Abstract

Background

Patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) make a unique group of strokes. Unfractionated heparin (UFH) and low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) are among the medications used for preventing blood coagulation. This study was carried out aiming at analyzing the cost effectiveness of LMWH versus UFH in hospitalized patients with stroke due to AF with respect to the Iranian population.

Methods

This randomized study was an economic evaluation of cost effectiveness with the help of the cross-sectional data of 2013–2015. In this study, 74 patients had undergone treatment in two groups, before being evaluated. Half of the patients were treated by LMWH, while the other half was treated by UFH. Effectiveness criterion was prevention of new stroke recurrence.

Results

Average medical direct costs, non-medical direct costs, and indirect costs of UFH were 110375 ± 40411$, 15594 ± 11511$, and 21723 ± 19933$, respectively. Same average medical direct costs, non-medical direct costs, and indirect costs of LMWH were 99573 ± 59143$, 9016 ± 17156$, and 10385 ± 10598$, respectively. The number of prevention of new strokes due to AF in LMWH and UFH was 2 and 0, respectively. Expected effectiveness in LMWH and UFH groups was 0.56 and 0.51, respectively. Moreover, the expected costs were 26737.61$ and 30776.18$, respectively. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio for stroke due to AF was −150, 201, 26$ per prevention of stroke recurrence (p-values ≤ 0/05).

Conclusion

The results of the cost-effectiveness analysis of LMWH versus UFH showed that LMWH is a dominant strategy for patients with stroke due to AF in Iranian population.

Keywords: Cost-effectiveness analysis, low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH), stroke, unfractionated heparin (UFH)

1. INTRODUCTION

Stroke is known as one of the main causes of death and disability worldwide [1]. It is a costly disease from the individual, family, and community perspectives [2]. An international comparison of costs for stroke disease showed that an average of 0.27% of GDP in each country and about 3% of each country's health expenditure is spent on treatment and caring of stroke disease [3].

One treatment strategy to prevent thrombosis in ischemic stroke due to atrial fibrillation (AF) is to administrate unfractionated heparin (UFH) and starting warfarin after a few days [4]. UFH anticoagulation effect can be monitored by activated partial thromboplastin time level [5]. UFH is prescribed to prevent theoretical risk of paradoxical thrombosis in patients with protein C and S deficiencies [6]. Intravenous administration of UFH can increase the duration of hospital stay and the risk of complications and nosocomial infections [7]. Clinical trials have shown that high-dose subcutaneous injection of low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH, another form of heparin) has a high level of efficiency in treatment of patients with acute thrombosis complications [8]. Subcutaneously administered of LMWH, without any need for laboratory data monitoring, makes this drug favorable for outpatient setting since it decreases costs and complications of hospital stay [9].

The efficacy, safety, and tolerability of LMWH versus UFH as bridging therapy in patients with embolic stroke due to AF were compared as the first stage of our research project. Therefore, this study was carried out to analyze the cost effectiveness of LMWH compared with UFH in hospitalized patients with stroke due to AF in Shiraz, south of Iran.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study Design

This study was randomized according to the previous study, in which equal randomization was performed using random block size of 4 (1: 1 for two groups). Randomization table was prepared by an investigator with no clinical involvement in the trial. Patients who met the inclusion criteria were enrolled in the trial according to the allocation list. Principal investigator and data analyst were blinded to the allocations. Patients were not aware which treatment strategy included the new drug [9]. In addition, this study was an economic evaluation of cost-effectiveness analysis studies as well as a survey of health system management studies carried out with the cross-sectional data of October 2013 to February 2015. In this study, using the following formula, 74 patients underwent treatment in two groups. They were then evaluated in the next stage. Half of the patients were treated by LMWH, while the other half was treated by UFH. The sample size was calculated using the following formula. Sampling method was randomized sampling. To this end, the researcher was referred to the stroke and neurology ward of Nemazee Hospital on a daily basis and evaluated stroke patients due to AF treated with UFH and LMWH. Having reached the quorum, the sample size for each group was stopped. Inclusion criteria for this study were all patients with stroke due to AF who were at least 18 years old. Their physicians decided to use either LMWH or UFH for treating them.

α = %5

β = %20

2.2. Data Collection

2.2.1. Costs

Costs data were collected through interviews with patients with stroke due to AF and their companions using data collection forms, including the medical direct costs, non-medical direct costs, and indirect costs for three months following the injection of medications. In addition, indirect costs were estimated using human capital approach. As far as research perspective is concerned, this study accounted for Iranian population. To have an international perspective, the costs were converted from Iranian Rails (IRR) into international dollars ($Int).

2.2.2. Effectiveness

Effectiveness data were collected by a check list, including demographic data, admission date, date of starting anticoagulation, and statues of the patient after three months (new stroke recurrence). In this study, effectiveness criterion was prevention of new stroke recurrence. Therefore, the results of this study were expressed as cost per new stroke prevention. Finally, the researchers called patients or their companions after three months and evaluated the statues of patients for the new stroke.

In the next stage, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was calculated and sensitivity analysis was carried out. In this study, the decision tree model was used. Finally, SPSS16 software was used to analyze the demographic data. In addition, Tree Age 2011 was used to draw a decision tree diagram, the ICER analysis of medications in both the groups, probabilistic sensitivity analysis, and a tornado diagram. Data were analyzed using SPSS 18 and descriptive statistics, t-test, and one-way ANOVA test. A significance level of 5% was considered.

3. RESULTS

According to the findings of the previous study, 67.9% in group LMWH were 45–75-year old, while 64.8% in group UFH were 35–75-year old. In addition, 32.4% in group LMWH and 43.2% in group UFH were male, while 67.6% in group LMWH and 56.8% in group UFH were female [9].

3.1. Cost

Table 1 shows the cost of different components due to UFH and LMWH in patients with stroke due to AF. As shown in Table 1, UFH medical direct costs, non-medical direct costs, and indirect costs are more than those of LMWH.

Table 1. Cost Components of Treated Patients with Stroke Due to AF with UFH and LMWH.

| Strategy | Costs Components ($) | Mean±SD |

|---|---|---|

| UFH | Medical direct costs | 1103.75±404.11 |

| Medication | 128.87±133 | |

| Hospitalization | 399.52±244.12 | |

| Sonography | 26.43±14.62 | |

| Radiology | 2.83±4.14 | |

| MRI | 13.92±28 | |

| Physiotherapy | 26.84±84.25 | |

| Laboratory Tests | 52.92±45.39 | |

| CT-SCAN | 336.97±32.74 | |

| Visits | 67.80±39.31 | |

| Auxiliary Nurse | 369.90±289.84 | |

| Non-medical direct costs | 155.94±115.11 | |

| Traveling | 22.66±23.56 | |

| Lodging | 89±70.30 | |

| Auxiliary Equipment | 44.25±107.54 | |

| Indirect costs | 217.23±199.33 | |

| Lost productivity due to illness | 155.94±115.11 | |

| Time spent by the patient’s accompany | 153.71±202.76 | |

| Total | 1477±497.91 | |

| LMWH | Medical direct costs | 995.73±591.43 |

| Medication | 174.35±257.69 | |

| Hospitalization | 154.12±44.26 | |

| Sonography | 32.13±18.54 | |

| Radiology | 5.5±20.98 | |

| MRI | 18.71±44 | |

| Physiotherapy | 58.15±209.77 | |

| Laboratory Tests | 60.63±63.93 | |

| CT-SCAN | 43.21±37.17 | |

| Visits | 78.96±59.88 | |

| Auxiliary Nurse | 347.69±257.46 | |

| Non-medical direct costs | 90.16±171.56 | |

| Traveling | 29.96±71.86 | |

| Lodging | 35.32±28.96 | |

| Auxiliary Equipment | 24.87±99.24 | |

| Indirect costs | 103.85±105.98 | |

| Lost productivity due to illness | 32.80±64.27 | |

| Time spent by the patient’s accompany | 71±79.26 | |

| Total | 1189.75±684.77 |

3.2. Effectiveness

The outcomes of the effectiveness of the studied medications are shown in Table 2 with respect to the prevention of new stroke due to AF. According to the data, the number of prevention of new strokes due to AF in LMWH is more than that of UFH. The number of prevention of new strokes due to AF in LMWH and UFH were 2 and 0, respectively.

Table 2. Comparison Between Effectiveness of UFH and LMWH in Treated Patients with Stroke Due to AF.

| Medication | DAYS | Total 37 | Total 37 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Effectiveness Endpoint | LMWH | UFH | |

| New Ischemic Stroke | 90 | 0 | 2 |

| Death Related To Stroke | 90 | 5 | 11 |

3.3. Cost-Effectiveness

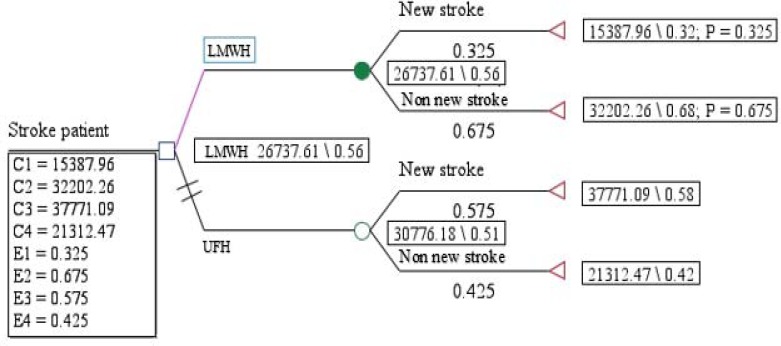

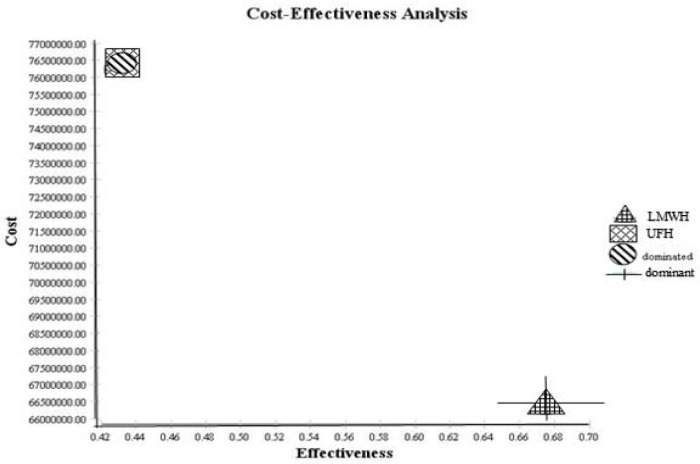

The outcomes displayed in Figure 1 showed that the expected effectiveness in LMWH and UFH groups were 0.56 and 0.51, respectively, and the expected costs in LMWH and UFH groups were 26737.61$ and 30776.18$, respectively. Therefore, as shown in Figure 2, LMWH is more cost effective than UFH (dominant).

Figure 1. Decision tree outcomes of UFH versus LMWH. The outcomes decision tree shows that the expected effectiveness in LMWH and UFH groups were 56 and 51, respectively. Moreover, the expected costs were 26737.61$ and 30776.18$, respectively.

Figure 2. Cost-effectiveness analysis outcomes of UFH versus LMWH. UFH is dominated and LMWH is dominant. Therefore, as shown, LMWH with more effectiveness and less cost is more cost effective than UFH (dominant).

3.4. Sensitivity Analysis

Sensitivity analysis helps the researcher to recognize what parameters are critical in an economic evaluation result, determination of main points of an economic evaluation, and their use against uncertainty [10]. In this study, one-way sensitivity analysis and probabilistic sensitivity analysis were done.

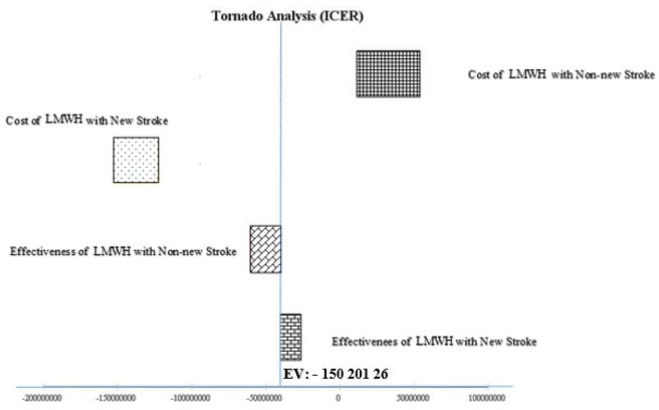

In Figure 3, all parameters were increased to 20%. We also investigated how changes in model parameters would affect the total case averted using one-way sensitivity. Our results showed that changes in most of the input parameters had a few effects on the outcome. Some averted cases were, especially, high sensitivity to the cost of LMWH with non-new stroke and low sensitivity to effectiveness of LMWH with new stroke. The ICER remained −150, 201, 26$ per effectiveness (p-values ≤ 0/05).

Figure 3. Results of one-way sensitivity analysis (tornado diagram) are presented. All parameters are increased by 20%. It was also investigated how changes in model parameters affected the total case averted using one-way sensitivity. The results show that changes in most of the input parameters have a partial effect on the outcome. Some averted cases were high sensitivity to the cost of LMWH with non-new stroke and low sensitivity to effectiveness of LMWH with new stroke. The ICER remained −150, 201, 26$ per effectiveness.

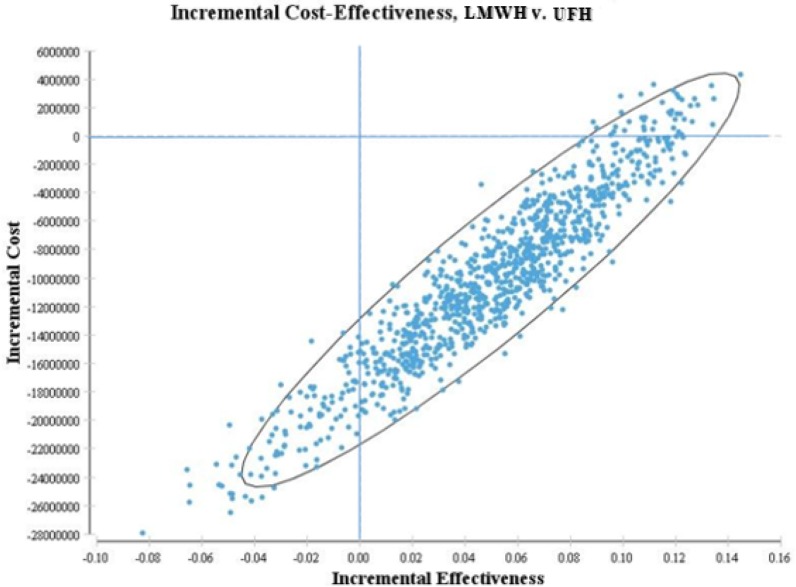

Incremental cost-effectiveness plane in Figure 4 shows Monte Carlo estimations of incremental costs as well as the benefits of using LMWH for stroke prevention compared with UFH. For each of 10,000 iterations, values for parameters were randomly assigned based on their distributions and an ICER was calculated. LMWH was found to be a dominant strategy (less costly and more effective) in 97% of the simulations.

Figure 4. Incremental cost-effectiveness plane is presented. Incremental cost-effectiveness plane shows the Monte Carlo estimator of incremental costs and benefits of using LMWH for stroke prevention compared with UFH. For each of 10,000 iterations, values for parameters were randomly selected from their distributions and an ICER was calculated. LMWH was found to be a dominant strategy (less costly and more effective) in 97% of the simulations.

4. DISCUSSION

The results of this study show that known LMWH with two preventions of new stroke, compared with UFH with zero case of new stroke, is a more effective strategy. In the study conducted by Weinberg et al. [11], the mean total costs of LMWH ($2.24±8) were lower than those of UFH [11]. This is consistent with the results of this study. In the studies of Burleigh et al. and Pineo et al., the mean of medication cost for those treated with LMWH was more than UFH for each patient. This is in agreement with the findings of this study [12–14]. In the study by Danish et al. [15], LMWH led to a decrease in DVT incidence significantly and showed only 1% of cerebral hemorrhage due to AF in patients. The results of the study by Aminmansour et al. [16] showed that LMWH was more effective and safer than UFH in prophylaxis for DVT in patients with brain tumor who underwent craniotomy. The results of all the presented studies were consistent with those of this study. In the study of Denas and Pengo [17], thrombocytopenia occurred due to UFH in 2%–5% of UFH patients. However, in the study of Martel et al. [18], its prevalence was lower (about 1% in LMWH patients). This is in agreement with the results of this study. In the study of Weinberg et al. [11], LMWH was associated with lower total inpatient costs of care than UFH for preventing VTE in hospitalized patients who were at risk [11]. Furthermore, in the study of Argenta et al. [19], the treatment of VTE with LMWH led to more cost saving in a large teaching hospital located in southern Brazil compared with UFH as a more effective alternative. In [14], the preferred use of LMWH over UFH for the prevention of VTE after acute ischemic stroke may have led to reduced VTE rates and concomitant cost saving in clinical practice.

As far as sensitivity analysis is concerned, the most important parameter, which had more substantial influence, was the cost of LMWH with non-new stroke cost. The effectiveness of LMWH with a recurrence of stroke had the minimum effect. The ICER for stroke due to AF was −150, 201, 26$ per prevention of new stroke recurrence.

There are limitations to our study which need to be considered when interpreting results. First limitation is the low number of referred patients to the hospital. Furthermore, the researchers were forced to extend their research to solve this problem. Finally, coordination for attending this study wards was time consuming.

5. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, LMWH is a safe and efficient alternative to UFH. The results of the cost-effectiveness analysis of LMWH versus UFH showed that LMWH was a dominant strategy for patients with stroke due to AF from Iranian subjects’ perspective.

However, we cannot generalize these results to other countries certainly due to differences in the costs covered by insurance organizations, the patients’ ability to pay, and the incidence and prevalence of stroke disease.

Implications for Policy Makers

The results of this study are recommended to be used by decision makers to determine how much money should be spent on stroke due to AF and can act as a starting point for including an economic evaluation approach in policy making in Iran. Improved understanding of the economic cost of stroke due to AF and the major determinants of costs help to inform the authorities and motivate decisions that can reduce the national burden of this disease. In this study, the Iranian patients’ perspective was used. It is suggested that further prospective studies should be conducted by the Ministry of Health Perspectives to have a concrete estimation of the treatment costs and to investigate the effects of treatment with medications on the patient’s quality of life.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Acknowledgment

This research was performed by Mr. Jamshid Bahmei in partial fulfillment of the requirements for certification as an MSc in Health Administration School at Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran. This paper was adopted from the proposal number 93–7013 approved by Vice-Chancellor for Research Affairs of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences. The authors would like to thank Namazi Hospital and the patients who participated in this study for their assistance in spite of their bad physical and emotional condition.

REFERENCES

- Borhani-Haghighi A, et al. Hospital mortality associated with stroke in Southern Iran. Iran J Med Sci. 2013;38(4):314–320. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strong K, et al. Preventing stroke: saving lives around the world . Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(2):182–187. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70031-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evers SM, et al. International comparison of stroke cost studies. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2004;35(5):1209–1215. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000125860.48180.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessler BS, Kent DM. Controversies in cardioembolic stroke. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2015;17(1):1–12. doi: 10.1007/s11936-014-0358-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baglin T, et al. Guidelines on the use and monitoring of heparin. B J Haematol. 2006;133(1):19–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tait R, et al. Prevalence of protein C deficiency in the healthy population. Thromb Haemost. 1995;73(1):87–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saviteer SM, et al. Nosocomial infections in the elderly: increased risk per hospital day. Am J Med. 1988;84(4):661–666. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(88)90101-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolovich LR, et al. A meta-analysis comparing low-molecular-weight heparins with unfractionated heparin in the treatment of venous thromboembolism: examining some unanswered questions regarding location of treatment, product type, and dosing frequency. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(2):181–188. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feiz F, et al. Study of the efficacy, safety and tolerability of low-molecular-weight heparin vs. unfractionated heparin as bridging therapy in patients with embolic stroke due to atrial fibrillation. J Vasc and Interv Neurol. 2016;9(1):35–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPake B, et al. Health Economics: An International Perspective. Routledge; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg RM, et al. Cost implications of using unfractionated heparin or enoxaparin in medical patients at risk for venous thromboembolic events. P AND T. 2006;31(6):322. [Google Scholar]

- Burleigh E, et al. Thromboprophylaxis in medically ill patients at risk for venous thromboembolism. Am J Health Sys Pharm: official journal of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. 2006;63(20 Suppl 6):S23–S29. doi: 10.2146/ajhp060390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pineo G, et al. Economic impact of enoxaparin after acute ischemic stroke based on PREVAIL. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost: official journal of the International Academy of Clinical and Applied Thrombosis/Hemostasis. 2011;17(2):150–157. doi: 10.1177/1076029610389026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pineo G, et al. Economic impact of enoxaparin versus unfractionated heparin for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in patients with acute ischemic stroke: a hospital perspective of the PREVAIL trial. J Hosp Med: an official publication of the Society of Hospital Medicine. 2012;7(3):176–182. doi: 10.1002/jhm.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danish SF, et al. Prophylaxis for deep venous thrombosis in craniotomy patients: a decision analysis. Neurosurgery. 2005;56(6):1286–1292. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000159882.11635.ea. discussion 92–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aminmansour B, et al. Comparing the effect of unfractionated heparin and low molecular weight heparin in preventing of deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis after craniotomy in patients with brain tumor. J Shahr Univ Med Sci. 2013;15(5) [Google Scholar]

- Denas G, Pengo V. Current anticoagulant safety. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2012;11(3):401–413. doi: 10.1517/14740338.2012.668524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martel N, et al. Risk for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia with unfractionated and low-molecular-weight heparin thromboprophylaxis: a meta-analysis. Blood. 2005;106(8):2710–2715. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argenta C, et al. Short-term therapy with enoxaparin or unfractionated heparin for venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients: utilization study and cost-minimization analysis. Value Health. 2011;14(5):S89–S92. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2011.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]