Abstract

The United States lags behind other industrialized countries in its lack of inclusive and standardized parental leave policy after the birth or adoption of a child. Using data from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study (N=2,233), this study examines the patterns and predictors of fathers’ parental leave use, as well as its association with father-child engagement. Our findings indicate that the vast majority of employed fathers take parental leave, but they rarely take more than one week of leave. Fathers who have more positive attitudes about fatherhood and who live with the birth mother are especially likely to take leave, and to take more weeks of leave, than other fathers. Finally, we find that taking parental leave, and taking more weeks of parental leave, is positively associated with father engagement levels at one year and five years after the birth of his child.

Unlike other industrialized countries, the United States does not have a universal parental leave policy that offers inclusive, standardized, and paid parental leave after the birth or adoption of a child. Until recently, relatively little attention has been paid to the need for more generous parental leave policies in the U.S. (Craig & Mullan, 2011; Nepomnyaschy & Waldfogel, 2007). Correspondingly, few scholars have studied fathers’ parental leave patterns-- especially among disadvantaged and non-resident fathers. Also, because fathers’ use of parental leave is thought to be very short and is perceived to be uncommon, the association between paternity leave and father-child relationships is an understudied area; however, paternity leave has the potential to encourage fathers to become more involved in their new children’s lives (Haas & Hwang, 2008; Tanaka & Waldfogel, 2007). Therefore, we need to know more about the patterns of paternity leave-taking in the U.S. and the relationships between leave-taking and father-child engagement.

Extant studies of paternity leave in the U.S. typically have examined relatively privileged samples of fathers who are disproportionately married, continuously employed, and live with their children (e.g., Hyde, Essex, & Horton, 1993; Nepomnyaschy & Waldfogel, 2007). We know much less about the leave-taking behaviors among more disadvantaged fathers. By definition, disadvantaged fathers possess relatively low levels of education and income. They also are disproportionately racial-ethnic minority and unmarried fathers. In fact, there is evidence that being a racial-ethnic minority and unmarried parent are additional contributors to disadvantage (McLanahan & Percheski, 2008; Smock & Greenland, 2010).

It may be that paternity leave-taking among more disadvantaged fathers is comparable to leave-taking among the rest of the population of fathers. After all, American men do not typically have paid leave available to them and most appear to take less than one week of leave after the birth of a child (Han & Waldfogel, 2003; Nepomnyaschy & Waldfogel, 2007). Yet, more disadvantaged men also may be more (or less) likely to take paternity leave because they tend to have lower-paying jobs and more family hardships to address. For example, missing out on a relatively low wage from a fungible job to aid in the transition to caring for a new baby may be especially rational among disadvantaged men. Alternatively, disadvantaged men may see this as a particularly risky decision if they (and their families) especially rely upon income from work and if jobs are particularly hard to come by.

Similarly, we know very little about how paternity leave-taking may be associated with future father-child relationships, especially among more disadvantaged fathers. Because disadvantaged fathers are especially likely to disengage from frequent interactions with their children over time, one might imagine that the potential benefits of paternity leave-taking could especially enhance their father-child interactions (Marsiglio & Roy, 2012; McLanahan & Percheski, 2008). Indeed, research from outside of the U.S. suggests that there may be benefits, such as more frequent father-child interactions, among families of all social classes when a father takes parental leave (Haas & Hwang, 2008; Tanaka & Waldfogel, 2007). Nonetheless, one might expect that a similar pattern could only occur in the United States if more comprehensive parental leave policies that encourage paternity leave are implemented. Currently, with a relative lack of human capital and little federal regulation to offer benefits such as job protections, it may be too risky for disadvantaged fathers to take paternity leave and experience its potential benefits.

The purpose of this study is to analyze paternity leave-taking, and the extent to which paternity leave-taking predicts future father-child engagement, among more disadvantaged fathers in the U.S. We emphasize the significance of father identities as predictors of leave-taking and later father engagement with children. Specifically, this study contains three research aims. First, we examine the frequency and amount of parental leave-taking by disadvantaged fathers. Second, we assess the extent to which indicators of the salience and commitment of father identities, other father characteristics, and the co-parenting context at birth predict fathers’ leave-taking. Finally, we investigate the extent to which a father’s parental leave usage is predictive of his engagement levels with his child at one year and five years after the child’s birth. Below we introduce the background of the study, present our conceptual framework, and describe our hypotheses.

Background

It is useful to compare the history of parental leave policy and leave usage in the United States with other Western nations. The comparison suggests that more generous and father-directed parental leave policies, and corresponding leave usage, could encourage higher levels of family engagement and a more equal division of labor between mothers and fathers. Regardless, it is important to improve our understanding of paternity leave-use in the U.S. and the association between parental leave use and other indicators of family well-being, such as the nature of father-child relationship bonds.

Parental leave polices throughout the world vary in regard to how effective they are at encouraging fathers to take parental leave, how much parental leave is available to parents, and how much of the parents’ incomes are replaced while they are taking leave. Sweden is frequently lauded for its egalitarian gender values, and it also has some of the most far-reaching and well-developed policies of paid, government-mandated parental leave (Hook, 2006; Hook, 2010; O’Brien, 2009). In 1974, Sweden became the first country to introduce parental leave for fathers (Swedish Institute, 2011; Haas & Hwang, 2008; O’Brien, 2009). Parental leave for both parents was implemented specifically as a way to promote gender equality in Sweden, because, as stated by the late Swedish Prime Minister Olof Palme in 1972:

“The demand for equality… involves changes not only in the conditions of women but also in the conditions of men. One purpose of such changes is to give women an increased opportunity for gainful employment and to give men an increased responsibility for care of the children.”

(Baude, 1979, p. 151, cited by Haas & Hwang, 2008, p. 88)

In 1996, the European Union followed suit and implemented the EU Directive on Parental Leave, providing three months of unpaid parental leave to all employed people in Europe (O’Brien, 2009).

As of 2007, sixty-six nations had implemented paid parental leave available to fathers (O’Brien, 2009; Heyman, Earle, & Hayes, 2007). In the nations that make up the OECD, parental leave policies provide an average of ten months of parental leave (Waldfogel, 2001). Not surprisingly, fathers take longer parental leaves when leave is more institutionalized and associated with more generous benefits (O’Brien, 2009).

In her analysis of 24 countries, including several European countries, the United States, Canada, and Australia, O’Brien (2009) devised a typology of parental leave policies: “extended father-care leave with high income replacement” (15+ days of leave available for fathers and 50%+of earnings paid), “short father-care leave with high income replacement” (≤14 days available and 50%+ of earnings paid), “short/minimalist father-care leave with low/no income replacement” (< 14 days and <50% of earnings paid), and “no statutory father-care sensitive parental leave” (no parental leave policy for fathers).

In countries with extended parental leave available to fathers and high income replacement, fathers are permitted to take parental leave and, in some cases (e.g., Norway, Iceland, and Sweden), a certain amount of leave is reserved for one parent and cannot be transferred to the other. The parental leave model of short parental leave for fathers but high income replacement, on the other hand, does not specifically encourage or require fathers to take parental leave, and mothers generally still are expected primarily to take more extensive parental leave. In countries where there is very short parental leave with little or no income replacement, fathers are permitted to take leave after the birth of a child, but no entitlements are given to fathers to encourage them to take leave (O’Brien, 2009; Swedish Institute, 2011).

Paternity leave most widely is taken, and is taken for longer periods of time, when parental leave policies offer extended leave, high levels of income replacement, and leave specifically allocated for fathers’ usage (Craig & Mullan, 2011; O’Brien, 2009). In addition, higher levels of income replacement are associated with greater use of parental leave by fathers (O’Brien, 2009).

The United States, however, has no federal laws in place that universally guarantee fathers parental leave. By 1990, 21 states did require larger employers to offer some parental leave to their employees, but it was not until 1993, when the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) became federal law in the U.S., that workers of either sex were given the right to time off to care for a family member with a medical condition, with parental leave being covered under this policy. However, FMLA has major shortcomings: most workers in the U.S. do not qualify for FMLA because eligibility depends on already having worked 1,250 hours for a large employer (i.e., 50+ employees) over the past year, FMLA does not require any sort of compensation during leave time (it only requires that the employer hold the employee’s position for him or her), and in a one year span a person can take a maximum amount of twelve weeks of leave. Leave policies vary greatly by state and by employer, but in terms of federal law, the U.S. does not have a very progressive or inclusive leave policy, nor does it specifically encourage fathers to take parental leave (O’Brien, 2009; National Partnership for Women & Families, 2012; Nepomnyschy & Waldfogel, 2007).

Since the United States government fails to guarantee paid leave for new parents, whether or not a new parent can take leave depends on whether his or her employer (or a state law) provides this benefit (O’Brien, 2009; National Partnership for Women & Families, 2012). Just 38% of employees are provided with short-term disability insurance that could cover instances of parental leave, and only about ten percent of workers are employed at a workplace that provides paid leave specifically for having a child (National Partnership for Women & Families, 2012). Low-wage earners disproportionately are unlikely to be afforded any kind of leave benefits from employers (Berggren, 2008; National Partnership for Women & Families, 2012).

Clearly, the U.S. offers very little support for fathers to take paternity leave. Nonetheless, extant evidence suggests that most American fathers (89%) do take some parental leave from work (Nepomnyaschy & Waldfogel, 2007). However, the leave is typically taken for no more than one week—a fraction of the leave that fathers take in many other industrialized countries (Han & Waldfogel, 2003; Hyde et al., 1993; Nepomnyaschy & Waldfogel, 2007). Instead, mothers overwhelmingly take parental leave and often refrain from working full-time hours in paid labor for extended periods of time after the birth of a new child. These practices reinforce gendered specialization in labor, such that mothers disproportionately peform household labor and fathers disproportionately work in paid labor (Bianchi, Robinson, & Milkie, 2006; Hook, 2010; McLanahan & Sandefur, 2009; O’Brien, 2009; Waldfogel, 2001). There is also evidence that more disadvantaged fathers are less likely to take leave, and take fewer days of leave. In addition, institutional supports for taking parental leave, fathers’ egalitarian beliefs about gendered responsibilities, and fathers’ positive attitudes towards family seem to be positively associated with taking more paternity leave (Hyde et al., 1993; Nepomnyaschy & Waldfogel, 2007). Yet, the research on paternity leave patterns are sparse and we need to have a better understanding of leave patterns, particularly among more disadvantaged fathers and non-resident fathers.

There is even less research about the potential implications of paternity leave for family functioning in the U.S. Nonetheless, findings seem to align with international research that consistently finds that paternity leave usage is associated with increased parental engagement with children, at least in the short term (O’Brien, 2009; Haas & Hwang, 2008; Pleck, 1993; Nepomnyaschy & Waldfogel, 2007; Tanaka & Waldfogel, 2007). Additionally, it appears as though fathers are more engaged with their children if they have taken larger amounts of leave (Haas & Hwang, 2008; Nepomnyaschy & Waldfogel, 2007; O’Brien, 2009; Pleck, 1993).

Given concerns that father absence and disengagement in the lives of their children especially among disadvantaged fathers—constitute a major social problem (McLanahan & Percheski, 2008; McLanahan & Sandefur, 2009), it is especially important to understand the extent to which paternity leave may encourage the nurturance of father-child relationships. However, there may not be enough variance in (disadvantaged) U.S. fathers’ parental leave usage to create a significant relationship between the length of a father’s parental leave and his engagment as his child ages.

In sum, it is notable that the U.S. offers little support for paternity leave-taking. Other industrialized nations prioritize the offering of more generous parental leave policies and often encourage paternity leave, in particular. Furthermore, the cross-national research on paternity leave suggests that more universal, father-directed, and generous parental leave policies increase fathers’ leave-taking. Also, there is evidence that father’s leave-taking is positively associated with subsequent father engagement.

Given the unique U.S. social context in which parental leave is not very institutionalized, it is especially important to understand the patterns of fathers’ leave-taking and the implications that these patterns may have for subsequent father-child interactions. Scant research has been done on paternity leave in the U.S., and especially on the behaviors of disadvantaged fathers. The patterns, and potential benefits, of paternity leave usage in the U.S. may lead to recommendations for the U.S. to adopt more mainstream and generous parental leave policies.

Conceptual Framework

Family leave policies and the cultural patterns of leave-taking are not the only contextual factors that matter in predicting paternity leave use. Identity theory may help explain fathers’ leave-taking behaviors after the birth or adoption of a child and why parental leave may be associated with future father engagement. Paternity leave provides an important opportunity for father engagement, family bonding, and increasing or solidifying the salience of father identities.

Father Identity Theory

One man may occupy the statuses of a father, a husband, and an employee, in addition to a number of others, and the expectations of each of these statuses may complement or conflict with one another. Identity theory, which is rooted in symbolic interactionism, explains that a person will actively attach meaning and importance to his or her statuses and the specific roles that he or she recognizes as being attached to the statuses. The relative importance of particular statuses and roles can be classified by their perceived salience. Largely, identities are shaped through interactions within a person’s social networks. Relationship commitments to significant others tend to influence the salience of certain statuses and roles, and the social and social-psychological bonds that maintain identities often influence social behaviors (Stryker, 1968; Stryker & Burke, 2000). An identity is stronger, and one is more likely to embrace the expectations of a specific identity, when it has both high commitment and high salience (Stryker & Burke, 2000; Killewald, 2013).

The salience of being a father, the salience of particular fathering roles, and a father’s relationship commitments with significant others are likely to shape paternal leave-taking behaviors. In turn, paternal leave-taking may strengthen or solidify father identities and encourage future father engagement. First, the salience of the status of fatherhood is likely to influence paternal leave-taking. For example, a father who has more positive attitudes towards fatherhood may be more likely to take parental leave, and perhaps a greater amount of parental leave, than a father who is ambivalent or even upset about being a father. Previous research on disadvantaged fathers documents a range of responses to having a new child, but generally highlights positive attitudes about fatherhood (Edin & Nelson, 2013; Knoester, Petts, & Eggebeen, 2007). We expect that these attitudes will differentiate paternal leave-taking decisions.

Second, the salience of particular fathering roles may affect paternal leave-taking behaviors. Societal expectations of fatherhood roles are often unclear and at times these roles are not necessarily compatible with one another. Roles may include caretaking, protecting, breadwinning, teaching, and other responsibilities. The prioritization of these roles is also unique to every individual, depending on circumstance and background. For example, one man may think the most important role of a father is to be a wage earner and support his children financially, while another may feel that the role of caregiver is of greater importance (Ihinger-Tallman, Pasley, & Buehler, 1993; Killewald, 2013). Men who think that breadwinning is an especially important role of a father may be less likely to take parental leave. In contrast, men who especially value providing direct care may be more likely to take parental leave and may take greater amounts of parental leave. There is evidence that more disadvantaged fathers may be more likely to see themselves, and want others to see them, as more than just financial providers. Nonetheless, more disadvantaged fathers may be less able to give up wages in order to take time off from work to care for their new children (Edin & Nelson, 2013; Nelson, 2004).

Finally, relationship commitments with significant others may affect paternal leave-taking behaviors. Social bonds with significant others who value fatherhood may encourage men to embrace father identities and perform fathering roles. Relationship commitments also hold men accountable for their behaviors, beyond their formative influence on father identities (Ihinger-Tallman et al., 1993; Stryker, 1968; Stryker & Burke, 2000). Thus, fathers who live with their children’s mothers at birth may be more likely to take greater amounts of parental leave than fathers who do not live with their children’s mothers. Furthermore, compared to men without involved fathers, men who had actively involved fathers of their own may be more likely to take greater amounts of parental leave. Among disadvantaged fathers, the nature of relationship commitments may be especially important as reflections of relative levels of income and education, and also as symbols of the strength of social bonds (Edin & Nelson, 2013; McLanahan & Percheski, 2008).

Indeed, father identities are likely to shape paternal leave-taking behaviors. The salience of being a father, the salience of particular fathering roles, and a father’s relationship commitments with significant others are key dimensions of father identities. Accordingly, taking paternity leave after the arrival of a new child also may solidify or increase the salience of father identities and may lead to higher levels of father engagement as the child ages. Taking greater amounts of paternity leave may be more likely to lead to higher levels of father engagement than taking lessser amounts of paternity leave.

Additional Factors in Predicting Parental Leave Usage and Father Engagement

Beyond father identities, there are many other factors that influence a father’s decision and ability to take parental leave and to engage in activities with his child. These include: a) gendered culture and organizations, and b) a father’s human capital and other characteristics. The gendered culture and organization of parents’ workplaces likely have a significant impact on whether or not a new father takes parental leave and, if he does, how much leave he will take (Bygren & Duvander, 2006; Haas, Allard, & Hwang, 2002; Haas & Hwang, 1995). Since mothers are expected to time off from work after the birth of their children, fathers’ use of leave is much more likely to be influenced by the culture of their workplaces (Bygren & Duvander, 2006).

In some workplaces, for example, parental leave is taken often and used generously, which increases the possibility that a new father will ask for and receive more leave time (Bygren & Duvander, 2006). In a study of private companies’ levels of accomodation for fathers, many fathers stated that it was “relatively difficult to adjust work times according to children’s schedules at school or daycare, take parental leave part-time, take parental leave full-time for 3 months, reduce work hours by 25% to care for childen and take parental leave full-time for 6 months” (Haas, Allard, & Hwang, 2002, p. 336). Even if a workplace is supportive of a father’s decision to take parental leave, a perception that management feels negatively about parental leave may thwart a new father from asking for as much time off as he wants or needs (Haas, Allard, & Hwang, 2002).

While some of this perceived negativity may be interpreted incorrectly by the new father, many times the lack of support is quite real. Taking time off for parental leave indeed can cost the company money if an absence decreases productivity or requires that the company hire a temporary replacement, and additionally may create more work for other employees (Bygren & Duvander, 2006). This is true for any parent who has a career, but as stated earlier, women are expected to take parental leave, so it is more accepted than for fathers (Bygren & Duvander, 2006). This gendered expectation severely limits a man’s propensity to take a significant amount of leave to spend time with his young children (Haas & Hwang, 1995).

Though FMLA is a gender-neutral policy in regards to parental leave, Berggren (2008) argues that the reason that it is so limited is because women are not seen as equals to men in the workforce and are still expected to leave paid work to be full-time mothers if the need arises. In a study of undergraduate students in the midwestern United States, it was found that survey-takers viewed parents who took some parental leave following the birth of a child positively, regardless of the gender of the parent (Coleman & Franiuk, 2011). However, men who stayed at home with children indefinitely or for a very long time still were viewed negatively while women who did so were viewed somewhat less negatively; despite the growing acceptance of fathers taking nurturing roles, mothers were still viewed as the more socially acceptable primary caregiver (Coleman & Franiuk, 2011). More inclusive policies are not seen as a priority of the federal government because women are not seen as a priority in the workforce, but rather as people who can be depended on to be present in the home when necessary (Berggren, 2008). Thus, in this study we expect to find that fathers will use a modest amount of parental leave after the birth of their children.

Human capital includes income, occupational status, education, and age. There are demographic differences between men who do and do not take parental leave (Nepomnyaschy & Waldfogel, 2007; O’Brien, 2009; Tanaka & Waldofgel, 2007). Parents with unstable employment are less likely to qualify for parental leave benefits or full entitlements, and low-income families are overrepresented in this group (O’Brien, 2009). Men are more likely to take parental leave if their families have higher income, if they have high levels of education, and if they are employed in the public sector (Bygren & Duvander, 2006; Haas, Allard, & Hwang, 2002; Haas & Hwang, 1995; Nepomnyaschy & Waldfogel, 2007; O’Brien, 2009; Sundström & Duvander, 2002). Fathers’ human capital also is linked to father engagement activities (Marsiglio & Roy, 2012).

There is evidence of correlation between the ages of the parents and the father’s use of parental leave, as parents who are younger are more likely to share parental leave than older parents (Sundström & Duvander, 2002). Since young parents are more likely to divide leave more equally, this may indicate a changing attitude of gender relations within younger generations. However, these decisions may be different in disadvantaged families, as there is evidence that disadvantaged families tend to hold more strict gender role expectations than their more advantaged counterparts (Brewster & Padavic, 2000).

In sum, measures of human capital and other father characteristics may affect a man’s decision to take leave. Human capital and other father characteristics may also influence how engaged a father is with his children (Ihinger-Tallman et al., 1993; Marsiglio & Roy, 2012).

Hypotheses

We focus on four hypotheses in this study. First, father identity theory emphasizes the salience of one’s identity in predicting future behaviors (Killewald, 2013; Stryker & Burke, 2000). Positive attitudes towards fatherhood may reflect the salience of father identities. Thus, we anticipate that fathers with more positive attitudes towards fatherhood will be more likely to take parental leave, and will take more leave, than fathers with more negative attitudes towards fatherhood.

Second, while gendered parenting expectations are evolving, literature shows that the breadwinning role of the father still is seen as crucial, and nurturing is seen primarily as a mother’s role (Coleman & Franiuk, 2011; Haas, Allard, & Hwang, 2002; Haas & Hwang, 2008). Men who attribute particular salience to a breadwinning role may be less likely to take parental leave, while men who attribute particular salience to a direct caregiving role may be more likely to take parental leave. Accordingly, we hypothesize that men who particularly value their role as a breadwinner will be less likely to take significant amounts of parental leave. Men who particularly value their role as a caregiver will be more likely to take significant amounts of parental leave.

Third, relationship commitments with significant others, such as the child’s mother and his own father, may increase the salience of father identities and encourage fathers to take parental leave. Therefore, we expect that fathers who live with their children’s mothers or who had involved fathers are especially likely to take greater amounts of parental leave than fathers who do not live with their child’s mother or did not have involved fathers.

Finally, taking paternity leave may solidify or increase the salience of father identities. This process may encourage a father to be more engaged as his child ages. Indeed, previous work has found that a father’s use of parental leave can be beneficial to his relationship to his child if he takes a significant amount of time off of work to spend with the child (Haas & Hwang, 2008; Nepomnyaschy & Waldfogel, 2007). Thus, we hypothesize that taking paternity leave, and taking greater amounts of paternity leave, will be positively associated with fathers’ engagement levels at one year and five years after the birth of their children.

Method

Sample

We use data from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study (FFCWS). The FFCWS is a longitudinal study of a cohort of nearly 5,000 children born in the late 1990s and their families from 20 cities in the United States. It was designed to focus on the families formed by unmarried parents in urban areas, and subsequently contains disproportionate numbers of racial-ethnic minority and disadvantaged parents compared to the population of the U.S. For example, less than 20% of the parents in the FFCWS are White and nearly 75% of the parents are unmarried parents. Overall, 4,789 mothers and 3,742 fathers were interviewed at the time of their new children’s births. Eighty-two percent of the fathers were interviewed one year later. About 75% of the original sample of fathers remained in the study five years later. The FFCWS is ideal for our analysis because it provides information about a recent and disadvantaged cohort of urban American families. Little is known about the paternity leave-taking patterns, and the implications of these patterns for father-child engagement, among this population.

We focus on data collected from the fathers and mothers in the study at Wave 1 (baseline survey at the time of the child’s birth), Wave 2 (one year after baseline), and Wave 4 (five years after baseline). Because we used questions that were not asked in the first two cities in which data were gathered for some of our independent and dependent variables, our main sample contains information from fathers from 18 cities who were working at the time of their new child’s birth1 and who were interviewed one year later2 about their leave-taking experiences (N = 2,233). Due to attrition, the number of observations is reduced to 1,793 in the analyses that contain data from Wave 4.3 Listwise deletion of missing data results in slightly lower sample sizes for our regression analyses. The descriptive statistics of the variables used in our analyses are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Variables in Analyses

| Full sample of employed fathers (N=2,233)

|

Men who took parental leavea (N=1,780)

|

Men who did not take parental leaveb (N=453)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | |

| Sociodemographic characteristicsc | ||||||

| Father’s age (15-53) | 28.18 | (7.02) | 28.34 | (7.00) | 27.57 | (7.06) |

| Race-ethnicity | ||||||

| White | 0.26 | (0.44) | 0.30 | (0.46) | 0.10 | (0.31) |

| Black | 0.44 | (0.50) | 0.39 | (0.49) | 0.64 | (0.48) |

| Hispanic | 0.26 | (0.44) | 0.27 | (0.45) | 0.21 | (0.41) |

| Other race | 0.04 | (0.20) | 0.04 | (0.20) | 0.05 | (0.21) |

| Education | ||||||

| Less than high school | 0.26 | (0.44) | 0.25 | (0.43) | 0.30 | (0.46) |

| High school | 0.35 | (0.48) | 0.34 | (0.47) | 0.41 | (0.49) |

| Some college/technical school | 0.24 | (0.43) | 0.25 | (0.43) | 0.21 | (0.41) |

| College or more | 0.14 | (0.35) | 0.16 | (0.37) | 0.07 | (0.26) |

| Incomed | 10.30 | (0.94) | 10.35 | (0.93) | 10.10 | (0.94) |

| Attitudes/beliefse | ||||||

| Attitudes towards fatherhoodf | 0.06 | (0.76) | 0.09 | (0.74) | -0.04 | (0.83) |

| Importance of providing financial supportg | ||||||

| Importance of providing direct careg | 2.91 | (0.29) | 2.91 | (0.29) | 2.92 | (0.28) |

| Family characteristicsh | ||||||

| Residency status | ||||||

| Non-resident | 0.24 | (0.42) | 0.19 | (0.39) | 0.41 | (0.49) |

| Cohabiting with mother | 0.44 | (0.50) | 0.44 | (0.50) | 0.43 | (0.50) |

| Married to mother | 0.33 | (0.47) | 0.37 | (0.48) | 0.15 | (0.36) |

| Involvement of father’s biological fatheri | 2.13 | (0.83) | 2.18 | (0.82) | 1.94 | (0.84) |

| Child’s mother expects to workj (1=yes) | 0.82 | (0.38) | 0.81 | (0.39) | 0.88 | (0.33) |

| Father has other children (1=yes) | 0.58 | (0.49) | 0.57 | (0.50) | 0.60 | (0.49) |

| Parental leave usek | ||||||

| Leave use after child’s birth (1=yes) | 0.80 | (0.40) | 1.00 | (0.00) | 0.00 | (0.00) |

| Weeks of leave taken (1-5+) | 1.15 | (1.00) | 1.45 | (0.92) | 0.00 | (0.00) |

| Weeks of paid leave taken (1-5+) | 0.61 | (0.92) | 0.77 | (0.97) | 0.00 | (0.00) |

| Engaged with child, days/weekl | ||||||

| One year after birth | 4.42 | (1.64) | 4.57 | (1.51) | 3.84 | (1.97) |

| Five years after birthm | 3.44 | (1.73) | 3.54 | (1.67) | 3.04 | (1.92) |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

Sample of men who took at least one week of parental leave.

Sample of men who did not take any parental leave.

Fathers’ characteristics at Wave 1 (about the time of the child’s birth).

Natural logarithm of household income.

Measured at Wave 1.

Standardized mean of three measures of the men’s attitudes towards fatherhood (alpha=0.74).

Measures of men’s opinions about importance of these roles (1= not important, 3= very important).

Measured at time of child’s birth

Measure of involvement of the fathers of the men (1= not involved, 3= very involved).

Taken from mothers’ reports at Wave 1.

Measured at Wave 2 (when child was about one year old)

Number of days per week the father is engaged, formed by an average of seven measures of engagement.

Since this variable is taken at Wave 4, the sample size of this variable is reduced. Full sample: N=1,793. Among fathers who took parental leave: N=1,439. Among fathers who did not take parental leave: N=354.

Variables

Dependent variables

Our dependent variables indicate fathers’ leave-taking and engagement behaviors. First, we use the constructs of whether or not a father took leave (0= no, 1= yes) and how many weeks of leave he took (0= 0, 5= 5+) as dependent variables. These variables are formed from fathers’ reports of their leave-taking behaviors, from the interviews that occurred one year after their children’s birth. Second, in predicting father engagement after one year and five years, we use measures of how many days per week a father engages in seven specific behaviors with his child (e.g., “sing songs or nursery rhymes to child,” “tell stories to child,” “put child to bed”). These measures derive from fathers’ one year and five year reports of how many days per week they were engaged in these activities with their children. We use the average responses for how many days per week a father spends engaging with his child in these specific activities after one year (0-7) and after five years (0-7) as the engagement variables.

Independent variables

Our primary independent variables reflect father identities. These include each father’s reports of his positive attitudes towards fatherhood, reports of how much he values the role of providing financial support, reports of how much he values the role of direct caregiving, and indicators of his relationships with both his child’s birth mother and his own father. We measure men’s positive attitudes towards fatherhood by using three questions that asked fathers how much they agreed (1= strongly disagree, 4= strongly agree) with statements about fatherhood. The three statements were: “Being a father and raising children is one of the most fulfilling experiences a man can have,” “I want people to know that I have a new child,” and “Not being a part of my child’s life would be one of the worst things that could happen to me.” We formed a scale from these correlated items by first standardizing the individual items and then taking the mean value as the scale score (alpha= 0.74). Other independent variables were formed from single questions and indicate: a) how much the father values the role of financial supporter (1= not important, 3 = very important), b) how much he values the role of direct care provider (1 = not important, 3 = very important), c) if he was married to (0= no, 1= yes) or cohabiting with (0= no, 1= yes) his child’s mother at the time of the child’s birth, and d) the level of involvement by his own biological father in his life (1= not involved, 3= very involved). All of these variables are formed from the father’s Wave 1 reports.

For predicting father engagement after one year and five years, the variables of leave usage (0= no, 1= yes) and weeks of leave taken (0= 0, 5= 5+) are the primary independent variables. The independent variables from the first set of analyses are included in these models as well.

Control variables

The control variables in this study include indicators of each father’s age, race-ethnicity, household income, education, whether he has other children, and of the birth mother’s expected work status. All the control variables are drawn from father’s responses in the baseline interviews, except for the birth mother’s expected work status (which was taken from the mother’s baseline reports). Age is measured in years. Race-ethnicity consists of a series of dummy variables. White, non-Hispanic acts as the reference category (0= no, 1= yes) and there are variables for Black (0= no, 1= yes), Hispanic (0= no, 1= yes), and other race-ethnicity (0= no, 1= yes). We took the natural logarithm of household income in dollars. For educational attainment, we use a high school education (0= no, 1= yes) as the reference category and include dummy variables for less than a high school education (0= no, 1= yes), some college education (0= no, 1= yes), and a college education or higher (0= no, 1= yes). The final control variables measure whether the father has other children (0= no, 1= yes), and whether the mother expected to work (0= no, 1= yes).

Analytical Strategy

There are three stages in our analyses. First, we investigate general leave-taking patterns. We generate descriptive statistics for the sample and focus on the indicators of leave usage, number of weeks taken, and number of paid weeks taken. To aid in the understanding of the patterns of father’s leave-taking, we present descriptive characteristics separately for all fathers, fathers who took parental leave, and fathers who did not take parental leave. We also present fathers’ reports of why they did not take parental leave in order to understand better the reasons men choose to forego taking parental leave after the birth of a child.

Second, we analyze parental leave use by fathers. Initially, we use a logistic regression model to predict the likelihood that employed fathers take leave after the birth of a child. Then, we use an ordinary least-squares (OLS) regression model to predict the number of weeks that fathers take leave.

Finally, we use OLS regression models to focus on the relationships between father’s leave-taking behaviors and his engagement in activities with his new child one year and five years after the child’s birth. We predict whether leave-taking itself is associated with father engagment and whether more weeks of parental leave use is associated with greater father engagment.

Results

Overall, the results indicate that the vast majority of disadvantaged fathers take some parental leave, although they tend to take very little leave. As expected, there is evidence that positive attitudes about fatherhood and relationship commitments with significant others are significant predictors of parental leave. However, our expectation that the salience of specific parenting roles predicts paternal leave-taking is not supported. Finally, we find that fathers’ leave-taking behaviors are associated with fathers’ engagement one year and five years after the birth of their new children.

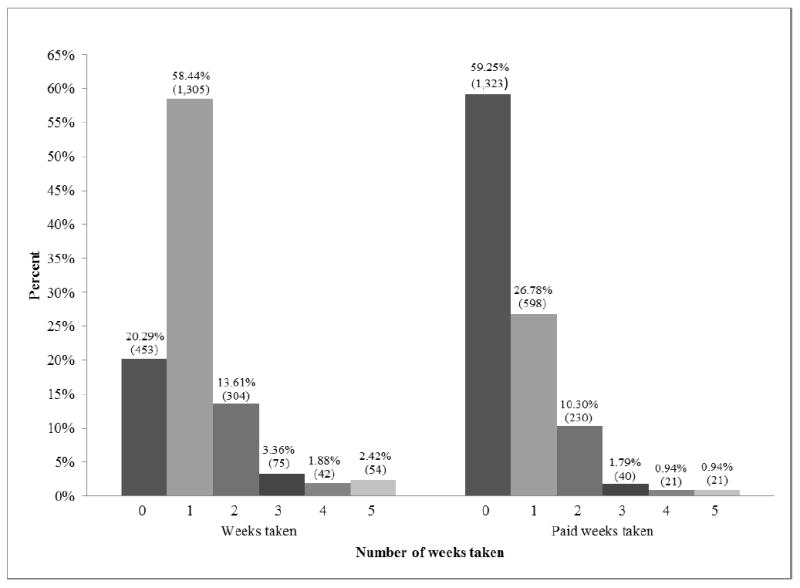

As shown in Figure 1, most men (79.71%) who are working when their children are born do take at least some parental leave after the birth of a new child. The majority of fathers take only one week of leave (58.44%), but there are a number of fathers (2.42%) who take five or more weeks of leave. Even though a large number of the fathers in this sample take leave, only 40.75% of all of the fathers were able to take some paid parental leave. Nonetheless, paid parental leave-taking accounts for just over half of all leave that was taken. Yet, it is important to note that paid leave includes vacation and sick-time leaves that are paid.

Figure 1. Parental leave taken by employed fathers after the birth of a new child (N=2,233).

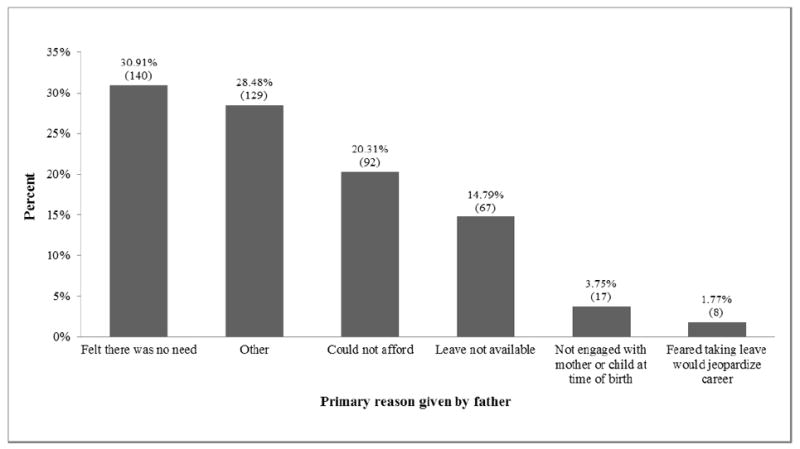

As shown in Figure 2, there are a variety of reasons why fathers say that they do not take parental leave. Only 20.31% of the fathers who did not take parental leave said that the reason was that they could not afford to take leave. Most commonly, men said that the reason they did not take leave is that they feel there was no need for them to do so (30.91%). It was less common for men to report that they did not take leave because it was not available (14.79%) or because they felt it would put their careers in jeopardy (1.77%). Overall, these results show that while a majority of men want to and do take leave, almost a third of those who choose not to take parental leave do so because they feel that there is no need for them to do so.

Figure 2. Why employed fathers do not take parental leave (N=453).

There are several significant predictors of fathers’ parental leave use. Table 2 shows the logistic regression results of the likelihood that the fathers in the sample took leave. A man’s positive attitude towards fatherhood is positively associated with his taking parental leave (Exp. b= 1.14, p < 0.1). Also, the involvement of a man’s father when he was a child is positively correlated with the man’s leave taking (Exp. b= 1.18, p <0.05). For example, a man whose father was somewhat involved is 18% more likely to take leave than a man whose father was not involved when he was younger. The residential status of the father also is correlated with parental leave taking. Men who are cohabiting with the children’s mothers at the time of birth are 82% more likely to take leave (p < 0.001) than fathers who live apart from the birth mothers. Men who are married to their children’s mothers are almost three and a half times more likely to take parental leave than nonresident fathers (Exp. b=3.47, p < 0.001). In addition, compared to White fathers, Black fathers are far less likely to take parental leave (Exp. b= 0.36, p < .001). Fathers of other races are also less likely to take parental leave than White fathers (Exp. b=0.39, p < 0.01), and Hispanic fathers are somewhat less likely than White fathers to take parental leave (b=0.67, p < 0.1). The findings involving race-ethnicity may reflect a more tenuous connection to the labor force among minority fathers and the hesitancy of fathers from minority racial-ethnic groups to temporarily leave a valued employment position. Other research also finds that White fathers have higher rates of leave usage than minority fathers (Nepomnyaschy & Waldfogel, 2007).

Table 2.

Logistic regression of employed fathers taking leave (N=2,233)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attitudes towards fatherhood | 1.22** (0.08) | 1.16* (0.08) | 1.14† (0.08) |

| Importance of financial support | 1.06 (0.17) | 1.13 (0.19) | |

| Importance of direct care | 0.98 (0.19) | 1.00 (0.20) | |

| Involvement by father’s father | 1.26*** (0.08) | 1.18* (0.08) | |

| Cohabiting with mothera | 2.10*** (0.26) | 1.82*** (0.23) | |

| Married to mothera | 4.73*** (0.75) | 3.47*** (0.62) | |

| Child’s mother expects to work | 0.95 (0.16) | ||

| Father has other children | 0.90 (0.11) | ||

| Father’s age | 0.99*** (0.01) | ||

| Blackb | 0.36 (0.07) | ||

| Latino/Hispanicb | 0.67† (0.14) | ||

| Other raceb | 0.39 (0.12) | ||

| Less than high schoolc | 1.01 (0.14) | ||

| Some collegec | 1.17 (0.17) | ||

| College or higherc | 1.18 (0.28) | ||

| Income (logarithmic) | 1.05 (0.07) |

p<0.1

p<0.05

p<0.01

p <0 .001

Notes: Odds ratios are presented. Standard errors are in parentheses.

Reference group is “Non-resident father”

Reference group is “White”

Reference group is “High school”

As shown in Table 3, the predictors of the number of weeks of leave a father takes after his child is born are a bit different than those that predict whether or not a father takes leave at all. More positive attitudes towards fatherhood continue to predict leave usage; a one unit increase in positive attitudes towards fatherhood is associated with taking 0.07 more weeks of leave (p<0.05). The father’s residence with the child’s mother also continues to be associated with more weeks of leave usage. Fathers who cohabit with their children’s mothers take an average of 0.27 more weeks of leave than fathers who live apart from their children’s mothers (p<0.001). Fathers who are married to their children’s mothers take an average of 0.46 more weeks of leave than fathers who live apart from the birth mother (p<0.001). There is evidence that Black men take an average of 0.12 fewer weeks of leave than White men (p<0.05). Results indicate that higher education also has a marginally significant correlation with more leave usage, as men who have some college education take an average of 0.11 more weeks of leave than fathers who have only a high school education (p<0.1), and fathers with at least a college degree take an average of 0.15 more weeks of leave than those with only a high school education (p<0.1). Finally, there is marginally significant evidence that men take an average of 0.10 more weeks of leave when the child’s mother plans to work after giving birth than when the mother does not plan to work (p<0.1).

Table 3.

OLS regression predicting weeks of parental leave taken by employed fathers (N=2,233)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attitudes towards fatherhood | 0.11*** (0.03) | 0.08** (0.03) | 0.07* (0.03) |

| Importance of financial support | 0.04 (0.06) | 0.06 (0.06) | |

| Importance of direct care | -0.02 (0.07) | 0.00 (0.07) | |

| Involvement by father’s father | 0.03 (0.03) | 0.00 (0.03) | |

| Cohabiting with mothera | 0.30*** (0.05) | 0.27*** (0.05) | |

| Married to mothera | 0.54*** (0.06) | 0.46*** (0.07) | |

| Child’s mother expects to work | 0.10† (0.06) | ||

| Father has other children | -0.06 (0.05) | ||

| Father’s age | 0.00 (0.00) | ||

| Blackb | -0.12* (0.06) | ||

| Latino/Hispanicb | 0.04 (0.06) | ||

| Other raceb | 0.07 (0.11) | ||

| Less than high schoolc | -0.02 (0.06) | ||

| Some collegec | 0.11† (0.06) | ||

| College or higherc | 0.15† (0.08) | ||

| Income (logarithmic) | 0.03 (0.03) |

p<0.1

p<0.05

p<0.01

p <0 .001

Notes: b coefficients are presented. Standard errors are in parentheses.

Reference group is “Non-resident father”

Reference group is “White”

Reference group is “High school”

We now turn to predicting father engagement. Table 4 shows six OLS regression models: Models 1 through 3 use the dichotomous leave use variable as the independent variable and Models 4 through 6 use the continuous variable measuring weeks of parental leave use. As shown in Model 3 of Table 4, paternal leave-taking is positively associated with father engagement one year after his child’s birth. Men who take parental leave engage in direct activity with their children an average of 0.48 more days per week than men who do not take leave (p<0.001). As shown in Model 6, each week of parental leave a father takes is associated with an average of 0.17 more days per week of engagement with his child, one year later (p<0.001).

Table 4.

OLS regressions of father engagement one year after birth (N=2,233)

| Leave use

|

Weeks of leave use

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Model | Model | Model | Model 5 | Model 6 | |

| Leave use after child’s birth | 0.73*** (0.08) | 0.49*** (0.08) | 0.48*** (0.09) | |||

| Weeks of leave taken | 0.26*** (0.03) | 0.18*** (0.03) | 0.17*** (0.03) | |||

| Attitudes towards fatherhood | 0.20*** (0.04) | 0.20*** (0.04) | 0.20*** (0.04) | 0.20*** (0.04) | ||

| Importance of providing financial support | 0.21* (0.10) | 0.20* (0.10) | 0.21* (0.10) | 0.20† (0.10) | ||

| Importance of providing direct care | 0.49*** (0.12) | 0.50*** (0.12) | 0.49*** (0.12) | 0.50*** (0.12) | ||

| Involvement by father’s father | 0.08† (0.04) | 0.08* (0.04) | 0.09* (0.04) | 0.09* (0.04) | ||

| Cohabiting with mothera | 0.68*** (0.09) | 0.71*** (0.09) | 0.70*** (0.09) | 0.73*** (0.09) | ||

| Married to mothera | 0.91*** (0.09) | 1.01*** (0.11) | 0.93*** (0.09) | 1.02*** (0.11) | ||

| Child’s mother expects to work | 0.18* (0.09) | 0.16† (0.09) | ||||

| Father has other children | -0.14† (0.07) | -0.14† (0.07) | ||||

| Father’s age | -0.01 (0.01) | -0.01† (0.01) | ||||

| Blackb | 0.04 (0.09) | 0.00 (0.09) | ||||

| Latino/Hispanicb | 0.00 (0.10) | -0.02 (0.10) | ||||

| Other raceb | 0.02 (0.17) | -0.04 (0.17) | ||||

| Less than high schoolc | 0.08 (0.09) | 0.08 (0.09) | ||||

| Some collegec | 0.03 (0.09) | 0.02 (0.09) | ||||

| College or higherc | 0.13 (0.12) | 0.11 (0.12) | ||||

| Income (logarithmic) | 0.00 (0.04) | 0.00 (0.04) | ||||

p<0.1

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

Notes: b coefficients are presented. Standard errors are in parentheses.

Reference group is “Non-resident father”

Reference group is “White”

Reference group is “High school”

It is also notable that indicators of the salience of the status of fatherhood, the salience of specific parenting roles, and relationship commitments with significant others predict father engagement in the models presented in Table 4. For example, in both Models 3 and 6, a man with a very positive attitude towards fatherhood is engaged with his child an average of 0.20 more days per week than a man with a somewhat positive attitude towards fatherhood (p<0.001). Feelings about different roles expected of a father also are positively correlated with engagement. A father who thinks that providing direct care for his child is very important spends an average of 0.50 more days per week engaged with his child than a father who thinks it is somewhat important (p<0.001) and a father who thinks that providing financial support is very important spends an average of 0.20 more days per week with his child than a father who thinks it is somewhat important (p<0.05). Being married to or cohabiting with the child’s mother is positively associated with a father’s engagement. Married fathers are engaged with their children an average of 1.01 more days per week (p<0.001) and cohabiting fathers are engaged with their children an average of 0.71 more days per week (p<0.001), compared to fathers who do not live with their children’s mothers.

Involvement by the father’s father is positively correlated with a father’s engagement. For example, a man who had a somewhat involved father spends an average of 0.08 more days per week engaged with his child than a man with an uninvolved father (p<0.05). Generally, the significant associations hold up in predicting the relationship between more weeks of parental leave use and greater subsequent father-child engagement (see Model 6 of Table 4).

As shown in Table 5, some evidence remains that paternal leave-taking is associated with father engagement when the child is five years old. Fathers who took leave spend an average of 0.25 more days engaged with their children than fathers who did not take leave (p<0.05). The number of weeks of leave taken is positively associated with engagement, with fathers being engaged 0.11 more days per week for every one week of parental leave taken (p<0.05). There remains only limited evidence that fathers’ parenting role identities predict father engagment five years later. Positive attitudes towards fatherhood are positively associated with father engagement (b = 0.18, p< 0.01 in Model 3 and b = 0.17, p<0.01 in Model 6). Cohabiting with and being married to the birth mother are positively associted with father engagment, regardless of which leave variable is in the analysis (b = 0.30, p<0.01 and b = 0.55, p<.001 in Models 3 and 6, respectively).

Table 5.

OLS regressions of father engagement five years after birth (N=1,793)

| Leave use

|

Weeks of leave use

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |

| Leave use after child’s birth | 0.50*** (0.10) | 0.30** (0.10) | 0.25* (0.11) | |||

| Weeks of leave taken | 0.19*** (0.04) | 0.12** (0.04) | 0.11* (0.04) | |||

| Attitudes towards fatherhood | 0.19** (0.05) | 0.18** (0.05) | 0.18** (0.05) | 0.17** (0.05) | ||

| Importance of providing financial support | 0.09 (0.12) | 0.09 (0.12) | 0.08 (0.12) | 0.08 (0.12) | ||

| Importance of providing direct care | 0.18 (0.14) | 0.22 (0.14) | 0.17 (0.14) | 0.21 (0.14) | ||

| Involvement by father’s father | 0.08 (0.05) | 0.06 (0.05) | 0.09† (0.05) | 0.06 (0.05) | ||

| Cohabiting with mothera | 0.34** (0.11) | 0.30** (0.11) | 0.35** (0.11) | 0.30** (0.11) | ||

| Married to mothera | 0.72*** (0.11) | 0.55*** (0.13) | 0.72*** (0.11) | 0.55*** (0.13) | ||

| Child’s mother expects to work | 0.01 (0.11) | -0.01 (0.11) | ||||

| Father has other children | -0.09 (0.09) | -0.09 (0.09) | ||||

| Father’s age | 0.00 (0.01) | 0.00 (0.01) | ||||

| Blackb | -0.29* (0.11) | -0.31** (0.11) | ||||

| Latino/Hispanicb | -0.18 (0.12) | -0.19 (0.12) | ||||

| Other raceb | -0.44* (0.21) | -0.46* (0.21) | ||||

| Less than high schoolc | 0.18† (0.11) | 0.18† (0.11) | ||||

| Some collegec | 0.21† (0.11) | 0.20† (0.11) | ||||

| College or higherc | 0.16 (0.15) | 0.15 (0.15) | ||||

| Income (logarithmic) | 0.03 (0.05) | 0.03 (0.05) | ||||

p<0.1

p<0.05

p<0.01

p <0 .001

Notes: b coefficients are presented. Standard errors are in parentheses.

Reference group is “Non-resident father”

Reference group is “White”

Reference group is “High school”

Discussion

Existing studies on U.S. fathers’ parental leave-taking focus on relatively privileged individuals who are disproportionately married, continously employed, and resident fathers (Nepomnyaschy & Waldfogel, 2007; Hook, 2006). In this study, we provide insight into the parental leave-taking behaviors of a more disadvantaged cohort of fathers. We analyze patterns of leave-taking, their expected predictors, and the extent to which leave-taking is associated with subseqent father engagement.

First, we find that this sample of employed American fathers is likely to use parental leave after the birth of a child (79.71%), but that they are less likely to use leave at all and less likely to use more than one week than fathers studied in other recent research. Instead, our findings are more in line with the use of paternity leave evidenced in research from the 1990s (Han & Waldfogel, 2003; Nepomnyaschy & Waldfogel, 2007). The vast majority of fathers in our sample took one week of leave or less. Furthermore, only 40% of fathers reported taking any paid weeks of leave (including paid vacation and sick-time leave). We find that the most common reason given for why new fathers do not take leave is that they feel there is no need to do so. This explanation may reflect a gendered division of labor, where fathers assume that there is not a need for their contributions to domestic work. Also, it may reflect the negative economic consequences of taking parental leave. There is empirical support for both these interpretations (Hook, 2010; O’Brien, 2009)

Second, fathers’ feelings about the importance of fatherhood, as well as the nature of their relationships with their children’s birth mothers and their own fathers, appear to influence their parental leave decisions. Specifically, men who have more positive attitudes towards being a father, who have fathers who were involved in their lives, and who live with their children’s mothers when the children are born are more likely to take leave. Overall, these findings provide support for the expectation that fathers’ identities shape the leave-taking behaviors of fathers. Specifically, more salient father identities, which are supported by significant others, are likely to encourage fathers to take longer paternity leaves (Ihinger-Tallman et al., 1993; Killewald, 2013; Marsiglio & Roy, 2012).

Finally, there is support for the hypothesis that parental leave use is positively associated with paternal engagement after one- and five-year spans of time. Also, men who take more leave are more engaged with their children after one year and five years. These findings are consistent with emerging evidence that suggests that paternity leave-taking may prompt fathers to become more engaged with their children (Haas & Hwang, 2008; Nepomnyaschy & Waldfogel, 2007; O’Brien, 2009; Pleck, 1993). Not surprisingly, indicators of more salient father identities are also positively associated with father engagement after one and five years. In particular, positive attitudes about fatherhood and residing with the birth mother when children arrive are positively associated with subsequent father engagement.

In sum, despite the lack of support for paid parental leave in the U.S., disadvantaged fathers frequently are taking some leave after the birth of their new children. They generally report very positive attitudes about fatherhood and most often are living with the birth mothers when their new children arrive. Yet they are taking very modest lengths of leave, if they take leave at all. Nonetheless, there is evidence that paternity leave-taking is associated with greater levels of subsequent father engagement.

In light of this evidence, it is worth considering how fathers’ leave-taking may be supported. For example, although only 40% of the fathers in our sample took paid leave, over half of all leave taken was paid. This result is consistent with the broader evidence that fathers take more parental leave when it is universal, father-directed, and offers generous benefits (O’Brien, 2009). Relatedly, it seems that encouraging fathers in the development of positive attitudes about fatherhood and nurturing relationship commitments that foster fathering activities may enhance fathers’ involvement with their children through paternity leave-taking and subsequent father engagement.

There are several limitations to this study. We would have liked to have known more about how many people were offered parental leave, and specifically paid parental leave. We did not include paid weeks taken in our regression analyses because we think that paid weeks taken in the U.S. is largely a function of institional support and often conditional on having a more privileged occupation (Nepomnyaschy & Waldfogel, 2007; O’Brien, 2009). Future work should seek to understand better the work environments and institutional supports that are offered to fathers who may be considering their leave options. In addition, attitudes about fatherhood and the importance of specific fathering roles may be overwhelmingly positive, because the fathers were asked these questions very soon after the birth of their children. Future work should continue to trace evidence of father identities over longer periods of time. Furthermore, although our research is complementary to previous work because of its focus on nonmarital births in urban areas, it is also important for future research to continue to consider leave-taking experiences in a variety of different family situations.

Finally, it is important to note that selection effects may be driving our results. For example, it is possible that men who become more engaged fathers are simply more inclined to take parental leave than those who become less engaged. They may be particularly family-oriented, have more egalitarian relationships with the birth mothers, or disproportionately work in careers that allow for more opportunites to take parental leave and engage with their children. In future research, more rigorous analytical designs and statistical techniques to account for selection effects should be implemented in order to tease out selection effects more clearly and to provide stronger evidence of potential causal relationships between father identities, leave-taking, and subsequent father engagement.

Relatedly, attrition in the FFCWS is a problem, and the fathers who are re-interviewed at Wave 2 generally may be more privileged and/or dedicated fathers who are the most likely to have taken parental leave. We did explore differences between fathers who dropped out of the study and fathers who remained in the study. From Wave 1 to Wave 2, we found that fathers who attrit are more likely to be Black or Hispanic, have fewer children, be older, have less than a high school education, and be nonresident fathers. From Wave 2 to Wave 4, we found that those fathers who attrit are more likely to be younger, to have less education, and to be nonresident fathers (not shown). To assess the potential influence of these attrition patterns on our results, we constructed a variable, lambda, that was formed from logistic regression equations that predicted the likelihood of attrition. We then included lambda as a control variable in each of our regression models. This procedure did not change our results and suggests that attrition did not affect our findings.

Despite these limitations, this study remains important because little is known about how American fathers, and particularly disadvantaged fathers, respond to the arrival of a new child and balance work and family responsibilities. Overall, this study suggests that parental leave use by disadvantaged fathers is relatively common, but short in duration. Most fathers do not seem to have access to paid parental leave. The salience of father identities and relationship commitments especially appear to encourage fathers to take parental leave. Furthermore, there is evidence that paternal leave-taking is positively associated with paternal engagement one year, and even five years, after a new child’s birth. Perhaps more inclusive and father-directed paid parental leave policies at the federal level of the U.S. government may help families care for newborn children, encourage gender equity, and help nurture father-child relationships. In fact, paternity leave might especially benefit disadvantaged fathers because of their greater likelihood of having experienced, and subsequently becoming, disengaged fathers (Edin & Nelson, 2013; Marsiglio & Roy, 2012; McLanahan & Percheski, 2008).

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers R01HD36916, R01HD39135, and R01HD40421, as well as a consortium of private foundations. Brianne Pragg’s research was supported by funding from NICHD to the Population Research Institute at The Pennsylvania State University for Population Research Infrastructure (R24 HD41025) and Family Demography Training (T-32HD007514). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The authors wish to thank Dr. Valarie King, Dr. Michelle L. Frisco, and anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on previous drafts.

Footnotes

The employed fathers are selectively different than the unemployed fathers. The men who were unemployed at the time of their child’s birth are more likely to be Black or Other in race-ethnicity, have less than a high school education, be non-resident fathers, have lower household incomes, and report less positive attitudes about fatherhood. Thus, our analysis of leave-taking does not fully capture the experiences of these underrepresented groups. Notably, these groups are also less likely to have access to paid leave, since they are not employed. Nonetheless, over 83% of the fathers that are interviewed at baseline were employed and approximately 92% of the fathers surveyed at Wave 2 had been employed within the last year.

The employed fathers who dropped out of the study prior to the Wave 2 follow-up interviews were more likely to be Black or Hispanic, have fewer children, be older, have less than a high school education, and be nonresident fathers. As described in the Discussion section, we attempted to adjust for this trend in our anaylses with a Heckman procedure.

The fathers who dropped out of the study between Waves 2-4 were younger, less educated, and more likely to be nonresident fathers. As described in the Discussion section, we attempted to adjust for this trend with a Heckman procedure in our analysis.

Contributor Information

Brianne Pragg, Pennsylvania State University.

Chris Knoester, Ohio State University.

References

- Baude A. Public policy and changing family patterns of Sweden 1930-1977. In: Lipman-Blumen J, Bernard J, editors. Sex Roles and Social Policy: A Complex Social Science Equation. 145-176. Beverly Hills, California: Sage; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Berggren HM. US family-leave policy: the legacy of ‘separate spheres’. International Journal of Social Welfare. 2008;(17):312–323. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi SM, Robinson JP, Milkie MA. The changing rhythm of American family Life. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Brewster KL, Padavic I. Change in gender-ideology, 1977–1996: The contributions of intracohort change and population turnover. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2000;62(2):477–487. [Google Scholar]

- Bygren M, Duvander A-Z. Parents’ workplace situation and fathers’ parental leave use. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2006;68(2):363–372. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman JM, Franiuk R. Perceptions of mothers and fathers who take temporary work leave. Sex Roles. 2011;(64):311–323. [Google Scholar]

- Craig L, Mullan K. How mothers and fathers share childcare: A cross-national time-use comparison. American Sociological Review. 2011;76(6):834–861. [Google Scholar]

- Edin K, Nelson TJ. Doing the best I can: Fatherhood in the inner city. University of California Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Haas L, Allard K, Hwang P. The impact of organizational culture on men’s use of parental leave in Sweden. Community, Work & Family. 2002;5(3):319–342. [Google Scholar]

- Haas L, Hwang CP. Company culture and men’s usage of family leave benefits in Sweden. Family Relations. 1995;44(1):28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Haas L, Hwang CP. The impact of taking parental leave on fathers’s participation in childcare and relationships with children: Lessons from Sweden. Community, Work & Family. 2008;11(1):85–104. [Google Scholar]

- Han WJ, Waldfogel J. Parental leave: The impact of recent legislation on parents’ leave taking. Demography. 2003;40(1):191–200. doi: 10.1353/dem.2003.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman J, Earle A, Hayes J. The work, family, and equity index: Where does the United States stand globally? Boston: Project on Global Working Families; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hook JL. Care in context: Men’s unpaid work in 20 countries, 1965-2003. American Sociological Review. 2006;71:639–660. [Google Scholar]

- Hook JL. Gender inequality in the welfare state: Sex segregation in housework, 1965-2003. American Journal of Sociology. 2010;115:1480–1523. doi: 10.1086/651384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde JS, Essex MJ, Horton F. Fathers and parental leave attitudes and experiences. Journal of Family Issues. 1993;14(4):616–638. [Google Scholar]

- Ihinger-Tallman M, Pasley K, Buehler C. Developing a middle-range theory of father involvement postdivorce. Journal of Family Issues. 1993;14:550–571. [Google Scholar]

- Killewald A. A reconsideration of the fatherhood premium: Marriage, coresidence, biology, and fathers’ wages. American Sociological Review. 2013;78(1):96–116. [Google Scholar]

- Knoester C, Petts RJ, Eggebeen DJ. Commitments to fathering and the well-being and social participation of new, disadvantaged fathers. Journal of Marriage & Family. 2007;69(4):991–1004. [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan S, Percheski C. Family structure and the reproduction of inequalities. Annual Review of Sociology. 2008;34:257–276. [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan S, Sandefur G. Growing up with a single parent: What hurts, what helps. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglio W, Roy K. Nurturing Dads: Social initiatives for contemporary fatherhood. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- National Partnership for Women & Families. Washington, D.C., United States of America: 2012. Expecting better: A state-by-state analysis of laws that help new parents. (2) Retrieved from: http://go.nationalpartnership.org/site/DocServer/Expecting_Better_Report.pdf?docID=10301. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson TJ. Low-income fathers. Annual Review of Sociology. 2004;30:427–451. [Google Scholar]

- Nepomnyaschy L, Waldfogel J. Paternity leave and fathers’ involvement with their young children: Evidence from the American Ecls-B. Community, Work and Family. 2007;10(4):427–453. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien M. Fathers, parental leave policies, and infant quality of life: International perspectives and policy impact. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2009;624(1):190–213. [Google Scholar]

- Pleck JH. Are “family supportive” employer policies relevant to men? In: Hood JC, editor. Men, work, and family. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 217–237. [Google Scholar]

- Smock PJ, Greenland FR. Diversity in pathways to parenthood: Patterns, implications, and emerging research directions. Journal of Marriage & Family. 2010;72(3):576–593. [Google Scholar]

- Stryker S. Identity salience and role performance: The relevance of symbolic interaction theory for family research. Journal of Marriage & Family. 1968;30(4):558–564. [Google Scholar]

- Stryker S, Burke PJ. The past, present, and future of an identity theory. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2000;63(4, Special Millenium Issue on the State of Sociological Social Psychology):284–297. [Google Scholar]

- Sundström M, Duvander A-ZE. Gender division of childcare and the sharing of parental leave among new parents in Sweden. European Sociological Review. 2002;18(4):433–447. [Google Scholar]

- Swedish Institute. Facts about Sweden: Gender Equality. 2011 Retrieved from www.sweden.se: http://www.sweden.se/upload/Sweden_se/english/factsheets/SI/SI_FS8_Gender%20equality/FS8-Gender-equality-in-Sweden-low-resolution.pdf.

- Tanaka S, Waldfogel J. Effects of parental leave and work hours on fathers’ involvement with their babies. Community, Work & Family. 2007;10(4):409–426. [Google Scholar]

- Waldfogel J. International policies toward parental leave and child care. The Future of Children. 2001;11(1):98–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]