ABSTRACT

Epigenetics is involved in the altered expression of gene networks that underlie insulin resistance and insufficiency. Major genes controlling β-cell differentiation and function, such as PAX4, PDX1, and GLP1 receptor, are epigenetically controlled. Epigenetics can cause insulin resistance through immunomediated pro-inflammatory actions related to several factors, such as NF-kB, osteopontin, and Toll-like receptors. Hereafter, we provide a critical and comprehensive summary on this topic with a particular emphasis on translational and clinical aspects. We discuss the effect of epigenetics on β-cell regeneration for cell replacement therapy, the emerging bioinformatics approaches for analyzing the epigenetic contribution to type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), the epigenetic core of the transgenerational inheritance hypothesis in T2DM, and the epigenetic clinical trials on T2DM. Therefore, prevention or reversion of the epigenetic changes occurring during T2DM development may reduce the individual and societal burden of the disease.

KEYWORDS: Bioinformatics, epigenetics, inflammation, type 2 diabetes, transgenerational epigenetics, translational medicine

Introduction

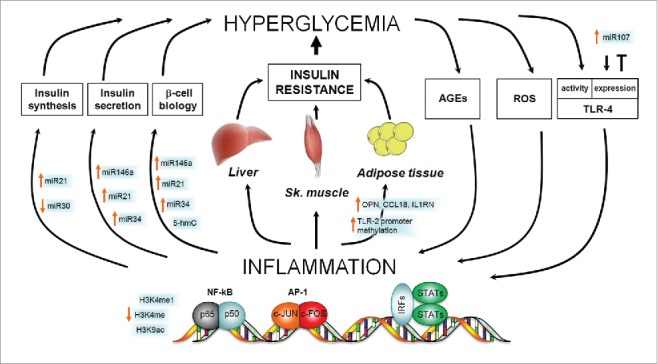

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a well-known multifactorial disease associated with aging and characterized by chronic hyperglycemia due to decreased insulin secretion, increased insulin resistance, or both.1 Chronic hyperglycemia causes serious damage to vital organs, such as heart and kidneys, and diabetic patients are at increased risk of atherosclerosis with its major consequences: coronary heart disease, peripheral arterial disease, and cerebrovascular disease.1-3 Insulin resistance in liver, skeletal muscle, and adipose tissue challenges pancreatic β-cells to produce more insulin until a progressive β-cell failure takes place and hyperglycemia gets markedly worse.4 Inflammation, sustained by the innate immune response, has been recognized as an important factor contributing to the onset and development of diabetes. As depicted in Fig. 1, hyperglycemia can trigger inflammation, which, in turn, can worsen hyperglycemia in a sort of vicious cycle.5

Figure 1.

Epigenetic contribution to the vicious cycle between hyperglycemia and inflammation in the onset of T2DM. Hyperglycemia, the hallmark of T2DM, causes systemic low-grade inflammation by different routes including production of ROS and AGEs and overexpression of TLR-4. Inflammation, in turn, favors the development of hyperglycemia by acting both on pancreatic β-cells (where it negatively regulates insulin synthesis, secretion, and the overall cell biology) and on insulin-targeted tissues, i.e., liver, skeletal muscle, and adipose tissue (where it promotes insulin resistance). The figure highlights the epigenetic contributions to all the mentioned pathways by indicating the increase or decrease of different epigenetic mediators/modifications. Where no epigenetic change is reported, there is no evidence of it in the literature. AGEs, Advanced glycation end products; AP-1, Activator Protein 1; NF-kB, Nuclear Factor Kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; IRFs, Interferon regulatory transcription factors; ROS, Reactive Oxygen Species; STATs, Signal Transducers and Activators of Transcription; OPN, osteopontin; CCL18, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 18; IL1RN, Interleukin 1 Receptor Antagonist; TLR, Toll-like receptor.

Despite the continuous progress in the hormone-replacement therapy or in the insulin secretion/sensitivity stimulating treatments, the societal burden of this still spreading common disease is enormous. Indeed, almost 400 million people had diabetes in the year 2013 worldwide, and, in 2035, nearly 600 million people will be affected with such an invalidating and life-threatening disease.6 Therefore, the identification of better preventive and curative strategies is urgently needed and a deeper epigenetic insight offers a promising opportunity to improve the quality of life of diabetic patients.7

Since epigenetic changes are reversible, preventing or reverting those occurring in T2DM is a realistic possibility to slow down or revert the worldwide increase of the incidence and prevalence of T2DM. Therefore, we here discuss the most recently evaluated potential epigenetic drugs and their possible application in novel anti-diabetic treatments. Finally, we present the most relevant ongoing or completed clinical trials looking at the role of epigenetics in diabetes.

The epigenetic contribution to the onset of T2DM

Epigenetic mechanisms

Epigenetics is a genomic control mechanism resulting from changes in the structure of chromatin without alterations in DNA sequence, which mediates the genomic response to external stimuli by regulating gene silencing or activation. Alterations in this mechanism can lead to pathological dysfunctions.8,9 In the present work, we focus on the 3 major categories of epigenetic mechanisms: DNA methylation, posttranslational histone modifications (PTHMs), and RNA-based mechanisms. These mechanisms are involved in the altered pattern of gene expression that underlies the progressive insulin resistance and insulin insufficiency of T2DM (Fig. 1).

DNA methylation represents a major epigenetic mechanism that modifies accessibility to gene promoters, thus causing transcriptional repression. It consists in the binding of a methyl group to the 5′ position of cytosine residues in a dinucleotide Cytosine-phosphate-Guanine (CpG) by the DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs, including DNMT1, DNMT3A, and DNMT3B). Beside DNMTs, demethylases of the 10–11 translocation (TET) family of DNA dioxygenases (TET1/2/3) also control the methylation status of the genome, by removing the methyl group from the methylated cytosines.10 S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) is the donor of the methyl group in the DNMT-catalyzed reactions, while Fe(II)-, α-ketoglutarate- (α-KG), ascorbate-, and O2 are the cofactors of the TET-catalyzed oxidation of 5-methylcytosine (5mC) to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC). In contrast with methylation, demethylation of DNA usually activates transcription.

PTHMs include acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and SUMOylation of specific amino acid residues of histones. PTHMs alter chromatin condensation and, as a result, gene activation, gene silencing, or both are induced. While acetylation of histone lysine residues increases chromatin accessibility and activates gene expression, the final effect of histone methylation varies according to the specific methylated residue and the number of added methyl groups. Histone acetylation and deacetylation are catalyzed by 2 classes of enzymes, histone acetyl transferases (HATs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs), respectively.11 The coordinate regulation of HATs and HDACs establishes the level of histone acetylation and, hence, contributes to the regulation of gene expression.

In addition to biochemical modifications of DNA and histones, noncoding RNAs can also regulate gene expression by influencing the protein biosynthetic machinery at the posttranscriptional and translational level. Here, we report on microRNAs (miRNAs), small RNA molecules of 21 to 23 nucleotides, and long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs, typically longer than 200 nucleotides) that could have an important role for β-cell development, as well as for insulin biosynthesis and secretion. miRNAs reduce stability or inhibit translation of target transcripts by binding to their 3′-untranslated regions (UTRs). Interestingly, many genes can be targeted by a single miRNA, and a single gene can be targeted by many miRNAs. lncRNAs are expressed in a tissue- and time-specific fashion and consist of different types of functional RNAs that comprise enhancer-associated RNAs (eRNAs), sense- and anti-sense-lncRNAs, and intergenic-lncRNAs. They are able to recruit DNMTs and histone modifiers to their target genes and, particularly eRNAs, facilitate promoter-enhancer looping, thus promoting the expression of nearby genes.12 Although there is evidence of regulation of islet-specific gene expression by lncRNAs, their role in pancreas development and β-cell function awaits definitive experimental proofs.13

β-cell development and function

Pancreatic β-cells are the central players in glycemic homeostasis because they produce insulin, the only hormone capable of lowering high blood glucose levels. Remarkably, the extent of insulin secretion is proportional to glycemia. In fact, the higher the glycemia, the higher the transport of glucose within the β-cell through the glucose transporter 2. Higher intracellular glucose concentration induces the glycolytic pathway and, hence, the ATP/ADP ratio increases. The binding of ATP to the K+IR6.2 pore-forming subunit of the K-ATP channel closes the channel itself. The consequent depolarization of the plasma membrane opens the voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel, thus causing an increased concentration of cytosolic free Ca2+, which, in turn, triggers insulin secretion.14 Nowadays, the knowledge of this chain of events within the β-cell is guiding much of the research of anti-diabetic therapies and highlights the crucial nodes where epigenetic mechanisms may be involved.

Several studies report that the mass and volume of β-cells are reduced by about 30 to 60% in type 2 diabetic patients, thus creating the generalized consensus on the central role of the β-cell functional decline in the onset of T2DM.15,16 Pathological modifications of the β-cell epigenome can cause β-cell insufficiency by impairing the maintenance of the differentiated, functional state of these cells.17 Indeed, there are master genes responsible for the differentiation of pancreatic α- and β-cells, and epigenetic mechanisms can alter the physiologic and balanced differentiation of the common precursor cells, both during developmental stages and adult life.18 Therefore, when genes inducing β-cells are expressed and genes inducing α-cells are inactivated, β-cell identity is preserved and diabetes avoided. For example, the Paired box 4 (PAX4) gene, which is necessary for the formation of mature β-cells, is hypermethylated and silenced in islets from patients with T2DM.19,20 Vice versa, Arista-less-related homeobox (ARX), a master gene for α-cells, is normally methylated and repressed in pancreatic β-cells by DNMT1 with concomitant preservation of β-cell identity.21 Therefore, it has been proposed that β-cell identity depends on the epigenetically controlled antagonistic activities of PAX4 and ARX, but the fine tuning mechanisms are still unclear.21

Beside passive demethylation (inhibition of DNMTs), active demethylating mechanisms involving TET enzymes can also be involved in the correct development of pancreatic islets.10 A relatively recent study on heterozygous miR-26a transgenic mice showed reduced expression of TET2 during islet postnatal differentiation and increased postnatal islet cell number.22 In addition to DNA methylation, histone modifications can also be manipulated to influence β-cell mass. The number of insulin-producing β-cells is increased in HDAC5 and 9 knockout mice; on the contrary, HDAC4 and HDAC5 overexpression in pancreatic explants leads to a decrease of insulin-producing β-cells.23

Recently, a role for lncRNAs in pancreas development and function has been hypothesized, given the evidence so far accumulated: lncRNAs can recruit DNA and histone modifiers to regulatory genomic regions; they are expressed in human and mouse pancreatic islets of Langerhans; and they are developmentally regulated.12 Moreover, some diabetic patients presented dysregulated expression of several lncRNAs in their pancreatic islets and, intriguingly, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) linked some genetic variants of lncRNAs with susceptibility to metabolic disorders and T2DM.24,25 It is also noteworthy that some lncRNAs, such as growth arrest-specific transcript 5 (GAS5) and metastasis-associated adenocarcinoma transcript 1 (MALAT1), have been related to T2DM and to the regulation of human islets, respectively.26 On this basis, it is likely that manipulating the levels of lncRNAs may be useful in treating T2DM and other metabolic disorders.

Once the β-cell is correctly differentiated, its core business is to produce insulin. The pancreatic and duodenal homeobox factor 1 (PDX1) is the principal transcription factor responsible for the expression of the insulin gene; it is required for hyperglycemia-dependent insulin gene expression, recruits HAT p300 to the insulin promoter and causes hyperacetylation of histone H4.27,28 Conversely, under low glucose conditions, PDX1 is associated with HDACs, such as HDAC1 and HDAC2, thus inhibiting insulin gene transcription. These findings clearly illustrate the role of epigenetics in the dynamic regulation of insulin gene transcription in response to glucose concentrations.

The final step of the β-cell activity may also be influenced by epigenetic modifications. In fact, the incretin hormone, glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP1), increases insulin secretion from β-cells through the GLP1 receptor (GLP1R). An increase of DNA methylation of 12 CpGs at transcription start sites of the GLP1R gene was observed in T2DM human pancreatic islets.29 This epigenetic modification, established by DNMT1, DNMT3A, and DNMT3B, leads to the reduction of GLP1R expression.29 The possibility to control the expression of GLP1R by epigenetic intervention could be complementary to the recently FDA-approved treatment of T2DM with lixisenatide, a GLP1R agonist.30 Insulin secretion in pancreatic islets is dependent also upon mitochondrial function. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1 α (PGC1α) is a transcriptional co-activator and master regulator of mitochondrial genes. PGC1α promoter is hypermethylated in human diabetic islets, thus resulting in lower levels of PGC1α with consequent impairment of insulin secretion.31

Basic and clinical research is aiming at establishing novel anti-diabetic therapy based on the protection, replacement, and regeneration of β-cells. Cell therapy is a developing field with vast potential for clinical intervention in diabetes and many other diseases.32,33 Functional β-like cells, have been recently obtained in vitro from human adipose tissue mesenchymal stem cells and from foreskin fibroblasts, although the most convenient sources are adipose, skin, or blood cells.34-36

However, these artificially generated β-like cells do not completely recapitulate the phenotype and functions of an original β cells, thus reducing the therapeutic efficacy. Second, it needs to be ascertained whether, after transplantation, reprogrammed β-like cells survive and maintain the differentiated phenotype long enough to warrant good quality to the patient's life. To reduce cell death, transplanted cells must be sufficiently vascularized to receive optimal oxygen and nutrient supply. To let the cells survive until well-vascularized, encapsulation devices have been produced with built-in oxygen supply.37 Depending on the encapsulation device, reprogrammed cells can be transplanted under the skin, into the peritoneal cavity, the omental pocket, or intravenously.38 Although few phase I and IIa clinical trials are still ongoing or have been completed, metabolic control and survival time of transplants are still not quite satisfactory.39

The epigenetic link between immunity and insulin resistance

Insulin resistance, a central determinant of T2DM, is the insufficient metabolic response of target tissues to insulin stimulation and is associated with several pathological conditions or prolonged anti-inflammatory treatments including obesity, infections, polycistic ovary, lipodistrophy, and steroid therapy. A physiologic condition such as pregnancy is also a risk factor for insulin resistance. The most metabolically relevant tissues that develop insulin resistance are liver, skeletal muscle, and adipose tissue (Fig. 1). The major consequence of liver insulin resistance is an abnormally elevated hepatic glucose production (HGP) that is not regulated accordingly to glycemia. HPG, which is primarily due to gluconeogenesis but also to inhibition of glycogen synthesis, prominently contributes to diabetic hyperglycemia. Skeletal muscle is a major determinant of energy expenditure in physically active organisms. It disposes primarily of glucose and fatty acids to generate sufficient amount of ATP to support its contractile activity. Consistently, it is a principal target of insulin that allows glucose to pass from blood into muscle cells. Therefore, insulin resistance of skeletal muscle is central to the development of T2DM. Insulin resistance in adipose tissue is mainly related to an excess of body fat content, which occurs in overweight and obese people. Obesity is a major risk factor for T2DM and is characterized by ectopic fat accumulation, enhanced lipolysis, and secretion of inflammatory cytokines by enlarged and supernumerary adipocytes. These factors promote insulin resistance both at the systemic and adipose tissue level, thus causing T2DM.

Are there distinct pathways that promote insulin resistance according to the specific associated condition? Is there a common pathogenic denominator? Here, we review a key factor of insulin resistance, the innate immune system, with a particular focus on the related epigenetic mechanisms. The innate immune system is directly involved in inflammation that is present in almost all the pathological conditions reported above. In particular, mast cells, macrophages, granulocytes, dendritic cells, and natural killer cells, the pillars of the innate immune response, elicit the inflammatory response by secreting an array of molecular mediators including histamine, interleukins, TNF-α, interferon-γ, and leukotrienes and other eicosanoids, such as prostaglandins. Hyperglycemia can trigger inflammation, which, in a kind of vicious cycle, can contribute to the development of insulin deficiency or insulin resistance (Fig. 1).40 Recently, evidence began accumulating regarding the epigenetic mechanisms underlying the immunological basis of diabetes and inflammation.

As demonstrated in endothelial cells and peripheral blood cells, high glucose levels modify methylation and acetylation of the p65 promoter, thus upregulating its expression and activating the pro-inflammatory pathway of NF-kB (Fig. 1).41,42 Activation of the NF-kB pathway, in turn, induces monocytes/macrophages and endothelial cells production of several cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6, and adhesion molecules, such as vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1).41,42

The association of diabetes, inflammation, and epigenetic changes has been reported also in humans. A recent study on adipose tissue from monozygotic twins discordant for T2DM (diabetics vs. non-diabetics) reported increased expression of inflammatory genes, such as secreted phosphoprotein (SPP)1 (also known as osteopontin, OPN), chemokine (C-C motif) ligand (CCL)18 and IL1RN, in association with variations of global and localized DNA methylation.43 Moreover, the methylation of 7 CpGs in the promoter of the gene coding for the inflammatory molecule Toll-like receptor (TLR)-2 was significantly lower in T2DM patients compared with controls, and this difference was associated with marked variation in the composition of gut microbiota.44

Inflammation has also been recognized as the pathogenic link between obesity and T2DM. Indeed, it is remarkable that obese individuals are not all alike in terms of susceptibility to metabolic diseases and, hence, cardiovascular risk.45 When visceral adipose tissues of 7 severely obese men with and without metabolic syndrome were compared by pathway analysis of differentially methylated genes, the most significant differences were related to genes encoding cell membrane components, and genes controlling immunity, cell cycle regulation, and inflammation.46

As stated above, hyperglycemia can stimulate inflammation and the latter can facilitate diabetes onset and progression (Fig. 1). Indeed, inflammation induces a specific miRNA pattern in primary cultures of human adipocytes. This effect might link obesity-induced inflammation and miRNA expression in β-cells, which, in turn, can influence functionality, insulin exocytosis, and apoptosis of the same cells.47-49 Since miR-21, miR-34a, and miR-146a are involved in such events, they could represent novel biomarkers for β-cell failure elicited by pro-inflammatory cytokines, thus providing a valuable opportunity for translational application.50 Additional clinical relevance is attributed to miR-30d as novel potential epigenetic drug for diabetes because it preserves mouse β-cells against TNF-α-induced suppression of insulin expression and signaling.51

Alternatively, the main target organs of insulin, namely liver, skeletal muscle, and adipose tissue might be also the targets of inflammatory pathways that could promote insulin resistance by means of epigenetic modifications (Fig. 1). As for adipose tissue, the first evidence relates to the discovery that TNF-α strongly hampers insulin sensitivity in fat and dates back to 1993.52 Ten years later, adipose tissue-infiltrating macrophages were recognized as the source of TNF-α and following studies identified raised influx of inflammatory cells into mouse adipose tissue as being responsible for obesity-associated insulin resistance.53,54 The most overexpressed gene in adipose tissue of diabetic twins was SPP1, which encodes the inflammatory cytokine osteopontin, and osteopontin engages macrophages into adipose tissue and stimulates T-cell proliferation during inflammation (Fig. 1).43 Epigenetics could be extremely important also in the inflammatory response of the hypertrophic adipose tissue in obese people. Remarkably, lean and obese individuals present differentially expressed miRNAs in their adipose tissue. A recent study in human macrophages and adipocytes has shown that a group of miRNAs regulates the expression of the inflammatory chemokine (CC motif) ligand-2 (CCL2).55 eRNAs have also been shown to regulate the expression of inflammatory genes, as in the case of the chemokine CCL5 in macrophages; remarkably, CCL5 regulates inflammatory pathways in adipose tissue.56 Interestingly, excessive adipose tissue also promotes liver insulin resistance, and this crosstalk may be due to the overexpression of MEG3, a lncRNA. In fact, in high-fat diet-fed and ob/ob mice, upregulation of MEG3 enhances hepatic insulin resistance by increasing the expression of FoxO1.57

Interestingly, TET-mediated DNA hypomethylation might be important in the so-called “metabolic memory,” which is responsible to mediate the negative effects of hyperglycemia on diabetes complications, even after an acceptable glycemic control is pharmacologically re-established in diabetic patients.58 More importantly, since the activation of TET enzymes depends upon the activity of the poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) enzyme, PARP inhibition in such patients is now a novel candidate therapeutic possibility to halt, or even revert, the progression of diabetic complications.

Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance of T2DM

An exciting and rapidly evolving field, which might be relevant to the onset of T2DM, is transgenerational epigenetics, which is the transfer of epigenetic marks from one generation to the other. This transfer may affect several generations. It is becoming appreciated that epigenetic signatures can be inherited not only by daughter cells during mitosis, but also when gametes form, during meiosis. While the first mechanism underlies epigenetic inheritance, the second defines and allows transgenerational epigenetics.59,60 Metabolic disorders, including diabetes, can be dependent on altered epigenetic reprogramming in utero.61 On the contrary, transgenerational effects are responsible for epigenetic changes also in later progenies that have not been exposed to the starting environmental stimulus. Interestingly, both F1 and F2 offspring of protein-restricted pregnant rats present high blood pressure and endothelial dysfunction, thus suggesting a transgenerational epigenetic inheritance from the F0 to the F2 generation.62 However, due to the novelty of this area of research, transgenerational epigenetic inheritance is still strongly debated.63

The relationship between very early pre-natal life and metabolic risk, recognized in the seminal work of Barker and colleagues, has led to the formulation of the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) hypothesis. According to DOHaD, the risk of developing cardiovascular and metabolic diseases, including insulin resistance and T2DM, is increased by early environmental stimuli, such as intrauterine poor nutrition and growth resulting in low birth weight.64,65 An increased metabolic risk due to an adverse intrauterine environment has also been observed in animal models with epigenetic changes in fetal tissues.66

Another maternal condition, which can transfer epigenetic information to the fetus, is gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM). The risk of developing T2DM later in life is 7 to 8-fold higher in women with GDM and their offspring, and is associated with several epigenetic modifications.66,67

Despite several studies provided compelling evidence that parental exposure to environmental triggers may have consequences on the following generations, the hypothesis that epigenetic mechanisms are responsible for the transgenerational inheritance of diabetes risk is still far from being demonstrated. Nevertheless, in the near future, it might be possible to hinder the unrestrained global spreading of diabetes, by preventing or reverting the occurrence of epigenetic diabetogenic changes in parental or even grandparental generations.

The bioinformatics approach to study the role of epigenetics in T2DM

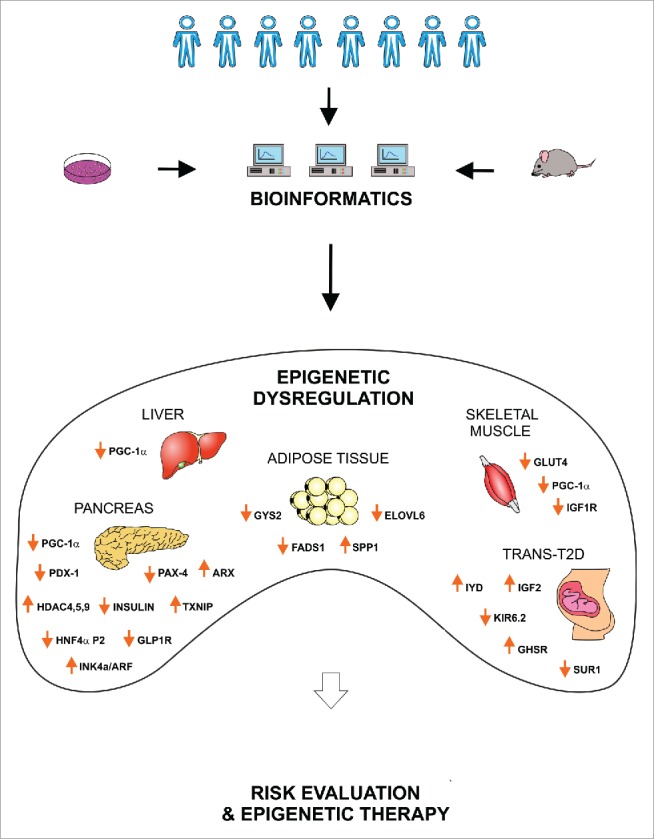

Bioinformatics mines information from large biologic data sets; this information can be then integrated and analyzed at higher complexity levels, thus allowing a deeper insight into biologic phenomena that can be translated to clinical practice, particularly to establish novel and more efficacious therapies (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Potential clinical relevance of epigenetics in T2DM. Clinical analysis and in vitro/in vivo studies provide large amount of data linking genetics, epigenetics and T2DM. Bioinformatics supports the management and interpretation of such complex information, drawing a comprehensive picture of the epigenetic dysregulation causing T2DM. This knowledge will allow a precise evaluation of the individual T2DM risk and to establish novel epigenetic therapies for diabetic patients. PGC1α, Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma, Coactivator 1 α; PDX1, Pancreatic And Duodenal Homeobox 1; PAX-4, Paired Box 4; ARX, Aristaless Related Homeobox; HDAC, Histone Deacetylase; TXNIP, Thioredoxin Interacting Protein; HNF4α, Hepatocyte Nuclear Factor 4, α; GLP1R, Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 Receptor; INK4a/ARF, Cyclin-Dependent Kinase Inhibitor 2A; GYS2, Glycogen Synthase 2; FADS1, Fatty Acid Desaturase 1; SPP1, Secreted Phosphoprotein 1 (osteopontin); ELOVL6, ELOVL Fatty Acid Elongase 6; GLUT4, Glucose Transporter Type 4; IGF1R, Insulin-Like Growth Factor 1 Receptor; IYD, Iodotyrosine Deiodinase; IGF2, Insulin-Like Growth Factor 2; KIR6.2, Inward Rectifier K(+) Channel Kir6.2; GHSR, Growth Hormone Secretagogue Receptor; SUR1, Sulfonylurea Receptor 1.

Hereunder, we summarize some studies to underline the importance of bioinformatics in T2DM research and clinical care, and report the most recent applications of bioinformatics tools on this complex disease, with a focus on epigenetics.

In the study by Liu et al., genomic, transcriptomic, genealogical, and phonemic data were collected from T2DM and healthy subjects. Whole-genome scale gene expression profiles were evaluated and the functional analysis of the differentially expressed genes was performed by means of Gene Ontology (GO) approach. As result, authors found that the regulation of cell proliferation is the most common process associated to T2DM. Moreover, the integration of gene expression data with clinical information led to the construction of a discriminate model with >95.1% accuracy in identifying healthy, pre-diabetic, and T2DM people.68

An interesting bioinformatics research applied a Bayesian regression analysis on a protein domain-domain interaction network to rank candidate domains for human complex diseases.69 Authors, by analyzing the Pfam, UniProt, DOMINE, InterDom, and OMIM databases, were able to identify associations between protein domains, genes, and T2DM.70 Moreover, factor and partial least square models have been applied on mass spectrometry lipid profiling data and on microarray data for the combined analysis of gene expression and lipid content in T2DM.71 This study allowed the identification of specific lipids and pathways associated with this disease.

The application of MPINet, an accurate network-based method for the analysis of metabolite pathways, to data set from T2DM patients allowed the identification of novel pathways associated to the disease.72 MPINet identified steroid hormone biosynthesis, mitochondrial fatty acid elongation, and glycerophospholipid metabolism as possible novel pathways influencing lipid metabolism in T2DM.72 Furthermore, a metabolic study on humans showed the association of 94 metabolites from different body fluids with T2DM.73 However, an important limitation of the current metabolomics technology concerns the restricted number of metabolites that can be identified.

An epigenetic study on 7 families identified age-associated differential methylation of T2DM susceptibility loci by means of positional density-based clustering algorithm, and online tools as FatiGO, KEGG, and GO. Authors mapped age-related epigenetic ‘hot-spots’ in genomic regions controlling fat cell fate and insulin production.74

Another study analyzed the epigenetic bases of T2DM by means of network-based approaches relating DNA methylation, chromatin modifications, and gene expression with T2DM.75 As result, it has been demonstrated that the variance in gene expression observed in human islet tissue from T2DM patients was due to specific epigenetic modifications.75

Besides, T2DM has been associated to the expression of specific mRNAs and miRNAs by applying several bioinformatics tools, such as functional enrichment analysis, gene set enrichment analysis, gene set analysis, and the VENNY software to microarray data.76 Recently, an interesting bioinformatics procedure allowed the identification of SNPs in miRNA binding sites associated with T2DM.77 In particular, several resources, such as dbSNP databases, GWAS, KEGG, miRNA target site databases, and Galaxy tools were used.77 As result, 119 SNPs, located in 18 genes involved in pathways linked to T2DM, were identified in the binding regions of 268 different miRNAs.

Two consortia have been created to generate, collect, and share human epigenetic data in public databases: NIH Roadmap Epigenomics Mapping Consortium and National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) ENCODE consortium. The NIH consortium is based on next-generation sequencing technologies and collects information on DNA methylation, histone modifications, chromatin accessibility, and small RNA transcripts in stem cells and tissues from normal subjects. The NHGRI consortium aims at identifying and characterizing functional elements and dynamic DNA methylation patterns related to regulatory elements in the human genome sequence. These consortia will allow the definition of an epigenetic map of human cells. In the following years, more and more databases with epigenetic information from diabetic and non-diabetic subjects will be built up.

Despite the vast amount of data already available and the complexity of the ‘omic’ sciences, biomedical research could further benefit from a much wider pool of data. Indeed, all the information from almost 400 million T2DM patients worldwide is not present in public databases. However, such a massive data collection and sharing would require highly standardized procedures for each phase of the entire process ranging from sample preparation to data digitalization.

We speculate that bioinformatics will promote a deeper comprehension of the molecular mechanisms underlying T2DM and, therefore, will supply fundamental information for the identification of pre-diabetic and T2DM patients, the discovery of effective drug targets, the generation of specific drugs, and for monitoring the efficacy of treatments.

Clinical trials update on epigenetics and T2DM

In Table 1 we report the studies related to T2DM and epigenetics generated from the website https://clinicaltrials.gov/. All the reported clinical trials aim either at elucidating the role of epigenetic changes in the onset, development and complications of T2DM or at establishing epigenetic markers that could predict the risk of getting T2DM and the response to anti-T2DM therapies. In particular, one current clinical trial (NCT01726491) evaluated the role of DNA methylation in insulin resistance. Another clinical trial (NCT00510380) investigated whether intrauterine growth restriction induced epigenetic changes in fetal tissues that could predispose to the metabolic syndrome in adulthood. The study NCT01663298 hypothesized that a difference exists in methylation levels of the fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2) gene in healthy, smoking, and diabetic patients that could interfere with wound healing. The trial NCT01479933 investigated the epigenetic effects of vitamin D supplementation on vitamin D metabolism genes and on the expression of genes involved in glucose/insulin metabolism. However, among the 14 trials listed in Table 1, only 3 have been completed, and there are no published results yet that deal with the investigated epigenetic aspects. This fact highlights the complexity of epigenetic analysis that goes together with the increasing scientific interest in the field.

Table 1.

Clinical trials of epigenetics and diabetes.

| NCT number | Conditions | Purpose | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| NCT01726491 | T2DM, obesity w/o T2DM | To investigate the role of DNA methylation in insulin resistance by analyzing skeletal muscle and whole blood. | Recruiting |

| NCT02869659 | Obesity, pre-diabetes | To examine the effects of weight loss on the methylation and transcriptional profile of cholesterol metabolism gene network in monocytes and adipocytes and the longitudinal relationship between these modifications and glycemic improvements. | Not yet recruiting |

| NCT02316522 | T2DM | To study the epigenetic contribution to the pathophysiology of diabetic nephropathy by assessing monocyte DNA methilation and urinary miRNAs. | Active, not recruiting |

| NCT02048839 | T2DM, obesity, metabolic syndrome | To determine the long-term effectiveness of a lifestyle intervention in high risk women and their offspring in reducing the incidence of T2DM and cardiovascular disease, in preventing obesity, in modifying genetic and epigenetics markers. | Recruiting |

| NCT01911104 | T2DM | To identify factors that prevent certain individuals from receiving the beneficial effects of exercise, by measuring the maximal capacity for mitochondrial ATP synthesis, to evaluate the change in in vivo and in vitro mitochondrial function, and to analyze the relationship between the basal promoter methylation status of key genes involved in fuel metabolism and known to be activated by exercise in skeletal muscle tissue and cells and the exercise-induced response in ATP synthesis. | Recruiting |

| NCT01782105 | Gestational diabetes, excessive weight gain during pregnancy | To determine whether the adoption of healthy lifestyles in pregnancy is associated with epigenetic changes that influence the levels of adipokines and glucose regulation during pregnancy and in newborns. | Completed |

| NCT00510380 | Fetal growth retardation | To discover if a baby with restricted growth in the womb is subject to specific fetal programming through epigenetic changes that predispose to the metabolic syndrome (diabetes, hypertension, heart disease) in adulthood. | Completed |

| NCT02450097 | T2DM, obesity | To investigate in subjects with and w/o T2DM the effect of calorie restriction on risk markers for cardiovascular disease and certain cancers, on peptides regulating glucose metabolism, and on DNA epigenetic effects. | Recruiting |

| NCT01663298 | Diabetes, smoking | The investigators hypothesize that the methylation status of FGF2 gene can affect the levels of FGF2 secreted during wound healing phase after dental implant surgery. | Recruiting |

| NCT02298790 | Overweight, obesity, pre-diabetes | To understand the connection between people's eating habits and the risk for developing diabetes, obesity, and CVD, by performing a series of primary and secondary outcome measures including epigenetic markers. | Recruiting |

| NCT01479933 | Pre-diabetes, overweight, obesity | To investigate the effects of vitamin D administration on glucose metabolism and epigenetic changes of vitamin D-related genes in pre-diabetic, overweight/obese, vitamin D-deficient, 60 or more year old men. | Completed |

| NCT02459106 | T2DM | To evaluate the effect of fat tissue-released miRNA on skeletal muscle and if abnormal fat tissue-released miRNA contributes to insulin resistance in obese individuals. | Recruiting |

| NCT02383537 | Pregnancy Diabetes | To study the effect of miRNA, fat tissue and insulin resistance on the pathophysiology of diabetes during pregnancy. | Not yet recruiting |

| NCT02011100 | T2DM, metabolic diseases, CVD | To identify miRNAs associated with carnosine action, because they could be predictors of successful anti-T2DM therapy | Ongoing, but not recruiting |

The list is extracted from ClinicalTrials.gov .The studies with unknown status are not reported in the table. Abbreviations: NCT: ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier number;

T2DM: Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus; w/o: without; FGF2: fibroblast growth factor 2; CVD: cardiovascular disease. The phase of the study of the reported trials is not available.

Potential epigenetic drugs and related clinical trials

Looking for novel therapies to treat T2DM, the possibility of exploiting the reversibility of epigenetic changes for normalizing glucose metabolism has been entertained. Indeed, a great variety of small molecules with epigenetic and anti-diabetic activity have been described in recent years.78 These drugs, or potential new drugs, can be classified according to their epigenetic effects and have been generically named epigenetic drugs (or epidrugs). Presently, inhibitors of most of the enzymes responsible for epigenetic modifications are known and many of them are undergoing intense investigations. As far as chromatin modifications, here we focus on histone acetyltransferase inhibitors (HATi), histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACi), and HDAC activators; as far as interference with RNA-based mechanisms, we report on miRNA inhibitors (Table 2). In this section, as in the previous one, we searched for clinical trials exclusively using the website https://clinicaltrials.gov/.

Table 2.

Clinical trials of potential epidrugs for the treatment of diabetes.

| Drug | Conditions | Purpose | Status | NCT number | Phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HDACa: | Gestational Diabetes | To determine if resveratrol supplementation preserves β cell function and insulin sensitivity in postpartum women following a first diagnosis of gestational diabetes. | Recruiting | NCT01997762 | Phase 4 |

| Resveratrol | T2DM | To examine, for the first time in humans, the effect of 12 weeks of oral resveratrol treatment on skeletal muscle SIRT1 expression in 10 patients with T2DM in a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind fashion. | Completed | NCT01677611 | Phase 1 |

| T2DM | To evaluate the effect of resveratrol on the glycemic variability in individuals with T2DM that are not controlled with metformin. | Recruiting | NCT02549924 | Phase 2 | |

| T2DM | To test the hypothesis that resveratrol (90 mg/day and 270 mg/day for one week each) could have favorable effects on endothelial function in patients with T2DM. | Completed | NCT01038089 | N/A | |

| T2DM | To demonstrate the safety and tolerability of resveratrol therapy in overweight adolescents to decrease liver fat and improve insulin sensitivity to prevent T2DM. | Recruiting | NCT02216552 | Phase 2 | |

| Metabolic SyndromeNAFLD | Phase 2Phase 3 | ||||

| T2DM | To investigate if resveratrol supplementation can improve overall and muscle-specific insulin sensitivity in T2DM patients. | Active, not recruiting | NCT01638780 | N/A | |

| T2DM | To investigate the effect of resveratrol on inflammatory mediators in diabetic patients. | Recruiting | NCT02244879 | Phase 3 | |

| Inflammation | |||||

| Insulin Resistance | |||||

| Obesity | To compare the health benefits of both resveratrol and Calorie Restriction (CR) and to determine if resveratrol mimics some of the health benefits shown with CR. | Completed | NCT00823381 | N/A | |

| Metabolic Syndrome | |||||

| T2DM | |||||

| Resveratrol | Obesity | To prove that resveratrol, administered to subjects with the metabolic syndrome, under controlled conditions of weight stability, common diet, and strict compliance with the study drug, could improve the symptoms of the metabolic syndrome decreasing the chance of developing diabetes or heart disease. | Recruiting | NCT01714102 | Phase 2 |

| Insulin Resistance | |||||

| Metabolic Syndrome | |||||

| T2DM | To investigate the effects of short-term supplementation (3 days) of 2 combinations of polyphenols epigallocatechin-gallate (E) + resveratrol (R) on energy expenditure and substrate metabolism in overweight subjects. Results: for the first time, it was demonstrated that combined supplementation of E+R significantly increased fasting and postprandial energy expenditure accompanied by improved metabolic conditions. | Completed100 | NCT01302639 | N/A | |

| Obesity | |||||

| Insulin Sensitivity | |||||

| Metabolic Syndrome | To test if the benefits of resveratrol, described in animal models, can be translated to patients with metabolic syndrome who display high markers of oxidative stress. | Recruiting | NCT02219906 | Phase 3 | |

| Metformin | T2DM | To evaluate the effects of metformin plus colesevelam combination therapy compared with metformin HCl alone on percent change of Hemoglobin A1C when given as initial therapy in drug-naïve subjects and on percent change in LDL in pre-diabetic subjects. Results: the combination therapy with metformin plus colesevelam improved the atherogenic lipoprotein profile of patients with early T2DM by significantly reducing LDL. | Completed95 | NCT00570739 | Phase 3 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | |||||

| Pre-diabetes subjects | |||||

| Healthy subjects | To evaluate by change from baseline in Hemoglobin A1C values whether treatment of metformin affects compliance of treatment in subjects with T2DM. | Terminated | NCT01817777 | Phase 4 | |

| Gestational Diabetes | Since it is not known whether exposure to metformin in utero has late metabolic effects on the child, the aim of this study was to investigate metabolism (oral glucose tolerance test, insulin, plasma lipoproteins, inflammation markers as well as body composition by DEXA (dual energy X-ray absorption) and magnetic resonance imaging) in 9 year-old children whose mothers used either metformin of insulin during pregnancy. | Recruiting | NCT02417090 | N/A | |

| Metformin | Polycystic Ovary Syndrome | To evaluate if the treatments by acupuncture and metformin have the potential to restore epigenetic and molecular alterations in target tissues (endometrial-, adipose-, and skeletal muscle tissue) and thus to prevent the development of T2DM. | Recruiting | NCT02647827 | Phase 2 |

| Insulin Resistance | |||||

| Hyperandrogenism | |||||

| HDACi: | Healthy subjects | To evaluate the effect of sodium phenylbutyrate on fatty acid-induced impairment of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in healthy males. | Completed | NCT00533559 | Phase 4 |

| Sodium phenylbutyrate | |||||

| Healthy subjects | To test if sodium phenylbutyrate is effective in people who are obese with insulin resistance and high lipids. | Completed | NCT00771901 | N/A | |

| HATi: | T2DM | To evaluate the effects of curcumin on serum levels of lipid profile and inflammatory markers in patients with T2DM. | Recruiting | NCT02529969 | Phase 2 |

| Curcumin | Phase 3 | ||||

| T2DM | To evaluate the effects of curcumin supplementation on serum levels of glycemic control, lipid profile, inflammatory markers, and oxidative stress in patients with T2DM. | Recruiting | NCT02529982 | Phase 2 | |

| Phase 3 | |||||

| Healthy subjects | To study the effect of curcumin on postprandial plasma glucose, insulin levels and glycemic index in 14 healthy subjects. Results: curcumin increased postprandial serum insulin levels without affecting plasma glucose levels in healthy subjects. | Completed84 | NCT01029327 | N/A | |

| T1DM | To evaluate the effects of a novel multi-component dietary supplement (vitamins, turmeric root extract) on the visual function and retinal structure of patients with diabetes with and without early diabetic retinopathy. Results: the multicomponent nutritional formula provides clinically improvements in visual function and peripheral neuropathy in patients with diabetes improving glycemic control. | Completed85 | NCT01646047 | N/A | |

| T2DM | |||||

| Non-proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy | |||||

| DNMTi: | T2DM | To prevent major cardiovascular events (heart attack, stroke, or cardiovascular death) in adults with T2DM using intensive glycemic control, intensive blood pressure control, and multiple lipid management. | Completed | NCT00000620 | Phase 3 |

| Hydralazine | Atherosclerosis Cardiovascular Diseases | ||||

| Hypercholesterolemia | |||||

| Hypertension | |||||

| Coronary Disease | |||||

| T2DM Hypertension | To study the effect of blocking the renin angiotensin system on urinary free light chain excretion as compared with urine microalbumin creatinine ratio in subjects with T2DM. The long-term goal is to assess urinary free-light chains as a biomarker of earlier detection of kidney function impairment in subjects with diabetes mellitus. | Recruiting | NCT02046395 | Phase 4 |

The list is extracted from ClinicalTrials.gov. The studies with unknown status are not reported in the table. Abbreviations: NCT: ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier number; HDACa: HDAC activators; HDACi: histone deacetylase inhibitors; HATi: histone acetyltransferase inhibitors; DNMTi: DNA metyltransferase inhibitors;T2DM: Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus; T1DM: Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus; NAFLD: Non Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease; LDL: low-density lipoprotein; N/A, not available.

Histone acetyltransferase inhibitors

HATi are considered as new potential epidrugs to treat diabetes. For instance, garcinol, from garcinia fruit rinds, is a potent HATi and PCAF and p300 are among its targets.79 Indeed, garcinol was able to reduce inflammatory proteins in retinal Müller glia grown at high-glucose concentration, thus suggesting that garcinol may play a role in the prevention of diabetic retinopathy by eliciting epigenetic changes.80

Anacardic acid, which is present in cashew nuts, can inhibit several HATs, including PCAF, Tip60 and p300;81 in addition, anacardic acid can also promote glucose uptake by myotubes through the activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and uncouple rat liver mitochondria, thus potentially contributing to enhanced glycolysis and glucose uptake.81

Curcumin, the active compound of Curcuma longa (turmeric), a plant of the ginger family, has caught attention as a potential epidrug for diabetes, given its hypoglycemic, hypolipidemic, and epigenetic effects in various rodent models.82 Curcumin has DNA hypomethylating activity and influences both histone acetylation and miRNA expression. Curcumin could ameliorate glucose metabolism, and could also prevent diabetic complications by increasing HDAC-2 and decreasing p300-HAT in human monocytes with a consequent reduction of NF-kB signaling and vascular inflammation.83 In Table 2, we report a completed and published clinical trial (NCT01029327) demonstrating that curcumin increases postprandial serum insulin levels without affecting plasma glucose levels in healthy subjects.84 Additionally, another completed and published clinical trial (NCT01646047) studied the effects of a novel multi-component dietary supplement (vitamins, turmeric root extract, and so on) on the visual function and retinal structure of diabetic patients with and without early diabetic retinopathy. The results of the study showed that the multicomponent nutritional formula ameliorates glycemic control, visual function, and peripheral neuropathy in patients with diabetes (Table 2).85

Histone deacetylase inhibitors

HDACi have a potential anti-diabetic activity due to their anti-inflammatory effect, enhancement of insulin sensitivity/secretion, induction of β-cell differentiation, and prevention of inflammatory damage of β-cells.86 In vitro evidence demonstrated that the HDACi Trichostatin A could restore Pdx-1 expression, thus preventing the onset of diabetes.86 Besides, class I HDAC selective inhibitors, such as MS275, can ameliorate insulin sensitivity, and reduce hyperglycemia and body weight in obese, diabetic mice. These effects are probably due to the increased activity of transcription factors and co-factors that regulate mitochondrial function, such as PGC-1α and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ), and to the expression of genes involved in glucose and lipid metabolism, such as glucose transporter GLUT4.87

Interestingly, butyrate, a short-chain fatty acid present in dairy products, but also endogenously produced by gut microbiota, can increase insulin sensitivity and energy expenditure in mice.88 Butyrate is an HDACi that also inhibits AMPK in muscle and activates PGC-1α in brown adipose tissue. The anti-obesity and anti-diabetic effects of butyrate in high-fat-fed mice were also confirmed in a later study, which showed that this short-chain fatty acid also modulates the adaptation of skeletal muscle mitochondria to excessive dietary fats. Noteworthy, butyrate exerted these effects by epigenetically altering gene expression, through repositioning the −1 nucleosome.89 Two completed clinical trials (NCT00533559 and NCT00771901) evaluated the efficacy of sodium phenylbutyrate in the treatment of diabetes and obesity, respectively, confirming its beneficial effect in humans (Table 2). Moreover, MC1568, a selective class IIa HDACi, induced endocrine differentiation in pancreas by amplifying the β/δ lineage through increased Pax4 expression.90 Givinostat, an inhibitor of lysine deacetylase (KDAC), also showed promising effects for treating T2DM, since it inhibited IL-1β transcription in rats, thus inducing cytoprotection of β-cells.91

The data about the protection and induction of the β-cell mass by HDACi, through the inhibition of inflammatory pathways and stimulation of proliferation and differentiation genes, support the importance of experimental and clinical studies analyzing HDACi as novel potential anti-diabetic epidrugs.

HDAC activators

Sirtuins belong to class III HDACs and regulate several cellular processes, such as senescence, apoptosis, proliferation, differentiation, and inflammatory response.92,93 Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1), by deacetylating histone and non-histone proteins, exerts a protective effect against chronic degenerative diseases, such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease.93 Some reports suggested that SIRT1 mediates the effects of metformin, a drug that corrects hyperglycemia, through inhibition of gluconeogenesis. In particular, metformin upregulates SIRT1, which, in turn, reduces TORC2 and PGC1-α activity and the plasma levels of glucose and insulin.94 A 16-week double-blind, placebo-controlled, completed, and published study (NCT00570739) demonstrated that the combination therapy with metformin plus colesevelam (a bile acid sequestrant) was able to significantly reduce the concentration of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) particles and improved the atherogenic plasma lipoprotein profile of patients with early T2DM (Table 2).95

The dietary polyphenol resveratrol (one of the first activators of SIRT1 to be identified) exerts an anti-diabetic activity by regulating the activity of AMPK and PGC-1α.96,97 Due to the scientific evidence about the biologic activities of resveratrol, its efficacy for the treatment of several aging-related pathologies including T2DM has been clinically evaluated.98 Moreover, synthetic SIRT1 activators, such as SRT1720, have been developed to improve glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity in animal models of T2DM.93,99 A number of clinical trials have investigated the effect of resveratrol on T2DM, gestational diabetes, obesity, insulin resistance, inflammation, and metabolic syndrome (Table 2). The completed trial NCT01677611 is the first human study that examined the effect of oral resveratrol administration on the expression of skeletal muscle SIRT1, which regulates energy expenditure through increased skeletal muscle SIRT1 and AMPK expression. This study has been conducted in 10 T2DM patients in a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind fashion. Moreover, one completed clinical trial (NCT01038089) tested the hypothesis that resveratrol had favorable effects on endothelial function in patients with T2DM (Table 2). A randomized, double-blind, completed, and published, crossover trial (NCT01302639) implied that long-term supplementation of epigallocatechin-gallate combined with resveratrol might favor metabolic health and reduce body weight.100 Recently, improved glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity in T2DM patients treated with resveratrol were confirmed in a meta-analysis of 11 clinical trials.101

miRNA inhibitors

miRNAs are considered potential pharmacological agents for the treatment of diabetes.102,103 Two main miRNA-based therapeutic approaches have been developed for diabetes: overexpression of miRNAs using chemically synthesized miRNA mimics and inhibition of miRNAs by specific inhibitors.103 The antisense oligonucleotide 2′-O-methyl-miR-375 increases the expression of its target gene 3′-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1 (PDK-1) and reverts insulin release back to normality in vitro.104 Inhibition of miR-103 and miR-107 by 2′-O-methyl-miR-103 and −107 antisense oligonucleotides improves glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity in mice (Fig. 1).105 The inhibition of miR-21, miR-34a, or miR-146a with antisense molecules in β-cells treated with IL-1β improves glucose-induced insulin secretion (Fig. 1).50 On the other hand, the inhibition of miR-34a or miR-146 by oligonucleotides, partially protects palmitate-treated β-cells from apoptosis, but cannot restore normal insulin secretion.106

Other potential epidrugs

Statins are potent inhibitors of cholesterol biosynthesis. They represent the gold standard therapy for hypercholesterolemia and the most powerful strategy for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease.107,108 Diabetes is a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease and increased, small, dense LDL characterize diabetic dyslipidemia. Therefore, statin therapy is being tested in many clinical trials on diabetic patients to reduce the cardiovascular risk. Moreover, a novel mechanism, to explain the multiple effects of statins, relates to their potential epigenetic effects. Indeed, it has been demonstrated that pretreatment of oxidized LDL-exposed cells with statins reduces histone modifications and recruitment of CREB-binding protein 300, NF-kB, and RNA polymerase II, but prevents loss of binding of HDAC1 and 2 to the IL-8 and MCP-1 gene promoters.109,110 Getting back to the cardiovascular protective effect of statins, a controversy exists due to the observations that statin therapy has been associated with a 10–12% increased risk of developing diabetes.111 A meta-analysis showed that statin therapy is associated with a 9% increase risk for diabetes; however, authors conclude that the benefits of statin therapy outweighed the risks.112 Indeed, hyperglycemia produces endothelial dysfunction, a key determinant of diabetic micro- and macro-angiopathy, and statins could be beneficial in both conditions due to pleiotropic effects of this particular class of drugs.113

Exendin-4 is a natural occurring agonist of the glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor (GLP-1R) with 54% protein sequence homology with GLP-1. This peptide, together with the gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP), is an intestinal hormone with incretin effect. Synthetic analogs of exendin-4 have been approved for diabetes therapy, and their efficacy is mostly linked to their resistance to degradation by DPP-4, the enzyme that quickly degrades endogenous GLP-1.114 Later studies suggested that epigenetic effects, such as DNA methylation and/or histone modifications, could mediate the effects of exendin-4 and its synthetic analogs.115 However, it is not known whether these peptides exert the anti-diabetic effect by inducing epigenetic changes, and their classification as epidrug remains hypothetical.

Conclusions and perspectives

On the basis of the accumulating evidence, it is conceivable that epigenetic mechanisms could provide a significant contribution to fight the diabetes epidemics. The role of epigenetics in T2DM is being progressively revealed. It is also being appreciated that epigenetics is involved in the inflammatory components of T2DM, and inflammation plays an important role in all aspects of the disease. Therefore, the possibility to modulate the epigenetic machinery adds novel possibilities for curing and preventing diabetes.

With this vision, we have summarized current data on the involvement of epigenetic changes in the pathogenesis of diabetes and highlighted the contribution of the epigenetic machinery to the immuno-inflammatory pathways in the context of T2DM. Finally, we reported potential epigenetic strategies for treatment and prevention of diabetes.

Pancreatic cells are crucial to glucose homeostasis and epigenetic modifications interfere with their differentiation and normal function. Hence, we highlighted several molecular and epigenetic mechanisms that hinder the transcriptional process and regular replication of pancreatic β-cells. Epigenetic mechanisms profoundly affect insulin resistance in the most relevant metabolic tissues, such as liver, muscle, and adipose tissue. Innate immunity and inflammation, the processes underlying the pathogenesis of T2DM and its complications, are strongly related to the activation of the NF-kB and IRF pathways, which are regulated by the epigenetic machinery. Interestingly, miRNAs and other epigenetic mediators are emerging as relevant control factors in these conditions. Based on the reported evidence, there is a vigorous thrust in looking for novel epigenetic-based therapies for curing diabetes, the concomitant inflammatory state, and the associated complications. Several clinical trials are ongoing and their results are longed for.

In perspective, studying the involvement of epigenetics in the onset and progression of T2DM and its associated complications is a mandatory task for biomedical science. β-cell function, inflammation, aging-related processes are all involved in T2DM and influenced by epigenetic mechanisms. Novel therapies based on epigenetic modulators and emerging from innovative technologies might help reduce the global burden of T2DM; the road ahead, to translate the results from experimental and human studies into the clinics, is still a long one.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.American Diabetes Association Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care 2008; 31:S55-60; PMID:18165338; https://doi.org/26616880 10.2337/dc08-S055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gray SP, Jandeleit-Dahm K. The pathobiology of diabetic vascular complications cardiovascular and kidney disease. J Mol Med (Berl) 2014; 92:441-52; PMID:24687627; https://doi.org/26616880 10.1007/s00109-014-1146-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Picascia A, Grimaldi V, Iannone C, Soricelli A, Napoli C. Innate and adaptive immune response in stroke: Focus on epigenetic regulation. J Neuroimmunol 2015; 289:111-20; PMID:26616880; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2015.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prentki M, Nolan CJ. Islet beta cell failure in type 2 diabetes. J Clin Invest 2006; 116:1802-12; PMID:16823478; https://doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI29103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donath MY, Shoelson SE. Type 2 diabetes as an inflammatory disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2011; 11:98-107; PMID:21233852; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nri2925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guariguata L, Whiting DR, Hambleton I, Beagley J, Linnenkamp U, Shaw JE. Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2013 and projections for 2035. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2014; 103:137-49; PMID:24630390; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.diabres.2013.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keating S, El-Osta A. Epigenetic changes in diabetes. Clin Genet 2013; 84:1-10; PMID:23398084; https://doi.org/ 10.1111/cge.12121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zoghbi HY, Beaudet AL. Epigenetics and Human Disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2016. February 1; 8(2):a019497; PMID:26834142; https://doi.org/ 10.1101/cshperspect.a019497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grimaldi V, De Pascale MR, Zullo A, Soricelli A, Infante T, Mancini FP, Napoli C. Evidence of epigenetic tags in cardiac fibrosis. J Cardiol 2017. Feb; 69(2):401-08; PMID:27863907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ito S, Kuraoka I. Epigenetic modifications in DNA could mimic oxidative DNA damage: A double-edged sword. DNA Repair (Amst) 2015; 32:52-7; PMID:25956859; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.dnarep.2015.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alamdari N, Aversa Z, Castillero E, Hasselgren PO. Acetylation and deacetylation-novel factors in muscle wasting. Metabolism 2013; 62:1-11; PMID:22626763; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.metabol.2012.03.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arnes L, Sussel L. Epigenetic modifications and long noncoding RNAs influence pancreas development and function. Trends Genet 2015; 31:290-9; PMID:25812926; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.tig.2015.02.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raghuraman S, Donkin I, Versteyhe S, Barrès R, Simar D. The emerging role of epigenetics in inflammation and immunometabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2016; 27(11):782-795; PMID:27444065; https://doi.org/15561921 10.1016/j.tem.2016.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henquin JC. Pathways in beta-cell stimulus-secretion coupling as targets for therapeutic insulin secretagogues. Diabetes 2004; 53:S48-58; PMID:15561921; https://doi.org/ 10.2337/diabetes.53.suppl_3.S48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yagihashi S, Inaba W, Mizukami H. Dynamic pathology of islet endocrine cells in type 2 diabetes: β-Cell growth, death, regeneration and their clinical implications. J Diabetes Investig 2016; 7:155-65; PMID:27042265; https://doi.org/ 10.1111/jdi.12424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leibowitz G, Kaiser N, Cerasi E. β -Cell failure in type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Investig 2011; 2:82-91; PMID:24843466; https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.2040-1124.2010.00094.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson JS, Evans-Molina C. Translational implications of the β-cell epigenome in diabetes mellitus. Transl Res 2015; 165:91-101; PMID:24686035; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.trsl.2014.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quilichini E, Haumaitre C. Implication of epigenetics in pancreas development and disease. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015; 29:883-98; PMID:26696517; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.beem.2015.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sosa-Pineda B. The gene Pax4 is an essential regulator of pancreatic beta-cell development. Mol Cells 2004; 18:289-94; PMID:15650323 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Volkmar M, Dedeurwaerder S, Cunha DA, Ndlovu MN, Defrance M, Deplus R, Calonne E, Volkmar U, Igoillo-Esteve M, Naamane N, et al.. DNA methylation profiling identifies epigenetic dysregulation in pancreatic islets from type 2 diabetic patients. EMBO J 2012; 31:1405-26; PMID:22293752; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/emboj.2011.503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dhawan S, Georgia S, Tschen SI, Fan G, Bhushan A. Pancreatic beta cell identity is maintained by DNA methylation-mediated repression of Arx. Dev Cell 2011; 20:419-29; PMID:21497756; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.03.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fu X, Jin L, Wang X, Luo A, Hu J, Zheng X, Tsark WM, Riggs AD, Ku HT, Huang W. MicroRNA-26a targets ten eleven translocation enzymes and is regulated during pancreatic cell differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013; 110:17892-7; PMID:24114270; https://doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1317397110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lenoir O, Flosseau K, Ma FX, Blondeau B, Mai A, Bassel-Duby R, Ravassard P, Olson EN, Haumaitre C, Scharfmann R. Specific control of pancreatic endocrine β- and δ-cell mass by class IIa histone deacetylases HDAC4, HDAC5, and HDAC9. Diabetes 2011; 60:2861-71; PMID:21953612; https://doi.org/ 10.2337/db11-0440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scott RA, Lagou V, Welch RP, Wheeler E, Montasser ME, Luan J, Mägi R, Strawbridge RJ, Rehnberg E, Gustafsson S, et al.. Large-scale association analyses identify new loci influencing glycemic traits and provide insight into the underlying biological pathways. Nat Genet 2012; 44:991-1005; PMID:22885924; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/ng.2385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morris AP, Voight BF, Teslovich TM, Ferreira T, Segrè AV, Steinthorsdottir V, Strawbridge RJ, Khan H, Grallert H, Mahajan A, et al.. Large-scale association analysis provides insights into the genetic architecture and pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet 2012; 44:981-90; PMID:22885922; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/ng.2383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dechamethakun S, Muramatsu M. Long noncoding RNA variations in cardiometabolic diseases. J Hum Genet 2017. Jan; 62(1):97-104; PMID:27305986; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/jhg.2016.70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Francis J, Babu DA, Deering TG, Chakrabarti SK, Garmey JC, Evans-Molina C, Taylor DG, Mirmira RG. Role of chromatin accessibility in the occupancy and transcription of the insulin gene by the pancreatic and duodenal homeobox factor 1. Mol Endocrinol 2006; 20:3133-45; PMID:16901969; https://doi.org/ 10.1210/me.2006-0126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mosley AL, Corbett JA, Ozcan S. Glucose regulation of insulin gene expression requires the recruitment of p300 by the beta-cell-specific transcription factor Pdx-1. Mol Endocrinol 2004; 18:2279-90; PMID:15166251; https://doi.org/ 10.1210/me.2003-0463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hall E, Dayeh T, Kirkpatrick CL, Wollheim CB, Dekker Nitert M, Ling C. DNA methylation of the glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor (GLP1R) in human pancreatic islets. BMC Med Genet 2013; 14:76; PMID:23879380; https://doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2350-14-76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.FDA http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm513602.htm/; 2016. [accessed 05.September.16]

- 31.Ling C, Del Guerra S, Lupi R, Rönn T, Granhall C, Luthman H, Masiello P, Marchetti P, Groop L, Del Prato S. Epigenetic regulation of PPARGC1A in human type 2 diabetic islets and effect on insulin secretion. Diabetologia 2008; 51:615-22; PMID:18270681; https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s00125-007-0916-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lysy PA, Corritore E, Sokal EM. New insights into diabetes cell therapy. Curr Diab Rep 2016. May; 16(5):38; PMID:26983626; https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s11892-016-0729-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grimaldi V, Schiano C, Casamassimi A, Zullo A, Soricelli A, Mancini FP, Napoli C. Imaging techniques to evaluate cell therapy in peripheral artery disease: state of the art and clinical trials. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging 2016. May; 36(3):165-78; PMID:25385089; https://doi.org/ 10.1111/cpf.12210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heng BC, Heinimann K, Miny P, Iezzi G, Glatz K, Scherberich A, Zulewski H, Fussenegger M. mRNA transfection-based, feeder-free, induced pluripotent stem cells derived from adipose tissue of a 50-year-old patient. Metab Eng 2013; 18:9-24; PMID:23542141; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ymben.2013.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saxena P, Heng BC, Bai P, Folcher M, Zulewski H, Fussenegger M. A programmable synthetic lineage-control network that differentiates human IPSCs into glucose-sensitive insulin-secreting beta-like cells. Nat Commun 2016; 7:11247; PMID:27063289; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/ncomms11247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhu S, Russ HA, Wang X, Zhang M, Ma T, Xu T, Tang S, Hebrok M, Ding S. Human pancreatic beta-like cells converted from fibroblasts. Nat Commun 2016; 7:10080; PMID:26733021; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/ncomms10080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ludwig B, Reichel A, Steffen A, Zimerman B, Schally AV, Block NL, Colton CK, Ludwig S, Kersting S, Bonifacio E, et al.. Transplantation of human islets without immunosuppression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013; 110:19054-58; PMID:24167261; https://doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1317561110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scharp DW, Marchetti P. Encapsulated islets for diabetes therapy: history, current progress, and critical issues requiring solution. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2014; 67-68:35-73; PMID:23916992; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.addr.2013.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Quiskamp N, Bruin JE, Kieffer TJ. Differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells into β-cells: Potential and challenges. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015; 29:833-847; PMID:26696513; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.beem.2015.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khodabandehloo H, Gorgani-Firuzjaee S, Panahi S, Meshkani R. Molecular and cellular mechanisms linking inflammation to insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction. Transl Res 2015 pii:S1931-5244(15)00297-2 2016; 167:228-56; PMID:26408801; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.trsl.2015.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prattichizzo F, Giuliani A, Ceka A, Rippo MR, Bonfigli AR, Testa R, Procopio AD, Olivieri F. Epigenetic mechanisms of endothelial dysfunction in type 2 diabetes. Clin Epigenetics 2015; 7:56; PMID:26015812; https://doi.org/ 10.1186/s13148-015-0090-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brasacchio D, Okabe J, Tikellis C, Balcerczyk A, George P, Baker EK, Calkin AC, Brownlee M, Cooper ME, El-Osta A. Hyperglycemia induces a dynamic cooperativity of histone methylase and demethylase enzymes associated with gene-activating epigenetic marks that coexist on the lysine tail. Diabetes 2009; 58:1229-36; PMID:19208907; https://doi.org/ 10.2337/db08-1666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nilsson E, Jansson PA, Perfilyev A, Volkov P, Pedersen M, Svensson MK, Poulsen P, Ribel-Madsen R, Pedersen NL, Almgren P, et al.. Altered DNA methylation and differential expression of genes influencing metabolism and inflammation in adipose tissue from subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 2014; 63:2962-76; PMID:24812430; https://doi.org/ 10.2337/db13-1459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Remely M, Aumueller E, Jahn D, Hippe B, Brath H, Haslberger AG. Microbiota and epigenetic regulation of inflammatory mediators in type 2 diabetes and obesity. Benef Microbes 2014; 5:33-43; PMID:24533976; https://doi.org/ 10.3920/BM2013.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stefan N, Häring HU, Hu FB, Schulze MB. Metabolically healthy obesity: epidemiology, mechanisms, and clinical implications. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2013; 1:152-62; PMID:24622321; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70062-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guénard F, Tchernof A, Deshaies Y, Pérusse L, Biron S, Lescelleur O, Biertho L, Marceau S, Vohl MC. Differential methylation in visceral adipose tissue of obese men discordant for metabolic disturbances. Physiol Genomics 2014; 46:216-22; PMID:24495915; https://doi.org/ 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00160.2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ortega FJ, Moreno M, Mercader JM, Moreno-Navarrete JM, Fuentes-Batllevell N, Sabater M, Ricart W, Fernández-Real JM. Inflammation triggers specific microRNA profiles in human adipocytes and macrophages and in their supernatants. Clin Epigenetics 2015; 7:49; PMID:25926893; https://doi.org/ 10.1186/s13148-015-0083-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nesca V, Guay C, Jacovetti C, Menoud V, Peyot ML, Laybutt DR, Prentki M, Regazzi R. Identification of particular groups of microRNAs that positively or negatively impact on beta cell function in obese models of type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 2013; 56:2203-12; PMID:23842730; https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s00125-013-2993-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Roggli E, Britan A, Gattesco S, Lin-Marq N, Abderrahmani A, Meda P, Regazzi R. Involvement of microRNAs in the cytotoxic effects exerted by proinflammatory cytokines on pancreatic β-cells. Diabetes 2010; 59:978-86; PMID:20086228; https://doi.org/ 10.2337/db09-0881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Heneghan HM, Miller N, McAnena OJ, O'Brien T, Kerin MJ. Differential miRNA expression in omental adipose tissue and in the circulation of obese patients identifies novel metabolic biomarkers. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011; 96:E846-E850; PMID:21367929; https://doi.org/ 10.1210/jc.2010-2701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhao X, Mohan R, Özcan S, Tang X. MicroRNA-30d induces insulin transcription factor MafA and insulin production by targeting mitogen-activated protein 4 kinase 4 (MAP4K4) in pancreatic β-cells. J Biol Chem 2012; 287:31155-64; PMID:22733810; https://doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M112.362632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hotamisligil GS, Shargill NS, Spiegelman BM. Adipose expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha: direct role in obesity-linked insulin resistance. Science 1993; 259:87-91; PMID:7678183; https://doi.org/ 10.1126/science.7678183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature 2006; 444:860-7; PMID:17167474; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nature05485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xu H, Barnes GT, Yang Q, Tan G, Yang D, Chou CJ, Sole J, Nichols A, Ross JS, Tartaglia LA, et al.. Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance. J Clin Invest 2003; 112:1821-30; PMID:14679177; https://doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI200319451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Arner E, Mejhert N, Kulyté A, Balwierz PJ, Pachkov M, Cormont M, Lorente-Cebrián S, Ehrlund A, Laurencikiene J, Hedén P, et al.. Adipose tissue microRNAs as regulators of CCL2 production in human obesity. Diabetes 2012; 61:1986-93; PMID:22688341; https://doi.org/ 10.2337/db11-1508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang D, Garcia-Bassets I, Benner C, Li W, Su X, Zhou Y, Qiu J, Liu W, Kaikkonen MU, Ohgi KA, et al.. Reprogramming transcription by distinct classes of enhancers functionally defined by eRNA. Nature 2011; 474:390-4; PMID:21572438; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nature10006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhu X, Wu YB, Zhou J, Kang DM. Upregulation of lncRNA MEG3 promotes hepatic insulin resistance via increasing FoxO1 expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2016; 469:319-25; PMID:26603935; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.11.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dhliwayo N, Jr Sarras MP, Luczkowski E, Mason SM, Intine RV. Parp inhibition prevents ten-eleven translocase enzyme activation and hyperglycemia-induced DNA demethylation. Diabetes 2014. September; 63(9):3069-76; PMID:24722243; https://doi.org/ 10.2337/db13-1916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Napoli C, Crudele V, Soricelli A, Al-Omran M, Vitale N, Infante T, Mancini FP. Primary prevention of atherosclerosis: a clinical challenge for the reversal of epigenetic mechanisms? Circulation 2012; 125:2363-73; PMID:22586291; https://doi.org/ 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.085787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Heard E, Martienssen RA. Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance: myths and mechanisms. Cell 2014; 157:95-109; PMID:24679529; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stegemann R, Buchner DA. Transgenerational inheritance of metabolic disease. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2015; 43:131-40; PMID:25937492; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.semcdb.2015.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Torrens C, Poston L, Hanson MA. Transmission of raised blood pressure and endothelial dysfunction to the F2 generation induced by maternal protein restriction in the F0, in the absence of dietary challenge in the F1 generation. Br J Nutr 2008; 100:760-6; PMID:18304387; https://doi.org/ 10.1017/S0007114508921747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zullo A, Casamassimi A, Mancini FP, Napoli C. Cardiovascular disease and transgenerational epigenetic effects : Tollefsbol T, editor Transgenerational Epigenetics. Evidence and Debate, San Diego: Academic Press; 2014, p. 321-341; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/B978-0-12-405944-3.01001-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Barker DJ, Hales CN, Fall CH, Osmond C, Phipps K, Clark PM. Type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus, hypertension and hyperlipidaemia (syndrome X): relation to reduced fetal growth. Diabetologia 1993; 36:62-7; PMID:8436255; https://doi.org/ 10.1007/BF00399095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]