Abstract

Background

Injury to the ipsilateral graft used for reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) or a new injury to the contralateral ACL are disastrous outcomes after successful ACL reconstruction (ACLR), rehabilitation, and return to activity. Studies reporting ACL reinjury rates in younger active populations are emerging in the literature, but these data have not yet been comprehensively synthesized.

Purpose

To provide a current review of the literature to evaluate age and activity level as the primary risk factors in reinjury after ACLR.

Study Design

Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Methods

A systematic review of the literature was conducted via searches in PubMed (1966 to July 2015) and EBSCO host (CINAHL, Medline, SPORTDiscus [1987 to July 2015]). After the search and consultation with experts and rating of study quality, 19 articles met inclusion for review and aggregation. Population demographic data and total reinjury (ipsilateral and contralateral) rate data were recorded from each individual study and combined using random-effects meta-analyses. Separate meta-analyses were conducted for the total population data as well as the following subsets: young age, return to sport, and young age + return to sport.

Results

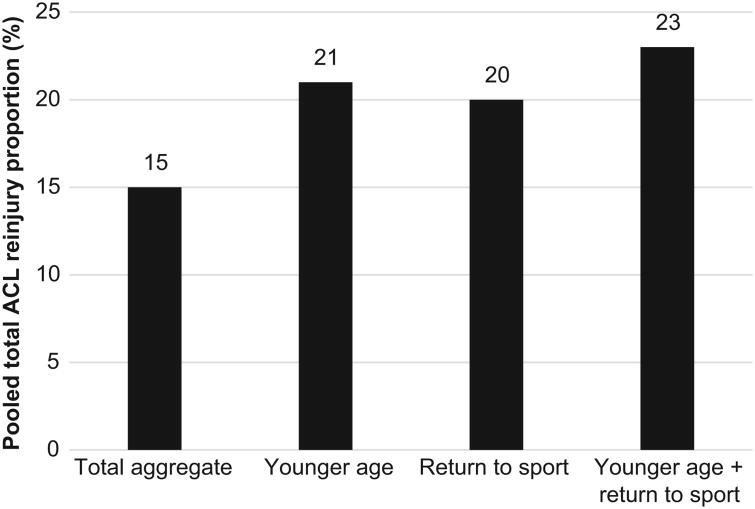

Overall, the total second ACL reinjury rate was 15%, with an ipsilateral reinjury rate of 7% and contralateral injury rate of 8%. The secondary ACL injury rate (ipsilateral + contralateral) for patients younger than 25 years was 21%. The secondary ACL injury rate for athletes who return to a sport was also 20%. Combining these risk factors, athletes younger than 25 years who return to sport have a secondary ACL injury rate of 23%.

Conclusion

This systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrates that younger age and a return to high level of activity are salient factors associated with secondary ACL injury. These combined data indicate that nearly 1 in 4 young athletic patients who sustain an ACL injury and return to high-risk sport will go on to sustain another ACL injury at some point in their career, and they will likely sustain it early in the return-to-play period. The high rate of secondary injury in young athletes who return to sport after ACLR equates to a 30 to 40 times greater risk of an ACL injury compared with uninjured adolescents. These data indicate that activity modification, improved rehabilitation and return-to-play guidelines, and the use of integrative neuromuscular training may help athletes more safely reintegrate into sport and reduce second injury in this at-risk population.

Keywords: ACL injury, ACL revision, knee injury, knee injury prevention

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is one of the most commonly injured ligaments of the knee.59 The incidence of ACL injuries in the United States is currently estimated to be between 100,000 and 200,000 annually.2 Athletes who injure their ACL often miss extended periods of participation in sport, with potential consequences including lost scholarship earnings and long-term disability, especially in the form of osteoarthritis.8 ACL injuries are also a burden on the health care system, with annual costs exceeding US$625 million.15,16,20

The ACL injury rate is highest in younger athletes who participate in high-risk sports that involve cutting and pivoting, such as basketball, football, skiing, and soccer.3,7 Common risk factors for ACL injuries include female sex and young age (especially in adolescents).4 Complete ACL ruptures are usually season-ending injuries resulting in the need for operative reconstruction. It is widely accepted that ACL reconstruction (ACLR) of the young active adult (18-35 years) should be pursued to reduce knee laxity, episodes of instability, and the incidence of subsequent injuries, including meniscal tears.59

Numerous factors affect a good outcome after ACLR such as surgical technique, graft choice, graft fixation, postoperative rehabilitation, and patient education. Unfortunately, graft failure and contralateral ACL rupture can still occur even after successful ACLR. Graft failure rates after ACLR range from 3% up to 25% in some populations.10 The causes of graft failure and contralateral ACL rupture are not clear, but research suggests that they may include a combination of genetic and environmental factors. Because these complications are less frequent compared with initial ACL rupture, current literature discussing graft failure and contralateral ACL injury after primary ACL injury is limited. As the frequency of ACL injuries and surgical interventions increases, more thorough clinical information is being deposited into databases to track these complications. These data and the studies arising from them form the basis for this systematic review, which provides an analysis of the current literature that assesses the risk factors of age and activity level after ACLR with regard to secondary ACL injury. We hypothesized that young age and return to sport would be proxies for increased second ACL injury risk. By synthesizing existing literature, this review may help to better understand outcomes after ACLR and reduce the prevalence of second ACL injuries.

Methods

The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines were followed when conducting and reporting this review and meta-analysis.

Literature Search

An independent information specialist was consulted during the design phase of the search process. The electronic search engines PubMed (1966 to July 2015) and EBSCO host (CINAHL, Medline, SPORTDiscus [1987 to July 2015]) were used to search the following keywords in both databases (acl and anterior cruciate ligament were searched for each phrase): acl reconstruction return to sport, acl reconstruction outcomes, acl risk factors, revision acl risk factors, contralateral acl risk factors, and age acl risk factors. This yielded 7098 abstracts for initial review after duplicates were removed. The full text of an article was obtained if the title or abstract discussed age and/or activity level as a risk factor for recurrent or contralateral ACL rupture. Articles that were not written in English were not considered in this review. Articles that did not specifically discuss rerupture and/or contralateral rupture rates in relation to age and/or activity level were excluded. Specifically, to be included, ACL injuries needed to be stratified into statistically comparable age groups, or the activity level/sport played at the time of reinjury needed to be reported.

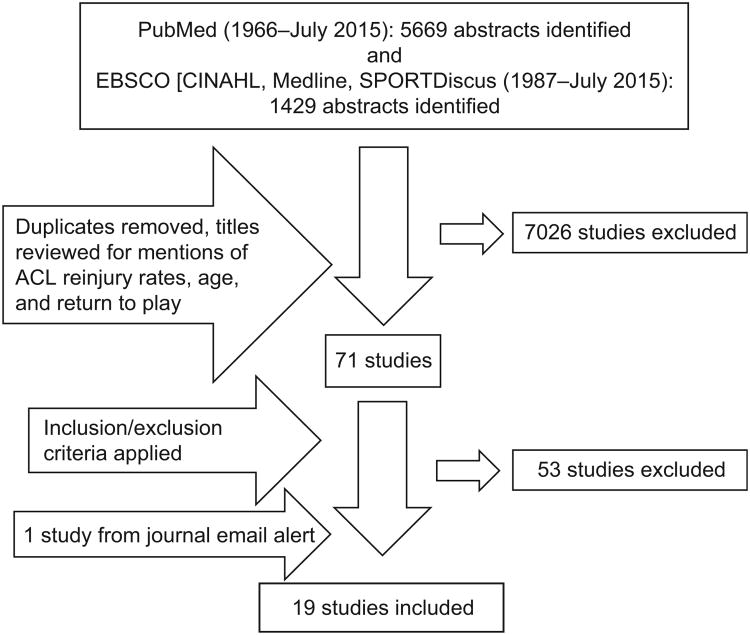

A total of 71 articles were obtained and read in their entirety, of which 53 were excluded because they did not break down reinjury risk factors into age and/or activity level categories. In addition to the electronic searches, experts in the field were contacted for further article suggestions and to attempt to identify pertinent unpublished studies. Corresponding authors of articles were contacted for additional information as needed. References from the included articles were also reviewed to ensure all articles meeting inclusion criteria were identified. Supplementary references from the American Association of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) guidelines, Management of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries, were also reviewed. At the conclusion of the search, 19 articles met the inclusion criteria (18 from the initial electronic search and 1 identified via a journal email alert after the initial search) and were included in this review of the literature. A summary of the literature search process can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of literature search and review process.

Assessment of Study Quality

The Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) scale and a modified Downs and Black11 checklist were used to measure the methodological quality of the included studies. The PEDro scale is used to rate the methodological quality of randomized control trials, while the modified Downs and Black checklist is appropriate for rating nonrandomized studies. The PEDro scale consists of 11 items, 10 of which assess the internal validity of a study and are scored by allocating a point to each criteria that is met (see Table 1 for item categories). The Downs and Black checklist was modified to include only criteria that were relevant to assessing potential sources of bias in the included studies (see Table 2). This led to a checklist of 11 items. The more items that are satisfied, the less risk of bias in the study. Each study was independently assessed by 2 authors, and any disagreements were resolved by arbitration and consensus. The results of these assessments are shown in Tables 1 and 2. The mean PEDro score was 2.8 (range, 2-4), and for the modified Downs and Black checklist, the mean number of items rated was 8.8 (range, 7-10). The scores on the PEDro scale were low relative to the maximum possible total score of 10 because of the nonrandomized nature of the included studies. From the Downs and Black checklist, studies mostly did not indicate whether the included subjects were representative of the population, and only 1 study performed a power calculation.

Table 1. Levels of Evidence and PEDro Scores for All Included Studiesa.

| PEDro Score Distributionb | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||||||

| Study | Level of Evidence | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | Total PEDro Scorec |

| Ahldén et al2 | 4 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Andernord et al3 | 2b | 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1 | — | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Borchers et al4 | 3b | 1 | — | — | 1 | — | — | — | 1 | — | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Bourke et al (2012a)6 | 4 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1 | — | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Bourke et al (2012b)5 | 4 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1 | — | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Ellis et al12 | 2b | 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1 | — | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Fältström et al14 | 3b | 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1 | — | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Kaeding et al23 | 2b | 1 | — | — | 1 | — | — | — | — | — | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Kamath et al25 | 4 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Kamien et al26 | 3b | 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1 | — | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Laboute et al28 | 2b | 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Lind et al32 | 2b | 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1 | — | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Magnussen et al34 | 2b | 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Paterno et al (2012)50 | 3b | 1 | — | — | 1 | — | — | — | 1 | — | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Paterno et al (2014)51 | 2 | 1 | — | — | 1 | — | — | — | 1 | — | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Reid et al52 | 4 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1 | — | — | 1 | 2 |

| Salmon et al53 | 4 | 1 | — | — | 1 | — | — | — | 1 | — | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Shelbourne et al56 | 2b | 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Webster et al61 | 3b | 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1 | 1 | 2 |

A “1” indicates a “yes” score, and a dash indicates a “no” score. PEDro, Physiotherapy Evidence Database.

The PEDro scale is optimal for evaluating randomized control trials; therefore, it should be interpreted with caution in the studies included here, as they are nonrandomized. 1 = eligibility criteria specified; 2 = random allocation of subjects; 3 = allocation concealed; 4 = similar groups at baseline; 5 = blinding of subjects; 6 = blinding of intervention providers; 7 = blinding of outcome assessors; 8 = outcomes obtained from 85% of subjects; 9 = use of intent-to-treat analysis if protocol violated; 10 = between-group statistical comparison; 11 = point measures and measures of variability.

Total of items 2-11.

Table 2. Modified Downs and Black11 Checklista.

| Downs and Black Checklist Items Includedb | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||||

| Study | 1 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 7 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 16 | 18 | 27 | Total |

| Ahldén et al2 | ||||||||||||

| Andernord et al3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — | 10 |

| Borchers et al4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — | 10 |

| Bourke et al (2012a)6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — | 1 | 1 | — | 9 |

| Bourke et al (2012b)5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — | 1 | 1 | — | 9 |

| Ellis et al12 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — | 10 |

| Faltstrom et al14 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| Kaeding et al23 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — | 10 |

| Kamath et al25 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — | 9 |

| Kamien et al26 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — | 1 | 1 | — | 1 | 1 | — | 8 |

| Laboute et al28 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — | 10 |

| Lind et al32 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — | 1 | — | 1 | — | 1 | 1 | — | 7 |

| Magnussen et al34 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — | 1 | 1 | — | 9 |

| Paterno et al (2012)50 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — | — | 1 | 1 | — | 8 |

| Paterno et al (2014)51 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — | — | 1 | 1 | — | 8 |

| Reid et al52 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — | 1 | — | 1 | 1 | — | 8 |

| Salmon et al53 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — | 1 | 1 | — | 9 |

| Shelbourne et al56 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — | — | 1 | 1 | — | 8 |

| Webster et al61 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — | 1 | 1 | — | 9 |

Only criteria relevant to the included studies were used here; therefore, several criteria were excluded, yielding a checklist of 11 items with a maximum total of 11. A “1” indicates a “yes” score, and a dash indicates a “no” score.

1 = clear aim; 2 = outcomes described; 3 = subjects described; 6 = main findings clearly described; 7 = estimates of random variability; 10 = probability values reported; 11 = subjects asked represent population; 12 = included subjects represent population; 16 = planned data analysis; 18 = appropriate statistics; 27 = power calculation.

Level of Evidence Method

The Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine level of evidence was used to rate each study. The level of evidence assesses research design quality. Levels of evidence for each study can be seen in Table 1.

Data Extraction

The population size and number of participants were recorded from each study. The primary variables extracted were the ipsilateral ACL reinjury rates, contralateral ACL injury rates (if reported), and total secondary ACL injury (if reported) rates. If reinjury rates were reported for a specific patient age range or patients who returned to play in sports, the rates for these subgroups were separately recorded. The specific type of sport (soccer, rugby, football, etc) and the nature of the sport (high-risk jumping/cutting vs low-risk) were also extracted. One author (A.J.W.) recorded all of the pertinent data from the included articles, and 2 other authors (D.K.S. and K.E.W.) independently reviewed these data for accuracy and completeness. When mean age data were not reported, corresponding authors were contacted via email in an attempt to collect this information; however, no additional data were gained from these efforts.

Reinjury rate data were analyzed using a random-effects proportion meta-analysis (weighted for individual study size) using StatsDirect. Reinjury proportions for individual studies and pooled estimates were summarized in forest plots for the total study population as well as the following subgroups: young age, return to sport, and young age + return to sport. Data were combined ensuring that data from the same participants were not included twice. If data were reported for the same participants in more than 1 article, data were extracted from the article with the greatest number of participants. This resulted in data being pooled from Paterno et al (2014)51 but not Paterno et al (2012),50 and Bourke et al5 and Salmon et al53 were excluded if Bourke et al6 was used. Similarly, 3 studies2,3,14 analyzed data from the Swedish National Anterior Cruciate Ligament Register. For calculations, the one study with the largest sample size of this group was used; The study by Fältström et al14 was used in calculating pooled estimates for the whole population for total reinjury, ipsilateral reinjury, and contralateral reinjury. The study by Fältström et al14 was also used to calculate pooled estimates of total reinjury and contralateral injury in the young age group, while the study by Andernord et al3 was used to calculate ipsilateral reinjury in the young age group. Only 1 study24 used data from the Multi-center Orthopaedic Outcomes Network (MOON) group database, so this study was included in all calculations for which it qualified. If a study performed survival analysis, the percentage of surviving ACLs was multiplied by the number of patients within a respective group to calculate injury incidence.

Summaries of Included Studies

Ahldén et al

Ahldén et al2 published data from the Swedish National Anterior Cruciate Ligament Register on patients (N = 16,351; average age, 25.3 years [primary ACLR], 26.2 years [revision ACLR]) 5 years after ACLR. Outcome variables for this study included both ipsilateral revision ACLR and contralateral ACLR. The overall revision/reconstruction rate calculated from patients who underwent index ACLR during 2005 only was 9.1% for all ages (contralateral ACLR, 5.0%; revision ACLR, 4.1%). The highest ACL reinjury rates were for soccer players 15 to 18 years old, for whom the overall revision/reconstruction rate was 16.7% (revision ACLR rate, 9.1%; contralateral ACLR rate, 7.6%). Female soccer players aged 15 to 18 years had an overall revision/reconstruction rate of 22.0% (revision ACLR rate, 11.8%; contralateral ACLR rate, 10.2%), whereas the rate for male soccer players of the same age was a significantly lower 9.8% (revision ACLR rate, 5.4%; contralateral ACLR, 4.4%) (P = .02). The authors did not report injury incidence data on the 15-to 18-year age group as a whole. Therefore, comparisons of reinjury rates among young patients who returned to different sports were not made.

Andernord et al

Andernord et al3 also published a prospective cohort study (N = 16,930; 9767 males, 7163 females) using data from the Swedish National Knee Ligament Register, which examined the association between common patient factors and the risk of revision ACLR over a 2-year period. Contralateral ACL ruptures were not included. The overall revision ACLR rate was reported as 1.8%. Age was a significant risk factor for revision. Adolescents (age at initial ACL injury, 13-19 years) had a 3.5% incidence of revision, with an increased relative risk of 2.67 and 2.25 for males (P < .001) and females (P < .001), respectively. Results also demonstrated that athletes who returned to soccer had an increased risk of ACL reinjury, with the relative risk for males and females being 1.58 (P < .001) and 1.43 (P < .001). The revision rates for males and females aged 13 to 19 years who played soccer were 4.3% and 4.6%. This was almost 3 times higher than the risk for ACL revision in the total study population. Combining the risk factors of age and activity level further increased the risk for ACL revision surgery within the subset of subjects aged 13 to 19 at the time of index ACLR who returned to soccer (male relative risk [RR] = 2.87, P < .001; female RR = 2.59, P < .001). As the register records only patients who undergo revision ACLR, the reported rates may be conservative as they do not consider those who may have suffered a graft rupture but choose activity modification/nonoperative management over surgical treatment.

Borchers et al

Borchers et al4 published a case-control study (N = 322; average age, 27.9 years) from single-surgeon MOON group data with 2-year follow-up. Of the 322 reconstructions, 21 patients had graft failure at the 2-year follow-up (failure rate, 6.5%). Those with a higher activity level (Marx activity score ≥13) had a 5.53 greater odds of reinjury than did those with a lower activity level at the time of graft failure (95% CI, 1.18-28.61; P = .03). Investigators also found that patients who underwent allograft ACLR had a 5.56 greater odds of graft failure than those receiving a soft tissue autograft (95% CI, 1.55-19.98; P = .009). On the basis of stratum-specific odds ratio calculations, the authors theorized that high activity levels and allograft use may have a multiplicative effect on ACL graft failure.

Bourke et al (2012a)

Bourke et al6 published a 15-year follow-up (average time after ACLR, 16.8 years) to a single-surgeon case series (N = 673; average age, 29 years). This study population included the cohorts from Bourke et al5 and Salmon et al,53 respectively. Activity levels were measured using the International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) scale.22 The combined ACL reinjury rate was reported as 23% (170/673); 75 patients (11.1%) sustained a graft rupture, and 95 patients (14.1%) sustained a contralateral ACL rupture (as this adds to 25.2%, it may be that some patients in the study sustained both graft failure and contralateral ACL rupture). The data suggested that the risk for contralateral ACL injury may peak later than graft rupture, as contralateral injuries occurred at a rate of 2.4% within 2 years after ACLR compared with a rate of 5% for ipsilateral reinjuries in the same period. Those who returned to their preinjury sport after ACLR had a secondary ACL injury rate of 26.0% (11.0% ipsilateral, 15.0% contralateral) and an increased hazard ratio (HR) for contralateral ACL injury (HR = 2.5; 95% CI, 1.4-4.4; P = .003). In addition, those who were aged <18 years at the time of primary ACLR were more likely to experience a contralateral ACL injury (HR = 2.0; 95% CI, 1.2-3.3; P = .011). Graft rupture was not found to be associated with return to preinjury sport.

Bourke et al (2012b)

Bourke et al5 reported a single-surgeon case series (N = 186; average age at primary ACLR, 25.8 years) with 15-year follow-up to examine long-term outcomes after primary hamstring ACLR for patients who had isolated ACL injuries. This population was a smaller subset of the cohort reported on in the above Bourke et al6 study. The secondary ACL injury rate for all ages was 27.4%, with ipsilateral graft failure at 17.7% (33/186; 1.1% per year) and contralateral ACL rupture at 9.7%. Patients aged ≤18 years at initial ACLR experienced ipsilateral graft failure at a rate of 34.2% (13/38) compared with patients aged >18 years at ACLR, who had a 13.5% (20/148) failure rate (HR = 3.0; 95% CI, 1.5-6.0; P = .002). According to a multivariate Cox regression analysis, patients ≤18 years at the time of surgery were more than 3 times more likely to rerupture their graft when compared with patients >18 years (P = .03). A closer look at the mechanism of reinjury revealed that 14 of the 33 patients (42.4%) with ipsilateral ACL rerupture were participating in cutting/pivoting sports at the time of reinjury.

Ellis et al

Ellis et al12 published a retrospective comparative study (N = 79) that examined the rate of revision ACLR in a patient population aged younger than 18 years. Contralateral ACL injuries after primary ACLR were not reported. The study showed an ipsilateral ACL revision rate of 11%. The most common cause of graft failure was during sporting activity 12 months or less from initial surgery (77%). “Pivoting, landing, or twisting” was the most frequent type of mechanism (44%). The level of sporting activity for all patients was not reported. Twelve percent of patients were unable to be contacted at the time of follow-up, which may underestimate the true revision rate.

Fältström et al

Fältström et al14 published data from the Swedish National Anterior Cruciate Ligament Register (N = 20,824; average age, 26.7 years) to determine predictors for additional ACLR (both graft revision and contralateral ACLR). The duration of patient follow-up ranged from 6 to 104 months. The rates of revision ACLR and contralateral ACLR for all age groups were 3.4% and 2.8%, respectively, with a secondary rate of ACL injury of 6.2%. However, a 4-fold (HR = 4.26) increase in ipsilateral revision ACLR and contralateral ACLR in patients <16 years old at the time of their index injury relative to those >35 years old was also reported. This group's rate of secondary ACL injury was 12.6%, with ipsilateral reinjury at 6.0% and contralateral ACL injury at 6.5%. Patients aged 16 to 25 years had a 3-fold increase in ACL reinjury (4.6% ipsilateral revision ACLR rate, 3.6% contralateral ACLR rate, 8.2% total). It was also noted that playing soccer at the time of initial ACL injury significantly increased the patients' risk of sustaining a further ACL injury in the future relative to other sports/causes (P = .023). The authors used revision ACLR as a primary endpoint as opposed to ACL graft failure, which may underestimate the risk of ipsilateral reinjury.

Kaeding et al

Kaeding et al23 performed a prospective cohort study using both single-surgeon data (n = 281) and consortium data (n = 691) obtained from MOON at 2-year follow-up. Revision ACLR was used as an outcome measure. Single-surgeon data were used to develop a multi-variable regression model, which was then applied to data collected from a consortium of surgeons. Combined data (average age, 26.6 years) will be reported here as it may be more generalizable and better representative of global trends in reinjury after ACLR. In total, 4.9% (45/926) of patients experienced ipsilateral graft failure after ACLR. Contralateral injury was not measured. The greatest percentage (37.5%) of these injuries occurred in patients in the 10- to 19-year age group. Patients in the 10- to 19-year age group had an 8.2% failure rate. Those in the 20-to 29-year age bracket reported a 4% failure rate, 30 to 39 years had a 1.8% rate, and 40 to 49 years had a 1.7% rate.

Kamath et al

Kamath et al25 published a case series of Division I National Collegiate Athletic Association athletes (N = 89) who underwent ACLR before matriculating to college (n = 35) and after matriculation (n = 54). All athletes returned to play (RTP), defined in the study as a “successful return to a varsity roster after ACLR.” Athletes who had reconstructive surgery before attending college had a high secondary ACL injury rate of 37.1% (13/35), with a 17.2% (6/35) ipsilateral rerupture rate and a 20% (7/35) contralateral rupture rate. Athletes who underwent ACLR during college had a 1.9% (1/54) ipsilateral reinjury rate and an 11.1% (6/54) contralateral rupture rate, for a total reinjury rate of 13.0% (7/54) in this cohort. Combining these 2 subsets, the entire cohort had a total reinjury rate of 22.5% (20/89), with a 7.9% (7/89) ipsilateral rerupture rate and a 14.6% (13/89) contralateral rupture rate. The authors concluded that high levels of ipsilateral and contralateral ACL ruptures are seen in those who return to a high level of activity, and an even higher rate is seen among younger patients who return to a high level of activity.

Kamien et al

Kamien et al26 published a cohort study (N = 98; average age, 28.0 years) in which they followed patients for 2 years after ACLR with a single surgeon. Contralateral ACL injuries were not considered. Investigators found a total population ipsilateral ACL reinjury rate of 15.3% (15/98). Patients aged <25 years failed at a significantly greater rate, 25% (12/48), compared with 6% (3/50, P = .011) in those aged .25 years.

Laboute et al

Laboute et al28 reported a case series of patients (N = 298; average age, 26.2 years) followed for 4 years after ACLR. Subjects underwent ACLR performed by 48 French surgeons using either patellar tendon or hamstring tendon autografts. Data on contralateral reinjury were not reported in this study. Using results from a questionnaire, investigators found 26 reruptures (failure rate, 8.7%). The highest rate of rerupture was found in patients returning to soccer, 20.8%, compared with rugby, 6.4% (P = .03). Sports categorized as “pivoting” accounted for 25 (96%) of the reinjuries, while “pivoting with contact” occurred in 19 (73%). A nonsignificant trend toward increased reinjury was noted with increasing competitive levels; 8.1% regional level, 10.4% national level, 12.5% international level. Interestingly, 11 patients were advised to try less risky sports (ie, “pivoting with no contact,” “weightbearing with no pivoting,” and “nonweightbearing”). None of these 11 patients sustained a reinjury. This study was limited by a poor questionnaire response rate (55.1%).

Lind et al

Lind et al32 published a cohort study (N = 12,193) using data from the Danish ACLR registry, which examined the rate of revision ACLR and its relationship with patient age. Contralateral ACL injuries were not reported. The cohort showed an overall ipsilateral reinjury rate of 4.7%. The most common cause of graft failure was “new trauma” (38%), of which “sport” was the most frequent type (83% of new trauma). Patients <20 years old had a significantly higher revision rate (8.7%) than those >20 years old (2.8%; adjusted RR, 2.58; 95% CI, 2.02-3.30). In addition, functional activity (measured by the Tegner score) was significantly lower 1 year after revision ACLR when compared with primary ACLR. Like the Swedish registry, the Norwegian registry records only revision surgery data, which may underestimate the true revision rate.

Magnussen et al

Magnussen et al34 followed a cohort of patients (N = 256; average age, 25.0 years) who underwent an ACLR with hamstring tendon autografts for an average of 14 months (range, 6-47 months) to evaluate patient age as a predictor for revision ACLR. Contralateral ACLR data were not collected. An overall ipsilateral ACL reinjury rate of 7.0% (18/256 patients) was reported, but a much higher reinjury rate was seen when only the younger patients were analyzed. Specifically, for patients <20 years old, the rate was 14.3% (17/119), compared with only 0.7% (1/158; P < .0001) in patients >20 years old. The authors noted that 11 of the 18 failures were in competitive athletes, and the remaining 7 were in recreational athletes. Unfortunately, there was no information about the sports patients returned to after surgery.

Paterno et al (2012)

Paterno et al50 published their data from a prospective case-control study (N = 102; 63 cases, 39 controls; average age of cases, 16.3 years). Subjects were followed for injury surveillance for 12 months after initial testing at the time of RTP. Athlete exposure (AE; defined as “participation in a game or practice session in a pivoting or cutting sport within their individual or team sport”) and injury data were recorded. Contact ACL injuries were excluded from the study. It should be noted that by including only athletes who returned to high-risk sports, injury rates may be elevated compared with studies that do not use this criterion. The secondary ACL injury rate within 12 months of RTP in subjects with prior ACLR was 25.4% (16/63), with 6.3% (4/63) reinjuring the ipsilateral knee and 19.0% (12/63) sustaining a contralateral ACL rupture (P = .08-.09). Compared with the control group (1/39 ACL rupture), those who sustained an initial ACL injury and underwent ACLR were 15 times more likely (RR = 15.24, P = .0002) to go on to an additional ACL injury. The authors also reported that females with prior ACLR were 16 times more likely to suffer an ACL injury relative to controls (RR = 16.02; P = .0002) and 4 times more likely than males with prior ACLR to reinjure their ACL (RR = 3.65; P = .05).

Paterno et al (2014)

Paterno et al51 conducted a cohort study in which subjects who had undergone ACLR and returned to a cutting/pivoting sport (n = 78; average age, 17.1 years) and healthy control subjects (n = 47; average age, 17.2 years) were followed for 2 years. This study included 63 patients from the 2012 study published by Paterno et al,50 meaning that an additional 15 patients were added to that cohort for this study. Exclusion/inclusion criteria were the same as the aforementioned study. Injury and AE data were recorded, and incidence rates were calculated for both ipsilateral and contralateral ACL injuries. Of the subjects with a previous ACL injury and ACLR, 29.5% (23/78) sustained a second injury, with 7 (9.0%) subjects injuring the ipsilateral graft and 16 (20.5%) subjects injuring the contralateral ACL. As 12 of 63 patients in the 2012 study reinjured their ACL, this means that an extremely high number of the new patients added to this cohort were reinjured (9/15, 60%). Overall, ACL injury was 5.71 times more likely in those previously injured than in controls (RR = 5.71, P = .0003) Also, females with prior injury and ACLR sustained new injuries at a much greater rate than female controls (RR = 4.51, P = .0003). There was no such relationship found in the male subjects studied. Females were found to have a greater number of contralateral ACL injuries (n = 14) than their male counterparts (n = 2). Investigators also found that 30.4% of second injuries occurred at <20 AEs and 52.2% at <72 AEs, showing a trend toward reinjury early in the RTP period. Once again, it should be noted that the study included only those who returned to activity in high-risk cutting/pivoting sports, which may explain that relatively high rates of graft failure and contralateral injury.

Reid et al

Reid et al52 published a single-center retrospective case series (N = 100) of adolescents younger than 16 years who underwent ACLR. They examined the rate of ipsilateral graft failure after ACLR, contralateral ACL rupture, and functional outcomes 4 years after ACLR (1-9 years). The study showed a secondary ACL injury rate of 11%. Nine percent sustained an ipsilateral ACL reinjury, while 2% sustained a contralateral ACL injury. The most common cause of graft failure or mechanism for new contralateral injury was not mentioned. The Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcomes Score (KOOS) questionnaire was used to assess the patient's functional outcome after surgery. Eighty of the 100 patients completed the KOOS, and results demonstrated restriction in sports and recreation with a mean ± SD score of 54 ± 17.6 (100 = no problem, 0 = extreme problem). The other 4 key KOOS domains were 60 ± 13 for symptoms, 65 ± 10 for pain, 70 ± 6.4 for activities of daily living, and 47.2 ± 20.1 for quality of life. These data indicate that 4 years after ACL reconstruction, many of the patients had not yet returned to a fully functional state. Therefore, their reinjury rates cannot be extrapolated to the younger athletic population that does return to high levels of activity.

Salmon et al

Salmon et al53 reported a single-surgeon case series (N = 612; average age, 28.0 years) that assessed patients who had undergone primary ACLR at 5 years after operation via telephone interview. This population was a smaller subset of the cohort reported in the above Bourke et al6 study. Both contact and noncontact injuries were included in the series. Activity levels to which patients returned were measured via IKDC scores. Secondary ACL injury occurred in 71 patients in the population (12.1%), with 39 patients (6.4%) suffering an ipsilateral ACL graft failure and 35 patients (5.7%) suffering a contralateral ACL rupture. In the subset of patients who experienced ipsilateral ACL failure, 41.0% (16/39) occurred within the first 12 months after ACLR, while contralateral ACL ruptures occurred later (P = .001). Those subjects who returned to an IKDC activity level 1 or 2 had a secondary ACL injury rate of 18.5%, with ipsilateral reinjury and contralateral injury rates of 8.0% and 10.5%, respectively. Returning to these higher levels of activity significantly increased the odds for contralateral injury by 10-fold compared with those classified IKDC level 3 or 4 (1% incidence of contralateral injury). There was also a trend toward increased risk of ipsilateral ACL failure (odds ratio [OR], 2.1; 95% CI, 1.0-4.6) with high activity level.

Shelbourne et al

Shelbourne et al56 published a cohort study (N = 1415; average age, 21.6 years) in which patients were followed for 5 years after ACLR. Investigators collected data on the incidence of both ipsilateral and contralateral ACL injury, as well as patient age and activity levels. Activity level data were recorded at the time of RTP and included the specific sports to which patients returned. The overall secondary ACL injury rate was 9.6% (136/1415), with 4.3% (61/1415) ipsilateral reinjury rate and 5.3% (75/1415) contralateral injury rate. Women were found to sustain a second ACL injury at a higher rate (12.5%, 69/552) than men (7.8%, 67/863; P = .004). Patients <18 years old also had a greater secondary ACL injury rate (17.4%) than patients 18 to 25 years old (6.7%) and >25 years old (3.9%; P < .0001). In the subset of patients <18 years old, 8.7% had reinjuries to the ipsilateral knee and 8.7% had contralateral injuries. It should be noted that a small number (n = 2) of nonathletes were included in the sample.55 Of the second injuries sustained by patients <18 years old, 98% occurred during high school– or collegiate-level sports competition. Younger athletes also returned to sport participation earlier than patients aged 18 to 25 years and >25 years (P < .0001), but an early RTP (<6 months) did not result in greater rates of either ipsilateral (P = .60) or contralateral ACL injury (P = .91). While the mechanism of reinjury was not broken down by age group, more than 80% of all ACL reinjuries were sustained while participating in high-risk sports, with 52% occurring while playing basketball and 15% during soccer.

Webster et al

Webster et al61 published a single-surgeon case-control study (N = 561, average age, 28 years) with an average 5-year follow-up. The main outcome variables studied were both ACL graft rupture and contralateral ACL injury. The secondary ACL injury rate for ipsilateral graft rupture and contralateral injury was 12%, with 4.5% for ipsilateral ACL reinjury and 7.5% contralateral ACL injury. Patients <20 years old at index surgery had the highest rate of secondary ACL injury at 29.1% (13.6% ipsilateral, 15.5% contralateral). Those <20 years old at surgery were 6 times more likely to sustain an ipsilateral ACL injury and 3 times more likely to sustain a contralateral ACL injury compared with patients older than 20 years. Activity level was also a significant risk factor for reinjury. Athletes who participated in cutting or pivoting sports had a 4-fold increase in ipsilateral ACL injury and a 5-fold increase in contralateral ACL rupture. The authors concluded that age itself may be a risk factor, or age may be a proxy for other risk factors, because of the high rate of return to high-risk sports by younger patients.

Results

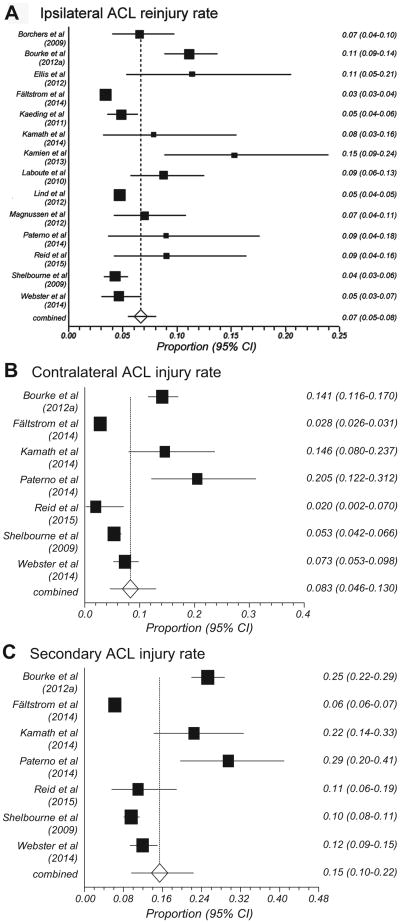

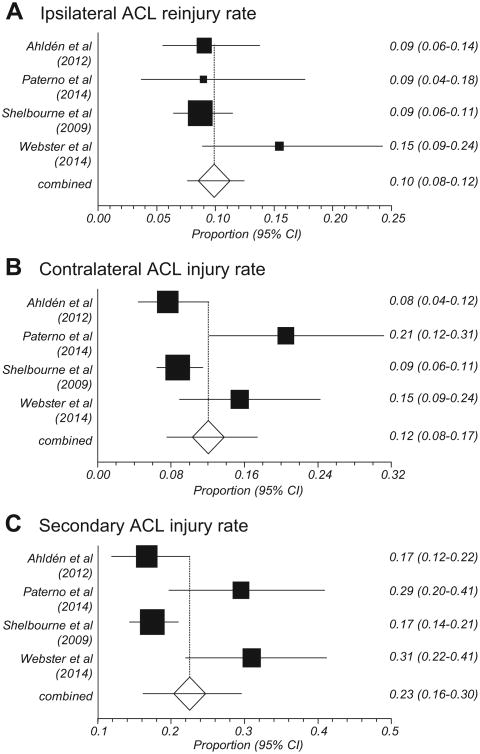

The pooled ipsilateral ACL reinjury rate (14 studies) was 7% (95% CI, 5%-8%; I2 = 91%), and the pooled contralateral ACL injury rate (7 studies) was 8% (95% CI, 5%-13%; I2 = 97%) (Figure 2). Taking the 7 studies that report both ipsilateral and contralateral data, the pooled secondary ACL injury rate was 15% (95% CI, 10%-22%; I2 = 98%) (Figure 2). As can been seen from Table 3, there were large differences in the number of participants included between the individual studies. Data from 4 studies were derived from ACL registries,2,3,14,32 and in each of these, the end point for failure was revision surgery or contralateral ACLR. This was also the case for a further 5 studies,4,12,23,34,52 whereas injury data were used to classify graft rupture and contralateral ACL injury in all the other included studies. Five studies also included only younger patients.12,25,50-52

Figure 2.

Pooled (A) ipsilateral anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reinjury rate from 14 studies, (B) contralateral ACL injury rate and (C) secondary ACL injury rate from 7 studies. Five studies2,3,5,50,53 were excluded from these calculations, as their populations were included in other studies.

Table 3. Aggregated Data From All Reviewed Studiesa.

| Study | Outcome Measure | n (Male: Female) | Follow-up, mo | Population Average Age (Range), yb | Reinjury Rate, % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Total | Ipsilateral | Contralateral | |||||

| Ahldén et al2 | Surgery | 16,351c (9402:6949) | 60 | 25.3 (N/A) | 9.1 | 4.1 | 5.0 |

| Andernord et al3 | Surgery | 16,930 (9767:7163) | 24 | 27.4 (13-59) | NR | 1.8 | NR |

| Borchers et al4 | Surgery | 322 (181:141) | 24 | 27.9 (11.6-62.3) | NR | 6.5 | NR |

| Bourke et al (2012a)6 | Injury | 673 (432:241) | 180 | 29.0 (13-62) | 25.3d | 11.1 | 14.1 |

| Bourke et al (2012b)5 | Injury | 186 (N/A) | 180 | 25.8 (14-62) | 27.4 | 17.7 | 9.7 |

| Ellis et al12 | Surgery | 79 (34:56) | 50.4 | 16 (14-18) | NR | 11.4 | NR |

| Fältström et al14 | Surgery | 20,824 (11,159:9665) | 60 | 26.7 (10-64) | 6.2 | 3.4 | 2.8 |

| Kaeding et al23 | Surgery | 926 (515:411) | 24 | 26.6 (N/A) | NR | 4.9 | NR |

| Kamath et al25 | Injury | 89 (42:37) | 37 | NR | 22.5 | 7.9 | 14.6 |

| Kamien et al26 | Injury | 98 (N/A) | 24 | 28.0 (12-52) | NR | 15.3 | NR |

| Laboute et al28 | Injury | 298 (213:59) | 48 | 26.2 (16-53) | NR | 8.7 | NR |

| Lind et al32 | Surgery | 12,193 (N/A) | 60 | NR | NR | 4.7 | NR |

| Magnussen et al34 | Surgery | 256 (136:120) | 14 | 25.0 (11-52) | NR | 7.0 | NR |

| Paterno et al (2012)50 | Injury | 63 (21:42) | 12 | 16.3 (10-25) | 25.4 | 6.3 | 19.0 |

| Paterno et al (2014)51 | Injury | 78 (19:59) | 24 | 17.1 (10-25) | 29.5 | 9.0 | 20.5 |

| Reid et al52 | Surgery | 100 (51:49) | 48 | 20.5 (13-24)e | 11 | 9 | 2 |

| Salmon et al53 | Injury | 612 (383:229) | 60 | 28.0 (14-62) | 12.1 | 6.4 | 5.7 |

| Shelbourne et al56 | Injury | 1415 (863:552) | 60 | 21.6 (14-58) | 9.6 | 4.3 | 5.3 |

| Webster et al61 | Injury | 561 (370:191) | 60 | 28.0 (N/A) | 12.0 | 4.5 | 7.5 |

| Meanf | 51.0 | 24.4 | |||||

| Participants used in meta-analysis, ng | 23,740 | 37,912 | 23,740 | ||||

Population means for follow-up time and age and the number of participants used in meta-analyses are presented here. Age at primary anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR) was used when specified. Outcome variables differed across studies, and those that measured surgical outcomes may have underestimated true ACL reinjury incidence. N/A, not applicable; NR, not reported.

Average age at primary ACLR was used when age at both primary and revision ACLR was reported.

The population size above reflects the total number of study participants. A population of 2130 was evaluated for reinjury outcomes.

The authors reported a rate of 23%, but we calculated a rate of 25.3% based on reported ipsilateral and contralateral reinjury rates.18

All subjects were <16 years old at primary ACLR.

Means were calculated from all available data (excluding Ahldén et al,2 Andernord et al,3 Bourke et al [2012b],5 Paterno et al [2012],50 and Salmon et al53).

Pooled total and contralateral reinjury rates were calculated from 7 studies that reported both ipsilateral and contralateral injury rates. The pooled ipsilateral reinjury rate was calculated from 14 studies that reported ipsilateral reinjury rates. Ahldén et al,2 Andernord et al,3 Bourke et al (2012b),5 Paterno et al (2012),50 and Salmon et al53 were excluded, as these study cohorts were included in other studies that were used in the calculation.

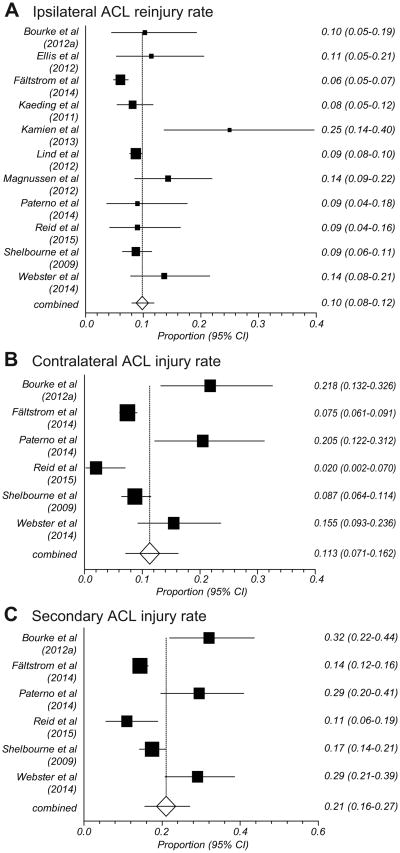

Table 4 shows the studies in which secondary ACL injury rates were separately reported for a younger cohort (<25 years). The pooled ipsilateral ACL reinjury rate across 11 studies was 10% (95% CI, 7%-14%; I2 = 94%) (Figure 3). For the 6 studies6,14,51,52,56,61 that reported both ipsilateral and contralateral ACL injury data, the pooled secondary ACL injury rate was 21% (95% CI, 16%-27%; I2 = 86%) in the younger group, with a contralateral injury rate of 11% (95% CI, 7%-16%; I2 = 87%). Both Paterno et al50,51 and Bourke et al6 showed contralateral injury rates to be relatively higher than ipsilateral reinjury, whereas there was little difference between these rates in the remaining studies.

Table 4. Age-Specific Reinjury Ratesa.

| Study | OutcomeMeasure | Follow-up, mo | Population Average Age, yb | Reinjury Rate in Whole Study Population, % | Reinjury in the High-Risk Age Range | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Total | Ipsilateral | Contralateral | High-Risk Age, y | Total Rate, % | Ipsilateral Rate, % | Contralateral Rate, % | ||||

| Ahldén et al2 | Surgery | 60 | 25.3 | 9.1 | 4.1 | 5.0 | 15-18 (soccer players) | 16.7 | 9.1 | 7.6 |

| Andernord et al3 | Surgery | 24 | 27.4 | N/A | 1.8 | NR | 13-19 | N/A | 3.5 | NR |

| Bourke et al (2012a)6c | Injury | 180 | 29 | 25.3 | 11.1 | 14.1 | ≤18 | 32.1 | 10.3 | 21.8 |

| Bourke et al (2012b)5 | Injury | 180 | 25.8 | 27.4 | 17.7 | 9.7 | ≤18 | N/A | 34.2 | NR |

| Ellis et al12 | Surgery | 50.4 | 16 | N/A | 11.4 | NR | ≤18 | N/A | 11.4 | NR |

| Fältström et al14 | Surgery | 60 | 26.7 | 6.2 | 3.4 | 2.8 | <16 | 12.6 | 6.0 | 6.5 |

| Kaeding et al23 | Surgery | 24 | 26.6 | N/A | 4.9 | NR | 10-19 | N/A | 8.2 | NR |

| Kamien et al26 | Injury | 24 | 28.0 | N/A | 15.3 | NR | <25 | N/A | 25.0 | NR |

| Lind et al32 | Surgery | 60 | NR | N/A | 4.7 | NR | <20 | N/A | 8.7 | NR |

| Magnussen et al34 | Surgery | 14 | 25.0 | N/A | 7.0 | NR | <20 | N/A | 14.3 | NR |

| Paterno et al (2012)50 | Injury | 12 | 16.3 | 25.4 | 6.3 | 19.0 | 10-25 | 25.4 | 6.3 | 19.0 |

| Paterno et al (2014)51 | Injury | 24 | 17.1 | 29.5 | 9.0 | 20.5 | 10-25 | 29.5 | 9.0 | 20.5 |

| Reid et al52 | Surgery | 48 | 20.5d | 11 | 9 | 2 | <16 | 11 | 9 | 2 |

| Shelbourne et al56 | Injury | 60 | 21.6 | 9.6 | 4.3 | 5.3 | <18 | 17.4 | 8.7 | 8.7 |

| Webster et al61 | Injury | 60 | 28.0 | 12.0 | 4.5 | 7.5 | <20 | 29.1 | 13.6 | 15.5e |

| Meanf | 54.9 | 23.5 | ||||||||

| Participants used in meta-analysis, ng | 2140 | 9098 | 2140 | |||||||

Population means for follow-up time and age and the number of participants used in meta-analyses are presented here. Studies were excluded from Table 4 if they did not report age-specific injury rates. Two studies measured surgical intervention as the outcome measure. N/A, not applicable; NR, not reported.

Average age at primary ACLR was used when age at both primary and revision ACLR was reported.

Rates were calculated using survival percentages provided for those subjects ≤18 years old.

All subjects were <16 years old at primary ACLR.

Webster et al61 reported a rate of 16% for contralateral ACL injury in patients <18 years calculated using n = 107 but calculated the total reinjury rate in patients <18 with n = 110. We chose to report the contralateral injury rate with n=110 for consistency with the total reinjury calculation within the article.

Means were calculated from all available data (excluding Ahldén et al2, Andernord et al3, Bourke et al [2012b]5, and Paterno et al [2012]50).

Pooled total and contralateral reinjury rates were calculated from 6 studies that reported both ipsilateral and contralateral injury rates (excluding Ahldén et al2 and Paterno et al [2012]50). The pooled ipsilateral reinjury rate was calculated from 11 studies that reported ipsilateral reinjury rates. Ahldén et al2, Bourke et al (2012b),5 Fältström et al14, and Paterno et al (2012)50 were excluded, as these study cohorts were included in other studies that were used in the calculation.

Figure 3.

Pooled reinjury rates for subjects <25 years old. (A) Ipsilateral anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reinjury rate from 11 studies. Four studies2,5,14,50 were excluded from the calculations, as their populations were included in other studies. (B) Contralateral ACL injury rate and (C) secondary ACL injury rate from 6 studies. Two studies2,50 were excluded from the calculations in (B) and (C), as their populations were included in other studies.

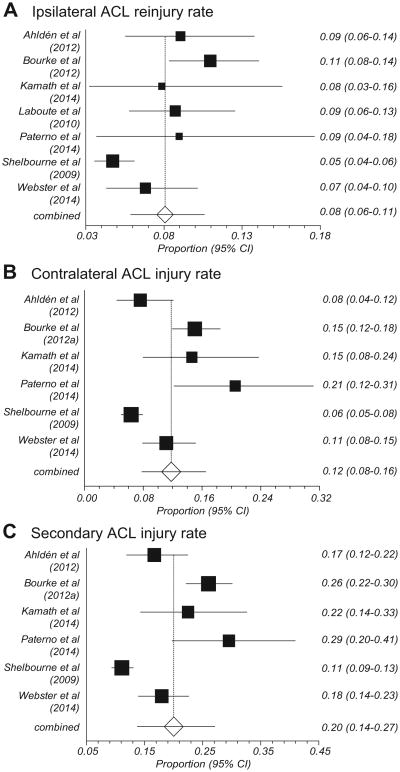

All studies that reported ACL injury rates for athletes who returned to sports are shown in Table 5. The pooled secondary ACL injury rate (Figure 4) calculated from 6 studies2,6,25,51,56,61 was 20% (95% CI, 14%-27%; I2 = 92%). Ipsilateral reinjury and contralateral injury rates were 8% (95% CI, 6%-11%; I2 = 75%) and 12% (95% CI, 8%-16%; I2 = 88%), respectively. Along with the Paterno et al studies,50,51 3 more studies6,25,53 reported contralateral ACL injury rates equal to or greater than ipsilateral reinjury rates.

Table 5. Return-to-Play Reinjury Ratesa.

| Study | Outcome Measure | n | Follow-up, mo | Reinjury Rate, % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Total | Ipsilateral | Contralateral | ||||

| Ahlden et al2 b | Surgery | 210 | 60 | 16.7 | 9.1 | 7.6 |

| Bourke et al (2012a)6c | Injury | 493 | 180 | 26.0 | 11.0 | 15.0 |

| Kamath et al25 | Injury | 89 | 37 | 22.5 | 7.9 | 14.6 |

| Laboute et al28 | Injury | 298 | 48 | N/A | 8.7 | N/A |

| Paterno et al (2012)50 b | Injury | 63 | 12 | 25.4 | 6.3 | 19.0 |

| Paterno et al (2014)51 b | Injury | 78 | 24 | 29.5 | 9.0 | 20.5 |

| Salmon et al53 b | Injury | 321d | 60 | 18.5 | 8.0 | 10.5 |

| Shelbourne et al56 b | Injury | 1148e | 60 | 11.1 | 4.7 | 6.4 |

| Webster et al61 b | Injury | 323d | 60 | 20.0 | 11.6 | 6.6 |

| Mean | 70.2 | |||||

| Participants used in meta-analysis, nf | 2341 | 2639 | 2341 | |||

Population mean follow-up time and the number of participants used in the meta-analyses are presented here. Studies were excluded from Table 5 if they did not report data on reinjury after return to play. The mean was calculated from the 6 studies that reported both ipsilateral and contralateral injury rates (Laboute et al,28 Paterno et al [2012],50 and Salmon et al53 were not included). One study measured surgical intervention as the outcome measure. N/A, not applicable.

Studies in which patients returned to high-risk (cutting/pivoting/jumping) sports.

Return-to-play data were calculated using survival percentages provided for those returning to preinjury sports.

Two different population sizes were reported for ipsilateral reinjury and contralateral injury, respectively; an average is listed here.

Population size was calculated using reported numbers of patients in the 3 reported age groups and reported percentages of each group that returned to sport.

Pooled total and contralateral reinjury rates were calculated from 6 studies that reported both ipsilateral and contralateral injury rates. The pooled ipsilateral reinjury rate was calculated from 7 studies that reported ipsilateral reinjury rates. Paterno et al (2012)50 and Salmon et al53 were excluded, as these study cohorts were included in other studies that were used in the calculation.

Figure 4.

Pooled reinjury rates for subjects who returned to sports. Two studies50,53 in were excluded from these calculations, as their populations were included in other studies. (A) Ipsilateral anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reinjury rate from 7 studies and (B) contralateral ACL injury rate and (C) secondary ACL injury rate from 6 studies.

Table 6 shows studies that report reinjury data from young athletes (<25 years old) who return to high-risk sports after ACL injury and reconstruction. For this subgroup, the pooled secondary ACL injury rate was 23% (95% CI, 16%-30%; I2 = 79%), with an ipsilateral reinjury rate of 10% (95% CI, 8%-12%; I2 = 23%) and a contralateral injury rate of 12% (95% CI, 8%-17%; I2 = 76%) (Figure 5). Figure 6 summarizes the total secondary ACL injury rates across each of the subgroup meta-analyses.

Table 6. Younger Patients and Return to Play in High-Risk Sports Reinjury Ratesa.

| Study | Outcome Measure | n | Follow-up, mo | High-Risk Age, y | Reinjury Rate, % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Total | Ipsilateral | Contralateral | |||||

| Ahldén et al2 | Surgery | 210 | 60 | 15-18 | 16.7 | 9.1 | 7.6 |

| Paterno et al (2012)50 | Injury | 63 | 12 | 10-25 | 25.4 | 6.3 | 19.0 |

| Paterno et al (2014)51 | Injury | 78 | 24 | 10-25 | 29.5 | 9.0 | 20.5 |

| Shelbourne et al56 b | Injury | 528 | 60 | <18 | 17.4 | 8.7 | 8.7 |

| Webster et al61 | Injury | 97 | 36 | <20 | 30.9 | 15.5 | 15.5 |

| Mean | 51.0 | ||||||

| Participants used in meta-analysis, nc | 913 | 913 | 913 | ||||

Mean follow-up time and the number of participants used in meta-analyses for return to play in high-risk (pivoting/cutting/jumping) sports are presented here. Studies were excluded from Table 6 if they did not report age-specific data on reinjury rates (including contralateral anterior cruciate ligament injury) after return to play in high-risk sports. Mean follow-up was calculated from 4 studies (Paterno et al [2012]50 was not included). One study measured surgical intervention as the outcome measure.

The same proportion of patients (92%) <18 years old returned to high-risk sport as the proportion of patients who suffered an index injury during high-risk sport (92%).

Figure 5.

Pooled reinjury rates for subjects <25 years old who returned to sports from 5 studies. One study50 was excluded from these calculations, as its population was included another study. (A) Ipsilateral anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reinjury rate, (B) contralateral ACL injury rate, and (C) secondary ACL injury rate.

Figure 6.

Pooled secondary anterior cruciate ligament injury rates from respective patient groups.

Discussion

This systematic review highlights age and activity level as key risk factors in reinjury after ACLR. Specifically, patients of younger age (<25 years) and those who return to a high level of activity, especially in high-risk cutting/pivoting sports such as soccer, are at increased risk. These factors place ACLR patients at a significantly higher risk for both graft rupture and contralateral ACL injury when compared with their noninjured counterparts. Epidemiological studies have reported primary ACL injury rates of 0.6% and 0.8% in populations of adolescents48 and high school basketball players,38 respectively. Comparing these rates to the 23% rate of secondary ACL injury calculated in this meta-analysis, young athletes who return to sport are at approximately 30 to 40 times greater risk of sustaining an ACL injury during sport relative to their uninjured counterparts.

The aggregate pooled rate of repeat ACL injury found in this review is 15% (Figure 2). This rate was calculated from 7 studies that provided data on both ipsilateral and contralateral injuries. The aggregate pooled contralateral injury rate was 8%. When including the 7 studies that reported only ipsilateral injuries, the incidence rate of ipsilateral reinjury was 7%. The total reinjury rate in our review is within the wide spectrum of values found in the literature ranging from 3% to 29.5%.27,31,51,62 This wide range is likely due to data that include ACL injury in all age ranges, follow-up periods, and activity levels. Studies often include athletes who do not RTP, therefore not placing their graft or contralateral extremity at increased risk. In addition, studies differ in outcome measures (Table 3), with many using graft/native ACL injury, while others collect surgical data on revision or contralateral ACLR. Aggregated rates should be interpreted with the understanding that those studies that collect data on surgical interventions only may fail to capture a subset of patients who sustain a secondary ACL injury but chose nonoperative management such as activity modification over surgical management.

Unfortunately, reinjury is not just limited to the operated limb. As shown in Tables 3 to 6 and Figures 2 to 5, current evidence shows that, on average, rates of contralateral ACL injury exceed the rates of ipsilateral graft rupture after ACLR, regardless of age or activity level. The causes of contralateral ACL tear are unclear but likely multifactorial. Risk factors for bilateral ACL tears have been hypothesized to include notch width, sex, knee alignment, and/or genetic predisposition.18,39,57 However, the increased incidence of contralateral injury may be due to the persistence of the same risk factors that predispose patients to initial injury,21 graft type,31 remaining functional deficits at the time of RTP,54 or altered motor patterns that protect the reconstructed knee but increase stress on the contralateral limb.13,49 Increased contralateral injury is especially prevalent in females, as highlighted by Paterno et al.50,51 Although not specifically addressed in this review, females may be particularly at risk for deficits in the uninvolved limb at the time of injury or as a result of the development of compensatory mechanisms during rehabilitation. Additional measures should be taken during the rehabilitation of this group to address impairments in the uninvolved limb after ACLR. More long-term research studies are needed to identify causes prospectively. This type of analysis is often not possible in a review such as this.

Age and Activity Level: Risk Factors for Secondary ACL Injury

The causes of graft failure may include age, high-risk sports participation, incomplete healing, and inadequate rehabilitation. Of particular interest is the role of age in graft rupture. It is often theorized that younger individuals are more susceptible to ACL injuries because there is greater ligament length due to the rapidly developing bones.10 As a result, when ACL rupture does occur in the young, athletic patient, surgical treatment of an ACL tear is commonly performed to restore knee stability, reducing the risks of subsequent injury and the progression of degenerative changes.

Many reports have shown that there is value to ACL reconstruction after the age of 30 to 40 years.3,23,29 However, the same available literature is not as prevalent for patients aged <20 to 25 years. An examination of the reviewed studies that reported age-specific injury incidence rates (Table 4) reveals that patients <20 to 25 years old experience further ACL injury at a greater rate relative to the overall population. While studies that include only young athletic populations who return to their previous activity level are rare, registries with large data pools are beginning to emerge.2,3,14,27,32,35 These studies are able to analyze results by age and activity categories, thus shedding light on those at highest reinjury risk. A recent article reporting data from the Kaiser Permanente ACLR registry concluded that age had a significant effect on both revision ACLR and contralateral ACLR.35 For each year increase in age, a lower risk of revision ACLR (8% per year) and contralateral ACLR (4% per year) was noted. Kaeding et al23 found a similar trend in the ipsilateral knee, reporting that a given patient is 2.3 times more likely to undergo revision ACLR than a patient who is 10 years older. Understanding specific patient risk factors is necessary so physicians can counsel their patients appropriately on reinjury risk as well as take steps to prevent reinjuries.

Paterno et al (2012)50 reviewed incidence rates of reinjury in young, active patients after they had returned to sport after ACLR. It is thought that these patients may be at increased reinjury risk since they are more likely to return to high-risk activities after ACLR.2,3,25,56,61 Shelbourne et al56 reported a 92% return to high-risk sports among those <18 years old. Similarly, Webster et al61 reported that 88% of patients <20 years old returned to these sports. Our examination of return to sport and associated ACL reinjury rates can be found in Figures 4 and 5. Aggregated results from our review suggest that patients who return to sports have a higher reinjury rate than those who do not.

We found the greatest incidence rate of ACL reinjury (23%) when synthesizing the results from studies that analyzed young patients (<20-25 years old) who return to high-risk sports (Table 6; Figure 5). Shelbourne et al55,56 included a small subset of subjects who did not return to sports within their age-specific results reported here, and therefore, these rates may actually be less than the true reinjury rates within this high-risk group. Furthermore, Ahldén et al2 reported specific subgroup results on 15- to 18-year-old soccer players only, excluding those who returned to other high-risk sports.

As risk related to patient age is not modifiable, we must look for other potentially modifiable characteristics within the younger patient population. Laboute et al28 reported that, in a subset of 11 patients who were told to try less risky sports (“pivoting with no contact,” “weightbearing with no pivoting,” and “nonweightbearing”) after ACLR, no further injuries occurred. While statistical comparison was not made between this group and the patients who returned to high-risk sports, these data provide insight that activity modification may provide a viable strategy for patients to avoid future injury while maintaining some level of participation in athletics. This method may have limited use, however, as many patients have goals to return to previous levels of play in sports in which they played before injury.

Modifications to RTP guidelines may have great potential to reduce reinjury risk and improve performance after ACLR. Even though RTP guidelines exist in the literature, there is still no consensus on which is best, and many physicians continue to clear patients based on time from surgery or personal experience.47 A number of variations in RTP guidelines exist, as evidenced by the studies included in this review. The most widely accepted guideline was published in 2009 by the AAOS.1 According to the AAOS, evidence is lacking to suggest that RTP be based on a timeline that specifies a wait time between injury/surgery and returning to normal, functional activity. The guideline makes the same statement regarding the use of functional goals to be met before RTP. However, support has grown recently for the latter approach of achieving certain levels of functional criteria before return to full activity.6,30,45,63 To summarize the current literature, a hamstring-to-quadricep strength ratio of at least 85% of baseline is recommended before athletes returning to cutting, pivoting, and jumping sports. The patient's involved leg should be within 90% symmetry of their uninvolved leg for time and distance for single-legged, crossover, and triple hops for distance, as well as a 6-m timed hop test.17,51,61

Despite these guidelines, there is still a significant risk of reinjury, especially early after RTP from an ACLR. Paterno et al51 (2014) found that more than 30% of repeat injuries occur within 20 games or practice sessions of RTP. Laboute et al28 also noted that patients who returned to sport in <7 months were more likely to be reinjured than those who returned after 7 months. This may indicate that while the athlete is able to perform the above tasks, they still have not recovered completely. This notion is supported by existing literature that has described functional asymmetries/deficits that persist after RTP in ACL-reconstructed athletes.30,36,45,49 The reconstructed knee in particular may be at increased risk early after RTP relative to the contralateral knee.6,53 Further investigation is warranted to look more closely at RTP guidelines to aid in the development of standardized therapy protocols that minimize the risk of athletes returning to sports with persistent deficits.

The key to preventing injury and subsequent repeat injury may lie in the initiation of proper training at a young age. Literature has illustrated that neuromuscular training has been effective at preventing ACL injuries.20,37,40,44 As most training does not start early enough,40 the post-surgical rehabilitation program may be an ideal time to emphasize key movements including proper landing and pivoting mechanics. Using training techniques such as integrative neuromuscular training, which has been successful in reducing primary risk factors and injury incidence in young athletes,43,42,44 may provide opportunities to improve strength and biomechanics19,41 that contribute to a lower incidence of repeat injury in high-risk populations.9,46 More data are needed to evaluate the exact frequency of repeat injury, but at the same time, post-ACLR rehabilitation techniques need to be reexamined to note the cause of variation found in this analysis and also what exercises need to be emphasized.

Limitations

There are a number of limitations associated with this review. One limitation is the difficulty of ensuring that all ipsilateral and contralateral injuries were identified. Inadequate reporting of secondary injuries can lead to a misrepresentation of the injury rates. Another limitation is the lack of standardized data across studies regarding age, sex, follow-up time, and activity level/AEs at the time of reinjury. As mentioned above, outcome measures varied and some studies used surgical outcome measures, which may underestimate the true incidence of ACL reinjury.

Graft type, size, and surgical techniques also varied among the studies reviewed here. Many studies used single-surgeon data, and others relied on data from national registers that come from many different surgeons. We recognize that graft type and size may play roles in reinjury after ACLR4,23; however, these factors were beyond the scope of our review. That being said, a recent review by Wasserstein et al60 found that allografts were more likely than autografts to fail in patients <25 years who return to high levels of activity. Our current estimate of reinjury in this young and active population is based on 4 studies that used autografts at rates of 92.3%,51 .96.1%,2 100%,56 and 100%.61 Therefore, we believe that our estimate is firmly based on the current best surgical practices.

Sex may also influence both subjective and objective outcomes after primary ACLR. A recent meta-analysis by Tan et al58 indicates that females have greater knee laxity and lower Lysholm and Tegner activity scores compared with males. In addition, females return to sports less frequently than males do and have increased rates of revision ACLR.58 These outcome disparities among the 2 sexes likely play a significant role in reinjury in young, athletic populations. However, individual analysis of the sexes was not completed in the present review as a number of the included studies did not report the information necessary to complete this analysis.

Concurrently, rehabilitation methods and progressions, as well as RTP guidelines, differ among the studies reviewed. Deficient RTP guidelines may allow athletes to return to sports participation before regaining functional symmetry, subsequently increasing their risk of reinjury. While we understand that these methodological variations may have partially contributed to differences in incidence rates between individual studies, we believe that the high level of evidence and comprehensive analysis presented in this review will provide medical professionals and patients with a widely applicable understanding ACL reinjury.

Conclusion

This systematic review reported results after ACLR in the population as a whole, as well as in the younger population and those who return to play sports. A pooled total ACL reinjury rate for all patients was found to be 15%, while those <20 to 25 years old had a rate of 21%. The rate of secondary ACL injury among patients who return to sports was 20%. Most concerning, the incidence of reinjury in young patients (<20-25 years) who returned to high-risk sport was 23%. This means that nearly 1 in 4 young athletic patients who sustain an ACL injury and return to high-risk sport will go on to sustain another ACL injury at some point in their career, and they will likely sustain it early in the RTP period. Compared with uninjured adolescents, a young athlete who returns to sport after ACLR may be at a 30 to 40 times greater risk of ACL injury. These data indicate that activity modification, improved rehabilitation and RTP guidelines, and the use of integrative neuromuscular training may help athletes more safely reintegrate into sport and reduce second injury in this at-risk population.

Footnotes

The authors declared that they have no conflicts of interest in the authorship and publication of this contribution.

References

- 1.Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury: Surgical Considerations. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahldén M, Samuelsson K, Sernert N, Forssblad M, Karlsson J, Kartus J. The Swedish National Anterior Cruciate Ligament Register: a report on baseline variables and outcomes of surgery for almost 18,000 patients. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(10):2230–2235. doi: 10.1177/0363546512457348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andernord D, Desai N, Bjornsson H, Ylander M, Karlsson J, Samuels-son K. Patient predictors of early revision surgery after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a cohort study of 16,930 patients with 2-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(1):121–127. doi: 10.1177/0363546514552788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borchers JR, Pedroza A, Kaeding C. Activity level and graft type as risk factors for anterior cruciate ligament graft failure a case-control study. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(12):2362–2367. doi: 10.1177/0363546509340633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bourke HE, Gordon DJ, Salmon LJ, Waller A, Linklater J, Pinczewski LA. The outcome at 15 years of endoscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using hamstring tendon autograft for ‘isolated’ anterior cruciate ligament rupture. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(5):630–637. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.94B5.28675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bourke HE, Salmon LJ, Waller A, Patterson V, Pinczewski LA. Survival of the anterior cruciate ligament graft and the contralateral ACL at a minimum of 15 years. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(9):1985–1992. doi: 10.1177/0363546512454414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brophy RH, Stepan JG, Silvers HJ, Mandelbaum BR. Defending puts the anterior cruciate ligament at risk during soccer: a gender-based analysis. Sports Health. 2015;7(3):244–249. doi: 10.1177/1941738114535184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deacon A, Bennell K, Kiss ZS, Crossley K, Brukner P. Osteoarthritis of the knee in retired, elite Australian Rules footballers. Med J Aust. 1997;166(4):187–190. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1997.tb140072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Di Stasi S, Myer GD, Hewett TE. Neuromuscular training to target deficits associated with second anterior cruciate ligament injury. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2013;43(11):777–792. A771–A711. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2013.4693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dodwell ER, LaMont LE, Green DW, Pan TJ, Marx RG, Lyman S. 20 years of pediatric anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in New York State. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(3):675–680. doi: 10.1177/0363546513518412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52(6):377–384. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.6.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ellis HB, Matheny LM, Briggs KK, Pennock AT, Steadman JR. Outcomes and revision rate after bone-patellar tendon-bone allograft versus autograft anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in patients aged 18 years or younger with closed physes. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(12):1819–1825. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2012.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ernst GP, Saliba E, Diduch DR, Hurwitz SR, Ball DW. Lower extremity compensations following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Phys Ther. 2000;80(3):251–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fältström A, Hägglund M, Magnusson H, Forssblad M, Kvist J. Predictors for additional anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: data from the Swedish national ACL register [published online November 1, 2014. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. doi: 10.1007/s00167-014-3406-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ford KR, Myer GD, Toms HE, Hewett TE. Gender differences in the kinematics of unanticipated cutting in young athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37(1):124–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freedman KB, Glasgow MT, Glasgow SG, Bernstein J. Anterior cruciate ligament injury and reconstruction among university students. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;356:208–212. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199811000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grindem H, Logerstedt D, Eitzen I, et al. Single-legged hop tests as predictors of self-reported knee function in nonoperatively treated individuals with anterior cruciate ligament injury. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(11):2347–2354. doi: 10.1177/0363546511417085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harner CD, Paulos LE, Greenwald AE, Rosenberg TD, Cooley VC. Detailed analysis of patients with bilateral anterior cruciate ligament injuries. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22(1):37–43. doi: 10.1177/036354659402200107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hewett TE, Di Stasi SL, Myer GD. Current concepts for injury prevention in athletes after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(1):216–224. doi: 10.1177/0363546512459638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hewett TE, Ford KR, Myer GD. Anterior cruciate ligament injuries in female athletes: part 2, a meta-analysis of neuromuscular interventions aimed at injury prevention. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(3):490–498. doi: 10.1177/0363546505282619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hewett TE, Myer GD, Ford KR, et al. Biomechanical measures of neuromuscular control and valgus loading of the knee predict anterior cruciate ligament injury risk in female athletes: a prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(4):492–501. doi: 10.1177/0363546504269591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Irrgang JJ, Anderson AF, Boland AL, et al. Development and validation of the International Knee Documentation Committee subjective knee form. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(5):600–613. doi: 10.1177/03635465010290051301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaeding CC, Aros B, Pedroza A, et al. Allograft versus autograft anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: predictors of failure from a MOON prospective longitudinal cohort. Sports Health. 2011;3(1):73–81. doi: 10.1177/1941738110386185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaeding CC, Pedroza AD, Reinke EK, Huston LJ, Consortium M, Spindler KP. Risk factors and predictors of subsequent ACL injury in either knee after ACL reconstruction: prospective analysis of 2488 primary ACL reconstructions from the MOON cohort. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(7):1583–1590. doi: 10.1177/0363546515578836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kamath GV, Murphy T, Creighton RA, Viradia N, Taft TN, Spang JT. Anterior cruciate ligament injury, return to play, and reinjury in the elite collegiate athlete analysis of an NCAA Division I cohort. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(7):1638–1643. doi: 10.1177/0363546514524164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kamien PM, Hydrick JM, Replogle WH, Go LT, Barrett GR. Age, graft size, and Tegner activity level as predictors of failure in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with hamstring autograft. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(8):1808–1812. doi: 10.1177/0363546513493896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kvist J, Kartus J, Karlsson J, Forssblad M. Results from the Swedish national anterior cruciate ligament register. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(7):803–810. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2014.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laboute E, Savalli L, Puig P, et al. Analysis of return to competition and repeat rupture for 298 anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions with patellar or hamstring tendon autograft in sportspeople. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2010;53(10):598–614. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Legnani C, Terzaghi C, Borgo E, Ventura A. Management of anterior cruciate ligament rupture in patients aged 40 years and older. J Orthop Traumatol. 2011;12(4):177–184. doi: 10.1007/s10195-011-0167-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lepley LK. Deficits in quadriceps strength and patient-oriented outcomes at return to activity after ACL reconstruction: a review of the current literature. Sports Health. 2015;7(3):231–238. doi: 10.1177/1941738115578112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leys T, Salmon L, Waller A, Linklater J, Pinczewski L. Clinical results and risk factors for reinjury 15 years after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective study of hamstring and patellar tendon grafts. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(3):595–605. doi: 10.1177/0363546511430375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lind M, Menhert F, Pedersen AB. Incidence and outcome after revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction results from the Danish Registry for Knee Ligament Reconstructions. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(7):1551–1557. doi: 10.1177/0363546512446000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lippe J, Armstrong A, Fulkerson JP. Anatomic guidelines for harvesting a quadriceps free tendon autograft for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(7):980–984. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Magnussen RA, Lawrence JT, West RL, Toth AP, Taylor DC, Garrett WE. Graft size and patient age are predictors of early revision after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with hamstring autograft. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(4):526–531. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2011.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maletis GB, Inacio MC, Funahashi TT. Risk factors associated with revision and contralateral anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions in the Kaiser Permanente ACLR registry. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(3):641–647. doi: 10.1177/0363546514561745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mattacola CG, Perrin DH, Gansneder BM, Gieck JH, Saliba EN, McCue FC., III Strength, functional outcome, and postural stability after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Athl Train. 2002;37(3):262–268. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McLean SG, Huang X, van den Bogert AJ. Association between lower extremity posture at contact and peak knee valgus moment during sidestepping: implications for ACL injury. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2005;20(8):863–870. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]