Abstract

Purpose

To determine the demographic, clinical, decision-making, and quality-of-life factors that are associated with treatment decision regret among long-term survivors of localized prostate cancer.

Patients and Methods

We evaluated men who were age ≤ 75 years when diagnosed with localized prostate cancer between October 1994 and October 1995 in one of six SEER tumor registries and who completed a 15-year follow-up survey. The survey obtained demographic, socioeconomic, and clinical data and measured treatment decision regret, informed decision making, general- and disease-specific quality of life, health worry, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) concern, and outlook on life. We used multivariable logistic regression analyses to identify factors associated with regret.

Results

We surveyed 934 participants, 69.3% of known survivors. Among the cohort, 59.1% had low-risk tumor characteristics (PSA < 10 ng/mL and Gleason score < 7), and 89.2% underwent active treatment. Overall, 14.6% expressed treatment decision regret: 8.2% of those whose disease was managed conservatively, 15.0% of those who received surgery, and 16.6% of those who underwent radiotherapy. Factors associated with regret on multivariable analysis included reporting moderate or big sexual function bother (reported by 39.0%; OR, 2.77; 95% CI, 1.51 to 5.0), moderate or big bowel function bother (reported by 7.7%; OR, 2.32; 95% CI, 1.04 to 5.15), and PSA concern (mean score 52.8; OR, 1.01 per point change; 95% CI, 1.00 to 1.02). Increasing age at diagnosis and report of having made an informed treatment decision were inversely associated with regret.

Conclusion

Regret was a relatively infrequently reported outcome among long-term survivors of localized prostate cancer; however, our results suggest that better informing men about treatment options, in particular, conservative treatment, might help mitigate long-term regret. These findings are timely for men with low-risk cancers who are being encouraged to consider active surveillance.

INTRODUCTION

Men who are diagnosed with localized prostate cancer in the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) era have faced challenging treatment decisions. The indolent course of most prostate cancers and the dearth of comparative treatment studies have left clinicians and patients uncertain as to how and whether to treat these cancers.1 Treatment complications, which occur frequently and vary by treatment modality, can adversely affect long-term quality of life.2,3 An evidence review commissioned by the US Preventive Services Task Force found that prostatectomy increased the risk of urinary incontinence by 20 percentage points and the risk of sexual dysfunction by 36 percentage points compared with watchful waiting.2 Corresponding risks for radiotherapy were 15 and 3 percentage points, respectively. Only radiotherapy was associated with bowel dysfunction. Consequently, treatment decisions are complex and must be based on a patient’s personal values, risk tolerance, and quality-of-life considerations.4 Whereas studies have consistently reported that most men are satisfied with their treatment selection,5-9 regret over selected treatment may be a more important and sensitive psychosocial outcome.10,11

Regret occurs when uncertainty about the best choice is unresolved or when an unfavorable outcome leads one to believe that another decision might have been preferable.12,13 Investigators have increasingly begun to measure regret among men who are treated for localized prostate cancer. A recent systematic review identified 28 studies on treatment regret published since 200314; however, the review showed numerous potential methodologic limitations in these studies, including inconsistent use of validated measures, failure to report absolute levels of regret, cross-sectional designs with convenience sampling, small numbers of participants, and minimal data on long-term survivors of cancer.14

The Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study (PCOS) was initiated in 1994 and 1995 to characterize clinical and quality-of-life outcomes in a large, population-based cohort of men with newly diagnosed prostate cancer.15 We previously evaluated satisfaction with treatment decisions among the cohort of PCOS participants with localized prostate cancer at 2 years after diagnosis.7 When resurveying this cohort 15 years after diagnosis, we added a validated instrument to measure decision regret.16 The purpose of this report was to determine the demographic, clinical, decision-making, and quality-of-life factors that are associated with treatment decision regret among long-term survivors of localized prostate cancer.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Subjects

PCOS enrolled men with newly diagnosed incident prostate cancer between October 1, 1994, and October 31, 1995, from six participating SEER sites: Connecticut, Utah, New Mexico, and the metropolitan areas of Atlanta, Los Angeles, and Seattle. Institutional review boards of each PCOS site approved the study. Detailed descriptions of study methodology have been previously reported.15

PCOS sampled a total of 5,672 participants from 11,137 eligible prostate cancer cases. Eligible patients were randomly selected within age-, race- or ethnicity-, and tumor registry–specific strata to ensure adequate demographic representation. PCOS oversampled men who were age < 60 years and those who were Hispanic and African American. Among the selected patients, 3,533 men (62%) completed health-related quality-of-life survey questionnaires 6 and/or 12 months after initial diagnosis. For the current analyses, we included men who were diagnosed with localized prostate cancer at age < 75 years who completed baseline and 15-year surveys. We selected the upper age limit of 75 years because screening, which predominantly detects localized cancer, has not been advised beyond age 75.17 We identified 934 men who met these criteria, including 696 who were initially treated with radical prostatectomy, 146 who had initial radiation therapy, and 92 who were initially treated conservatively, either with watchful waiting, defined as no active treatment, or androgen-deprivation therapy, within 1 year of diagnosis.

Data Collection

Participants completed baseline self-administered surveys 6 months after diagnosis. The survey included questions about baseline and current general and disease-specific health-related quality of life and urinary, bowel, and sexual function. Accuracy of the 6-month retrospective recall of function has been previously validated.18 The survey also assessed race and ethnicity, employment status, educational level, household income, insurance coverage, marital status, and comorbidity. Medical record abstractors obtained additional baseline information on diagnostic examinations, biopsy results, tumor characteristics, clinical staging, and treatment within 12 months after diagnosis. We assigned baseline risk groups on the basis of D’Amico classifications.19 Men were contacted again at 1, 2, 5, and 15 years after diagnosis to complete surveys that contained items on clinical outcomes and health-related quality of life.

The 15-year survey used items from the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item short-form health survey,20 the UCLA Prostate Cancer Index,21 and the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index-Comprehensive instrument22 to measure general and disease-specific health-related quality of life descriptions of urinary, bowel, and sexual function, and the perception of any problems with these functions. Each domain-specific summary scale was scored from 0 to 100, with higher scores representing better function.

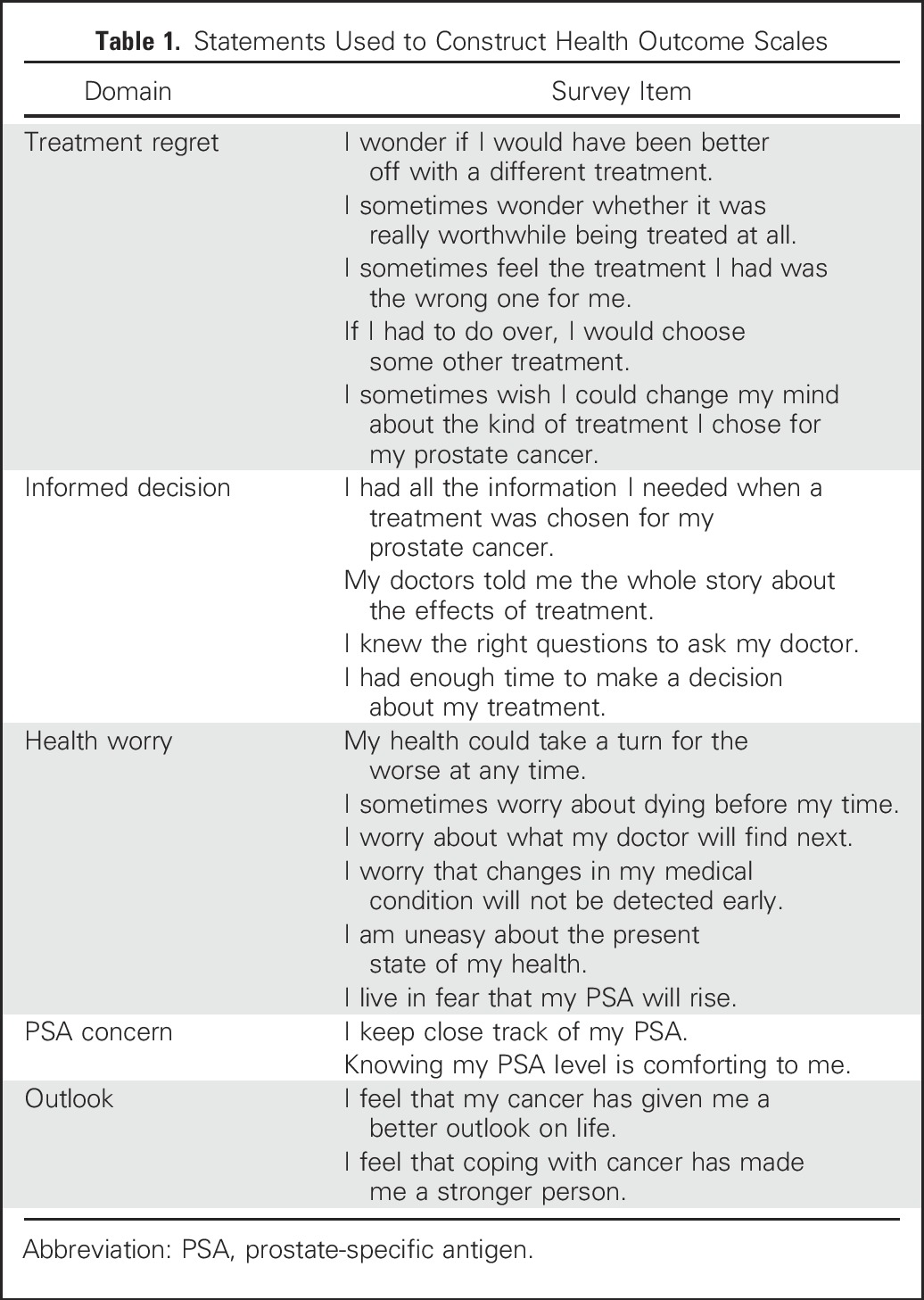

Additional items in the 15-year survey addressed subsequent cancer treatments, whether the patient believed that cancer was still present, and the effects of treatment on physical function, finances, and social relationships. We used Clark’s validated prostate cancer–related quality-of-life scales to measure perceptions of health worry (higher scores indicated greater worry), PSA concern (higher scores indicated greater concern), outlook (higher scores indicated better outlook), having made an informed decision (higher scores indicated more informed decisions), and treatment decision regret (higher scores indicated regret); statements included in each of these measures are listed in Table 1.16 Respondents were asked to rate how true the statements were for them, ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). Each of these scales was scored from 0 to 100 on the basis of the combined response to all related statements. We reported results for health worry, PSA concern, outlook, and informed decision making as means and standard errors. We followed Clark’s scoring procedure for the regret scale and classified those who scored ≥ 40 as being regretful.16

Table 1.

Statements Used to Construct Health Outcome Scales

We revised the informed decision scale by deleting two statements: “I am satisfied with the choices I made in treating my prostate” and “I would recommend the treatment I had to a close relative or friend.” We did so because these statements did not reflect baseline decision making. We scored the revised informed decision measure from 0 to 100 on the basis of the remaining four items. Cronbach’s α for the four items was .88.

Statistical Analysis

We first compared baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of respondents included in our analysis with those of all living nonrespondents. We then used contingency tables to examine the bivariate associations of demographic, socioeconomic, and clinical variables and perceptions of having made an informed decision, treatment decision regret, health worry, PSA concern, and outlook with initial treatment selection. We used multivariable logistic regression models to identify factors that were associated with regret. All models included age, race, and SEER registry; we included additional variables with P values < .10 on univariable analyses. Starting with the full model, the Wald test was used to determine which variables contributed the least to predicting regret and could be removed from the model. We selected education as the best measure of socioeconomic status. Other variables were highly collinear with education and had more missing values. We modeled separately the subset of patients who reported being cancer free at follow-up.

We performed all regression models with the SAS ProcSurveyFreq statistical package.23 We used the Horvitz-Thompson weight, the inverse of the sampling proportion for each sampling stratum (defined by age, race or ethnicity, and study area), to obtain unbiased estimates of regression parameters for all eligible patients with prostate cancer in the PCOS areas. All estimates presented in this report were weighted to this population. All P values were two sided.

RESULTS

After excluding participants who died before the 15-year survey (n = 126) and those who were age > 75 years at diagnosis, our survey response rate was 69.3%. Living nonrespondents were significantly more likely than respondents to be nonwhite (46.7% v 25.3%), unmarried (22.0% v 11.2%), without a college degree (72.3% v 44.0%), have three or more comorbid conditions (9.1% v 5.9%), and have intermediate- or high-risk prostate cancer (51.9% v 41.0%).

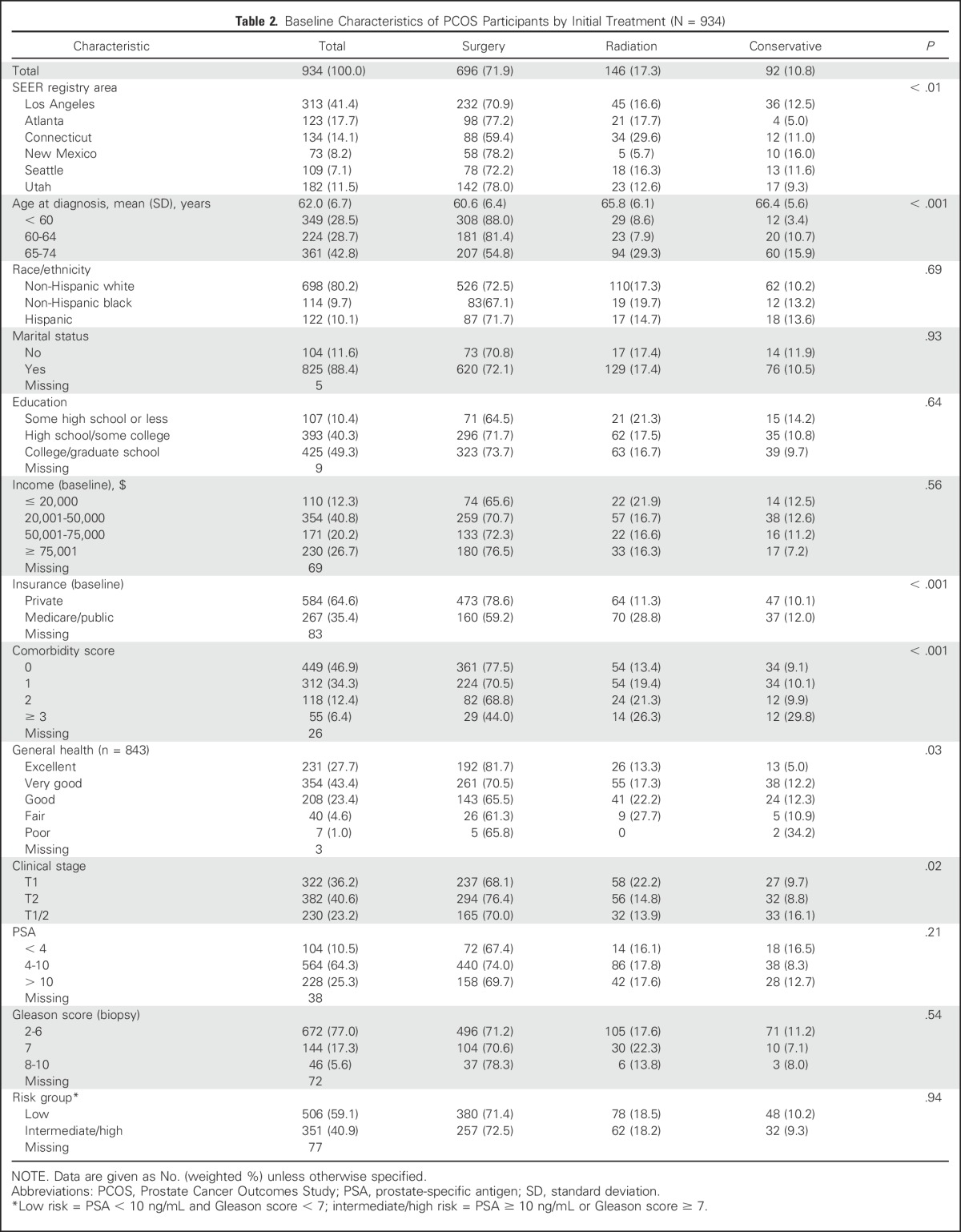

Most respondents had undergone radical prostatectomy, only 10.8% were treated conservatively (Table 2). Treatment selection varied by geographic area; younger, healthier, and privately insured men were most likely to undergo surgery.

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics of PCOS Participants by Initial Treatment (N = 934)

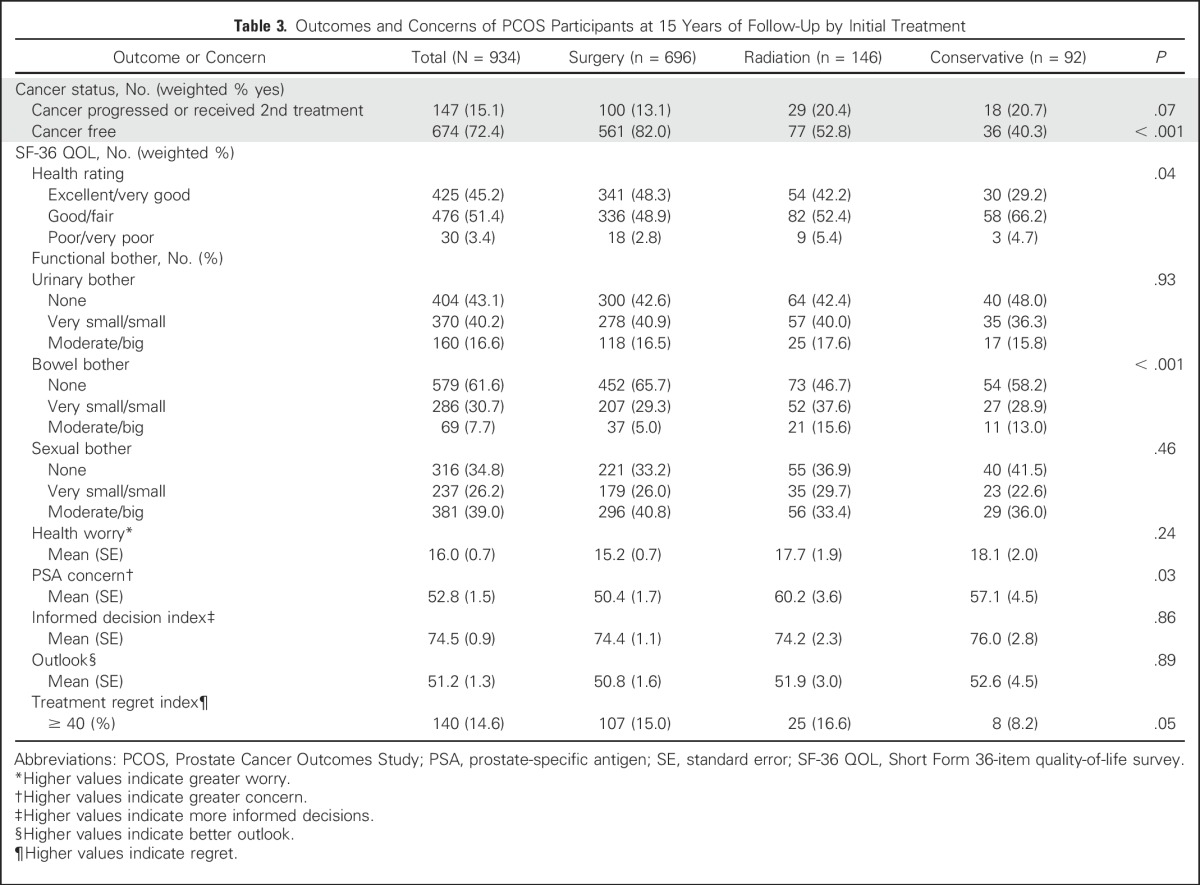

The self-reported 15-year clinical outcomes, health status, and amount of bother as a result of urinary, sexual, and bowel function are listed in Table 3. Men who underwent surgery were least likely to report an increasing PSA level and most likely to report being cancer free. Although few men reported being in poor or very poor health, men who were treated conservatively were least likely to classify themselves as having excellent to very good health status. The amount of reported urinary or sexual bother did not vary significantly by initial treatment, although more men reported moderate or big bother with sexual function (39.0%) than with urinary function (16.6%). Overall reported level of bother was lowest for bowel function, and men who underwent surgery were least likely to report moderate or big bowel bother. Table 3 also lists overall scores for health worry, PSA concern, informed decision making, and regret at 15-year follow. Men who underwent surgery reported the lowest level of PSA concern. Treatment decision regret (score ≥ 40) was expressed by 14.6% of men, with significant variation ranging from 8.2% of men who received conservative treatment to 15.0% of those who received surgery and 16.6% of those who underwent radiotherapy (P = .05).

Table 3.

Outcomes and Concerns of PCOS Participants at 15 Years of Follow-Up by Initial Treatment

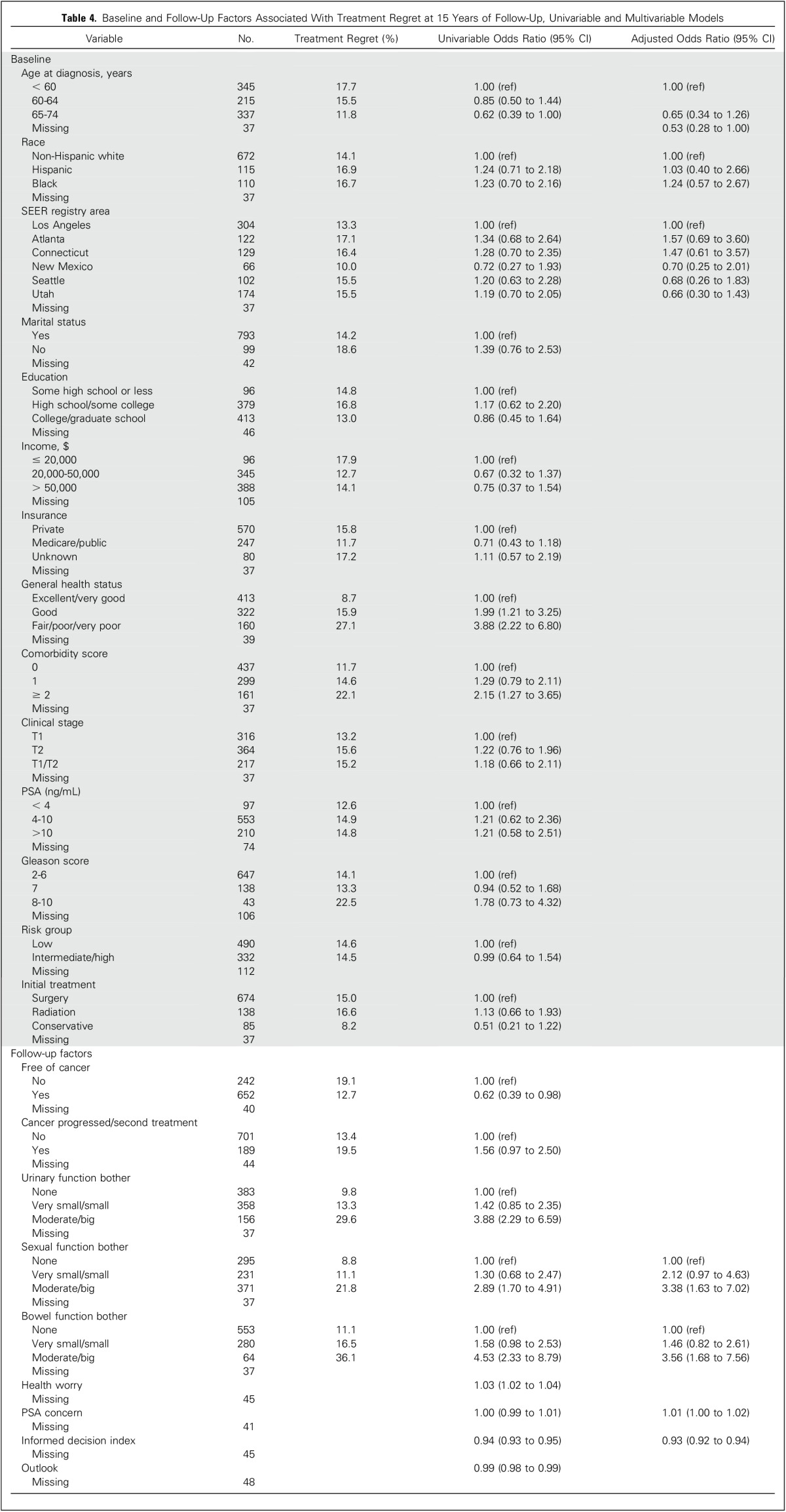

Univariable and multivariable associations between demographic and clinical factors with treatment decision regret are listed in Table 4. From multivariable analysis, we found that reporting moderate or big sexual function bother or moderate or big bowel function bother—compared with no bother—and greater PSA concern were significantly associated with regret, whereas older age at diagnosis and reporting having made an informed decision were inversely associated with regret. We found no associations between regret and moderate or big urinary bother (compared with no bother), poorer health (compared with excellent/very good), reporting being free of cancer, worrying about health, outlook, or reporting a history of cancer progression or receiving a second treatment. We also performed multivariable analysis for just men who reported being cancer free and found similar associations with regret (data not shown).

Table 4.

Baseline and Follow-Up Factors Associated With Treatment Regret at 15 Years of Follow-Up, Univariable and Multivariable Models

DISCUSSION

Most long-time survivors of localized prostate cancer in our population-based cohort did not express regret about their treatment selection 15 years after diagnosis. Our participants were age ≤ 75 years when diagnosed in the mid-1990s and the majority received active treatment. Being bothered by sexual or bowel dysfunction and PSA concern were associated with greater regret, whereas increasing age at diagnosis and the perception of having made an informed treatment decision were inversely associated with regret.

Our finding that decision regret is relatively uncommon is consistent with other studies of men who have been treated for localized prostate cancer14; however, the prevalence of regret (14.6%) in the PCOS cohort was toward the upper end (range, 2% to 18%) among studies that also used Clark’s scale.11,24-30 These findings might be explained by the longer PCOS follow-up period. Diefenbach has hypothesized that men’s initial concerns are about curing cancer and immediate treatment complications are seen as expected consequences of their cancer experience.25 Afterward, though, survivors may experience more regret as quality-of-life issues become increasingly important and they recognize that complications are permanent. Although we did not use the validated regret measure on earlier surveys, we found that among PCOS participants who completed the 2- and 15-year follow-up surveys, only 5% to 9% reported that they would “probably/definitely want another treatment” on the 2-year survey, whereas at 15 years, 11.8% responded that they “quite a bit” or “very much agreed” with the statement that “if I had it to do over, I would choose some other treatment.” These longitudinal PCOS data suggest that regret surrounding prostate cancer treatment decisions not only persists over time but might increase.

The increase in the proportion of men who would reconsider their treatment selection correlated with the declining functional outcomes observed in our cohort31; sexual and bowel bother were the quality-of-life factors most associated with regret. These measures combine perceived dysfunction with its appraisal as bothersome, which increases the correlation with regret relative to a measure of dysfunction alone. Other studies have similarly shown that perceiving treatment-related sexual, bowel, and urinary dysfunction as bothersome was associated with regret.25,30,32-34 Only approximately 16% of participants reported moderate or big urinary bother, and this was not significantly associated with regret on multivariable analyses. It is possible that men were expecting age-related declines in urinary function and so did not report being bothered by their symptoms, nor did they associate them with treatment regret.35

We found that higher PSA concern was associated with regret. This measure is based on preoccupation with PSA; Clark et al16 had previously shown a similar, albeit modest, correlation among men with previously (1 to 4 years earlier) treated localized prostate cancer. The authors concluded that this measure was capturing a different dimension of quality of life. Finding this association after 15 years suggests the complexity of evaluating quality-of-life outcomes in survivors of cancer. The extent to which a man is preoccupied with PSA as an indicator of disease is still associated with feelings of regret, independently of other measures of cancer control.

Increasing age at diagnosis was inversely related to regret, although we limited analyses to men age < 75 years. Among men age 65 to 74 years, 12% expressed regret compared with 18% of those age < 60 years at diagnosis. Morris and colleagues36 had found an interaction between age and race at 2.8 years of follow-up, with younger African American men expressing the highest level of regret. Sidana and colleagues37 found an 11% prevalence of regret among men age < 50 years who were surveyed 3 to 7 years after treatment. These authors hypothesized that the age effect could be related to a greater impact from adverse effects for younger men; older men may have already been aware of and accommodated to declining functional status.

Lack of informed decision making was highly associated with regret, regardless of whether the patient reported being cancer free. Because treatment decisions for localized prostate cancer are preference sensitive, men should be made aware of treatment options, their respective risks and benefits, and be engaged with their providers in making value-concordant decisions.38 Not surprisingly, studies have shown that being unprepared for prostate treatment complications and their adverse effect on quality of life may lead to more regret.27,32,36 This is particularly noteworthy given the high proportion of men who are diagnosed with low-risk disease for whom active surveillance is now considered an appropriate option given concerns about overtreatment.39 Regret expressed by our participants, who were surveyed in 2010, could reflect awareness of these recommendations. In this context, men who had no treatment complications or cancer recurrence might express regret if they came to realize that their treatment was unnecessary. Studies have also shown that men with passive roles in decision making had more decision regret those with more active roles.40,41 Conversely, prostate cancer treatment decision support interventions may reduce regret.42,43

Our study had some limitations. Whereas the informed decision-making scale results were highly correlated with regret, responses were subject to recall bias because participants were asked about decisions that occurred 15 years earlier. We cannot determine directionality and so do not know whether poor decision making predisposed men to express regret or whether regret clouded recollection of informed decision making. Furthermore, the shared-decision making paradigm, which is considered appropriate for such preference-sensitive decisions as treating localized prostate cancer, was not well developed when our informed decision scale was created. Consequently, the scale does not include important measures, such as knowledge, eliciting patient preferences, clarifying patients’ values, and assessing whether decisions were congruent with these values.44,45

Some of the estimated effect sizes were imprecise because of the relatively small sample size. We also found significant sociodemographic and clinical differences between respondents and nonrespondents. Our results may be less applicable to men in lower sociodemographic groups, African American and Hispanic men, and to men in poorer health. Nonrespondents were more likely to have had intermediate- and high-risk prostate cancers. These men were at increased risk of poorer cancer outcomes, which suggested that we might have underestimated the long-term prevalence of regret, particularly for those who selected less aggressive treatments.

Surveying survivors may have also introduced selection bias; however, the majority of our participants had low-risk features, including PSA levels < 10 ng/mL and Gleason scores < 7, and only a small number of them subsequently died of prostate cancer.46 When the PCOS cohort was diagnosed, most men with localized cancer received active treatment, particularly surgery, and the number who received conservative treatment was small.47 Nonetheless, these surviving patients who were conservatively treated were significantly less likely to report regret than those who received surgery. With support from influential guidelines on the basis of observational data,39,48 men with low-risk localized prostate cancer are now increasingly opting for active surveillance.47,49 Participants in the Prostate Testing for Cancer and Treatment trial had similar—and low—cancer-specific mortality whether they received active monitoring or active treatment.50 However, the active monitoring group reported better quality-of-life outcomes. Thus, our results suggest that undergoing active surveillance could reduce decisional regret. In addition, reporting not being free of cancer was not associated with regret for PCOS participants on multivariable analyses, which further supported the acceptability of active surveillance.

Regret was a relatively infrequently reported outcome among long-term survivors of localized prostate cancer; however, we found a higher level of regret in our study than in other studies that had observed men for a shorter period of time, which suggested that regret may increase with longer follow-up. Improved supporting initial treatment decision making through informing patients about treatment options and potential outcomes, helping patients identify treatment preferences, and clarifying values might help mitigate regret over the long term. These findings are particularly relevant now when men with low-risk cancers are facing challenging decisions between selecting an active treatment or active surveillance that presents a potential trade-off between cancer control and adverse effects.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank the men who participated in Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study, the physicians in the six SEER areas who assisted in collecting data from their patients and from medical records, all the study managers and chart abstractors for their efforts in data collection, and all the staff in the six cancer registries for their help with the study.

Footnotes

Supported by the National Cancer Institute Grant No. 1R01-CA114524-01A2; the following contracts from the each of the participating institutions: N01-PC-67007, N01-PC-67009, N01-PC-67010, N01-PC-67006, N01-PC-67005, and N01-PC-67000; and by Holden Comprehensive Cancer Center Support Grant No. P030-CA086862.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Richard M. Hoffman, Jack A. Clark, Peter C. Albertsen, Michael J. Barry, Michael Goodman, David F. Penson, Janet L. Stanford, Antoinette M. Stroup, Ann S. Hamilton

Provision of study materials or patients: Richard M. Hoffman, Peter C. Albertsen, Michael Goodman, David F. Penson, Janet L. Stanford, Antoinette M. Stroup, Ann S. Hamilton

Collection and assembly of data: Richard M. Hoffman, Peter C. Albertsen, Michael Goodman, David F. Penson, Janet L. Stanford, Antoinette M. Stroup, Ann S. Hamilton

Data analysis and interpretation: Mary Lo

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Treatment Decision Regret Among Long-Term Survivors of Localized Prostate Cancer: Results From the Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/site/ifc.

Richard M. Hoffman

No relationship to disclose

Mary Lo

No relationship to disclose

Jack A. Clark

No relationship to disclose

Peter C. Albertsen

Consulting or Advisory Role: Blue Cross & Blue Shield Technology Advisory Panel

Michael J. Barry

No relationship to disclose

Michael Goodman

No relationship to disclose

David F. Penson

Consulting or Advisory Role: Astellas Pharma, Dendreon

Research Funding: Medivation (Inst), Astellas Pharma (Inst)

Janet L. Stanford

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: SNP panel for predicting prostate cancer mortality (Inst)

Antoinette M. Stroup

No relationship to disclose

Ann S. Hamilton

No relationship to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.Hoffman RM, Penson DF, Zietman AL, et al. Comparative effectiveness research in localized prostate cancer treatment. J Comp Eff Res. 2013;2:583–593. doi: 10.2217/cer.13.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chou R, Croswell JM, Dana T, et al. Screening for prostate cancer: A review of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:762–771. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-11-201112060-00375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilt TJ, MacDonald R, Rutks I, et al. Systematic review: Comparative effectiveness and harms of treatments for clinically localized prostate cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:435–448. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-6-200803180-00209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin GA, Aaronson DS, Knight SJ, et al. Patient decision aids for prostate cancer treatment: A systematic review of the literature. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:379–390. doi: 10.3322/caac.20039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carvalhal GF, Smith DS, Ramos C, et al. Correlates of dissatisfaction with treatment in patients with prostate cancer diagnosed through screening. J Urol. 1999;162:113–118. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199907000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis JW, Kuban DA, Lynch DF, et al. Quality of life after treatment for localized prostate cancer: Differences based on treatment modality. J Urol. 2001;166:947–952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoffman RM, Hunt WC, Gilliland FD, et al. Patient satisfaction with treatment decisions for clinically localized prostate carcinoma. Results from the Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study. Cancer. 2003;97:1653–1662. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Resnick MJ, Guzzo TJ, Cowan JE, et al. Factors associated with satisfaction with prostate cancer care: Results from Cancer of the Prostate Strategic Urologic Research Endeavor (CaPSURE) BJU Int. 2013;111:213–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11423.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanda MG, Dunn RL, Michalski J, et al. Quality of life and satisfaction with outcome among prostate-cancer survivors. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1250–1261. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa074311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark JA, Wray NP, Ashton CM. Living with treatment decisions: Regrets and quality of life among men treated for metastatic prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:72–80. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu JC, Kwan L, Saigal CS, et al. Regret in men treated for localized prostate cancer. J Urol. 2003;169:2279–2283. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000065662.52170.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joseph-Williams N, Edwards A, Elwyn G. The importance and complexity of regret in the measurement of “good” decisions: A systematic review and a content analysis of existing assessment instruments. Health Expect. 2011;14:59–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2010.00621.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeelenberg M, Pieters R. A theory of regret regulation 1.0. J Consum Psychol. 2007;17:3–18. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Christie DR, Sharpley CF, Bitsika V. Why do patients regret their prostate cancer treatment? A systematic review of regret after treatment for localized prostate cancer. Psychooncology. 2015;24:1002–1011. doi: 10.1002/pon.3776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Potosky AL, Harlan LC, Stanford JL, et al. Prostate cancer practice patterns and quality of life: The Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1719–1724. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.20.1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clark JA, Inui TS, Silliman RA, et al. Patients’ perceptions of quality of life after treatment for early prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3777–3784. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moyer VA, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Screening for prostate cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:185–191. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-3-200808050-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Legler J, Potosky AL, Gilliland FD, et al. Validation study of retrospective recall of disease-targeted function: Results from the prostate cancer outcomes study. Med Care. 2000;38:847–857. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200008000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.D’Amico AV, Whittington R, Malkowicz SB, et al. The combination of preoperative prostate specific antigen and postoperative pathological findings to predict prostate specific antigen outcome in clinically localized prostate cancer. J Urol. 1998;160:2096–2101. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199812010-00041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Litwin MS, Hays RD, Fink A, et al. The UCLA Prostate Cancer Index: Development, reliability, and validity of a health-related quality of life measure. Med Care. 1998;36:1002–1012. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199807000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wei JT, Dunn RL, Litwin MS, et al. Development and validation of the expanded prostate cancer index composite (EPIC) for comprehensive assessment of health-related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Urology. 2000;56:899–905. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00858-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.SAS Institute . SAS/STAT® 13.1 User’s Guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu JC, Kwan L, Krupski TL, et al. Determinants of treatment regret in low-income, uninsured men with prostate cancer. Urology. 2008;72:1274–1279. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.11.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Diefenbach MA, Mohamed NE. Regret of treatment decision and its association with disease-specific quality of life following prostate cancer treatment. Cancer Invest. 2007;25:449–457. doi: 10.1080/07357900701359460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nguyen PL, Chen MH, Hoffman KE, et al. Cardiovascular comorbidity and treatment regret in men with recurrent prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2012;110:201–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kinsella J, Acher P, Ashfield A, et al. Demonstration of erectile management techniques to men scheduled for radical prostatectomy reduces long-term regret: A comparative cohort study. BJU Int. 2012;109:254–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steer AN, Aherne NJ, Gorzynska K, et al. Decision regret in men undergoing dose-escalated radiation therapy for prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;86:716–720. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chien CH, Chuang CK, Liu KL, et al. Changes in decisional conflict and decisional regret in patients with localised prostate cancer. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23:1959–1969. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davison BJ, Matthew A, Gardner AM. Prospective comparison of the impact of robotic-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy versus open radical prostatectomy on health-related quality of life and decision regret. Can Urol Assoc J. 2014;8:E68–E72. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Resnick MJ, Koyama T, Fan KH, et al. Long-term functional outcomes after treatment for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:436–445. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin YH. Treatment decision regret and related factors following radical prostatectomy. Cancer Nurs. 2011;34:417–422. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e318206b22b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berry DL, Wang Q, Halpenny B, et al. Decision preparation, satisfaction and regret in a multi-center sample of men with newly diagnosed localized prostate cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;88:262–267. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schroeck FR, Krupski TL, Sun L, et al. Satisfaction and regret after open retropubic or robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 2008;54:785–793. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.06.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Resnick MJ, Barocas DA, Morgans AK, et al. Contemporary prevalence of pretreatment urinary, sexual, hormonal, and bowel dysfunction: Defining the population at risk for harms of prostate cancer treatment. Cancer. 2014;120:1263–1271. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morris BB, Farnan L, Song L, et al. Treatment decisional regret among men with prostate cancer: Racial differences and influential factors in the North Carolina Health Access and Prostate Cancer Treatment Project (HCaP-NC) Cancer. 2015;121:2029–2035. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sidana A, Hernandez DJ, Feng Z, et al. Treatment decision-making for localized prostate cancer: What younger men choose and why. Prostate. 2012;72:58–64. doi: 10.1002/pros.21406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S. Shared decision making—Pinnacle of patient-centered care. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:780–781. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1109283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mohler JL.The 2010 NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology on prostate cancer J Natl Compr Canc Netw 8145, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davison BJ, So AI, Goldenberg SL. Quality of life, sexual function and decisional regret at 1 year after surgical treatment for localized prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2007;100:780–785. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clark JA, Talcott JA. Confidence and uncertainty long after initial treatment for early prostate cancer: Survivors’ views of cancer control and the treatment decisions they made. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4457–4463. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.2893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hacking B, Wallace L, Scott S, et al. Testing the feasibility, acceptability and effectiveness of a ‘decision navigation’ intervention for early stage prostate cancer patients in Scotland—A randomised controlled trial. Psychooncology. 2013;22:1017–1024. doi: 10.1002/pon.3093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mishel MH, Germino BB, Lin L, et al. Managing uncertainty about treatment decision making in early stage prostate cancer: A randomized clinical trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;77:349–359. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Informed Medical Decisions Foundation . Why Shared Decision Making? Boise, ID: Healthwise; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fowler FJ, Jr, Gallagher PM, Drake KM, et al. Decision dissonance: Evaluating an approach to measuring the quality of surgical decision making. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2013;39:136–144. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(13)39020-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hoffman RM, Koyama T, Fan KH, et al. Mortality after radical prostatectomy or external beam radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:711–718. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cooperberg MR, Carroll PR. Trends in management for patients with localized prostate cancer, 1990-2013. JAMA. 2015;314:80–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.6036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thompson I, Thrasher JB, Aus G, et al. Guideline for the management of clinically localized prostate cancer: 2007 update. J Urol. 2007;177:2106–2131. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weiner AB, Patel SG, Etzioni R, et al. National trends in the management of low and intermediate risk prostate cancer in the United States. J Urol. 2015;193:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.07.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hamdy FC, Donovan JL, Lane JA, et al. 10-year outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1415–1424. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]