Abstract

Clinicians have been aware that posterior dental particulate-filled composites (PFCs) have many placement disadvantages and indeed fail clinically at an average rate faster than amalgam alloys. Secondary caries is most commonly identified as the chief failure mechanism for both dental PFCs and amalgam. In terms of a solution, fiber-reinforced composites (FRCs) above critical length (Lc) can provide mechanical property safety factors with compound molding packing qualities to reduce many problems associated with dental PFCs. Discontinuous chopped fibers above the necessary Lc have been incorporated into dental PFCs to make consolidated molding compounds that can be tested for comparisons with PFC controls on mechanical properties, wear resistance, void-defect occurrence and packing ability to reestablish the interproximal contact. Further, imaging characterizations can aid in providing comparisons for FRCs with other materials using scanning electron microscopy, atomic force microscopy and photographs. Also, the amalgam filling material has finally been tested by appropriate ASTM flexural bending methods that eliminate shear failure associated with short span lengths in dental standards for comparison with dental PFCs to best explain increased longevity for the amalgam when compared to dental PFCs. Accurate mechanical tests also provide significant proof for superior advantages with FRCs. Mechanical properties tested included flexural strength, yield strength, modulus, resilience, work of fracture, critical strain energy release and critical stress intensity factor. FRC molding compounds with fibers above Lc extensively improve all mechanical properties over PFC dental paste and over the amalgam for all mechanical properties except modulus. The dental PFC also demonstrated superior mechanical properties over the amalgam except modulus to provide a better explanation for increased PFC failure due to secondary caries. With lower PFC modulus, increased adhesive bond breakage is expected from greater interlaminar shearing as the PFC accentuates straining deflections compared to amalgam at the higher modulus tooth enamel margins during loading. Preliminary testing for experimental FRCs with fibers above Lc demonstrated three-body wear even less than enamel to reduce the possibility of marginal ditching as a factor in secondary caries seen with both PFCs and amalgam. Further, FRC molding compounds with chopped fibers above Lc properly impregnated with photocure resin can pack with condensing forces higher than the amalgam to eliminate voids in the proximal box commonly seen with dental PFCs and reestablish interproximal contacts better than amalgam. Subsequent higher FRC packing forces can aid in squeezing monomer, resin, particulate and nanofibers deeper into adhesive mechanical bond retention sites and then leave a higher concentration of insoluble fibers and particulate as moisture barriers at the cavity margins. Also, FRC molding compounds can incorporate triclosan antimicrobial and maintain a strong packing condensing force that cannot be accomplished with PFCs which form a sticky gluey consistency with triclosan. In addition, large FRC packing forces allow higher concentrations of the hydrophobic ethoxylated bis phenol A dimethacrylate (BisEMA) low-viscosity oligomer resin that reduces water sorption and solubility to then still maintain excellent consistency. Therefore, photocure molding compounds with fibers above Lc appear to have many exceptional properties and design capabilities as improved alternatives for replacing both PFCs and amalgam alloys in restorative dental care.

Keywords: Fiber-Reinforced Composite (FRC), Critical Length (Lc), Particulate-filled composite (PFC), Amalgam

Introduction

A breakthrough for a brand new class of fiber-reinforced composites (FRCs) above critical length (Lc) is identified by a molding compound material with fibers on the order of about 100 times longer than previous commercial dental composite products now available through the dental manufacturing industry. Dental FRCs and satisfying micromechanics above the critical length Lc [1, 2] have shown dramatic statistically significant improvements in mechanical test results over two conventional dental composites that are particulate-filled composites (PFCs) as either 3M Corporation Z100®, Kerr Corporation Herculite XRV® [1-6] or also a dental PFC with microfibers as Jeneric Pentron Alert® that can not fulfill Lc [2-4]. In addition, FRCs with fibers above Lc have statistically significantly improved all mechanical properties tested except modulus over the amalgam Kerr Corporation Tytin® [6], Table 1. Mechanical testing increases over dental PFCs by FRCs include flexural strength, modulus and flexural yield strength along with fracture toughness results for resilience, work of fracture (WOF), critical strain energy release (SIc), critical stress intensity factor (KIc) and Izod impact toughness [1-6].

Table 1. Averages and T-test (p value) Comparisons Between Composites and Amalgam.

| Fiber Length (mm) 30wt% (28.2 Vf) | Flexural Strength (MPa) | Modulus (GPa) | Yield Strength (MPa) | Resilience (kJ/m2) | WOF (kJ/m2) |

SIc (kJ/m2) |

KIc (MPa*m1/2) | Strain at Peak Load |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0 mm (PFC) Z100® 3M | 117.6 (0.0012) | 19.5 (0.00102) | 95.4 (0.01337) | 3.03 (0.01882) | 4.48 (5.1×10-5) | 0.036 (0.16055) | 1.71 (0.06584) | 0.0079 (0.9740) |

| 0.5 mm (FRC) | 113.8 (0.1399) | 23.0 (0.0008) | 92.8 (0.0372) | 2.35 (0.0400) | 3.91 (0.0984) | 0.075 (0.1794) | 1.93 (0.07953) | 0.0062 (0.9189) |

| 1.0 mm (FRC) | 173.6 (0.00318) | 26.2 (0.001875) | 126.1 (0.00018) | 3.84 (0.00083) | 8.7 (0.01879) | 0.097 (0.0584) | 2.77 (0.00797) | 0.0084 (0.2993) |

| 2.0 mm (FRC) | 373.9 (5.2×10-5) | 34.0 (0.00116) | 329.8 (0.00168) | 19.7 (0.00287) | 28.2 (0.00046) | 1.882 (0.0338) | 11.01 (0.00579) | 0.0121 (0.1290) |

| 3.0 mm (FRC) | 374.9 (2.2×10-8) | 31.5 (0.01236) | 343.5 (0.00014) | 23.3 (0.00348) | 30.1 (4.2×10-5) | 2.4 (0.00296) | 12.01 (3.89×10-5) | 0.0131 (0.0677) |

| Alert® (PFC) with microfibers | 90.4 (0.7057) | 17.6 (0.00019) | 62.3 (0.9791) | 1.52 (0.0440) | 3.23 (0.0077) | 0.034 (0.2950) | 1.33 (0.7523) | 0.0069 (0.7130) |

| Amalgam Tytin® | 86.0 | 43.6 | 62.6 | 0.67 | 1.40 | 0.013 | 0.91 | 0.0078 |

In terms of the primary industrial development, FRCs have been a revolutionary advancement for Materials Science particularly in the sophisticated aerospace field mainly due to the low density and combined high mechanical properties for fibers that can produce strengths stronger than steel and specific strengths much stronger than steel [7, 8], Table 2. For example, E-glass and quartz fiber can have specific strengths approximately 4.5 and 9 times higher than steel respectively. Through independent materials improvement, photocure dental PFCs have been developed adequately commercially whereby in the United States PFCs have increased use in larger load-bearing molars [9, 10] and surpassed amalgam for the number of fillings placed in the late 1990s [9]. However, although it is known that the critical obstacle for both dental PFCs and amalgam is chiefly secondary caries, PFCs have greater failure rates compared to the amalgam [10-35]. Also, filling fracture was another failure mechanism commonly observed [16, 21, 26, 27, 32, 33]. In addition, wear rates that create a trench at the filling margins have been higher for dental PFCs than amalgams [9, 36] where wear for dental PFCs increases with wider cavity preparations with less protection from enamel that “shelters” the dental composite [37].

Table 2. Specific Properties for E-Glass, Quartz Fiber and High-Strength Steel.

| Material | Specific Gravity (g/cm3) | Tensile Strength (GPa) | Specific Strength (GPa) | Modulus of Elasticity (GPa) | Specific Modulus (GPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-Glass | 2.58 | 3.45 | 1.34 | 72.5 | 28.1 |

| Quartz Fiber | 2.2 | 6.0 | 2.73 | 72 | 32.7 |

| Steel Wire | 7.9 | 2.39 | 0.30 | 210 | 26.6 |

Evidence Based Randomized Controlled Trials

As best examples to explain superior amalgam longevity when compared to dental PFCs, in parallel randomized controlled trials carried out in Portugal and the United States between five to seven years failure rates were much higher for the dental PFC compared to amalgam [25, 26]. In one high evidenced based randomized controlled trial children were randomly assigned either a PFC or amalgam in posterior permanent teeth for a total of 1,748 restorations over a seven year period [26]. Subsequent failure rates revealed that PFCs were replaced 2.6 times more frequently than amalgam [26]. Further, failure due to secondary caries was 3.5 times greater in PFCs than amalgam [26]. Another randomized controlled trial with 1,262 posterior permanent teeth restorations followed for two to five years also plainly showed that amalgam had a higher survival rate than PFC and that composites fail by secondary caries at a much greater rate than amalgam [25]. Also, PFCs overall required 7 times more repairs than amalgam and at five years 8 times more repair [25]. Differences for failures between amalgams and PFC were more accentuated in large restorations and fillings having more than three surfaces contained with a restorative material [25, 26]. Both randomized controlled trials together have been considered the strongest evidence that amalgams have lower failure rates summarized at 2 to 3 times lower than dental PFCs and that secondary caries occurs at a much greater frequency with dental PFCs than amalgam in permanent posterior restorations [31]. In the summary of main results for a comprehensive review on randomized controlled trials extending at least three years PFCs had almost twice the risk as amalgams for failure and having secondary caries [34]. In a non-loading-type failure investigation, radiographic examination of 14,140 interproximal surfaces discovered that secondary caries was detected 5.4 times more frequently in PFCs than in amalgams [24]. Consequently, PFCs need careful reconsideration involving interproximal restorations [24] while amalgams are preferred in permanent teeth with larger posterior restorations [9, 25, 26, 34]. In point of fact, since 1994 the American Dental Association has periodically warned against not using dental PFCs in load-bearing areas [9, 38, 39]. Related to dental photocure FRC mechanical test improvements, the American Dental Association warning that dental PFCs should not be used in stress bearing areas could be answered by positive results with the extensively large mechanical property increases produced by FRCs with fibers above Lc.

Mechanical Properties

In terms of mechanical properties applying a highly-controlled American Standards Test Methods (ASTM) approach analysis that prevented shear error seen with dental flexural test standards, a well-known dental PFC demonstrated superior properties for all strength and fracture toughness properties compared to a commonly used amalgam [6], Table 1. But, the modulus for the amalgam was superior to the dental PFC at such a noteworthy extent that higher amalgam longevity appears to be explained better in terms of the elastic modulus properties [6]. Marginal interlaminar shear stress by an occlusal masticatory load on filling material next to higher modulus enamel looks to be a significant problem for recurrent decay with low-modulus PFCs that deflect easily by loading [6]. In comparison much higher modulus amalgam fillings are decidedly more rigid against deflection [6]. As the PFC deflection is accentuated during loading compared to amalgam, marginal sealing by adhesive bonds with tooth structure would break more frequently with PFCs than an amalgam seal at the filling margin with the high modulus enamel [6]. Once the PFC filling adhesive bond is broken along the enamel marginal seal, PFCs are more susceptible than a sealed amalgam restoration to well-recognized marginal leakage of fluids. Marginal leakage can then result in subsequent bacterial growth into the open margin and enzymatic breakdown of the adhesive polymer bond leading to secondary caries [10, 32, 40]. Further, low modulus PFC will cause more strain to start polymer matrix microcracking [41, 42]. Actually, loading of a polymer speeds up moisture ingress by opening up polymer voids and starting microcracks that adsorb even more water [41, 42]. Subsequent moisture adsorption negatively damages the polymer matrix with a reduction in modulus, strength and hardness [42]. Related to defects at the margin, in an 8 year clinical study showing composites failed at a 2-3× greater rate than amalgams, significantly fewer coarse particle hybrid dental PFC fillings failed than smaller particle PFCs due to greater strength, higher modulus, less wear and less marginal fracture [18]. Testing to compare conditions between dry and water immersion with nine different PFC materials and approximately 6 samples per group showed that dry conditions provided 81% strength improvement over moisture exposure while smaller particulate filler had lower tensile strength values than larger particulate filler for both conditions [43].

From Table 1 mechanical properties clearly demonstrate that fibers above Lc control FRC material properties. Further, regressions for increasing fiber lengths are highly statistically significant for all experimental results (p< 1.1 ×10-5) [6]. The Lc is a measure of the minimum perfectly aligned fiber dimension needed before maximum fiber stress transfer starts to occur within the cured resin [44-46]. According to the micromechanics in the most common dental photocure polymer matrix the Lc for a 9 μm diameter fiber is approximately 0.5 mm where most of the fiber will debond before the strength of the fiber can start to be utilized [2]. So, although the 0.5 mm fiber length group resulted in light reductions for the average in many mechanical properties compared to the PFC matrix, micromechanics predicts possible full debonding of the fiber before the fiber breaks so that the fiber might be acting as a defect when not longer than Lc [2]. As fiber aspect ratios increase describing increased fiber lengths relative to fiber diameters, strengths (tensile, flexural, yield and fatigue), modulus, and toughness (impact, resilience, WOF, SIc and KIc) all increase [2, 5, 6, 46-49]. Further, less overall polymerization shrinkage occurs with increasing aspect ratio, especially accentuated along the fiber axis [49-51], with lower shrinkage stress and lower creep [49]. Wear rates are lower related to FRC mechanical strength properties that support loading, especially as the fibers lengthen beyond the average plowing groove [52, 53].

Adhesive Bonding

In an adhesive joint, polymer matrix adherends are more sensitive to interlaminar shearing and tensile stresses than metals [41]. Further, the polymer matrix of the adherend may be weaker than the adhesive bond and the limiting factor to interlaminar shearing and tensile stresses, but fibers dominate material properties and probably reduce the influence of the polymer matrix [41]. As described, occlusal loading at a filling margin would produce greater interlaminar shearing with a low modulus PFC than a much higher modulus amalgam. Greater deflections by the PFC compared to the amalgam next to the much stiffer tooth enamel would then have a far greater tendency to break the PFC adhesive marginal bond. To counteract low modulus polymer matrix material deflections at a metal joint, high modulus fibers are often added to the adhesive [41]. Also, polymer matrix adherends are vulnerable to moisture but metals are not susceptible such that moisture is seen on the adhesive stratum and limited to just the uncovered ends of the metal [41]. Because the chief manner for water adsorption in an FRC is through the polymer matrix by diffusion, chopped fibers in a mat carrier are frequently placed by pressure in adhesives to act as moisture barriers and prevent direct moisture uptake into the polymer bond [41]. In addition, microcracking caused by polymer matrix strain deflections increases the rate of moisture ingress and amount of moisture adsorbed [41, 42]. With increasing polarity of the polymer chain, moisture adsorption likewise increases chiefly by diffusion where water molecules go into the polymer and exist in locations between polymer chains that become more separated [54]. As a result, water creates polymer chains that are less entangled and more free to move causing the polymer to soften by plasticization and further hydrolyze [42, 54-56] with a reduction of polymer mechanical properties like strength, modulus and fracture toughness [42, 55, 56]. Polymer mechanical properties can lower even more with moisture due to the presence of voids [55]. Polymer hydrophilic tendencies to adsorb water reduce dental PFC polymer matrix strength following water immersion [57]. Further, dental PFCs have lost significant strength after water storage [43]. Strain-related microcracking of low modulus dental PFCs would also increase moisture adsorption throughout the PFC in addition to the polymer adhesive joint. Recommendations by the American Dental Association not to use dental PFCs in load-bearing areas [9, 38, 39], could be a result of reductions in mechanical strength and other mechanical properties over time due to moisture ingress. Also, deeper larger fillings with more surfaces are considered grounds for using amalgam instead of a PFC [58, 59]. As fillings increase in size more margins are susceptible to larger stresses that would deflect a low modulus PFC and cause shear failure to break an adhesive marginal bond. Accordingly, mechanical properties of the PFCs for strengths and fracture toughness that are superior to the amalgam when tested under atmospheric conditions could change significantly by moisture adsorption in an oral environment with a reduction in mechanical properties. The modulus for dentin at 13.7 GPa [60] is similar to dental PFC moduli so that tooth proprioception should limit loading as some safety factor for PFCs when initially placed. However, as PFC modulus is lost by moisture ingress and microcracking, subsequent strain deflection increases may not be limited by the 13.7 GPa dentin modulus safety factor. Generally, enamel modulus of 48-94 GPa [61, 62] may not correspond as well to tooth pain proprioception by dentinal tubules but should play a chief role to accentuate higher modulus differences at the cavity margins during interlaminar shearing and breaking of adhesive bonds with lower modulus materials. Consequently, FRC quartz fibers with modulus of 72 GPa [7] are considered to have potential in limiting adhesive shear deflections when bonded well to tooth margins and filling walls and also act as barriers to moisture [41]. Crack deflections by fibers out of the bond plane can be designed along with placement pressure and reduced polymerization shrinkage stresses to increase adhesive bonding [2, 49-51]. With the increased cohesive strength [1-6] and presumably crack deflections out of the bond plane [2], preliminary tests for 9.0 μm diameter 1.0 mm long quartz fibers increased adhesive shear bond strength. Further, advanced new nanofibers have shown 145% improvements in adhesive shear strength that could be even greater by devising mechanical retention locks.

Additional Problems with PFCs

Extra compounding problems that should be considered other than much lower PFC moduli that favor amalgam longevity with regard to failure by secondary caries at the margin can include many more variables. Increased bacterial adhesion and microbial build-up due to a lack of dental PFC antimicrobial properties [15, 16, 19, 20, 22, 28, 29] do not protect filling margins in a similar manner by well-known and historical silver antimicrobial properties [63-72]. Higher marginal ditching that would collect bacterial plaque from wear of PFCs is compared to lower amalgam wear rates [73]. Microleakage of PFCs from hydrophilic or acidic adhesives without conventional rinses and loss of strength after moisture exposure by hydrophilic polymer diluents is another concern [74-77]. PFC polymerization volumetric shrinkage with internal stresses at the margins can open up an adhesive bond particularly after loading to start microleakage [78]. In addition, moisture polymer degradation within PFCs could reduce most mechanical properties [42, 43, 55-57] to increase each form of material failure such as microcracking, marginal chipping, marginal adhesive debonding, bulk fracture and wear.

Antimicrobial Properties

PFCs have been shown to develop 3.2 times more plaque than amalgam on class II margins [15]. Leachable monomers of dental PFCs [79, 80] have been found capable of supporting bacterial growth [79, 81]. Further, dental PFCs have been seen to promote decay under restorations not seen under amalgams with service following ideal identical conditions [79]. An important well-known advantage for amalgam is silver antimicrobial properties [63-72]. Fortunately, due to high viscosity FRCs have been shown to be a model material to incorporate triclosan antimicrobial since lower viscosity PFCs lose all consistency and turn into a gluey state when triclosan is added [82-84]. Further, the broad-spectrum antimicrobial triclosan acts both as a hydrophobic wetting agent to reduce viscosity during the mixing stage for resin and fiber incorporation in addition to a toughening agent by bond entanglements that toughens the cured polymer with greater flexural and adhesive bond strength [82-84]. The odd alarmist triclosan controversy over bacterial resistance has been unjustifiable without any bacterial resistance reported in over 40 years resulting in recommendations for triclosan use wherever a health benefit is possible [83, 84].

Wear and Roughness

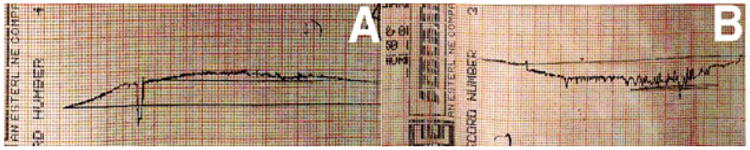

In vivo and in vitro tests have demonstrated that amalgam wears much less than dental PFCs [73]. Original PFC wear problems were significantly corrected by using nanoparticulate that did not debond during wear and further sheltered larger particulate in microhybrid materials [37, 85]. However, although PFCs as 100% nanoparticulate wear better such composites are weak and fail more frequently by marginal fracture compared to common hybrid dental PFCs with higher mechanical properties [74, 85]. Also, nanoparticulate PFCs still produce a marginal ditch step observed clinically by scanning electron micrographs (SEMs) after three years service [85]. On the other hand, newer photocure FRCs with fibers above Lc greatly significantly statistically improve mechanical properties over dental PFCs or PFC with microfibers and have been shown in preliminary 3-body wear tests at 400,000 cycles after 92 hours to wear even better than enamel [86]. Using the University of Alabama at Birmingham wear test method generalized wear was examined with a flat polyacetal stylus and polymethylmethacrylate bead slurry that has correlated closely after 92 hours with clinical wear testing of three years that further demonstrates similar PFC marginal ditching steps at the filling-enamel interface [73]. Such marginal ditching trenches that lie below the enamel margin are a subsequent concern regarding bacterial collection on the occlusal tooth surface. Wear tracings were completed by profilometer of the wear surfaces for an FRC with fibers above Lc and the Alert® PFC with microfibers that were well below Lc better described by particulate [86], Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Profilometer wear tracings. (A) FRC with fibers above Lc with less wear than enamel (B) PFC Alert® with microfibers below Lc show margins ditched with greater wear than enamel.

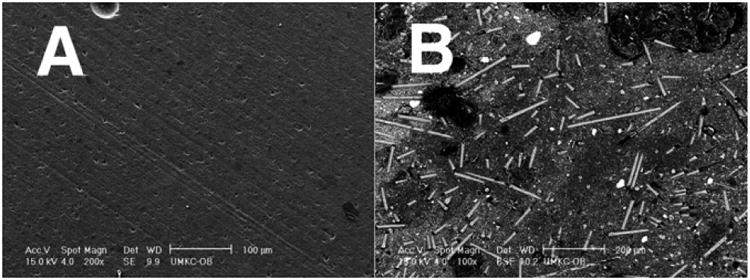

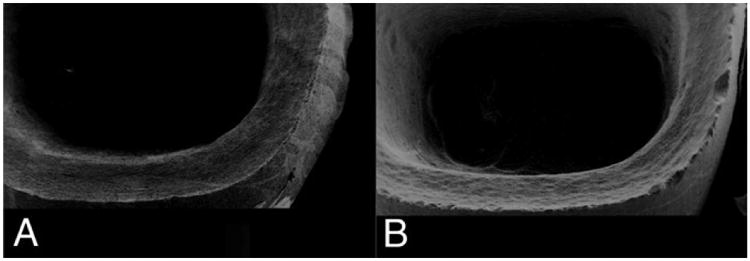

SEMs of the same wear sample surfaces show the discontinuous chopped FRC molding compound with fibers greater than Lc to be vastly smoother and polished even at twice the magnification when compared to the rough surface for the PFC Alert ® with short microfibers below Lc [86], Figure 2.

Figure 2.

SEMs (A) FRC polished smoothly with extremely low wear surface 200× magnification scale bar 100μm (B) Rough PFC Alert microfiber wear surface 100× magnification scale bar 200μm.

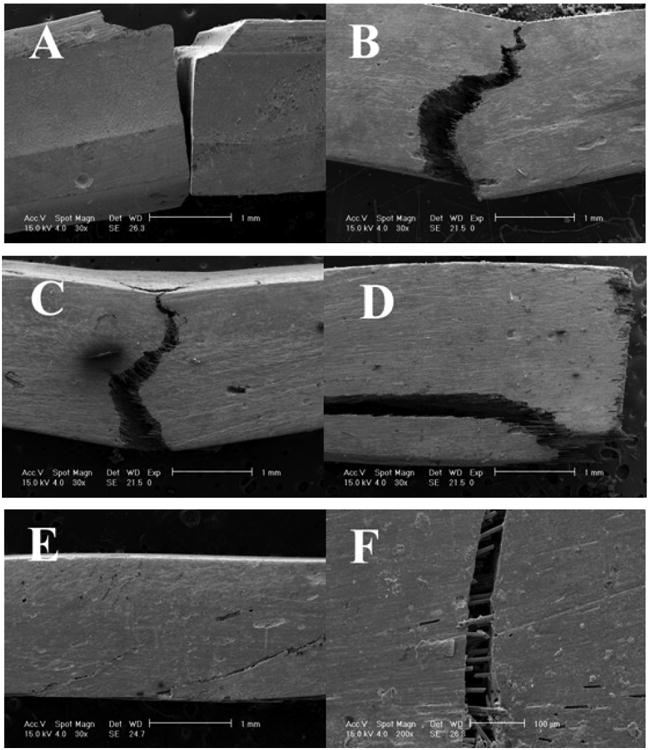

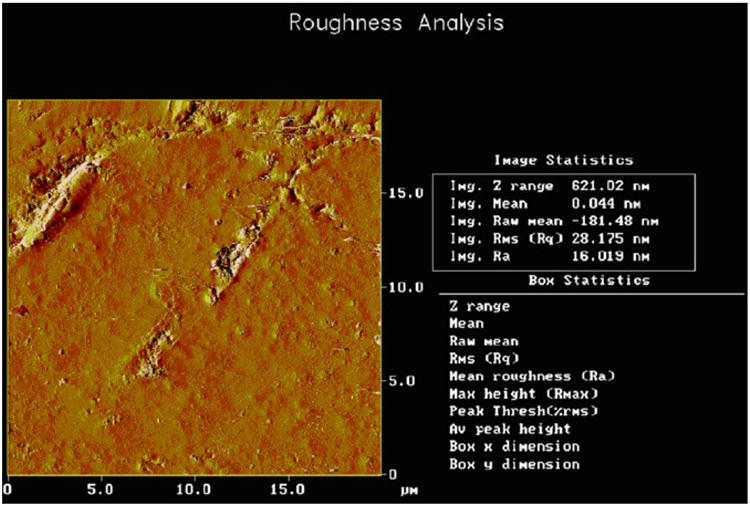

Because of the extremely smooth wear surface created by the FRC with fibers above Lc, the possible misconception that FRCs might be rough compared to the dental PFCs with much smaller filler sizes needs explaining. Most importantly, from a practical clinical standpoint FRCs with fibers above about 2× Lc pack parallel to adhesive surfaces or to the occlusal plane and wear into a smooth surface as overlying particulate solidly supported in the polymer matrix by underlying high-strength fibers are firmly contained without forming microcracks [86]. Conversely, dental PFCs and dental PFCs with microfiber wear into rough surfaces [73, 86] due to poorer mechanical properties that allow polymer matrix microcracking and increased moisture adsorption [41, 42]. Further, PFCs wear with marginal fracturing by small nanoparticulate [85], shearing of larger particulate into the polymer matrix for debonding and hydrolysis of polymer matrix that holds all filler in place [37, 85]. Also, dental PFCs and the Alert® PFC with microfiber wear faster than enamel to produce detrimental marginal ditching trenches [73, 85, 86] that should collect bacteria at the susceptible adhesive marginal bond to support recurrent caries. On the contrary, FRCs with fibers above Lc wear less than enamel, Figure 1, and consequently do not produce damaging rough marginal ditching spots [86]. The Z100® dental PFC mechanical test samples, Table 1, always fracture completely through whereas the FRCs with fibers only at Lc in the Z100® matrix rarely fracture through the entire test samples completely, Figure 3. In fact, the FRC samples with fibers at least 1.0 mm still maintain some fiber bridging at PFC critical load. When fibers extend at least 2× Lc FRCs fracture at much higher loads than the dental PFC for all mechanical properties and statistically significantly for flexural strength, modulus, yield strength and KIc (p<0.05). As fibers lengthen the cracks hold together better with larger reductions in crack dimensions that become scarcely visible fiber observations by SEMs [2, 4]. FRC bulk molding compounds formed as rolls of fiber in a thickened resin matrix are accepted industrially to make small components where the resin is forced under pressure away from the internal bulk with fibers to cover the containing mold walls producing parts after curing with extremely fine surfaces smoother than PFC. As an example from dental FRC atomic force microscopy (AFM) characterization, a bent fiber partially broken from a forceful mixing process adapts to the mold surface and further allows PFC matrix to squeeze around the fiber completely to eventually produce a cured surface with surface roughness (Ra) of just 16 nanometers, Figure 4. Further, FRCs machine much smoother than ceramic dental material intended for computer aided design/computer aided manufacturing (CAD/CAM) crowns [87], Figure 5.

Figure 3.

SEMs Table 1 mechanical test fracture samples (A) PFC 3M Z100® always at complete fracture through test sample 30×. (B) PFC 3M Z100® with 30 wt% 0.5 mm fibers 30×. (C) PFC 3M Z100® with 30 wt% 1.0 mm fibers 30×. (D) PFC 3M Z100® with 30 wt% 2.0 mm fibers 30×. (E) PFC 3M Z100® with 30 wt% 3.0 mm fibers 30×. (F) FRC showing fibers internal to a crack with fiber fracture in addition to fiber bridging of the crack and fiber pullout that help hold the crack together to reduce crack width and crack propagation, scale bar 100 μm 200×.

Figure 4.

AFM for unpolished surface of FRC with PFC matrix consolidated completely all around a broken fiber. Ra is still only 16 nm for the roughest area on the entire sample surface.

Figure 5.

SEMs of CAD/CAM crowns and margins (A) FRC with smooth margins (B) Procad® ceramic with rough margins showing machining striations and edge chipping.

Technique Sensitive Concerns for PFCs

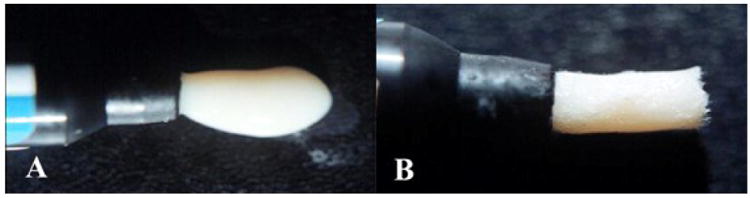

Regarding clinical filling placement, dental PFCs are considered technique sensitive in posterior teeth [59, 88] that appears to be a chief cause of failure during the first five years, but secondary caries becomes the main failure after five years [89]. The amalgam filling is considered to be much easier to use than the dental PFC [90-96]. Dental PFCs have been estimated to take twice as long to complete as a comparable amalgam [91]. The dental PFC exists in a tacky paste state between a lightly flowable and a barely condensable material while current dental resins are characterized by an inherent sticky adhesion to packing instruments that can interfere with their placement in dental restorations creating perceptible voids [97]. Technique sensitive problems of concern commonly expressed when placing dental PFCs due to the low viscosity consistency include the occurrence of voids in the class II proximal box [40, 98-102] and poor reestablishment of the interproximal contact [90, 92, 94-96, 98, 103-114]. Also, class II PFC overhangs are a difficult problem to detect due to low radiopacity of thin excess polymerized hard material and bonding resin extending beyond the gingival margin [6, 90, 115]. In fact, plaque accumulated 3.2× more frequently for PFC than amalgams on class II margins [15] and recurrent caries occurred 5.4× more often with PFCs than amalgams at the gingival margin [24]. On the other hand, FRCs increase viscosity consistency substantially over PFCs and can consolidate under pressure with resin, monomers and particulate squeezed from the bulk when packed into a cavity to eliminate the larger macroscopic voids seen on PFC x-rays [6, 51]. In related development FRC consolidation pressure is expected to help infiltrate hydrophobic resin adhesive bond systems and strengthening nanofibers into tooth mechanical retention areas. Further, fibers longer than Lc increase cohesive strength [2, 6] while in preliminary tests 1.0 mm 9.0 µm diameter fibers appear to deflect cracks away from the bond plane for increased adhesive strength. In addition, fibers at least 2× Lc pack parallel to the bond and occlusal planes to wear extremely smooth [51]. Comparisons for clinical handling are shown by materials in tubes forced out as low-viscosity sticky PFC or thickened consistency easy-to-pack FRC, Figure 6.

Figure 6.

(A) low viscosity sticky dental PFC paste (B) thickened consistency with FRC molding compound.

Voids

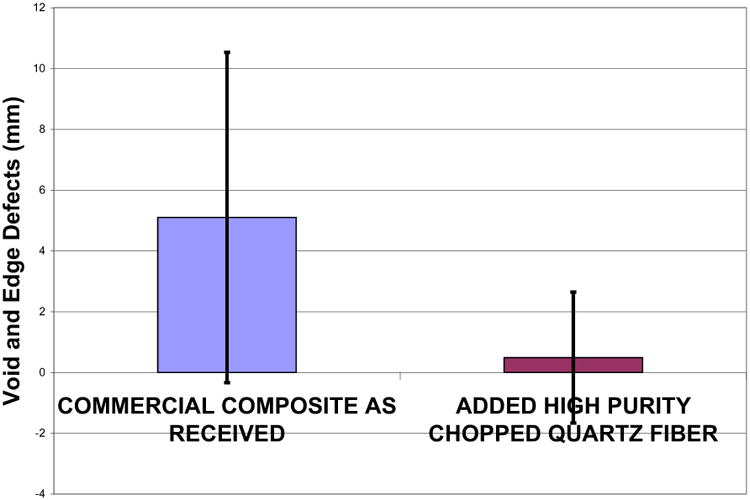

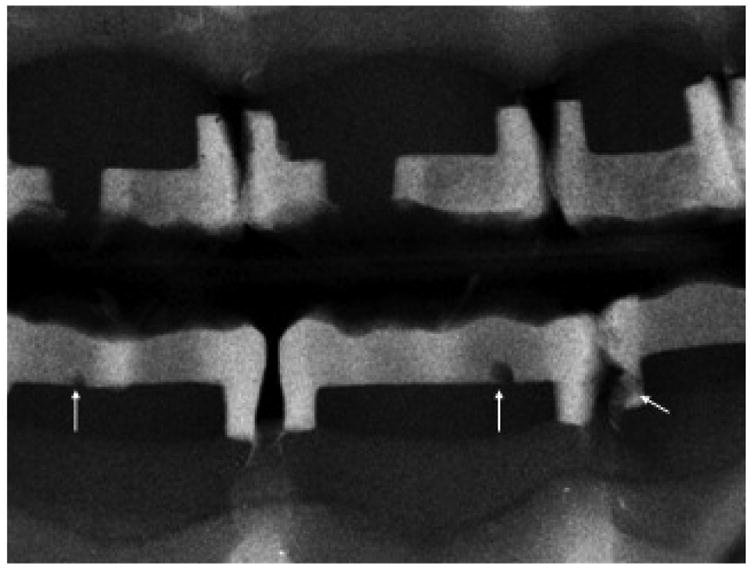

Problems with voids were of such concern the American Dental Association Council of Dental Materials recommended in 1980 that standards be made for x-ray radiopacity in class II restorations in order to identify “major voids” [99]. Voids in composites are generally overlooked until an x-ray is taken at a later time. Increased leakage at the class II gingival margin due to a void increases bacterial leakage with pain often mentioned by the patient [40]. Further, class II restorations have produced failures by dental students at a rate 10× greater for dental PFC composites than amalgams with voids charted as one of the main problems [100]. PFC voids usually combine in the hybrid layer of dentin as porosities at the gingival margins [101]. Also, voids reduced adhesive bond strength in class II PFC restorations [102]. In terms of moisture lowering polymer matrix mechanical properties, if enough voids occur mechanical properties of the polymer matrix can be reduced even more [55]. For experimental testing in regard to quantifying reduced void defects, 3M Corp Z100® PFC and DenMat Marathon® PFC were compared to FRCs as chopped fibers incorporated into Z100® or DenMat® and packed at 1-2 mm in depth into a 6 mm diameter circular well used for a related polymerization shrinkage tests [51]. Group I consisted of 45 PFC commercial composite samples and Group II included 31 samples of the same commercial pastes but incorporated by hand mixing with average 9.2 wt% 9.0 μm diameter 3 mm chopped fibers. In the bench-top laboratory study observable surface voids were measured for combined diameters in each photocured sample. Results showed that FRCs greatly and significantly statistically reduced the average combined sample void sizes compared to similar PFCs (p<0.00001) [51], Figure 7. Further, consolidation with pressure using FRCs eliminates voids in the proximal box observed radiographically in non-clinical typodont tests compared to sticky low viscosity PFCs that are difficult to pack, Figure 8 of PFC voids. Inability to consolidate dental PFCs contributes to both larger void defects in the proximal box in addition to porosity that undermines the adhesive bond at the gingival margin [101, 102]. Consequently, radiographic results of 14,140 class II fillings that show caries was detected interproximally 5.4 times more frequently in PFCs than in amalgams [24] can be explained in part by PFC packing defects from voids and porosity that reduce bond strength and support bacterial growth due to gingival margin flaws as in Figure 8.

Figure 7.

Chart for average total void diameters in millimeters for a sample comparing commercial dental PFCs with the same PFCs but with 3.0 mm fibers added at an average of 9.2 wt% (p<0.00001).

Figure 8.

X-ray of typodont for class II PFCs top and bottom with voids identified by arrows on the lower arch.

Overhangs

Radiographic examination of 14,140 interproximal surfaces that gave results showing a 5.4× excess of interproximal recurrent caries at the gingival margin for dental PFCs compared to amalgam [24] can further be explained in part due to a polymeric material overhang [6]. The PFC overhang is the result of unmanageable low viscosity excess PFC material that runs between the matrix band and the gingival margin which is difficult to seal complete with a wedge. A wedge seal for a much higher consistency amalgam will not suffice for a PFC that has a tendency to flow even without any pressure resulting in the overhang below the gingival margin on a typodont tooth, Figure 9. By comparison a typodont is a far easier model to place a filling compared to management in a clinical setting. Further PFC overhangs are difficult to detect whereas amalgams are easy to identify radiographically and by thin explorer [90]. Following polymerization of the PFC, the overhang material is completely hardened and cannot easily be removed [6, 90]. Consequently, the overhang can collect bacteria as another source for recurrent caries. In a typodont study comparing different class II matrix techniques with 240 teeth in 12 groups, regardless of the most careful placement methods the complete deterrence of an overhang was considered almost without solution [115]. Conversely, the FRCs have greater consistency than an amalgam requiring even higher condensation forces for packing than an amalgam [51] and FRCs can also be incrementally photocured. As a result, the gingival class II margin can be initially positioned with a small layer of FRC carefully placed with wedge to seal the gap between the tooth and matrix band and cleaned with an explorer at the tooth gingival margin surface before photopolymerization cure. With the first light FRC layer cured by light positive pressure and the gingival margined sealed, using tight wedging properly subsequent higher packing forces can be applied during incremental filling of the cavity. In addition to the runny low viscosity PFC problem of producing a class II gingival overhang, radiolucent and much lower viscosity photocure bonding agent can pool and also be difficult to control by wedge sealing the matrix band at the gingival class II margin.

Figure 9.

Overhang of PFC that squeezed under the wedged matrix band before photocuring and photocured hard as rougher thin deposit defect.

Interproximal Contact and Packing Forces

Because of low viscosity and weak consistency dental PFCs cannot pack during material insertion with condensation forces of adequate magnitude similar to the amalgam that often prevent reestablishment of the interproximal contact in a class II filling [90, 92, 94-96, 98, 103-114]. Light or open contacts were found in 24% of a class II PFC investigation [18]. Conversely, with FRCs the interproximal contact can be inserted with greater pressure even than an amalgam for larger interproximal contact areas placed between teeth, Table 3. A laboratory typodont model using plastic teeth was established to measure the interproximal contact comparing 3M Corp. Z100® PFC, Z100® PFC with 9.2 wt% 3 mm length quartz fibers and Kerr Tytin® Firm Condensation (FC) amalgam [51]. Peak condensation forces were recorded during each incremental filling placement from a condensing instrument attached to an Omega force gauge, calibrated through National Institute of Technology traceable standards. Condensation and packing were completed only through the three restorative materials being tested without penetrating down onto the hard typodont tooth plastic. Embrasure margins were evened flush, but ideal contours were sacrificed, maximizing each interproximal contact area to best equalize testing of every contact measurement for the different filling materials. The assumption that extra material or larger over-contoured contact areas will be easier in a clinical situation to finish back into perfect conformation are preferred rather than risk the undesirable formation of questionable under-contoured contact areas that may need to be replaced.

Table 3. Interproximal Contact Measurements (N=12).

| Sample Groups | Interproximal Contact (mm)* | Condensation Force (Newtons) |

|---|---|---|

| Uncut tooth | 11.3 (±0.8) | NA |

| 3M Z100® | 11.2 (±1.3) | 10.36 (±3.25) |

| Z100®+9.2wt% Quartz | 14.6 (±1.0) | 32.92 (±5.38) |

| Tytin® FC Alloy | 11.7 (±1.0) | 24.29 (±4.14) |

Combined averages for both mesial and distal contact circumferences

Interproximal contact measurement was accomplished by first placing dental floss through the contact at the occlusal marginal ridges. The floss was subsequently wrapped around the interproximal contact circumference area securely and marked with a pen at the point where the floss cord crosses at the occlusal marginal ridge, Figure 10. After the floss was extended and withdrawn under the contact, the floss was drawn straight where the two ink marks were then measured at their center points using an electronic micrometer. The addition of 3 mm length quartz fiber at a 9.2 wt% average to the Z100® PFC could statistically significantly achieve larger interproximal contact circumferences than the 3M Corp. Z100® PFC and also superior contact circumferences than the high viscosity Tytin® FC amalgam (p<0.0001). Further, the addition of 3 mm length quartz fiber at a 9.2 wt% average to the Z100® PFC could statistically achieve higher condensation forces than the 3M Corp. Z100® PFC and also superior condensation forces than the high viscosity Tytin® FC amalgam (p<0.001). Also, Tytin® FC significantly statistically increased the interproximal contact circumferences over the 3M Corp Z100® (p<0.01) and condensation forces (p<0.001). Further, from Table I the addition of 28.2 vol% or 30 wt% 3 mm length fiber into a similar 3M Corp. Z100® PFC could easily be achieved that should provide much higher condensation forces than the FRCs at 9.2wt%.

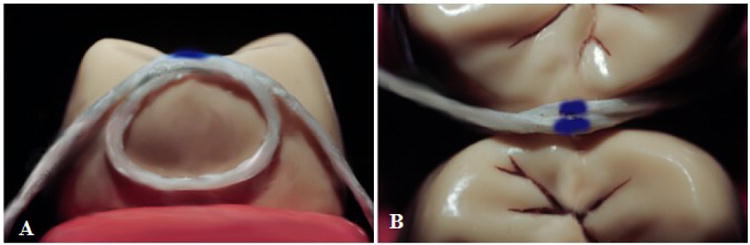

Figure 10.

Interproximal contact measurement (A) Interproximal side view (B) Occlusal top view

The interproximal contact is considered to be a primary objective for all dental restorations [113, 116-119]. When defining the interproximal contact, a contact area should be present that is not satisfied by a point [120, 121]. The interproximal contact should be sufficiently tight so that considerable tension is required to pass dental floss through between adjacent teeth [120]. If an interproximal contact is too loose and not sufficiently tight with proper contact strength, food wedging and foodstuff impaction can occur [121-124]. If the interproximal contact is adequately tight enough to oppose separation during mastication food impaction will not occur [120, 122]. Weak interproximal contacts are also correlated with increased risk for caries [121]. Food impaction from open interproximal contacts often creates pain [121, 124], especially when fibers from food are wedged interproximally that are a concern [124]. Food impaction is most often experienced with open contacts that cause pocket depths to be greatest when compared to tight contacts [122, 124] and also increases attachment loss [124]. Further, food impaction from open contacts can result in tooth mobility [121, 122, 124]. Consequently, open contacts might need to be closed to alleviate food impaction [123] and other problems such as pain and tooth mobility and possible recurrent caries.

In associated work progress, extremely high FRC adhesively applied packing forces with much higher resistance from the underlying hard tooth bonding surface might be limited only by clinical skill so that hydrophobic resin systems, nanoparticulate and nanofibers can be squeezed by operator pressure into mechanical adhesive retention sites from the core fibers. Fibers at 9 um diameters with 2.0 mm lengths and greater planarize flat onto tooth surfaces [1, 6, 51, 125]. However, fibers 1.0 mm and lower or nanofibers appear to align somewhat out of plane to divert crack deflections away from the bond plane and increase adhesive strength during interlaminar shear bond testing. Increased fiber lengths significantly and at great measure increase all mechanical properties that include fracture toughness at all levels, Table 1 [6]. Consequently, high packing forces will be examined to align and extrude increased nanofiber lengths into dentinal tubules for increased adhesive interlaminar shear bond strength. Also, along the cavity margins monomer, resin and particulate are squeezed away from the FRC at the surface to seal the bond as a high concentration of insoluble high-strength pure quartz fibers and nanofibers with particulate [1, 6]. The high concentration of insoluble fibers and particulate at the cavity margin is then expected to attain a permanent seal as a thin FRC adhesive bond moisture barrier [41, 126]. Once the margins are sealed with insoluble fibers, the cavity can subsequently be incrementally cured with FRC molding compound to complete the filling. As previously mentioned, high FRC viscosity provides abilities to incorporate triclosan antimicrobial that can destroy all PFC consistency into a sticky gluey state so that packing become impossible [82-84]. Further, higher FRC viscosity with increased packing pressure allows the addition of the relatively low-viscosity vinyl ester oligomer ethoxylated bis phenol A dimethacrylate (BisEMA) resin [127]. BisEMA increases the hydrophobicity with lower polarity of the molecular chain for improved moisture resistance [127, 128]. BisEMA low resin viscosity of 860 cps subsequently requires addition of a cure-type crosslinker monomer triethylene glycol dimethacrylate (TEGDMA) with viscosity of just 8 cps [127], Table 4. The common Z100 3M Corporation PFC uses a resin:monomer-crosslinker 50:50 mixture of dimethacrylate vinyl ester oligomer 2,2-bis [p-(2′hydroxy-3′-methacryloxypropoxy phenyl)] propane (BisGMA) with viscosity of 700,00 cps and TEGDMA for a combined viscosity of 180 cps [127]. BisGMA is similar to BisEMA but with polar hydroxyl groups that increase viscosity and reduce moisture resistance [127, 128]. However, the viscosity of a 50:50 mixture of BisEMA and TEGDMA crosslinker is too low at 57.5 cps for a dental PFC [127] requiring additive thickeners that are supplied most effectively with FRC fibers above Lc. In terms of moisture resistance, hydrophobic BisEMA resin is significantly statistically lower in terms of water sorption than BisGMA and lower in solubility than both BisGMA and TEGDMA [128].

Table 4. Viscosity for Different Vinyl Ester Resin Systems.

| Resin or Monomer or Mixtures | Concentration(s) | Viscosity (cps) |

|---|---|---|

| BisGMA Resin* | 100% | 700,000 |

| BisEMA Resinλ | 100% | 860 |

| TEGDMA Monomer* | 100% | 8 |

| BisGMA:TEGDMA* | 80:20 | 7000 |

| BisGMA:TEGDMA* | 50:50 | 180 |

| BisEMA:TEGDMAλ | 85:15 | 465 |

| BisEMA:TEGDMAλ | 75:25 | 226.5 |

| BisEMA:TEGDMAλ | 50:50 | 57.5 |

Esstech Corporation at 25°C;

Peter M Walsh UAB at 20°C; Viscosities are generally measured between 20°C and 25°C probably due to the water reference of 1.0 cps at 21°C.

Summary and Conclusion

FRCs above Lc can provide vastly statistically significant improvements over PFCs in all mechanical properties for flexural strength, yield strength, modulus, resilience, WOF, SIc, KIc and Izod impact toughness. Further, FRC molding compounds with fibers above Lc extensively improve all mechanical properties tested for comparison over the amalgam except modulus. In addition, the PFC showed increases for all mechanical properties over the amalgam except modulus. Consequently, modulus is a mechanical property that can help explain increased failure of PFCs compared to amalgam where secondary caries is the chief failure mechanism for both materials. Lower PFC modulus would result in increased adhesive bond failure due to greater interlaminar shearing with the high modulus tooth enamel filling margins compared to higher modulus amalgam. Preliminary wear testing for FRCs with fibers above Lc resulted in the normal three-body wear less than enamel to diminish the likelihood of forming marginal trenches that could collect bacteria as an issue in secondary caries seen with both PFCs and amalgam. Further, FRCs with fibers above Lc can pack with forces higher than the amalgam to prevent the formation of voids in the proximal box that often occur with PFCs and also reestablish interproximal contacts better than PFCs or amalgam. Because the FRC has the ability to pack with significant high pressure future work will examine pressure infiltration by monomer, resin and nanofibers into dentin for improved mechanical retention expected to help increase adhesive bonding strengths. Consequently, the hydrophilic monomers or possible acid necessary for hydrophilic capillary infiltration could be eliminated entirely. Pressure application will also study sealing cavity margins with a concentration of high strength insoluble fibers where monomer, resin and particulate are expressed from the mass. In addition, FRCs can easily incorporate the hydrophobic triclosan antimicrobial and pack strong without gluey loss of consistency that occurs with PFCs. Also, FRCs can aid in adding hydrophobic low-viscosity BisEMA resin to replace extremely high viscosity BisGMA resin to improve moisture resistance. Consequently, by numerous improved exceptional designing-related properties FRCs with fibers above Lc provide an opportunity to replace PFCs and amalgam alloys for many dental restorations.

Acknowledgments

Support in part from funding through the National Institutes of Health grant numbers T32DE07042 and T32DE014300. Discontinuous Lc FRC SEMs Dr. Vladimir M. Dusevich Director Electron Microscopy Laboratory, University of Missouri-Kansas City. CAD/CAM Crowns Dr. Perng-Ru Liu Chair Restorative Sciences, School of Dentistry, University of Alabama at Birmingham. CAD/CAM SEMS Preston Beck, Biomaterials, School of Dentistry, University of Alabama at Birmingham. AFMs from the laboratory of Dr. Yip-Wah Chung, Director of Materials Science, School of Engineering, Northwestern University. Viscosity Measurements Dr. Peter M. Walsh, Mechanical Engineering, University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: No conflicts declared.

References

- 1.Petersen RC. Discontinuous fiber-reinforced composites above critical length. Journal of Dental Research. 2003;84:365–370. doi: 10.1177/154405910508400414. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3989201/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petersen RC, Lemons JE, McCracken MS. Fiber length micromechanics for fiber-reinforced composites with a photocure vinyl ester resin. Polymer Composites. 2006;27:153–169. doi: 10.1002/pc.20198. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4221241/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petersen RC, Lemons JE, McCracken MS. Micromechanics for fiber volume percent with a photocure vinyl ester composite. Polymer Composites. 2007;28:294–310. doi: 10.1002/pc.20241. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4221239/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petersen RC, Lemons JE, McCracken MS. Fracture toughness micromechanics by energy methods with a photocure fiber-reinforced composites. Polymer Composites. 2007;28:311–324. doi: 10.1002/pc.20242. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4206059/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petersen RC. SAMPE 2013. Symposium; Long Beach, CA: May 7, 2013. Accurate critical stress intensity factor Griffith crack theory measurements by numerical techniques, Society for Advanced Materials and Process Engineering; pp. 737–752. 2013. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4302413/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petersen RC, Liu PR. Mechanical properties comparing composite fiber length to amalgam. Journal of Composites. 2016;2016:13. doi: 10.1155/2016/3823952. Article ID 3823952. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2016/3823952 and https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5023074/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peters ST. Handbook of Composites. Chapman and Hall; London: 1998. pp. 162pp. 1047–1048. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Callister WD. Materials Science and Engineering. 4th. John Wiley & Sons; New York, NY, USA: 1997. p. 526. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Council on Scientific Affairs. Direct and indirect restorative materials. Journal of the American Dental Association. 2003;134:463–472. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2003.0196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spencer P, Qiang Y, Park J, Topp EM, Misra A, Marangos O, Wang Y, Bohaty BS, Singh V, Sene F, Eslick J, Camarda K, Katz JL. Adhesive/dentin interface: The weak link in the composite restoration. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 2010;38(6):1989–2003. doi: 10.1007/s10439-010-9969-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skjörland K. Plaque accumulation on different dental filling materials. Scandinavian Journal of Dental Research. 1973;81:538–542. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1973.tb00362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skjörland K. Bacterial accumulation on silicate and composite materials. Journal de Biologie Buccale. 1976;4:315–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ornstein D, Petersen A. Bacterial activity of tooth-colored dental restorative materials. Journal of Dental Research. 1978;57:141–174. doi: 10.1177/00220345780570020101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scotland K, Sonja T. Effect of sucrose rinses on bacterial colonization on amalgam and composite. Act Odontologia Scandinavia. 1982;40:193–196. doi: 10.3109/00016358209019811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Svanberg M, Mjör IA, Ørstavik D. Mutans streptococci in plaque from margins of amalgam, composite and glass-ionomer restorations. Journal of Dental Research. 1990;69(3):861–4. doi: 10.1177/00220345900690030601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matasa CG. Microbial attack of orthodontic adhesives. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics. 1995;108(2):132–141. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(95)70075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hansel C, Leyhausen G, Mai UE, Geurtsen W. Effects of various resin composite (co)monomers and extracts on two caries associated micro-organisms in vitro. Journal of Dental Research. 1998;77:60–67. doi: 10.1177/00220345980770010601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Collins CJ, Bryant RW, Hodgel KL. A clinical evaluation of posterior composite resin restorations: 8-year findings. Journal of Dentistry. 1998;26:311–317. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(97)00019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karanika-Kouma A, Dionysopoulos P, Koliniotou-Koubia E, Kolokotronis A. Antibacterial properties of dentin bonding systems, polyacid-modified composite resins and composite resins. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation. 2001;28:157–160. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2842.2001.00643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boeckh C, Schumacher E, Podbielski A, Haller B. Antibacterial activity of restorative Dental Biomaterials in vitro. Caries Research. 2002;36:101–107. doi: 10.1159/000057867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mjör IA, Cahl JE, Moorhead JE. Placement and replacement of restorations in primary teeth. Acta Odontologica Scandinavica. 2002;60(1):25–28. doi: 10.1080/000163502753471961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Imazato S. Antibacterial properties of resin composites and dentin bonding systems. Dental Materials. 2003;19:449–457. doi: 10.1016/s0109-5641(02)00102-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nieuwenhuysen JP, D'Hoore W, Carvalho J, Qvist V. Long-term evaluation of extensive restorations in permanent teeth. Journal of Dentistry. 2003;31:395–405. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(03)00084-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levin L, Coval M, Geiger S. Cross-sectional radiographic survey of amalgam and resin-based composite posterior restorations. Quintessence International. 2007;38:511–514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soncini JA, Maserejian NN, Trachtenberg F, Tavares M, Hayes C. The longevity of amalgam versus compomer/composite restorations in posterior primary and permanent teeth Findings from the New England Children's Amalgam Trial. Journal of the American Dental Association. 2007;138(6):763–772. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2007.0264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bernardo M, Luis H, Martin MD, Leroux BG, Rue T, Leitão J, DeRouen TA. Survival and reasons for failure of amalgam versus composite posterior restorations placed in a randomized clinical trial. Journal of the American Dental Association. 2007;138(6):775–783. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2007.0265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gama-Teixeira A, Simionato MR, Elian SN, Sobral MAP, de Luz MAA. Streptococcus mutans-induced secondary caries adjacent to glass ionomer cement, composite resin and amalgam restorations in vitro. Brazilian Oral Research. 2007;21(4):368–64. doi: 10.1590/s1806-83242007000400015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beyth N, Domb AJ, Weiss EI. An in vitro quantitative antibacterial analysis of amalgam and composite resins. Journal of Dentistry. 2007;35:201–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spencer P, Ye Q, Misra A, Goncalves SEP, Laurence J. Proteins, pathogens, and failure at the composite-tooth interface. Journal of Dental Research. 2014;93(12):1243–1249. doi: 10.1177/0022034514550039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Antony K, Genser D, Hiebinger C, Widisch F. Longevity of dental amalgam in comparison to composite materials. GMS Health Technology Assessment. 2008;4(ISSN):1861–8863. Open Access. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kovarik RE. Restoration of posterior teeth in clinical practice: Evidence base for choosing amalgam versus composite. Dental Clinics of North America. 2009;53:71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spencer P, Park J, Ye Q, Misra A, Bohaty BS, Singh V, Parthasarathy R, Sene F, Goncalves SE deP, Laurence J. Durable bonds at the adhesive dentin interface: an impossible mission or simply a moving target? Brazilian Dental Science. 2012;15(1):4–18. doi: 10.14295/bds.2012.v15i1.790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bohaty BS, Ye Q, Misra A, Sene F, Spencer P. Posterior composite restoration update: focus on factors influencing form and function. Clinical, Cosmetic and Investigational Dentistry. 2013;5:33–2. doi: 10.2147/CCIDE.S42044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rasines Alcaraz MG, Veitz-Keenan A, Sahrmann P, Schmidlin PR, Davis D, Iheozor-Ejiofor Z. John Wiley and Sons; 2014. Direct composite resin fillings versus amalgam fillings for permanent or adult posterior teeth (Review) The Cochran Collaboration, The Cochran Library Issue; p. 3. http://www.thecochranelibrary.com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rasines Alcaraz MG, Veitz-Keenan A, Sahrmann P, Schmidlin PR, Davis D, Iheozor-Ejiofor Z. Amalgam or composite fillings-which materials lasts longer? Evidence Based Dentistry (EBD) 2014;15(2):50–51. doi: 10.1038/sj.ebd.6401026. www.nature.com/ebd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anusavice KJ. Dental Materials. 11th. St. Louis: Elsevier Saunders; 2003. Chapter 15 Restorative Resins Composites for Posterior Restorations; pp. 428–432. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bayne SC, Taylor DF, Heymann HO. Protection hypothesis for composite wear. Dental Materials. 1992;8:305–309. doi: 10.1016/0109-5641(92)90105-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Council on Dental Materials, Instruments and Equipment. Choosing intracoronal restorative materials. Journal of the American Dental Association. 1994;125(1):102–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Council on Scientific Affairs. Statement on posterior resin based composites. Journal of the American Dental Association. 1998;129(11):1627–1628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bergenholtz G. Evidence for bacterial causation of adverse pulpal responses in resin-based dental restorations. Critical Reviews in Oral Biology and Medicine. 2000;11(4):467–480. doi: 10.1177/10454411000110040501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peters ST. Handbook of Composites. Chapman and Hall; London: 1998. pp. 630–631.pp. 797–801.pp. 1007–1012. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robinson P, Greenhalgh E, Pinho S. Failure Mechanisms in Polymer Matrix Composites. Oxford: WP Woodhead Publishing; 2012. pp. 395–401. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Söderholm KJM, Roberts MJ. Influence of water exposure on the tensile strength of composites. Journal of Dental Research. 1990;69(12):1812–1816. doi: 10.1177/00220345900690120501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cox HL. The elasticity and strength of paper and other fibrous materials. British Journal of Applied Physics. 1952;3:72–79. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kelly A, Tyson WR. Tensile properties of fibre-reinforced metals: copper/tungsten and copper/molybdenum. Journal of the Mechanics and Physics of Solids. 1965;13:329–350. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chawla KK. Micromechanics of composites, monotonic strength and fracture, and fatigue and creep In: Composite Materials. 2nd. New York: Springer; 1998. pp. 303–346.pp. 377–410. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bascom WD. Other discontinuous fibers. In: Dostal CA, Woods MS, Frissel HJ, Ronke AW, editors. Composites Engineered Materials Handbook. Metals Park, OH: ASM International; 1987. pp. 119–121. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mallick PK. Random fiber composites. In: Mallick PK, editor. Composites Engineering Handbook. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc; 1997. pp. 891–938. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wypych G, editor. Handbook of Fillers. 2nd. Toronto: Chem Tech Publishing; 1999. Effects of fillers on the mechanical properties of filled materials; pp. 395–457. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cloud PJ, Wolverton MA. Predict shrinkage & warpage of reinforced and filled thermoplastics. Plastics Technology. 1978;24(11):107–113. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Petersen RC. Micromechanics/Electron Interactions for Advanced Biomedical Research. Saarbrücken, Germany: LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing Gmbh & Co. KG; 2011. Chapter 23 Fiber-reinforced composite molding compound for dental fillings; pp. 395–415. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Giltrow JP. Friction and wear of self-lubricating composite materials. Composites (March) 1973:55–64. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Friedrich K, editor. Wear models for multiphase materials and synergistic effects in polymeric hybrid composites In: Advances in Composite Technology. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1993. pp. 209–269. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Anusavice KJ. Dental Materials. 11th. St. Louis: Elsevier Saunders; 2003. pp. 742–743. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Peters ST. Handbook of Composites London. Chapman and Hall; 1998. pp. 811–813. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chawla KK. Composite Materials. 2nd. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1998. pp. 153–155.pp. 256–257. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yiu CKY, King NM, Pashley DH, Suh BI, Carvalho RM, Carrilho MRO, Tay FR. Effect of resin hydrophilicity and water storage on resin strength. Biomaterials. 2004;25:5789–5796. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Makhija SK, Gordan VV, Gilbert GH, Litaker MS, Rindal DB, Pihlstrom DJ, Qvist V. Practitioner, patient and carious lesion characteristics associated with type of restorative material: Findings from the Dental Practice-Based Research Network. Journal of the American Dental Association. 2011;142(6):622–632. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2011.0244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ferracane JL. Current trends in dental composites. Critical Reviews in Oral Biology and Medicine. 1995;6(4):302–318. doi: 10.1177/10454411950060040301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sano H, Ciucchi B, Matthews WG, Pashley DH. Tensile properties of mineralized and demineralized human and bovine dentin. Journal of Dental Research. 1994;73:1205–1211. doi: 10.1177/00220345940730061201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Parks JB, Lakes RS. Biomaterials. 2nd. New York: Plenum Press; 1992. p. 196. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yin L, Song XF, Song TH, Li J. An overview of an in vitro abrasive finishing & CAD/CAM of bioceramics in restorative dentistry. International Journal of Machine Tools and Manufacture. 2006;46:1013–1026. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Silver S. Bacterial silver resistance: molecular biology and uses and misuses of silver compounds. FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 2003;27:341–353. doi: 10.1016/S0168-6445(03)00047-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Edwards-Jones V. The benefits of silver in hygiene, personal care and healthcare. Letters in Applied Microbiology. 2009;49:147–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2009.02648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lara HH, Garza-Treviño EN, Ixtepan-Turrent L, Singh DK. Silver nanoparticles are broad-spectrum bactericidal and virucidal compounds. Journal of Nanobiotechnology. 2011;9:30. doi: 10.1186/1477-3155-9-30. http://www.jnanobiotechnology.com/content/9/1/30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Miyayama T, Arai Y, Hirano S. Environmental exposure to silver and its health effects. Japanese Journal of Hygeine. 2012;67:383–389. doi: 10.1265/jjh.67.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cavaliere E, De Cesari S, Landini G, Riccobono E, Pallecchi L, Rossolini GM, Gavioli L. Highly bactericidal Ag nanoparticle films obtained by cluster beam deposition. Nanomedicine, Nanotechnology, Biology and Medicine. 2015;11:1417–1423. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2015.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Palza H. Antimicrobial polymers with metal nanoparticles. International Journal of Molecular Science. 2015;16:2099–2116. doi: 10.3390/ijms16012099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chatas R, Wojcik-Checińska I, Woźniak M, Grzonka J, Świeszkowski W, Kurzydtowski KJ. Dental plaque as a biofilm-a risk in oral cavity and methods to prevent. Postepy Higieny I Medycyny Doświadczainej (Online) 2015;69:1140–1148. doi: 10.5604/17322693.1173925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Corrêa JM, Mori M, Sanches HL, Dibo da Cruz A, Poiate E, Jr, Poiate IAVP. Silver nanoparticles in dental biomaterials. International Journal of Biomaterials. 2015;2015:9. doi: 10.1155/2015/485275. Article ID 485275. http://doi.org/10.1155/2015/485275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Franci G, Falanga A, Galdiero S, Palomba L, Rai M, Morelli G, Galdiero M. Silver nanoparticles as potential antibacterial agents. Molecules. 2015;20:8856–8874. doi: 10.3390/molecules20058856. www.mdpi.com/journal/molecules. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rudramurthy GR, Swamy MK, Sinniah UR, Ghasemzadeh Nanoparticles: Alternatives against drug-resistant pathogenic microbes. Molecules. 2016;21:836. doi: 10.3390/molecules21070836. www.mdpi.com/journal/molecules. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lenifelder KF, Suzuki S. In vitro wear device for determining posterior composite wear. Journal of the American Dental Association. 1999;130(9):1347–1353. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1999.0406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Anusavice KJ. Science of Dental Materials. 11th. St. Louis: Saunders; 2003. Bonding; pp. 381–398. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yiu CKY, King NM, Pashley DH, Suh BI, Carvalho RM, Carrilho MRO, Tay FR. Effect of resin hydrophilicity and water storage on resin strength. Biomaterials. 2004;25:5789–5796. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pashley DH, Tay FR, Breschi L, Tjaderhane L, Carvalho RM, Carrilho M, Tezvergil-Mutluay A. State of the art etch-and-rinse adhesives. Dental Materials. 2011;27:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2010.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Brackett MG, Li N, Brackett WW, Sword RJ, Qi YP, Niu LN, Pucci CR, Dib A, Pashley DH. The critical barrier to progress in dentine bonding with the etch-and-rinse technique. Journal of Dentistry. 2011;39:238–248. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2010.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Davidson CL, Feilzer AJ. Polymerization shrinkage and polymerization shrinkage stress in polymer-based restoratives. Journal of Dentistry. 1997;25(6):435–440. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(96)00063-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Geurtsen W. Biocompatibility of resin-modified filling materials. Critical Reviews in Oral Biology and Medicine. 1998;11(3):333–355. doi: 10.1177/10454411000110030401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Spahl W, Budzikiewicz H, Geurtensen W. Determination of leachable components from four commercial dental composites by gas and liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry. Journal of Dentistry. 1998;26(2):137–145. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(96)00086-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hansel C, Leyhausen G, Mai UEH, Geurtsen W. Effects of various resin composite (co)monomers and extracts on two caries-associated micro-organisms in vitro. Journal of Dental Research. 1998;77(1):60–67. doi: 10.1177/00220345980770010601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Petersen RC. Computational conformational antimicrobial analysis developing mechanomolecular theory for polymer Biomaterials in Materials Science and Engineering. International Journal of Computational Materials Science and Engineering. 2014;3(1):48. doi: 10.1142/S2047684114500031. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4295723/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Petersen RC. Triclosan computational conformational chemistry analysis for antimicrobial properties in polymers. Journal of Nature and Science. 2015;1(3):e54. 2015. http://www.jnsci.org/content/54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Petersen RC. Triclosan antimicrobial polymers. AIMS Molecular Science. 2016;3(1):88–103. doi: 10.3934/molsci.2016.1.88. http://www.aimspress.com/article/10.3934/molsci.2016.1.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Leinfelder KF, Beaudreau RW, Mazer RB. An in vitro device for predicting clinical wear. Quintessence International. 1989;20(10):755–761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Petersen RC. Micromechanics/Electron Interactions for Advanced Biomedical Research Saarbrücken. Germany: LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing Gmbh & Co. KG; 2011. Chapter 11 Wear of fiber-reinforced composite; pp. 163–167. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Petersen RC, Liu PR. SAMPE 2016. Symposium; Long Beach, CA: May 25, 2016. 3D-woven fiber-reinforced composite for CAD/CAM dental application, Society for Advanced Materials and Process Engineering. 2016. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5026051/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Liebenberg WH. Assuring restorative integrity in extensive posterior resin composite restorations. Quintessence International. 2000;31(3):153–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Drummond JL. Degradation, fatigue and failure of resin dental composite materials. Journal of Dental Research. 2008;87(8):710–719. doi: 10.1177/154405910808700802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Roulet JF. The problems associated with substituting composite resins for amalgam: a status report on posterior composites. Journal of Dentistry. 1988;16:101–113. doi: 10.1016/0300-5712(88)90001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Leinfelder KF. Posterior composite resins: the materials and their clinical performance. Journal of the American Dental Association. 1995;126(5):663–677. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1995.0247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Schriever A, Becker J, Heidemann D. Tooth-colored restorations of posterior teeth in German dental education. Clinical Oral Investigations. 1999;3:30–34. doi: 10.1007/s007840050075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cobb DS, Macgregor KM, Vargas MA, Denehy GE. The physical properties of packable and conventional posterior resin-based composites: a comparison. Journal of the American Dental Association. 2000;131(11):1610–1615. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2000.0091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Keogh TP, Bertolotti RL. Creating tight anatomically correct interproximal contacts. Dental Clinics of North America. 2001;45(1):83–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.El-Badrawy WA, Leung BW, Mowafy OE, Rubo JH, Rubo MH. Evaluation of proximal contacts of posterior composite restorations with 4 placement techniques. Journal of the Canadian Dental Association. 2003;69(3):162–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Loomans BAC, Opdam NJM, Roeters FJM, Bronkhorst EM, Burgersdijk RCW, Dörfer CE. A randomized clinical trial on proximal contacts of posterior composites. Journal of Dentistry. 2005;34:292–297. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Jordon RE, Suzuki M. The ideal composite material. Journal of the Canadian Dental Association. 1992;58(6):484–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Christiansen GJ. Overcoming challenges with resin in class II situations. Journal of the American Dental Association. 1997;128:1579–1580. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1997.0101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Council on Dental Materials. Instruments, and Equipment. The desirability of using radiopaque plastics in Dentistry: a status report. Journal of the American Dental Association. 1981;102:347–349. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1981.0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Overton JD, Sullivan DJ. Early failure of class II resin composite versus class II amalgam restorations placed by dental students. Journal of Dental Education. 2012;76(3):338–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Martinim AP, Anchieta RB, Rocha EP, Freitas AC, Jr, de Almeida EO, Sundfeld RH, Luersen MA. Influence of voids in the hybrid layer based on self-etching adhesive systems: a 3-D FE analysis. Journal of Applied Oral Science. 2009;17(Sp. Issue):19–26. doi: 10.1590/S1678-77572009000700005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Purk JH, Dusevich VM, Glaros A, Eick JD. Adhesive analysis of voids in class II composite resin restorations at the axial and gingival cavity walls restored under in vivo versus in vitro conditions. Dental Materials. 2007;23:871–877. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Cunningham J, Mair LH, Foster MA, Ireland RS. Clinical evaluation of three posterior composite and two amalgam restorative materials: 3-year results. British Dental Journal. 1990;169:319–323. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4807369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Roulet JF, Noack MJ. Criteria for substituting amalgam with composite resins. International Dental Journal. 1991;41(4):195–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Wilkie R, Lidums A, Smales R. Class II glass ionomer cermet tunnel, resin sandwich and amalgam restorations over 2 years. American Journal of Dentistry. 1993;6(4):181–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kaplowitz GJ. Achieving tight contacts in class II direct resin restorations. Journal of the American Dental Association. 1997;128:1012–1013. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1997.0308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Leinfelder KF. Resin restorative systems. Journal of the American Dental Association. 1997;128(5):573–581. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1997.0256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kraus S. Achieving optimal interproximal contacts in posterior direct composite restorations. Journal of the American Dental Association. 1998;129(10):1467. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1998.0052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Opdam NJM, Loomans BAC, Roeters FJM, Bronkhorst EM. Five-year clinical performance of posterior resin composite restorations placed by dental students. Journal of Dentistry. 2004;32:379–383. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Brackett MG, Contreras S, Contreras R, Brackett WW. Restoration of proximal contact in direct class II resin composites. Operative Dentistry. 2005;31(1):155–156. doi: 10.2341/04-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lee IB, Cho BH, Son HH, Um CM. Rheological characterization of composites using a vertical oscillation rheometer. Dental Materials. 2007;23:425–432. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2006.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kampouropoulos D, Paximada C, Loukidis M, Kakaboura A. The influence of matrix type on the proximal contact in class II resin composite restorations. Operative Dentistry. 2010;35(4):454–462. doi: 10.2341/09-272-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Chuang SF, Su KC, Wang CH, Chang CH. Morphological analysis of proximal contacts in class II direct restorations with 3D image reconstruction. Journal of Dentistry. 2011;39:448–456. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Chhabra N, Gyanani H, Rathore VPS, Shah P. Twist to matricing: restoration of adjacent proximal defects in a novel manner. International Journal of Applied and Basic Medical Research. 2016;6(1):71–2. doi: 10.4103/2229-516X.174022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Loomans BAC, Opdam NJM, Roeters FJM, Bronkhorst EM, Huysmans MCDNJM. Restoration techniques and marginal overhang in Class II composite restorations. Journal of Dentistry. 2009;37:712–717. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2009.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Liebenberg WH. Assuring restorative integrity in extensive posterior resin composite restorations: Pushing the envelope. Quintessence International. 2000;31:153–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Peumans M, Van Meerbeek B, Assherickx K, Simon S, Abe Y, Lambrechts P, Vanherle G. Do condensable composites help to achieve better proximal contacts? Dental Materials. 2001;17(6):533–541. doi: 10.1016/s0109-5641(01)00015-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Teich ST, Joseph J, Sartori N, Heima M, Duarte Dental floss selection and its impact on evaluation of interproximal contacts in licensure exams. Journal of Dental Education. 2014;78(6):921–926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Ren S, Lin Y, Hu X, Wang Y. Clinical evaluation of all-ceramic crowns fabricated from intraoral digital impressions based on the principle of active wavefront sampling. The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry. 2016;115(4):437–440. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Gohil KS, Talim ST, Singh I. Proximal contacts in posterior teeth and factors influencing interproximal caries. The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry. 1973;30(3):295–302. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(73)90186-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Keogh TP, Bertolotti RL. Creating tight, anatomically correct interproximal contacts. Dental Clinics of North America. 2001;45(1):83–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Dörfer CE, von Bethenfalvy ER, Staehle HJ, Pioch T. Factors influencing proximal dental contact strengths. European Journal of Oral Sciences. 2000;108:368–377. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0722.2000.108005368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Jernberg GR, Bakdash MB, Keenan KM. Relationship between proximal tooth open contacts and periodontal disease. Journal of Periodontology. 1983;54(9):529–533. doi: 10.1902/jop.1983.54.9.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Hancock EB, Mayo CV, Schwab RR, Wirthlin MR. Influence of interdental contacts on periodontal status. Journal of Periodontology. 1980;51(8):445–449. doi: 10.1902/jop.1980.51.8.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Petersen RC, Wenski EG. Society for Advanced Materials Process Engineering. Symposium; Long Beach, CA: 2002. May 12-16, Mechanical Testing of a Photocured Chopped FiberReinforced Composite; pp. 380–395. SAMPE 2002 Affordable Materials Technology-Platform to Global Value and Performance. [Google Scholar]

- 126.Sideridou I, Achilias DS, Spyroudi C, Karabela M. Water sorption characteristics of light-cured dental resins and composites based on BisEMA/PCDMA. Biomaterials. 2004;25:367–376. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00529-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Petersen RC. Micromechanics/Electron Interactions for Advanced Biomedical Research. Saarbrücken, Germany: LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing Gmbh & Co. KG; 2011. Appendix D Hydrophobic low-viscosity styrene-free vinyl ester resin systems; pp. 499–504. [Google Scholar]

- 128.Gajewski VES, Pfeifer CS, Fróes-Salgado NRG, Boaro LCC, Braga RR. Monomers used in resin composites: Degree of conversion, mechanical properties and water sorption/solubility. Brazilian Dental Journal. 2012;23(5):508–514. doi: 10.1590/s0103-64402012000500007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]