.281. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.8.2.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]