Abstract

Here we report the discovery through activation tagging and subsequent characterization of the BIG LEAF (BL) gene from poplar. In poplar, BL regulates leaf size via positively affecting cell proliferation. Up and downregulation of the gene led to increased and decreased leaf size, respectively, and these phenotypes corresponded to increased and decreased cell numbers. BL function encompasses the early stages of leaf development as native BL expression was specific to the shoot apical meristem and leaf primordia and was absent from the later stages of leaf development and other organs. Consistently, BL downregulation reduced leaf size at the earliest stages of leaf development. Ectopic expression in mature leaves resulted in continued growth most probably via sustained cell proliferation and thus the increased leaf size. In contrast to the positive effect on leaf growth, ectopic BL expression in stems interfered with and significantly reduced stem thickening, suggesting that BL is a highly specific activator of growth. In addition, stem cuttings from BL overexpressing plants developed roots, whereas the wild type was difficult to root, demonstrating that BL is a positive regulator of adventitious rooting. Large transcriptomic changes in plants that overexpressed BL indicated that BL may have a broad integrative role, encompassing many genes linked to organ growth. We conclude that BL plays a fundamental role in control of leaf size and thus may be a useful tool for modifying plant biomass productivity and adventitious rooting.

Introduction

In plants, final organ size is determined by the coordinated cell proliferation and expansion. Variation in leaf morphology due to environmental or genetic factors is highly correlated with leaf-cell numbers and, as a result, cell proliferation appears to be the main control point in the determination of final organ size [1]. However, manipulation of critical regulators of cell-cycle progression in mutant and transgenic plants has had little effect on organ size, primarily due to compensatory changes in cell expansion and/or differentiation [1, 2]. This suggests that regulatory mechanisms coordinating cell proliferation and growth determine final organ size. Genetic dissection in the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana and other herbaceous plants has revealed some insights into the mechanism and the factors involved. They include a variety of hormonal, metabolic, and regulatory cascades; transcription factors of various families, and their corresponding microRNAs; as well as signaling molecules with incompletely defined biochemical function [1, 2]. Final leaf size is influenced by several strictly regulated and coordinated processes, such as: number of cells in the primordia, rate of cell division, window of cell proliferation, and timing and rate of cell expansion [3].

A major regulator of organ size via regulation of cell proliferation in A. thaliana is the AINTEGUMENTA (ANT) gene [4–6]. Initially, ANT was shown to be involved in the regulation of flower development, but later work revealed its role in controlling the size of leaves and other organs (e.g., flower, siliques, roots, and seeds). AINTEGUMENTA is an AP2-domain transcription factor that belongs to a small subfamily of eight members, known as ANT-like (AIL), some of which have been functionally characterized [7]. The Populus trichocarpa ortholog of AIL, PtaAIL1, is involved in regulation of adventitious root development and bud phenology [8, 9]. AINTEGUMENTA is one of several genes, including CURLY LEAF (CLF), APETALA 2 (AP2), LEUNIG (LUG), and STERILE APETALA (SAP), which negatively regulate expression of AGAMOUS (AG), in the first two whorls of developing flowers, as well as in vegetative organs [10–12]. Loss of function of these genes leads to small and/or curled leaves, with cells prematurely exiting the mitotic cycle [13–15]. In contrast to loss-of-function lesions, gain-of-function mutations in genes like ANT have the opposite effect: an increase in leaf size [4]. Recently, SAP was identified as F-box protein [16] involved in PEAPOD (PPD) protein degradation. PEAPOD1 and PEAPOD2 are negative regulators of leaf meristemoid cell proliferation in A. thaliana [17].

Here we show that a Populus ortholog of SAP influences leaf size, adventitious rooting, and the onset and extent of secondary growth.

Materials and methods

Plant material and statistical analyses

All experiments were performed using the Populus tremula x P. alba (genotype INRA 717-IB4). The plants were maintained in vitro on media as previously described [18]. For all analyses, three independent transgenic events (lines) were used. All growth parameters were taken on fully developed, healthy, greenhouse-grown plants. All statistical analyses were performed using Daniel’s XL Toolbox [19] for MS Excel (Microsoft). The number (n, individual plants measured from one growth experiment) of independent biological replicates for each analysis is given in the figures’ legends. In all cases the data are from three independent transgenic lines, except for the blD mutant and INRA 717-IB4 where data was collected for 3–5 plants per genotype. One-way analysis of variance was used to determine significance. Student’s t-test or Tukey’s multiple-comparison test was used to determine differences among the mean values.

Generation of activation tagging population and genomic positioning of the tag

Generation of an activation-tagging population was previously described [20]. Recovery of fragments flanking the insertion site and positioning of activation tag in the Populus genome (Phytozome.net) was performed as previously described [20].

Binary vector generation and plant transformation

For recapitulation and production of BL over-expressing plants (BL-oe), the BL open reading frame (GenBank ID KR698934) was amplified using gene-specific primers with attached XhoI (5’) and XbaI (3’) restriction-site tails. The amplified fragment was cloned into the pCR4-TOPO vector using the TOPO-TA cloning kit (Invitrogen) and sequence-verified. The BL gene was inserted into the shuttle vector pART7 between the cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) 35S promoter (P35S) and the octopine synthase terminator (OCSt) using the XhoI-XbaI sites flanking the BL fragment. The P35S-BL-OCSt cassette was sub-cloned into the NotI site of the pART27 binary vector [21] before being transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101/pMK90 [22]. For the generation of the over-expression (oe) green fluorescence protein (GFP) and β-glucuronidase (GUS) fusion constructs, BL-GFP-oe and BL-GUS-oe, the BL open reading frame was amplified using gene-specific primers with attached attB Gateway sequence tail, as previously described [23] and cloned in binary vectors pMDC83 and pMDC140 [24], respectively. For generation of RNA interference (RNAi) lines (BL-i), the vector pK7GWIWG2(II) was used [25]. For generation of the BL-SRDX, a translational fusion with 12 amino acids of repressor domain SRDX [26] were incorporated in attB2 primer for the GATEWAY cloning (primer BL-R(-stop)DN) and cloned in binary vector pK7WG2 Karimi [25]. To produce lines containing BL-GFP-oe, BL-GUS-oe, BL-SRDX, and BL-i, A. tumefaciens strain AGL1 [27] was used for transformation. Generation of transgenic plants was performed as previously described [18, 20]. Transgenesis was verified via the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for the presence of the transgene using the following primer pairs: p2735CI645/Fp2735CI645R (for BL-oe), GFPf/GFPr (for BL-GFP-oe), GUSf/GUSr (for BL-GUS-oe), and NPTf/NPTr (for BL-I and BL-SRDX). The sequences of all primers used are shown in S1 Table.

RNA extraction and gene expression analyses

Extraction of total RNA, cDNA synthesis, and transcript quantification were performed as previously described [23, 28]. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed using a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and the primers shown in S1 Table. Reaction mixtures contained Maxima SYBR Green qPCR master mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 0.2 μM of each primer, and 2 μL 10× diluted cDNA in a final volume of 20 μL. The default StepOnePlus cycling parameters were used. RT-PCR gel images were obtained using a GelDoc-It (UVP) documentation system and expressions were quantified using ImageJ (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij), as reported previously [23]. Three biological replicates were analyzed for each sample, and relative transcript abundance (expression) was calculated using ubiquitin as an internal standard [23, 29, 30].

Microscopy and in-situ localization

For in situ RT-PCR, primers BLrt-f and BLrt-r were used (S1 Table). Cell area of adaxial epidermal cells were measured as previously described [31]. Shortly, mature leaves impressions were prepared with clear nail polish close to the middle of leaf near to the midrib, and from adaxial leaf surface. All impressions were fixed on glass slides, and examined under a phase contrast light microscope [31]. Tissues preparation, microscopy and in-situ localization were performed as previously described [28]. A confocal microscopy system, consisting of Spinning Disk Confocal Head (Yokogawa CSUX1), a Nikon Eclipse Ti inverted microscope outfitted with 10x and 60x oil immersion lenses, and a precision motorized stage, was used for sub-cellular localization of GFP in leaf cells from stably transformed BL-GFP-oe poplar. The system is coupled with a high-resolution, high-frame-rate camera (Photometrics Cool SNAPHQ2). Laser light sources include wavelength lines of 488, 561, 642 nm. The system was controlled with Metamorph software.

Sequence and phylogenetic analyses

Sequence homology searches and analyses were performed using the Phytozome (http://www.phytozome.net/poplar.php) and the National Center for Biotechnology Information BLAST server (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/). Protein sequence was downloaded locally, aligned by ClustalW method [32], and analyzed all using MEGA4 [33]. For construction of phylogenetic tree, the genetic distance method with the neighbor-joining approach was used. Confidence estimates for each branch of the resulting trees were statistically tested by bootstrap analyses of 1,000 replications, using MEGA4 software.

Microarray analyses

Native expression of BL occurs in apical tissues, and observed phenotypic differences were confined mostly to leaves and stems. Thus, we collect two bulk samples (six plants/bulk, two plants from each of the three BL-oe lines,) from apices, stem (30th internode), and leaves (30th node). Collected tissues were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C. Extraction of total RNAs were performed as previously described [28]. Microarray data were collected and analyzed according to MIAME standards [34] and deposited at GEO (GSE68859). The labeling, hybridization, and imaging procedures were performed according to Affymetrix protocols at the Center for Genomics Research and Biocomputing at Oregon State University (http://corelabs.cgrb.oregonstate.edu/affymetrix), using the Affymetrix Poplar GeneChip as previously described [23, 28]. Raw data were normalized using the RMA algorithm [35] and further analyzed statistically using TM4:MeV software [36, 37], utilizing Affymetrix probe annotation described in [38]. To identify differentially regulated genes/probes (DEG), we implemented LIMA analysis [39] with significance at False Discovery Rate FDR <0.05 between BL-oe and wild-type INRA 717-1B4 (WT-717). Gene Ontology (GO) analyses were done using the corresponding A. thaliana gene ID in AgriGO [40], with FDR<0.05.

Results

Isolation of a poplar activation tagged mutant with increased leaf size

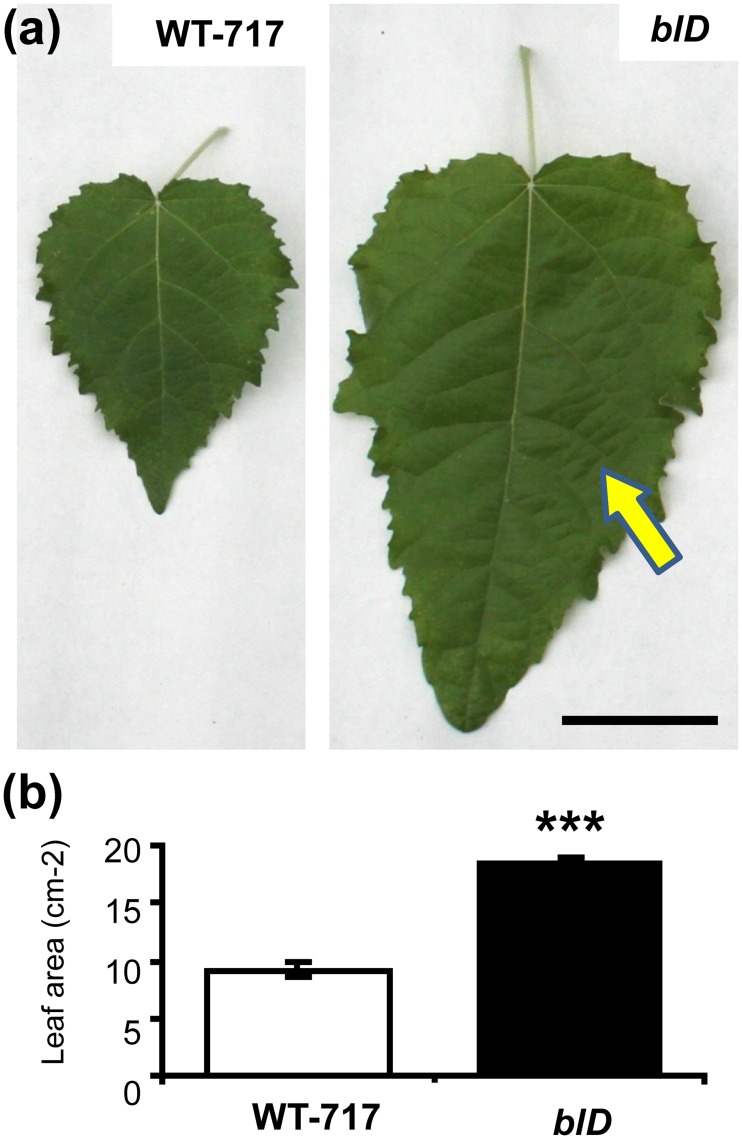

A mutant with increased leaf size was identified in a population of 627 activation-tagged poplar events [20, 41] (Fig 1). The big leaf dominant (blD) mutant was named for its predominant phenotype. In addition to increase in leaf size (Fig 1b), we also observed an uneven leaf surface (Fig 1a), a phenotype often associated with lesions in the coordination of cell proliferation and organ growth [42, 43]. Measurements after two full growing seasons in the field showed no change in height, but a statistically significant decrease in stem diameter compared to wild-type 717-1B4 (WT-717) (S1 Fig). Scanning electron microscopy and measurements of the epidermal cell area revealed no significant difference in cell size on the abaxial part of the leaves from two mutant and WT plants (S1 Fig). Therefore, we concluded that the observed phenotype is likely a result of increased cell proliferation, not cell size.

Fig 1. The blD activation tagging line with increased leaf size.

(a) Leaves from blD mutant line plants in the greenhouse show increased leaf size, when compared to wild-type plants (WT-717). Arrow, pinpoint to area with uneven surface of the leaf lamina. (b) Leaf area of greenhouse-grown plants from blD and WT-717 (bars represent standard error (SE), n = 5, ***—Student t-test P <0.001). Scale in (a) and (b) = 5 cm.

Identification and molecular characterization of the activation tagged gene

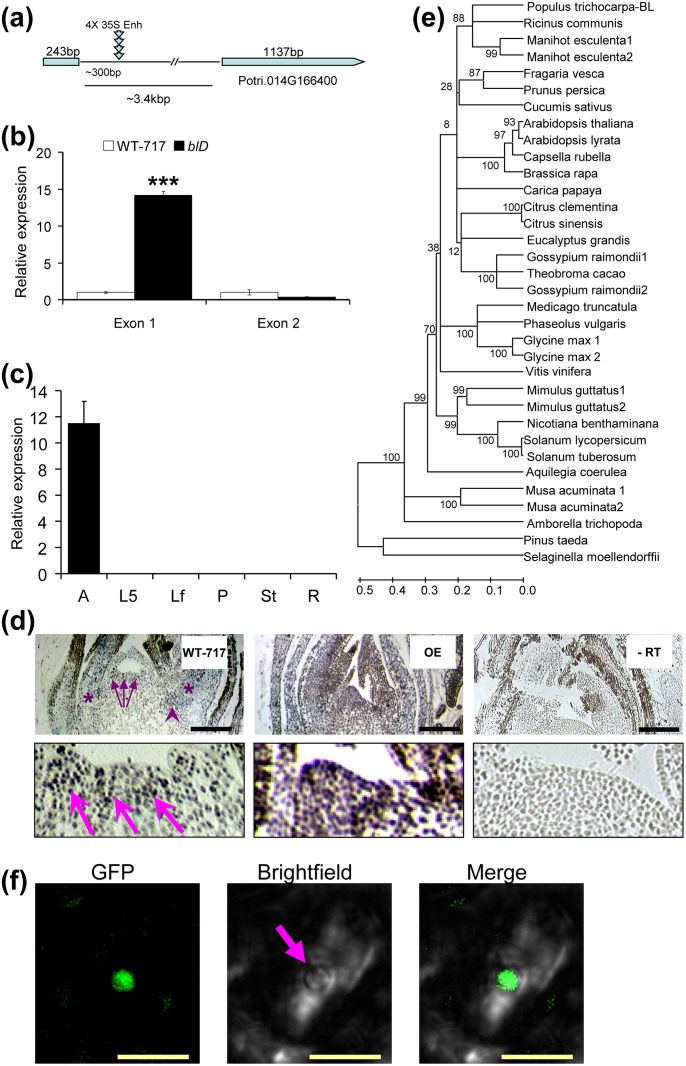

We recovered sequence flanking the left border of the transfer DNA (T-DNA) insert (GenBank ID KR698933). Repeated attempts to identify an alternative insertion site using various TAIL-PCR primers and plasmid rescue always detected the same position, suggesting that this is a single insertion event. BLASTn searches mapped the insertion to the Potri.014G166400 gene model on chromosome 14 (Fig 2a). T-DNA was inserted in the intron 254 base pairs (bp) downstream of the border with the first exon. Exon 1 was highly up-regulated in the mutant plant (Fig 2b); however, exon 2 showed approximately equal expression in mutant and WT-717 plants (Fig 2b). It appears that enhancers in the flanking intron sequence activated the promoter of the corresponding gene, and that transcription likely ceased prematurely in one of the multiple terminator sequences of the T-DNA inserted in the intron. Despite numerous attempts, we were unable to clone the aberrant transcript using 3' RACE with gene-specific primers targeting exon 1. Homology searches with the predicted protein sequence showed that the putative BL gene encodes a protein with high similarity (58% amino acid identity) to A. thaliana SAP (AT5G35770), which is involved in inflorescence, flower, and ovule development [12, 44]. In both A. thaliana and poplar, SAP is encoded by single genes. BIG LEAF/SAP homologues are uniquely present in all vascular plants, including Selaginella. The BL/SAP gene is not present in any Poaceae spp. with sequenced genomes, or in any grass ESTs. However, BL/SAP-like genes were found in monocotyledonous banana (Musa acuminata) (Fig 2e), and Cycadophyta species Zamia vazquezii (GenBank FD768395.1, FD768570.1; partial sequence not included in analyses). In poplar, BL is expressed almost exclusively in apical tissues (Fig 2c). In situ localization of BL transcripts pinpointed its localization to the apical meristem and newly formed leaf primordia, as well in the axillary meristem and very young leaves (Fig 2d).

Fig 2. Molecular characterization of the blD tagged gene.

(a) Schematic representation of the activation-tagging insertion in the Populus genome. (b) Expression verification of BIG LEAF (BL) activation. (Bars represent means ±SE, n = 5, ***—t-test p<0.001). (c) BL is expressed only in the apical part of the poplar tree. Tissues were collected from WT-717 plants at the same time of the day and correspond to: 1 cm of the root tips (R); 5 mm of apical shoot, including the meristem and subtending leaf primordia (A); incompletely expanded young (Leaf plastochron index [45], LPI 5) leaves (L5); fully expanded, mature (LPI 10) leaves (Lf); petioles of fully expanded leaves (P); whole stem collected from internodes of LPI 15–20 (St). In (b) and (c) relative expression was determined via qRT-PCR using ubiquitin as a loading control. Bars show means ± SE (n = 3). (d) In situ RT-PCR localization of the BL transcript in apices of WT-717 (left), BL over-expressing plants (middle). WT-717 apices served as negative controls (right). In WT-717, arrows indicate the localization of the BL transcript in the meristem and leaf primordia; arrowhead and star indicate localization in axillary meristem and newly formed leaves, respectively. Lower panels show magnified meristem areas. (e) Phylogenetic analysis of BIG LEAF/STERILE APETALA proteins. The tree was generated using Neighbor-Joining method with bootstrap confidence based on 1,000 iterations. (f) Nuclear sub-cellular localization of BL-GFP in leaf cell from a stably transformed BL-GFP-oe transgenic poplar. Pictures represent epi-fluorescence (GFP), black-white field (bright field), and a merged image. Scale bars in (d) = 200 μm, (f) = 25 μm.

Transgenic modifications recapitulate the BL phenotype

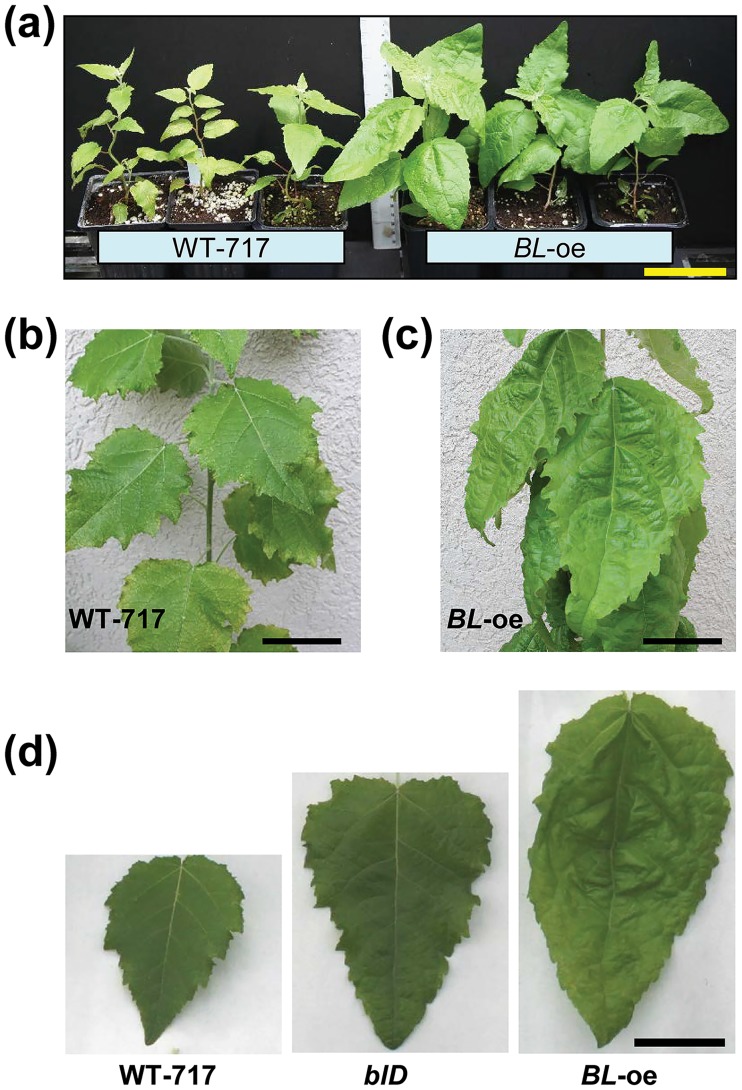

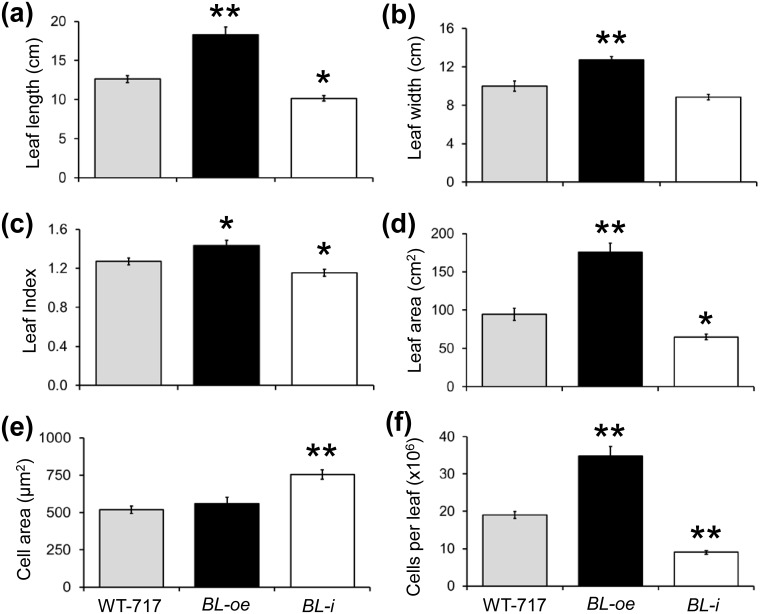

Despite the unusual activation by insertion into intron, because of the significance of the phenotype, we attempted recapitulation by transforming full-length cDNA of the BL coding region into WT-717 (S2a Fig). We regenerated more than 40 lines with the over-expression construct (BL-oe). Across all events, we observed leaf phenotypes ranging from those seen in the original blD mutant to larger increases in leaf size and more severe alterations (uneven leaf surface) in leaf lamina (Fig 3). BIG LEAF over-expressing plants (S2b Fig) displayed significant increases in several leaf size characteristics, including: length, width, length/width ratio, and area (Fig 4a–4d). We also produced RNAi lines (BL-i) to suppress expression of BL (S3 Fig). For all lines in which BL expression was down-regulated, we observed small but significant reductions in leaf length (Fig 4a), leaf area (Fig 4d), and length/width ratio (Fig 4c).

Fig 3. Recapitulation of the mutant blD phenotype.

(a) One-month-old plants, in the greenhouse, exhibited increased leaf size in the recapitulation lines (BL-oe). (b) and (c) Close view of leaves at the 15-20th internodes in six-month-old plants display visibly increased leaf size in BL-oe (c) compared to WT-717 (b). (d) Representative leaves (at the 20th internode) from WT-717, blD, and BL-oe plants. Scale bars (a)-(d) = 5 cm.

Fig 4. Characterization of leaf size and shape in BL-over-expressing (BL-oe) and down-regulated (BL-i) plants.

Leaf parameters were measured on fully developed leaves subtending the 15th to 20th internodes from greenhouse-grown plants. (a) Leaf length. (b) Leaf width. (c) Leaf Index calculated from (a) and (b). (d) Leaf area. (e) Cell area of adaxial epidermal cells. (f) Total cells per leaf calculated from (d) and (e). Error bars represent mean ±SE (n = 5, in (e) n = 20). Asterisks indicate significance as determined by Student’s t-test, with * and ** denoting P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively.

BL transgenic manipulations affect cell proliferation

To better understand the changes in leaf morphology, we measured cell number and size in the three genotypes (WT-717, BL-oe, and BL-i). BIG LEAF over-expression led to a significant increase in cell number, whereas down-regulation had the opposite effect (Fig 4f). In addition, cell area was significantly increased in BL-i plants (Fig 4e), suggesting a compensatory effect [46]. Moreover, BL overexpression caused shoots regeneration from callus tissues that typically does not produce shoots (S2c Fig). Thus, the BL effect on poplar leaf size is largely mediated through regulation of cell proliferation.

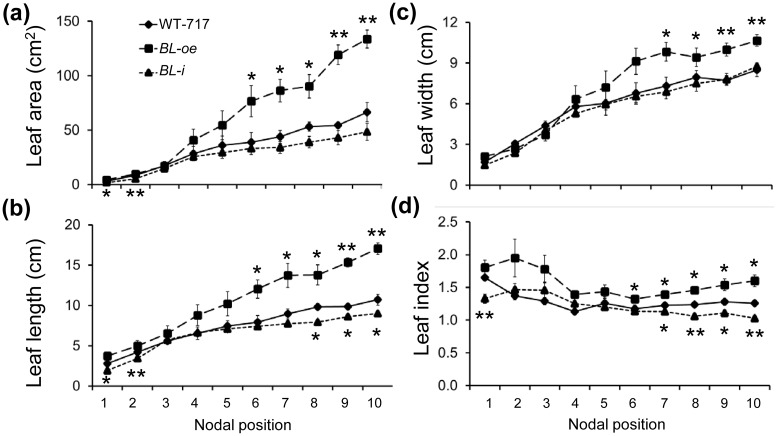

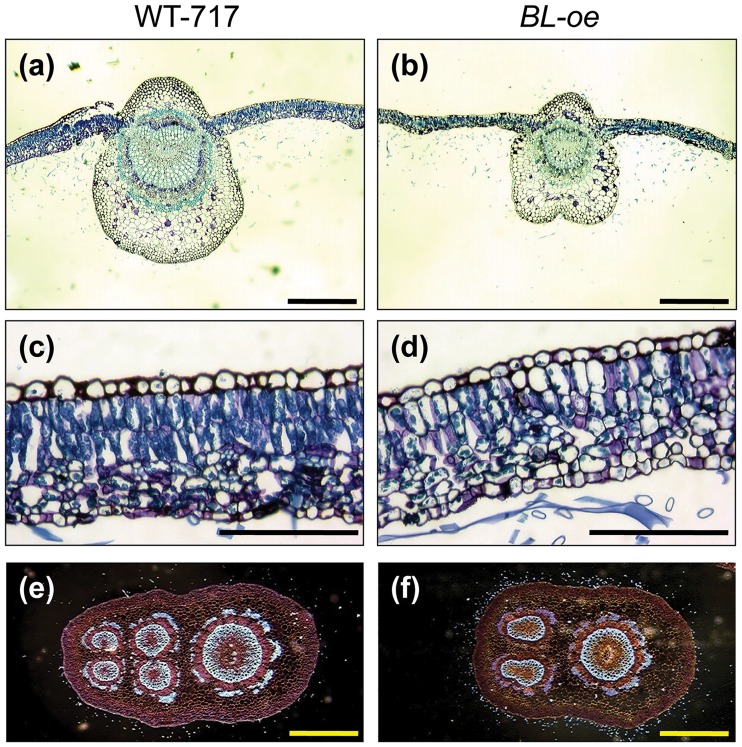

BL expression affects leaf growth and differentiation

We investigated the dynamics of leaf growth by taking measurements at different nodal positions, marking the developmental transition from young, actively growing (upper-most nodes) to mature, fully differentiated leaves that have achieved their final size. As early as the first two internodes, significant differences were observed in the leaf length (31% at the first, 18% at the second internode) and area (40% at the first, 35% at the second internode) of BL-i plants (Fig 5a and 5b). This is consistent with the native expression of BL in the apex, localized to the very young leaves and nodes (Fig 2c). In contrast, significant changes in leaf size of BL-oe plants were found further down the developmental gradient, starting around internode 6 (Fig 6a–6d). In addition, the leaves of BL-oe plants were lighter green and the leaf lamina were thinner (36.3±3.3% reduction, p<0.001, S2 Table) than WT-717 (Fig 6a and 6b). BL-oe leaves also had poorly differentiated, unorganized mesophyll layers. Consistent with the lighter green color, the cells from the mesophyll palisade in BL-oe transgenics contained visibly fewer chloroplasts per cell (61.4±2.8% reduction, p<0.001, S2 Table), with some cells almost completely devoid of chloroplasts (Fig 6c and 6d). The xylem in the mid-vein and petiole of BL-oe plants was less lignified as evidenced by the lighter toluidine blue staining (Fig 6b) and fainter fluorescence under phase contrast (Fig 6f) [47, 48]. The petioles of WT-717 plants have four amphicribral bundles near the main vein (Fig 6e), while BL-oe plants have only two (Fig 6f), demonstration additional changes in vasculature development. In summary, leaf differentiation was disrupted in response to BL up-regulation.

Fig 5. Dynamics of leaf growth in BL-over-expressing (BL-oe) and down-regulated (BL-i) plants.

Leaf parameters were measured from the 1st to the 10th fully developed leaves. (a) Leaf area. (b) Leaf length. (c) Leaf width. (d) Leaf Index calculated from (b) and (c). Bars show mean ±SE (n = 3), * and ** represent statistical differences determined by Student’s t-test at p <0.05 or 0.01, respectively. Asterisks at the bottom indicate significance of the BL-i and at the top of BL-oe when compared with WT-717.

Fig 6. Anatomical changes in the leaf blade and petiole of BL-oe plants.

The panels show leaf sections from WT-717 (left) and BL-oe (right) plants. All sections were stained with toluidine blue. (a) and (b) show the leaf midvein. Note the smaller midvein and reduced lignification (intensity of the blue staining) in BL-oe. (c) and (d) show the cross-section of leaf lamina. (e) and (f) show cross-sections of petioles. Images were obtained for better clarity under phase contrast. Scale bar in (a), (b), (e) and (f) = 500 μm; in (c) and (d) = 100 μm.

BL translational fusions and protein localization

Sequence analyses suggested that A. thaliana SAP might be a transcriptional regulator [12] and was recently identified as an F-box protein involved in PPD protein degradation [16]. Based on these results, also we produced transgenic lines expressing a translational fusion of BL with GFP (S4a Fig, BL-GFP-oe,), and found BL localized to the nucleus (Fig 2f). To further characterize BL protein, we produced multiple lines in which a fusion of GUS and the SRDX repressor domain [26] was over-expressed. Interestingly, all BL-SRDX-oe lines developed leaves comparable to WT-717 (S5 Fig), indicating that the SRDX fusion completely suppresses the positive effect of BL on leaf growth. In contrast, translational fusions in BL-GFP-oe (additional 165 amino acids) and BL-GUS-oe (additional 603 amino acids) transgenics displayed significantly increased leaf size, similar to the BL-oe lines (S4a Fig), indicating that the additional amino acids do not interfere with BL functionality, as does the SRDX repressor domain. SRDX is only a 12 amino acids repressor domain motive and when present can convert transcriptional activator to repressors (a dominant negative version), and also can affects the protein-protein interaction [26].

BL interferes with stem growth and development

One striking characteristic of both the blD mutant and BL-oe plants was a significant reduction in stem diameter (S1 and S6 Figs). We, therefore, studied stem anatomy at several internodes of WT-717, blD, BL-oe, and BL-i plants (S6 Fig). The internodes were chosen to represent the developmental and growth transition from primary (elongation), at internode 5, to secondary (lateral thickening), at internodes 10 and 20, growth [23, 49, 50]. The main differences were observed in xylem development (S6k Fig). In contrast to WT-717, xylem growth and differentiation of blD and BL-oe plants was severely curtailed across all of the analyzed internodes. In addition, phloem fiber lignification was also significantly reduced as evidenced by lack of fluorescence under phase contrast (S6B Fig). We also observed increased internodes number (S6l Fig) and reduced height (Fig 6m) in BL-oe transgenic lines. Down-regulation of BL (in BL-i plants) had no significant effect on secondary growth and development (S6 Fig).

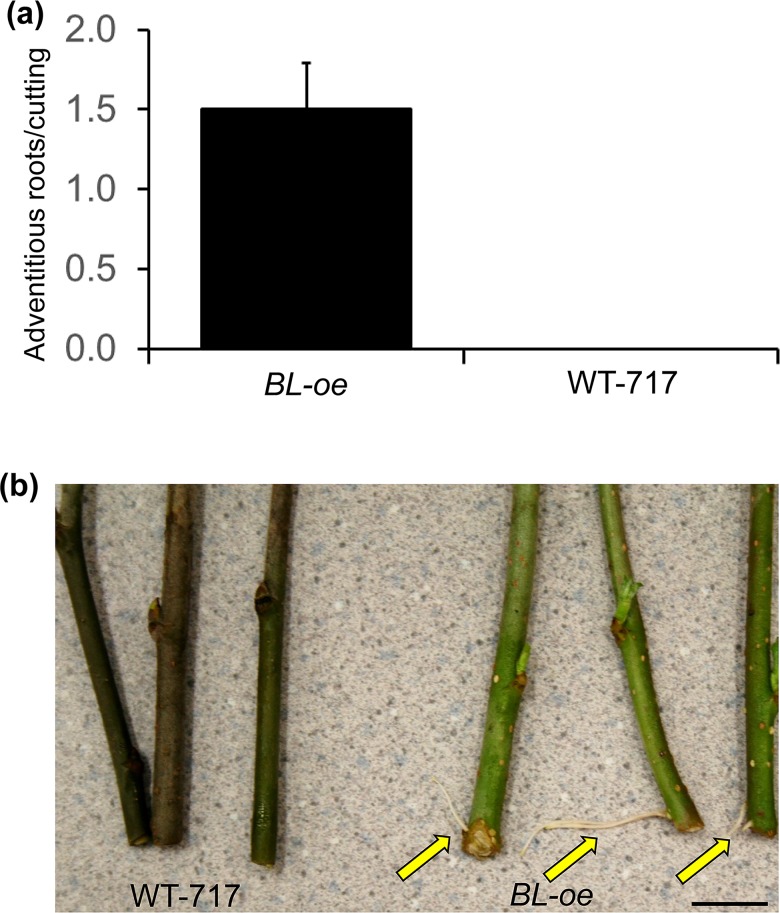

BL positively affects adventitious rooting

We investigated the rooting capacity of BL-oe plants by placing dormant cuttings in water for one month. The transgenics exhibited rooting capacity at the second week (Fig 7b) while WT-717 stem material did not formed roots for a month (Fig 7a). Observed changes in BL transgenics in growth, cell number, and size resemble changes observed in A. thaliana ANT mutants and transgenics [4]. Furthermore, the poplar ortholog of ANT (PtAIL1) was found to be a positive regulator of adventitious rooting [8]. This prompted us to study the expression of PtAIL1 in the transgenic plants (S7 Fig). Indeed, PtAIL1 expression was significantly up- and down-regulated in BL-oe and BL-i plants, respectively (S7 Fig). Therefore, the observed BL growth-promoting and adventitious root-inducing effects might be mediated via modulation of PtAIL1 expression.

Fig 7. BIG LEAF positively affects adventitious rooting.

(a) BIG LEAF over-expression increases adventitious rooting of stem cuttings. Bars show means ± SE (n = 3). (b) Two-weeks-old cuttings show adventitious rooting in BL-oe but not WT-717 plants. Scale bars is 1 cm.

Transcriptome changes underlying the BL phenotype

For a more complete understanding of the blD phenotype, we employed genome-wide microarray analyses. We compared the transcriptomes of BL-oe and WT-717 plants in three types of tissues: the shoot apex, mature leaves, and stems (30th internode). These analyses identified a total of 8,313 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) (LIMA test, FDR<0.05), from which 2,494 (1023 up-, and 1471 down-regulated) DEG were in the apex, 4,782 (2595 up-, and 2187 down-regulated) were in the leaves, and 2,354 (786 up-, and 1568 down-regulated) were in the stems (S1 Data). Microarray results were validated for nine genes (BIG LEAF plus 4 up- and 4 down-regulated, randomly chosen genes) using qRT-PCR (S8 Fig). Only 124 DEG were common to all three tissues (S2 Data). The GO analyses of all DEG in the different tissues (S3 Data) indicated common enrichment categories (S4 Data) for genes involved in response to stimulus, metabolic, and cellular process; biological regulation; and development (S4 Data). Among GO categories related to plant development were genes involved in meristem, leaf, and flower development and function (S4 Data).

Genes involved in regulation of organ growth [51, 52] were significantly affected by the BL over-expression (S5 Data). Genes which are positive regulators of organ growth, such as KLU (KLUH), ANT, TARGET OF RAPAMYCIN (TOR), ANGUSITFOLIA3 (AN3)-like, and GROWTH REGULATING FACTOR (GRF)-like, were significantly up-regulated in the leaf tissues (S3 Data). SAP has been shown to regulate PPD at the protein level via 26S proteasome degradation [16]. Surprisingly, poplar PPD homologs (Potri.005G214300: PtpAffx.37038.1.A1_at, Potri.002G048500: PtpAffx.201708.1.S1_at) were significantly up-regulated at the transcriptional level in BL-oe leaves (S1 Data).

Among all DEGs, we identified genes which are positive regulators of root growth that were specifically upregulated in the stems of BL-oe plants (S6 Data), including: MONOPTEROS/auxin response factor 5, ARF17, and NAC1 [53–55].

Discussion

Here we report the discovery and characterization of BIG LEAF (BL), a novel regulator of leaf size in poplar, named after the dominant, gain-of-function phenotype identified in an activation-tagged line. BL is an ortholog of the A. thaliana SAP gene [12, 16, 44]. BL/SAP is a plant-specific gene whose lineage can be traced as far back as the lycophyte Selaginella moellendorffii; in most species with sequenced genomes, there are usually one to two copies (Fig 2d). A homologous gene has not been found in any of the Poaceae species that have been sequenced, but it is present in other monocots, such as banana and date palm (Fig 2e). In A. thaliana, SAP was first shown to be essential for flower development and megasporogenesis [12]; however, the presence of BL/SAP paralogs in non-flowering S. moellendorffii is an indication that it may be involved in developmental processes other than flower development. In A. thaliana SAP was identified as a F-box protein that regulates organ size via degradation of PEAPOD proteins [16]; PEAPOD proteins are absent in Poaceae species [17, 56]. It has been proposed that the SAP and PPD genes evolved to regulate development of merisemoid cells in dicots, and modifying SAP expression in A. thaliana revealed that it positively affects leaf size [16], and flower size in Capsella [44].

In the present study, we show that over-expression of BL in poplar leads to greatly increased leaf size, while down-regulating BL leads to a slight but significant reduction in leaf size. The only slight reduction in leaf size is likely a result of an increase in cell size (Fig 4e). Such compensatory effects have been observed in leaves of irradiated plants, or in plants in which the growth-promoting genes, such as AN3 and ANT, were mutated [57], but was not seen in A. thaliana SAP loss-of-function mutant [16]. However, recently identified new loss-of-function alleles of SAP [16] led to same reduction of leave size as described here plants with down-regulated BL (BL-i, Fig 4).

Involvement of BL in the regulation of leaf size in poplar is also supported by the increased expression of major regulators of leaf growth in the BL-oe plants (S6 Fig, S5 Data). For example, the poplar ortholog of ANT, PtaAIL1, a major positive regulator of organ growth [51], was up-regulated in BL-oe and down-regulated in BL-i plants (S4 Fig, S5 Data). The changes in PtaAIL1 expression are even more significant given that SAP is a part of a complex mechanism that regulates AG expression in A. thaliana [10, 11]. This suggests that ANT and BL/SAP may be part of a common module involved regulating leaf size through a yet uncharacterized mechanism involving protein degradation, given that SAP is an F-box protein [16]. The role of BL in determining leaf size in poplar involves regulation of the very early stages of leaf outgrowth, around or during leaf primordia initiation and outgrowth. This notion is reinforced by the localization of gene expression in the SAM, particularly leaf primordia, and its almost complete absence from the later stages of leaf development (Fig 1). Furthermore, and more importantly, BL knock-down via RNAi resulted in a reduction in leaf size during the very early stages of leaf outgrowth (Fig 5). In contrast, ectopic expression of BL in mature leaves, where BL is usually not expressed, resulted in continuous growth and, thus, increased leaf size (Fig 5). Leaf size is determined by cell proliferation and cell growth. BIG LEAF function clearly involves regulation of cell proliferation (Fig 4 and S2c Fig). BIG LEAF over-expression in poplar led to increased cell number, while down-regulation had the opposite affect (Fig 4e). In summary, BL regulates leaf size in poplar by positively regulating cell proliferation during the very early stages of leaf outgrowth, similarly to effect of SAP in A. thaliana [16].

In addition to leaf size, we showed that BL has a strong, positive effect on adventitious root formation. Adventitious rooting is important for vegetative propagation in many crops and can greatly affect the deployment of clonal material [8, 58, 59]. We show that BL expression is correlated with the transcript abundance of PtAIL1, which was previously shown to regulate adventitious root formation [8], further implicating BL in the regulation of this process in poplar.

In sharp contrast to the positive effect on cell proliferation and organ growth in leaves and adventitious roots, BL appears to have a strong inhibitory effect on stem diameter, specifically xylem formation (S6 Fig). Given that native BL expression is not detected in stems, this effect seems to be the result of the ectopic expression of BL. This outcome shows the highly specific nature of organ-size regulation; a positive regulator of leaf growth can act as a repressor in the context of stem thickening. Given that BL inhibited the development of leaf veins and petioles (Fig 6), the suppression of xylem growth may be the result of BL delaying or reducing vascular differentiation.

BIG LEAF and SAP protein sequences contain domains that are typically found in transcriptional regulators [12] and the latter was recently identified as F-box protein [16]. Using a BL-GFP fusion protein, we showed that BL protein is localized in the nucleus (Fig 2e), same is true for A. thaliana SAP [16]. Furthermore, we showed that fusion of BL with the strong SRDX repressor domain rendered the protein non-functional, as evidenced by the wild-type-like phenotype of the BL-SRDX over-expressing transgenics (S5 Fig). In sharp contrast, fusion of BL with either the GFP or GUS proteins led to the same phenotype as BL-over-expressing transgenics (S4 Fig). This suggests that SRDX has specific inhibitory effect on BL function by interfering with putative protein-protein interactions [60], and can be utilized to study BL protein-protein interactions.

The strong promoting effect of BL/SAP on leaf growth is of interest in relation to increased productivity in lignocellulosic bioenergy and other types of crops. However, the negative effects associated with the strong ectopic expression needs to be addressed before the gene can be used as a tool to enhance productivity. This can be achieved, for example, by using tissue/organ-specific expression and/or more moderate up-regulation of the gene.

Supporting information

(PDF)

(PDF)

Graphs present data for the plants height (top), stem diameter (middle), and leaves adaxial epidermis cell area (bottom) are shown. Error bars represent mean ±SE (n = 4, n = 25 for cell area), asterisk indicate significance P<0.05 as determined by Student’s t-test.

(TIF)

(a) Schematic representation of the construct used for transformation. Backbone plasmid is pART27. P35S = 35S promoter from the Cauliflower Mosaic Virus, ocsT = octopine synthase terminator, KmR = gene cassette for kanamycin resistance in plants, R and L are right- and left-hand T-DNA borders. (b) RT-PCR expression analyses of BL in apical shoots from six, randomly chosen transgenic BL-oe lines (1 to 6) reveal strong up-regulation of the gene in all tested lines. Ubiquitin (UBI) was used as a loading control. (c) Spontaneous shoot outgrowth from cambium-derived callus in BL-oe transgenic plants (left panel), observed in about 15% (with 1–4 shoots) of the plants. WT-717 (right panel) formed regular callus to seal the wound but no shoot outgrowth was observed.

(TIF)

In upper panel is shown representative RT-PCR demonstrating down-regulation of BL expression in apex from three transgenic lines. Ubiquitin (UBI) is used as a loading control.

(TIF)

Over-expression of BL fused to either GFP (a) or GUS (b) fully recapitulated the BL-oe phenotype. Leaves shown are from three independent transgenic lines. Scale bar = 10 cm.

(TIF)

Leaf parameters were measured from 15th to 20th fully developed leaf. (a) Leaf length. (b) Leaf width measured at leaf center. (a) Leaf Index calculated from (a) and (b). (d) Leaf area. (e) Cell area of adaxial epidermal cells. (F) Total cells per leaf calculated from (d) and (e). (g) Representative leaves from WT-717 and three BL-SRDX-oe lines. (h) Validation of the over-expression of BL-SRDX in the three lines (1, 3, and 8). Error bars represent SE (n = 5 leaves from the three lines, in e n = 20 are the cells from leaves from of the three lines). Asterisks indicate significance as determined by Student’s t-test, with * denoting P <0.05.

(TIF)

Stem cross sections from different genotypes are shown as follows: (a), (d), and (g) WT-717; (b), (e), and (h) BL-oe; and (c), (f), and (i) BL-i. All stem sections were stained with toluidine blue and observed under phase contrast at different internodes as follows: (a) to (c) 5th internode; (d) to (f) 10th internode; and (g) to (i) 20th internode. Note reduced lignified (not as bright) in BL-oe 5th internode (b). (j) Stem diameter. (k) Xylem width. (l) Internode number. (m) Plant height. Error bars in (j) to (m) are SE (n = 5). Pf—phloem fibers, Xy—xylem, Pi—pith. Scale bar = 500 μm.

(TIF)

RT-qPCR Relative expression was normalized using ubiquitin (UBI) (n = 3, mean ±SE). Asterisks indicate significance as determined by Student’s t-test, with * denoting P <0.05.

(TIF)

For comparison, RT-PCR and microarrays expression are shown side by side. Bars represent mean ±SE (n = 3 for PCR, n = 2 for microarray). Abbreviations used correspond to the names and gene models specified in S2 Table. Quantitative RT-PCR expression estimates were normalized using ubiquitin.

(TIF)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

Acknowledgments

We thank Petio Kotov and Sharon Junttila for the help with histological analysis.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files. Genomic DNA sequence flanking the left border of the T-DNA (GenBank ID KR698933); Potri.014G166400 is gene model number for BL in Populus, corresponding to P. tremula x P. alba BL (GenBank ID KR698934); microarray data were deposited at GEO ID GSE68859.

Funding Statement

This research was supported, in part, by grants from the Office of Science Biological and Environmental Research (BER) program at the U.S. Department of Energy (Grants DE-FG02-06ER64185, DE-FG02-05ER64113, and DE-SC0008462); U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) National Resources Inventory Plant Genome Program (Grant 2003- 04345); Consortium for Plant Biotechnology Research, Inc. (Grant GO12026- 203A); USDA Biotechnology Risk Assessment Research Grants Program (Grant 2004-35300-14687); USDA McIntire-Stennis Fund (Grant 1001498); USDA National Institute of Food Agriculture (MICW-2011-04378); and industrial members of the Tree Biosafety and Genomics Research Cooperative based at Oregon State University.

References

- 1.Tsukaya H. The leaf index: heteroblasty, natural variation, and the genetic control of polar processes of leaf expansion. Plant Cell Physiol. 2002;43(4):372–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson K, Lenhard M. Genetic control of plant organ growth. New Phytologist. 2011;191(2):319–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03737.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gonzalez N, Vanhaeren H, Inze D. Leaf size control: complex coordination of cell division and expansion. Trends in Plant Science. 2012;17(6):332–40. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2012.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mizukami Y. A matter of size: developmental control of organ size in plants. CurrOpinPlant Biol. 2001;4(6):533–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krizek BA. Ectopic expression of AINTEGUMENTA in Arabidopsis plants results in increased growth of floral organs. DevGenet. 1999;25(3):224–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ichihashi Y, Tsukaya H. Behavior of leaf meristems and their modification. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2015;6 doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.01060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horstman A, Willemsen V, Boutilier K, Heidstra R. AINTEGUMENTA-LIKE proteins: hubs in a plethora of networks. Trends in Plant Science. 2014;19(3):146–57. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2013.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rigal A, Yordanov YS, Perrone I, Karlberg A, Tisserant E, Bellini C, et al. The AINTEGUMENTA LIKE1 Homeotic Transcription Factor PtAIL1 Controls the Formation of Adventitious Root Primordia in Poplar. Plant Physiology. 2012;160(4):1996–2006. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.204453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karlberg A, Bako L, Bhalerao RP. Short Day-Mediated Cessation of Growth Requires the Downregulation of AINTEGUMENTALIKE1 Transcription Factor in Hybrid Aspen. Plos Genetics. 2011;7(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krizek BA, Prost V, Macias A. AINTEGUMENTA promotes petal identity and acts as a negative regulator of AGAMOUS. Plant Cell. 2000;12(8):1357–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alvarez-Buylla ER, Benítez M, Corvera-Poiré A, Chaos Cador A, de Folter S, Gamboa de Buen A, et al. Flower Development. Arabidopsis Book. 2010;8:e0127 doi: 10.1199/tab.0127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Byzova MV, Franken J, Aarts MG, de Almeida-Engler J, Engler G, Mariani C, et al. Arabidopsis STERILE APETALA, a multifunctional gene regulating inflorescence, flower, and ovule development. Genes Dev. 1999;13(8):1002–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsukaya H. Leaf Development. 11 ed: American Society of Plant Biologists; 2013. p. e0163. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim G-T, Tsukaya H, Uchimiya H. The CURLY LEAF gene controls both division and elongation of cells during the expansion of the leaf blade in Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta. 1998;206(2):175–83. doi: 10.1007/s004250050389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cnops G, Jover-Gil S, Peters JL, Neyt P, De Block S, Robles P, et al. The rotunda2 mutants identify a role for the LEUNIG gene in vegetative leaf morphogenesis. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2004;55(402):1529–39. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erh165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Z, Li N, Jiang S, Gonzalez N, Huang X, Wang Y, et al. SCFSAP controls organ size by targeting PPD proteins for degradation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat Commun. 2016;7 doi: 10.1038/ncomms11192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.White DWR. PEAPOD regulates lamina size and curvature in Arabidopsis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2006;103(35):13238–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604349103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meilan R, Ma C. Poplar (Populus spp.) In: Wang K, editor. Agrobacterium Protocols Volume 2. Methods in Molecular Biology. 344 ed: Humana Press; 2007. p. 143–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kraus D. Consolidated data analysis and presentation using an open-source add-in for the Microsoft Excel-« spreadsheet software. Medical Writing. 2014;23(1):25–8. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Busov V, Yordanov Y, Gou J, Meilan R, Ma C, Regan S, et al. Activation tagging is an effective gene tagging system in Populus. Tree Gen Genom. 2011;7:91–101. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gleave AP. A Versatile Binary Vector System with A T-Dna Organizational-Structure Conducive to Efficient Integration of Cloned Dna Into the Plant Genome. Plant Molecular Biology. 1992;20(6):1203–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holsters M, de WD, Depicker A, Messens E, van MM, Schell J. Transfection and transformation of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. MolGenGenet. 1978;163(2):181–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yordanov Y, Regan S, Busov V. Members of the Lateral Organ Boundaries Domain (LBD) Transcription Factors Family are Involved in Regulation of Secondary Growth in Populus. Plant Cell. 2010;22:3662–77. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.078634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Curtis MD, Grossniklaus U. A gateway cloning vector set for high-throughput functional analysis of genes in planta. Plant Physiology. 2003;133(2):462–9. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.027979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karimi M, Inze D, Depicker A. GATEWAY vectors for Agrobacterium-mediated plant transformation. Trends Plant Sci. 2002;7(5):193–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hiratsu K, Matsui K, Koyama T, Ohme-Takagi M. Dominant repression of target genes by chimeric repressors that include the EAR motif, a repression domain, in Arabidopsis. Plant Journal. 2003;34(5):733–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lazo GR, Stein PA, Ludwig RA. A Dna Transformation-Competent Arabidopsis Genomic Library in Agrobacterium. Bio-Technology. 1991;9(10):963–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yordanov YS, Ma C, Strauss SH, Busov VB. EARLY BUD-BREAK 1 (EBB1) is a regulator of release from seasonal dormancy in poplar trees. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111(27):10001–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1405621111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsai CJ, Harding SA, Tschaplinski TJ, Lindroth RL, Yuan YN. Genome-wide analysis of the structural genes regulating defense phenylpropanoid metabolism in Populus. New Phytologist. 2006;172(1):47–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01798.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(T)(-Delta Delta C) method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Russo G, De Angelis P, Mickle J, Lumaga Barone M. Stomata morphological traits in two different genotypes of Populus nigra L. iForest—Biogeosciences and Forestry. 2015;8(4):547–51. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. Clustal-W—Improving the Sensitivity of Progressive Multiple Sequence Alignment Through Sequence Weighting, Position-Specific Gap Penalties and Weight Matrix Choice. Nucleic Acids Research. 1994;22(22):4673–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA4: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2007;24(8):1596–9. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brazma A, Hingamp P, Quackenbush J, Sherlock G, Spellman P, Stoeckert C, et al. Minimum information about a microarray experiment (MIAME)-toward standards for microarray data. Nature Genetics. 2001;29(4):365–71. doi: 10.1038/ng1201-365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bolstad BM, Irizarry RA, Astrand M, Speed TP. A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics. 2003;19(2):185–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saeed AI, Sharov V, White J, Li J, Liang W, Bhagabati N, et al. TM4: A free, open-source system for microarray data management and analysis. Biotechniques. 2003;34(2):374-+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chu VT, Gottardo R, Raftery AE, Bumgarner RE, Yeung KY. MeV+R: using MeV as a graphical user interface for Bioconductor applications in microarray analysis. Genome Biology. 2008;9(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsai CJ, Ranjan P, DiFazio SP, Tuskan GA, Johnson V. Poplar genome microarrays In: Joshi CP, DiFazio SP, Kole C, editors. Genetics, Genomics and Breeding of Poplars. Enfield, NH: Science Publishers; 2011. p. 112–27. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smyth GK. Limma: linear models for microarray data In: Gentleman R, Carey V, Dudoit S, Irizarry R, Huber W, editors. Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Solutions using R and Bioconductor, R: Springer, New York; 2005. p. 397–420. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Du Z, Zhou X, Ling Y, Zhang ZH, Su Z. agriGO: a GO analysis toolkit for the agricultural community. Nucleic Acids Research. 2010;38:W64–W70. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Busov VB, Brunner AM, Meilan R, Filichkin S, Ganio L, Gandhi S, et al. Genetic transformation: a powerful tool for dissection of adaptive traits in trees. New Phytologist. 2005;167(1):9–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01412.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stieger PA, Meyer AD, Kathmann P, Frundt C, Niederhauser I, Barone M, et al. The orf13 T-DNA gene of Agrobacterium rhizogenes confers meristematic competence to differentiated cells. Plant Physiology. 2004;135(3):1798–808. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.040899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sinha NR, Williams RE, Hake S. Overexpression of the Maize Homeo Box Gene, Knotted-1, Causes A Switch from Determinate to Indeterminate Cell Fates. Genes & Development. 1993;7(5):787–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sicard A, Kappel C, Lee YW, Woźniak NJ, Marona C, Stinchcombe JR, et al. Standing genetic variation in a tissue-specific enhancer underlies selfing-syndrome evolution in Capsella. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2016; doi: 10.1073/pnas.1613394113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Larson PR, Isebrands JG. The Plastochron Index as Applied to Developmental Studies of Cottonwood. Canadian Journal of Forest Research. 1971;1(1):1–11. doi: 10.1139/x71-001 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mizukami Y, Fischer RL. Plant organ size control: AINTEGUMENTA regulates growth and cell numbers during organogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(2):942–7. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.O'Brien TP, Feder N, McCully ME. Polychromatic staining of plant cell walls by toluidine blue O. Protoplasma. 1964;59(2):368–73. doi: 10.1007/bf01248568 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Du J, Mansfield SD, Groover AT. The Populus homeobox gene ARBORKNOX2 regulates cell differentiation during secondary growth. Plant Journal. 2009;60(6):1000–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.04017.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Larson P. Interrelations between phyllotaxis, leaf development and the primary-secondary vascular transition in Populus deltoides. Annals of botany. 1980;46(6):757–69. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen YR, Yordanov YS, Ma C, Strauss S, Busov VB. DR5 as a reporter system to study auxin response in Populus. Plant Cell Reports. 2013;32(3):453–63. doi: 10.1007/s00299-012-1378-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Krizek BA. Making bigger plants: key regulators of final organ size. CurrOpinPlant Biol. 2009;12(1):17–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sabaghian E, Drebert Z, Inzé D, Saeys Y. An integrated network of Arabidopsis growth regulators and its use for gene prioritization. Scientific Reports. 2015;5:17617 doi: 10.1038/srep17617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wei HR, Yordanov YS, Georgieva T, Li X, Busov V. Nitrogen deprivation promotes Populus root growth through global transcriptome reprogramming and activation of hierarchical genetic networks. New Phytologist. 2013;200(2):483–97. doi: 10.1111/nph.12375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xie Q, Guo HS, Dallman G, Fang S, Weissman AM, Chua NH. SINAT5 promotes ubiquitin-related degradation of NAC1 to attenuate auxin signals. Nature. 2002;419(6903):167–70. doi: 10.1038/nature00998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Petricka JJ, Winter CM, Benfey PN. Control of Arabidopsis Root Development. Annual Review of Plant Biology, Vol 63. 2012;63:563–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gonzalez N, Pauwels L, Baekelandt A, De Milde L, Van Leene J, Besbrugge N, et al. A Repressor Protein Complex Regulates Leaf Growth in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell. 2015;27(8):2273–87. doi: 10.1105/tpc.15.00006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hisanaga T, Kawade K, Tsukaya H. Compensation: a key to clarifying the organ-level regulation of lateral organ size in plants. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2015;66(4):1055–63. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Busov V, Yordanov Y, Meilan R. Discovery of genes involved in adventitious root formation using Populus as a model Niemi K, Scagel CF eds Adventitious root formation of forest trees and horticultural plants—From genes to applications Research Signpost; 2009. p. 85–103. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Legue V, Rigal A, Bhalerao RP. Adventitious root formation in tree species: involvement of transcription factors. Physiol Plant. 2014;151(2):192–8. doi: 10.1111/ppl.12197 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Matsui K, Ohme-Takagi M. Detection of protein-protein interactions in plants using the transrepressive activity of the EAR motif repression domain. Plant Journal. 2010;61(4):570–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.04081.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF)

(PDF)

Graphs present data for the plants height (top), stem diameter (middle), and leaves adaxial epidermis cell area (bottom) are shown. Error bars represent mean ±SE (n = 4, n = 25 for cell area), asterisk indicate significance P<0.05 as determined by Student’s t-test.

(TIF)

(a) Schematic representation of the construct used for transformation. Backbone plasmid is pART27. P35S = 35S promoter from the Cauliflower Mosaic Virus, ocsT = octopine synthase terminator, KmR = gene cassette for kanamycin resistance in plants, R and L are right- and left-hand T-DNA borders. (b) RT-PCR expression analyses of BL in apical shoots from six, randomly chosen transgenic BL-oe lines (1 to 6) reveal strong up-regulation of the gene in all tested lines. Ubiquitin (UBI) was used as a loading control. (c) Spontaneous shoot outgrowth from cambium-derived callus in BL-oe transgenic plants (left panel), observed in about 15% (with 1–4 shoots) of the plants. WT-717 (right panel) formed regular callus to seal the wound but no shoot outgrowth was observed.

(TIF)

In upper panel is shown representative RT-PCR demonstrating down-regulation of BL expression in apex from three transgenic lines. Ubiquitin (UBI) is used as a loading control.

(TIF)

Over-expression of BL fused to either GFP (a) or GUS (b) fully recapitulated the BL-oe phenotype. Leaves shown are from three independent transgenic lines. Scale bar = 10 cm.

(TIF)

Leaf parameters were measured from 15th to 20th fully developed leaf. (a) Leaf length. (b) Leaf width measured at leaf center. (a) Leaf Index calculated from (a) and (b). (d) Leaf area. (e) Cell area of adaxial epidermal cells. (F) Total cells per leaf calculated from (d) and (e). (g) Representative leaves from WT-717 and three BL-SRDX-oe lines. (h) Validation of the over-expression of BL-SRDX in the three lines (1, 3, and 8). Error bars represent SE (n = 5 leaves from the three lines, in e n = 20 are the cells from leaves from of the three lines). Asterisks indicate significance as determined by Student’s t-test, with * denoting P <0.05.

(TIF)

Stem cross sections from different genotypes are shown as follows: (a), (d), and (g) WT-717; (b), (e), and (h) BL-oe; and (c), (f), and (i) BL-i. All stem sections were stained with toluidine blue and observed under phase contrast at different internodes as follows: (a) to (c) 5th internode; (d) to (f) 10th internode; and (g) to (i) 20th internode. Note reduced lignified (not as bright) in BL-oe 5th internode (b). (j) Stem diameter. (k) Xylem width. (l) Internode number. (m) Plant height. Error bars in (j) to (m) are SE (n = 5). Pf—phloem fibers, Xy—xylem, Pi—pith. Scale bar = 500 μm.

(TIF)

RT-qPCR Relative expression was normalized using ubiquitin (UBI) (n = 3, mean ±SE). Asterisks indicate significance as determined by Student’s t-test, with * denoting P <0.05.

(TIF)

For comparison, RT-PCR and microarrays expression are shown side by side. Bars represent mean ±SE (n = 3 for PCR, n = 2 for microarray). Abbreviations used correspond to the names and gene models specified in S2 Table. Quantitative RT-PCR expression estimates were normalized using ubiquitin.

(TIF)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files. Genomic DNA sequence flanking the left border of the T-DNA (GenBank ID KR698933); Potri.014G166400 is gene model number for BL in Populus, corresponding to P. tremula x P. alba BL (GenBank ID KR698934); microarray data were deposited at GEO ID GSE68859.