DNA retrieved from a tooth discovered deep in Denisova Cave allows us to assign it to the Denisovans, a group of archaic hominins.

Abstract

The presence of Neandertals in Europe and Western Eurasia before the arrival of anatomically modern humans is well supported by archaeological and paleontological data. In contrast, fossil evidence for Denisovans, a sister group of Neandertals recently identified on the basis of DNA sequences, is limited to three specimens, all of which originate from Denisova Cave in the Altai Mountains (Siberia, Russia). We report the retrieval of DNA from a deciduous lower second molar (Denisova 2), discovered in a deep stratigraphic layer in Denisova Cave, and show that this tooth comes from a female Denisovan individual. On the basis of the number of “missing substitutions” in the mitochondrial DNA determined from the specimen, we find that Denisova 2 is substantially older than two of the other Denisovans, reinforcing the view that Denisovans were likely to have been present in the vicinity of Denisova Cave over an extended time period. We show that the level of nuclear DNA sequence diversity found among Denisovans is within the lower range of that of present-day human populations.

INTRODUCTION

Genetic analyses of the remains of archaic hominins have yielded insights into their population history and admixture with each other and with modern humans [for example, (1–12)]. DNA retrieved from fossils also allows their attribution to a hominin group in the absence of clear archaeological context or informative morphology [for example, (13–15)]. One example is a hominin phalanx (Denisova 3) excavated in Denisova Cave (Altai, Russia) in 2008. Although its mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) was found to fall outside the range of variation of both present-day humans and Neandertals (16), nuclear sequences retrieved from the specimen showed that it came from a member of a previously unknown sister group of Neandertals, thenceforth named “Denisovans” (2). The population split time between Neandertals and Denisovans has been estimated to be at least 190 thousand years ago (ka) and perhaps as much as 470 ka (7).

While Neandertals inhabited Europe and West Asia, Denisovans, who have been identified only from Denisova Cave to date (2, 3, 16, 17), inhabited Asia (2) where they overlapped geographically with Neandertals in the Altai region and possibly elsewhere. The two groups must have interacted, as analyses of their genomes have shown that Denisovans interbred with Neandertals and with an unknown archaic hominin group that diverged earlier from the human lineage (7). Denisovans, or a group related to them, have also contributed genetically to present-day populations in Southeast Asian islands and Oceania and at lower levels to populations across mainland Asia and the Americas (2, 3, 7, 18–22). Denisovan admixture has contributed to several traits in present-day humans (20, 23, 24), including, for example, the adaption of Tibetan populations to life at high altitude (25).

In addition to Denisova 3, two permanent molars (Denisova 4 and Denisova 8) have been identified as originating from Denisovans on the basis of DNA sequence data (2, 17); and mtDNA fragments of the Denisovan type were identified in sediments deposited at Denisova Cave (26). Here, we present analyses of DNA sequences retrieved from a tooth (Denisova 2) that, on the basis of the stratigraphy of the site, is one of the oldest hominin remains discovered at Denisova Cave (27, 28).

RESULTS

The Denisova 2 specimen

A worn deciduous molar (figs. S1 and S2) was discovered in 1984 in layer 22.1 of the Main Gallery of Denisova Cave and was initially described as a right lower first deciduous molar (dm1) (29). However, Shpakova and Derevianko (30) believed that the tooth was more likely a lower second deciduous molar (dm2), and we concur with their opinion on the basis of the lack of a tuberculum molare and the large size. The crown of the tooth is almost completely worn away, and only a thin rim of enamel is preserved buccally, mesially, and lingually. The only feature of crown morphology preserved is a small remnant of the buccal groove. The roots are mostly resorbed, with only short stumps remaining mesiobuccally and mesiolingually. The exposed pulp cavity shows five diverticles entering the crown. The resorption of the roots and the fact that the specimen exfoliated naturally indicate an age equivalent to about 10 to 12 years in modern humans (for details, see section S1). The strong wear makes most morphological comparisons impossible. However, the cervical mesiodistal and buccolingual diameters are very large, falling outside of the range of variation seen in modern humans and in the range of Neandertals (table S1 and fig. S3).

DNA extraction and sequencing

We extracted DNA (31) from ~10 mg of powder removed from the Denisova 2 specimen (fig. S2). One aliquot of the extract was used to produce a single-stranded DNA library, as previously described (32, 33). Another aliquot was converted into a single-stranded DNA library using a modified version of a protocol that enriches the library for DNA molecules carrying uracil residues (34), which result from deamination of cytosine bases in ancient DNA (35–37). This protocol (“mini-U-selection”) enriches for uracils only at the 3′ ends of fragments, but it requires fewer reaction steps and allows for a simpler library preparation than the original method (34). Out of a total of 701 million and 604 million DNA fragments sequenced from the two libraries, 0.06 and 0.46% of all sequences could be mapped to the human genome and exhibited a cytosine (C)–to–thymine (T) substitution at the first or last alignment position (table S2). These substitutions, especially when they occur close to the ends of sequences, are highly indicative of the presence of uracils, which are read as thymines by DNA polymerases (36). The percentage of fragments carrying C-to-T substitutions at the unselected 5′ ends was 9.4% in the former library and 7.3% in the library enriched for uracils. These percentages were 11.1 and 53.8% for the 3′ ends of fragments, respectively (table S3 and figs. S4 and S5), suggesting that authentic ancient DNA is present in both libraries (section S2).

Mitochondrial DNA

We used oligonucleotide probes matching a modern human mtDNA sequence to enrich for mtDNA fragments from the library that was not selected for uracil residues (4, 38). Initial inspection of the sequences suggested that the library contained a mixture of contaminating present-day human mtDNA and endogenous sequences that are more similar to a Denisovan mtDNA than to modern human or Neandertal mtDNAs (section S3 and table S4). We therefore aligned the sequences from the mitochondrial capture as well as DNA fragments sequenced without enrichment from all libraries to the Denisova 3 mtDNA genome (16) and identified 86,788 unique mtDNA fragments (table S2).

To mitigate the influence of contamination by present-day human mtDNA (section S2), we filtered the 21,537 fragments (table S2) that carried C-to-T differences relative to the Denisova 3 mtDNA genome near the start or end position of sequence alignments (first three or last three positions for sequences from the standard library and first two or last two positions for sequences from the mini-U-selection protocol) (39). Using these fragments, we reconstructed the Denisova 2 mtDNA genome with an average mtDNA coverage of 51-fold (fig. S6). When a given position was required to be covered by at least three fragments and when at least two-thirds of fragments overlapping a position were required to carry an identical base (39), all but 14 positions in the mtDNA genome were resolved (section S3).

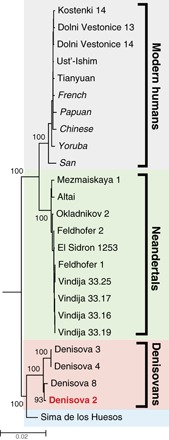

A maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree shows that the mtDNA of Denisova 2 clusters with the three previously determined Denisovan mtDNAs, to the exclusion of Neandertal and modern human mtDNAs (Fig. 1). It carries 29 nucleotide differences from Denisova 8, 70 nucleotide differences to Denisova 4, and 72 nucleotide differences to Denisova 3 (table S5).

Fig. 1. Maximum likelihood tree relating the Denisova 2 mtDNA to other ancient and present-day mtDNAs.

The Denisova 2 mtDNA (in red) clusters with the three previously determined Denisovan mtDNAs, to the exclusion of Neandertals and modern humans. Present-day human mtDNA sequences are noted in italics. The tree was rooted using a chimpanzee mtDNA sequence (not shown). Support for each branch is based on 500 bootstrap replications. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site. Accession codes for the comparative data and the geographical origins of ancient individuals are presented in table S5.

Relative mtDNA dating

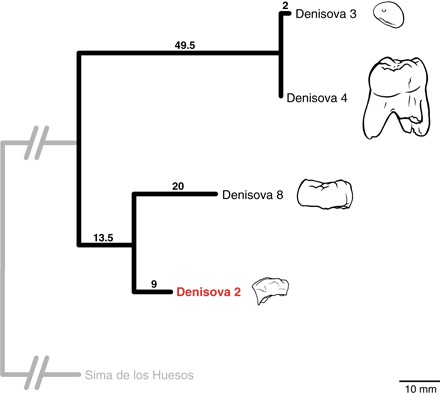

The tree in Fig. 2 shows the relationships of the four currently known Denisovan mtDNAs using the Middle Pleistocene hominin mtDNA from Sima de los Huesos (39) as an outgroup. A total of 22.5, 33.5, 49.5, and 51.5 substitutions are inferred by parsimony (fractions reflect ambiguous character reconstructions) to have accumulated between the common ancestor and the mtDNAs of Denisova 2, 8, 4, and 3, respectively. In agreement with previous observations (17), Denisova 8 appears to be substantially older than Denisova 3 and 4. The mtDNA of Denisova 2 is more closely related to that of Denisova 8 than to the other two mtDNAs. Notably, 20 substitutions are inferred to have accumulated on the terminal edge leading to Denisova 8, whereas only 9 substitutions are estimated to have done so on the terminal edge leading to Denisova 2, indicating that Denisova 2 is older than Denisova 8.

Fig. 2. Phylogenetic tree relating the Denisova 2 mtDNA to other Denisovan mtDNA sequences.

The number of substitutions on each branch was inferred by maximum parsimony, and the Middle Pleistocene mtDNA from Sima de los Huesos was used as an outgroup. The schematic representations of the specimens are drawn to scale, shown in the lower right corner.

Using a mutation rate of 2.53 × 10−8 substitutions per site per year (95% highest posterior density, 1.76 × 10−8 to 3.23 × 10−8) (6), we estimate that the Denisova 2 individual is between 54.2 and 99.4 thousand years (ky) older than the Denisova 3 individual and between 20.6 and 37.7 ky older than the Denisova 8 individual, whereas the Denisova 3 and 4 individuals were roughly contemporaneous (between 3.7- and 6.9-ky difference). Although the absolute time estimates are dependent on whether the mutation rate of Denisovan mtDNA differs from that of modern human mtDNA, the difference in the number of substitutions between these individuals indicates that Denisova 2 is likely to be older than Denisova 8 and substantially older than Denisova 3 and 4.

Nuclear DNA and sexing

For nuclear DNA analyses, DNA sequences from the Denisova 2 specimen were aligned to the human reference genome. We determined the sex of the Denisova 2 individual by counting the number of putatively deaminated DNA fragments that map to the X chromosome and the autosomes. The ratio of sequence coverage per base between the X chromosome and the autosomes is 1.06, indicating that Denisova 2 was a female (fig. S7).

To minimize the effect of present-day human contamination (section S2 and table S3), we retained only sequences carrying a C-to-T substitution to the human reference genome at their first or last position (39), leaving 1.08 million DNA sequences (table S2) spanning 47 Mb of the human genome for further analysis.

Attribution to a hominin group

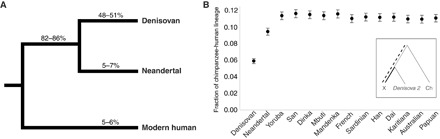

Genetic, archaeological, and anthropological evidence indicate that Denisovans, Neandertals, and anatomically modern humans were present in Denisova Cave (2, 3, 7, 16, 17, 28, 40, 41). We computed the proportion of DNA fragments from the Denisova 2 specimen that share derived alleles specific to each branch in a phylogenetic tree relating the high-coverage genomes of a Denisovan (3), a Neandertal (7), and a present-day human from Africa (7). A total of 69,315 fragments overlapped phylogenetically informative positions at which a randomly drawn allele from at least one of these high-coverage genomes is derived (12). Of fragments that overlap positions where both the Denisovan and the Neandertal genomes are derived, 84% (1888 of 2246) share the derived allele. Of fragments that overlap positions where only the Denisovan genome is derived, 49% (2051 of 4160) carry the Denisovan-like allele, whereas the corresponding values for the sharing of Neandertal- and modern human–specific alleles are 6% (252 of 4231) and 5% (307 of 5924), respectively (Fig. 3A). We thus conclude that the Denisova 2 specimen originated from a Denisovan individual.

Fig. 3. Attribution of Denisova 2 to a hominin group.

(A) For each branch of a phylogenetic tree relating the high-coverage genomes of a Denisovan, a Neandertal, and a present-day human from Africa, the 95% binomial CIs of the proportion of DNA fragments from the Denisova 2 specimen that share a derived allele with that branch are given. (B) The fraction of substitutions inferred to have occurred after the split from the Denisova 2 genome along the branch from the human-chimpanzee (Ch) ancestral sequences to the high-coverage genomes of a Denisovan, a Neandertal, and 12 present-day humans (“X” in the schematic phylogenetic tree shown in the inset) is given. Error bars denote 95% CIs.

The corresponding values for two previously sequenced Denisovan teeth, Denisova 4 and Denisova 8 (17), are 92 and 93% of sequences sharing derived alleles with the Neandertal-Denisovan branch, 72 and 60% with the Denisovan branch, 5% with the Neandertal branch, and 2% with the modern human branch, respectively (fig. S8). Thus, Denisova 2 shares fewer derived alleles with the high-coverage Denisova 3 genome than with the other two Denisovan genomes (χ2 = 7.6257, P = 0.003 and χ2 = 43.015, P = 2.717 × 10−11 for Denisova 4 and 8, respectively), showing that Denisova 2 is more distantly related to Denisova 3 than to Denisova 4 and Denisova 8.

Denisovan DNA sequence diversity

To gauge the average sequence divergence between the DNA fragments sequenced from Denisova 2 and the high-coverage Denisova 3 genome, we calculated how many of the substitutions on the lineage leading from the human-chimpanzee ancestor to Denisova 3 have occurred after the split from the Denisova 2 genome, that is, the fraction of derived sites that Denisova 2 does not share with Denisova 3 (1, 3, 7). This value is 5.9% [95% confidence interval (CI), 5.6 to 6.2%]. In comparison, it is 9.4% (95% CI, 9.0 to 9.9%) for derived alleles not shared with the Neandertal genome and 10.9 to 11.6% for 12 present-day human genomes (Fig. 3B and table S6). The corresponding values for Denisova 4 and Denisova 8 relative to the high-coverage Denisova 3 genome are 4.3% (95% CI, 2.3 to 6.7%) and 4.3% (95% CI, 4.0 to 4.7%), respectively. Excluding two Neandertal specimens yielding very little genetic data (0.1 Mb or less), the lower and upper boundaries of the 95% CIs for the fraction of substitutions occurring on the branch leading to the high-coverage Neandertal genome after the split from four low-coverage Neandertal genomes range between 2.6 and 4.2% (table S6). Comparable estimates calculated among 12 humans from various parts of the world range between 5.1 and 9.2% (table S7). Thus, the estimated sequence diversity among Denisovans, which all originate from a single cave, is comparable to that of Neandertals sampled in several locations and within the lower range of the diversity of present-day human populations worldwide.

DISCUSSION

The Denisova 2 specimen adds a deciduous molar to the meager Denisovan fossil record, which so far included one distal manual phalanx (Denisova 3) (2, 3, 16) and two permanent molars (Denisova 4 and 8) (2, 17).

The fact that only 47 Mb of nuclear sequences could be retrieved from ~10 mg of tooth powder removed from Denisova 2 precludes many analyses. For example, subsampling DNA sequences from Denisova 3 shows that the power to detect gene flow from Denisovans into modern humans is limited (section S4, table S8, and fig. S9). Sequence errors in the low-coverage data also hinder our ability to ask whether the gene flow from an unknown archaic hominin into Denisovans detected in the Denisova 3 genome (7) also affected the ancestors of Denisova 2 (section S4 and fig. S10).

Denisova 2 was found in layer 22.1 of the Main Gallery of Denisova Cave, which has been dated to between 128 and 227 ka by radiothermoluminescence (42, 43). Denisova 3 was found in layer 11.2 of the East Gallery (16). Its age has been estimated to be between 48 and 60 ka on the basis of “missing substitutions” in its nuclear genome relative to present-day humans (7). This is consistent with the direct dating of associated finds, which are beyond the range of radiocarbon dating (2). Using nucleotide substitutions inferred to have occurred in the mtDNAs of Denisova 2 and Denisova 3 after their divergence from a common ancestor (Fig. 2), we estimate that the Denisova 2 individual lived approximately 50,000 to 100,000 years earlier than Denisova 3. Even given the uncertainty about the substitution rate in Denisovans, these results suggest that Denisova 2 lived at least 100 ka, making it one of the oldest hominin remains discovered in Central Asia to date. Beyond reinforcing the idea that both Neandertals and Denisovans lived in the cave or its vicinity (7, 17), our findings indicate that Denisovans were present over an extended period in the Altai region, where the two archaic groups may have met and mixed.

The seemingly great difference in age between the Denisovan individuals is congruent with previous indications that Denisovans inhabited the Altai region over tens of thousands of years (17). Despite the wide age range of Denisovan individuals, their DNA sequence diversity is in the lower range of diversity among contemporaneous humans today. This low estimate of diversity among the Denisovans is consistent with the longtime small population size inferred from the high-coverage Denisova 3 genome (3). We note that age differences between the high-coverage archaic individuals and present-day modern humans can affect the comparability of our diversity estimates. However, this effect is expected to be minor, given that these branch length differences are far shorter than the common branch leading back to the human-chimpanzee ancestor. Moreover, as all four Denisovan individuals originate from a single location, it is possible that they represent an isolated population and that the genetic diversity of Denisovans across their entire geographical range was greater than that seen in these geographically restricted samples. Additional Denisovans from other locations are needed to more comprehensively gauge their genetic diversity across space and time.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Morphological analysis

The Denisova 2 specimen was discovered in the Main Gallery of Denisova Cave (Russia), in sector 4, square B-8, in layer 22.1, the deepest horizon of this gallery. Description of the specimen is based on the original material as well as later analyses of casts and photographs. The specimens used for comparison were as follows: prehistoric and historic Central and Southern European (Natural History Museum Vienna and Department of History and Methods for the Conservation of Cultural Heritage, University of Bologna), prehistoric Siberian (Institute of Archaeology, Siberian Branch, Russian Academy of Sciences, Novosibirsk), historical Khoisan individuals (Department of Anthropology, University of Vienna), Neandertals (Okladnikov 1; Roc de Marsal 1; Krapina D62, D63, D64, D65, D66, and D68; Scladina; Archi 1; Abri Suard S14-5, S37, and S42; Couvin; Engis 2; and La Ferrassie 8), and Upper Paleolithic modern humans (Strashnaya 1b; Lagar Velho; and Pavlov 7, 8, 9, and 10). Okladnikov 1, Strashnaya 1b, Denisova 2, and most of the recent comparative sample were measured using a Paleo-Tech dental caliper, whereas the measurements on the rest of the Neandertal sample as well as the recent Southern European subsample (housed in Bologna) were taken in Avizo 8 (FEI Visualization Sciences Group) on surface models based on micro–computed tomography (μCT) scans. Cervical measurements of Lagar Velho are from Hillson and Trinkaus (44), and those of Pavlov 7 to 10 are from Sládek et al. (45).

DNA extraction and library preparation

Following the removal of surface material, 10.2 mg of powder was sampled from the apical end of a root of Denisova 2 using a dentistry drill. DNA was extracted using a silica-based protocol (31) modified as in the study by Korlević et al. (33) and eluted in 50 μl of TET [10 mM tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 0.05% Tween 20 (pH 8.0)]. Fifteen microliters of the DNA extract (E2084) was converted into a DNA library (A4881), as previously described (32), except that the primer extension and blunt-end repair reactions were performed in one step (33). The number of DNA molecules in the library was estimated by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (Stratagene MX3005P, Agilent Technologies), as previously described (32). The library was barcoded with two unique indexes (46) using 1 μM primer concentrations (33) and AccuPrime Pfx DNA polymerase (Life Technologies) (47). Amplification products were purified with the MinElute PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen) and eluted in 30 μl of TE [10 mM tris-HCl and 1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0)]. After quantification using a NanoDrop ND-1000 (NanoDrop Technologies) photospectrometer, 1 μg of the amplified library (A4891) was enriched for human mitochondrial sequences, as previously described (4, 38). The captured library (A4928) had a final volume of 20 μl in EB [10 mM tris-HCl (pH 8.0)].

A 29-μl aliquot of the same extract was converted into a DNA library enriched for DNA molecules carrying a uracil (U) at their 3′ end using a modified version of a published protocol (34). This mini-U-selection protocol was carried out as follows: (i) The single-stranded adapter oligonucleotide (CL78) was decontaminated by treatment with Escherichia coli exonuclease I (33). (ii) Pretreatment by uracil excision and DNA cleavage at abasic sites was carried out using 1 μl of USER Enzyme mix (1 U/μl) (New England BioLabs) (34). (iii) Ligation of the first adapter and immobilization on beads were performed as described in steps 3 to 11 of the protocol by Gansauge and Meyer (32). (iv) Primer extension and blunt-end repair were carried out in one reaction (33). (v) Ligation of the second adapter was done as in steps 20 to 23 in the study by Gansauge and Meyer (32). (vi) Uracil excision, which releases library molecules with uracils close to the 3′ end of DNA fragments, was performed by incubating the beads in an excision reaction mix of 1 μl of USER Enzyme mix (1 U/μl) (New England BioLabs) and 49 μl of EBT [10 mM tris-HCl and 0.05% Tween 20 (pH 8.0)] for 30 min at 37°C. (vii) Recovery of the residual library molecules was carried out as in the study by Gansauge and Meyer (34). The number of DNA molecules in the two library fractions was assessed by digital droplet PCR (Bio-Rad QX200) using an EvaGreen (Bio-Rad) assay with primers IS7 and IS8 (48, 49). The uracil-enriched library was split into four aliquots (A4944 to A4947), each of which was barcoded with a unique combination of two indexes, amplified and purified as above.

Before sequencing, 2 μl of each library was amplified in one PCR cycle using Herculase II Fusion DNA polymerase (Agilent) (47) with primers IS5 and IS6 (48) to remove heteroduplices. The libraries were purified using the MinElute PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen), and their concentration was assessed using a DNA 1000 chip (Bioanalyzer 2100, Agilent) (3). A DNA extraction blank and one library preparation blank were carried along each experiment.

Sequencing and processing of sequence data

Shotgun sequencing of library A4891 was first performed on 12% of an Illumina HiSeq lane and then sequenced deeper on four HiSeq lanes. Libraries A4944 to A4947 were sequenced on 90% of a MiSeq (Illumina) platform and then sequenced together on four HiSeq lanes. The captured library A4928 was sequenced on 12% of a MiSeq lane. Sequencing was performed using paired-end runs with double-index configuration (46).

Base calling was carried out using freeIbis (50) and Bustard (Illumina) for HiSeq and MiSeq runs, respectively. Adapter sequences were removed and overlapping forward and reverse reads were merged using leeHom (51). Sequences that did not perfectly match the expected barcode combinations were discarded. For each library, sequences originating from different sequencing runs were combined using SAMtools (52).

Mapping to a reference genome was performed using Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA) (53), with parameters “-n 0.01 -o 2 -l 16500” (3). To recover nuclear DNA fragments, sequences originating from shotgun sequencing were aligned to the human reference genome [UCSC (University of California, Santa Cruz) version hg19]. For mtDNA analyses, sequences from all libraries were aligned to the Denisovan mitochondrial reference sequence [National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) reference NC_013993.1] (16). Because BWA cannot use circularized references, the mitochondrial reference sequence was altered by copying the first 1000 bases to its end (39). After mapping, PCR duplicates were removed by collapsing sequences starting and ending at identical coordinates using bam-rmdup (https://bitbucket.org/ustenzel/biohazard).

Analyses of mtDNA

Filtering

Analyses of the mtDNA data were restricted to sequences between 30 and 75 base pairs (bp) long, which present C-to-T substitutions to the reference genome adjacent to their ends (39). Sequences from single-stranded DNA libraries (A4891 and A4928) were retained if they carried C-to-T substitutions at the first three or last three terminal positions, whereas for the libraries enriched for uracil-containing DNA fragments (A4944 to A4947), sequences with apparent C-to-T substitutions at their first two or last two positions were retained. Thymines at the abovementioned positions where the reference base is a cytosine were converted to N’s.

Reconstructing the Denisova 2 mtDNA sequence

The mtDNA of Denisova 2 was called by a majority vote using the “mpileup” command of SAMtools (52). A base was called only if a position was covered by at least three fragments, of which at least two-thirds carried an identical base (39).

Phylogenetic analysis

The Denisova 2 mtDNA was aligned to the mtDNAs of 3 Denisovans (2, 16, 17), 5 present-day humans from a variety of geographical origins (54), 5 ancient modern humans (4, 6, 55, 56), 10 Neandertals (7, 34, 57–59), 1 Middle Pleistocene hominin (39), and 1 chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes, NC_001643) (60) using MAFFT (61). NCBI accession codes for the comparative sequence data and the geographical origin of the individuals are presented in table S5. A maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree with 500 bootstrap replications (62) was reconstructed in MEGA6 (63) using the Hasegawa-Kishino-Yano substitution model (64) with gamma distribution and allowing for invariable sites (HKY + G + I), as determined by jModelTest2 (65, 66). The numbers of pairwise base differences observed between mtDNAs were determined using MEGA6 (63).

Molecular dating

The Denisova 2 mitochondrial genome was aligned to the other three Denisovan mtDNA sequences (2, 16, 17) and to the mtDNA of a Middle Pleistocene hominin from Sima de los Huesos (Spain) (39) using MAFFT (61). The number of substitutions occurring on each branch since the split from the most recent common ancestor of all Denisovan mtDNAs was inferred by maximum parsimony in the R package “phangorn,” using an accelerated transformation (“ACCTRAN”) algorithm to optimize ambiguous character reconstructions (67). The difference in the number of mutations inferred to have occurred on each branch was translated to differences in time based on a mitochondrial mutation rate for the modern human lineage of 2.53 × 10−8 substitutions per site per year (95% highest posterior density, 1.76 × 10−8 to 3.23 × 10−8) (6).

Analyses of nuclear DNA

Filtering

Given the low amount of nuclear DNA retrieved from Denisova 2, nuclear DNA fragments were filtered using a scheme stricter than the one used for mtDNA analyses. Fragments shorter than 35 bp or with a mapping quality lower than 30 (Phred scale) were discarded, and an alignability track excluding nonunique sequences was applied (7). Because present-day contaminating DNA sequences may be more prevalent among longer DNA fragments (55), fragments longer than 75 bp were discarded (fig. S4). Nuclear analyses were restricted to sequences carrying a C-to-T substitution relative to the reference genome at one of their ends (39), as these nucleotide differences are the result of damage occurring over time and are thus indicative of ancient DNA (36, 55, 68). The base quality of terminal thymines was reduced to 2 regardless of the base in the reference genome (7), and subsequent processing was limited to bases with a quality higher than 30. Comparative data from previously sequenced low-coverage Denisovan (17) and Neandertal (1, 7) genomes were processed as above, except that the Neandertal sequences were filtered for the presence of guanine (G)–to–adenine (A) substitutions at the 3′ ends of fragments since the data were generated using a double-stranded DNA library preparation protocol (48).

Lineage attribution

To attribute the Denisova 2 specimen to a hominin group, the state of sequences overlapping sites at which the genomes of a Denisovan (3), a Neandertal (7), and a present-day modern human from Africa (HGDP00982) (7) differ from those of other great apes (chimpanzee, bonobo, gorilla, and orangutan) and the rhesus macaque was investigated. The proportion of sequences that share the derived state with each of the hominin branches was calculated with 95% binomial CIs (12). A one-sided two-sample proportions test implemented in R (69) was used to test for significant differences in allele sharing with the high-coverage Denisovan genome among the three low-coverage Denisovans.

Relative DNA sequence diversity

We estimated the divergence of the DNA fragments sequenced from Denisova 2 along the lineage leading from the ancestor shared with the chimpanzee and the high-coverage genomes of a Denisovan (3), a Neandertal (7), or a modern human [panel B from the study by Prüfer et al. (7)]. We calculated how many of the substitutions inferred to have occurred from the human-chimpanzee ancestral sequences to the high-coverage genomes occurred after the split from the Denisova 2 genome, that is, the fraction of derived sites that Denisova 2 does not share with each high-coverage genome (1, 7). CIs were calculated by jackknife resampling in 5-Mb windows along the high-coverage genomes. For the high-coverage genomes, the homozygous genotype was selected at homozygous sites, and a random allele was selected at heterozygous sites, whereas for the Denisova 2 data, a random allele was selected in the rare cases when more than one DNA fragment covered a site.

For comparative purposes, we repeated this calculation while replacing the Denisova 2 data with low-coverage sequence data from two other Denisovans (Denisova 4 and Denisova 8) (17) and six Neandertals (Feldhofer 1, Mezmaiskaya 1, El Sidron 1253, Vindija 33.16, Vindija 33.25, and Vindija 33.26) (1, 7). We reprocessed these sequences using the same filtering scheme that we applied to the Denisova 2 data. For data generated with the single-stranded DNA library preparation protocol (Denisova 4 and 8), a terminal C-to-T substitution to the reference genome at either end was required. For data generated with a double-stranded DNA library preparation scheme (Feldhofer 1, Mezmaiskaya 1, El Sidron 1253, Vindija 33.16, Vindija 33.25, and Vindija 33.26), putative deamination was identified as a C-to-T substitution at the 5′ end of fragments or a G-to-A substitution at their 3′ end (32, 36, 48). The base quality of terminal thymines or adenines was reduced to 2, and subsequent processing was limited to bases with a quality higher than 30.

To compute estimates of diversity among present-day humans that would be comparable to our estimates for the archaic genomes, we subsampled each of the 12 present-day high-coverage human genomes (7) to retain only positions covered by at least 1 of the low-coverage archaic genomes in our data set. The percentage of inferred substitutions occurring on the lineage to a high-coverage genome that are not shared with the subsampled DNA sequences was computed as described above.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank B. Höber, B. Nickel, and A. Weihmann for help in the laboratory; U. Stenzel for raw data processing; M. Hajdinjak, A. Hübner, F. Mafessoni, M. Petr, and F. Romagné for help in analyzing the data; P. Korlević for graphics; and H. Temming for μCT scans. We are grateful to A. Andrés, M. Dannemann, C. de Filippo, F.-M. Key, M. Mednikova, F. Racimo, D. Reich, M. Slatkin, U. Stenzel, and M. Stiller for helpful comments. Funding: This work was supported by the Max Planck Society, the Max Planck Foundation (grant 31-12LMP Pääbo to S.P.), the European Research Council (grant agreement no. 694707 to S.P.), the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (IDG 430-2016-00590 to B.V.), and the Russian Science Foundation (project no. 14-50-00036 to M.V.S. and A.P.D.). Author contributions: V.S., B.V., M.M., and S.P. designed the study; V.S. performed the experiments; V.S., G.R., S.S., J.K., K.P., M.M., and S.P. analyzed the genetic data; B.V., S.B., and J.-J.H. analyzed the morphological data; M.-T.G. and M.M. developed the novel laboratory procedure described; M.V.S. and A.P.D. provided the specimen and archaeological expertise; and V.S., B.V., and S.P. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: Sequence data generated from Denisova 2 are deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive (PRJEB20653). The mtDNA sequence of Denisova 2 is available in GenBank (KX663333). All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/3/7/e1700186/DC1

section S1. The Denisova 2 specimen

section S2. Authenticating the DNA sequences

section S3. The mtDNA sequence of Denisova 2

section S4. Nuclear DNA sequences from Denisova 2

fig. S1. The Denisova 2 specimen.

fig. S2. The Denisova 2 specimen.

fig. S3. Biplot of cervical buccolingual (BL) and mesiodistal (MD) diameters.

fig. S4. Characteristic of DNA fragments from the two libraries prepared from the Denisova 2 specimen, per size bin.

fig. S5. Frequency of nucleotide substitutions in the Denisova 2 sequences.

fig. S6. Reconstructing the Denisova 2 mitochondrial genome.

fig. S7. Sex determination of Denisova 2.

fig. S8. Lineage attribution of two other low-coverage Denisovan individuals.

fig. S9. Testing our power to detect the sharing of derived alleles between Denisovans and present-day humans.

fig. S10. Ancestral allele counts in Denisovan and Neandertal sequences at sites that are fixed or nearly fixed for a derived allele in present-day humans.

table S1. Metric comparisons of cervical and maximum mesiodistal and buccolingual diameters of Denisova 2, Neandertals, and recent and Upper Paleolithic modern humans.

table S2. Characteristics of the DNA libraries prepared from Denisova 2.

table S3. Frequencies of terminal C-to-T substitutions to the human reference genome.

table S4. Percentage and number of sequences matching the derived state of mitochondrial genomes from three hominin groups.

table S5. Number of base differences between the Denisova 2 mtDNA and other mtDNAs.

table S6. Estimates of DNA divergence between low-coverage archaic genomes and the high-coverage genomes of a Denisovan, a Neandertal, and 12 present-day humans.

table S7. Estimates of DNA divergence between subsampled genomes and the high-coverage genomes of a Denisovan, a Neandertal, and 12 present-day humans.

table S8. Sharing of derived alleles between Denisova 2 and present-day humans.

table S9. Denisova-specific nonsynonymous coding changes corroborated by sequences from Denisova 2, 4, or 8.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Green R. E., Krause J., Briggs A. W., Maricic T., Stenzel U., Kircher M., Patterson N., Li H., Zhai W., Fritz M. H.-Y., Hansen N. F., Durand E. Y., Malaspinas A.-S., Jensen J. D., Marques-Bonet T., Alkan C., Prüfer K., Meyer M., Burbano H. A., Good J. M., Schultz R., Aximu-Petri A., Butthof A., Hober B., Höffner B., Siegemund M., Weihmann A., Nusbaum C., Lander E. S., Russ C., Novod N., Affourtit J., Egholm M., Verna C., Rudan P., Brajkovic D., Kucan Ž., Gušic I., Doronichev V. B., Golovanova L. V., Lalueza-Fox C., de la Rasilla M., Fortea J., Rosas A., Schmitz R. W., Johnson P. L. F., Eichler E. E., Falush D., Birney E., Mullikin J. C., Slatkin M., Nielsen R., Kelso J., Lachmann M., Reich D., Pääbo S., A draft sequence of the Neandertal genome. Science 328, 710–722 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reich D., Green R. E., Kircher M., Krause J., Patterson N., Durand E. Y., Viola B., Briggs A. W., Stenzel U., Johnson P. L. F., Maricic T., Good J. M., Marques-Bonet T., Alkan C., Fu Q., Mallick S., Li H., Meyer M., Eichler E. E., Stoneking M., Richards M., Talamo S., Shunkov M. V., Derevianko A. P., Hublin J.-J., Kelso J., Slatkin M., Pääbo S., Genetic history of an archaic hominin group from Denisova Cave in Siberia. Nature 468, 1053–1060 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meyer M., Kircher M., Gansauge M.-T., Li H., Racimo F., Mallick S., Schraiber J. G., Jay F., Prüfer K., de Filippo C., Sudmant P. H., Alkan C., Fu Q., Do R., Rohland N., Tandon A., Siebauer M., Green R. E., Bryc K., Briggs A. W., Stenzel U., Dabney J., Shendure J., Kitzman J., Hammer M. F., Shunkov M. V., Derevianko A. P., Patterson N., Andrés A. M., Eichler E. E., Slatkin M., Reich D., Kelso J., Pääbo S., A high-coverage genome sequence from an archaic Denisovan individual. Science 338, 222–226 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fu Q., Meyer M., Gao X., Stenzel U., Burbano H. A., Kelso J., Pääbo S., DNA analysis of an early modern human from Tianyuan Cave, China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 2223–2227 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castellano S., Parra G., Sánchez-Quinto F. A., Racimo F., Kuhlwilm M., Kircher M., Sawyer S., Fu Q., Heinze A., Nickel B., Dabney J., Siebauer M., White L., Burbano H. A., Renaud G., Stenzel U., Lalueza-Fox C., de la Rasilla M., Rosas A., Rudan P., Brajković D., Kucan Ž., Gušic I., Shunkov M. V., Derevianko A. P., Viola B., Meyer M., Kelso J., Andrés A. M., Pääbo S., Patterns of coding variation in the complete exomes of three Neandertals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 6666–6671 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fu Q., Li H., Moorjani P., Jay F., Slepchenko S. M., Bondarev A. A., Johnson P. L. F., Aximu-Petri A., Prüfer K., de Filippo C., Meyer M., Zwyns N., Salazar-García D. C., Kuzmin Y. V., Keates S. G., Kosintsev P. A., Razhev D. I., Richards M. P., Peristov N. V., Lachmann M., Douka K., Higham T. F. G., Slatkin M., Hublin J.-J., Reich D., Kelso J., Viola T. B., Pääbo S., Genome sequence of a 45,000-year-old modern human from western Siberia. Nature 514, 445–449 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prüfer K., Racimo F., Patterson N., Jay F., Sankararaman S., Sawyer S., Heinze A., Renaud G., Sudmant P. H., de Filippo C., Li H., Mallick S., Dannemann M., Fu Q., Kircher M., Kuhlwilm M., Lachmann M., Meyer M., Ongyerth M., Siebauer M., Theunert C., Tandon A., Moorjani P., Pickrell J., Mullikin J. C., Vohr S. H., Green R. E., Hellmann I., Johnson P. L. F., Blanche H., Cann H., Kitzman J. O., Shendure J., Eichler E. E., Lein E. S., Bakken T. E., Golovanova L. V., Doronichev V. B., Shunkov M. V., Derevianko A. P., Viola B., Slatkin M., Reich D., Kelso J., Pääbo S., The complete genome sequence of a Neanderthal from the Altai Mountains. Nature 505, 43–49 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raghavan M., Skoglund P., Graf K. E., Metspalu M., Albrechtsen A., Moltke I., Rasmussen S., Stafford T. W. Jr., Orlando L., Metspalu E., Karmin M., Tambets K., Rootsi S., Mägi R., Campos P. F., Balanovska E., Balanovsky O., Khusnutdinova E., Litvinov S., Osipova L. P., Fedorova S. A., Voevoda M. I., DeGiorgio M., Sicheritz-Ponten T., Brunak S., Demeshchenko S., Kivisild T., Villems R., Nielsen R., Jakobsson M., Willerslev E., Upper Palaeolithic Siberian genome reveals dual ancestry of Native Americans. Nature 505, 87–91 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seguin-Orlando A., Korneliussen T. S., Sikora M., Malaspinas A.-S., Manica A., Moltke I., Albrechtsen A., Ko A., Margaryan A., Moiseyev V., Goebel T., Westaway M., Lambert D., Khartanovich V., Wall J. D., Nigst P. R., Foley R. A., Lahr M. M., Nielsen R., Orlando L., Willerslev E., Genomic structure in Europeans dating back at least 36,200 years. Science 346, 1113–1118 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fu Q., Hajdinjak M., Moldovan O. T., Constantin S., Mallick S., Skoglund P., Patterson N., Rohland N., Lazaridis I., Nickel B., Viola B., Prüfer K., Meyer M., Kelso J., Reich D., Pääbo S., An early modern human from Romania with a recent Neanderthal ancestor. Nature 524, 216–219 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fu Q., Posth C., Hajdinjak M., Petr M., Mallick S., Fernandes D., Furtwängler A., Haak W., Meyer M., Mittnik A., Nickel B., Peltzer A., Rohland N., Slon V., Talamo S., Lazaridis I., Lipson M., Mathieson I., Schiffels S., Skoglund P., Derevianko A. P., Drozdov N., Slavinsky V., Tsybankov A., Cremonesi R. G., Mallegni F., Gély B., Vacca E., Morales M. R. G., Straus L. G., Neugebauer-Maresch C., Teschler-Nicola M., Constantin S., Moldovan O. T., Benazzi S., Peresani M., Coppola D., Lari M., Ricci S., Ronchitelli A., Valentin F., Thevenet C., Wehrberger K., Grigorescu D., Rougier H., Crevecoeur I., Flas D., Semal P., Mannino M. A., Cupillard C., Bocherens H., Conard N. J., Harvati K., Moiseyev V., Drucker D. G., Svoboda J., Richards M. P., Caramelli D., Pinhasi R., Kelso J., Patterson N., Krause J., Pääbo S., Reich D., The genetic history of Ice Age Europe. Nature 534, 200–205 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meyer M., Arsuaga J.-L., Nagel S., Aximu-Petri A., Martínez I., Gracia A., Bermúdez de Castro J. M., Carbonell E., Kelso J., Prüfer K., Pääbo S., Nuclear DNA sequences from the Middle Pleistocene Sima de los Huesos hominins. Nature 531, 504–507 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benazzi S., Peresani M., Talamo S., Fu Q. M., Mannino M. A., Richards M. P., Hublin J.-J., A reassessment of the presumed Neandertal remains from San Bernardino Cave, Italy. J. Hum. Evol. 66, 89–94 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benazzi S., Slon V., Talamo S., Negrino F., Peresani M., Bailey S. E., Sawyer S., Panetta D., Vicino G., Starnini E., Mannino M. A., Salvadori P. A., Meyer M., Pääbo S., Hublin J.-J., The makers of the Protoaurignacian and implications for Neandertal extinction. Science 348, 793–796 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown S., Higham T. F., Slon V., Pääbo S., Meyer M., Douka K., Brock F., Comeskey D., Procopio N., Shunkov M. V., Derevianko A., Buckley M., Identification of a new hominin bone from Denisova Cave, Siberia using collagen fingerprinting and mitochondrial DNA analysis. Sci. Rep. 6, 23559 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krause J., Fu Q., Good J. M., Viola B., Shunkov M. V., Derevianko A. P., Pääbo S., The complete mitochondrial DNA genome of an unknown hominin from southern Siberia. Nature 464, 894–897 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sawyer S., Renaud G., Viola B., Hublin J.-J., Gansauge M.-T., Shunkov M. V., Derevianko A., Prüfer K., Kelso J., Pääbo S., Nuclear and mitochondrial DNA sequences from two Denisovan individuals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 15696–15700 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reich D., Patterson N., Kircher M., Delfin F., Nandineni M. R., Pugach I., Ko A. M.-S., Ko Y.-C., Jinam T. A., Phipps M. E., Saitou N., Wollstein A., Kayser M., Pääbo S., Stoneking M., Denisova admixture and the first modern human dispersals into Southeast Asia and Oceania. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 89, 516–528 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qin P., Stoneking M., Denisovan ancestry in East Eurasian and Native American populations. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 2665–2674 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vernot B., Tucci S., Kelso J., Schraiber J. G., Wolf A. B., Gittelman R. M., Dannemann M., Grote S., McCoy R. C., Norton H., Scheinfeldt L. B., Merriwether D. A., Koki G., Friedlaender J. S., Wakefield J., Pääbo S., Akey J. M., Excavating Neandertal and Denisovan DNA from the genomes of Melanesian individuals. Science 352, 235–239 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sankararaman S., Mallick S., Patterson N., Reich D., The combined landscape of Denisovan and Neanderthal ancestry in present-day humans. Curr. Biol. 26, 1241–1247 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Skoglund P., Jakobsson M., Archaic human ancestry in East Asia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 18301–18306 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dannemann M., Andrés A. M., Kelso J., Introgression of Neandertal- and Denisovan-like haplotypes contributes to adaptive variation in human toll-like receptors. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 98, 22–33 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Racimo F., Marnetto D., Huerta-Sánchez E., Signatures of archaic adaptive introgression in present-day human populations. Mol. Biol. Evol. 34, 296–317 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huerta-Sánchez E., Jin X., Asan, Bianba Z., Peter B. M., Vinckenbosch N., Liang Y., Yi X., He M., Somel M., Ni P., Wang B., Ou X., Huasang, Luosang J., Cuo Z. X. P., Li K., Gao G., Yin Y., Wang W., Zhang X., Xu X., Yang H., Li Y., Wang J., Wang J., Nielsen R., Altitude adaptation in Tibetans caused by introgression of Denisovan-like DNA. Nature 512, 194–197 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Slon V., Hopfe C., Weiß C. L., Mafessoni F., de la Rasilla M., Lalueza-Fox C., Rosas A., Soressi M., Knul M. V., Miller R., Stewart J. R., Derevianko A. P., Jacobs Z., Li B., Roberts R. G., Shunkov M. V., de Lumley H., Perrenoud C., Gušic I., Kucan Ž., Rudan P., Aximu-Petri A., Essel E., Nagel S., Nickel B., Schmidt A., Prüfer K., Kelso J., Burbano H. A., Pääbo S., Meyer M., Neandertal and Denisovan DNA from Pleistocene sediments. Science 356, 605–608 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.A. P. Derevianko, Perehod ot Srednego k Verhnemu Paleolitu i Problema Formirovaniya Homo sapiens sapiens v Vostochnoi, Central’noi i Severnoi Azii (Izd. IAE SO RAN, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 28.A. P. Derevianko, Recent Discoveries in the Altai: Issues on the Evolution of Homo sapiens (Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography SB RAS Press, 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 29.C. G. Turner, in Chronostratigraphy of the Paleolithic in North Central, East Asia and America, A. P. Derevianko, Ed. (Institute of History, Philology and Philosophy, Siberian Branch of the USSR Academy of Sciences, 1990), pp. 239–243. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shpakova E. G., Derevianko A. P., The interpretation of odontological features of Pleistocene human remains from the Altai. Archaeol. Ethnol. Anthropol. Eurasia 1, 125–138 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dabney J., Knapp M., Glocke I., Gansauge M.-T., Weihmann A., Nickel B., Valdiosera C., Garcia N., Pääbo S., Arsuaga J.-L., Meyer M., Complete mitochondrial genome sequence of a Middle Pleistocene cave bear reconstructed from ultrashort DNA fragments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 15758–15763 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gansauge M.-T., Meyer M., Single-stranded DNA library preparation for the sequencing of ancient or damaged DNA. Nat. Protoc. 8, 737–748 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Korlević P., Gerber T., Gansauge M.-T., Hajdinjak M., Nagel S., Aximu-Petri A., Meyer M., Reducing microbial and human contamination in DNA extractions from ancient bones and teeth. Biotechniques 59, 87–93 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gansauge M.-T., Meyer M., Selective enrichment of damaged DNA molecules for ancient genome sequencing. Genome Res. 24, 1543–1549 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hofreiter M., Jaenicke V., Serre D., von Haeseler A., Pääbo S., DNA sequences from multiple amplifications reveal artifacts induced by cytosine deamination in ancient DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, 4793–4799 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Briggs A. W., Stenzel U., Johnson P. L. F., Green R. E., Kelso J., Prüfer K., Meyer M., Krause J., Ronan M. T., Lachmann M., Pääbo S., Patterns of damage in genomic DNA sequences from a Neandertal. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 14616–14621 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brotherton P., Endicott P., Sanchez J. J., Beaumont M., Barnett R., Austin J., Cooper A., Novel high-resolution characterization of ancient DNA reveals C > U-type base modification events as the sole cause of post mortem miscoding lesions. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, 5717–5728 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maricic T., Whitten M., Pääbo S., Multiplexed DNA sequence capture of mitochondrial genomes using PCR products. PLOS ONE 5, e14004 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meyer M., Fu Q., Aximu-Petri A., Glocke I., Nickel B., Arsuaga J.-L., Martínez I., Gracia A., Bermúdez de Castro J. M., Carbonell E., Pääbo S., A mitochondrial genome sequence of a hominin from Sima de los Huesos. Nature 505, 403–406 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mednikova M. B., A Proximal pedal phalanx of a Paleolithic hominin from Denisova Cave, Altai. Archaeol. Ethnol. Anthropol. Eurasia 39, 129–138 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mednikova M. B., Distal phalanx of the hand of Homo from Denisova Cave Stratum 12: A tentative description. Archaeol. Ethnol. Anthropol. Eurasia 41, 146–155 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 42.A. Derevianko, The Paleolithic of Siberia: New Discoveries and Interpretations (University of Illinois Press, 1998). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Derevianko A., Laukhin S. A., The first Middle Pleistocene dates of the Gorno Altai Palaeolithic. Dokl. Akad. Nauk 325, 497–501 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 44.S. W. Hillson, E. Trinkaus, Comparative dental crown metrics, in Portrait of the Artist as a Child: The Gravettian Human Skeleton from the Abrigo do Lagar Velho and its Archeological Context, J. Zilhao, E. Trinkaus, Eds. (Instituto Portugues de Arqueologia, 2002), pp. 356–364. [Google Scholar]

- 45.V. Sládek, E. Trinkaus, S. Hillson, T. W. Holliday, J. Svoboda, People of the Pavlovian: Skeletal Catalogue and Osteometrics of the Gravettian Fossil Hominids om Dolní Vestonice and Pavlov (Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Institute of Archaeology, 2000). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kircher M., Sawyer S., Meyer M., Double indexing overcomes inaccuracies in multiplex sequencing on the Illumina platform. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, e3 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dabney J., Meyer M., Length and GC-biases during sequencing library amplification: A comparison of various polymerase-buffer systems with ancient and modern DNA sequencing libraries. Biotechniques 52, 87–94 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meyer M., Kircher M., Illumina sequencing library preparation for highly multiplexed target capture and sequencing. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2010, pdb.prot5448 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Slon V., Glocke I., Barkai R., Gopher A., Hershkovitz I., Meyer M., Mammalian mitochondrial capture, a tool for rapid screening of DNA preservation in faunal and undiagnostic remains, and its application to Middle Pleistocene specimens from Qesem Cave (Israel). Quatern. Int. 398, 210–218 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Renaud G., Kircher M., Stenzel U., Kelso J., freeIbis: An efficient basecaller with calibrated quality scores for Illumina sequencers. Bioinformatics 29, 1208–1209 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Renaud G., Stenzel U., Kelso J., leeHom: Adaptor trimming and merging for Illumina sequencing reads. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, e141 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li H., Handsaker B., Wysoker A., Fennell T., Ruan J., Homer N., Marth G., Abecasis G., Durbin R.; 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup, The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li H., Durbin R., Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 26, 589–595 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ingman M., Kaessmann H., Pääbo S., Gyllensten U., Mitochondrial genome variation and the origin of modern humans. Nature 408, 708–713 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Krause J., Briggs A. W., Kircher M., Maricic T., Zwyns N., Derevianko A., Pääbo S., A Complete mtDNA genome of an early modern human from Kostenki, Russia. Curr. Biol. 20, 231–236 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fu Q., Mittnik A., Johnson P. L. F., Bos K., Lari M., Bollongino R., Sun C., Giemsch L., Schmitz R., Burger J., Ronchitelli A. M., Martini F., Cremonesi R. G., Svoboda J., Bauer P., Caramelli D., Castellano S., Reich D., Pääbo S., Krause J., A revised timescale for human evolution based on ancient mitochondrial genomes. Curr. Biol. 23, 553–559 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Green R. E., Malaspinas A. S., Krause J., Briggs A. W., Johnson P. L., Uhler C., Meyer M., Good J. M., Maricic T., Stenzel U., Prufer K., Siebauer M., Burbano H. A., Ronan M., Rothberg J. M., Egholm M., Rudan P., Brajkovic D., Kucan Z., Gusic I., Wikstrom M., Laakkonen L., Kelso J., Slatkin M., Pääbo S., A complete Neandertal mitochondrial genome sequence determined by high-throughput sequencing. Cell 134, 416–426 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Briggs A. W., Good J. M., Green R. E., Krause J., Maricic T., Stenzel U., Lalueza-Fox C., Rudan P., Brajković D., Kućan Ž., Gušic I., Schmitz R., Doronichev V. B., Golovanova L. V., de la Rasilla M., Fortea J., Rosas A., Pääbo S., Targeted retrieval and analysis of five Neandertal mtDNA genomes. Science 325, 318–321 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Skoglund P., Northoff B. H., Shunkov M. V., Derevianko A. P., Pääbo S., Krause J., Jakobsson M., Separating endogenous ancient DNA from modern day contamination in a Siberian Neandertal. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 2229–2234 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Horai S., Hayasaka K., Kondo R., Tsugane K., Takahata N., Recent African origin of modern humans revealed by complete sequences of hominoid mitochondrial DNAs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 532–536 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Katoh K., Standley D. M., MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 772–780 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Felsenstein J., Confidence limits on phylogenies: An approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39, 783–791 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tamura K., Stecher G., Peterson D., Filipski A., Kumar S., MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 2725–2729 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hasegawa M., Kishino H., Yano T., Dating of the human-ape splitting by a molecular clock of mitochondrial DNA. J. Mol. Evol. 22, 160–174 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Darriba D., Taboada G. L., Doallo R., Posada D., jModelTest 2: More models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat. Methods 9, 772 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Guindon S., Gascuel O., A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst. Biol. 52, 696–704 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schliep K. P., phangorn: Phylogenetic analysis in R. Bioinformatics 27, 592–593 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sawyer S., Krause J., Guschanski K., Savolainen V., Pääbo S., Temporal patterns of nucleotide misincorporations and DNA fragmentation in ancient DNA. PLOS ONE 7, e34131 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.R. Development Core Team, R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shpakova E. G., Paleolithic human dental remains from Siberia. Archaeol. Anthropol. Ethnol. Eurasia 4, 64–76 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bailey S. E., Benazzi S., Buti L., Hublin J.-J., Allometry, merism, and tooth shape of the lower second deciduous molar and first permanent molar. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 159, 93–105 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Benazzi S., Fornai C., Buti L., Toussaint M., Mallegni F., Ricci S., Gruppioni G., Weber G. W., Condemi S., Ronchitelli A., Cervical and crown outline analysis of worn Neanderthal and modern human lower second deciduous molars. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 149, 537–546 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hillson S., Fitzgerald C., Flinn H., Alternative dental measurements: Proposals and relationships with other measurements. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 126, 413–426 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Moorrees C. F. A., Fanning E. A., Hunt E. E. Jr., Formation and resorption of three deciduous teeth in children. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 21, 205–213 (1963). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nanda R. S., Root resorption of deciduous teeth in Indian children. Arch. Oral Biol. 14, 1021–1030 (1969). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.D. H. Ubelaker, Manuals on Archaeology: Human Skeletal Remains (Taraxacum, ed. 2, 1978). [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kloss-Brandstätter A., Pacher D., Schönherr S., Weissensteiner H., Binna R., Specht G., Kronenberg F., HaploGrep: A fast and reliable algorithm for automatic classification of mitochondrial DNA haplogroups. Hum. Mutat. 32, 25–32 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.van Oven M., Kayser M., Updated comprehensive phylogenetic tree of global human mitochondrial DNA variation. Hum. Mutat. 30, E386–E394 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Loogvali E.-L., Roostalu U., Malyarchuk B. A., Derenko M. V., Kivisild T., Metspalu E., Tambets K., Reidla M., Tolk H.-V., Parik J., Pennarun E., Laos S., Lunkina A., Golubenko M., Barać L., Pericic M., Balanovsky O. P., Gusar V., Khusnutdinova E. K., Stepanov V., Puzyrev V., Rudan P., Balanovska E. V., Grechanina E., Richard C., Moisan J. P., Chaventre A., Anagnou N. P., Pappa K. I., Michalodimitrakis E. N., Claustres M., Gölge M., Mikerezi I., Usanga E., Villems R., Disuniting uniformity: A pied cladistic canvas of mtDNA haplogroup H in Eurasia. Mol. Biol. Evol. 21, 2012–2021 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Patterson N., Moorjani P., Luo Y., Mallick S., Rohland N., Zhan Y., Genschoreck T., Webster T., Reich D., Ancient admixture in human history. Genetics 192, 1065–1093 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.1000 Genomes Project Consortium, Abecasis G. R., Auton A., Brooks L. D., DePristo M. A., Durbin R. M., Handsaker R. E., Kang H. M., Marth G. T., McVean G. A., An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature 491, 56–65 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kent W. J., Sugnet C. W., Furey T. S., Roskin K. M., Pringle T. H., Zahler A. M., Haussler D., The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res. 12, 996–1006 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/3/7/e1700186/DC1

section S1. The Denisova 2 specimen

section S2. Authenticating the DNA sequences

section S3. The mtDNA sequence of Denisova 2

section S4. Nuclear DNA sequences from Denisova 2

fig. S1. The Denisova 2 specimen.

fig. S2. The Denisova 2 specimen.

fig. S3. Biplot of cervical buccolingual (BL) and mesiodistal (MD) diameters.

fig. S4. Characteristic of DNA fragments from the two libraries prepared from the Denisova 2 specimen, per size bin.

fig. S5. Frequency of nucleotide substitutions in the Denisova 2 sequences.

fig. S6. Reconstructing the Denisova 2 mitochondrial genome.

fig. S7. Sex determination of Denisova 2.

fig. S8. Lineage attribution of two other low-coverage Denisovan individuals.

fig. S9. Testing our power to detect the sharing of derived alleles between Denisovans and present-day humans.

fig. S10. Ancestral allele counts in Denisovan and Neandertal sequences at sites that are fixed or nearly fixed for a derived allele in present-day humans.

table S1. Metric comparisons of cervical and maximum mesiodistal and buccolingual diameters of Denisova 2, Neandertals, and recent and Upper Paleolithic modern humans.

table S2. Characteristics of the DNA libraries prepared from Denisova 2.

table S3. Frequencies of terminal C-to-T substitutions to the human reference genome.

table S4. Percentage and number of sequences matching the derived state of mitochondrial genomes from three hominin groups.

table S5. Number of base differences between the Denisova 2 mtDNA and other mtDNAs.

table S6. Estimates of DNA divergence between low-coverage archaic genomes and the high-coverage genomes of a Denisovan, a Neandertal, and 12 present-day humans.

table S7. Estimates of DNA divergence between subsampled genomes and the high-coverage genomes of a Denisovan, a Neandertal, and 12 present-day humans.

table S8. Sharing of derived alleles between Denisova 2 and present-day humans.

table S9. Denisova-specific nonsynonymous coding changes corroborated by sequences from Denisova 2, 4, or 8.